Abstract

The European Union (EU) is now borrowing on the scale of a large state to address challenges ranging from COVID-19 to the war in Ukraine. However, there has been limited comparative research on how pan-European borrowers can and should be held to account. This article offers a normative justification for why such borrowing should be accountable before showing how accountability practices diverge from a set of accountability expectations derived from three baseline theories: liberal intergovernmentalism, sociological institutionalism and historical institutionalism. Through elite interviews and online archival analysis, we show that the vertical accountability of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank and the European Stability Mechanism to national parliaments in six EU member states varies. Our findings also show that horizontal accountability has been constrained by the European Parliament’s limited involvement in borrowing decisions until recently and that patchy interest from national auditors has undermined diagonal accountability. As EU borrowing increases in importance, these accountability gaps urgently need to be filled.

In May 2022, the European Commission announced €9 billion in so-called Macro-Financial Assistance to Ukraine to help with its acute financing needs after Russia invaded three months earlier (European Commission Citation2022a).Footnote1 By the end of the year, Ukraine had received only two-thirds of this funding, leading to urgent pleas from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for the European Union (EU) to honour its financial commitments (Liboreiro Citation2022). In July of the same year, the European Investment Bank (EIB) promised to revisit its lending policy following criticisms from environmental groups about its funding of new motorways despite the Bank’s pledges on climate change (Hancock Citation2022). In November, the Spanish government was criticised by business groups for being too slow to distribute grants and loans under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (Jopson Citation2022).

These incidents and others like them underscore not only the growing prominence of pan-European borrowers – that is, public institutions which have recourse to capital markets to finance grants, loans or guarantees to the public and private sectors – but the importance of holding these institutions to account. While scholars have explored the accountability of the EIB (Ban and Seabrooke Citation2017; Hachez and Wouters Citation2012), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (Park Citation2021) and the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and European Stability Mechanism (ESM) (Howarth and Spendzharova Citation2019), there is very little comparative analysis of the accountability of these pan-European borrowers to governments, parliaments and auditors. Nor until relatively recently has there been much scholarly interest in the borrowing activities of the Commission (Fromage and Markakis Citation2022), which issued €120 billion in new debt 2022 (European Commission Citation2023). This article compares the accountability of the Commission, the EBRD, the EIB and the ESM and asks whether expectations about how these borrowers will be held to account are met in practice.

The theoretical contribution of this article is two-fold. Firstly, we offer a normative perspective on why EU borrowing takes the Union further beyond its foundations as a regulatory state into the realms of allocation, distribution, and stabilisation (Majone Citation1994, Citation2014). The potential for these policy functions to create winners and losers, and the risks involved in EU debt management, warrants a high degree of accountability, we contend. Secondly, we combine Boven’s (2007) classic distinction between vertical, horizontal, and diagonal accountability with three widely applied approaches to the study of European integration to derive a set of theoretical expectations about how different types of pan-European borrowers will be held to account. Liberal intergovernmentalism would expect the EIB, EBRD and ESM, as intergovernmental borrowers, to be subject to a high degree of vertical accountability to national parliaments. Sociological institutionalism posits that the Commission, as a supranational borrower, will face a high degree of horizontal accountability from the European Parliament (EP). Historical institutionalism, finally, would look to the European Court of Auditors to subject the Commission to a high degree of diagonal accountability and for national auditors to do the same for intergovernmental borrowers.

Through elite interviews and a systematic analysis of parliamentary archives and the work of auditors at EU level and in six member states, our empirical findings show that accountability practices depart from these theoretical expectations to a significant degree. The vertical accountability of the intergovernmental EIB, the EBRD and the ESM to national parliaments varies among member states and borrowers. The horizontal accountability of the supranational Commission to the EP is much greater for some borrowing instruments than others. The European Court of Auditors is paying growing attention to Commission borrowing, but national auditing bodies’ lack of interest in the EIB and EBRD is undermining diagonal accountability. These findings point towards the need for more robust accountability mechanisms as pan-European borrowing grows in importance.

The remainder of this article is divided into five sections. The first explores the normative case for holding pan-European borrowers to account and considers the dimensions along which their accountability is expected to vary. The second, third and fourth sections present empirical evidence on the horizontal, vertical and diagonal accountability of these institutions. The fifth section summarises our main findings and offers thoughts on the strengthening of accountability practices in this domain.

Theorising the accountability of pan-European borrowers

The focus of this article is on four active pan-European borrowers (see in the Appendix). Established in 1957, the EIB provides grants, loans and guarantees to the public and private sectors to contribute to the balanced and steady development of the European internal market. The EBRD was established in 1990 to support economic transition and private enterprise in Central and Eastern Europe’s new democracies. Although it is not an EU institution, the Bank counts the EU, its member states and the EIB as majority shareholders and is a central part of the Union’s so-called Team Europe approach to international development finance (Hodson and Howarth Citation2023). The ESM was established in October 2012 to provide financial assistance to member states facing fiscal or financial crises. The Commission is currently responsible for four borrowing instruments.Footnote2 The Balance of Payments Assistance Facility provides loans to non-eurozone members facing serious balance of payments difficulties. The European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism provides similar support to eurozone members, while Macro-Financial Assistance has done the same for third countries since 1990. The Recovery and Resilience Facility allows the Commission to borrow up to €750 billion to aid member states’ recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic with a particular emphasis on fostering resilience and supporting the green and digital transition.

Accountability refers to the presence of robust mechanisms for preventing the abuse of power (Przeworski et al. Citation1999). Following Lastra and Shams (Citation2001: 167), we think of public accountability as the obligation placed on institutions (‘the accountable’) by another body (‘the accountee’) to justify their actions and accept responsibility for any shortcomings. Accountability is a desirable (and defining) feature of all systems of democratic governance, but it has a specific significance at the European level given the extensive authority invested in the EU compared to other international organisations and perennial debates over the Union’s democratic deficit (Follesdal and Hix Citation2006; Moravcsik Citation2002). Accountability is related to but not synonymous with legitimacy. Schmidt (Citation2020), for example, thinks of accountability as a key criterion of ‘throughput legitimacy’ alongside efficacy, inclusiveness, participation and openness. In this section, we consider the normative case for holding pan-European borrowers to account before outlining theoretical expectations about how intergovernmental and supranational borrowers will be held to account.

The case for accountability in pan-European borrowing

Whether EU institutions should be held accountable depends – from a normative perspective – on the functions assigned to these bodies. In the regulatory domain, there are well-known efficiency arguments for the Commission’s high degree of independence from national governments (Majone Citation1994). Like taxation and expenditure, pan-European borrowing is concerned with allocation and distribution functions, which raise questions of equity and justice and so warrant a high degree of accountability to citizens and elected representatives.Footnote3 The EIB’s early borrowing operations, for example, focused on regional development but they have since expanded to include large-scale investment in transport, urban development, and projects dedicated to climate action and environmental sustainability (Clifton, Díaz-Fuentes and Gómez Citation2018). Such task expansion, which helped the EIB become the world’s largest multilateral lender, underlines the importance of holding the Bank to account.

Pan-European borrowing also touches upon stabilisation, a function that is central to national governments’ core state powers over fiscal policy (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014). For this reason, a pan-European borrowing instrument that engages in stabilisation or constrains governments’ ability to smooth the business cycle will necessitate a high degree of accountability to governments to keep the Union’s fiscal powers in check. Together, the EFSM, EFSF and ESM provided more than €500 billion in loans to five EU member states during the euro crisis. The deep expenditure cuts and painful economic reforms required as a condition of this financial assistance produced a stark warning from Majone (Citation2014) about how far EU institutions had strayed beyond their traditional role in regulation.

Alongside the functions assigned to pan-European borrowers, we see two reasons why such bodies should be accountable. Firstly, pan-European borrowing creates liabilities, whether in the form of callable capital that member state shareholders have subscribed but not paid into the EIB, EBRD and ESM, or the guarantee provided by the EU budget to the Recovery and Resilience Facility or similar borrowing instruments. However unlikely defaults on EIB, EBRD and ESM loans might be, the mere possibility that liabilities will come due creates a need for accountability.Footnote4 Secondly, the Commission’s evolving approach to debt management warrants careful oversight. Traditionally, the Commission’s borrowing instruments relied on back-to-back funding, meaning that the costs of pan-European borrowing were passed onto the recipients of loans. Under a new funding strategy unveiled in December 2022, the Commission now issues single-branded bonds covering all borrowing instruments (European Commission Citation2022b). While there are efficiency arguments for this change, it brings new risk exposures, as evidenced by the rising yields on 20-year EU bonds in Autumn 2022 (Pop Citation2022).

Expected accountability mechanisms

Overall, we see a strong normative case for holding pan-European borrowers to account, but that does not mean that all borrowers can or should be subject to the same forms of accountability. We distinguish in this article between two types of pan-European borrower – intergovernmental and supranational – and three modes of accountability – horizontal, vertical and diagonal. Although their governance structures are not identical, the EIB, ESM and EBRD are all resolutely intergovernmental since none can act without the express approval of national government representatives. The senior leadership of supranational borrowers is appointed by EU member states, but thereafter is operationally independent. The Commission comfortably meets this definition in so far as the Treaty on European Union prohibits Commissioners from seeking or taking instruction from any Government or other institution, body, office or entity.Footnote5 Building upon Bovens (Citation2007), we use the term vertical accountability to describe the obligations placed on pan-European borrowers by national parliaments. Horizontal accountability focuses instead on the European Parliament’s role as a pan-European accountee, while diagonal accountability captures the obligations placed on borrowers by national auditors and the European Court of Auditors.

Rather than presenting a single theoretical perspective on the vertical, horizontal and diagonal accountability of intergovernmental and supranational borrowers, we draw out expectations about how different types of borrowers will be held to account using three baseline approaches to the study of European integration: liberal intergovernmentalism, sociological institutionalism and historical institutionalism. There are, of course, many other theories to choose from, but those explored here cover the three (original) new institutionalisms and give rise to clear expectations about how the institutions we are interested in should be held to account (Hall and Taylor Citation1996).

Liberal intergovernmentalism thinks of governments as driving key decisions on European integration, but it also expects national representatives to be subject to a high degree of vertical accountability. Early work on liberal intergovernmentalism saw national parliaments as removed from EU decision-making (Moravcsik Citation1993: 515), while more recent contributions reject claims that the Union suffers from a democratic deficit (Moravcsik Citation2018: 1668). Such scepticism about the democratic deficit is premised on the idea that national parliaments are part of the ‘transmission belt’ linking societal interests over EU policies to intergovernmental preferences (Hix Citation2018: 1598). Moravcsik (Citation2002: 611) puts the same point differently when he describes the European constitutional settlement as being founded on ‘democratic control over national governments’.

National parliaments are the most important mechanism of democratic control, and hence vertical accountability, from a liberal intergovernmental perspective. Member state legislatures can and do hold supranational institutions to account, most noticeably through the Lisbon Treaty’s reasoned opinion procedure and public hearings with Commission officials (Crum and Oleart Citation2022). Given the hierarchical relationship between national parliaments and governments, however, liberal intergovernmentalism would expect vertical accountability to be considerably stronger for intergovernmental borrowers.

Moravcsik (Citation1993: 506) originally described the empowerment of the EP as symbolic, but he subsequently acknowledged the EU legislature’s role, alongside national governments, in ensuring ‘that EU policy-making is, in nearly all cases, clean, transparent, effective and politically responsive to the demands of European citizens’ (Moravcsik Citation2002: 605). Whereas liberal intergovernmentalism thus appears to be in two minds about whether the Commission, as the EU's sole supranational borrower, will face a high degree of horizontal accountability from the EP, Rittberger’s (Citation2014) sociological institutionalist approach offers two clear-cut reasons as to why this should be the case. His legitimacy-seeking hypothesis assumes that member states and EU institutions share standards of legitimacy such that the delegation of significant new powers to supranational institutions will be accompanied by a greater role for the EP, as exemplified by the budgetary powers acquired by the European legislature in the 1970s. Rittberger’s interinstitutional bargaining hypothesis assumes that the EP will leverage its participation in negotiations over the empowerment of new institutions to seek a role for itself, as attested by the EP’s insistence on creating an Economic Dialogue in negotiations over the Six Pack. Taken together, these hypotheses suggest that either member states or the EP will push for greater horizontal accountability as the Commission’s borrowing powers grow.

Laffan (Citation1999) offers an influential historical institutionalist account of auditing practices in the EU that can usefully be applied to pan-European borrowing. Historically, the European Commission and EIB sought to defend their financial autonomy, but the EP has been a powerful champion of the European Court of Auditors, Laffan (Citation1999: 259) argues. Such support reflects the crucial importance of auditing reports as ‘raw material’ in parliamentary efforts at financial control (Laffan Citation1999: 261). Building on this approach, we would expect the EP to demand a prominent role for the European Court of Auditors in holding the Commission to account as a borrower and for national parliaments to seek a similar role for national auditors in relation to the EBRD, EIB and the ESM.

Laffan (Citation1999: 261) sees the protection of turf as another driver of auditing norms in the EU. Historical institutionalism would expect auditing bodies to protect their credibility and bureaucratic turf by actively seeking to hold borrowing institutions to account. National auditing bodies have paid close attention to the Commission’s financial activities since the establishment of the Contact Committee in 1960 but their primary focus is likely to be on national governments’ relationship with intergovernmental bodies. As the Community’s financial watchdog since 1977, the European Court of Auditors will have Commission borrowing in its sights. Historical institutionalism thus expects parliaments and auditors themselves to demand a high degree of diagonal accountability for both intergovernmental and supranational borrowers for reasons of self-interest or because of professional norms.

Vertical accountability

National parliaments can exercise vertical accountability over pan-European borrowers in two principal ways. The first is by holding their own governments to account for their voting decisions as Directors or Governors, an option that evidently applies only to intergovernmental institutions. The second is by inviting representatives of the borrowing institution to appear before select committees. To study the vertical accountability of pan-European borrowers, we compare national parliaments’ relationship with the EIB, ESM and EBRD in six countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. As the six founding member states of the European Community, these countries have the longest involvement with pan-European borrowing. Drawing on official documentation and the parliaments’ websites, we present evidence on the institutional arrangements for vertical accountability, the number of questions about pan-European borrowers asked by members of parliament (MPs) and the number of parliamentary hearings held with the senior officials from the institutions in question. To corroborate our understanding, we relied on eleven semi-structured interviews with officials from national finance ministries, national auditing bodies and the European Court of Auditors (see Appendix for a full list). Accountability practices via both channels are variable and at odds with our accountability expectations, we show in this section. Some national parliaments take more interest in pan-European borrowing than others and all show greater interest in some borrowers than others. The result is that vertical accountability is not as straightforward as liberal intergovernmentalism would expect.

National parliaments’ participation rights related to ESM decisions vary. Only the parliaments of Austria, Estonia, Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands take formal votes on each financial assistance package and can thereby, in theory, block a programme (Höing Citation2015: 50–8).Footnote6 Other national parliaments rely on much weaker forms of vertical accountability and most parliaments are regularly informed about the ESM (Höing Citation2015: 58). The French Parliament, for example, receives a report on the financial situation of the ESM three times per year and whenever the ESM Governing Council takes far-reaching decisions (Höing Citation2015: 255). The Dutch Ministry of Finance informs the Tweede Kamer in writing after each meeting of the EBRD, EIB, and ESM’s Board of Governors, but the government rarely faces parliamentary hearings on these borrowers (Tweede Kamer Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Similar differences exist in the procedures for capital increases at the EIB: while the Bundestag had to pass a new law to authorise the government to approve the EIB’s capital increase and changes in the Bank’s statutes in 2019 (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2019), the Tweede Kamer was merely informed about the decision when the additional guarantees were included in the budget (Tweede Kamer Citation2018a).

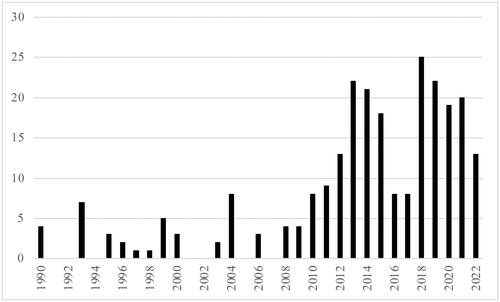

Most legislatures rely on parliamentary questions to highlight specific concerns about the actions or perceived shortcomings of pan-European borrowers. As shows, the total number of questions asked by national parliamentarians in the European Community’s six founding members between 1990 and 2022 varies over time. A sharp increase in the number of questions asked after 2010 suggests that the euro crisis led to growing interest in pan-European borrowers, but there are significant differences across borrowers and member states (). National parliamentarians have taken greatest interest in the EIB, which accounts for almost half of all questions. The German Bundestag is the most engaged, accounting for around a quarter of all questions, with more than half of those posed by German parliamentarians focused on the ESM. Members of the Italian Camera dei Deputati asked no questions about the ESM, even though Italy accounts for almost 17% of this borrower’s subscribed capital.

Figure 1. Total parliamentary questions (1990–2022).

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on data gathered from national parliaments’ websites. For bicameral parliaments, we focus on the lower house.

Table 1. Parliamentary questions by chamber/parliament and borrower (1990–2022).

Our analysis of these parliamentary questions and elite interviews indicate that MPs typically ask about their government’s intentions or voting record for individual funding projects, notably about nuclear energy, agricultural, and environmental projects. In a few cases, MPs have also followed up on government answers or pursued the same issue over time (Tweede Kamer Citation2018b, Citation2020). Overall, however, this scrutiny has remained uneven, and many questions appear to have been asked in response to media coverage and with a view to generating media attention (Interview 1), rather than as part of systematic oversight of the government’s activities as a shareholder (Interviews 1 and 2).

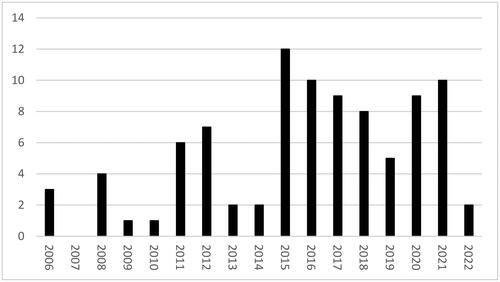

National parliamentary committees also pose questions directly to representatives of pan-European borrowers. shows that the total number of hearings in the parliaments of the European Community’s six founding members has increased overall between 2005 and 2022, with sharp increases noticable during the global financial crisis, the euro crisis and COVID-19. There is, once again, considerable variation across borrowers and member states (). The German Bundestag is responsible for most hearings, with two thirds of these focused on the Commission rather than intergovernmental borrowers. This finding is at odds with liberal intergovernmentalism, as is the fact that members of the French Assemblée nationale held sixteen out of eighteen hearings on the Commission and none on the EBRD or ESM.

Figure 2. Total parliamentary hearings per year.

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on data gathered from national parliaments’ websites. For bicameral parliaments, we focus on the lower house.

Table 2. Parliamentary hearings by chamber/parliament and borrower (2006–2022).

Among intergovernmental borrowers, the EIB and the ESM have attracted most attention from national parliamentary committees (). Parliamentary questions on the EIB are rare in the Netherlands, perhaps because it is seen as an established institution (Interviews 1 and 3, 2023). Nevertheless, the mere possibility that MPs might scrutinise investment decisions acts as a form of parliamentary control (Interview 4, 2023). Former ESM Managing Director Klaus Regling and several ESM officials frequently appeared before national parliaments (Howarth and Spendzharova, Citation2019: 903). However, we found that most visits were to Germany – the Bundestag’s budget committee alone summoned Regling, a former German civil servant, four times.

Horizontal accountability

In order to analyse the horizontal accountability of EU borrowing, we systematically searched the EP's website for hearings related to the Commission’s current borrowing instruments: the Balance of Payments Assistance Facility, the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism, Macro-Financial Assistance and the Recovery and Resilience Facility. We also compared accountability provisions in the legal basis for these borrowing instruments using EUR-Lex, and corroborated our findings, once again, via the elite interviews listed in the Appendix. For the sake of comparison, we present evidence on the EP's attempts to hold intergovernmental borrowers to account. The EP’s dialogue with the EIB and ESM has gone further than expected but only marginally so, we find.

The EP and the Commission as a borrower

In line with sociological institutionalist expectations, the EP has sought to hold the Commission to account from the earliest days of the latter’s borrowing activities. It is only recently, however, that the EP has succeeded in establishing meaningful accountability mechanisms. The result is that the horizontal accountability of supranational pan-European borrowing remains underdeveloped.

When Community borrowing and loan instruments were created in the 1970s, they were kept outside the Community budget. This hindered political control, argued the EP, which repeatedly called for a new part of the Community budget dedicated specifically to borrowing and lending (Irmer Citation1981). The Council rebuffed such requests, but the Commission agreed to submit an annual report on its borrowing and lending operations to the Council and EP from 1980 (Vitsentzatos Citation2014: 138–9).

The EP plays no formal accountability role in relation to the Balance of Payments Assistance Facility and the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism. In contrast, the release of Macro-Financial Assistance funds is dependent on the approval of the EP (and the Council) of the Union’s budget for that year. The Commission is also routinely required to report to the EP each year on the implementation of Macro-Financial Assistance programmes for third countries and to submit an ex-post evaluation report to MEPs after programmes come to an end. There is no evidence to suggest that either the Commission or member states are more concerned with enhancing the legitimacy of borrowing which concerns third countries. Inter-institutional politics provides a much more plausible explanation in this case. Articles 143 and 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which underpin the Balance of Payments Assistance Facility and the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism respectively, assign no role to the EP. Under Article 212 TFEU, as introduced by the Lisbon Treaty, each instance of Macro-Financial Assistance is based on a regulation adopted by the EP and the Council by means of the Ordinary Legislative Procedure.Footnote7 From the moment the Lisbon Treaty entered into force, the EP used its seat at the table to insist on a role for itself in the horizontal accountability of Macro-Financial Assistance.

The Recovery and Resilience Facility comes with the most extensive mechanisms of horizontal accountability over Commission borrowing to date. Under the regulation establishing this borrowing instrument, the Commission is legally required to provide detailed information to the EP, as well as to the Council, on how funds raised under Next Generation EU are spent, including the specifics of grants and loans to member states. After the Commission reformed its borrowing operations in 2022,Footnote8 an amendment to the EU Financial Regulation obliged the Commission to ‘regularly and comprehensively inform the EP and the Council about all aspects of its borrowing and debt management strategy’.Footnote9 The first hearing on the Commission’s borrowing plans was held in the EP Committee on Budgets in January 2023 (European Parliament Citation2023). While this still does not amount to full inclusion in the EU budget, as borrowing volumes and expenses are still not authorised ex-ante, these changes signify a considerable improvement of the EP’s oversight as Commission borrowing expanded in volume.

The Commission is also required to account for its decisions under the Recovery and Resilience Facility. The EP holds bi-monthly Recovery and Resilience Dialogues with the Commission (Dias Pinheiro and Dias Citation2022). These hearings can cover a broad range of issues, including ‘the recovery, resilience and adjustment capacity’ within the EU, member state recovery and resilience plans and their assessment, and any termination of payment related to their non-fulfilment.Footnote10 To facilitate this dialogue, the EP set up a Recovery and Resilience Fund Working Group comprised chiefly of members of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs and the Committee on Budgets. As of February 2024, 14 Recovery and Resilience Dialogues had taken place.

The EP’s growing role in horizontal accountability is consistent with Rittberger’s (Citation2014) institutional bargaining hypothesis. The Recovery and Resilience Facility Regulation is based on Articles 147, 174 and 175 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which provide the EP with a substantive role in this policy domain. Article 122, under which the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism was created, does not.Footnote11 We see little evidence in support of the legitimacy-enhancing hypothesis.

The EP and intergovernmental borrowers

Neither sociological institutionalism nor liberal intergovernmentalism would expect the EP to play a prominent role in holding intergovernmental borrowers to account. For sociological institutionalism, the EP can neither use the empowerment of supranational bodies to justify a role for itself nor likely leverage its positions in negotiations to secure meaningful accountability mechanisms. Liberal intergovernmentalism, as already noted, would expect the accountability of intergovernmental borrowers to run through national parliaments. The fact that the EP has held debates with EBRD officials on only two occasions is consistent with these expectations.Footnote12 In 2002, after a speech by EBRD President Lemierre, the EP passed a report on the EBRD’s track record (European Parliament Citation2002). In 2011, the EP tied its agreement to a capital increase at the EBRD to demands for greater EBRD accountability, including a Commission report assessing the effectiveness of the existing system of European public financing institutions, and an annual report to the EP from the EU’s EBRD Governor.Footnote13 The Commission produced its one (and to date only) report in response to this request in 2016 (European Commission Citation2016).

The EP has been more proactive about trying to hold the EIB and ESM to account, although attempts to establish formal mechanisms of accountability have fallen short. In a series of reports since the 1980s,Footnote14 the EP called for more political control over the EIB’s borrowing and lending and criticised the Bank’s lack of accountability (Laffan Citation1997: 222–3). In its submission to the Intergovernmental Conference of 1996, for instance, the EP directly called for ‘increased accountability’ of the EIB, including judicial review by the European Court of Justice, auditing by the Court of Auditors, and regular reports to the Council and the EP (European Parliament Citation1995). The EIB responded to this criticism in 2002 by holding voluntary hearings with MEPs (Interview 5, 2022) despite its proven fear that some investment projects would be politicised and notably by Green MEPs (Interview 10, 2024).

Cooperation between the EIB and the EP has become more frequent over time. The EP adopts two comprehensive reports on the EIB each year: one on the EIB’s Financial Activities by the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee and the other on the Control of the EIB’s Financial Activities by the Committee on Budget. Both reports are debated in a plenary session where MEPs can address questions to the EIB’s President. Additionally, senior EIB staff attend ad hoc hearings in the EP (European Parliament Citation2020). Although the EP is unable to sanction the EIB, the Bank’s decision to submit to this scrutiny suggests that engaging with the Parliament is considered desirable, at least from a reputational perspective.

Whereas the EP lacks formal oversight procedures over the ESM (Dias and Zoppè Citation2019),Footnote15 in practice, the ESM has been willing to engage with the EP. Harald Noack, the European Court of Auditor’s member on the ESM’s Audit Committee stated in 2012 that he would keep the EP informed and make himself available for parliamentary hearings (Carotti Citation2012). ESM President Klaus Regling was also open to cooperating with the EP and attended two hearings in the EP’s ECON Committee in 2013 and 2014 (Dias and Zoppè Citation2019; European Parliament Citation2013, Citation2014a).

Both the EP and the Commission wanted the ESM to be integrated into the EU’s legal order and to be made more accountable. The European Parliament (Citation2014b: 112) pushed for the creation of an interinstitutional agreement to ensure ESM accountability and the Commission in 2017 proposed the transformation of the ESM into a European Monetary Fund (European Commission Citation2017). ESM Managing Director Regling (Citation2019) had also suggested that the ESM could be given a similar status in the EU legal order as the EIB. Yet, when the ESM’s member state shareholders reformed the ESM Treaty in 2021, they affirmed its intergovernmental character and left its accountability arrangements largely unchanged. Recital 7 of the draft reformed treaty merely ‘acknowledges the current dialogue [with] the EP’.Footnote16

Diagonal accountability

As highlighted by Bovens (Citation2007: 108), ‘public institutions are frequently required to account for their conduct to various forums in a variety of ways’. In the presence of political fora such as national parliaments or the EP, it is possible to speak of political accountability. If, instead, the forum performs independent scrutiny, as is the case with national audit bodies and the European Court of Auditors, accountability is administrative (Bovens Citation2007). Their technocratic nature notwithstanding, administrative fora like national audit bodies and the European Court of Auditors can be helpful to enhance democratic control over pan-European public borrowing, provided that their reports are picked up by parliaments. Hence, although it could be seen as an ‘auxillary’ forum of accountability (Bovens Citation2007: 110), diagonal accountability matters because it provides a series of controls – both at the national and European level – that helps to scrutinise pan-European borrowers. To explore the diagonal accountability of EU borrowing, we accessed the websites and online archives of national courts of auditors and the European Court of Auditors to understand their interaction with pan-European borrowers, and cross-checked our findings with the elite interviews listed in the Appendix. Our findings show that the European Court of Auditors is now paying greater attention to Commission borrowing, but that the former has been kept at arm’s length from intergovernmental borrowers. National auditors have concentrated more on the ESM than the EIB and EBRD, further limiting diagonal accountability.

National auditing bodies

Historical institutionalism, as noted above, expects a high degree of diagonal accountability for intergovernmental borrowers either because auditors seek to protect their bureaucratic turf or because parliamentarians demand it. Most national audit bodies seem indifferent to the EIB and EBRD. An exception is the Italian Corte dei Conti (Citation2022), which regularly reports on Italy’s use of European funds, including those provided by the EIB. Given that the Corte only states the amount of funds received from the EIB but does not specify how they were spent, these reports do not scrutinise the use of EIB funds by Italy or their financial reporting.

By contrast, the ESM has, from the moment of its creation, attracted the attention of national auditors. When in 2011 Dutch and German auditors voiced their concerns over the weak auditing provisions in the draft ESM Treaty, the German court of auditors, the Bundesrechnungshof, hosted a conference about the issue (Stuiveling and van Schoten Citation2012). Just a month later, the Contact Committee of the Supreme Audit Institutions of the European Union proposed a joint amendment to the ESM Treaty calling for the creation of an independent Board of Auditors (Contact Committee Citation2011).

The Bundesrechnungshof continued to keep a close eye on the ESM’s Board of Auditors. The German audit body’s president, Ulrich Graf, was one of the five original members of the Board and the Bundesrechnungshof provided two temporary staff to assist the audit committee. The Dutch court of auditors Algemene Rekenkamer (Citation2015), produced the first external review of the EU’s emergency funds in 2015, criticising the lack of democratic control over the ESM’s activities and the lack of evaluation procedures. Given that Dutch finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem chaired the ESM’s Council of Governors at the time, the Algemene Rekenkamer’s recommendations were taken up in the ESM’s Transparency Initiative and received a response in 2017,Footnote17 which noted that the ESM had commissioned an external evaluation report and that the European Court of Auditors had begun work on an evaluation of financial assistance to Ireland and Portugal (Algemene Rekenkamer Citation2017). Our elite interviews indicate that national auditors – and notably auditors from Northern member states – though they are attentive to any information requests from parliamentarians, are primarily concerned with the ESM's perceived audit gap (Interview 9, 2023). This justification is consistent with historical institutionalism’s expectation that a concern for bureaucratic turf will drive diagonal accountability.

National audit bodies have also shown increased interest in Commission borrowing for similarly self-interested reasons. The Algemene Rekenkamer, for example, stepped up its examination of EU economic governance during the euro crisis (Interview 6, 2023). In Germany, the Bundesrechnungshof has published two reports on the EU’s response to the pandemic that were critical of European-level borrowing. Its first report argued that the Recovery and Resilience Facility opened the door for debt mutualisation and might be transformed into a permanent instrument (Bundesrechnungshof Citation2021). The second report reviewed the Commission’s practice of funding the Recovery and Resilience Facility partially through green bonds and highlighted the risks of greenwashing (Bundesrechnungshof Citation2022). The Italian Corte dei Conti (Citation2021) was mainly concerned with the national handling of Recovery and Resilience Facility funds. It highlighted the need for sound financial management and the prevention of corruption, as well as the limited absorption capacities of EU funds by domestic public administrations (Corte dei Conti Citation2022). In its 2021 report on the use of EU funds by Italy, the Corte dei Conti (Citation2022) also recalled that funds raised on bond markets within the Recovery and Resilience Facility framework are instances of public debt, albeit of a common European nature. It therefore cautioned against the risk of future debt spirals whereby national (i.e. Italian) public borrowing increases to repay debt jointly issued by the EU.

The European Court of Auditors

The European Court of Auditors has often encountered obstacles in holding EU borrowers to account. The exclusion of early Commission borrowing instruments from the budget prevented the Court from undertaking the oversight role it performs in relation to EU expenditure. Nonetheless, from the 1980s until the 1990s, the European Court of Auditors dedicated a full chapter in its annual report to the Commission’s borrowing operations where European funds went directly into projects.Footnote18 After a series of own-initiative attempts at auditing these projects, the Court, the Commission, and the EIB (which administered the New Community Instrument) concluded the first Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on their cooperation in 1989. The European Court of Auditors (Citation1982, Citation1990) produced two special reports on the Commission’s borrowing activities, in 1982 and 1990.

Subsequent loan instruments and EU budget regulations successively strengthened diagonal scrutiny over Commission borrowing. To the Commission’s initial surprise, the European Court of Auditors decided to produce special reports on the former’s involvement in financial assistance to Greece and other programme countries (Interview 7, 2023). A 2018 revision to the Financial Regulation authorised the Court to conduct checks and audits on funds borrowed by the EU to provide financial assistance to member states.Footnote19 Large-scale Commission borrowing after 2020 led to a further revamp of financial scrutiny. To date, the European Court of Auditors has published four special reports on various aspects of Next Generation EU, including a detailed study of the Recovery and Resilience Facility’s performance monitoring framework (European Court of Auditors Citation2023a). These reports strengthened accountability but added to Commission officials’ already heavy administrative burden under the Facility (Interview 8, 2023).

The EP has called on the European Court of Auditors to make full use of its powers in relation to the Recovery and Resilience Facility (Committee on Budgets and Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs Citation2022), but the main impetus for these reports has come from the European Court of Auditors, which has been vocal in its warnings about the ‘EU-level accountability gap’ in the European Commission’s pandemic response (European Court of Auditors Citation2023b: 4). As in the case of national auditors, the protection of bureaucratic turf appears to be a key driver of diagonal accountability.

The European Court of Auditors does not have binding legal powers; it is dependent to some degree on the good will of the institutions it scrutinises. The EIB fiercely resisted such scrutiny in the 1980s and 1990s (Laffan Citation1997; Skiadas Citation1999). As Laffan (Citation1999: 259) notes, this defensiveness arose from the EIB's desire to protect its clients from EU audits, but the Bank eventually agreed to normalise relations with the Court. After Memorandums of Understanding signed in 1989 and 1992 seemed insufficient, the Amsterdam Treaty finally obliged the EIB to cooperate with the European Court of Auditors.Footnote20 The most recent trilateral Memorandum of Understanding signed in November 2021 (European Investment Bank Citation2021) grants the Court access to EIB documentation and data relating to its activities carried out under the Commission mandate. Although the European Court of Auditors produces regular audits of programmes that are funded through the EU budget but managed by the EIB, it still cannot access information on the EIB’s own activities funded through debt issuance. However, this has not stopped the Court from producing several reports on EIB lending activities, including a very critical special report on the EU’s (and specifically the EIB’s) active encouragement of the use of public-private partnerships (European Court of Auditors Citation2018). Because the ESM is an intergovernmental organisation outside the EU treaties, the EU’s administrative watchdogs have no jurisdiction over this pan-European body. Klaus Regling, as the incoming head of the ESM, inquired with the ECA whether it could audit the mechanism, but he was reportedly turned down for that reason (Interview 11, 2023). The fact that one member of the ESM Board of Auditors comes from the European Court of Auditors makes no difference in this regard (Interview 7, 2023). Similarly, the Court has refrained from commenting on the ESM in its reports on the euro crisis and has not audited any of the EBRD’s activities.Footnote21

Conclusion

Borrowing has always been the second financial arm of the EU (Laffan Citation1997), but it has been significantly strengthened by the Union’s response to the euro crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is unlikely that the EU’s €750 billion pandemic fund will become permanent given the strict sunset clause written into the Recovery and Resilience Facility, it is a safe bet to assume that the EU will continue to borrow on a sizeable scale in response to unfolding challenges. Indeed, at the time of writing, the EU has already scaled up Macro-Financial Assistance to Ukraine and made initial commitments to support the country’s reconstruction that will be difficult to honour without extensive additional borrowing.

This article has argued that the pan-European borrowing activities of the EIB, the EBRD, the ESM and the Commission require a high degree of accountability because they push the EU beyond its roots as a regulatory project into the sensitive domains of allocation, distribution and stabilisation (Majone Citation1994). These fiscal functions raise questions of equity and sovereignty. Moreover, European debt management is not without risks. Consequently, although we acknowledge that not all bodies will (or should) be held to account in the same way, we maintain that pan-European borrowers should be required to explain their decisions and address any shortcomings. Drawing upon liberal intergovernmentalism (Moravcsik Citation2002), sociological institutionalism (Rittberger Citation2014) and historical institutionalism (Laffan Citation1999), we expected accountability to vary according to whether pan-European borrowers are intergovernmental or supranational. Our empirical findings show that accountability practices depart from these accountability expectations to a significant degree.

Liberal intergovernmentalism expects intergovernmental borrowers to be subject to a high degree of vertical accountability to national parliaments. Our findings show that national legislatures’ interest in intergovernmental borrowers is patchy, at best, as illustrated by the German Bundestag, which has done more than most member states to hold the ESM to account, while showing scant interest in the EIB and EBRD. Sociological institutionalism expects the European Commission’s empowerment as a supranational borrower to go hand in hand with greater horizontal accountability to the EP. In reality, the EP has been kept at arm’s length from Commission borrowing instruments until relatively recently. This shifted with Macro Financial Assistance after the Lisbon Treaty and the Recovery and Resilience Facility not because member states saw horizontal accountability as justified in such cases, but because the EP leveraged its role under these instruments. Historical institutionalism expects national auditors and the European Court of Auditors to push for a high degree of diagonal accountability either to protect their bureaucratic turf or at the instigation of parliamentarians. The European Court of Auditors has stepped up its efforts to hold Commission borrowing to account, but national auditing bodies have taken a limited interest in intergovernmental borrowers, with the partial exception of the ESM. National and EU-level auditors’ desire to protect their bureaucratic turf rather than satisfy parliamentarians appears to be the common denominator in both cases.

These gaps between accountability expectations and practices underline the need for more robust controls on EU borrowing. An accountability charter for national parliaments and the EP would help establish clearer expectations about what role elected officials should play in the oversight of intergovernmental and supranational borrowers and ensure greater consistency across institutions and member states. The Contact Group established by national audit bodies in 1960 could perform a similar role for the European Court of Auditors and national courts of auditors, ensuring that the political and administrative accountability of pan-European borrowing goes hand in hand.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to Gijs Jan Brandsma, Richard Crowe, Laura Pierret and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

The authors have neither financial nor non-financial interest arising from the direct application of this research. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dermot Hodson

Dermot Hodson is a Professor at Loughborough University London. He has published widely on EU economic governance and integration in journals such as the Journal of Common Market Studies, the Journal of European Public Policy and the Review of International Political Economy. His latest book is Circle of Stars: A History of the EU and the People Who Made It (Yale University Press). [[email protected]]

David Howarth

David Howarth is a Full Professor at the University of Luxembourg. He has most recently published Bank Politics: Structural Reform in Comparative Perspective (with Scott James, Oxford University Press). He has published in a number of leading journals, including the Journal of European Public Policy, the Review of International Political Economy and World Politics. [[email protected]]

Iacopo Mugnai

Iacopo Mugnai is Postdoctoral Research Associate at Loughborough University London. An expert on European economic governance, he recently completed a PhD at the University of Warwick on the role of ideas within the European Central Bank. His research has been published in Comparative European Politics. [[email protected]]

Lukas Spielberger

Lukas Spielberger is Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Luxembourg. He recently completed his PhD at the University of Leiden on central bank cooperation and swap arrangements. His research has been published in the Journal of European Public Policy and Comparative European Politics. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The Council and EP agreed in December 2022 to provide Ukraine with a new package of €18 billion in loans under the so-called MFA+.

2 The Commission was previously responsible for the Community Loan Mechanism and the New Community Instrument. These borrowing instruments were retired in the 1980s. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Commission took charge of Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) which, from 2020 to the end of 2022 offered €98.4 billion in loans to member states to support short-term work schemes and similar measures for workers and the self-employed.

3 The classic distinction between allocation, distribution and stabilisation is from Musgrave (Citation1956).

4 Belarus became the first borrower to default on an EBRD loan in December 2022.

5 Article 17(3) Treaty on European Union.

6 Dutch participation rights are based on an information protocol between the government and parliament that weakens the legal obligation to hold a debate and grant formal assent to ESM loans (Poppelaars Citation2018). However, only the Bundestag will be able to block an ESM programme under all circumstances (Poppelaars Citation2018). Under a emergency procedure, ESM programmes can be approved by 85% of all votes, which leaves only France, Germany, and Italy with a veto power over ESM lending.

7 Article 212 TFEU.

8 Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2022/2434.

9 Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2018/1046 Art 220.

10 Article 26, Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility, Official Journal L 57, 18.2.2021, p. 17–75.

11 In the case of SURE, which was also based on Article 122, the Commission and the Council side-lined the EP, which issued no reports or opinions (Fasone Citation2022). The intergovernmental structure of SURE was agreed swiftly (Schelkle Citation2021) and gave the EP no tool to hold the Commission accountable (Fasone Citation2022). In December 2020, it was agreed that the EP would be involved in deliberations over the future use of Article 122, albeit it without prejudice to the Council's powers under this treaty provision. See: ‘Joint declaration of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission on budgetary scrutiny of new proposals based on Article 122 TFEU with potential appreciable implications for the Union budget', Official Journal C 444I, 22.12.2020, p. 5–5.

12 Since the EU is an EBRD shareholder, the EP arguably plays an analogous role to national parliaments for this pan-European borrower.

13 Decision 1219/2011/EU.

14 In 1981, the EP’s BUDG Committee asked for a report containing ‘an overall summary of the results of the borrowing and lending policy of the Community, including the EIB’ (Irmer Citation1981).

15 Regulation 472/2013, Art. 3(9) provides the EP with an indirect oversight mechanism whereby it may invite representatives of the Commission, the ECB, the Eurogroup and the IMF to report on programmes in which the ESM is involved.

16 Recital 7, Agreement Amending the Treaty on Establishing the European Stability Mechanism (Citation2021) merely ‘acknowledges the current dialogue [with] the EP’.

17 Interview 7, 2023.

18 The borrowing under the ECSC loan facility was reported separately as the ECSC operational budget remained separate from the other Communities.

19 Regulation 2018/1046, Art 220 and 257 (6). Art 220.5 (d) later became the point of reference for the financial controls under SURE and Recovery and Resilience Facility.

20 Treaty of Amsterdam, Art 188.3 (c).

21 Interview 7, 2023.

References

- Algemene, Rekenkamer (2015). ‘Noodsteun voor eurolanden tijdens de crisis’, Rapport 10/09. Den Haag: Algemene Rekenkamer, available at: https://www.rekenkamer.nl/onderwerpen/europese-unie/documenten/rapporten/2015/09/10/noodsteun-voor-eurolanden-tijdens-de-crisis.

- Algemene, Rekenkamer (2017). ‘Opvolging aanbevelingen Noodsteun voor eurolanden tijdens de crisis’ (peilmoment augustus 2017)', Rapport 28/09. Den Haag: Algemene Rekenkamer, available at: https://www.rekenkamer.nl/onderwerpen/europese-unie/documenten/publicaties/2017/09/28/opvolging-aanbevelingen-noodsteun-voor-eurolanden-tijdens-de-crisis.

- Ban, Cornel, and Lenoard Seabrooke (2017). From Crisis to Stability: How to Make the European Stability Mechanism Transparent and Accountable. Brussels: Transparency International EU.

- Bletzinger, Tilam, William Greif, and Bernd Schwaab (2023). ‘The Safe Asset Potential of EU-Issued Bonds’, VoxEU, 20 January.

- Bovens, Mark (2007). ‘New Forms of Accountability and EU-Governance’, Comparative European Politics, 5:1, 104–20.

- Bundesrechnungshof (2021). ‘Bericht nach § 99 BHO zu den mö glichen Auswirkungen der gemeinschaftlichen Kreditaufnahme der Mitgliedstaaten der Europäischen Union auf den Bundeshaushalt (Wiederaufbaufonds)’, 27/05. Bonn: Bundesrechnungshof.

- Bundesrechnungshof (2022). ‘Bericht nach § 88 Absatz 2 BHO an den Haushaltsausschuss des Deutschen Bundestages zur Finanzierung des Wiederaufbaufonds über grüne Anleihen der Europäischen Union’, 9/06. Bonn: Bundesrechnungshof.

- Carotti, Rosmarie (2012). ‘The European Stability Mechanism and Its Board of Auditors – Interview with Dr Harald Noack, the European Court of Auditors’ Nominee for the Board of Auditors’, Journal: Cour des comptes européennes, 10:12, 5–7.

- Clifton, Judith, Daniel Díaz-Fuentes, and Ana Lara Gómez (2018). ‘The European Investment Bank: Development, Integration, Investment?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:4, 733–50.

- Committee on Budgets and Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (2022). ‘Report on the Implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility’, European Parliament Report A9-0171/2022. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Contact Committee (2011). ‘Resolution on the Statement of SAIs of the Euro Area on the External Audit of the ESM’, CC-R-2011-01. Luxembourg: ECA.

- Corte dei Conti (2021). ‘Recovery Fund e Ruolo della Corte dei Conti’, Rivista della Corte dei Conti. Quaderno No. 1/2021. Roma: Corte dei Conti.

- Corte dei Conti (2022). ‘Relazione Annuale 2021: I rapporti finanziari con l’Unione europea e l’utilizzazione dei Fondi europei’. Roma: Corte dei Conti.

- Crum, Ben, and Alvaro Oleart (2022). ‘Information or Accountability? A Research Agenda on European Commissioners in National Parliaments’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61:3, 853–64.

- Deutscher, Bundestag (2019). ‘Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung’, Drucksache 19/7838. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- Dias, Cristina Sofia, and Alice Zoppè (2019). ‘The European Stability Mechanism: Main Features, Instruments and Accountability’, In Depth Analysis, PE 497.755. Brussels: Directorate General for Internal Policies, European Parliament.

- Dias Pinheiro, Bruno, and Cristina Sofia Dias (2022). ‘Parliaments’ Involvement in the Recovery and Resilience Facility’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 28:3, 332–49.

- European Commission (2016). ‘Assessment of the Effectiveness of the Existing System of European Public Financing Institutions in Promoting Investment in Europe and Its Neighbourhood’, COM(2016) 46 Final. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission (2017). ‘Proposal for a Council Regulation on the Establishment of the European Monetary Fund’, COM/2017/0827 final – 2017/0333.

- European Commission (2022a). ‘Commission Proposes Stable and Predictable Support Package for Ukraine for 2023 of up to €18 Billion’, Press Release, 9 November, IP/22/6699.

- European Commission (2022b). ‘Questions and Answers: Unified Funding Approach to EU Borrowing’, 19 December, Questions and Answers 22/789. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission (2023). ‘EU Funding Operations Remain Strong in Second Half of 2022 According to New Report’, News Article, 22 February, Brussels: European Commission.

- European Court of Auditors (1982). ‘Special Report of the Court of Auditors on Loans and Borrowings’, Official Journal of the European Communities, 1982 Official Journal (C 319/1) 25.

- European Court of Auditors (1990). ‘Special Report No 3/90 on ECSC, Euratom and NCI Loans and Borrowings of the Communities Together with the Replies of the Commission’, 1990 Official Journal (C160).

- European Court of Auditors (2018). ‘Public Private Partnerships in the EU’, Special Report No 9/2018. Luxembourg: ECA.

- European Court of Auditors (2023a). ‘The Recovery and Resilience Facility’s Performance Monitoring Framework – Measuring Implementation Progress but Not Sufficient to Capture Performance’ Special Report 26/2023. Luxembourg: ECA.

- European Court of Auditors (2023b). ‘Design of the Commission’s Control System for the RRF’, Special Report 07/2023. Luxembourg: ECA.

- European Investment Bank (2021). ‘Tripartite Agreement between the European Commission, the European Court of Auditors and the European Investment Bank’. Luxembourg: EIB.

- European Parliament (1995). ‘Resolution on the Functioning of the Treaty on European Union with a View to the 1996 Intergovernmental Conference – Implementation and Development of the Union’, Official Journal C 151, 19/06/1995 P. 0056.

- European Parliament (2002). ‘Report on the Activities of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)’, Report 2002/2095(INI). Brussels: European Parliament.

- European Parliament (2013). ‘Klaus Regling Quizzed about Wider Lending Role for European Stability Mechanism’, Press Release, 24 September. Brussels: European Parliament.

- European Parliament (2014a). ‘Klaus Regling Fields MEPs’ Questions in Troika Inquiry’, Press Release, 15 January. Brussels: European Parliament.

- European Parliament (2014b). ‘Report on the Enquiry on the Role and operations of the Troika (ECB, Commission and IMF) with Regard to the Euro Area Programme Countries’, Report 2013/2277(INI). Brussels: European Parliament.

- European Parliament (2020). ‘COVID-19 and the Role of EIB in the EU Response: Public Hearing’, 26 May. Brussels: European Parliament.

- European Parliament (2023). ‘Debate with I. Tsanova from DG BUDG on NGEU and MFA + Borrowing. 31 January 2023’, Press Release, 8 February. Brussels: European Parliament.

- European Stability Mechanism (2021). ‘Annual Report 2021’. Luxembourg: ESM.

- Fasone, Cristina (2022). ‘Fighting Back? The Role of the European Parliament in the Adoption of Next Generation EU’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 28:3, 368–84.

- Follesdal, Andreas, and Simon Hix (2006). ‘Why There Is a Democratic Deficit in the EU: A Response to Majone and Moravcsik’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 44:3, 533–62.

- Fromage, Diane, and Menelaos Markakis (2022). ‘The European Parliament in the Economic and Monetary Union after COVID: Towards a Slow Empowerment?’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 28:3, 385–401.

- Genschel, Philipp, and Markus Jachtenfuchs, eds. (2014). Beyond the Regulatory Polity? The European Integration of Core State Powers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hachez, Nicolas, and Jan Wouters (2012). ‘A Responsible Lender? The European Investment Bank’s Environmental, Social, and Human Rights Accountability’, Common Market Law Review, 49:1, 47–95.

- Hall, Peter, and Rosemary Taylor (1996). ‘Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms’, Political Studies, 44:5, 936–57.

- Hancock, Alice (2022). ‘European Investment Bank Pledges to Cut Spending on Roads’, Financial Times, 17 July.

- Hix, Simon (2018). ‘When Optimism Fails: Liberal Intergovernmentalism and Citizen Representation’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:7, 1595–613.

- Hodson, Dermot, and David Howarth (2023). ‘From the Wieser Report to Team Europe: Explaining the "Battle of the Banks" in Development Finance’, Journal of European Public Policy, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2221301

- Höing, Oliver (2015). ‘Asymmetric Influence: National Parliaments in the European Stability Mechanism’, PhD submitted to the Univesität zu Köln, available at: https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/6485/1/Hoeing_Dissertation.pdf.

- Howarth, David, and Aneta Spendzharova (2019). ‘Accountability in Post-Crisis Eurozone Governance: The Tricky Case of the European Stability Mechanism’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57:4, 894–911.

- Irmer, Ulrich (1981). ‘Report Drawn Up on Behalf of the Committee on Budgetary Control’, European Parliament Working Documents, 27 April, L-L36/8L/A. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Jopson, Barney (2022). ‘Spain Rejects Criticism over Slow Spending of EU Recovery Funds’, Financial Times, 8 November.

- Laffan, Brigid (1997). The Finances of the European Union. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- Laffan, Brigid (1999). ‘Becoming a ‘Living Institution’: The Evolution of the European Court of Auditors’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 37:2, 251–68.

- Lastra, Rose, and Heba Shams (2001). ‘Public Accountability in the Financial Sector’, in Elis Ferran and Charles Goodhart (eds.), Regulating Financial Services and Markets in the 21st Century. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 165–88.

- Liboreiro, Jorge (2022). ‘Ukraine War: The EU Promised €9 Billion in Financial Aid to Kyiv. Where is It?’, My Europe, 8 November.

- Majone, Giandomenico (1994). ‘The Rise of the Regulatory State in Europe’, West European Politics, 17:3, 77–101.

- Majone, Giandomenico (2014). ‘From Regulatory State to a Democratic Default’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52:6, 1216–23.

- Moravcsik, Andrew (1993). ‘Preferences and Power in the European Community: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist Approach’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 31:4, 473–524.

- Moravcsik, Andrew (2002). ‘Reassessing Legitimacy in the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40:4, 603–24.

- Moravcsik, Andrew (2018). ‘Preferences, Power and Institutions in 21st-Century Europe’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56:7, 1648–74.

- Musgrave, Robert (1956). ‘A Multiple Theory of Budget Determination’, FinanzArchiv/Public Finance Analysis, 17:3, 333–43.

- Park, Susan (2021). ‘Policy Norms, the Development Finance Regime Complex, and Holding the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to Account’, Global Policy, 12:S4, 90–100.

- Pop, Valentina (2022). ‘Rising Borrowing Costs Put Strain on EU Budget’, Financial Times, 19 October.

- Poppelaars, Suzanne (2018). ‘The Involvement of National Parliaments in the Current ESM and the Possible Future EMF’, LUISS School of Government, SOG-WP44/2018.

- Przeworski, Adam, Susan Stokes, and Bernard Manin, eds. (1999). Democracy, Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Regling, Klaus (2019, January 29). ‘What Comes after the Euro Summit? The Role of the ESM in a Deepened Monetary Union’, Representation of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia to the EU, Brussels, Belgium. Speeches, 29 January. Luxembourg: ESM.

- Rittberger, Berthold (2014). ‘Integration without Representation? The European Parliament and the Reform of Economic Governance in the EU’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 52:6, 1174–83.

- Schelkle, Waltraud (2021). ‘Fiscal Integration in an Experimental Union: How Path-Breaking Was the EU’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:Suppl 1, 44–55.

- Schmidt, Vivien (2020). Europe’s Crisis of Legitimacy: Governing by Rules and Ruling by Numbers in the Eurozone. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Skiadas, Dimtrios (1999). ‘European Court of Auditors and European Investment Bank: An Uneasy Relationship’, European Public Law, 5:2, 215–25.

- Stuiveling, Saskia, and Ellen van Schoten (2012). ‘Brief van de Algemene Rekenkamer’. Raad voor Economische en Financiële Zaken, 27 February, 21 501-07. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Tweede, Kamer (2018a). ‘Brief van den Minister voor Financiën. Kamerstuk’, 21 507-07. Raad voor Economische en Financiële Zaken, 31 August, 21 501-07, Nr. 1541. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Tweede, Kamer (2018b). ‘Antwoord op vragen van het lid Van Raan over het bericht dat twee NGO’s een klachtenprocedure zijn gestart tegen het Oekraïense kippenbedrijf MHP, dat zaken doet met Nederlandse bedrijven die hiervoor exportkredietverzekeringen hebben afgesloten bij Atradius’, Vragen gesteld door de leden der Kamer, met de daarop door de regering gegeven antwoorden, 2757. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Tweede, Kamer (2020). ‘Antwoord op vragen van het lid Van Raan over Nederlandse investeringen in dierenleed’. Vragen gesteld door de leden der Kamer, met de daarop door de regering gegeven antwoorden, 2183. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Tweede, Kamer (2022a). ‘Diverse onderwerpen met betrekking tot de Europese Investeringsbank (EIB)’. Vragen gesteld door de leden der Kamer, met de daarop door de regering gegeven antwoorden, 1900. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Tweede, Kamer (2022b). ‘Kamerbrief over jaarverslag ESM en financiële rekeningen EFSF’, 2021’. Vragen gesteld door de leden der Kamer, met de daarop door de regering gegeven antwoorden, 1900. Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

- Vitsentzatos, Michail (2014). ‘Loans and Guarantees in the European Union Budget’, ERA Forum, 15:1, 131–44.

Appendix

Interviews

Interview 1: Dutch MP, member of the Tweede Kamer Budget Committee, 12 April 2023.

Interview 2: EU affairs official, Dutch Ministry of Finance, 12 April 2023.

Interview 3: Senior advisor, Dutch Ministry of Finance, 9 May 2023.

Interview 4: Former Dutch national representative, European Investment Bank and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 31 May 2023.

Interview 5: Former EIB official who worked in the EIB's Brussels office, 27 January 2022.

Interview 6: EU affairs official, Algemene Rekenkamer (Dutch Court of Auditors), 23 March 2023.

Interview 7: Official, European Court of Auditors, 28 March 2023.

Interview 8: Two officials, European Court of Auditors, 30 March 2023.

Interview 9: Official, Bundesrechnungsof (German Court of Auditors), 20 October 2023.

Interview 10: Former EIB Vice-President, 12 January 2024.

Interview 11: Klaus Regling, Former Managing Director of the ESM, 28 November and 1 December, 2023.

Table A1. Overview of pan-European borrowing instruments.

Table A2. Overview of governing bodies.