Abstract

Brexit was perceived as a Pandora’s box moment by both Eurosceptic and pro-integration parties in the EU, as they expected it would embolden Euroscepticism by providing a paradigm to be followed. This article explores the initial reactions of nine Populist Radical Right parties to Brexit and how they evolved in tandem with the unfolding of negotiations. It also discusses possible reasons for the differentiation in the responses of those parties, from triumphant to moderated reactions. The empirical basis is a dataset that contains the public communications of these parties on Twitter between 2015 and 2020. The results show that although there was initial differentiation with some parties calling for referenda in their own countries, by 2017 every party’s communication on Brexit drastically decreased, and by the time the UK left the EU (January 2020), calls for secession had disappeared from their discourses.

Britain’s exit from the EU was perceived as a Pandora’s box moment by both Eurosceptic and pro-integration actors (Collins Citation2017: 311), as they expected it would embolden Euroscepticism in the remaining member states by providing a paradigm to be followed. However, six years since the British vote, this ‘domino effect’ (Hobolt Citation2016) hypothesis has not materialised.

The existing literature has mostly studied Brexit’s consequences on public opinion in the EU27 (De Vries Citation2018; Hobolt et al. Citation2021; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2018), in some cases highlighting the risk of contagion (Walter Citation2021). Less studies have been conducted on the supply side. In a notable exception, Van Kessel et al. (Citation2020; see also Pirro et al. Citation2018) explore four case studies, concluding that ‘the Brexit vote thus far failed to leave a lasting mark on the strategies of PRR parties across Europe’ (ibid: 78). In this article we follow Van Kessel et al. (Citation2020) in focusing on those actors that are found to be the driving forces behind the mobilisation of contestation against the EU, namely Populist Radical Right (PRR) parties (Dolezal and Hellström Citation2016). However, we go beyond the existing literature not only by expanding the scope of study into more countries and parties, but by tracking in depth the evolution of the position of those parties vis-à-vis Brexit via Twitter feeds, i.e. direct communication with their followers. At a second stage, this allows us to scrutinise the different reactions and claims expressed by those parties in order to answer three main research questions: why did far-right parties not take protracted exit negotiations between the UK and the EU as a platform for an extended Eurosceptic campaign? What do the direct communications of these parties on social media, presumably with their followers, tell us about the rapid collapse of such efforts? Is it possible that Euroscepticism is not a core ideological element of those parties, as is often assumed, but rather a strategic component that can be downplayed when not convenient?

With regards to temporal expansion, we study the ‘entire’ Brexit saga: from 2015, the year in which the legal basis for the in-out EU referendum was established through the European Union Referendum Act (May 28), until the signature of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement on 30 December 2020.Footnote1 If the effects of Brexit on Euroscepticism operate through the assessment of the costs of exiting the EU and the comparison between the membership status quo and outside-of-the-EU-alternative (De Vries Citation2018), then assessing these effects after the new, post-exit relationship was defined is crucial. We go beyond the methodological focus of existing studies on PRR party manifestos (e.g. Van Kessel et al. Citation2020) by looking at their online communications. We believe that this better represents ‘what they said’ in the context of the rapidly evolving Brexit negotiations compared to esoteric party manifestos. In fact, in the light of its relatively low salience in the EU-27 (Kyriazi et al. Citation2023), Brexit was unlikely to be a central topic in another country’s electoral campaign. Furthermore, a well-established area of research exploring digital media and right-wing populism emphasises the centrality of online platforms for the spread of PRR parties’ messages, particularly due to the direct channels of communication with larger audiences that they offer, at least in comparison to party manifestos or speeches (de Wilde, Michailidou, et al. Citation2014).

In particular, we are interested to find out the intensity and evolution of reaction to Brexit in the discourse of PRR parties in order to assess similarities and differences between them both in terms of how often they tweeted about it but also with regards to the differences in the claims they used. By revisiting the well-known fact that Eurosceptic parties could not exploit Brexit for their cause, we can shed light on a more theoretically important question, i.e. whether Euroscepticism is a core ideological element of those parties or simply a tactical stratagem deployed whenever popular and discarded whenever inconvenient. Furthermore, elucidating these elements enables us to shed light on the mid-term ideological and programmatic evolution of Euroscepticism among the PRR parties in the second part of the 2010s, a critical moment for the European integration project marked by simmering ‘poly-crisis’ (Zeitlin et al. Citation2019).

We study the discourses on Brexit articulated by nine different PRR parties: the Party of Freedom (the Netherlands), Freedom and Direct Democracy (Czech Republic), National Rally (France), League (Italy), Flemish Interest (Belgium), Finns Party (Finland), Danish People’s Party (Denmark), Alternative for Germany, and the Freedom Party of Austria. This wide geographical scope enables us to highlight patterns of convergence and divergence in the positions of PRR parties in the 2015–2020 period. Methodologically, we have collected tweets from the official account, president and head of the EP delegation of each party. Overall, this has resulted in a dataset of 405,819 tweets, of which 1922 specifically mention Brexit or the United Kingdom.

The article is structured as follows. The second section presents our theoretical outlook and our expectations regarding the behaviour of PRR parties vis-à-vis Brexit. The third section outlines the methodological strategy, while the fourth one presents the findings of the quantitative content analysis of PRR parties’ tweets. The fifth section conducts a more in-depth, qualitative discourse analysis of the argumentative patterns underlying the Twitter activity of the studied parties and draws some comparative conclusions. The implications of the findings are discussed in the last section.

The empirical analysis indicates that, while the result of the Brexit referendum provided PRR parties with discursive resources to harden their opposition to the EU and to call for their own membership referendums, this dynamic was halted after 2017, indicating that exiting the EU was not a core issue for those parties in the way it was for the British UK Independence party. But why not? As Britain’s protracted process of leaving the EU unfolded, Eurosceptic actors dramatically decreased their communications on Brexit, while ‘secessionist’ claims, demanding further exits from the EU, mostly disappeared. In spite of Brexit occurring in the context of an already increasing politicisation of European integration, the post-Brexit five-year period in fact saw a ‘softening’ of PRR parties’ Eurosceptic positions, in line with the increasing popularity of the EU among European electorates. This suggests that PRR parties lack consistent positions and strategies on European integration (what Heinisch et al. call (Citation2021) ‘equivocal Euroscepticism’) in the face of an often-neglected capacity of the EU polity to endure in times of upheaval.

Brexit and its impact on PRRPs’ Euroscepticism

Euroscepticism is a ‘reaction to the process centre-formation at the European level’ (Treib Citation2021: 175), and therefore revolves around demands to assert the primacy of the nation-state over the EU. While European PRR parties, in line with their nativist orientations, have consistently embraced Eurosceptic positions since the turn of the twenty-first century (Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2008; Vasilopoulou Citation2018), their critiques towards the EU have come in varying degrees of opposition and have evolved over time, not necessarily in linear ways (McDonnell and Werner Citation2019). In the scholarship on Euroscepticism, Taggart and Szczerbiak’s (Citation2008: 7–8; cf. de Wilde, Koopmans, et al. Citation2014) seminal differentiation between two shades of Euroscepticism remains highly influential:

Hard Euroscepticism is where there is a principled opposition to the EU and European integration and therefore can be seen in parties who think that their countries should withdraw from membership, or whose policies towards the EU are tantamount to being opposed to the whole project of European integration as it is currently conceived […] Soft Euroscepticism is where there is not a principled objection to European integration or EU membership but where concerns on one (or a number) of policy areas lead to the expression of qualified opposition to the EU, or where there is a sense that ‘national interest’ is currently at odds with the EU’s trajectory.

We study here whether Brexit was a potential inflection point that could demonstrate the intensity and resilience of any Euroscepticism. As Brexit provided an opportunity for emulation and a paradigm for imitation for other Eurosceptic parties, we could expect to see these parties ‘harden’ their Eurosceptic stance after Brexit. If these parties were bona fide ‘hard’ Eurosceptic, they should be expected to intensify their attacks on the EU post-Brexit. Instead, if these parties are more strategically minded with regards to European integration, we should expect them to concentrate their actions around the time of Brexit and then have their interest wane as the complications of the exit and the dragging on of the negotiations emerged.

In short, there is an argument that Brexit had the potential to ‘harden’ Euroscepticism, even leading to openly ‘secessionist’ positions. We ground this hypothesis on previously publicised mechanisms. On the one hand, as argued by De Vries’s ‘benchmark theory’ (2018: ch. 2; see also Malet and Walter, Citation2023), positions towards European integration are rooted in a comparison between the benefits of remaining within the EU with those associated with an alternative state of one’s country outside the bloc. A disintegrative event like Brexit hence, by providing new information on the advantages and disadvantages of EU membership, had the potential to alter existing actors’ preferences. Of course, the operation of this mechanism in a disintegrative direction depended on how Brexit would actually develop as well as how principled the actors are in their opposition to European integration.

An additional factor that could promote expansion of Euroscepticism by PRRs is one recognised by scholars of international cooperation, showing that referendum outcomes rejecting international agreements or the electoral success of political leaders with disintegrative agendas may trigger a domino effect by encouraging integration-sceptic voters in other countries (Malet Citation2021; Walter et al. Citation2018). This research builds upon the broader literature on ‘party policy diffusion’, which shows how policy agendas diffuse between parties across national borders (Giani and Méon Citation2021; Senninger and Bischof Citation2018). The mechanisms of diffusion might result from both cognitive learning processes about new courses of action taken by other actors as well as the increased legitimacy of previously marginal policy options (Wolkenstein et al. Citation2020). In any case, the expectation is that, when other internationally relevant actors adopt a certain policy stance, imitation by ideologically close parties seeking to gain reputation by association is facilitated. In the emerging literature on EU disintegration in fact, PRR parties’ cross-national radicalisation is envisaged as the main driver of the Union’s collapse (Hodson and Puetter Citation2019).

However, this mechanism can suggest that the opposite effect might be observed if voters turn on disintegrative practices after witnessing the debacle of Brexit. As such, if the parties were not principled on Eurosceptic positions, but instead started from differing degrees of Euroscepticism (Whitaker and Lynch Citation2014; cf. Falkner and Plattner Citation2020) and retained some flexibility on their positions (Heinisch et al. Citation2021; McDonnell and Werner Citation2019), we would expect a gradual ‘softening’ of their positions. As such, we investigate the evolution of Brexit discourse of PRR as an indicator of whether those parties act in a principled or strategic manner with regards to European integration.

Indeed, the literature on Euroscepticism has discussed how PRR parties are particularly prone to strategically modify their discourses in crisis moments (Pirro and van Kessel Citation2017). In the EU context, postfunctionalists have argued that the mobilisation of citizens’ concerns regarding EU integration depends primarily on the strategic capacities of PRR entrepreneurs to do so (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 18–21). However, this would be compatible with an account that stresses policy entrepreneurship (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012). These parties found a niche issue and occupied fringe positions to attract voters. As those parties grew and the issue became more salient, if they were only utilising the issue of European integration strategically, we would expect them to soften or entirely drop their EU opposition. Empirical evidence shows that PRR parties hardened their Eurosceptic discourses in response to the euro and refugee crises, as the EU’s handling of those crises became more controversial (Braun et al. Citation2019; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2016; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2018). However, crises may not only cause damage to the EU’s reputation, but also uplift it, as was the case of Brexit where the UK’s failed gambits of division compared poorly to the EU’s more concentrated and consistent strategy of negotiations (Laffan and Telle Citation2023). Evidence shows that popular opinion turned more Europhile in most EU countries post-Brexit and hence a strategic actor might be disinclined to insist on a position that wanes in popularity. As such, the evolution of the Brexit discourse should demonstrate the actual relationship of those parties to Euroscepticism, i.e. whether it is a principled or strategic one.

A final issue concerns the differences between the parties. If it turns out that some parties are more persistent than others, what could explain this difference? We posit that the main factors should be each party’s Eurosceptic trajectory first of all – parties like UKIP that were forged almost entirely on the European issue should be expected to be more hard line and principled than parties that were more recently ambivalent about the EU. Additionally, the effect of the accumulation of crises and the positions of the parties should also be relevant factors. We would expect more affinity towards Brexit in the epicentres of the economic and refugee crises that hit Europe, i.e. in the European South, where the EU’s image was more battered by years of painful crises. Conversely though, we would expect a more strategic and soft behaviour from parties that are larger and can claim participation in government; they would have an incentive both to moderate their discourse and not disturb their path to power too much by opposing an increasingly popular EU within the timeframe of our study.

Data and methodology

Against this background, and understanding that discourse is strategically used by actors to reconfigure their interests and identities and thus can explain political change (Schmidt Citation2001), this article studies how PRR parties reacted to the key moments of the Brexit process by analysing their communication on the microblogging platform X (formerly and still colloquially known as Twitter). The study relies on a novel datasetFootnote2 of the posts (known as ‘tweets’) that nine European far-right parties published on this platform between 2015, that is one year before the referendum on the UK’s membership to the EU was celebrated (June 26 2016), until 2020, the year in which the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement was signed on 30 December. The signing of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement is relevant to our study because it defined the terms of the post-exit relationship between the UK and the EU, including a Free Trade Agreement, a close partnership in citizenship’s security, and a governance framework, and thus provided a first picture of the advantages and disadvantages that the UK would face vis-à-vis its pre-exit status. In turn, the starting date of our time frame responds to the fact that in 2015 the legal basis for the membership referendum was established through the European Union Referendum Act, and campaign groups for and against the EU were formed.

Since we are interested in the Brexit-related discourse of the most Eurosceptic parties, we follow a most-likely case selection logic and focus on those parties that are part of the Identity and Democracy (I&D) group in the EP,Footnote3 which is considered the most Eurosceptic political group present in the institution. In contrast to I&D, the other Eurosceptic EP group, that of the European Conservative and Reformists (ECR), did not officially support the leave option in the Brexit referendum (Euractiv Citation2016). For each political party that we study, the dataset gathers the tweets and re-tweets made by the party’s official account, the president of the party and the head of its European Parliament’s delegation (see ).

Table 1. List of post-holders examined.

The empirical analysis proceeds in three steps. First, using ‘Brexit’, ‘UK’ and ‘United Kingdom’ (the last two translated into the domestic languages) as key words, a dataset with those tweets related to Brexit has been created.Footnote4 Based on this, the next section ‘The salience of Brexit’ describes the evolution over time of the salience of Brexit in the Twitter communication of the studied parties; in order to gauge the salience of Brexit better, we compare the share of tweets relating to Brexit with those relating to refugees. This is done because it helps place Brexit into some perspective, as refugees and immigration constitute a central topic in these parties’ discursive strategies after 2015, when the refugee crisis broke out (Gianfreda Citation2018). As a second step, the section ‘Claim analysis’ is devoted to developing a quantitative content analysis of the claims addressed by PRR parties when communicating on Brexit. Political claims aim at drawing attention to certain aspects of reality while leaving others in the dark, thereby supporting or undermining broader political standpoints held by opposing actors. In terms of operationalisation, claims can be identified as pieces of text ranging from a few words to several paragraphs (de Wilde, Koopmans, et al. Citation2014: 2). In this article, given our focus on Brexit’s implications for EU integration, claims are conceived as textual units in which (1) an actor presents (2) a political argument regarding (3) Brexit’s nature and/or consequences. If any of these three elements is lacking, we do not identify a claim. The categories used for the claim analysis were developed in a data-driven, inductive manner, whereby categories emerge from the analysed content in an iterative process (see ). Following de Wilde, Koopmans, et al. (Citation2014: 8), we coded as claims, apart from explicit arguments, descriptions of facts that directly relate to one of our substantive issue areas (see ). In case the unit of text is only a statement of fact without normative connotation, we coded in the category ‘Procedural/Factual’. The exercise was limited to one claim per tweet due to the brevity of tweets. In a few cases we coded multiple claims but chose, for the purposes of quantitative analysis, to focus on the ‘main’ claim that we judged was closest to the tweet’s substance. The dataset was coded manually by two coders (two of the authors of this article). To assess inter-coder reliability, each coder coded the same 336 randomly selected tweets out of total 1239 tweets (after removing irrelevant ones). This resulted in a percent agreement at 93%, in an average Krippendorff’s alpha of 0.92, and in a Brennan & Prediger Kappa at 0.92, which indicates acceptable reliability (Krippendorff Citation2004: 242, Landis and Koch Citation1977).

Table 2. Claims on Brexit, tweets by RPP parties.

This quantitative comparison of the distribution of textual contents across time and party allows for the distillation of textual trends, but it fails to capture the latent meanings, emphases and contexts underlying textual data. For this reason, in a third step, a qualitative discourse analysis, inspired by the flexible framework developed by Lynggaard (Citation2019), is conducted. The aim of this third exercise is to interpret how the various aspects related to an issue or a viewpoint on Brexit evolved (or not) over time or, in other words, how the perceptions of Brexit’s potential lessons and weaknesses, or evasion thereof, are highlighted at different points in time by the PRR parties. The qualitative analysis of the tweets has been triangulated with the reading of other official documents from the parties and secondary literature.

Quantitative content analysis

The salience of Brexit

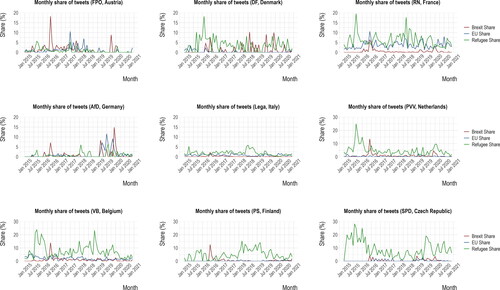

presents the development of tweets overall and for each party during the years from 2015 to 2020 for three indicators – (a) the monthly share of tweets on Brexit, (b) the monthly share of tweets on the EU and (c) the monthly share of tweets on refugees, another hot topic for the PRR. The solid red line in the graphs describes the chronological evolution of the share of tweets on Brexit, the blue line represents the evolution of the share of tweets on the EU and the green one the share of tweets on refugees.

Over the six years, about 0.4% of the tweets are related to Brexit (all nine parties combined). When we come down to individual parties, FPO outperforms the others with 1.6% of all its tweets on Brexit, while only 0.11% of Lega’s tweets covered Brexit. Compared with Brexit, the EU is a more focal topic for these parties, with 1.3% of all the tweets being about it and both topics are dwarfed by most parties’ focus on refugees and immigration, with the exceptions of the FPO and AfD. Among the nine parties, RN tweets most about the EU with 3.7% of its tweets over the 6 years, while PVV has the lowest share at 0.25%.

As the first graph in shows, the share of Brexit-related tweets (red line) initially peaked in June 2016 for all parties when the UK-wide referendum took place. All parties combined, roughly 6.3% of their tweets were about Brexit in that month. For most parties, after the referendum, the share of tweets on Brexit quickly dwindled and only resurfaced in 2019, either during the EP elections of that year or in the weeks before the ratification of the EU-UK withdrawal agreement in January 2020, suggesting a ‘strategic’ behaviour on their part, trying to draw any benefits from the event itself and then withdrawing from commenting on it when things turned sour for their side. Seven out of the nine parties followed a similar pattern and peaked in June 2016, but the scale of their Twitter activity varied in that month. The two exceptions are AfD in Germany and DF in Denmark. AfD, similar to the other seven parties, tweeted more about Brexit in June 2016 and its tweets on Brexit sharply decreased. However, AfD scaled up its activity and peaked in late 2019 with an even higher share of tweets on Brexit vis-à-vis that of June 2016. Regarding DF, again, like other parties, DF talked more about Brexit during the referendum month, but its tweets on Brexit increased afterwards and peaked several times in 2018 and 2019.

Claim analysis

The frequency of the claims used by PRR parties in their tweets on Brexit is shown in . We differentiate between claims on the substantive themes that PRR parties considered relevant to interpret Brexit (economy, democracy and immigration), and claims on the implications of Brexit for the continued existence of the EU polity (imitational, cautionary and celebratory).Footnote5 We also add a category termed ‘procedural/factual’ to refer to descriptive comments on the EU-UK negotiations and other Brexit proceedings.

Overall, we first note how less than two-thirds of the tweets have a claim (on Brexit), as many of them are statements without an argumentative line and links to articles without further comment. Among those tweets with a claim, we see populist/democratic and economic claims are the most popular ones, the former focusing on Brexit as the vindication of popular will against the EU’s elitism and the latter mostly as celebratory tweets noting that despite Brexit the UK’s economy had not collapsed, but was actually growing. Finally, a third type of claim on Brexit made by PRR parties relates the UK’s EU departure to immigration problems. However, it needs to be stressed the comparatively small number of tweets linking Brexit to EU immigration policy, a surprising fact given that this issue constitutes the core of the political supply of Eurosceptic parties (Chopin et al. Citation2019) and, as shown in , a very frequent topic in their tweets.

With regards to polity-related claims, a smaller share, around 12.5% of tweets, call for further exits/imitation, whereas a close, but ‘softer’ relative are cautionary claims, which argue that the EU should consider re-nationalising reforms to avoid more Brexit-like incidents from occurring. Finally, another share of tweets is simply celebratory, focusing on congratulating the UK for its move towards Brexit.

breaks down the distribution of claims by party. It shows that there are relevant differences between what different parties stress. Rebuking what they feel is the economic case against Brexit is a theme invoked by all parties, but the PVV and Lega particularly deploy it the most. Additionally, we see that the argument that Brexit constitutes a demonstration of democratic vitality is reproduced unevenly but consistently by all parties, with the sole exception of the PVV and partially the DF and FPO which have consistently used this populist frame less.

Table 3. Distribution of claims by party.

Where they diverge however is the rest of the categories. Talk of further exits and potential own country secession from the EU is most pronounced in the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and France, where PRR parties are most unapologetically Eurosceptic and openly advocated using Brexit as a template for their own country. The opposite is true for countries where secession arguments were scarce, particularly Finland and Germany, where a more ‘reformist’, the ‘EU has to change’ line is selected by those parties. Finally, the Danish DF only seems to produce somewhat formal tweets on the issue, celebrating UK results or chastising the negotiation process, but rarely substantively framing Brexit. The following section delves further into these differences.

Qualitative discourse analysis

How did PRR parties interpret the referendum’s result?

The Brexit referendum was welcomed in triumphant tones among most PRR parties. However, within the triumph, although there were those parties who invoked Brexit directly as an example to imitate, others took a more alarming approach, interpreting Brexit as a warning sign. A number of parties, including the Lega, PVV, RN, VB, SPD and FPO called immediately for local referendaFootnote6 (see ). A minority of parties, including the AfD, the True Fins and Danish People’s Party congratulated the British conservatives but abstained from calling for membership votes in their countries.

Table 5. Reactions of PRR parties to brexit’s key dates.

The main factor behind this dichotomy in reactions, which also demonstrates the strategic dimension of Euroscepticism in PRR parties’ discourse, is their position in their domestic systems. Whereas the first group of parties that explicitly asked for a referendum in their countries were in the opposition, in the second group of parties, two of them (the Scandinavian ones) were sustaining their respective governments in parliament. As such, one might possibly assume that they were more constrained and encumbered by the burden of responsibility; they needed not to estrange the government parties they supported and not create an issue for their coalition. Those constraints did not exist for the AfD, but at that point the party was relatively new, it was in the middle of a transition to a different Euro-parliamentarian group and a leadership change had recently occurred that left the question of its position towards Europe hanging.

Other possible factors, such as the relationship of each country to the UK economically or the trajectory of Euroscepticism in the past of those parties do not seem to sufficiently account for their initial position. While the large volume of trade between the UK and Germany might have hindered the AfD’s celebratory mood on Brexit, it should have been the same for the PVV or the RN, who operate in countries whose economy would be greatly affected. Nevertheless, no such inhibition appears in their initial statements.

The different historical Eurosceptic trajectories of the PRR parties may also contribute to the different reactions to Brexit. Their past positions might have had an effect, but it seems this does not correspond neatly with the divide between parties who asked for a national referendum and those who did not. The Lega was once a party that was more accepting of the EU as a vehicle for regional autonomy, but this tendency did not survive the party’s transformation into a national party and its growth outside the confines of Northern Italy.

Neither does the geographic distribution of reactions indicate a link between the crises that pummelled the EU in the past decade and Euroscepticism. Parties from both the most afflicted countries in terms of economic and migratory shocks (Italy) and the least affected ones (the Netherlands) share the same position. As such, it seems that it is the contextual position of the parties, i.e. their position in government or opposition and the potential benefit from riding on the coattails of Brexit as it happened that mostly predicts their reaction.

However, beyond the fact that this type of qualitative analysis cannot sharply trace causal factors, we also do not want to exaggerate the differences between the parties. Even the ‘hardest’ Eurosceptic parties showed in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum what Heinisch et al. (Citation2021: 192) define as ‘equivocal Euroscepticism’, that is, an ‘inherently ambivalent stance that, in terms of rhetoric and behaviour, includes aspects that are both hard and soft Eurosceptic’. Equivocal Euroscepticism does not mean an ambiguous position based on vague communication but a rather ambivalent discourse in which calls for withdrawal are intertwined with calls for reform.

An example of this discursive pattern is provided by the Twitter activity of the Lega’s leader, Matteo Salvini. On 24 June 2016, he declared that the Euro was an experiment reaching its end, and on referendum day, he posted that ‘the British have chosen Brexit, now it’s our turn’. It is not entirely clear how serious he was about triggering Italy’s exit though, as in another tweet on the same day he claimed that he was in favour of ‘rewriting European rules, but if nothing changes other countries will exit’. Immediately afterwards, he claimed that the current EU was antithetical to actual ‘European values’ as he defines them. In the following days though, he often referred to it with proclamations like ‘Brexit: Liberty!’, implying that it could be an example to copy. However, rather than ask for an Italian exit, his focus was mostly on causing the ‘Renzi’ exit, relegating the Brexit event onto the plane of a domestic dispute. Overall, the dominant elements of his tweets during that time were an ambivalent stance towards the meaning of this for Italy (as a springboard to push change or as a model to follow) and a tendency to link Brexit to target domestic politicians and his template of populist politics. As such, the differences between outright imitation and calls for reform did exist to a degree, but they also alternated flexibly within the discourse of the more ‘hard-line’ parties.

How PRR parties framed the Brexit negotiations

From 2017 onwards, the differences between the two groups faded, since the more ‘hard-Eurosceptic’ parties stopped interpreting Brexit in terms of a secessionist lesson for their own countries. Instead, PRR parties focused on defending the UK government, criticised the bargaining strategy of the EU and its ‘vengeful’ nature or the stance of their own governments and finally commented on the desired Brexit model, which was the only point of departure.

For instance, the PS framed the EU’s negotiatory response as a ‘revenge’ (PS, 7 December 2020) which sought to ‘punish’ the UK for its decision to leave the Union. The PVV, meanwhile, defended the less conciliatory UK’s positions on a wide range of Brexit-related topics: Gibraltar, the EU-UK future security relations, the US-UK trade deal, the UK’s post-2019 financial payments, and the successive postponements asked by the British governments to implement Brexit. Both the SPD and the VB, in turn, lauded those member states’ governments (the Czech and Polish, according to the Flemish Party) that attempted to establish bilateral negotiations with the UK, thus seeking to undermine the EU’s centralised negotiating strategy, while the DF lamented that the Danish government did not stand up for its major trading partner.

One point in which PRR parties showed different opinions during the negotiations was the desired Brexit model. On the one hand, some of them (AfD, FPO, PVV, SPD) tweeted to defend the ‘hard Brexit’ (no-deal) option. For instance, the AfD argued that ‘the UK trades with China and the US under WTO rules. And without a deal, they also apply to trade with the EU. Problem? Nope. #Brexit’, so the party was ‘wishing for a clean Brexit. Free trade does not need agreements. It’s better to be full out than half in’ (27 November 2017). However, on the other hand, VB and RN warned against the consequences of a hard Brexit and abstained from defending the no-deal option. For instance, VB argued that the hard Brexit option was being pushed by the EU in order to punish the UK, and this was against Flemish interests: ‘The “hard Brexit” strategy of this EU-elite smells like revenge. This is a scandal and contrary to our own interest!’ (9 October 2016). Others, like the DF and Lega, shied away from the question in general and avoided doing more than commenting and updating their audiences on the proceedings of Brexit.

In total, there are some differences in the behaviour of the parties, but this should be noted against the backdrop of a massive fall in the interest for Brexit. Whatever arguments remain become more procedural, commenting on aspects of the negotiation, as shown in . Especially after the French elections of 2017, where the RN tried and failed to campaign on European issues as a major part of its platform, the rest of the PRR parties presumably understood the issue provided little electoral benefit. Indeed, as can be seen in , for many of those parties there is a significant uptick in discourse about migration at the same time as EU and, to a lesser extent, Brexit fade out of their political horizon (see for example the PS, SPD, Lega and VB – even if others did not necessarily follow the same trend, as the AfD and the DF).

Table 4. Yearly frequency of claims.

Assessments of the actual departure in 2020

We have already pointed out that all types of claims diminish in frequency after 2016, as Brexit becomes less relevant in domestic public debates (). However, some claims do so more than others. For example, as shown in , 67% of the secession-themed tweets were published in 2016, while the next biggest share of tweets in that year belonged to celebratory tweets, with 58% of those published in 2016. In 2016, the mood was celebratory, and there was talk of imitating Britain.

As we progress through the Brexit process, this mood evaporates. In 2017 and 2018, economic tweets grew in proportion, trying to justify the Brexit choice. In 2019, most parties tweeted about Brexit around the time of the British election, and hence most of the tweets were of the populist/democratic category, heralding the 2019 win of the Conservatives as the final word of the people on Brexit and the final defeat of the Eurocrats. Fully 43% of tweets in 2019 belong to the populist/democratic category. In 2020 though, when Brexit actually happens, the type of argumentation swings again, this time towards cautionary tweets, which are the dominant category for the last year we examined, along with economic ones again, each comprising approximately a quarter of Brexit-related tweets for 2020.

As shows, the PRR parties’ reactions to the actual departure of the UK from the EU on 31 January 2020, following the ‘Withdrawal Agreement’ signed between the UK and the EU on 24 January 2020, were less energetic than those displayed 5 years before when the referendum’s results were known. In early 2020, calls to emulate Brexit have disappeared from the rhetoric of PRR parties: secessionist claims were eclipsed within their discourses, dropping from 23% of total tweets in 2016 to only 3% in 2020. In our dataset, only the PVV and the SPD sparingly call for ‘Nexit’ and ‘Czexit’ in 2020.

In the year that followed, while the Withdrawal Agreement ensured a transition period for the rest of 2020 in which trade, travel and freedom of movement remained largely unchanged, PRR parties’ communications on Brexit virtually disappeared, tweeting only occasionally on the UK’s good economic fortunes but rarely on the trade negotiations between the UK and the EU. Indeed, when the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement was finally agreed upon on 24 December 2020, most of the parties decided not to tweet about the event. In our dataset, only the Lega and the True Finns congratulated the British government on the agreement, but did not draw any conclusions for their own countries from it.

Overall, the stance of PRR parties on Brexit changed from a triumphant one in 2016, which viewed Brexit as a model to be imitated, to a defensive one in 2017 and 2018, as they tried to defend against the proposition that Brexit would harm the UK economy. Finally, they reverted to a more aggressive discourse, but without as much mention of secession, in the final months of 2019 only to finally assume a more conciliatory tone by 2020, stressing the opportunities Brexit provides for the future economic cooperation and the fact that the EU should learn from this incident.

Discussion and conclusions

Both in the academic and public debates, the departure of the UK from the EU was perceived, in June 2016, as the dramatic culmination of a whole range of other crises and challenges –the aftermath of the eurozone and refugee crises, surging right-wing nationalism, growing geopolitical uncertainty in its immediate neighbourhood and beyond, simmering economic problems, democratic backsliding in Hungary and Poland– that appeared to question the sustainability of the integration project (see, e.g. Krastev Citation2017). Indeed, the 2014 EP elections produced a more Eurosceptic cohort of MEPs than ever before: approximately 28 per cent of the elected representatives identified themselves as Eurosceptic (Treib Citation2014). PRR parties consolidated these results in the 2019 EP elections (Treib Citation2021).

In this article we set out to analyse how PRR parties in the EU-27 reacted to this moment of deep political crisis as epitomised by Brexit, track differences in their reactions and understand whether their Euroscepticism is strategic or principled. Our empirical data provide evidence that PRR parties utilised Euroscepticism as a wedge issue during the brief moment that Brexit shook the world; particularly the ones not burdened by any government responsibility quickly urged other European electorates to imitate the UK. But this was a short-lived flurry of activity that quickly receded. We asked why the negotiations were not utilised as a platform for deepening Euroscepticism and the answer seems to be that as the intricacies of the UK’s departure became more apparent and the future projection of Brexit and its associated issues started to manifest themselves in actual reality, enthusiasm for imitation faded rapidly. The initial persistent calls for membership referendums in their own countries, while heralding the collapse of the EU at the same time, were followed by a protracted silence and more moderate stances. This equivocal discourse on EU integration by PRR parties arguably demonstrates the usefulness of analysing the direct communications of these parties on social media: studying the discourses of these parties based solely on their formal programmes, as previous studies have done (van Kessel et al. Citation2020), assumes that these parties are hard-headed programmatic actors, when in fact their strategies are heavily driven by salient events and fluctuations in public sentiment. Social media instead demonstrates that the initial Eurosceptic noise was replaced by a fast retreat from action when negotiations became too complicated and their outcomes difficult to fit into soundbites.

Therefore, in line with the concept of ‘equivocal Euroscepticism’ (Heinisch et al. Citation2021), we have provided evidence that responds to one of our initial questions, namely whether Euroscepticism was principled or strategic. It appears these parties acted strategically, advocating an exit when the tide was high and Europe was shocked by Brexit, while retreating from it when problems became apparent and the issue of Europe was no longer seen as an electoral winner. Our data show how PRR parties display ample flexibility on European integration, developing their stances in a rather ad hoc and opportunistic manner, shifting positions if necessary.

What are the theoretical and practical implications of these findings for future research on Euroscepticism? The reasons behind the observed discursive evolution of PRR parties in the studied period go beyond Brexit-related developments, since they are manifold and, to a great degree, country specific. For instance, between 2015 and 2020 several of the parties studied entered national governments as junior coalition partners (Austria, Italy, Finland) or entered parliamentary majorities backing governments (the Netherlands), a factor that research suggests provides incentives for the moderation of PRR parties (Berman Citation2008; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2013; cf. Albertazzi Citation2009). As we saw, during the initial wave of calls to imitate parties, it was only the ones participating, directly or indirectly, in a national government that refrained from calling for a local referendum. Relatedly, research shows that party positions (including Eurosceptic ones) on European integration are highly determined by inter-party competition dynamics at the domestic level (Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2008).

Finally, one could hypothesise that the PRR parties’ differences in relation to the Brexit question uncovered by this article reflect different levels of public support for the EU in their respective countries. However, a preliminary analysis of the available data indicates no direct correlation between the ‘hardness’ of the Euroscepticism of each PRR party, its historical trajectory, and the level of support for EU integration among their fellow citizens: for instance, the Dutch and Belgian populations are among the least Eurosceptic (European Commission Citation2021: 88), but their corresponding PRR parties articulated some of the most radical discourses in relation to Brexit. Further research is needed to explore these potential explanations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the three reviewers, the editors and Waltraud Schelkle, Giorgio Malet and Joseph Ganderson for their helpful comments on earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joan Miró

Joan Miró is Assistant Professor in EU Politics & Policy at Pompeu Fabra University. His research interests lie in European integration, particularly the socioeconomic governance of the EMU, social policy, and international political economy. [[email protected]]

Argyrios Altiparmakis

Argyrios Altiparmakis is a Research Fellow at the European University Institute. His research focuses on party politics, political behaviour and the recent European crises. He is currently working on the SOLID-ERC project. [[email protected]]

Chendi Wang

Chendi Wang is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He works in comparative politics, political economy, political behaviour, and political methodology. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 At the time of writing, many uncertainties are still surrounding the final shape of Brexit, including the thorny issue of the Irish border and several aspects of the trade relationship between the UK and the EU.

2 The dataset is available from the authors.

3 One party member of the I&D group, the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia, has not been included the analysis because it was not present on Twitter during the studied period.

4 To translate the tweets of the four parties (Flemish Interest, Party of Freedom, Finns Party, and Freedom and Direct Democracy) whose language we do not speak, we used automatic translator DeepL.

5 The dataset with all 1239 relevant tweets and associated claims is available upon request.

6 See the press releases on calling for membership referendums by the VB (https://www.vlaamsbelang.org/persberichten/2659), the FPO (https://www.wiwo.de/politik/europa/grossbritannien-wie-der-brexit-ploetzlich-mehrheitsfaehig-wird/13444840.html?utm_source=twitterfeed&utm_medium=twitter) and the PVV (https://www.pvv.nl/36-fj-related/geert-wilders/9601-heteuropadatwijwillen.html). Last accessed 2 January 2024.

References

- Albertazzi, Daniele (2009). ‘Reconciling “Voice and Exit”: Swiss and Italian Populists in Power’, Politics, 29:1, 1–10.

- Berman, Sheri (2008). ‘Taming Extremist Parties: Lessons from Europe’, Journal of Democracy, 19:1, 5–18.

- Braun, Daniela, Sebastian Adrian Popa, and Hermann Schmitt (2019). ‘Responding to the Crisis: Eurosceptic Parties of the Left and Right and Their Changing Position towards the European Union’, European Journal of Political Research, 58:3, 797–819.

- Chopin, Thierry, Niccolò Fraccaroli, Nils Hernborg, and Jean-Francois Jamet (2019). ‘The Battle for Europe’s Future: Political Cleavages and the Balance of Power Ahead of the European Parliament Elections’, Policy Paper 237. Institute Jacques Delors.

- Collins, Stephen D. (2017). ‘Europe’s United Future after Brexit: Brexit Has Not Killed the European Union, Rather It Has Eliminated the Largest Obstacle to EU Consolidation’, Global Change, Peace & Security, 29:3, 311–6.

- De Vries, Catherine E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- De Vries, Catherine E., and Sara B. Hobolt (2012). ‘When Dimensions Collide: The Electoral Success of Issue Entrepreneurs’, European Union Politics, 13:2, 246–68.

- de Wilde, Pieter, Ruud Koopmans, and Michael Zürn (2014). ‘The Political Sociology of Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism: Representative Claims Analysis’, Discussion paper no. SP IV 2014-102. Berlin: WSV Berlin Social Science Centre.

- de Wilde, Pieter, Asimina Michailidou, and Hans-Jorg Trenz (2014). ‘Converging on Euroscepticism: Online Polity Contestation during European Parliament Elections’, European Journal of Political Research, 53:4, 766–83.

- Dolezal, Martin, and Johan Hellström (2016). ‘The Radical Right as Driving Force in the Electoral Arena?’, in Swen Hutter, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi (eds.), Politicising Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 156–80.

- Euractiv (2016). ‘ECR chief backs Brexit’, March 11.

- European Commission (2021). ‘Public Opinion in the European Union’, Standard Eurobarometer 94.

- Falkner, Gerda, and George Plattner (2020). ‘EU Policies and Populist Radical Right Parties’ Programmatic Claims: Foreign Policy, Anti-Discrimination and the Single Market’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58:3, 723–39.

- Gianfreda, Stella (2018). ‘Politization of the Refugee Crisis? A Content Analysis of Parliamentary Debates in Italy, the UK, and the EU’, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 48:1, 85–108.

- Giani, Marco, and Pierre-Guillaume Méon (2021). ‘Global Racist Contagion Following Donald Trump’s Election’, British Journal of Political Science, 51:3, 1332–9.

- Heinisch, Reinhard, Duncan McDonnell, and Annika Werner (2021). ‘Equivocal Euroscepticism: How Populist Radical Right Parties Can Have Their EU Cake and Eat It’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:2, 189–205.

- Hobolt, Sara (2016). ‘The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, A Divided Continent’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23:9, 1259–77.

- Hobolt, Sara, Sebastian Adrian Popa, Wouter van der Brug, and Hermann Schmitt (2021). ‘The Brexit Deterrent? How Member State Exit Shapes Public Support for the European Union’, European Union Politics, 23:1, 100–19.

- Hodson, Dermot, and Uwe Puetter (2019). ‘The European Union in Disequilibrium: New Intergovernmentalism, Postfunctionalism and Integration Theory in the post-Maastricht Period’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:8, 1153–71.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks (2009). ‘A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science, 39:1, 1–23.

- Krastev, Ivan (2017). After Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Krippendorff, Klaus (2004). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Kyriazi, Anna, Argyrios Altiparmakis, Joseph Ganderson, and Joan Miró (2023). ‘Quite Unity: Salience, Politicisation and Togetherness in the EU’s Brexit Negotiating Position’, West European Politics, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2264717.

- Laffan, Brigid, and Stefan Telle (2023). The EU’s Response to Brexit: United and Effective. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Landis, J. Richard, and Gary G. Koch (1977). ‘The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data’, Biometrics, 33:1, 159–74.

- Lynggaard, Kenneth (2019). Discourse Analysis and European Union Politics. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Malet, Giorgio (2021). Cross-National Social Influence: How Foreign Votes Can Affect Domestic Public Opinion. Zürich: University of Zurich.

- Malet, Giorgio, and Stefanie Walter (2023). ‘Have Your Cake and Eat It, too? Switzerland and the Feasibility of Differentiated Integration after Brexit’, West European Politics, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2192083

- McDonnell, Duncan, and Annika Werner (2019). ‘Differently Eurosceptic: Radical Right Populist Parties and Their Supporters’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:12, 1761–78.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pirro, Andrea L. P., Paul Taggart, and Stijn van Kessel (2018). ‘The Populist Politics of Euroscepticism in Times of Crisis: Comparative Conclusions’, Politics, 38:3, 378–90.

- Pirro, Andrea L. P., and Stijn Van Kessel (2017). ‘United in Opposition? The Populist Radical Right’s EU-Pessimism in Times of Crisis’, Journal of European Integration, 39:4, 405–20.

- Rohrschneider, Robert, and Stephen Whitefield (2016). ‘Responding to Growing European Union-Skepticism? The Stances of Political Parties toward European Integration in Western and Eastern Europe following the Financial Crisis’, European Union Politics, 17:1, 138–61.

- Senninger, Roman, and Daniel Bischof (2018). ‘Working in Unison: Political Parties and Policy Issue Transfer in the Multilevel Space’, European Union Politics, 19:1, 140–62.

- Schmidt, Vivien A. (2001). ‘The Politics of Economic Adjustment in France and Britain: When Does Discourse Matter?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 8:2, 247–64.

- Szczerbiak, Aleks, and Paul Taggart (2008). ‘Theorizing Party-Based Euroscepticism: Problem of Definition, Measurement and Causality’, in Aleks Szczerbiak and Paul Taggart (eds.), Opposing Europe? The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism: Volume 2: Comparative and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 238–62.

- Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak (2008). Opposing Europe? The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism, Volume 1: Case Studies and Country Surveys. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak (2013). ‘Coming in from the Cold? Euroscepticism, Government Participation and Party Positions on Europe’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 51:1, 17–37.

- Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak (2018). ‘Putting Brexit into Perspective: The Effect of the Eurozone and Migration Crises and Brexit on Euroscepticism in European States’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:8, 1194–214.

- Treib, Oliver (2014). ‘The Voter Says No, but Nobody Listens: Causes and Consequences of the Eurosceptic Vote in the 2014 European Elections’, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:10, 1541–54.

- Treib, Olivier (2021). ‘Euroscepticism Is Here to Stay: What Cleavage Theory Can Teach Us about the 2019 European Parliament Elections’, Journal of European Public Policy, 28:2, 174–89.

- Van Kessel, Stijn, Nicola Chelotti, Helen Drake, Juan Roch, and Patricia Rodi (2020). ‘Eager to Leave? Populist Radical Right Parties’ Responses to the UK’s Brexit Vote’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22:1, 65–84.

- Vasilopoulou, Sofia (2018). ‘The Radical Right and Euroskepticism’, in Jens Rydgren (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 122–40.

- Walter, Stefanie (2021). ‘EU-27 Public Opinion on Brexit’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 59:3, 569–88.

- Walter, Stefanie, Elias Dinas, Igancio Jurado, and Nikitas Konstantinidis (2018). ‘Noncooperation by Popular Vote: Expectations, Foreign Intervention, and the Vote in the 2015 Greek Bailout Referendum’, International Organization, 72:4, 969–94.

- Whitaker, Richard, and Philip Lynch (2014). ‘Understanding the Formation and Actions of Eurosceptic Groups in the European Parliament: Pragmatism, Principles and Publicity’, Government and Opposition, 49:2, 232–63.

- Wolkenstein, Fabio, Roman Senninger, and Daniel Bischof (2020). ‘Party Policy Diffusion in the European Multilevel Space: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Matters’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 30:3, 339–57.

- Zeitlin, Jonathan, Francesco Nicoli, and Brigid Laffan (2019). ‘Introduction: The European Union beyond the Polycrisis? Integration and Politicization in an Age of Shifting Cleavages’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:7, 963–76.