ABSTRACT

Military doctrine is a form of organisational knowledge. Scholars argue that beneath written doctrine lies a set of deeply held beliefs about war and warfare that do not change even if the written doctrine does. This article explores the relationship between written military doctrine, the underlying beliefs about doctrine that govern its interpretation and application, and ultimately how militaries operate. The analysis is based on fieldwork at a NATO division and 33 interviews with commanders and senior staff officers. It suggests a typology that can be used to understand variances in doctrine and operational differences.

Introduction

It is generally accepted that sound doctrine is a critical component of military efficiency. Its purpose to standardise the thoughts of officers who ‘have to think along the same lines to get the machinery to work well’.Footnote1 But when it comes to its subsequent application, the consensus stops. What is at stake is more than disagreement about a word. It concerns the role of doctrine in the planning of, justification for, and ultimately conduct of military operations. For example, Lieutenant General Michael C. Short, who commanded NATO’s air forces in the campaign against Serbia in 1999, was frustrated with how the political leadership interfered in target selection. Air power was used to hit tactical-level Serbian forces in Kosovo and not strategic targets in Serbia, as contemporary doctrine suggested.Footnote2 Another example is the bombing campaign against Iraq in 1991. Scholars have argued that doctrine and not strategy drove operations.Footnote3 In the spirit of this article, these could also be understood as two very different ways of conceptualising what doctrine is and how it should be applied; something to adhere to or depart from. These underlying beliefs about doctrine, its relations to operations and its intended role in the planning and conduct of operations are what I label ‘imaginaries’ in this article.

The British Army’s doctrine primer states that ‘doctrine is not just what is taught, or what is published, but what is believed’.Footnote4 In addition to a formal doctrine, an army might also have an implicit doctrine or theory-in-use.Footnote5 This echoes the argument in Johnston’s ‘Doctrine Is Not Enough’. Johnston argued that to change someone’s mind requires an emotional experience. Therefore, wartime experience rather than peacetime innovation changes an army's corporate culture. Johnston cited the slow integration of armour and infantry into the British Army before World War II as an example where written or ‘formal’ doctrine was available, but not actualised. Thus, written doctrine only has a minor or indirect effect on the actual behaviour of armies. Johnston therefore called for a broader study of ‘corporate culture’ to understand the behaviour of armies.Footnote6 However, little research has been conducted in the field, and the research there does not take the application of doctrine as the analytical object. King, for instance, explored contemporary divisional command without discussing doctrine explicitly.Footnote7 Other sociological studies have discussed how contemporary staff officers seem engaged in a bureaucratic practice where war becomes primarily a managerial problem.Footnote8 One problem is that different militaries, and subsequently cultures, tend to have different doctrines, making it difficult to isolate one variable for analysis. Another is that military doctrines and also operations and exercises are often classified, restricting access. The counterinsurgency era’s use of comparable and publicly available doctrines in somewhat identical situations by somewhat similar organisations led to renewed interest in culture as an explainer for variance or even success or failure in operations.Footnote9 In a study of operational differences in peacekeeping operations in Lebanon, Ruffa shows how some nations chose approaches that emphasised national documents and doctrine and others had a lower perception of threats and related more to the local practices to understand the operating environment.Footnote10 Ruffa suggests that these differences relate to experience, organisation, and norms. In the current literature, such differences are often referred to under the complex term ‘culture’.Footnote11

This paper offers a typology by mapping out what kind of knowledge contemporary military practitioners believe doctrine comprises and how they practice it. It shows how what is typically labelled as culture, and thus complex, can be understood as tangible disagreements on the status of knowledge about war and warfare. This, in turn, governs how operational problems are understood and their possible answers. The article builds on fieldwork in a multinational NATO division and 33 interviews with NATO commanders and senior staff officers. The typology will provide scholars with a tool for understanding ambiguity about military doctrine within the military profession. The article provides a framework for understanding what military practitioners disagree about when they disagree about doctrine.

The article proceeds as follows. First, I briefly review the academic literature on doctrine. Second, I present the science and technology framework I have used to analyse the empirical material. Third, I present the NATO division where I conducted fieldwork, the interviews with commanders and staff officers outside the division, and the methods I used to develop the typology. Fourth, I present the typology, and conclude with a discussion of its implications.

What is doctrine?

Little research takes the application of doctrine as its analytical object. In classical approaches, doctrine is typically considered the dependent variable of external threats or military culture.Footnote12 However, these classic works do not consider the application of doctrine but rather seek to explain why specific doctrines or operational approaches turned out the way they did.Footnote13 This article is interested in how doctrine is actualised in the military organisation.

This article first turns to the scholarly debate about what doctrine is, since it influences how doctrine is applied. Among contemporary scholars, doctrine is generally understood as written manuals developed and used by the armed forces. Jackson defines doctrine as representative of a belief system. He argues that such beliefs have evolved on four levels: the technical manual, the tactical manual, the operational manual, and the military strategic manual.Footnote14

Høiback defines doctrine as ‘institutionalized beliefs about what works in war and military operations’.Footnote15 Such doctrine floats between the three independent forces of rationality, a-rationality (or culture), and authority. Høiback argues that doctrines can take on three functions: as a tool of change, a tool of command or a tool of education. To Høiback, the written doctrine on top of the doctrinal heap is leveraged by somebody in power to do something in the military. To Jackson, a doctrine represents a pre-existing belief system. This disagreement led Høiback to declare that the study of military doctrine is in a ‘pre-paradigm period of speculation’ in which scholars are not discussing the answers to scientific problems, but discussing what the issues are.Footnote16

There is some convergence on doctrine as a form of organisational knowledge or belief system, and what counts as doctrine is usually written or endorsed by an appropriate authority. NATO defines doctrine as:

Fundamental principles by which the military forces guide their actions in support of objectives. It is authoritative, but requires judgement in application.Footnote17

This variation of Fuller’s 1926 definition is quoted at length in both the British Army’s and the US Army’s doctrine primer.Footnote18

The central idea of an army is known as its doctrine, which to be sound must be based on the principles of war, and which to be effective must be elastic enough to admit of mutation in accordance with change in circumstances. In its ultimate relationship to the human understanding this central idea or doctrine is nothing else than common sense—that is, action adapted to circumstances.Footnote19

From this two-fold definition, it could be argued that doctrine is nothing but codified common sense which must be applied subjectively. However, the first sentence states that doctrine should be founded on the principles of war. Fuller believed that knowledge about war could be distilled from history and that common sense in applying doctrine should be based on scientific knowledge. His description of his methods to arrive at these fundamental principles resembles the hypo-deductive method known in the natural sciences. Fuller describes this approach in the following way:

We first observe; next we build up a hypothesis on the facts of our observations; then we deduce the consequences of our hypothesis and test these consequences by analysis of phenomena; lastly, we verify our results, and if no exception can be found we call them a law.Footnote20

It is an old discussion whether positive or objective knowledge can exist in war. It is generally framed as a discussion between the two nineteenth-century military thinkers: Prussian Carl von Clausewitz and Swiss Baron von Jomini. Often in the contemporary military profession, it is framed as a discussion of war as art or war as a science.Footnote21 Alternatively, it may be framed as a dilemma between descriptive or prescriptive doctrine.Footnote22

Within the military domain, doctrine can mean a variety of things: philosophy, software, a written manual of guidance, fundamental principles, best practice, language, vision, tools, or beliefs.Footnote23 These metaphors might capture the military community’s ambiguous attitudes towards doctrine, but they are hardly helpful for an analysis. NATO specifically defines the purpose of doctrine as follows:

The principal purpose of doctrine is to provide Alliance forces conducting operations with a framework of guidance to achieve a common objective. Operations are underpinned by principles describing how they should be planned, prepared, commanded, conducted, sustained, terminated, and assessed.Footnote24

Thus, in the military domain, doctrine can be understood as a folk category used to coordinate action.Footnote25 This standardisation process has consequences for the actual behaviour of armies. Research into the sociology of standardisation shows that there is no causal connection between the way in which things are thought out in the design mode and their actual application in the use mode.Footnote26 Standards, such as doctrine, guidelines, or similar institutionalised beliefs, need translation to fit local needs.Footnote27 This is also the typical military practitioner’s response to scholars’ critique of positivist doctrine. The written manual might have positivist underpinnings, but this does not mean it is applied in that way.Footnote28 Returning to NATO’s definition of doctrine and emphasising the last part, ‘requires judgement in application’, might be understood as a way to channel objective knowledge and subjective judgement into one coherent or pragmatic whole at the point of application.

In sum, there is little agreement on what doctrine is and subsequently how it should be applied since war as art would lead to one way to approach operations whereas war as science would lead to others. To military practitioners, doctrine is a form of organisational knowledge that increases the efficiency and effectiveness of military organisations. What is interesting to the practitioner is application. Therefore, to understand doctrine, the analysis turns to one point of application: the divisional headquarters in a multinational NATO division.

Analysing imaginaries and doctrine at the point of application

I have drawn inspiration from science and technology studies (STS) and, particularly, studies of standardisation and imaginaries.Footnote29 STS scholars aim to understand how material objects and the imaginaries they carry with them co-construct our experience of the world. The role of doctrine is to facilitate coordination and cooperation between different groups; such objects are called boundary objects.Footnote30 Over time, boundary objects are turned into standards and lose their flexibility; what was once conflicted becomes resolved, normalised, and simply the way things are done. It has become black-boxed.

A typical way to open the black box is to notice changes over time and compare how things have been done in the past – or how designers originally envisaged them – with the way in which they are done now, or by observing how people work with and around these objects. Alternatively, such boxes are sometimes broken open when the existing order breaks down.Footnote31

As an example of black-boxing within the military profession, notice the 2009 discussion on using PowerPoint in staff work. US Marine Corps colonel turned academic, T.X. Hammes, argued that ‘PowerPoint is not a neutral tool – it is actively hostile to thoughtful decision-making’.Footnote32 The problem, according to Hammes and others, is that the templates offered in the programme invite us to understand the complex world in terms of hierarchical orderings presented in a bulleted list.Footnote33 Today, most staff officers (or academic faculty) might not even question the applicability of PowerPoint. If they chose to do so, it would require enormous energy and draw attention. Conveying complexity in bulleted lists in PowerPoint has become normalised.

Another example concerns a study of how the US in the 1950s built enough nuclear weapons to set the whole world on fire.Footnote34 In her 2004 study, Eden opened this black box of nuclear damage calculations and documented that after World War II, there were attempts to understand fire damage, but over time this faded away, and the military establishment only calculated blast damage. Two forces were at play: (1) knowledge-laden routines in the form of handbooks that retain and carry over understandings and predictions, and (2) organisational frames, which are specific approaches to solving problems. In this case, structures targeted by nuclear weapons were supposed to be destroyed with blast damage. In the absence of a feedback mechanism, the organisation was never confronted with its predictions, so concerns about fire damage disappeared over time.

STS provides a fruitful approach to study doctrine at the point of application. By noticing how decisions are justified when disorder appears and the organisation struggles to create order, we can understand how these practitioners determine what is important and why. The justifications which they consistently return are what I have used to analyse the different imaginaries.

Research context and data collection and analysis

I conducted fieldwork within a multinational NATO division and followed a one-year training cycle. A division is an army formation comprising 20,000 troops with 400 staff officers at its headquarters and commanded by a major general. The training events were centred around an online course in divisional-level tactics, a one-week planning exercise, and a two-week command post exercise. The division was only partially staffed daily, and staff positions were filled with designated personnel for the main training events. The division had officers from several nations serving on its staff and it officially follows NATO doctrine. This makes it an illustrative case for a multinational NATO headquarters. However, this specific context also means that some findings might not apply to national headquarters, headquarters engaged in actual combat, or headquarters at the strategic or operational levels. The research participants in this study are predominantly army or marine corps personnel, and service differences probably exist.

I was allowed access to the division as an active-duty military officer. The field notes were gathered as an insider in uniform.Footnote35 However, the fact that I was not engaged directly in the staff work allowed me to capture rich data in the headquarters without interrupting the daily flow. Many of the staff officers’ statements were collected while discussing their daily work at their desks in the staff or from observing discussions.

I also conducted 33 semi-structured interviews with senior NATO commanders, staff officers and doctrine writers outside the division, using snowballing sampling to get a perspective from the commander’s seat on the application of doctrine.Footnote36

All the informants in this paper are anonymised. Active-duty personnel are anonymised per default due to military security. Some interviewees did consent to be quoted by name. Still, for the sake of this article, I have chosen to let them remain anonymous, disclosing only their rank and affiliation to help us understand the context. I have assigned each participant a letter do distinguish between them.

In the analysis, I was inspired by grounded theory.Footnote37 I printed field notes and interview transcripts to analyse the data. I marked the text with different colours and wrote codes in the margins. These initial codes originated in the text or from the initial reflections in the field notes. What sparked the analysis was an immediate observation that the staff officers also articulated that multinationalism was difficult because identical written manuals were understood differently. This was hardly visible in the daily work of the staff but became visible when the situation changed, disorder started to show, and when I asked them afterwards how they justified their actions. I put these codes into categories grounded in the text and ordered a range of ‘doctrine is …’ sentences as my initial categories. These were grouped into the five ideal types I present in the findings section.Footnote38

Findings

Whereas scholars point to the importance of written doctrine, I have not recorded one single instance of staff officers in the headquarters who read or consulted written doctrine at any point. Instead, doctrine runs in the background, and the standard operating procedures (SOPs) govern the staff officers’ daily activities. The respondents did refer to doctrinal principles and were eager to discuss doctrine in an abstract form via principles on a whiteboard, in relation to the exercise situation, via scenarios from the general staff course or through military history. The same observation was made in the interviews. This leads me to suggest that doctrine is something that is embodied and known through experience rather than reading and studying. Subsequently, doctrine is performed or translated in military practice. The analysis starts with the observation that the exact same (written) NATO doctrine can be known, understood and, subsequently, performed in very different ways.

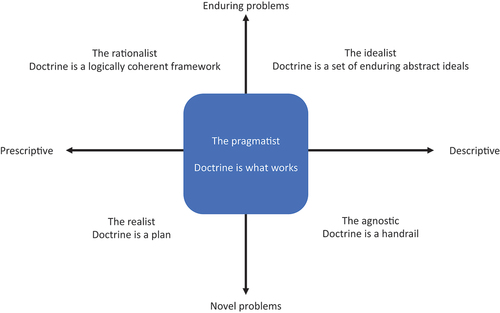

I suggest that the most significant disagreements can be displayed on two axes: (1) whether military problems are enduring or novel, and (2) whether doctrine should be primarily prescriptive or descriptive. Plotted onto a 2 × 2 matrix, four typologies emerge (see ). Extreme positions should be understood as tendencies; several actors perform each ideal type, and, depending on the context, they might even change positions. The last typology is the pragmatist, the ideal type that the profession inspires. I have placed the ideal in the middle of the matrix. Once I have defined the pragmatic ideal, I will analyse its applicability since, I argue, it blurs the discussion of underlying imaginaries. The appeal to pragmatism resembles the grey zone, the ambivalence, and the surface-level order in the material. The agnostic, the pragmatic and the realist are words the respondents themselves used. The rationalist and the idealist are terms borrowed from the field of epistemology.

The doctrinal pragmatist – Doctrine is what works

In lay terms, pragmatism suggests that, in war, the military professional should just do whatever works; doctrine codifies what works. One general articulated the pragmatic character of doctrine in this way:

Doctrine is a common language; it is the shared vision of how the battle can be fought. But if the situation requires the armoured battalion commander to attack through the forest in a single file with 20 meters of spacing between the tanks, then he must do so.Footnote39

This respondent describes doctrine as a shared vision from which one needs to pragmatically divert if the situation requires it. It connotes the duality found in both Fuller’s and NATO’s definitions. It is somewhat objective, but it needs to be applied with judgement. This approach allows the military practitioner to remain flexible and adaptive and avoid doctrinal dogmatism.

In epistemology, pragmatism is a position that assesses the truth of a claim in direct relation to its usefulness. Knowledge is what is useful, tried, and tested.Footnote40 However, unlike other professions, the military professional will by nature rarely exercise the conduct of war and thus lack a feedback mechanism.Footnote41 Wartime conditions are challenging to simulate in peacetime, and any simulation will inevitably be based on how practitioners imagine the battlefield and the adversary in a future conflict. Imagine a pragmatist who has only seen scripted exercises,Footnote42 or a professional military education that emphasises staff procedures, as some respondents argued. In such cases, scenarios and the use of military history will be constructed or curated to teach specific lessons. This is certainly a reality, but we cannot be sure it represents the reality of what future wars will look like. While the appeal to be pragmatic is seductive, its applicability hinges on exercise planners or professional military educational faculty. It risk blurring a debate on imaginaries regarding war and warfare since the exercise reality is confused with the reality of future war. Any simulation will inevitably be based on how we imagine the battlefield. Thus, militaries risk designing exercises and wargames that reify doctrine instead of challenging it. Examples are legion, but the French validation of its doctrine before World War II is perhaps the most illustrative case.Footnote43

The pragmatic ideal is thus a way of black-boxing doctrine. Researchers can surpass the pragmatic ideal and open the black box by asking which reality the respondent refers to when discussing what works. Individual experiences, military history, doctrine, exercises, or a combination? Returning to the respondent above, I asked if the general had ever seen a commander who ordered the armoured battalion to attack through the forest in a single file with 20 meters of spacing between the tanks. When the answer was no, I asked why? This invited the respondent to reflect on what is emphasised and encouraged in training activities and professional military education and, subsequently, how knowledge about war and warfare is justified; he underlined that there is a disagreement not about a principle but about how to operate. In this case, the general admitted that they had never seen such an order because military exercises are scripted with preestablished training objectives that do not allow for deviation.

The doctrinal idealist – Doctrine is a set of enduring abstract ideals

In the upper right corner of the matrix, we find the idealist. The idealist understands the nature of war as enduring. The challenges of war are essentially unchanging, and every tactical or operational manoeuvre can be understood as an imperfect version of an ideal type of operation. To the idealist, it is possible to codify eternally valid, but abstract principles about war. One general reflected on the planning of the first Gulf War:

The battle in the desert war in 1991. The young majors and lieutenant-colonels who drew that plan up drew it from Allenby’s attack on Beersheba in World War I against the Turks. And that was the result of them having learned it at Bloemfontein in the Boer War.Footnote44

The respondent in this interview casually compares three very different battles separated by nearly 100 years, and noted that they are essentially of the same kind. The abstracted knowledge of what the British learned in South Africa in 1900 is applicable 91 years later in Kuwait and Iraq. Indeed, even Hannibal’s pincer movement against the Romans at the battle of Cannae in 216 BC is a model that can be replicated today. To the idealist, military history is illustrative to first tease out and then verify these principles. Detailed examples pollute the pure knowledge that must be conveyed in the doctrine. Historical examples are important to the idealist, but they serve only as illustrations. Detailed examples and the complexity that follows have no place in written doctrine. Idealist doctrine tends to be short and focuses on conveying principles without disturbing elements such as terrain, ground, or something similar. One staff officer explained:

We can discuss doctrine in the abstract, for instance characteristics for penetration or envelopment. The plan answers a task in which doctrine is a part. The risk of providing tactical cases is that they become the textbook solution to doctrine. But doctrine is more than the plan. Plan and doctrine are not synonymous. Doctrine is abstract.Footnote45

The idealist will maintain that they use the abstract framework to understand how the problems they are dealing with are essentially problems of a recurring kind. An envelopment was essentially the same for Hannibal in 216 BC as it is for present-day commanders.

The doctrinal agnostic – Doctrine is a handrail

In the lower right corner is the doctrinal agnostic.Footnote46 The agnostic agrees with the idealist that written doctrine should be succinct, but – unlike the idealist – the agnostic does not think that warfare represent essentially similar problems. To the agnostic, warfare cannot be boiled down to a set of idealised manoeuvres or principles. Any similarity between campaigns is superficial. What characterises war is that all rules can be broken. History is full of examples where this has led to success. The agnostic is empirically focused on subjective judgement. One respondent paraphrased UK Field Marshall Wavell to illustrate the point:

There is nothing fixed in war except a few elementary rules of common sense. And a study of history should be directed not at involving any theory or formula, but at observing what strange situations arise in war, what varying problems face the commander, how all rules may sometimes be broken with successful results, and, especially, the influence of human nature and the moral factor.Footnote47

Codified common sense was also what Fuller argued for. However, Fuller’s interest was precisely to develop this concept into laws of cause and effect. The agnostic would deny its applicability. Instead, the agnostic would argue that practitioners must use military history to emphasise discontinuity; they must train officers to use their professional judgement to understand what is at stake in the specific situation. Returning to the examples of Bloemfontein, Beersheba, and Desert Storm, the agnostic would abstain from trying to understand these as three examples consisting of similar problems but maintain that these examples are inherently different and should be understood independently and in their own context. The purpose of studying them is to train judgement. Since nothing in war is fixed, trying to codify knowledge across contexts is meaningless. The agnostic might even argue that the existence of doctrine could tie commanders’ hands and prevent them from doing what is right in the specific situation. The agnostic does not deny that written doctrine or standards can be useful, but only with respect to prescribing best practice for practical matters. One respondent explained:

The brigade headquarters of which I was Chief of Staff were turned into the regulating headquarters for a divisional river crossing. Now, I had never done a divisional river crossing. I certainly hadn’t planned a divisional river crossing. I think we probably thought about it at staff college. So, what did I do? I went straight to what passed for doctrine in the British Army at that stage which was the First British Corps’ SOPs. I didn’t have to worry about it. It told me what to do.Footnote48

This respondent emphasised that documents that prescribes how certain standard manoeuvres should be carried out are an effective means to organise action. Thus, the doctrinal agnostic would argue that while doctrine at the highest levels cannot and should not be codified, best practices at the lower levels should because there are better ways of conducting a divisional river crossing than improvising. Thus, the agnostic considers doctrine a handrail one can turn to if needed.

The agnostic is also a relentless empiricist willing to challenge even deeply held truisms within the profession since nothing in war is fixed. This response reflected the role of the contemporary division which, in doctrinal terms, is fixed at the tactical level of warfare.

I think that the first thing to ask is what the value of the division is. It seems that it has changed. It is no longer simply a tactical formation. It is now a gearing mechanism between the tactical brigades and the units below and the theatre plan, whatever that might be, above. It’s, therefore, operational level headquarters in most respects.Footnote49

This respondent is not afraid to draw consequences that override common doctrinal approaches based on recent empirical evidence from counter-insurgency operations. Because armies are getting smaller, the units, assets, and tasks that previously were placed at higher levels will are now emerging at the divisional level. Also, while doctrinally, the division is a tactical headquarters, it will probably solve tasks at the operational level, based on very recent empirical data.

The doctrinal realist – Doctrine is a plan

In the lower left corner, we find the doctrinal realist. The realist is concerned with specific problems. The realist is empirically focused, and while abstract doctrinal principles might exist, they are of little interest to the realist. Instead, the doctrine relates to the way in which a specific unit will solve a particular task with the specific means available.

We have a clear and concise threat […]. Others have abstract problems. The difference shows in training, exercising, and planning. It seems the division is trying to learn how to fight a combined arms battle as if we had all the world’s resources. We should work with what we have.Footnote50

This respondent claims that there is too much focus on abstract problems in an ideal type of organisation and not enough focus on the actual situation i.e., how these abstractions should unfold in the specific terrain and with the units available, not with the units that doctrine calls for. The realist will argue that it is necessary and indeed prudent to develop elaborate plans and codify them in writing. Still, the realist does not attempt to say that the conclusions are valid in all cases, just that it is the best possible solution to a specific situation. Another staff officer put it this way.

To me, doctrine is a plan. How will this unit solve its tasks with the means available? How do we integrate the light infantry brigade with the heavy brigade? These are practical questions rather than abstract ones.Footnote51

Historical studies of doctrine might also reveal realist tendencies. During the Cold War, the Danish Army had two primary tasks: to defend the island of Zealand from a seaborne invasion and to dig in near the inner German border and as a part of NATO to stop a Soviet advance. Politically, there was not much room for giving up ground to gain time or to manoeuvre. Thus, the doctrine of ‘grounded defence’ (stenbundent forsvar, ed.) reflected the specific political conditions more than an abstract understanding of warfare in general. A similar argument might be advanced with the development of the Active Defence doctrine in the 1970s and the AirLand Battle doctrine of the 1980s.Footnote52 These were concerned with how the US Army would fight in the German plains against forces from the Warsaw Pact. Prescription is important for the realist, but only when related to the specific situation. The realist does not claim that neither doctrine nor plans can traverse cases, but that each case is unique, and knowledge is valid in a specific situation.

The doctrinal rationalist – Doctrine is alogically coherent framework

In the upper left corner is the doctrinal rationalist. Like the idealist, the rationalist will claim that there are certain enduring ideas about war. Based on this principle, the rationalist will use reason and logic to construct a coherent system or framework that is prescriptive by nature.Footnote53 The rationalist believes that war and warfare are unchanging phenomena, and that positive knowledge about this nature is possible. The approach resembles the method described by Fuller. However, the rationalist will take this approach further and claim that based on such understanding, it is possible to deduce a coherent and logical framework of processes and procedures and thus provide rational answers to tactical problems. Unlike the realist, prescriptive details are not only valid in the specific situation, but valid across cases. Being too doctrinaire is not necessarily a problem since what is needed is an efficient synchronisation of means. One respondent explained:

Often [at the divisional level, ed.], there is not any great liberty to operate. Thus, plans are often an effective synchronisation of means rather than something ground-breaking since time and space are limited means.Footnote54

From the insight that there is no great liberty to operate, the doctrinal rationalist will deduce processes that can ensure that means are effectively synchronised. The rationalist is not inflexible and will, unlike the idealist, continuously update their doctrine, especially at the procedural level where documents are more prescriptive. New knowledge or new proposals will be weighed or analysed against the existing doctrine and only accepted if they comply with the existing framework. The process of writing, updating, and working along standard operations procedures is an approach with rationalist underpinnings.

The rationalist will be frustrated with solutions that do not fit the analytical framework. In discussing a defensive divisional manoeuvre that included a so-called spoiling attack, one staff officer remarked:

It is an analytical breach to commit the heavy brigade early compared to conserving fighting power. We were dependent on that unit later in the fight. That attack should not have been ordered.Footnote55

The respondent in this excerpt places great emphasis on the analysis and its logical conclusions. Based on the analysis, the rationalist will draw normative conclusions. Any manoeuvre should be aligned with doctrine and the rational answers that come from following a method. At the point of application, the rationalist will be focused on procedural approaches, especially the rigour of the decision-making process. Breaches are considered irrational and wrong; at the extreme end, solutions can be criticised even if the commander has issued the order and accepted the risk calculus, as in this case.

To the rationalist, the role of military history is to test and verify the framework that the rationalist has developed. Rational analysis ought to result in the same manoeuvre as what worked in actual wars. Thus, Hannibal’s success at Cannae, the British victory at Bloemfontein and Beersheba, and the US coalition’s success in the Gulf War can be explained through rational analysis that leads back to enduring principles. Similarly, any rational analyst who would be presented with the same factors as Hannibal ought to reach the same conclusions.

According to the rationalists, the same procedures can be used in various contexts, and the increased use of bureaucratic devices in the staff is understood as a sign of professionalism.

Conflicts among typologies

In practice, all these typologies might be present within the same unit because they are rarely articulated. Practitioners who lean towards either extreme will find that their words are falling on deaf ears, they merely assume that they are all operating on the same imaginaries. The biggest problems are found diagonally in the matrix.

An example from the divisional headquarters illustrates several imaginaries at work: during the exercise, a group discussed how a brigade should conduct ‘follow-and-assume’ during an offensive manoeuvre. As the discussion heated, the officer leading it removed the map and drew a principal sketch on a whiteboard of how follow-and-assume should look abstractly.

‘Do we agree on the principle?’ The first staff officer asked.

One objected, ‘We are not talking about principles. We are talking about how this is done in a densely wooded area when the front unit is blocking the available roads’.

The first staff officer responded, ‘Details are for the units on the ground to sort out; if we agree on the principle, I think we can move on’.Footnote56

This can be understood as an example of an idealist and a realist discussing a tactical situation. For the idealist, problems can be abstracted and debated in their ideal forms. Once this is settled, details can be sorted out by others. To the realist, the problem is not a matter of principles; it is a problem of impassable terrain and blocked roads. It is a very concrete problem that does not have an abstract solution but needs a tailored local solution. In this short excerpt, the officers’ words fall on deaf ears. The idealist assumes that the problem has been solved; the realist feels that the problem has not been understood. The discussion of conducting follow-and-assume surfaced again in the after-action review after the exercise. The staff suggested writing a set of tactical standard operating procedures to explain how such manoeuvres should be carried out in the future. The underlying rationalist idea is that prescribing solutions to recurring problems is a good way to overcome problems. However, the validity of that assumption was never discussed, maybe because the standard operating procedures instructed the staff to deal with lessons learned systematically. Each lesson was identified and plotted onto a document that contained a table; one line was allowed for each lesson, and for each lesson, there had to be at least one corrective action.

To be clear, the different imaginaries at play influenced what constituted the problem in the first place and, secondly, the possible and meaningful answers to that problem.

Other conflictive topics at the headquarters include priorities in exercise planning, the commander’s involvement in the planning process, the perceived importance of standard operational procedures and methodology, and even the value of written doctrine. Thus, disagreements on approaching an emergent problem ‘rationally’ or ‘pragmatically’ during the exercise can be understood as a conflict among the suggested typologies because each provides different answers to what rational or pragmatic even means. Furthermore, some of the apparent ‘neutral’ tools that the staff officers use actually frame problems and their solutions in ways that hinder discussion of those assumptions.

A typology; then what?

This article has shown how very different and theoretically incompatible ideas exist in the same organisation and how they affect the problem definition and its possible solutions. Under the headline pragmatism, these imaginaries are seldomly discussed explicitly; however, they are often at the centre of disagreements during the planning process and the conduct of operations. Thus, when military practitioners assume things are a certain way, they are not understanding the world objectively. They have been socialised into a set of practices, procedures, and doctrinal approaches that emphasise one or several sets of imaginaries, and these tend to clash in multinational settings.

The typology offers a way to understand how imaginaries frame practitioners’ understanding of the situation and its practical solutions. One practical approach at a multinational headquarters might be to ensure that planners and commanders are reading the same contemporary doctrine and prioritise training activities that aim to tease out and discuss different ways of understanding and applying this doctrine. These could be wargames, tabletop exercises, or historical examples designed to disrupt order and question deeply held beliefs about war and warfare. The aim should be to acknowledge and understand the existence of differences, since priorities in training or exercises also reflect organisational choices and emphasise some imaginaries over others.

Since doctrine also concerns socialisation, national preferences could have been added to the typologies, but the dataset is too small to support claims of this nature. However, I did find that different typologies existed among officers who should have been socialised similarly. Also, I found that officers could hold different imaginaries depending on the situation. Thus, while these typologies are probably most clearly visible in a multinational context, they also offer a way to discuss the differing approaches to doctrine within nations or services that one might expect to be the same.

The study has a few limitations that might serve as avenues for additional research. The analysis is based on fieldwork in one NATO division and interviews using snowballing sampling. The division was training towards initial operational capacity and, therefore, some of the findings during the fieldwork might be influenced by their specific context and might not necessarily be generalisable. However, the interviews are used as an attempt to counterbalance this. The empirical material does reflect some ambivalence and shows the importance of situatedness. A form of breakdown was needed to notice and discuss imaginaries and priorities related to doctrine. The answers provided were, therefore, context-specific and situated; this is visible if one looks at the quotes I have used to describe the doctrinal agnostic. The agnostic was a minority view among staff officers in the division but more prevalent at higher levels and in interviews that were distanced from the divisional exercises. Thus, the staff officer tasked with a specific subset of the military decision-making process utilises doctrine differently than the commanding general or the lecturer or student in professional military education, even if they are referring to the same document. For this reason, I do not claim that these five typologies exist objectively, nor that they are fixed. Rather, I offer them to make sense of the ambiguity that concerns reading, writing, understanding, and applying doctrine within the military profession.

This study has theoretical and methodological implications for future research of doctrine:

First, the study shows how written doctrine runs in the background. To understand the behaviour of armies, units, or staff, it is not sufficient to study written doctrine since there is no causal link between what is written and practiced. Instead, imaginaries about doctrine, which also entail ideas about what professionalism and rationalism mean, are important factors to be understood as co-constituents in constructing military plans and operations. These, in turn, are best explored as empirical phenomena. However, such studies need not reference a term as complex as culture. The study shows how practitioners disagree on very tangible questions about knowledge of and knowledge in war.

Second, future studies might question how and where these imaginaries emerge and how they are reified within the military practice. Written doctrine might be analysed with the suggested typologies in mind, as well as the ideals and tales of professionalism that groups of military practitioners adhere to. Which military historical examples are hailed as good examples, and what lessons do practitioners draw from them? A related question concerns the use of exercises and, particularly, the use of red teaming or free force-on-force exercises against more scripted or controlled exercise structures. Thus, why and when certain imaginaries are emphasised at the expense of others could be questions worth exploring.

Third, questions of conflict, status, inclusion, and demarcation of professionalism are also at stake within the military profession. Thus, a more classic sociological analysis of whose voices are heard and silenced also adds value to understanding how doctrine is used or developed.

Conclusion

I began this article by asking what we disagree about when we disagree about doctrine. First, I showed that doctrine is considered essential in military practice, but that scholars argue that doctrine is a weak explanation for the actual behaviour of armies. Instead, a set of imaginaries about war and warfare influence the application of doctrine. Second, I have argued that military practitioners tend to consider pragmatism as an ideal. However, in the absence of a feedback mechanism, pragmatics rely on the imagination of exercise planners, which might not resemble how future wars will look. Third, I have argued that military practitioners disagree along two axes: (1) whether military problems are a set of enduring or novel problems, and (2) whether doctrine should be primarily prescriptive or descriptive. This translates into a 2 × 2 matrix that depicts, the doctrinal idealist, the agnostic, the realist, and the rationalist. Researchers can apply this typology to understand the different approaches to doctrine. The point is not that researchers should judge which practice is right or wrong, but that they should endeavour to understand how military professionals make sense of their world.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Søren Riis, Fredrik Henriksen, and Lene Bull Christiansen at Roskilde University for comments on earlier versions of this article. Also, thanks to Major Per Jacob Lindgaard and Anne Roelsgaard Obling from the Royal Danish Defence College and Sam Weiss Evans from Harvard for discussions in the margins of this article. Thanks to the staff officers in the divisional headquarters and the 33 interview participants for sharing their thoughts on doctrine and its use in the military profession. Finally, thanks to the commanding general and his chief of staff for granting access to the divisional headquarters during an entire training cycle.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Søren Sjøgren

Søren Sjøgren is an active duty major in the Royal Danish Army, stationed at the Royal Danish Defence College, and a PhD candidate at Roskilde University.

Notes

1 Harald Høiback, ‘The Anatomy of Doctrine and Ways to Keep It Fit’, Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 187, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115037.

2 Colin McInnes, ‘The British Army’s New Way in Warfare: A Doctrinal Misstep?’, Defense & Security Analysis 23, no. 2 (June 2007): 127–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/14751790701424697; PBS, ‘Interviews – General Michael C. Short | War In Europe | FRONTLINE | PBS’, accessed 22 February 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/kosovo/interviews/short.html.

3 Williamson Murray, War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Chris Paparone, ‘How We Fight: A Critical Exploration of US Military Doctrine’, Organization 24, no. 4 (July 2017): 516–33, https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417693853.

4 Army [UK], ‘ADP Army Doctrine Primer’ (Land Warfare Development Centre, May 2011).

5 Roger J Spiller, ‘In the Shadow of the Dragon: Doctrine and the US Army after Vietnam’, The RUSI Journal 142, no. 6 (December 1997): 41–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/03071849708446210; Eitan Shamir, Transforming Command: The Pursuit of Mission Command in the U.S., British, and Israeli Armies (Stanford, Calif: Stanford Security Studies, 2011).

6 Paul Johnston, ‘Doctrine Is Not Enough: The Effect of Doctrine on the Behavior of Armies’, Parameters 30, no. 3 (16 August 2000): 9.

7 Anthony King, Command: The Twenty-First-Century General (Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

8 Anders Malm, ‘Operational Military Violence: A Cartography of Bureaucratic Minds and Practices’ (Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg, 2019); Dan Öberg, ‘Ethics, the Military Imaginary, and Practices of War’, Critical Studies on Security 7, no. 3 (2 September 2019): 199–209, https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2019.1672482.

9 Austin G. Long, The Soul of Armies: Counterinsurgency Doctrine and Military Culture in the US and UK, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca ; London: Cornell University Press, 2016).

10 Chiara Ruffa, ‘What Peacekeepers Think and Do: An Exploratory Study of French, Ghanaian, Italian, and South Korean Armies in the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon’, Armed Forces & Society 40, no. 2 (April 2014): 199–225, https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X12468856.

11 Elizabeth Kier, ‘Culture and Military Doctrine: France between the Wars’, International Security 19, no. 4 (1995): 65, https://doi.org/10.2307/2539120; David Kilcullen, ‘Strategic Culture’, in The Culture of Military Organizations, ed. Peter R. Mansoor and Williamson Murray (Cambridge, United Kingdom New York, NY Port Melbourne, VIC New Delhi Singapore: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 33–54, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108622752; Shamir, Transforming Command.

12 Barry R. Posen, ‘Foreword: Military Doctrine and the Management of Uncertainty’, Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 159–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115042. Barry R. Posen, ‘Foreword: Military Doctrine and the Management of Uncertainty’, Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 159–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115042.

13 Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany between the World Wars, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1984); Kier, ‘Culture and Military Doctrine’; Jack L. Snyder, The Ideology of the Offensive: Military Decision Making and the Disasters of 1914, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca [N.Y.]: Cornell University Press, 1984).

14 Aaron P. Jackson, The Roots of Military Doctrine: Change and Continuity in Understanding the Practice of Warfare (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2013).

15 Harald Høiback, Understanding Military Doctrine: A Multidisciplinary Approach, CASS Military Studies (London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), 1; Harald Høiback, ‘What Is Doctrine?’, Journal of Strategic Studies 34, no. 6 (December 2011): 897, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2011.561104.

16 Høiback, ‘The Anatomy of Doctrine and Ways to Keep It Fit’, 186.

17 NATO, ‘AAP-06 NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions (English and French)’ (NATO STANDARDIZATION OFFICE (NSO), 2021), 44.

18 Army [UK], ‘ADP Army Doctrine Primer’ (Land Warfare Development Centre, May 2011); Department of the Army [US], ‘ADP 1–01 Doctrine Primer’ (Headquarters Department of the Army, July 2019).

19 Fuller, Foundations of the Science of War, 254.

20 Fuller, 46.

21 Michael Howard, The Lessons of History, Reprinted (with corrections) (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991); Army [UK], ‘ADP Army Doctrine Primer’; Department of the Army [US], ‘ADP 1–01 Doctrine Primer’.

22 Høiback, Understanding Military Doctrine; Eliot A. Cohen and John Gooch, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War (New York : London: Free Press ; Collier Macmillan, 1990); Posen, ‘Foreword’.

23 Army [UK], ‘ADP Army Doctrine Primer’; Geoffrey Sloan, ‘Military Doctrine, Command Philosophy and the Generation of Fighting Power: Genesis and Theory’, International Affairs 88, no. 2 (March 2012): 243–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468–2346.2012.01069.x; Jan Angstrom and J. J. Widen, Contemporary Military Theory: The Dynamics of War, 1st ed. (Routledge, 2014), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203080726; Hærstaben, ‘HRN 010–001 Feltreglement I’ (Hærstaben, June 2016); Eric J. Wesley and Jon Bates, ‘To Change an Army – Winning Tomorrow’, Military Review, June 2020, 6–17; Susanne Lund, ‘Udviklingen og anvendelsen af dansk forsvars landmilitære doktrin’, Militært Tidsskrift, 17 November 2017; Johnston, ‘Doctrine Is Not Enough: The Effect of Doctrine on the Behavior of Armies’; G Stephen Lauer, ‘The Tao of Doctrine: Contesting an Art of Operations’, Joint Force Quarterly 82 (quarter 2016): 7.

24 NATO, ‘AJP-01 Allied Joint Doctrine. Edition E Version 1’ (NATO STANDARDIZATION OFFICE (NSO), February 2017), 1–1.

25 Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, ‘Beyond “Identity”’, Theory and Society 29, no. 1 (2000): 1–47, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007068714468; Cohen and Gooch, Military Misfortunes; Albert Palazzo, From Moltke to Bin Laden: The Relevance of Doctrine in the Contemporary Military Environment, Study Paper/Land Warfare Studies Centre 315 (Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2008).

26 Wanda J. Orlikowski, ‘The Duality of Technology: Rethinking the Concept of Technology in Organizations’, Organization Science 3, no. 3 (1992): 398–427; Stefan Timmermans and Steven Epstein, ‘A World of Standards but Not a Standard World: Toward a Sociology of Standards and Standardization’, Annual Review of Sociology 36, no. 1 (June 2010): 69–89, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102629; Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star, Sorting Things out: Classification and Its Consequences, Inside Technology (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1999).

27 Susan Gal, ‘Politics of Translation’, Annual Review of Anthropology 44, no. 1 (21 October 2015): 225–40, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214–013806.

28 Neville Parton, ‘In Defence of Doctrine … But Not Dogma’, Defense & Security Analysis 24, no. 1 (March 2008): 81–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/14751790801903335.

29 Sheila Jasanoff, ‘Future Imperfect: Science, Technology, and the Imaginations of Modernity’, in Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (University of Chicago Press, 2015), 1–34, https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226276663.001.0001; Donald A. MacKenzie, Inventing Accuracy: A Historical Sociology of Nuclear Missile Guidance, Inside Technology (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1990); Bowker and Star, Sorting Things Out; Timmermans and Epstein, ‘A World of Standards but Not a Standard World’.

30 Susan Leigh Star, ‘This Is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept’, Science, Technology, & Human Values 35, no. 5 (September 2010): 601–17, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624; Lindsay Prior, ‘Doing Things with Documents’, in Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice, ed. David Silverman, 2nd ed. (London: SAGE Publications, 2004).

31 MacKenzie, Inventing Accuracy; Jorgen Sandberg and Tsoukas Haridimos, ‘Grasping the Logic of Practice: Theorizing through Practical Rationality’, The Academy of Management Review 36, no. 2 (April 2011): 24; Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries, Public Planet Books (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004).

32 T.X. Hammes, ‘Essay: Dumb-Dumb Bullets’, Armed Forces Journal, 1 July 2009.

33 Elisabeth Bumiller, ‘We Have Met the Enemy and He Is PowerPoint’, The New York Times, 26 April 2010.

34 Lynn Eden, Whole World on Fire: Organizations, Knowledge, and Nuclear Weapons Devastation, Cornell Studies in Security Affairs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 2004).

35 Robert K. Merton, ‘Insiders and Outsiders: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge’, American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 1 (July 1972): 9–47; Charlotte Wegener, ‘“Would You like Coffee?” Using the Researcher’s Insider and Outsider Positions as a Sensitizing Concept in a Cross-Organisational Field Study’ (Ethnographic Horizons in Times of Turbulence, Liverpool, United Kingdom, 2012).

36 Søren Sjøgren. ‘What Military Commanders Do and How They Do It: Executive Decision-Making in the Context of Standardised Planning Processes and Doctrine.’ Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies 5, no. 1 (November 15, 2022): 379–97. https://doi.org/10.31374/sjms.146

37 Adele E. Clarke, ‘Situational Analyses: Grounded Theory Mapping After the Postmodern Turn’, Symbolic Interaction 26, no. 4 (November 2003): 553–76, https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2003.26.4.553; Tim Rapley, ‘Some Pragmatics of Data Analysis’, in Qualitative Research: Theory, Method & Practice, ed. David Silverman, 3rd ed. (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2010), 273–90.

38 Bente Halkier, ‘Methodological Practicalities in Analytical Generalization’, Qualitative Inquiry 17, no. 9 (November 2011): 787–97, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411423194.

39 General C, personal interview.

40 Peirce, The Collected Papers Vol. V.: Pragmatism and Pragmaticism.

41 Michael Howard, ‘The Use and Abuse of Military History’, RUSI Journal 107 (February 1962); Murray, War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness; Jan Angstrom and J.J. Widen, ‘Religion or Reason? Exploring Alternative Ways to Measure the Quality of Doctrine’, Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 198–212, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115034.

42 Jim Storr, The Human Face of War, Birmingham War Studies Series (London ; New York: Continuum, 2009); Jim Storr, Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century (Havant, Hampshire: Howgate Publishing Limited, 2022); Dan Öberg, ‘Exercising War: How Tactical and Operational Modelling Shape and Reify Military Practice’, Security Dialogue 51, no. 2–3 (April 2020): 137–54, https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010619890196.

43 Robert A. Doughty, The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–1939, Stackpole Military History Series (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2014); Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine; David W. Barno and Nora Bensahel, Adaptation under Fire: How Militaries Change in Wartime, Bridging the Gap (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

44 General K, personal interview.

45 Staff officer A, field notes.

46 I owe the phrase a ’doctrine agnostic’ to General, Sir David Richards (UK army, retired).

47 General E, personal interview.

48 General T, personal interview.

49 Major-general J, personal interview.

50 Staff officer M, field notes.

51 Staff officer G, field notes.

52 Richard Lock-Pullan, ‘How to Rethink War: Conceptual Innovation and AirLand Battle Doctrine’, Journal of Strategic Studies 28, no. 4 (August 2005): 679–702, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390500301087.

53 Department of the Army [US], ‘ADP 1–01 Doctrine Primer’, p. 1–3.

54 Lieutenant-General D, personal interview.

55 Staff officer R, field notes.

56 Fieldnotes.

Bibliography

- Angstrom, Jan, and J. J. Widen. Contemporary Military Theory: The Dynamics of War. 1st ed. Routledge, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203080726.

- Angstrom, Jan, and J.J. Widen. ‘Religion or Reason? Exploring Alternative Ways to Measure the Quality of Doctrine’. Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115034.

- Army [UK]. ‘ADP Army Doctrine Primer’. Land Warfare Development Centre, May 2011.

- Barno, David W., and Nora Bensahel. Adaptation Under Fire: How Militaries Change in Wartime. Bridging the Gap. New York: Oxford UP, 2020.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Inside Technology. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1999.10.7551/mitpress/6352.001.0001

- Brubaker, Rogers and Frederick Cooper. ‘Beyond “Identity”’. Theory and Society 29, no. 1 (2000): 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007068714468.

- Bumiller, Elisabeth ‘We Have Met the Enemy and He is PowerPoint’. The New York Times, 26 April 2010.

- Clarke, Adele E. ‘Situational Analyses: Grounded Theory Mapping After the Postmodern Turn’. Symbolic Interaction 26, no. 4 (November 2003): 553–76. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2003.26.4.553.

- Cohen, Eliot A., and John Gooch. Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War. New York : London: Free Press ; Collier Macmillan, 1990.

- Department of the Army [US]. ‘ADP 1-01 Doctrine Primer’. Headquarters Department of the Army, July 2019.

- Doughty, Robert A. The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919-1939. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2014.

- Eden, Lynn. Whole World on Fire: Organizations, Knowledge, and Nuclear Weapons Devastation. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 2004.

- Fuller, J. F. C. Foundations of the Science of War. London: Hutchinson & Co, 1926.

- Gal, Susan ‘Politics of Translation’. Annual Review of Anthropology 44, no. 1 (21 October 2015): 225–40. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-013806.

- Hærstaben. ‘HRN 010-001 Feltreglement I’. Hærstaben, June 2016.

- Halkier, Bente ‘Methodological Practicalities in Analytical Generalization’. Qualitative Inquiry 17, no. 9 (November 2011): 787–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411423194.

- Hammes, T.X. ‘Essay: Dumb-Dumb Bullets’. Armed Forces Journal, 1 July 2009.

- Høiback, Harald. ‘The Anatomy of Doctrine and Ways to Keep It Fit’. Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 185–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115037.

- Høiback, Harald. Understanding Military Doctrine: A Multidisciplinary Approach. CASS Military Studies. London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013.

- Høiback, Harald. ‘What is Doctrine?’ Journal of Strategic Studies 34, no. 6 (December 2011): 879–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2011.561104.

- Howard, Michael. The Lessons of History. Reprinted (with corrections). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991.

- Howard, Michael. ‘The Use and Abuse of Military History’. RUSI Journal 107 (February 1962).10.1080/03071846209423478

- Jackson, Aaron P. The Roots of Military Doctrine: Change and Continuity in Understanding the Practice of Warfare. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2013.

- Jasanoff, Sheila. ‘Future Imperfect: Science, Technology, and the Imaginations of Modernity’. In Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power, 1–34. University of Chicago Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226276663.001.0001.

- Johnston, Paul. ‘Doctrine is Not Enough: The Effect of Doctrine on the Behavior of Armies’. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 30, no. 3 (16 August 2000): 9. 10.55540/0031-1723.1991

- Kier, Elizabeth. ‘Culture and Military Doctrine: France Between the Wars’. International Security 19, no. 4 (1995): 65. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539120.

- Kilcullen, David. ‘Strategic Culture’. In The Culture of Military Organizations, edited by Peter R. Mansoor and Williamson Murray, 33–54. Cambridge, United Kingdom New York, NY Port Melbourne, VIC New Delhi Singapore: Cambridge UP, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108622752.

- King, Anthony. Command: The Twenty-First-Century General. Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge UP, 2019.

- Lauer, G Stephen. ‘The Tao of Doctrine: Contesting an Art of Operations’. Joint Force Quarterly 82 ( quarter 2016): 7.

- Leigh Star, Susan. ‘This is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept’. Science, Technology, & Human Values 35, no. 5 (September 2010): 601–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624.

- Lock-Pullan, Richard. ‘How to Rethink War: Conceptual Innovation and AirLand Battle Doctrine’. Journal of Strategic Studies 28, no. 4 (August 2005): 679–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390500301087.

- Long, Austin G. The Soul of Armies: Counterinsurgency Doctrine and Military Culture in the US and UK. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca ; London: Cornell UP, 2016. 10.7591/9781501703911

- Lund, Susanne. ‘Udviklingen og anvendelsen af dansk forsvars landmilitære doktrin’. Militært Tidsskrift, 17 November 2017.

- MacKenzie, Donald A. Inventing Accuracy: A Historical Sociology of Nuclear Missile Guidance. Inside Technology. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1990.

- Malm, Anders. ‘Operational Military Violence: A Cartography of Bureaucratic Minds and Practices’. University of Gothenburg, 2019.

- McInnes, Colin. ‘The British Army’s New Way in Warfare: A Doctrinal Misstep?’ Defense & Security Analysis 23, no. 2 (June 2007): 127–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14751790701424697.

- Merton, Robert K. ‘Insiders and Outsiders: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge’. American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 1 (July 1972): 9–47.10.1086/225294

- Murray, Williamson. War, Strategy, and Military Effectiveness. New York: Cambridge UP, 2011.

- NATO. ‘AAP-06 NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions (English and French)’. NATO STANDARDIZATION OFFICE (NSO), 2021.

- NATO. ‘AJP-01 Allied Joint Doctrine. Edition E Version 1’. NATO STANDARDIZATION OFFICE (NSO), February 2017.

- Öberg, Dan. ‘Ethics, the Military Imaginary, and Practices of War’. Critical Studies on Security 7, no. 3 (2 September 2019): 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2019.1672482.

- Öberg, Dan. ‘Exercising War: How Tactical and Operational Modelling Shape and Reify Military Practice’. Security Dialogue 51, no. 2–3 (April 2020): 137–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010619890196.

- Orlikowski, Wanda J. ‘The Duality of Technology: Rethinking the Concept of Technology in Organizations’. Organization Science 3, no. 3 (1992): 398–427.10.1287/orsc.3.3.398

- Palazzo, Albert. From Moltke to Bin Laden: The Relevance of Doctrine in the Contemporary Military Environment. Study Paper/Land Warfare Studies Centre 315. Canberra: Land Warfare Studies Centre, 2008.

- Paparone, Chris. ‘How We Fight: A Critical Exploration of US Military Doctrine’. Organization 24, no. 4 (July 2017): 516–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417693853.

- Parton, Neville. ‘In Defence of Doctrine … but Not Dogma’. Defense & Security Analysis 24, no. 1 (March 2008): 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14751790801903335.

- PBS. ‘Interviews - General Michael C. Short | War in Europe | FRONTLINE | PBS’. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/kosovo/interviews/short.html

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. The Collected Papers Vol. V.: Pragmatism and Pramaticism. Edited by Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss, 1934. https://www.textlog.de/7658.html.

- Posen, Barry R. ‘Foreword: Military Doctrine and the Management of Uncertainty’. Journal of Strategic Studies 39, no. 2 (23 February 2016): 159–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1115042.

- Posen, Barry R. The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1984.

- Prior, Lindsay. ‘Doing Things with Documents’. In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice, edited by David Silverman, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications, 2004.

- Rapley, Tim. ‘Some Pragmatics of Data Analysis’. In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method & Practice, edited by David Silverman, 3rd ed., 273–90. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2010.

- Ruffa, Chiara. ‘What Peacekeepers Think and Do: An Exploratory Study of French, Ghanaian, Italian, and South Korean Armies in the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon’. Armed Forces & Society 40, no. 2 (April 2014): 199–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X12468856.

- Sandberg, Jorgen, and Tsoukas Haridimos. ‘Grasping the Logic of Practice: Theorizing Through Practical Rationality’. The Academy of Management Review 36, no. 2 (April 2011): 24.10.5465/AMR.2011.59330942

- Shamir, Eitan. Transforming Command: The Pursuit of Mission Command in the U.S., British, and Israeli Armies. Stanford, Calif: Stanford Security Studies, 2011.10.1515/9780804777704

- Sloan, Geoffrey. ‘Military Doctrine, Command Philosophy and the Generation of Fighting Power: Genesis and Theory’. International Affairs 88, no. 2 (March 2012): 243–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01069.x.

- Snyder, Jack L. The Ideology of the Offensive: Military Decision Making and the Disasters of 1914. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Ithaca [N.Y.]: Cornell UP, 1984.

- Spiller, Roger J. ‘In the Shadow of the Dragon: Doctrine and the US Army After Vietnam’. The RUSI Journal 142, no. 6 (December 1997): 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071849708446210.

- Storr, Jim. Something Rotten: Land Command in the 21st Century. Havant, Hampshire: Howgate Publishing Limited, 2022.

- Storr, Jim. The Human Face of War. Birmingham War Studies Series. London ; New York: Continuum, 2009.

- Taylor, Charles. Modern Social Imaginaries. Public Planet Books. Durham: Duke UP, 2004.

- Timmermans, Stefan and Steven Epstein. ‘A World of Standards but Not a Standard World: Toward a Sociology of Standards and Standardization’. Annual Review of Sociology 36, no. 1 (June 2010): 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102629.

- Wegener, Charlotte. ‘“Would You Like Coffee?” Using the Researcher’s Insider and Outsider Positions as a Sensitizing Concept in a Cross-Organisational Field Study’. Liverpool, United Kingdom, 2012.

- Wesley, Eric J., and Jon Bates. ‘To Change an Army - Winning Tomorrow’. Military Review, June 2020, 6–17.