ABSTRACT

Through interviews with student participants and evidence submitted to earn digital badges, a number of indicators suggest that a religious school’s digital badges can provide opportunity to strengthen religious identity. In particular, student interviews and evidence supplied for the completion of learning objectives for digital badges indicate increases of religious salience (compared to secular practices), religious commitment within a community, and self-esteem based on religious identity. Recommendations are made for ongoing and future religious badge implementations on how to strengthen religious identity while meeting the requirements of authentic, quality assessments.

1. Introduction

While researchers continue to study and evaluate the potential benefits and challenges of novel educational technology on secular learning, research on emerging technology in religious education has been mostly limited to distance learning and online communities (Wyche et al. Citation2006). This research dichotomy exists despite emerging technologies consistently being used to provide new learning opportunities that could be applied religious learning goals (Campbell Citation2012).

One of these emerging technologies, digital badges are defined as a symbol of an accomplishment or skill (Peer 2 Peer University and Mozilla Foundation Citation2011) that functions as public representations of assessed knowledge (Plori, Carley, and Foex Citation2007). The symbol can range in both the type and range of impact and meaning (Halavais Citation2012). In addition, situativity theories of cognition suggest that the meaning of a public representation of learning, a symbol, is dependent on the interactions between systems and people (Greeno and Moore Citation1993). Because of the variability of these factors, it is difficult to choose one digital badge as an exemplar.

However, research on digital badges does inform us of the characteristics of effective badge construction. Ahn, PellicAbramovichSamueone, and Butler (Citation2014) suggest that badges can be considered as a means to motivate students to learn, provide feedback for learning opportunities, or exist as a credentialing mechanism. Prior research on digital badges (Davis and Singh Citation2015; Reid, Paster, and Abramovich Citation2015; Wardrip et al. Citation2014) suggests that students who pursue digital badges for educational goals will seek out badges that motivate, provide feedback, and credential their learning. Students who earn digital badges are motivated to learn because they perceived badges as fun and novel compared to traditional schooling. Students expressed a preference for badges that provide feedback through recognizing student learning or skills. Additionally, students recognized the credentialing value of badges by noting how a badge should be associated with both short-term such as immediate rewards and long-term goals such as identifiable benefits.

While rites-of-passage (e.g. Confirmation, Bar Mitzvah, Upanayana) can be steeped in practice and tradition, and provide motivation, feedback, and credentialing to strengthen a religious, ethnic identity (Scott Citation1998), they do not offer the level of detail typical of modern assessments. Modern assessments such as standardized tests, despite being built on sophisticated psychometric theory, are likely ill-suited to religious education because of a perceived inauthenticity; no one worships with multiple-choice questions. But digital badges represent a modern assessment that could be integrated into religious education and ostensibly provide motivation, feedback, and credentialing for religious learning that is under assessed, such as daily religious practice. This assessment could then build and support religious ethnic cultural identity, a fundamental goal of religious curricula.

To determine if digital badges can function as assessments that strengthen religious, ethnic identity, we examined the badge programme of a Jewish temple’s after-school programme. While it is important to note that religious education can have significantly different learning goals and curricula depending on where it exists, we use the term to indicate a learning goal that is created through religious practice. Consequently, that is why we chose a Jewish temple’s after-school programme as our research site.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Digital badges

Knowing that assessments can have a large impact on learning outcomes (Black and Wiliam Citation1998), digital badges fit many current, theoretical models of assessment. Badges can provide summative assessment by being awarded for mastery of a learning goal. A badge can also provide formative assessment by indicating how earning it is part of a larger learning pathway or trajectory (Higashi, Shoop, and Schunn Citation2012) leading to mastery of complex knowledge. Taken in aggregate, digital badges can support quality assessment practices by providing data that can help improve reliability and validity. For example, instructors can ensure that a single badge earned by multiple learners is correctly representing learning by examining the evidence submitted by learners to earn the badge. Badges can support authentic assessment through integration in a learning ecosystem, serving as a credential grants a privilege in a school. For example, a badge for digital literacy could grant unsupervised computer usage in a library. Digital badges can provide multiple incentives for students to engage in learning opportunities such as recognition provided by a badge or by earning more badges than peers. And because badges are publicly displayed, they can spur discourse on the learning that is being badged.

There are a few examples of digital badges in formal educational settings. For example, Wardrip et al. (Citation2014) documented student motivation for earning badges in a middle school. The school created badges to recognize skills that were not being explicitly recognized in their classes (e.g. leadership, teamwork). In a follow up study, researchers documented how the badging system provided information that the teachers could use to inform instruction, like what the students were interested in outside of school (Wardrip et al. Citation2016). Moreover, research has explored how digital badges in a school can motivate students (Boticki et al. Citation2015), provide feedback, and serve as credentials (Abramovich Citation2017). In informal learning, such as after-school programmes, research has similarly looked at the ways in which digital badges can support motivation in learning as well as guide learning pathways (Davis and Singh Citation2015).

It is not surprising to note that there is little research on digital badges in religious education; emerging educational technologies are often implemented in educational settings before learning scientists have a chance to study them in depth. However, it is important to note that absent from all research on digital badges is whether badges alter or improve cultural or ethnic identity, despite the known importance of culture and ethnicity to educational outcomes (Ogbu Citation1992). This absence of research is a critical deficit to the use of digital badges in religious education, since a badge would have little to no value to religious education if it hampered or prevented religious identity.

2.2 Religious ethnic identity

Before continuing, it is important to reveal our framework of culture, ethnicity, and identity. Although common discourse continues to conflate the terminology, there are clear differentiations between concepts of culture and ethnicity. Culture can be defined as a set of values, a set of outcomes, or a set of being (Straub et al. Citation2002). Ethnicity is defined as used in reference to groups that are characterized in terms of a common nationality, culture, or language (Betancourt and López Citation1993). A student’s identity is partly defined by their ethnicity and culture (Ethier and Deaux Citation1994). While we acknowledge that these distinctions have used in some research contexts, we have blended these concepts for pragmatic purposes – a key goal of religious education is to have someone identify as part of the religion, infusing religion into their culture and ethnicity.

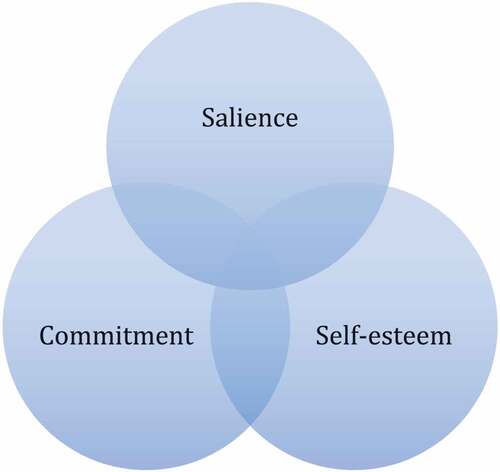

White and Burke (Citation1987) define ethnic identity as a shared understanding of an ethnic group. Examples are African Americans, Native Americans, and Jews who, to varying degrees, share an understanding of what it means to have that identity or aspects of that identity. These shared perceptions are the result of levels of ethnic identity salience, commitment to the ethnic identity, and self-esteem associated with the ethnic identity. In , we provide a visual model of the development of ethnic identity. A firm sense of identity might be captured at the convergence of the three elements – at the centre of the diagram. However, identity often emerges and evolves; at times, one might have higher levels of commitment and salience but lower levels of self-esteem. Thus, analytically, this perspective can be used to describe an individual’s ethnic identity with respect to a group at a point in time, or show meaningful shifts over time as one’s identity evolves.

An individual’s level of salience of their ethnic identity refers to invoking it at certain levels. If being Jewish has low salience to someone then they may say something like ‘Well, I don’t really do anything Jewish but I light a Menorah for Chanukah when I visit my parents’. In this example, the quote indicates that the individual does not participate in Jewish ritual unless it is at a time that they feel strongly compelled to do so. A level of salience can predict how often someone invokes his or her ethnic identity. If someone has a high salience of Jewish identity then they might wish to talk about their celebration of Chanukah even in settings where there are no other Jews.

Commitment to an ethnic identity is defined as the scope and range of how an individual’s ethnic identity governs relationships with others. In other words, the level and number of an individual’s relationships that involves ethnicity will predict commitment to that said ethnicity. For example, an individual’s relationship with their spouse or partner may involve religious practices (e.g. celebrating a holiday together, discussing how to teach their children about religion) which then strengthens their individual religious identity – even if the spouse or partner is not of the same religion or culture (Bystydzienski Citation2011).

Self-esteem of ethnic identity refers to the evaluation of one’s self based on ethnicity. An individual can evaluate their ethnicity based on group association. For example, if someone who is Jewish perceives the Jewish people as admirable, they are more likely to invoke their Jewish ethnicity. Individuals can also evaluate their ethnicity based on individual role. For example, a Jewish parent can compare their skills or knowledge as a parent to how they believe Judaism guides parenthood. If they believe there are similarities, then they are more likely to identify as a Jew because they also identify as a Jewish parent.

For example, Jewish educational organizations are concerned about increasing students’ Jewish identity. We also suggest this is true for other minority groups, religious and otherwise, who wish to use education to strengthen student identity with their respective culture and identity (Tsethlikai and Rogoff Citation2013). For the purposes of this research study, we define Jewish identity as a combination of Jewish ethnic and cultural identity that manifests in both religious and secular practices. Consequently, when we refer to ethnic-cultural identity in our analysis, we are suggesting a singular concept that is a blend of ethnic and cultural identity where the individual concepts become pragmatically indistinct.

If an individual’s levels of salience, commitment and self-esteem of their ethnic-cultural identity rise then so will overall ethnic-cultural identity. Knowledge of religion does not alone predict the use of that knowledge. For religious education, increasing ethnic-cultural identity is as important as learning religious dogma in that a religious identity is a necessary factor for exercising that dogma. Using the concept of ethnic-cultural identity also has research value in that it reveals the challenge of measuring these concepts. There is little research that focuses on measurement of identity that is a result of culture and ethnicity. Rather than identify the primacy of a specific type of measurement, we have adopted a theoretical framework of ethnic-cultural identity that could be used as the basis of a coding scheme for determining if individuals recognized the impact of a digital badge on their religious identity.

2.3 Digital badges and ethnic-cultural identity

If badges are to be successfully used as an assessment tool in religious education, then it is also important to consider what research evidence exists on how assessment impacts ethnic-cultural identity. An assessment-based stereotype threat can lead to lower performance in standardized tests (Steele and Aronson Citation1995). Assessments can also fail to perform accurately if they have ethnic or cultural relativism (Gallimore and Goldenberg Citation2001).

Consequently, many approached to addressing ethnicity in assessment has been to attempt to design an assessment that can be applied to all students. Perhaps the most famous example is the IQ test, which was originally designed to be a universal measure of intelligence (Gipps Citation1999). However, research later revealed that this test was still susceptible to cultural or ethnic relativism. Another approach to addressing ethnicity in assessments is to compensate by adding cosmetic features to standardized instruction. For example, this could involve removing unfamiliar vocabulary for specific cultures from a standardized test. But simply adding language that is familiar to a particular minority group does not address any cultural imbalances in an assessment. A classic example is the study of children in favelas (i.e. poor neighbourhoods, slums) in Brazil, who were capable of complex mathematics in their work but incapable of transferring that knowledge despite attempts to use culturally relevant language (Carraher, Carraher, and Schliemann Citation1987).

Missing from the aforementioned attempts to address ethnicity and culture in assessment is a belief that formalized assessment practices can benefit from an incorporation of ethnicity. Assessment reformers may argue that it is practically impossible to design an assessment that is culturally agnostic, but this framing still suggests that assessments would ideally be independent of ethnicity or culture. Ignored is the possibility that these types of assessments could benefit students if ethnic identity was incorporated rather than addressed. Boykin (Citation2014) notes that there is advantage in incorporating ethnicity and culture in assessment in that it adheres to a human capital view where educators should build on and strengthen people’s identity within their ethnicity, providing formative assessment within their cultural identity. The Gordon Commission (Citation2013), in their technical report outlining the potential for twenty-first-century assessment, calls on educators to further address how cultural identity can be given a considerably greater priority in inquiries concerning assessment in education. If badges are to be used for effective assessment of learning – including motivation, feedback, and credentialing – then they should also address the ethnic and cultural identity of learners.

2.4 Badges in Jewish education

The increased use of digital badges in secular education has also serendipitously occurred in Jewish education (Wilensky Citation2015). Both Jewish day schools and Jewish teacher professional development have successfully used digital badges as a way to provide feedback and motivation for learning that is often ignored by traditional assessment structures. For example, a day school can use a digital badge to recognize skills (e.g. digital literacy, public speaking) or values (e.g. charity, supporting peers) that are not recognized by grades (i.e. marks) or standardized tests. Professional development for Jewish educators can use digital badges to support personalized learning objectives, allowing teachers to better integrate the professional development with their teaching practice.

However, Jewish education is different from secular education in that the goal is to build Jewish identity. Jewish education is designed to teach Jewish history, ritual, and spirituality in order for Jewish people to become more knowledgeable of all things Jewish. While many Jewish educational organizations have different values, priorities, and methodologies, they are all similar in that they aim to strengthen Jewish identity among learners.

The aims of Jewish education thus present different challenges than those typically addressed by the use of digital badges. Digital badges are often used in setting where additional assessment and motivation would have a positive impact on learners. Digital badges for Jewish education must enable strengthening of Jewish identity while also providing quality motivation, feedback, and credentials for specific learning goals. The study of digital badge systems designed for Jewish education thus provides an opportunity for determining if digital badges can function as assessments while also building and supporting ethnic identity.

2.5. Research question

We conducted a study on a digital badge system at a Jewish, supplementary school that had recently deployed digital badges as an optional activity for its students. Our research question was ‘Can digital badges strengthen religious ethnic-cultural identity in a religious education setting?’

3. Setting and methods

To address our research question, we investigated the digital badge system of a supplementary religious school (i.e. Sunday School) at a Jewish temple located in a large city on the east coast of the US. At its launch in September of 2014, the badge system offered 33 badges in a range Jewish educational goals. Information and submission of evidence to earn a badge, as well as storage of the digital badge (so it could be referenced later) was through a customized website specializing in allowing organizations to issue digital badges for educational purposes.

To earn a badge, students of the religious school would choose from 508 badge subtasks (each associated with a specific badge), called missions. Each mission was designed to be an intermediate step toward completion of the learning goal represented by a badge. For example, the Oh the Drama! mission, where one had to write a script depicting a bible story, was worth five points. A total of 10 points would earn a student the Tree of Life badge for demonstrating knowledge and a personal connection to the bible.

Students were strongly encouraged to work on badge missions with their families. This was to both encourage family involvement in student learning (e.g. parents would know what students are learning) and continue the temple’s goal of whole family education. Badge missions that required family interaction were designed to be educative for all participants. For example, a badge awarded for knowledge of Jewish history included a mission where a student (likely a second grader) would select a family religious heirloom and describe what it means to them. Not only could the student have learned something about their family’s Jewish identity, but family members would likely need to be involved in relaying the story of the heirloom, potentially strengthening their identity also.

By the end of the first year of the badge programme, 144 badges were issued with 33% of students at the school earning at least one badge, and 50% of all students completing at least one badge-based mission. The school considered this level of participation in the first year a success, especially since students were not required to participate in the badge programme nor is the school itself required religious practice. Students chose to participate in the badge programme, chose which missions and badges they wanted to earn, and chose the manner of evidence they supplied to earn each badge.

4. Data and analysis

The data used to address the research question were of three types. First and primary, transcripts of student interviews about their experience with the badge system served to address the question. Seven students were interviewed, representing second through fifth grades (i.e. school years). The interviews were transcribed verbatim. The students interviewed were selected based on their level of participation and their willingness to reflect on their experience. The interview protocol was semi-structured in order to allow for digressions and probing where saliency was found in students’ responses (Rubin and Rubin Citation2011). In addition, evidence that the students provided to earn their badges provided both a source of data around students’ identity development as well as background to inform the interviews with students. Finally, each interviewee provided one badge and related evidence to earn the badge to provide a more complete description of the context. The badge system was offered through the temple’s website, where students, teachers, and parents could view each badge and the evidence associated with earning a badge. Written consent to participate in the study was obtained from student, parents, and teachers.

For analysis, the transcripts, student evidence and artefacts were consolidated and read by the lead author. Then, the consolidated data were coded for evidence of ethnic identity development based on White & Burke’s framework of salience, commitment, and self-esteem. In particular, this analysis was sensitive to students’ meaning-making by inferring what they did through the badging process rather than primarily relying on what they said they did (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011). The two researchers discussed the analysis to critique it and seek counterexamples of evidence. The analyses were checked with some of the programme staff on an ongoing basis as well as through a debriefing meeting and an evaluation report as a form of member checking (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985).

5. Findings

Our analysis of student interviews and evidence supplied for completion of badges indicates student strengthening of salience, commitment, and self-esteem of Jewish identity.

5.1 Salience of Jewish identity

Since Jews are a minority in almost every setting in the United States, we can assume that the level of salience of Jewish identity will predict how often it is invoked. For example, someone with a low level of salience might hide their Jewish ethnicity even in settings where it would benefit them, an example would be someone asking for an explanation of a Jewish practice. Someone with a high level of salience will invoke their Jewish identity in settings that normally do not invite the use of Jewish ethnicity, an example of this might be the wearing of a traditional Jewish head covering (i.e. kippa, yamakah) in public settings.

One of the badge missions offered by the school was for participation in the school’s Mitzvah Day. The single-day event encouraged students to recognize and participate in good deeds, volunteer work, and charity. The following quote, submitted on behalf of a second grader by their parent, is from a student’s supplied evidence for completing a Mitzvah Day mission.

[David] has been holding the door for other people often. He held it for 3 people as they were walking into Grampa’s in Hollywood, Florida and for another person as we were going into Dunkin Donuts. He said to his mom that he just did a mitzvah and someone overheard him and said what did you say, he told us that he was Jewish also. So I told him see wherever you go there’s always someone Jewish.

In this quote, we see that David’s level of salience permits invoking his Jewish identity in a secular setting. The comment from another customer in the donut shop, identifying himself as a Jew, also likely reinforces David’s salience of his own identity; David now knows that other people’s Jewish identity can emerge in secular settings like Dunkin Donuts. The comment from David’s parent provided formative feedback to David, noting the importance of the exchange between the customer and David. The Mitzvah Day badge mission acts as an assessment that summarizes the salience of David’s Jewish identity and provides feedback that both confirms David’s participation in the Mitzvah Day and reminds him of the salience of his Jewishness.

Some students also noted a general increase in the salience of their Jewish identity through participation in the badge system. Daniel notes

Well, I’d probably do badges on – like, I’d probably do most of my badges on the holidays cause the holidays is mostly where you get Jewish. Mostly like Hanukkah.

Here is evidence that Daniel understands the Jewishness of his badge efforts. He plans on working toward his digital badges on Jewish holidays, noting that participation in a Jewish holiday is central aspect of his Jewish practice. The understood contrast to this is that his everyday life is not part of his Jewish practice. In other words, by participating in the digital badge system, Daniel was able to develop more saliency between Jewish holidays and his common everyday activities. It is then reasonable to then assume that his Jewish identity was strengthened by this increased saliency.

5.2 Commitment of Jewish identity

As a minority in the United States, there is limited opportunity for Jews to develop and increase the level and number of an individual’s relationships that involve their Jewish identity. This is not to suggest that there are no opportunities to construct these relationships but that, relative to relationships built on secular activities (e.g. sports teams, clubs, public school), the opportunities to develop relationships around Jewish identity are less frequent. Consequently, one of the common goals of Jewish education is to provide opportunities for Jews to strengthen their relationships with other Jews (Cohen and Veinstein Citation2011). This aligns with White & Burke’s (Citation1987) finding that commitment to an ethnic identity is predicted by the number and degree of relationships involving the identity.

The following quote was evidence supplied by a fourth grader who completed a digital badge mission for participating on Friday night Shabbat services at the temple. In this quote, the student notes how her Jewish identity was invoked through three different relationships: immediate family, clergy, and friends.

My family and I went to Shabbat services one Friday night. … Before the service, Rabbi [Goldberg] walked up to me and asked if I would like to help him open up the Ark. Of course, I said yes. I thought, ‘What a privilege! To go up to the [pulpit] for the first time!’ When the time came, I found I was joined by [Jessica Schwartz]. She also goes to temple and Hebrew school, and is in the 3rd grade. When we opened up the Ark, we got to hold the Torah crowns! Then, we walked around the room, following the Torah. Doing that made me proud and happy. It was very special too, because my grandparents were there to watch.

Attendance in a Jewish service is not likely sufficient for increasing Jewish identity. Through the process of earning a badge, the student reports that the Rabbi sought them out to participate in the service. This participation was interpreted as a privilege given both to her and a fellow student. In addition, the privilege was recognized by her family and the student to felt proud.

If commitment to a Jewish identity is influenced by relationships invoking identity, then Jewish education must use assessments that provide feedback on the development of these relationships. In the prior quote, the digital badge mission for attending services facilitated summative feedback that the student had completed a milestone of Jewish participation while also noting how that act involved three distinct relationships that involved Jewish identity.

Students also reported a general increase in their commitment to their Jewish identity through relationships with others. Daniel notes about digital badge mission that involves charity,

Well, it probably makes you feel more Jewish cause you’re helping people, so mostly like you’re getting rewarded for helping people, so that makes you feel better about being Jewish. It makes you feel more Jewish. Cause all these missions are like Jewish things. They’re very nice things that you do for other people, or you do.

The more he helps others, building relationships, the more Jewish he feels. To Daniel, being Jewish is being nice to others. We can assume that as Daniel continues to be nice to others, he will see this as a Jewish act. Consequently, his interaction with others increases his Jewish identity.

5.3 Self-esteem of Jewish identity

White and Burke (Citation1987) note that the strength of an ethnic identity is dependent on self-assessment involving that identity. If a goal of Jewish education is to increase Jewish identity, then corresponding learning opportunities need to enable positive results of that self-assessment. A digital badge can facilitate self-assessment by enabling a learner to identify how their Jewish identity is related to their self-esteem.

Similar to earlier quotes, the following was evidence submitted to earn a digital badge for participating in the school’s Mitzvah Day. The student is evaluating himself in regards to the Jewish goal of doing good deeds.

On Mitzvah day, I went to the sandwich making station and made sandwiches for people who either can’t afford food, or don,t [sic] have food. I got to put the sandwiches into plastic bags, and then put them into seperate [sic] brown bags packed with chips, a juice box, and an orange. I only got to make one full bag, but if I didn’t make that one bag, there would be one more person in the world starving.

Self-assessment requires examination of work and determination of whether the work meets selected standards (Boud Citation2013). Here the student notes the charity work he did and qualifies its limited impact on others, reflecting on the importance of his work despite its minimal nature. The Mitzvah Day digital badge acts as a summative assessment that provides feedback to the learner on what can be qualified as a good deed. Through providing evidence for the badge (i.e. receiving a summative assessment) the student engages in self-assessment within the context of the aspect of Jewish identity that promotes good deeds. Even if the increase in self-esteem is minor (as noted by the student), we can reasonably expect that the student’s self-esteem of his Jewish identity has strengthened based on the opportunity to perform a good deed.

Again, students also reported a general increase in self-esteem related to Jewish identity based on participation in the digital badge system. Debbie states:

Well, they do that by pushing me a little bit, pushing me forward in knowledge. When I finish one thing, there’s another thing that connects to it, and then I can do that too. That thing, so, everything leads to another thing, and everything leads to more knowledge, basically.

The badge system provided direction and opportunity for this student to increase their knowledge. She notes how what she is learning led to other learning goals and that she can accomplish each one. She concludes that knowledge is interconnected and that her learning will lead to future learning. Considering that the badges and missions are created for Jewish learning, it is clear that this student’s self-esteem of her Jewish knowledge has been increased.

6. Discussion

Aligning with the goals of Jewish education, a digital badge system should provide motivation, feedback, and acknowledgement of Jewish learning objectives while also strengthening the Jewish identity of the learner. In other words, Jewish education badge systems should offer the same type of pedagogical support as other types of badge systems but with the added goal of supporting and increasing Jewish ethnicity. Through interviews with student participants and evidence submitted to earn badges, we found a number of indicators that suggest that the studied digital badge system did strengthen Jewish identity. Although the digital badges were primarily designed to supplementary motivate and provide assessments for Jewish education, the badges also provided an opportunity for students to recognize their salience, commitment, and related self-esteem concerning their Jewish identity. It iincreases in salience, commitment, and self-esteem that are examples of strengthening a religious ethnic cultural identity.

Because digital badges can support Jewish education’s dual goal of learning about Judaism and building Jewish identity, the Jewish education research community should further study digital badges and determine the best designs and uses of these assessments. Second, other religions and ethnicities that wish to build and support ethnic identity can utilize the findings from this research to hypothesize similar success for utilizing badges for their respective peoples. For example, North American minorities that have established educational organizations (e.g. Armenian-American community, First Nations’ peoples) could model their badge systems after Jewish ones and potentially have similar, positive results.

Applied broadly to religious education, our findings suggest that digital badges could be used in religious education where a goal is to strengthen religious ethnic identity. Further, because the badge programme that we studied was implemented for supplementary education, we also conclude that digital badges could be applied to both formal and informal religious education. However, none of the aforementioned findings should be interpreted to imply that all religious education would benefit from using badges. Some religious education does not aim to strengthen identity. We also recognize that digital badges could be interested as incompatible with certain religious teachings or philosophies. Much more research is necessary to understand a number of factors concerning digital badges, including the degree to how ethnic identity interacts with digital badges, the impact of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators, as well as the potential for negative impacts in both learning or identity-related goals. Furthermore, our study did not include students who chose not to earn a badge, and we do not know their reasons for not participating. We have also not situated the use of digital badges within the broader scope of using technology in education or learning.

Nevertheless, this study suggests several implications for the design of digital badges for religious education. First, there is increasing likelihood of compatibility between digital badges and religious education, suggesting that religious education programmes of various denominations could use the former in service of the later. Similar to another study in a Jewish Day School setting (Wardrip et al. Citation2014), using digital badges to support religious education provides expands the toolkit of designers of religious education technology. This study also suggests that components of educational technology can be explicitly designed to support ethnic-cultural identity development. This might include, for example, creating opportunities to build one’s commitment toward a targeted religious identity. Finally, if components of ethnic-cultural identity development are integrated into the learning experience, those components can also be part of the formative and summative assessment process. Just as one might assess a students’ interpretation of religious text, we might also assess an element such as self-esteem with respect to the overarching faith community or its constituent parts.

7. Conclusion

Digital badges used in Jewish education provide evidence that this type of technology offers a unique opportunity for religious education. Past efforts to compensate for ethnicity in assessments would indicate that ethnic identity is inseparable from performance on assessments. Digital badges represent an opportunity born from the inverse goal, deepening the connection between ethnic identity and an assessment. Jewish education-related digital badges, as an example of implementation within a religious education setting, provide evidence that assessments can strengthen ethnic identity for one religion and thus potentially others.

Digital badges suffer from a key challenge of many emerging technologies: the expectation that the technology will solve a wide range of educational challenges. While it is far too early to suggest that digital badges will eventually meet the respective expectations for the technology, there is growing evidence that digital badges do provide innovative means to accomplishing underserved educational goals. Our aim in this study was not to prescribe only one correct use of digital badges but to draw attention to the meaning of evidence of a successful use of digital badges in religious education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Samuel Abramovich

Samuel Abramovich is the director of the Open Education Research Lab at the University at Buffalo where he is also an Assistant Professor in the Department of Learning and Instruction and the Department of Information Science. His research is devoted to finding and understanding the learning opportunities and challenges of Open Education through the application of the Learning Sciences. Shortly after graduating from the University of Pittsburgh with a Ph.D. in Learning Science and Policy, he was named a recipient of an Edmund W. Gordon MacArthur Foundation/ETS Fellowship. Prior to earning his Ph.D., Sam was a researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD, a technology coordinator for the Rashi School in Newton, MA, and a serial dot-commer.

Peter Samuelson Wardrip

Peter Samuelson Wardrip is an Assistant Professor of STEAM Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research focuses on informal/formal learning collaborations, professional learning for educators, formative assessment and making as a learning process. Peter earned his PhD in Learning Sciences and Policy from University of Pittsburgh and is currently a visiting researcher with the University of Pittsburgh Center for Learning in Out of School Environments (UPCLOSE) and the Learning Media Design Center at Carnegie Mellon University.

References

- Abramovich, S. 2017. “Are There Jewish Digital Badges?: A Study of Religious Middle- and High-School Girls’ Perception of an Emerging Educational Technology-Based Assessment.” Journal of Jewish Education 83 (2): 151–167. doi:10.1080/15244113.2017.1307050.

- Ahn, J., A. Pellicone, and B. S. Butler. 2014. “Open Badges for Education. What are the Implications at the Intersection of Open Systems and Badging?” Research in Learning Technology 22. doi:10.3402/rlt.v22.23563.

- Betancourt, H., and S. R. López. 1993. “The Study of Culture, Ethnicity, and Race in American Psychology.” American Psychologist 48 (6): 629–637. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.48.6.629.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 1998. “Assessment and Classroom Learning.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 5 (1): 7–74. doi:10.1080/0969595980050102

- Boticki, I., J. Baksa, P. Seow, and C.-K. Looi. 2015. “Usage of a Mobile Social Learning Platform with Virtual Badges in a Primary School.” Computers & Education 86: 120–136. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.015.

- Boud, D. 2013. Enhancing Learning Through Self-Assessment. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Boykin, A. W. 2014. “Human Diversity, Assessment in Education and the Achievement of Excellence and Equity.” The Journal of Negro Education 83 (4): 499–521. doi:10.7709/jnegroeducation.83.4.0499

- Bystydzienski, J. M. 2011. Intercultural Couples: Crossing Boundaries, Negotiating Difference. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Campbell, H. 2012. Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Carraher, T. N., D. W. Carraher, and A. D. Schliemann. 1987. “Written and Oral Mathematics.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 18 (2). doi:10.2307/749244.

- Cohen, S. M., and J. Veinstein. 2011. “Jewish Identity: Who You Knew Affects How You Jew—The Impact of Jewish Networks in Childhood upon Adult Jewish Identity.” In International Handbook of Jewish Education, edited by H. Miller, L. Grant, and A. Pomson, 203–218. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Davis, K., and S. Singh. 2015. “Digital Badges in Afterschool Learning: Documenting the Perspectives and Experiences of Students and Educators.” Computers & Education 88: 72–83. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.011.

- Emerson, R. M., R. I. Fretz, and L. L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Ethier, K. A., and K. Deaux. 1994. “Negotiating Social Identity When Contexts Change: Maintaining Identification and Responding to Threat.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (2): 243–251. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.243.

- Gallimore, R., and C. Goldenberg. 2001. “Analyzing Cultural Models and Settings to Connect Minority Achievement and School Improvement Research.” Educational Psychologist 36 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1207/S15326985EP3601_5.

- Gipps, C. 1999. “Chapter 10: Socio-Cultural Aspects of Assessment.” Review of Research in Education 24 (1): 355–392. doi:10.3102/0091732X024001355

- Gordon Commission. 2013. “To Assess, to Teach, to Learn: A Vision for the Future of Assessment.” http://www.gordoncommission.org/rsc/pdfs/gordon_commission_technical_report.pdf

- Greeno, J. G., and J. L. Moore. 1993. “Situativity and Symbols: Response to Vera and Simon.” Cognitive Science 17 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog1701_3.

- Halavais, A. M. C. 2012. “A Genealogy of Badges.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (3): 354–373. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.641992.

- Higashi, R. S., A. R. Shoop, and C. Schunn. 2012. “The Roles of Badges in the Computer Science Student Network.” In Paper Published at the Games+ Learning+ Society Conference, 423–429. Madison, WI: ETC Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: SAGE.

- Ogbu, J. U. 1992. “Understanding Cultural Diversity and Learning.” Educational Researcher 21 (8): 5–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X021008005.

- Peer 2 Peer University, and Mozilla Foundation. 2011. “An Open Badge System Framework.” http://dmlcentral.net/resources/4440

- Plori, O., S. Carley, and B. Foex. 2007. “Scouting Out Competencies.” Emergency Medicine Journal 24 (4): 831–835. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.051011.

- Reid, A. J., D. Paster, and S. Abramovich. 2015. “Digital Badges in Undergraduate Composition Courses: Effects on Intrinsic Motivation.” Journal of Computers in Education 2 (4): 377–398. doi:10.1007/s40692-015-0042-1.

- Rubin, H. J., and I. S. Rubin. 2011. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Scott, D. G. 1998. “Rites of Passage in Adolescent Development: A Reappreciation.” Child and Youth Care Forum 27 (5): 317–335. doi:10.1007/BF02589259.

- Steele, C. M., and J. Aronson. 1995. “Stereotype Threat and the Intellectual Test Performance of African Americans.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (5): 797–811. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797.

- Straub, D., K. Loch, R. Evaristo, E. Karahanna, and M. Srite. 2002. “Toward a Theory-Based Measurement of Culture.” Journal of Global Information Management 10 (1): 13–23. doi:10.4018/JGIM.

- Tsethlikai, M., and B. Rogoff. 2013. “Involvement in Traditional Cultural Practices and American Indian Children’s Incidental Recall of a Folktale.” Developmental Psychology 49 (3): 568–578. doi:10.1037/a0031308.

- Wardrip, P. S., S. Abramovich, M. Bathgate, and Y. J. Kim. 2014. “A School-Based Badging System and Interest-Based Learning: An Exploratory Case Study.” International Journal of Learning and Media.

- Wardrip, P. S., S. Abramovich, Y. J. Kim, and M. Bathgate. 2016. “Taking Badges to School: A School-Based Badge System and Its Impact on Participating Teachers.” Computers & Education 95: 239–253. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.008.

- White, C. L., and P. J. Burke. 1987. “Ethnic Role Identity among Black and White College Students: An Interactionist Approach.” Sociological Perspectives 30 (3): 310–331. doi:10.2307/1389115.

- Wilensky, D. A. M. 2015. “Can Digital Badges Save Hebrew School?” The Forward, 31 January. https://forward.com/culture/213651/can-digital-badges-save-hebrew-school/

- Wyche, S. P., G. R. Hayes, L. D. Harvel, and R. E. Grinter. 2006. “Technology in Spiritual Formation: An Exploratory Study of Computer Mediated Religious Communications.” In Cscw ’06, 199–208. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/1180875.1180908