Abstract

This study investigates how political parties used the federal structure of government for discursive blame attribution strategies in parliamentary debates during the Covid-19 crisis. The analysis focuses on the German case which is considered an embodiment of cooperative federalism. Largely intertwined responsibilities and joint decision making provide incentives for self-serving blame attribution strategies. The empirical investigation includes a qualitative content analysis of 212 parliamentary debates in the Bundestag and the 16 state parliaments. Overall, 2067 statements were manually coded and integrated into a novel dataset. The data reveal a more diverse discursive toolkit of blame attribution strategies than commonly conceptualised. The study demonstrates that parties, especially when they are involved in intergovernmental bodies and coalition governments, resort to ‘softer’ forms of blaming. The vertical integration of the party system also creates an effective blame barrier, containing self-serving strategies even during the prolonged crisis and several election campaigns.

Federal systems have often been considered conducive to holding heterogeneous societies together, fostering democracy and enhancing economic growth. However, pessimism about their true incentive structures has become increasingly widespread. Particularly in times of crisis, political actors may leverage the lack of clarity in federal institutions to avoid responsibility (Hinterleitner et al. Citation2023: 327; Maestas et al. Citation2008: 609). Voters in federal states find it difficult to determine who is in charge for which policies (Cutler Citation2004, Citation2008; Däubler et al. Citation2018). This is especially problematic in systems of cooperative federalism in which responsibilities are intertwined and actors decide jointly. Institutionalising the principles of solidarity and mutual self-restraint, these systems demand from ultimately competing party actors the willingness to collaborate and find compromises in a plethora of federal and partisan bodies and networks. On the flipside, they create strong incentives for politicians to further complicate the proper assignment of responsibility by blaming others.

In this article, we argue that parties align their discursive behaviour with these rules of the game. They employ discursive strategies and practices that simultaneously allow them to blame other federal actors and entities while still conforming to the terms and norms of cooperative federalism. Particularly in a prolonged crisis such as Covid-19, self-serving or even opportunistic strategies are likely. In research on federalism, opportunistic behaviour in federal states has been a recurrent theme (Bednar Citation2009). Yet, a couple of key questions have remained unaddressed. The first concerns conceptual clarity: What exactly do we understand by ‘blaming’? Moreover, as political actors need to adapt flexible strategies in conflictive institutional settings: What are the different forms of blaming? Only in distinguishing such context-dependent strategies, the main research question of this study can be properly answered: How do parties respond to the conflicting incentives created by cooperative federalism in their use of blame attribution strategies?

A large and growing amount of literature has been published on partisanship and the citizens’ responsibility assignment in federal systems (Graham and Singh Citation2023; Jin et al. Citation2023; Kennedy et al. Citation2022; Maestas et al. Citation2008; Malhotra Citation2008; León et al. Citation2018; Rico and Liñeira Citation2018). Yet, a systematic understanding of how parties – as the main political actors – leverage the federal structure of government for blame attribution strategies is still lacking. This study addresses this research gap by examining the strategies and practices that parties in parliament at the different levels of government employ in ‘communicative discourses’ (Schmidt Citation2008: 322) with the public.

Empirically, we explore the German model of federalism, since Germany provides a particularly instructive case for the study of parties’ blame attribution strategies in multilevel systems with conflicting institutional incentive structures. On the one hand, the German constitution prescribes cooperation between the federal entities. Cooperative federalism is further reinforced by a system of multicoloured coalition governments at both levels of government requiring coordination and cooperation between competing parties within governments as well as across the territorial levels. On the other hand, these elements are coupled with the parliamentary arena that is shaped by party competition (Benz Citation1999; Lehmbruch Citation2000; Kropp Citation2021). These competing incentives were particularly pronounced during the Covid-19 crisis. Parties at both levels of government had to cope with extraordinary pressures, forcing them to coordinate, collaborate, and find common solutions to handle the pandemic, while parties in opposition oscillated between government support and harsh criticism. In addition to handling the pandemic, five state elections as well as the federal election took place in 2021, further enhancing party competition and making defection from cooperative discourse a worthwhile endeavour.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. In the next section, we present our conceptual framework and hypotheses. The third section summarises the major features of federal Covid-19 crisis management in Germany. Then, we outline the data collection, the qualitative content analysis, and the new dataset.Footnote1 We cover 212 key parliamentary debates in the national parliament (Bundestag) and the 16 state parliaments (Landtage) between the outbreak of the pandemic in Germany in February 2020 and the federal election on 26 September 2021. Based on 2067 manually coded statements, the data allow for an in-depth analysis of the parties’ discursive strategies. The dataset covers all parties represented in the Bundestag, all parliaments at both levels of government, and the first 18 months of the Covid-19 pandemic, which include different periods and strength of political contention. The next section presents the empirical results. The data reveal that parties do leverage the federal division of tasks in crisis management to employ blame attribution strategies. However, they adapt these strategies depending on whether they bear government responsibility or not. Moreover, they carefully distinguish between ‘softer’ and ‘harder’ forms of blaming. The final section discusses these findings and their implications for the cohesiveness of federal systems as well as avenues for further research.

Conceptual framework

Discursive blaming strategies in cooperative federalism

A considerable amount of literature has been published on blaming, blame avoidance, blame shifting and blame games, revisiting and elaborating on an argument made by R. Kent Weaver already in the 1980s (Schlipphak et al. Citation2023: 1719).Footnote2 According to Weaver (Citation1986: 371), political actions ‘are motivated primarily by the desire to avoid blame for unpopular decisions rather than by seeking to claim credit for popular ones.’ This is mainly due to the negativity bias, according to which actual or perceived losses weigh more than potential gains (Hood Citation2011: 9–14). Blame attribution becomes particularly important in times of crisis (Bach and Wegrich Citation2019; De Ruiter and Kuipers Citation2022; Hinterleitner Citation2020; Hinterleitner et al. Citation2023; Moynihan Citation2012), unsurprisingly also in the Covid-19 pandemic (Flinders Citation2020; Greer et al. Citation2022). When political mistakes are inevitable, decisions are unpopular, and the actual scope of action is limited, parties pursue presentational strategies in their public communication, trying to blame others ‘by spin, stage management, and argument’ (Hood Citation2011: 17).

There are two reasons why federal systems are particularly prone to these strategies. Firstly, they offer parties several potential targets for blame attribution due to the multi-level structure of government (Hinterleitner et al. Citation2023: 327). Political actors at the sub-national level can blame other constituent units and specific actors in these units, or the federal government and specific actors at the federal level, such as the federal cabinet or individual cabinet members. Federal actors, again, can blame the sub-national level, specific constituent units, and individual actors in these units. Political actors at both levels of government can also target the federation in its entirety. Secondly, ‘federalism places a high demand on voters seeking to assign responsibility for government actions relative to voters in non-federal systems’ (Kennedy et al. Citation2022: 159). This applies especially to federal systems which are characterised by overlapping authorities, a complex division of competences, and joint decision making.

In order to avoid responsibility, ‘political actors have incentives to shift blame to actors at other levels, further complicating the public’s task in assigning blame to the appropriate targets’ (Maestas et al. Citation2008: 609). In its conventional form, blaming has a negative intention. It is understood as ‘the act of attributing something considered to be bad or wrong to some person or entity’ (Hood Citation2011: 6). Political actors try to find a scapegoat for mistakes, failures, and problems in front of voters. As an opportunistic behaviour, blaming implies the flexible adaptation to situational opportunities and the prioritisation of short-term advantages over long-term losses (Williamson Citation1993: 98). However, it risks that scapegoats fight back. Then, blame senders lose credibility in their political networks (Moynihan Citation2012: 577).

Blame attribution strategies are determined by the specific institutional setting in which the actors operate (De Ruiter and Kuipers Citation2022; Hinterleitner Citation2020: 7). In the comparative federalism literature, it is well established that federal systems comprise multi-dimensional and overly complex institutional settings (Benz and Sonnicksen Citation2021), in which the single institutional dimensions set conflicting incentives. Political parties ‘… are one of the very important political actors that produce the linkages between the political institutions’ (Deschouwer Citation2003: 220; see also Burgess Citation2006: 149–156). In their strategic behaviour, party actors must balance cooperative and competitive institutional incentives. In systems of cooperative, strongly intertwined federalism, such as Germany, political actors at both levels of government must work together and find compromises. Federal cooperation prescribes cooperative norms like solidarity, mutual self-restraint, and the duty to act fairly (Burgess Citation2012: 20–21). In Germany, these principles are enshrined as the immanent norm of federal comity (‘Bundestreue’) in the constitution, which makes them legally enforceable (Gaudreault-DesBiens Citation2014: 3–6). The implementation of cooperative principles as well as the actors’ integration into overlapping and mutually enforcing federal and partisan networks require regular consultation and coordination. Multi-level coalition governance also reinforces cooperation. As the party composition of governments at both levels of government diverges, nearly all parties co-govern with parties that are at the same time competitors in other federal entities. These cooperative characteristics are regarded as federal ‘safeguards’ (Bednar Citation2009: 3–5), setting limits to self-serving political behaviour. Hence, we argue that cooperative federalism, which is coupled with party competition, is reflected in a peculiar mix of ‘softer’ and ‘harder’ forms of blaming.

In order to grasp exactly how parties attribute blame to other federal actors and entities in cooperative federalism, we distinguish between two blame attribution strategies: the conventional one, ‘finding a scapegoat’, and a ‘softer’ one which we name here ‘passing responsibility’. Instead of scapegoating others by explicitly highlighting their mistakes and failures, party actors can publicly claim to have inadequate authority to decide upon or implement a policy, passing the responsibility to other federal actors and entities (Harrison Citation1996: 20). Representatives of the parties’ branches in the constituent units may publicly refer to the legal division of authority, highlighting that according to the law, it is up to the federal government to realise a certain policy. Even though this may be in accordance with the facts, this discursive strategy of passing responsibility has two goals. It aims at distracting the audience from the actors’ own role in policy making (Moynihan Citation2012: 576). Considering that citizens often do not know which federal unit is to hold accountable, while joint decisions tend to blur responsibilities, the strategy is also a method to avoid incorrect assignments of who is in charge for what. Nonetheless, it reflects a rather neutral responsibility attribution that may include legalistic arguments on the formal allocation of federal competences. Therefore, this strategy allows parties to attribute blame without directly attacking others.

In the next step, we further contextualise the conceptual framework and derive hypotheses to be tested in the empirical part below.

Hypotheses

There are several assumptions on how parties employ these two discursive blame attribution strategies. Firstly, we assume that the choice hinges on the extent to which parties have government responsibility. All federations are characterised by ‘an ongoing process of intergovernmental relations at all levels of government and administration, from the lower echelons of the civil service all the way up to first ministers’ (Hueglin and Fenna Citation2015: 37). Intergovernmental coordination became particularly important in the management of the Covid-19 crisis (Chattopadhyay and Knüpling Citation2021: 277). The members of the executive branch of government at both levels participate in various formal and informal organisational bodies to ensure dialogue, coordination, and collaboration, including the lower administrative echelons, but also minister and prime minister conferences (Behnke and Mueller Citation2017).

Playing iterated games (Axelrod Citation1984), federal executives need to adhere to the (constitutional) principles of fairness and mutual consideration in intergovernmental coordination bodies. This tends to counteract defective behaviour as interdependent actors need to consider the interests of other relevant actors before finalising their strategies (Kropp Citation2021: 138). It is tricky for the parties involved in intergovernmental bodies to publicly delegitimise their decisions or to scapegoat decision-makers in other federal jurisdictions with whom their representatives collaborate. As far as party actors participate in intergovernmental coordination, we assume them to resort more often to the discursive strategy of passing responsibility, even in times of a prolonged crisis.

Hypothesis 1

a: The stronger the party is integrated into the intergovernmental bodies of cooperative federalism, the more it prefers to employ the discursive strategy of passing responsibility over finding a scapegoat.

In federal systems, parties usually govern and are in the opposition at the same time. Only the representatives of the parties’ governing branches are immediately involved in the bodies of intergovernmental coordination, however. Accordingly, parties themselves must balance conflicting – cooperative and competitive – institutional incentives within their organisation. Therefore, we expect not only differences in the choice of the discursive strategies between parties, but also within parties.

Hypothesis 1

b: The parties’ governing branches are more likely to employ the discursive strategy of passing responsibility than their opposition branches.

Secondly, we expect that the vertical integration of the party system affects which federal actors and entities the parties target in their blame attribution strategies. Vertical integration implies that the party organisation exists at all levels of government, while its different branches are interdependent (Thorlakson Citation2013: 714). Filippov et al. (Citation2004: 192) suggest specific criteria for integrated parties, taking account of both organisational and behavioural characteristics. Crucially, they argue that all branches and candidates contribute to and benefit from the party’s overall success. This makes defection from the party organisation costly. Even in the competition with others, defection undermines the prospects of success for the party in its entirety and thus also for the individual branches and candidates. Therefore, vertically integrated party systems, such as Germany, incentivise party leaders to stick together across levels and constituent units (Detterbeck and Jeffery Citation2009: 71; Wibbels Citation2006: 176) and, at the same time, to attribute blame to the competitors in other federal entities.

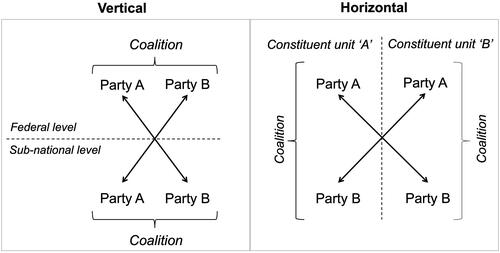

This tactic can provide electoral advantages to co-partisans in other federal entities, contributing to the overall success of the party organisation. Attributing blame to partisan competitors in other federal entities may also reflect negatively on its candidates at home, strengthening one’s own electoral position. If party composition of government differs across territorial levels and federal entities, the multi-level setting allows for targeting coalition partners (). The leaders of coalition partner ‘A’ may attribute blame to specific actors or entities affiliated with coalition partner ‘B’ at the other level of government or in other constituent units (and vice versa).

Figure 1. Attributing blame to coalition partners in multiparty federal systems.

Source: Own depiction.

Hypothesis 2

a: Parties are more likely to attribute blame to their partisan competitors than to their co-partisans in other federal entities.

However, there are also limits to cross-level party cohesion. Regional diversity and federal structures create ‘contradictory pressures on parties that will tend to undermine internal party cohesion’ (Chandler and Chandler Citation1987: 89). Across jurisdictions, party leaders need to cater to distinct territorial demands, taking account of geographic or socio-demographic characteristics, the structure of the economy, or the fiscal capacity. In Germany, regional disparities between the constituent units (Länder) have increased since reunification and amplified territorial conflicts over the allocation of responsibilities and finances (Auel Citation2014: 424; Weichlein Citation2019: 190–191).

Moreover, in multi-level systems, ‘political parties operate simultaneously in different party systems and different institutional settings, hold varying weights therein and often need to strike deals with possibly different partners at different levels’ (Ştefuriuc Citation2009: 1–2). This becomes particularly important in parliamentary democracies that are characterised by multiparty governments (Martin and Vanberg Citation2014). If party systems become more fragmented, parties regularly form coalitions with changing partners across federal entities. As the leaders of the party branches must consider the preferences of their respective coalition partners (Detterbeck Citation2016: 648, 650), the diversity of positions within the multilevel party organisations tends to increase in multicoloured coalition systems.

According to Filippov et al. (Citation2004: 192), integrated party organisations equip their candidates at the lower tier of government with ‘sufficient autonomy to direct their own campaigns and to defect from the national party.’ Taking account of distinct regional circumstances or coalition politics, the leaders of sub-national party branches who run election campaigns may use this leeway to distance themselves from the national party organisation (Kropp Citation2021: 127–128), especially in times of crisis.

Hypothesis 2

b: If they run an election campaign, sub-national party branches are more likely to attribute blame to their co-partisans in other federal entities.

Finally, we expect that sub-national party actors prefer to attribute blame to the federal level. For the European Union, Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl (Citation2020: 964) emphasise that ‘due to their loyalty and interdependence, policymakers located on the same level of government tend to share a preference for shifting blame for contested policies onto actors on another level’. We argue that this assumption also applies to federal systems with close horizontal cooperation and coordination structures like Germany (Behnke and Mueller Citation2017; Hegele Citation2018). Beyond that, politicians at the federal level are usually better known across the territory of the federation than their sub-national counterparts. They are more strongly associated with their respective party, making them the favoured target in political debates. At the same time, it is a more promising strategy for sub-national party actors to hold federal actors accountable for wanting performance, which negatively affects their constituent unit. Whereas regional politicians primarily take care of the issues in their constituent units, federal actors bear responsibility for the federation in its entirety, including the sub-national level.

Hypothesis 3:

Sub-national party branches are more likely to attribute blame to the federal level than to other constituent units.

The Covid-19 crisis created a unique opportunity to test these hypotheses. Not only were the measures to contain the virus controversially debated by the parties in the Länder and the state parliaments. The distribution of responsibilities and federal management of the crisis as well as federalism itself also became highly contested issues that were subject of debate.

The federal management of the Covid-19 crisis in Germany

In Germany, the response to the Covid-19 pandemic was characterised by intertwined responsibilities and joint decision making of the federal government and the Länder. Many responsibilities, among others the restrictions to the freedom of assembly, the imposition of curfews, as well as the closure of restaurants, stores, and schools, fell under the responsibility of the Länder. Empowered by the federal ‘Infection Protection Act’ (‘Infektionsschutzgesetz’, IfSG)Footnote3 and a Bundestag resolution adopting an ‘epidemic situation of national scope’, the Länder governments implemented public measures required to contain infections. The federal government remained responsible for border controls and international travel, and it initiated large-scale financial aid packages for the economy (Kropp and Schnabel Citation2022: 88–91). The federal government and the Länder jointly organised the infrastructure for Covid-19 testing and vaccination.

To facilitate a harmonised policy response, decision-makers quickly turned to a well-established body for intergovernmental coordination: the ‘Conference of the Minister Presidents of the Länder’ (‘Ministerpräsidentenkonferenz’, MPK) that deals with ‘… matters requiring cross-sectoral coordination as well as matters of elevated political significance’ (Hegele and Behnke Citation2017: 536). Together with the chancellor, the MPK met regularly to find a common political response to the pandemic (Schnabel et al. Citation2022). The MPK is a telling example of the close linkage between the federal system and party competition in German politics. The minister presidents are both the chief representatives of their Länder and members of their parties’ leadership (Detterbeck Citation2011: 253–255). The composition of the MPK is truly multi-partisan. In our investigation period, it assembled six minister presidents of the CDU (Christian Democratic Union of Germany) and one of the CSU (Christian Social Union in Bavaria), seven of the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany), and one each of the Greens (Alliance 90/The Greens) and the Left Party. The minister presidents led different coalition governments in the Länder, so the 16 cabinets had 14 different configurations. Except for the right-wing AfD (Alternative for Germany), all parties represented in the Bundestag governed at the sub-national level (Höhne Citation2022: 635). The MPK agreed with the chancellor on the guidelines for crisis management that were administered and implemented by the Länder.

During this investigation period from February 2020 to September 2021, there were different periods and strength of political contention. In the first phase of the pandemic, there was a rally-round-the-flag effect. Governments received high approval rates, and their actions in crisis management enjoyed large public support (Dietz et al. Citation2021). The situation changed in autumn 2020 when Germany experienced its second Covid-19 wave. The actual differences of Covid-19-related restrictions and measures between the Länder remained modest (Behnke and Person Citation2022: 72). Nevertheless, in their public communication, Länder politicians increasingly tried to stand out from federal crisis management and put their spin on joint decisions. Some minister presidents also deviated from the joint agreements of the MPK with the chancellor (Kropp and Schnabel Citation2022: 86). This process became amplified in the winter when federal crisis management was characterised by growing public dissatisfaction and public conflicts between politicians in the media. During the third Covid-19 wave, starting in February 2021, the federal government and the Länder hardly found any common ground. In addition to problem pressure, the third Covid-19 was characterised by extraordinary political mistakes and failures, further undermining the public confidence in federal decision making and its problem-solving capacity. Accordingly, we also examine how parties employed different blame attribution strategies during these three waves of the pandemic.

Data and methods

In order to test the hypotheses empirically, we draw on parliamentary debates in the Bundestag and the 16 Landtage. The case selection includes all 212 parliamentary debates of government declarations and briefings to the parliamentsFootnote4 on the management of the Covid-19 pandemic between 1 February 2020 and the federal election on 26 September 2021. These debates are particularly interesting for the analysis of parties’ discursive strategies towards federal decision making. Taking place shortly before or after the meetings of the MPK with the chancellor, the debates set the stage for party representatives at both levels of government to explain their positions and decisions to the public.

For the qualitative content analysis, we draw on Kukartz (Citation2014: Chapter 4) who suggests breaking down the research process into several steps. Starting from the premises that blame is inevitable in the pandemic (Flinders Citation2020), and federalism has played an important role in crisis management (Hegele and Schnabel Citation2021), we initially scrutinised a smaller sample of debates in different parliaments to get a first impression of discursive strategies. Based on a thorough review of the literature on political strategies and blame avoidance behaviour (e.g., Hinterleitner Citation2017, Citation2020; König and Wenzelburger Citation2014; Moynihan Citation2012; Weaver Citation1986), statements which blame the federal system, specific federal bodies or institutions, and actors at the other tier of government or in the other Länder were then highlighted, commented on, and discussed. In the next steps, we defined the two discursive blaming strategies – finding a scapegoat and passing responsibility –, tested them for plausibility on a larger sample of debates, specified the coding instructions, and determined typical examples for each strategy (). Finally, all 212 debates were coded. Throughout the coding process, we conducted reliability checks,Footnote5 and each coded statement was checked by (at least) one second coder.

Table 1. Examples of discursive blaming strategies.

Overall, we coded 2067 statements (135 in the Bundestag and 1932 in the Landtage) and integrated them into a new dataset. Beyond the statement itself, the dataset comprises information on the blame sender and the blame target, the discursive strategy, and the context in which the statement was made, such as date and parliament. The blame sender is the party of the speakers in the debate.Footnote6 We focus on the parties which are represented in the Bundestag: the CDU/CSU,Footnote7 the SPD, the Greens, the FDP, the Left Party, and the AfD. Blame targets are the actors and entities in the federal system that are blamed or held responsible in the statements.

Evaluating the statements, we found a variety of blame targets which we added in an additional inductive step to the coding scheme (Kukartz Citation2014: 70). We distinguished between actor-related and functional targets. On the one hand, actor-related targets comprise the federal cabinet (‘Bundesregierung’) and politicians, a specific Land, politicians in the Länder as well as the MPK as a distinct collective actor in federal crisis management. In the statement in , for example, Raed Saleh (SPD) explicitly blames Jens Spahn, the federal health minister of the CDU. On the other hand, there are functional targets: the federal government (‘Bund’), the federal level (‘Bundesebene’), the federal legislature (‘Bundesgesetzgeber’), the Länder in their entirety, and both the federal government and the Länder (‘Bund und Länder’). In the statement in , Bavarian minister president Markus Söder (CSU) refers to the federal government (‘Bund’) instead of a specific actor. Distinguishing between actor-related and functional targets allows us to point out how party actors soften blame attribution strategies by referring to more general legalistic terms.

Empirical analysis

Blame attribution strategies and government responsibility

In hypothesis 1a, we assume that the choice of discursive strategies depends on the extent to which the parties are integrated into to the bodies of cooperative federalism. Strongly integrated parties are expected to prefer the discursive strategy of passing responsibility over finding a scapegoat. In Germany, the degree of integration varies across parties. SPD, CDU/CSU, and the Greens are the most strongly integrated group. Within our investigation period, SPD and CDU/CSU formed the federal cabinet and were senior coalition partner in seven state cabinets. The CDU was junior coalition partner in another three state cabinets, the SPD in four. The Greens were junior coalition partner in ten (after the elections in Saxony-Anhalt in June 2021 nine) state cabinets and senior coalition partner in Baden-Württemberg.

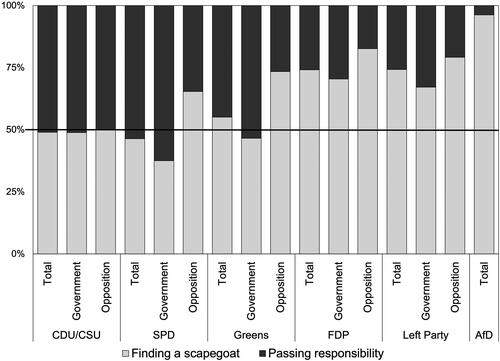

To test how integration into bodies of cooperative federalism and government/opposition-status shapes parties’ discursive strategies, we calculated the relative share of the two blame attribution strategies for each party, for all governing branches of the party, and for all opposition branches of the party. The results in only partially confirm our hypothesis. Pooling all statements we coded for each party, SPD and CDU/CSU prefer to pass responsibility over finding scapegoats. In the Länder, their party leaders primarily used the strategy of passing responsibility to underline the authority of the federal government for policy measures, such as the (federal) financial aid for companies affected by the Covid-19 lockdown in winter 2020 (‘Novemberhilfe’). For example, the CDU in the Saarland made clear that the federal government is expected ‘to implement this aid swiftly and in a timely manner’ (Landtag des Saarlands, plenary protocol 26/43: 3183; translation by the authors). At the federal level, SPD and CDU/CSU highlighted the responsibility of the Länder to administer and implement policies, for example home-schooling regulations. According to the SPD in the Bundestag, it was up to the Länder to create appropriate conditions to open schools safely in winter (Bundestag, plenary protocol 19/195: 24586). However, the results are less clear than expected. For the Greens, scapegoating is slightly more pronounced than passing responsibility. Nonetheless, highlights that SPD, CDU/CSU, and Greens hold back on scapegoating other federal actors and entities compared to the other three parties.

Figure 2. Blame attribution strategies of the parties.

Note: The figure presents the relative share of the two blame attribution strategies for each party. ‘Total’ includes all statements coded for each party. ‘Government’ includes the statements only made by the parties’ governing branches. ‘Opposition’ includes the statements only made by the parties’ opposition branches. Cases: 2067 statements; for the cases per party, see online appendix.

Source: Own depiction.

The other group includes the FDP and the Left Party. Both are much less involved into intergovernmental relations. The FDP and the Left party were only part of four Länder governments during our investigation period; the Left Party also provided the premier in Thuringia. As illustrated in , scapegoating is more pronounced in this group compared to SPD, CDU/CSU, and the Greens. The FDP particularly targeted chancellor Angela Merkel. Whereas the FDP lobbied to relax the Covid-19-restrictions, the chancellor constantly warned against opening too quickly. The FDP blamed Merkel as the main reason for what it saw as mismanagement of the crisis. Party leaders also used anti-elitist argumentation. When Merkel proposed to extend the Covid-19 lockdown in February 2021, the parliamentary group leader of the FDP in North Rhine-Westphalia emphasised that the citizens would not understand the chancellor’s policies anymore (Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen, plenary protocol 17/117: 18) and would ‘freak out’ due to her policy proposals (Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen, plenary protocol 17/121: 25; translation by the authors).

The FDP did not only blame the decisions of the MPK in federal crisis management but also questioned its legitimacy. The parliamentary group leader of the FDP in Bavaria, for example, referred to the MPK as a ‘round of haggling [Kungelrunde] that our constitution does not even know about’ (Bayerischer Landtag, plenary protocol 18/78: 10158; translation by the authors), while his counterpart in Baden-Württemberg named it ‘a kind of oriental bazaar of the minister presidents’ (Landtag Baden-Württemberg, plenary protocol 16/134: 8369; translation by the authors). By contrast, the Left Party blamed the MPK for not coming up with adequate policy solutions. With the minister president of Thuringia, Bodo Ramelow, the Left Party was – unlike the FDP – part of the MPK. The representatives of the Left Party did not question the legitimacy of federal coordination and decision making (see also Lewandowsky et al. Citation2022: 243). They rather criticised the outcomes and decisions of the MPK to cater to industry and business interests and fail to protect workers and employees (e.g., Berliner Abgeordnetenhaus, plenary protocol 18/76: 8909f.).

The AfD has not been involved in any government and is, therefore, an ‘outsider’ in federal coordination. The party leaders clearly preferred scapegoating over passing responsibility, which hardly played a role in their communication at all. In the first weeks of the pandemic, the AfD criticised that measures to contain the virus, especially travel bans, were implemented too slowly (e.g., Hessischer Landtag, plenary protocol 20/36: 2772; Landtag Brandenburg, plenary protocol 7/11: 7). The statements were in line with the party’s general anti-immigration and anti-asylum positions (see also Lehmann and Zehnter Citation2022: 8). The AfD quickly changed its course and begun to display hostility to science, downplaying the health risks of Covid-19, and scapegoated the federal cabinet, the chancellor, and the decision-makers in the Länder for what it saw as incompetence to manage the crisis.

Party leaders of the AfD tried to integrate these statements into a broader ‘narrative of democracy under threat by the elites’ (Lewandowsky et al. Citation2022: 242). The parliamentary group leader in Brandenburg, for example, argued that ‘the epidemic cabinet [Seuchenkabinett] in the Chancellor’s Office administers in the manner of the Politburo and implements unreasonable and – what is even worse – harmful measures’ (Landtag Brandenburg, plenary protocol 7/23: 5; translation by the authors). The wording is used to evoke associations with the non-democratic rule during the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). In this context, the AfD particularly aimed at the MPK. According to its parliamentary group leader in Berlin, the MPK was equivalent to ‘a Central Committee, which is not mentioned as a constitutional body either in the Basic Law or anywhere else’ (Abgeordnetenhaus Berlin, plenary protocol 18/69: 8211; translation by the authors), again playing on a narrative that undermines the democratic legitimacy of coordinative federal bodies by referring to the regime in the GDR.

Except for the AfD, all parties represented in the Bundestag govern in some federal jurisdictions, while they are in the opposition in others. We calculated the distribution of statements for the two strategies separately for the parties’ governing and opposition branches. The results are also presented in . As expected in hypothesis 1b, most parties prefer to employ the discursive strategy of passing responsibility when they are part of the government. The finding is clearest for the SPD and the Greens. For the FDP and the Left Party, the assumption still applies, but the differences between government and opposition branches are not as pronounced as expected. Finding scapegoats is a popular discursive strategy even for the governing branches of the FDP and the Left Party. For the CDU/CSU, the data reveal almost no differences between the governing and opposition branches. Either way, the share of statements for passing responsibility is slightly higher than the one for scapegoating.

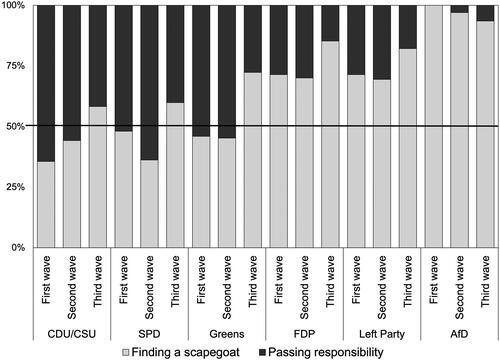

The data cover the first three Covid-19 waves in Germany.Footnote8 For the data analysis, we proceeded by calculating the relative share of the two blame attribution strategies for all parties in each of three waves. Remarkably, the SPD, the CDU/CSU, and the Greens prefer the discursive strategy of passing responsibility in the first Covid-19 wave and still in the second one – despite growing political tensions and public discontent among the citizens (). Only in the third Covid-19 wave, the data reveal a relatively higher share of scapegoating for the three parties. A particularly contested event was the so-called ‘Osterruhe’, a harsh lockdown on Easter 2021. The chancellor proposed the measure to the minister presidents who eventually agreed at an all-night negotiation. However, it had to be taken back shortly afterwards due to lack of feasibility, leading to a situation of pointing finger at each other whose fault it was. Unsurprisingly, the FDP, the Left Party, and the AfD strongly engaged in finding scapegoats in all three Covid-19 waves.

Figure 3. Blame attribution strategies during the first three Covid-19 waves.

Note: The figure presents the relative share of the two blame attribution strategies for each party in the three Covid-19 waves covered in the dataset. We calculated the relative number of statements in each category for each party in each of the three Covid-19 waves under analysis. To determine the exact time periods of the three Covid-19 waves, we refer to the official information of the Robert Koch-Institute (Tolksdorf et al. Citation2021). The first wave lasted from 02 March 2020 to 17 May 2020, the second wave from 28 September 2020 to 28 January 2021, and the third wave from 01 February 2021 to 13 June 2021. Cases: 1933 statements; for the cases per party, see the online appendix.

Source: Own depiction.

Party competition and cohesion

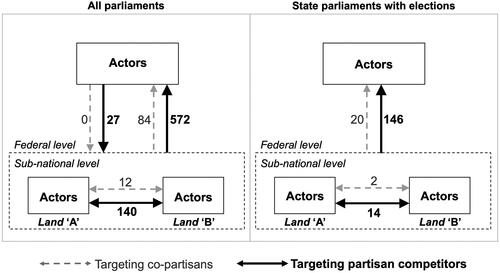

Due to the multi-level party competition and the integrated party system, we expect the parties to attribute blame to their competitors at the other level of government and in other constituent units. For the analysis, we selected the 835 statements we coded for the two blame attribution strategies which include blame targets with a single and distinct party affiliation. We then determined the party affiliation of the blame targets in relation to the one of the blame senders.Footnote9 presents the results. The data confirm hypothesis 2a that co-partisans are less frequently targeted than partisan competitors. The by far most frequent strategy, used in 69% of all coded statements, is to blame partisan competitors at the federal level. The second, though with 17% of all statements much less frequently used strategy, focuses on targeting partisan competitors at the sub-national level. Conversely, co-partisans are rarely, if ever, targeted. Federal party leaders do not aim at their co-partisans in the Länder at all, and even sub-national party leaders refer to co-partisans in other constituent units exceptionally rarely, with less than 2% of all coded statements falling into this category. Interestingly, these findings even apply to the CDU/CSU, where executives at both levels of government vied to become the successor to chancellor Merkel (Bandelow et al. Citation2021: 129). Our data thus reveal that party actors of the CDU/CSU refrained from engaging in intra-party blame games, at least in parliamentary debates.

Figure 4. Blame attribution in multi-level party competition: targeting co-partisans and partisan competitors in other federal entities.

Note: The figure presents absolute numbers of statements (both blame attribution strategies) which target actors with distinct party affiliation. Numbers are presented for all parliaments (Bundestag and 16 state parliaments) as well as the five state parliaments which held elections within our investigation period. Cases: 835 statements for all parliaments; 182 statements for the state parliaments with elections.

Source: Own depiction.

We find similar restraints during electoral campaigns. Contrary to our expectation, the data do not support hypothesis 2b. Sub-national party branches refrain from targeting co-partisans at the federal level or in other constituent units during election campaigns. shows the results for the five LänderFootnote10 which held elections within our investigation period. Party cohesion remains in force despite the prolonged Covid-19 crisis and election campaigns.

Partisan competitors are targeted even if the parties govern together in coalitions. For example, representatives of the Left Party in Berlin, which participated there in the SPD-led government, accused the federal finance minister of the Social Democrats for failures to support artists during the pandemic. They argued that a famous artist had to make the finance minister aware of the precarious situation of the cultural industry (Berliner Abgeordnetenhaus, plenary protocol 18/65: 7824). These federal blame games between coalition partners are particularly interesting when looking at the SPD and the CDU/CSU which governed together at the federal level. When scapegoating actors at the federal, we find for these two parties only six statements in all state parliaments that aim at a co-partisan. On the other hand, there are 83 statements, in which an actor from the other party, respectively, is scapegoated. The federal ‘Novemberhilfe’ for companies affected by the Covid-19 lockdown was jointly organised by the federal ministry of economy and the federal ministry of finance. As the disbursement to companies was delayed, the ‘Novemberhilfe’ became a controversial topic in the political debate. At the sub-national level, the SPD accused the federal minister of the economy (CDU), while the CDU/CSU blamed the federal finance minister of the Social Democrats.

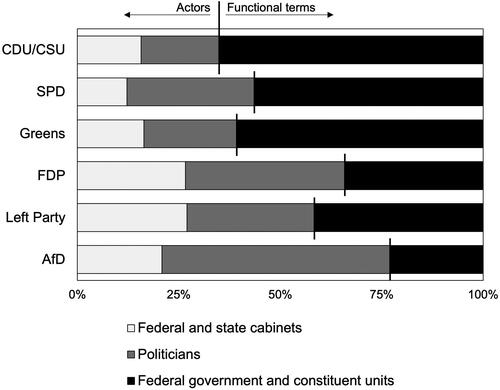

Finally, and most importantly, our coding reveals another discursive strategy that is particularly relevant in the context of coalition dynamics. Parties which are part of several coalitions hold back from targeting specific actors, i.e., cabinets or politicians, in their blame attribution strategies. Instead, they choose a ‘softer’ form of blaming, using the ‘functional’ terms inherent to the language of federalism in their argumentation. For example, parties in the Länder may refer to the federal government, the federal level, or the federal legislature (‘Bund’, ‘Bundesebene’, ‘Bundesgesetzgeber’) instead of the federal cabinet (‘Bundesregierung’). This strategy, which we name ‘blurring the blame target’, is especially common for the SPD, the CDU/CSU, and the Greens, which employ this discursive tactic to spare co-partisans and coalition partners. By contrast, the FDP, the Left Party, and the AfD prefer to target federal and state cabinets as well as politicians () more explicitly.

Figure 5. ‘Blurring the blame target’ – actor-specific versus functional terms in target descriptions by party.

Note: The figure presents the relative number of statements referring to specific actors (federal and state cabinets or specific politicians) versus more diffuse and blurry references using functional terms associated with the legal language of federalism, broken down for each party. Cases: 1633 statements.

Source: Own depiction.

The direction of blame attribution

In hypothesis 3, we assume that actors of the sub-national party branches are more likely to attribute blame to the federal level. For all 1932 statements we coded for the party branches in the Länder, we determined whether the blame target is located at the federal level or at the sub-national level. In addition, there is a third category, comprising targets which cut across the two levels of government and thus cannot be assigned to either one of them. This third category includes statements that refer to both the federal government and the constituent units (‘Bund und Länder’) and to the MPK. Whereas the MPK is normally a body of horizontal coordination between the Länder, the chancellor (and sometimes other members of the federal cabinet) assumed a greater role in the MPK meetings in the Covid-19 crisis. During the pandemic, the MPK appeared as a joint body of the federal government and the Länder (Waldhoff Citation2021: 2774).

The data clearly confirm hypothesis 3. With a relative share of 53%, blame targets at the federal level are by far the most prominent ones. Actors of the sub-national party branches are more likely to attribute blame to the federal level. At the same time, the party actors in the Länder largely spare each other. In only 18% of their statements, blame is attributed horizontally between sub-national actors and entities. This corroborates a more general observation that there is a sense of belonging together among the Länder. In the rest of the cases (29%), parties refer to the targets which cut across the two levels of government.

Conclusions

This analysis has focused on how party actors align their behaviour with cooperative federal institutions that include conflicting incentive structures. The German federal system was consulted as a particularly instructive case, since cooperative federalism, shaped by highly intertwined responsibilities, is linked with a multicoloured coalition landscape. While these elements strengthen incentives for cooperation, they are at the same time tightly coupled with party competition in the parliamentary arena. The study shows that party actors use the multi-level structure to attribute blame to other actors. At the same time, they are obliged to cooperate within overlapping intergovernmental and party networks and be considerate towards competing actors.

Our findings allow for reasoning about the robustness of federal institutions. Firstly, we have shown that blame attribution is a concept that requires more thorough elaboration. The initial concept of ‘blaming’, which mostly refers to the strategy of scapegoating, is too narrow to grasp the variety of extant strategies. Party actors align their discursive behaviour precisely to the particular institutional setting. As the German federal system necessitates constant cooperation, and even prescribes federal comity as an immanent constitutional norm, this study distinguished between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ blaming strategies. We investigated the classical ‘scapegoating’ – blaming others explicitly for mistakes, failures, and problems in front of an audience – and operationalised a second, ‘softer’ strategy which we named ‘passing responsibility’. The latter is employed by party actors to point out that other actors are in charge. The qualitative coding used in this study also allowed for the discovery of a third, so far undetected ‘soft’ argumentative pattern, which we name ‘blurring the blame target’. Party actors involved in coalitions across the federation hold back from targeting specific individual or collective actors, such as the chancellor or the federal cabinet (‘Bundesregierung’), in their discursive strategies. Instead, they refer to the functional terms which denote the federal level more generally (‘Bund’, ‘Bundesebene’, ‘Bundesgesetzgeber’). Therefore, the legalistic language of federalism, which revolves around the attribution of responsibilities to federal jurisdictions according to the constitution and the laws, helps to spare co-partisans in office. It seems plausible that party actors in other cooperative federal systems use similar strategies, which are carefully tailored to the specific institutional context.

A second conclusion addresses the differences between the parties. Party actors which bear government responsibility are involved in widely institutionalised intergovernmental bodies. Being part of government seems to restrain ‘hard’ blaming strategies. The German intergovernmental institutions are shaped by a unique linkage of cooperative federalism and multicoloured coalition government at both federal levels. Those parties, which are not (AfD) or only selectively involved in coalitions at both levels of government (FDP, the Left Party) and therefore largely outside the intergovernmental bodies of cooperative federalism, are significantly more engaged in conventional scapegoating. On the other hand, CDU/CSU, SPD, and the Greens resort more strongly to ‘softer’ blame attribution strategies. Cooperative institutions, where competing party actors are continually forced to collaborate, curb potentially defective behaviour of political elites by which actors would risk losing credibility in their political networks (Moynihan Citation2012). In terms of constitutional political economy, the parties’ discourses corroborate that these institutions serve as a ‘safeguard’ against potentially opportunistic behaviour (Bednar Citation2009).

Thirdly, the study underlined that parties choose the targets of their discursive strategies prudently. Parties at the federal level take the chance to attribute blame to the Länder, while sub-national party leaders mostly aim at political actors at the federal level which are well-known across the federation and more strongly associated with their respective party. Party actors attribute blame to co-partisans in other federal entities only in exceptional cases. Our findings reveal that party cohesion largely persisted – even in the prolonged Covid-19 crisis. The vertically integrated party system, which is a central feature of the German federal system, also seems to create an effective ‘blame barrier’ (De Ruiter and Kuipers Citation2022).

Finally, it was surprising that no increase of scapegoating as the ‘harder’ form of blaming during the election campaigns run in 2021 could be found. This might be explained by the increasing volatility and the changing composition of coalition governments, which complicates reliable assessments of which coalition can be formed after elections. Today, parties are forced to form coalitions with competitors having different, even contrary policy positions, and therefore conduct electoral campaigns that are not just ambiguous in terms of policy position (van de Wardt et al. Citation2014), but also in terms of blame attribution. We therefore conclude that the vertically integrated party systems in combination with the cooperative federal institutions and the differentiated coalition landscape form a system of overlapping ‘safeguards’ (Bednar Citation2009: 3–5) and together constitute an effective ‘safety net’.

We are aware that the pandemic created a specific context that cannot be equated with everyday policy making. After the initial shock in 2020, which created a rally-round-the-flag effect (Dietz et al. Citation2021), federalism and federal decision making were at the centre of public conflicts and fierce debates rarely seen before. The pandemic became a stress test for the federal system. Accordingly, the data reveal that during the third wave, when the infection rates were deteriorating, the ‘hard’ strategy of scapegoating became more prevalent in the debates. Even the parties which bear the lion’s share of government responsibility (CDU/CSU and SPD) more frequently engaged in scapegoating than during the first and second Covid-19 wave. Hence, the data indicate that even strong and overlapping institutional safeguards are not immune against defection if they come under enduring pressure.

The study provides a parsimonious framework of investigation. It can – and should – be expanded and amended for further comparative inquiry. In many federal systems, for example in Canada or Belgium, party systems are not vertically integrated or even truncated. Analysing blame attribution strategies in federal systems with less integrated party systems will be an instructive avenue for further comparative research. Furthermore, coalitions do not exist or are not as multicoloured in other federal countries, and federal institutions are in most cases less intertwined than in the German case. Therefore, it is likely that scholars might discover different forms of blame attribution strategies or functional equivalents. In short, a rich research agenda exists to explore how actors exploit the varying incentives of federal settings, allowing the gathering of insights in the robustness of federal institutions in times of crisis.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (197.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the two reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments on earlier versions of this article and Akseli Paillette-Liettilä, Jonathan Röders, Polina Khubbeeva, Yannis Wittig, and Marek Wessels for their valuable research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antonios Souris

Antonios Souris is Postdoctoral Researcher at the Chair of German Politics at Freie Universität Berlin. In his dissertation, he investigated EU policy coordination in Germany’s federal system. His research focuses on comparative federalism, parliaments, and the policy areas of transport and housing. [[email protected]]

Sabine Kropp

Sabine Kropp is Professor of German Politics at Freie Universität Berlin. Her primary field of research is comparative federalism and multilevel politics, parliamentarism and public administration, with an emphasis on Germany and post-Soviet countries. Her recent book Emerging Federal Structures in the Post-Cold War Era (co-edited with Soeren Keil, Palgrave Macmillan 2022) investigates emerging and regressing federal structures in unconsolidated federal systems. [[email protected]]

Christoph Nguyen

Christoph Nguyen is Lecturer at the Chair of German Politics at Freie Universität Berlin. He received his PhD from Northwestern University. His research focuses on the intersection between affect, ideas, and politics and the use of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods in political science. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The dataset, codebook, and further project documentation are available at the data repositorium of GESIS: https://doi.org/10.7802/2627.

2 The existing literature uses both the term ‘blame attribution’ and the term ‘responsibility attribution’. While the literature on voters and their perceptions of multilevel systems generally uses the term ‘responsibility’, the more institutionally oriented contributions focus on the term ‘blame’. However, federalism research usually means by the term ‘responsibility’ the legal or constitutional competences of federal entities in federal systems. Therefore, we prefer to use the term ‘blame’ to delineate formal responsibilities from discursive ascriptions.

3 Infection Protection Act of 20 July 2000 (BGBl. I: 1045), last amended by Article 8b of the Act of 20 December 2022 (BGBl. I: 2793).

4 It was not possible to analyse all parliamentary debates on Covid-19. Based on the protocols of the plenary sessions in the Bundestag and the 16 Landtage, we initially marked all procedures related to managing Covid-19 that were debated there between 1 February 2020 and the federal elections on 26 September 2021. In total, we have identified 3117 procedures in this period.

5 Regular discussions as well as the joint specification of definitions and coding instructions ensured a common understanding among the team members on how to code the debates. The Landtage were coded by five coders. Each coder reviewed his or her coded statements after some time and suggested changes to the original coding. This affected about 6% of the cases. These changes were discussed by the team and implemented accordingly. To ensure inter-coder reliability, every tenth debate (total: 21 debates) was again coded by a second coder. The second coder agreed with 78% of the originally coded strategies. Finally, each statement was checked by (at least) a second coder: 8% of the cases were adapted or deleted. The 10 debates in the Bundestag were coded by two coders. Initially, they coded five debates each. They then swapped debates and coded again the other five debates. The results were compared, differences were discussed, and the coding finalised. A third team member eventually checked all coded text sections: 6% of the cases were re-coded or deleted.

6 In Germany, parliamentary party groups determine the deputies who take the floor for them in the debates (Müller et al. Citation2021: 381). Therefore, we can assign the deputies, speaking in the debates, to their respective party. Moreover, we treat the government representatives in the debates as speakers for their parties. This has been decided in the awareness that due to the different roles, the statements of the deputies can be more competitive and polarised than the ones of government representatives.

7 Since the CDU and CSU do not compete at either level of government, and it is not clear whether the speakers in the Bundestag represent only the CDU, CSU, or both due to their joint parliamentary party group, we have decided to consider them together here. Empirically, the CSU is also not an outlier vis-a-vis comparable party branches of the CDU. The CDU’s Länder branches with governing responsibility exhibit 53% for ‘passing responsibility’ and 47% for ‘finding a scapegoat’. Including the CSU, the numbers slightly change to 52% and 48%.

8 To determine the exact time periods of the three Covid-19 waves, we refer to the official information of the Robert Koch-Institute (RKI) (Tolksdorf et al. Citation2021). The RKI is the federal government’s institute for surveillance and prevention of infectious diseases and pandemic preparedness. The first wave lasted from 02 March 2020 to 17 May 2020, the second wave from 28 September 2020 to 28 January 2021, and the third wave from 01 February 2021 to 13 June 2021.

9 When parties refer to a specific Land or Länder, we had to decide how to determine their party affiliation because they are usually governed by a coalition. We use the party affiliation of the respective minister president as distinction. As they represented the Länder in the meetings of the MPK with the chancellor, the minister presidents played the key role in federal crisis management and especially in the media reporting about it. Therefore, citizens primarily associated the Länder with their minister presidents.

10 The five Länder were Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatine, Saxony-Anhalt, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, and Berlin. The elections in Thuringia were postponed to 2024 as the necessary two-thirds majority for the dissolution of the state parliament (Art. 50, 2; Constitution of Thuringia) could not be achieved.

References

- Auel, Katrin (2014). ‘Intergovernmental Relations in German Federalism: Cooperative Federalism, Party Politics and Territorial Conflicts’, Comparative European Politics, 12:4–5, 422–43.

- Axelrod, Robert (1984). The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

- Bach, Tobias, and Kai Wegrich (2019). ‘The Politics of Blame Avoidance in Complex Delegation Structures: The Public Transport Crisis in Berlin’, European Political Science Review, 11:4, 415–31.

- Bandelow, Nils C., Patrick Hassenteufel, and Johanna Hornung (2021). ‘Patterns of Democracy Matter in the COVID-19 Crisis’, International Review of Public Policy, 3:1, 121–36.

- Bednar, Jenna (2009). The Robust Federation. Principles of Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Behnke, Nathalie, and Christian Person (2022). ‘Föderalismus in der Krise – Restriktivität und Variation der Infektionsschutzverordnungen der Länder’, dms – der moderne staat – Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management, 15:1–2022, 62–83.

- Behnke, Nathalie, and Sean Mueller (2017). ‘The Purpose of Intergovernmental Councils: A Framework for Analysis and Comparison’, Regional & Federal Studies, 27:5, 507–27.

- Benz, Arthur (1999). ‘From Unitary to Asymmetric Federalism in Germany: Taking Stock after 50 Years’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 29:4, 55–78.

- Benz, Arthur, and Jared Sonnicksen, eds. (2021). Federal Democracies at Work: Varieties of Complex Government. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

- Burgess, Michael (2006). Comparative Federalism. Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Burgess, Michael (2012). In Search of the Federal Spirit. New Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives in Comparative Federalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chandler, William M., and Marsha A. Chandler (1987). ‘Federalism and Political Parties’, European Journal of Political Economy, 3:1–2, 87–109.

- Chattopadhyay, Rupak, and Felix Knüpling (2021). ‘Comparative Summary’, in Rupak Chattopadhyay, John Light, Felix Knüpling, Diana Chebenova, Liam Whittington, and Phillip Gonzalez (eds.), Federalism and the Response to COVID-19: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge, 277–307.

- Cutler, Fred (2004). ‘Government Responsibility and Electoral Accountability in Federations’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 34:2, 19–38.

- Cutler, Fred (2008). ‘Whodunnit? Voters and Responsibility in Canadian Federalism’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, 41:3, 627–54.

- Däubler, Thomas, Jochen Müller, and Christian Stecker (2018). ‘Assessing Democratic Representation in Multi–Level Democracies’, West European Politics, 41:3, 541–64.

- De Ruiter, Minou, and Sanneke Kuipers (2022). ‘Avoiding Blame in Policy Crises in Different Institutional Settings’, Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Politics. https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1592

- Deschouwer, Kris (2003). ‘Political Parties in Multi-Layered Systems’, European Urban and Regional Studies, 10:3, 213–26.

- Detterbeck, Klaus (2011). ‘Party Careers in Federal Systems. Vertical Linkages Within Austrian, German, Canadian and Australian Parties’, Regional & Federal Studies, 21:2, 245–70.

- Detterbeck, Klaus (2016). ‘The Role of Party and Coalition Politics in Federal Reform’, Regional & Federal Studies, 26:5, 645–66.

- Detterbeck, Klaus, and Charlie Jeffery (2009). ‘Rediscovering the Region: Territorial Politics and Party Organizations in Germany’, in Wilfried Swenden and Bart Maddens (eds.), Territorial Party Politics in Western Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 63–85.

- Dietz, Melanie, Sigrid Roßteutscher, Philipp Scherer, and Lars-Christopher Stövsand (2021). ‘Rally Effect in the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Role of Affectedness, Fear, and Partisanship’, German Politics, 1–21.

- Filippov, Mikhail, Peter C. Ordeshook, and Olga Shvetsova (2004). Designing Federalism: A Theory of Self-Sustainable Federal Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Flinders, Matthew (2020). ‘Gotcha! Coronavirus, Crises and the Politics of Blame Games’, Political Insight, 11:2, 22–5.

- Gaudreault-DesBiens, Jean-François (2014). ‘Cooperative Federalism in Search of a Normative Justification: Considering the Principle of Federal Loyalty’, Constitutional Forum/Forum Constitutionnel, 23:4, 1–19.

- Graham, Matthew H., and Shikhar Singh (2023). ‘Partisan Selectivity and Blame Attribution: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic’, American Political Science Review, 1–19.

- Greer, Scott L., Sarah Rozenblum, Michelle Falkenbach, Olga Löblová, Holly Jarman, Noah Williams, and Matthias Wismar (2022). ‘Centralizing and Decentralizing Governance in the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Politics of Credit and Blame’, Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 126:5, 408–17.

- Harrison, Kathryn (1996). Passing the Buck: Federalism and Canadian Environmental Policy. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Hegele, Yvonne (2018). ‘Multidimensional Interests in Horizontal Intergovernmental Coordination: The Case of the German Bundesrat’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 48:2, 244–68.

- Hegele, Yvonne, and Nathalie Behnke (2017). ‘Horizontal Coordination in Cooperative Federalism: The Purpose of Ministerial Conferences in Germany’, Regional & Federal Studies, 27:5, 529–48.

- Hegele, Yvonne, and Johanna Schnabel (2021). ‘Federalism and the Management of the COVID-19 Crisis: Centralisation, Decentralisation and (Non-)Coordination’, West European Politics, 44:5–6, 1052–76.

- Heinkelmann-Wild, Tim, and Bernhard Zangl (2020). ‘Multilevel Blame Games: Blame–Shifting in the European Union’, Governance, 33:4, 953–69.

- Hinterleitner, Markus (2017). ‘Reconciling Perspectives on Blame Avoidance Behaviour’, Political Studies Review, 15:2, 243–54.

- Hinterleitner, Markus (2020). Policy Controversies and Political Blame Games. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hinterleitner, Markus, Céline Honegger, and Fritz Sager (2023). ‘Blame Avoidance in Hard Times: Complex Governance Structures and the COVID-19 Pandemic’, West European Politics, 46:2, 324–46.

- Hood, Christopher (2011). The Blame Game: Spin, Bureaucracy and Self-Preservation in Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Höhne, Benjamin (2022). ‘Die Landesparlamente im Zeichen der Emergency Politics in der Corona-Krise’, Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 32:3, 627–53.

- Hueglin, Thomas O., and Alan Fenna (2015). Comparative Federalism: A Systematic Inquiry. 2nd edition. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

- Jin, Rongbo, Alexander Cloudt, Seoungin Choi, Zhuofan Jia, and Samara Klar (2023). ‘The Policy Blame Game: How Polarization Distorts Democratic Accountability across the Local, State, and Federal Level’, State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 23:1, 1–25.

- Kennedy, John, Anthony Sayers, and Christopher Alcantara (2022). ‘Does Federalism Prevent Democratic Accountability? Assigning Responsibility for Rates of COVID-19 Testing’, Political Studies Review, 20:1, 158–65.

- König, Pascal D., and Georg Wenzelburger (2014). ‘Toward a Theory of Political Strategy in Policy Analysis’, Politics & Policy, 42:3, 400–30.

- Kropp, Sabine (2021). ‘Germany: How Federalism Has Shaped Consensus Democracy’, in Arthur Benz and Jared Sonnicksen (eds.), Federal Democracies at Work: Varieties of Complex Government. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 122–42.

- Kropp, Sabine, and Johanna Schnabel (2022). ‘Germany’s Response to COVID-19: Federal Coordination and Executive Politics’, in Rupak Chattopadhyay, John Light, Felix Knüpling, Diana Chebenova, Liam Whittington, and Phillip Gonzalez (eds.), Federalism and the Response to COVID-19: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge, 84–94.

- Kukartz, Udo (2014). Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software. London: Sage.

- Lehmann, Pola, and Lisa Zehnter (2022). ‘The Self-Proclaimed Defender of Freedom: The AfD and the Pandemic’, Government and Opposition, 1–19.

- Lehmbruch, Gerhard (2000). Parteienwettbewerb im Bundesstaat: Regelsysteme und Spannungslagen im politischen System der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. 3rd edition. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- León, Sandra, Ignacio Jurado, and Amuitz Garmendia Madariaga (2018). ‘Passing the Buck? Responsibility Attribution and Cognitive Bias in Multilevel Democracies’, West European Politics, 41:3, 660–82.

- Lewandowsky, Marcel, Christoph Leonhardt, and Andreas Blätte (2022). ‘Germany. The Alternative for Germany in the COVID-19 Pandemic’, in Nils Ringe and Licio Rennó (eds.), Populists and the Pandemic: How Populists Around the World Responded to COVID-19. London: Routledge, 238–49.

- Maestas, Cherie D., Lonna Rae Atkeson, Thomas Croom, Lisa, and A. Bryant (2008). ‘Shifting the Blame: Federalism, Media, and Public Assignment of Blame Following Hurricane Katrina’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 38:4, 609–32.

- Malhotra, Neil (2008). ‘Partisan Polarization and Blame Attribution in a Federal System: The Case of Hurricane Katrina’, Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 38:4, 651–70.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2014). ‘Parties and Policymaking in Multiparty Governments: The Legislative Median, Ministerial Autonomy, and the Coalition Compromise’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 979–96.

- Moynihan, Donald P. (2012). ‘Extra-Network Organizational Reputation and Blame Avoidance in Networks: The Hurricane Katrina Example’, Governance, 25:4, 567–88.

- Müller, Jochen, Christian Stecker, and Andreas Blätte (2021). ‘Germany. Strong Party Groups and Debates among Policy Specialists’, in Hanna Bäck, Marc Debus, and Jorge M. Fernandes (eds.), The Politics of Legislative Debates. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 376–98.

- Rico, Guillem, and Robert Liñeira (2018). ‘Pass the Buck If You Can: How Partisan Competition Triggers Attribution Bias in Multilevel Democracies’, Political Behavior, 40:1, 175–96.

- Schlipphak, Bernd, Paul Meiners, Oliver Treib, and Constantin Schäfer (2023). ‘When Are Governmental Blaming Strategies Effective? How Blame, Source and Trust Effects Shape Citizens’ Acceptance of EU Sanctions Against Democratic Backsliding’, Journal of European Public Policy, 30:9, 1715–37.

- Schmidt, Vivien A. (2008). ‘Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse’, Annual Review of Political Science, 11:1, 303–26.

- Schnabel, Johanna, Rahel Freiburghaus, and Yvonne Hegele (2022). ‘Crisis Management in Federal States: The Role of Peak Intergovernmental Councils in Germany and Switzerland During the COVID-19 Pandemic’, dms – der moderne staat – Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management, 15:1–2022, 42–61.

- Ştefuriuc, Irina (2009). ‘Introduction: Government Coalitions in Multi-Level Settings – Institutional Determinants and Party Strategy’, Regional & Federal Studies, 19:1, 1–12.

- Thorlakson, Lori (2013). ‘Measuring Vertical Integration in Parties with Multi-Level Systems Data’, Party Politics, 19:5, 713–34.

- Tolksdorf, Kristin, Silke Buda, and Julia Schilling (2021). ‘Aktualisierung zur retrospektiven Phaseneinteilung der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland’, Epidemiologisches Bulletin, 2021:37, 3–4.

- Van de Wardt, Marc, Catherine E. Vries, and Sara B. Hobolt (2014). ‘Exploiting the Cracks: Wedge Issues in Multiparty Competition’, The Journal of Politics, 76:4, 986–99.

- Waldhoff, Christian (2021). ‘Der Bundesstaat in der Pandemie’, Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW), 38:2021, 2772–7.

- Weaver, Kent R. (1986). ‘The Politics of Blame Avoidance’, Journal of Public Policy, 6:4, 371–98.

- Weichlein, Siegfried (2019). Föderalismus und Demokratie in der Bundesrepublik. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Wibbels, Erik (2006). ‘Madison in Baghdad? Decentralization and Federalism in Comparative Politics’, Annual Review of Political Science, 9:1, 165–88.

- Williamson, Oliver E. (1993). ‘Opportunism and Its Critics’, Managerial and Decision Economics, 14:2, 97–107.