?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The second-order election (SOE) model expects voters to punish parties in national government and reward opposition, small and new parties because there is ‘less at stake’ in an SOE. One key assumption that is rarely studied is whether SOE-effects depend on the extent to which voters can impact the selection of the executive in an SOE. This article argues that executive autonomy – i.e. the extent to which executives are independent from the parliament regarding their formation, termination and execution of their competences – increases the impact of authority. Executive autonomy reduces SOE-effects when authority is high but increases SOE-effects when authority is low. An empirical analysis of 41,603 vote share swings for 4733 parties competing in 2665 elections held in 282 regions in 14 European countries between 1945 and 2019 confirms the hypotheses. These results have important implications for electoral democracy and party competition at the regional, national and European level.

The second-order election (SOE) model features prominently in research on European, sub-national and various other types of non-national elections. A stake-based approach underlies the SOE-model which assumes that non-national elections are conceived by voters and parties as less important than first-order, national elections. As a result, voters use an SOE to voice their opinion about national politics by voting against the parties in national government and, instead, support small, new and opposition parties. The literature has suggested two main causes for why the stakes are perceived to be lower in non-national elections. The first cause focuses on the issues at stake in an SOE. Important issues such as international relations, defence and major taxes are the competence of national governments and are often not decided by supra- and sub-national governments. The growing authority for the European Parliament and regional governments therefore features prominently in studies that explore whether an increase in supra- and sub-national authority reduces SOE-effects (Hix and Marsh Citation2007, Citation2011; Hough and Jeffery Citation2006; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013).

A second theorised cause for why non-national elections can become second-order is when voters do not have a possibility to impact the choice of an executive when casting their vote in an SOE (Marsh and Mikhaylov Citation2010; Reif and Schmitt Citation1980). This hypothesis has not been theoretically fleshed out nor been subject to much comparative empirical research because there is only one EU and the possibility for voters to impact the selection of the executive at the European level has not fundamentally changed over time. At the subnational level, limited data availability for elections and parliament–executive relations prevented an empirical test of this hypothesis.

We develop a theory on the conditions under which the choice of an executive impacts on SOE-voting. Voters can use their vote in an SOE in three ways: to select an executive, to punish national incumbents, or to voice their preferences regarding policies that fall under the jurisdiction of the SOE-arena. We argue that executive autonomy—i.e. the extent to which executives are independent from the parliament regarding their formation, termination and execution of their competences—captures both the opportunity and importance for voters to select the executive. Voters have a larger impact on the choice of an executive when, for example, an executive is delivered by the largest party that receives an absolute majority of seats because of a seat bonus and when the winning list is headed by a presidential candidate who, once elected, will appoint the other members of the executive. Voters should care more about impacting the selection of an executive when there is a single head who bears the main responsibility for executive policy and when an executive cannot be ousted by a parliament once an executive has been formed.

We theorise further that the impact of executive autonomy depends on the authority exercised by the SOE-arena. Executive autonomy reduces SOE-effects when authority is high, but increases SOE-effects when authority is low. Selecting the executive becomes more important when executives have more authority and are less dependent on the parliament in the exercise of their competences. Executive positions are more attractive and easier to win for new, opposition and small parties when executives are autonomous and authority is low which induces voters to use an SOE to express their discontent with national incumbents.

In this article, we exploit a unique dataset that includes 41,603 party vote share swings incurred by 4733 parties competing in 2665 regional elections held between 1945 and 2019 in 282 regions in 14 European countries. Parliament–executive relations vary widely across regions in Europe which provides for a unique testing ground to study whether and how SOE-effects depend on executive autonomy. To test our hypotheses, we develop an innovative indicator on executive autonomy consisting of nine indicators tapping into parliament–executive relations in regions and we employ the Regional Authority Index (RAI) which provides regional-level authority scores on an annual basis (Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021).

The results confirm our hypotheses. Although parties in national government are relatively unaffected—i.e. they lose vote share no matter whether executive autonomy is high or low—which party benefits from the government party loss is highly dependent on executive autonomy. Opposition and no-seat parties—i.e. parties that participated in a national election but did not win a seat in the national parliament—win vote share when both executive autonomy and regional authority are low, but new parties win vote share when executive autonomy is high but regional authority is low. Importantly, we find that self-rule—the authority exercised by a region within its jurisdiction—reduces losses incurred by government parties whereas shared rule—the authority exercised by regions together with other regions and the central government—advantages opposition parties.

These results have important implications for the design of sub- and supra-national electoral democracy. A significant decentralisation trend since the 1970s has introduced regional elections and empowered regions across Europe (Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Loughlin et al. Citation2011). There is a widely supported democratic norm that voters should be able to express their policy preferences and be able to hold executives accountable in their regions (Council of Europe Citation1985; OECD Citation2019; Treisman Citation2007). Our results reveal that the extent to which voters are able and willing to do so is highly dependent on the ways in which executive autonomy is combined with regional authority and whether regions exercise only self-rule or both self-rule and shared rule. An often-raised solution to remedy the ‘democratic deficit’ of the European Union is to strengthen the link between a vote cast in European Parliament elections and the choice of the President of the European Commission (Christiansen Citation2016; Hix Citation2002; Hobolt Citation2014). Our results strongly suggest that this kind of reform will significantly reduce SOE-effects.

In the next section we discuss the SOE-model and we will reveal that one of the underlying assumptions—i.e. the selection of an executive is not at stake—has rarely been subject to empirical analysis. We then proceed with a conceptual exploration on how executive autonomy varies across different parliament–executive regimes and we argue that executive autonomy increases the perceived ‘stakes’ in an SOE. In the fourth section, we hypothesise that executive autonomy reinforces the impact of authority: executive autonomy increases SOE-effects when regional authority is low but reduces SOE-effects when regional authority is high. Variables, data and methods are discussed in the fifth section and the results are discussed in sixth section. The final section presents the conclusion and discussion.

What is ‘at stake’ in an election and second-order election effects

The second-order election (SOE) model was introduced by Reif and Schmitt (Citation1980) in their seminal article analysing the first direct election to the European parliament in 1979. Their central premise is that voters behave differently in second-order elections (SOEs) because they are often perceived to be less important than national, first-order elections (FOEs). There are three main expectations when SOE outcomes are compared to FOE results (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980: 9–10). The first, and most studied, expectation is that ‘government parties lose’. Vote share losses are largest when an SOE is held at mid-term of the national election cycle, and they are smallest when an SOE is held closely after a previously held or just before an upcoming national election. This cyclical effect is closely connected to the declining and rising popularity of national governments in between national elections which, in turn, can be attributed to voters who have become disappointed by specific policies of the government and who are more easily to mobilise to turn out because they want to signal their dissatisfaction.

Second, SOEs are marked by ‘lower levels of participation’ and a ‘higher percentage of invalidated ballots’. When there is less at stake in an election, fewer voters may consider them sufficiently important to cast a ballot. Voters who bother to turn out and vote may be more inclined to invalidate their ballot in case they are displeased with the parties on offer on the ballot paper. More consequential for the vote is that dissatisfied voters are more likely to turn out in SOEs in comparison to satisfied voters (Lau Citation1985). As a result, the share of voters who are inclined to cast a vote against a government party increases when turnout decreases.Footnote1

Third, SOEs offer ‘brighter prospects for small and new political parties’. These parties tend to do well in SOEs because they attract the ‘protest vote’ or because voters tend to return to casting a sincere vote after having voted strategically in the first-order, national election. Large and electorally decisive parties may receive votes in FOEs from voters whose actual preference lies with a small or new party. When the stakes of an election increase, a voter may support a larger party which has more chances to enter national government and to change national policy in the direction of the preferred views of the voter. A small or new party may better represent a voter’s opinion but often has a lower chance to be included in national government.

The merit of the SOE-model has been shown for a wide range of different types of SOEs such as local, regional and European elections, elections to an upper chamber of parliament and by-elections. In addition, many studies have explored the contextual conditions which impact the magnitude of SOE effects either through a hypothesised impact on voter dissatisfaction with the performance of national governments—e.g. when there is economic decline and unemployment is high—or because they increase the perceived stakes in an election—e.g. when strong sub-/supra-national identities induce voters to care about the issues at stake in an SOE (Cabeza Citation2018; Carrubba and Timpone Citation2005; Clark and Rohrschneider Citation2009; Cutler Citation2008; Golder et al. Citation2017; Heath et al. Citation1999; Schakel Citation2015). An important and relatively well studied conditional factor concerns authority. Often instigated by Reif and Schmitt’s (Citation1980: 9) remark that ‘Perhaps the most important aspect of second-order elections is that there is less at stake’, a number of studies have explored whether SOE-effects are smaller in SOE-jurisdictions which exercise more authority. Increasing competences for the European Parliament (EP) through subsequent Treaty reforms should have made European elections more relevant to voters. Voters are more inclined to base their vote choice on issue positions of subnational parties and candidates when subnational governments have more authority (Dandoy and Schakel Citation2013; Hix and Marsh Citation2007, Citation2011; Hough and Jeffery Citation2006; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013; Schmitt Citation2005).

However, Reif and Schmitt (Citation1980: 12, italics added) also expected to find strong SOE-effects because ‘All the arguments of our “less-at-stake”-dimension … are all the more relevant, because no institutions that assumes the role of political leadership of the European Community is at stake in EP-elections.’ However, very few studies have explored whether SOE-effects reduce when voters do have an opportunity to impact the choice of the executive.Footnote2 This lack of attention is surprising considering that not being able to impact the choice of an executive is often considered to be a key element of the ‘democratic deficit’ in the European Union (Christiansen Citation2016; Hix Citation2002, Citation2008; Hobolt Citation2014).Footnote3 In the next section, we argue that executive autonomy increases the (perceived) stakes in an SOE by increasing both the opportunity and importance of selecting an executive.

Executive autonomy: opportunities and importance for voters to select the executive

In electoral democracies, there are two main ways in which voters determine who gains control over legislative and executive powers: presidential and parliamentary systems (Hague and Harrop Citation2001: 218–53; Lijphart Citation1999). In presidential systems, both the parliament and the executive are directly elected by voters, often in separate elections. In parliamentary systems, the executive and legislature derive their authority from the same election and executives are formed and terminated by (majorities in) the legislatures. Voters can directly impact the choice of an executive in presidential systems where citizens vote for candidates who compete for a single office whereas their impact is indirect in parliamentary systems where the selection of executives depends on which parties in the legislature are willing to form a majority to support a government. The importance of selecting the executive is higher in presidential systems because presidents are less dependent on the parliament than executives in a parliamentary system—except when there is one party with an absolute majority of parliamentary seats that forms the executive, e.g. in a Westminster system (Lijphart Citation1999; Tsebelis Citation1995).

We argue that executive autonomy—the extent to which executives regarding their formation, termination and exercise of their competences are independent from the parliament—captures both the opportunities and the importance for voters to select the executive in an election. Executives are autonomous when they are directly elected by citizens, they cannot be intermediately terminated by early elections or by the parliament, their powers are concentrated in a single office, and they can decide and implement policy independently from the legislature. Executive autonomy varies widely across parliament–executive regimes. Executive power is directly at stake in presidential systems and the stakes increase further to the extent that presidents can exercise their powers without being dependent on the parliament. In parliamentary systems, the executive is formed and terminated by one or more parties in the legislature that can muster majority support in parliament. Executives are relatively less autonomous because their formation and survival is dependent on parliamentary support.

Some parliamentary systems apply a seat bonus to ensure that a single party (list) gains an (absolute) majority in the parliament and can select the executive without a need to form alliances with other parties in the legislature.Footnote4 A voter can almost directly impact the choice of the executive and the selection of the executive is important because single-party majority support makes the executive less dependent on the parliament. There are also parliamentary systems—often present in consociational democracies—which have a collegial executive where a fixed formula determines which parties can provide members for the executive (Lijphart Citation1999; Vatter Citation2016). A party will gain representation in both the legislature and the executive once it exceeds an electoral and seat threshold. The choice of the executive is not at stake and is also not important because voters should be mostly concerned with who will be represented in the parliament considering that parties have almost full control over their member in the executive.

To summarise, we argue that executive autonomy increases the (perceived) stakes in SOEs because it increases the possibility and the importance for voters to select the executive. The (perceived) stakes in an SOE also depend on authority and in the next section we will theoretically explore the interaction effects between executive autonomy and authority.

The impact of executive autonomy and authority on second-order election effects

Voters have three options in an SOE: they can use their vote (1) to express their discontent about national politics, (2) to voice their preferences regarding policies that fall under the competence of the SOE-arena, or (3) to impact the choice of an executive in the SOE-arena. Voters’ inclination to use their SOE-vote in a particular way depends on the authority and executive autonomy of the SOE-arena. We adopt a generally upheld assumption in the literature which expects SOE-effects to decline when authority increases because there are more issues at stake in an election that voters care about. Instead of using their vote to express (dis)content with parties in national government, voters are more inclined to base their vote choice on the positions adopted by parties regarding the issues at stake in an election (Hough and Jeffery Citation2006; Maddens and Libbrecht Citation2009; Thorlakson Citation2007, Citation2009). Therefore, one may expect SOE-effects to arise when authority is low (cells A and B in ) but SOE-effects should be smaller when authority is high (cells B and D).

Table 1. Hypothesised impacts of executive autonomy and authority on second-order election effects.

Hypothesis 1: Regional authority decreases second-order election effects.

Our main theoretical contribution is to hypothesise that executive autonomy strengthens the impact of authority. Executive autonomy increases the stakes of an election further when authority is high. Executives often control the agenda, they are more likely to have sufficient expertise and resources to draft policy, and they have responsibility for implementing policy (Arter Citation2006; Lijphart Citation1999; Martin and Vanberg Citation2011). Hence, selecting the executive becomes more important when the competences and policy scope of an SOE-arena widen and deepen. Decentralisation increases the likelihood that voters vote according to their assessment of the performance by the SOE-government (Léon Citation2011; Léon and Orriols 2016). Voters may find it easier to attribute responsibility for regional policy performance when powers within the executive are concentrated in a single-headed office which is won by a presidential candidate on a list supported by one or few parties (Anderson Citation2000; Lewis-Beck and Nadeau Citation2000). Furthermore, parties and candidates have strong incentives to mobilise voters to vote for them when the ‘prize’ of winning office is large which also helps parties to mobilise voters differently across electoral arenas (Chhibber and Kollman Citation2004). As a result, SOE-effects should decrease further when authority and executive autonomy are both high because both voters and parties are concerned about who will win regional executive office (cell D in ).

Hypothesis 2: Executive autonomy decreases second-order election effects when regional authority is high.

Voters are less interested in using their vote to express their preference regarding regional policy when decentralisation is limited. When authority is low, there are less policies at stake and voters can be more easily persuaded to vote for a new, opposition or small party to express their discontent with national incumbents. Additionally, power sharing within the executive through shared responsibilities between executive members may decrease the clarity of responsibility for regional policy performance (Lewis-Beck Citation1997). Holding representatives accountable is more difficult in consociational systems where each party that is sufficiently represented in the parliament appoints a member of the executive (Bingham Powell and Whitten Citation1993). Parties and candidates have more incentives to capitalise on discontent voters when winning executive office is more attractive which is largely dependent on executive autonomy (Martin Citation2016; Tavits Citation2008). The depth and scope of the competences associated with holding executive office may be relatively limited, but executives can fully control these competences to the extent they can act autonomously from the parliament. Therefore, we expect SOE-effects to increase when authority is low but executive autonomy is high (cell C in ).

Hypothesis 3: Executive autonomy increases second-order election effects when regional authority is low.

Regions in Europe provide for an ideal testing ground to explore whether and under which conditions executive autonomy reduce SOE-effects. European regions have adopted various regimes of parliament-executive relations and executive autonomy varies widely (see below). In addition, the magnitude of SOE-effects differs extensively between regions and countries and over time (Dandoy and Schakel Citation2013; Hough and Jeffery Citation2006; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013). Furthermore, regional authority differs substantially between regions within and between countries (Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021).

Variables, data and methods

The main dependent variable concerns a party vote share swing which is operationalised as the difference between a party vote share won in a regional election and its vote share won in the same region in a previously held national election. A positive swing indicates that a party’s regional election vote share is higher than its vote share in the previously held national election. We compare 2665 regional elections held in 282 regions in 14 West European countries between 1945 and 2019 to a previously held national election (). A unique feature of our dataset is that we include all parties that won at least one vote in either a regional or a previously held national election and we are able to analyse a total of 41,603 vote share swings for 4733 parties.

Table 2. Included countries, regions and regional and national elections.

In order to assess SOE-effects we differentiate between four mutually exclusive and exhaustive party categories. A party is classified as either a government, opposition, no-seat, or new party. A government party is represented in the executive government at the national level whereas an opposition party is represented in the national parliament but does not provide a member of the executive. Data on the composition of national executives and parliaments is obtained from the ParlGov dataset (Döring et al. Citation2022).Footnote5 The remaining parties that competed in a previously held national election are parties that did not win a seat in the national parliament and therefore we label them no-seat parties (Schakel Citation2015). A new party did not compete in a previously held national election but wins votes in a regional election.Footnote6

Our dataset includes the results for parliamentary elections because independently elected executives are rare among Western European regions and exist only in London, in 13 out of 22 Italian regions since 1999 and in Swiss cantons. Except for London (with only five elections), the parliamentarian vote is, in practice, often connected to the executive vote.Footnote7

We present a new and innovative indicator for executive autonomy (Regional Executive Autonomy Index) in 282 regions in 14 European countries for 1945–2019. presents nine indicators which measure a different dimension of executive autonomy. The Cronbach’s alpha of the nine indicators is 0.89 and a principal component analysis with nonlinear optimal scaling transformations for ordinal variables (Meulman et al. Citation2004) on 490 regional parliament–executive regimesFootnote8 reveals one dimension with an eigenvalue of 4.8 which explains 53% of the variation in scores (Online Appendix Table A1). Factor loadings of the indicators are 0.6 or above except for ‘mode of dissolution of parliament’ which has a factor loading of 0.4.Footnote9 More information on the Regional Executive Autonomy Index is provided in Online Appendix A.

Table 3. Regional Executive Autonomy Index (REAI) indicators.

We derive regional executive autonomy scores by summing the scores on the nine indicators. The key reasoning behind the operationalisation of the indicators is that higher scores indicate more autonomous and powerful executives. An executive is more autonomous when it is elected or appointed by an actor outside the parliament which also gives it external legitimacy especially when the head or all the members are directly elected by citizens. Executives can act more autonomously from the parliament when they cannot be ousted by the parliament or when the parliament faces institutional hurdles before it can oust an executive. In addition, executive dominance over the parliament significantly increases when executive members keep their seat in parliament, when the executive can (automatically) rely on a majority in the parliament through a seat bonus, or when the executive head chairs the parliament and/or important parliamentary committees. Finally, executives are more autonomous when they are chaired by a president who does not have to share competences with other members of the executive.

Higher scores on the Regional Executive Autonomy Index sub-indicators also tap the opportunities and importance for voters to select the executive. Voters have more opportunities to select an executive when they can directly elect the head or all members of the executive, or when the winning party list receives a seat bonus and is headed by a lead candidate who will ‘automatically’ assume presidential office. Opportunities to impact the selection of an executive are more limited when parties or parliaments select and appoint executive members after an election has taken place. Impacting the selection of executives becomes more important for voters when the executive gains dominance over parliament and when the executive head becomes more powerful. Both dimensions are gauged by all the nine sub-indicators as explained above.

Austrian Länder receive the minimum score of zero whereas the Greek regions receive the highest observed score of 8.67. Several Länder in Austria apply consociational rules and all parties in the parliament whose seat share crosses a certain threshold have leverage over the executive. Members of the executive are highly dependent for their election and survival on their nominating party in the parliament. Each party that is represented in the parliament elects a (junior) member of the executive and the head of the executive is elected by the party with the largest seat share. The executive is collegial, has no formal influence over parliamentary affairs and cannot call for early elections, while the parliament can. In stark contrast, executive power of Greek nomoi (1994–2006) and periphereia (2010–2014) is concentrated in the governor who heads a party list that receives a seat bonus which secures an absolute majority in the parliament. The governor chairs the parliament as well as the financial committee of the parliament and the parliament cannot revoke the governor.

Italian and French regions receive regional executive autonomy scores, respectively 2.58 and 5.33, that fall in between these extremes. The executive (giunta) in Italian regioni a statuto ordinario (1970–1994) was a collegial body where each of the members was elected by and from the members in the parliament. The executive could not dissolve the parliament, but the parliament could oust any member of the executive by adopting a vote of no confidence. The executive (commission permanente) in French régions (2004–2015; not including Corsica) consists of a president who chairs the parliament and who is solely responsible for executive powers. Party lists in regional elections are headed by presidential candidates and the winning list receives a seat bonus of 25%. The president is elected by and from the members of parliament at the start of a term and the parliament cannot be dissolved and the president cannot be ousted.

Our second main independent variable is regional authority and the Regional Authority Index (RAI) provides annual scores for the regions and time periods mentioned in (Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, the RAI provides for separate scores for self-rule—authority exercised by regions within their jurisdictions—and shared rule—authority exercised by regions in the country as a whole and together with other regions and the national government. Self-rule and shared rule scores vary between 7 and 18 for self-rule and between 0 and 12 for shared rule (see Online Appendix Tables A2a and A2b).

Regional election research has found different impacts of self-rule and shared rule. Both reduce SOE-effects, but self-rule benefits regional(ist) parties which are often classified as small or new parties in the SOE-model. Shared rule advantages opposition parties because voters may seek to balance government at the statewide level (Carrubba and Timpone Citation2005; Erikson Citation1988; Lau Citation1985; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013). For example, some voters cast a vote for a left-wing opposition party in the SOE-election to balance out a right-wing government at the statewide level. The ability for a left-wing opposition party in regional government to impact national policy is larger when there is shared rule, either through regional representation in an upper chamber of national parliament or through intergovernmental meetings between regional and national executives. Hence, in addition to interacting executive autonomy with regional authority we also explore the interactions between executive autonomy and regional self-rule and shared rule.

We introduce several control variables at the party, region and election level. All data, except for two variables, are based on original data collection. At the party level we include size which is operationalised as the regional vote share won in the previous national election. We also include size squared (size2) and size cubed (size3) to account for a cubic effect of party size on party performance (Hix and Marsh Citation2007, Citation2011; Marsh Citation1998). Voters may punish parties for their performance in regional government and we include a dummy variable (in regional government) indicating whether a party is part of executive government in the region at the time of the regional election. Second-order election effects can only be assessed when the party systems in first- and second-order electoral arena are similar (Marsh and Mikhaylov Citation2010: 8). Some parties that compete in national elections may not field a list in regional elections or may field lists in some but not in other regions.Footnote10 We include the variable no list which is the vote share swing for a party that competed in the previously held national election but not in the regional election. No list scores zero in all other instances.

Four control variables vary mostly or only at the region level. Region size is the proportion of the regional electorate relative to the statewide electorate for regional elections. We also include a language region dummy variable which scores positive when a majority of the population speaks a different language than the dominant national language (Hooghe and Marks Citation2016; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021). Regional and national electoral systems differ and we include the average district magnitude (in the first tier) for both regional (ADM regional) and national elections (ADM national). Data for national elections is obtained from the Democratic Electoral Systems (DES) dataset (Bormann and Golder Citation2022). In addition, we control for the size of the national and regional party systems by including the effective number of parliamentary parties in the regional (ENPP regional) and national (ENPP national) electoral arenas.

Numerous studies have shown important effects of electoral timing of the SOE in relation to the FOE, other SOEs and other types of elections (Hix and Marsh Citation2011; Schakel Citation2017; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013). We introduce the variables cycle and cycle2 (cycle squared) to trace the impact of the placement of the regional election in the national election cycle. The variable cycle scores 0.5 at mid-term of the national election cycle and 1 at the end of the national election cycle which, depending on the country, lasts for 3, 4, or 5 years. Simultaneously held regional and national elections score 1 on cycle and cycle2. The impact of the timing of the regional election relative to other elections is captured by an electoral regime variable which differentiates between six regimes (Schakel and Dandoy Citation2014): (1) independently scheduled, (2) simultaneity with local elections within the region, statewide simultaneity between (3) regional, (4) regional and local, (5) regional and national, or (6) regional, local and national elections. A dummy variable traces when a regional election is held simultaneous with another type of election such as a presidential or European Parliament election (simultaneity other).

Finally, we include a dummy variable with positive scores when a regional election is held for the first time (first election) and we include election year to account for possible trends in vote share swings. Descriptive statistics for all the variables are provided in Online Appendix B. The main core of our model is as follows:

Whereby vote share swings for a party i are incurred in election j. To account for the clustering of vote share swings we employ multilevel regression models with random effects for election years, regions and countries. Our first model explores the direct effects of executive autonomy and regional authority (RAI) and to trace SOE-effects we interact these variables with four party types: government, opposition, no-seat and new parties (see above). We add a three-way interaction effect between executive autonomy, regional authority and party type to assess our hypotheses on whether SOE-effects are increased by executive autonomy when authority is low but are decreased when authority is high (). We explore the impact of self-rule and shared rule by rerunning the model with self-rule and shared rule scores plus their interactions with executive autonomy and party type (Online Appendix Table B2). All the models include the control variables at the party, election and region level discussed above as well as the interactions between these control variables and party type. In total our models include 20 variables and 16 interactions with party type (Online Appendix B).

Results

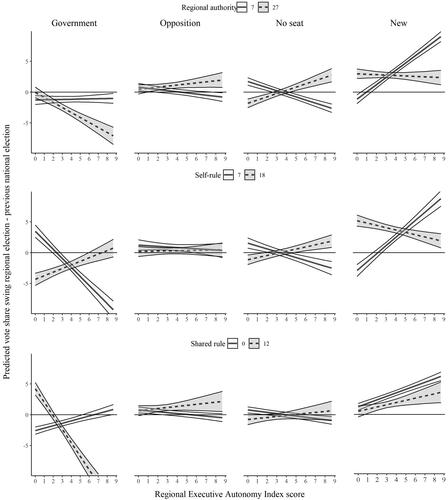

displays the marginal effects of the interaction between executive autonomy and regional authority on vote share swings between regional and previously held national elections incurred by government, opposition, no seat and new parties. Other variables are kept constant at their mean, median, or mode (Online Appendix Tables B1a and B1b). Full model results and the impact of the control variables are displayed in Online Appendix B. The results displayed in remain robust when (a) the model includes random slopes for party type, (b) the model includes interactions with party size; (c) the models include the nine indicators of the Regional Executive Autonomy Index separately, (d) excluding parliamentary elections that took place at the same time as direct elections for the executive and (e) the government party category includes parties that support minority national governments (Online Appendix C).

Figure 1. Marginal effects of executive autonomy and regional authority on party vote share swings.

Notes: Shown are predicted vote share swings between regional and previously held national elections and their 95% confidence intervals when executive autonomy and regional authority, self-rule and shared scores go from their minimum to their maximum (Online Appendix Table B1b). The estimates in are based on the model results presented in Online Appendix Table B2 which include 41,603 vote share swings for 2665 elections held in 282 regions in 14 countries ().

(top row) reveals that executive autonomy increases SOE-effects in regions with low and high authority. Government parties lose vote share no matter whether authority is high or low. Opposition and no-seat parties gain when authority is high but new parties win vote share when authority is low. We find very different impacts for self-rule and shared rule. Executive autonomy reduces SOE-effects when self-rule is high (, middle row) and this result provides support for hypothesis 1. Government parties lose less vote share, no-seat and new parties win votes although the vote share gains for the latter decline when executive autonomy and self-rule increase. However, executive autonomy increases SOE-effects when regions exercise shared rule (, bottom row) and this result does not provide support for hypothesis 1. Government parties lose more vote share and opposition parties gain when executive autonomy and shared rule increase.

The contrasting effects for self-rule and shared rule can be explained by a fourth way in which voters can make their SOE-vote count, i.e. a ‘balance vote’. Shared rule is the authority exercised by a regional government over the statewide territory together with other regional governments and the national government. It is exercised through regional representatives in an upper chamber of national parliament or through intergovernmental meetings between national and regional ministers. Regional shared rule provides voters with a possibility to balance a left/right-wing national government with a right/left-wing regional government with the expectation that regional governments will be able to moderate national policy (Carrubba and Timpone Citation2005; Erikson Citation1988; Lau Citation1985; Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013). Hence, in addition to use an SOE-vote to punish national government, to express preferences regarding SOE-area policies, or to impact the selection of the SOE-arena executive, voters may also use their SOE-vote to impact national policy outcomes.

The upshot is that our main hypotheses 2 and 3—i.e. executive autonomy decreases SOE-effects when authority is high, but executive autonomy increases SOE-effects when authority is low—is confirmed for regions that exercise self-rule but not shared rule (41% of the number of regional elections included in our dataset, Online Appendix Table A2a). Executive autonomy increases SOE-effects when regions score high on both self-rule and shared rule, but one should be careful in interpreting this as empirical evidence that voters use their SOE-vote to punish parties in national government. It is likely that voters from regions that exercise shared rule cast a ‘balance vote’ and seek to impact national policy through selecting national opposition parties for the regional executive.

To get closer to the causal mechanisms underlying SOE-voting, we display average vote share swings for 142 personal lists (competing in 573 regional elections) and 371 regionalist parties (competing in 1373 regional elections) for four different institutional regimes, i.e. regions which have regional authority and executive autonomy scores below (low) or above (high) the median score (). Personal lists include independent candidates, dissidents and party labels that contain the first and/or last name of a person. Further detail on the coding is provided in Online Appendix D. Personal lists are likely to be able to capitalise on voters who are discontent with national politics. By adopting different labels and names, candidates can portray themselves as being different from (statewide) parties and thereby they may be particularly successful in mobilising voters who are discontent with the performance of the parties in national government (Chhibber and Kollman Citation2004: 81–100; Pedersen and Rahat Citation2021). Voters are also more willing to ‘experiment’ with their vote when authority is low. The attractiveness for personal lists to acquire the vote from dissatisfied voters depends on the attractiveness of winning executive office which, in turn, depends on executive autonomy. As a result, personal lists should be able and eager to attract votes when regional authority is low but executive autonomy is high. The average vote share swing (7.6%) incurred in elections in regions where authority is low and executive autonomy is larger and statistically significantly different (p < .01) from the vote share swings won in regions where both authority and executive autonomy are high (2.3%) or executive autonomy is low (-2.0% and −0.1%). Clearly, personal parties thrive in regions where executive autonomy is high but regional authority is low.

Table 4. Average vote share swings won by personal lists and regionalist parties.

A regionalist party prioritises an autonomy demand and often claims (to be able) to govern their region in its best interest (Massetti and Schakel Citation2016, Citation2021; Online Appendix D). Regionalist parties are more likely to win votes when authority increases and regional competences include issues regional voters care about (Brancati Citation2008; Massetti and Schakel Citation2017). Executive autonomy provides further incentives for voters to vote for regionalist parties, especially when voters would like regional policy to be tailored towards a region’s interests. Impacting the choice of the executive becomes more relevant when executives have control over decision-making and implementation of regional policy. Hence, one may expect regionalist parties to be able to attract votes when both regional authority and executive autonomy are high. The average vote share swing incurred by regionalist parties in elections held in regions where both authority and executive autonomy are high (2.4%) is larger and statistically significantly different (p < 0.01) from the swings incurred in regions with either low regional authority (1.0% and 0.9%) or low executive autonomy (1.4%). Thus, voters are more inclined to support regionalist parties when regional authority and executive autonomy are both high.

Conclusion and discussion

Despite a wealth of studies on SOE-elections, one of its main assumptions has rarely been subject to an empirical test: SOE-effects especially emerge when voters do not have a possibility to impact the choice of an executive. Our theoretical contribution is to develop an argument on why and when SOE-effects are reduced because of voters having an opportunity to impact the selection of an executive. First, we have argued that voters can use their SOE-vote in three ways: to hold their national governments accountable, to express their policy preferences, or to impact the choice of the executive. Second, we argued that executive autonomy—i.e. the extent to which executives are independent from the parliament regarding their formation, termination and execution of their competences—incentivises voters to use their vote to impact the selection of the executive. Third, we argued that executive autonomy strengthens the impact of authority. Selecting parties or candidates for executive office becomes more important when authority increases. Voters are then not only concerned about voicing their policy preferences, they also consider which parties and candidates are likely to be included in the executive. When authority is low, most voters are concerned with using their SOE-vote to voice their discontent with the national government. These votes can be easily harvested especially by parties and candidates that are not associated with parties that are included in the national government. And the incentives for parties to win these votes become more attractive when executive autonomy increases.

The findings support our arguments and executive autonomy reduces SOE-effects when authority is high, but increases SOE-effects when authority is low. Furthermore, the findings strongly suggest a fourth way in which SOE-voters can make their regional vote count. When regions exercise shared rule, voters can seek to balance national and regional governments with the objective to impact national policy. These results have important implications for parties and party systems also at the national level. We find that new and personalised lists thrive in institutional environments where authority is low but executive autonomy is high. By gaining presence in the SOE-arena these parties may subsequently be able to successfully compete in national elections. Thereby these parties may contribute to the fragmentation of party systems in national parliaments (Bolleyer and Bytzek Citation2013; Bolleyer et al. Citation2012; Tavits Citation2008) and strengthen the personalisation of national politics (Pedersen and Rahat Citation2021).

Our findings have important implications for the second-order election model and regional voting because they reveal a lack in our understanding what motivates voters to cast a vote for a particular type of party. Voting for opposition, new, regionalist and personalised parties have in common that they each can attract the ‘protest vote’ against a national government party. However, we have little theory to explain under what conditions a voter opt for one instead of another type of a party. A voter may be ‘policy-seeking’ and vote an opposition party into regional office which can then impact national policy to the extent that the regional government exercises self-rule and shared rule. A voter may be dissatisfied with both the parties in government and opposition and opt for casting an ‘experimental’ vote for a new party to observe how it performs in the regional electoral arena. Or a voter may cast a vote for a presidential candidate from a personalised party who is thought to be the most capable to head the regional executive. A vote for a regionalist party can be driven by an evaluation of which party offers the best policy program for the region. Analysing vote shares by party type only helps to understand second-order and regional voting to the extent that a classification of parties taps directly into voter motivations underlying a ballot. This challenge can be addressed by analysing regional election surveys which, however, are relatively rare in comparison to European and national election surveys.

Our research also has important implications for the design of subnational electoral democracy. A significant decentralisation trend since the 1970s has introduced regional elections and empowered regions across Europe (Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Loughlin et al. Citation2011). There is a widely supported democratic norm that voters should be able to express their policy preferences and be able to hold executives accountable in their regions (Council of Europe Citation1985; OECD Citation2019; Treisman Citation2007). Our results clearly reveal that the extent to which voters are able and willing to do so is highly dependent on the ways in which executive autonomy is combined with regional authority. Regional electoral democracy thrives when regional authority and executive autonomy are both high but wanes when low levels of decentralisation are combined with autonomous executives.

To the extent that parliament–executive relations in the European Union can be compared to those in European regions, our findings also have important implications for the design of supranational electoral democracy. The European Union scores 3.16 before and 3.66 since the Lisbon Treaty on our executive autonomy indicator (Online Appendix E). The higher score reflects a stronger role for the Commission President in the appointment of vice-presidents. Our research suggests that this reform may have increased rather than decreased SOE-effects in European elections. Our multilevel regression model estimates the size of the beta coefficient for executive autonomy to be 1.28 (Online Appendix Table B2). Hence, a 0.5 point increase in executive autonomy translates into a 0.6 percentage point larger vote share for new parties. Many proposals to address the ‘democratic deficit’ of the European Union involve the strengthening of the link between a cast vote in European Parliament elections and the formation of the European Commission (Christiansen Citation2016; Hix Citation2002; Hobolt Citation2014). Our research strongly suggests that such reforms would significantly reduce SOE-effects. The European Union’s score on executive autonomy may decrease by two points when (parties in) the European Parliament would appoint the members of the Commission (Online Appendix E), potentially reducing the vote share won by new parties up to 2.6 percentage points.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (3.4 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Raimondas Ibenskas, Jonas Linde, Tom Louwerse, Tim Mickler, Christoph Niessen, Simon Otjes and Wouter Veenendaal for their feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arjan H. Schakel

Arjan H. Schakel is Professor in Comparative Territorial Democracy at the University of Bergen. He is editor of the annual special issue on regional elections of the journal Regional & Federal Studies, editor of the book series Comparative Territorial Politics (Palgrave Macmillan), and he has edited two books on regional elections in Central and Eastern and in Western European countries (Palgrave Macmillan 2013, 2017). Arjan is the co-developer of the Regional Authority Index, which traces regional authority in 90 countries since 1950 (Oxford University Press, 2016). He has published in journals such as Comparative European Politics, Comparative Political Studies, European Journal of Political Research, European Union Politics, Governance, Government and Opposition, Journal of Common Market Studies, Party Politics, Publius, Regional & Federal Studies, Regional Studies and West European Politics. [[email protected]]

Alexander Verdoes

Alexander Verdoes is a PhD candidate at the University of Bergen. His research focuses on the functioning of regional electoral democracy in Europe. He has been involved in the development of the European Regional Democracy Map. He has published in Electoral Bulletins of the European Union and Parliamentary Affairs. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 In this article, we do not analyse turnout rates. Turnout is related to vote share losses incurred by government parties to the extent that the share of dissatisfied voters increases in proportion to a decrease in turnout.

2 Hobolt and Høyland (Citation2011) analyse whether voters use European election to select candidates and they find that voters prefer candidates with more political experience. However, their study focuses on selecting candidates for parliamentary seats and not for executive office.

3 Another argument raised in the debates around the democratic deficit in the European Union is that competitive party government also requires cohesive Euro-parties (Hix Citation2008).

4 Parties competing in regional elections often form pre-electoral alliances because they are required to present one party list which determines the seat allocation. The allocation of the seat bonus across members of the alliance is either laid down in an alliance agreement that needs to be submitted before the election takes place (lista regionale; Italy), or it is determined by the order of the candidates on the party list (France and Greece).

5 For France we also include the party of the president because executive authority at the national level is shared between a president and a cabinet headed by the prime minister. The regional elections of 1998 are the only elections that took place under ‘co-habitation’, i.e. when the president is from a different party than the parties that deliver members to the cabinet.

6 In the SOE-model, a new party is not defined according to the date of its establishment but rather in relation to its participation in different types of election. A new party arises when it participates in an SOE but did not compete in a previously held FOE. Because of our focus on regional elections, a new party is also defined according to its presence in a particular territory. Hence, a party can be new in one region but not in another region in the same election year.

7 Voters in Swiss cantons can cast a vote for each of five to seven members of the executive but a strongly entrenched tradition of consociationalism results in all-party and oversized cantonal cabinets which reflect the electoral strength of the parties in the parliament (Bochsler and Bousbah Citation2015; Vatter and Stadelmann-Steffen Citation2013).

In Italian regions, the ballots for the presidency and assembly are tied through the allocation of a seat bonus that guarantees parties supporting the winning presidential list a majority in the legislature (Wilson Citation2015). In five Italian regions, voters can cast two votes, one for a party list that competes for parliamentary seats and one for a presidential candidate, but these votes are obligatory linked. A vote for a party list in the parliamentary election ties the presidential vote for the candidate supported by the party list. A vote for a presidential candidate limits the parliamentary vote to those party lists that support the candidate. Voters are strongly induced to coordinate their parliamentary and presidential votes and split-ticket voting appears to be limited: Plescia (Citation2017) reports vote swings of 0.25 percent at the aggregate level and below ten percent at the individual level.

8 We define a parliament–executive regimes as a unique set of scores on the nine indicators. Each region/regional tier appears at least once as a parliament–executive regime (Tables A2a and A2b).

9 The factor loading is relatively low because more than three-quarters of the 490 parliament–executive regimes receive a score of 0.66: 15.5% scores 0, 5.1% scores 0.33, 75.9% scores 0.66, and 3.5% scores 1. Although the discriminatory power of the indicator is relatively low, we do include this indicator in the Regional Executive Autonomy Index because voters should care more about selecting an executive who can dissolve the parliament.

10 This is the main reason why we do not include regional elections held on Åland (Finland), Faroe Islands and Greenland (Denmark), and Northern Ireland (United Kingdom).

References

- Anderson, Christopher J. (2000). ‘Economic Voting and Political Context: A Comparative Perspective’, Electoral Studies, 19:2-3, 151–70.

- Arter, David (2006). ‘Conclusion. Questioning the ‘Mezy Question’: An Interrogatory Framework for the Comparative Study of Legislatures’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 12:3-4, 462–82.

- Bingham Powell, G., Jr., and Guy D. Whitten (1993). ‘A Cross-National Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking Account of the Political Context’, American Journal of Political Science, 37:2, 391.

- Bochsler, Daniel, and Karima S. Bousbah (2015). ‘Competitive Consensus: What Comes after Consociationalism in Switzerland?’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:4, 654–79.

- Bolleyer, Nicole, and Evely Bytzek (2013). ‘Origins of Party Formation and New Party Success in Advanced Democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:6, 773–96.

- Bolleyer, Nicole, Joost van Spanje, and Alex Wilson (2012). ‘New Parties in Government: Party Organisation and the Costs of Public Office’, West European Politics, 35:5, 971–98.

- Bormann, Nils-Christian, and Matt Golder (2022). ‘Democratic Electoral System around the World, 1946–2020’, Electoral Studies, 78, 102487.

- Brancati, Dawn (2008). ‘The Origins and Strengths of Regional Parties’, British Journal of Political Science, 38:1, 135–59.

- Cabeza, Laura (2018). ‘“First-Order Thinking” in Second-Order Contests: A Comparison of Local, Regional, and European Elections in Spain’, Electoral Studies, 53, 29–38.

- Carrubba, Cliff, and Rochard J. Timpone (2005). ‘Explaining Vote Switching across First-, and Second-Order Elections: Evidence from Europe’, Comparative Political Studies, 38:3, 260–81.

- Chhibber, Pradeep, and Ken Kollman (2004). The Formation of National Party Systems: Federalism and Party Competition in Canada, Great Britain, India, and the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Christiansen, Thomas (2016). ‘After the Spitzenkandidaten: Fundamental Change in the EU’s Political System?’, West European Politics, 39:5, 992–1010.

- Clark, Nick, and Robert Rohrschneider (2009). ‘Second-Order Elections versus First-Order Thinking: How Voters Perceive the Representation Process in a Multi-Layered System of Governance’, European Integration, 31:5, 645–64.

- Council of Europe (1985). European Charter of Local Self-Government. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, available at: https://rm.coe.int/168007a088 (accessed 19 February 2024).

- Cutler, Fred (2008). ‘One Voter, Two First-Order Elections?’, Electoral Studies, 27:3, 492–504.

- Dandoy, Régis, and Arjan H. Schakel, eds (2013). Regional and National Elections in Western Europe: Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Döring, Holger Constantin Huber, and Philip Manow (2022). Parliaments, and Governments Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections, and Cabinets in Established Democracies. Development Version [Dataset]. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UKILBE.

- Erikson, Robert S. (1988). ‘The Puzzle of Mid-Term Loss’, The Journal of Politics, 50:4, 1011–29.

- Field, Andy, Jeremy Miles, and Zoë Field (2012). Discovering Statistics Using R. London: Sage.

- Golder, Sonia N., Ignacio Lago, André Blais, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Thomas Gschwend (2017). Multi-Level Electoral Politics: Beyond the Second-Order Election Model. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hague, Rod, and Martin Harrop (2001). Comparative Government and Politics: An Introduction (5th ed.). Houndmills: Palgrave.

- Heath, Anthony, Iain McLean, Bridget Taylor, and John Curtice (1999). ‘Between First, and Second Order: A Comparison of Voting Behaviour in European and Local Elections in Britain’, European Journal of Political Research, 35:3, 389–414.

- Hix, Simon (2002). ‘Executive Selection in the European Union: Does the Commission President Investiture Procedure Reduce the Democratic Deficit?’, SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–21.

- Hix, Simon (2008). What’s Wrong with the European Union, and How to Fix It. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Hix, Simon, and Michael Marsh (2007). ‘Punishment or Protest? Understanding European Parliament Elections’, The Journal of Politics, 69:2, 495–510.

- Hix, Simon, and Michael Marsh (2011). ‘Second-Order Effects plus Pan-European Political Swings: An Analysis of European Parliament Elections across Time’, Electoral Studies, 30:1, 4–15.

- Hobolt, Sarah B. (2014). ‘A Vote for the President? The Role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament Elections’, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:10, 1528–40.

- Hobolt, Sarah B., and Bjørn Høyland (2011). ‘Selection and Sanctioning in European Parliamentary Elections’, British Journal of Political Science, 41:3, 477–98.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2016). Community, Scale, and Regional Governance: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume II. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, Arjan H. Schakel, Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz, Sara Niedzwiecki, and Sarah Shair-Rosenfield (2016). Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hough, Dan, and Charlie Jeffery, eds (2006). Devolution and Electoral Politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Lau, Richard R. (1985). ‘Two Explanations for Negativity Effects in Political Behaviour’, American Journal of Political Science, 29:1, 119–38.

- Léon, Sandra (2011). ‘Who Is Responsible for What? Clarity of Responsibility in Multilevel States: The Case of Spain’, European Journal of Political Research, 50:1, 80–109.

- León, Sandra, and Lluis Orriols (2016). ‘Asymmetric Federalism and Economic Voting’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:4, 847–65.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S. (1997). ‘Who’s the Chef? Economic Voting under a Dual Executive’, European Journal of Political Research, 31:3, 315–25.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Richard Nadeau (2000). ‘French Electoral Institutions and the Economic Vote’, Electoral Studies, 19:2-3, 171–82.

- Lijphart, Arend (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Loughlin, John, Frank Hendriks, and Anders Lidström, eds (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maddens, Bart, and Liselotte Libbrecht (2009). ‘How Statewide Parties Cope with the Regionalist Issue: The Case of Spain – a Directional Approach’, in Wilfried Swenden (ed.). Territorial Party Politics in Western Europe. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 204–28.

- Marsh, Michael (1998). ‘Testing the Second-Order Election Model after Four European Elections’, British Journal of Political Science, 28:4, 591–607.

- Marsh, Michael, and Slava Mikhaylov (2010). ‘European Parliament Elections and EU Governance’, Living Review in European Governance, 5:4. https://www.europeangovernance-livingreviews.org/Articles/lreg-2010-4/

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg (2011). Parliament and Coalitions: The Role of Legislative Institutions in Multiparty Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Shane (2016). ‘Policy, Office, and Votes: The Electoral Value of Ministerial Office’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:2, 281–96.

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H. Schakel (2016). ‘Between Autonomy and Secession: Decentralization and Regionalist Party Ideological Radicalism’, Party Politics, 22:1, 59–79.

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H. Schakel (2017). ‘Decentralisation Reforms and Regionalist Parties’ Strength: Accommodation, Empowerment or Both?’, Political Studies, 65:2, 432–51.

- Massetti, Emanuele, and Arjan H. Schakel (2021). ‘From Staunch Supporters to Critical Observers: Explaining the Turn towards Euroscepticism among Regionalist Parties’, European Union Politics, 22:3, 424–45.

- Meulman, Jacqueline J., Anita J. van der Kooij, and Willem Helser (2004). ‘Principal Component Analysis with Nonlinear Optimal Scaling Transformations for Ordinal, and Nominal Data’, in David Kaplan (ed.). The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. London: Sage, 49–70.

- OECD (2019). Making Decentralization Work: A Handbook for Policy-Makers. Paris: OECD.

- Pedersen, Helene Helboe, and Gideon Rahat (2021). ‘Political Personalization and Personalized Politics within and beyond the Behavioral Arena’, Party Politics, 27:2, 211–9.

- Plescia, Carolina (2017). ‘The Effect of Pre-Electoral Party Coordination on Vote Choice: Evidence from the Italian Regional Elections’, Political Studies, 65:1, 144–60.

- Reif, Karlheinz, and Hermann Schmitt (1980). ‘Nine Second-Order National Elections: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results’, European Journal of Political Research, 8:1, 3–44.

- Schakel, Arjan H. (2015). ‘How to Analyze Second-Order Election Effects? A Refined Second-Order Election Model’, Comparative European Politics, 13:6, 636–55.

- Schakel, Arjan H. (2017). ‘Conclusion: Towards an Explanation of the Territoriality of the Vote in Eastern Europe’, in Arjan H. Schakel (ed.). Regional and National Elections in Eastern Europe. Territoriality of the Vote in Ten Countries. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 287–325.

- Schakel, Arjan H., and Régis Dandoy (2014). ‘Electoral Cycles, and Turnout in Multilevel Electoral Systems’, West European Politics, 37:3, 605–23.

- Schakel, Arjan H., and Charlie Jeffery (2013). ‘Are Regional Elections Really Second-Order?’, Regional Studies, 47:3, 323–41.

- Schmitt, Hermann (2005). ‘The European Parliament Elections of June 2004: Still Second-Order?’, West European Politics, 28:3, 650–79.

- Shair-Rosenfield, Sarah, Arjan H. Schakel, Sara Niedzwiecki, Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, and Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz (2021). ‘Language Difference and Regional Authority’, Regional & Federal Studies, 31:1, 73–97.

- Tavits, Margit (2008). ‘Party Systems in the Making: The Emergence, and Success of New Parties in New Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 38:1, 113–33.

- Thorlakson, Lori (2007). ‘An Institutional Explanation of Party System Congruence: Evidence from Six Federations’, European Journal of Political Research, 46:1, 69–95.

- Thorlakson, Lori (2009). ‘Patterns of Party Integration, Influence, and Autonomy in Seven Federations’, Party Politics, 15:2, 157–77.

- Treisman, Daniel (2007). The Architecture of Government: Rethinking Political Decentralization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tsebelis, George (1995). ‘Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Multicameralism, and Multipartyism’, British Journal of Political Science, 25:3, 289–325.

- Vatter, Adrian, and Isabelle Stadelmann-Steffen (2013). ‘Subnational Patterns of Democracy in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland’, West European Politics, 36:1, 71–96.

- Vatter, Adrian (2016). ‘Switzerland on the Road from a Consociational to a Centrifugal Democracy?’, Swiss Political Science Review, 22:1, 59–74.

- Wilson, Alex (2015). ‘Direct Election of Regional Presidents, and Party Change in Italy’, Modern Italy, 20:2, 185–98.