Abstract

Research on the welfare stances of populist radical-right parties (PRRPs) categorises them as ‘welfare chauvinists’ and ‘producerists’, supporting generous benefits exclusively for ‘hard-working’ nationals. However, it remains unclear whether their voters’ welfare preferences align with these positions. The argument advanced in this paper is that a comprehensive understanding of PRRP voters’ welfare preferences requires the examination of how solidarity and perceptions of welfare claimant deservingness interact. Thus, this article employs a factorial vignette survey experiment to evaluate the interplay between solidarity and deservingness perceptions among PRRP voters. Contrary to previous research, results show that PRRP voters do not exhibit stronger producerist attitudes; instead, they mostly stand out as particularly nativists. While PRRP voters exhibit significantly less solidarity towards welfare claimants deemed ‘least’ and ‘average-deserving’ than other partisans, they are not more solidaristic towards the ‘most deserving’ claimant. These findings challenge existing understanding of deservingness perceptions of PRRP voters, providing a new perspective on the study of their welfare attitudes.

In recent years, the stances of populist radical-right parties’ (PRRPs) on welfare state issues have gained salience both in their political programs and as a field of academic study (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018). The welfare position of such parties has been referred to as ‘welfare chauvinist’: prioritising community members’ access to welfare benefits while restricting access for immigrants (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018; Andersen and Bjørklund Citation1990; de Koster et al. Citation2013; Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2018; Reeskens and van Oorschot Citation2012; Rydgren Citation2004). Some have argued that welfare chauvinism implies also support for an actively generous welfare state – but, again, only for nationals (see Careja and Harris (Citation2022) for a literature review). Subsequent research has found that PRRP’s welfare state preferences also have a strong producerist component, represented by a clear distinction between ‘hard-working’ individuals from ‘free riders’ – even for nationals (Abts et al. Citation2021; Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2016, Citation2018; Ivaldi and Mazzoleni Citation2019; Otjes et al. Citation2018; Rathgeb Citation2021). This authoritarian twist to the moral duty to work and reciprocate implies that individuals who deviate from this social norm are deemed ‘undeserving’ by PRRPs and should be disciplined in an expression of PRRPs’ ‘punitive conventional moralism’ (Mudde Citation2007, 23).

While the literature on PRRPs’ distributive agendas has grown rapidly in recent years, empirical evidence on whether PRRP voters share the parties’ welfare positions remains inconclusive. Research shows that PRRP voters are aligned with their parties in their preference for restricting benefits for ‘undeserving’ claimants (Attewell Citation2021; Busemeyer et al. Citation2022; Goubin and Hooghe Citation2021; Loxbo Citation2022), reflecting their populist, nativist, and authoritarian core ideologies on welfare attitudes. However, their preference regarding welfare generosity is unclear. On the one hand, there is solid evidence that economic concerns motivate PRRP voting (Dehdari Citation2022; Gidron and Hall Citation2017, Citation2020; Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2019; Häusermann et al. Citation2022). In line with this finding, studies have shown that PRRP voters prefer a welfare state based on compensatory social benefits (Busemeyer et al. Citation2022). Paradoxically, studies have not confirmed the notion that these voters prefer a generous welfare state. Instead, research has suggested that PRRP voters support benefits with moderate generosity (Attewell Citation2021; Busemeyer et al. Citation2022; Goubin and Hooghe Citation2021).

Previous research on PRRP voters’ welfare preferences has relied on observational data, using survey data on respondents’ declared position on distributive issues. Although such studies clearly contribute to the understanding welfare priorities of these voters and their views on different groups’ access to the welfare state, they cannot account for how their views on claimants’ perceived deservingness interact with their preferences for welfare generosity (Petersen et al. Citation2011), thus missing an explanation for precisely how the cultural and economic dimensions are interlinked in PRRP voters’ welfare preferences. As a result, it is unclear whether PRRP voters’ fear that ‘undeserving’ individuals might profit from the welfare state is associated with limited support for the welfare state or, instead, with selective solidarity. Given ongoing welfare reforms in many European states aimed at reducing entitlements for ‘undeserving’ immigrants (Careja et al. Citation2016; Chueri Citation2021; Kramer et al. Citation2018), it is important to assess the extent to which PRRP voters support a generous welfare state for deserving claimants when given full discretion over allocation.

In order to address this limitation, this study uses a factorial vignette survey experiment to examine how PRRP voters’ welfare solidarity is associated with perceptions of deservingness of the unemployment benefit claimant. It draws theoretically on deservingness research to identify key criteria for perceived deservingness: need, identity, control, effort, and reciprocity (Knotz et al. Citation2022; van Oorschot Citation2000, Citation2006, 2012), which we then apply to the case of PRRP voters’ welfare state preferences. This experimental design allows us to isolate the effect of each deservingness criterion on welfare solidarity. By incorporating the role of deservingness perceptions directly into research on the demand side of PRRPs, we answer four main questions: (1) Which deservingness criteria are relevant to PRRP voters? (2) To what degree do these criteria differ from other voters? (3) How solidaristic are PRRP voters in comparison to other voters? and (4) How dependent is PRRP voters’ welfare solidarity on the fulfilment of those criteria?

To answer to these questions, we rely on respondents from two countries with Social Democratic welfare regimes, (Denmark and Sweden) and two countries with Conservative welfare regimes (Germany and Switzerland). This case selection aims to account for literature findings that welfare regimes influence how individuals evaluate the deservingness of welfare claimants (Laenen et al. Citation2019; Larsen Citation2008; Taylor-Gooby et al. Citation2019; van der Waal et al. Citation2013; van Oorschot Citation2006).

Our results indicate that PRRP voters’ views on welfare distribution are not more producerist than those of other partisans, leading us to question the idea that long contributory records and other markers of ‘hard work’ are more relevant to PRRP voters than to other voters. What distinguishes PRRP voters’ perceptions of deservingness is their particular punitiveness towards immigrants. Identity emerges as a more important deservingness criterion for PRRP voters than for other voters, although there is no significant difference between mainstream right and PRRP voters regarding the importance they attribute to the nationality of the welfare claimant.

We, moreover, find that PRRP voters’ welfare solidarity is highly contingent on the fulfilment of the deservingness criteria they deem relevant. While PRRP voters exhibit significantly less solidarity towards welfare claimants deemed ‘least’ and ‘average-deserving’, they express an equal level of solidarity with both mainstream right and left-wing voters when it comes to the ‘most deserving’ welfare claimants. Thus, we confirm the notion that PRRP voters present a selective solidarity but find no support for claim that they support a generous welfare state, at least when it comes to unemployment benefits. Finally, in line with previous research (Arts and Gelissen Citation2001), our analysis reveals that the importance of deservingness criteria shows little variation across welfare regimes.

These findings carry important implications for how the literature understands PRRP voters’ welfare preferences and their connection to contemporary transformations of the European welfare state in response to trends such as globalisation. They suggest that the support for reduced welfare benefits for immigrants does not come together with demands for higher protection for the ‘deserving’ nationals. Instead, PRRP voters support comparative lower benefits.

Radical-right welfare position: supply and demand sides

The literature has argued that distributive positions have a secondary importance for the PRRPs’ agenda (Mudde Citation2007). However, as PRRPs are beginning to occupy powerful positions around the world, the question of which policies they promote beyond immigration has again come to the fore (Afonso Citation2015). More recent research has shown that distributive issues have gained salience over time in PRRPs’ manifestos (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018) and that these issues are attracting voters (Krause and Giebler Citation2020). As a result, the welfare state ideology of PRRPs has received significant scholarly attention in recent years. A central finding of this literature is that nearly all PRRPs have shifted leftward on distributive issues over the last two decades (Afonso Citation2015; Afonso & Rennwald Citation2018; de Lange Citation2007; Lefkofridi and Michel Citation2014; Marks et al. Citation2006; Röth et al. Citation2018; Rydgren Citation2004; Zaslove Citation2009). Another important finding is that so-called ‘welfare chauvinism’ has come to distinguish PRRPs’ ideology (Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2018; Ivarsflaten Citation2008; Mudde Citation2007).

Building on this, recent work on PRRPs’ welfare positions has also challenged claims that the parties are ‘blurring’ their welfare preferences, advocating for a mix of right- and left-wing welfare policies (Rovny Citation2013; Rovny and Polk Citation2020). Instead, their ostensible incoherence results not from a ‘blurred’ welfare position but rather from a dualistic welfare platform: supporting a generous welfare state that emphasises ‘passive’ income replacement over ‘active’ investment and services for the ‘deserving’, while seeking to exclude or make subject to strict conditionalities those who are seen as ‘undeserving’ (Chueri Citation2022; Enggist and Pinggera Citation2022; Fischer and Giuliani Citation2023; Otjes Citation2019).

Research also provides indications regarding how exactly PRRPs draw the line between the ‘deserving’ and the ‘undeserving’ and points to two central ideological concepts: Nativism and producerism. Nativism, described by Mudde (Citation2016) as ‘xenophobic nationalism’, is, in essence, the idea that the interests of native-born citizens should always be put ahead of those of immigrants (‘taking care of our own first’), which informs PRRPs’ calls to exclude or at least disadvantage immigrants when it comes to accessing social protection (Andersen and Bjørklund Citation1990; van der Waal et al. Citation2010). Producerism, the second key dimension on which PRRPs distinguish between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’, refers to the purported conflict between the ‘makers’ (i.e., those who work hard and contribute to society) and the ‘takers’ (i.e., ‘welfare cheaters’, ‘parasites’, and ‘abusers’) (Abts et al. Citation2021; Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2016, Citation2018; Ivaldi and Mazzoleni Citation2019; Otjes et al. Citation2018; Rathgeb Citation2021). While seeing contributing ‘makers’ as more deserving than ‘takers’ is a general human trait (Petersen Citation2012), research indicates that PRRPs place particularly strong emphasis on this aspect (Rathgeb Citation2021). In the area of welfare state policies, producerism thus translates into a desire to limit benefits strictly to those adhering to a traditional work ethic while disciplining and punishing those who deviate from this norm, such as persons with short employment records, ‘choosy’ or ‘lazy’ benefit claimants, and welfare ‘cheaters’ (Abts et al. Citation2021; Achterberg et al. Citation2014; Busemeyer et al. Citation2022). Overall, this way of distinguishing between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ welfare recipients based on producerist and nativist ideas means that factors that are traditionally understood as cultural (e.g., nationality, ethnicity, work ethic) have become core to PRRPs’ distributive welfare preferences.

While substantial research has examined the welfare positions of PRRPs, the extent to which their voters’ welfare preferences match those positions is still an open question in the literature. Early studies downplayed the relevance of distributive issues for PRRP voters, arguing that such voters prioritise the cultural dimension over distributive concerns (Bornschier and Kriesi Citation2013; Mudde Citation2007; Oesch Citation2008). Nonetheless, research has shown that PRRPs have expanded their electorate, particularly among working-class voters, by adopting a relatively pro-welfare position (Afonso and Rennwald Citation2018; Arzheimer Citation2012; Krause and Giebler Citation2020). Related studies have pointed out that economic concerns are associated with PRRP voting (Dehdari Citation2022; Gallego and Kurer Citation2022; Gidron and Hall Citation2020; Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Citation2019).

Although evidence suggests that distributive issues are generally important for PRRP voters, their position on welfare generosity so far still appears ambivalent. On the one hand, research shows that these voters are often economically vulnerable and favour welfare protection in the form of compensatory income benefits (Busemeyer et al. Citation2022; Goubin and Hooghe Citation2021; Loxbo Citation2022). On the other hand, they support only moderate benefit levels in combination with workfare measures, welfare cuts for immigrants, and stricter eligibility conditions (Busemeyer et al. Citation2022; Goubin and Hooghe Citation2021; Loxbo Citation2022).

These apparently contradictory welfare state preferences may be associated with concerns that ‘undeserving’ recipients (e.g., immigrants and ‘welfare cheaters’) would benefit from welfare benefits. However, it remains uncertain whether this apprehension among PRRP voters has translated into a preference for less generous benefits or support for reduced benefits for those deemed ‘undeserving.’ Thus, we suggest that the key to fully understanding their welfare state preferences is to more clearly draw the connection between their perceptions of deservingness as defined by nativism and producerism (which can also be seen as two forms of conditionality) and their attitudes towards the generosity of welfare states. In the following, we draw on the well-established sociological literature on the determinants of perceptions of welfare deservingness to develop specific hypotheses about how PRRP voters define deservingness, how this, in turn, translates into overall welfare state preferences, and how they differ in these regards from other voters.

Determinants of deservingness perceptions among PRRP voters

Are PRRP voters particularly ‘producerist’ and ‘welfare chauvinistic’?

Selective solidarity is not a new issue in political studies: voters have long been known to view claimants as differentially deserving of welfare. However, the issue has become more salient as pressure on European welfare states has intensified due to budgetary constraints, population ageing, and increasing diversity. Early studies on deservingness perceptions have empirically identified five criteria that determine perceptions of deservingness: control, attitude, reciprocity, identity, and need (CARIN) (Van Oorschot Citation2000, Citation2006). These criteria have since provided a framework for empirical studies and contributed to the quickly growing literature on the topic. In short, those who are generally considered the most deserving of social services and benefits are those who are seen as not responsible for their situation (control), are compliant or even docile (attitude), have contributed to society (reciprocity), are regarded as ‘one of us’ (identity), and have greater need (van Oorschot Citation2000, Citation2006; van Oorschot et al. Citation2017).

Empirical research generally supports the relevance of the CARIN criteria in explaining perceptions of deservingness across different contexts. However, recent work has identified a conceptual overlap between reciprocity and attitude (Knotz et al. Citation2022) and some studies have similarly concluded that attitude is not actually a significant factor driving deservingness perceptions (Heuer and Zimmermann, Citation2020; Laenen et al. Citation2019). Simultaneously, research has started to differentiate between two types of reciprocal actions, those that occurred in the past (such as past taxes and contributions paid) and those that are performed in the present (such as current active job search). Following this approach (e.g., Gandenberger et al. Citation2022; Kootstra Citation2016; Reeskens and van der Meer Citation2019), we use effort to denote an individual’s attempt to end their need and reciprocity to refer to their past contributions (e.g., gainful employment and paying taxes). In sum, we suggest that the following criteria are most suitable for studying deservingness perceptions, including those of PRRP voters: need, identity, control, effort, and reciprocity (Knotz et al. Citation2022) – abbreviated NICER.

We expect that PRRP voters differ from other voters particularly strongly in the extent to which they place importance on four of these criteria. First, PRRP voters’ nativist preferences – as mentioned above, an ethnic idea of belonging and the belief that the native-born population and its culture should come first (Betz Citation2019) – should lead them to give especially high importance to the identity criterion. We also expect that members of the working class within the social democratic electorate should demonstrate limited solidarity towards immigrants, mainly due to concerns about resource competition (Kitschelt and McGann Citation1997; Mewes and Mau 2012). However, the base of these party supporters is increasingly populated by middle-class voters, who tend to have more favourable views regarding immigrants’ access to social benefits (Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015). Additionally, a segment of mainstream right-wing voters is likely to favour reduced benefits for immigrant welfare claimants, citing budgetary or cultural concerns (Gidron Citation2022). This electorate, however, is also not homogeneous; some of these voters uphold cosmopolitan values and are likely to consider immigrants as equally deserving of benefits (Gidron Citation2022; Kurella and Rosset Citation2017; Van Kersbergen and Krouwel Citation2008). Consequently, we anticipate that identity will assume a relatively more pivotal role for PRRP voters compared to other voters.

Moreover, we anticipate that the producerist approach of PRRP voters to welfare distribution will be associated with a heightened emphasis on control, effort, and reciprocity criteria. As stated earlier, producerism distinguishes between productive members of society and those exploiting public welfare without contributing. Aligned with this perspective, PRRP voters will ascribe higher importance to welfare claimants’ adherence to norms of hard work, reciprocation, and compliance with rules and procedures for benefit entitlement (Abts et al. Citation2021; Busemeyer et al. Citation2022). Thus, this welfare attitude will mean that PRRP voters’ will reward recipients who have long employment records (reciprocity), who find themselves in need unintentionally, who are not ‘choosy’ or ‘lazy’ (control), and who work diligently to end their unemployment (effort). Conversely, they will also ascribe higher penalties to welfare claimants who do not fulfil those conditionalities.

Certainly, these criteria should also be relevant to other voters as well. Specifically, voters of conservative mainstream right-wing parties are also likely to place high importance on reciprocity and effort in finding employment as conditions for accessing welfare benefits (Barry 1997). However, due to the PRRPs’ authoritarian core ideology, we anticipate that PRRP voters will enforce larger generosity penalties on those who deviate from the ‘desired’ behaviour (Rathgeb Citation2021). Conversely, the criterion of need is expected to be less emphasised among PRRP voters compared to others.

Based on these considerations, we posit five hypotheses on PRRP voters’ perception of deservingness (‘conditionality’):

H1: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see immigrant welfare claimants as less deserving (‘nativism’).

H2: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see welfare claimants with shorter contributory records as less deserving (‘producerism’).

H3: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see welfare claimants who do not show any effort to end their need as less deserving (‘producerism’).

H4: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see welfare claimants more in control of their situation as less deserving (‘producerism’).

H5: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see welfare claimants in greater need as less deserving.

H2a: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see immigrant welfare claimants with shorter contributory records as less deserving.

H3a: Compared to voters of other parties, PRRP voters see immigrant welfare claimants who do not show any effort to end their need as less deserving.

H4a: Compared to voters of other parties, PRR voters see immigrant welfare claimants more in control of their situation as less deserving.

Are PRRP voters more solidaristic towards the ‘deserving’ unemployment claimants?

Considering the effect of PRRP voters’ deservingness perception on welfare generosity, we anticipate their level of solidarity to be strongly correlated with the fulfilment of the criteria they deem relevant for deservingness (i.e., identity, reciprocity, control, and effort). This selective solidarity will lead them to assign high replacement rates to welfare claimants who meet those conditionalities and, conversely, impose sizable penalties for those who deviate.

Conversely, while identity, reciprocity, control, and effort should also be relevant for left-wing voters, we expect their overall solidarity to be less contingent on the fulfilment of these conditions. At the same time, left-wing voters should support relatively generous benefit levels and be averse to inequality, thus consistently assigning relatively high benefit levels without great differentiation among claimants (Abou-Chadi et al. Citation2021; Häusermann et al. Citation2023). Compared to left-leaning voters, we thus expect PRRP voters to exhibit lower levels of solidarity when assessing an ‘average deserving’ welfare claimant and a beneficiary they deem the ‘least deserving.’ We therefore propose two additional hypotheses regarding the level of solidarity among PRRP voters compared to left-wing voters.

H6: Compared to voters of left-wing voters, PPPR voters assign lower replacement rates to the ‘least deserving’ welfare claimants.

H7: Compared to voters of left-wing parties, PPPR voters assign lower replacement rates to ‘average deserving’ welfare claimants.

However, we have competing expectations regarding the solidarity of PRRP voters compared to left-wing voters towards welfare claimants who meet nativist and producerist conditionalities – such as nationals committed to contributing to the nation’s wealth by working and paying taxes. Following the idea that the fear that the ‘undeserving’ will access benefits will lead PRRP voters to demonstrate overall limited solidarity, we expect them to show less solidarity towards deserving welfare claimants than left-wing voters. Conversely, aligning with the claim that PRRP voters exhibit selective solidarity, defending generous benefits for hard-working nationals, we anticipate PRRP voters to be at least equally solidaristic towards a ‘deserving’ welfare claimant compared to a left-wing voter.

H8: Compared to voters of left-wing parties, PPPR voters assign lower replacement rates to highly deserving welfare claimants.

H8a: Compared to voters of left-wing parties, PPPR voters assign similar or higher replacement rates to highly deserving welfare claimants.

The potential role of institutions

Finally, we also anticipate that welfare institutions will influence how individuals assess the deservingness of welfare claimants, regardless of their partisanship (Laenen et al. Citation2019; Larsen Citation2008; Taylor-Gooby et al. Citation2019; van der Waal et al. Citation2013; van Oorschot Citation2006). Studies have concluded that the relevance of identity is lower in Social Democratic welfare states, as generous and universally distributed social benefits foster solidarity and reduce the perception of scarcity and welfare competition between nationals and foreigners (van der Waal et al. Citation2013). Moreover, there is evidence that the importance of reciprocity as a relevant distributive principle should be stronger in Conservative welfare regimes compared to Social Democratic welfare regimes (Taylor-Gooby et al. Citation2019). Therefore, we expect that the nationality of the welfare claimant and their contributory record will be stronger determinants of solidarity for respondents in Conservative welfare regimes compared to Social Democratic welfare regimes.

Data and research strategy

Our analysis is based on original data collected by a market research and opinion polling company (Bilendi) from 2,877 respondents from Germany, 1,393 from Switzerland, 1,342 from Denmark, and 1,341 from Sweden.Footnote1 Respondents were recruited according to country quotas on gender, education (low, middle, high), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, over 75), and geographic area (rural and urban).Footnote2 The distribution of respondents across those sociodemographic variables are available in the Online Appendix ().

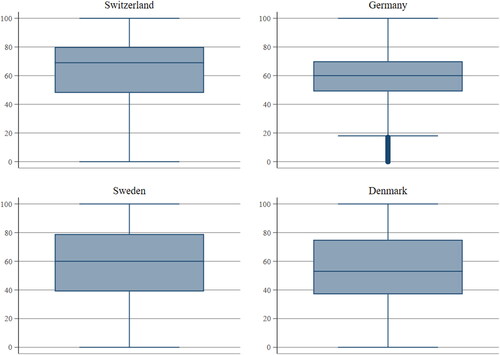

Figure 2. Box plots of the distribution of the unemployment replacement rate attributed by respondents in Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark.

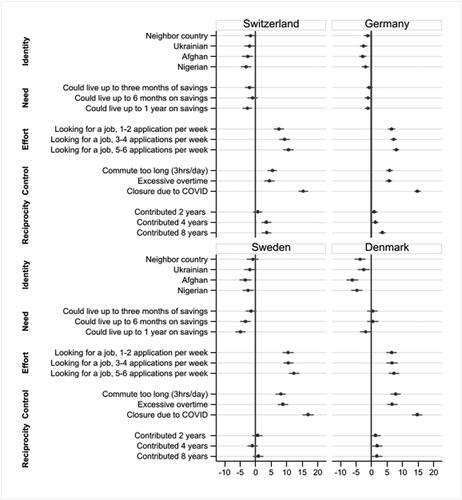

Figure 3. The importance of deservingness criteria in Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark, with 95% confidence intervals.

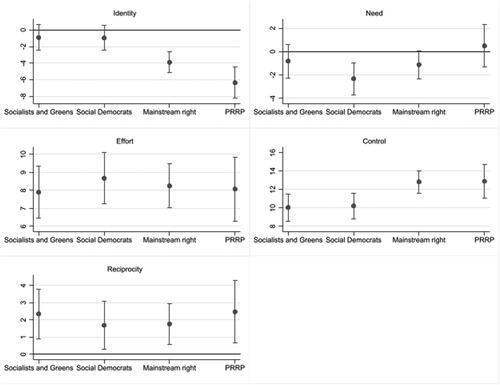

Figure 4. Marginal effects of identity, need, effort, reciprocity, and control on solidarity, by partisanship, with 95% confidence intervals.

Fieldwork was conducted from 13 July 2021 to 22 November 2021. This period was deliberately chosen since the number of COVID-19 infections was declining at the time, meaning that public health was under relative control. Thus, we expected respondents’ public health concerns to have only minor effects on their welfare solidarity. We do, however, acknowledge that solidarity towards the unemployed might have been affected since many people lost their jobs during the COVID-19 crisis. We therefore added the pandemic as a possible cause of unemployment in the survey, to capture the solidarity towards welfare claimants that lost their jobs due to this extraordinary circumstance.

Our online survey included fractional factorial vignette experiments (Auspurg and Hinz 2015). We adopt a D-efficient design that guarantees that the vignettes’ main effects and interactions between the vignette and respondent characteristics are mutually uncorrelated (Dülmer Citation2016).Footnote3 Studies have identified an experimental design as the most appropriate methodology to analyse welfare deservingness perceptions (Reeskens and van der Meer Citation2017). This methodology is preferable to traditional surveys, in which social desirability is a concern (Auspurg et al. 2014). According to Laenen et al. (Citation2019), capturing the importance of identity without an experimental approach can be challenging, as individuals tend to hide their xenophobia. We therefore conducted a survey with a factorial vignette experiment (Auspurg and Hinz 2015), in order to assess how individuals perceive claimants’ deservingness of unemployment benefits.

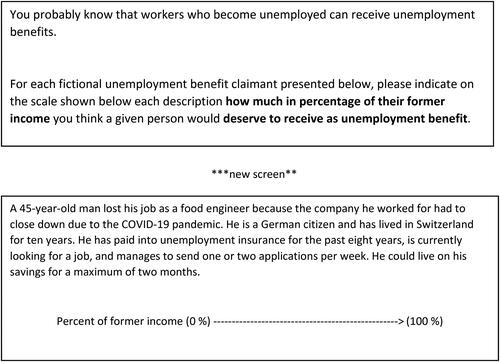

In the experiment, respondents were presented with three vignettes describing a fictitious unemployment claimant and were asked to determine the percentage (from 0 to 100%) of their previous income that each person described in the vignette should receive. Vignettes are country-specific, ensuring that respondents encounter a vignette in their native language,Footnote4 adapted to the local context (refer to country-specific adaptations in ). shows an example of a translated vignette presented to the Swiss sample. 8,053 vignettes were evaluated in Germany, 3,929 in Switzerland, 3,681 in Sweden, and 3,618 in Denmark, amounting to 19,281 welfare claimant profiles. Claimant characteristics varied randomly (see for respondent characteristics). Apart from characteristics that account for the control, reciprocity, effort, need, and identity, vignettes include welfare claimant’s age, gender, and occupation. These additional characteristics aim to give more specific cues about the claimants and control for literature findings that indicate that PRRP voters prioritise middle-aged men with lower occupational status (factors that did not prove significant in our study). This research design allowed us to simultaneously capture respondents’ preferred benefit levels and how deservingness criteria affect welfare solidarity. It also permitted us to isolate the importance of each deserving criterium on the welfare generosity.

Table 1. Vignette attributes.

In order to allow cross-country comparisons of welfare attitudes of PRRP voters in relation to other voters, we categorised respondents’ party choices into five categoriesFootnote5: Socialists and Green party voters, Social Democrat voters, Mainstream Right-Wing party voters, and PRRP voters. Individuals who voted for a small party not included in the listed options, did not remember their party choice, or chose not to disclose their political party preference, were classified as ‘other.’ The parties considered in each category and their respective vote shares are available in the Online Appendix (Table A1). These ratios provide an accurate representation of electoral results (Figure A5).

Figure 5. Marginal effects of effort, reciprocity, and control on solidarity, by partisanship, for an immigrant welfare claimants, with 95% confidence intervals.

Due to the hierarchical structure of our data (evaluations nested in respondents), we use multilevel linear models with random intercepts, and random slopes when including a cross-level interaction between vignette and respondent characteristics. The next section discusses the results of the experiments (comparing PRRPs and other voters). It also evaluates the deservingness criteria of the vignettes and what this means for respondents’ solidarity towards welfare claimants.

Results

We first consider respondents’ solidarity. shows the box plot of the distribution of the replacement rate attributed to welfare claimants across the countries studied. The distribution of results varies across cases.

shows how the different deservingness criteria are evaluated in the four countries. The coefficients result from a multilevel model with random intercept for respondents in the Swiss, German, Swedish, and Danish surveys (to improve the readability of the figure, only the coefficients linked to the five deserving criteria are displayed).

Control and effort are the most relevant criteria for explaining perceptions of deservingness among respondents in all countries. Identity, reciprocity, and need have a relatively weaker influence on solidarity in the analysed cases. Contrary to expectations from the literature, there is no evidence that identity is a more relevant criterion in Conservative compared to Social Democratic welfare regimes. However, we did find that reciprocity holds slightly more weight in Conservative regimes. Swiss and German respondents assign higher unemployment replacement rates to welfare claimants who have contributed for eight years compared to those who have contributed for just one year. In Denmark and Sweden, longer records of contributions are either weak or statistically insignificant factors in determining solidarity. Overall, our findings confirm previous studies (Arts and Gelissen Citation2001), showing that the importance of deserving criteria is remarkably similar across different welfare regimes.

Given this conclusion, the subsequent analyses rely on the aggregated respondent sample of the four countries, with country-fixed effects, which substantially increase the power of our analysis. To compare how PRRP partisanship interacts with the deservingness criteria, we ran four regressions, adding an interaction between party choice and a selected vignette attribute (identity, effort, reciprocity, and control) at a time. These analyses are based on multilevel models with random intercepts for survey respondents and random slopes for selected vignette characteristics and country-fixed effects (Heisig and Schaeffer Citation2019). To simplify the interpretation of these interactions, we recoded every criterion into a binary variable: identity (0 = national; 1 = otherwise); effort (0 = claimant is not looking for a job; 1 = otherwise); need (0 = welfare claimant could live on savings for up to one month; 1 = welfare claimant could live on savings for more than one month); control (0 = welfare claimant lost their work due to COVID-19; 1 = otherwise); reciprocity (0 = welfare claimant paid taxes for one year; 1= otherwise).

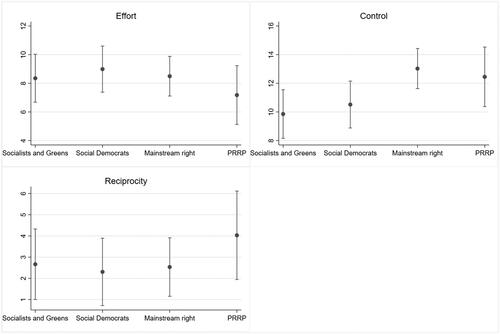

presents the effects of marginal changes in the binary variables operationalising the identity, need, effort, control, and reciprocity of welfare claimants on solidarity across different political affiliations (to improve readability, voters classified as ‘other’ were removed from the figure). All regression outputs are available in the supplementary material (Figures S6–S10). The analysis reveals that identity is not a significant determinant of solidarity for left-wing voters. Mainstream right-wing voters consider welfare claimants who are immigrants as relatively less deserving, attributing a 3.9% reduction in replacement rates. PRRP voters assign even greater importance to this criterion: being an immigrant claimant is associated with a 6.4% decrease in solidarity. However, the difference in the importance mainstream right-wing voters and PRRP voters attribute to the identity of the welfare claimant is not statistically significant. Therefore, we cannot accept H1, which states that identity is more important for the deservingness perception of PRRP voters than other partisans.

Figure 6. Predicted replacement rate attributed to the ‘least deserving’, ‘average deserving’, and ‘most deserving’ welfare claimant, by partisanship, with a 95% confidence interval.

Results show that need is only a relevant criterion for Social Democrat voters, as having more savings decreases the solidarity of this group by 2.3%. Results also indicate that lower need is associated with an increase in solidarity among PRRP voters by 0.5%. However, this difference is not statistically significant and, therefore, does not support the acceptance of H5, which states that welfare claimants’ greater needs have a lower impact on PRRP voters’ welfare solidarity. A higher effort to find work, operationalised as an active job search, has a strong marginal effect on welfare solidarity across all partisan groups, with a lower effect among voters of Socialists and Green parties (8.0%) and a higher effect among Social Democratic voters (8.7%). Therefore, we reject H3, which posits that PRRP voters exhibit more solidarity towards welfare claimants who make greater efforts to find a job.

Control also has a strong effect on solidarity, as individuals who become unemployed involuntarily (due to COVID-19) are considered more deserving, regardless of their party preference. shows that lower control increases the solidarity of mainstream right-wing parties and PRRPs by 12.9%, whereas this marginal effect is 10.1% and 10.3% for Socialist and Green parties, as well as Social Democratic parties, respectively. However, the analysis shows no statistically significant difference across partisanship, leading us to reject H4, which states that PRRP voters will see welfare claimants with more control as less deserving. Finally, reciprocity has a modest marginal effect on respondent solidarity across partisanship. PRRP voters show the highest level of solidarity towards welfare claimants with a longer contribution record, resulting in a marginal increase in the replacement rate by 2.5%. However, the difference across partisan groups is not statistically significant, leading us to reject H2, which posits that PRRP voters perceive welfare claimants with a longer contribution history as more deserving.

In order to examine the interactive effect between producerism and nativism across partisanship, we conducted three regressions, each including three-way interactions between party choice, identity criterion, and one component of producerism (control, effort, and reciprocity) at a time. illustrates the marginal effects of control, effort, and reciprocity, conditioned by the welfare claimant nationality. For regression outputs, refer to Figures A12, A13 and A14 in the Online Appendix. shows that, in comparison to other partisans, PRRP voters do not attribute a statistically higher importance to effort, control, and reciprocity when evaluating an immigrant welfare claimant, leading us to reject H2a, H3a, and H4a.

To assess the robustness of the results, we also test hypotheses H1, H2a, H3a, and H4a using an alternative specification of the identity variable, contrasting nationals and immigrants from a neighbouring country with immigrants from distant countries (0 = national and immigrants from a neighbouring country; 1 = otherwise). This operationalisation aims to capture potential effects of European Union (EU) legislation on shaping deservingness attitudes. Research has suggested that institutions play a crucial role in determining solidarity towards foreigners (Larsen Citation2020). Thus, the fact that EU member countries and bilateral agreements between Switzerland and the EU determine equal treatment among nationals and EU citizens’ welfare state entitlement may create a clear separation between these groups and immigrants from outside the EU. These analyses, available in the Online Appendix (Figure A15), show that PRRPs’ voters attribute significantly more importance to identity than all other partisans. Moreover, there is no significant difference between PRRP and other partisans’ evaluations of effort, reciprocity, and control, conditional on the fact that the welfare claimant was an immigrant from a non-EU country.

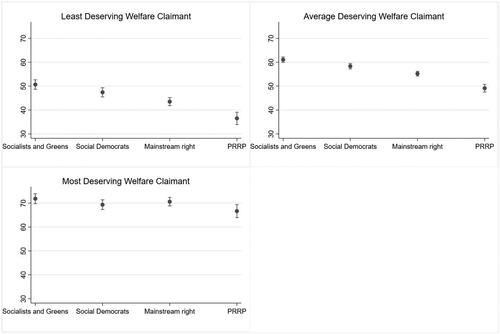

Finally, we compare the average welfare solidarity of PRRP voters and other partisans by contrasting the predicted unemployment replacement rates that these groups attribute to the ‘least’, the ‘average’ and the ‘highly deserving’ welfare claimant. Following the literature on PRRPs discussed above, the highly deserving individual is represented by a vignette that describes a national claimant who is actively looking for employment, has a longer contributory record, and became unemployed unintentionally. Conversely, the ‘least deserving’ claimant is an immigrant who is not looking for jobs, has a short contributory record, and is voluntarily unemployed. The ‘average deserving’ represents the claimant that scores mean values in those deservingness criteria. The replacement rates plotted in result from a regression on the entire sample with interactions between PRRP voting and the binary variables operationalising the identity, effort, reciprocity, and control of welfare claimants (for regression outputs, see Figure A11 in the Online Appendix).

It shows that PRRP voters are the least solidaristic among all partisan groups when it comes to the ‘least’ and ‘average-deserving’ claimants, attributing a replacement rate of 36.5% and 48.9% of the previous income, respectively. This result is statistically significant at a confidence level of 95%, leading us to accept H6 and H7, which state that PRRP voters would attribute lower replacement rates to the least and the average deserving welfare claimant than left-leaning voters. PRRP voters are also the least solidaristic towards welfare claimants they deemed highly deserving, assigning an average unemployment replacement rate of only 66.7% of the previous income. While this result is not statistically different for the expected replacement rate attributed by the Social Democrat voters (69.4%), it is statistically lower than the solidarity of Socialist and Green party voters, who, on average, assign a replacement rate of 71.9% of the previous income. Therefore, we cannot accept H8 or H8a.

Discussion and conclusion

A growing body of literature has suggested that PRRPs have developed a distinctive welfare state ideology. This ideology combines the defense of a generous welfare state for ‘deserving’ members of the community with restrictive approach to ‘undeserving’ access to social benefits (Chueri Citation2022; Enggist and Pinggera Citation2022; Fischer and Giuliani Citation2023; Otjes Citation2019). This literature has furthermore suggested that distinguishing ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ is a function of nativist and producerist appeals (Abts et al. Citation2021; Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2016, Citation2018; Ivaldi and Mazzoleni Citation2019; Otjes et al. Citation2018; Rathgeb Citation2021). This implies that neither immigrants nor individuals failing to comply with the social norm of being ‘hard-working’ and contributing to society should benefit from the same social protection as ‘deserving’ nationals.

However, it has remained unclear whether the parties’ welfare preferences mirror those of their voters. Although studies have shown that economic concerns are associated with PRRPs voting (Dehdari Citation2022; Gallego and Kurer, Citation2022; Gidron and Hall Citation2020), research has not found a unified pro-welfare position among PRRP voters (Busemeyer et al. Citation2022; Ivarsflaten Citation2005; Loxbo Citation2022). Instead, those voters prefer traditional forms of social consumption with moderate generosity (Busemeyer et al. Citation2022).

The entanglement of distributive and cultural preferences underscores the importance of studying the determinants of PRRP voters’ perception of deservingness and how it is associated with solidarity. Thus, for advancing the understanding of PRRP voters’ welfare preferences, we have conducted a vignette survey experiment with a deservingness framework to analyse how voters’ welfare generosity is associated with perceptions of the deservingness of the welfare benefit claimant.

Our analysis reveals that, in line with PRRPs’ welfare positions, adherence to the social norm of being hardworking and a co-national are relevant aspects of PRRP voters’ deservingness perceptions, as this group attaches great importance to the identity, effort, and control of unemployment benefit claimants. However, contrary to previous research findings, our study reveals that PRRP partisans do not adhere to a distinctly producerist approach to welfare distribution, as these groups do not differ from voters of other parties with regard to the importance they attribute to welfare claimants’ efforts to find a job, the control that claimants have over their situation, or their previous contributions. The belief that the generosity of unemployment benefits should be conditional on reciprocal obligations and on compliance with social norms of being hardworking exists across party lines, and PRRP voters do not particularly penalise welfare claimants who deviate from those norms. This result holds true when conditioned to welfare claimants’ nationality, which indicates that PRRP voters do also not attribute relative higher importance to control, effort and reciprocity when evaluating an immigrant welfare claimant.

The most distinctive aspect of PRRP voters’ perception of deservingness is the importance that they attach to identity. These voters display the lowest level of solidarity towards immigrant welfare claimants; however, this difference is not statistically significant when compared to voters of mainstream right-wing parties. While this result confirms previous findings that PRRPs partisans hold nativist welfare views, it challenges the assumption that identity is an omnipresent component of how people perceive the deservingness of welfare claimants, suggesting that it is only relevant for right-wing voters. This result is consistent with the findings of Reeskens and van der Meer (Citation2021) in a Dutch sample.

Finally, our findings confirm that solidarity levels are more strongly associated with fulfilling deservingness criteria for PRRP voters than for other voters. PRRP voters attribute less generous benefits to the ‘least’ and ‘average deserving’ welfare claimant compared to other partisan groups. At the same time, PRRP voters also assign the lowest replacement rate for welfare claimants that they deem ‘deserving’, although this result is only statically significant compared to voters of Socialists and Greens parties.

In conclusion, we find no support for the claim that PRRP voters favour a generous welfare state for the ‘deserving’ community members. Our research indicates that the tension between PRRP voters’ economic anxieties and the fear that undeserving members of the community will profit from collective schemes is not fully resolved by selective generosity, as they continue to be relatively critical of generous welfare benefits. This result also implies that PRRPs face a lesser trade-off in participating in governments with mainstream right-wing parties and helps explain why participating in retrenchment initiatives had a limited impact on PRRPs’ electoral outcomes. Further research is however needed to verify whether this conclusion holds beyond unemployment benefits. In particular, studies have shown that PRRPs protect pensions to the detriment of unemployment benefits (Afonso and Papadopoulos Citation2015; Chueri Citation2021).

Some comments must be made regarding our results. Beside internal validity, studies have shown that survey experiments are also powerful instruments for predicting political behaviour (Hainmueller et al. Citation2015). In addition, it is important to note that the survey data were collected during the summer and autumn of 2021, thus we cannot rule out that the enduring societal impact of the pandemic to have affected respondents’ economic concerns. We believe, however, that our conclusions are valid beyond this period. The relatively average higher economic insecurity of PRRP voters (see Busemeyer et al. Citation2022; Loxbo Citation2022) would be associated with more, rather than less, demand for protection during crises. Additionally, following previous studies that found that the COVID-19 crisis did not relax voters’ authoritarian approach to welfare distribution (Blanchet and Landry Citation2021), we have no reason to believe that context affected the importance of deservingness criteria for our respondents. Finally, it is important to highlight that differences between PRRPs and other partisans may lie beyond their perceptions of solidarity and deservingness. For instance, producerist attitudes towards welfare distribution may manifest as support for more stringent monitoring and supervision of welfare claimants or higher sanctions for ‘welfare fraud.’ We leave it to future research to further investigate those differences.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.4 MB)Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the panel Welfare (Chauvinism) and the Radical Right at the 28th International Conference of Europeanists, and, in particular, Eloisa Harris, Leonce Röth, Matthias Enggist and Philip Rathgeb for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Juliana Chueri

Juliana Chueri is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Politics at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Her research interests include the politics of welfare transformations, particularly examining how recent developments, such as the rise of populist radical right parties and the current wave of technological innovation, have impacted existing redistributive arrangements in Western Europe. [[email protected]]

Mia K. Gandenberger

Mia K. Gandenberger is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies of the University of Neuchâtel and associated to the nccr on the move. Her research interests include social and economic inequalities, social policy, and public opinion towards migrant access to rights in multi-ethnic societies. [[email protected]]

Alyssa M. Taylor

Alyssa M. Taylor is a Doctoral Researcher at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP). Her research is concerned with migrant integration and political participation, enfranchisement policy, and public opinion towards topics of immigrant integration. [[email protected]]

Carlo M. Knotz

Carlo M. Knotz is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Stavanger. His research is concerned with the effects of immigration and technological change on political attitudes and preferences, and with the politics of labour market activation policies. [[email protected]]

Flavia Fossati

Flavia Fossati is Assistant Professor for Inequality and Integration Studies at the University of Lausanne and at the Centre LIVES. Her research includes: labour market and education policies, discrimination, immigration, and electoral behaviour. Her research has been published in Socio-Economic Review, amongst others. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 The larger German sample is due to another experiment that was run as part of the same survey, which we investigate elsewhere (Knotz et al. Citation2024). We excluded from the analysis vignette evaluations that were conducted unreasonably fast (less than 5 seconds) or took too long (more than 180 s).

2 For the Swiss survey, an additional quota for the French- or German-speaking regions was included.

3 Our design achieves score 94,79, which exceeds the 90 design scores recommended by the literature.

4 Vignettes designed for the Swiss sample were available both in French and in German.

5 We only consider respondents who declared they voted in the last election. The average turnout of our sample is 80%: 60.3% in Switzerland, 83.2% in Germany, 87% in Sweden, and 86.7% in Denmark, which mirrors national trends.

References

- Abts, Koen, Emmanuel Dalle Mulle, Stijn van Kessel, and Elie Michel (2021). ‘The Welfare Agenda of the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe: Combining Welfare Chauvinism, Producerism and Populism’, Swiss Political Science Review, 27:1, 21–40.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Silja Häusermann, Reto Mitteregger, Nadja Mosimann, and Marcus Wagner (2021). ‘Old Left, New Left, Centrist or Left Nationalist? Determinants of Support for Different Social Democratic Programmatic Strategies’, Unpublished Manuscript.

- Achterberg, Peter, Romke van der Veen, and Judith Raven (2014). ‘The Ideological Roots of the Support for Welfare State Reform: Support for Distributive and Commodifying Reform in The Netherlands’, International Journal of Social Welfare, 23:2, 215–26.

- Afonso, Alexandre (2015). ‘Choosing Whom to Betray: Populist Right-Wing Parties, Welfare State Reforms and the Trade-off between Office and Votes’, European Political Science Review, 7:2, 271–92.

- Afonso, Alexandre, and Yannis Papadopoulos (2015). ‘How the Populist Radical Right Transformed Swiss Welfare Politics: From Compromises to Polarization’, Swiss Political Science Review, 21:4, 617–35.

- Afonso, Alexandre, and Line Rennwald (2018). ‘Social Class and the Changing Welfare State Agenda of Radical Right Parties in Europe’, in P. Philip Manow, and B. Palier (eds.), Welfare Democracies and Party Politics: Explaining Electoral Dynamics in Times of Changing Welfare Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 171–94.

- Andersen, Jørgen Goul, and Tor Bjørklund (1990). ‘Structural Changes and New Cleavages: The Progress Parties in Denmark and Norway’, Acta Sociologica, 33:3, 195–217.

- Arts, Wil, and John Gelissen (2001). ‘Welfare States, Solidarity and Justice Principles: Does the Type Really Matter?’, Acta Sociologica, 44:4, 283–99.

- Arzheimer, Kai (2012). ‘Working Class Parties 2.0? Competition between Centre Left and Extreme Righparties’, in Jens Rydgren (ed.), Class Politics and the Radical Right, London and New York: Routledge, 75–90.

- Attewell, David (2021). ‘Deservingness Perceptions, Welfare State Support and Vote Choice in Western Europe’, West European Politics, 44:3, 611–34.

- Auspurg, Karin, and Thomas Hinz (2015). ‘Multifactorial Experiments in Surveys: conjoint Analysis, Choice Experiments, and Factorial Surveys’, in Keuschnigg Mark and Tobias Wolbring (eds.), Experimente in Den Sozialwissenschaften. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos, 291–315.

- Auspurg, Katrin, Thomas Hinz, Stefan Liebig, and Carsten Sauer (2014). “The Factorial Survey as a Method for Measuring Sensitive Issues”, in Uwe Engel, Ben Jann, Peter Lynn, Annette Scherpenzeel, and Patrick Sturgis (eds.), Improving Survey Methods: Lessons from Recent Research. New York: Routledge, 137–49.

- Betz, Hans-Gerog (2019). ‘Facets of Nativism: A Heuristic Exploration’, Patterns of Prejudice, 53:2, 111–35.

- Blanchet, Alexandre, and Normand Landry (2021). ‘Authoritarianism and Attitudes toward Welfare Recipients under Covid-19 Shock’, Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 66088.

- Bornschier, Simon, and Hanspeter Kriesi (2013). ‘The Populist Right, the Working Class and the Changing Face of Class Politics’, in J. Rydgren (ed.), Class Politics and the Radical Right. New York: Routledge, 10–28.

- Busemeyer, Marius R., Philip Rathgeb, and Alexander H. Sahm (2022). ‘Authoritarian Values and the Welfare State: The Social Policy Preferences of Radical Right Voters’, West European Politics, 45:1, 77–101.

- Careja, Romana, Christian Elmelund-Præstekær, Klitgaard, Michal Baggesen, and Erick G. Larsen (2016). ‘Direct and Indirect Welfare Chauvinism as Party Strategies: An Analysis of the Danish People’s Party’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 39:4, 435–57.

- Careja, Romana, and Eloisa Harris (2022). ‘Thirty Years of Welfare Chauvinism Research: Findings and Challenges’, Journal of European Social Policy, 32:2, 212–24.

- Chueri, Juliana (2021). ‘Social Policy Outcomes of Government Participation by Radical Right Parties’, Party Politics, 27:6, 1092–104.

- Chueri, Juliana (2022). ‘An Emerging Populist Welfare Paradigm? How Populist Radical Right-Wing Parties Are Reshaping the Welfare State’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 45:4, 383–409.

- Dehdari, Sirus H. (2022). ‘Economic Distress and Support for Radical Right Parties—Evidence from Sweden’, Comparative Political Studies, 55:2, 191–221.

- de Koster, Willem, Peter Achterberg, and Jeroen Van der Waal (2013). ‘The New Right and the Welfare State: The Electoral Relevance of Welfare Chauvinism and Welfare Populism in The Netherlands’, International Political Science Review, 34:1, 3–20.

- de Lange, Sarah L. (2007). ‘A New Winning Formula?’, Party Politics, 13:4, 411–35.

- Dülmer, Hermann (2016). ‘The Factorial Survey: Design Selection and Its Impact on Reliability and Internal Validity’, Sociological Methods & Research, 45:2, 304–47.

- Enggist, Matthias, and Michael Pinggera (2022). ‘Radical Right Parties and Their Welfare State Stances–Not So Blurry after All?’, West European Politics, 45:1, 102–28.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2016). ‘A Welfare State for Whom? A Group-Based Account of the Austrian Freedom Party’s Social Policy Profile’, Swiss Political Science Review, 22:3, 409–27.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2018). ‘Welfare Chauvinism in Populist Radical Right Platforms: The Role of Redistributive Justice Principles’, Social Policy & Administration, 52:1, 293–314.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, Laurenz (2020). ‘The FPÖ’s Welfare Chauvinism’, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 49:1, 1–13.

- Fischer, Torber, and Giulian A. Giuliani (2023). ‘The Makers Get It All? The Coalitional Welfare Politics of Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. The Case Studies of Austria and Italy’, European Political Science Review, 15:2, 214–32.

- Gallego, Aina, and Thomas Kurer (2022). ‘Automation, Digitalization, and Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace: implications for Political Behavior’, Annual Review of Political Science, 25:1, 463–84.

- Gandenberger, Mia K., Carlo M. Knotz, Flavia Fossati, and Giuliano Bonoli (2022). ‘Conditional Solidarity-Attitudes towards Support for Others during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic’, Journal of Social Policy, 52:4, 943–61.

- Gidron, Noam (2022). ‘Many Ways to Be Right: Cross-Pressured Voters in Western Europe’, British Journal of Political Science, 52:1, 146–61.

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall (2017). ‘The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right’, The British Journal of Sociology, 68:S1, S57–S84.

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall (2020). ‘Populism as a Problem of Social Integration’, Comparative Political Studies, 53:7, 1027–59.

- Gingrich, Jane, and Silja Häusermann (2015). ‘The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and Consequences for the Welfare State’, Journal of European Social Policy, 25:1, 50–75.

- Goubin, Silke, and Marc Hooghe (2021). ‘Do Welfare Concerns Drive Electoral Support for the Populist Radical Right? An Exploratory Analysis’, Acta Politica, 57:2, 431–53.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Dominik Hangartner, and Teppei Yamamoto (2015). ‘Validating Vignette and Conjoint Survey Experiments against Real-World Behavior’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112:8, 2395–400.

- Halikiopoulou, Daphne, and Tim Vlandas (2019). ‘What is New and What is Nationalist about Europe’s New Nationalism? Explaining the Rise of the Far Right in Europe’, Nations and Nationalism, 25:2, 409–34.

- Häusermann, Silja, Michael Pinggera, Macarana Ares, and Matthias Enggist (2022). ‘Class and Social Policy in the Knowledge Economy’, European Journal of Political Research, 61:2, 462–84.

- Häusermann, Silja, Tabea Palmtag, Delia Zollinger, Tarik Abou-Chadi, Stefanie Walter, and Sarah Berkinshaw (2023). ‘Economic Foundations of Sociocultural Politics: How New Left and Radical Right Voters Think about Inequality’, URPP Equality of Opportunity Discussion Paper Series 33.

- Heisig, Jan Paul, and Merlin Schaeffer (2019). ‘Why You Should Always Include a Random Slope for the Lower-Level Variable Involved in a Cross-Level Interaction’, European Sociological Review, 35:2, 258–79.

- Heuer, Jan-Ocko, and Katharina Zimmermann (2020). ‘Unravelling Deservingness: Which Criteria Do People Use to Judge the Relative Deservingness of Welfare Target Groups? A Vignette-Based Focus Group Study’, Journal of European Social Policy, 30:4, 389–403.

- Hjorth, Frederik (2016). ‘Who Benefits? Welfare Chauvinism and National Stereotypes’, European Union Politics, 17:1, 3–24.

- Ivaldi, Gilles, and Oscar Mazzoleni (2019). ‘Economic Populism and Producerism: European Right-Wing Populist Parties in a Transatlantic Perspective’, Populism, 2:1, 1–28.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2005). ‘The Vulnerable Populist Right Parties: No Economic Realignment Fuelling Their Electoral Success’, European Journal of Political Research, 44:3, 465–92.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth (2008). ‘What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-Examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:1, 3–23.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, and Anthony J. McGann (1997). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Knotz, Carlo M., Mia K. Gandenberger, Flavia Fossati, and Giuliano Bonoli (2022). ‘A Recast Framework for Welfare Deservingness Perceptions’, Social Indicators Research, 159:3, 927–43.

- Knotz, Carlo M., Alyssa M. Taylor, Mia K. Gandenberger, and Juliana Chueri (2024). ‘What Drives Opposition to Social Rights for Immigrants? Clarifying the Role of Psychological Predispositions’, Political Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217241228456

- Kootstra, Anouk (2016). ‘Deserving and Undeserving Welfare Claimants in Britain and The Netherlands: Examining the Role of Ethnicity and Migration Status Using a Vignette Experiment’, European Sociological Review, 32:3, 325–38.

- Kramer, Dion, Jessica Sampson Thierry, and Franca Van Hooren (2018). ‘Responding to Free Movement: Quarantining Mobile Union Citizens in European Welfare States’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25:10, 1501–21.

- Krause, Werner, and Heiko Giebler (2020). ‘Shifting Welfare Policy Positions: The Impact of Radical Right Populist Party Success beyond Migration Politics’, Representation, 56:3, 331–48.

- Kurella, Anna-Sophie, and Jan Rosset (2017). ‘Blind Spots in the Party System: Spatial Voting and Issue Salience If Voters Face Scarce Choices’, Electoral Studies, 49, 1–16.

- Laenen, Tijs, Federica Rossetti, and Win van Oorschot (2019). ‘Why Deservingness Theory Needs Qualitative Research: Comparing Focus Group Discussions on Social Welfare in Three Welfare Regimes’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 60:3, 190–216.

- Larsen, A., Christian (2008). ‘The Institutional Logic of Welfare Attitudes: How Welfare Regimes Influence Public Support’, Comparative Political Studies, 41:2, 145–68.

- Larsen, A. Christian (2020). ‘The Institutional Logic of Giving Migrants Access to Social Benefits and Services’, Journal of European Social Policy, 30:1, 48–62.

- Lefkofridi, Zoe, and Elie Michel (2014). ‘The Electoral Politics of Solidarity. The Welfare State Agendas of Radical Right’, in The Strains of Commitment: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 233–67.

- Loxbo, Karl (2022). ‘The Varying Logics for Supporting Populist Right-Wing Welfare Politics in West European Welfare Regimes’, European Political Science Review, 14:2, 171–87.

- Marks, Gary, Liesbet Hooghe, Moira Nelson, and Erica Edwards (2006). ‘Party Competition and European Integration in the East and West: Different Structure, Same Causality’, Comparative Political Studies, 39:2, 155–75.

- Mewes, Jan, and Mau Steffen (2012). ‘Unraveling Working-Class Welfare Chauvinism’, in Svallfors S (ed.), Contested Welfare States: Welfare Attitudes in Europe and Beyond’. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 119–57.

- Mudde, Cas (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas (2016). ‘The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy’, in Cas Mudde (ed.), The Populist Radical Right. London: Routledge, 442–456.

- Oesch, Daniel (2008). ‘Explaining Workers’ Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland’, International Political Science Review, 29:3, 349–73.

- Otjes, Simon, Gilles Ivaldi, Anders R. Jupskås, and Oscar Mazzoleni (2018). ‘It’s Not Economic Interventionism, Stupid! Reassessing the Political Economy of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties’, Swiss Political Science Review, 24:3, 270–90.

- Otjes, Simon (2019). ‘What Is Left of the Radical Right? The Economic Agenda of the Dutch Freedom Party 2006-2017’, Politics of the Low Countries, 1:2, 81–102.

- Petersen, Michael, B., Rune Slothuus, Rune Stubager, and Lise Togeby (2011). ‘Deservingness versus Values in Public Opinion on Welfare: The Automaticity of the Deservingness Heuristic’, European Journal of Political Research, 50:1, 24–52.

- Petersen, Michael B. (2012). ‘Social Welfare as Small-Scale Help: Evolutionary Psychology and the Deservingness Heuristic’, American Journal of Political Science, 56:1, 1–16.

- Rathgeb, Philip (2021). ‘Makers against Takers: The Socio-Economic Ideology and Policy of the Austrian Freedom Party’, West European Politics, 44:3, 635–60.

- Reeskens, Tim, and Wim Van Oorschot (2012). ‘Disentangling the “New Liberal Dilemma”: On the Relation between General Welfare Redistribution Preferences and Welfare Chauvinism’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 53:2, 120–39.

- Reeskens, Tim, and Tom van der Meer (2017). ‘The Relative Importance of Welfare Deservingness Criteria’, in Wim van Oorschot, Femke Roosma, Bart Meuleman, and Tim Reeskens (eds.), The Social Legitimacy of Targeted Welfare. Northamptom: Edward Elgar Publishing, 55–70.

- Reeskens, Tim, and Tom van der Meer (2019). ‘The Inevitable Deservingness Gap: A Study into the Insurmountable Immigrant Penalty in Perceived Welfare Deservingness’, Journal of European Social Policy, 29:2, 166–81.

- Reeskens, Tim, and Tom van der Meer (2021). ‘Welfare Chauvinism across the Political Spectrum’, in Tijs Laenen, Bart Meuleman, Adeline Otto, Femke Roosma and Wim Van Lancker (eds.), Leading Social Policy Analysis from the Front: Essays in Honour of Wim Van Oorschot. Leuven: KU Leuven, 298–300.

- Röth, Leonce, Alexandre Afonso, and Dennis C. Spies (2018). ‘The Impact of Populist Radical Right Parties on Socio-Economic Policies’, European Political Science Review, 10:3, 325–50.

- Rovny, Jan (2013). ‘Where Do Radical Right Parties Stand? Position Blurring in Multidimensional Competition’, European Political Science Review, 5:1, 1–26.

- Rovny, Jan, and Jonathan Polk (2020). ‘Still Blurry? Economic Salience, Position and Voting for Radical Right Parties in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 59:2, 248–68.

- Rydgren, Jens (2004). ‘Explaining the Emergence of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties: The Case of Denmark’, West European Politics, 27:3, 474–502.

- Taylor-Gooby, Peter, Bjørn Hvinden, Steffen Mau, Benjamin Leruth, Mi Ah Schoyen, and Adrienn Gyory (2019). ‘Moral Economies of the Welfare State: A Qualitative Comparative Study’, Acta Sociologica, 62:2, 119–34.

- van der Waal, Jeroen, Peter Achterberg, Dick Houtman, Willem de Koster, and Katerina Manevska (2010). ‘‘Some Are More Equal than Others’: Economic Egalitarianism and Welfare Chauvinism in The Netherlands’, Journal of European Social Policy, 20:4, 350–63.

- van der Waal, Jeroen, Willem de Koster, and Wim van Oorschot (2013). ‘Three Worlds of Welfare Chauvinism? How Welfare Regimes Affect Support for Distributing Welfare to Immigrants in Europe’, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 15:2, 164–81.

- Van Kersbergen, Kees, and André Krouwel (2008). ‘A Double-Edged Sword! the Dutch Centre-Right and the ‘Foreigners Issue’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15:3, 398–414.

- van Oorschot, Wim (2000). ‘Who Should Get What, and Why? On Deservingness Criteria and the Conditionality of Solidarity among the Public’, Policy & Politics, 28:1, 33–48.

- van Oorschot, Wim (2006). ‘Making the Difference in Social Europe: Deservingness Perceptions among Citizens of European Welfare States’, Journal of European Social Policy, 16:1, 23–42.

- van Oorschot, Wim, Roosma, Femke, Meuleman, Bart, and Tim Reeskens, eds. (2017). The Social Legitimacy of Targeted Welfare: Attitudes to Welfare Deservingness. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Zaslove, Andrej (2009). ‘The Populist Radical Right: Ideology, Party Families and Core Principles’, Political Studies Review, 7:3, 309–18.