Abstract

Referendums were historically and theoretically justified as a people’s veto. Do voters use them as such or are referendums merely second-order votes? This article aims to answer this question through a comparative study of all constitutional referendums around the world between 1980 and 2022 using a VP-Function model. The results indicate that the support for constitutional referendums follows a pattern in which compulsory voting, economic conditions and voter mobilisation are important. Contrary to findings in more generic studies of referendums, there is no indication of a ‘honeymoon’ period for constitutional referendums. Also, in contrast to other studies, the presence of emotive words and what may appear as ‘leading questions’ favour higher support, though this is not present in countries with compulsory voting. The results contribute to the study of referendums and to the wider debate about voters’ preferences by showing that political factors are more important than structural factors.

Constitutions – political theorists maintain – must reflect an ‘overlapping consensus’ (Rawls Citation1989). As such, it is reasonable that they be submitted to a popular vote. Indeed, this is often seen as the raison d′être of referendums. In the more theoretical and jurisprudential literature on the subject the referendum has been seen as a people’s veto. What modern political scientists call a ‘veto-player’ (West and Lee Citation2014). The Victorian constitutional jurist Dicey (Citation1890: 506) spoke of the referendum as a mechanism ‘which by delaying alterations in the constitution, protect the sovereignty of the people’. Earlier works cover the conditions under which changes to constitutions ought to be submitted to referendums, the content and communication used during the campaigns, their outcomes and implementation, or the institutional conditions to win referendums on various topics including some on constitutional matters (Altman Citation2018; Silagadze and Gherghina Citation2018; Qvortrup and Trueblood Citation2022). Surprisingly little has been written about why the voters endorse (or oppose) the changes proposed in constitutional referendums. Constitutions are the rules of the game in a democratic political system. As such it is imperative that they are perceived to be fair for all actors (Ginsburg et al. Citation2009). For this reason, it stands to reason those changes to the fundamental legal document enjoys the support of the widest number of citizens, and this can best be ascertained in a referendum on the new constitution or of changes or amendments to the existing constitution.

This is a gap in the literature that we seek to remedy in this article by identifying the factors determining the outcome of constitutional referendums. The literature suggests a distinction between ‘three types of constitutional referendums: on the approval of the constitution, on its revision, and on sovereignty issues (like the foundation of a new state)’ (Morel Citation2012: 504). This study covers all three forms, but predominantly the former two because there were only several cases that fulfilled the democracy criteria outlined below.Footnote1 We do not carry out a separate analysis of tout court constitutional revisions because these are too rare to be relevant at a large scale. Our data includes all referendums pertaining to changing, amending or completely revision constitutions. We focus on constitutional referendums in democracies, which are the countries considered democracies by the Polity IV and Polity V projects, and ‘free’ by the Freedom House. We prefer these two indicators over the liberal democracy Index of V-Dem because of their broader coverage of countries around the world. Our choice of democracies is driven mainly by the idea of a free and fair setting in which people can vote on the proposed change. We identified a total of 154 nationwide votes on constitutional changes and constitutional amendments organised in 57 countries between 1980 and 2022. We exclude Switzerland from the analysis due to its extensive use of referendums (Setälä Citation1999), which would skew and bias the number of analysed cases. The starting point of our analysis is the third wave of democratisation as a middle point between the transitions to democracy in Southern Europe from mid- and late-1970s and those in Latin America and Asia-Pacific countries in the 1980s.

The article argues that the outcome of constitutional referendums can be seen as a function of other variables than the subject on the ballot paper. It develops a general model for predicting the outcomes of constitutional referendums, which looks at three categories of potential determinants. These are the characteristics of the referendum, of the initiators or of the institution in charge with the implementation in case the referendum passes (i.e. the government), and of the national political setting in which the referendum takes place. To find a possible pattern, we test several hypotheses based on previous research on referendums. These are all based on variations of the ‘lockstep’ theory (or second order paradigm), which crudely suggests that the outcomes of referendums are based on other issues than the subject at hand. For the purposes of developing a predictive model, the policies on the ballot can – perhaps paradoxically – often be overlooked. This does not mean that individual issues are always unimportant although it has been found that support for the EU was not a statistically significant factor in referendums on the EU (Qvortrup Citation2017).

There has been a change in analyses of referendums in recent years. Earlier work was characterised by an empirical approach with emphasis on case studies (Butler and Ranney Citation1978; LeDuc Citation2003). This has led to many works identifying the existence of cues how voters them to decide how to vote (Atikcan Citation2015; Suiter and Reidy Citation2015; McAllister Citation2001; Hobolt Citation2007; Bowler and Donovan Citation2002). However, this research framed in nomothetic terms was largely based on case studies (Morel Citation2012). While these are useful to understand the micro-foundations of voter choices, they do not provide prognostic power and enable us to predict the outcomes of referendums. We build on their foundations because these types of studies gradually developed testable hypotheses out of which one of the most important is that of ‘second-order’ votes (Glencross and Trechsel Citation2011). This could be considered as the ‘‘lockstep’ phenomenon in which referendum outcomes become tied to the popularity of the government in power, even if the ostensible subject of the referendum has little to do with the reasons for government popularity (or lack of popularity)’ (Franklin et al. Citation1995: 101).

We bring three contributions to the literature. At theoretical level, we propose an analytical model that breaks new ground in analysing the votes using a nomothetic approach that looks for general patterns. This can be used for the study of referendums in other policy areas beyond constitutional referendums. At methodological level, we innovate by testing the explanatory powers of the VP-function (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier Citation2013; Nannestad and Paldam Citation1994) to referendums. In election studies, the VP-function is used to explain support for the government – in the form of votes or popularity – based on its economic and political performance (Nannestad and Paldam Citation1994; Lewis-Beck and Nadeau Citation2011). We combine this with insights from the ‘second-order paradigm’ (Franklin et al. Citation1995) in the attempt to tap out the role of political institutions for referendum support. Empirically, we provide the first comparative evidence about how constitutional referendums can pass. Our findings that referendum design matters have applicability for policy makers: the initiators of constitutional changes will know how to play the game in order to win it.

The first section reviews the literature on referendum voting and identifies several variables that could influence the outcome of constitutional referendums. Next, we briefly present the data and method used for this analysis. The third section includes the main findings and their interpretation. The conclusions discuss the main implications of the results for the broader field of study.

Theory and hypotheses

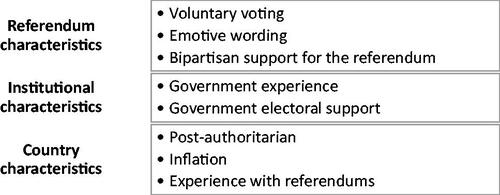

Of the 154 constitutional referendums held worldwide in democratic countries since 1980, 110 (or 71.4%) have passed. To explain the outcome of these constitutional referendums we inspire ourselves from various strands of literature since there have been few previous studies that focus on this type of referendum, with a few notable exceptions (Elkins and Hudson Citation2019; Morisi et al. Citation2021). In part, the work of Hobolt (Citation2009) is also an exception although it focuses on European referendums on constitutional issues pertaining to the EU. Our study is different as it focuses on the factors determining the outcome of these votes. In line with Elkins and Hudson (Citation2019), we regard constitutional referendums as distinct because they deal with the rules of the game. As such, we cannot rely on the more generic studies of referendums (Altman Citation2018) or on those works analysing the circumstances under which the initiators hold referendums especially when these are optional (Qvortrup Citation2014). We develop a predictive model for mostly mandatory referendums based on structural, political and economic factors, which are associated with three categories of potential explanations: the characteristics of the referendum, of the initiators or of the institution in charge with the implementation in case the referendum passes, and of the national political setting in which the referendum takes place ().

The outcome of referendums, we propose, can be organised along three types of explanations. These are taxonomical, i.e. not all exhaustive. We propose three factors to do with referendums, factors related to the initiating and implementing institution, and country factors of more general socio-economic and cultural factors. These three factors can be seen as running from the particular (referendums) to the more general (types of political and social system. We structure the hypotheses around these analytical categories, which are each discussed in the subsections below.

Referendum characteristics

At the most basic levels there are several factors that have been shown or hypothesised to influence the outcome of referendums. These include voluntary (or compulsory voting), the wording of the question (which we term emotive voting), and bipartisan support for the proposed constitutional change. To begin with voluntary voting, the outcome of referendums depends on who turns out to vote. Certain social, ethnic, and economic groups have different political outlooks, and crucially different levels of political participation. This impacts referendums as much as elections. For example, evidence from single-country case studies based on survey data from countries with compulsory voting, suggests that those who would have abstained (had they had the choice) are more inclined to vote ‘no’ in constitutional referendums (McAllister Citation2001). This finding has a long history in the literature on referendums. Writing about Australian constitutional referendums in the 1970s, Woldring (Citation1976) found evidence of small ‘c’ institutional conservatism, which was most pronounced among the least politically engaged; these were the ones who would be least motivated to vote. Based on this he suggested that mandatory voting depressed the ‘yes’ vote, and thus accounted for the failure of all but one of the eleven referendums held in that country in the 1970s. Voters who were less politically aware and engaged were more likely to fall prey to simplistic slogans (Woldring Citation1976). This observation is consistent with the finding that voters with little or no interest in politics have a bias towards the status quo (Crandall et al. Citation2009), and hence are more like to cast a ballot against a proposed constitutional change.

The second characteristic is the wording of the referendum question. We propose that the presence of certain emotive words such as ‘approve’, ‘agree’ or ‘favour’ (in the vernacular languages) increase the likelihood of an affirmative vote. There has been a long-standing debate about emotive words in referendums. Theoretically speaking, this can be associated with the theory of speech-acts, according to which statements are not merely indicative, but may act as ‘acts’ that prompt listeners to act in ways that run counter to their preferences (Soleimani and Yeganeh Citation2016). There has been some indication of a moderate relationship between the outcome of referendums and the presence of emotive words in some referendums. For example, in Quebec it was reported that 62% of the total variance in support for sovereignty could be explained by factors related to question wording’ (Yale and Durand Citation2011: 251). In the run-up to the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence or with reference to the referendums on independence in Quebec, it was suggested that the wording of the question can play a decisive role (Rocher and Lecours Citation2017; Reilly and Richey Citation2011); for a dissenting view on this, see Qvortrup (Citation2014).

Negative emotions can deter a vote in favour of a constitutional change since anxious citizens oppose risky policies (Druckman and McDermott Citation2008). Experimental analysis has added to this research suggesting that the wording of the question on the ballot can sway the voters towards the status quo option (Barber et al. Citation2017). This indicates that the wording of the referendum question may negatively influence the outcome of the referendum. However, in the present circumstances we are not interested in voters rejecting questions, but we want to know if voters’ choices can actively be swayed through the employment of positive and emotive words. Theoretically, following the linguistic theory of speech acts, such words as ‘should’ and ‘ought’ can make people acts in ways they would not otherwise have acted (Austin Citation1975).

The third characteristic is bipartisan support. Constitutional changes are different from ordinary politics in that they change the whole framework of politics. These are not questions about policy details, but about the framework within which political battles take place. For this reason, constitutional scholars have stressed that the changes or amendments must reflect a sense of an overlapping consensus that transcend party-political differences (Rawls Citation1989). According to a much-cited study, ‘bipartisan support has proven to be essential to referendum success. Single country studies have found that referendums need support from all the major parties’ (Williams and Hume Citation2010: 244; Kriesi Citation2005) This finding has also been reported in larger N-historical studies (Elkins and Hudson Citation2019) and in referendums on European integration, such as Denmark and Ireland where it is essential for the passage of referendum that they are supported by both sides of politics (Fitzgibbon Citation2017). There is evidence according to which ‘referendums proposed by a large parliamentary majority’ are likely to prevail (Silagadze and Gherghina Citation2018: 905). Hence, to capture that the proposal enjoys broad support, the contention is that these referendums are supported by system-conform parties, namely what Sartori (Citation1976: 109) called ‘relevant parties’, more specifically those with ‘coalition potential’. Based on the arguments presented in this subsection, we expect that a ‘Yes’ vote in the constitutional referendums is favoured by:

H1: Voluntary voting

H2: The use of emotive wording in the question

H3: Bipartisan (relevant political parties) support for the referendum

Institutional characteristics

For most people politics is the government. Recent research has suggested that voters use their perception of the government as a proxy when making decisions about referendums. Thus, voters use ‘’attribute substitution’, by which individuals tend to substitute complex questions, which require high cognitive effort, with a simpler and more familiar question, to which the answer is more easily accessible’ (De Angelis et al. Citation2020: 846). This can manifest itself in different ways, in response to the government’s ideology, but also to the length of time they have been in office, and in the general level of support. The tendency of the centre-left to lose referendums has often been reported in single country literature (Williams and Hume Citation2010), but has rarely been tested in comparative studies (Elkins and Hudson Citation2019).

There is a considerable literature that suggests that governments enjoy a honeymoon period when they submit referendums to the people early in the term. There is a good reason for this: ‘to govern is to antagonize’ (Key Citation1968: 30). All governments break promises, fail to deliver, and enact unpopular laws. But this has an impact on other things than their support in candidate elections. The decline in support for government over time also has implications for the support a government enjoys (or otherwise) in referendums. If voters have begun to doubt the administration’s ability to deliver promises, they may be less likely to support the proposed constitutional reforms they submit to the voters. Hence, a no vote in a referendum is often a positive function of the years in office, a fact perhaps most clearly shown in the Canadian referendum on a new Constitution in 1992, in which Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s personal disapproval rating after almost a decade in office was the determining factor (Johnston et al. Citation1996). From being a mere rule of thumb, this has been corroborated through statistical analysis. Evidence shows that ‘a plebiscite [a vote initiated by the government] or obligatory referendum has a probability of success of 70% during the first 100 days of a government in office. Once 1,600 days in office have elapsed the probability that a [top-down] referendum will succeed drops below 50%’ (Altman Citation2018: 101).

The third institutional characteristic is the electoral support for the government. There is considerable literature that suggests that referendums are not solely decided on their supposed merits, but rather that they are a function of the governments’ popularity at any given time. Referendums are thus second-order votes in which the voters take use their support or otherwise of the government of the day as a cue whether to support (or not), the proposed referendum (Franklin et al. Citation1995; Franklin Citation2002). This line of thinking has been corroborated by single country research. Thus, in Uruguay the ‘vote choice is primarily the result of (…) party loyalty’ (Altman Citation2002: 617) or in France the rejection of the European Constitutional Treaty by a majority of voters was fuelled by political discontent with the national government (Ivaldi Citation2006). Based on this reasoning, we argue that a ‘Yes’ vote in the constitutional referendums is favoured by:

H4: Limited experience in government

H5: High electoral support for the governing party/parties

Country characteristics

Politics and political behaviour are not just a result of political institutions. At least since de Tocqueville (Citation2009) wrote about the differences between the USA and Mexico despite these two countries having identical institutions and near identical constitutions in the 1830s, it has been acknowledged that political behaviour in countries with an authoritarian legacy and history differs from that of countries where citizens have learned democracy by practicing it (Barber Citation1984: 178). This legacy is also likely to have implications for the use of referendums. We know that former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe differ markedly from more long-established democracies. For example, whereas all referendums on marriage equality (same-sex) have passed in the latter, referendums on this issue had mixed results in Central and Eastern Europe (Qvortrup Citation2017). Also, the use and provisions about direct democracy are contrasting in established democracies and post-authoritarian countries: the latter adopted quickly after the regime change many provisions, but the use of direct democracy is higher in established democracies (Gherghina Citation2017). In the light of these differences, we could expect a difference in the outcome of constitutional referendums between post authoritarian and long-established democracies.

Research on elections has found that there is a statistical association between macroeconomic performance and election outcomes. Under the general headline of VP-Functions, earlier research developed models that can predict the outcome of candidate elections as a function of the macroeconomic performance during the incumbents’ terms in office (Lewis-Beck and Rice Citation1992). The same methodology has more recently been employed to understand, explain, and predict the outcome of referendums: ‘the probability that a popular initiative or referendum will succeed is nearly 90% when a country is experiencing an extreme economic contraction’ (Altman Citation2018: 101). This is mainly because there is higher support for changes in times of economic pressure or crises. Accordingly, we expect more Yes votes for the constitutional referendums when the economy goes down. For comparability reasons, we use the rate of inflation as a proxy for economic growth (Barro Citation2013).

Finally, we argue that countries with frequent referendums – and a long history thereof – may have different results from countries where voters rarely are offered the opportunity to cast ballots on policy questions. While this may not be immediately intuitive and has not been investigated before, it chimes with findings from other countries. Research on referendums in Switzerland and California suggests that voters become more enlightened and acquire a deeper knowledge of politics if they participate more frequently (Kriesi Citation2005; Matsusaka Citation2020). This observation has led some research to conclude that voters in these countries become more civic minded and tend to cast ballots in an informed way (Smith and Tolbert Citation2004; Morisi et al. Citation2021). From voters’ point of view, previous findings illustrate that experience with referendums increases support for them (Gherghina and Geissel Citation2020). Voters become more responsible – and even more mature – as they are more often called to the polls. Based on these considerations, voters in countries with frequent referendums, and hence better knowledge of policies and policy issues, may be more likely to endorse mature constitutional changes. Following all these arguments, we expect that a ‘Yes’ vote in the constitutional referendums is favoured by:

H6: Long experience with democracy in the country

H7: High inflation rate in the country

H8: Long experience with referendums

In addition to these main effects, we control for several variables that could influence the ‘Yes’ votes in referendums: government ideology, population size, turnout, year of the referendum. For example, the evidence suggests that referendums have often been lost under governments headed by the centre-left, e.g. the Norwegian EU accession referendum 1994, the Swedish referendum on the introduction of the Euro in 2003, or the Italian constitutional referendum in 2016 (Pasquino and Valbruzzi Citation2017). In Australia, the centre-left Labour has proposed 25 out of the 44 referendums on changing the Constitution and won only one (in 1946) – a failure rate of 96% (Williams and Hume Citation2010).

Data and methods

We test these hypotheses on all the national constitutional referendums initiated between 1980 and 2022 around the world. We use the entire universe of referendums initiated in this time frame instead of a sample. We consider as constitutional those referendums that aimed to amend, revise or adopt parts of or an entire constitution in a country. In those countries (e.g. New Zealand) that do not have a single written constitution but a variety of laws and long-standing conventions, we analyse the referendums linked to these laws. The constitutional referendums are diverse and range between specific policy domains (e.g. divorce, number of parliamentarians) to broad issues such as membership in international organisations or independence. The identification of patterns for the success of referendums regardless of their specific content increases the value of the paper because it means that our findings are not topic specific but rather broadly applicable to this type of referendums. All the constitutional referendums covered in our study were binding and the questions on the ballot paper were similar across countries.

The starting point of the referendum selection coincides with the beginning of the third wave of democratisation (Huntington Citation1991) and with a higher use of referendums around the world (Qvortrup Citation2018). Butler and Ranney (Citation1978: 221) made a distinction between two worlds of referendums. In the first world – which covers the countries in the study – ‘Referendums are held infrequently, usually only when the government thinks that they are likely to provide a useful ad hoc solution to a particular constitutional or political problem or to set the seal of legitimacy on a change of regime’. The second world is where the referendum is ‘the centre piece of the political system’. In the latter category they put only one country: Switzerland. With votes four times a year, and sometimes as many as 16 referendums per year, this country is sui generis, and inclusion of this polity would skew the data. Hence, Switzerland is not included in this analysis. All the referendums included in the analysis are available in the Online Appendices.

Our dependent variable is the ‘Yes’ vote in referendums. The dependent variable is coded as a dummy that distinguishes between the majority of votes (more than 50.01%) in favour of the referendum proposal coded as 1 and a minority of votes (fewer than 49.99%) coded as 0. Out of the 154 referendums, 28.6% were coded 0 and 71.4% were coded 1. There is great variation between and within countries. For example, Australia, Ireland or Liechtenstein had more referendums than the average of the other countries included in the analysis and the result was different. There are very rare instances in which a country had more than two referendums and they were all rejected or approved. We use this dummy because it reflects the success of the referendum. If the countries would not have special quorum requirements – such as participation or approval quorums – a majority of ‘Yes’ would lead to the adoption of constitutional change. In fact, the correlation between the majority of ‘Yes’ votes and the adoption of a constitutional amendment or change is 0.81. This indicates that some of the countries have special provisions in place. As a robustness check (Online Appendix 2) we ran an OLS statistical analysis with an alternative dependent variable: the share of ‘Yes’ votes cast in the referendum. The results of the OLS analysis are in line with the logistic models and the effect size of the main predictors are comparable. In some instances (e.g. electoral support for the government) the effect in the OLS model is more prominent than in the ordinal regression, while in other instances such as the inflation rate the effect is more visible in the ordinal regression analysis model.

The coding of all independent variables is presented in Online Appendix 1. The measurement of most variables is straightforward. For example, the share of ‘yes’ votes cast in the referendums, whether voting was compulsory or not, or the number of years in office of the current government. Nevertheless, the operationalisation of four variables requires some explicit details. The use of emotive words in the question was identified after translating the question into English with the help of software and double-checked by scholars in most countries under investigation. The question was coded 1 when any of the following words were included ‘agree, approve, support’ because they reflect positive emotions (Gallup Citation1941; Wright and Armstrong Citation2016). The bipartisan support is coded 1 if the main political parties – both in government and in opposition but with a previous presence in government support the referendum. The political parties that were in opposition when the referendum was organised and have never been part of the government are excluded. The ideology of the government party is a dichotomous variable coded as 0 for left-wing and 1 for right-wing parties. The ideological positioning of the party comes from the Comparative Manifesto Project or from academic sources referring to the ideology of those parties if the party was not covered by the international dataset. If the government includes more parties, we looked at the ideological orientation of the majority of parties (in terms of portfolios). The post-authoritarian countries were those with a former communist regime (e.g. Balkans, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus or Central Asia) or with former totalitarian/authoritarian regime in Latin America.

The data comes from secondary sources (e.g. The Statesman’s Yearbook, the World Bank website, government websites, Comparative Manifesto Project, official election records by the relevant authorities such as the chief electoral officer or equivalent of the countries in question). The data about the share of ‘Yes’ votes is based on official statistics from the national electoral authorities.Footnote2 Some countries were not included in international datasets, and we collected the data from websites covering regional or national developments. Whenever possible, we tried to verify data credibility by using information from multiple sources. We use binary logistic regression for analysis with robust clustered standard errors for countries to compensate for the non-independence of cases on some variables. For example, the experience with democracy of a country at moment t0 is not independent from the experience with democracy at t1.

Type of voting, economic constraints and mobilisation

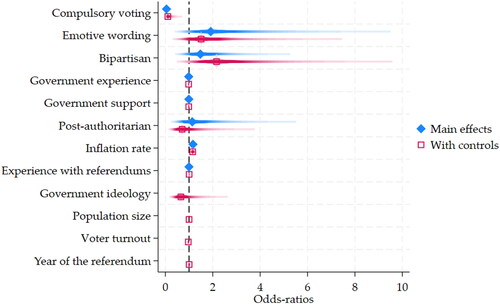

We run two regression models: one with the main effects (Model 1) and one that also includes the control variables (Model 2). The results of our regression analyses ( and Online Appendix 2) are similar in terms of coefficients strength and statistical significance. They indicate that voluntary voting, high inflation rates and lower turnout produce statistically significant effects on the likelihood of having a ‘Yes’ vote in the constitutional referendums. There is strong empirical support for H1 in the direction of our theoretical expectations: voluntary voting increases the odds for a favourable vote in constitutional referendums by 90% (Model 2) to 95% (Model 1). This confirms findings from several decades ago (Woldring Citation1976; McAllister Citation2001), which indicates that people react similarly today to how they use to do in the past when asked to vote on a policy. Constitutional referendums tend to gain support when the issues on the ballot are uncontentious, like the 1977 referendum on retirement of judges in Australia, or the Danish referendum on female succession. There are indications that compulsory voting decreases the yes-vote. In Australia, compulsory voting was introduced in 1926, and since then only five out of 29 constitutional referendums have passed. Country experts suggest that this is, in part, a result of compulsory voting. Thus, Aitkin, in a classic chapter, proposed that, ‘the dragooning of the uninterested to the polls…increased the number of those likely to vote “no”’ (Aitkin Citation1978: 132).

Figure 2. Effects on the ‘yes’ vote in referendums. Note: The full regression models are available in Online Appendix 2. The bars are 95% CIs.

There is also empirical evidence that the high inflation rates (H7) increase the ‘Yes’ vote in constitutional referendums. The results indicate a 15% (Model 2) or 17% (Model 1) increase in the odds of such a vote when the country faces economic difficulties. The evidence is consistent with, although considerably weaker than, previous findings (Altman Citation2018). During economic hardships people may be inclined to support a change in the constitution as a possible solution to alleviate the precarious conditions in the country. This happens although the topic of the referendum is often not related directly to economy. At a practical level, these findings are relevant for the referendum initiators who are in a better position to get their initiative approved once they submitted it to popular vote during periods of economic contraction.

Among the controls, voter turnout is the only variable with a statistically significant effect on the ‘Yes’ vote in constitutional referendums. The effect is small and indicates that in those referendums in which fewer people cast their vote there is an increase of 3% in the odds of a ‘Yes’ vote. This finding is consistent with the finding that compulsory voting is correlated with a higher ‘no’ vote. While it would require survey data to determine the motivations of individual voters, we can hypothesise that higher turnout brings people to the polls who are less interested in politics, and that these voters are more sceptical of change, and more susceptible to simplistic arguments, which prima facie, would make them more inclined to vote ‘no’. This would be in line with the high no-vote in contested constitutional referendums, such as those held in Norway on EU membership.

We briefly discuss two other effects with high coefficients, but with no statistical significance. The emotive wording in the referendum question (H2) increases the odds of a ‘Yes’ vote by approximately 50% (Model 2) or 90% (Model 1). This result confirms earlier findings regarding the importance of wording (Rocher and Lecours Citation2017) and that people react positively to ‘perlocutionary’ inducements (Austin Citation1975). It shows the usefulness and applicability even in more technical processes such as the one about constitution revisions. There is a strong effect of the bipartisan support (H3) on a ‘Yes’ vote – an increase higher than 100% (Model 2) and approximately 50% (Model 1) in the odds. This result confirms earlier studies (Williams and Hume Citation2010) and nuance the debate about the decreasing levels of congruence. While this trend may be true in relation to elections (Canes-Wrone Citation2015), we show that the mass-alite congruence holds with respect to constitutional referendums. I4f the justification for referendums on constitutional changes is that these should reflect an ‘overlapping consensus’ on the rules of the game (Rawls Citation1989), it is a positive outcome that votes on constitutional changes are most likely to succeed when they are supported by both sides of politics.

Among the control variables, government ideology has high effects on the voting outcome, but they are not statistically significant. Referendums organised under left-wing governments are slightly more likely to receive ‘Yes’ votes compared to right-wing governments. One possible explanation for this result is that left-wing political parties promote inclusiveness and equality, which can be valued by voters when deciding on the content of the fundamental law of their country.

We find no support for the other variables, which runs directly counter to the existing wisdom on referendum outcomes. We find no support for the second-order hypothesis, which is consistent with earlier findings about other types of referendums (Svensson Citation2002; Glencross and Trechsel Citation2011). The length in office of the government does not play a role in the voting outcome of the referendum. In essence, our results show that ideology is the only the only government-related variable that matters in such referendums. There is no difference between established and post-authoritarian countries in terms of referendum outcome, or between countries with extensive experience in referendums and those that had them for the first time.

Conclusions

This article covered the constitutional referendums organised in the last four decades and sought to explain popular support for them. This has hitherto been a relatively neglected field, despite the fact that the referendum, within constitutional theory, were seen as the quintessential veto-player (Dicey Citation1890). A classical study of constitutional jurisprudence notes that ‘the constitution [is] made hard to alter of deliberate set and purpose. It [is]s a solemn compact which recognised not merely the right of the people … it was not intended to be capable of alteration by gust of passion’ (Brennan Citation1935: 320). After many referendums, politicians and some scholars have regretted the fact that voters were prone to reject what the political class consider to be sound and necessary reforms (Landemore Citation2018). Before joining the lamentations it is worth remembering that legally as well as politically, constitutional referendums enjoy a special position as these pertain not merely to policy issues over which there may be legitimate disagreement, but rather to fundamental issues that constitute (or ought to constitute) what has been called an ‘overlapping consensus’ (Rawls Citation1989: 1).

This article contributes to the study of referendums by showing that factors pertaining to the vote itself (e.g. voluntary voting or mobilisation) and the economic conditions under which the referendum is organised play a crucial role for the outcome. The study also makes a wider contribution to our discipline. Ever since the dawn of political science in anything resembling its present-day form, there has been a divide between those who see structural factors, like the economy (Marx Citation2022), or political culture (de Tocqueville Citation2009) as the driving forces of political outcome, and, on the other hand those who reserve a role for politics as an autonomous factor (Mill Citation1958). This discussion is unlikely to be settled in a single article, but we show that thew factors co-exist in predicting the outcomes in constitutional referendums around the world. This is an important finding within the psephological studies of referendums and within the broader context of political science.

Research on referendums and initiatives in comparative perspective has shown that referendums are less likely to pass if the government has been in office for a long time. There is no indication that this is the case as regards referendums on constitutional issues. This would indicate that the referendum is not merely a proxy for the popularity (or otherwise) of the government of the day as suggested by those who espouse the ‘Second-Order’ hypothesis. Still, other factors play a role. The referendum is not a perfect bulwark against one-sided partisan change, but the findings in this article show that it can perform the function of a veto-player. This happens as long as people are not forced to express their vote and fewer voters mobilise. The latter means that the advantage of the status quo increases as more voters go to the polls. We nuance Dicey’s conclusion that the referendum ‘has the great merit of being the only check on party management which is in perfect harmony with democratic sentiment’ (Cosgrove Citation1981: 107).

We have only analysed the referendums pertaining to constitutional changes, which constitute a fraction of the total universe of cases. What overall determines the outcome of popular votes on policy issues is a question we have but begun to answer. The finding that referendum specific and country context factors are important determinants for winning them is an important start for a research area where many issues remain to be tested – let alone answered. Further research can test on a larger sample the explanatory potential of several variables with moderate or strong effects on the referendum outcome (e.g. emotive wording, bipartisan support), but which were not statistically significant for constitutional referendums.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (662.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sergiu Gherghina

Sergiu Gherghina is Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the University of Glasgow. His research interests lie in party politics, legislative and voting behaviour, democratisation, and the use of direct democracy. [[email protected]]

Matt Qvortrup

Matt Qvortrup is Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Coventry University. His research interests include referendums, European politics and comparative government. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 For a detailed study of independence referendums see Harguindéguy et al. (Citation2021).

2 For some referendums in which the choice was not between Yes and No (e.g. Brexit), we considered the ‘Yes’ vote to be when in the direction of changing the status quo (e.g. ‘leave’ was coded as 1 for Brexit).

References

- Aitkin, D. (1978). ‘Australia’, in D. Butler and A. Ranney (eds.), Referendums: A Comparative Study of Practice and Theory. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 123–37.

- Altman, David (2002). ‘Popular Initiatives in Uruguay: Confidence Votes on Government or Political Loyalties?’, Electoral Studies, 21:4, 617–30.

- Altman, David (2018). Citizenship and Contemporary Direct Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Atikcan, Ece Özlem (2015). Framing the European Union: The Power of Political Arguments in Shaping European Integration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Austin, J. L. (1975). How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barber, Benjamin (1984). Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Barber, Michael, David Gordon, Ryan Hill, and Joseph Price (2017). ‘Status Quo Bias in Ballot Wording’, Journal of Experimental Political Science, 4:2, 151–60.

- Barro, Robert (2013). ‘Inflation and Economic Growth’, Annals of Economics and Finance, 14:1, 121–44.

- Bowler, Shaun, and Todd Donovan (2002). ‘Do Voters Have a Cue? Television Advertisements as a Source of Information in Citizen-Initiated Referendum Campaigns’, European Journal of Political Research, 41:6, 777–93.

- Brennan, Thomas Cornelius (1935). Interpreting the Constitution: A Politico-Legal Essay. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Butler, David, and Austin Ranney, eds. (1978). Referendums: A Comparative Study of Practice and Theory. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Canes-Wrone, Brandice (2015). ‘From Mass Preferences to Policy’, Annual Review of Political Science, 18:1, 147–65.

- Cosgrove, Richard A. (1981). The Rule of Law: Albert Venn Dicey, Victorian Jurist. London: Macmillan.

- Crandall, Christian S., Scott Eidelman, Linda J. Skitka, and Scott G. Morgan (2009). ‘Status Quo Framing Increases Support for Torture’, Social Influence, 4:1, 1–10.

- De Angelis, Andrea, Céline Colombo, and Davide Morisi (2020). ‘Taking Cues from the Government: Heuristic versus Systematic Processing in a Constitutional Referendum’, West European Politics, 43:4, 845–68.

- Dicey, A. V. (1890). ‘Ought the Referendum to Be Introduced into England?’, Contemporary Review, 57, 489–511.

- Druckman, James N., and Rose McDermott (2008). ‘Emotion and the Framing of Risky Choice’, Political Behavior, 30:3, 297–321.

- Elkins, Zachary, and Alexander Hudson (2019). ‘The Constitutional Referendum in Historical Perspective’, in David Landau and Hanna Lerner (eds.), Comparative Constitution Making. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 142–68.

- Fitzgibbon, John (2017). ‘When “No” Means “Yes”: A Comparative Study of Referendums in Denmark and Ireland’, in Enjamin Leruth, Nicholas Startin, and Simon Usherwood (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism. London: Routledge, 280–90.

- Franklin, Mark N. (2002). ‘Learning from the Danish Case: A Comment on Palle Svensson’s Critique of the Franklin Thesis’, European Journal of Political Research, 41:6, 751–7.

- Franklin, Mark N., Cees van der Eijk, and Michael Marsh (1995). ‘Referendum Outcomes and Trust in Government: Public Support for Europe in the Wake of Maastricht’, West European Politics, 18:3, 101–17.

- Gallup, George (1941). ‘Question Wording in Public Opinion Polls’, Sociometry, 4:3, 259–68.

- Gherghina, Sergiu (2017). ‘Direct Democracy and Subjective Regime Legitimacy in Europe’, Democratization, 24:4, 613–31.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, and Brigitte Geissel (2020). ‘Support for Direct and Deliberative Models of Democracy in the UK: Understanding the Difference’, Political Research Exchange, 2:1, 1809474.

- Ginsburg, Tom, Zachary Elkins, and Justin Blount (2009). ‘Does the Process of Constitution-Making Matter?’, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 5:1, 201–23.

- Glencross, Andrew, and Alexander Trechsel (2011). ‘First or Second Order Referendums? Understanding the Votes on the EU Constitutional Treaty in Four EU Member States’, West European Politics, 34:4, 755–72.

- Harguindéguy, Jean-Baptiste, Enrique Sánchez Sánchez, and Almudena Sánchez Sánchez (2021). ‘Why Do Central States Accept Holding Independence Referendums? Analyzing the Role of State Peripheries’, Electoral Studies, 69:02248, 102248.

- Hobolt, Sara B. (2007). ‘Taking Cues on Europe? Voter Competence and Party Endorsements in Referendums on European Integration’, European Journal of Political Research, 46:2, 151–82.

- Hobolt, Sara Binzer (2009). Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huntington, Samuel P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Ivaldi, Gilles (2006). ‘Beyond France’s 2005 Referendum on the European Constitutional Treaty: Second-Order Model, Anti-Establishment Attitudes and the End of the Alternative European Utopia’, West European Politics, 29:1, 47–69.

- Johnston, Richard, André Blais, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Neil Nevitte (1996). The Challenge of Direct Democracy: The 1992 Canadian Referendum. Montreal/Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press.

- Key, V. O.Jr. (1968). The Responsible Electorate: Rationality in Presidential Voting 1936-1960. New York: Vintage Books.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2005). Direct Democratic Choice: The Swiss Experience. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- Landemore, Hélène (2018). ‘Referendums Are Never Merely Referendums: On the Need to Make Popular Vote Processes More Deliberative’, Swiss Political Science Review, 24:3, 320–7.

- LeDuc, Lawrence (2003). The Politics of Direct Democracy: Referendums in Global Perspective. Toronto: Broadview Press.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Tom W. Rice (1992). Forecasting Elections. Washington D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Richard Nadeau (2011). ‘Economic Voting Theory: Testing New Dimensions’, Electoral Studies, 30:2, 288–94.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Mary Stegmaier (2013). ‘The VP-Function Revisited: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions After Over 40 Years’, Public Choice, 157:3-4, 367–85.

- Marx, Karl (2022). Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. New York: International Publishers.

- Matsusaka, John G. (2020). Let the People Rule: How Direct Democracy Can Meet the Populist Challenge. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- McAllister, Ian (2001). ‘Elections Without Cues: The 1999 Australian Republic Referendum’, Australian Journal of Political Science, 36:2, 247–69.

- Mill, John Stuart (1958). Considerations on Representative Government. New York: Liberal Arts Press.

- Morel, Laurence (2012). ‘Referendum’, in Michel Rosenfeld and András Sajó (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 501–28.

- Morisi, Davide, Céline Colombo, and Andrea De Angelis (2021). ‘Who is Afraid of a Change? Ideological Differences in Support for the Status Quo in Direct Democracy’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31:3, 309–28.

- Nannestad, Peter, and Martin Paldam (1994). ‘The VP-Function: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions after 25 Years’, Public Choice, 79:3–4, 213–45.

- Pasquino, Gianfranco, and Marco Valbruzzi (2017). ‘Italy Says No: The 2016 Constitutional Referendum and Its Consequences’, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 22:2, 145–62.

- Qvortrup, Matt (2014). Referendums and Ethnic Conflict. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Qvortrup, Matt (2017). ‘The Rise of Referendums: Demystifying Direct Democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 28:3, 141–52.

- Qvortrup, Matt, ed. (2018). Referendums around the World: With a Foreword by Sir David Butler. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Qvortrup, Matt, and Leah Trueblood (2022). ‘Schmitt, Dicey, and the Power and Limits of Referendums in the United Kingdom’, Legal Studies, 42:3, 396–407.

- Rawls, John (1989). ‘The Domain of the Political and Overlapping Consensus’, New York University Law Review, 64:2, 233–55.

- Reilly, Shauna, and Sean Richey (2011). ‘Ballot Question Readability and Roll-Off: The Impact of Language Complexity’, Political Research Quarterly, 64:1, 59–67.

- Rocher, François, and André Lecours (2017). ‘The Correct Expression of Popular Will: Does the Wording of a Referendum Question Matter?’, in Laurence Morel and Matt Qvortrup (eds.), The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy. London: Routledge, 227–46.

- Sartori, Giovanni (1976). Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Setälä, Maija (1999). ‘Referendums in Western Europe – A Wave of Direct Democracy?’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 22:4, 327–40.

- Silagadze, Nanuli, and Sergiu Gherghina (2018). ‘When, Who and How Matter: Explaining the Success of Referendums in Europe’, Comparative European Politics, 16:5, 905–22.

- Smith, Dan, and Caroline Tolbert (2004). Educated by Initiative: The Effect of Direct Democracy on Citizens and Political Organisations in the American States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Soleimani, Hassan, and Maliheh Nouraei Yeganeh (2016). ‘An Analysis of Pragmatic Competence in 2013 Presidential Election Candidates of Iran: A Comparison of Speech Acts with the Poll Outcomes’, Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 6:4, 706–15.

- Suiter, Jane, and Theresa Reidy (2015). ‘It’s the Campaign Learning Stupid: An Examination of a Volatile Irish Referendum’, Parliamentary Affairs, 68:1, 182–202.

- Svensson, Palle (2002). ‘Five Danish Referendums on the European Community and European Union: A Critical Assessment of the Franklin Thesis’, European Journal of Political Research, 41:6, 733–50.

- de Tocqueville, Alexis (2009). De la Démocratie en Amerique. 1848th ed. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- West, Karleen Jones, and Hoon Lee (2014). ‘Veto Players Revisited: Internal and External Factors Influencing Policy Production’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 39:2, 227–60.

- Williams, George, and David Hume (2010). People Power: The History and Future of the Referendum in Australia. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- Woldring, Klaes (1976). ‘The Case for Voluntary Voting in Referendums’, Politics, 11:2, 209–11.

- Wright, Kim, and Tamsin Armstrong (2016). ‘The Construction of an Inventory of Responses to Positive Affective States’, SAGE Open, 6:1, 215824401562279.

- Yale, François, and Claire Durand (2011). ‘What Did Quebeckers Want? Impact of Question Wording, Constitutional Proposal and Context on Support for Sovereignty, 1976–2008’, American Review of Canadian Studies, 41:3, 242–58.