Abstract

Most studies of political rhetoric examine only political leadership or treat parties as unified actors. However, what happens where electoral systems incentivise candidates to diverge from stated party messaging during campaigns? This article uses novel data on political experience and candidate backgrounds from the 2022 French parliamentary elections to explore the individual drivers of campaigning behaviour. The choice of France, with its multiple and prominent radical right-wing parties, allows for the consideration of both within- and between-party differences in individual campaigning. Using the salient example of toxic rhetoric, findings demonstrate that even when party leaders publicly urge moderation, individual candidates do not necessarily follow along. This implies the need for additional focus on the individual-level drivers of political semantics, especially where candidates are apt to campaign independently, using social media platforms to communicate directly with citizens.

Studies of political rhetoric have greatly expanded what it means for something to be viewed as ‘political’ (Connolly Citation1993). Scholars from linguistics, communications, and political science have been particularly interested with messaging during elections, examining how political actors use their rhetoric to influence citizens. However, studies of political speeches have oftentimes been either experimental or theoretical (Lau and Rovner Citation2009). When observational data are used, these studies can face a unit of analysis problem, focussing primarily on the rhetoric of key party leaders or on documents that speak on behalf of political parties as a whole, such as manifestos or conference speeches, rather than on a full universe of political actors (e.g. Blassnig et al. Citation2019; Bracciale et al. Citation2021; Degani Citation2015; Elmelund-Præstekær and Svensson Citation2014).

While exceptions to this approach exist – especially in American politics research (e.g. Auter and Fine Citation2016; Druckman et al. Citation2020; Lau and Pomper Citation2002), most work still focusses on a narrow selection of candidates or a race with a limited field (see also Nai Citation2020; Nai and Maier Citation2020). The risk here is that these studies can mask the positions of individual politicians within political movements by focussing only on key individuals or organisational statements. Conversely, reducing the study of campaign rhetoric to the messaging of only parties and their leaders can miss out on the broader range of views that exist within a system.

Substantively, much of the campaign rhetoric literature focusses on negative campaigning (e.g. Haselmayer Citation2019; Mattes and Redlawsk Citation2015; Nai and Walter Citation2015). Although scholars have made the case that negative campaigning can be strategically effective, going too negative can cross a line and threaten democratic norms, whether through ad hominem personal attacks, hate speech, or disinformation (e.g. Brown Citation2017; Conrad et al. Citation2023; Nai and Maier Citation2020). Nowhere is the possibility for such abuses of negative political messaging more likely to appear than on social media platforms, such as Twitter/X, and from specific ideological corners, such as the far right (e.g. Ahmed and Pisoiu Citation2021; Åkerlund Citation2020; Calderón et al. Citation2020). This is especially important when one’s choice of technique can affect an election outcome, and even more so when it can damage the system where it takes place. However, such studies also require more careful attention to the determinants of individual campaign behaviour. This is particularly the case in electoral systems that provide an incentive to ‘go it alone’ and campaign as an individual, rather than as party foot soldiers.

We therefore assess the determinants of campaign behaviour by focussing on individual campaign rhetoric during the recent 2022 French parliamentary elections. Like in many countries, French politicians have made extensive use of social media over the past decade and especially on Twitter/X. As in many democracies, French political parties tend to be strong and national organisations that exert discipline and influence on their members. However, the French National Assembly is elected via a majoritarian electoral system of single-member districts, where candidates are ultimately more responsible for their electoral outcomes. This heightens the importance of individual campaigns in ways more akin to other major majoritarian democracies found across the world, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, India, and Canada, rather than the proportional representation systems more common to much of Europe. It also presents us with an important test case to focus on individual campaign rhetoric and its divergence from political parties and their leaders.

We are specifically concerned with a particular kind of negative campaigning, toxic online speech, which we believe can undermine the democratic qualities of elections. Our focus on France is justified by the historically strong presence of radical right-wing political parties (RRWPPs), embodied most recently by Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (Rassemblement National, RN). Given that extremist and authoritarian views that may be corrosive to democracy oftentimes come from RRWPPs (e.g. Italy’s Fratelli d’Italia, Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland, the US Republicans under former president Donald Trump), the prominence and persistence of the RN from within the multi-party French political system is specifically important to our analysis but comes with many relevant global parallels.

We depart from the existing and more limited analyses of campaign rhetoric by using original data on the backgrounds and online campaigning behaviours of all 6,310 candidates to compete during the 2022 French legislative elections, rather than the communications made on behalf of their parties by party leaders. Our expansive dataset can compare rhetoric used by RN candidates with the mainstream Ensemble (ENS) liberal bloc of President MacronFootnote2, the established right-wing (Les Républicains, LR), the leftist Nouvelle Union Populaire écologique et sociale (NUPES) blocFootnote3, and other smaller parties.Footnote4 Individual-level data allows us to explore individual drivers of campaign messaging from within each party bloc, such as candidate experience, age, gender, and seat competitiveness. Given that we are particularly interested in how individual rhetoric compares with broader party messaging, we explore whether more senior and experienced politicians present a more moderated, less toxic, discourse, when asked to by their party.

By analysing campaign rhetoric at the individual level, we question the extent to which party foot soldiers take campaigning cues from their leadership, and therefore the extent to which unified party statements are indeed representative of their candidates. For the RN, Marine Le Pen has made well-documented efforts to moderate the presentation of her party, hoping to attract mainstream voters and overcome the stigma of her father’s legacy for conspiracist and antisemitic views in leading the RN’s predecessor party, the National Front (Front National, FN). Such efforts include a well-known and ongoing de-demonisation (dédiabolisation) strategy and the rebranding of the FN to the RN in 2018, meant to enhance her party’s ‘respectability.’ Our analysis leverages the French context to examine the dynamics of online campaigns both within and between parties with a particular focus on the most problematic uses of negative campaigning, thereby contributing to the broader comparative literatures on campaign and election discourse, party politics, and RRWPPs.

Our results emphasise a strong need to address the micro foundations of political messaging. We find that RN politicians continue to use heightened levels of toxic speech online, both relative to mainstream parties and compared with more openly extremist groups, even when central party messaging advises rhetorical moderation. We also show that party seniority has little consistent effect on the moderation of candidate speech within a given party, although experienced politicians are generally less likely to resort to toxic speech patterns. This indicates that whilst Marine Le Pen’s de-demonisation strategy may have succeeded somewhat in rehabilitating her own image as a party leader, it has not extended to the campaign tactics of her party’s candidates. For the broader literature on campaign messaging, our findings cement the need to consider the approach of individual candidates more closely.

Social media and its importance for radical right-wing political parties

Social media platforms have become key spaces for political activism (Vergeer Citation2015). In particular, Twitter/X has functioned as an agenda-setter for political parties across Europe and beyond (Seethaler and Melischek Citation2019) and a broadcasting tool for accomplishments during election campaigns (Jungherr Citation2016). Studies of campaigning on the online platform have also served as useful indicators for inter-party competition (Frame and Brachotte Citation2015), while demonstrating similarities between online behaviours and the structural tendencies of more traditional, off-line campaigns (Obholzer and Daniel Citation2016). On the other hand, Twitter/X may follow some different ‘rules of the game,’ with a certain set of followers and a certain way of communicating. This is particularly relevant for our study of campaign messaging, insofar as Twitter/X has been shown to promulgate especially toxic language.

The determinants of toxic language in social media

Toxic language online has varied forms and causes (e.g. Leite et al. Citation2020; Nithyashree et al. Citation2022; Radfar et al. Citation2020). The context of online speech is important, where being corrected by an interlocutor raises the degree of language toxicity by the respondent (Mosleh et al. Citation2021). The platform also matters. For instance, on discussion boards, a deeper level of privacy is associated with a decreased usage of toxic language (Jakob et al. Citation2023). In addition, political comments written on non-political subreddits express lower levels of toxicity than those published on explicitly political ones (Rajadesingan et al. Citation2021). Taken together, the studies suggest that toxic speech online may be self-perpetuating (Kim et al. Citation2021). It also suggests that toxic speech has an element of performativity that is particularly exploitable in political situations.

This means that toxic speech both contributes to and is a function of political culture. For example, Navera (Citation2021) shows that in the case of Duterte’s Philippines, toxic speech used by politicians is an extension of a political culture already characterised by violence and excess, where insulting language is expected in the public discourse. Structural characteristics also matter, with toxic outrage seen as less common in consensus-oriented democracies than in majoritarian ones (Jakob et al. Citation2023). Divisive topics and polarising issues – common across many countries – can create fertile ground for toxic conversations (Pla and Hurtado Citation2018). And deceitful opinion leaders are especially likely to use uncivil ways of interacting online (Guldemond et al. Citation2022).

The radical right online

It is clear from the above that speech toxicity is important to track and that it oftentimes has a political element at its root. However, the preponderance of the academic literature on toxic speech relates mostly to consumers of social media, rather than to politicians speaking in toxic ways themselves. Given toxic speech’s power and prominence, we question the extent to which speech toxicity plays a role in the campaigning strategies of RRWPPs.

The use of social media by RRWPPs is especially commonplace, due to its ‘[embracing] an exclusionary counter public for challenging establishment voices and promoting reactionary social change’ (Walsh Citation2023: 2636). In terms of RRWPP online political speech, it has been described as an online continuation of the traditional features of a radical right-wing discourse: populism, the centrality of the leader’s figure, and the use of an emotional style (Bobba Citation2019). The rhetoric of RRWPPs online can be either tempered or angry (Åkerlund Citation2020) and echoes offline political stances in the ‘othering’ of select, marginalised groups that are presented as external to the nation (Awad et al. Citation2022; Sakki and Pettersson Citation2016).

As a consequence, scholars have examined how rhetoric deployed by RRWPP leaders like Matteo Salvini has exemplified the digital manifestation of ‘post-truth politics’ on Twitter/X (Evolvi Citation2023: 129–148). This phenomenon was particularly used during Covid times (Caiani et al. Citation2021) and even led to hate speech, which is to say ‘bias-motivated, hostile, malicious speech aimed at a person or a group of people because of some of their actual or perceived innate characteristics’ (Cohen-Almagor Citation2011: 1), as a communication tool. In sum, most political parties have made use of social media to campaign and set their party’s agenda and for radical right-wing political movements, this usage can amplify existing toxic patterns of political rhetoric.

The French far right online

The use of social media in France is emblematic of broader online trends in the study of political communications. French party members campaign actively on social media and scholars have studied their sociological characteristics (Theviot Citation2013) and rhetorical approaches (Boyadjian Citation2016). Of particular prominence are French right-wing political voices, which have been strongly active on the internet (Froio Citation2018). Right-wing online communities provide a varied offering, taking the form of a loosely structured galaxy where different groups address different audiences around the same principles of extreme nationalism and xenophobia (Froio Citation2017: 69–70). However, whilst a ‘distinction between institutionalized and non-institutionalized groups’ (Klein and Muis Citation2019: 558) exists in the European far right-wing web, ‘the French online network is relatively cohesive and centralized around a party’ (p. 557), which has traditionally been the FN/RN.

Julien Boyadjian explains that the National Front’s strategy on the internet can be summarised in three ways:

(1) The web and the social media are an instrument of mobilisation that allow the FN to reinforce its electoral legitimacy by arguing the ‘strength in numbers’, (2) the Internet constitutes for the FN an instrument and a showcase of its normalization strategy, and (3) On the fringes of this institutional showcase, the web allows a less controlled Frontist voice to be deployed and to balance the official discourse of the party. If these statements can sometimes be detrimental to the party’s normalization strategy, they nonetheless allow it to ensure ‘under the table’ its doctrinal logic of radicalization. (Boyadjian Citation2015: 142–143)

The National Front was founded in 1972, emanating from the neo-fascist movement New Order (Ordre Nouveau). The new party included several who were nostalgic for the Vichy regime among its executives, as well as former supporters of French Algeria. Although structured initially around anti-communism, the discourse of the National Front quickly politicised the issues of insecurity and immigration. The FN remained a presence in French politics throughout the 1980s and 1990s, rising to an apex during the 2002 presidential contest, where Jean Marie Le Pen advanced to a second-round face-off with incumbent Jacques Chirac. The public outcry was immediate and swift, both at home and abroad, and led to stagnating electoral results in the years thereafter. Thereafter, the FN began to pursue an objective of de-demonisation under Marine Le Pen. Becoming leader in 2011, she followed a ‘vote maximising strategy’ (Ivaldi Citation2015), where the party leadership agreed to renovate its discourse and policy positions to look for ‘respectabilisation’ (Dézé Citation2013: 46).

Similar to other populist radical right parties in Western Europe, however, the FN/RN suffers from a dual constraint: it must gain respectability to attract new voters outside its usual electoral basis, whilst also asserting its ideological identity to retain regular supporters (Dézé Citation2015). As such, opting for an ambivalent attitude can constitute an effective strategy for RRWPPs (Koedam Citation2021; Rovny Citation2013): position blurring can be adopted with the intent of gaining broader popularity (Rovny Citation2012). Such blurring therefore can be interpreted as a deliberate choice taken by political leaders (Koedam Citation2021). More generally, and beyond the only case of the radical right, valence populist parties voluntarily tend to adopt blurry positions (Zulianello and Larsen Citation2023).

The FN/RN has to balance the French public’s low acceptance for far-right positions with the increased institutionalisation of radical right parties (Bjånesøy et al. Citation2023). An apparent moderating stance at one level of the party can mask the continued pervasiveness of traditional far right-wing positions at other levels, as exemplified by Marine Le Pen’s co-opting of supposedly feminist values from a nativist perspective (Leconte Citation2020). More mainstream, centre-left parties might also take advantage of this dilemma and use Twitter/X and other social media campaign strategies to further demonise far right parties, potentially to appeal to their own voters (Schwörer and Fernández-García Citation2021). To summarise, de-demonisation may have led to a public repackaging of the FN/RN at an official party or leadership level (Facchini and Jaeck Citation2021), but normalisation may not have prevented party figures from maintaining extremist views. This is particularly apparent in the toxic language used by its politicians during online social media campaigns, where parties can exert less control over candidate communication.

The context of the 2022 legislative elections

The 2022 elections presented both challenge and opportunity for the RN, where the results of 2017 emboldened its position as the principal opposition to Macron (Durovic Citation2023). Although the party’s historical attachment to right-wing radical rhetoric and nativist base persisted, the RN faced a new source of competition from Éric Zemmour, who declared his candidacy for president and announced the creation of his own political party in late 2021 – Reconquest. Zemmour was well known as a journalist and a columnist during the 2010s, particularly because of his controversial statements on cultural issues, such as immigration, multiculturalism, Islam, gender equality, and feminism. As a new political figure, he criticised Marine Le Pen for being too ‘moderate’ on identity-related themes, as well as for her supposed lack of moral conservatism. These divergent right-wing strategies would come to a head throughout the 2022 electoral cycle, with particularly gendered impacts for right-wing voting behaviour (Mayer Citation2022).

Furthermore, following the failures of the RN during the 2021 regional and departmental elections, the media framing of Marine Le Pen’s renewed presidential candidacy in 2022 was structured around the idea of the inevitability of her loss against the incumbent president, Emmanuel Macron. To make matters worse, part of the RN’s leading figures decided to leave the party and join Éric Zemmour, such as MEP Nicolas Bay, Senator Stéphane Ravier, and even the niece of Marine Le Pen, former MP Marion Maréchal. Therefore, the campaign for the 2022 presidential election was characterised by deep intra-competition within the radical right. The RN needed to both outflank its extremist competitor in the form of REQ, whilst also retaining fidelity to its de-demonisation strategy (see also Startin Citation2022).

Theory and hypotheses

As an indicative RRWPP, we have already noted the proclivity for the RN to rely heavily on online campaigning, particularly via social media. This was especially true of the above-average interest paid to the 2022 legislative races. At the same time, the RN and its leadership have been at pains to renovate their image, particularly in the face of Zemmour and the upstart REQ movement. Within these dynamics, we explore the extent to which the online campaign rhetoric of individual candidates relates both to one another (within the party), as well as to the individual backgrounds of candidates themselves. Doing so provides us with a more nuanced view than a simple analysis of the party leadership or other central party documents, allowing for us to directly test the extent to which party semantics can be considered unified.

At an inter-party level, the narrative of de-demonisation proposed by the RN leadership would have us expect to see less toxicity in the campaigns of RN candidates, with moderated behaviours across all RN candidates, especially relative to the other French RRWPPs. For the context of the 2022 legislative elections, this would imply that while RN candidates may still be more extremist in their discourse than candidates from the incumbent ENS and the mainstream conservative LR bloc, or the left-wing NUPES alliance, they should be more moderate than those from REQ. Given the heavy use of Twitter/X during the campaign, we can observe whether this moderation is present in the discourse of the candidates’ individual online campaigns.

The flipside is that Zemmour’s more radical agenda should correspondingly lead to a more radical rhetoric for him and his party, with more toxic speech on Twitter/X. There are also systemic reasons to radicalise communication efforts to distinguish themselves from the RN, partly due to the party’s newness. Young parties are more apt to activate their activists through a connective action logic: the joint use of communication and connectivity by political organisations to bring citizens into the digital field (Doroshenko et al. Citation2019). A similar mechanism might also be expected from the fringe UplF collective, who – although their constituent party positions vary – might use more radical tactics as a minor group of parties, hoping to increase their visibility in a majoritarian electoral system that favours large parties. This should mean that the RN should contrast with REQ and UplF in terms of its discourse strategies, appearing more like the established LR or the governing ENS blocs:

Hypothesis 1: Candidates from RN will use more moderate (less toxic) rhetoric than candidates from REQ or UplF.

Indeed, when political organisations exert internal party discipline, their candidates tend to occupy the role of ‘party brand ambassadors’ (Marland and Wagner Citation2020). Even in a majoritarian electoral system, personalisation dynamics can be prevented by the dual role of parties as central gatekeepers to candidate nomination and access to party resource supplies (Bøggild and Helboe Pedersen Citation2018). This discipline should extend to the contents of campaign messaging: when candidates run a campaign that is focussed on policy proposals, they should be more inclined to give importance to their movement’s manifesto (Eder et al. Citation2017). Candidates elected to higher office have also been affected by a party’s socialisation process, meaning that they are less likely to break the party line (Mai and Wenzelburger Citation2023; Rehmert Citation2022).

We therefore expect that party members with prior elected experience will be particularly beholden to party messaging. Experienced politicians should be more likely to hold the party line of de-demonisation and exhibit less toxicity on Twitter/X. This should be particularly true within the context of the RN, where the most central players to serve as candidates will also be the most likely to follow the cues of the party leadership and focus on a moderated (‘de-demonised’) rhetoric.

Hypothesis 2: Candidates with previous political experience will use more moderated (less toxic) rhetoric than political novices.

Of course, we expect that right-wing candidates will still maintain extreme substantive positions on key issues of importance to their base. The de-demonisation and normalisation approaches do not reject extremist positions, but rather focus on the way in which these positions are discussed. In other words, we still expect RN candidates to talk about issues such as the economic precarity of their base in the face of liberal Europeanisation, or the rejection of migrants and their supposedly increased prevalence on French culture – it is just that these positions should be broadcast in a more ‘respectable’ and less toxic way.

As with the euphemising strategies discussed above, de-demonisation may only run skin deep. If the de-demonisation thesis is borne out, we would therefore expect that RN candidates should be smooth operators who are able to both toe the party line when it comes to signalling cosmetic forms of moderation, all while still relying upon the use of dog whistles and other euphemisms to project a connection to the party’s radical past, whilst attracting votes from larger, more mainstream voting bases. In other words, we expect that:

Hypothesis 3: Candidates from RN will be especially careful to use more moderated (less toxic) rhetoric when discussing key issue areas for right-wing citizens, relative to candidates from REQ and UplF.

Data and method

We test our hypotheses using original Twitter/X data for all candidates for the French legislative election in June 2022. A team of manual coders sourced and checked all party lists for all candidates who were standing for election in each French constituency (N = 6310). Coders collected candidates’ Twitter/X handles, both personal and dedicated campaign ones, and collated this information alongside publicly available demographic indicators and previous political experience and educational expertise.

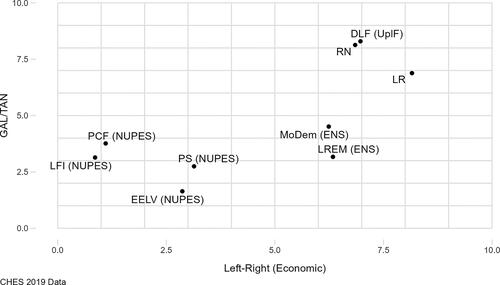

We relied only on publicly available information, typically coming from the candidates themselves, like their social media profiles or campaign websites, or from news media, such as interviews with local newspapers. Using the collected Twitter/X handles that we sourced, the Twitter/X academic API was used to collect all Tweets published, beginning three months prior to the legislative electionsFootnote5. In this analysis, we include tweets from all candidates with active Twitter/X accounts that ran on the REQ, RN, UplF, LR, ENS and NUPES party lists. Footnote6 The overall ideological positioning of these parties is displayed in , using the most recent mean values from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. Citation2015). As REQ was a new party in 2022, it is not yet available in CHES data. However, we would anticipate the party to score higher than the RN on both the economic left-right and cultural GAL-TAN dimensions (i.e. more right-leaning economically and more traditional-authoritarian-nationalist culturally).

From those parties, we analysed data on all candidates with active Twitter accounts (N = 2042, i.e. 63.4% of those parties’ candidates).Footnote7. Out of the tweets from these 2042 candidates, retweets were removed, but replies and quoted tweets were retained, resulting in a final sample of 359,369 Tweets. Mentions (i.e. direct replies to collected tweets from interlocuters) were not collected.

Tweets from candidates were analysed using the Perspective API machine learning transformer modelFootnote8, which allows us to assign each tweet a score of toxicity, which is our main outcome of interest. The Perspective API uses a well-tested approach to detect toxic speech (Lees Citation2022) that can also analyse text across a number of languages, including French (Rieder and Skop Citation2021), which is not the case for many other automated textual analysis machine learning models. The model was pre-trained using content moderation data from the comment sections of major global newspapers, such as The Financial Times, The New York Times, El País, and Le Monde, and can conceptualise what would be considered toxic speech in both a French and a cross-cultural context (Rieder and Skop Citation2021).

Perspective API works through scoring each unit of text, using probabilities between 0 and 1, where a higher score indicates a higher likelihood of the text being perceived as containing the examined attribute (Rieder and Skop Citation2021). We use the ‘Toxicity’ measure generated by the API, which is defined as ‘a rude, disrespectful, or unreasonable comment that is likely to make people leave a discussion’ (Perspective API Citation2023).

For example, in our data, a Tweet criticising Jean-Luc Mélenchon, which reads ‘Bastard, dirty traitor, collaborator and accomplice of these assassins. And to think that so many idiots follow this neo-fascist.’Footnote9, is rated at 0.699 (out of 1.0) because it clearly uses disrespectful language. On the other hand, a Tweet presenting a campaign video for REQ which reads ‘2022 campaign video from Éric Zemmour: ‘Choose your people, choose our history, choose our identity, choose our future, choose France.’ #I’mVotingZemmour10April’Footnote10 is only rated as 0.058, as the speech – although relating to an extremist programmatic position – is not presented in an overtly rude or toxic way. The level of toxicity for each Tweet is therefore our main dependent variable. We view toxic speech to be the antithesis of the moderated discourse posited by our hypotheses.

In later analyses, we examine the main topic of discussion used in each tweet, to test our hypothesis about moderated discourse on key RRWPP topics. We do this using a bi-term topic model (BTM) for short texts (Yan et al. Citation2013). This model is like a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model in that it looks at the co-occurrence of terms in a text corpus and uses deviations from what would be expected, given the null term distribution, to identify topics. Unlike LDA models, however, the BTM analyses co-occurrence across the whole corpus of text provided – rather than co-occurrence within individual documents. This allows for better topic identification when dealing with short texts, such as tweets.

For our topic modelling, the corpus of text provided includes all collected tweets from ENS, LR, RN, REQ, and UplF candidates, as we were particularly interested in the comparative use of toxic language in discussing right-wing issues. Text was cleaned to remove punctuation and URLs and was then lemmatised. Only valid French words of character length greater than one were used to identify topics and all other words were ignored. Once a set of latent topics were identified by the BTM, each tweet was assigned a probability of belonging to that topic. We then classified the tweet as belonging to the topic for which it had the highest probability.

Because the BTM is agnostic about the substantive meaning of the derived topics, we then used a manual approach to review the most common key terms identified by each topic and created a set of substantive labels that describe each topic’s contents. In some cases, topics aligned straightforwardly with key policy areas, such as energy policy or the economy. Other topics relate to political parties, ideologies, constellations of political values, and even the logistical programmatics of the election itself. A full accounting of the topics generated by the BTM, their corresponding labels for use in the analysis, and a selection of illustrative tweets for each topic is found in the online appendices.Footnote11

In order to test whether the level of toxicity varies across parties, we include the tweeting candidate’s political party as our main independent variable. To test for the effect of past political experience on toxicity, we include three separate variables. First, we measure the highest level of office that the candidate held previously. This is an ordinal variable, where the highest level of office was categorised as none (no previous political office), local (e.g. a municipal councillor, mayor, etc.), regional (e.g. a regional councillor, regional council president, etc.) or national and above (e.g. Member of Parliament, Member of the European Parliament, member of a party’s national executive body, etc.). We then include whether the candidate has previous experience serving within the political party’s internal organisation (whether at the local, regional, or national level – such as in a party executive). Third and finally, we include a count for the number of times the candidate has previously run in national legislative elections.Footnote12

Alongside these main independent variables, several control variables were also included to account for other potential determinants of speech toxicity. We include demographic controls for age and male, as well as the number of Twitter/X followers and total number of Tweets to account for differences in tweeting behaviour. Finally, we control for the lead of the winning presidential candidate in the candidate’s district during the second round of the 2022 Presidential Election as a measure for the competitiveness of the district in which candidates are standing. All continuous independent variables, except for count of previous runs, were scaled and centred to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one.

Results and analysis

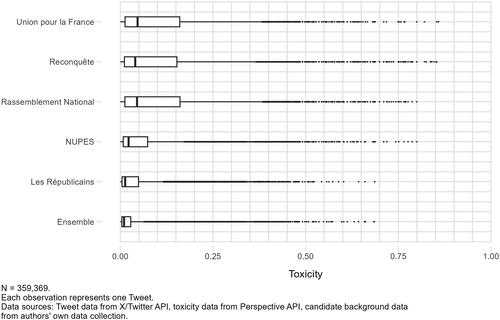

We begin by assessing how toxicity varies across our two independent variables of political party and highest attained office. We use boxplots to analyse the relationship between toxicity and highest office level, as stratified by party, to visually explore how these two variables interact across political party background. Across the 359,369 tweets that we analysed, toxicity scores ranged from 0.0000001 to 0.859 (mean= 0.075 and median= 0.023). Scores were heavily right skewed, with most tweets having low toxicity levels. shows how this distribution varies across our six main party groupings.

The distribution of our data indicates that the three RRWPP groupings (UplF, REQ, RN) have a notably higher average toxicity level, as compared with the centre-right LR, the centrist ENS and the left-wing NUPES. Candidates from UplF, REQ, and RN display a higher average level of toxicity, a higher maximum level of toxicity, and a broader range of typical toxic speech (i.e. wider boxes for average users). However, relevant for our analysis of speech patterns from within the right wing, tweets by RN candidates do not differ substantially in their degree of toxicity that from the other RRWPPs. This may indicate that the de-demonisation strategy touted by the RN is not actually taking root beyond the party leadership and its central messaging.

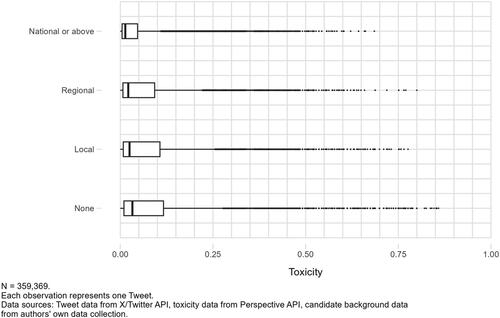

shows how toxicity is displayed across the highest attained office level achieved, by candidate, for all parties analysed. Tweets from candidates who had not previously held political office do appear to have above average and higher maximum toxicity levels, as compared with those who had held some kind of political office. Among those with previous political experience, as the level of the office held increases, the average toxicity levels appear to decrease. This may indicate that political experience has a moderating effect on outward displays of toxicity. Descriptive information for the level of experience and toxicity, broken down by party, is found in the online appendices.

Regression analysis

In order to test these relationships formally, we use a quasi-Poisson regression with robust standard errors to account for the clustering of tweets within individual candidates. We select the Poisson distribution due to the highly skewed nature of the toxicity variable and a quasi-maximum likelihood estimation to allow for deviations from the assumptions of a Poisson distribution. This was found to perform better than linear regression on the log-transformed toxicity variable, which produced heteroskedastic residuals. Multilevel models were also considered to account for the clustering of tweets within candidates; however, these models failed to converge. Full results for each model can be found in the online appendices.

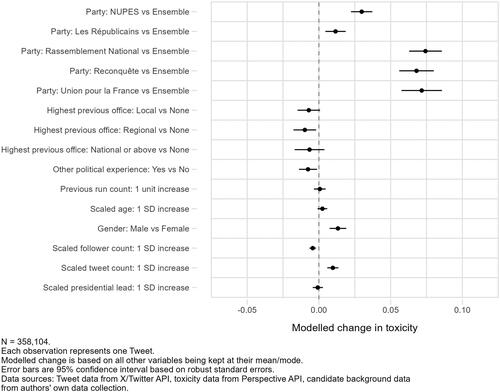

Our models generally confirm what was observed in the boxplots from and . Tweets from RN, REQ, and UplF candidates all had higher levels of toxicity than mainstream candidates and these differences are statistically significant, when controlled for by additional factors. However, once we control for party differences, we no longer see a statistically significant effect for the highest level of office held by a candidate on their associated toxicity score. This suggests that the differences observed in are being driven by different levels of experience present among candidates from different parties.

More specifically, within party, the level of office previously held does not show a significant association with toxicity for the most part, with only those who have held regional positions having a slightly lower toxicity than those who had not held any position. As for our other measures of previous experience, the count of previous runs was not significant, but having held an internal party role (other political experience) was associated with slightly lower levels of toxicity, even when controlling for party.

provides marginal effects plots for quantities of interest from our pooled model (Model 3), which includes all candidates analysed, controlled for by party and level of previous experience. As mentioned above, greater toxicity is associated with being from a RRWPP (and to a lesser extent, NUPES and LR) compared to ENS, while measures of previous experience are either non-significant or have only a small effect. Being a man, tweeting more, and having fewer followers are all associated with higher toxicity, with candidate age and district competitiveness non-significant.

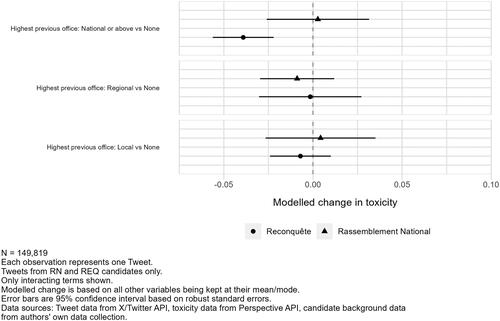

To directly compare between the two main RRWPPs, we next subset our data to analyse only tweets from RN and REQ candidates. To test if the effect of experience varies between the two parties, we introduce an interaction term between highest previous office and party, as well as the covariates from Model 3. We find that having had experience at national or higher levels has a negative and significant effect on the level of toxicity for REQ candidates, but not for RN candidates. These findings should be taken with caution, given the generally smaller number of candidates in RN and REQ with national or supranational experience, compared with the other parties. In sum, the subsample results offer limited support for Hypothesis 2, where we proposed that seniority within a party would be associated with more moderated behaviour, although the party where this mechanism may appear is among REQ and not RN candidates. Marginal effects are provided in (from Model 4 in Table A2).

Topic modelling

Having considered the impact of candidate party and political experience on their level of tweet toxicity, we now shift our attention to the substance of candidate tweets, using the BTM approach described above. We begin by assessing the extent to which candidates from different parties were inclined to tweet about specific topics. displays the proportion of tweets per topic, both overall and by party. The residual model topic for all tweets is ‘general’ and constitutes a large portion of the tweets, meaning that the tweet was not deemed as likely to fall into one of the other defined topics, relative to the general topic. However, among the remaining topics, we do see interesting party-level differences.

Table 1. Distribution of topics overall and by party (%).

For example, ENS candidates were relatively more likely to discuss domestic challenges in French politics than the other parties, as well as the election campaign itself. Right-wing parties were more inclined to discuss specific policy areas of concern, such as law and order issues (e.g. policing and immigration control). They also were much more likely to discuss political parties and opposing party leaders – oftentimes as part of attacks on Macron and his party directly.

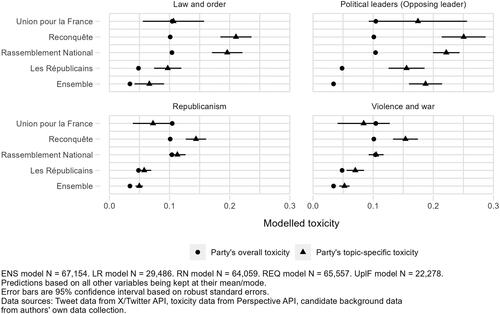

Given the partisan variation in topics discussed, we shift our attention to whether certain parties were more apt to use toxic language when discussing certain topics. We begin by analysing the effect of topic choice on our outcome of interest, tweet toxicity. This allows us to compare the extent to which certain topics are associated with more toxicity. We retain our unit of analysis at the tweet level, focussing on the differential effect of the individual topics from , relative to the ‘general topic’ for tweets that did not fall into any of these specific categories. Controls are retained at the party and individual levels and robust standard errors are clustered at the individual candidate. A full set of results is found in Online Appendix F. Because we suspect that the way that certain topics are discussed may vary in their level of toxicity across party, we also run this model stratified by party and plot a series of predicted levels of toxicity for select topics of interest and compare them with each party’s mean level of toxicity. Models for each party subset are also included in Online Appendix G. Plots are included in .

As previously identified, RRWPP candidates are all more toxic in their tweets than the incumbent ENS and the centre right LR. That said, certain topics – such as law and order and discussions of opposing political leaders – lead to more toxic speech. Both REQ and RN candidates were about twice as toxic when tweeting about law-and-order issues, compared with LR candidates, and about three times as toxic as Macron’s ENS candidates. This flies in the face of the ‘de-demonisation’ expectation. On other topics, however, only REQ was notably more toxic than their overall mean. This is particularly notable for tweets having to do with violence and war, as well as for tweets discussing the traditional ‘Republican’ values of France and suggests that some topics may be discussed in more extreme ways by REQ candidates than by the RN and others.

Conclusion

Studies of political discourse have rightly increased their focus on negative campaigning strategies, which include the use of social media and other forms of online campaigning. Such campaigns have the potential to negatively impact on democratic elections when negative campaign rhetoric crosses the line into toxic speech. As such, it is important to consider its drivers and determinants. Even though a few likely suspects from extremist parties are the most likely drivers of toxic speech, contemporary scholarship is oftentimes quick to conflate a party’s stance with its leader’s discourse, or to project the voice of one politician onto assumptions made about the full party.

We demonstrate the need for increased attention to the micro foundations of political rhetoric in campaigns, by focussing on the determinants of toxic speech patterns in the tweets of French candidates during the 2022 legislative elections. France is used as an important instance of majoritarian elections, where the incentives for individual campaigning are highest. It is also notable for its longstanding and prominent RRWPP movements. Although the current political Zeitgeist of advanced democracies has borne witness to a flurry of RRWPPs in other contexts, many of these have been short-lived or have failed to transition from protest movements at election time to organised parties of government with a complete platform. On the other hand, the successes of these movements have played a role in the seduction of longstanding, mainstream parties to mimic right-wing and populist tropes – therefore normalising extremist behaviours and positions.

In the French system, we see a story with broadly comparable elements to what is taking place in other Western democracies. However, the trajectory differs, insofar as instead of a mainstream party trending to the extremes, we witness the example of the RN – an extremist party – noisily attempting to recast itself as mainstream. Whatever the outward intentions of the leadership of the RN in the form of Marine Le Pen, however, the reality of the RN’s campaigning rhetoric tells a very different story.

We observe that despite a unified party messaging strategy of de-demonisation and attempts by party leaders to normalise their campaign discourse, individual RN candidates still use toxic tweeting as a part of their campaign strategies at significantly higher rates than those of the mainstream ENS and LR parties. Moreover, the language of RN candidates is not dissimilar from the speech patterns observed among REQ candidates – who ostensibly come from a more unabashedly extremist political party. We therefore resoundingly reject our Hypothesis 1, which predicted that RN candidates would indeed moderate their speech patterns, as advertised by both the party-level and political-leader de-demonisation strategy.

In terms of the individual determinants of toxic speech, we observe a visible pattern of candidates from high-level political backgrounds appearing to use more moderated language as they increase from political novices to seasoned veterans. However, this effect is shown to be mostly insignificant when controlled for by party. We therefore offer only indirect support for our assumption in Hypothesis 2 that the more experienced a politician becomes, the more likely they are to use less toxic language in online campaigns. Interestingly, those RN candidates with previous national or supranational experience were not significantly more moderated in their speech, as compared with REQ candidates. For our assessment of party-level discourse, this indicates that even the most senior members of political parties may not follow a unified party strategy.

Finally, our use of topic modelling identifies several common themes that were discussed during the election. Whereas some of these topics were purely logistical or even informational, other tweets were clearly related to core policy areas and societal concerns. For a number of these topics – such as law and order and discussing opposing political leaders – there were clear associations between party of origin and the heightened use of toxic language. Combining our topic indicators with a measure of toxicity, we observed that in many cases, RRWPPs were indeed more toxic in their discussion of key areas of their policy platforms. In other areas that might be expected to lend themselves to toxic speech, such as the discussion of Republican values, politicians have seemingly become more careful to speak in less toxic ways about polemical topics. More neutral topics – such as information about the election itself, energy policy, or discussions of public service – were all less likely to be discussed toxically than uncategorised tweets, regardless of party. This adds further scepticism to whether de-demonisation is specifically taking root within the RN.

Future research should continue to probe the individual determinants of political discourse, as well as the direct of effects of political parties and their leaders to curb the ability of candidates to go rogue from the party script. This might entail comparing our results from the French majoritarian context with a more proportional set of elections, such as in the Netherlands, where RRWPPs are also major players but parties have stricter control over the electoral fortunes of their candidates. Another area for further exploration might be the comparative use of political rhetoric and negative campaigning across platforms. Whereas French candidates have a great deal of individual agency in the promotion of their views on social media, they may be more constrained to follow party principals. For now, what we can say with great confidence is that the French legislative contest contained political discourse of all kinds – and much of this appears to have come down to the choices and strategies of individual candidates, rather than those promoted by their parties.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (964.6 KB)Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dan Pemstein and Brigitte Seim for inviting us to take part in this project. We especially wish to thank Jake Dennis, Jack Templeton, Ellen Partington, James McGrath, Bhadra Pisharasiar, Miriam Iordache, and Kirtana Gopakumar for their assistance with the data collection. Thanks also to Steven Wilson for his assistance in harvesting the corpus of tweets that were used in our analysis. Thanks to Andrew Roe-Crines, Anthony Kevins, Elisa Deiss-Heilbig, the two anonymous reviewers, and the many participants of the PSA, EPSA, and Loughborough University workshops in political communication for their helpful comments on previous drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

William T. Daniel

William T. Daniel is an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the University of Nottingham, where he co-directs the REPRESENT Research Centre for the Study of Parties and Democracy. His research interests include political careers, legislative and party politics, digital campaigning, and gender and representation. Previous work has been published by Oxford University Press and appears in The Journal of Politics, European Union Politics, and Journal of Common Market Studies, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Elise Frelin

Elise Frelin is a doctoral candidate and part-time lecturer at the Department of Government & Public Policy, University of Strathclyde. Her research focuses on parties’ issue competition and electoral campaigning on social media, using text analysis. [[email protected]]

Max-Valentin Robert

Max-Valentin Robert is a postdoctoral researcher in political science at the European School of Political and Social Sciences (ESPOL): Catholic University of Lille. His research interests include political parties, electoral behaviour, (de-)democratization and political radicalism. He has published in French Politics, Turkish Studies and the Journal of Contemporary European Studies. [[email protected]]

Laurence Rowley-Abel

Laurence Rowley-Abel is a postgraduate researcher at the Advanced Care Research Centre, University of Edinburgh. His research interests include quantitative modelling of social inequalities and healthcare outcomes, with a particular focus on the accumulated impact of stress in later life. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Authors’ names are listed alphabetically.

2 Referred more commonly in the English press by its previous name, La République en Marche, LREM.

3 Formed for the 2022 legislative elections, the NUPES electoral alliance was comprised of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s populist France Unbowed movement (La France Insoumise, LFI), the longstanding Socialist Party (Parti socialiste, PS) and French Communist Party (Parti communiste français, PCF), Europe Ecology – The Greens (Europe Écologie – Les Verts, EELV), and a handful of other, predominantly smaller, green parties.

4 We examine candidates from Éric Zemmour’s Reconquest (Reconquête, REQ) party, along with the ‘Union for France’ bloc (Union pour la France, UplF), which brings together France Arise (Debout la France), The Patriots (Les Patriotes) and Frexit Generation (Génération Frexit).

5 The corpus of tweets that we analyse was harvested and made available to us by project partners at the Digital Society Project, using Twitter/X handles that we sourced manually.

6 For this analysis, we exclude a range of candidates from minor parties that focus on single-issue areas (i.e. animal rights activists), regional movements (i.e. Corsican separatists), and several ideological fringe movements with national vote shares of less than two per cent.

7 A full breakdown of Twitter/X usage by party is available in Online Appendix A.

8 Accessible here: https://perspectiveapi.com.

9 Original French text: ‘Enfoiré, sale traitre, collabo, complice de ces assassins. Et dire que bon nombre d’abrutis suivent ce néo fa.’ Tweet (published on 22 March 2022) available at: https://twitter.com/ggfaivre/status/1506145461241061376

10 Original French text: ‘Le clip de campagne d’Eric Zemmour 2022. « Choisissez votre peuple, Choisissez notre histoire, Choisissez notre identité, Choisissez notre avenir, Choisissez la France. » #JeVoteZemmourLe10avril.’ Tweet (published on 5 April 2022) available at: https://twitter.com/AnneSophieDesir/status/1511348781085868036.

11 One especially prominent topic, related to comments about political leaders, was then broken into subtopics, to distinguish between tweets mentioning leaders from a candidate’s own party and those mentioning leaders from an opposing party – since these would be expected to yield different types of rhetoric. This was done by searching in the tweet text for mentions of either the main party leaders’ names (including variations and nicknames) or their Twitter/X handles and then categorising them as mentioning their own leader, an opposing leader or other (i.e. none of the searched leaders were mentioned). Full details are provided in the Online Appendices.

12 A full accounting of control variables is included in Online Appendix F and Online Appendix G.

References

- Ahmed, Reem, and Daniela Pisoiu (2021). ‘Uniting the Far Right: How the Far-Right Extremist, New Right, and Populist Frames Overlap on Twitter – A German Case Study’, European Societies, 23:2, 232–54.

- Åkerlund, Mathilda (2020). ‘The Importance of Influential Users in (Re)Producing Swedish Far-Right Discourse on Twitter’, European Journal of Communication, 35:6, 613–28.

- Auter, Zachary J., and Jeffrey A. Fine (2016). ‘Negative Campaigning in the Social Media Age: Attack Advertising on Facebook’, Political Behavior, 38:4, 999–1020.

- Awad, Sarah, Nicole Doerr, and Anita Nissen (2022). ‘Far-Right Boundary Construction towards the “Other”: Visual Communication of Danish People’s Party on Social Media’, The British Journal of Sociology, 73:5, 985–1005.

- Bakker, Ryan, Catherine de Vries, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Anna Vachudova (2015). ‘Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010’, Party Politics, 21:1, 143–52.

- Bjånesøy, Lise, Elisabeth Ivarsflaten, and Lars Erik Berntzen (2023). ‘Public Political Tolerance of the Far Right in Contemporary Western Europe’, West European Politics, 46:7, 1264–87.

- Blassnig, Sina, Florin Büchel, Nicole Ernst, and Sven Engesser (2019). ‘Populism and Informal Fallacies: An Analysis of Right-Wing Populist Rhetoric in Election Campaigns’, Argumentation, 33:1, 107–36.

- Bobba, Giuliano (2019). ‘Social Media Populism: Features and “Likeability” of Lega Nord Communication on Facebook’, European Political Science, 18:1, 11–23.

- Bøggild, Troels, and Helene Helboe Pedersen (2018). ‘Campaigning on behalf of the Party? Party Constraints on Candidate Campaign Personalisation’, European Journal of Political Research, 57:4, 883–99.

- Boyadjian, Julien (2015). ‘Chapitre 6/Les Usages Frontistes du Web’, in Sylvain Crépon, Alexandre Dezé, and Nonna Mayer (eds.), Les faux-semblants du Front national: Sociologie d’un parti politique. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, 141–160. (accessed 22 September 2022).

- Boyadjian, Julien (2016). ‘Les Uages Politiques Différenciés de Twitter: Esquisse d’une Typologie des Twittos Politiques’, Politiques de communication, 6:1, 31–58.

- Bracciale, Roberta, Massimiliano Andretta, and Antonio Martella (2021). ‘Does Populism Go Viral? How Italian Leaders Engage Citizens through Social Media’, Information, Communication & Society, 24:10, 1477–94.

- Brown, Alexander (2017). ‘What is Hate Speech? Part 1: The Myth of Hate’, Law and Philosophy, 36:4, 419–68.

- Caiani, Manuela, Benedetta Carlotti, and Enrico Padoan (2021). ‘Online Hate Speech and the Radical Right in Times of Pandemic: The Italian and English Cases’, Javnost – The Public, 28:2, 202–18.

- Calderón, Carlos Arcila, Gonzalo de la Vega, and David Blanco Herrero (2020). ‘Topic Modeling and Characterization of Hate Speech against Immigrants on Twitter around the Emergence of a Far-Right Party in Spain’, Social Sciences, 9:11, 188.

- Cohen-Almagor, Raphael (2011). ‘Fighting Hate and Bigotry on the Internet’, Policy & Internet, 3:3, 1–26.

- Connolly, William E. (1993). The Terms of Political Discourse. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Conrad, Maximilian, Guðmundur Hálfdanarson, Asimina Michailidou, Charlotte Galpin, and Niko Pyrhönen, eds. (2023). Europe in the Age of Post-Truth Politics: Populism, Disinformation and the Public Sphere. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Degani, Marta (2015). Framing the Rhetoric of a Leader: An Analysis of Obama’s Election Campaign Speeches. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dézé, Alexandre (2013). ‘De Quelques Idées Reçues sur la “Dédiabolisation” et le “Populisme” du Front National’, Revue Espaces Marx, 34, 45–54.

- Dézé, Alexandre (2015). ‘Chapitre 1/La « Dédiabolisation ». Une Nouvelle Stratégie?’, in Sylvain Crépon, Alexandre Dezé, and Nonna Mayer (eds.), Les faux-semblants du Front national: Sociologie d’un parti politique. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, 25–50. (accessed 15 November 2022).

- Doroshenko, Larisa, Tetyana Schneider, Dmitrii Kofanov, Michael A. Xenos, Dietram A. Scheufele, and Dominique Brossard (2019). ‘Ukrainian Nationalist Parties and Connective Action: An Analysis of Electoral Campaigning and Social Media Sentiments’, Information, Communication & Society, 22:10, 1376–95.

- Druckman, James N., Martin J. Kifer, and Michael Parkin (2020). ‘Campaign Rhetoric and the Incumbency Advantage’, American Politics Research, 48:1, 22–43.

- Durovic, Anja (2023). ‘Rising Electoral Fragmentation and Abstention: The French Elections of 2022’, West European Politics, 46:3, 614–29.

- Eder, Nikolaus, Marcelo Jenny, and Wolfgang C. Müller (2017). ‘Manifesto Functions: How Party Candidates View and Use Their Party’s Central Policy Document’, Electoral Studies, 45, 75–87.

- Elmelund-Præstekær, Christian, and Helle Mølgaard Svensson (2014). ‘Ebbs and Flows of Negative Campaigning: A Longitudinal Study of the Influence of Contextual Factors on Danish Campaign Rhetoric’, European Journal of Communication, 29:2, 230–9.

- Enli, Gunn Sara, and Eli Skogerbø (2013). ‘Personalised Campaigns in Party-Centred Politics: Twitter and Facebook as Arenas for Political Communication’, Information, Communication & Society, 16:5, 757–74.

- Evolvi, Giulia (2023). ‘Europe is Christian, or It is Not Europe: Post-Truth Politics and Religion in Matteo Salvini’s Tweets’, in Maximilian Conrad, Guðmundur Hálfdanarson, Asimina Michailidou, Charlotte Galpin, and Niko Pyrhönen (eds.), Europe in the Age of Post-Truth Politics. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 129–48.

- Facchini, François, and Louis Jaeck (2021). ‘Populism and the Rational Choice Model: The Case of the French National Front’, Rationality and Society, 33:2, 196–228.

- Frame, Alex, and Gilles Brachotte (2015). ‘Le Tweet Stratégique: Use of Twitter as a PR Tool by French Politicians’, Public Relations Review, 41:2, 278–87.

- Froio, Caterina (2017). ‘Nous et les Autres: L’Altérité sur les Sites Web des Extrêmes Droites en France’, Réseaux, n° 202–203:2, 39–78.

- Froio, Caterina (2018). ‘Race, Religion, or Culture? Framing Islam between Racism and Neo-Racism in the Online Network of the French Far Right’, Perspectives on Politics, 16:3, 696–709.

- Guldemond, Puck, Andreu Casas Salleras, and Mariken Van der Velden (2022). ‘Fueling Toxicity? Studying Deceitful Opinion Leaders and Behavioral Changes of Their Followers’, Politics and Governance, 10:4, 336–348.

- Haselmayer, Martin (2019). ‘Negative Campaigning and Its Consequences: A Review and a Look Ahead’, French Politics, 17:3, 355–72.

- Hobeika, Alexandre, and Gaël Villeneuve (2017). ‘Une Communication par les Marges du Parti?: Les Groupes Facebook Proches du Front National’, Réseaux, n° 202–203:2, 213–40.

- Ivaldi, Gilles (2015). ‘Chapitre 7/Du Néolibéralisme au Social-Populisme? La transformation du Programme Économique du Front National (1986–2012)’, in Sylvain Crépon, Alexandre Dezé, and Nonna Mayer (eds.), Les faux-semblants du Front national: Sociologie d’un parti politique. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, 161–84. (accessed 22 September 2022).

- Jakob, Julia, Timo Dobbrick, Rainer Freudenthaler, Patrik Haffner, and Hartmut Wessler (2023). ‘Is Constructive Engagement Online a Lost Cause? Toxic Outrage in Online User Comments across Democratic Political Systems and Discussion Arenas’, Communication Research, 50:4, 508–31.

- Jungherr, Andreas (2016). ‘Twitter Use in Election Campaigns: A Systematic Literature Review’, Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13:1, 72–91.

- Kim, Jin Woo., Andrew Guess, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler (2021). ‘The Distorting Prism of Social Media: How Self-Selection and Exposure to Incivility Fuel Online Comment Toxicity’, Journal of Communication, 71:6, 922–46.

- Klein, Ofra, and Jasper Muis (2019). ‘Online Discontent: Comparing Western European Far-Right Groups on Facebook’, European Societies, 21:4, 540–62.

- Koedam, Jelle (2021). ‘Avoidance, Ambiguity, Alternation: Position Blurring Strategies in Multidimensional Party Competition’, European Union Politics, 22:4, 655–75.

- Lau, Richard R., and Gerald M. Pomper (2002). ‘Effectiveness of Negative Campaigning in U.S. Senate Elections’, American Journal of Political Science, 46:1, 47.

- Lau, Richard R., and Ivy Brown Rovner (2009). ‘Negative Campaigning’, Annual Review of Political Science, 12:1, 285–306.

- Leconte, Cécile (2020). ‘Dire le Genre à l’Extrême Droite en Allemagne et France: Une Étude Comparée des Techniques de Présentation de Soi de Marine Le Pen (FN) et Frauke Petry (AfD)’, Revue internationale de politique comparée, 27:1, 7–41.

- Lees, Alyssa (2022). ‘A New Generation of Perspective API: Efficient Multilingual Character-Level Transformers’, in Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Washington, DC: ACM, 3197–3207 10.1145/3534678.3539147 (Accessed July 28, 2023).

- Leite, João A., Diego F. Silva, Kalina Bontcheva, and Carolina Scarton (2020). ‘Toxic Language Detection in Social Media for Brazilian Portuguese: New Dataset and Multilingual Analysis’, available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.04543 (accessed 14 July 2023).

- Mai, Philipp, and Georg Wenzelburger (2023). ‘Loyal Activists? Party Socialization and Dissenting Voting Behavior in Parliament’, Legislative Studies Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12416

- Marland, Alex, and Angelia Wagner (2020). ‘Scripted Messengers: How Party Discipline and Branding Turn Election Candidates and Legislators into Brand Ambassadors’, Journal of Political Marketing, 19:1–2, 54–73.

- Mattes, Kyle, and David P. Redlawsk (2015). The Positive Case for Negative Campaigning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Mayer, Nonna (2022). ‘The Impact of Gender on Votes for the Populist Radical Rights: Marine Le Pen vs. Eric Zemmour’, Modern & Contemporary France, 30:4, 445–60.

- Mosleh, Mohsen, Cameron Martel, Dean Eckles, and David Rand (2021). ‘Perverse Downstream Consequences of Debunking: Being Corrected by Another User for Posting False Political News Increases Subsequent Sharing of Low Quality, Partisan, and Toxic Content in a Twitter Field Experiment’, in Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Yokohama Japan: ACM, 1–13. 10.1145/3411764.3445642 (accessed 14 July 2023).

- Nai, Alessandro (2020). ‘Going Negative, Worldwide: Towards a General Understanding of Determinants and Targets of Negative Campaigning’, Government and Opposition, 55:3, 430–55.

- Nai, Alessandro, and Jurgen Maier (2020). ‘Is Negative Campaigning a Matter of Taste? Political Attacks, Incivility, and the Moderating Role of Individual Differences’, American Politics Research, 49:3, 269–81.

- Nai, Alessandro, and Annemarie Walter (2015). New Perspectives on Negative Campaigning: Why Attack Politics Matters. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Navera, Gene Segarra (2021). ‘The President as Macho: Machismo, Misogyny, and the Language of Toxic Masculinity in Philippine Presidential Discourse’, in Ofer Feldman (ed.), When Politicians Talk: The Cultural Dynamics of Public Speaking. Singapore: Springer, 187–202.

- Nithyashree, V., et al. (2022). ‘Identification of Toxicity in Multimedia Messages for Controlling Cyberbullying on Social Media by Natural Language Processing’, in 2022 International Conference on Distributed Computing, VLSI, Electrical Circuits and Robotics (DISCOVER), Shivamogga, India, 12–18.

- Obholzer, Lukas, and William T. Daniel (2016). ‘An Online Electoral Connection? How Electoral Systems Condition Representatives’ Social Media Use’, European Union Politics, 17:3, 387–407.

- Perspective API (2023). About the API – Attributes and Languages, available at: https://developers.perspectiveapi.com/s/about-the-api-attributes-and-languages?language=en_US (accessed 31 March 2023).

- Pla, Ferran, and Lluís-F Hurtado (2018). ‘Spanish Sentiment Analysis in Twitter at the TASS Workshop’, Language Resources and Evaluation, 52:2, 645–72.

- Radfar, Bahar, Karthik Shivaram, and Aron Culotta (2020). ‘Characterizing Variation in Toxic Language by Social Context’, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 14:1, 959–63.

- Rajadesingan, Ashwin, Ceren Budak, and Paul Resnick (2021). ‘Political Discussion is Abundant in Non-Political Subreddits (and Less Toxic)’, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 15:1, 525–36.

- Rehmert, Jochen (2022). ‘Party Membership, Pre-Parliamentary Socialization and Party Cohesion’, Party Politics, 28:6, 1081–93.

- Rieder, Bernhard, and Yarden Skop (2021). ‘The Fabrics of Machine Moderation: Studying the Technical, Normative, and Organizational Structure of Perspective API’, Big Data & Society, 8:2. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211046181

- Rovny, Jan (2012). ‘Who Emphasizes and Who Blurs? Party Strategies in Multidimensional Competition’, European Union Politics, 13:2, 269–92.

- Rovny, Jan (2013). ‘Where Do Radical Right Parties Stand? Position Blurring in Multidimensional Competition’, European Political Science Review, 5:1, 1–26.

- Sakki, Inari, and Katarina Pettersson (2016). ‘Discursive Constructions of Otherness in Populist Radical Right Political Blogs: Discursive Constructions of Otherness’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 46:2, 156–70.

- Schwörer, Jakob, and Belén Fernández-García (2021). ‘Demonisation of Political Discourses? How Mainstream Parties Talk about the Populist Radical Right’, West European Politics, 44:7, 1401–24.

- Seethaler, Josef, and Gabriele Melischek (2019). ‘Twitter as a Tool for Agenda Building in Election Campaigns? The Case of Austria’, Journalism, 20:8, 1087–107.

- Startin, Nicholas (2022). ‘Marine Le Pen, the Rassemblement National and Breaking the “Glass Ceiling”? The 2022 French Presidential and Parliamentary Elections’, Modern & Contemporary France, 30:4, 427–43.

- Theviot, Anaïs (2013). ‘Qui Milite sur Internet? Esquisse du Profil Sociologique du « Cyber-Militant » au PS et à l’UMP’, Revue française de science politique, 63:3, 663–78.

- Vergeer, Maurice (2015). ‘Twitter and Political Campaigning’, Sociology Compass, 9:9, 745–60.

- Walsh, James P. (2023). ‘Digital Nativism: Twitter, Migration Discourse and the 2019 Election’, New Media & Society, 25:10, 2618–43.

- Yan, Xiaohui, Jiafeng Guo, Yanyan Lan, and Xueqi Cheng (2013). ‘A Biterm Topic Short Texts’, in Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW ‘13. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 1445–1456 (accessed 7 June 2023).

- Zulianello, Mattia, and Erik Gahner Larsen (2023). ‘Blurred Positions: The Ideological Ambiguity of Valence Populist Parties’, Party Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231161205