Abstract

In exploring protest dynamics, Protest Event Analysis (PEA) has proven an indispensable analytic tool. Despite various improvements, PEA faces continuous challenges, notably the reproduction of media-specific selection biases. This research note aims to contribute to the literature seeking to mitigate these issues by exploring the potential of PEA based on local newspaper data, which tend to be less selective in their protest reporting. The article introduces an original local PEA dataset in Germany (2000–2020) and systematically compares it to existing national-level PEA data for Germany. The analysis shows that while both datasets pick up similar trends in terms of mobilisation waves, national level data focus on shorter periods of intense protest activity. Furthermore, issues of protest differ: material and social issues (including labour and environmental issues) are more prominent in local data, while cultural issues (including immigration and gender) are more prominent in national-level data.

Large protest waves across the globe like Black Lives Matter and climate demonstrations are the most visible peaks of this non-institutionalised form of political participation. But in order to understand broader trends and developments of protests, reliable data across time and place are crucial. For this purpose, many social movement scholars employ Protest Event Analysis (PEA), by now an established analytical tool. Often based on national newspapers, PEA provides reliable information on a country’s most visible protests. PEA-generated data are indispensable for cross-country comparisons (Kriesi et al. Citation2020a) and the analysis of long-term developments in protest mobilisation (e.g. Koopmans Citation1993).

While continuous developments in PEA and associated data collection efforts have greatly improved our empirical and theoretical understanding of protest dynamics, PEA also faces continuous challenges. In particular, it is widely acknowledged that its reliance on national newspapers or other media outlets tends to reproduce media-specific attention cycles and selection biases (Hutter Citation2014), in fact, only a small number of protests are actually selected for reporting in national news (Smith et al. Citation2001). Scholars have proposed different ways to mitigate these issues, for example, by adding other data sources such as online content or police statistics (Fisher et al. Citation2019; Kousis et al. Citation2018; Oliver et al. Citation2023). In the present article, we explore the potential of PEA based on local newspaper data to address these limitations. We introduce a new, fine-grained local dataset in Germany and systematically compare it to national-level data.

PEA based on local newspapers is promising for three reasons: First, it improves our understanding of local protest dynamics, which tend to be understudied since PEA data often draw on nationwide media (newswires and newspapers) and miss a significant share of local protest activity. Local politics deserve more attention because they play a crucial role in people’s political opinion and political participation (Le Galès Citation2021). Especially in decentralised political systems, such as Germany, a broad range of political decisions are made at the local level. In fact, empirical evidence demonstrates that political decision makers pay particular attention to protest dynamics in their local districts (Gillion Citation2012). Hence, understanding local political dynamics is key to explaining political outcomes. Second, such data on local protest activity is not only fundamental for understanding local politics; rather, there is increasing evidence that the local context affects protest politics and political decision making at the national level (e.g. Vetter Citation2007; Voss and Williams Citation2012). Taking a closer look at protest dynamics at the local level is thus also key to explaining national protest patterns. Third, existing studies suggest that local newspapers are less selective in their coverage of protests and hence may provide a more comprehensive coverage of protests than PEA based on national newspapers (Hocke Citation1996; Barranco and Wisler Citation1999). Accordingly, we expect that local PEA allows identifying certain biases in national-level PEA.

Against this background, we will systematically compare existing national-level PEA data for Germany with our original PEA dataset ProLoc based on local newspapers between 2000 and 2020. First, we will compare the frequency and distribution of events across both datasets and ask whether both perspectives capture similar trends of fluctuating protest intensity. Second, we seek to identify potential biases specific to PEA based on national media. Going beyond event frequency, we will compare issues of protest identified in our dataset with those included in the national one: Do the national news attention cycles possibly lead to an overrepresentation of certain events and issues? Finally, we also seek to address a more general question: Is an aggregate of local protest data able to capture a country’s relevant protests better than an analysis relying on national newspapers’ and newswires’ selection of protest events?

Our findings confirm that local newspapers are much less selective in their coverage of protests and overall cover a higher number of events. At the same time, our local dataset captures the mobilisation dynamics manifested in national PEA, thus suggesting that aggregating local data may be a promising avenue forward. Fundamentally, our analysis demonstrates that in national-level data cultural issues are more present, such as immigration and gender relations, while material and social issues are much less visible, in particular labour, environment, infrastructure, and education. We thus systematically spell out the possible issue-related bias of national-level PEA data, a bias that has long been known to exist but that, to our knowledge, has not yet been documented in detail. We argue that such bias should be taken into account when national-level PEA are used to identify long-time trends in protest issues.

Developments in PEA

With PEA’s prominent status within social movement studies, different limitations of PEA have been discussed over the years (see Hutter Citation2014) – most prominently its media bias. PEA datasets that rely on newspapers or other media outlets tend to reproduce media-specific attention cycles and selection biases. In fact, only a small number of protests are actually selected for news reporting, depending on a variety of factors, including the event’s characteristics, in particular its size, the presence and amount of violence, and the participation of popular public figures (Hellmeier et al. Citation2018; Jennings and Saunders Citation2019; McCarthy et al. Citation1996; McCurdy Citation2012). Moreover, specific media routines and so-called ‘media attention cycles’ affect whether a protest event will be reported, in particular whether a protest issue ‘fits’ into already ongoing salient national (media) debates (Brown and Harlow, Citation2019; Hellmeier et al. Citation2018; Jennings and Saunders Citation2019; McCarthy et al. Citation1996; Smith et al. Citation2001; Teune and Sommer Citation2017). Accordingly, large and violent protests will receive more media attention as do protests that address an issue that is already salient in public discourse. Furthermore, studies found a certain path-dependency: protests that already received media attention will receive more (e.g. Hellmeier et al. Citation2018).

Scholars have suggested different ways to deal with the media bias in PEA datasets (Jenkins and Maher Citation2016). This includes comparing different news outlets (e.g. Dollbaum Citation2021), adding other data such as online sources (Fisher et al. Citation2019; Kousis et al. Citation2018; Beyerlein et al. Citation2018) and official statistics or clustering events into campaigns (Oliver et al. Citation2023). In the present research note we address the issue by comparing a national with a local PEA dataset.

Scholars studying protests have been interested in local and regional newspapers since the late 1990s due to their influential role in shaping local political discourses, mobilisations and decisions (e.g. Oliver and Meyer Citation1999). A range of studies by now have examined how local news cover protests and some recent datasets are based mainly on local newspapers (with a strong focus on English language sources, e.g. Leung and Perkins Citation2021). A large part of this research compares local protest reporting on specific protest issues and campaigns across different locations (e.g. Oliver et al. Citation2022; Rafail et al. Citation2019; Fillieule and Jiménez Citation2003). These studies point to considerable differences in local reporting and highlight specific local ‘receptivity climates’ (Rafail et al. Citation2019) linked to different organisational structures of local media, the locally or regionally specific salience of certain issues and overall political climates. For instance, Fillieule and Jiménez (Citation2003) show cross-national similarities between Germany, Sweden, Italy and Spain with respect to local and national media coverage of environmental protest issues but also differences stemming from specific national conflict and government structures.

Very few studies systematically compare protest reporting in local newspapers to national newspapers and/or police records across different issues.Footnote1 These studies show, firstly, that local media tend to be much less selective in covering protests than national media (e.g. Barranco and Wisler Citation1999; Hocke Citation1996; Citation2002; Oliver and Meyer Citation1999): in contrast to the estimated 2–10% of protest events that national media cover (Fillieule and Jiménez, Citation2003), local media cover a third to half of police reported events (51% Barranco and Wisler Citation1999; 38% Hocke Citation2002; 32% Oliver and Meyer Citation1999). Second, these comparisons show similar bias structures in the national and local press as they both overrepresent larger events (Barranco and Wisler Citation1999; Hocke, Citation2002; Oliver and Meyer Citation1999) and are more likely to report about more disruptive events (Barranco and Wisler Citation1999; Oliver and Meyer Citation1999; Oliver and Maney Citation2000). However, compared to the national press, the size of these two biases is smaller in the local press (Barranco and Wisler Citation1999), a finding also supported by Fillieule and Jiménez’ (Citation2003) comparison of national and local reporting on environmental protests in four countries.

Third, only Hocke (Citation1996; Citation2002) and Barranco and Wisler (Citation1999) have compared the distribution of protest issues between local and national news, and have come to partly contradictory findings due to the differing and rather broad issue categories they use. Concurring findings are that – contrary to expectations – local reporting is not dominated by local protest issues. They find a similarly strong presence of national issues and even a stronger presence of international topics in the local press. Also, they concurrently find that labour issues are more prominent in nation-wide media and certain cultural issues are more prominent in local reporting.Footnote2

Data and methods

The ProLoc data set includes protest data from four German cities between 2000 and 2020, with cities selected to balance structural similarities (regional centres with 500.000–600.000 inhabitants) and differences (two in the East, two in the West, two with predominantly centre-left and two with predominantly centre-right governments in the past two decades). While the selection is not representative of the local German protest landscape, it provides sufficient variation in contexts and topics. For instance, Leipzig and Dresden witnessed a peak in migration-related protest and counterprotest in 2014–2016, while Stuttgart was the centre of a protracted struggle about the construction of a new underground railway station that peaked in 2009–2011. Moreover, all four cities witnessed protests against the government’s measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 in 2020. We are thus confident that our selection of cities is relevant beyond the specific locations.

In each city, we draw our data from the largest local newspaper – Leipziger Volkszeitung, Sächsische Zeitung (for Dresden), Weser-Kurier (for Bremen) and Stuttgarter Zeitung. These four newspapers cover different political orientations, with the ones in Dresden and Stuttgart being more conservative and the ones in Leipzig and Bremen being more liberal. After obtaining the full texts for the years 2000–2020, we automated the selection process with a transformer-based classifier to identify protest-relevant news articles. The procedure, detailed in Wiedemann et al. (2022) yielded very good results with F1-scores constantly around .9. In a next step, the authors and a team of closely monitored student assistants hand-annotated the automatically selected articles. The data set contains 7346 events.Footnote3

For comparison, we use the PolDem-30 data set (Kriesi et al. Citation2020b), a protest event data set based on national-level news agencies which – like our dataset – also covers the years 2000–2020. The PolDem-30 data set has been used in several publications on contentious and party politics in Europe (Borbáth and Hutter Citation2021; Kriesi et al. Citation2020a; Kriesi and Oana Citation2023). For a robustness check, we also compare our data to the PolDem-6 data set, which is based on national newspapers but only covers a part of the period of our data set (2000–2011) (Kriesi et al. Citation2012). We first compare our local data to the full 3491 events recorded in PolDem-30 for Germany 2000–2020. Then, we restrict the data to match our local protest data by selecting only protest events that PolDem recorded in our four cities in the given time period, amounting to 294 events.Footnote4 To be able to compare topics across the two data sources, we recoded our topic variable (or ‘claim’ in ProLoc terminology) to match the ‘issue’ categories provided by PolDem. Because ProLoc has a more fine-grained topic structure modelled on the Prodat project (e.g. Rucht and Roth Citation2008), this was generally unproblematic. However, we sometimes had to sacrifice granular detail for comparability. For instance, we pooled our claim categories for ‘labour’, ‘social’, and ‘economic’ to match PolDem’s ‘economic (public)’ and ‘economic (private)’ and ‘healthcare’ categories. Also, we merged ‘infrastructure’ with ‘environment’ to match for PolDem’s broader ‘environment’ category that includes protests on infrastructure. In the Online Appendices, we provide full details of category harmonisation.

Findings

We now proceed to the comparison of the two data sets, focusing first on the distribution of events over time, after which we move on to comparing the issues that the recorded protests addressed.

Distribution of events across time

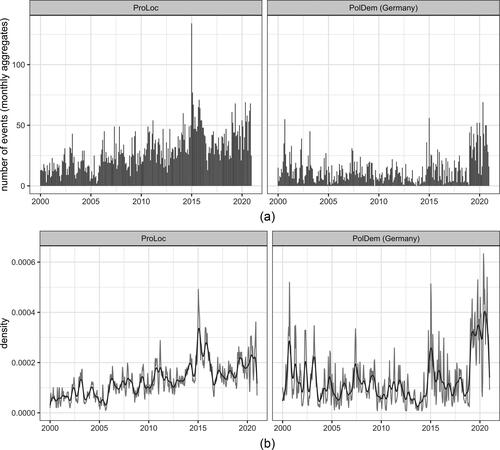

compares our ProLoc data to the PolDem data for the whole of Germany, displaying monthly aggregates of absolute numbers of events (upper panel) and kernel density plots, which can be interpreted as smoothed versions of day-based histograms (lower panel).Footnote5

Figure 1. Distribution of events*.

*Monthly aggregates (upper panel) and kernel density plots (lower panel) of protest events in both datasets, 2000–2020. Light grey in lower panels: bandwidth = 8, dark grey; bandwidth = 50. Source: Own data (ProLoc) on Leipzig, Dresden, Stuttgart, and Bremen and data from PolDem (Kriesi et al. Citation2020b) for Germany.

When visually inspecting the plots, we see that, first, even though ProLoc is based on only four cities, it picks up most waves of mobilisation that are visible in PolDem (the only exception is the first peak of the PolDem data in 2001), while their relative size differs across data sets. The protests against the Iraq war in 2003 and the resistance to a restructured system of unemployment benefits (‘Hartz IV’) in 2004/05 are visible in both data sets, as is rising contention around the outbreak of the financial crisis of 2008/09. Both also show a sharp increase in 2015 linked to the growing conflict over refugees and migration and an increase in 2019 that is most likely linked to the onset of intensified climate protests and in particular by Fridays for Future. The trend continues and mobilisation stays above average through 2020. This continued high level of protest is most likely linked to the onset of demonstrations against the measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 from 2020 onwards. If PolDem is taken as an indicator of societal conflict spilling out onto the streets, ProLoc identifies these moments as well, despite the much smaller geographical scope, although it appears to match the PolDem data more closely in the second half of the observed period.Footnote6

Second, the light grey line in the lower panel of Footnote7 brings the different structure of the data to the fore: In PolDem, the peaks of the curve are higher and the minima are closer to zero compared to ProLoc. This visual impression is supported when comparing the standard deviations of the two probability distributions, where PolDem’s value is larger than ProLoc’s by 30–50% (see Online Appendices). This shows that PolDem identifies shorter periods of intense protest activity, whereas the protest events in ProLoc are distributed much more equally over time, pointing again to different logics of reporting that may underlie the different databases: National news agencies tend to focus on major events and periods of intense contention, local newspapers provide a more constant stream of protest reporting. This means that nationally sourced PEA data likely focus on issues that are prevalent in such periods of intense contention, at the expense of issues that, while potentially equally important to people, are less concentrated in time – or that for other reasons do not attract the attention of national media. In the next step, we therefore compare the two data sets with respect to the issues that they cover.

Comparing issues of protest

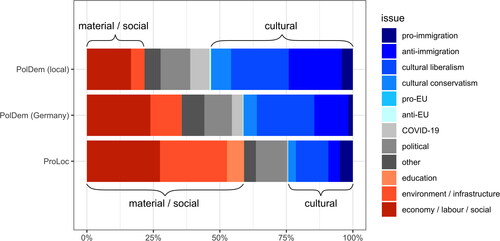

Overall, the distribution of issues varies considerably between our local PEA and the national PolDem data. compares ProLoc data from Leipzig, Dresden, Bremen and Stuttgart with (1) the PolDem-30 data for the same four cities (‘PolDem (local)’) and (2) the full PolDem-30 data across Germany (‘PolDem (Germany)’). As the figure shows, the distribution of issues differs substantially and systematically, with ProLoc and PolDem data for the same cities (PolDem Local) showing the strongest differences to each other, while the full PolDem data from across Germany occupy an intermediate position.

Figure 2. Comparison of protest topics*.

*Comparison of protest topics. Source: Own data (ProLoc) and data from PolDem (Kriesi et al. Citation2020b), 2000–2020. The category ‘political’ includes protests on ‘representation’ (e.g. anti-government demonstrations), corruption, electoral reform, and domestic institutional issues in general (Kriesi et al. Citation2020b: 9).

Since shows that the average number of reported protest events per year increases substantively in 2019, we disaggregate our analysis of covered topics for the periods 2000–2018 and 2019–2020 with stable results (see Online Appendices).

First, there are issues that are clearly more prominent in PolDem in comparison to ProLoc. These include culturally liberal issues like peace, women’s rights or LGBTQI + protests and culturally conservative issues (see ) that, as defined in PolDem’s codebook, constitute ‘counter-mobilisation to all aspects of cultural liberalism including racist mobilisation’ (Kriesi et al. Citation2020b: 10). Among these cultural issues it is particularly anti-immigration and conservative protests that feature strongly in the data. The share of pro-immigration protests is similar across both data sets. Finally, the protests about COVID (both for and against the measures to contain the virus) occupy a substantial share of all protests in PolDem, while they make up only a small fraction in ProLoc (despite the fact that our local sample includes cities with prominent protests against COVID measures, e.g. Stuttgart).

Second, some issues are less prominent in PolDem when compared to ProLoc. This is especially true for protests on education (practically non-existent in PolDem), protests on economic, social, and labour issues, and environmental protests, which include infrastructure protests per PolDem’s categorisation (see ). Hence, what is less prominent in national-level data appears to be overwhelmingly material issues of labour, infrastructure/environment and education.

There are two possible – and not mutually exclusive – explanations for our finding that national level data tend to report more cultural issues, while reporting fewer socio-economic ones compared to local data, both of which focus on reporting incentives for national media, which have been shown to be more selective than local newspapers. First, regarding media attention cycles (McCarthy et al. Citation1996), one could argue that protests on cultural topics fit popular diagnoses of the Western zeitgeist (Reckwitz Citation2017) and growing attention to cultural issues in political discourse (Kriesi et al. Citation2012). Accordingly, cultural protests might catch the interest of national reporters or seem more relevant to major publishers due to their (assumed) salience, accumulating into a higher general likelihood of cultural protest to be reported. Second, protests on labour issues, education, and infrastructure might be smaller and more often address local and regional authorities – two factors that make them potentially less relevant and less visible from the perspective of national newspapers.

We cannot test the first of these hunches, but our data allows for a rough check on the second. In the Online Appendices, we demonstrate that we neither find evidence in PolDem nor in ProLoc that protests on cultural issues are, on average, larger than protests on material issues, both when using the mean and when using the median. But in ProLoc we know that at least 31% of social/material protests explicitly address targets on the subnational level (i.e. municipal, regional, or state levels), while only 13% of cultural protests do.Footnote8 Social, environmental, and education-related protests may thus be underreported in national data partly because they address subnational targets more often than cultural protests do and therefore may less often be deemed relevant for national newspapers to report. Nonetheless, a considerable part of these protests does not address local targets and still remains overlooked in national level PEA.

Finally, since PolDem-30 is based on international newswires rather than national newspaper (as is the standard in PEA data), we conduct a robustness check with PolDem-6, which is based on the Monday issues of the Frankfurter Rundschau. Because PolDem-6 ends in 2011, the overlap with our data is only twelve years (one reason to focus the comparison on PolDem-30 in the first place). The procedure is explained in detail in Online Appendix G, where we show that the comparison yields similar, if not larger differences. This suggests that we are observing differences between national and local reporting more generally, not simply between news agencies and local newspapers.

Discussion and conclusion

This article compares Protest Event Data sets based on local and national sources. With regards to the distribution of events we show that, while both datasets pick up similar trends in terms of mobilisation waves (particularly for the second observed decade), national-level data focus on shorter periods of intense protest activity. With regards to protest issues we show considerable differences. In particular, we find that protests on material and social issues (including labour and environmental issues) are much more visible in local reporting than in national reporting, while protests on cultural issues are much more prominent in national reporting than in local news. We show that this difference could not be traced back to social-economic protests being smaller and that it could only partly be attributed to the fact that socio-economic protests more often address local targets.

We do not think that the observed difference is a result of an empirical difference, i.e. that cultural events are in fact more frequent at the national level, which national data tend to focus on. This is unlikely for two reasons: First, when we reduce the national-level data set to only the protest events taking place in our four cities, the distribution of issues does not change substantially. When comparing the four cities in both data sets, we still find a much higher proportion of cultural protest issues in the reduced national-level data set than in our local data set. Second, there is no reason to assume that salient national debates about cultural issues should only affect protests in the capital and not also affect protests in other large cities – including in the four cities of our sample. Especially in a federal state like Germany where significant decision-making power lies with the state governments, we would rather expect salient national issues to be also salient at the state level, and especially in state capitals like Bremen, Stuttgart, and Dresden.

Instead, it seems more likely that the difference between the local and national protest datasets are the result of issue-specific selection biases of national newspapers – given their stronger focus on protests about contested and politically salient issues (such as migration), as shown in various existing studies (Jennings and Saunders Citation2019). We therefore interpret our results in a way that national-level data in fact overrepresent cultural issues, in particular immigration and gender relations, while they underrepresent protests on material and social issues, like labour, environment, infrastructure or education. Since we are lacking an objective baseline, this is still an interpretation. More research is therefore required to further substantiate this. If this finding turns out to be robust in other contexts, it points to a serious bias in protest data sourced from national-level reporting on the issues that drive citizens to the streets. In addition, the question arises whether highlighted shifts in protest issues remain accurate, in particular the identified trend towards cultural protest issues – or whether this is merely a reflection of national media attention cycles.

Our results suggest that PEA will benefit from a more widespread use of local newspaper data that, ideally, is sourced from a large and representative sample of local newspapers. Local PEA data seem to provide a far more comprehensive picture of the protest landscape at the local level, from which trends at the national level can be extrapolated. For example, our local data from the four cities mirrors the broader protest trends reported in national newspapers – especially for the years 2011–2020 – while including many more events. But the lower overlap in the period of 2000–2010 also suggests that a broader base of local newspapers can improve results by making them less dependent on each particular source. So far, the amount of manual annotation necessary for such an endeavour has rendered this option unrealistic. The sheer volume of articles in hundreds of local newspapers was hardly manageable, and fully automatic workflows have proven to be too inaccurate to replace manually annotated PEA datasets (Oliver et al. Citation2023; Wang et al. Citation2016). However, the advent of large language models now offers new possibilities to automate PEA, and thus to compile local protest datasets, as we have shown previously (Wiedemann et al. Citation2022). It might hence be on the horizon to resolve the trade-off between manageability and accuracy that so far has characterised PEA – and which this research note has documented with regard to protest issues.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (571.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Priska Daphi

Priska Daphi is Professor of Conflict Sociology at Bielefeld University. Her research interests include political participation, protests, social movements, civil society and conflicts about globalisation, migration, climate change and war. Her research has been published in Political Geography, International Studies Review, Social Movement Studies, Mobilization and German Politics. [[email protected]]

Jan Matti Dollbaum

Jan Matti Dollbaum leads the junior research group ‘Mobilization as Representation in post-Soviet Eastern Europe’ at LMU Munich. The research project is funded by the Elite Network of Bavaria. His research has appeared in Comparative Political Studies, the European Journal of Political Research, and Perspectives on Politics. [[email protected]]

Sebastian Haunss

Sebastian Haunss is Professor for Political Science at the SOCIUM – Research Centre on Inequality and Social Policy at the University of Bremen. His research interests are social movements, protest, social policy, computational methods for text analysis and network analysis. He has published in Network Science, Social Movement Studies, European Union Politics, and with Cambridge University Press. [[email protected]]

Larissa Meier

Larissa Meier is a post-doctoral researcher at Bielefeld University. Her research focuses on political violence, civil society and political protest about war and peace. Her work has appeared in Social Problems, Perspectives on Politics and Sociological Forum. [[email protected]]

Notes

1 These studies include: two based on a dataset combining local newspapers and police records in the city of Madison, Wisconsin in 1994 (Oliver and Meyer, Citation1999, Oliver and Maney, Citation2000); two publications based on a dataset combining local and national newspapers as well as police records in the German city of Freiburg 1983-1989 (Hocke Citation1996; 2003); one publication based on a dataset covering four large Swiss cities (1964-1994) combining local and national newspapers and police records (Barranco and Wisler Citation1999).

2 Barranco and Wisler (Citation1999) find in their study of the four Swiss cities (1964-1994) that protests by New Social Movements are more prominent in local media as well as – perhaps not too surprisingly – protests by squatters. Hocke (Citation1996, Citation2002) in his study of Freiburg, Germany (1983-1986) finds that protests about international solidarity and left-liberitarian campaigns are more often reported in the local media (188). But in contrast to Barranco and Wisler he also finds that environmental issues (often considered as part of New Social Movements) are more prominent in national newspapers.

3 Due to incomplete coverage in the articles supplied by the publisher of the Sächsische Zeitung, our data set does not contain articles from Dresden between January 2011 and July 2012 and articles between 2000 and 2005 from Bremen. We exclude the respective periods for Dresden and Bremen from the PolDem data as well.

4 Note, however, that the PolDem data for Germany (as for other large countries) contains only 25% of the events that were detected (Kriesi et al. Citation2020b, p. 16-17). We therefore cannot make comparisons regarding the absolute number of protest events (or would have to multiply the PolDem values by 4, assuming even distribution). If the sampling of detected events in PolDem-30 is truly random, however, this should not have an impact on the distribution of mobilisation peaks and topics in PolDem.

5 Visually, these plots have an advantage over bar plots as they automatically normalise for the number of data points so that the plots are visually comparable even though the two data sets contain a different number of events.

6 While the trends in terms of waves of mobilisation are similar, the relative level of protest after 2019 is much higher in the PolDem-30 data compared to ProLoc. Partly, this may be an effect of inflated media attention to already salient issues such as climate change and COVID-19. However, the sudden rise is also likely related to a higher number of hits in the media search engines used to compile PolDem and ProLoc that are unrelated to the actual number of events. This hunch was confirmed in personal communication with the PolDem authors. Absolute numbers should thus be treated with caution, while this technical abnormality should have no effect on the distribution of issues covered further down.

7 Setting a low bandwidth for the kernel estimates limits the scope of the kernel function to small distances before and after each data point, making the line more sensitive to events that are grouped closely together in time.

8 We must be careful with interpreting this finding since our variable on the target level contains a large number of missing values (70%) which we must assume to be random with regard to the covered topic. For PolDem we cannot test this because the data set does not include a variable on the level of the addressed target.

References

- Barranco, José, and Dominique Wisler (1999). ‘Validity and Systematicity of Newspaper Data in Event Analysis’, European Sociological Review, 15:3, 301–22.

- Beyerlein, K., P. Barwis, B. Crubaugh, and C. Carnesecca (2018). ‘A New Picture of Protest: The National Study of Protest Events’, Sociological Methods & Research, 47:3, 384–429.

- Borbáth, Endre, and Swen Hutter (2021). ‘Protesting Parties in Europe: A Comparative Analysis’, Party Politics, 27:5, 896–908.

- Brown, Danielle K., and Summer Harlow (2019). ‘Protests, Media Coverage, and a Hierarchy of Social Struggle’, International Journal of Press/Politics, 24:4, 508–30.

- Dollbaum, Jan Matti (2021). ‘Protest Event Analysis Under Conditions of Limited Press Freedom: Comparing Data Sources’, Media and Communication, 9:4, 104–15.

- Fillieule, Olivier, and Manuel Jiménez (2003). ‘The Methodology of Protest Event Analysis and the Media Politics of Reporting Environmental Protest Events’, in Christopher Rootes (ed.), Environmental Protest in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 258–79.

- Fisher, Dana R. et al. (2019). ‘The Science of Contemporary Street Protest: New Efforts in the United States’, Science Advances, 5:10, eaaw5461.

- Gillion, Daniel Q. (2012). ‘Protest and Congressional Behavior: Assessing Racial and Ethnic Minority Protests in the District’, Journal of Politics, 74:4, 950–62.

- Hellmeier, Sebastian, Nils B. Weidmann, and Espen Geelmuyden Rød (2018). ‘In the Spotlight: Analyzing Sequential Attention Effects in Protest Reporting’, Political Communication, 35:4, 587–611.

- Hocke, Peter (1996). ‘Determining the Selection Bias in Local and National Newspaper Reports on Protest Events’. Berlin: Wzb. https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/1996/iii96-103.pdf

- Hocke, Peter (2002). Massenmedien und Lokaler Protest. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Hutter, Swen (2014). ‘Protest Event Analysis and Its Offspring’, in Donatella della Porta (ed.), Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 335–67.

- Jenkins, J. Craig, and Thomas V. Maher (2016). ‘What Should We Do about Source Selection in Event Data? Challenges, Progress, and Possible Solutions’, International Journal of Sociology, 46:1, 42–57.

- Jennings, Will, and Clare Saunders (2019). ‘Street Demonstrations and the Media Agenda: An Analysis of the Dynamics of Protest Agenda Setting’, Comparative Political Studies, 52:13–14, 2283–313.

- Koopmans, Ruud (1993). ‘The Dynamics of Protest Waves: West Germany, 1965 to 1989’, American Sociological Review, 58:5, 637.

- Kousis, Maria, Marco Giugni, and Christian Lahusen (2018). ‘Action Organization Analysis: Extending Protest Event Analysis Using Hubs-Retrieved Websites’, American Behavioral Scientist, 62:6, 739–57.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Ioana-Elena Oana (2023). ‘Protest in Unlikely Times: Dynamics of Collective Mobilization in Europe during the COVID-19 Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy, 30:4, 740–65.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominic Höglinger, Swen Hutter, and Bruno Wüest (2012). Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, et al. (2020a). ‘PolDem-Protest Dataset 30 European Countries, Version 1’, available at https://poldem.eui.eu/downloads/pea/poldem-protest_30_codebook.pdf (accessed 21 September 2022).

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Jasmine Lorenzini, Bruno Wüest, and Silja Hausermann, eds. (2020b). Contention in Times of Crisis: Recession and Political Protest in Thirty European Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Le Galès, Patrick (2021). ‘The Rise of Local Politics: A Global Review’, Annual Review of Political Science, 24:1, 345–63.

- Leung, Tommy, and L. Nathan Perkins (2021). ‘Counting Protests in News Articles: A Dataset and Semi-Automated Data Collection Pipeline’, available at http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.00917 (accessed 16 June 2023).

- McCarthy, John D., Clark McPhail, and Jackie Smith (1996). ‘Images of Protest: Dimensions of Selection Bias in Media Coverage of Washington Demonstrations, 1982 and 1991’, American Sociological Review, 61:3, 478–99.

- McCurdy, Patrick (2012). ‘Social Movements, Protest and Mainstream Media’, Sociology Compass, 6:3, 244–55.

- Oliver, Pamela E., and Daniel J. Meyer (1999). ‘How Events Enter the Public Sphere: Conflict, Location, and Sponsorship in Local Newspaper Coverage of Public Events’, American Journal of Sociology, 105:1, 38–87.

- Oliver, Pamela E., and Gregory M. Maney (2000). ‘Political Processes and Local Newspaper Coverage of Protest Events: From Selection Bias to Triadic Interactions’, American Journal of Sociology, 106:2, 463–505.

- Oliver, Pamela, Alex Hanna, and Chaeyoon Lim (2023). ‘Constructing Relational and Verifiable Protest Event Data: Four Challenges and Some Solutions’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 28:1, 1–22.

- Oliver, Pamela, Chaeyoon Lim, Morgan Matthews, and Alex Hanna (2022). ‘Black Protests in the United States, 1994 to 2010’, Sociological Science, 9:12, 275–312.

- Rafail, Patrick, John D. McCarthy, and Samuel Sullivan (2019). ‘Local Receptivity Climates and the Dynamics of Media Attention to Protest’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 24:1, 1–18.

- Reckwitz, Andreas (2017). Die Gesellschaft der Singularitäten: Zum Strukturwandel der Moderne. 1st Edition. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Rucht, Dieter, and Roland Roth (2008). ‘Soziale Bewegungen und Protest – Eine Theoretische und Empirische Bilanz’, in Roland Roth and Dieter Rucht (eds.), Die Sozialen Bewegungen in Deutschland seit 1945. Ein Handbuch. Frankfurt/Main: Campus Verlag, 635–68.

- Smith, Jackie, John D. McCarthy, Clark McPhail, and Boguslaw Augustyn (2001). ‘From Protest to Agenda Building: Description Bias in Media Coverage of Protest Events in Washington, D.C.’, Social Forces, 79:4, 1397–423.

- Teune, Simon, and Moritz Sommer (2017). ‘Zwischen Emphase und Aversion. Großdemonstrationen in der Medienberichterstattung’. Institut für Protest- und Bewegungsforschung, available at https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/ipb-Forschungsbericht-Großdemonstrationen-in-der-Medienberichterstattung.pdf (accessed 18 October 2017).

- Vetter, Angelika (2007). Local Politics: A Resource for Democracy in Western Europe? Local Autonomy, Local Integrative Capacity, and Citizens’ Attitudes toward Politics (Vol. 3). Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Voss, Kim, and Michelle Williams (2012). ‘The Local in the Global: Rethinking Social Movements in the New Millennium’, Democratization, 19:2, 352–77.

- Wang, Wei., Ryan Kennedy, David Lazer, and Naren Ramakrishnan (2016). ‘Growing Pains for Global Monitoring of Societal Events’, Science (New York, N.Y.), 353:6307, 1502–3.

- Wiedemann, Gregor, Jan Matti Dollbaum, Sebastian Haunss, Priska Daphi, and Larissa Daria Meier (2022). ‘A Generalizing Approach to Protest Event Detection in German Local News’, Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. https://aclanthology.org/2022.lrec-1.413/.