Abstract

While policy responsiveness is a central criterion for successful democratic representation, little is known about citizens’ perceptions of whether governments are responsive to citizens’ preferences. This article asks how citizens’ perceptions of policy responsiveness are affected by egocentric and sociotropic congruence, that is, how distant the government is from their own and the median citizen’s position. Studying this question with cross-national European data, it is found that citizens consistently perceive governments that are close to their own positions as more responsive. In contrast, a significant effect of sociotropic congruence emerges only for the left-right scale but not for specific policy issues. Moreover, citizens react negatively to the government being distant from the median left-right position only when they themselves are also distant from the government. Overall, these findings indicate that citizens’ perceptions of policy responsiveness crucially hinge on whether they are personally well represented by government policy.

How can we assess whether modern representative democracy effectively institutionalises popular sovereignty? In the literature on democratic performance, responsiveness has emerged as a central normative yardstick and key indicator for successful democratic representation (Dahl Citation1971; Powell Citation2004). A large body of empirical work has studied the extent to which policy responsiveness—i.e. the degree to which policy decisions by governments and legislatures respond to citizen preferences—is achieved in modern democracies. This literature is divided into rather sanguine findings which indicate a notable degree of correspondence between citizens’ policy preferences and policymaking (e.g. Enns Citation2015; Hakhverdian Citation2010; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010; Stimson et al. Citation1995) and a more sobering account pointing out that political decisions are disproportionately more responsive to the preferences of socioeconomically privileged than disadvantaged groups (e.g. Bartels Citation2008; Gilens Citation2012; Elsässer and Schäfer Citation2023; Mathisen et al. Citation2023; Peters and Ensink Citation2015).

However, despite the normative significance of responsiveness for representative democracy, the burgeoning empirical literature on it, and consistent findings documenting inequalities in responsiveness, we know little about how citizens themselves perceive responsiveness (for exceptions, see: Bowler Citation2017; Goldberg et al. Citation2022; Esaiasson et al. Citation2017; Rosset Citation2023). This lack of research is deplorable, since citizens’ perspective on how democracy performs on various dimensions is important, not least for democratic stability (Claassen Citation2020; Lührmann Citation2021). Indeed, given findings of policy responsiveness being biased towards the rich, citizen perceptions of a lack of responsiveness may go some way in explaining their disillusionment with democracy (Dahlberg et al. Citation2015; Linde and Peters Citation2020) and the rise of populism (Hense and Schäfer Citation2022; Schäfer and Zürn Citation2023).

Thus, it seems important to better understand citizens’ perceptions of responsiveness. Do citizens understand responsiveness in the same way that democratic theorists do, that is, as responsiveness to the public at large? Or are they merely interested in the government passing the policies they personally desire and criticise it as unresponsive when it fails to do so? With this article, we contribute to closing the research gap on citizens’ perceptions of responsiveness by addressing the question of whether citizens abstract from their own position in applying a principled, ‘sociotropic’ criterion of democratic responsiveness or whether their evaluations are ‘egocentric’, i.e. driven by mere self-interest. More specifically, we assess how actual egocentric and sociotropic policy congruence affect perceptions of policy responsiveness across European democracies. Do citizens perceive governments that are close to the median citizen (sociotropic congruence) as more responsive? Or do citizens perceive governments that are close to their own positions (egocentric congruence) as more responsive? And might egocentric congruence affect how citizens react to sociotropic congruence?

While no direct empirical evidence on these questions exists, related research gives some indication that citizens may assess policy responsiveness primarily from an egocentric perspective. For example, studies have found that voters whose preferred party is part of the government assess responsiveness more favourably (Bowler Citation2017; Goldberg et al. Citation2022). Other research shows that even abstract preferences towards different ways of democratic decision-making are influenced by whether they bring about policy results that accord with one’s own preferences (Steiner and Landwehr Citation2023; Werner Citation2020). Most closely related to our focus on the effects of congruence, Mayne and Hakhverdian (Citation2017) find that satisfaction with democracy is only affected by egocentric, not by sociotropic congruence on the left-right dimension. To the best of our knowledge, however, ours is the first article to examine the combined impact of egocentric and sociotropic congruence—on the left-right dimension as well as on specific issues—on perceived responsiveness. Whereas satisfaction with democracy solicits citizens’ personal evaluations of the overall functioning of democracy, our focus on perceived responsiveness enables a more detailed investigation of how citizens assess this specific aspect of democratic quality, which seems more closely related to congruence from a conceptual vantage point.

Individual-level data to analyse the relation between congruence and perceived responsiveness are taken from rounds 6 (2012) and 10 (2020) of the European Social Survey (ESS), the two rounds which included the module on evaluations of democracy (Ferrín and Kriesi Citation2016). We combine these data with cabinet-level data on government positions calculated form the Chapel Hill Expert Survey’s (CHES) party position data. Our analysis draws on a sample of 51 cabinets from 28 European democracies and almost 50,000 individuals.

The results from multilevel regressions indicate that citizens perceive governments that are close to their own positions as more responsive. This holds consistently for both the general left-right dimension as well as more specific issue positions on redistribution, EU integration, and social lifestyle issues. In contrast, there is only mixed evidence that congruence with the median citizen matters for how citizens assess governmental responsiveness to popular majorities. While we find such an effect for distance to the median citizen on the general left-right dimension, none of the median citizen distances on the more specific issues turn out statistically significant. Moreover, we find that the effect of sociotropic left-right congruence is conditioned by egocentric congruence: Citizens react negatively to the government being distant from the median left-right position only when they themselves are also distant from the government. Overall, our findings suggest that citizens’ perceptions of policy responsiveness are significantly shaped by the degree to which they are personally well represented by government policies.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next section discusses perceptions of responsiveness, policy congruence, and how the two may be related. The third section introduces the data and methods that we use. The fourth section opens with descriptive results on how citizens in different European countries assess responsiveness and then presents the findings from our multilevel regression analysis. Section five concludes and ponders implications for future work on representation in contemporary democracies.

Previous research and theoretical argument

In this section, we first outline an encompassing conceptualisation of responsiveness, before zooming in on policy responsiveness and emphasising how its perception by citizens is important. We then take a closer look at previous research on the drivers of perceived responsiveness and go on to explicate the theoretical link between policy congruence and responsiveness perceptions.

Representation, responsiveness, and responsiveness perceptions

Representation is ‘an intrinsic part of what makes democracy possible’ (Urbinati and Warren Citation2008: 395). Successful democratic representation not only enables citizens to choose their political leaders in free and fair elections but also ensures that elected officials act responsively by taking citizens’ views into consideration when adopting new policies (Dahl Citation1971; Pitkin Citation1967). Esaiasson and colleagues (Esaiasson et al. Citation2015, Citation2017; Esaiasson and Wlezien Citation2017) distinguish three types of responsiveness actions that representatives can perform. First, representatives may listen to the public. This is an important precondition, for only if they stay informed about citizens’ preferences can representatives actually consider these preferences when deciding on policies. Moreover, if representatives take visible actions to stay informed about public sentiments, citizens have reason to feel that their voices are being heard. Second, representatives may explain their behaviour to citizens. Like acts of listening, providing justifications for policy positions and political decisions can assure citizens that their concerns have been taken into account. The third responsiveness action is policy adaption, where representatives adapt their policy decisions to the preferences of the public and implement policies in line with what most citizens want. In this study, we focus on policy adaption. Accordingly, we define perceived policy responsiveness as the perception that the government responds to public opinion by adapting its policy decisions to the preferences of the majority of citizens.

Policy adaption is the type of responsiveness action that has figured most prominently in empirical research. Numerous studies examine whether the preferences of citizens are reflected in policy output (e.g. Enns Citation2015; Hakhverdian Citation2010; Soroka and Wlezien Citation2010; Stimson et al. Citation1995) and whether policy responsiveness is biased towards the preferences of socio-economically privileged individuals (for a summary, see Elsässer and Schäfer Citation2023). Yet, as there are other ways to act responsively, governments do not necessarily need to adapt every policy to prevailing majority opinion but can instead explain their reasons for not doing so (Esaiasson et al. Citation2017: 742; Pitkin Citation1967: 209–210). Indeed, it can be debated how closely the government should follow the at times fickle public opinion, when exactly it should adjust policy decisions to the wishes of the majority, and when it would be better advised to discard the voice of the people and stick to the voice of reason (Sabl Citation2015). It is, nevertheless, largely uncontroversial that some level of policy responsiveness is crucial for democratic governance (Dahl Citation1971; Pitkin Citation1967; Powell Citation2004; Sabl Citation2015; Stimson et al. Citation1995). If elected governments continuously disregard citizens’ wishes in important questions, they risk undermining the legitimacy of democratic decisions and procedures.

However, whether responsiveness is realised and representation works must ultimately be judged by a democracy’s citizens themselves. For actual policy responsiveness to matter for citizens’ evaluations of democracy, citizens must notice whether the government is responsive or not. Individuals’ perceptions of responsiveness, in turn, have been shown to affect measures of political support, such as political trust and satisfaction with democracy (Catterberg and Moreno Citation2006; Dahlberg et al. Citation2015; Goubin Citation2020; Linde and Peters Citation2020). This suggests that citizens rely on policy responsiveness as one important criterion to assess whether democracy lives up to their demands.

In line with this interpretation, existent descriptive findings reveal that citizens, on the one hand, overwhelmingly want the government to reflect majority opinion—while they, on the other hand, generally perceive low levels of government responsiveness to their preferences (Bowler Citation2017; Goldberg et al. Citation2022; Rosset Citation2023). Thus, citizens value responsiveness as a normative goal but many do not believe that governments live up to it. This gap between expectation and evaluation makes it all the more important to examine what drives citizens’ responsiveness perceptions. Despite all this, our knowledge about how citizens perceive policy responsiveness in their own country and, particularly, how these perceptions come about is limited. We discuss existing research on this question next and develop our argument from there.

Previous research on the drivers of perceptions of policy responsiveness

So far, only a handful of studies have delved into explaining variation in the perceptions of policy responsiveness. A plausible explanation for this scarcity of research is that items directly measuring perceptions of policy responsiveness are seldom included in public opinion surveys. One topic that has attracted attention so far is the question of how well oneself is represented by the government.

For instance, Bowler (Citation2017: 777) expects individuals’ perceptions of government’s policy responsiveness to be ‘largely driven by short term factors’, most notably, by whether individuals voted for a party that ended up in government. Utilising data on 25 countries from the ESS round 6 (2012), he analyses respondents’ rating of the statement that the government of their country ‘changes policies in response to what most people think’ (that we will also use below). In line with his expectations, he finds that electoral winners perceive the government to be more responsive to popular opinion than electoral losers do. Goldberg, Deiss-Helbig, and Bernhagen (Citation2022) corroborate the relevance of winner/loser status based on German survey data from 2017. One reason why electoral winners may rate responsiveness higher is that their policy preferences are better represented by government policy.

Directly investigating the role of preference fulfilment, Esaiasson, Gilljam, and Persson (Citation2017) conduct a survey experiment in Sweden to study how perceived responsiveness is affected by the different responsiveness actions politicians may perform (see the last section). Accordingly, they draw on a broader measure of perceived responsiveness that comprises individuals’ perceptions of all three responsiveness actions. In the experiment on immigration policy, fictitious policy decisions vary, inter alia, in whether decisions taken are in line with (a) respondents’ own preferences and (b) respondents’ perceptions of what the majority wants. Esaiasson et al. find that both matter for perceived responsiveness: Perceived responsiveness is rated higher when decisions accord with individuals’ own preferences as well as their perceptions of majority preferences. However, accordance with own preferences exerts not only a somewhat larger effect than accordance with perceived majority preferences, perceptions of what the majority wants are strongly coloured by what respondents themselves want. From this, the authors conclude that perceptions of policy responsiveness are mostly driven by ‘outcome favourability’.

Taken together, previous research suggests that perceptions of whether governments are responsive to the citizenry may have strong egocentric roots. What is lacking, however, is a study that systematically examines the egocentric and sociotropic roots of responsiveness perceptions across a larger set of issues and in a cross-national setting. We present such a study, focusing on the question of how actual policy congruence with the government in both their egocentric and sociotropic forms—and their interplay—affect perceived responsiveness.

Policy congruence and perceptions of policy responsiveness

We will now first define the concepts of egocentric and sociotropic policy congruence more closely before discussing how these may matter for perceived responsiveness and considering how the effects of sociotropic and egocentric congruence may interact with one another.

Policy congruence captures the overlap between citizens’ and representatives’ policy positions. Different congruence relationships can be distinguished, depending on the number of citizens and representatives involved. Golder and Stramski (Citation2010) identify situations in which there is one citizen and one representative (‘one-to-one relationship’), situations in which there are many citizens and one representative (‘many-to-one relationship’), and situations with many citizens and many representatives (‘many-to-many relationship’). In the first situation, congruence describes the ideological distance between a given individual and one representative or representative institution. Following Mayne and Hakhverdian (Citation2017), we refer to congruence in a one-to-one relationship as egocentric congruence. Egocentric congruence is high when the absolute distance between the individual and the representative—in our case the government—is small. In the second and third situation, what matters is the correspondence between some distribution of citizens and one or more representatives. Like Mayne and Hakhverdian, we refer to the ideological overlap in these types of relationships as sociotropic congruence. The most prominent way to conceptualise sociotropic congruence is in terms of the policy proximity between the citizenry’s ‘most preferred’ position and the position of the government (a many-to-one relationship). In this relationship, sociotropic congruence is high when the distance between the median citizen and the government is small (Golder and Stramski Citation2010: 92–93).

Considering our definition of perceived policy responsiveness (as the perception that the government responds to public opinion by adapting its policy decisions to the preferences of the majority of citizens), it seems to suggest itself that perceived responsiveness should increase with sociotropic congruence. This is because when assessing responsiveness towards majority preferences, individuals are asked to adopt a sociotropic perspective.Footnote1 Accordingly, governments that hold policy positions similar to those of the median citizen might be perceived as enhancing majority representation when implementing policies. Conversely, citizens might consider low levels of sociotropic congruence as suggesting that the government is either unable or unwilling to enact policies in line with the preferences of the majority. Focusing on distance as the reverse of congruence (to align the hypothesis with our measurement below), we thus formulate a first hypothesis:

Sociotropic distance hypothesis: The more distant a government’s policy position is from citizens overall, the less responsive it is perceived to be.

In discussing how exactly egocentric congruence may affect responsiveness perceptions, we distinguish two mechanisms. A first mechanism, that one might call ‘social projection’, might operate through perceptions of what the majority wants that are biased towards one’s own views. A broad literature on the ‘false consensus effect’, originating in social psychology (Marks and Miller Citation1987; Ross et al. Citation1977), has shown that humans tend to significantly overestimate support for their own opinions, including their political preferences. To the extent that citizens project their own views onto others, they will tend to perceive responsiveness to collective preferences to be high when government policy accords with their own preferences. Under this mechanism, citizens may genuinely believe to assess responsiveness from a sociotropic perspective, but their perceptions of sociotropic congruence are coloured by congruence with their own views. Thus, as a result of egocentric bias in perceptions of majority preferences, egocentric congruence may matter for responsiveness perceptions (cf. Esaiasson et al. Citation2017).

A second mechanism, that one might call ‘genuinely egocentric’, is more direct and holds that even when asked about a procedural sociotropic judgement like the degree of majority responsiveness, citizens simply care most about instrumental egocentric considerations. In other words, citizens essentially substitute the question about majority responsiveness with a question about responsiveness to their own views as this is what is important to them.Footnote2 The conjecture that policy responsiveness is assessed from an egocentric perspective is in line with the finding that electoral winners rate responsiveness higher (Bowler Citation2017; Goldberg et al. Citation2022). In fact, egocentric policy congruence may be one important reason why electoral winners rate policy responsiveness higher: Those who voted for one of the governing parties will on average be closer to the government than those who voted for one of the opposition parties. Even more directly, the suggested mechanism is in line with Esaiasson et al.’s (Citation2017) finding that having one’s own preference fulfilled is associated with more positive assessments of responsiveness, holding perceived accordance with majority preferences constant.

While our data will not allow us to study these two mechanisms in isolation, we will test the following relationship that would result from them:

Egocentric distance hypothesis: The more distant a government is from an individual’s own position, the lower they perceive its responsiveness.

Egocentric filter hypothesis: Sociotropic distance reduces perceived responsiveness especially for citizens who are themselves distant from the government.

Data and methods

In order to examine what citizens think about responsiveness and to test our hypotheses, we turn to the democracy module of the ESS. The module was fielded in waves 6 (2012) and 10 (2020) of the survey. In a first step, the survey asked for people’s general preference for responsiveness. Specifically, respondents were asked whether ‘the government should change its planned policies if they are not in line with what most people think’ is best for the country or whether ‘the government should stick to its planned policies regardless of what most people think’. In a second step, the survey then asked for people’s perception of the extent to which responsiveness is fulfilled in practice—which forms our main outcome variable. Specifically, respondents were asked to assess how often ‘the government changes its planned policies in response to what most people think’ on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 10 (always). This question comes close to the operationalisation of citizens’ assessments of responsiveness suggested by Powell (Citation2004: 102; cf. Linde and Peters Citation2020: 296).

Unfortunately, those indicating a preference for the government to stick to its planned policies in the first question were not administered this subsequent question on perceived responsiveness. As a result, we have to discard this group of respondents.Footnote3 While this is a limitation, our analysis profits from the fact that only 16% of respondents indicated a preference for the government to stick to its planned policies (see in the Online Appendices). After accounting for other types of missing values, we still have information on perceived responsiveness for a vast majority of about 8 in 10 respondents (78.4% or 77,142 in total).

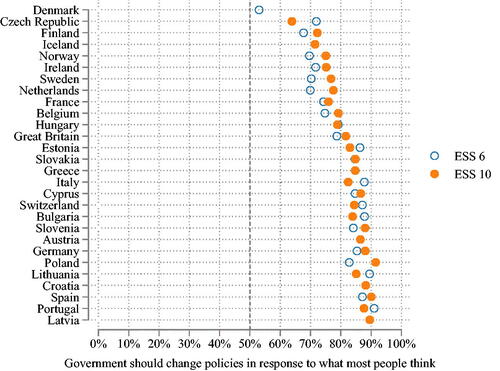

Figure 1. Preferences for responsiveness across countries and ESS waves.

Note: The figure shows—per country and ESS round—the share of respondents who say ‘the government should change its planned policies’ rather than ‘stick to its planned policies’ when most people disagree with them. ‘It depends’ and ‘don’t know’ excluded.

When considering government-citizen congruence, we take into account that, with the rising salience of cultural issues over the past decades, political conflict in Europe has become increasingly multidimensional (Hillen and Steiner Citation2020; Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Lefkofridi et al. Citation2014). Citizens may thus be inclined to think about the government’s position on specific issues when assessing its overall responsiveness. However, as new issues have become partly integrated into the meaning of left-right (Steiner Citation2023), they are likely to continue to think about congruence on an overall left-right dimension as well. Consistent with this ‘multidimensional’ perspective on congruence, recent work on political support points to the significance of both congruence on the left-right dimension and congruence on specific issues (Bakker et al. Citation2020; Stecker and Tausendpfund Citation2016). We therefore use left-right as well as issue-specific congruence.

To measure egocentric and sociotropic congruence, we combine data on citizens’ issue positions as measured by the ESS with data on party positions from the CHES (Jolly et al. Citation2022) from which we construct data on the positions of cabinets. Our mapping of issue items follows Stecker and Tausendpfund (Citation2016; cf. Rosset and Stecker Citation2019), who take advantage of the fact that largely similar issue scales have been included in both surveys for positions on the left-right scale, on redistribution, on ‘social lifestyle’ issues such as homosexuality, on European integration, and on immigrationFootnote4 (see Table A1 in the Online Appendices for question wordings in both surveys). To ease interpretation, we recoded all position items, for individuals and parties/cabinets, to range from 0 to 1.

Table 1. Multilevel regressions of perceptions of policy responsiveness.

To measure cabinet positions, we proceeded as follows. First, we took the positions of all parties being part of the governing coalition in office at the time of the ESS fieldwork. Specifically, we used the mean expert placements in the CHES wave preceding the respective ESS fieldwork, i.e. CHES 2010 for ESS 6 and CHES 2019 for ESS 10.Footnote5 Second, we followed standard practice of collapsing party positions into a cabinet position through a weighted mean (Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017; Rosset and Stecker Citation2019; Stecker and Tausendpfund Citation2016), with the weights representing a party’s share of the governing coalitions’ total number of seats in the legislature. Information on cabinet compositions and seat shares were obtained from ParlGov (Döring et al. Citation2023).

Based on these data, we computed two measures of congruence/distance. Egocentric congruence is operationalised as the absolute distance between an individual’s own position and the cabinet’s position. Sociotropic congruence is measured as the absolute distance between the median citizen position and the cabinet’s position. Our data include cabinet position data, and distances, for 51 cabinets from 28 European countriesFootnote6 covered by ESS 6 or 10. In Table A2 of the Online Appendices, we list these 51 cabinet cases with their positions, distances to the median citizen and mean levels of perceived responsiveness. In Online Appendix A, we also document further technical details on the coding of particular cabinets.

Because sociotropic congruence is measured at the cabinet level (or country-time combinations) and not the individual level, it is crucial to estimate the effects of interest in multi-level regressions. Because we also observe more than one context for some countries, we specify a model with three levels, with individuals (level 1), nested in cabinet contexts (level 2), nested in countries (level 3). In addition to the random intercepts for levels 2 and 3, we include a random slope parameter for egocentric congruence at level 2 (cabinets) when estimating the cross-level interaction between egocentric and sociotropic congruence. Given the quasi-continuous 11-point scale of the outcome variable, we estimate linear models.Footnote7

The models include a set of controls at the individual level. As demographic factors, we control for gender, age, education and household income quintile. Given findings on responsiveness being unequal, one might expect individuals with lower income and education to also perceive responsiveness as lower (cf. Ares and Häusermann Citation2023; Rennwald and Pontusson Citation2022; Rosset Citation2023). We also control for respondents’ level of interest in politics, re-scaled from zero to one, since individuals who are more interested in politics were previously found to evaluate government responsiveness more positively (Bowler Citation2017). Finally, since previous studies discovered winner/loser gaps in responsiveness perceptions (Bowler Citation2017, Goldberg et al. Citation2022), we consider individuals’ winner status, operationalised as having voted for a party currently in government. This is especially important as individuals who support a governing party may rate its responsiveness as high, while also adopting this party’s position. Thus, controlling for winner status addresses the concern that individuals’ distance to the government and their responsiveness perceptions may be correlated not because of an effect of egocentric congruence but rather because individuals’ policy preferences and their perceptions of responsiveness are both endogenous to party support.

Empirical findings

Before turning to the regression analysis, we first describe what preferences people hold regarding responsiveness and how they perceive the responsiveness of their national government.

Descriptive results

shows that in all countries a majority of citizens prefer governments to change their policies rather than to stick to them if they are not in line with public opinion. The only case in which this majority is slim is Denmark in 2013 (ESS 6), where only 53% of citizens prefer the government to change its policies in response to what most people think. In all but one other case (Czechia in 2021) those with a preference for the government to respond to what most people think outnumber those with a preference for sticking to preferred policies by a ratio of 2:1. In 38 of the 50 country-waves, the share of those with a preference for changing planned policies is even larger than 75%.

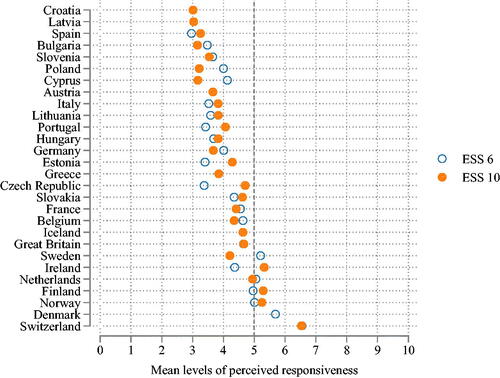

However, while oftentimes large majorities favour a government that is responsive to the preferences of the public, citizens regularly doubt that the government actually changes its policies in response to popular demand. The overall mean of perceived responsiveness is 4.1, well below the midpoint of the scale (=5). Overall, only 30% of respondents gave an answer above the midpoint and 53% below the midpoint (for a histogram showing the variable’s overall distribution, see of the Online Appendices). shows how respondents (excluding those who prefer the government to stick to its planned policies) assess government responsiveness in their country. The governments of only five countries (Denmark, Norway, Finland, Netherlands, and, most outstanding, Switzerland) are, on average, perceived to be responsive more often than not. Additionally, Ireland and Sweden reach above-average scores in at least one survey. In all remaining surveys, the average score is below the middle of the scale—in many of them markedly so. So, overall, there is a sizeable gap between expectations and perceptions in most, if not all, countries (see also of the Online Appendices). Notwithstanding low perceptions of responsiveness on average, there remains substantial variation in responsiveness perceptions across individuals, as indicated by a standard deviation of 2.5.

Figure 2. Perceptions of government responsiveness across countries and ESS waves.

Note: The figure shows the countries’ mean scores on the question ‘how often you think the government changes its planned policies in response to what most people think’?

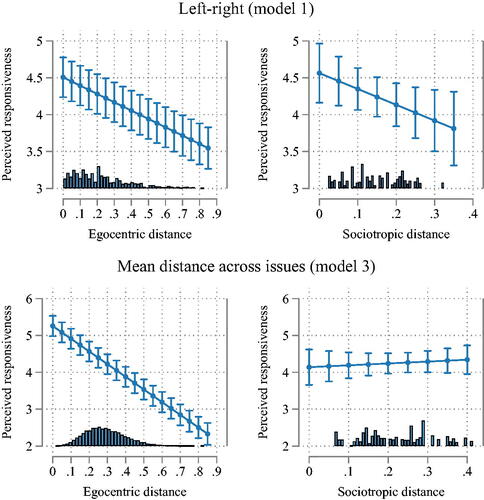

Figure 3. Predicted perceptions of government responsiveness across distances.

Note: Predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) calculated based on models 1 (left-right) and 3 (mean distance) from .

While rank-orderings of countries regarding both preferences for and perceptions of government responsiveness are broadly similar across ESS waves, there is also notable variation over time within countries. As to the perceptions of actual responsiveness (), mean scores increased in eleven countries, in most of them only slightly. Yet, in Portugal, Estonia, Czechia, and Ireland citizens rated responsiveness considerably higher in ESS 10. In nine countries, citizens became more sceptical that the government often responds to what most people think, most notably so in Poland, Cyprus, and Sweden.

Main regression analysis

presents the results from our main set of regressions. We present results from five different models. In models 1 to 3, we first study the effects of egocentric and sociotropic distance separately. In model 1, we use distances on the overarching left-right scale. Model 2 relies on distances on the four specific issues. In model 3, we utilise mean values of egocentric and sociotropic distances on the four specific issues to transform this into a more compact model. Models 4 and 5 include interactions between egocentric and sociotropic distance based on the left-right distances and these mean distances, respectively.

According to model 1, both higher egocentric distance as well as higher sociotropic distance to the median citizen on the left-right scale are significantly associated with lower levels of perceived policy responsiveness of governments. To communicate the magnitude of these effects, we plot predicted levels of perceived responsiveness across observed values of egocentric and sociotropic distance in (top). The effects are substantively relevant. For example, a one standard deviation increase in egocentric distance (0.17) is associated with a decrease in the average predicted value of perceived responsiveness by 0.19 scale points. Similarly, a standard deviation increase in distance to the median citizen (0.07) goes along with a reduction in perceived responsiveness of 0.16. Thus, the more distant a government is from oneself and the more distant it is from the median citizen on the left-right scale, the less it is perceived to ‘change policies in response to what most people think’. This supports the sociotropic distance and the egocentric distance hypotheses.

Model 2 also indicates strong effects of egocentric distance. Even when simultaneously included, three of the four egocentric distance variables exhibit statistically significant negative effects on perceived responsiveness.Footnote8 The more distant a government is from one’s own position on redistribution, EU integration, and social lifestyle issues, the less responsive towards the citizenry it is perceived to be. Increasing egocentric distance by one standard deviation lowers the predicted value of perceived responsiveness by 0.24 for redistribution, by 0.33 for EU integration and by 0.12 for social lifestyle issues. While we, surprisingly, obtain a statistically significant effect in the opposite direction for immigration, it is substantially very small and when including the issues one-by-one it is negatively signed as well (see Table D2 in the Online Appendices).

In contrast, none of the four sociotropic distance variables turn out statistically significant. The substantially largest effect (EU integration) even goes in the ‘wrong’ (i.e. positive) direction. Note that the four sociotropic distances all remain statistically insignificant when running four separate models, one per issue, instead (see Table D2 in the Online Appendices). In contrast, egocentric distances on redistribution, EU integration, and social lifestyle issues remain significantly associated with perceptions of lower responsiveness in these separate models. Even when further excluding the egocentric distances, the sociotropic distances, while then all negatively signed, remain insignificant (see Table D2 in the Online Appendices; and the bivariate scatterplots in which also support this conclusion).

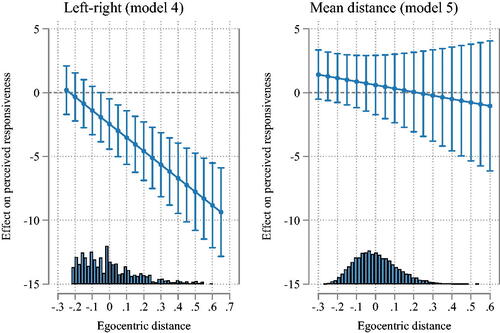

Figure 4. Effects of sociotropic distance on perceived responsiveness.

Note: Average marginal effects of sociotropic distance for different values of egocentric distance. Calculated based on models 4 (left-right) and 5 (mean distance) from .

Instead of studying the four specific issues separately, model 3 takes the means of the egocentric and sociotropic distances, respectively. This model allows for a more intuitive interpretation of how large the effects of egocentric and sociotropic distances are overall. Like model 2, model 3 reveals a significant effect of egocentric but not of sociotropic distance. A standard deviation increase in egocentric distance (0.11) is associated with a decrease in the average predicted value of perceived responsiveness by 0.39 scale points. As illustrated in (bottom-left), egocentric distance can make a substantial difference for how citizens assess responsiveness, decreasing perceived responsiveness by about 2.8 points when moving from the lowest to the highest mean distance. In contrast, for sociotropic distance the line is essentially flat (see bottom-right of ). Thus, results from the specific issues support the egocentric distance but not the sociotropic distance hypothesis.

Building on models 1 and 3, respectively, models 4 and 5 interact egocentric and sociotropic distances to test the egocentric filter hypothesis. For these models, we mean-centred the distance variables, such that the constituent terms in give the effects of (a) egocentric distance when sociotropic distance is at its mean and of (b) sociotropic distance when egocentric distance is at its mean. Note that the egocentric filter hypothesis implies a negative coefficient of the interaction term, indicating that the effect of sociotropic distance becomes more negative the higher the egocentric distance. In line with this expectation, the interaction term is negative in both models 4 and 5, but only statistically significantly so for left-right distances in model 4.

In , we plot the conditional effects of sociotropic distance across observed values of egocentric distance. For left-right distances, we observe a statistically significant negative effect of sociotropic distance only once egocentric distance passes a certain threshold. At high levels of egocentric distance, sociotropic distance makes a big difference: For example, when egocentric distance is at its maximum (0.60), a one standard deviation increase in sociotropic distance (0.073) is associated with a decrease in perceived responsiveness by −0.65. These results are in line with the egocentric filter hypothesis. However, for the mean across the specific issues, sociotropic distance never makes an appreciable difference for perceived responsiveness, even when egocentric distance is high.

Regarding the effects of control variables (see in the Online Appendices), we find some support for the unequal responsiveness perspective: Compared to the rich and those with tertiary education, those with lower incomes and lower levels of formal education (apart from those with below lower secondary education, surprisingly) perceive responsiveness to be lower. We also confirm the effect of being an election winner and show that it holds even when accounting for egocentric policy congruence. This suggests that the effect of getting one’s preferred party into government matters not only because it increases the chances of getting one’s policy preferences represented by the government. One’s own party having ‘won’ elections may matter for expressive in addition to instrumental policy reasons: Citizens likely feel better represented when the party they voted for is part of the government, even when holding policy proximity to the government constant (cf. Singh et al. Citation2012: 202). Furthermore, those with higher levels of political interest tend to assess responsiveness more positively. Perhaps surprisingly, perceptions of responsiveness are highest among the young.

In sum, we receive clear and consistent support for the egocentric distance hypothesis. The sociotropic distance and the egocentric filter hypotheses are only supported when measuring distances on the left-right scale, however.

Robustness checks

We conducted several additional robustness checks, listed in Online Appendix D. First, we re-estimated our models without the control variables, which leads to very similar results (see Table D1 and Figure D1). Second, we calculated distances based on z-standardised versions of the variables for citizen and government positions. While this approach invokes strong assumptions, it guarantees that citizen and government positions have equal means and variances and thereby responds to concerns over the comparability of scales. In the corresponding Table D3, we again find clear effects of egocentric distances, now with statistically significant negative effects for all issues. While sociotropic left-right distance is not statistically significant in the additive model, we do obtain significant negative interactions between egocentric and sociotropic distance in line with the egocentric filter hypothesis (only with p < 0.10 though). Sociotropic distances on the specific issues exhibit inconsistent effects and an insignificant one when using their mean. Third, we used the mean of distances between governments and citizens as an alternative measure of sociotropic congruence (Golder and Stramski Citation2010; Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017). As shown in Table D4 and Figure D3, the corresponding results are very similar to our main findings.

Fourth, we added macro-level control variables that we suspected may drive up (perceived) responsiveness. Three variables were sourced from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Citation2023): The level of electoral democracy (as higher quality of the electoral process might increase responsiveness and with it also the perception that it is fulfilled), the deliberative component index (as higher quality of public deliberation may drive up responsiveness and, when it is fulfilled, may help citizens realise that it is) and the direct popular vote index (as direct democracy may increase both actual and perceived responsiveness, as suggested by the exceptional high values observed in Switzerland). Additionally, we control for economic inequality via the Gini coefficient of disposable income as measured by the Standardised World Income Inequality Database (Solt Citation2020), suspecting that more people rate responsiveness low in less equal societies (cf. Bienstman et al. Citation2024). While leaving our main conclusions unchanged, the results in Table D5 suggest that governments are seen as more responsive when the quality of public deliberation is high, when there are more opportunities for direct democracy and when incomes are distributed more equally. Fifth, we excluded Switzerland, which constitutes an outlier in terms of its high levels of perceived responsiveness (see ) and is unusual in terms of its inclusive government coalitions. The results in Table D6 are close to our baseline results.

Sixth, we estimated our models separately for Western and Eastern European countries (see Table D7). The results are remarkably similar across these two groups of countries, though, with less power, the distance to the median citizen on the left-right scale is not statistically significant in specification 1 for either sample. However, we do find a significant interaction in line with the egocentric filter hypothesis in both samples, indicating that median citizen distance on the left-right scale lowers perceived responsiveness for citizens who are themselves distant from the government (see Figure D6).

Seventh, we explored how the effects of both egocentric and sociotropic distance may be conditioned by political sophistication. One could expect that both types of distances matter more the more politically sophisticated an individual is, given the knowledge required to form an assessment of (egocentric and sociotropic) congruence. We explore this in Table D11 interacting left-right distance and mean issue distance, respectively, with political interest as a proxy for political sophistication. In line with the expectation, effects of distance tend to be lower among those with low political interest (see Figure D8). This is more clearly the case for egocentric distances, though, and the differences in effect sizes are also modest there. Even among those with high political interest, sociotropic distance across the specific issues is still not statistically significant.

Overall, these additional checks indicate that our results hold up for different ways of measuring distance, under alternative sets of control variables and for different subsamples. Throughout, we obtain strong support for the egocentric distance hypothesis. Support for the other two hypotheses is mixed, and mostly limited to sociotropic distances on the left-right scale. For the left-right scale, we consistently find that larger distances from the median citizen are associated with lower levels of perceived responsiveness (only) when citizens are themselves distant from the government, in line with the egocentric filter hypothesis.

Discussion and conclusion

Given that responsiveness has become a central criterion for successful democratic representation, we set out to study how citizens themselves perceive policy responsiveness. In an initial step, our cross-national analysis of the 2012 and the 2020 ESS showed that an overwhelming majority of citizens think governments should change their policies if they are not in line with what most people think is best for the country. However, the data also revealed that when asked how often the government actually does change its policies, most European citizens perceive responsiveness to be low. Apparently, there is a considerable gap between citizens’ expectations and evaluations of responsiveness.

But what drives citizens’ perceptions of responsiveness? Combining the ESS data with data on party positions from the CHES, we found that they are significantly shaped by egocentric considerations. Citizens perceive governments that are close to their own policy positions as more responsive to the preferences of the majority of citizens. This effect of egocentric congruence holds consistently for general left-right positions and for more specific positions on redistribution, EU integration and social lifestyle. By contrast, we found only mixed evidence that citizens perceive governments that stand close to the median citizen as more responsive. A significant effect of sociotropic congruence emerged only for the general left-right scale; and, in line with our egocentric filter hypothesis, even this effect hinges on egocentric congruence: When citizens are themselves distant from the government, they perceive governments that are distant from the median left-right position as particularly unresponsive. By contrast, at low levels of egocentric distance, sociotropic distance does not make a difference for citizens’ responsiveness perceptions.

In showing that citizens assess policy responsiveness from an egocentric perspective, our findings confirm those reported in Esaiasson et al. (Citation2017). The strengths and weaknesses of the two very differently designed studies complement each other well. While Esaiason et al. conduct a survey experiment on immigration policy in Sweden that allows them to establish a causal relationship running from outcome favourability to responsiveness perceptions, our observational study demonstrates that egocentric congruence matters across several policy issues and in a diverse set of democracies. By design, our study cannot prove that congruence causes perceptions of high responsiveness, but can make somewhat stronger claims about external validity than Esaiasson et al.’s experimental study. More broadly, our finding also aligns with recent studies similarly demonstrating that citizens’ evaluations of the overall functioning of democracy (Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017; Stecker and Tausendpfund Citation2016), of democratic institutions and authorities (Noordzij et al. Citation2021), and even of abstract democratic procedures (Steiner and Landwehr Citation2023; Werner Citation2020) depend on whether they are or expect to be personally well-represented. In fact, perceptions of responsiveness might be a crucial intermediary step linking egocentric congruence to satisfaction with democracyFootnote9, political trust, and procedural preferences.

Regarding sociotropic considerations, our results confirm previous findings concerning their limited effect on citizens’ assessments of democratic quality. In our case, this might appear particularly worrisome since citizens were specifically asked to evaluate responsiveness towards majority preferences. However, in contrast to previous work (Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017), we do find that sociotropic distance to the median voter does have a considerable effect where the general left-right scale is concerned. That we do not find similar effects for specific policy issues might be due to the fact that an assessment of responsiveness in the both more abstract and more familiar left-right dimension is less demanding than assessments for individual issues: While respondents are probably unaware of majority (or even median) positions on EU membership or immigration, they may be assumed to have at least a hunch regarding the proportions of fellow citizens to their left and right, respectively.

At the same time, we need to keep methodological limitations in mind. First, measuring congruence is a thorny challenge in general, and while we improved upon previous studies by going beyond the left-right scale, the comparability of issue scales between citizens and elites remains a ground for concern, especially with regard to the specific policy issues. Second, it deserves to be noted that, statistically speaking, we have less power to detect effects of sociotropic congruence than to detect effects of egocentric congruence given the much lower number of observations at the cabinet level (n = 51) as compared to the citizen level (n ≈ 47,000). This means that we should not infer that the absence of a statistically significant effect of sociotropic congruence for the specific issues necessarily means that the true effect is zero. On these grounds, we caution against jumping to hasty conclusions about the irrelevance of sociotropic congruence. What we can be highly confident in are the strong and consistent effects of egocentric congruence.

This begs the question of whether it is normatively problematic that citizens assess responsiveness (primarily) from an egocentric perspective. From one perspective, the answer is not necessarily so. Even when all citizens assess responsiveness exclusively from an egocentric vantage point, governments still face an incentive to satisfy the preferences of a majority of citizens. On the other hand, when those who are distant from the government doubt not only the fulfilment of their personal preferences but also responsiveness to popular majorities, disaffection with the way democracy works is likely to grow and perceived legitimacy is likely to suffer among those personally distant from the government. But egocentric evaluations of responsiveness may not only lead to strongly polarised perceptions of whether the government is responsive to popular majorities as well as of the functioning of democracy more broadly, they may also cause perceived responsiveness to be low on average even for governments that are close to the median voter. Indeed, when responsiveness is assessed egocentrically, it is impossible for the government to satisfy everyone’s responsiveness expectations at once. Even a government that is close to the median citizen will frustrate responsiveness expectations of the (many) citizens whose personal positions differ from those of the median citizen. Hence, the primacy of the effect of egocentric congruence might go some way in accounting for why many citizens often tend to be rather dissatisfied with responsiveness (as shown in ).

Given the stakes involved, we hope for more research on citizens’ perceptions of responsiveness in the future—not least because comprehensive studies of perceived responsiveness seem an important complement to the literature on (unequal) ‘objective’ responsiveness. To facilitate such studies, it would be beneficial if measurements of perceived responsiveness were included in major surveys alongside standard measures like political trust and efficacy or satisfaction with democracy. Given that the measure used in the ESS is both more specific than these alternative measures and closer to plausible normative criteria for democratic performance, repeated measurements and cross-country comparisons could become an important source of information for scholars of democracy. An inclusion of the respective measures in panel studies would additionally enable assessments of within-person variation in response to changes in government and legislation. To allow clarifying the mechanisms behind the effects of (egocentric) congruence more closely, it would also be advisable to ask for responsiveness towards different objects (e.g. towards one’s own preferences and citizens overall) alongside citizens’ perceptions of where the public stands and to conduct further experimental research that reconsiders the effects of egocentric considerations on responsiveness perceptions. Such endeavours would allow insights into the extent to which citizens are genuinely egocentric or just misled by social projection. Finally, in terms of the three types of responsiveness actions distinguished by Esaiasson and colleagues (Esaiasson et al. Citation2015, Citation2017; Esaiasson and Wlezien Citation2017), we have focused only on one of those, i.e. the government’s willingness and ability to adapt policies to the preferences of the public. The degree to which governments achieve ‘deliberative responsiveness’ (Landwehr and Schäfer Citation2023) by listening to the public and explaining their decisions deserves more attention in future research.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (3.3 MB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented in research seminars at JGU Mainz and the University of Stuttgart and at the Dreiländertagung 2023 in Linz. We are grateful for the constructive feedback we received at these occasions. We would also like to thank WEP’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Miriam Gill, Timo Sprang, and Paul Weingärtner provided excellent research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Reproduction materials for this article are available at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2B1SEJ

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sven Hillen

Sven Hillen is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science, JGU Mainz. His research interests include: public opinion, party competition, and welfare state politics. His articles have appeared in journals such as European Journal of Political Research, Socio-Economic Review, and Electoral Studies. [[email protected]]

Nils D. Steiner

Nils D. Steiner is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science, JGU Mainz. He studies political processes in advanced democracies from a comparative perspective, with a focus on the political attitudes and the political behaviour of citizens in Western Europe. His articles have appeared in journals such as British Journal of Political Science, European Journal of Political Research, and Journal of European Public Policy. [[email protected]]

Claudia Landwehr

Claudia Landwehr is Professor of Political Theory and Public Policy at JGU Mainz. Her work focusses on democratic theory, citizens’ conceptions of democracy and process preferences. She has recently edited the book Contested Representation: Challenges, Shortcomings and Reforms (Cambridge University Press 2022, with Thomas Saalfeld and Armin Schäfer) and has published articles in journals including American Political Science Review, British Journal of Political Science, and The Journal of Political Philosophy. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Note that perceived responsiveness differs in this regard from constructs like democracy satisfaction, which ask about one’s personal satisfaction.

2 That citizens generally care strongly about egocentric congruence is demonstrated by a plethora of research. For example, empirical work has confirmed that egocentric congruence influences voter turnout and party choices (e.g. Hillen and Steiner Citation2020; Lefkofridi et al. Citation2014; Schäfer and Debus Citation2018). Moreover, citizens exhibit lower levels of political support if the policy positions represented in the party system do not coincide with their own (Bakker et al. Citation2020; Hillen and Steiner Citation2020). And most to the point, studies show that government-citizen (in-)congruence is (negatively) positively related to political support (Noordzij et al. Citation2021; Stecker and Tausendpfund Citation2016; Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017). Thus, our argument above essentially amounts to stating that this effect of egocentric congruence may extend to perceptions of policy responsiveness. As perceived responsiveness refers to the perception that the government responds to the preferences of the majority of citizens (rather than one’s own preferences), this link is not trivial, however—and thus worth investigating.

3 These respondents were instead asked how often ‘the government sticks to its planned policies regardless of what most people think’. While this is in one way a mirror image of the question on perceived responsiveness, it is not in another crucial way: It reverses the meaning of what constitutes a desirable behavior of the government (responding vs. sticking). Thus, we should not just reverse this scale and interpret it as an evaluation of responsiveness where higher values stand for more positive evaluations. That these answers measure something different is also revealed if we look at those respondents (n = 518) who accidentally answered both questions: Their answers to the two questions show almost no correlation (r=-0.06). Still, we verified that our main results remain robust if we combine the two measures in the suggested way (see Table D10 in the Online Appendices).

4 While this list is obviously not complete, the combination of these issues resonates well with the content of the two-dimensional spatial model consisting of an economic and a (socio-)cultural axis as described in the literature (e.g. Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Hillen and Steiner Citation2020; Lefkofridi et al. Citation2014). Moreover, Stecker and Tausendpfund (Citation2016) demonstrate these issues’ value for explaining satisfaction with democracy.

5 While it could also make sense to source the party position data from subsequent waves, we strived for consistency and used preceding waves in both cases, given the current absence of a subsequent CHES wave for ESS 10.

6 These are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland.

7 In Tables D8 and D9 of the Online Appendices, we show that our results are robust to specifying ordered (with the 11-point scale) and binary logistic regressions (with a dichotomized version).

8 In of the Online Appendices, we show pairwise correlations of all the distance variables. These correlations are not exceedingly high, reaching a value above 0.4 only twice (r = 0.47 for egocentric and sociotropic distance on redistribution and r = 0.58 for sociotropic distances on immigration and social lifestyle issues).

9 In our data, perceptions of policy responsiveness correlate with satisfaction with the way democracy works at 0.40. This is in line with our interpretation that these are distinct, but related constructs.

References

- Ares, Macarena, and Silja Häusermann (2023). ‘Class and Social Policy Representation’, in Noam Lupu and Jonas Pontusson (eds.), Unequal Democracies: Public Policy, Responsiveness, and Redistribution in an Era of Rising Economic Inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 300–23.

- Bakker, Ryan, Seth Jolly, and Jonathan Polk (2020). ‘Multidimensional Incongruence, Political Disaffection, and Support for anti-Establishment Parties’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27:2, 292–309.

- Bartels, Larry M. (2008). Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bienstman, Simon, Svenja Hense, and Markus Gangl (2024). ‘Explaining the “Democratic Malaise” in Unequal Societies: Inequality, External Efficacy and Political Trust’, European Journal of Political Research, 63:1, 172–91.

- Bowler, Shaun (2017). ‘Trustees, Delegates, and Responsiveness in Comparative Perspective’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 766–93.

- Catterberg, Gabriela, and Alejandro Moreno (2006). ‘The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18:1, 31–48.

- Claassen, Christopher (2020). ‘Does Public Support Help Democracy Survive?’, American Journal of Political Science, 64:1, 118–34.

- Coppedge, Michael et al. (2023). VDem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

- Dahl, Robert A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dahlberg, Stefan, Jonas Linde, and Sören Holmberg (2015). ‘Democratic Discontent in Old and New Democracies: Assessing the Importance of Democratic Input and Governmental Output’, Political Studies, 63:1_suppl, 18–37.

- Döring, Holger et al. (2023). Parliaments and Governments Database (ParlGov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Established Democracies. Development Version 03/23. https://www.parlgov.org/.

- Elsässer, Lea, and Armin Schäfer (2023). ‘Political Inequality in Rich Democracies’, Annual Review of Political Science, 26:1, 469–87.

- Enns, Peter K. (2015). ‘Relative Policy Support and Coincidental Representation’, Perspectives on Politics, 13:4, 1053–64.

- Esaiasson, Peter, Mikael Gilljam, and Mikael Persson (2017). ‘Responsiveness beyond Policy Satisfaction: Does It Matter to Citizens?’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 739–65.

- Esaiasson, Peter, Ann-Kristin Kölln, and Sedef Turper (2015). ‘External Efficacy and Perceived Responsiveness—Similar but Distinct Concepts’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 27:3, 432–45.

- Esaiasson, Peter, and Christopher Wlezien (2017). ‘Advances in the Study of Democratic Responsiveness: An Introduction’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 699–710.

- Ferrín, Mónica, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. (2016). How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Festinger, Leon (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Gilens, Martin (2012). Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Goldberg, Felix, Elisa Deiss-Helbig, and Patrick Bernhagen (2022). ‘Mitgenommen und dennoch abgehängt? Themenkongruenz und wahrgenommene politische Responsivität in Ost- und Westdeutschland’, in Martin Elff, Kathrin Ackermann, and Heiko Giebler (eds.), Wahlen und politische Einstellungen in Ost- und Westdeutschland: Persistenz, Konvergenz oder Divergenz? Wiesbaden: Springer, 89–116.

- Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski (2010). ‘Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions’, American Journal of Political Science, 54:1, 90–106.

- Goubin, Silke (2020). ‘Economic Inequality, Perceived Responsiveness and Political Trust’, Acta Politica, 55:2, 267–304.

- Hakhverdian, Armen (2010). ‘Political Representation and Its Mechanisms: A Dynamic Left–Right Approach for the United Kingdom, 1976–2006’, British Journal of Political Science, 40:4, 835–56.

- Hense, Svenja, and Armin Schäfer (2022). ‘Unequal Representation and the Right-Wing Populist Vote in Europe’, in Claudia Landwehr, Thomas Saalfeld and Armin Schäfer (eds.), Contested Representation: Challenges, Shortcomings and Reforms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 147–64.

- Hillen, Sven, and Nils D. Steiner (2020). ‘The Consequences of Supply Gaps in Two-Dimensional Policy Spaces for Voter Turnout and Political Support: The Case of Economically Left-Wing and Culturally Right-Wing Citizens in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 331–53.

- Jolly, Seth, Ryan Bakker, Liesbet Hooghe, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Vachudova (2022). ‘Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–’, Electoral Studies, 75, 102420. 2019

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Landwehr, Claudia, and Armin Schäfer (2023). ‘The Promise of Representative Democracy: Deliberative Responsiveness’, Res Publica, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-023-09640-0.

- Lefkofridi, Zoe., Markus Wagner, and Johanna E. Willmann (2014). ‘Left-Authoritarians and Policy Representation in Western Europe: Electoral Choice across Ideological Dimensions’, West European Politics, 37:1, 65–90.

- Linde, Jonas, and Yvette Peters (2020). ‘Responsiveness, Support, and Responsibility: How Democratic Responsiveness Facilitates Responsible Government’, Party Politics, 26:3, 291–304.

- Lührmann, A. (2021). ‘Disrupting the Autocratization Sequence: Towards Democratic Resilience’, Democratization, 28:5, 1017–39.

- Marks, Gary, and Norman Miller (1987). ‘Ten Years of Research on the False-Consensus Effect: An Empirical and Theoretical Review’, Psychological Bulletin, 102:1, 72–90.

- Mathisen, Ruben, Wouter Schakel, Svenja Hense, Lea Elsässer, Mikael Persson, and Jonas Pontusson (2023). ‘Unequal Responsiveness and Government Partisanship in Northwest Europe’, in Noam Lupu, and Jonas Pontusson (eds.), Unequal Democracies: Public Policy, Responsiveness, and Redistribution in an Era of Rising Economic Inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 29–53.

- Mayne, Quinton, and Armen Hakhverdian (2017). ‘Ideological Congruence and Citizen Satisfaction: Evidence from 25 Advanced Democracies’, Comparative Political Studies, 50:6, 822–49.

- Noordzij, Kjell, Willem De Koster, and Jeroen Van der Waal (2021). ‘The Micro–Macro Interactive Approach to Political Trust: Quality of Representation and Substantive Representation across Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 60:4, 954–74.

- Peters, Yvette, and Sander J. Ensink (2015). ‘Differential Responsiveness in Europe: The Effects of Preference Difference and Electoral Participation’, West European Politics, 38:3, 577–600.

- Pitkin, Hanna F. (1967). The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Powell, G. Bingham (2004). ‘The Chain of Responsiveness’, Journal of Democracy, 15:4, 91–105.

- Rennwald, Line, and Jonas Pontusson (2022). ‘Class Gaps in Perceptions of Political Voice: Liberal Democracies 1974–2016’, West European Politics, 45:6, 1334–60.

- Ross, Lee, David Greene, and Pamela House (1977). ‘The “False Consensus Effect”: An Egocentric Bias in Social Perception and Attribution Processes’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13:3, 279–301.

- Rosset, Jan (2023). ‘Perceptions of (Unequal) Responsiveness and Their Consequences for Electoral Participation’, Journal of European Public Policy, 30:8, 1565–87.

- Rosset, Jan, and Christian Stecker (2019). ‘How Well Are Citizens Represented by Their Governments? Issue Congruence and Inequality in Europe’, European Political Science Review, 11:2, 145–60.

- Sabl, Andrew (2015). ‘The Two Cultures of Democratic Theory: Responsiveness, Democratic Quality, and the Empirical-Normative Divide’, Perspectives on Politics, 13:2, 345–65.

- Schäfer, Constantin, and Marc Debus (2018). ‘No Participation without Representation: Policy Distances and Abstention in European Parliament Elections’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:12, 1835–54.

- Schäfer, Armin, and Michael Zürn (2023). The Democratic Regression: The Political Causes of Authoritarian Populism. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Singh, Shane, Ekrem Karakoç, and André Blais (2012). ‘Differentiating Winners: How Elections Affect Satisfaction with Democracy’, Electoral Studies, 31:1, 201–11.

- Solt, Frederick (2020). ‘Measuring Income Inequality across Countries and over Time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database’, Social Science Quarterly, 101:3, 1183–99. SWIID Version 9.6, December 2023.

- Soroka, Stuart N., and Christopher Wlezien (2010). Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stecker, Christian, and Markus Tausendpfund (2016). ‘Multidimensional Government-Citizen Congruence and Satisfaction with Democracy’, European Journal of Political Research, 55:3, 492–511.

- Steiner, Nils D. (2023). ‘The Shifting Issue Content of Left–Right Identification: Cohort Differences in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2214875

- Steiner, Nils D., and Claudia Landwehr (2023). ‘Learning the Brexit Lesson? Shifting Support for Direct Democracy in Germany in the Aftermath of the Brexit Referendum’, British Journal of Political Science, 53:2, 757–65.

- Stimson, James, Michael B. MacKuen, and Robert S. Erikson (1995). ‘Dynamic Representation’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 543–65.

- Urbinati, Nadia, and Mark E. Warren (2008). ‘The Concept of Representation in Contemporary Democratic Theory’, Annual Review of Political Science, 11:1, 387–412.

- Werner, Hannah (2020). ‘If I'll Win It, I Want It: The Role of Instrumental Considerations in Explaining Public Support for Referendums’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 312–30.