ABSTRACT

This exploratory study investigated the disruption to schools ministry caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspectives of church leaders, Christian parents, Christian teachers and organisations involved in schools ministry were consulted using online surveys, interviews and focus groups, to examine how schools ministry could be rebuilt, incorporating reflective practice and hence bringing positive change. The severe impact of extensive school closures and restrictions strongly solidified the move from being largely provision of RE, lunchtime events and collective worship, to much broader methods in response to listening to the needs of the school (both staff and pupils in a secular/mainstream setting). A striking observation was that schools ministry was viewed in many of these case study settings as a peripheral aspect of local church ministry and often devolved to specialist organisations. Arising needs and models of ministry have emphasised the value and effectiveness of relational approaches and listening to the needs of schools and responding accordingly. This reinforces the need for collaborative approaches and long-term development of relationships between church and school. Training needs identified concerned relationship building and vision and strategy development, with many stakeholders perceiving this as the way forward to more effective ministry activity.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted all sectors of society (Byrant, Oo, and Damian, Citation2020; Crawley et al. Citation2020; Kim and Asbury, Citation2020) and brought widespread disruption to pre-existing ministry paradigms (Beamish, Citation2021; Johnston et al. Citation2022). Individuals and organisations who carried out ministry almost exclusively in schools were impacted by prolonged school closures and elongated restrictions imposed within schools (Knowles et al. Citation2022). This paper explores the lived experiences and implications of this on ministry in schools (Primary and Secondary) in the English context, utilising insights from multiple angles: case studies of schools ministry workers and Christian teachers, and an online survey amongst church leaders and Christian parents. Despite the despondency, frustration and isolation within pandemic ministry (Holmes et al. Citation2021), The British Academy (Citation2021, 6) argued that the pandemic had the potential to serve as a catalyst for change and rebuilding society in new ways. This resonates with the notion of Brueggemann (Citation2011), that disruptions to systems and predictable schemes may be positive, and indeed evidence of God’s capacity to break those schema and formulae and result in beneficial outcomes. This paper therefore asks what insights about ministry in schools were gained due to the pandemic disruption, and how these insights could contribute to a reconstruction and reshaping of this ministry area to comprise more effective ministry paradigms for the seasons ahead. We have sought to include a retrospective understanding of changes already occurring in schools ministry prior to the pandemic, especially around school chaplaincy and the way that such relational approaches were heightened and continued to develop throughout the pandemic. As a benchmark, we considered effective schools ministry to be that in which the aims and requirements of the main stakeholders are understood and respected, and where the work is focused on those aims in ways which enable the positive spiritual and Christian faith development of pupils, staff and ministry teams. To date, minimal robust research has occurred in this sector; so this paper seeks to begin conversations about the scope and function of ministry in UK state schools in the seasons ahead.

Literature review

Ministry in educational settings

There are differing models of ministry in educational settings. Christian education broadly seeks to foster spiritual formation to equip pupils for future challenges and to benefit society (Horan Citation2017). Christian schools enable teachers to act as Christian mentors to guide their pupils into a personal relationship with Christ, and develop the mind of Christ (Burton Citation2017). Chaplaincy as a phenomenon has risen in recent years (Ryan Citation2018), and offers a point of interaction between the church’s ministry and school pupils (Caperon Citation2015). An example is the Australian National School Chaplaincy and Student Welfare Programme, which became the National School Chaplaincy Programme in 2014 (Isaacs and Mergler Citation2018). There is great value in such partnerships whereby church, home and school work as partners, not competitors, to fulfil the Great Commission (Maitanmi Citation2019). Those ministering in schools may therefore hold a rootedness in the Christian faith, whilst having concern for the spiritual development of others (Caperon Citation2015). Upon this backdrop, this paper explores the lived experiences of various stakeholders involved in English schools ministry, although it is suggested that the insights and recommendations may be beneficial more broadly.

Pre-pandemic developments in English schools ministry

It is key to first understand the changes which had been occurring within schools ministry in England prior to the pandemic, to ensure that data are interpreted in a nuanced manner. Christian involvement in English schools has a long history, with Saint Augustine founding the King’s School, Canterbury in 597 and the King’s School, Rochester in 604, which led to the development of the schooling system which was primarily for those who could afford to pay until the eighteenth century. Schools for the impoverished were also started by the church, through non-denominational churches setting up the British and Foreign School Society in 1807, followed by the launch of the Church of England’s National Society in 1811. The responsibility was taken over by the state during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Worsley Citation2010; Shepherd Citation2008). Within this framework, chaplains had a responsibility of ministering in schools, with many schools founded by the church employing ordained chaplains to nurture the spiritual life of pupils (Tregale Citation2011, 5). This approach aligns with a mindset of mission not being merely expansion of the church itself, but being grounded within God’s mission in the world, namely the notion of missio Dei which captures a sense of the activity of the church within God’s mission in the world (Youn Citation2018). The strong involvement of the church with schools was recognised by the Education Act (1944) including Religious Instruction lessons and acts of collective worship, known as ‘assemblies’ (HM Government Citation1944). Through this Act and the 1998 Education Act, schools have had a legal duty to deliver collective worship which was ‘wholly or mainly of a broadly Christian character’ (Department for Education Citation1994). The nature of Religious Studies changed during the 1960s, from being solely focused on Christianity to including other world faiths, and more recently, the recommended curricula have included those with no religious faith (Religious Education Council of England & Wales REC Citation2013, 11).

Within the 1960s and 1970s, Christians began to be involved in a voluntary capacity, as opposed to previously ordained ministers being the primary link. The impetus for this arose from the perception of a general decline in Christian belief following the World Wars (Shepherd Citation2008). Furthermore, some Christian agencies, such as Youth for Christ, began ministry in schools with Christian youth workers taking part in formal educational aspects such as lessons and assemblies, and informal settings including lunch-time clubs, often known as Christian Unions (Shepherd Citation2008) in order to introduce the Christian faith to children and young people within the school system. New ways of undertaking youth ministry were developed by Youth for ChristFootnote1 and other Christian agencies during the 1970s to 1990s and included peripatetic mission teams, and locally based workers in schools.

The work became known within the Christian community as ‘schools’ work’, and covered activity undertaken with children and/or young people, within and alongside educational establishments, designed to support, enable and encourage their personal, social, spiritual and academic development and especially their understanding of and potential commitment to Christian faith (Boost Citation2022).

In 1988, the Education Bill was adjusted for a multi-faith society, wherein it was agreed that all pupils were to take part in a ‘daily act of worship which should be wholly or mainly of a broadly Christian character’ (DFE Citation1994; Cooling Citation2010). It was deemed to be broadly Christian if it reflected the broad traditions of Christian belief, without being distinctive of any particular Christian denomination (Cooling Citation2010). In 2004, the Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED) issued guidance that all schools have a statutory duty to promote spiritual development, included within Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural development of pupils across the curriculum and across the school (Ofsted Citation2004). For Christians active in school ministry, this was seen as the door remaining open for their work and involvement, with formal, informal and non-formal educational activities taking place. This was delivered through a range of providers including community groups, voluntary organisations, local churches and Christian agencies (Boost Citation2022).Footnote2 More recently, English schools were obliged by UK government policy and frameworks to support fundamental British values which has led to a complex interplay between this and simultaneously upholding Christian values, particularly in faith schools (Bowie and Revell Citation2016).

Nash, Nash, and Roberts (Citation2020) noted a significant move from schools ministry deliverers considering schools to be an ‘open door’, wherein they could fulfil their aims, especially around presenting aspects of the Christian faith, to a position where providers listen to schools (staff, pupils, parents and governors) and seek to meet the needs of educational settings, especially through chaplaincy models. Caperon (Citation2015) observed that the ministry of school chaplains is the most significant single point of contact between the Church and secondary-age young people. In recent years, the role of chaplains in educational settings has gained in popularity to the point where there is now both a Centre for Chaplaincy with Children and Young PeopleFootnote3 (linked to the Institute of Children Youth and Mission) and a Centre for Chaplaincy in Education.Footnote4 This approach does carry tensions, as Nash and Roberts (Citation2016) observed the sending church may view the chaplain as an evangelist or missionary whose purpose is to preach the gospel and make disciples, but in contrast, the associated schools may view chaplains with suspicion. This raises the question of whether a chaplain’s purpose is for children or the church?

The purposes of schools ministry

The British Academy (Citation2021) emphasised that whilst the pandemic had the potential to be a catalyst for change, it required clarity and awareness of purpose. Isaacs and Mergler (Citation2018) revealed that in the Australian context, the organisation which was contracted by the state to provide chaplains had a clear understanding of their role and purpose within the educational setting. There have previously been similar efforts to capture the purposes of schools ministry within the English setting. Roberts (Citation2017) highlighted the need to view the work that is being carried out in relation to biblical foundations, and referred to models focused on evangelism, service, teaching and accompanying.

The great commission is often cited as the impetus for outreach in schools (Steinberg Citation2014). Evangelism is viewed as a ‘purpose’ by many Christians in the sector, dating back to the 1970s when Youth for Christ and others first commenced this work (Roberts Citation2017). Astley (Citation2002, 190) stated that ‘education and evangelism may be closer neighbours than many suspect’. Organisations may seek to present their faith to children and young people within the RE curriculum, as curriculum guidance on RE suggests that having visits from members of a faith community is beneficial since it allows students to hear how faith affects someone in their day to day living and can build understanding, and even promote social and community cohesion (RE Council Citation2013). Aligning with this, spiritual development is seen as an important part of the role and purpose of education and school visits by Christians can contribute to a student’s awareness of the ‘spiritual’ and give them opportunities to explore for themselves what faith might mean (Roberts Citation2017). It is important to note a well-documented concern by schools that contributions from Christians should be an indication of what they believe and not a means of persuading pupils to adopt the Christian faith (Swindon SACRE Citation2022). Likewise, Christian teachers themselves state that proselytising is not appropriate in an inclusive and fair classroom (Cooling Citation2010, 61). Thiessen (Citation2013) reported that teaching about religion is deemed to be acceptable, whereas teaching of religion is not since this is considered to align with indoctrination. Whilst neutrality is viewed as the ideal stance for teachers in the classroom, in practice, this is challenging as teachers inherently tend to influence their pupils to some extent (Thiessen Citation2013). Indeed, Bowie (Citation2017) expounded the complexities of tolerance and the challenges for teachers to translate policy into practice.

With this in mind, Nash, Nash, and Roberts (Citation2020) devised a chaplaincy model and addressed the need for occupational standards in this work. Mundell (Citation2010) described this as a theology of being present. Likewise, Caperon captured the essence of ‘chaplaincy’ as:

‘being present for others, being there with others, being known to and knowing others, all the time being conscious of being the one seen as the “God Person”; the one whose presence in some sense incarnates God; makes, that is, the reality of God and the love of God visible and actually present in the community’.

Chaplains tend to operate within a strong ethical framework supporting the school values and complementing existing services such as psychologists, counsellors and youth workers, and offer guidance and support in times of crisis, providing continuing care for staff and pupils (Isaacs and Mergler Citation2018). This way of working has similarities to the ‘accompanying’ model where there can be a more educationally focused impact through mentoring, pastoral care, pre-exclusion work and classroom support (Roberts Citation2017). In this way, some have opted to focus on schools work defined as service, namely activity to support the school without conditions, such as classroom support, mentoring, additional bodies on school trips or enrichment activities which can take place in school outside of formal learning in lessons (Roberts Citation2017). The starting point of this model is the needs of the school. Specific skills are offered to enhance the educational experience, such as the ability to listen and support, operating extra-curricular activities such as sports training. A development of this accompanying approach is the Faith in the Nexus project, which encouraged schools to facilitate opportunities for children’s exploration of faith and spiritual life in the home, as part of a more collaborative way of working.Footnote5

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on schools work

Paradigms of ministry were significantly impacted by COVID-19 (Beamish, Citation2021; Holmes, Citation2022; Johnston et al. Citation2022), particularly ministry in schools due to prolonged school closures and restrictions on visitors (Knowles et al. Citation2022). Whilst research is ongoing around the longer term impact of the COVID-19 lockdowns and changed practices in schools, it is evident that some young people were impacted more than others, with pre-pandemic disparities being widened (Hawes, Marrapodi, and Colligan Citation2021; Patalay and Fitzsimons, Citation2020). These impacts occurred within youth ministry also. Prior to the pandemic, there was generally a very positive response by young people to faith activities, for example prayer spaces in schools (Stern and Shillitoe Citation2018). However, attendance of young people at out of school faith activities fell by an average of 53% (Shuker Citation2021). It transpired that youth work outside of the church, which normally included work in schools, experienced the most severe loss of young people, from an average of 28 young people pre-lockdown to 10 young people post-lockdown, presumed to be due to significant school closures in 2020 and associated restrictions (Shuker Citation2021). This coincided with the volunteer workforce shrinking markedly and some church and Christian agency youth workers being furloughed (Shuker Citation2021). This is why it is key to consider how this disruption could effect positive developments in the ongoing schools ministry sector.

Methodology

This project was an exploratory study which aimed to investigate i) how approaches to schools ministry changed due to the pandemic lockdowns, and the consequent training needs; ii) the extent to which the wider Christian community connected with schools ministry during the pandemic; and iii) what models and approaches may improve effectiveness in the seasons ahead?

Participants were recruited from the English context only since that ensured parity of schools policy and national regulations and also uniformity of lockdown restrictions, and a range of methods were employed to ensure a variety of perspectives were captured. Interview data were collected from self-selecting schools ministry practitioners (n = 15) and church-based children’s leaders (n = 26). Narrative accounts were collected from Christian teachers (n = 10) and an open-ended online survey was completed by schools ministry practitioners in June 2021 (n = 37) and May 2022 (n = 24). These individuals served as case studies since they did not provide a representative sample but did provide a means to gather qualitative data, giving insights from their lived experiences and perceptions. Using case studies in this way enabled examination of the experiences of participants within this specific context in detail, so that general principles and rules could be drawn while relying on the analysis of the context that reflects everyday experience (Pacho Citation2015). The insights from these case studies provided rich data, aiding the identification of some of the key issues and experiences in the sector. Alongside this, an online survey was carried out to gather the views of church leaders (n = 34) and Christian parents (n = 62). This survey was part of a larger project which included four questions about schools ministry.

The interview and survey data collected were all analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Clarke and Braun, Citation2013), enabling the identification of emerging themes. This empirical research was all subject to the ethical scrutiny of Liverpool Hope University’s ethics committee, and therefore assured informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality of all participants.

Results

Insights from church leaders/representatives

The data revealed minimal connection between churches and schools. In most cases, schools work was viewed as peripheral to the core ministry of the church. Only 6% of participant churches reported relational support of schools. Many expressed that other ministry organisations (such as Youth for Christ, Scripture Union) would work within schools, and therefore it was not a role of the local church. Even so, 33% of the survey respondents provided assemblies or RE lessons (pre-recorded or live) during the lockdowns. Aside from this provision of assemblies and RE lessons, which seem to be diminishing, responses from church leaders and children’s workers indicated that local churches often do not participate in the vision of outreach through schools, but instead it may be delegated to others, namely individuals or organisations who are perceived to be ‘expert’. These may or may not be supported financially by the local church. Churches tended to view schools in a rather transactional manner, delivering content or hosting schools visits to church, but there was minimal relational contact beyond that.

Insights from Christian parents

The majority (83%) of parent participants said that their child’s faith had not been supported by school during the lockdowns. The remainder said that support had been in the form of collective worship, RE lessons and the general school ethos of respecting faith, prayer and support for parents in their nurturing role. When asked whether they wanted school to support their child’s faith, typical responses were as follows: ‘my son has his faith nurtured at home and church, so he does not need it at school’ and ‘we do not expect or ask for faith stuff in school’. To meet the spiritual needs of their child, 70% of the parent participants identified the roles of specific individuals or groups, labelled varyingly as ‘the youth team’, ‘youth leader’ or ‘minister’. Narrative accounts exhibited minimal evidence of partnership or working together between schools, church and home and only 10% of the parent participants said that their church had supported local schools during the pandemic.

Insights from Christian teachers

Respondents were asked how schools perceive input from churches and Christian organisations. One stated that: ‘sometimes it can seem a little irrelevant and cringey but if it’s quality then is great’, and a few viewed input with suspicion, such as ‘it is hard finding churches who want to be involved in the right ways … I mean being in it for the long haul, relational and trust-building in first instance – not just “slam bam assemblies” and one off church visits’. Two stated that their school is wary to include Christian input because they would need then to include input from other faiths also. One distinguished between local churches and Christian organisations, saying that ‘a lot of schools are willing to have Christian organisations in to give assemblies on a Christian theme but they don’t generally get involved with churches’. Another explained that relationships had been built with the local church over a five-year period, and in a ‘non-intrusive way’. He reported that significant time spent building relationships with all stakeholders was ‘highly beneficial’.

One Christian school teacher suggested that churches providing assemblies or workshop activities at Christian festivals, such as Christmas and Easter, are helpful, whilst another spoke of the need for partnership and strengthening relational links more effectively. The remainder made broad suggestions, such as volunteering within the school and ‘practical support that demonstrates love’. Others specified mental health support, such as ‘anything to help the children and teacher well-being’, ‘counselling services from a church or other Christian organisation’, ‘social and communication groups for children who lack confidence’ and ‘support for students refusing to go to school’.

Respondents stated that Christians were a positive influence (described as ‘salt’) in schools, and can ‘build children’s confidence’. Other responses were more evangelistic in nature: ‘to ensure that truth is being proclaimed’, ‘to show our young people that life with Christ is exciting and relevant’ and to use gifts to ‘God’s glory’. One remarked that ‘it’s not just what we do but how we do it and how “quickly” we move to deliver it. Slow, steady and at the right time with the right intention wins the race in non-Christian schools!’ Similarly, another stated that ‘assemblies and RE lessons have their place within the context of genuine relationship where relationship is the end not a means to an end’.

Insights from those involved in schools ministry

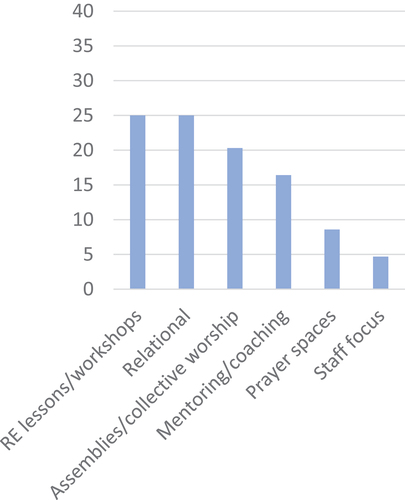

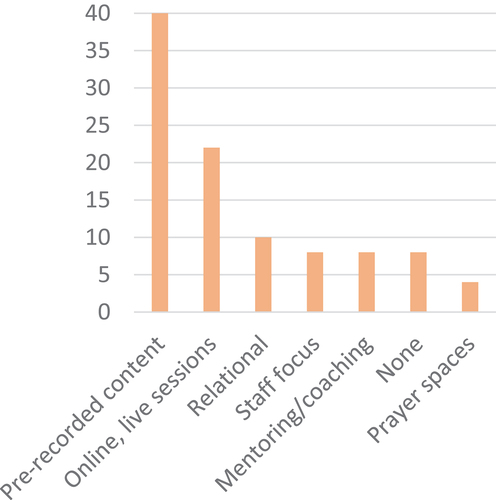

show the nature of the work carried out by participant practitioners. Graph 1b reveals that the pandemic markedly altered the essence of schools ministry activity. Eight per cent reported no schools ministry occurring during pandemic restrictions, whilst 62% reported having produced pre-recorded content or live online lessons. Eight per cent had continued mentoring or coaching online, and 4% provided prayer spaces in some way (outdoor or online).

Figure 1b. The nature of schools ministry during pandemic lockdowns (% of activity reported by practitioners).

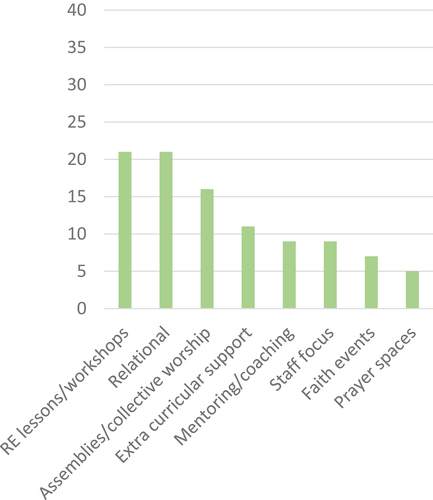

Figure 1c. The nature of schools ministry once pandemic restrictions were easing (% of activity reported by practitioners).

The data in graphs 1a and 1c indicate slight decreased involvement in RE lessons and collective worship because of the pandemic. During the interviews, some participants explained that they had struggled to re-connect with schools once restrictions eased, with some practitioners feeling that schools had taken the opportunity to cull their involvement. However, others said that they had been ‘welcomed with open arms’. It is notable that whilst reported relational activity has fallen slightly since pre-pandemic, extra-curricular support (such as running sports clubs or self-confidence sessions) and faith events (such as Christingle services) are now reported by our participants as an addition, and these in essence are relational in purpose, suggesting that 39% of post lockdown activity is relational in these sample contexts. The focus on school staff (resourcing, training and pastorally supporting) has doubled.

Forty per cent reported negative impacts of the pandemic on schools ministry, whilst 36% felt positive, describing new opportunities, and 11% expressing changing needs. Some negative responses concerned access, such as ‘we’ve not been asked to do assemblies anymore’, ‘RE has taken a bit of a hit as schools are focussed on catch up in core subjects’, ‘90% of our clubs have not resumed’, ‘getting back into schools has proved challenging’ and ‘it’s been hard to rebuild what was previously a strong relationship’. Some responses described resourcing pressures, such as ‘reduced resources due to reduced giving in churches’. One participant did caveat this with the statement that ‘God can continue to work through all circumstances’, highlighting that the underpinning ethos is key to the operational activities.

Those who reported positive change included enhanced relational opportunities, such as ‘bubbles coming to the church meant more work but closer working relationships’, ‘Schools would like us to do more lunchtime clubs’ and ‘staff continue to value the support they receive from us’. There was variance in participants’ responses, with some stating that ‘often the teachers have no idea who we are or which church we’re from’, whereas others reported that ‘the staff expressed how much they value us much more than before’. This demonstrates the fundamental role of relationships with staff as a foundation for schools ministry. Other benefits related to the provision itself, such as ‘the pandemic has helped us to emerge with a focussed offer’ and ‘we can now offer a flexible approach using in-person sessions as well as recorded material’. The changing needs identified by participants included ‘schools are keen for relationship’, ‘school has asked us to run a listening service for school staff’, ‘more requests for mentoring’ and ‘increased needs for mental health support for students’. These comments all indicate increased needs of schools for support regarding student and staff mental health and well-being. Many explained that they had learned to be flexible and react to situations as they arise, due to pandemic circumstances. Participants described these as beneficial learnings to carry forward in their ministry.

Almost half (42%) believed that schools wanted support, people to listen and emotional support, whilst 27% felt they desired to return to normal, 12% deemed they wanted resources and teaching to fulfil the RE and collective worship requirements and 8% perceived chaplaincy as a desire alongside prayer and creation of safe spaces to listen to young people. It is interesting that 14% of school practitioners were not sure what schools wanted, raising the question as to whether they had dialogued with the school to find out.

Figure 2 exhibits a desire for support regarding background knowledge and awareness and strategic skills, such as how to develop vision and appropriate strategy, building relationships with schools, understanding school culture and ethos and gender and sexuality. There was a need for practical training such as safeguarding specific to the school context, recruiting volunteers, the National curriculum and expectations for RE, as well as training to provide expertise which could be used in the schools setting, such as listening skills, mental health well-being and resilience-building. There were also calls for a shared pool of resources. Many explained that they had learned to be more flexible but also more reflective and evaluate their approaches more, and this was reported as being highly effective to their ongoing ministry.

Discussion

Changes in schools ministry approaches

This research confirms the significant disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic on this ministry sector, namely that it largely ceased in the early pandemic, with some workers being furloughed, others made redundant and some becoming focused primarily on producing video content. Subsequently, the ministry has restarted, for some along the lines of what it was before, but for many of our research participants, the nature of the activities offered to their local schools changed markedly, being less focused on delivery of assemblies and RE lessons to be more broadly supportive and relational activities. This change of emphasis had been happening pre-pandemic but seems to have been heightened, according to our participants. One long-running schools ministry in the area, for example, was a long-running schools ministry project in the area opted to rename all of their work as ‘chaplaincy’, from which other activities, such as RE lessons and assemblies, developed. This exemplifies the intentional shift in focus and strategy. Alongside developing relational work, schools valued specialist skills, such as mentoring, counselling and sports coaching. Integrating such skills, or in many cases putting these at the forefront of strategies of ministry, had begun in part prior to the pandemic according to our respondents, but it was clear from our multiple stakeholder perspectives that these skills and opportunities became considerably more desired and utilised by schools as ministry began to be reconstructed as the pandemic restrictions lifted.

Many of the schools mentioned by our participants have used this interjunct as an opportunity to cull outside activities or contact which they did not perceive as beneficial, and in some cases were ‘cringy’, irrelevant or of low quality. Christian teachers highlighted that schools are often wary of input from a single local church. This highlights the need for schools workers to ensure ethical practice, protecting the dignity and worth of those involved, and avoiding unethical proselytising, denoting reducing the proselytizee to the status of an object in the proselytising program (Thiessen Citation2013). Ministry workers in schools must be aware of this.

A key focus of the qualitative comments was ‘relationships’. This has been evidenced by the heightened shift of schools ministry practitioners to extra-curricular support for pupils and staff well-being also. Whilst some of our case study practitioners viewed this time as closing up of the ministry, others responded by re-imagining what could be delivered and the way it could happen, given the changed circumstances. Indeed, some emphasised the need to listen to schools and be flexible in responses, whilst some were unaware of the altered school needs. These responses to the impact of the pandemic were replicated across Christian youth and children’s work generally (Shuker Citation2021; Holmes et al. Citation2021). From the qualitative and quantitative responses across all stakeholders in our study, there has been a change in the way of working to be more flexible and responsive to the needs of schools, and to evaluate in a continuous way. This surely points towards more effective schools ministry, as we have defined it in this paper: understanding and respecting the requirements of all stakeholders, and working within the intersection of these aims. This reflects Mundell (Citation2010), that volunteering in schools should not merely be to fill a deficit, but rather should serve the purpose of the volunteer learning about the needs of the children and staff and having open-ended discussion, with a long-standing commitment to form reciprocal relationships. It is therefore interesting that schools ministry workers in this project highlighted training needs regarding development of vision and strategy, as well as how to build relationships with schools. Much of the existing provision of initial training is around the development of basic skills, and practice which does not contravene legal requirements. Currently, very few practitioners are undertaking validated training.

The extent to which the wider Christian community connects with schools ministry

Participants indicated a lack of strategic involvement of churches with their local schools, with minimal evidence of partnership between church, school and home. Schools work seemed to be a very peripheral aspect of church ministry, despite Goody’s research (2020) revealing that 98% of churches deemed it important to engage in their local primary school. Whilst viewed as important, it often does not translate to operational involvement. This concurs with other research, which revealed that less than 2% of churches surveyed worked with local schools (Shuker Citation2021). Many Christian parents in our study expressed surprise at the thought of such connection, as most parent participants viewed education as separate to faith, which is counter to the values of Faith in the Nexus and the Growing Faith Foundation. This resonates with other ministry sectors, where most churches were found to not have a formal strategy for children or family ministry (Holmes et al. Citation2021). It is likely that this may apply to schools ministry also. However, Mundell (Citation2010) emphasised the need for a theology of being present, namely a constant reciprocity of being both guest and host, while being present in the setting. This rationale seemed to be developing in a small number of cases within our sample.

Where there was contact with schools during the lockdowns, it was primarily reported by our participants to be focused on content provision rather than relationships. As restrictions lifted, there were confusion and disruption as many participants reported that schools they were connected with no longer required external RE or assembly provision in the same way as pre-pandemic. The switch to more of a flexible and relational focus has seemed challenging for churches and schools ministry workers alike within our case studies. Indeed, Horan (Citation2017) revealed that whilst relationally based programmes are seen as most effective in fostering spiritual formation, they are infrequently implemented due to insufficient training or expertise of those involved, or as a result of an historical approach to the motivation for the work. Shepherd (Citation2008) argued that this approach was in order to introduce the Christian faith to children and young people within the school system. At the same time, schools have often chosen to work with local Christian organisations rather than a local church, in order to be able to work with the range of churches represented by the organisation rather than having a multitude of churches wishes to come in, as they perceive it.

What models and approaches may improve effectiveness in the seasons ahead?

This paper sought to investigate how pandemic disruption could effect positive change. Whilst these findings are based on case studies of participants from different perspectives, a strong theme emerged of the importance of listening to the needs of schools and being flexible about responses. Participants emphasised the need for long-term relationships being the basis for the local church working in partnership with schools and alongside other churches, supported by agencies such a Scripture Union, Youth for Christ or a locally created multi-church agency. Such long-term collaboration seems to have been minimally present throughout the recent history of schools ministry, but according to our participants, it is much more at the forefront of strategies and practice now. Again, this points to the enhanced effectiveness of schools ministry, according to the definition we have described for this paper. Maintaining ethical practice is critical, so that there should not be any hidden agendas, hence requiring reflection about how to navigate this with an evangelical mindset. Validated training programmes for schools workers could address this, ensuring a sensitive balance between the reasons for undertaking schools ministry and the potential to fall into proselytising. Professional training awards and theological colleges, alongside organisations involved in schools ministry, are well placed to train and support churches in working strategically to this end, and to explore the missio Dei within their own locality, specifically in relation to local schools. Youn (Citation2018) asserted that missiology ought to learn from cultural anthropology that a missionary must throw away the sense of cultural superiority to indigenous cultures. This seems particularly key during this phase of rebuilding schools ministry and seeking to foster greater effectiveness through greater collaboration of stakeholders and working towards the collective aims of each.

Conclusion

This research could be developed further by broadening the stakeholder’s sample and asking children and young people for their views of schools ministry. Nevertheless, our study highlights that the requirements and nature of ministry in school settings were already changing, and this change was heightened due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, there are indications of many new opportunities and possibilities. But there is a need for all involved in this sector to reflect and evaluate so that the approaches and paradigms may be refined and reconstructed to be more effective in the seasons ahead. This will alter the training and resourcing needs. At the same time, it will be important for churches and organisations to invest in validated training for those involved.

Ultimately, tentative findings are that revised paradigms require greater collaboration and relationships between churches and local schools, and a stronger sense of strategy, mission and purpose to be formulated by churches and those involved in serving in schools to boost the effectiveness of this ministry. The interplay between the different providers of schools ministry (Christian organisations and local church) needs to be explored, in the endeavour of greater collaboration and co-constructing of strategy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah E Holmes

Sarah Holmes is lecturer in Early Childhood studies, researching faith and spirituality in children and families in the NurturingYoungFaith project.

David Howell

David Howell has been involved in Christian Youth Work for fifty years and is now a Freelance Consultant in Further and Higher Education and a trainer in Christian Youth Work.

Notes

5. Faith In The Nexus (nicer.org.uk).

References

- Astley, J. 2002. “Evangelism in Education: Impossibility, Travesty or Necessity?” International Journal of Education and Religion 3 (2): 179–194. doi:10.1163/157006202760589679.

- Beamish, R. 2021. “Preaching in the Time of COVID: Finding the Words to Speak of God.” Practical Theology. doi:10.1080/1756073X.2020.1869371.

- BOOST. 2022. Re-Imagining Schools Work. South East Partnership. https://www.separtnership.org.uk/boostresource.

- Bowie, R. 2017. “Is Tolerance of Faiths Helpful in English School Policy? Reification, Complexity, and Values Education.” Oxford Review of Education 43 (5): 536–549. doi:10.1080/03054985.2017.1352350.

- Bowie, R. A., and L. Revell, (2016). Negotiating Fundamental British Values: Research Conversations in Church Schools.

- The British Academy. 2021. “The Covid Decade: Understanding the Long-Term Societal Impacts of COVID-19.” https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/3238/COVID-decade-understanding-long-term-societal-impacts-COVID-19.pdf.

- Brueggemann, W. (2011). The Prophetic Imagination. https://onbeing.org/programs/walterbrueggemann-the-prophetic-imagination-dec2018/

- Burton, L. D. 2017. “Educational Practices in Christian Schools.” Journal of Research on Christian Education 26 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1080/10656219.2017.1292743.

- Byrant, D. J., M. Oo, and A. J. Damian 2020. “The Rise of Adverse Childhood Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy 12. doi:10.1037/tra0000711.

- Caperon, J. 2015. A Vital Ministry. London: SCM.

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun 2013. “Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners.” Successful qualitative research 1–400.

- Cooling, T. 2010. Doing God in Education. London: Theos.

- Crawley, E., M. Loades, G. Feder, S. Logan, S. Redwood, and J. Macleod 2020. “Wider Collateral Damage to Children in the UK Because of the Social Distancing Measures Designed to Reduce the Impact of COVID-19 in Adults.” BMJ Paediatrics Open 4 (1). doi:10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701.

- Department for Education (DFE). 1994. “Circular Number 1/94 Religious Education and Collective Worship.” Microsoft Word - circular 1-94 final.doc (educationengland.org.uk)

- Hawes, F. M., M. E. Marrapodi, and A. Colligan 2021. “Technology Preparedness and the Impact on a High-Quality Remote Learning Experience: Lessons from Covid-19.” Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 21 (11): 41–53.

- HM Government. 1944. “Education Act 1944.” https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/7-8/31/contents/enacted

- Holmes, S. E. 2022. “The Changing Nature of Ministry Amongst Children and Families in the UK During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Christian Education Journal: Research on Educational Ministry 19 (1): 134–151. doi:10.1177/07398913211009912.

- Holmes, S. E., L. Murray, S. Price, M. Larson, V. de Abreu, and P. Whitehead, (2021). “Does the Church Have a Plan for Reaching Children? (Multi-National Research Report).” (nurturingyoungfaith.org)

- Horan, A. P. 2017. “Fostering Spiritual Formation of Millennials in Christian Schools.” Journal of Research on Christian Education 26 (1): 56–77. doi:10.1080/10656219.2017.1282901.

- Isaacs, A., and A. Mergler. 2018. “Exploring the Values of Chaplains in Government Primary Schools.” British Journal of Religious Education 40 (2): 218–231. doi:10.1080/01416200.2017.1324945.

- Johnston, E. F., D. E. Eagle, J. Headley, and A. Holleman. 2022. “Pastoral Ministry in Unsettled Times: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Clergy During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Review of Religious Research 64 (2): 375–397. doi:10.1007/s13644-021-00465-y.

- Kim, L. E., and K. Asbury 2020. ““Like a Rug Had Been Pulled from Under you”: The Impact of COVID-19 on Teachers in England During the First Six Weeks of the UK Lockdown.” The British Journal of Educational Psychology 90 (4): 1062–1083.

- Knowles, G., C. Gayer‐Anderson, A. Turner, L. Dorn, J. Lam, S. Davis, R. Blakey, et al. 2022. “Covid‐19, Social Restrictions, and Mental Distress Among Young People: A UK Longitudinal, Population‐Based Study.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 63 (11): 1392–1404. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13586.

- Maitanmi, S. O. 2019. “Reflections on Christian Education.” Journal of Research on Christian Education 28 (2): 91–93. doi:10.1080/10656219.2019.1649401.

- Mundell, L. 2010. “A Theology of Presence: Faith Partnerships with US Public Schools.” Not by Faith Alone: Social Services, Social Justice, and Faith-Based Organizations in the United States 33–49.

- Nash, S., P. Nash, and N. Roberts. 2020. “Chaplaincy as a Reframing and Expansion of Youth Ministry – Initiating and Developing an Occupational Standards Ecumenical Project in the UK for Chaplaincy with Ages 5–25 (2020).” Journal of Youth and Theology 19 (2): 124–138. doi:10.1163/24055093-bja10008.

- Nash, P., and N. Roberts. 2016. Chaplaincy with Children and Young People. Grove: Cambridge.

- Ofsted. 2004. “Promoting and Evaluating pupils’ Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural Development.” Ofsted 2004; Subsidiary Guidance ~ Supporting the Inspection of Maintained Schools and Academies from January 2012. Ofsted 2012

- Pacho, T. 2015. “Exploring participants’ Experiences Using Case Study.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 5 (4): 44–53.

- Patalay, P., and E. Fitzsimons 2020. “Mental Ill-Health at Age 17 in the UK.” Age 17: 28.

- Religious Education Council of England & Wales (REC). 2013. A Curriculum Framework for Religious Education in England. Nottingham: The Religious Education Council of England and Wales.

- Roberts, N. 2017. “Four Models of Schools Work: Responsible, Purposeful Approaches for Christians Working in Education.” https://www.academia.edu/12951853/Four_Models_of_Schools_Work_Responsible_Purposeful_Approaches_for_Christian_Youthworkers_Working_in_Education?email_work_card=view-paper.

- Ryan, B. 2018. “Theology and Models of Chaplaincy.” A Christian Theology of Chaplaincy 79–100.

- Shepherd, N. 2008. Schools’ Ministry as Mission. Grove: Cambridge.

- Shuker, L. 2021. The Story: Statistics, Trend and Research for Youth Work (18). Luton: The Youthscape Centre for Research.

- Steinberg, P. S. 2014. Education Evangelism: Sixteen Best Practices for School Outreach. Lynchburg, VA: Liberty University.

- Stern, J., and R. Shillitoe. 2018. Evaluation of Prayer Spaces in Schools the Contribution of Prayer Spaces to Spiritual Development. York: York St John University.

- Swindon SACRE (Standing Advisory Council on Religious Education). 2022. “Printed Minutes 05052022.”

- Thiessen, E. J. 2013. “Evangelism in the Classroom.” Journal of Education and Christian Belief 17 (2): 221–241. doi:10.1177/205699711301700203.

- Tregale, D. 2011. Fresh Experiences of School Chaplaincy. Cambridge: Grove Books.

- Worsley, H. 2010. Churches Linking with Schools. Grove: Cambridge.

- Youn, C. H. 2018. “Missio Dei Trinitatis and Missio Ecclesiae: A Public Theological Perspective.” International Review of Mission 107 (1): 225–239. doi:10.1111/irom.12219.