Abstract

The article analyses politicians’ attitudes towards men’s participation in the representation of gender equality interests. Recent studies emphasise the participation of men politicians, since gender equality should be understood as a concern for both women and men in society. Conversely, it is argued that women politicians, who share gender-specific experiences of discrimination with other women, are the primary actors in gender equality representation. This article explores to what extent these viewpoints are shared among politicians in Canada, Portugal, Romania and Switzerland, and analyses the socio-demographic and ideological determinants influencing politicians’ support for an active role of men representatives. Data from the Comparative Candidate Study (2019–2024) show that almost half of the candidates consider gender equality as a field primarily suited to women representatives. Older candidates, as well as those with conservative ideological positions, are more inclined to view women as the primary actors in gender equality representation.

In a plenary debate in the German Bundestag in 1983, Petra Kelly, a Green Party Member of Parliament (MP), raised the question of whether the federal government was planning to criminalise spousal rape. The response she received from Detlef Kleinert, a men MP from the Liberal Party, was a terse and resolute ‘no’, accompanied by laughter and visible amusement among many men MPs in the plenary. It took another 14 years until the government finally outlawed the rape of women by their husbands in 1997.Footnote1

This example illustrates how political advocacy and activism for gender equality has often been understood – as a job that is done by women. In other words, it is the women MPs who – once present in parliament – are responsible for bringing gender equality issues to the political agenda, and for vigorously voicing demands for equal rights and opportunities for women and men. Following Pitkin’s (Citation1967) typology of political representation, and Phillips’ (Citation1995) theory of a politics of presence, previous research on women in parliaments has often proposed a link between the descriptive and substantive representation of women, suggesting that having a higher proportion of women in parliaments leads to a stronger representation of gender-specific concerns.Footnote2 Melissa Williams (Citation1998) even goes further, asserting that the presence of women in parliament is a necessary condition for women’s substantive representation to occur.

However, in recent decades, there have been notable instances of men politicians actively engaging in gender equality politics. For instance, Barack Obama actively supported the United Nation’s ‘HeForShe’ campaign in 2014, Pierre Triponez, a member of the Swiss National Council, was one of the main initiators of a maternity compensation bill which entitled women to 80% of their current income for a period of 14 weeks after giving birth, and Mikael Gustafsson became Chairmen of the European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in 2011. Despite these positive examples, however, the degree to which men politicians play an active role in gender equality politics has been long ignored in the academic debate. Only recently has the discourse surrounding the participation of men MPs in this policy domain begun to grow (e.g. Evans Citation2012; Harder Citation2020; Höhmann Citation2020; Höhmann and Nugent Citation2022; Kroeber Citation2023; Palmieri Citation2013).

This article contributes to the discourse by analysing politicians’ attitudes towards men’s engagement in the representation of gender equality issues, and by examining to what extent politicians perceive gender equality as a policy field that is more suited to women or to men. To this end, the article analyses two central questions. First, the analysis examines descriptively whether politicians understand gender equality as a policy field that affects women and men equally and in which both women and men MPs should be equally responsible for representing these issues in politics, or whether they still associate gender equality predominantly with women-specific interests, and consequently, assign the primary responsibility for its representation to women MPs. Second, beyond mapping politicians’ general understanding of the main actors in gender equality representation, this article analyses the socio-demographic and ideological determinants that make politicians more likely to adopt a progressive position and to accept the need for men to play an active role in gender equality politics. Particularly, the article examines the impact of sex, age, education, and political ideology on politicians’ attitudes towards the main actors in gender equality representation.

By analysing these questions, this study has important implications for the advancement of gender equality in political decision making. If more than half of the MPs in today’s parliaments (i.e. men) are not perceived as being responsible for creating equal rights and opportunities for women and men, this constitutes a major impediment to the achievement of gender equality in the near future.

In general, men’s participation in gender equality politics has constituted a somewhat controversial topic in the theoretical and empirical representation literature. On the one hand, Harder (Citation2020, Citation2023) is optimistic that men MPs can actively engage in this area since she understands gender equality as an interest that is genuinely not ‘attached’ to the identity of women and that equally affects women and men in the society. Consequently, she claims that women MPs should not be the primary actors responsible for its representation in parliament. Men could and should also actively participate in advocating for equal rights and opportunities for all genders. This is also corroborated by empirical studies showing that men MPs are generally willing to represent gender equality issues in parliament (e.g. Celis and Erzeel Citation2015). On the other hand, however, many scholars are sceptical about the possibility that gender equality will be perceived as a policy field that is equally suited to women and men MPs. In light of past discriminations against, and limitations of women’s self-determination by men elites, these authors argue that it is rather unlikely that men MPs are capable of adequately representing gender equality concerns, and that men MPs can therefore not be accepted as the legitimate representatives of these issues (e.g. Dovi Citation2002, Citation2007b; Mansbridge Citation1999). As women MPs share gender-specific experiences of discrimination and exclusion with the female population, it is expected that they are more focused on gender equality issues than their man colleagues, and that they more frequently and more credibly bring topics like the gender pay gap or protection against domestic violence to the legislative agenda (e.g. Coffé and Reiser Citation2018; Dovi Citation2007a; Phillips Citation1995). If politicians follow this ‘gendered logic of appropriateness’ (Chappel and Waylen Citation2013), it is assumed that they still perceive gender equality as a policy field more suited to women, and one in which men MPs should not play an active role. This assumption is also supported in more recent empirical studies showing that men MPs reduce their engagement in women’s substantive representation if more women MPs are present in parliament (Höhmann Citation2020; Kokkonen and Wängnerud Citation2017).

In order to empirically assess to what extent these considerations are shared by actual politicians, this article analyses data from Module III of the Comparative Candidates Survey (CCS Citation2023). To provide cases that allow for a comprehensive and nuanced analysis of politicians’ attitudes towards gender equality representation within different political and cultural contexts, the analysis is based on comparative data from Canada, Portugal, Switzerland, and Romania.

Based on answers from roughly 3000 candidates in these four countries, the findings of the study reveal mixed results. On the one hand, slightly more than half of the surveyed politicians think that men and women MPs are equally responsible for representing gender equality issues in parliament. On the other hand, the analysis also corroborates the existence of scepticism towards men’s participation in gender equality politics, showing that the other half of the interviewed candidates still perceives gender equality as primarily the domain of women MPs. This conservative belief is equally shared among both women and men candidates. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates that particularly older candidates, as well as candidates with conservative ideological positions, are more likely to perceive women MPs as the primary actors in the representation of gender equality issues.

These findings broaden our understanding of the potential actors in gender equality politics and beyond. In terms of whether men MPs should actively engage in the representation of gender equality issues, the results reveal that in modern-day parliaments, there are still deeply-rooted traditional attitudes towards gender equality and what roles men and women should play. The responsibility for promoting gender equality is predominantly seen as the duty of women MPs, while men MPs are largely considered as secondary actors.

While previous studies on the role of men in the representation of gender equality issues have mainly looked at the observable behaviour of men MPs (e.g. Evans Citation2012; Höhmann Citation2020; Höhmann and Nugent Citation2022; Kroeber Citation2023), these studies can only speculate about MPs’ gender role understandings, as well as their underlying motives to engage in women’s and gender equality representation. Analysing the actual attitudes of politicians towards the main actors in the field of gender equality therefore addresses an important research gap, and contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of when and why men MPs decide to (not) become active in the representation of gender equality issues.

These findings not only contribute to the literature on gender representation, but also add to a more general discussion about how a specific group’s identity shapes the role that non-group members can play in its substantive representation. Many aspects of the role of men MPs in gender equality representation also apply to other marginalised and underrepresented groups, including minority ethnic and LGBTQ groups.

Theoretical expectations about men’s role in gender equality politics

Following Alexander et al. (Citation2023), gender equality is generally understood as equal access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender. This implies equal access to political and economic participation, as well as the same opportunities for personal and professional development.

Making progress towards more gender-equal societies requires ‘critical actors’ (Childs and Krook Citation2009) who bring gender equality issues onto the parliamentary agenda, and who initiate policy change that guarantees the equality of different genders. Who do politicians perceive as the critical actors that should be involved in gender equality policies? Do they think that this field is equally suited to men and women, and that consequently, men MPs should play an active role in the representation of gender equality issues? Or is this policy area instead perceived as being more suited to women, with women MPs the primary critical actors responsible for representing gender issues in parliament?

In the following, contrasting arguments about the primary actors, as well as men MPs’ roles in gender equality representation are presented and supported with the – currently – still limited empirical evidence on men MPs’ engagement in gender equality policies. Thereafter, several factors are derived that may have an effect on whether politicians think that men MPs should represent gender equality issues in parliament.

Given that the article is first and foremost interested in politicians’ underlying understanding of women and men MPs’ representational roles and responsibilities, the theoretical arguments are largely embedded in a sociological institutionalist framework. Politicians are generally understood as social actors whose behaviour follows a ‘logic of appropriateness’, which pre- and proscribes certain types of actions and behaviours (March and Olsen Citation1984). Informal norms and institutions thereby reflect a shared understanding of appropriate and acceptable gendered behaviour, as well as well as expectations regarding distinct roles for men and women MPs.

Why politicians perceive gender equality as a policy field that is equally suited to women and men MPs

On a theoretical level, some authors are optimistic that gender equality cab be understood as a policy field that is suited equally to women and men and that men MPs are able to actively engage in advocacy for gender equality concerns.

In her seminal work on the different conceptions of representation, Pitkin (Citation1967) does not assume any strong connections between descriptive and substantive representation, and recommends focusing on the activities of parliaments, rather than their descriptive composition: ‘Think of the legislature as a pictorial representation or a representative sample of the nation, and you will almost certainly concentrate on its composition rather than its activities’ (Pitkin Citation1967: 226). In a chapter of her book, The Concept of Representation, which has so far received only scant attention from representation scholars, Pitkin (Citation1967: 168ff.) elaborates further. She points out that – aside from the common conception that political interests are attached to the identity of specific people or a specific group (women’s interests = interests of women) – representatives can also act in favour of interests that are unattached to their own personal identity (Harder Citation2020; Pitkin Citation1967: 168–189). Pitkin relates this idea to that of Edmund Burke, who argued for the benefits of a ‘virtual representation’ of interests, and famously stated that it is not necessary for the people of Birmingham to send a representative to parliament, because their general interests are already represented by the representative elected in Bristol (Pitkin Citation1967: 168ff.).

Applied to men’s role in gender equality representation, Harder (Citation2020, Citation2023) presents the very compelling argument that a difference should be made between the representation of women’s interests and the representation of gender equality interests. She argues that if we adopt a narrow understanding of women’s substantive representation as solely understood in terms of women’s interests, this implies that the affected interests are inherently and exclusively attached to the identity of women. Consequently, women MPs will be perceived as the primary actors who can legitimately and credibly represent these topics in politics. In contrast, if substantive representation is understood in the sense of gender equality, women MPs would not be, a priori, the actors who are responsible for its representation in parliament. Since the attainment of equal opportunities for all genders explicitly affects both women and men, acting in the interests of gender equality would be more likely to be perceived as something that does not belong to a particular group, but something that both men and women can actively engage in (Harder Citation2020; Palmieri Citation2013). Harder (Citation2023: 6) states that

[W]hen we conceive of an interest as unattached, neither the social attributes of the interest participants nor their membership in social groups form the analytical point of departure; rather, the shared political beliefs or attitudes of these people do.

In a similar vein, Welzel and Inglehart (Citation2014) argue that, compared to shared gender or socio-economic status, empathy for the situation of others has become the more important factor in creating feelings of solidarity between people. Thus, there might be several men MPs motivated to advocate for gender equality, and to work on the reduction of opportunity differences for men and women.

This reflects Childs and Krook’s (Citation2009) notion that it is not enough to look for a critical mass of women in parliament, but that it is necessary to identify the ‘critical actors’ who act in the interests of women and gender equality. And these critical actors, as Childs and Krook explicitly state – can be women or men. In line with the call for a ‘thicker’ (Mackay Citation2008) and more thorough conception of women’s substantive representation, several authors have therefore suggested that we should move beyond analysing only women MPs’ behaviour and the questions of how and when women represent the interests and preferences of their female constituents (Celis and Erzeel Citation2015; Celis et al. Citation2008; Childs and Krook 2008, Citation2009; Mackay Citation2008). If we want to paint a complete picture of the substantive representation of women, Childs and Krook (Citation2008, Citation2009) recommend moving the ‘analytical focus from the macro to the micro level, replacing attempts to discern “what women do” to study “what specific actors do”’ (Childs and Krook Citation2008: 734). Based on Dahlerup’s (Citation1988) observations that sometimes the critical acts of a minority of highly motivated individuals are more beneficial for women-friendly policy change than having large numbers of women in parliament, this idea departs from the notion that women MPs are the exclusively relevant actors, and emphasises that men can also be important in expressing gender equality interests in parliament. Some initial empirical studies support this assumption, showing that men are generally willing to advocate for gender equality issues in parliament (e.g. Celis and Erzeel Citation2015; Dingler et al. Citation2019; Erzeel Citation2015; Höhmann Citation2020; Kokkonen and Wängnerud Citation2017).

In sum, Pitkin’s (Citation1967) and Harder’s (Citation2020, Citation2023) idea of unattached interests, as well as Childs and Krook’s (Citation2009) notion of critical actors both deviate from the assumption that women legislators are the only actors in the representation of gender equality demands, and explicitly argue that men can and should be perceived as committed actors in the field of gender equality policies.

Why do politicians perceive women as better suited to the field of gender equality than men?

Despite the arguments presented above, there are also several reasons why politicians may still believe that gender equality representation is primarily the responsibility of women MPs. Even if the concept of gender equality is not exclusively attached to women, it commonly refers to situations in which women are disadvantaged compared to men; for example, they still earn less, they are more likely to be the victim of domestic violence, and are underrepresented in many political institutions. It follows, that advocating for gender equality in most cases implies that the situation of women should be improved and that the historically-grounded privileges of men should be abolished. In light of this proposition, several points may make politicians more likely to still perceive women MPs as the most important actors in this policy area.

Based on her theory of a politics of presence, Phillips (Citation1994: 71f.) argues that

[w]omen occupy a distinct position within society: they are typically concentrated, for example, in lower paid jobs; and they carry the primary responsibility for the unpaid work of caring for others. There are particular needs, interests, and concerns that arise from women’s experience, and these will be inadequately addressed in a politics that is dominated by men.

Phillips assumes that the divergent life experiences of women and men result in distinct policy priorities and preferences. Since women MPs share these experiences with women in the society, it is expected that they develop a sense of solidarity and linked fate with women in the general population. This group identification and the shared gendered life experiences not only provide women MPs with the necessary knowledge to credibly represent women’s perspectives, but also positively impact on the motivation of women MPs to make gender equality issues heard in the legislative arena (Sobolewska et al. Citation2018).

Thus, women legislators are expected to engage actively with the social perspective of women, and to represent gender equality issues more frequently in parliament compared with their men colleagues. Since men MPs are often unaware of the priorities and interests of women, or to what extent certain policies affect women and men differently, gender equality issues would often be ‘overlooked’ if women were not present in parliament (c.f. Mansbridge Citation1999; Young Citation2000).

This point of view is also reflected by the assumptions of the more recently developed Feminist Institutionalism (Krook and Mackay Citation2011) and the associated ‘gendered logic of appropriateness’ (Chappel and Waylen Citation2013). These two approaches highlight that the ‘rules of the political game’ can affect men and women differently, and consequently, expect that informal rules about appropriate and acceptable gendered behaviour produce distinct roles for men and women MPs. In contrast to men MPs and due to being personally affected by gender disadvantage, one of these ‘appropriate’ roles for women legislators is to be active in gender equality representation (Bergqvist et al. Citation2018). It follows that if there are enough women in parliament, men MPs feel that they do not have the responsibility to be responsive to gender equality issues because women MPs can represent these issues more credibly.

The presence of these gendered logics of appropriateness is also confirmed in several empirical analyses. Höhmann (Citation2020) analysed the content of parliamentary questions in the German Bundestag to analyse the effect of women on men MPs’ attitudes towards the representation of women and gender equality issues. He found that the proportion of women in the parliamentary party group has a significant negative effect on men MPs’ behaviour and their decision to actively represent gender equality issues in parliament: Men MPs in the Bundestag significantly reduce the intensity with which they speak on behalf of women if the proportion of women MPs is high (Höhmann Citation2020; c.f. Kokkonen and Wängnerud Citation2017). In a related study of British MPs’ voting behaviour and debate contributions, Evans (Citation2012) showed that some men MPs represented gender equality concerns in their debate contributions. However, they were in the minority and spoke less if women’s perspectives had already been expressed by many women MPs in these debates. A more recent study by Kroeber (Citation2023) also highlights that men MPs who speak about gender equality issues in plenary debates tend to focus on the aspects of these issues that have a male connotation (e.g. funding for gender equality projects).

Lastly, Höhmann and Nugent (Citation2022) find that men MPs in the British House of Commons are more likely to become active in gender equality representation if their re-election is at risk. The authors conclude that one of the key drivers of men’s engagement in women’s representation is a rational calculation of how they can enhance their Election Day prospects, rather than an intrinsic motivation to stand up for women’s rights and gender equality.

From a more structural perspective – and again assuming that the achievement of gender equality mostly implies that women’s disadvantages are eliminated – some arguments underline the notion that politicians may still perceive that men MPs as being unable to play an active role in the representation of gender equality issues.

First, women’s participation in public life has been suppressed for centuries, and access to political positions of power has been consistently denied them only on the basis of their gender. Mansbridge (Citation1999) argues that this structural discrimination against women creates a context of mistrust between women and men, and prevents adequate communication between members of the two groups. She notes that this ‘history of dominance and subordination typically breeds inattention, even arrogance, on the part of the dominant group’ (Mansbridge Citation1999: 641), and that therefore men – as the main actors in women’s discrimination – cannot legitimately stand for the interests and equal opportunities of those persons that they have systematically excluded. Moreover, Dovi (Citation2002) forcefully argues that representatives and members of historically disadvantaged groups must mutually recognise each other. This entails that representatives and the represented accept each other as belonging to the same disadvantaged group, and that the representative who speaks on behalf of a particular group is recognised by the members of this group as ‘being one of us’ (Dovi Citation2002: 736). In light of the past discriminations against, and limitations of female citizens’ self-determination by male elites, however, it is rather unlikely that men MPs will be perceived as being able to adequately advocate for gender equality.

Second, Dovi (Citation2002) argues that a person’s motivation to act on behalf of a specific topic is higher if they believe that their personal interests are affected, and if their self-interests are connected to the interests of the whole group. This notion of a linked fate also entails that individuals believe that what happens to their social group as a whole also has direct consequences for their own personal lives. Regarding men MPs’ role in gender equality politics, it thus follows that it is implausible to perceive men as critical actors because they do not share any linked fate with women in society. Quite the contrary, men MPs engaging in gender equality would actively work against their own advantages and their dominant position compared to women. For example, it is not possible to achieve equal pay for women and men without lessening the financial privileges of men compared to women, or to increase the number of women in powerful political positions without men losing part of their dominant status in the legislature or executive (Phillips Citation1995: 69).

Overall, the theoretical arguments and the empirical findings to date show a marked preponderance in favour of the assumptions that politicians may still perceive gender equality as a policy field that is primarily suited to women MPs. While the presented counter-argument of ‘unattached’ gender equality interests is fascinating and plausible, informal and formal rules are sticky (Thelen Citation1999), meaning that perceptions about appropriate gender roles, as well as the notion of women MPs as the only actors responsible for the representation of gender equality are hard to change in the short-run. As Pitkin (Citation1967) and Phillips (Citation1995) have both observed, representation is a long process. ‘Fair representation is not something that can be achieved in one moment, nor is it something that can be guaranteed in advance. Representation depends on the continuing relationship between representatives and the represented […]’ (Phillips Citation1995: 82). Altogether, the presented theoretical and empirical evidence therefore leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Gender equality is generally perceived as a policy field that is more suited to women politicians than to men politicians.

Factors influencing whether politicians perceive the field of gender equality as suited to men MPs

In order to gain a more detailed understanding of which politicians are more likely to consider men as being able to engage in the representation of gender equality issues, the following section presents two sets of determinants that may affect politicians’ perceptions regarding the primary actors in gender equality representation: (1) socio-demographic characteristics and (2) ideology and gender equality attitudes.

The group of socio-demographic factors includes politicians’ biological sex, age, and education.

One important question to look at is whether, and to what extent, women and men politicians differ in their opinions on whether the policy field of gender equality is equally suited to women and men MPs. Theoretically, however, it can be assumed that the biological sex of the politicians should probably not have a significant effect, meaning that both women and men politicians consider it more appropriate for women to engage in the representation of gender equality issues. As pointed out above, men politicians mostly adhere to a ‘gendered logic of appropriateness’ and its associated informal rules about acceptable gendered behaviour (Chappel and Waylen Citation2013). Consequently, men politicians perceive no genuine responsibility to actively represent gender equality issues in parliament because it is assumed that women MPs can represent these issues more credibly.

As a result of sharing gender-specific experiences with women in society at large, and having a greater personal stake in promoting equality, women politicians are expected to perceive men MPs as lacking the necessary understanding needed to effectively represent gender equality perspectives in parliament. Consequently, they will believe that women MPs can cover the ‘gender angle’ (Evans Citation2012) more competently, and that the representation of gender equality is thus mainly a policy field in which women should be engaged. This is additionally supported by several empirical studies showing that women legislators have different priorities than men MPs and that they see themselves as representatives of the women electorate (Coffé and Reiser Citation2018; Reher Citation2018; Schwindt-Bayer Citation2010; Xydias Citation2014).

Hypothesis 2: Both women and men politicians perceive gender equality as a policy field that is more suited to women politicians than to men politicians.

Regarding the effect of age, it is expected that younger politicians may be more likely to perceive gender equality as a policy field that is equally suited to women and men. Whereas older politicians tend to have more conservative attitudes towards gender equality, younger generations are generally more exposed to the perspectives and experiences of individuals from marginalised groups, and may also be more aware of the ways in which traditional gender roles can perpetuate discrimination and marginalisation against women (Kokkonen and Wängnerud Citation2017). Thus, older politicians are more likely to adhere to traditional understandings of gender roles and consider gender equality as a field that is primarily suited to women MPs.

Hypothesis 3: Older politicians are more likely to perceive gender equality as a policy field that is more suited to women politicians than to men politicians.

Similar effects can be expected for highly-educated politicians. Education exposes individuals to different perspectives and ways of thinking, which can help to challenge traditional gender norms and stereotypes (Edlund and Öun Citation2016). It follows that education should be positively correlated with politicians’ beliefs that men MPs are able to represent gender equality issues in parliament.

Hypothesis 4: Highly educated politicians are less likely to perceive gender equality as a policy field that is more suited to women politicians than to men politicians.

Regarding the second set of determinants, the analysis examines the influence of politicians’ left-right ideological position and the associated attitudes towards gender equality.

Political ideology is probably one of the most important factors in explaining politicians’ attitudes towards gender equality, as well as their engagement in the parliamentary representation of these issues (e.g. Alexander et al. Citation2023; Childs and Krook Citation2009; Espírito-Santo et al. Citation2020; Xydias Citation2013). It is therefore expected that politicians’ ideological positions on a general left-right dimension also affects their attitudes regarding the primary actors in the representation of gender equality issues.

While right-wing ideological positions are characterised by conservative values, traditional gender roles, and a preference for adhering to existing rules and norms, left-wing ideological positions generally imply progressive attitudes, modern gender roles, and support for equality between economic, racial, or gender groups. Regarding the substantive representation of women, several studies corroborate that politicians from left-wing parties attach a higher importance to the achievement of gender equality and that they are more strongly committed to expressing the needs of marginalised groups in parliament (e.g. Erzeel and Celis Citation2016; Kittilson Citation2011). Consequently, it is expected that politicians with a more left-wing ideological position and positive attitudes towards the equality of the sexes will perceive women and men MPs as equally responsible for the representation of gender equality issues. In contrast, conservative politicians with more traditional gender role models are more likely to believe that gender equality is a topic that – if at all – mainly women should be engaged in.

Hypothesis 5: Politicians with left-wing ideological positions are less likely to perceive gender equality as a policy field that is more suited to women politicians than to men politicians.

Methods and data

The empirical analysis investigates politicians’ attitudes towards gender equality representation in Canada, Portugal, Switzerland, and Romania.

Studying politicians’ attitudes towards gender equality representation in these four countries provides a diverse range of cases that allow for a comprehensive and nuanced analysis covering different political landscapes and cultural contexts. Notably, the four countries vary substantially according to their levels of gender equality in society, as well as women’s status in politics. Whereas Portugal and Switzerland belong to the top-ten countries in Europe regarding women’s representation in parliament (38% and 42% respectively after the national elections in 2019), the presence of women in the Canadian (30%) and Romanian (19%) lower house is rather low. Portugal applies a legislated candidate quota system that requires all candidate lists to include a minimum of 33% women, whereas the three other countries only introduced voluntary party quotas (Interparliamentary Union Citation2023). Moreover, the four countries provide a meaningful geographical variation (Western Europe, Eastern Europa, Southern Europe, North America), as well as ample differences regarding their political and institutional systems.

The analysis uses data from Module III of the Comparative Candidate Survey (CCS).Footnote3 The CCS is a collaborative, international initiative aimed at gathering information on candidates participating in national parliamentary elections across various countries. The study surveys all candidates, irrespective of their individual election outcome, and includes information on candidates’ biographical information, their campaign strategies and policy stances, as well as their views on political representation. The data collection is carried out through self-administered questionnaires, either online or on paper. The Canadian survey was fielded after the national election in 2021. Data for Swiss and Portuguese candidates were collected after the respective elections in 2019. The Romanian part of the study was conducted after the election in 2020 (CCS Citation2023).

Data from the Canadian part of the study are only used for the descriptive analysis of politicians’ attitudes towards men’s responsibility for gender equality representation. Since, to preserve anonymity, the Canadian Candidate study did not ask for respondents’ age, the data cannot be included in the multivariate regression models.

Dependent variable. The dependent variable of the analysis measures the extent to which candidates perceive gender equality as a policy field that men and women MPs can equally engage in. To operationalise this variable, Module III of the CCS asked respondents to rate on a seven-point scale the extent to which the field of gender equality policies is more appropriate for a man or a woman in politics.Footnote4 A value of four means that the area of gender equality is equally suited to women and men. Lower values indicate that candidates perceive gender equality policies as better suited to men politicians. Higher values show that candidates consider gender equality issues to be more appropriate for women politicians.Footnote5 Since the question asks candidates directly about their attitudes regarding gender equality representation – and not women’s interests or women’s substantive representation – it is particularly well suited to test the hypotheses of this article and to analyse whether politicians perceive gender equality as an issue that affects all genders, and one that men and women MPs can equally participate in.

Independent variables. To explore which candidates are more likely to be open towards men politicians’ engagement in gender equality policies, the independent variables are measured as follows: to indicate candidates’ sex, respondents were asked to indicate whether they identify as a woman or as a man (further options were not included). Men candidates are coded as 1, women receive a score of 0. Candidates’ age is measured in years. To identify the effect of education, a dummy variable is included in the analysis which is coded 1 for candidates with a university degree (including higher vocational colleges and universities of applied sciences) and 0 otherwise.

Candidates’ political ideology is measured by asking the respondents to place themselves on a general left-right scale ranging from 0 (left) to 10 (right). To disentangle the general effect of political ideology and the more specific influence of candidates’ gender equality attitudes, the analysis additionally includes a variable indicating how supportive candidates are of equal rights for women and men. During the survey, respondents were presented with four statements on gender equality issues and were asked to indicate on a scale from 1 (no support) to 4 (full support) to what extent they agreed with the statement. The statements asked whether women should be given preferential treatment when applying for jobs, whether women should be free to decide on matters of abortion, and whether same-sex marriages should be prohibited by law. The variable for gender equality attitudes is then operationalised as an index that includes the average of the candidates’ answers to the three statements.

Empirical analysis. To assess candidates’ attitudes towards men’s role in gender equality representation, the first part of the analysis presents descriptive evidence to illustrate whether and to what degree men and women candidates consider men MPs to be suited to engage in gender equality representation.

The estimation of the determinants affecting candidates’ views on gender equality representation is based on a linear regression analysis.Footnote6 All models control for whether candidates have children under the age of 18, as well as for candidates’ general understanding of political representation.

Regarding the effect of having children, several studies demonstrate a positive relationship between parenthood and having more traditional attitudes towards gender and family roles (Fan and Marini Citation2000; Kaufman et al. Citation2017). Other studies, however, indicate that men politicians in particular are more likely to express an interest in social policy if they have been on parental leave during their time in office (Stensöta Citation2020), and that they become more likely to vote liberally on reproductive rights as their number of daughters increased (Washington Citation2008). The effect of parenthood is operationalised with a dummy variable indicating whether respondents have children under the age of 18. Due to the mentioned inconclusive results, parenthood is not considered as an explanatory factor in this study, but is used as a control variable in the analysis.

To avoid any biases due to variations in candidates’ general understanding of how political representation should work, the analysis controls for whether politicians think that legislators should ideally represent the interests of all citizens in a country instead of only working for the preferences of a specific social group. Candidates’ general understanding of political representation is measured as a ranking of how important they think it is that MPs represent the interests of all citizens in the country (1 – very important; 5 – not important).

To avoid systematic biases due to structural or cultural differences between the included countries, all models additionally contain country fixed-effects.Footnote7 After excluding candidates with missing information on one of the relevant variables, the descriptive part of the analysis is based on 3067 observations (including data from Canada), and the multivariate analysis includes 2298 observations (excluding data from Canada, see above).Footnote8

Results: politicians’ attitudes towards men’s role in gender equality politics

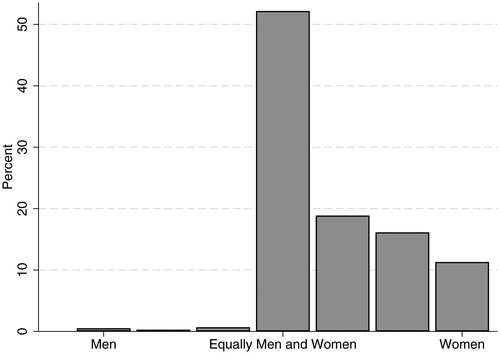

The descriptive findings on politicians’ attitudes towards the actors considered as responsible for gender equality representation are mixed. If gender equality was truly perceived as a policy field that is ‘unattached’ from women’s interests, and therefore one that men and women MPs should equally engage in, politicians’ answers to the question whether gender equality representation is a better fit for a man or a woman in politics should follow a normal distribution centred around the category stating that it is equally suited to women and men MPs. However, the results in show a heavily skewed distribution of politicians’ attitudes.

Figure 1. The perception of gender equality as a policy field that is suited to women or men politicians. Notes: 2019–2024 Comparative Candidate Survey. Respondents were asked to rate on a seven-point scale the extent to which the field of gender equality policies is a better fit for a man or a woman in politics. N = 3067.

On the one hand, slightly more than half of the surveyed candidates (52%) indicate that men and women MPs are equally responsible for addressing gender equality issues in their political work. This provides evidence for Harder’s (Citation2023) idea that many candidates actually understand gender equality as an interest that affects both men and women, and that consequently, women MPs are not the a priori actors who are responsible for its representation in parliament. These findings support the progressive argument that – in contrast to the representation of women’s interests – acting in the interests of gender equality is perceived as something that does not belong to women as a particular group, but something that both men and women MPs should actively engage in. On the other hand, the distribution in also demonstrates that slightly less than half of the surveyed candidates still consider gender equality as a policy field that is more suitable for women than for men politicians. In total, 46% of the respondents indicated that the representation of gender equality issues is more appropriate for women MPs. 11% of the candidates even indicted that this policy area is only suited to women and that men MPs cannot address these issues in their political work. Remarkably, less than 2% of the candidates believe that working for gender equality is better suited to men than for women MPs.

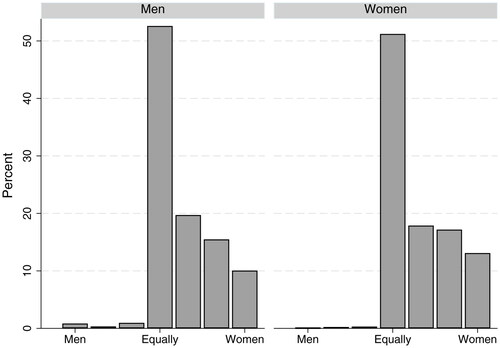

portrays the results when the data is analysed separately for women and men candidates and reveals almost identical distributions for both groups. Specifically, 48% of women candidates and 45% of men candidates concur that gender equality is primarily a policy field where women politicians should take an active role.Footnote9

Figure 2. The perception of gender equality as a policy field that is suited to women or men politicians, by sex. Notes: 2019–2024 Comparative Candidate Survey. Respondents were asked to rate on a seven-point scale the extent to which the field of gender equality policies is a better fit for a man or a woman in politics. N = 3067.

This heavily skewed distribution suggests that traditional beliefs about gender roles, as well as perceptions about a ‘gendered logic of appropriateness’ remain deeply ingrained in the attitudes and mind-sets of many politicians. This may be attributed to a perceived shared fate between women politicians and women in society, as well as their common gendered experiences. Consequently, many candidates for national parliaments still predominantly view gender equality as falling within the realm of women MPs’ political responsibilities.Footnote10

This gendered understanding of representational roles is further supported when examining areas traditionally associated with men: during the survey, candidates were also asked to assess whether defence and security policies, typically considered as ‘masculine’ and ‘hard’ policy areas, were more suitable for men or women politicians. Almost mirroring the previous results, Figure A3 in the Online Appendix demonstrates that roughly 45% of candidates believe that defence and security politics are primarily the domain of men politicians, while less than 2% of the respondents perceive them as particularly suited to women MPs. Additionally, Figure A4 in the Online Appendix demonstrates that this gendered perception is even more pronounced among men candidates.

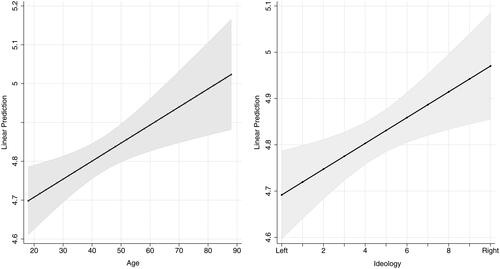

Figure 3. The effect of age and ideology on candidates’ attitudes towards women’s and men’s roles in the representation of gender equality policies. Linear predictions. Notes: Linear predictions of respondents rating on a seven-point scale of the extent to which the field of gender equality policies is a better fit for a man or a woman in politics. Higher values indicate that the policy field is more appropriate for women. A value of four shows that the policy field is perceived to be equally suited to women and men. The predictions are based on Model 1 in . Age: mean = 43.1; std. dev.=15.2. Ideology: mean = 4.4; std. dev.=2.7.

Let us now turn to the multivariate analysis of the potential determinants affecting candidates’ attitudes towards gender equality representation. The analysis is based on data from Switzerland, Portugal and Romania, and the results are presented in .Footnote11 Model 1 contains the model specification discussed above. Overall, the findings reveal that both age and political ideology significantly influence candidates’ views on whether women or men should be primarily engaged in representing gender equality issues. The effects of all other variables are statistically not distinguishable from zero.Footnote12 Notably, the null effect for candidates’ sex confirms the descriptive findings presented above that perceptions regarding the key actors in gender equality representation do not significantly diverge between men and women politicians.

Table 1. Determinants of politicians’ attitudes towards women’s and men’s roles in the representation of gender equality policies.

For the interpretation of the substantive effect strength of the two significant variables, shows linear predictions based on the results from Model 1.

Concerning age, the left panel of demonstrates that older candidates hold more traditional views on representational roles. They are more inclined to perceive gender equality as primarily suited to women MPs. Conversely, younger candidates exhibit a greater openness to men’s active participation in gender equality representation, and see this policy area as equally suitable for both men and women politicians. These results validate the theoretical expectations regarding the influence of candidates’ age.

Similarly, the theoretical expectations regarding the influence of political ideology are affirmed. As depicted in the right panel of , candidates leaning towards the left end of the political spectrum tend to hold more progressive views on political representation, and are more likely to believe that both men and women politicians should actively work towards equal rights for both genders. Candidates with more conservative and right-wing ideological positions more frequently express the belief that engagement in gender equality policies is better suited to women politicians.

In order to analyse whether the two significant variables have different effects for men and women candidates, Model 2 and Model 3 include additional interaction effects of candidates’ sex and age, and candidates’ sex and ideology, respectively. The significant interaction effect in Model 2 indicates that the positive effect of age is stronger for women candidates. This shows that particularly older women respondents tend to have more conservative attitudes towards the actors in gender equality representation, attributing the main responsibility in this policy field to female MPs. This attitude may result from the personal experiences of gendered discrimination that these older women might have endured over the course of their longer careers. Because of this potential past discrimination committed by men elites, older women respondents may therefore be less likely to perceive men MPs as being able to adequately and legitimately represent gender equality interests in parliament.

The interaction effect in Model 3 is statistically insignificant, indicating that the effect of political ideology is not conditional on whether the respondent is a women or a man. This is further corroborated by an analysis that only includes men candidates. While the effect of age is insignificant for men respondents, the observed effect for ideology is nearly identical to the model including both men and women candidates. The results can be found in Table A1 in the Online Appendix.

Additional robustness tests confirm that all results remain unchanged when an ordered logistic regression (Table A2 in the Online Appendix) or a multilevel regression (Table A3 in the Online Appendix) are employed instead of a linear regression analysis. Moreover, the main findings remain unaffected if observations in the regression analysis are weighted by their political party (Table A4 in the Online Appendix). To explore whether candidates’ attitudes towards men’s role in gender equality representation are driven by rational-choice incentives (see Höhmann and Nugent Citation2022), Table A5 in the Online Appendix includes additional models that control for whether a candidate was elected in the following election (Model 1 in Table A5 in the Online Appendix), as well as for candidates’ subjective electoral security (Model 2 in Table A5 in the Online Appendix). The first variable is measured as a dummy variable. To measure subjective electoral security, candidates were asked to evaluate their chances of winning a mandate at the beginning of the campaign (0 – I thought I could not win; 4 – I thought I could not lose). The results show that elected and top candidates do not differ from non-elected and less-promising candidates in their perception of the primary actors in gender equality representation. All other effects of the main analysis remain unchanged. Additionally, Model 4 in Table A5 in the Online Appendix shows that the results are robust to an alternative operationalisation of candidates’ age. Instead of including age as a continuous variable, this specification includes different age categories (younger than 35; 35–50; 51–65; older than 65). In comparison to young candidates, all other categories have a significant and positive effect on candidates’ perception that gender equality is primarily suited to women MPs. As expected, the strongest effect can be observed for candidates in the oldest category (older than 65). Lastly, the models in Table A6 in the Online Appendix demonstrate that the effects for age and ideology are also robust to an alternative operationalisation of the dependent variable, where the original seven-point dependent variable is recoded into a variable with only three categories (1 – gender equality is more suited to men, 2 – gender equality is equally suited to women and men, 3 – gender equality is more suited to women).Footnote13

Discussion and conclusion

While previous research predominantly assumes that the representation of gender equality issues is primarily a duty of women MPs, there is an emerging discussion in the literature about the role that men MPs play in gender equality politics (e.g. Harder Citation2020, Citation2023; Höhmann Citation2020; Höhmann and Nugent Citation2022; Palmieri Citation2013).

This article contributes to this debate by analysing politicians’ attitudes and preferences regarding the primary actors in the parliamentary representation of gender equality. In line with much of the theoretical literature on women’s representation, the results present a mixed outlook regarding the active involvement of men MPs in the pursuit of gender equality. Using data from the 2019–2024 Comparative Candidate Survey, the analysis shows that slightly over half of the candidates for national elections in Canada, Switzerland, Portugal, and Romania indicate that men MPs should play an active role, and that the field of gender equality is equally appropriate for men and women MPs. However, the other half of the candidates still perceives gender equality as a policy field that is primarily suited to women MPs. Notably, this belief is held equally among women and men candidates. Moreover, the results indicate that conservative, as well as older candidates are particularly inclined to believe that the field of gender equality is more appropriate for women MPs.

Given that almost none of the candidates believe that – in comparison to women MPs – men MPs have a greater responsibility to advocate for gender equality issues, the results demonstrate that traditional gender roles and perceptions rooted in a gendered logic of appropriateness appear to be deeply ingrained in contemporary parliaments. Even within the context of modern and progressive parliaments, the parliamentary representation of gender equality is still seen as a primary duty of women MPs. Men MPs are often considered only as a secondary, or ancillary actor in this respect. These findings carry important implications for the representation of women in politics, and the promotion of gender equality in political decision making. They highlight how the primary duty for advancing gender equality, including advocating for issues like equal pay, protection against domestic violence, or equal access to public office, continues to rest with women politicians, while men MPs appear to be exempt from this duty. While these findings are embedded in a sociological institutionalism framework, they also form the foundation for a rational-choice perspective on the specific situations in which men politicians decide to engage in the representation of gender equality issues. For instance, Höhmann and Nugent (Citation2022) show that men MPs in the British House of Commons act as rational, vote-seeking actors who only become more likely to speak about gender equality if their electoral security is low and they are forced to fight for additional votes to be re-elected. Thus, purely rational men politicians can exploit a ‘gendered leeway’ (Bergqvist et al. Citation2018) in which – in contrast to women politicians – advocating for gender equality gives them additional merit (and votes) because this behaviour is generally not perceived as a duty that men politicians have to fulfil.

However, without the constant participation and active engagement of men MPs – who still make up the vast majority in almost all parliaments and executive bodies worldwide – significant progress towards gender equality seems unlikely. Phillips (Citation1995: 69) seems to be right when she claims that women MPs ‘can expect to find a few powerful allies among the men. What they cannot really expect is the degree of vigorous advocacy that people bring to their own concerns.’

Apart from the attitudes and preferences of politicians, the effective engagement of men politicians in the representation of gender equality heavily depends on how this behaviour is perceived among women in society. The ‘constructivist turn’ (e.g. Saward Citation2010; Severs Citation2012; Squires Citation2008) within scholarship on representation offers a promising perspective in this regard. Scholars in this tradition perceive representation as a ‘claims-making’ process in which the representative claims to speak for the represented and thereby constitutes the substantive interests of that group (Saward Citation2010).

One pivotal aspect regarding men’s participation in gender equality, therefore, concerns whether men MPs can legitimately claim to represent women and gender equality interests without sharing a linked fate or gendered experiences with women generally. To assess whether or not an MP is a legitimate representative of a specific group, Rehfeld (Citation2017: 63) suggests one crucial criterion:

[I]n order to actually serve as a representative, […] an individual must be recognized by the appropriate people – those whose recognition will impart to the individual the power to be a “stand-in-for” another group, “in-order-to-do” some particular action.

Examining the preferences of both the representatives and the represented regarding gender equality representation will shed light on whether perceptions about appropriate gender roles can be changed in the long-run, and whether the notion of women MPs as the only actors responsible for the representation of gender equality issues can be modified.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (972.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2023 Annual Conference of the Swiss Political Science Association, the 2023 ECPR General Conference, the 2023 Conference of the ECPR Standing Group of Parliaments, and the 2023 Conference of the DVPW Themengruppe Vergleichende Parlamentarismusforschung. I am grateful for comments and suggestions by all audiences, in particular by Joachim Blatter, Jana Boukemia, Elena Frech, Corinna Kroeber, Marko Kukec, Wang Leung Ting, T. Murat Yildirim, and Thomas Zittel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Höhmann

Daniel Höhmann is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Political Science at the University of Basel, Switzerland. His research focuses on representation, legislative studies, and women and politics. His work has been published, among others, in the Journal of Politics, European Journal of Political Research, West European Politics, Political Research Quarterly, European Political Science Review, Public Choice, Swiss Political Science Review, and the Journal of Legislative Studies.

Notes

1 A video with a summary of the debate is published on the official X (formerly Twitter) account of the Tagesschau. It is available here: https://twitter.com/tagesschau/status/864177990229528576?lang=de.

2 This article focuses on the representation of gender equality as one essential aspect of women’s substantive representation. However, research has also emphasized that some women are sometimes accurately represented by conservative or even anti-feminist positions (Celis and Childs Citation2012).

3 The CCS is organized into modules, each lasting approximately six years. At the time of writing, Module III, spanning from 2019 to 2024, is currently in progress. The first release of Module III encompasses information from candidates in five different countries (Canada, Ireland Portugal, Switzerland, and Romania). Data from Ireland could not be used for the present analysis, because the Irish survey did not include a question on candidates’ attitudes towards gender equality representation. Further information, including ethical considerations of the survey, can be found on the project’s homepage: http://www.comparativecandidates.org.

4 The exact wording in the English questionnaire is: ‘According to your opinion, which of the following policy fields fit better to a male or a female politician? – Gender equality policies’ (Variable C4e).

5 Since this question is not included in earlier rounds of the Candidate Study, a panel study which would allow changes over time to be analyzed, is not feasible.

6 All results remain unchanged if the estimation is based on an ordered logistic regression analysis (see Table A2 in the Online Appendix).

7 All results remain unchanged if a multilevel regression model is used (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix). Due to the very low numbers of units on the upper level (countries), a regression model with country fixed-effects is preferred.

8 Canada: 272 respondents; Switzerland: 2119 respondents; Portugal: 367 respondents; Romania: 309 respondents.

9 The 2019 Swiss Election Study included identical items on gender equality representation in its voter survey prior to the Swiss national election in 2019. Figures A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix show that the attitudes towards men’s roles in gender equality politics among the population are very similar to those of the surveyed politicians.

10 Figures A5–A12 in the Online Appendix show that, somewhat surprisingly, the gendered understanding of the main actors in gender equality representation are particularly pronounced in Canada and Switzerland, where more than half of the respondents perceive gender equality as a policy field that is more appropriate for women MPs then for men MPs.

11 To preserve anonymity, the Canadian Candidate study did not ask for respondents’ age. Therefore, the data cannot be included in the multivariate regression analysis.

12 A robustness test in Table A7 in the Online Appendix shows that the main results also hold if data from Canada are included and age is removed from the model.

13 Estimations in Table A6 in the Online Appendix are based on ordered logistic regression models.

References

- Alexander, Amy, Asbel Bohigues, and Jennifer M. Piscopo (2023). ‘Opening the Attitudinal Black Box: Three Dimensions of Latin American Elites’ Attitudes about Gender Equality’, Political Research Quarterly, 76:3, 1265–80.

- Bergqvist, Christina, Elin Bjarnegård, and Per Zetterberg (2018). ‘The Gendered Leeway: Male Privilege, Internal and External Mandates, and Gender-Equality Policy Change’, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6:4, 576–92.

- CCS (2023). Comparative Candidates Survey (CCS) Module III - Cumulative Dataset 2019 - 2024 (1.0.0) [Dataset]. FORS Data Service. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.48573/j9rw-fv36

- Celis, Karen, and Sarah Childs (2012). ‘The Substantive Representation of Women: What to Do with Conservative Claims?’, Political Studies, 60:1, 213–25.

- Celis, Karen, Sarah Childs, Johanna Kantola, and Mona L. Krook (2008). ‘Rethinking Women’s Substantive Representation’, Representation, 44:2, 99–110.

- Celis, Karen, and Silvia Erzeel (2015). ‘Beyond the Usual Suspects: Non-Left, Male and Non-Feminist MPs and the Substantive Representation of Women’, Government and Opposition, 50:1, 45–64.

- Chappel, Louise, and Georgina Waylen (2013). ‘Gender and the Hidden Life of Institutions’, Public Administration, 91:3, 599–615.

- Childs, Sarah, and Mona L. Krook (2008). ‘Critical Mass Theory and Women’s Political Representation’, Political Studies, 56:3, 725–36.

- Childs, Sarah, and Mona L. Krook (2009). ‘Analysing Women’s Substantive Representation: From Critical Mass to Critical Actors’, Government and Opposition, 44:2, 125–45.

- Coffé, Hilde, and Marion Reiser (2018). ‘Political Candidates’ Attitudes towards Group Representation’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24:3, 272–97.

- Dahlerup, Drude (1988). ‘From a Small to a Large Minority: Women in Scandinavian Politics’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 11:4, 275–98.

- Dingler, Sarah C., Corinna Kroeber, and Jessica Fortin-Rittberger (2019). ‘Do Parliaments Underrepresent Women’s Policy Preferences? Exploring Gender Equality in Policy Congruence in 21 European Democracies’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26:2, 302–21.

- Dovi, Suzanne (2002). ‘Preferable Descriptive Representatives: Will Just Any Woman, Black, or Latino Do?’, American Political Science Review, 96:4, 729–43.

- Dovi, Suzanne (2007a). The Good Representative. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Dovi, Suzanne (2007b). ‘Theorizing Women’s Representation in the United States’, Politics & Gender, 3:3, 297–319.

- Edlund, Jonas, and Ida Öun (2016). ‘Who Should Work and Who Should Care? Attitudes towards the Desirable Division of Labour between Mothers and Fathers in Five European Countries’, Acta Sociologica, 59:2, 151–69.

- English, Ashley, Kathryn Pearson, and Dara Z. Strolovitch (2019). ‘Who Represents Me? Race, Gender, Partisan Congruence, and Representational Alternatives in a Polarized America’, Political Research Quarterly, 72:4, 785–804.

- Erzeel, Silvia (2015). ‘Explaining legislators’ actions on Behalf of Women in the Parliamentary Party Group: The Role of Attitudes, Resources, and Opportunities’, Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 36:4, 440–63.

- Erzeel, Silvia, and Karen Celis (2016). ‘Political Parties, Ideology and the Substantive Representation of Women’, Party Politics, 22:5, 576–86.

- Espírito-Santo, Ana., André Freire, and Sofia Serra-Silva (2020). ‘Does Women’s Descriptive Representation Matter for Policy Preferences? The Role of Political Parties’, Party Politics, 26:2, 227–37.

- Evans, Elizabeth (2012). ‘From Finance to Equality: The Substantive Representation of Women’s Interests by Men and Women MPs in the House of Commons’, Representation, 48:2, 183–96.

- Fan, Pi-Ling, and Margaret M. Marini (2000). ‘Influences on Gender-Role Attitudes during the Transition to Adulthood’, Social Science Research, 29:2, 258–83.

- Harder, Mette M. S. (2020). ‘Pitkin’s Second Way: Freeing Representation Theory from Identity’, Representation, 56:1, 1–12.

- Harder, Mette M. S. (2023). ‘Parting with ‘Interests of Women’: How Feminist Scholarship on Substantive Representation Could Replace ‘Women’s Interests’ with ‘Gender Equality Interests’, European Journal of Politics and Gender, 6:3, 377–94.

- Höhmann, Daniel (2020). ‘When Do Men Represent Women’s Interests in Parliament? How the Presence of Women in Parliament Affects the Behavior of Male Politicians’, Swiss Political Science Review, 26:1, 31–50.

- Höhmann, Daniel, and Mary Nugent (2022). ‘Male MPs, Electoral Vulnerability, and the Substantive Representation of Women’s Interests’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:3, 762–82.

- Interparliamentary Union (2023). Parline Database [Dataset]. Retrieved from https://data.ipu.org/content/parline-global-data-national-parliaments

- Kaufman, Gayle, Eva Bernhardt, and Frances Goldscheider (2017). ‘Enduring Egalitarianism? Family Transitions and Attitudes toward Gender Equality in Sweden’, Journal of Family Issues, 38:13, 1878–98.

- Kittilson, Miki C. (2011). ‘Women, Parties and Platforms in Post-Industrial Democracies’, Party Politics, 17:1, 66–92.

- Kokkonen, Andrej, and Lena Wängnerud (2017). ‘Women’s Presence in Politics and Male Politicians Commitment to Gender Equality in Politics: Evidence from 290 Swedish Local Councils’, Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 38:2, 199–220.

- Kroeber, Corinna (2023). ‘When Do Men MPs Claim to Represent Women in Plenary Debates—Time-Series Cross-Sectional Evidence from the German States’, Political Research Quarterly, 76:2, 1024–37.

- Krook, Mona L., and Fiona Mackay, eds (2011). Gender, Politics and Institutions: Towards a Feminists Institutionalism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mackay, Fiona (2008). ‘Thick’ Conceptions of Substantive Representation: Women, Gender and Political Institutions’, Representation, 44:2, 125–39.

- Mansbridge, Jane (1999). ‘Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent “Yes”’, The Journal of Politics, 61:3, 628–57.

- March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen (1984). ‘The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life’, American Political Science Review, 78:3, 734–49.

- Palmieri, Sonia (2013). ‘Sympathetic Advocates: Male Parliamentarians Sharing Responsibility for Gender Equality’, Gender & Development, 21:1, 67–80.

- Phillips, Anne (1994). ‘Democracy and Representation: Or, Why Should It Matter Who Our Representatives Are?’, SVPW-Jahrbuch, 34:1, 63–76.

- Phillips, Anne (1995). The Politics of Presence. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Pitkin, Hanna F. (1967). The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California.

- Reher, Stefanie (2018). ‘Gender and Opinion–Policy Congruence in Europe’, European Political Science Review, 10:4, 613–35.

- Rehfeld, Andrew (2017). ‘What Is Representation? On Being and Becoming a Representative’, in Mónica Brito Vieira (ed.), Reclaiming Representation - Contemporary Advances in the Theory of Political Representation. London: Routledge, 50–74.

- Saward, Michael (2010). The Representative Claim. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. (2010). Political Power and Women’s Representation in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Severs, Eline (2012). ‘Substantive Representation through a Claims-Making Lens: A Strategy for the Identification and Analysis of Substantive Claims’, Representation, 48:2, 169–81.

- Sobolewska, Maria, Rebecca McKee, and Rosie Campbell (2018). ‘Explaining Motivation to Represent: How Does Descriptive Representation Lead to Substantive Representation of Racial and Ethnic Minorities?’, West European Politics, 41:6, 1237–61.

- Squires, Judith (2008). ‘The Constitutive Representation of Gender: Extra-Parliamentary Re-Presentation of Gender Relations’, Representation, 44:2, 187–204.

- Stensöta, Helena (2020). ‘Does Care Experience Affect Policy Interests? Male Legislators, Parental Leave, and Political Priorities in Sweden’, Politics & Gender, 16:1, 123–44.

- Thelen, Kathleen (1999). ‘Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics’, Annual Review of Political Science, 2:1, 369–404.

- Washington, Ebonya L. (2008). ‘Female Socialization: How Daughters Affect Their Legislator Fathers’ Voting on Women’s Issues’, American Economic Review, 98:1, 311–32.

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart (2014). ‘Political Culture’, in Daniele Caramani (ed.), Comparative Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 284–301.

- Williams, Melissa S. (1998). Voice, Trust, and Memory: Marginalized Groups and the Failings of Liberal Representation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Xydias, Christina (2013). ‘Mapping the Language of Women’s Interests: Sex and Party Affiliation in the Bundestag’, Political Studies, 61:2, 319–40.

- Xydias, Christina (2014). ‘Women’s Rights in Germany: Generations and Gender Quotas’, Politics & Gender, 10:1, 4–32.

- Young, Iris M. (2000). Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.