Abstract

International institutions are often challenged for being detached from the citizens. Focusing on the European Union, this article studies whether this is the case and, if so, when the European Commission responds to public opinion when pursuing policy integration. It argues that the Commission has legitimacy incentives encouraging it to be responsive but politicisation can suppress responsiveness by transmitting competing demands on the Commission from the member states’ citizens. To test these arguments, the contribution applied automated text analysis to estimate the European Union (EU) authority expansion entailed in the Commission’s legislative proposals between 2009 and 2019 and analysed its correspondence with public preferences over EU policy action across the EU states, measured using the Eurobarometer. The results lend support to the hypotheses and suggest that politicisation can undermine the responsiveness of international institutions.

In her speech at the closing event of the Conference on the Future of Europe on 9 May 2022, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, sent a strong message to European citizens, highlighting the Union’s willingness to respond to their demands: ‘Your message has been well received. And now, it is time to deliver’ (von der Leyen Citation2022). This drive to signal responsiveness has characterised the behaviour of institutional actors in the multilevel governance systems, including the European Union (EU) (Zürn Citation2014). As literature shows, public views and opinions on policies play a role in decisions agreed on the supranational level, and shape the behaviour of the EU’s electorally accountable (e.g. Hagemann et al. Citation2017; Wratil Citation2019) as well as its bureaucratic (e.g. Koop et al. Citation2022; Rauh Citation2016, Citation2019) institutions.

In this article, we study the responsiveness of the European Commission to the policy preferences of EU member states’ citizens. Specifically, we examine the extent to which the Commission’s ambitions to expand the authority of the Union are coined in response to the public demands for EU-level action in different policy domains. Drawing on the extant literature (Abbott and Snidal Citation1998; Börzel Citation2005; Hooghe et al. Citation2017), we conceptualise EU authority expansion as an increase in either the scope of its governance competences by ‘establishing EU legislation or programs in previously unaffected areas’ or in the level of EU existing governance competences within a policy domain relative to the national authority (Hagemann et al. Citation2017: 855). We posit that despite not being directly accountable to the citizens, the Commission is concerned about maintaining its own and the Union’s legitimacy and is, therefore, responsive in its pursuits to expand the authority of the EU through its policy proposals. Specifically, we expect when public demands for EU policy action increase, the EU agenda-setter to seek to broaden the competencies of the Union in the respective policy domain, and vice versa.

The need to maintain legitimacy has grown with the gradual politicisation of the Union and its affairs (Zürn Citation2014: 60). Politicisation, characterised by salience, polarisation, and actor mobilisation (Hutter et al. Citation2016), brings increased societal attention to the scope and exercise of political authority (Zürn Citation2014) and creates new opportunities to enhance responsiveness as well as new obstacles (De Bruycker Citation2020; Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2018; Koop et al. Citation2022; Zürn Citation2014). On the one hand, it might strengthen the Commission’s incentives to account for the preferences of citizens, who become its key stakeholders (Zürn Citation2014: 58), especially under the condition of policy salience (Koop et al. Citation2022; Rauh Citation2016, Citation2019) and when civil society actors get mobilised to voice public demands (De Bruycker Citation2020). On the other hand, it promotes the transmission of heterogeneous opinions of diverse publics to policy-makers. The resultant competing demands may hinder the overall responsiveness of the Commission, as some of the preferences inevitably get overlooked at the expense of others (Zürn Citation2014: 62). Here, we explore whether this is the case and, if so, how politicisation constrains or enables the Commission to shape the policy authority of the EU through its legislative proposals in line with public opinion.

In order to analyse the Commission’s responsiveness, we estimated the propensity of the Commission’s legislative proposals to expand EU authority using a semi-supervised machine learning technique. Unlike previous studies on the responsiveness of proposed and adopted legislation in the EU (Bølstad Citation2015; De Bruycker Citation2020; Williams and Bevan Citation2019; Wratil Citation2019), our focus lies on the substance of individual proposals with respect to their implications for the policy authority of the EU. This, in turn, allows us to analyse the link between the integration ambitions of the Commission and public opinion and politicisation across the member states. To estimate public preferences over EU policy action, their polarisation, and salience across policy areas, we relied on the Eurobarometer surveys. To measure the level of mobilisation of societal actors, who could transmit public demands across the EU to the Commission, we collected information from the EU transparency register.

The results show that overall the Commission is responsive to citizens’ preferences over EU policy integration. When the public supports EU action in a given policy area, the Commission seeks to broaden the authority of the Union in that area, and vice versa. However, growing politicisation, and in particular, higher actor mobilisation and public polarisation in the respective policy domain across EU member states, limits the Commission’s responsiveness. These findings enhance our understanding of the effect of politicisation on the behaviour of international institutions in response to public opinion. They further contribute to the literature concerned with the pace of European integration and its democratic responsiveness.

Public opinion and the European Commission

In a pioneering study on the responsiveness of democratic political institutions, Pennock (Citation1952: 790) defined it as ‘reflecting and giving expression to the will of the people’. By maintaining responsiveness, political actors and institutions ensure that their actions are seen as legitimate (Zürn Citation2014), and stimulate compliance with the policy measures they introduce (Dellmuth and Tallberg Citation2015; Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019).

Such concerns for legitimacy pertain also to the European Commission. Like the EU co-legislators that are electorally accountable to the citizens,Footnote1 there is evidence that the Commission, which is often seen as technocratic and detached from the public, also responds to public preferences. Haverland et al. (Citation2018) show that the Commission actively seeks public opinion in the areas where it can advance its credibility vis-à-vis member states. It also fosters broader societal involvement through consultations with stakeholders on salient proposals (Van Ballaert Citation2017),Footnote2 and responds to stakeholders’ substantive demands (Judge and Thomson Citation2019). The supranational agenda-setter signals its responsiveness to EU citizens by coordinating its political agenda with the EP (Giurcanu and Kostadinova Citation2022) and promoting publicly salient policy issues in its political programmes and annual working plans (Koop et al. Citation2022). Reh et al. (Citation2020) additionally show that the Commission’s attentiveness to public opinion further manifests itself in shaping its decision not to withdraw its proposals when they become subject to increasing public salience.

This literature explains the Commission’s incentives to maintain responsiveness to public demands at various policy-making stages with its pursuit of maintaining the legitimacy of European integration, on which its own existence and authority depends (Franchino Citation2007; Rauh Citation2021). The Commission is often perceived as holding rather pro-integration preferences (e.g. König and Pöter Citation2001; Tsebelis and Garrett Citation2000; Rauh Citation2019) and seeking further integration to increase its own influence (Majone Citation1996). Being endowed by the EU treaties with the monopoly to initiate and, thus, shape the content of any new legislation, it is likely to align the proposed measures with its preferences, and, thus, prioritise policies with a higher integration potential (Koop et al. Citation2022).

However, the legitimacy of the Commission could be undermined if its actions conflict with public opinion regarding the scope and level of the EU policy authority. To avoid this, the Commission is expected to moderate its attempts to broaden the Unions’ authority when the EU citizens oppose supranational action in a policy domain.

Another motivation for the Commission to act responsively is that it needs to consider the inter-institutional dynamics and preferences of the Council and the EP to increase the chances that its proposals get accepted and, as much as possible, unaltered. The members of the EP and the Council are directly or indirectly accountable to EU citizens and are likely to curb the extent of the proposed authority expansion when it is not aligned with the policy views of their electorates. That should create additional incentives for the Commission to balance the pressures stemming from the citizens across the EU in the content of its legislative proposals. We, therefore, hypothesise:

H1: The higher public support for given EU policy action across the member states, the more likely the Commission is to propose legislation that expands the EU authority in that policy.

Commission responsiveness in a politicised environment

Legitimacy concerns of political institutions become particularly pronounced under the pressure of politicisation (Zürn Citation2014). Literature maintains that politicisation brings political choices under the spotlight of public scrutiny, mobilises diverse stakeholders, and polarises the opinions (Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2018; Zürn Citation2014: 50). As a result, it reduces the opaqueness of international politics and exposes the choices of the political actors in the international arena to the public eye, making it more difficult for them to commit to new policies or agreements that would be unpopular and incur electoral costs back home (De Vries et al. Citation2021). This, in turn, could lead to policy failure as the political actors may opt not to commit to any new agreement at all.

In the EU context, politicisation is portrayed as a factor that can either stall the progress of integration by empowering Eurosceptic voices based on postfunctionalism (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 9), or, based in earlier neofunctionalist accounts, foster it by shifting ‘actor expectations and loyalty towards the new regional centre’ (Schmitter Citation1969: 166). These competing theoretical predictions about the impact of politicisation on European integration have been accompanied by a growth in empirical accounts. Literature shows that the politicisation of EU politics and policies fosters responsiveness of the national political elites to the demands of their electorate when they operate on the supranational level (Hagemann et al. Citation2017; Lo Citation2013; Schneider Citation2019b). Similarly, the growing salience of EU politics among the public, as well as the polarisation of views and actor mobilisation, translate into a more responsive law-making (e.g. De Bruycker Citation2020; Rauh Citation2016; Schneider Citation2019b). For instance, De Bruycker (Citation2020) finds that politicisation propagates the adoption of EU laws in response to public demands for more policy measures. Studying when policy change in the EU occurs, instead, Wratil (Citation2019) shows that it is shaped unequally by the demands of citizens of different EU member states, depending on the level of salience they attribute to given policy issues and the size of the national majority opinion. Analysing the Commission’s behaviour, Rauh (Citation2016) also shows that it tends to orient its policy towards public interests in a politicised environment (see also Rauh Citation2019).

These studies show that altogether politicisation can facilitate the policy responsiveness of the EU by increasing the pressure to maintain legitimacy in the public eyes (Zürn Citation2014). However, it is less clear how the different elements of politicisation – salience, polarisation and actor mobilisation – may shape the responsiveness of supranational actors. Many studies credit policy salience for strengthened responsiveness in a policy (Giurcanu and Kostadinova Citation2022; Koop et al. Citation2022). Instead, De Bruycker (Citation2020) finds that only societal actor expansion facilitates a policy change in response to increased public demands for it, conceptualising it as the mobilisation of diverse civil society actors that engage with European policies and can transmit public views to EU policy-makers.Footnote3 Hence, we offer a theoretical account of how each of the three constitutive elements of politicisation affects the Commission’s responsiveness to public opinion.

When a policy issue is salient, people pay more attention to and scrutinise the action of policy-makers (Bromley-Trujillo and Poe Citation2020; Koop et al. Citation2022; Schaffer et al. Citation2022). This, in turn, increases the motivation of the elites to respond to the public on salient matters as non-responsiveness is likely to yield electoral and reputational costs (Lax and Phillips Citation2012, Citation2009; Toshkov et al. Citation2020). Although the Commission is insulated from electoral pressures, it safeguards its reputation – public salience affects Commission’s communications with the citizens (De Bruycker Citation2017), its annual political priorities (Koop et al. Citation2022), decisions to keep legislation on the political agenda (Reh et al. Citation2020), and coordination with the EP (Giurcanu and Kostadinova Citation2022).

Overall, there is evidence suggesting that the Commission seeks to enhance its legitimacy in the eyes of citizens when the EU domestic visibility is heightened (Koop et al. Citation2022). Consequently, being exposed to public scrutiny given high public salience, the Commission should seek to avoid proposing policies that could threaten its legitimacy. Therefore, we expect that the public salience of a policy domain across the member states should amplify the responsiveness of the Commission to public demands for EU action in that domain. This translates into the following hypothesis:

H2: The relationship hypothesized in H1 is stronger, the higher the public salience of the respective policy domain across the member states.

H3: The relationship hypothesized in H1 is weaker, the more polarised the citizens across the member states are over the level of expansion of EU competences in the respective policy.

H4: The relationship hypothesized in H1 is weaker, the larger the variety of interests that are mobilized to shape the respective policy domain across the member states.

Data

In order to test our expectations, we compiled a dataset of all the EU legislative proposals by the Commission after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 and up to the 2019 EP elections, which fall under the ordinary legislative procedure. The list of 784 relevant proposals and metadata were obtained from Eur-Lex and complemented with information from the EP’s Legislative Observatory (LO) (European Parliament Citation2021). We categorised the Commission’s proposals into policy areas based on the policy categories from the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP)Footnote4 (Bevan Citation2019) and the European Union Policy Agendas Project (EUPAP) (Alexandrova et al. Citation2014) using their EuroVoc descriptors (see Online Appendix 1.3).

Following Hagemann et al. (Citation2017: 858), to assess whether these proposals entail expansion of EU policy authority, we used their summaries by the EP staff in the parliamentary Legislative Observatory. These summaries outline the purpose and legal basis for each legislative proposal, its background, content, and potential budgetary implications. Relying on the summaries rather than on the full proposal texts allowed us to avoid formalistic language that is specific to the legislative texts (Cross and Hermansson Citation2017: 589), while not trading off the substance of the legislative proposals.

To measure the propensity of the legislative proposals to expand EU authority, we trained a ridged-regularised logistic regression classifier (Hastie et al. Citation2009) using a hand-coded training set of 117 summaries, balanced across policy domains and EP terms (the selection and codebook for the training set are discussed in Online Appendix 1.1). Two coders independently annotated each summary with respect to whether it entails expansion of EU authority (1) or not (0). Similarly to the previous studies, coders were not able to detect possible retrenchment of the EU powers (Hagemann et al. Citation2017). This aligns with the literature emphasising that the Commission’s existence and competences depend on the EU authority, discouraging it from cutting EU powers (Reh et al. Citation2020).

As a next step, the annotated summaries were used to a train logistic regression classifier.Footnote5 The classifier yielded a binary indicator that assigns the proposals into those that expand and those that do not expand EU authority, and a continuous measure that represents the probability of each proposal to expand EU authority that varies between 0 and 1. The latter serves as our dependent variable to capture the uncertainty of the classification (in Online Appendix 1.1, Figures 4 and 5 display the raw distributions, while Figure 6 summarises its distribution across policy areas and years).

As our main independent variables, we measured the EU-wide Public support for EU action in the policy area of a proposal two years before the proposal, in line with our theory. We used all Standard, Special, and Flash Eurobarometer surveys that were carried out between 2008 and 2019. Following state-of-the-art research (e.g. Gilens Citation2012; Wratil Citation2019), we identified the relevant questions across the survey waves and classified them into CAP-EUPAP policy areas and subcategories. Thereafter, we selected only one question per unique policy subcategory and year to avoid any estimation bias due to repeated questions on a policy area within a year. Next, we re-coded the response options into three categories – support for the status quo, approval of more EU action in a policy area, or opposition to it (see Online Appendix 1.2). Then, for each question, we estimated the percentage of responses that indicated support for EU action out of the total number of meaningful responses, by country. To obtain a yearly measure of country-specific support for EU action for each CAP-EUPAP policy area, we took the average percentage of responses that approve the expansion of EU authority in a specific policy area and year, across all the unique policy subcategory questions falling in that policy area.Footnote6 Finally, to obtain the EU-wide public support, we took the average of the country-specific support indicators (and considered an alternative weighted average indicator among our robustness checks at the end of the next section).

To test how the politicisation of the EU policies affects the Commission’s responsiveness, we assessed the interaction effects of public support for EU action and each of the three elements of politicisation – salience, polarisation, and actor mobilisation. Following our theoretical model, as well as the extant literature (De Bruycker Citation2020; Koop et al. Citation2022), we lagged the estimates of all three politicisation measures, presented below, by one year. This approach ensures that politicisation follows the formation of public views and EU policy-makers and institutions have time to observe and respond to the level of salience the public attaches to the issue.

For our Salience measure, we used the same Eurobarometer questions as those we selected to estimate public support. We first measure the country-level salience of the policy areas as one minus the share of ‘Don’t know’ responses out of the total number of responses to the selected questions (following Gilens Citation2012; Page and Shapiro Citation1983; Wratil Citation2019).Footnote7 Second, we used the average of country-specific measures of salience to obtain the EU-wide indicator.

To measure EU-level public Polarisation, using the same questions and aggregation, for each EU member state, we calculated the absolute difference between the share of respondents supporting certain EU policy action, and the share of respondents opposing it. We then subtracted the difference from 1 so that higher values of the measure indicated higher levels of polarisation. Thus, Polarisation = 1 − |Share of Supporting Responses − Share of Opposing Responses|. Similarly to the measure of salience, we took the average of resulting country-specific measures.

The Actor mobilisation measure is obtained using information from the Commission’s Transparency Register.Footnote8 The register allows tracing the number and type of organisations and groups registered across the EU countriesFootnote9 in any given year that can be potentially consulted during the EU decision-making process. As it also indicates their primary policy area of interest, we were able to map the organisations into our CAP-EUPAP classification (see Online Appendix 1.5). We assume that registration in the Transparency Register indicates an aspiration to be involved in the EU’s policy-making process and represent certain interests. To test our argument that actor mobilisation limits the Commission’s policy responsiveness to the public by presenting it with competing demands, we used a conservative measure of actor mobilisation on the EU level, summing up the number of organisations and groups registered in each country, year, and policy area but excluding business groups and companies. This is because the latter groups are more likely to represent special business interests (see Binderkrantz et al. Citation2021), which are not necessarily aligned with the preferences of the citizens (Gilens and Page Citation2014). Literature shows that specialised interests, such as business groups, tend to transmit a limited amount of information on public preferences to policy-makers (Flöthe Citation2020; Giger and Klüver Citation2016) and their positions are generally less supported by the public (Flöthe and Rasmussen Citation2019). Furthermore, business groups and firms are less likely to inform policy-makers about the citizens’ preferences, but rather focus on the transmission of technical information, allowing them to tilt regulatory rules in their favour (Flöthe Citation2020; Klüver Citation2011).

We also included several control variables in our models. The public responsiveness of the Commission may be driven by its anticipation of potential conflicts between the EU legislators (Rauh Citation2021). Literature shows that a gridlock resulting from the mismatch between the EP’s and the Council’s preferences influences the outcome of EU policy making (Franchino Citation2005) as well as the extent of the legislative activity (Crombez and Hix Citation2015). A prospective inter-institutional gridlock could also prevent the agenda-setter (Commission) from initiating legislation (see Boranbay-Akan et al. Citation2017; Borghetto and Mäder Citation2014). Similarly, it may incentivise the Commission to tone down any aspirations it may have to increase the EU policy authority and, thus, its own authority, in order to prevent heavily amended and, potentially, failed legislation, irrespective of public opinion. We, therefore, control for the absolute distance between the policy preferences of the Council and the EP as a proxy for Inter-institutional conflict.

To construct this control variable, we measured governments’ preferences in the Council and the preferences of the parties represented in the EP by relying on parties’ national electoral manifestos (Volkens et al. Citation2020), following the literature (e.g. Crombez and Hix Citation2015; Haag Citation2022; Klüver and Sagarzazu Citation2013) and using a weighted mean approach (Warntjen et al. Citation2008). Using the MARPOR data, we identified which coded issue categories relate to the CAP-EUPAP policy areas and classified them into negative and positive clusters (see Online Appendix 1.4). Following the convention, the positions of individual parties were then captured by employing the log-transformations proposed by Lowe et al. (Citation2011). To measure the Council’s position, we first constructed the mean positions of all member state governments between 2008 and 2019, weighting the positions of their constituent cabinet parties (Döring and Manow Citation2020) by party seat-share in the national parliaments relative to the government seat share in parliament. Second, we estimated the position of the Council in the Council configuration specific to each Commission’s proposal as the mean of the governments’ positions weighted by the respective member states’ population sizes in the EU. In doing so, we follow the literature that underlines the predominance of compromise in the Council (Klüver and Sagarzazu Citation2013; Thomson Citation2011) as well as findings suggesting that models using (weighted) mean-based position of the Council show similar performance to those that rely on a more complex operationalisation of actors’ preferences (Arregui et al. Citation2006).

To estimate the preferences of the EP, we summed the policy preferences of all parties in each EP term,Footnote10 weighted by the party EP seat shares in that term (see Haag Citation2022). Finally, we measured the absolute difference between the Council and the EP preferences.

Furthermore, we include a control for the Complexity of proposals. We followed Migliorati (Citation2021) and relied on the number of terms included in the EuroVoc descriptor attached to the legislative proposal at hand. The underlying logic is that the more descriptors are associated with the proposal, the more policy issues it touches upon, which in turn translates into a higher degree of its complexity.

Next, the extent of EU authority expansion could be affected by the existing levels of integration or years of EU competence (N of competence years) in different policy areas. In policy areas where the EU has enjoyed competences for a longer time, the extent of possible authority expansion could be more constrained than in policy areas in which the EU acquired competences more recently. To account for such a variation, we calculated the number of years between the proposal date and the date of the first adopted EU legislation in the policy area of the proposal (see Online Appendix 1.6).

Method and analysis

We used fractional regression to test our hypotheses because our dependent variable is bound between 0 and 1. Unlike other methods (such as beta-regression), this approach allows for the observations to take extreme values, while not generating out-of-bound predictions (see Papke and Wooldridge Citation1996). Our unit of analysis is a proposal.

The results are presented in . Model 1 tests the first hypothesis concerning the overall effect of public preferences over EU policy action on the likelihood that the Commission advances increased EU policy authority in its legislative proposals. In Models 2–4, we further examined how politicisation aspects – public salience, polarisation, and actor mobilisation in the respective policy area of a proposal – condition the effect of public opinion.

Table 1. Fractional regression analysis of the probability of EU authority expansion in the Commission proposals.

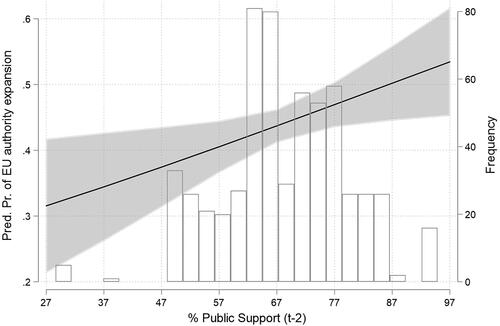

In line with Hypothesis 1, the higher the two-year lagged public support for EU action in a given policy area, the higher the likelihood that the Commission pursues EU authority expansion in its legislative proposals in that area, and vice versa. summarises the results by plotting the predicted probabilities based on Model 1. As the figure shows, on average, a 10 percentage point higher public support for EU policy action across the member states leads to about a 3.2 percentage point increase in the probability of EU authority expansion envisioned in the Commission’s proposals in the respective policy area.

Figure 2. Effect of public support for EU policy action on the probability of EU authority expansion in the Commission proposals.

Note: is based on Model 1 from .

While this effect is rather modest, in contrast to views of the Commission as a technocratic bureaucracy that unwaveringly pursues the expansion of the EU’s and, thus, its own authority, this finding suggests that the Commission adjusts its proposals for EU policy authority expansion based on preferences of the member states’ citizens. This resonates with the literature suggesting that the Commission does respond to public pressure in its legislative activities (e.g. Rauh Citation2016, Citation2019). This strategy allows it to maintain its own legitimacy (e.g. Hartlapp et al. Citation2014), and the legitimacy of the EU as a whole.

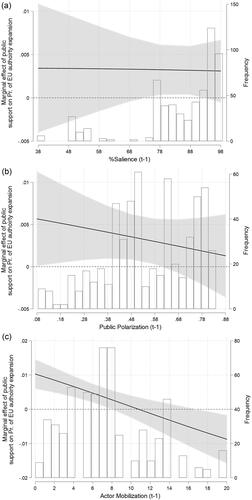

Models 2–4 in test our conditional hypotheses. Based on the interaction effects in these models, plots the average marginal effect of public support over levels of salience, polarisation and actor mobilisation, respectively.

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of public support at levels of salience, public polarisation and actor mobilisation.

Model 2 suggests that contrary to our H2, the level of salience that the publics across member states attribute to the EU action does not amplify the responsiveness of the EU Commission to citizens’ preferences over EU policy action. This is visible also in Panel (a) of . The plot shows that public support is positively associated with the probability of proposals for expanding EU authority only given rather high salience (over 73%, but the effect disappears at the highest levels of salience). However, an increase in salience does not translate into a stronger effect of public support, offering no support for our second hypothesis.Footnote11 These results are in line with the findings of De Bruycker (Citation2020), who also does not find evidence that salience conditions the responsiveness of EU policy outputs.

Model 3 tests our third hypothesis. Although the negative effect of the interaction term between public support at t − 2 and polarisation at t − 1 is in the expected direction based on H2, on average, it falls short of statistical significance. We scrutinised the effect further in panel (b) in . The figure shows that when member states’ citizens are, on average, more united in their stances (i.e. when polarisation < 62, which corresponds to approximately 70% of the citizens in a member state, on average, sharing the same view), there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between public support and the probability that the Commission proposes EU authority expansion. However, as polarisation grows beyond this level, this positive effect loses statistical significance (also see Figure 8 in Online Appendix 1.8). In other words, the pattern of responsiveness to public demands dissipates as polarisation grows stronger – the marginal effect associated with a unit increase in public support (at t − 2) declines from 0.6 percentage points at the lowest observed levels of average polarisation (at t − 1) to 0.3 percentage points as polarisation reaches the level of 0.62. Once public polarisation reaches levels exceeding this cut-point, the significant positive relationship between public support and the proposed expansion of EU authority disappears. This result aligns with our argument that when citizens are divided, the Commission’s ability to modulate the proposed expansion of the Union in line with public opinion declines. We argued that this is the case because the Commission is unable to cater to divided public preferences. By modulating the integration ambition of its policy proposals in the face of diverging preferences, it avoids legitimacy costs for catering to some at the expense of other preferences.

Finally, Model 4 lends clear support for H4. The total level of societal actor mobilisation across the member states (at t − 1) weakens the Commission’s responsiveness to citizens’ policy preferences over policy integration (articulated at t − 2). As panel (c) in shows, higher mobilisation of societal actors suppresses the positive effect of public support on the probability of EU authority expansion, which fully dissipates if more than 8 groups are mobilised. In cases when mobilisation reaches higher levels (≥ 16 actors), the effect becomes negative and significant. On average, when societal actors are not mobilised, a unit increase in public support for EU policy action across the member states is associated with a 1 percentage point higher probability of a Commission proposal for EU authority expansion. At the maximum observed level of actor mobilisation (20), a unit increase in public support results in, approximately, a 0.9 percentage point decrease in this probability. This pattern aligns with our expectation that growing mobilisation across the EU hinders the responsiveness of the Commission by facing it with potentially competing demands that it cannot accommodate at the same time.

The effects of the control variables are consistent across the estimated models. As expected, a higher divergence of the preferences of the EP and the Council is associated with a negative effect on the probability of EU authority expansion in legislative proposals, yet falling short of statistical significance. However, the proposed level of authority expansion is affected by the pre-existing levels of EU authority in the respective policy area. The negative significant effect of the number of years of EU competence suggests that proposals that deal with policy areas that have a longer history of being managed at the EU level are less likely to expand supranational authority. In contrast, the more complex the proposal is, i.e. the more policy issues it touches upon, the more likely it is to expand the authority of the Union. Lastly, it is worth noting the significant independent effect of public salience on the probability of EU authority expansion. It tends to increase the probability of the Commission seeking to broaden the power of the Union. This effect aligns well with the previous findings (Koop et al. Citation2022), suggesting that the Commission may seek to increase the engagement of Union level coordination in the policy domains that are important to people across the states.

To assess the robustness of our main findings, we performed a series of additional tests (see Online Appendix 2). First, we examined whether the Commission is more responsive to public opinion in the bigger member states. To do so, we weighted the indicator for public support in each state by the voting weight that country has in the Council. The results show no significant independent effect of this new measure (see Model 1 in Table 19, Online Appendix 2.9), as opposed to the main effect of our simple average support across member states. Taken together, our results show no indication that the Commission discriminates between the citizens of small and large states when responding to their preferences.

Second, we considered that our operationalisation of actor mobilisation within the member states may not sufficiently account for the diversity of the organisations and stakeholders seeking to engage with the EU. Drawing on previous studies (Baroni et al. Citation2014), we, therefore, constructed the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), accounting for actor diversity for each country, year, and policy area, and then re-examined our models using the average of these new country-specific proxies (see Online Appendix 2.2). Additionally, we cross-checked whether the inclusion of business groups and stakeholders in our measure of actor mobilisation affects its conditioning effect on the relationship between public support and the probability of EU authority expansion (see Online Appendix 2.1).

Third, we challenged our results by adding a control for legislative instruments. The Commission may be more encouraged to pursue and expect member states to accept EU authority expansion when it proposes Directives, which member states are free to decide how to transpose, than Regulations which are directly applicable in member states after entry into force (this may already be a factor in the Commissions calculations, though, which is why we did not include this variable in our main analysis to avoid endogeneity) (see Online Appendix 2.3).

Fourth, we also examined the robustness of our results to excluding the most complex proposals, which may cover multiple policy areas (see Online Appendix 2.4). Fifth, we assessed the models with clustered standard errors at the policy level to account for the potential within-cluster correlations (see Online Appendix 2.6). Sixth, to assess whether our results are driven by the unobserved heterogeneity across time and between different Commissions, we introduced models with a control for the Commission’s term (see Online Appendix 2.7). Seventh, we also investigated how using different lags of the independent variables than those in our theory would affect the results (see Online Appendix 2.5). The independent effect of public opinion falls short of statistical significance when measured only a year before the proposal. This is not surprising, as this alternative model assumes that the Commission can observe and respond to the public opinion in a very short time, which is a strong assumption. Last, we introduced an alternative operationalisation of the inter-institutional conflict control variable, rooted in procedural rather than compromise models and following Crombez and Hix (Citation2015). Overall, our results withstand all these tests.

Conclusion

This article set out to examine the responsiveness of the EU Commission to public preferences over the level of European integration across policy areas. We argued that despite being insulated from electoral controls, the Commission responds to public views as it seeks to build a reputation as a responsive institution and thus ensure the legitimacy of the EU and its own authority. We further posited that given the growing politicisation of the EU, the responsiveness of the Commission may vary depending on the level of public salience, polarisation, and actor mobilisation in the policy domain and across the member states. We turned to the machine-learning technique to estimate the extent of EU authority expansion the Commission envisions in its proposals.

Our core result suggests that the Commission is generally responsive to the public mood and is likely to tailor any proposals for EU authority expansion to the views of the citizens. However, this responsiveness is weak and could be undermined by strong competing demands from the public or vastly mobilised interests, associated with the process of politicisation.

These results contribute to the broader literature concerned with the democratic deficit in the EU (Follesdal and Hix Citation2006). Our finding that the Commission is generally responsive to the public mood and the societal divisions within member states is positive news for representative democracy in the EU, with the caveat of the dampening effects of politicisation. The latter finding may suggest the lower responsiveness of technocratic international institutions more generally when they are subject to demands by organised groups with competing interests or when the citizens in the member states of an international organisation are divided. While going beyond the scope of our study, these propositions offer interesting opportunities for future research.

Furthermore, we add to the burgeoning research focused on EU institutional responsiveness and institutional legitimacy in the face of increased politicisation (Ershova et al. Citation2023; Tallberg and Zürn Citation2019; Zürn Citation2014). By scrutinising the effects of the constitutive elements of politicisation across the member states, we flesh out a detailed pattern of responsiveness within the EU Commission. We show that a united public stance motivates the Commission to align its ambitions more with citizens’ preferences. Yet, this responsiveness dissipates as citizens become more divided. Similarly, a higher level of actor mobilisation diminishes the responsiveness of the Commission to public demands. This behaviour aligns with the logic of reputation and legitimacy seeking: facing competing public demands about the future of the Union, the Commission is less responsive to any given demands to avoid unintentionally addressing the interests of one group, while alienating another group. Being an institution with strong pro-integration preferences and vested interests in the legitimacy of the EU (König and Pöter Citation2001; Rauh Citation2019; Tsebelis and Garrett Citation2000), the Commission restrains its ambitions to broaden the power of the EU in order to gain legitimacy for the maintained authority transfer from the national to the supranational level across the broader public. The limited Commission responsiveness given high actor mobilisation contrasts with the finding by De Bruycker (Citation2020) of reinforced responsiveness of adopted EU policies given the mobilisation of civil society groups. Possibly, the Commission is under greater pressure from competing actor demands than the EP and the Council, leading it to propose less ambitious proposals than those that the public would have preferred, which are then amended by the EU legislators. Alternatively, it may be targeted by diverse actors more than the EP and the Council are in the later stages of the legislative process. This warrants further research.

Besides these main results, our findings hint towards potential strategic motivations of the EU agenda-setter at the stage of the proposal formulation for highly salient issues. Previous studies emphasise that the Commission addresses the matters which are deemed salient by the public (e.g. De Bruycker Citation2017) and tends to withdraw fewer proposals within such domains (Reh et al. Citation2020). We further show that the Commission is significantly more likely to advance further policy integration in areas of high public salience. A possible explanation is the low attractiveness of the status quo given a highly salient policy matter, which necessitates policy action and therefore the need for the Commission to pursue deeper policy integration, irrespective of public preferences. While it might not be responsive, such behaviour by the Commission may be seen as responsible as it offers problem-solving where it is most important or necessary. Yet, it is also self-serving as deeper policy integration increases the authority of the Commission. In line with the recent study by Koop et al. (Citation2022) on the Commission’s agenda-setting, we thus conclude that given favourable conditions of high policy salience the Commission opts for legislation that expands EU competences.

Finally, this article has explored the opinion-policy links and the moderating role of politicisation in the context of EU authority transfer. Whilst focusing on the European authority dimension allows us to examine how and when the domestic public shapes the scope and depth of EU integration, it is possible that the politicisation has different effects on the level and patterns of the Commission’s responsiveness on other dimensions of conflict. To explore this possibility, future research could map domestic patterns of contestation and debate of the EU policies along ideologically driven left–right and/or GAL-TAN dimensions.

Author contributions

Yordanova: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing; Visualisation; Project administration; Supervision; Funding acquisition. Khokhlova: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Validation; Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing; Visualisation; Project administration. Ershova: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Validation; Analysis; Investigation; Data Curation; Writing; Visualisation; Project administration. Schmidt: Software; Methodology; Validation; Data Curation; Writing. Glavaš: Software; Methodology; Supervision; Funding acquisition.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.7 MB)Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Benedikt Ebing, Sarah Knabl, Daniel J. Whitten, and Bence Hamrák for their invaluable help with collecting legislative data and public opinion indicators. We would like to thank Catherine de Vries, Adriana Bunea, Oliver Treib, Michelle Cini, Babak Rezaeedaryakenari, the participants of EPSA 2021, UACES 2021 conferences and INDIVEU Workshop 2021 as well as the reviewers for their comments and suggestions on the earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and script reproducing the findings of this study are available at https://github.com/Norface-EUINACTION/Curb_EU_replication_files.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nikoleta Yordanova

Nikoleta Yordanova is Associate Professor of European Politics at Leiden University’s Institute of Political Science. Her research on responsiveness, delegation, and compliance in the EU as well as coalition politics has appeared in the American Political Science Review, European Union Politics, Journal of Common Market Studies, Journal of European Public Policy, and Party Politics, among others. She currently leads the EUINACTION project. [[email protected], @NYYordanova]

Aleksandra Khokhlova

Aleksandra Khokhlova is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Political Science, Leiden University. Her work focuses on political representation, parliamentary behaviour, and EU legislative process. [[email protected], @shurakhokhlova]

Anastasia Ershova

Anastasia Ershova is a Lecturer in Public Policy at the School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics at Queen’s University Belfast. Her ongoing work focuses on policy responsiveness and delegation processes in the EU. [[email protected], @AnastasiaErsho8]

Fabian David Schmidt

Fabian David Schmidt is a PhD candidate at the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Data Science (CAIDAS), University of Würzburg and works on topics of multilingual representation learning and sample-efficient cross-lingual transfer. [[email protected], @fdschmidt]

Goran Glavaš

Goran Glavaš is a Professor at the University of Würzburg, holding the Chair for Natural Language Processing at the Center for Artificial Intelligence and Data Science (CAIDAS) and Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science. His research focuses on computational language understanding, multilingual NLP and cross-lingual transfer, as well as fair and trustworthy AI. He currently serves as co-PI on the EUINACTION project. [[email protected], @gg42554]

Notes

1 Public opinion towards the EU (Hagemann et al. Citation2017; Wratil Citation2018) and its specific policies (Hobolt and Wratil Citation2020; Schneider Citation2019b) shapes the behaviour of the European Parliament (EP) and the Council of Ministers at different stages of policy making (see Zhelyazkova et al. Citation2019). They signal their responsiveness to the public when they deliberate (Hobolt and Wratil Citation2020), negotiate (Schneider Citation2019a,Citationb), or vote on policy proposals (Hagemann et al. Citation2017; Lo Citation2013).

2 As research suggests, such broad consultations empower the Commission vis-à-vis other institutions during the legislative process (Bunea and Thomson Citation2015).

3 Others have conceptualised actor expansion as related rather to the mobilisation of political parties representing diverse citizen views (e.g. Kriesi Citation2007; Kriesi and Hutter Citation2019; Turnbull-Dugarte Citation2020).

4 We split the original ‘Agriculture and Fisheries’ area into two separate areas.

5 We opted for logistic regression as a classifier because it showed superior performance in comparison to the other commonly used techniques (Table 2 in Online Appendix 1.1 summarises the performance of the competing methods).

6 We used post-stratification weights provided by the Eurobarometer when calculating survey-based indicators.

7 While there are other widely-used proxies for policy issue salience, such as ‘Most Important Problem’ (MIP) questions (Koop et al. Citation2022) or media attention to the policies (De Bruycker Citation2020; Reh et al. Citation2020), using ‘Don’t know’ responses provides two advantages. First, it allows us to obtain a comprehensive salience measure for every policy area and year for which we have data on public support. In contrast, while MIP questions are asked consistently throughout the years and Eurobarometer waves, their response options are limited to several policy areas only. Second, our measure of salience covers all EU member states. Obtaining the salience measures from national media for the same sample of states would be a highly laborious task, while relying on EU-wide media outlets, as some studies do (see e.g. De Bruycker Citation2020), does not allow gauging the salience within the individual states.

9 We consider the headquarters location to identify the country of origin.

10 For the 7th EP, we accounted for the accession of Croatia and estimated distinct positions for the periods before and after 1 July 2013.

11 For an illustration of the predicted probability of EU authority expansion at fixed levels of salience, see Figure 8 in the Online Appendix 1.8.

References

- Abbott, Kenneth W., and Duncan Snidal (1998). ‘Why States Act through Formal International Organizations’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42:1, 3–32.

- Alexandrova, Petya, Marcello Carammia, Sebastian Princen, and Arco Timmermans (2014). ‘Measuring the European Council Agenda: Introducing a New Approach and Dataset’, European Union Politics, 15:1, 152–67.

- Arregui, Javier., Frans N. Stokman, and Robert Thomson (2006). ‘Compromise, Exchange and Challenge in the European Union’, in Robert Thomson, Frans N. Stokman, Christopher H. Achen, and Thomas König (eds.), The European Union Decides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 124–52.

- Baroni, Laura, Brendan J. Carroll, Adam William Chalmers, Luz Maria Muñoz Marquez, and Anne Rasmussen (2014). ‘Defining and Classifying Interest Groups’, Interest Groups & Advocacy, 3:2, 141–59.

- Bevan, Shaun (2019). ‘Gone Fishing: The Creation of the Comparative Agendas Project Master Codebook’, in Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman (eds.), Comparative Policy Agendas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 17–34.

- Binderkrantz, Anne S., Jens Blom-Hansen, and Roman Senninger (2021). ‘Countering Bias? The EU Commission’s Consultation with Interest Groups’, Journal of European Public Policy, 28:4, 469–88.

- Boranbay-Akan, Serra, Thomas König, and Moritz Osnabrügge (2017). ‘The Imperfect Agenda-Setter: Why Do Legislative Proposals Fail in the EU Decision-Making Process?’, European Union Politics, 18:2, 168–87.

- Borghetto, Enrico, and Lars Mäder (2014). ‘EU Law Revisions and Legislative Drift’, European Union Politics, 15:2, 171–91.

- Bromley-Trujillo, Rebecca, and John Poe (2020). ‘The Importance of Salience: Public Opinion and State Policy Action on Climate Change’, Journal of Public Policy, 40:2, 280–304.

- Bunea, Adriana, and Robert Thomson (2015). ‘Consultations with Interest Groups and the Empowerment of Executives: Evidence from the European Union’, Governance, 28:4, 517–31.

- Börzel, Tanja A. (2005). ‘Mind the Gap! European Integration between Level and Scope’, Journal of European Public Policy, 12:2, 217–36.

- Bølstad, Jørgen (2015). ‘Dynamics of European Integration: Public Opinion in the Core and Periphery’, European Union Politics, 16:1, 23–44.

- Crombez, Christophe, and Simon Hix (2015). ‘Legislative Activity and Gridlock in the European Union’, British Journal of Political Science, 45:3, 477–99.

- Cross, James P., and Henrik Hermansson (2017). ‘Legislative Amendments and Informal Politics in the European Union: A Text Reuse Approach’, European Union Politics, 18:4, 581–602.

- De Bruycker, Iskander (2017). ‘Politicization and the Public Interest: When Do the Elites in Brussels Address Public Interests in EU Policy Debates?’, European Union Politics, 18:4, 603–19.

- De Bruycker, Iskander (2020). ‘Democratically Deficient, yet Responsive? How Politicization Facilitates Responsiveness in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:6, 834–52.

- Dellmuth, Lisa Maria, and Jonas Tallberg (2015). ‘The Social Legitimacy of International Organisations: Interest Representation, Institutional Performance, and Confidence Extrapolation in the United Nations’, Review of International Studies, 41:3, 451–75.

- De Vries, Catherine E., Sara B. Hobolt, and Stefanie Walter (2021). ‘Politicizing International Cooperation: The Mass Public, Political Entrepreneurs, and Political Opportunity Structures’, International Organization, 75:2, 306–32.

- Döring, Holger, and Philip Manow (2020). Parliaments and Governments Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Modern Democracies [Dataset]. Retrieved from https://www.parlgov.org/

- Ecker-Ehrhardt, Matthias (2018). ‘Self-Legitimation in the Face of Politicization: Why International Organizations Centralized Public Communication’, The Review of International Organizations, 13:4, 519–46.

- Ershova, Anastasia, Nikoleta Yordanova, and Aleksandra Khokhlova (2023). ‘Constraining the European Commission to Please the Public: Responsiveness through Delegation Choices’, Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2224399

- European Parliament (2021). Legislative Observatory of the European Parliament, available at https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/home/home.do (accessed 18 March 2021).

- Flöthe, Linda (2020). ‘Representation through Information? When and Why Interest Groups Inform Policymakers about Public Preferences’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:4, 528–46.

- Flöthe, Linda, and Anne Rasmussen (2019). ‘Public Voices in the Heavenly Chorus? Group Type Bias and Opinion Representation’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:6, 824–42.

- Follesdal, Andreas, and Simon Hix (2006). ‘Why There Is a Democratic Deficit in the EU: A Response to Majone and Moravcsik’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44:3, 533–62.

- Franchino, Fabio (2005). ‘A Formal Model of Delegation in the European Union’, Journal of Theoretical Politics, 17:2, 217–47.

- Franchino, Fabio (2007). The Powers of the Union: Delegation in the EU. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giger, Nathalie, and Heike Klüver (2016). ‘Voting against Your Constituents? How Lobbying Affects Representation’, American Journal of Political Science, 60:1, 190–205.

- Gilens, Martin (2012). Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gilens, Martin, and Benjamin I. Page (2014). ‘Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens’, Perspectives on Politics, 12:3, 564–81.

- Giurcanu, Magda, and Petia Kostadinova (2022). ‘A Responsive Relationship? Setting the Political Agenda in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 29:9, 1474–92.

- Haag, Maximilian (2022). ‘Bargaining Power in Informal Trilogues: Intra-Institutional Preference Cohesion and Inter-Institutional Bargaining Success’, European Union Politics, 23:2, 330–50.

- Hagemann, Sara, Sara B. Hobolt, and Christopher Wratil (2017). ‘Government Responsiveness in the European Union: Evidence from Council Voting’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 850–76.

- Hartlapp, Miriam, Julia Metz, and Christian Rauh (2014). Which Policy for Europe?: Power and Conflict inside the European Commission. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hastie, Trevor, Robert Tibshirani, and Jerome Friedman (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. New York: Springer.

- Haverland, Markus, Minou de Ruiter, and Steven Van de Walle (2018). ‘Agenda-Setting by the European Commission. Seeking Public Opinion?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:3, 327–45.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Christopher Wratil (2020). ‘Contestation and Responsiveness in EU Council Deliberations’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:3, 362–81.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Mark, Tobias Lenz, Jeanine Bezuijen, Besir Ceka, and Svet Derderyan (2017). Measuring International Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume III. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2016). Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Judge, Andrew, and Robert Thomson (2019). ‘The Responsiveness of Legislative Actors to Stakeholders’ Demands in the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:5, 676–95.

- Klüver, Heike (2011). ‘Lobbying in Coalitions: Interest Group Influence on European Union Policy-Making’, in Nuffield’s Working Papers Series in Politics, available at https://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/politics/papers/2011/Heike%20Kluever_working%20paper_2011_04.pdf (accessed 22 February 2023).

- Klüver, Heike, and Iñaki Sagarzazu (2013). ‘Ideological Congruency and Decision-Making Speed: The Effect of Partisanship across European Union Institutions’, European Union Politics, 14:3, 388–407.

- König, Thomas, and Mirja Pöter (2001). ‘Examining the EU Legislative Process: The Relative Importance of Agenda and Veto Power’, European Union Politics, 2:3, 329–51.

- Koop, Christel, Christine Reh, and Edoardo Bressanelli (2022). ‘Agenda-Setting under Pressure: Does Domestic Politics Influence the European Commission?’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:1, 46–66.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter (2007). ‘The Role of European Integration in National Election Campaigns’, European Union Politics, 8:1, 83–108.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Swen Hutter (2019). ‘Politicizing Europe in Times of Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 996–1017.

- Lax, Jeffrey R., and Justin H. Phillips (2009). ‘Gay Rights in the States: Public Opinion and Policy Responsiveness’, American Political Science Review, 103:3, 367–86.

- Lax, Jeffrey R., and Justin H. Phillips (2012). ‘The Democratic Deficit in the States’, American Journal of Political Science, 56:1, 148–66.

- Lo, James (2013). ‘An Electoral Connection in European Parliament Voting’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 38:4, 439–60.

- Lowe, Will, Kenneth Benoit, Slava Mikhaylov, and Michael Laver (2011). ‘Scaling Policy Preferences from Coded Political Texts’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 36:1, 123–55.

- MacKuen, Michael, Jennifer Wolak, Luke Keele, and George E. Marcus (2010). ‘Civic Engagements: Resolute Partisanship or Reflective Deliberation’, American Journal of Political Science, 54:2, 440–58.

- Majone, Giandomenico, ed. (1996). Regulating Europe. New York: Routledge.

- Migliorati, Marta (2021). ‘Where Does Implementation Lie? Assessing the Determinants of Delegation and Discretion in Post-Maastricht European Union’, Journal of Public Policy, 41:3, 489–514.

- Page, Benjamin I., and Robert Y. Shapiro (1983). ‘Effects of Public Opinion on Policy’, American Political Science Review, 77:1, 175–90.

- Papke, Leslie E., and Jeffrey M. Wooldridge (1996). ‘Econometric Methods for Fractional Response Variables with an Application to 401(k) Plan Participation Rates’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11:6, 619–32.

- Pennock, J. Roland (1952). ‘Responsiveness, Responsibility, and Majority Rule’, American Political Science Review, 46:3, 790–807.

- Rauh, Christian (2016). A Responsive Technocracy?: EU Politicisation and the Consumer Policies of the European Commission. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Rauh, Christian (2019). ‘EU Politicization and Policy Initiatives of the European Commission: The Case of Consumer Policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:3, 344–65.

- Rauh, Christian (2021). ‘One Agenda-Setter or Many? The Varying Success of Policy Initiatives by Individual Directorates-General of the European Commission 1994–2016’, European Union Politics, 22:1, 3–24.

- Reh, Christine, Edoardo Bressanelli, and Christel Koop (2020). ‘Responsive Withdrawal? The Politics of EU Agenda-Setting’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:3, 419–38.

- Schaffer, Lena Maria, Bianca Oehl, and Thomas Bernauer (2022). ‘Are Policymakers Responsive to Public Demand in Climate Politics?’, Journal of Public Policy, 42:1, 136–64.

- Schmitter, Philippe C. (1969). ‘Three Neo-Functional Hypotheses about International Integration’, International Organization, 23:1, 161–6.

- Schneider, Christina J. (2019a). ‘Public Commitments as Signals of Responsiveness in the European Union’, The Journal of Politics, 82:1, 329–44.

- Schneider, Christina J. (2019b). The Responsive Union: National Elections and European Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Somer, Murat, and Jennifer McCoy (2018). ‘Déjà vu? Polarization and Endangered Democracies in the 21st Century’, American Behavioral Scientist, 62:1, 3–15.

- Tallberg, Jonas, and Michael Zürn (2019). ‘The Legitimacy and Legitimation of International Organizations: Introduction and Framework’, The Review of International Organizations, 14:4, 581–606.

- Thomson, Robert (2011). Resolving Controversy in the European Union: Legislative Decision-Making before and after Enlargement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Toshkov, Dimiter, Lars Mäder, and Anne Rasmussen (2020). ‘Party Government and Policy Responsiveness. Evidence from Three Parliamentary Democracies’, Journal of Public Policy, 40:2, 329–47.

- Tsebelis, George, and Geoffrey Garrett (2000). ‘Legislative Politics in the European Union’, European Union Politics, 1:1, 9–36.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart J. (2020). ‘The Impact of EU Intervention on Political Parties’ Politicisation of Europe following the Financial Crisis’, West European Politics, 43:4, 894–918.

- Van Ballaert, Bart (2017). ‘The European Commission’s Use of Consultation during Policy Formulation: The Effects of Policy Characteristics’, European Union Politics, 18:3, 406–23.

- Volkens, Andrea, Tobias Burst, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, Bernhard Weßels, and Lisa Zehnter (2020). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2020a [Dataset]. Retrieved from https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/datasets/MPDS2020a

- von der Leyen, Ursula (2022). Speech by the President: Conference on the Future of Europe. Speech by President von der Leyen at the Closing Event of the Conference on the Future of Europe, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_22_2944 (accessed 12 May 2022).

- Warntjen, Andreas, Simon Hix, and Christophe Crombez (2008). ‘The Party Political Make-Up of EU Legislative Bodies’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15:8, 1243–53.

- Williams, Christopher J., and Shaun Bevan (2019). ‘The Effect of Public Attitudes toward the European Union on European Commission Policy Activity’, European Union Politics, 20:4, 608–28.

- Wratil, Christopher (2018). ‘Modes of Government Responsiveness in the European Union: Evidence from Council Negotiation Positions’, European Union Politics, 19:1, 52–74.

- Wratil, Christopher (2019). ‘Territorial Representation and the Opinion–Policy Linkage: Evidence from the European Union’, American Journal of Political Science, 63:1, 197–211.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, Jørgen Bølstad, and Maurits J. Meijers (2019). ‘Understanding Responsiveness in European Union Politics: Introducing the Debate’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:11, 1715–23.

- Zürn, Michael (2014). ‘The Politicization of World Politics and Its Effects: Eight Propositions’, European Political Science Review, 6:1, 47–71.