Abstract

Political parties address the public through multiple communication channels simultaneously, but this is not reflected in contemporary research. It is largely unclear how party competition plays out across different communication channels and whether issue salience strategies depend on the channel used. In order to answer this question, this article trains a state-of-the-art language model (BERT) on labelled manifestos and applies it for cross-domain topic classification of press releases, parliamentary speeches and tweets from parties and individual party members in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. The results show that certain channel characteristics influence parties’ issue salience. The extent to which a party addresses its issue preferences (ideal agenda) is moderated by the degree of centralised communication (party vs. individuals) and the presence or absence of a pre-given agenda, whereas a channel’s primary audience (direct vs. mediated channel) plays a much smaller role than expected. These findings illustrate the complexity of party competition in contemporary multi-channel and hybrid media environments.

What political parties talk about is a central question in political science. Which issues are discussed defines the locus of political conflict (e.g. Green-Pedersen and Walgrave Citation2014), influences voting decisions (e.g. Alvarez and Nagler Citation1995) and shapes public discourse as well as dynamics of party competition (e.g. Green-Pedersen Citation2007). A large body of research examines political parties’ issue salience strategies and the effects of such strategies on how (representative) democracies function. Existing studies cover several different party communication channels, such as manifestos (e.g. Green-Pedersen Citation2007; Guinaudeau and Persico Citation2014), press releases (e.g. Gessler and Hunger Citation2022; Hopmann et al. Citation2012), parliamentary speeches (e.g. Debus and Tosun Citation2021; Quinn et al. Citation2010) or social media (e.g. Barberá et al. Citation2019; Gilardi, Gessler, et al. Citation2022).

These studies offer multiple valuable insights, but one crucial aspect has largely not yet been reflected. Political communication is a rapidly changing field with new (digital) channels developing constantly. Thus, dynamics of political communication and party competition are no longer restricted to particular channels. Political actors use the ever-growing number of channels to communicate policies and connect with different audiences and social groups. Hence, party competition takes place within and (potentially) across multiple venues simultaneously, with potential implications for public discourse, voting behaviour and democratic representation. Most existing research, however, exclusively studies one particular communication channel in isolation. Comparative research is rare and limited to specific (short) time periods, such as during election campaigns (Elmelund-Præstekær Citation2011; Green and Hobolt Citation2008; Norris et al. Citation1999; Tresch et al. Citation2018). It remains largely unclear to what extent and – most importantly – why parties adapt their behaviour according to different communication channels. Do parties’ issue salience strategies change depending on the channel used? If so, why?

Existing comparative research does offer some insights, but significant gaps remain. While Norris et al. (Citation1999), Elmelund-Præstekær (Citation2011) and Tresch et al. (Citation2018) find differences in issue salience across multiple channels, this is not the case for Green and Hobolt (Citation2008). Crucially, we still lack a coherent theoretical framework to detect the precise factors that influence parties’ issue salience strategies in different channels (Elmelund-Præstekær Citation2011). Grasping how parties use different channels is key to understanding the dynamics of party competition in the rapidly changing political communication environment of contemporary democracies.

This article contributes to the literature by studying the extent to which parties’ issue salience changes depending on the communication channel and why. I argue that issue salience is influenced by the characteristics of communication channels. More specifically, depending on the channel, parties focus on their issue preferences (ideal agenda) to different degrees. Three factors should be important.

First, parties reach different audiences through various communication channels. While mediated channels are primarily aimed at journalists (e.g. press releases), others allow parties to connect directly with the public (e.g. social media). Second, party communication can be centralised in the hands of the party leadership and central office (e.g. official party press releases or social media posts from party accounts) or decentralised (e.g. social media posts from individual party members). Third, communication in some channels is structured by some sort of pre-given structure or agenda (e.g. legislative agenda). Therefore, I differentiate pre-structured (e.g. parliamentary speeches) and non-pre-structured communication channels (e.g. tweets, press releases). I expect these three factors to moderate the influence of party preferences on issue salience in the respective communication channels.

Methodologically, I use an advanced text-as-data technique to analyse a broad range of texts produced by political parties. I train a transformer-based model (BERT) on labelled manifestos and apply it cross-domain to classify press releases, parliamentary speeches and tweets from parties and individual party members into issue categories. The study covers the cases of Austria, Germany and Switzerland between January 2019 and September 2021. Overall, the data set consists of more than 41,000 parliamentary speeches and 34,000 press releases, nearly 72,000 tweets from party accounts and more than 420,000 tweets from individual party members.

The empirical results show that political parties’ issue salience is influenced by the communication channel. I observe different issue agendas in each examined channel and find evidence that salience is moderated by specific channel characteristics. Party preferences have a greater influence on issue salience in centralised communication channels, but play a smaller role in pre-structured channels. Both observations follow the theoretical expectations. This is, however, not the case for mediated vs. direct channels; here, the results deliver no statistically significant difference.

These findings have several implications and underscore the importance of studying different sources of party communication. First of all, this article shows that a single, unified political agenda does not exist. Political parties send different policy signals in different venues. This is driven by the nature and characteristics of communication channels. Furthermore, dynamics and patterns of party competition – such as the responsiveness to public opinion or the level of issue engagement between parties – may therefore also shift depending on the channel. This can result in different public perceptions of the parties and the competition between the parties. Interestingly, however, parties do not appear to adapt their communication significantly when the channel’s audience consists primarily of journalists. At first glance, this is a surprising and counterintuitive finding, but it actually fits hybrid media system theory. In hybrid media environments, journalists increasingly make use of alternative sources of information (e.g. social media) to learn about political processes (Chadwick Citation2017). Political actors, in turn, adapt their behaviour to this development and also address journalists in direct channels, such as on X, formerly Twitter. This modern combination of multi-channel and hybrid media environment, which simultaneously leads to a segregation and blurring of audiences, helps to explain why parties do not change their issue salience strategies considerably between mediated and direct channels.

In the following, I will lay out the theoretical framework that captures the factors influencing party issue salience in different communication channels. Then, I will describe the data set and text-as-data approach used to study issue communication in diverse types of text. Finally, I will present the results and conclude with reflections on the broader implications of the findings.

Theoretical framework

Political actors are subject to multiple sources of influence when it comes to communication strategies. For studying parties’ issue salience across different communication channels, two factors identified by Green-Pedersen and Walgrave (Citation2014) are especially relevant: preferences and institutions.

First, political actors have certain preferences. In the case of parties – the unit of analysis in this article – issue preferences mainly stem from ideological and strategic sources. On the one hand, parties have certain issues that are closely connected to their ideology. The issue of the environment is, for example, at the core of Green party ideology, while Social Democratic parties have a strong ideological interest in labour and welfare state issues. Thus, parties have ideologically driven issue preferences. On the other hand, party preferences also result from strategic considerations related to issue ownership. Issue ownership theory suggests that parties ‘own’ certain issues, either because they are associated with the issue by the public or are regarded as the most competent on it (Walgrave et al. Citation2012). If the public sees a particular party as ‘better able’ to handle a specific issue than other parties, that party has ownership of that issue (Petrocik Citation1996). Thus, issue ownership scholars argue that ‘owning’ an issue brings advantages in party competition.

Parties therefore try to raise the salience of issues ideologically or strategically important to them, while avoiding a direct issue-conflict with other parties (Budge Citation2015; Budge and Farlie Citation1983). This leads to a competition over the political agenda (Carmines and Stimson Citation1993; Green-Pedersen Citation2007). Based on such ideological and strategic preferences, parties develop a so-called ideal agenda and try to push it in the political debate. The ideal agenda reflects the importance of individual issues to a party and is best reflected in party manifestos (Budge et al. Citation1987; Norris et al. Citation1999).

Second, political actors operate within various institutions, whose rules shape the amount of attention the actors can pay to an issue (Green-Pedersen and Walgrave Citation2014). Hence, institutions can be interpreted as structures, which influence party behaviour in issue communication. Institutions take multiple forms, and the definition of what constitutes an institution is strongly contested. One of the most influential conceptualisations argues that institutions consist of formal as well as informal rules, ranging from constitutional orders to simple conventions (Hall and Taylor Citation1996). Following from this definition, many different venues where political processes take place can be described as institutions. This also applies to political parties’ communication channels. These are venues wherein or instruments with which political parties and their members themselves communicate and discuss policies. I understand all channels that shape the public profile of parties, ranging from press releases published by central offices to parliamentary speeches and social media posts by individual party members, as party communication channels.

While research has long focused on manifestos and press releases, recent work also points out and acknowledges the importance of other communication sources. For example, interest in social media is growing, specifically how both parties and individual politicians use it, how it transforms the relationship between parties and their members (e.g. MPs) as well as how it affects agenda setting dynamics (e.g. Gilardi, Gessler, et al. Citation2022; Peeters et al. Citation2019; Sältzer Citation2022; Silva and Proksch Citation2022). Furthermore, an increasing number of studies also finds that parliamentary speeches are another crucial avenue for parties and their MPs to send policy signals (e.g. Debus and Tosun Citation2021; Ivanusch Citation2023; Proksch and Slapin Citation2015). These studies show that several communication channels have become important tools for parties when it comes to issue communication. However, the different channels also possess distinguishing characteristics, rules and conventions that potentially influence political parties’ communication profiles (e.g. Dalmus et al. Citation2017; Elmelund-Præstekær Citation2011; Tresch et al. Citation2018). Thus, different communication channels can be viewed as institutions that create a structure governing the issue communication of parties and their members. I therefore expect party issue salience to be influenced by the communication channel and its characteristics.

As mentioned above, parties usually aim to communicate their issue preferences, i.e. ideal agenda. However, communication channels and their characteristics provide structures that should moderate the amount political parties focus on issue preferences. What are these channel characteristics and how do the various channels influence party behaviour?

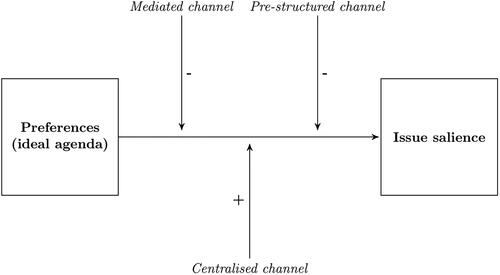

Two relevant characteristics can be identified in the literature, namely the type of audience and the degree of control a party can exert over a given channel (Dalmus et al. Citation2017; Elmelund-Præstekær Citation2011). These theoretical considerations offer a strong foundation. Some adaptations are, however, needed. The framework set forth in the following differentiates three characteristics and postulates corresponding hypotheses (H1–H3). illustrates these hypotheses graphically.

Figure 1. Factors expected to influence party issue salience in different communication channels (H1–H3).

The first hypothesis relates to the differing audiences addressed by each communication channel. Certain channels allow parties or individual politicians to address the public and their followers directly, especially social media (Peeters et al. Citation2019; Popa et al. Citation2020). In such direct channels, parties can act (relatively) freely and I therefore expect them to communicate strongly according to their issue preferences. In contrast, press releases are a mediated communication channel. They are primarily aimed at journalists and rarely reach the broader public directly (Dalmus et al. Citation2017). Therefore, parties have to consider the needs and interests of journalists in press releases. This applies not only to formal criteria but also to the selection of issues addressed within a press release. Journalists are, for example, strongly interested in issues that are already salient in the media and among other important actors. In contrast, issues ‘owned’ by a party do not have a high news value (Dalmus et al. Citation2017; Meyer et al. Citation2020). Hence, I hypothesise that parties do not focus solely on their issue preferences but on a broader set of issues in mediated communication channels in order to meet the interests and needs of journalists.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): In mediated channels, issue preferences (ideal agenda) have a smaller influence on issue salience than in direct channels.

The second hypothesis is based upon communication channels varying in the degree of centralisation. In centralised channels, messages are sent by the party leadership or by the central office or at least have to pass through one or both of them. Here, the central and national organisation unit – the party in central office (Katz and Mair Citation1995) – has tight control over issue communication. In other channels this is not the case as individual party members communicate themselves. Examples of such decentralised communication channels include social media accounts of individual politicians. The degree of centralisation thereby has implications for a party’s issue communication on the whole as well as for its public profile, leading to an increasing research interest, particularly since the advent of social media. Therefore, the actual influence of centralised and decentralised communication channels on the profile of a party and its issue agenda is an important topic.

According to Silva and Proksch (Citation2022), communication by individual party members (i.e. decentralised communication) may serve two purposes. On the one hand, decentralised communication can amplify central party messages, since individual politicians (particularly in systems with strong parties) have strong incentives to follow the party line (e.g. Kam Citation2009; Sieberer Citation2006) and parties simultaneously try to enforce unity (e.g. Proksch and Slapin Citation2015). On the other hand, decentralised communication can serve as a substitute for central party communication channels and represent an avenue to send a variety of policy signals (Silva and Proksch Citation2022).

I argue that three factors are important here. First, strategic communication according to issue preferences requires coordination. Centralised communication in the hands of the central party office allows for better coordination and communication closer to the party line and issue preferences. Second, parties are in firm control in centralised channels, while decentralisation allows individual members to potentially circumvent partisan constrains and push their own preferences (Enli and Skogerbø Citation2013; Silva and Proksch Citation2022). Third, decentralised communication may also provide an incentive for parties to expand their appeal by focusing on a broader set of issues. Thus, decentralised channels may also be a strategic tool to focus less on issue preferences but on a variety of issues. Based on these considerations, I expect the communication of political parties to be more in line with issue preferences when communication is centralised than when it is decentralised.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Higher degrees of centralised communication within a channel lead to a stronger influence of issue preferences (ideal agenda) on issue salience.

The third hypothesis deals with a channel’s degree of pre-structuredness and the influence thereof on issue communication. In highly pre-structured channels, the topical focus is pre-given to a certain extent, and parties only have limited control over issue selection. Hence, issue communication is pre-structured. Examples of such an environment are parliamentary debates. Parliamentary debates are one of the most important arenas of political communication and a key tool for parties to send policy signals in party competition (Proksch and Slapin Citation2015). This also applies to the issues discussed in parliamentary speeches, as recent research finds that parties and their MPs use speeches to advance their issue preferences (Debus and Tosun Citation2021; Ivanusch Citation2023). However, parliamentary speech-making is also substantially influenced by the legislative agenda. Most of the time, bills or specific topics are debated in parliament (Proksch and Slapin Citation2015). Certain issues are given from the start; these in turn structure issue communication during parliamentary debates. This is the process that is encompassed by the concept of pre-structuredness. Such an environment makes it more difficult for parties and their members to communicate according to their ideal agenda. Moreover, parties may have different opportunity structures to influence the pre-structuredness of a channel. For example, partisan control over the legislative agenda often provides government parties with more influence over the issues discussed in parliamentary debates than opposition parties (Cox and McCubbins Citation2005; Döring Citation1995).

These dynamics show that important party communication channels, such as parliamentary speeches, are subject to very specific institutional contexts. In these channels, issue communication is significantly pre-structured, restricting parties when it comes to discussing their issue preferences. Thus, although recent research shows that parties find at least some room to focus on their issue preferences in pre-structured channels (e.g. parliamentary speeches), I still expect issue preferences to be much less reflected here than in other communication channels.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Higher degrees of pre-structured communication within a channel lead to a smaller influence of issue preferences (ideal agenda) on issue salience.

Case selection

For the analysis, I draw on a data set comprising a variety of texts produced by political parties in Austria, Germany and Switzerland between January 2019 and September 2021. I rely on this case selection for three main reasons.

First, the selected countries represent typical Western European multi-party systems while still allowing to control for potential variations stemming from different electoral systems and political cultures (e.g. government-opposition dynamics). While Germany uses a mixed electoral system, Austria and Switzerland use proportional systems. However, electoral districts and party lists play different roles in the electoral systems of Austria and Switzerland. Furthermore, Switzerland differs significantly from the other two countries when it comes to government formation and direct democracy. Switzerland has a strong tradition of consociationalism and therefore usually relies on a special formula (Zauberformel) to form a government. Additionally, Switzerland makes ample use of referenda, which is not the case in Austria or Germany.

Second, the broad time period covered (1 January 2019–26 September 2021) allows for party issue salience to be studied at multiple points in time and in different phases of political communication. The selected period covers one election campaign per country (Austria: 2019; Germany: 2021; Switzerland: 2019) as well as ‘routine times of politics’. Furthermore, it includes several months before and during the Covid-19 pandemic to account and control for potential effects of this crisis on party behaviour.

Third, all three countries studied are German speaking.Footnote1 As I employ quantitative computer-based text analysis, a mono-lingual analysis should ensure higher reliability and comparability. While comparing different types of texts is a significant challenge in itself, a multi-lingual analysis would create even more and yield potentially incommensurable results (Chan et al. Citation2020; Maier et al. Citation2022).

Data

The main text corpus used in this article consists of four types of party communication channels: press releases, parliamentary speeches, tweets from party accounts and tweets from individual party members. As an additional data source for the analysis, I use labelled manifestos from the Manifesto Project (Lehmann, Burst, Lewandowski, et al. Citation2022). This channel selection is well suited for the purpose of this study because of two main reasons.

First, all the channels selected are important avenues for parties and their members to communicate with the public on a regular basis. Press releases are important and flexible tools for parties to inform journalists about specific issues and respond to daily developments (e.g. Dalmus et al. Citation2017; Klüver and Sagarzazu Citation2016). Furthermore, the content of press releases can potentially reach a large audience, if picked up by journalists (Hopmann et al. Citation2012; Meyer et al. Citation2020). Parliamentary speeches as well are an avenue for parties and their MPs to send policy signals (Proksch and Slapin Citation2015). Recent research shows that parties advance their issue preferences in parliamentary debates, making them an important tool in issue competition (e.g. Debus and Tosun Citation2021; Ivanusch Citation2023). How parliamentary speeches compare to other tools such as press releases is largely unclear, however. Tweets (and social media posts in general) are also frequently used by political actors to communicate with the public and to engage with or criticise political opponents (e.g. Gilardi, Gessler, et al. Citation2022; Russell Citation2018). For this case study, I choose Twitter, now X, for the social media channel because it is well suited to measure the content of broad national political debates. Previous research shows that Facebook, for example, is mainly used by political actors for (local) campaign-related purposes, whereas Twitter is the primary platform where contemporary political events are discussed on a national-level (Stier et al. Citation2018).

Second, the chosen channels differ in a number of dimensions. Crucially, at least one channel is different to all the others for each of the three channel characteristics introduced above. These differences are displayed in . The channels are assigned values of 0 or 1 for each of the three channel characteristics. While press releases are primarily targeted to journalists (i.e. mediated channel), the other channels are aimed more directly at the general public. Although Twitter has a more ‘elitist’ audience compared to Facebook, its architecture (i.e. hashtags, retweets) facilitates the diffusion of political information across the platform (Stier et al. Citation2018; Wu et al. Citation2011). Therefore, Twitter allows political actors to communicate political information directly to a broad audience without having to rely on journalists as gatekeepers. In terms of centralisation, tweets from party accounts are fully centralised, but the platform also facilitates decentralised party communication via the accounts of individual party members. Press releases and parliamentary speeches are a special case in terms of the centralisation characteristic. While individual members (regularly) draft press releases and give the speeches in parliament, the party leadership or party office retains a certain amount of control over the content.Footnote2 In terms of pre-structuredness, parliamentary speeches stand out due to the legislative agenda structuring the context and content of parliamentary debates.

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics per party communication channel.

The corpus covers the time period from 1 January 2019 to 26 September 2021 and was collected in the context of a bigger research project. The press releases contained in the corpus were published by the political parties and their parliamentary party groups (PPGs). For Austria and Germany, webscraping was used to download the press releases from a webservice of the Austrian Press Agency (https://www.ots.at/) and from the German party and PPG websites. In the case of Switzerland, the data was provided by the DigDemLab at the University of Zurich (Gilardi, Baumgartner, et al. Citation2022). The parliamentary speech data consists of an updated version of the ParlSpeech V2 data set (Rauh and Schwalbach Citation2020) for Austria and Germany and texts downloaded from the webservices of the Swiss parliament through the R package swissparl (Zumbach Citation2020). The tweets from party accounts (central office, PPG) and individual party members (party leaders, general secretary, all MPs) were collected through the Twitter Researcher API.Footnote3 provides an overview of the complete corpus used for this study. Overall, the corpus consists of more than 571,000 individual documents.Footnote4

Table 2. Number of documents per text type.

Methods

Cross-domain topic classification

Measuring issue salience in such a voluminous variety of texts is a significant challenge. In this article, I use an advanced text-as-data technique to study multiple types of text in a coherent and efficient way, namely cross-domain topic classification. Cross-domain learning is a way to reduce the necessary amount of training data and resources required for classic supervised approaches. Supervised models require labelled training data to learn about the specific task at hand, and labelling is resource intensive. With several different text types, as in this study, a very large amount of labelled training data would be needed for each individual text type. Cross-domain learning can mitigate this problem. The basic idea behind cross-domain learning is that models are only trained on a single type of text, but the trained model can also be applied to other types of text (e.g. Osnabrügge et al. Citation2021). This way, researchers only need to develop one training data set or can even use existing labelled data for training the model. Therefore, a huge potential for the application of cross-domain learning exists in political science and the social sciences in general.

For the cross-domain topic classification, I rely on the state-of-the-art transformer-based model BERT (Devlin et al. Citation2019). BERT is elaborately pre-trained on vast amounts of unlabelled text and provides a very good general syntactic and semantic representation of words. To use BERT for a specific application, only some minor training (‘finetuning’) is necessary. For this training procedure, I adapt the approach developed by Burst et al. (Citation2023a, Citation2023b) and train the BERT model on labelled manifestos provided through the corpus of the Manifesto Project (Lehmann, Burst, Lewandowski, et al. Citation2022). The Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR) uses human coding to analyse party manifestos from all over the world according to a set coding scheme. The coders thereby assign each individual (quasi-)sentence from the manifestos to one specific category. Overall, the Manifesto Project coding scheme consists of 76 main codes plus one ‘NA’ category (code ‘000’). For this article, I use the labelled manifestos as training data and assign all categories from the Manifesto Project to 20 overarching issues.Footnote5 The final training data set used here consists of more than 728,000 annotated (quasi-)sentences in total.

The annotated manifestos constitute a well-suited training data set for the BERT model.Footnote6 During training, the BERT model uses the annotated training data to learn about the specific task. In this case, BERT learns about the relationship between specific text features and issue categories via machine-learning. I then apply the trained model to the unlabelled texts of interest (press releases, parliamentary speeches, tweets from parties, tweets from individual party members). I use the model to classify each document into one of the issue categories specified in the codebook.Footnote7

Compared to a manually coded gold standard,Footnote8 the BERT model achieves an accuracy of 58% for press releases, 59% for parliamentary speeches and 50% for tweets.Footnote9 These are comparatively good results for cross-domain topic classification of multiple categories (20 categories), especially applied to such a diverse set of texts as in this article.Footnote10

Measuring the influence of channel characteristics on issue salience

The main goal of the analysis is to identify the effect of each individual channel characteristic on political parties’ issue salience. In order to achieve this, I use regression analysis on different samples and combinations of communication channels.

Dependent variable

Issue salience functions as the dependent variable in the analysis and is based on the results of the text analysis described above. It marks the percentage of attention a party devotes to a specific issue within a communication channel (e.g. press releases) over one quarter of a year. I choose to calculate issue salience by quarter as it allows a more reliable estimation than by month. Issue salience by month could be heavily influenced by external events and some channels do not produce consistent monthly communication.Footnote11 Thus, I use issue salience by quarter as the dependent variable in the regression analysis.

Independent variables

The first independent variable is manifesto salience. I use it to measure the influence of party preferences on issue salience within a communication channel (e.g. press releases). Manifesto salience refers to the percentage of attention a party devotes to a specific issue in its manifesto based on data from the Manifesto Project (Lehmann, Burst, Matthieß, et al. Citation2022). Manifestos are negotiated at length inside parties and are thus viewed as a ‘uniquely representative and authoritative characterisation of party policy at a given point in time’ (Budge et al. Citation1987, p. 18). Consequently, manifestos represent the ideal agenda of political parties and are therefore well-suited indicators to capture party issue preferences (Norris et al. Citation1999). As postulated in the hypotheses (H1–H3), the influence of manifesto salience on issue salience within a communication channel is expected to vary depending on the channel’s characteristics. To account for the potential variation in mediated, centralised and pre-structured channels, I use dummy variables as further independent variables (see ).

However, simply comparing multiple channels in a single regression model is not enough to identify the effect of each individual channel characteristic. Rather, it is necessary to isolate as much as possible the potential effect of each channel characteristic. In order to achieve this for the three identified channel characteristics, I use different samples. To investigate the effect of a specific characteristic, I compare two channels that are similar with regard to several characteristics except the specific one under investigation. Based on the resulting samples, I run different regression models for each channel characteristic.

Model specification

In order to measure the effect of a primarily journalistic audience (mediated channels) on issue salience, I compare press releases with tweets from party accounts. Neither channel is directly influenced by any pre-given structure (e.g. legislative agenda), and in both cases the party office has a considerable degree of control.Footnote12 Press releases are primarily drafted for a journalistic audience, however, and thus deemed a mediated channel; while tweets allow direct communication with the public.

For isolating the effect of centralised communication, I compare tweets from party accounts with tweets from individual party members. Here, the only difference between the two channels is the authorship of posts. While communication through party accounts is firmly in the hands of the central party office or PPG leadership (i.e. centralised), this is much less the case for communication via accounts of individual party members (i.e. decentralised).

To measure the effect of pre-structuredness within a channel, I use parliamentary speeches and press releases. Communication in both these cases is to a certain extent decentralised, but party leadership retains some sort of control (see discussion in endnote 2). Parliamentary speeches are, however, influenced by the bills and topics on the legislative agenda. This pre-given structure does not exist in press releases.

Based on these different samples, I apply individual regression models to identify the effect of a specific channel characteristic. The first model investigates the effect of mediated channels, the second of centralised channels and the third of pre-structured channels. As model specification, I use OLS regression with fixed effects for country, party, issue and quarter to account for potential unobserved differences between these groups. I also control for the time passed since the last election (i.e. quarters since last election) as this may impact the influence of manifestos on party communication. Furthermore, the observations are not independent from each other as the dependent variable issue salience is measured in percent per party and quarter. Thus, the values for issue salience are dependent on each other. To account for this data structure, I use panel-corrected standard errors (Beck and Katz Citation1996, Citation1995) in a similar way as Wagner and Meyer (Citation2014).

Results

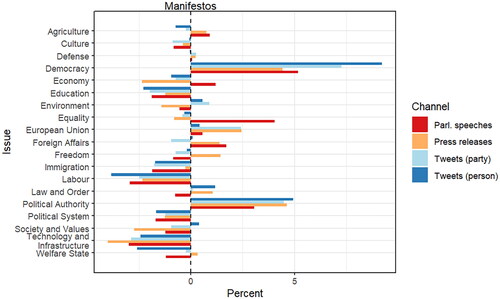

In a first step, it is worth taking a look at the overall distribution of issue salience within each communication channel. displays the extent to which issue salience in press releases, parliamentary speeches and tweets (party accounts and individual party members) differs from manifestos (ideal agenda) across all three countries and parties. It shows the difference between manifestos and the other channels per issue.Footnote13 What becomes clear is that issue agendas vary considerably across channels. This is especially pronounced for the issues of ‘democracy’ and ‘political authority’. While they play comparatively small roles in manifestos, this is not the case in the other channels. Political parties use social media (tweets) in particular to discuss democracy in general and to engage with or attack political opponents, as indicated by the issue of ‘political authority’ (e.g. references to party or personal competence). Similar patterns apply to press releases and parliamentary speeches, but to a more limited extent. Hence, discussions of political processes and competition between political actors are much more prevalent in tweets, press releases and parliamentary speeches than in manifestos. This is not surprising as these channels allow political actors to discuss and comment on different stages of the political process on a regular basis. The same cannot be said for manifestos, which are generally negotiated at length inside parties and only published ahead of elections.

Conversely, issues that are comparatively important in manifestos (e.g. ‘labour’, ‘welfare state’) receive significantly less attention in the other channels. Press releases, parliamentary speeches and tweets from party accounts or individual party members, however, also show clear differences between them. While ‘European Union’ receives comparatively greater attention in press releases and tweets from party accounts, parliamentary speeches show a relatively strong focus on ‘equality’ and ‘foreign affairs’. Similarly, ‘agriculture’ is comparatively salient in parliamentary speeches and press releases, but not in tweets. Hence, we can clearly observe different issue agendas across party communication channels, lending further support to past findings (Elmelund-Præstekær Citation2011; Norris et al. Citation1999; Tresch et al. Citation2018).

In the next step, the analysis focuses on how different communication channel characteristics affect issue salience. Through the different samples introduced earlier, I compare channels that are similar on a number of dimensions except the specific characteristic under investigation in order to isolate the effect of a particular channel characteristic. According to hypotheses H1–H3, the influence of party preferences (ideal agenda) on issue salience within a communication channel should be moderated by the specific channel characteristics. As discussed earlier, the issue preferences of parties (ideal agenda) are represented by the variable manifesto salience in the models.

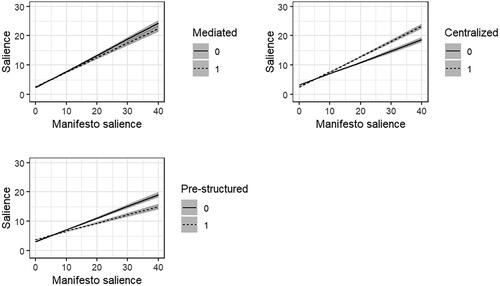

displays regression results that measure the moderating effect of channel characteristics on the influence of manifesto salience.Footnote14 The first model compares tweets from party accounts (direct) and press releases (mediated), but it does not find any statistically significant differences between them, as indicated by the interaction term. Therefore, H1 cannot be supported based on this finding. This contradicts a common argument in the literature. Existing research argues that mediated channels, such as press releases, are tailored to the needs and interests of journalists, who are usually interested in issues that are already salient in the media and among other important actors, but not so much in the communication of issue preferences (i.e. ‘owned’ issues). This is the case because the latter offer nothing ‘new’ and therefore do not have a high news value (Dalmus et al. Citation2017; Meyer et al. Citation2020).

Table 3. Influence of communication channel characteristics on party issue salience.

Although surprising at first sight, the lack of difference between direct and mediated channel fits well with hybrid media system theory. In hybrid media environments, actors simultaneously use ‘older’ and ‘newer’ logics in producing, distributing and consuming news and political information (Chadwick Citation2017). Journalists nowadays rely not only on traditional sources of information (e.g. press releases), but leverage alternative sources (e.g. social media) as well. Political actors, in turn, adapt to this new logic and now also address journalists through direct channels (e.g. Twitter aka X). Furthermore, the time and personnel required to draft social media posts is comparatively small. Parties can therefore discuss a broader set of issues and strict prioritisation according to the ideal agenda may not be highly relevant on many social media platforms. Therefore, hybrid media environments and the low costs of producing social media content can explain the lack of difference between direct and mediated channels observed in this study.

The second regression model evaluates the influence of centralised communication on parties’ issue salience. Although decentralised communication arguably can serve as an amplifier of central party messages, H2 still expects that party preferences have a greater influence on issue salience in centralised channels than in decentralised ones. This should be the case as centralisation allows better coordination and firm control of content by the party office. Furthermore, decentralised communication may also provide an incentive for parties and their members to expand their appeal by focusing on a broader or different set of issues. Therefore, communication along the ideal agenda should be more prevalent in centralised channels than in decentralised ones. In the model, I compare (centralised) tweets from party accounts with (decentralised) tweets from individual party members. The results indeed show a stronger effect of manifesto salience in the centralised channel (see interaction term). The effect is statistically significant and H2 can therefore be supported.

The third model investigates whether pre-structured channels negatively affect the influence of party preferences on issue salience. The model compares parliamentary speeches (pre-structured) with press releases (not pre-structured). The interaction term indicates that the ideal agenda (i.e. manifesto salience) has a significantly smaller effect on issue salience in pre-structured channels. This finding confirms the expectations postulated in H3. Pre-given agendas (e.g. legislative agenda in parliamentary speeches) force parties to focus on a specific set of issues and limit their room for manoeuvre. This negatively influences the ability of political parties to communicate according to their issue preferences.

shows the predicted influence of communication channel characteristics on party issue salience. The individual plots illustrate the statistically significant difference in issue salience resulting from centralised and pre-structured channels, but not from mediated ones.

Furthermore, I conduct several robustness checks and additional analyses controlling for potential effects caused by party-level factors (e.g. government participation, mainstream/niche party status) and contextual factors (e.g. election campaigns, Covid-19 pandemic). First, Online Appendix A.9 shows that the main results are comparatively stable for all three countries under investigation, although some differences do exist. Similar to the main model, I find support for H2 and H3 in the case of Switzerland, while for Austria all three hypotheses are supported, and in the case of Germany only H2 finds empirical support.

Second, Online Appendix A.10 focuses on potential differences between government and opposition parties. In general, this analysis finds similar effects for the main interaction effects of interest for both types of parties. However, issue preferences (i.e. manifesto salience) are more strongly reflected in the communication of opposition parties in general, as they are (probably) less obliged to respond to a broad set of issues than parties in government. At the same time, however, opposition parties are more strongly constrained by mediated and pre-structured channels (see negative effects in interaction terms). Particularly the latter finding is not surprising, as government parties have more control over the legislative agenda than opposition parties. Thus, I do find some differences between parties caused by their respective (legislative) agenda setting power.

Third, Online Appendix A.11 gives a comparison of mainstream and niche parties. Here, I find similar effects as those for the comparison between government and opposition parties. In general, niche parties stick more closely to their issue preferences than mainstream parties, but are at the same time more strongly affected by pre-structured channels, such as the legislative agenda in parliamentary speeches.

Fourth, Online Appendices A.12 and A.13 show how I control for potential differences between ‘routine times’ of politics and campaign periods as well as for potential effects caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. In both cases, I find no systematic effects on the analysis caused by campaigns or the Covid-19 pandemic. The only exception is a statistically significant effect for the interaction term between the variables manifesto salience and mediated before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and during periods with comparatively low problem pressure, while this is not the case during periods with comparatively high problem pressure caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, the null finding for the first hypothesis might be due not only to changing political communication and media environments (e.g. hybrid media environments) but also the influence of the Covid-19 pandemic on party competition.

Finally, I control for potential issue-specific effects following a jack-knife logic (see Online Appendix A.14). Here, I calculate the main regression analysis reported in the paper but exclude each issue category from the analysis once. Again, the results remain largely stable across the different models. Thus, the results do not appear to be related to issue-specific effects or deteriorated results for specific issues caused by the text analysis.

Discussion and conclusion

Political parties use an ever-growing amount of communication channels simultaneously. These channels differ on a number of dimensions. Each channel gives access to different audiences, and each one has its own rules and conventions. These characteristics potentially affect the content of political communication and the dynamics of party competition in many ways. Most existing research has, however, merely analysed single communication channels in isolation. Dynamics of party competition within and across multiple channels have largely been a blind spot in the literature. In this article, I have taken a step towards closing this research gap by comparing press releases, parliamentary speeches, tweets from party accounts and tweets from individual party members. The article thereby contributes to the literature in three ways.

First, the article develops and tests a theoretical framework that captures the factors influencing party issue salience in different channels. I expect the main audience (direct vs. mediated channels), the degree of centralisation (party vs. individual members) and the degree of pre-structuredness (presence vs. absence of pre-given agenda) to moderate the influence of party issue preferences (ideal agenda) on issue salience within a channel. The results confirm a stronger focus on party preferences in centralised channels than in decentralised ones (H2). Thus, decentralised communication (e.g. tweets from individual party members) is not simply an amplification of central party messages. In fact, decentralised communication with the related coordination challenges as well as the lack of control by the party leadership and central office make adherence to the ideal agenda more difficult. Furthermore, decentralised communication may even incentivise parties and their members to deviate from the ideal agenda and send divergent policy signals. The analysis also shows that the pre-structuredness of a channel has negative effects on parties’ ability to communicate according to issue preferences, confirming the third hypothesis. Thus, although parties are indeed able to send policy signals in pre-structured channels, such as parliamentary speeches, this is more limited compared to other channels, such as press releases. However, the constraining factor is thereby much stronger for opposition and niche parties than for government and mainstream parties.

Contrary to these findings, I observe no statistically significant differences between mediated and direct channels (H1). This result points to the existence and relevance of so-called hybrid media environments. In hybrid media environments, journalists increasingly use alternative sources of information (e.g. social media), and political actors adapt to this new logic, leading to a blurring of direct and mediated channels. Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic may have influenced party communication in this regard, as an additional robustness check has shown.

Second, the results add depth to findings from previous studies and set the stage for potential future research. The article shows that multiple political agendas exist in parallel and can even originate from the same actor. On the one hand, this supports and strengthens previous findings and, on the other hand, highlights the need for research to focus more strongly on the heterogeneity of political agendas as well as their effects within political systems. Modern multi-channel political communication and agenda setting potentially have numerous heterogeneous effects on different publics, political actors and institutions. Therefore, it is crucial to dive even deeper into these processes and their effects on various democratic processes. Furthermore, the results illustrate that scholars should carefully consider the choice of party communication channel in their research. It can be problematic to simply select a channel and assume that it represents party policy without considering the implications of that choice. Particularly in contemporary fragmented and high-choice political communication environments, it may not be useful for parties to limit themselves to a single ideal agenda. Different social groups have different preferences and this may incentivise parties to adjust their issue agendas to broaden their (electoral) appeal. Thus, parties may tailor their messages and issue agendas to fit different communication channels and the various social groups that can be reached through them. Therefore, a theory-driven selection of communication channels is imperative for research on party competition and political communication.

Third, the article uses an advanced text-as-data approach to identify issues in a diverse set of documents. The application of the transformer-based model BERT for cross-domain topic classification allows multiple different types of text to be studied in a coherent and efficient way. Cross-domain learning is a comparatively resource-efficient and promising technique with various potential use cases in political science, such as the tracking of issue attention at different stages of the political process (i.e. in manifestos, coalition agreements).

Overall, this article has shown that parties’ issue salience is influenced by communication channels and their characteristics. Understanding this behaviour is crucial to keep up with dynamics of party competition in an ever-fragmenting information and political communication environment. Although this article took a first step into this direction, more work is necessary. This article has been limited to press releases, parliamentary speeches and tweets. Testing the proposed theoretical framework on other channels (e.g. Facebook, party newsletters, party websites) would add valuable information and rigour. This may be particularly relevant for various types of social media. In this study, I have relied on tweets as a social media channel. However, each social media platform has different types of audiences and follows its own logics, potentially influencing the behaviour of political actors. Although X (Twitter at the time for data collection) is widely used by both political actors and others, its audience is comparatively ‘elitist’ in German-speaking countries. Facebook or Instagram, in contrast, reach a broader audience. Thus, investigating differences between social media channels might uncover further interesting patterns. Additionally, it would be crucial to dive deeper into the causal mechanisms behind the moderating influence of communication channels on party communication. This article maps out differences in party agendas across various communication channels and how this relates to certain channel characteristics. Tracing the exact causal mechanisms behind these dynamics is beyond the scope of this article, but future research should focus on how exactly channel characteristics influence the communication of political actors. For example, potential future research should investigate which individual party members are most likely to deviate from the party agenda or under which circumstances the pre-structuredness of a channel constrains political actors in their communication.

Future research should also expand to add further country cases. This article focuses on typical Western European multi-party systems. Similar studies of other types of party and electoral systems as well as media systems would certainly deepen our knowledge about party competition across a wide range of political communication environments. For example, different electoral systems (e.g. weakly or strongly personalised electoral systems) may provide more or less incentives to amplify or blur central party messages in decentralised channels. Meanwhile, the type of government (e.g. single-party majority, coalition) or the rules of procedure within parliaments may influence the extent to which different government and opposition parties are constrained by the legislative agenda in parliamentary speeches.

Finally, research on the effects of issue salience for political processes and representation across different channels is required. Are there differences with regard to agenda setting dynamics and success between different channels? Investigating such questions would add valuable insights on dynamics of party competition and political representation in the rapidly changing political communication environment of contemporary democracies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (424 KB)Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and guidance. I am also very grateful to Heiko Giebler, Pola Lehmann, Christoffer Green-Pedersen, Christian Czymara, Lisa Zehnter and the participants at the ECPR General Conference 2022 in Innsbruck for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article, as well as Tobias Burst for his great input regarding the methodological approach. Furthermore, I am grateful to Juliane Hanel, Sarah Hegazy and Leonie Schwichtenberg for their fantastic research support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Replication material for this study is openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JNQUOD.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christoph Ivanusch

Christoph Ivanusch is a research fellow in the Manifesto Research Project on Political Representation (MARPOR) and the H2020 project ‘OPTED Observatory for Political Texts in European Democracies’ at the WZB Berlin Social Science Centre. Furthermore, he is a doctoral student in political science at the Berlin Graduate School of Social Sciences (BGSS), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His research interests include political parties, party competition, political communication and text-as-data. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 In the case of Switzerland, I only include texts in German.

2 Some press releases are drafted by party offices, but many are drafted by individual party members (e.g. MPs). However, the party office remains important. Even if press releases are drafted by individual party members, the press team of the party or parliamentary party group publishes them and is often given as contact for correspondence. Hence, press releases are some sort of hybrid communication channel with regard to the characteristic of centralisation and are therefore assigned the value of 0.5. Similarly, parliamentary speeches are assigned the value of 0.5. Although parliamentary speeches are held by individual MPs, in many countries parliamentary party group leaders are in firm control over the selection of speakers in legislative debates (e.g. Proksch and Slapin Citation2015).

3 The Twitter data set only includes original tweets. Similar to Barberá et al. (Citation2019) and Gilardi, Gessler, et al. (Citation2022), I exclude replies and retweets.

4 A more detailed description of the corpus and its properties is provided in Online Appendix A.1. Further information on the included Twitter accounts from individual party members is described in Online Appendix A.2.

5 The adapted codebook used in this article is displayed in Online Appendix A.3.

6 The pre-trained model is available via the HuggingFace python library (Wolf et al. Citation2020).

7 A detailed step-by-step explanation of the cross-domain application with the BERT model is provided in Online Appendix A.4.

8 Information on the manually coded ‘gold standard’ is available in Online Appendix A.5. The ‘gold standard’ consists of manually labelled press releases, parliamentary speeches and tweets from party accounts.

9 A more detailed breakdown of the model performance is given in Online Appendices A.6 and A.7.

10 Osnabrügge et al. (Citation2021), for example, also use annotated manifestos from the Manifesto Project as training data for their classification model. Their model achieves an accuracy of 41% (44 categories) and 51% (8 categories) in a cross-domain topic classification of parliamentary speeches from New Zealand.

11 Parliamentary speeches are for example not held every single month. Parliaments usually have a summer break and other longer breaks spanning multiple weeks, especially in the case of Switzerland.

12 As noted earlier, press releases are a special case with regard to the characteristic of centralisation. Some press releases are drafted by party offices, but many are drafted by individual party members (e.g. MPs) as well. In both cases, however, the press team of the party or parliamentary party group is important as they publish the press releases and are often given as contact for correspondence.

13 Online Appendix A.8 provides the overall percent for issue salience in manifestos, parliamentary speeches, press releases, tweets from party accounts and tweets from individual party members across all three countries and parties.

14 To account for potential biases resulting from limited data, I exclude those observations when a party has published less than 10 press releases, tweets or parliamentary speeches during a quarter.

References

- Alvarez, R. Michael, and Jonathan Nagler (1995). ‘Economics, Issues and the Perot Candidacy: Voter Choice in the 1992 Presidential Election’, American Journal of Political Science, 39:3, 714–44.

- Barberá, Pablo, Andreu Casas, Jonathan Nagler, Patrick J. Egan, Richard Bonneau, John T. Jost, and Joshua A. Tucker (2019). ‘Who Leads? Who Follows? Measuring Issue Attention and Agenda Setting by Legislators and the Mass Public Using Social Media Data’, The American Political Science Review, 113:4, 883–901.

- Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan N. Katz (1995). ‘What To Do (and Not to Do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 634–47.

- Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan N. Katz (1996). ‘Nuisance vs. Substance: Specifying and Estimating Time-Series-Cross-Section Models’, Political Analysis, 6, 1–36.

- Budge, Ian (2015). ‘Issue Emphases, Saliency Theory and Issue Ownership: A Historical and Conceptual Analysis’, West European Politics, 38:4, 761–77.

- Budge, Ian, and Dennis Farlie (1983). Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-Three Democracies. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Budge, Ian, David Robertson, and Derek Hearl (1987). Ideology, Strategy and Party Change: Spatial Analyses of Post-War Election Programmes in 19 Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Burst, Tobias, Pola Lehmann, Simon Franzmann, Denise Al-Gaddooa, Christoph Ivanusch, Sven Regel, Felicia Riethmüller, Bernhard Weßels, and Lisa Zehnter (2023a). manifestoberta. Version 56topicscontext.2023.1.1. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Burst, Tobias, Pola Lehmann, Simon Franzmann, Denise Al-Gaddooa, Christoph Ivanusch, Sven Regel, Felicia Riethmüller, Bernhard Weßels, and Lisa Zehnter (2023b). manifestoberta. Version 56topicssentence.2023.1.1. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson (1993). ‘On the Evolution of Political Issues’, in William Riker (ed.), Agenda Formation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 151–68.

- Chadwick, Andrew (2017). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chan, Chung-Hong, Jing Zeng, Hartmut Wessler, Marc Jungblut, Kasper Welbers, Joseph W. Bajjalieh, Wouter van Atteveldt, and Scott L. Althaus (2020). ‘Reproducible Extraction of Cross-Lingual Topics’, Communication Methods and Measures, 14:4, 285–305.

- Cox, Gary W., and Matthew D. McCubbins (2005). Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party Government in the US House of Representatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dalmus, Caroline, Regula Hänggli, and Laurent Bernhard (2017). ‘‘The Charm of Salient Issues? Parties’ Strategic Behavior in Press Releases’, in Peter Van Aelst and Stefaan Walgrave (eds.), How Political Actors Use the Media. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 187–205.

- Debus, Marc, and Jale Tosun (2021). ‘The Manifestation of the Green Agenda: A Comparative Analysis of Parliamentary Debates’, Environmental Politics, 30:6, 918–37.

- Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova (2019). ‘BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding’. arXiv:1810.04805 [Cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805.

- Döring, Herbert (1995). ‘Time as a Scarce Resource: Government Control of the Agenda’, in Herbert Döring (eds.), Parliaments and Majority Rule in Western Europe. Frankfurt: Campus, 223–46.

- Elmelund-Præstekær, Christian (2011). ‘Mapping Parties’ Issue Agenda in Different Channels of Campaign Communication: A Wild Goose Chase?’, Javnost - The Public, 18:1, 37–51.

- Enli, Gunn Sara, and Eli Skogerbø (2013). ‘Personalized Campaigns in Party-Centred Politics’, Information, Communication & Society, 16:5, 757–74.

- Gessler, Theresa, and Sophia Hunger (2022). ‘How the Refugee Crisis and Radical Right Parties Shape Party Competition on Immigration’, Political Science Research and Methods, 10:3, 524–544.

- Gilardi, Fabrizio, Lucien Baumgartner, Clau Dermont, Karsten Donnay, Theresa Gessler, Maël Kubli, Lucas Leemann, and Stefan Müller (2022). ‘Building Research Infrastructures to Study Digital Technology and Politics: Lessons from Switzerland’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 55:2, 354–9.

- Gilardi, Fabrizio, Theresa Gessler, Maël Kubli, and Stefan Müller (2022). ‘Social Media and Political Agenda Setting’, Political Communication, 39:1, 39–60.

- Green, Jane, and Sara B. Hobolt (2008). ‘Owning the Issue Agenda: Party Strategies and Vote Choices in British Elections’, Electoral Studies, 27:3, 460–76.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2007). ‘The Growing Importance of Issue Competition: The Changing Nature of Party Competition in Western Europe’, Political Studies, 55:3, 607–28.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Stefaan Walgrave (2014). ‘Political Agenda Setting: An Approach to Studying Political Systems’, in Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Stefaan Walgrave (eds.), Agenda Setting, Policies, and Political Systems: A Comparative Approach. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1–16.

- Guinaudeau, Isabelle, and Simon Persico (2014). ‘What Is Issue Competition? Conflict, Consensus and Issue Ownership in Party Competition’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 24:3, 312–33.

- Hall, Peter A., and Rosemary C. Taylor (1996). ‘Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms’, Political Studies, 44:5, 936–57.

- Hopmann, David N., Christian Elmelund-Præstekær, Erik Albæk, Rens Vliegenthart, and Claes H. de Vreese (2012). ‘Party Media Agenda-Setting: How Parties Influence Election News Coverage’, Party Politics, 18:2, 173–91.

- Ivanusch, Christoph (2023). ‘Issue Competition in Parliamentary Speeches? A Computer-Based Content Analysis of Legislative Debates in the Austrian Nationalrat’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 49:1, 203–221.

- Kam, Christopher J. (2009). Party Discipline and Parliamentary Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair (1995). ‘Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party’, Party Politics, 1:1, 5–28.

- Klüver, Heike, and Iñaki Sagarzazu (2016). ‘Setting the Agenda or Responding to Voters? Political Parties, Voters and Issue Attention’, West European Politics, 39:2, 380–98.

- Lehmann, Pola, Tobias Burst, Jirka Lewandowski, Theres Matthieß, Sven Regel, and Lisa Zehnter (2022). Manifesto Corpus. Version: 2022-1. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Lehmann, Pola, Tobias Burst, Theres Matthieß, Sven Regel, Andrea Volkens, Bernhard Weßels, and Lisa Zehnter (2022). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2022a. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Maier, Daniel, Christian Baden, Daniela Stoltenberg, Maya De Vries-Kedem, and Annie Waldherr (2022). ‘Machine Translation vs. Multilingual Dictionaries Assessing Two Strategies for the Topic Modeling of Multilingual Text Collections’, Communication Methods and Measures, 16:1, 19–38.

- Meyer, Thomas M., Martin Haselmayer, and Markus Wagner (2020). ‘Who Gets into the Papers? Party Campaign Messages and the Media’, British Journal of Political Science, 50:1, 281–302.

- Norris, Pippa, Curtice John, David Sanders, Margaret Scammell, and Holli A. Semetko (1999). On Message: Communicating the Campaign. London: Sage.

- Osnabrügge, Moritz, Elliott Ash, and Massimo Morelli (2021). ‘Cross-Domain Topic Classification for Political Texts’, Political Analysis, 31:1, 59–80.

- Peeters, Jeroen, Peter Van Aelst, and Stiene Praet (2019). ‘Party Ownership or Individual Specialization? A Comparison of Politicians’ Individual Issue Attention Across Three Different Agendas’, Party Politics, 27:4, 692–703.

- Petrocik, John R. (1996). ‘Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study’, American Journal of Political Science, 40:3, 825–50.

- Popa, Sebastian A., Zoltán Fazekas, Daniela Braun, and Melanie-Marita Leidecker-Sandmann (2020). ‘Informing the Public: How Party Communication Builds Opportunity Structures’, Political Communication, 37:3, 329–49.

- Proksch, Sven-Oliver, and Jonathan B. Slapin (2015). The Politics of Parliamentary Debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Quinn, Kevin M., Burt L. Monroe, Michael Colaresi, Michael H. Crespin, and Dragomir R. Radev (2010). ‘How to Analyze Political Attention with Minimal Assumptions and Costs’, American Journal of Political Science, 54:1, 209–28.

- Rauh, Christian, and Jan Schwalbach (2020). The Parlspeech V2 Data Set: Full-Text Corpora of 6.3 Million Parliamentary Speeches in the Key Legislative Chambers of Nine Representative Democracies. Harvard Dataverse, available at 10.7910/DVN/L4OAKN (accessed 15 May 2022).

- Russell, Annelise (2018). ‘U.S. Senators on Twitter: Asymmetric Party Rhetoric in 140 Characters’, American Politics Research, 46:4, 695–723.

- Sältzer, Marius (2022). ‘Finding the Bird’s Wings: Dimensions of Factional Conflict on Twitter’, Party Politics, 28:1, 61–70.

- Sieberer, Ulrich (2006). ‘Party Unity in Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Analysis’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 12:2, 150–78.

- Silva, Bruno Castanho, and Sven-Oliver Proksch (2022). ‘Politicians Unleashed? Political Communication on Twitter and in Parliament in Western Europe’, Political Science Research and Methods, 10:4, 776–92.

- Stier, Sebastian, Arnim Bleier, Haiko Lietz, and Markus Strohmaier (2018). ‘Election Campaigning on Social Media: Politicians, Audiences, and the Mediation of Political Communication on Facebook and Twitter’, Political Communication, 35:1, 50–74.

- Tresch, Anke, Jonas Lefevere, and Stefaan Walgrave (2018). ‘How Parties’ Issue Emphasis Strategies Vary Across Communication Channels: The 2009 Regional Election Campaign in Belgium’, Acta Politica, 53:1, 25–47.

- Wagner, Markus, and Thomas M. Meyer (2014). ‘Which Issues Do Parties Emphasise? Salience Strategies and Party Organisation in Multiparty Systems’, West European Politics, 37:5, 1019–45.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Jonas Lefevere, and Anke Tresch (2012). ‘The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:4, 771–82.

- Wolf, Thomas et al. (2020). ‘HuggingFace’s Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing’. arXiv:1910.03771 [Cs]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1910.03771.

- Wu, Shaomei, Jake M. Hofman, Winter A. Mason, and Duncan J. Watts (2011). ‘Who Says What to Whom on Twitter’, in Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on World Wide Web. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 705–714.

- Zumbach, David (2020). Swissparl: Interface to the Webservices of the Swiss Parliament. R package version0.2.1, available at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=swissparl (accessed 11 November 2021).