Abstract

Populist parties are held to be the drivers of unprecedented emotionalisation in electoral politics. Advancing theories of realignment and detachment, this article studies the temporal development in the affective alignments between voters and parties. In particular, it analyses the relationship between social structure, voters’ affective orientations towards political parties, and vote choice over time by drawing on 625 representative population surveys from Germany over 44 years. The results show that voters’ affective orientations are indeed becoming more important to vote choice. However, this reflects a return to the close link that already existed at the heyday of the original cleavages rather than something novel. What seems to have changed is the degree to which affective orientations are rooted in social structure. This not only qualifies overly myopic interpretations of populist success but has more general implications for the contemporary linkages between parties and voters.

Populist parties have impressed observers with their electoral successes in the past decade. While a number of explanations have been proposed for this development, a particularly influential one relates to the affect and emotions of citizens. Here, an appeal to the emotions of citizens (particularly negative ones) is central to the populist approach (e.g. Canovan Citation1999: 6, 15; Demertzis Citation2019; Gerstlé and Nai Citation2019; Kinnvall Citation2018; Marcus et al. Citation2019; Widmann Citation2021; Wodak Citation2015) and partly explains its persuasiveness (Hameleers et al. Citation2017; Magni Citation2017; Rico et al. Citation2017; Wirz Citation2018; cf. also Aarøe Citation2011; Schumacher et al. Citation2022).Footnote1 This narrative implies that, overall, emotions have become more central to party competition and voting behaviour than in the past. Populist innovations in terms of emotional appeals led to a new kind of politics, a shift away from the more ‘rational’ politics of preference aggregation and translation that the established mainstream parties engaged in after World War II (Flinders and Hinterleitner Citation2022).

Studying changes in the affective alignments between parties and voters through time, i.e. changes in the extent to which voting behaviour is infused with immediate feelings of attachment and aversion, we qualify this interpretation: The view that populists have made political discourse uniquely more emotional – and that voters have adapted accordingly by privileging affect as a yardstick to evaluate politics – is somewhat myopic. It ignores the fact that parties engaged profoundly with citizens’ emotions in the past as well. That is, the period at the turn of the century might be the exception rather than the rule. What did change is the underpinning of affect and emotions in electoral politics: Once, these elements were firmly rooted in social structure and their effects on voting behaviour were thus epiphenomenal. Nowadays, affect in politics channels voters’ decisions but the patterns of affect themselves seem no longer so clearly aligned with socio-structural factors.

To make this argument, we develop theories of realignment and detachment (see Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015) further, spelling out their implications for the development of affective alignments between parties and voters. Empirically, we substantiate our argument by modelling, and comparing through time, (1) how social structure impacts voters’ affective orientations towards parties and (2) how these affective orientations in turn impact voting behaviour. We use a cumulation of 625 representative population surveys from Germany with a total number of over 375,000 respondents over 44 years (1977–2020) to do so.

Our account cautions against adopting an overly synchronic perspective in interpreting electoral results. What seems clear-cut up-close might become more complex if we take a step back and broaden the historical scope. In the case at hand, prolonging the time horizon makes one realise how the rather recent rise of emotional rhetoric in politics, as described in current punditry and scholarship, tells us at least as much about the old mainstream parties as it does about the new populist challengers; the former in fact had invested more in shoring up citizens’ emotions once before. The question then becomes why they stopped and what a more emotional answer to populism could look like. More generally, taking a broader historical perspective reminds us that electoral behaviour is shaped by the political context: Which ‘variables’ drive electoral behaviour – and to what extent – depends on social structure and institutions (Dassonneville Citation2023; Garzia et al. Citation2022; Franklin Citation1992; Thomassen Citation2005; Knutsen Citation2017) as well as the currently dominant patterns of party-voter interactions.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next section describes what we mean by affective alignment, connects it to the cleavage concept, and develops expectations with respect to its over-time development from realignment and detachment theory. The third section introduces the data set we use, operationalises the central concepts, and lays out our analytical strategies for assessing the relationship between social structure, affective orientations, and vote choice. Following the presentation of the findings and several robustness checks, the concluding section sets out the implications of our key findings for the broader discussion on emotions and affect in party-voter linkage. Also, we offer suggestions on how to extend this line of research.

Affective orientations, social structure, and the vote

By affective alignment, we mean an allegiance of voters to parties that is infused with feelings of attachment and aversion. It denotes a situation in which it is instinctively and assertively clear to citizens where they belong politically. Their choice at the ballot box is ‘easy’ in that it can be made without much explicit consideration to ideology or specific policies. The concept combines two aspects: (1) the affective orientations a citizen has towards political parties and (2) the intersection of these intuitions with citizens’ eventual choice at the ballot box.

By affective orientations, we mean a citizen’s instinctive, unmediated, and embodied summary evaluations of the different political parties (cf. Lodge and Taber Citation2013: 219; Bakker et al. Citation2021: 150–51). A citizen can have easily accessible strong positive feelings towards their political camp and the party/parties that represent it, strong negative feelings with respect to rival camps and the party/parties that represent it, or be indifferent to them (Iyengar et al. Citation2012; Wagner Citation2021; cf. Gidron et al. Citation2023). What we call affective orientations thereby captures on the individual level what the literature on affective polarisation studies on the societal level.

The concept is theoretically related to the concept of party identification (Campbell et al. Citation1960). That is, we expect voters to identify with a party towards which they have a strong positive affective orientation. But because citizens may have a (positive or negative) affective orientation towards multiple parties, our concept is better able to capture the place of an individual in the conflicts on which the party system as a whole is based. Particularly in multi-party systems, citizens regularly have positive relationships with multiple parties (Garry Citation2007) at the same time as negative relationships are highly consequential (e.g. Bankert Citation2021).

An affective alignment is then realised from affective orientations, when these patterns of attachment and aversion between a citizen and the parties in the system translate into, or at least overlap with, their voting behaviour. Our basic theoretical premise is that whether citizens develop pronounced affective orientations towards the parties and whether these orientations channel voting depends on the nature of party-voter interactions (cf. Sartori Citation1969: 209–11).

Affective alignment under the original socio-structural cleavages

Our notion of affective alignment is compatible with conceptions of the original socio-structural cleavages. According to Bartolini and Mair (Citation2007: 199), a cleavage requires (a) social-structural divisions, (b) collective identities, and (c) organisational expressions. It is this second component, the collective identity of those who share the defining socio-structural characteristic, that is evocative of affective attachments and aversions to groups and parties in society (cf. Bornschier et al. Citation2021: 2091–2): According to intergroup emotion theory, the events and objects that concern a group ‘are appraised for their emotional relevance, just like events that occur in an individual’s personal life’ (Smith et al. Citation2007: 431) by those who identify with the group. The experience of group-related emotions in turn strengthens collective identification (Kessler and Hollbach Citation2005).

Indeed, partisan rhetoric in the heyday of the original socio-structural cleavages in Western Europe (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967) relied heavily on emotional appeals to profit from and shore up collective identity. At the time, parties ‘created “political subcultures” precisely to enforce and reinforce the political and affective linkage with the party and, in difficult contexts, to set up a secure and protective environment’ (Ignazi Citation2021: 106). In the electoral arena, this meant engaging in efforts to mobilise the social segment they represented (e.g. owners/Catholics) and demobilising the opposing social segment (e.g. workers/seculars) (Katz and Mair Citation1995: 7; Sani and Sartori Citation1983: 331). Doing so entailed positively re-enforcing the group identity of their classe gardée as well as vitriolically demonising opposing social segments, their concerns, and representatives (e.g. Hölzl Citation1974). With their party making the connections, citizens transmitted the negative affective orientations they held about the opposing social segment onto that segment’s issues, candidates, and party (cf. Ladd and Lenz Citation2008: 267–77).

While the classic cleavages thus sustained an affective alignment between voters and parties, profound economic and social changes related to post-industrialization complicated the picture. Diversifying life experiences and social networks led to the disintegration of the socio-structural alignments (Dalton et al. Citation1984; Mackie and Franklin Citation1992; Katz Citation2013: 54–6): The service sector expanded tremendously at the expense of industry. Citizens had more educational opportunities und information available to them than in the past. Urbanisation proceeded, as did social mobility as a function of the welfare state. As a result, the act of voting became less determined by class and religion (Franklin Citation1992; Thomassen Citation2005), reflecting both that there are fewer industrial workers and devout religious citizens in society and that those who remain are less loyal to their party than in the past (Debus and Müller Citation2019).

Two interpretations of the relevance of economic and social change for affective orientations

How exactly these economic and social changes impact electoral politics is at the heart of the debate between proponents of realignment theory and detachment theory (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015): Proponents of realignment see the original socio-structural cleavages as increasingly supplanted by new ones (e.g. Bornschier et al. Citation2021; Häusermann and Kriesi Citation2015; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018); a diminution in the capacity of social structure to sustain electoral alliances is, then, only temporary. Proponents of detachment, in contrast, argue that social structure has become so fluid and porous that it has lost the capacity to underlie any kind of well-defined and lasting electoral coalition (Franklin Citation1992; Enyedi Citation2005; Katz and Mair Citation2018).Footnote2 These two theoretical lenses suggest divergent expectations with respect to the relationship between social structure and affective orientations:

Realignment theory implies that socio-structural factors retain their structuring power over voters’ affective orientations. The basic proposition here is that the disintegration of the traditional cleavages ‘result[s] in the reorganisation of party competition around new structural cleavages, as new divides open up in society and are mobilised and organised either by new parties or by major realignments in the support of the existing parties’ (Ford and Jennings Citation2020: 298). In particular, scholars have identified a novel cultural divide between those in society who adopt a universalistic principle of equality and those with a more particularistic value orientation towards tradition, nationalism, and community (Bornschier Citation2010). The divide pertains to the mobilisation of issues such as gender equality and environmental protection by New Left parties (i.e. the Greens and changing social democratic parties)Footnote3 and the subsequent countermobilization of the populist right (Bornschier et al. Citation2021: 2093; Kitschelt Citation1994; Ignazi Citation1992; Inglehart Citation1984; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019). In addition to opposing the issues advanced by the New Left, the populist right developed its own issue priorities and narratives, mainly with respect to immigration (Bornschier Citation2010: 422). This new divide is also decidedly transnational because it can be seen as a product of globalisation, because recent international crises have further deepened it, and because a central issue of the divide concerns European integration (de Vries Citation2018; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018).

Crucially – and here the cleavage concept comes in – research has identified social structure as impacting where a citizen falls on the universalism-particularism continuum, most significantly with respect to education (Enyedi Citation2008: 292; Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015; Kriesi Citation1999, Citation2010; Stubager Citation2009). To develop the same anchoring power as the traditional cleavages, the new socio-structurally infused cultural divide requires comparable levels of collective identification among the opposing camps, however (Bornschier et al. Citation2021; Stubager Citation2009; Zollinger Citation2024).

From the realignment perspective, parties are thus expected to build and reify socio-structural identifications in much the same way as they did in the past, by shoring up the passions of their camp. Voters on each side of the socio-structural cleavage will develop positive orientations towards the parties representing their side and negative orientations towards the representatives of the other side. The expectation of the relationship between social structure and affective orientations engendered by realignment theory is thus:

H1a: The overall effect of social structure on voters’ affective orientations towards political parties is stable over time.

The detachment perspective does not mean to refute that there are still electorally important socio-structural divisions. Rather, it argues that the novel fault lines cannot gain the same amount of pervasiveness, consistency, and closure as the old cleavages did. Partly, this is due to the sheer amount of fragmentation that socio-economic changes have fostered in society, partly it relates to the decline in socialisation and peer pressure (Enyedi Citation2008: 289). Given the contemporary nature of interpersonal and political communication, closure in homogenous social groups nowadays needs to be actively ‘chosen’ by individuals (cf. Kriesi Citation2010: 678–9, 683).

Instead of merely activating pre-defined and self-conscious social segments, the detachment perspective ascribes political parties even more agency. They assemble electoral coalitions ad-hoc in a relatively unrestricted manner (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015: 183–4). Enyedi (Citation2005) has described the process as follows:

parties face institutional and social constraints and adjust their appeal accordingly, but they also invent, facilitate and destroy political identities, underplay social divisions and shift group boundaries. The clusters of pre-political life-experiences and dispositions present both opportunities and constraints for politicians. They can mobilize these structural and attitudinal differences, but they can also identify symbols that unite various groups by tapping what is common in them. The potential room for maneuver is considerable since individual interests and values can be combined with other values/interests in a large number of ways. (Enyedi Citation2005: 700)

H1b: The overall effect of social structure on voters’ affective orientations towards political parties decreases over time.

A curvilinear relationship between affective orientations and vote choice over time

While theories of realignment and detachment differ in the predictions they have towards the over-time effect of socio-structural variables on affective orientations, they make a similar prediction regarding the relationship between affective orientations and vote choice. Both theories envision a curvilinear development, albeit for different reasons and with different timing:

H2: The effect of voters’ affective orientations on vote choice is curvilinear over time.

Detachment theory reaches the above hypothesis (H2) by describing a succession of (1) affective alignment as part of the original structural cleavages, (2) no affective alignment under catch-all and cartel politics, and (3) renewed affective alignment based on the competition between ‘rational’ mainstream parties and ‘emotional’ populist challengers.

As a reaction to post-industrialization, parties are seen here as shedding their ‘ideological baggage’ (Kirchheimer Citation1966: 190). Instead, they emphasise the provision of ever more public goods to ever more voters (Blyth and Katz Citation2005: 38; Sani and Sartori Citation1983: 331) and assemble more complex and symbolic electoral coalitions than in the past (as described above). As policy differences between the parties shrink, there is less reason to fight about policy at all (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015: 184; cf. Katz and Mair Citation1995, Citation2009, Citation2018). Instead of offering divergent policy positions, sustained by the interests of clearly demarcated socio-structural segments, party competition comes to revolve around valence – not in the sense of exhibiting a differential level of commitment (cf. Rabinowitz and Macdonald Citation1989), but in the sense of who is most competent in carrying out the agreed-upon policies (cf. Katz and Mair Citation2009: 755).

With respect to parties’ approach to voters’ emotions, the demonisation of large parts of society becomes implausible, when parties increasingly want to ‘catch all’ (cf. Katz Citation2013: 55–6). Similarly, when parties want voters to judge them on their management capabilities, their rhetoric is toned down emotionally, emphasising responsibility and capability. When party communications contain narrower and weaker emotional appeals, eschewing, for instance, appeals to fear and anger while preferring instead rational argumentation that covers the costs and benefits of certain policies or the competencies of its leader, voters are liable to rely more on said considerations rather than their affective propensities, when comparing voting alternatives.

New challengers, commonly referred to as populists, stepped in to fill the ‘emotional deficit’ (cf. Richards Citation2004) left by the established mainstream parties. Their rhetoric is made affectively more accessible by three components. First, populists bring in issues and policy positions that have been kept outside of the political debate (cf. Blyth and Katz Citation2005), in an attempt to upset the current divides on which party support is based (cf. Schattschneider Citation1975). Their broader repertoire of issues allows challengers to build vigorous emotional appeals that contrast starkly to the ‘technical’ and ‘responsible’ offers by the established mainstream. Second, in so doing, populists combine issue commitments that seemed incompatible from the perspective of established parties with ideological histories (consider, for instance, welfare chauvinism; Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2018). Third, populists garnish the policies they advance with heavy invocations of the populist worldview, thereby attracting voters who might not share their substantial positions but agree with their critique of elites (Loew and Faas Citation2019).

Comparable to the heyday of the classic cleavages, populists thus offer more affect-loaden depictions of the political landscape, appealing intensely to a variety of arousing emotions. When voters take up these cues, it makes them rely more on their affectively ingrained evaluations of parties in the voting booth rather than more cognitively-mediated factors. In contrast to realignment theory, detachment theory predicts an increasing overlap between affective orientations and vote choice with the emergence of populist challengers (of either the left- or right-wing persuasion) rather than the advent of the New Left.

Data and methods

In order to evaluate these hypotheses, we study the relationship between social structure, citizens’ affective orientation, and vote choice in Germany over time. This case is useful for three reasons: First, in terms of the narrative with which we started – that populists have recently made politics uniquely more emotional – Germany is typical.Footnote4 Second, Germany makes a hard case for our theory. Previous research has not found as much dealignment from the classic cleavages there as in other countries (cf. Debus Citation2010). Already Franklin (Citation1992) described Germany as a ‘late-comer’. In that sense, we expect our results to have larger implications in those polities which experienced a more robust and earlier breakdown of the traditional cleavages. The third advantage concerns data availability. Indicators documenting the affective experiences of citizens with respect to politics are scarce – at least historically (Gidron et al. Citation2022: 11). This reflects the orientation towards cognition and rational choice approaches in the study of human behaviour. In Germany, we are able to draw on a collection of monthly surveys which contain an appropriate measure and reach back to 1977.

We begin by justifying this measure and presenting its data source, and then detail how we use it first as a dependent variable – when analysing the effect of socio-demographics on affective orientations over time (H1a and H1b) – and then as an independent variable – when analysing the effect of affective orientations on vote choice (H2) over time.

Measuring affective orientations across time

We utilise thermometer ratings of political parties, which capture the affective orientations citizens hold towards political parties (Lodge and Taber Citation2013: 224; cf. Barrett Citation2006: 224; Marcus Citation1988: 738). According to Lodge and Taber (Citation2013), the feeling thermometer represents a running tally, ‘a rough summing up of one’s assessments of the positive and negative consequences of past experiences [with the party]’ (219). It is a summary evaluation that is ‘felt’ rather than justified, an overall orientation towards the party that is more immediately accessible than the specific likes and dislikes that generated this evaluation in the first place (Lodge and Taber Citation2013).

There are two potential concerns with respect to using the thermometer ratings: First, one might object that they essentially measure a respondent’s ideological proximity to the parties, or at least are highly endogenous to them (cf. Ladd and Lenz Citation2008: 277). However, there are good reasons to believe that the feeling thermometers capture much more. Our cue is the recent scholarship on affective polarisation. Here, the concept of interest is ‘the extent to which a voter has an ‘us-versus-them’ perception of the party system’ (Wagner Citation2021: 2), as expressed in positive feelings towards one’s own party and negative feelings towards opposing parties (Iyengar et al. Citation2012: 406). Routinely using party thermometer ratings to measure affective polarisation (for instance, their spread; Wagner Citation2021), researchers have shown that these scores neither simply reduce to the ideological proximity of respondents to the party (Iyengar et al. Citation2012; Dias and Lelkes Citation2022) nor perfectly mirror the perceived ideological divergence of the parties (‘ elites) (Gidron et al. Citation2020; cf. also Ward and Tavits Citation2019). What is more, even in multi-party settings, feeling thermometers correlate with partisan trait-ascriptions, preferred social distance as well as discrimination in dictatorship games, which ‘speaks to the affective substance captured’ (Gidron et al. Citation2022: 8) by them.

Thermometer scores might be imprinted by ideological considerations (cf. Ladd and Lenz Citation2008: 277) but our theoretical logic suggests that this would be the case especially if parties compete heavily along ideological lines (cf. Thomassen Citation2005). In a robustness check below, we show that including measures of ideological positions does not alter our conclusions.

Second, one might contend that the thermometer questions are not exogenous to vote choice. Equivalent as for party identification (cf. Budge et al. Citation1976), one might argue that thermometer questions and the vote choice indicator really measure the same underlying concept, i.e. party support. We cannot completely rule out this possibility. Previous research in political psychology supports our contention to treat them as sufficiently conceptually distinct, however: In a multivariate path model using NES data, Lodge and Taber (Citation2013: 220–3) show that affective orientations stand at the beginning of a ‘causal cascade’ (223): They impact vote choice directly as well as indirectly (by triggering specific cognitions and initiating fine-grained emotional reactions to momentary political stimuli that themselves impact voting).

As far as we find support for H2, this further speaks against feeling thermometers and vote choice merely measuring the same underlying concept. In the latter case, we would expect a one-on-one relationship with short-term random fluctuations. Instead, a curvilinear relationship that matches the patterns of party-voter interactions described in realignment and detachment theory (H2) speaks for the view that thermometer scores and vote choice are linked in a meaningful but time-dependent manner. We further include a robustness check below that estimates the direct effect of social structure on vote choice. It indicates that models omitting affective orientations are less well specified.

As a data source for our analysis, we use the Politbarometer surveys (Wüst Citation2003). These nationally representative high-quality polls have been carried out since 1977 by the Forschungsgruppe Wahlen on behalf of Second German Television (ZDF) and contain the thermometer ratings consistently. The data also contain the standard measure of voting intention in Germany, as well as a number of socio-demographic indicators relating to the cleavages at the heart of our theoretical account. Specifically, we use the partial cumulation of the Politbarometer polls as provided by GESIS (ZA2391) (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen Citation2022). This long-term cross-section accumulation consists of harmonised variables, allowing cross-time comparisons between models estimated with data from different points in time.

In total, this dataset enables us to study socio-demographic groups, affective orientations, and vote choice diachronically, and in a particularly fine-grained manner. Our analyses are based on 625 surveys with a total number of over 375,000 respondents over 44 years (1977–2020). The number of surveys per year and the sample sizes vary over time.Footnote5 Naturally, the mode of data collection changed too throughout the years. However, we would not expect these differences to affect the relevant measures.

Analysing the relationship between socio-demographics and affective orientations

To analyse the relationship between socio-demographically-defined groups and affective orientations, we estimate ordinary least squares regressions with the feeling thermometer scores of each of the major German parties as the dependent variable.Footnote6 The item asks respondents what ‘they make of’ the respective parties on a scale ranging from −5 (‘nothing at all’) to +5 (‘very much’). Key socio-demographic variables related to the classic cleavages and the universalism-particularism divide make up the set of independent variables in these analyses. We pool the monthly Politbarometer surveys annually and estimate year-specific coefficients.

We then compare the explained variance of all socio-demographic variables over time to evaluate H1a against H1b. Comparing the yearly adjusted R2 in this way is particularly useful because it can capture the overall change in both constitutive parts of cleavage alignments: It reflects that the share of those in the population belonging to a social group can vary (the variance of the independent variables can change) and that the loyalty of a social group to its party can also vary (the size of the coefficient relative to the error variance can change). Zooming in, in a second step, on the size of the regression coefficients of individual socio-demographics across time allows us to see the developments for cleavage-specific party-group pairs in detail. The full results for the yearly regression models are shown in Table A2 in the Online Appendix.Footnote7 Analogous procedures regarding the diachronic analysis of explained variance and coefficient sizes are employed in Franklin (Citation1992), Thomassen (Citation2005), Knutsen (Citation2017), Garzia, Ferreira da Silva, and de Angelis (Citation2022), and Dassonneville (Citation2023).

In order to identify those voters who traditionally sustained the Social Democrats and Christian Democrats, given the concurrence of the worker-owner and church-state cleavages, we draw on union membership and church service attendance, respectively. The former is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether the respondent or someone in the respondent’s household is a member of a labour union. The latter is a dichotomous variable that indicates whether the respondent attends church service ‘every Sunday/week’ or ‘almost every Sunday/week’. These are the standard variables utilised in the analysis of the German case (e.g. Debus Citation2007). We add to this a dichotomous variable that indicates whether the respondent is self-employed or not to identify the socio-economic base of the liberal FDP (Debus Citation2007: 278). Self-employment has been taken as relating to the worker-owner cleavage in the German case (Pappi and Shikano Citation2002: 457).

Going beyond the ‘original’ cleavages of the German party system, the Greens and the AfD have socio-demographically defined bases of their own according to the scholarship on the novel universalism-particularism cleavage. We create a variable that captures whether the respondent is highly educated (has a university degree). This is the central variable (cf. Bornschier et al. Citation2021: 2099) that should identify those most likely to hold postmaterialist values (Inglehart Citation1984) and to benefit from globalisation. Those with a university degree should thus tend towards universalism and positive affect towards the associated party (here, the Greens) and those without it towards particularism and positive affect towards the respective associated party (here, the AfD).

Unfortunately, the data do not allow us to test the effect of occupational classes (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018) or disaggregate education into cultural, economic, communicative and technical resources (Hooghe and Marks Citation2022).Footnote8 This limits our analysis in the sense that these distinctions have been successfully used to flesh out the social bases of the universalism-particularism division. While higher education is central, it remains somewhat crude and this should be considered as we adjudicate between H1a versus H1b.

Two final socio-demographic variables seek to identify those respondents particularly disadvantaged by economic and social transformations. These are not straightforwardly related to the traditional cleavages or the new universalism-particularism cleavage, but they can be seen as equivalently providing a social base in the German party system. The first variable indicates East German respondents. The second indicates whether the respondent is unemployed. Both should capture the social base of the left-wing populist PDS/Left (Weßels Citation2019: 199–200). Similarly, scholars of the German case have asked whether there is an overlap with the right-wing populist AfD here (Weßels Citation2019: 202; cf. Wagner et al. Citation2023).

Analysing the relationship between affective orientations and vote choice

When analysing vote choice, we estimate conditional logit models drawing on the classic German indicator asking which party a respondent would vote for if elections were held next Sunday. Vote choice is seen here as a discrete choice among a given set of voting options. The model treats the used data in a stacked manner (looking at dyads: respondent – party they may potentially vote for) and draws on the simultaneous comparison of the effect of the independent variables towards each available alternative (here, parties) on their perceived utility.

The choice set includes the CDU/CSU, the SPD, the FDP, the Greens (since 1980), the PDS/Left (since 1994), and the AfD (since 2014). Those respondents who report not intending to vote and those who favour fringe parties are thus excluded from this analysis. The model includes the thermometer ratings regarding said parties as our measure of affective orientation and central independent variable of interest, as well as all the socio-demographic variables described above. The latter ascertain that we do not mistakenly ascribe effects to affective orientation that directly stem from social divisions instead.

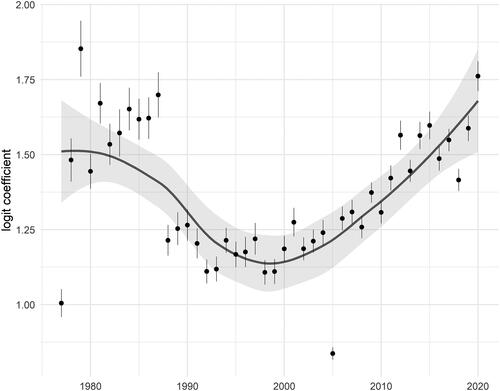

Equivalent to above, we compare the coefficient size of affective orientation across years (e.g. Garzia et al. Citation2022) and expect a curvilinear relationship (H2). With regards to the timing, the realignment perspective expects to see the uptick in the relationship as the Greens firmly establish themselves in the party system (1980s). Detachment, in turn, expects the uptick with the establishment of populist parties. In the German case, that would be the left-wing populist Die Linke in the mid-2000s and then the right-wing populist AfD in the 2010s (Rooduijn et al. Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

Analyses

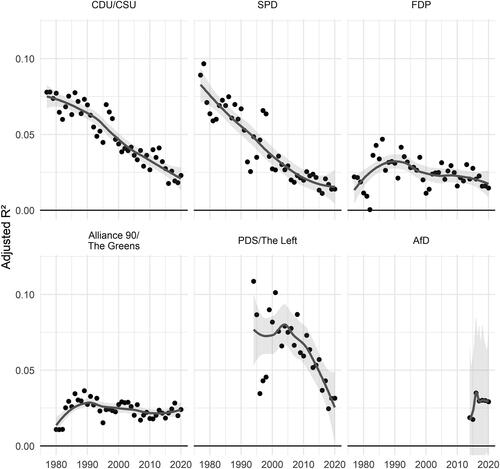

We begin by comparing the adjusted R2 of the linear regression models explaining affective orientations for each of the parties across time (). This summary measure indicates how much the whole set of socio-demographic variables under consideration help to explain differences in affective orientations: We see that the joint explanatory power of union membership, church service attendance, being self-employed, being highly educated, being East German, and being unemployed decreases markedly over time where these variables explained the most to begin with, i.e. for the Christian Democrats, the Social Democrats, and the PDS/Left. For the FDP there was a brief upward trend at the beginning of our time series, but then a significant decrease ensued as well. For the Greens and the newcomer AfD, the amount of variance explained by socio-demographic variables stays relatively constant at low levels. Nowadays, affective orientations towards political parties seem less based on social structure than they used to be. While socio-demographic variables accounted for up to 10% of the variation in party affect for Christian and Social Democrats in the 1980s (and, at their peak, up to 5% for the smaller parties), the variance explained by socio-demographic factors is nowadays closer to 2.5% and often even lower for all parties.

This decrease in overall explanatory power is especially noteworthy in two respects. First because of the conservative nature of our test: Processes of dealignment from the original cleavages were already underway by 1977. If our argument is correct, the link between socio demographics and affective orientation, on the one hand, and affective orientation and vote choice, on the other, should have been even stronger in the 1950s and 1960s compared to the late 1970s when the data begins but the old cleavages already start to disintegrate.

Second, our analysis not only includes socio-structural variables relating to the classic cleavages but also the central variable relating to the universalism-particularism cleavage. The evidence does not seem to suggest that the more recent social divisions can completely compensate for the old cleavages in the degree to which they structure electoral politics, at least with respect to affective orientations: Affective orientations towards Greens and AfD remain less well-structured by social divisions at any point than those towards CDU/CSU and SPD in the past. We certainly must keep in mind that realignment might not yet be complete – i.e. that the explanatory power of the related socio-structural variables might not have reached its full potential yet – and that we were not in a position to include all distinctions relevant to the new cleavage – e.g. horizontal class. But the pattern we identify in the data at hand looks somewhat more in line with the detachment (H1b), rather than the realignment (H1a) perspective.

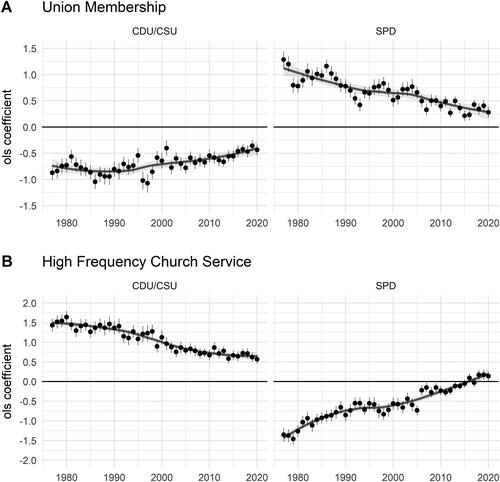

We next zoom in on changes in the effect sizes of specific socio-structural variables and the parties they are theoretically associated with. As can be seen in , both union membership and church service attendance were once highly predictive for affect towards the Social and Christian Democratic parties. But this is no longer the case. Living in a union household used to decrease the level of positive feeling for the Christian Democrats, while increasing the level of positive feelings towards the Social Democrats (Panel A). The pattern for church service attendance is exactly the reverse (Panel B). However, the coefficients constantly approach zero as we move forward in time, indicating an increasing decoupling of the variables related to the classic cleavages and affective orientation towards these parties.

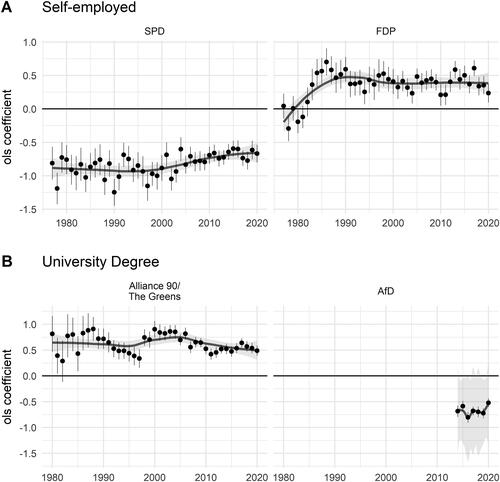

The decoupling of social division and affective orientation is not as pronounced for the liberals. Being self-employed increases positive feeling for the FDP (Panel A in ). The coefficient size decreases only marginally. The FDP’s opponent in this division is the social democratic SPD. Being self-employed decreases the amount of positive feeling towards the latter. Also here, we see a small uptick in the trend through time. For the Greens and their social group, there is no pattern of decoupling (Panel B in ). Being highly educated is predictive of having positive feeling towards the Greens. There is a decrease here as well, but it is comparatively marginal. In turn, the highly educated have fewer positive feelings towards the AfD.

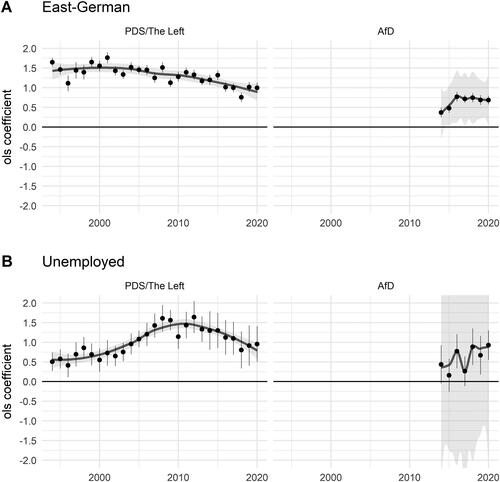

Turning to the final cluster of variables, affective orientations are more positive towards the PDS/Left and the AfD among East Germans compared to West Germans (Panel A in ). The coefficient for the PDS/Left continuously decreases through time, however. Similarly, unemployment increases as a predictor of affect as the PDS reorganises in the wake of the Social Democrat’s third-way policies and decreases thereafter (Panel B in ). Being unemployed also increases positive feelings towards the AfD, but the coefficient wavers and the confidence interval crosses zero in three years.

We now turn to the second analysis, the comparison of the conditional logit coefficients that describe the effect of affective orientations in the models explaining vote choice. The coefficients are plotted by year in . Clearly, having more positive feelings for a party increases the likelihood of voting for that party. While always positive and statistically distinguishable from zero, the effect of affective orientations on vote choice has been increasing in recent years. This is in line with the narrative that populist parties have made politics more emotional.Footnote9

However, the analysis also shows that the effect of affective orientations fluctuates over time and that, in particular, the effect today is only marginally higher than in the period between 1977 and 1987. This is in line with H2. As it turns out, the peculiar period is indeed the time between 1988 and 2005. This is the period covering German reunification as well as the Social Democrats’ ‘third way’ phase. After 2005, the effect of affective orientations on vote choice is then increasing again. This is direct evidence against the notion that we entered an ‘age of emotion’ only recently. Emotions and affect have been extremely important to voting in the past, but in a different way from today. The analysis speaks somewhat more in favour of the detachment perspective on the curvilinear relationship given that the uptick coincides with the remodelling of the PDS into a left-wing populist party and really gains steam with the AfD.

Robustness checks

In order to ascertain the validity of our interpretations, we conduct four additional tests. First, we rerun the models that explain affective orientations with social structure using alternative measures of education in order to identify the social basis of the new cleavage. The first alternative adds an indicator for intermediate levels of education (highest degree Realschule). The second alternative substitutes having a university degree for having Abitur (i.e. highest degree is from secondary education in the academic-oriented track of the German school system). The third alternative adds an indicator for those who completed vocational training (Ausbildung) (available in a consistent item format from 1994 but with a filter change in 2013). The results reported in Figures A6 and A7 in the Online Appendix do not alter our assessment with respect to the relative superiority of H1b over H1a.

Second, we rerun the analysis of vote choice, this time allowing for alternative-specific effect coefficients of affective orientations. By doing so, we allow for party-specific effects of affective orientations on the vote. This, however, does not alter the results (Figure A4, Panel B in the Online Appendix). That is, the pattern looks very similar for all parties: Dynamics in the weight of affective orientations for voting decisions are not driven by any single party.Footnote10 This corroborates our intuition that changes in the determinants of voter behaviour mirror systemic changes in how parties in general interact with voters.

Third, we want to take into account the concern that the feeling thermometers capture predominantly the ideological positions of voters. Some of the Politbarometer surveys also contain the respondents’ self-placement on the left-right scale (consistently measured only since 1991). In line with theories of voting that privilege programmatic utility maximisation on behalf of voters (cf. Downs Citation1957), as well as conceptualizations of emotions as endogenous to the cost-benefit calculations involved (e.g. Ladd and Lenz Citation2008: 277), we include this variable in a further robustness check. Doing so (Online Appendix Figures A11–A18) does not alter our results substantively.

Fourth, we investigate the direct effects of socio-demographic variables on vote choice. These turn out to be much more ambiguous than their effects on affect. They also less clearly show dealignment, regardless of whether or not the thermometer ratings are included in the analysis or not (Online Appendix Figure A8–A10). This further builds our confidence in the conceptual distinction of affective orientation and vote choice: Socio-demographic variables historically had a pronounced indirect effect on vote choice via affective orientations next to a smaller direct effect as well. Processes of dealignment from the respective social divisions are evident first and foremost with respect to baseline affective orientations. This nicely lines up with the limited evidence for dealignment in the German case in models that only look at vote choice and do not specify affective orientations (e.g. Debus Citation2010).

Conclusion

Our application of realignment and detachment theory on German polling data over 44 years shows that how people intuitively feel about political parties – a central dimension of emotional experiences in politics more generally (Lodge and Taber Citation2013: 220–223) – is an important determinant of voting behaviour. Of late, the relationship between citizens’ affective orientations towards parties and vote choice has even strengthened. However, populism has not unleashed an unprecedented storm of emotions in the voters: Affect towards parties was similarly crucial in underpinning voting decisions before the 1990s. Back then, affective orientations were significantly rooted in social group memberships. This seems to be less and less the case today.

We show that linkages between voters and parties are at least partly of an emotional nature – and they have been since before the emergence of populist parties. What changed is, first and foremost, where these linkages come from. According to our analysis, voters’ affective orientations and the attendant discrete emotions in the political realm are nowadays less patterned by social structure. Future research should ascertain that this result is not an artefact of the limited capability of our data to tap into the social base of the universalism-particularism cleavage or the incomplete consolidation of the latter. Relatedly, while our theory would expect similar, or indeed even more pronounced, patterns, as we observed for Germany, studying other post-industrial democracies will help clarify how the exact timing depends on shifts in party-voter interactions.

More research is also needed on the contemporary sources of voters’ affective orientations. While we did not explicitly test what supplants for social structure, we surmise that they are more multicausal than in the past and that political leaders (cf. Garzia et al. Citation2022), as well as prominent issue divides increasingly mould them. As these tend to change more rapidly than social structure, the affective and emotional reactions of citizens in the political realm will fluctuate more and also prove more porous than in the past.

We join other work that employs a diachronic perspective in electoral research (Dassonneville Citation2023; Garzia et al. Citation2022; Knutsen Citation2017; Mackie and Franklin Citation1992; Thomassen Citation2005). Such a perspective helps us avoid narrow conclusions about contemporary phenomena. If we want to understand why populists have been so successful with voters recently, it is pertinent not to mischaracterise their emotional appeal as unique. Rather, we need to identify in what ways it is novel and draw out the implications for mainstream parties’ ability to strike back today.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (4.1 MB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the Berlin-Potsdam-Hamburg Political Behaviour Workshop and the European Political Science Association 12th Annual Conference in Prague. We have in particular benefitted from engagement with Anton Könneke, Sebastian Hellmeier, Lena Maria Huber, Peter Jelavich, Richard S. Katz, Heike Klüver, Lilliana Mason, Matthias M. Matthijs, Lisa Perlman, Jan Rovny, Daniel Schlozman, Hanna Schwander as well as three anonymous reviewers and the editors of West European Politics. The responsibility for any remaining mistakes or misinterpretations is exclusively ours, of course.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tristan Klingelhöfer

Tristan Klingelhöfer is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in the Department of Political Science and the European Forum at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research interests lie at the intersection of intra-party politics, political communication, and political psychology with a focus on post-industrial democracies. His work has been published in The Journal of Politics, Party Politics, and the European Political Science Review. [[email protected]]

Simon Richter

Simon Richter is a political scientist and policy consultant, currently working as a policy officer. He obtained his PhD in Political Science from Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on political sociology, election campaigns, electoral behaviour, and political communication. [[email protected]]

Nicole Loew

Nicole Loew is a political analyst at Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and a PhD student at Freie Universität Berlin. Her research focuses on electoral behaviour, populism, and political parties. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Even explanations of populist success that do not squarely center on affect and emotions nevertheless invoke them as part of the theoretical justifications of their respective variables (e.g., Gidron and Hall Citation2017: S62–3; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019).

2 We draw here on the stylization of these theories by Kitschelt and Rehm (Citation2015). Realignment is a concept commonly used by the respective authors (e.g., Bornschier et al. Citation2021). Detachment is the term Kitschelt and Rehm (Citation2015) use to refer to a particular version of dealignment theory (e.g., Franklin Citation1992). In their view, detachment theory shares the sociological analysis of dealignment but adds specific arguments about party competition (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015: 184). Both realignment and detachment theory are relational theories about the alignments between parties and voters. They both start from the observation that the old cleavages disintegrate due to societal change and then provide different interpretations as to what explains voting on the individual level. In realignment theory, novel but equally durable societal divisions continue to matter. In dealignment and detachment theory, alignments are less stable and their content determined in the political realm, “induced by exogenous shocks or endogenous issue politics of office-seeking politicians” (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2015: 180).

3 This is not to say that parties of the New Left have generic economic policy preferences: Röth and Schwander (Citation2021), for instance, show that Green parties champion redistribution when in government. Crucially, however, they do so with respect to social investment policies rather than social consumption policies or taxation (Old Left).

4 See e.g., https://daserste.ndr.de/panorama/archiv/2016/Alternative-fuer-die-Politik-Emotionen-statt-Fakten,postfaktisch102.html; entered 10 December 2022.

5 A detailed description can be found in the Online Appendix in Table A1.

6 Scripts for the replication of the data analysis can be accessed online at https://osf.io/qfk92.

7 Below we graphically show the developments for the socio-demographic variables that theoretically relate to specific parties in cleavage theory. Equivalent graphs for the remaining variable-party combinations can be found in Section 2 of the Online Appendix. Reassuringly, we see (much) weaker effects of socio-demographic variables on the affect towards parties for which we did not derive theoretical expectations (e.g., being educated on affect towards the Social Democrats). Similarly, were we see theoretically unspecified effects, the changes in the effect sizes through time are also less pronounced (e.g., going to church often makes one very slightly feel less positively toward the PDS/Left, the effect is constant through time).

8 The data do contain an item relating to respondents’ occupation. However, it was collected in eight different versions throughout the period under investigation. More crucially, not even the most recent version – which was recorded between 1994 to 2020 – allows a matching to the occupational class scheme (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018) or the CECT scheme (Hooghe and Marks Citation2022).

9 The data structure would even allow for a more fine-grained inspection of the time trend on a monthly base. While this alternative analytical approach helps to damp some of the ‘jumps’ in the line of coefficients in , it also becomes more complex. However, the fundamental trend through time remains the same (Online Appendix Figure A5).

10 Our claim that it is in particular populists’ reliance on emotional appeals that drives the increasing overlap between party affect and vote choice might make one wonder whether the Left and the AfD should have particularly high coefficients. Only partly in line with this expectation, the coefficients for the Left and the Greens are the highest around 2.0 (Figure A4, Panel B in the Online Appendix). In contrast, the most recent coefficients for the CDU/CSU, SPD and FDP are closer to 1.75 and the one for the AfD to 1.5. Note that in our systemic account, a specific party’s heavily reliance on emotion in its rhetoric impacts not only its own supporters but also the degree to which supporters of other parties rely on their intuitive feelings of attachment and aversion. For instance, an emotionalization by the AfD can heighten the degree to which the supporters of their main opponent, the Greens, rely on their affect.

References

- Aarøe, Lene (2011). ‘Investigating Frame Strength: The Case of Episodic and Thematic Frames’, Political Communication, 28:2, 207–26.

- Bakker, Bert N., Gijs Schumacher, and Matthijs Rooduijn (2021). ‘Hot Politics? Affective Responses to Political Rhetoric’, American Political Science Review, 115:1, 150–64.

- Bankert, Alexa (2021). ‘Negative and Positive Partisanship in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Elections’, Political Behavior, 43:4, 1467–85.

- Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2006). ‘Are Emotions Natural Kinds?’, Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 1:1, 28–58.

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair (2007). Identity, Competition and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885–1985. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Blyth, Mark, and Richard S. Katz (2005). ‘From Catch-All Politics to Cartelisation: The Political Economy of the Cartel Party’, West European Politics, 28:1, 33–60.

- Bornschier, Simon (2010). ‘The New Cultural Divide and the Two-Dimensional Political Space in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 33:3, 419–44.

- Bornschier, Simon, Silja Häusermann, Delia Zollinger, and Céline Colombo (2021). ‘How “Us” and “Them” Relates to Voting Behavior—Social Structure, Social Identities, and Electoral Choice’, Comparative Political Studies, 54:12, 2087–122.

- Budge, Ian, Ivor Crewe, and Dennis Farlie, eds. (1976). Party Identification and Beyond: Representations of Voting and Party Competition. London: Wiley.

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes (1960). The American Voter. Unabridged Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Canovan, Margaret (1999). ‘Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy’, Political Studies, 47:1, 2–16.

- Dalton, Russell J., Scott C. Flanagan, and Paul A. Beck, eds. (1984). ‘Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies’, in Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? Princeton: Princeton University Press, 3–22.

- Dassonneville, Ruth (2023). Voters under Pressure: Group-Based Cross-Pressure and Electoral Volatility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Vries, Catherine E. (2018). ‘The Cosmopolitan-Parochial Divide: Changing Patterns of Party and Electoral Competition in The Netherlands and Beyond’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:11, 1541–65.

- Debus, Marc (2007). ‘Bestimmungsfaktoren des Wahlverhaltens in Deutschland bei den Bundestagswahlen 1987, 1998 und 2002: Eine Anwendung des Modells von Adams, Merrill und Grofman’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 48:2, 269–92.

- Debus, Marc (2010). ‘Soziale Konfliktlinien und Wahlverhalten: Eine Analyse der Determinanten der Wahlabsicht bei Bundestagswahlen von 1969 bis 2009’, KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 62:4, 731–49.

- Debus, Marc, and Jochen Müller (2019). ‘Soziale Konflikte, sozialer Wandel, sozialer Kontext und Wählerverhalten’, in Thorsten Faas, Oscar W. Gabriel, and Jürgen Maier (eds.), Politikwissenschaftliche Einstellungs- und Verhaltensforschung: Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 437–57.

- Demertzis, Nicolas (2019). ‘Populisms and Emotions’, in Paolo Cossarini and Fernando Vallespín (eds.), Populism and Passions: Democratic Legitimacy after Austerity. Abingdon: Routledge, 31–48.

- Dias, Nicholas, and Yphtach Lelkes (2022). ‘The Nature of Affective Polarization: Disentangling Policy Disagreement from Partisan Identity’, American Journal of Political Science, 66:3, 775–90.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2018). ‘Welfare Chauvinism in Populist Radical Right Platforms: The Role of Redistributive Justice Principles’, Social Policy & Administration, 52:1, 293–314.

- Enyedi, Zsolt (2005). ‘The Role of Agency in Cleavage Formation’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:5, 697–720.

- Enyedi, Zsolt (2008). ‘The Social and Attitudinal Basis of Political Parties: Cleavage Politics Revisited’, European Review, 16:3, 287–304.

- Flinders, Matthew, and Markus Hinterleitner (2022). ‘Party Politics vs. Grievance Politics: Competing Modes of Representative Democracy’, Society, 59:6, 672–81.

- Ford, Robert, and Will Jennings (2020). ‘The Changing Cleavage Politics of Western Europe’, Annual Review of Political Science, 23:1, 295–314.

- Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, Mannheim (2022). ‘Politbarometer 1977-2020 (Partielle Kumulation)’, GESIS, Köln. ZA2391 Datenfile Version 13.0.0, (accessed February 18, 2022).

- Franklin, Mark N. (1992). ‘The Decline of Cleavage Politics’, in Mark N. Franklin, Thomas T. Mackie, and Henry Valen (eds.), Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 383–405.

- Garry, John (2007). ‘Making “Party Identification” More Versatile: Operationalising the Concept for the Multiparty Setting’, Electoral Studies, 26:2, 346–58.

- Garzia, Diego, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, and Andrea De Angelis (2022). ‘Partisan Dealignment and the Personalisation of Politics in West European Parliamentary Democracies, 1961–2018’, West European Politics, 45:2, 311–34.

- Gerstlé, Jacques, and Alessandro Nai (2019). ‘Negativity, Emotionality and Populist Rhetoric in Election Campaigns Worldwide, and Their Effects on Media Attention and Electoral Success’, European Journal of Communication, 34:4, 410–44.

- Gidron, Noam, James Adams, and Will Horne (2020). American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gidron, Noam, James Adams, and Will Horne (2023). ‘Who Dislikes Whom? Affective Polarization between Pairs of Parties in Western Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 53:3, 997–1015.

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall (2017). ‘The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right’, The British Journal of Sociology, 68:S1, S57–S84.

- Gidron, Noam, Lior Sheffer, and Guy Mor (2022). ‘Validating the Feeling Thermometer as a Measure of Partisan Affect in Multi-Party Systems’, Electoral Studies, 80, 102542.

- Gingrich, Jane, and Silja Häusermann (2015). ‘The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and Consequences for the Welfare State’, Journal of European Social Policy, 25:1, 50–75.

- Hameleers, Michael, Linda Bos, and Claes H. de Vreese (2017). ‘“They Did It”: The Effects of Emotionalized Blame Attribution in Populist Communication’, Communication Research, 44:6, 870–900.

- Häusermann, Silja, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2015). ‘What Do Voters Want? Dimensions and Configurations in Individual-Level Preferences and Party Choice’, in Pablo Beramendi, Silja Häusermann, Herbert P. Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 202–30.

- Hölzl, Norbert (1974). Propagandaschlachten: Die österreichischen Wahlkämpfe 1945-1971. München: R. Oldenburg.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2018). ‘Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:1, 109–35.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2022). ‘The Social Roots of the Transnational Cleavage: Education, Occupation, and Sex (July 25, 2022)’, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4171743. or (accessed September 21, 2023).

- Ignazi, Piero (1992). ‘The Silent Counter-Revolution’, European Journal of Political Research, 22:1, 3–34.

- Ignazi, Piero (2021). ‘The Failure of Mainstream Parties and the Impact of New Challenger Parties in France, Italy and Spain’, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 51:1, 100–16.

- Inglehart, Ronald (1984). ‘The Changing Structure of Political Cleavages in Western Society’, in Russell J. Dalton, Scott C. Flanagan, and Paul A. Beck (eds.), Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? Princeton: Princeton University Press, 25–69.

- Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes (2012). ‘Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:3, 405–31.

- Katz, Richard S. (2013). ‘Should We Believe That Improved Intra-Party Democracy Would Arrest Party Decline?’, in William P. Cross and Richard S. Katz (eds.), The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 49–64.

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair (1995). ‘Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party’, Party Politics, 1:1, 5–28.

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair (2009). ‘The Cartel Party Thesis: A Restatement’, Perspectives on Politics, 7:4, 753–66.

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair (2018). Democracy and the Cartelization of Political Parties. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kessler, Thomas, and Susan Hollbach (2005). ‘Group-Based Emotions as Determinants of Ingroup Identification’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41:6, 677–85.

- Kinnvall, Catarina (2018). ‘Ontological Insecurities and Postcolonial Imaginaries: The Emotional Appeal of Populism’, Humanity & Society, 42:4, 523–43.

- Kirchheimer, Otto (1966). ‘The Transformation of the Western European Party Systems’, in Joseph LaPalombara and Myron Weiner (eds.), Political Parties and Political Development. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 177–200.

- Kitschelt, Herbert P. (1994). The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitschelt, Herbert P., and Philipp Rehm (2015). ‘Party Alignments: Change and Continuity’, in Pablo Beramendi, Silja Häusermann, Herbert P. Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 179–201.

- Knutsen, Oddbjørn (2017). Social Structure, Value Orientations and Party Choice in Western Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (1999). ‘Movements of the Left, Movements of the Right: Putting the Mobilization of Two New Types of Social Movements into Political Context’, in Herbert P. Kitschelt, Peter Lange, Gary Marks, and John D Stephens (eds.), Continuity and Change in Contemporary Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 398–423.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2010). ‘Restructuration of Partisan Politics and the Emergence of a New Cleavage Based on Values’, West European Politics, 33:3, 673–85.

- Ladd, Jonathan M., and Gabriel S. Lenz (2008). ‘Reassessing the Role of Anxiety in Vote Choice’, Political Psychology, 29:2, 275–96.

- Lipset, Seymour M., and Stein Rokkan (1967). ‘Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction’, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: The Free Press, 1–64.

- Lodge, Milton, and Charles S. Taber (2013). The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Loew, Nicole, and Thorsten Faas (2019). ‘Between Thin- and Host-Ideologies: How Populist Attitudes Interact with Policy Preferences in Shaping Voting Behaviour’, Representation, 55:4, 493–511.

- Mackie, Thomas T., and Mark N. Franklin (1992). ‘Electoral Change and Social Change’, in Mark N. Franklin, Thomas T. Mackie, and Henry Valen (eds.), Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Magni, Gabriele (2017). ‘It’s the Emotions, Stupid! Anger about the Economic Crisis, Low Political Efficacy, and Support for Populist Parties’, Electoral Studies, 50, 91–102.

- Marcus, George E. (1988). ‘The Structure of Emotional Response: 1984 Presidential Candidates’, American Political Science Review, 82:3, 737–61.

- Marcus, George E., Nicholas A. Valentino, Pavlos Vasilopoulos, and Martial Foucault (2019). ‘Applying the Theory of Affective Intelligence to Support for Authoritarian Policies and Parties’, Political Psychology, 40:S1, 109–39.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oesch, Daniel, and Line Rennwald (2018). ‘Electoral Competition in Europe’s New Tripolar Political Space: Class Voting for the Left, Centre-Right and Radical Right’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:4, 783–807.

- Pappi, Franz Urban, and Susumu Shikano (2002). ‘Die politisierte Sozialstruktur als mittelfristig stabile Basis einer deutschen Normalwahl’, KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 54:3, 444–75.

- Rabinowitz, George, and Stuart E. Macdonald (1989). ‘A Directional Theory of Issue Voting’, American Political Science Review, 83:1, 93–121.

- Richards, Barry (2004). ‘The Emotional Deficit in Political Communication’, Political Communication, 21:3, 339–52.

- Rico, Guillem, Marc Guinjoan, and Eva Anduiza (2017). ‘The Emotional Underpinnings of Populism: How Anger and Fear Affect Populist Attitudes’, Swiss Political Science Review, 23:4, 444–61.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Andrea L. P. Pirro, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Caterina Froio, Stijn van Kessel, Sarah L. de Lange, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart (2023a). ‘The PopuList: A Database of Populist, Far-Left, and Far-Right Parties Using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC)’, British Journal of Political Science, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000431 (accessed November 21, 2023).

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Andrea L. P. Pirro, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Caterina Froio, Stijn van Kessel, Sarah L. de Lange, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart (2023b). The PopuList 3.0: An Overview of Populist, Far-left and Far-right Parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org. (accessed November 21, 2023).

- Röth, Leonce, and Hanna Schwander (2021). ‘Greens in Government: The Distributive Policies of a Culturally Progressive Force’, West European Politics, 44:3, 661–89.

- Sani, Giacomo, and Giovanni Sartori (1983). ‘Polarization, Fragmentation and Competition in Western Democracies’, in Hans Daalder and Peter Mair (eds.), Western European Party Systems: Continuity & Change. Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications, 307–40.

- Sartori, Giovanni (1969). ‘From the Sociology of Politics to Political Sociology’, Government and Opposition, 4:2, 195–214.

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1975). The Semisovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. Boston: Wodsworth Cengage Learning.

- Schumacher, Gijs, Matthijs Rooduijn, and Bert N. Bakker (2022). ‘Hot Populism? Affective Responses to Antiestablishment Rhetoric’, Political Psychology, 43:5, 851–71.

- Smith, Eliot R., Charles R. Seger, and Diane M. Mackie (2007). ‘Can Emotions Be Truly Group Level? Evidence regarding Four Conceptual Criteria’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93:3, 431–46.

- Stubager, Rune (2009). ‘Education-Based Group Identity and Consciousness in the Authoritarian-Libertarian Value Conflict’, European Journal of Political Research, 48:2, 204–33.

- Thomassen, Jacques, ed. (2005). The European Voter: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wagner, Markus (2021). ‘Affective Polarization in Multiparty Systems’, Electoral Studies, 69, 102199.

- Wagner, Sarah, L. Constantin Wurthmann, and Jan Philipp Thomeczek (2023). ‘Bridging Left and Right? How Sahra Wagenknecht Could Change the German Party Landscape’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 64:3, 621–36.

- Ward, Dalston G., and Margit Tavits (2019). ‘How Partisan Affect Shapes Citizens’ Perception of the Political World’, Electoral Studies, 60, 102045.

- Weßels, Bernhard (2019). ‘Wahlverhalten sozialer Gruppen’, in Sigrid Roßteutscher, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Harald Schoen, Bernhard Weßels, and Christof Wolf (eds.), Zwischen Polarisierung und Beharrung: Die Bundestagswahl 2017. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 189–206.

- Widmann, Tobias (2021). ‘How Emotional Are Populists Really? Factors Explaining Emotional Appeals in the Communication of Political Parties’, Political Psychology, 42:1, 163–81.

- Wirz, Dominique (2018). ‘Persuasion through Emotion? An Experimental Test of the Emotion-Eliciting Nature of Populist Communication’, International Journal of Communication, 12:1, 1114–38.

- Wodak, Ruth (2015). The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage.

- Wüst, Andreas M., ed. (2003). Politbarometer. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

- Zollinger, Delia (2024). ‘Cleavage Identities in Voters’ Own Words: Harnessing Open-Ended Survey Responses’, American Journal of Political Science, 68:1, 139–159.