Abstract

When parties cooperate, they are perceived as closer together in an ideological space than when they compete. This mechanism has only been tested at the national level and researchers have disregarded the complex interaction between parties competing and cooperating at various levels of a polity. This article argues that complex multi-level systems have an influence on the voters’ perceptions, especially for coalition parties. More specifically, the hypothesis is that voters perceive those national parties that are in government in their Bundesland as closer together on a left-right scale, even though they are not members of the same coalition at the national level. The hypothesis is tested by relying on GLES data from 2009–2021. National government participation and political sophistication are also taken into account as moderating variables. The results have important implications for understanding party perceptions and the effect of regional government participation in multi-level systems.

At least until the 2021 election in Germany, government formation at the national level was rather predictable and not particularly exciting: between 2005 and 2021, Germany was governed by a grand coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD for 12 years with a 4-year break between 2009 and 2013 where a government was formed between the CDU/CSU and the FDP. However, the picture is quite different when looking at the regional level. For instance, there are a number of Bundesländer in which the CDU and the Greens formed a coalition. In Baden-Württemberg, the Green party has even lead such a coalition as the senior party since 2016. Furthermore, the Left Party, a party that is basically excluded from government formation at the national level, is not only a member of four regional coalition governments (Bremen, Berlin, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, and Thuringia) but is also leading one of them as the senior party (Thuringia). Hence, government formation at the regional level is extremely diverse and varies over time but also between states.

Which effect does this variety of regional coalition compositions have on the coalition signals voters receive? Previous research shows that the electorate uses widely available and easily accessible cues in order to form an opinion about the ideological position of political parties. Thus, voters rely on their knowledge about coalition memberships to deduct party positions, i.e. coalition heuristics, (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013) instead of engaging themselves with more cognitive demanding sources such as party manifestos (Adams et al. Citation2011). Consequentially, parties that govern together in a coalition are commonly perceived as being more closely located to each other than parties that are not in coalitions (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013; Spoon and Klüver Citation2017). Moreover, it seems that voters project the senior party positions on the junior partner in a coalition - not the other way around (Adams et al. Citation2016; Bernardi and Adams Citation2019; Fortunato and Adams Citation2015).

In this article we argue that previous studies have overlooked an important cue given in multi-level systems: the membership in regional coalitions. Regional governments are not only more diverse, but they also have a strong influence on state and national policies. Germany has one of the strongest federal systems with powerful regional parliaments and governments. Due to the strong competences of the regional level, the regional government composition should also work as an additional cue for citizens when drawing conclusions about party positions. We propose that this cue is more important for the more politically sophisticated voters since they are more likely to be knowledgeable of and interested in the regional government composition.

Existing research on regional politics has mainly focused on party competition, government formation as well as governance. Traditionally, voting at the regional level has been seen as second-order, meaning that if citizens take part in regional elections then they will mainly base their voting decision on national considerations (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980). Previous literature has also analysed the process of government formation (see e.g. Däubler and Debus Citation2009; Falcó-Gimeno and Verge Citation2013; Shikano and Linhart Citation2010), governance in regional coalitions (Krauss et al. Citation2021) as well as the termination of coalition governments at the regional level (Martínez-Cantó and Bergmann Citation2019). So far, though, the influence of a complex multi-level system on the voters’ perception of parties has been neglected. This is surprising considering the fact that citizens, living in countries with complex multi-level systems, are often exposed to different coalition governments simultaneously.

This article aims to fill this gap by hypothesising that voters will perceive parties as closer together on a left-right scale if they form a coalition government in the voters’ state. We rely on pre-electoral survey data provided by the German Longitudinal Election Study (2009–2021) (GLES) to test our hypotheses. We estimate multilevel regression analyses and show that parties governing together in a Bundesland are indeed perceived as more similar to each other. Moreover, the findings support our argument that politically more sophisticated voters rely more strongly on regional coalition signals.

Our findings highlight significant, albeit subtle, implications for party competition in federalised parliamentary systems. We measure the effect of regional government signals at a time when they are least likely to matter: during national election campaigns. Our findings highlight that regional coalition signals have significant effects on voters’ perceptions of parties. While they are generally small in magnitude, these effects are far from negligible for the most politically sophisticated voters. This is especially important for countries like Germany where the national electoral system is structured based on state party lists. Moreover, previous research has argued that the regional level is relevant for the national level in terms of testing coalition constellations and their acceptance in the electorate (see e.g. Bräuninger et al. Citation2020; Gross and Niendorf Citation2017). Therefore, we conclude that voters perceive the coalition signals at the regional level and apply them accordingly. However, the magnitude of the effect makes it unlikely that these changes in perception lead to electoral losses and therefore allows parties to use the regional level as experimental ground for new coalition constellations. In general, parties do not have to worry too much about the coalition signals omitted at the regional level during national campaigns.

The article is structured as follows. First, we present our theoretical argument about the influence of regional government participation on voters’ perception. Second, we describe the dataset we rely on and how we operationalise our dependent and independent variables. The third section in this article includes the results of our multilevel analysis. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of our results and the implications of our findings.

Theoretical framework

Party perceptions and coalition heuristics

Political parties are the main actors in the political process in parliamentary democracies since they form the link between the electorate and the decision-making institutions. According to the traditional model of proximity voting, voters evaluate parties based on their policy positions and vote for the party closest to their own preferences (Downs Citation1957). Parties aggregate voter preferences and have clear incentives to position themselves in the ideological space in order to attract votes and in response influence policy outputs. Consequentially, voters must be able to clearly locate the political parties in space in order to make a rational voting decision and to make representative democracy work.

However, research suggests that the electorate struggles to locate party positions in the policy space (e.g. Adams et al. Citation2011; Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013; Spoon and Klüver Citation2017). While parties generally respond to ideological shifts in the electorate by changing their position accordingly (Klüver and Spoon Citation2016), voters seem to be unaware of these positional shifts in objectively measurable documents such as party manifestos (Adams et al. Citation2011). One potential explanation could be that voters rather react to the larger environment and the behaviour of a party (elite) instead of their written policy documents. Still, over time not even expert assessments can explain the perceptions voters have about party position movements (Adams et al. Citation2016), or at least can do so only weakly (Adams et al. Citation2014). This is rather surprising due to the fact that experts are likely to include party behaviour into their judgements.

How do voters acquire the information to place parties in the ideological space? It has been argued that voters rely on so-called heuristics in order to locate party positions. Using such a heuristic is a rational strategy to derive approximate information which allows the voter to form a reasonable opinion about a party’s position using a cognitive short-cut (Fortunato and Adams Citation2015; Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013). In multiparty systems, the coalition heuristic is considered to be the most important one. Voters tend to draw conclusions about ideological positions of parties based on coalition membership (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013). Hence, coalition parties are perceived as ideologically closer to one another than other measures such as party manifestos would suggest and how voters would perceive the parties if they would not govern together (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013; Hjermitslev Citation2023; Spoon and Klüver Citation2017).

Using cabinet membership as a cue for party positioning is an easy and accessible piece of information for voters. There are two mechanisms that can explain why coalition heuristics work at least to some extent (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013). Firstly, previous studies show that ideologically close parties are more likely to form coalition governments in the first place, so-called connected coalitions (Axelrod Citation1970; de Swaan Citation1973; Martin and Stevenson Citation2001; Warwick Citation1996). Secondly, parties that enter formal coalitions are bound in their behaviour by coalition unity if they want to avoid that inter-party conflict is leading to cabinet breakdown (Lupia and Strøm Citation1995; Müller and Strøm Citation2000; Warwick Citation1994). Thus, coalition partners are pressured into policy compromise (Ganghof and Bräuninger Citation2006).

Due to the blurred responsibilities in coalition governments, voters are not able to correctly distinguish the advertised positions of the parties in cabinet (Dahlberg Citation2013). This is especially true for members of the electorate who are less interested in politics and less educated and who are therefore more likely to only make use of coalition heuristics when assessing party positions (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013). In contrast, the misperception of cabinet party positions is lower if the objective ideological distance is higher (Spoon and Klüver Citation2017).

Moreover, coalition heuristics do not affect all parties to the same extent. In fact, voters tend to associate the junior partner in a coalition with the senior party (Fortunato and Adams Citation2015), not the other way around. This means that especially smaller coalition parties have problems to communicate their distinct policy profile as different from the senior party. This fact could potentially explain why it is most commonly the junior coalition partner who experiences negative electoral consequences in the following elections, not the senior party (Hjermitslev Citation2020; Klüver and Spoon Citation2020). As a consequence, coalition parties try to demonstrate their distinct policy profiles by emphasising different policy issues they care about, especially at the end of the legislative cycle (Sagarzazu and Klüver Citation2017).

Coalition signals under multi-level government

In this article, we add to these considerations by incorporating the perceptions voters form based on regional level politics. Especially in decentralised, federal countries, it is difficult for voters to assign responsibility to different levels of governance. For instance, in situations where the regional and national level have shared competences, a minimum amount of coordination between the levels is needed (Thorlakson Citation2017). This might make assigning responsibility even more difficult for the electorate (Rodden and Wibbels Citation2011). Additionally, previous research has shown that regional and even local parties include issues that are being handled at the national level in their manifestos (Cabeza et al. Citation2017; Gross and Jankowski Citation2020). Even for coalition agreements at the local and regional level this pattern holds (Gross and Krauss Citation2021).

We argue that this power sharing also has consequences for the way in which voters perceive the parties. This is mainly due to the fact that strong competences for the regions also mean that the day-to-day life of the electorate is importantly influenced not only by the national but also by the regional (and potentially also the local) level. Germany ranks exceptionally high on the Regional Authority Index with a score of 37.67, especially because of high self-rule powers of the Bundesländer (25.67). Self-rule powers are an indicator for the power that the states have within their own region (Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021). Additionally, turnout for regional elections is comparatively high even though they are considered to be second-order elections (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980). In the last elections in the 16 German states, the average turnout was at around 65% which is only around 10% less than the turnout at the last national election in Germany in 2021.Footnote1 Hence, regional elections and regional governments matter at lot in German politics, and the country thus represents a most-likely-case for finding a strong effect of regional coalition heuristics on party perceptions.

Accordingly, we posit that we can translate the mechanism proposed by Fortunato and Stevenson (Citation2013) to the regional level: cabinet membership is a cheap and widely available piece of information. Previous analyses have shown that people know which parties are in government (see e.g. Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013) and there is reason to believe that, at least in countries with a strong federalist system like Germany, people know which parties are in government at the regional level. Accordingly, we hypothesise the following:

Hypothesis 1: Parties that govern together at the regional level will be perceived as more ideologically similar on the national level.

Furthermore, Falcó-Gimeno and Fernandez-Vazquez (Citation2020) demonstrated that in order for a coalition formation to impact voter beliefs, it must be at odds with the voters’ prior expectations. Specifically, if a party joins the coalition that the voters already identified as the most congruent choice, then the voters’ beliefs are simply confirmed and nothing changes. In other words, there is a saturation effect, which prevents voters from perceiving parties as converging twice. If the regional governments match the expectations created by the national coalition formation, there is no reason for updating perceptions.Footnote2 Accordingly, our second hypothesis reads:

Hypothesis 2: The effect of regional government participation should be strongest for parties that do not govern together at the national level.

Although we argue that the mechanism can be applied at the regional level, we acknowledge that there are important differences between the national and the regional level. While the second coalition signal, and therefore the regional coalition heuristic, remains relatively cheap and widely accessible in federal systems due to the highly regionalised news and media landscapes (Harnischmacher Citation2015; Wehden and Stoltenberg Citation2019), we posit that the awareness of and knowledge about cabinet membership at the regional government level is not as widespread as it is at the national level. We therefore suggest that there is an important interaction between political sophistication and regional government participation. In contrast to Fortunato and Stevenson (Citation2013), we posit that this interaction effect is positive in the sense that people with higher political sophistication should also be more likely to know who is in government at the regional level and the coalition heuristic should therefore be strongest amongst those individuals. Fortunato and Stevenson (Citation2013) base their argument on the differentiation of coalition partners in legislative debates and the media and that more interested voters are more likely to receive these messages. While this can certainly hold for the national context, it is quite unlikely that the same mechanism is also at work for coalition heuristics at the regional level.

Instead, we take one step back and argue that for the awareness of regional government participation, receiving the coalition signal in the first place is dependent on political sophistication. The level of political sophistication is strongly and positively associated with news consumption (Stromback et al. Citation2013) and, as we argue above, news consumption in federal systems is commonly highly regionalised with radio stations and newspapers having strong regional foci in their reporting. Moreover, citizens with higher levels of political education and knowledge are also more likely to process the news and form opinions based on the received cues. Following this rationale, we argue that higher levels of political sophistication lead to more awareness of regional government compositions and thus to the reception of more than one coalition signal. Consequentially, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 3: The effect of regional government participation should be strongest for individuals with higher levels of political sophistication.

Research design

Case selection

In order to test our hypotheses, we rely on data from Germany. Germany is an excellent case due to its institutional setup. For instance, it has rather low values for both ‘institutional clarity’ as well as ‘government clarity’, especially if compared to other states in Europe (Hobolt et al. Citation2013). This is due to the fact that both the national and the regional level have exclusive competences with regard to legislation, but they also share competences in some policy fields. As previously mentioned, Germany also ranks high on the Regional Authority Index. Accordingly, citizens should be able to realise that both levels matter for their everyday life and as such should also be influenced by the regional government. The German states do not only have political power over their own regions, but also influence national politics substantially. One reason for the powerful position of the German Bundesländer coalitions in national politics is based on the fact that the composition of the state governments directly translates to the partisan composition of Germany’s second chamber, the Bundesrat. The Bundesrat has strong veto potential in the federal law-making process. It is supposed to ensure the representation of state interests on the national level and has to approve all national legislation which affects the financial or substantial affairs of the regions (about 38% of all national legislation).

Additionally, regional government composition is also rather diverse in Germany. As of September 2023, the number of government parties ranges between just one in Saarland and three in states like Bremen and Saxony. With exception of the AfD, all parties that are members of the German Bundestag, are part of at least one regional government. Amongst those, the FDP is the only party that does not have a state premiership. Hence, there is enough variation at the regional level to analyse the influence of regional government composition on party perceptions. In toto, this makes Germany a most-likely-case for finding effects of regional coalition heuristics: if it is not present here, party leaders in more centralised states probably should not worry about this mechanism.

Dependent and independent variables

The aim of this article is to test whether regional government participation has an influence on the perceived closeness of parties on the national level. Accordingly, the unit of observation in our dataset is the voter-party-dyad. Or, in other words, for every respondent in the surveys, we have as many observations as there are unique combinations of parties (one line per party-dyad per respondent).

We rely on data provided by the German Longitudinal Election study (GLES Citation2019a, Citationb, Citationc; GLES Citation2023) and include four pre-electoral survey waves between 2009 and 2021. This does not only guarantee that there is variation in government composition at the regional and at the national level but also increases the generalisability of our findings.

The dependent variable is the perceived ideological difference between the two parties of the dyad on the national level.Footnote3 Using party placements on a 11-point left-right scale, we can calculate the ideological distance between party A and party B based on the perception of the respondent. We take the absolute values as we are not interested in the direction of the difference per se. We include the six parties CDU, SPD, FDP, Linke, Grüne, and AfD since these were the relevant actors in national and regional party politics for the period we observe. The AfD is only included since 2013. We excluded the CSU because it only runs in Bavaria.Footnote4

Our main explanatory variable is regional government participation. It is coded ‘1′ if the parties in the dyad are in government together at the regional level and ‘0′ if this is not the case. Similarly, national government participation is also a dichotomous measure. In our observation period, there are two different national government configurations. First, between 2005 and 2009, as well as between 2013 and 2021, a grand coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD was in office. Second, between 2009 and 2013, the CDU/CSU led a government with the liberal party, the FDP.

Lastly, we also include two proxy measures for the concept of political sophistication. On the one hand, we include the education of the respondent in the analysis. While formal education is by no means a requirement for political sophistication, the two measures are found to be repeatedly and strongly correlated (e.g. Barabas et al. Citation2014). Therefore, education has been used as proxy for measuring the political attentiveness of individuals by similar studies (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013) On the other hand, we also include self-reported political interest which ranges between 1 (not at all interested) and 5 (very much interested). In the Online Appendix Table B.3, we include a measure for political knowledge (a binary variable which is coded 1 if respondents answer correctlyFootnote5), which was available in all four survey rounds.

Control variables

We acknowledge that parties who are able to form governments at the regional level usually have more in common than other parties. To establish that our proposed relationship is not spurious, we control for ideological distances in national manifestos as a proxy for the underlying ideological differences between parties. In the Online Appendix, we substitute regional manifestosFootnote6 and expert party placements at the national level (Bakker et al. Citation2015) for the national manifesto data, and found that our results were largely robust (see Tables B.5 and B.6 in the Online Appendix).

In addition, we include a dummy variable distinguishing between East and West Germany and a few individual-level predictors. Specifically, we control for the voters’ ideological extremity, which is calculated by taking the absolute distance between the respondents’ self-placement on a 11-point left-right scale and the midpoint of the scale (5), gender (baseline: male), and age in years. While we do not have any strong expectations about how socio-demographics might impact perceived distances between parties, we do acknowledge that they are correlated with political sophistication and thus we include them in the analysis. In the Online Appendix, we also control for timing effects since we know that partisan communication about differentiating themselves changes during the legislative period (Sagarzazu and Klüver Citation2017). The time effect is measured as how many days there are left until the next regularly scheduled regional election (linear and squared). Descriptive statistics for all variables can be found in Online Appendix section A.

Data structure

Our data has a complex cross-classified multilevel structure. Voters are hierarchically nested in regions, but each voter is evaluating multiple party-dyads and each party-dyad is present in multiple regions as well as in the individual survey years. Thus, party-dyads are crossed with both voters, regions and survey years and we include random effects for 16 regions, 15 party-dyads, 9643 voters and four survey years. It is necessary to include party dyad random effects because the party-dyads have well-established reputations for being closer or further apart which is not entirely captured by their manifestos. Table A.2 in the Online Appendix illustrates these differences. Mean distances vary between 1.28 for the SPD-Grüne dyad and 7.57 for the AfD-Linke dyad. In this project we are more interested in explaining variation in perceptions within dyads between regions, than between the party-dyads themselves. Furthermore, it is necessary to account for historical differences between regions and for idiosyncrasies of how individual voters interpret the left-right scale.

Analysis

In the theory section, we proposed that regional government participation should decrease the perceived distance between two parties and that this effect should be dependent on national government participation and the level of political sophistication. Since we use two different variables to operationalise political sophistication, includes four models: one baseline model that only includes the explanatory and control variables, one model that includes the interaction effect between being in government at the regional and the national level, one model that includes an interaction effect between regional government participation and political knowledge and one model with the interaction effect between regional government participation and political interest

Table 1. Multilevel models predicting distance.

The results in model 1 support our main hypothesis: the coefficient for regional government participation is negative and significant. Thus, parties are perceived to be closer together at the national level if they are partners in government at the regional level. However, the effect size is overall rather small with −0.062. Substantively this means that parties are perceived to be 0.06 points closer if they are in regional government together.

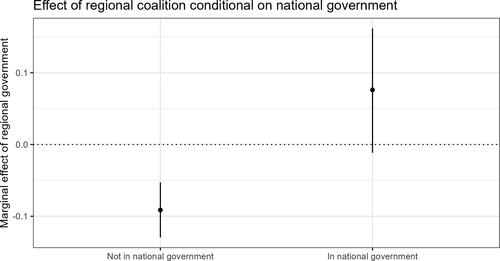

Model 2 displays the results for the interaction effect with national government participation. We proposed that the effect for regional government participation should be strongest if the same parties are not in government at the national level. The interaction effect between these two variables is significant and shows the expected effect.

displays the interaction effect based on model 2. We can see that the effect of regional government participation is negative and significant if parties are not in government together at the national level. Thus, voters perceive them as 0.09 points closer together, which supports our second hypothesis. If the parties are in national government, we do find a positive but not significant effect.

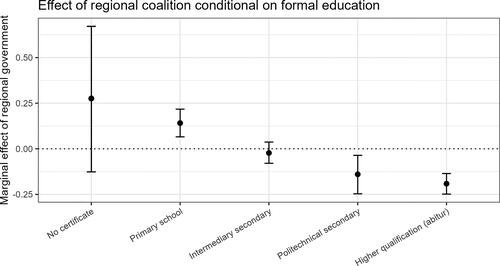

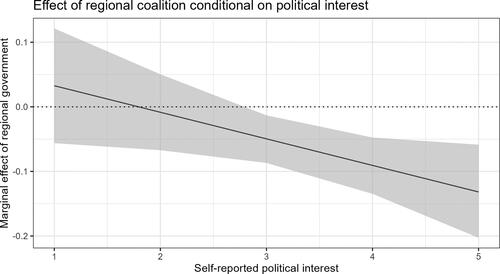

In models 3 and 4, we test the interaction effect between regional government participation and political sophistication. In model 3, we interact education with regional government participation, and in model 4, self-reported political interest conditions the effect of being in government at the regional level. In both models, the interaction effect is significant and negative. To interpret the findings substantively, we graphically illustrated the effects from both models in and . Both figures clearly demonstrate that political sophistication is an important mediator for regional government participation. The average marginal effect of regional government participation is around −0.19 for those that have a higher qualification (Abitur) while it is basically 0 for those with intermediary secondary qualification. We see a similar pattern for political interest: the AME of regional government participation is at around −0.14 for respondents with high levels of political interest (5), significantly lower at −0.05 for those with mean levels of political interest (3) and not significantly different from zero for respondents with lower levels of political interest (1 and 2). Moreover, we show in the Online Appendix, section B Figure B.1 that respondents who answered the political knowledge question correctly, are significantly more likely to apply regional coalition heuristics and perceive regional coalition partners as closer together. In contrast, respondents who answered incorrectly show no significant effect.

What is also interesting is the fact that regional government participation has a positive influence on perceived distance between two parties for those that have low levels of education (0 and 1) and very low levels of political interest (1). Though the positive effect is only significant for respondents with primary school education. Substantively this means that respondents with very low levels of political sophistication tend to perceive parties to be further apart if they are in regional government together. A potential explanation for this finding could be that respondents with lower levels of political sophistication are also more likely to shirk on this part of the survey and place the parties pseudo-randomly on the left-right scale. Additionally, coalition formation research has shown that ideologically close coalitions are more likely to form (see e.g. Martin and Stevenson Citation2001). Hence, this finding could be an artefact of the regression to the mean: if one places the parties at random, then the distances between parties that are ‘actually’ close together, and tend to govern together, will be systematically overestimated.

These findings clearly suggest that using this heuristic requires a fairly high level of political sophistication. Only voters who are aware of regional politics and coalitions can use the cue to make inferences about party placement. In other words, the coalition heuristic is not (just) a way for ignorant voters to substitute actual information about politics, but instead works as the lens through which even highly sophisticated voters can make sense of the political news they consume.

While we do find support for all three hypotheses, the actual effect sizes are comparatively small. However, we argue that these effects are still substantial for the most sophisticated segment of the electorate for three reasons. First, previous research has shown that left-right positions are overall rather stable (see e.g. Dalton Citation2016). Considering this, even picking up on small shifts in the perception of voters is important, especially since among the eight dyads which we actually observe as government coalitions (i.e. excluding all AfD dyads and excluding FDP-Linke and CDU-Linke dyad), the mean distance is only 2.24 points. Second, Fortunato and Stevenson (Citation2013) also find comparatively small effect sizes of around 0.5. Since we argue that regional government composition adds to the national level effect, effect sizes between 0.06 and 0.2 are not surprising and were to be expected. Third, and most importantly, we measure the effect of regional coalition membership on national parties just before the general elections at the national level. Thus, at a time when national politics should be at the forefront of the voters’ mind. The fact that we can still identify highly robust effects supports our arguments and increases our confidence in the importance of the results.

In terms of control variables, we find that, national government participation reduces the perceived distance between two parties in all models about a half point. As expected, national manifesto distance has a positive influence on the perceived distance between parties. This means that as the distance between the parties based on the manifestos increases, the perceived distance also increases. The respondent level control variables additionally have an influence on the perceived distance. For instance, older respondents perceive parties to be further apart than younger voters whereas women perceive parties to be closer together than men.

We additionally included a number of robustness checks which can be found in the Online Appendix. In Tables B.5 and B.6, we substitute the national manifesto data with regional manifesto data and expert survey data from the CHES. Our results remain substantially the same despite a significantly reduced sample due to lack of regional manifesto data after 2020 (from 127,119 observations and 9643 respondents to 98,352 observations and 8506 respondents). Table B.3 further includes models in which we treat the variables for political knowledge and control for time effects. Figure B.1 shows that political knowledge is an important moderator for regional coalition heuristics and supports our theory. Moreover, model B1 shows that time, i.e. how long the regional government has left until the next scheduled elections, has a significant effect but does not affect our findings. Lastly, Table B.4 includes the full sample of respondents while for our main models, we excluded respondents still in school or with a degree different from the traditional German education degrees. Again, our results remain stable.

Finally, we collected some additional evidence in order to support the causal mechanism behind the effects. We argue that in strongly federalised countries such as Germany, citizens do not only receive a coalition signal by parties based on national government participation, but they receive a second signal based on regional government participation. Based on this second cue, respondents use coalition heuristics when placing political parties in the ideological space. In the Online Appendix section C, we show the federal character of the German newspaper system: more than 80% of the German printed dailies are local or regional newspapers, which are more likely to regularly report on regional politics than national newspapers. Hence, Germans who read newspapers are highly likely to be informed about regional politics.

To further investigate if Germans are indeed aware of their regional government, we make use of a survey question from the third wave of the GLES panel study from May 2017 where respondents were asked to allocate politicians to their respective parties. While most of the inquired politicians were active in national politics (e.g. chancellor Angela Merkel or vice chancellor Sigmar Gabriel), the survey also asked about one regional politician: Winfried Kretschmann who was the regional prime minister of the Bundesland Baden-Württemberg and the regional party leader of the Green party. The data shows that respondents from his own Bundesland are substantially more likely to know that Kretschmann is a member of the Greens. In contrast, we cannot find such a strong regional effect for the national politicians Merkel and Gabriel. This data supports our causal claim: citizens in strongly federalised countries have the means to be highly informed about regional politics and actually have substantially higher knowledge about their regional government. Based on this, they are more likely to make use of regional coalition heuristics.

Conclusion

In this article, we add to the existing literature on party perception by including a multi-level system component and analysing the influence of regional government participation on the perception of parties. More specifically, we have argued that regional government participation can also be an important coalition signal for citizens with regard to the placement of parties on a left-right scale in highly federalised political systems such as Germany. We further posited that this coalition cue should especially be used by politically sophisticated voters since they are more aware of regional coalition membership. We relied on data from the German Longitudinal Election Study to test our hypotheses.

Our analysis provides important evidence that governing together at the regional level is associated with a statistically significant decrease in the perceived ideological distance between two parties – however, we also find that the effect is too small to have a substantial effect on the behaviour of the average German citizen. As awareness and knowledge of politics on the regional level is lower in comparison to national level politics, the effect of regional coalition membership is much smaller than the one of national coalition membership. Moreover, the effect is stronger if the parties only cooperate at the regional but not at the national level. Lastly, we show that respondents with higher political sophistication are more likely to use coalition heuristics as they are not only aware of national, but also well informed about regional level politics.

Our results have important implications for the consequences of government participation in complex multi-level systems. Regional government participation has an influence on the perception of parties at the national level, albeit marginal. Being aware of this fact should impact the communication strategies of political parties. Our results can be considered encouraging to politicians and parties considering testing new coalition options at the regional level as suggested by previous research (see e.g. Gross and Niendorf Citation2017). While regional government participation has an influence on perception of parties by the voters, the substantive change is not that big. Hence, forming new and potentially unexpected coalitions at the regional level does not seem to be that consequential for national parties.

The findings of this article also have potential consequences for survey research in federal countries as one cannot be completely sure that the perceptions of parties are not influenced by regional party perceptions. A specification of the questioning that includes the level of interest (i.e. national vs. regional) for party perceptions would potentially help to disentangle those effects.

The fact that Germany has high values on the Regional Authority Index is beneficial for our argument and this makes Germany a likely case. However, this also entails the disadvantage that the generalisability is somewhat limited. For our theoretical argument to work, we require regional governments that matter and have a say in legislation – at least at the regional level. Comparing the regional authority of Germany to other countries, the most likely cases where our arguments should travel are Belgium and Spain. Other countries such as France or Italy score high on the self-rule but not on the shared-rule dimension. Assuming that authority within the region is most important for our argument, France and Italy should also be valid cases. We strongly hope that future research will investigate this question further.

Finally, future research should take a closer look at how past governing arrangements influence the perception of voters. Previous research has found that the familiarity of coalitions has a significant effect on perceptions: i.e. parties that have governed together frequently in the recent past are perceived as more ideologically similar – even if they are not in a coalition presently (Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013). There is no reason to believe that this would not also be the case for regional governing arrangements. Uncovering how perceptions are formed in a complex interaction between regional and national coalitions, past and presents, remains a worthwhile challenge for the subfield.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (582.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers, the participants of the research seminar at the Department of Government at the University of Vienna, as well as Fabio Ellger and Martin Gross for their helpful comments on our manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ida B. Hjermitslev

Ida B. Hjermitslev is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. She studies comparative political behaviour with a special focus on voters’ responses to coalition formation. Her work is featured in journals such as European Journal of Political Research and Party Politics. [[email protected]]

Svenja Krauss

Svenja Krauss is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. Her main research interests are coalition governments, political representation and multi-level politics. Her work has been published, amongst others, in journals such as West European Politics and the Journal of European Public Policy. [[email protected]]

Maria Thürk

Maria Thürk is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Social Sciences, University of Basel. Her research focuses on minority cabinets, coalition governments, party competition, and legislative institutions. Her work has been published in the European Journal of Political Research, Legislative Studies Quarterly, and other political science journals. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 Own calculations based on data provided by https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/255400/umfrage/wahlbeteiligung-bei-landtagswahlen-in-deutschland-nach-bundeslaendern/.

2 We are not talking about familiarity here in the broad sense, i.e. whether or not the coalition has been in office before. We are only concerned with whether or not the same government coalition is in office at the national and the regional level.

3 We construct this variable based on the following question: In politics people often talk of ‘left’ and ‘right’. Where would you place the following parties on this scale?

4 This implies that for voters in Bavaria, no party-dyad will be coded as the regional government.

5 In the federal elections you have two votes, the first vote and the second vote. What do you think: Which vote decides how many seats each party will have in parliament?

6 In a few cases there was no regional manifesto recorded, so in these cases we used the national manifestos.

References

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Christopher Wlezien (2016). ‘The Company You Keep: How Voters Infer Party Positions on European Integration from Governing Coalition Arrangements’, American Journal of Political Science, 60:4, 811–23.

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu (2011). ‘Is Anybody Listening? Evidence That Voters Do Not Respond to European Parties’ Policy Statements during Elections’, American Journal of Political Science, 55:2, 370–82.

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu (2014). ‘Do Voters Respond to Party Manifestos or to a Wider Information Environment? An Analysis of Mass-Elite Linkages on European Integration’, American Journal of Political Science, 58:4, 967–78.

- Aldrich, John H., Gregory S. Schober, Sandra Ley, and Marco Fernandez (2018). ‘Incognizance and Perceptual Deviation: Individual and Institutional Sources of Variation in Citizens’ Perceptions of Party Placements on the Left–Right Scale’, Political Behavior, 40:2, 415–33.

- Axelrod, Robert (1970). Conflict of Interest: A Theory of Divergent Goals with Applications to Politics. Chicago: Markham.

- Bakker, Ryan, Catherine de Vries, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Anna Vachudova (2015). ‘Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010’, Party Politics, 21:1, 143–52.

- Barabas, Jason, Jennifer Jerit, William Pollock, and Carlisle Rainey (2014). ‘The Question(s) of Political Knowledge’, American Political Science Review, 108:4, 840–55.

- Bernardi, Luca, and James Adams (2019). ‘Governing Coalition Partners’ Images Shift in Parallel but Do Not Converge’, The Journal of Politics, 81:4, 1500–11.

- Bräuninger, Thomas, Marc Debus, Jochen Müller, and Christian Stecker (2020). Parteienwettbewerb in den deutschen Bundesländern. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Cabeza, Laura, Gómez Braulio, and Sonia Alonso (2017). ‘How National Parties Nationalize Regional Elections: The Case of Spain’, The Journal of Federalism, 47:1, 77–98.

- Dahlberg, Stefan (2013). ‘Does Context Matter – The Impact of Electoral Systems, Political Parties and Individual Characteristics on Voters’ Perceptions of Party Positions’, Electoral Studies, 32:4, 670–83.

- Dalton, Russell J. (2016). ‘Stability and Change in Party Issue Positions: The 2009 and 2014 European Elections’, Electoral Studies, 44, 525–34.

- Däubler, Thomas, and Marc Debus (2009). ‘Government Formation and Policy Formulation in the German States’, Regional & Federal Studies, 19:1, 73–95.

- de Swaan, Abram (1973). Coalition Theories and Cabinet Formations: A Study of Formal Theories of Coalition Formation Applied to Nine European Parliaments after 1918. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Detterbeck, Klaus, and Eve Hepburn (2018). ‘Statewide Parties in Western and Eastern Europe: Territorial Patterns of Party Organizations’, in Klaus Detterbeck and Eve Hepburn (eds.), Handbook of Territorial Politics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 120–38.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert, and Pablo Fernandez-Vazquez (2020). ‘Choices That Matter: Coalition Formation and Parties’ Ideological Reputations’, Political Science Research and Methods, 8:2, 285–300.

- Falcó-Gimeno, Albert, and Tània Verge (2013). ‘Coalition Trading in Spain: Explaining State-Wide Parties’ Government Formation Strategies at the Regional Level’, Regional & Federal Studies, 23:4, 387–405.

- Fortunato, David, and James Adams (2015). ‘How Voters’ Perceptions of Junior Coalition Partners Depend on the Prime Minister’s Position’, European Journal of Political Research, 54:3, 601–21.

- Fortunato, David, and Randolph T. Stevenson (2013). ‘Perceptions of Partisan Ideologies: The Effect of Coalition Participation’, American Journal of Political Science, 57:2, 459–77.

- Ganghof, Steffen, and Thomas Bräuninger (2006). ‘Government Status and Legislative Behaviour: Partisan Veto Players in Australia, Denmark, Finland and Germany’, Party Politics, 12:4, 521–39.

- GLES (2019a). ‘Vorwahl-Querschnitt (GLES 2009)’, Köln: GESIS Datenarchiv, ZA5300 Datenfile Version 5.0.2,

- GLES (2019b). ‘Vorwahl-Querschnitt (GLES 2013)’, Köln: GESIS Datenarchiv, ZA5700 Datenfile Version 2.0.2,

- GLES (2019c). ‘Vorwahl-Querschnitt (GLES 2017)’, Köln: GESIS, ZA6800 Datenfile Version 5.0.1,

- GLES (2023). ‘GLES Querschnitt 2021, Vorwahl’, Köln: GESIS, ZA7700 Datenfile Version 3.1.0,

- Gross, Martin, and Michael Jankowski (2020). ‘Dimensions of Political Conflict and Party Positions in Multi-Level Democracies: Evidence from the Local Manifesto Project’, West European Politics, 43:1, 74–101.

- Gross, Martin, and Svenja Krauss (2021). ‘Topic Coverage of Coalition Agreements in Multi-Level Settings: The Case of Germany’, German Politics, 30:2, 227–48.

- Gross, Martin, and Tim Niendorf (2017). ‘Determinanten der Bildung nicht-etablierter Koalitionen in den deutschen Bundesländern, 1990–2016’, Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 11:3, 365–90.

- Harnischmacher, Michael (2015). ‘Journalism after All: Professionalism, Content and Performance – A Comparison between Alternative News Websites and Websites of Traditional Newspapers in German Local Media Markets’, Journalism, 16:8, 1062–84.

- Hjermitslev, Ida B. (2020). ‘The Electoral Cost of Coalition Participation: Can Anyone Escape?’, Party Politics, 26:4, 510–20.

- Hjermitslev, Ida B. (2023). ‘Collaboration or Competition? Experimental Evidence for Coalition Heuristics’, European Journal of Political Research, 62:1, 326–37.

- Hobolt, Sara, James Tilley, and Susan Banducci (2013). ‘Clarity of Responsibility: How Government Cohesion Conditions Performance Voting’, European Journal of Political Research, 52:2, 164–87.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, Arjan H. Schakel, Sara Niedzwiecki, Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz, and Sarah Shair-Rosenfield (2016). Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Jae-Jae Spoon (2016). ‘Who Responds? Voters, Parties and Issue Attention’, British Journal of Political Science, 46:3, 633–54.

- Klüver, Heike, and Jae-Jae Spoon (2020). ‘Helping or Hurting? How Governing as a Junior Coalition Partner Influences Electoral Outcomes’, The Journal of Politics, 82:4, 1231–42.

- Krauss, Svenja, Katrin Praprotnik, and Maria Thürk (2021). ‘Extra-Coalitional Policy Bargaining: Investigating the Power of Committee Chairs’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 27:1, 93–111.

- Lupia, Arthur, and Kaare Strøm (1995). ‘Coalition Termination and the Strategic Timing of Parliamentary Elections’, American Political Science Review, 89:3, 648–65.

- Martin, Lanny W., and Randolph T. Stevenson (2001). ‘Government Formation in Parliamentary Democracies’, American Journal of Political Science, 45:1, 33.

- Martínez-Cantó, Javier, and Henning Bergmann (2019). ‘Government Termination in Multilevel Settings: How Party Congruence Affects the Survival of Sub-National Governments in Germany and Spain’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 30:3, 379–99.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm (2000). Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reif, Karlheinz, and Hermann Schmitt (1980). ‘Nine Second-Order National Elections: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results’, European Journal of Political Research, 8:1, 3–44.

- Rodden, Jonathan, and Erik Wibbels (2011). ‘Dual Accountability and the Nationalization of Party Competition: Evidence from Four Federations’, Party Politics, 17:5, 629–53.

- Sagarzazu, Iñaki, and Heike Klüver (2017). ‘Coalition Governments and Party Competition: Political Communication Strategies of Coalition Parties’, Political Science Research and Methods, 5:2, 333–49.

- Shair-Rosenfield, Sarah, Arjan H. Schakel, Sara Niedzwiecki, Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, and Sandra Chapman-Osterkatz (2021). ‘Language Difference and Regional Authority’, Regional & Federal Studies, 31:1, 73–97.

- Shikano, Susumu, and Eric Linhart (2010). ‘Coalition-Formation as a Result of Policy and Office Motivations in the German Federal States: An Empirical Estimate of the Weighting Parameters of Both Motivations’, Party Politics, 16:1, 111–30.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Heike Klüver (2017). ‘Does Anybody Notice? How Policy Positions of Coalition Parties Are Perceived by Voters’, European Journal of Political Research, 56:1, 115–32.

- Stromback, J., M. Djerf-Pierre, and A. Shehata (2013). ‘The Dynamics of Political Interest and News Media Consumption: A Longitudinal Perspective’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25:4, 414–35.

- Thorlakson, Lori (2017). ‘Representation in the EU: Multi-Level Challenges and New Perspectives from Comparative Federalism’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24:4, 544–61.

- Warwick, Paul (1994). Government Survival in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Warwick, Paul (1996). ‘Coalition Government Membership in West European Parliamentary Democracies’, British Journal of Political Science, 26:4, 471–99.

- Wehden, Lars-Ole, and Daniela Stoltenberg (2019). ‘So Far, Yet So Close: Examining Translocal Twitter Audiences of Regional Newspapers in Germany’, Journalism Studies, 20:10, 1400–20.