ABSTRACT

Taking risks might be encouraged, both in business and military strategy, when the potential price of losing would not be excessive while the gains in winning, worth wagering such a bet. In military contexts, a side set on aggression and conquest might take such a risk. Chance, fortuna, determining the outcome of risk taking has been seen differently throughout history – fatalistically, as prevalent in the Middle Ages – as been something that could not be influenced, or, as in Antiquity and in more recent times, as a factor open to influence by the astute and forceful military commander, or to prudent planners. New situations could be seen as dangerous and risky, with risks against which one has to hedge. Or they could be seen as a chance to change things in one’s own interest. This might be done through extensive contingency planning, or by seizing an opportunity quickly, applying the genius general’s coup d’oeil to turn a new development to one’s advantage, always conscious that this was a gamble and the outcome uncertain. While such a gamble could win or lose a battle and in turn a war, in the nuclear age, such a gamble would seem difficult to justify given the potential negative outcomes.

In battle, luck has greater dominance than manliness.

In the mid-2000s, a series of advertisements by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation could be found in airports around the world. Referred to as the “different points of value” advertising campaign, they would show images linking them to different interpretations, each encapsuled in one word, highlighting that the same image could be interpreted in different ways. One series showed pairs of pictures, each pair shown twice.Footnote2 Among them was a pair with the captions: “risk” and “opportunity”, while on the second pair of photos, the captions were inverted. The message: one person’s risk (and danger) can be another’s opportunity. But seizing an opportunity is not risk-free.

Both risk and opportunity are sometimes subsumed under the term of “chance”, in the sense of “unplanned occurrence” which at the same time creates a new possibility or an opportunity – for good or ill. The Oxford English Dictionary gives a range of current and obsolescent meanings of the word “chance”, such as “a happening or occurrence of things in a particular way; a casual or fortuitous circumstance”, “fortuitous” meaning “accidental”: it is not a synonym of “fortunate” in its current purely positive meaning.Footnote3

Is chance an accidental event, something to be welcomed or feared in the context of war and strategy? Answers to this have differed over time, and the views of chance, risk, and opportunity have changed, along with the terminology. Where today we think of “fortune” as good, and the French use of chance (j’ai de la chance) is equally used as meaning “lucky”, fortuna was seen as the source of good or bad luck in the past, just as Clausewitz’s Zufall (chance) could bring disaster or triumph. Fortuna was uncertain, as was chance or Zufall: it could be seen in a fatalistic way (as a fearsome external power that would decide on your fate), or else she could be seen as creating situations that the brilliant statesman, general or indeed merchant could exploit to his advantage, if he was gifted and determined enough to do so, if he had the coup d’oeil that allowed him to seize the opportunity. As the English proverb has it, he who dares, wins. Despite the variations in terminology and the changes in religion and culture, the underlying binarity persisted: uncertainty could be seen as an opportunity to exploit, albeit aware that one was taking risks, or as a threat to one’s plans. The chance or accidental event gets in the way of prediction. It can upset the adversary’s calculations. But it can also backfire badly, in the sense of upsetting one’s own carefully laid plans, turning into Murphy’s Law,Footnote4 and one can never make enough contingency plans for all these eventualities.

When would one take a risk, seize an opportunity with uncertain success, and when would one eschew risk and crave certainty, predictability, calculability? A risk is worth taking only if the consequences of failure are not too great, especially, if they are not entirely self-destructive for the risk taker, as they might be in a nuclear war that escalates to the extreme. We thus find risk seen in a positive light when the stakes are limited. Students of business strategy and officers educated in tactics, operations and military strategy are encouraged to look out for chance events that would give them the sudden opportunity to seize the advantage over their competitors resp. adversaries. They may however also be told that such chance events, or attempts to exploit them to one’s advantage, are risky, meaning that on a bad outcome, one might lose more than one has invested. As we shall see, these contradictory views of risk taking in the context of war can be detected throughout the history of Western civilisation.

Fortuna and Occasio in Antiquity

Curiously, for most of the previous two-and-a-half millennia, strategists pondering the role of chance in warfare excluded the enemy almost completely from their considerations. Instead, they attributed their own luck or misfortune to divine intervention. In Antiquity and the Middle Ages, chance was seen as a goddess – Tyche in Greek, Fortuna in Latin – with power over men’s lives. She was usually depicted as holding a cornucopia, sometimes standing on a ball (the globe?), holding a rudder signifying her control over her movements, even though these escaped human prediction not to mention control (). Fortuna, in her Greek form of Tyche, was connected with individual cities or city-states; if properly worshipped, she was expected to bring good fortune and prosperity to the polity, symbolised by her cornucopia.Footnote5Footnote6

Fortune might smile consistently upon certain individuals. Exceptional, fortunate individuals were thought from birth to be blessed and protected by a god (such as a divine ancestor), the gods in general, or their personal Tyche/Fortuna in particular. Or else, they might be cursed with a tragic destiny. The Greek heroes of the Iliad could not escape their destiny – Achilles for example would be slain in battle in a predestined way on account of a physical weakness he had from birth – but prior to that, they could lead a charmed life, bringing them triumphs and victories. The feats of Achilles and Alexander III of Macedon were such cases in question. Nor were Roman examples lacking. Plutarch in his Parallel Lives recounts a story about how Caesar, travelling in a ship during a ferocious storm, reassured the captain that there was no peril to the ship as he (with his personal Tyche) was on board.Footnote7 A tragic destiny – μοίρα, fatum – might still catch up with you, as it did with Achilles, Alexander, and Caesar. There was thus a tension between the belief in an immutable fate and in Tyche/Fortuna as a power that might, at least temporarily, mitigate or detract from that fate.

Greeks and Romans also saw good fortune as something that could at least in part be earned. Zeus as supreme god who had created order out of chaos was worthy of the ultimate good fortune of victory – Nike – and would be depicted as holding a little figure of Nike in his outstretched hand, or being crowned by Nike. Similarly, Athena, goddess of wisdom and wisely-fought war, would be shown holding a winged Nike. Order and wisdom would thus be rewarded by good fortune in the form of victory. Nike/Victoria and Tyche/Fortuna might be depicted together, as on a gold coin minted for emperor Augustus, now in the British museum (): significantly, one side shows Fortuna, once with the helmet of a warrior, once with a diadem; the other shows a winged victory, leaning on a ball or round shield.

Figure 2. Double depiction of Fortuna on obverse, and Victoria on the Reverse, Aureus of the reign of Augustus, © the Trustees of the British Museum, No. 18641128.25.8

Both goddesses would often be depicted walking on a ball (the orb, i.e., the globe), to emphasise their unsteadiness: examples of this include a denarius minted for Augustus when still known as Octavian, a sestertius minted for Commodus, and a gold medallion of Constantius II: in each case Victory holds out a laurel wreath to the respective ruler.Footnote9 While Tyche/Fortuna would be depicted with cornucopia and rudder as we have noted, Nike/Victoria would usually be shown as winged.

Besides believing in predestination from birth, Romans imagined humans as capable of pleading with fortune, or by their actions offsetting the uncertainties of fortune. Wisdom could come into play: Plautus (254–184 BCE) in one of his plays had a protagonist pronounce that “sapiens … ipse fingit fortunam sibi”, the wise crafts his own fortune.Footnote10 There was also the adage that “audentes Fortuna iuvat”, fortune favours the bold. Already in Caesar’s times this conjured up for Romans the idea of the hero or the strategist interacting with the goddess to impress her and persuade her to lend him her support. In this tradition, the fourth-century Roman author of the war manual which would dominate the following millennium in the West, Renatus Vegetius, discussed the importance of chance (fortuna), along with the luck of those who manage to exploit an unexpected opportunity.Footnote11 While the latter was often subsumed under Fortuna, some authors saw the goddess of opportunity as a separate deity, albeit one depicted in much the same ways as Fortuna. The Greek called this deity Kairos, rendered in Latin as Occasio.Footnote12 One illustration of this notion of the personified deity of the auspicious occasion is found in an epigram of Vegetius’ contemporary Ausonius:

- I am a goddess seldom found, and known to few, Opportunity [Occasio] my name.

- Why stand’st thou on a ball?

- I cannot stand still.

- Why wearest thou winged sandals?

- I am ever flying. The gift Mercury scatters at random, I bestow when I will.

- Thou coverest thy face with thy hair.

- I would not be recognised.

- But what! – art thou bald at the back of thy head?

- That none may catch me as I flea.

…

Thou also, whilst thou keepest asking, whilst thou tarriest with questioning, wilt say that I have slipped away out of thy hands.Footnote13

We find here the description of Occasio/Opportunity endowed with the joint attributes of Victoria and Fortuna: the former’s wings and the unsteady errant movements of the latter. Significantly, Opportunity is accompanied by another goddess, Penitence, who stays after Opportunity has slipped away, attributing reward or punishment according to whether one has seized the opportunity or let it go.Footnote14

Fortuna in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

Primitive minds associate misfortune with punishment. It seems that Norse philosophy assumed men were born with luck on their side, while lucklessness was the punishment for a transgression such as sacrilege, oath-breaking, peace-breaking, and the slaying of one’s own kin.Footnote15 Jesus and following him Christianity tried to fight against this interpretation with the story of Lazarus whose faith and inherent virtue was tried by God through the inflictions of many miseries, before being taken to heaven.Footnote16 As Christianity came to dominate European culture, the pre-Christian veneration of chance and fortune became highly problematic. Even Victoria, previously depicted in one tradition as winged and hovering above two figures (e.g., the jointly ruling emperors Diocletian and Maximus) upon whose heads she would place laurel wreathes, would be replaced in the same configuration by God or Christ bestowing such laurel wreaths upon saints, or with the same gesture, crowning emperors.Footnote17 God, the Lord of Hosts, not some goddess, had to be seen as bestowing victory upon the armies of his followers.Footnote18 As time went on, however, it became clear that the just – the Christian – side in war did not always prevail. Christian theologians resolved this conundrum by differentiating between this world and the next where this world’s injustice would be made good. Thus, even a defeat could be interpreted as a moral victory, with slain defenders of Christianity celebrated as martyrs.Footnote19

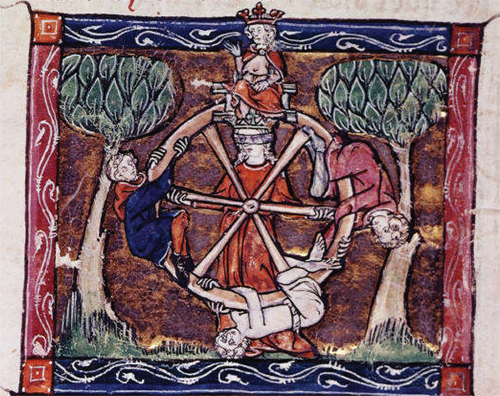

Christianisation did not manage to oust the pagan goddess Fortuna from elite culture. She assumed a somewhat different character in Medieval times: she was deemed unchallengeable. She now mostly appeared in medieval manuscripts modestly dressed, standing next to or behind a wheel of fortune as might have been found in medieval fairs, spinning it, blindfolded and dispassionate. Inexorably, the huge wheel would bring men to power and then crush them underfoot (). We find a depiction of the wheel of fortune, complete with a handle for Fortuna to turn it, in an engraving by Hans Sebald Beham; winged Fortuna is shown with her ball, but still seems quite in control of her movements (). Footnote20

Figure 3. Wheel of Fortune above an illuminated initial, France, Saint-Omer or Tournai, Morte Artu, (c.1316).20

Following the late Roman philosopher Boethius, medieval comments on Fortune (lasting well into the 16th century with the comments of Erasmus of Rotterdam) described her as unreasonable, with humans having no way of influencing her.Footnote21 Made famous by Carl Orff’s eponymous opera, the Carmina Burana, a collection of 11th–13th-century poems or songs found in manuscripts in the monastery of Benediktbeuren, include two on Fortuna. The paradox of these (mainly Latin) poems with their mostly very secular and pagan-classical contents being preserved in a monastery beautifully captures the contradictions of Medieval elite culture. With the classical image of the deity Fortuna in mind, in constant motion with her feet treading a ball, Song 18 describes her as levis, light: With ambiguous steps she errs about with volubility and never stays in any certain or fixed place. If Fortuna gives a good it is not a durable gift, she will take it away soon, turning the king into the slave (colunum). Fate – sors – is treated as synonym of Fortuna, not, as in Antiquity, her antagonist. Cautioning against ambition, Song 18 states that he who aims high will fall down again.Footnote22 Song 17 (popularised by Orff) is cast in the genre of a plang/plainte or lament, stating that Fortuna, ever-changing like the moon, would as in a gambling game (ludus) inexorably destroy all the good she had previously created, unaffected by virtue and morality (sine mora).Footnote23 As the early Renaissance French author Symphorien Champier (1471–1539) put it:

Fickle Fortune does not always keep her promises. For Fortune is the mother of sadness, of pains and afflictions, and she has no constancy and never remains in one state. Thus, if you ask, they call her the one who is the master of all princes, and [if you ask] a philosopher why he paints Fortune sitting down and on a seat, he will say that this is because Fortune never dwells in one place but is changeable, and for this reason he wants to sit her down so that she would not budge in future.Footnote24

The Muslim world also had inherited some notion of fortune (bakht) and attributed to this an influence on war. Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) noted the decisive role of bakht – rather than, as one might have expected from a Muslim scholar, Allah’s intervention or fate, kismet – in warfare, writing, “There is no certainty of victory in war … Victory and superiority in war come from luck and chance”.Footnote25

Some European thinkers of the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance returned to the Classical idea that human agency could counteract the negative influences of fortune with countermeasures. The fourteenth-century French knight Geoffroi de Charny exhorted fellow-knights to counter the uncertainties and fickleness of fortune with wisdom, reason, and self-discipline.Footnote26 For the earliest modern strategist, Christine de Pizan, writing in France at the beginning of the 15th century, a good prince was to make use of the classical virtues, especially Prudence and Prowess, to help him withstand the vicissitudes of Fortune, including in the context of warfare.Footnote27 “The prince must not underestimate the power of any enemy, however slight it may appear to him”, she wrote in her Book on the Deeds of Arms, for the prince “cannot know what fortune another will have in his favour”.Footnote28 Fortune was thus a dangerous force but the ruler could summon the Virtues to his defence against her mischief.

A century later Niccolò Machiavelli also saw Fortuna as rewarder of wisdom, planning, prudence and precautions.Footnote29 Machiavelli compared Fortuna to a strong river: “when the river is not in flood, men should build precautions by means of dykes and dams, so that when it rises next time it will either not overflow its banks, or if it does, its force will not be so uncontrolled or damaging”.Footnote30 Also, in his view, Fortune could be seized by force and skill. In preparing for war and going to war, he urged good military organization as well as good institutions and planning. Yet he did not see this as sufficient in itself, for “rarely does [success] occur where there is not also good fortune”.Footnote31 On the up side, “fortune is arbiter of half our actions, but that she lets us control roughly the other half”.Footnote32

Organisation, prudent planning, the creation of good institutions were not the only parts of an overall virtù as seen so idiosyncratically by Machiavelli. This virtù only partly converged with the cardinal Christian virtues of Prudence, Courage, Temperance and Justice that we find praised by Christine de Pizan (although Prudence and Courage are certainly qualities Machiavelli admired). Machiavelli’s virtù covers both less and more, in a “union of force and ability” or skill.Footnote33 In Machiavelli’s Prince, virtù is the means by which one can acquire power and the “knowledge and capacity to maintain power”.Footnote34 Having virtù meant being both a lion and a fox: “one needs to be a fox to recognise traps and a lion to frighten away the wolves”. Only this combination provides the skills to survive and fend off Fortuna’s blows, should she prove to be an adversary.Footnote35 Machiavelli adamantly stated that “men can side with fortune but not oppose her, they can weave her warp, but they cannot tear it apart”.Footnote36

Machiavelli argued that Fortuna instrumentalises men, for when she wants to accomplish “great deeds” she chooses a man with the ability to recognize the opportunities she throws at him, and vice versa, if she desires “calamities, she will appoint men who will enable disasters”. She will destroy or “deprive … of all means” those who do not find favour with her. Fortune has the power to blind men or intoxicate them when “she does not want them to oppose her”.Footnote37 Even in favouring a champion, Fortune might play with him capriciously, exposing him to adversity to force him to show his mettle. If Fortune wants to favour a man of virtù, she might for example encourage the growth of his enemies so that “he may vanquish them” through his skills which will bring him a good reputation and glory. The successful prince, like the successful general or strategist, must always arm himself with virtù, protecting himself against the vicissitudes of Fortune, for without such protection in virtù, if fortune decides to turn her back, he is left with nothing.Footnote38

Thus Machiavelli, similarly to Christine de Pizan, emphasised virtù and the wariness of what Fortuna might offer to a power intent of preserving the status quo. Yet Machiavelli also saw the opportunity this would offer the ambitious individual or polity. It is for good reason that the Florentine came to epitomise the philosophy of a prince set on changing the status quo in its favour. Echoing the Latin dictum that Fortune favours the bold, Machiavelli famously also argued that virtù could be used to win the goddess’ favour, so that as a potentially benevolent force – dea bona – she might actually give her support to the daring, the risk-taker, the bold gambler. As Machiavelli saw Fortuna as impressionable, a man possessing virtù could attempt to seduce her. With virtù, craftiness, an ambitious man desiring to improve himself could seize opportunities which Fortune offers.Footnote39 To be a man of virtù, Machiavelli suggested, one had to be prepared to act immorally or at least a-morally, if necessity.Footnote40 Footnote, 41

The Machiavellian idea of the strongman forcing Fortuna to do his will is also echoed on the reverse of a medalFootnote42Footnote, 43 designed and struck for Camillo Agrippa, an architect, soldier, and author on a treatise on arms. It shows a helmeted, spear-carrying soldier violently pulling fortune by her hair, incidentally also illustrating the iconographic transformation of Fortuna, from controlling a rudder or steering wheel to holding a sail, which turns her from a wilful actor to the passive object of the forces of nature (the winds) (). We find the image of the soldier forcing fortune in many later writings; even in the 18th century the Prussian general and military commentator Christian Karl August Ludwig von Massenbach, writing about the Hohenzollern Prince Henry, brother of Frederick II of Prussia, as a military commander, could say that Henry “knew how to conquer fortune by bold marching”.Footnote44 A less brutal rendering of the importance of seizing the moment was expressed at the beginning of that century by the Marshal de Saxe. Following the writings of Polybius, this commander-in-chief under Louis XV, thought that the good commander should have “a talent for sudden and appropriate improvisation”, so that if he “sees an occasion, he should unleash his energies” and take action. “These are the strokes that decide battles and gain victories. The important thing is to see the opportunity and to know how to use it”.Footnote45

An entirely different approach to the factors of chance and risk that went along with Fortuna can be found in the writings of Machiavelli’s contemporary Giacomo di Porcia (1462–1538). Porcia’s was perhaps the first attempt to quantify risk. He approached the question of whether to go to war and give battle by weighing odds: one should calculate one’s own and the enemy’s strength, and thus work out how great one’s own chance of winning might be. But his was not a purely quantitative approach: he argued that one should be mindful of possible strokes of bad luck, such as the possibility of one’s allies defecting.Footnote46 The cautionary approach this implied can also be found in the bequest of Lazarus von Schwendi, a general of the Habsburgs who served them in South Eastern Europe, in Spain and in Central Europe. Cautioning against rash decisions to go to war, he wrote, “one should not be too sure of one’s luck and overly confident but should always fear uncertainty and bad luck in battle”. Indeed, he formulated “the general rule in war that one never accept battles with their uncertain and unfavourable outcome unless there is extreme need or a great and almost certain advantage”.Footnote47,Footnote48

While for Christine de Pizan, prudence was a Christian virtue, for Machiavelli, the domination of Fortuna by virtù had nothing to do with Christianity. Indeed, Christianity could even be seen as an impediment to prudent government. Philip II of Spain with his uncompromising devotion to the Catholic cause stands accused of having been an “imprudent king” for casting prudence aside when his conscience demanded further action.Footnote49 It is not surprising, perhaps, that Schwendi did not get on well with this Spanish monarch in whose service he found himself after the abdication of Philip’s father, emperor Charles V. Philip persisted with his many wars against the Protestant powers of Europe and of course against the Dutch insurgents, in the face of defeats and other disasters. In truly medieval fashion, Philip attributed his relatively rare victories in battle – that of St Quentin in 1557 against the French being the most notable – to divine grace, and he had the Escorial monastery, later his own residence, built as a votive offering to thank God for is victory. His defeats, however, did not lead him to desist but to persist, explaining them in terms of divine punishment for a lack of faith. Thus, after his Armada battlefleet’s assault on England had failed in 1588, he proceeded to build and send out two further armadas in 1596 and 1597. Both enterprises, again, foundered in adverse winds. Justus Lipsius, whose support for Catholicism was at least in part a function of his horror of confessional civil wars, observed Philip’s warfare with disapproval. Agreeing with Livy that the outcome of no affair was less certain than that of war, he advised any prince that, “however much you trust your armed forces, you must not exchange certitude for incertitude”. A classicist through and through, he advised any prince to bear in mind that the “successes you have achieved, or hope to achieve [in war], Fortune can crush in a single hour”.Footnote50 Tommaso Campanella, shortly after Philip’s death, wrote that “[t]he Spanish monarchy is founded upon the occult providence of God rather than upon either prudence or opportunism”.Footnote51

A century after Schwendi, another general of the embattled Holy Roman Empire, the Italian-born Raimondo di Montecuccoli, still viewed Fortune as something that would spring from “order, reasoning about what should be priority and what subordinate”.Footnote52 In deploying one’s forces one should leave nothing to chance: instead, deploying them with care helped guard against fortuna avversa, adverse fortune, in other words, reason and planning could offset adverse fortune.Footnote53 In the tradition of both Christine de Pizan and Machiavelli, Montecuccoli argued that prudent planning and comprehensive preparation would be rewarded. A captain who planned his campaign well would not lack [good] fortune: “Good luck arises from the union of good order [of battle, of the armed forces], of knowledge and of good disposition [configuration of one’s forces]. [If you have this], you will deprive fortune of power [over you] and give it to reason”.Footnote54

Even in the 17th century, however, thinking both about fortune, luck and chance, and any thinking about how to prevent defeat or other military disasters, was still in competition with Christian views of divine intervention or predestination. Writing on how best to conduct warfare during the early reign of King Louis XIV of France, Paul Hay du Chastelet, himself an armchair strategist, still insisted on the importance of fighting only just wars, thus bringing God on one’s side, as “the wars of God are always victorious”; indeed, “God presides over all the events; accident has no power, and is a chimera which the ignorance and blindness of men leads them vainly to conjure up”. One wonders, with that state of mind, why the entire business of war could not in that case be left to God to sort out, and what point there was to human efforts (including his own authorship of a treatise on how to wage war).Footnote55 But the Age of Reason was dawning, and with it, a new approach to chance.

The mathematics of probability vs. Clausewitz’ emphasis on chance

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the French word fortune was increasingly used synonymously with “rich”, and was stripped of its ambiguity.Footnote56 The vagaries of fortune, the play of pure chance, was not in agreement with the thinking of the times. The Age of Reason saw the rise of positivism. Porcia’s approach would be developed further by those hoping to introduce into the art of warfare the quantifications, the mathematics and the equations that had revolutionised physics. But where Porcia had wanted to understand risk and get a handle on it, some thinkers of the Enlightenment wanted to evacuate the nefarious consequences of chance altogether. Marshal de Saxe wrote in his musings about strategy, “war can be made without leaving anything to chance. And this is the highest point of perfection and skill of a general”.Footnote57 Montesquieu wrote:

It is not fortune that dominates the world … There are general causes, either moral or physical, that act within every monarchy, elevating it, or casting it down. All accidents are subject to these causes: and if the hazard of battle, which is to say a particular cause, ruined a state, there was a general cause necessitating that this state perish through a single battle.Footnote58

In other words, bigger trends, overriding causes alone would allow a single battle to make such a difference, not the play of chance. Yet Montesquieu was a precursor of the revival of a Machiavellian notion that the exceptional military leader would be capable of “exploiting fortune”.Footnote59

The Prussian strategist Heinrich Dietrich von Bülow stands out as the most prominent proponent of squeezing out chance by basing strategy on mathematical-geometrical calculations focusing most importantly on logistics.Footnote60 The importance of lines of supplies had not previously been fully understood. Bülow’s work initially became very popular, much like “systems analysis” in 1960s’ American thinking on defence. Having himself been brought up in the Age of Reason with its mathematical predilections, Napoleon claimed in a conversation of 1804 that as far as he was concerned,

Military science … consists of first, calculating all one’s chances [of success], and then to establish exactly, almost mathematically, the part of coincidence [hasard]. You must not make a mistake here, as a decimal point more, or less, can change everything. This shared appreciation of science and coincidence can only come together in the head of a genius, as it is needed wherever there is creation, and certainly the greatest improvisation by the human spirit is that which gives existence to something that is not. Coincidence [hasard] always remains a mystery to mediocre minds while it becomes a reality for superior men.Footnote61

Henri Baron de Jomini famously claimed to have been able to predict Napoleon’s calculations on one occasion, extrapolating from the geographic features of the area through which French forces were moving East that the next great battle was likely to take place near Ulm, and that Napoleon’s columns, marching separately, were most likely to converge and meet enemy forces just to the east of this city. Jomini is in fact the only witness of his own claim that Napoleon was surprised by his prediction.Footnote62 Arguably, this was mainly geostrategic logic, “the art of making war on the map”, as Jomini defined strategy,Footnote63 but as such, it contained a degree of predictability and calculability.

But with the hot-headed period of Sturm und Drang, the reaction against Napoleon’s conquests and the emotionally-charged rise of nationalism, there came a backlash against such a purely quantitative and mathematics-based approach. Already Carl von Clausewitz’s teacher Gerhard Scharnhorst insisted in his lectures that one had to allow for chance and should not hope to eliminate it altogether.Footnote64 Clausewitz ridiculed and dismissed Bülow’s mathematical models, even though they had clearly internalised several of his key tenets (such as, that war is the continuation of politics by other means).Footnote65 Clausewitz and others saw that Napoleon’s genius lay in his coup d’oeil, his ability to judge a situation intuitively and not by any mathematical calculation. Napoleon himself, so clearly blessed by fortune until 1811, proclaimed that success in war was linked to being born a genius who carried within himself something divine. Synthesising Caesar’s self-perception and Machiavelli’s idea of forcing fortune, Napoleon opined that there were no great successes

that are the work of coincidence [hasard] and fortune: they all stem from how things come together [la combinaison] and from genius. One rarely sees great men fail in their most dangerous enterprises. Look at Alexander [III of Macedon], Caesar, Hannibal, the great Gustavus [Adolphus of Sweden] and others, they always succeeded. Is it because they were lucky that they became great men? No, but because they were great men, they mastered luck [le bonheur].Footnote66

Carl von Clausewitz, besides Jomini Napoleon’s other chief commentator, entertained a love-hatred relationship with the French emperor, and devoted much of his writing to analysing his undeniable military genius. On a tactical level, following Machiavelli, Clausewitz postulated that the military genius, not mathematics, must seize any opportunity that presented itself by applying the general’s coup d’oeil to turn it to his advantage. Footnote67 This notion stands in the Kairos/Occasio tradition, the risk-taking tradition, of the interpretation of fortune.

In analysing war as a whole, Clausewitz saw the unforeseeable factor of Zufall, the exact equivalent as Napoleon’s hasard, meaning “accident, coincidence”, as neutral, but hugely important.Footnote68 Zufall could be helpful or unhelpful as permanent part of his famous trinity of violence, Zufall and reason (political purpose). Not only was the occurrence of such an event unpredictable, but it would also interact in unpredictable ways with the other two elements of what he called a curious trinity of factors,Footnote69 and with many other variables besides. Given that one only ever had “imperfect knowledge” of many of these factors, the conduct of war might be “a matter of assessing probabilities” but in fact was a gamble (Spiel). Early on in Book I of On War, Clausewitz gave a nod to the “rules of probability”.Footnote70 These of course can be traced back to Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat in the 17th century. But Clausewitz dismissed purely mathematical calculations of risk and chance as useless.Footnote71 As Alan Beyerchen has demonstrated so brilliantly, Clausewitz held that war could not be compressed into linear equations, was ultimately unpredictable.Footnote72 At best, he opined, of all human occupations, war most resembled a “game of cards”.Footnote73 Presumably what he had in mind is that an observant player will see which cards have been put down and deduce from this, with a degree of risk involved, which cards may still be in the adversary’s possession, and which, depending on the game, might still be available to take up if fortune smiled upon you. “[N]o other human activity”, he mused, “is so continuously or universally bound up with chance (Zufall)”.Footnote74

What this overview points towards is that the exploitation of an opportunity arising in an unforeseen way can benefit a military operation in which one has little to lose and much to gain. In the context of conventional armed forces, this only makes sense at a tactical or operation level, however – and then only if adversaries are prepared to accept such a defeat and will not do everything in their power to reverse it. However successful Napoleon was, his adversaries time and again ganged up on him to prize away his conquests from him and undo his conquests, culminating in his defeats in 1813 and 1815.

Chance and probability

War games became popular in military academies around the turn of the 19th to the 20th centuries.Footnote75 Milan Vego credits the mathematician Georg Venturini (1772–1802), despite his Italianate name probably the scion of a Brunswick family of intellectuals, with having invented a board game known as Königsspiel – the King’s Game – that would be developed further by subsequent generations of military instructors. This became very popular even in Clausewitz’s lifetime. Later combined with staff rides, such games enjoyed a new bout of popularity, it seems, around the time of Prussia’s victorious wars of 1864–1871. By the time Germany pushed Europe into the Second World War, war games in all forms – from exercises involving large numbers of forces to table-top games – were part of the preparation of most German campaigns.Footnote76

In the three successive wars of 1864–1871, Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck played his cards with extreme astuteness when he first, turned European public opinion against Austria when together with Austria the Prussian forces went to war with Denmark in 1864, then found Austria quite friendless when he turned the Prussian army against her two years later, and finally goaded the gormless French Emperor into the emotional reaction to the apparent insult he suffered in the telegram from the King of Prussia which Bismarck leaked to the press in an abridged form. Consequently, it was France that declared war on Prussia and her allies, so that again, public opinion in the other European great powers favoured keeping out of the fray. Consolidating the newly created Germany’s position in Europe was a balance-of-powers game that Bismarck subsequently pursued by diplomatic, rather than violent means, cleverly deflecting the suspicions and animosity of the other powers of Europe away from Germany and towards each other or the Ottoman Empire (or both).

Bismarck the gambler had taken risks, and very successfully, seizing his chances as they came his way, with much astute manipulation on his part. He himself commented on the role of luck in his success: “I do not think I am infallible and concede that I have made mistakes. But I had the good fortune of my enemies making even greater ones”.Footnote77

The eclipse of chance and the rise of destiny

When not attributing his success and the rise of Germany to chance, however, Bismarck attributed it to God’s will.Footnote78 In old age, he mused that “One cannot achieve anything oneself, one can only wait to hear God’s steps echoing in events, and then leap forth to seize the corner of his coat – that is all”.Footnote79 This was in keeping with the late 19th century’s religious revival on the one hand, and the rise of that new secular religion, nationalism, often mixed with the notion of a destiny bestowed upon the many nations each seeing themselves as God’s new chosen people. Harnessed to States’ interests through national narratives taught in schools and propagated on national holidays, nationalists borrowed from the Hebrew Bible via Christianity the narrative of sin, contrition, self-sacrifice and redemption rewarded by triumphant nationhood as a fulfilment of destiny.Footnote80 This brought along with it a transformation of thinking about fortune and chance, leading to greater risk-taking by such nations in pursuit of their higher destiny. This applied to many nations, although only some took it to the extreme of fighting expansionist wars. With the rise of nationalist wars, from the French Revolution onwards, “war ceased to belong to the realm of Fortune and entered the perilous realm of Destiny”, as historian James Whitman has put it.Footnote81

A belief in destiny was inherent also in Marxist-Leninist thinking: thus, Soviet wars had to be won, whatever the cost, as it was the historic destiny of Socialism to prevail. Risk-taking could thus be justified in terms of the faith that it was one’s destiny to prevail ultimately. It is also this thinking in terms of historical inevitability or destiny that is the only explanation of Germany’s attack on the USSR in the summer of 1941, and Hitler’s gratuitous declaration of war on the USA: the blind faith he had and quite successfully spread among his countrymen in the particular destiny of their “master race” allowed emotions and irrationality to prevail over any sober risk assessment, with any favouring the latter being accused of, or even arrested and executed for Wehrkraftzersetzung, eroding the armed forces’ morale.

In other cultures, astrology continued to be an accepted determinant of government business, giving firm guidance for example on the choice of dates for royal marriages, elections, inaugurations of public buildings and many other aspects of public life. Nor did the belief in chance and luck and good or bad fortune disappear from the private spheres of the Western world, as the spread of gambling halls demonstrated in the 19th and 20th centuries, despite the statistical unlikelihood of players winning more than they would lose. Diverse motivations and beliefs lay behind this, from desperation to nonchalant customs among scions of wealthy classes, not necessarily a legacy of notions inherited from Antiquity among the educated.Footnote82

Intermittently, risk taking and the exploitation of opportunities as they arose were seen as something to be encouraged in Western military officers. On the one hand there was the tradition of the Kadavergehorsam, the blind obedience of soldiers and subalterns to commands which would turn them into cannon fodder, associated with the Prussian tradition of Frederick II and extolled as valiant and admirable by poets of the 19th century – the most famous example being Alfred Lord Tennyson’s praise of the pointless slaughter following the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Battle of Balaclava of the Crimean War. Yet contrary to the prudence that was generally counselled by military authors of the 15th to 18th centuries, in the 19th and 20th centuries, Western military doctrine was imbued with often unjustified optimism,Footnote83 as the quick exploitation of chance events brings with it the element of surprise. Surprise is even today seen as one of the “Principles of War” (or what should be called the principles that are assumed to help succeed in warfare) which can be traced back to the Swiss Baron de Jomini and the British General J.F.C. Fuller. They subsequently made it not only into British but also into American and NATO doctrine.Footnote84 By contrast, references to chance or fortune as a factor in war disappeared almost entirely from later 19th century writing about warfare,Footnote85 even though the periodic rediscovery of Clausewitz would lead to a concomitant rediscovery of the uncertainty and unpredictability of the outcome of any war.Footnote86

The German and Austrian generals of 1914 were both less fortunate and less astute in their risk-taking than Bismarck had been. There has been much speculation as to why Germany launched itself into the First World War, given that the balance of forces was stacked against the Central Powers. Stig Förster has argued that risk taking that sought to exploit a last window of opportunity, in the hope of achieving a quick victory before the force balance (and industrial potential of Germany’s Western neighbours) would fully be brought into play against Germany.Footnote87 They miscalculated thoroughly, as it turned out.

Hitler sought to emulate Bismarck’s successive risky moves with his own salami tactics of appropriating territory, first the previously demilitarised Rhineland, then bringing Austria “home into the Reich” without any kinetic opposition on the part of the Austrians, then persuading Britain and France to help Germany take possession of the Sudeten-settled areas of Czechoslovakia, and finally occupying the remainder of Czechoslovakia. But his fifth move was one too many, and he found to his surprise that in gambling on London’s complacency and Paris’ indecision, he had outrun his luck and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s credulity. Despite his success in overrunning Poland and effecting France’s surrender in 1940, in 1941, his bid to get to Moscow in 1941 before the snows, and in response to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, to declare war on the US, defied common sense as the odds were too heavily stacked against Germany.

As was Japan’s decision in December 1941 to attack Pearl Harbor, when in a comparable fashion, it sought to exploit the window of opportunity of eliminating the key American naval forces on Hawaii before the USA fully come around block Japan’s expansionism.Footnote88 In return, the US Navy deliberately took what the commander of the remaining US Pacific Fleet, Admiral C.M. Nimitz, called “a calculated risk” when in May 1942 ordering his “Striking Force” to advance towards Japan to reverse its dominance of the Western Pacific.Footnote89 In this case, taking the risk would pay off, albeit only after three further years of intense fighting.

The Nuclear Age: The instrumentalization of uncertainty

With “calculated risks”, rational mathematics came to the fore again. In the USA, operational/operations research and systems analysis entered into the military domain in the 1940s and 1950s. Heavily statistics-based, it was used even in the Second World War to estimate probability of hitting and thus eliminating important targets in bombing raids. This thinking would then come to underly early nuclear strategy, which was to dominate Western literature on military strategy from the first use of atomic weapons in August 1945.

Early nuclear strategy had as its only tools free-fall bombs dropped from aircraft and susceptible to a very large error probable if given winds, and the possibility of aircraft being shot down if they flew low to enable more precise targeting. To achieve a high hit rate, one had to target big cities – this was the reasoning of early American nuclear strategy, the lesson painfully learned in the Second World War when the alternative (with low-flying bombers) had led to unbearable losses among US aviators.

Having demobilised most of their armed forces after the end of the Second World war, NATO members stood in awe of the not much reduced Soviet forces, now augmented by the manpower of the “satellite” states that were now under Soviet control. After experimenting with meeting like with like – creating very high conventional rearmament goals which in the end its members could not meet – NATO harnessed America’s nuclear power to its defence.

As the Soviet Union developed intercontinental missiles, a new factor of uncertainty was introduced, namely the possibility that Soviet missiles might take out American aircraft or missiles before these could be launched. Uncertainty about the survival of US weapons and of their delivery to target began to feature in deterrence thinking. This possibility was countered by putting missiles on mobile launchers, in hardened silos, or hiding them deep in the oceans aboard submarines. Equally, endless calculations were made as to whether American missiles would hit their predetermined targets on enemy territory, whether their “circular error probables” were small enough to ensure “certain target kills” or had to be compensated for by greater explosive yields. Thus, chance in the “scientifically-controlled” guise of mathematical calculations of probability entered into the equation once more, and in a more mathematical fashion than ever before: what likelihood was there of Western weapons surviving an enemy’s first strike, and in a retaliatory strike reaching their targets?

Moreover, once the USSR with its intercontinental missiles could reach American soil, how likely was it that America would, in extremis, make good its commitment to defend its European allies to the end, and if necessary, with nuclear weapons? This was another uncertainty, regarding the potential fulfilment of the promise that the USA would bring its nuclear forces to bear to defend all members of the Alliance against Warsaw Pact Aggression, if in turn its own cities might be destroyed in turn. This concern would swiftly become central to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s strategic posture.

For deterrence to work, opponents must not be tempted to take a calculated risk, consisting of a good likelihood that the attacked side would rather give in (or surrender some territory) than escalate to nuclear use, if its bluff were called. Chance or calculations of likelihood and possible non-occurrence – is the opposite of predictability, calculability, certainty, factors generally seen as vital to security. The European non-nuclear weapons states wanted as much assurance as possible that America would defend them, if needs be, with nuclear weapons. Yet once Soviet intercontinental missiles could hold American cities at risk, Europeans had their doubts about American extended deterrence, especially when in the early 1960s, the US Administration tried to persuade its European Allies of the virtues of a conventional defence of Europe.Footnote90

The French resolved their own “great debate” on this matter by outright rejecting it extended deterrence: French strategists argued and argue that one cannot rely on another power to risk its own nuclear destruction, by coming to one’s aid with nuclear weapons. The French took the consequence of this and built their own nuclear weapons, and they withdrew from and stayed out of any NATO forum that might give other states (i.e., the USA) any influence over the French nuclear arsenal. The French strategist Pierre M. Gallois, arguably the greatest single influence on France’s nuclear posture, used to explain that deterrence of an attack equalled the product of the terror or terrible punishment that might be triggered by this attack, and the likelihood that it would come: “deterrence = terror x likelihood”, as his formula put it. So even a small likelihood would result in deterrence if the terror of nuclear war loomed.Footnote91 It would work also for a nuclear arsenal smaller than that of the USSR, the French argued: the USSR would not risk a French nuclear attack, even if limited, as it would weaken the Soviet Union vis-à-vis its larger adversary – the USSR. But national nuclear self-defence was more credible, they argued, than US extended deterrence. With the back against the wall, a French President might very well to use nuclear weapons, while the USA would not necessarily trade New York or Chicago for Paris.Footnote92

The British also acquired their own nuclear force, but hedged their bets: while they developed the capacity to use nuclear weapons even if the Americans would not, they staunchly proclaimed their trust in American extended deterrence. Other European powers took their chance, and some actually renounced national nuclear weapons programmes. Three decades of NATO history – from the flight of the Sputnik in 1957 which demonstrated the USSR’s intercontinental missile capacity until the end of the Cold War in 1991 – were spent by NATO members (minus France) and Americans wrangling over the problem as to how to make it look likely that America would use nuclear weapons if European conventional defence broke down under a Warsaw Pact attack. Meanwhile it was looking increasingly likely instead that the Americans would be self-deterred from initiating nuclear war, and that any West European resolve would break down if nuclear weapons were used on their territory.Footnote93

The risk of self-deterrence and lacking resolve was great. But adopting a reasoning much akin to Gallois’ idea of “deterrence = terror x likelihood”, it would suffice to ensure that no enemy could ever be certain that NATO (and above all America) would not use nuclear weapons rather than see NATO’s conventional defences collapse. In 1960, this led Thomas Schelling to argue that this doubt might be mitigated by building flaws into the response mechanism, “to leave something to chance”, to threaten that any conflict might escalate to nuclear use by escaping a government’s rational control.Footnote94 We encounter a similar reasoning in British government documents as early as in 1961, taking the form that the enemy must “never be certain that they would not unleash a major war by an aggression” [my Italics].Footnote95 The awkward formulation crept into declaratory NATO strategy that adversaries had to be left uncertain as to how NATO would react. This is an unfortunate turn of phrase, as it might even imply uncertainty as to whether NATO would react.

This calculation which manifested itself in a concrete – non-nuclear, non-NATO – situation in 1990, when Iraq’s President Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait gambled on America’s inaction.Footnote96 Arguably, this was also a case of uncertainty – uncertainty as to whether anybody other than the Kuwaiti military would react at all to this aggression, and a gambling on the – as he thought – very strong likelihood that the United States, the Soviet Union, the other members of the UN Security Council, and other countries in the area would do – nothing.Footnote97 Saddam miscalculated and lost, as the risks for America were low, nuclear weapons were not involved, the American homeland was not threatened. Moreover, this happened in that short post-Cold War period of convergence of interests and approaches to world policing among the Permanent Five members of the UN Security Council, his aggression did not go unpunished.

As nuclear scenarios receded, it would have made sense also for NATO to retreat from the aim of creating “uncertainty” and to espouse a posture of “certain and overwhelming response” (a non-nuclear one would have largely sufficed, in dealing with a non-nuclear aggressor, but the formulation would also have covered a nuclear context). Yet even after Saddam’s miscalculation of the likelihood of an American (conventional) response, NATO with its strategic concept of 7 November 1991 continued to cling to the formulation that it had to ensure that there was “uncertainty in the mind of any aggressor about the Allies” response to military aggression’.Footnote98 As late as in 1999, we still find the benefits of uncertainty extolled in another NATO Strategic Concept:

The fundamental purpose of the nuclear forces of the Allies is political: to preserve peace and prevent coercion and any kind of war. They will continue to fulfil an essential role by ensuring uncertainty [my emphasis] in the mind of any aggressor about the nature of the Allies’ response to military aggression. They demonstrate that aggression of any kind is not a rational option.Footnote99

A variation of the formula of “uncertainty” is that of creating deliberate “ambiguity”, employed in a less problematic way in the UK’s Integrated Review of 2021. It explained its reasoning for not naming the total number of nuclear warheads to be deployed in future on its Trident- and then Dreadnought-class submarines in terms of a positive “ambiguity”: “While our resolve and capability to do so if necessary is beyond doubt, we will remain deliberately ambiguous about precisely when, how and on what scale we would contemplate the use of nuclear weapons”.Footnote100

Making a virtue of uncertainty in the mind the enemy might seem a simple return of chance to military strategy. Yet in the Nuclear Age, it is also radically different, as radically as nuclear weapons with their destructive power differ from the gun powder which allowed Napoleon or Bismarck to gamble on victory or defeat in his campaigns. Even Napoleon’s most devastating defeat, the 1812 campaign to Russia, did not lead to anything like the destruction of his own country which already aerial bombardment brought Germany and Japan in the Second World War prior to the invention of atom bombs. Taking risks, taking chances, lends itself to the possibility of disasters undreamt of in the context of nuclear weapons. It seems ill advised to give her the potential to bring on an all-consuming Götterdämmerung. It seems more credible (and prudent) by far to complement nuclear deterrence with strong conventional defences that would be infinitely more likely to be used if one is attacked.Footnote101

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Benoît Pélopidas for the idea for this article and both him and Professor Yakov Ben-Haim for critical comments, and Eleonore Buffet Heuser and Margherita Seu for their help with the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘In der Schlacht hat das glück mehr herrschung als die mannheit’. Adam Junghans von der Olßnitz, Krigsordnung zu Wasser und Landt : Kurzer und Eigentlicher Underricht aller Kriegshändel … reviewed by Adreas Reutter von Speyer (Cologne: Wilhelm Lützenkirchen 1595), 113.

2 For examples, see http://pomohahaha.blogspot.com/2013/05/hsbc-ads.html, accessed on 7 IV 2021.

3 ‘chance, n., adj., and adv’. Oxford English Dictionary Online (Oxford: Oxford University Press March 2019), www.oed.com/view/Entry/30418. Accessed 16 April 2019.

4 ‘everything that can go wrong will go wrong’.

5 See for example the statue of Tyche in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, a Roman copy of a Greek original of the 4th century BCE, https://web.archive.org/web/20111011120826/http://www.istanbularkeoloji.gov.tr/web/27-114-1-1/muze_-_en/collections/archaeological_museum_artifacts/statue_of_tyche accessed on 14 IV 2019.

6 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortuna_Redux#/media/File:Fortuna_Redux_dupondius-Didius_Julianus-RIC_0012.png, Wikimedia Commons, accessed on 29 July 2022.

7 Plutarch, Life of Caesar, 38.5; see also Elizabeth Tappan, “Julius Caesar’s Luck”, The Classical Journal 27/1 (October 1931), 3–14.

8 By permission granted on 26 July 2022, order Order # 133446, ID 01613693160 and 01613693161.

9 As depicted in Wolfgang Christian Schneider, “Christus Victor in der Roma Caelestis: Antike Siegesmotivik“, in Anton von Euw & Peter Schreiner (eds), Kaiserin Theophanu, Vol. 1 (Cologne: Locher for the Schnütgen Museum, 1991), 229f.

10 Plautus, Trinummus, 2.2.

11 Flavius Renatus Vegetius, Epitoma de re militari (ca. 387), trans. by N. P. Milner: Epitome of Military Science, 2nd ed. (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press 1996), 116–19.

12 On depictions of Fortuna and their relation to texts, see Aby Warburg, Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, Vol. II, 1 ed. by Martin Warnke with Claudia Brink (Berlin: Akademie 2003).

13 Ausonius, Epigrams, XXXIII. — In Simulacrum Occasionis et Paenitentiae, English translation by Hugh Evelyn White, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann 1921).

14 Giulia Bordignon, Monica Centanni, Silvia Urbini, with Alice Barale, Antonella Sbrilli, Laura Squillaro, ‘Fortuna during the Renaissance: A reading of Plate 48 of Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne’, in Engramma Vol. 137 (August 2016). http://www.engramma.it/eOS/index.php?id_articolo=2975 accessed on 18 April 2019.

15 Bettina Sejbjerg Sommer, ‘The Norse Concept of Luck’, Scandinavian Studies 79/3 (autumn 2007), 275–94.

16 16 Luke 19–31.

17 All examples depicted in Schneider, ‘Christus Victor in der Roma Caelestis’, 244f.

18 For Western traditions of victory and battle, see Beatrice Heuser, ‘Comment une bataille devient-elle mythique ?’, Res Militaris 11/1 (Winter-Spring 2021).

19 Beatrice Heuser, ‘Defeats as moral victories’, in Andrew Hom & Cian O’Driscoll (eds), Moral Victories: The Ethics of Winning Wars (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2017), 52–68.

20 © British Library Board (Additional MS 10294 f. 89), permission granted on 29 July 2022.

21 For examples, see Warburg, Bilderatlas, II.1, passim.

22 A. Hilka, O. Schumann, B. Bischoff (eds), Carmina Burana (Munich: DTV 1979), Cantus 18.

23 Ibid., Cantus 17.

24 Symphorien Champier, Les Proverbes des Princes (Lyon: Guillaume Balsavin 1502), no pagination : « [F]ortune la diverse ne tient pas tousjours ses promesses. Car fortune est la mère de tristesse, de douleurs, et de afflictions ; et en elle na point de constance et ne demeure jamais en vng estre. Et pource quant on demandoit a appelles : lequel estoit maistre de tous les princes et estoit philosophe pourquoiy il boutoit en paincture fortune assise : & en vng siege il disoit que la cause estoit : Car fortune iamais ne pouoit estre en yng lieu mais estoit muable & pour ce la voloit asseoir en son siege affin que ne bougast dorenauant. ».

25 Quoted in Malik Mufti ‘Jihad as Statecraft: Ibn Khaldun’, in Jean Baechler and Jean-Vincent Holeindre (eds), Penseurs de la Stratégie (Paris : Hermann 2014), 72.

26 Geoffroi de Charny, Livre de Chevalerie (c. 1350), trans. Elspeth Kennedy: A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press 2005), Sec. 24, 73–76.

27 Kate Langdon Forhan, The Political Theory of Christine de Pizan (Aldershot: Ashgate 2002), 69, 145, 149, 164f; Beatrice Heuser, ‘Christine de Pizan, the first Modern Strategist: Good Governance and Conflict Mediation, in id. Strategy before Clausewitz (Abingdon: Routledge 2017), 32–47.

28 Le Livre de Fais d’Armes et Chevalerie, trans. by Sumner Willard, ed. by Charity Cannon Willard: The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press 1999), 19.

29 Joachim Leeker, ‘Fortuna by Machiavelli – an inheritance of a tradition?’ Romanische Forschungen, 101/4 (1989), 419.

30 Niccolò Machiavelli, Il Principe (1532) trans as The Prince (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2016), 85.

31 Niccolò Machiavelli, Discorsi (1531), 29, 74.

32 Machiavelli, Principe, 85.

33 Hanna Pitkin, Fortune is a Woman Gender & Politics in the Thought of Noccolo Machiavelli 2nd ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press 1999), 25.

34 Machiavelli, Principe, 55.

35 J. M. Najemy, A Cambridge Companion to Machiavelli (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2010), 196.

36 Machiavelli, Discorsi, 67, 236.

37 Discorsi, 234f.

38 Machiavelli, Principe, 19, 22.

39 Ibid., [Il Principe], 23, 54, 61.

40 Ibid., [Il Principe], 55.

41 https://www.britannica.com/topic/Fortuna-Roman-goddess, accessed on 9 IV 2021.

42 Monica Centanni, ‘Velis Nolisve. Anfibologia nell’anima e nel corpo di un’impresa Sulla medaglia di Camillo Agrippa (Roma, ca. 1585)’, Engramma No. 162 (2019). Image reproduction by courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

43 Elizabeth Thompson, ‘Fortuna during the Renaissance: A reading of Panel 48 of Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne’, Engramma No. 137 (2016), http://www.engramma.it/eOS/index.php?id_articolo=2975 accessed on 8 VI 2021.

44 Quoted in Ferdinand Foch, The Principles of War trs by Hilaire Belloc (London: Chapman & Hall 1918), 17.

45 Maurice de Saxe, Mes Rêveries, Engl Traslation in Thomas Phillips (ed.): Roots of Strategy Vol. 1 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books 1985), 294, 296.

46 Giacomo di Porcia, Clarissimi viri … de re militaris liber; trans. by Peter Betham: The preceptes of Warre set forth by James the Erle of Purlilia (London: E. Whytchurche, 1544), ch. 1, see also ch. 94.

47 Ibid., 47.

48 Lazarus von Schwendi, Freyherr zu Hohen Landsperg etc: Kriegsdiscurs, von Bestellung deß ganzen Kriegswesens unnd von den Kriegsämptern (Frankfurt/Main: Andree Weichels Erben Claudi de Marne & Johan Aubri, 1593), pp. 45-47.

49 Geoffrey Parker, Imprudent King: A New Life of Philip II (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press 2014).

50 Quoted in Nicolette Mout, ‘Justus Lipsius (1547–1606): Fortune and War’, in Arndt Brendecke, and Peter Vogt (eds), The End of Fortuna and the Rise of Modernity: Contingency and Certainty in Early Modern History (Walter de Gruyter, 2017), 73.

51 Quoted in Parker, Imprudent King, 99.

52 Raimondo Montecuccoli, Aforismi dell Arte bellica, in Giuseppe Grassi (ed), Opere di Raim. Montecuccoli corrette, accresciute ed illustrate (Milan: Giovanni Silvestri 1831), Lib. I Cap. II, xi.1, p. 77.

53 Ibid., Lib. I Cap. II, xxviii, p. 115; Lib I Cap. III, xlvi. 3, p. 146.

54 Ibid., Lib. IV Cap. XX, p. 160; for the link between good order and good fortune, see also his Book on Hungary (1673), ibid., 283.

55 Paul Hay du Chastelet, Traité de la Guerre, ou Politique militaire (1668), excerpts in translation in Beatrice Heuser (ed. & trans.): The Strategy Makers: Thoughts on War and Society from Machiavelli to Clausewitz (Santa Monica, CA: ABClio 2010), 109.

56 Florence Buttay, ‘ La Fortune victime des Lumières?’, in Brendecke, and Vogt (eds), The End of Fortuna, 196–200.

57 Maurice de Saxe, Mes Rêveries, Engl Translation in Thomas Phillips (ed.), Roots of Strategy Vol. 1 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books 1985), 298f.

58 Montesquieu: Considérations, 235, quoted in John Stone: “Montesquieu : Strategist Ahead of his Time”, in Journal of Strategic Studies (expected 2023).

59 Montesquieu: Considérations, 128, quoted in Stone : “Montesquieu”.

60 Dietrich Heinrich Frhr von Bülow, Geist des neuern Kriegssystems aus dem Grundsatze einer Basis der Operationen 1st ed. (Hamburg: Benjamin Gottlieb Hoffmann 1799), with further editions following in 1802 and 1805.

61 Quoted in Bruno Colson, Napoléon: De la guerre (Paris: Perrin 2011), 54.

62 F. Lecomte (ed.), Précis politique et militaire des Campagnes de 1812 à 1814: Extraits des Souvenirs inédits du Général Jomini Vol. I(Lausanne: B. Benda 1886), 89.

63 Jomini, Henri de, The Art of War (trans. By G.H. Mendell and W.P.Craighill Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press 1971), 69–71.

64 Gerhard von Scharnhorst, “90. Vorlesungsmitschrift, 1802-1805,” in Private und dienstliche Schriften, ed. by Michael Sikora, Johannes Kunisch and Tilman Stieve, Vol. 3 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht, 2005), p. 471, quoted in Vanya Eftimova Bellinger: “Educating Clausewitz: Gerhard von Scharnhorst’s Influence on Carl von Clausewitz”, MS PhD King’s College London Dept of War Studies, 2022 chapter A2.

65 Dietrich Heinrich Frhr von Bülow, Geist des neuern Kriegssystems aus dem Grundsatze einer Basis der Operationen 1st ed. (Hamburg: Benjamin Gottlieb Hoffmann 1799); id.: Leitsätze des neuern Krieges oder reine und angewandte Strategie (Berlin: Heinrich Frölich 1805); see Arthur Kuhle, Die preußische Kriegstheorie um 1800 und ihre Suche nach dynamischen Gleichgewichten (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2018).

66 Quoted in Bruno Colson, Napoléon: De la guerre (Paris: Perrin 2011), 54.

67 Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege (1832), Michael Howard and Peter Paret (trans. And ed.), On War (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1976), Book I.1.21 and Book I.3.

68 It tends to be translated, inaccurately, as ‘chance’, see the Howard & Paret translation, On War.

69 On War, I.1.28.

70 On War, I.1.10.

71 Dirk Freudenberg, ‘Moderne Risikoanalyseansätze, Simulation und Irreguläre Kräfte – eine kritische Betrachtung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des theoretisch-methodischen Ansatzes des Carl von Clausewitz’, Jahrbuch Terrorismus, Vol. 5 (2011/2012), 359–388; Thomas Waldman, ‘Shadows of Uncertainty: Clausewitz’s Timeless Analysis of Chance’, Defence Studies 10/3 (2010), 336–368.

72 Alan Beyerchen: ‘Clausewitz, Nonlinearity, and the Unpredictability of War’, International Security 17/3 (Winter 1992–1993), 59–90.

73 On War, I.21.

74 On War, I.1.18–21.

75 I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer who has brought this connection to my attention.

76 Milan Vego, ‘German War Gaming’, Naval War College Review 65/4 (Autumn 2012), 106–148.

77 Quoted in Heinrich von Poschinger, Stunden bei Bismarck (Vienna: Konegen 1910), 66.

78 Robert von Keudell, Fürst und Fürstin Bismarck. Erinnerungen aus den Jahren 1846 bis 1872, 3rd ed. (Berlin: Spemann 1902), 488.

79 Quoted in Alexander Scharff, ‘Bismarcks Gestalt und Werk im Streit der Geschichtswissenschaft’, Internationales Jahrbuch für Geschichts- und Geographie-Unterricht 11 (1967), 119.

80 Steven Grosby, ‘The Wars of the Ancient Israelites and European History’, in Athena Leoussi and Beatrice Heuser (eds), Famous Battles and How they Changed the Modern World Vol. 1 (Barnsley: Pen & Sword 2018), Ch. 5.

81 James Q. Whitman, The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP 2012), 23.

82 Pace Esther Eidinow, Luck, Fate & Fortune: Antiquity and its Legacy (London: I.B. Tauris 2011).

83 See e.g., John Kiszely, Anatomy of a Campaign: The British Fiasco in Norway, 1940 (Cambridge: CUP 2017).

84 Brian Holden Reid, ‘Colonel J. F. C. Fuller and the Revival of Classical Military Thinking in Britain, 1918–1926’, Military Affairs 49/4 (1985), 192–97.

85 See for example Sir Edward Bruce Hamley, Operations of War Explained and Illustrated (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons 1872); Captain John Bigelow, The Principles of Strategy, Illustrated Mainly from American Campaigns (London: Unwin 1891, 1894), or Rudolf von Caemmerer, The Development of Strategical Science, trs Karl von Donat (London: Hugh Rees 1905), with no reference to fortune or chance in our sense.

86 See e.g., the occasional reference to “fortune” in a classical sense in Foch: Principles of War, 30, 166f, 289.

87 Stig Förster, ‘Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871–1914’, in Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering and Stig Förster (eds.), Anticipating Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999), 343–76.

88 To what extent Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in ordering this attack articulated his reasoning in any terms comparable to “risk” or “gamble” or “luck” or “window of opportunity” is a question beyond my cultural and linguistic skills to answer.

89 Robert C. Rubel, ‘Deconstructing Nimitz’s Principle of Calculated Risk: Lessons for Today’, Naval War College Review, 68/1 (Winter 2015), 30–46.

90 Beatrice Heuser, NATO, Britain, France, and the FRG: Nuclear Strategies and Forces for Europe (London: Macmillan 1997), Chaps. 1 and 2.

91 Pierre M. Gallois, Stratégie de l’âge nucléaire (Paris: Calmann Lévy 1960), 151. In Gallois’ words: deterrence « peut être assimilée à un produit de deux facteurs dont l’un, purement technique, représente la valeur opérationnelle des moyens militaires utilisés pour exercer la représaille et dont l’autre, subjectif, exprime la volonté de la nation menacée d’user de la force plutôt que de composer. ».

92 This point can be traced originally to André Beaufre, Dissuasion et Stratégie (Paris: A. Colin 1964).

93 Beatrice Heuser, ‘Reassurance, Commitment, Credibility and Deterrence: Squaring the Vicious Circle: Aspects of British and French Nuclear Strategy’, in John Hopkins & Weixing Hu (eds), Strategic Views from the Second Tier: The Nuclear Weapons Policies of Britain, France and China (San Diego, CA: IGGC 1994), 141–53.

94 Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1960), Ch 8.

95 Beatrice Heuser, NATO, Britain, France and the FRG: Nuclear Strategies and Forces for Europe, 1949–2000 (London: Macmillan 1997), 50.

96 Beatrice Heuser: ‘Containing Uncertainty: Options for British Nuclear Strategy’, Review of International Studies Vol. 19 No. 3 (July 1993), 245-267.

97 Saddam Hussein had been misled to think that by a talk he had with the US Ambassador, April Glaspie, which became a misunderstanding that would cost thousands of lives. When Saddam mentioned frontier disputes with Kuwait, the US Ambassador told him to sort this out himself, apparently thinking that Saddam was asking for US mediation. Saddam took this to mean that the US would keep out of any military conflict between Iraq and Kuwait. He could still not be certain that other countries – the other members of the Security Council, for example – would keep out, but he took the chance. Transcript of Meeting Between Iraqi President, Saddam Hussein and U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie (25 July 1990), https://www.globalresearch.ca/gulf-war-documents-meeting-between-saddam-hussein-and-ambassador-to-iraq-april-glaspie/31145, accessed on 20 April 2019.

98 Heuser, NATO, Britain, France and the FRG, Chapter 2, p. 58.

99 ‘The Alliance’s Strategic Concept’ (24 April 1999), Art. 62, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_27433.htm?mode=pressrelease, accessed on 13 IV 2019.

100 Cabinet Office, Global Britain in a competitive age The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (HMSO, 16 March 2021), 79.

101 Admittedly, this does not provide any answer of how to deal with a power that uses its own nuclear deterrence to turn its own territory into an unassailable sanctuary while attacking neighbours not part of any alliance with impunity. In the context of such a scenario, the Russian attack on Ukraine, we are seeing at the time of writing, a subtle game of risk calculations and risk taking on the part of the Western powers. Probabilistic assessments of whether one can get away with certain measures amount to playing with a lighter next to a petrol pump, however high or low the chances of ignition may be.

Bibliography

- Sources

- Plautus: Trinummus (around 200 BC)

- Plutarch: Life of Caesar in Parallel Lives (2nd century BC)

- Flavius Renatus Vegetius: Epitoma de re militari (ca. 387), trans. by N. P. Milner: Epitome of Military Science, 2nd ed. ( Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 1996)

- Ausonius: In Simulacrum Occasionis et Paenitentiae (4th Century AD), English translation by Hugh Evely White, Loeb Classical Library ( London: William Heinemann, 1921).

- Geoffroi de Charny: Livre de Chevalerie (c. 1350), trs. Eslpeth Kennedy: A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry ( Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005)

- Pizan, Christine de: Le Livre de Fais d’Armes et Chevalerie (early 15th century), trs. by Sumner Willard, ed. by Charity Cannon Willard: The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry ( University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999).

- Champier, Symphorien: Les Proverbes des Princes ( Lyon: Guillaume Balsavin, 1502)

- Junghans von der Olßnitz, Adam: Krigsordnung zu Wasser und Landt : Kurzer und Eigentlicher Underricht aller Kriegshändel… reviewed by Adreas Reutter von Speyer ( Cologne: Wilhelm Lützenkirchen, 1595).

- Machiavelli, Niccolò: Il Principe (1532)

- Machavelli, Niccolò: Discorsi (1531)

- Porcia, Giacomo di: Clarissimi viri… de re militaris liber; trans. by Peter Betham: The preceptes of Warre set forth by James the Erle of Purlilia (London: E. Whytchurche, 1544)

- Schwendi, Lazarus von, Freyherr zu Hohen Landsperg etc : Kriegsdiscurs, von Bestellung deß ganzen Kriegswesens unnd von den Kriegsämptern (Frankfurt/Main: Andree Weichels Erben Claudi de Marne & Johan Aubri, 1593)

- Saxe, Maurice de: Mes Rêveries, Engl Traslation in Thomas Phillips (ed.): Roots of Strategy Vol. 1 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1985)

- Montecuccoli, Raimondo: ‘Aforismi dell Arte bellica‘, in Giuseppe Grassi (ed.): Opere di Raim. Montecuccoli corrette, accresciute ed illustrate (Milan: Giovanni Silvestri, 1831).

- Chastelet, Paul Hay du: Traité de la Guerre, ou Politique militaire (1668), excerpts in translation in Beatrice Heuser (ed. & trs.): The Strategy Makers: Thoughts on War and Society from Machiavelli to Clausewitz (Santa Monica, CA: ABClio, 2010)

- Bülow, Dietrich Heinrich Frhr von (1752-1807): Geist des neuern Kriegssystems aus dem Grundsatze einer Basis der Operationen 1st edn. (Hamburg: Benjamin Gottlieb Hoffmann, 1799).

- Colson, Bruno (ed.): Napoléon: De la guerre (Paris: Perrin, 2011).

- Clausewitz, Carl von: Vom Kriege (1832), Michael Howard and Peter Paret (trs. And ed.): On War ( Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976).

- Hamley, Sir Edward Bruce: Operations of War Explained and Illustrated (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1872).

- Bigelow, Captain John: The Principles of Strategy, illustrated mainly from American Campaigns (London: Unwin, 1891, 1894).

- Caemmerer, Rudolf von: The Development of Strategical Science, trs Karl von Donat ( London: Hugh Rees, 1905).

- Foch, Ferdinand: The Principles of War trs by Hilaire Belloc ( London: Chapman & Hall, 1918)

- Gallois, Pierre M.: Stratégie de l’âge nucléaire (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1960).

- Schelling, Thomas C.: The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960).

- Beaufre, André: Dissuasion et Stratégie (Paris: A. Colin, 1964).

- Cabinet Office: Global Britain in a competitive age The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (HMSO, 16 March 2021).

- Secondary Literature

- Bordignon, Giulia, Monica Centanni, Silvia Urbini, with Alice Barale, Antonella Sbrilli, Laura Squillaro.: ‘Fortuna during the Renaissance: A reading of Plate 48 of Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne’, Engramma Vol. 137 (Aug. 2016) http://www.engramma.it/eOS/index.php?id_articolo=2975.

- Centanni, Monica: ‘Velis Nolisve. Anfibologia nell’anima e nel corpo di un’impresa Sulla medaglia di Camillo Agrippa (Roma, ca. 1585)’, Engramma No. 162 (2019), http://www.engramma.it/eOS/index.php?id_articolo=2975

- Eidinow, Esther: Luck, Fate & Fortune: Antiquity and its Legacy (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011).

- Eftimova Bellinger, Vanya: “Educating Clausewitz: Gerhard von Scharnhorst’s Influence on Carl von Clausewitz”, MS PhD King’s College London Dept of War Studies, 2022

- Förster, Stig: ‘Dreams and Nightmares: German Military Leadership and the Images of Future Warfare, 1871-1914’, in Manfred Boemeke, Roger Chickering and Stig Förster (eds.): Anticipating Total War: The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999), pp. 343–76.

- Freudenberg, Dirk: ‘Moderne Risikoanalyseansätze, Simulation und Irreguläre Kräfte – eine kritische Betrachtung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des theoretisch-methodischen Ansatzes des Carl von Clausewitz’, Jahrbuch Terrorismus, Vol. 5 (2011/2012), pp. 359–388

- Grosby, Steven: ‘The Wars of the Ancient Israelites and European History’ in Athena Leoussi and Beatrice Heuser (eds): Famous Battles and How they Changed the Modern World (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2018), Vol. 1, Ch. 5.

- Heuser, Beatrice: ‘Christine de Pizan, the first Modern Strategist: Good Governance and Conflict Mediation, in id. Strategy before Clausewitz (Abindgon: Routledge, 2017), Ch. 3.

- Heuser, Beatrice: ‘Comment une bataille devient-elle mythique ?’, Res Militaris, Vol.11, No. 1 ( Winter-Spring 2021), pp.2–18.

- Heuser, Beatrice: ‘Containing Uncertainty: Options for British Nuclear Strategy’, Review of International Studies Vol. 19 No. 3 (July 1993), pp. 245–267.

- Heuser, Beatrice: ‘Defeats as moral victories’, in Andrew Hom & Cian O’Driscoll (eds): Moral Victories: The Ethics of Winning Wars (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 52–68.

- Heuser, Beatrice: ‘Reassurance, Commitment, Credibility and Deterrence: Squaring the Vicious Circle: Aspects of British and French Nuclear Strategy’, in John Hopkins & Weixing Hu (eds): Strategic Views from the Second Tier: The Nuclear Weapons Policies of Britain, France and China (San Diego, California: IGGC, 1994), pp. 141–153.

- Heuser, Beatrice: NATO, Britain, France, and the FRG: Nuclear Strategies and Forces for Europe (London: Macmillan, 1997).

- Hilka, A., O. Schumann, B. Bischoff (eds): Carmina Burana (Munich: DTV, 1979).

- Keudell, Robert von: Fürst und Fürstin Bismarck. Erinnerungen aus den Jahren 1846 bis 1872 ( 3rd edn. Berlin: Spemann, 1902).