Abstract

How migration and mobilizations of difference are accommodated at the local level is a burning question. Concepts adopted by local governments and the capacities of cities to formulate and implement these have received increasing attention, but often without examining the ideas and norms that underlie local concepts and practices. This article assesses the hypothesis of local-level pragmatism, which it rejects, and develops the notion of ‘paradigmatic pragmatism’ to characterize how local-level politics address mobilizations of difference. Based on empirical findings from Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds, and comparing the content and the implementation of ‘diversity policies’, I argue against a dichotomy of pragmatic vs ideational politics. Instead, these cities draw on a variety of ideas and pragmatically combine them under the header of diversity. This paradigmatic pragmatism invites further research on the effects of potential incompatibilities of immigrant policy ideas.

1. Introduction

Scholars are engaging increasingly with dynamics of immigrant-policymaking at the local level (Alexander Citation2007; Allen and Cars Citation2001; Caponio Citation2010b; Collins and Friesen Citation2011; Garcia Citation2006; Glick Schiller and Caglar Citation2010; Jørgensen Citation2012; Neill and Schwedler Citation2007; Nicholls and Uitermark Citation2013; Penninx and Martiniello Citation2004; Poppelaars and Scholten Citation2008; Uitermark Citation2010; Vermeulen and Plaggenborg Citation2009; Zincone and Caponio Citation2006). Most recently a specific claim was made about the particular pragmatic character of these policies (Scholten Citation2013). However, what such a notion of pragmatism implies, and whether a pragmatism is characteristic for the local level has neither been sufficiently developed nor empirically grounded. Are cities’ immigrant policies pragmatic in character, as Scholten (Citation2013) suggested? If so, is pragmatism a particular characteristic of the local level as opposed to the national level?

This article challenges the implied dichotomy between the character of local- and national-level policies. Using empirical research in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds, I show how local policymaking can indeed be pragmatic, yet in paradigmatic ways. In the first section, I will assess the contemporary literature on the role of the local level in the making of policies addressing differentiation and how this is related to the national level. In the following section, I will then discuss the characterization of policies as pragmatic and contrast it with their characterization as paradigmatic. I will investigate the applicability of pragmatism at the local level and the concrete way this pragmatism manifests itself. By analysing the implementation of local ‘diversity policies’ in the three cities, I will show how both pragmatism and paradigms come into play.

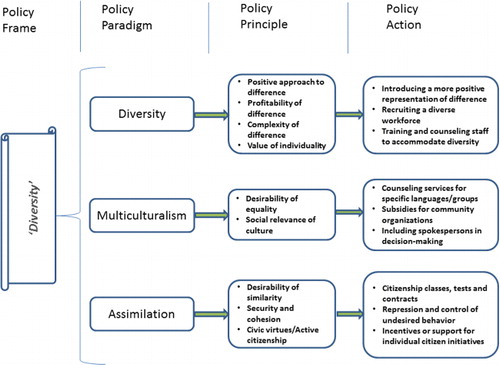

This article demonstrates how diversity policies pragmatically combine different immigrant policy paradigms on the local level. Diversity is a new frame that many cities introduced in order to shift the attention away from the concept of multiculturalism, which has fallen in disgrace. The notion of frame refers to the normative and sometimes cognitive ideas that are located in the foreground of policy debates and strategically crafted by politicians to legitimize their policies (Campbell Citation2002, 27). Looking then further into the ideas, which are appropriated and transported in these diversity policies, I observe two things: the concept of diversity brings in some new ideas on the accommodation of social differentiation. Yet, these ideas are pragmatically combined with ideas developed in earlier immigrant policy paradigms. An immigrant policy paradigm is understood here as a system of ideas reflecting a certain vision or ‘taken-for-granted world view’ (22) on the accommodation of differentiation and heterogeneity. Paradigms such as multiculturalism, assimilation or diversity are thus being pragmatically combined in local policies. I will then also argue that these pragmatic combinations of immigrant policy paradigms are not unproblematic, as their underlying ideas are not always compatible. Actually, they imply often contradictory immigrant policy principles. The pragmatism of local immigrant policies, while responding to the specific needs of cities, may therefore result in an arbitrary politics.

This article brings together some of the debates on a local turn of governing migration and relates to debates on a shift away from multiculturalism. It discusses them in view of the recent development of ‘diversity policies’ in European cities and the theoretical implications of these uses of the ‘diversity’ concept. It aims to unravel how different immigrant policy paradigms become negotiated or drawn upon at the local level. Whether pragmatic combinations of different paradigms result in more sophisticated immigrant policies or whether they result in contradictory policies and a ‘backlash against diversity’ (Vertovec Citation2012) is yet to be seen.

2. Local pragmatism? Assessing the hypothesis

In recent years, the role of the local level and the way that immigrant policies are framed and conceptualized there has increasingly captured the interest of researchers (Caponio Citation2010b). ‘Integration is taking place at the local level’ has become an often-cited formula. It is in cities where globalization and the consequences of migration become most visible, putting the state under pressure to accommodate diversity locally (Penninx and Martiniello Citation2004, 160). The local level at the same time also interacts with regional, national and supranational levels in the governance of migration, as we know from various contributions on the ‘multi-level governance’ of migration (Caponio Citation2010b; Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero Citation2014; Jørgensen Citation2012; Poppelaars and Scholten Citation2008; Scholten Citation2013; Zincone and Caponio Citation2006). One example for such relations across levels of government is the promotion of the particular role of cities for the integration of immigrants by the European Commission as part of its supranational immigrant policy agenda.Footnote1 The national level and its assumed monopoly in determining immigrant policies was challenged in these debates (Penninx and Martiniello Citation2004, 155), raising the interest in the local level. Most recently, a characteristic pragmatism was claimed for the local level (Scholten Citation2013), initiating a discussion about whether a distinct immigrant policy paradigm is evolving there.

A common assumption in the past was that national levels develop the broader policy paradigms, and the local level is implementing these ideas and translating them into practice. This presupposes a clear hierarchy between policymaking and implementation and between national and local level. There are two reasons why this can be refuted: one is the general trend of decentralization in European countries; the other is the increasing interaction and cooperation of cities in city networks. For some contexts, we can find a traditional pattern of the national level conceiving and the local level implementing immigrant policies, where a more central government instruction and/or control in place (Wollmann Citation2004, 659). For instance in the UK, cities were for a long time bound by the strong legal framework providing a context where the national guidelines are relatively important. In Austria, Switzerland and Germany, by comparison, such a national immigrant policy evolved only more recently and many cities had developed their own policies ahead of the national level (Kraler Citation2004; Penninx and Martiniello Citation2004, 158). As we can see, there is no uniform pattern of local or national autonomy and responsibility in immigrant policymaking. (Caponio Citation2010a, 171). The clear separation of national policymaking and local implementation in many cases lost its prevalence as national governments deferred the responsibility for immigrant policies to the local level (Jørgensen Citation2012, 252). Today, many cities have substantial leeway in formulating their own policies. Even in national contexts where the government had fairly strictly controlled city policies, such as the UK, the government decided to reduce their guidance and monitoring of cities (Interview D2 32, D3 110, D4 28, B6 78).Footnote2 However, we should not be misled to think that national contexts are completely irrelevant. The autonomy of cities vis-à-vis national governments is always contingent on political interests and the allocation of responsibilities in a multilevel governance framework.

The exchange between cities through networksFootnote3 and the diffusion of policy concepts and ideas between them was provided as an alternative reasoning for arguing against a clear division of policymaking and implementation between national and local level (Faist and Ette Citation2007, 20; Hadj-Abdou Citation2014, 16). Cities to some degree compete among each other with their individual ideas and concepts, and engage in a sort of ‘branding’ of their policies in order to strengthen their image as innovative and dynamic. Amsterdam's self-depiction as ‘Europe's gay capital’ serves as one example how cities today position themselves and compete in an international market of ‘city brands’ (Jørgensen Citation2012, 248; Kavaratzis Citation2004; Kavaratzis and Ashworth Citation2005). Such a local image may also strengthen cities’ positions vis-à-vis the national level and other cities and contribute to increasing local independence from the guidelines of the national level. In my own research, all three cities of Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds had been involved in such international city networks exchanging immigrant policy ideas and concepts in the past, and they clearly were internationally connected. How important these international links are in comparison to the links to the national government, however, would need more empirical research. Yet, based on my own research, I would argue that international exchanges are certainly a source of inspiration and increasing self-confidence for local governments to define local policies and to not merely follow or copy the national level. As I found in the cities under research, they have become more self-confident and creative in developing their own conceptual frameworks and in interpreting concepts. Leeds’ city council for instance complemented the concept of ‘equality’, reflecting the national legislation, with the concept of ‘diversity’ to create a so-called ‘equality and diversity policy’. Cities also have come to inspire other governance levels with their immigrant policies, as for instance Antwerp's notion of ‘broad diversity’ was later also picked up by the regional level of Flanders. The formulation of ‘civic citizenship’ (burgerschap) policyFootnote4 in Amsterdam in 2011 is another example of how cities are involved in experimenting with immigrant policy concepts and ideas independently from other levels. The civic citizenship policy was based on the political adviser's idea of appropriating John Rawls’s concept of ‘civility’ (Rawls Citation1971), which she was familiar with due to her graduate studies. The local level is thus involved in the formulation of policy ideas and we can no longer assume that cities depend or simply implement nationally formulated policies.Footnote5 By doing so, cities may contribute to the evolution of new or the adaptation of existing immigrant policy paradigms.

I acknowledged that cities may have become more active or have received more leeway in designing their own policies. But do local immigrant policies have a decidedly different character than national policies? According to Poppelaars and Scholten (Citation2008), the policies on the local level differ from those on the national level because of their different ‘institutional logics’. We would find a more instrumental or pragmatic logic of the local level, oriented towards ‘coping with concrete problems’, whereas policymaking on the national level would be more abstract or idealist, oriented towards creating the larger ideational policy framework (Penninx and Martiniello Citation2004, 160; Poppelaars and Scholten Citation2008).Footnote6

What exactly Scholten means by using the concept of pragmatism and how pragmatism can be expected to inform the development and implementation of immigrant policies at the local level, however, still leaves room for discussion. In the online Oxford English Dictionary, pragmatism is defined as:

The doctrine that an idea can be understood in terms of its practical consequences. … The theory that social and political problems should be dealt with primarily by practical methods adapted to the existing circumstances, rather than by methods which have been conformed to some ideology.

One example that is frequently given to substantiate the ‘local pragmatism’ hypothesis is the use of contacts of ethnic community organizations in post-multicultural policy settings. Many local governments continue to address ethnic minorities as collectives, although targeting ethnic groups is seen as a thing of the past as it would pertain to a paradigm of multiculturalism. The reason for this is that local officials need the contact with minority communities in order to identify disadvantages in society and to address them. It means that members of minority groups are singled out of practical considerations, and paradigmatic considerations are put on hold (Caponio Footnote2010a, 180; Jørgensen Citation2012, 273).

There are several reasons why local policies may indeed be pragmatic sometimes. If we assume that Penninx and Martiniello (Citation2004) are right in postulating that local politicians and officials are often in very close contact with the local population and have to resolve more immediate and concrete issues than the national level, pragmatism appears as a useful disposition. Yet, I am not entirely convinced that there is a clear division between national and local level in terms of closeness vs distance of politicians and the population and abstract vs concrete character of policy problems. Are local-level policies necessarily and at all times pragmatic, while national-level policies are informed by one or the other paradigm? Maybe there is a higher likelihood that local politicians are more often in direct contact with their constituency and that the problems are more concrete – but I contest that this is so all the time and in all cases. The local pragmatism hypothesis invites empirical investigation and I will present my findings from Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds in the following section.

3. New ideas, pragmatically combined: diversity policies in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds

In the past fifteen years, many cities in Europe changed their immigrant policies to react to a perceived crisis of multiculturalism. The 2001 riots in Leeds, the murder of Theo van Gogh in Amsterdam and the increasing pressure of the political right in Antwerp epitomized this discourse of a crisis of previous policy paradigms at the local level and created the feeling that new policy concepts were needed. Many cities replaced their local policies, which were more multicultural in character, and introduced ‘diversity’ policies. Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds are three cases in point, as they are all located in national and regionalFootnote7 contexts where the notion of multiculturalism was contested in public discourse, triggered by the riots in northern UK cities in 2001 and the London bombings of 2005 (Eade et al. Citation2008), public debates on a ‘failure of multiculturalism’ instigated by Pim Fortuyn, Paul Scheffer and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands (Entzinger Citation2003; Penninx, Garces-Mascarenas, and Scholten Citation2005; Vasta Citation2007), and the change in the composition of the regional government in Flanders (Adam Citation2011; Gsir Citation2009; Motmans and Cortier Citation2009). Politicians in these national and regional contexts subsequently avoided the term ‘multiculturalism’, erasing it from their vocabulary (Interview B1 506, B2 438, B6 29), and introduced local ‘diversity’ policies. By changing the frame of policies, local governments wanted to acknowledge the concerns of the public and symbolize a change in direction. As I will show in the following, these new policy frames, however, also implied a change in underlying paradigms. Activities in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds carried out under the header of ‘diversity’ are at the same time paradigmatic as they are pragmatic. On the one hand, they transport distinct ideas on accommodating social differentiation; on the other, they are fairly pragmatic in combining these ideas with other, previous ideas on sameness and difference under the frame of ‘diversity’.

3.1. Diversity as a new frame and new ideas

The introduction of the new policy frame of ‘diversity’ in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds clearly followed a pragmatic rationale. It allowed politicians to communicate a change from previous multicultural policies that were increasingly discredited in public discourse. ‘Diversity’ symbolized a change from what has become seen as a problematic multicultural politics, with each city having had a particular event or pressure that made such a change seem relevant. In Antwerp, diversity policy was used to signal the proactivity and productivity of the municipality after the landslide victory of the far right in the 2000 elections. In Leeds, the municipality wanted to redefine the city's approach to equality and introduce new concepts after the riots in 2001. In Amsterdam, diversity was used to symbolize the overturning of the previous minorities’ policy, which had become discredited in public debates over the years. Diversity was already introduced here in 1999, but it was challenged and adapted after the murder of Theo van Gogh in 2004. Diversity thus is becoming used as an official policy term in cities, replacing or being added to terms such as ‘minorities’ policy’ or ‘equality policy’.Footnote8

Contrary to what some authors claimed, diversity was not only a new frame, but in the cities under research it also provided distinct immigrant policy ideas. The ‘diversity policy’ texts in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds put the emphasis on accepting diversity as a fact, as something positive and profitable. They focused on the individual (instead of the group in multicultural approaches) and on various categories of difference (addressing ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, disability, religion). These principles differ from those that guided immigrant policies previously. As such, the introduction of ‘diversity’ could be interpreted as a new locally adopted immigrant policy paradigm.

The characteristic ideas of a diversity paradigm were reflected in the policy texts of the three cities in my research (GA Citation1999; LCC Citation2006; SA Citation2008). below provides some examples of the underlying principles of diversity in cities’ policy texts and individual officers’ statements and demonstrates the similarity of definitions of diversity in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds.

Table 1. Meanings ascribed to diversity in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds.

Diversity was not only a new frame, but it also proposed new immigrant policy ideas. Diversity is thus also ideologically charged, transporting a specific version and potential immigrant policy ‘paradigm’.

3.2. Combinations of diversity with other immigrant policy paradigms

So far I have demonstrated how diversity transports some new ideas and has some paradigmatic quality. However, diversity policies do not necessarily do away with previous immigrant policy paradigms, but are rather pragmatic in accommodating and incorporating these.

As Vertovec and Wessendorf (Citation2010, 18) argued, a seismic shift of policies away from multiculturalism has failed to appear. Thus, the introduction of a new idea may well go hand in hand with continuing some of the existing paradigms, as my empirical data confirm. Diversity policies in Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds often incorporated earlier immigrant policy ideas, as they lived on in some of the activities of municipal diversity units. Manifestations of a multiculturalism paradigm, for example, were still present in the context of these local diversity policies. There are numerous definitions of multiculturalism, but two key principles can be defined to be at multiculturalism's core: cultural recognition and social equality and participation (Vasta Citation2007, 7). Multiculturalism bestows value on cultural pluralism and emphasizes the rights of migrants to hold on to their cultural belongings. The state is meant to ensure that cultural groups are recognized (Faist Citation2009, 176). In local practice, this was often implemented by identifying ‘target groups’ that received specific attention or funds by state institutions. In the cities under research, activities targeted at specific groups or activities to tackle discrimination were still relevant and practised. In Amsterdam, for instance, there was still a programme for people of Caribbean origin and one particularly targeted at lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in 2010 – ten years after diversity policy was introduced there.

Combining different immigrant policy ideas under the header of diversity policy is pragmatic. Some methods that municipal organizations have developed in the context of multicultural policies may still be useful for dealing with particular issues, even if the idea of recognizing culture or fostering equality is no longer pursued. Maintaining contacts with ethnic minorities, as mentioned earlier, indeed seemed to be of continued relevance in Amsterdam and Leeds, where some officials were in charge of maintaining those links. The foundational policy document for diversity policy in Amsterdam (GA Citation1999, 13) illustrates how diversity was from the outset meant to build on previous policies: ‘Building blocks of the new diversity policy can be found in the policies in the area of women's emancipation, homo-emancipation and minorities policy’. Continuing with older policy activities is also pragmatic, as municipal organizations are sometimes slow-moving bureaucratic structures (Hambleton and Gross Citation2007, 162), and it simply takes much more time to change ways of working and ongoing activities than it does to change the overarching policy. Also, changing a policy concept does not usually go hand in hand with an encompassing replacement of the structures in place for implementing these policies, and staff who previously worked in a different policy regime may not immediately identify with new concepts and ideas. Transforming the activities and ways of working of so-called diversity teams and team members to reflect a new policy then is a lengthy and slow process. It may be resisted and challenged, particularly by those team members who had identified with a previous policy paradigm. In Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds, the existing teams were not entirely resolved when diversity was introduced as a new policy frame (although eventually there was a thorough change of officers). Some staff members from previous units have left, some stayed, and some new members joined. Previously separate teams working on categories such as gender, ethnicity, class, ability or sexual orientation were merged and officials from these different teams suddenly had to collaborate. Officials had often strongly identified with their particular categorical policy and did not necessarily find it desirable or easy to switch to a diversity framework. This was the case with a unit focusing on poverty in Antwerp, which became integrated in the new diversity unit. The specific attention for poverty in the framework of diversity in Antwerp was a remnant from earlier structures, that some officers continued to work on (Interview C11 167). Merging structures to create a diversity unit did not therefore automatically change the entire way of thinking and working of local officials.

Diversity policy ideas were also combined with emerging ideas of securitization and responsibilization. As was the case with the notion of community cohesion in Leeds, concepts were introduced incidentally and complemented the diversity policy. Community cohesion, specifically, was seen by diversity officers in Leeds as an interim step in the evolution of their policy. According to one officer, they just had to introduce ‘community cohesion’ in order to ‘play the game’, thus taking a pragmatic approach in accepting a new concept. The diversity unit's officials expected that community cohesion would lose its currency, but they had to promote it as a separate policy element for some time. Eventually it would become part of their activities, resulting in a more comprehensive substance of ‘equality and diversity’ (Interview B3 559). Introducing the concepts of community cohesion was seen as useful to strengthen the conceptual framework of diversity, but also to bolster the available structures for working on diversity. It served to expand the responsibility of individual diversity officers, allowed access to additional staff resources and budget (Interview A13 377), and triggered a collective redefinition of the team's tasks (Interview A2 83). Similarly, the concepts of ‘anti-radicalization’ and ‘civic citizenship’ in Amsterdam were introduced to complement the existing diversity framework and resulted in additional human resources and the creation of new job positions.

What we thus see happening is cities using ‘diversity’ as a new frame to refer to their policies dealing with the accommodation of differentiation (, first column). The politics under this term often reflect a pragmatic confluence of paradigms of multiculturalism, assimilation, and an evolving paradigm of diversity (, second column). We can identify what I would call a ‘paradigmatic pragmatism’ at the local level. All these paradigms suggest their respective principles of how differentiation can best be accommodated (, third column). They have very different starting points, which I will discuss in the following section, and they become enacted in a variety of activities (, fourth column).

3.3. Paradigmatic pragmatism: contradictions and incompatibilities

The combination of different policy paradigms is not necessarily a harmonious affair and can be quite challenging in practice. While some principles of diversity, multiculturalism and assimilation may be compatible, others may conflict. For instance, the emphasis on cohesion (as part of an assimilationist paradigm) diverges from the principle of the profitability of difference (as part of a diversity paradigm). These two policy principles start out from a contrasting evaluation of difference: one emphasizing the negative potential of difference and aiming to control behaviour; the other stressing the positive value of difference and fostering diversity. Another example of a challenging relationship can be observed between the principles of difference being profitable (diversity paradigm) and equality (multiculturalism paradigm). In these principles, we can detect a contrast of an economically based rationale and a rationale that orients itself on ideas of social equality. They may not necessarily conflict, but their relationship is not an easy one. A third conflict-prone relationship comes to the fore when an assimilation paradigm combines with diversity and/or multiculturalism paradigms. The principle of a desirability of similarity (assimilation paradigm) contrasts with both the principle of difference as profitable (diversity paradigm) and the principle of culture as needing to be recognized (multiculturalism paradigm). While the former principle favours differences to become levelled out, the principles adhering to diversity and multiculturalism accept difference as a permanent and valuable aspect of social reality.

When activities reflecting different policy paradigms are pursued in parallel, we can expect some troubles. However, diversity officers themselves saw multiculturalism and diversity paradigms and related principles mostly as compatible. One would need to address particular groups in order to address diversity, as one of Antwerp's diversity officers said:

You have to choose, for example when it is about the topic of health and diabetes, which groups have more diabetes than the average citizen. And these groups you then have to work on, I find. … Choosing to work on a specific target group is, if you ask me, beneficial for diversity. (Interview C12 249)

Equality and diversity sit side by side, because obviously equality is about equality of access and equal opportunity. Diversity is about recognizing that everyone’s different. So people often see them as clashing, but equality is not about giving everyone the same thing, because not everyone wants the same thing, men and women might have different needs in service provision, different communities or residents of different ethnic origin might have different needs. The equality aspect of it is whether they both have an equal chance of getting what they want. (Interview B2 369)

Table 2. Reflection of different immigrant policy principles in Amsterdam's work programmes.

Civic citizenship and anti-discrimination, for instance, reflect paradigms of assimilation and multiculturalism, which are often seen as contradictory. Yet, these policy programmes were pursued in parallel in Amsterdam. As one diversity officer said:

You have to work on two tracks. On the one hand, how can you facilitate encounters, how can you create a better understanding of people for each other, how can you emphasize diversity in a positive manner? And at the same time: how can you work on the integration of groups that lag behind? Thus a policy that is addressing deficits is still necessary, and how can you work on the difficult issues. Thus these were all elements that came back in that. (Interview A6 162)

And actually everything that the city does is targeted at the middle class. … This is where the entire budget is going to. They do want to work on diversity, … but if then ethnic minority people suddenly come, if poor people come, suddenly the atmosphere is changing. And actually they don’t want it [that they come], because the middle class is sensitive to that. Ethnic minority people may come, as long as they belong also to the middle class, workers may come, but they have to fit into our middle class pattern …, everyone may come, but we don’t change our concept. Because we middle class want that everything stays as it was. And sometimes I would really wish that it [diversity policy] was for everyone. (Interview C6 169)

From the empirical evidence, I can thus confirm that different policy paradigms are pragmatically combined in the three cities under research. Yet, these combinations are not always without insecurities or tensions. Sometimes diversity officers pursued contradictory policy principles in parallel, but at other moments combinations become challenged. In these cases, it was often the activities that reflected remnants of older paradigms of accommodating differentiation that were eventually abandoned. This was the case with a particular programme for residents of Caribbean origin in Amsterdam, which reflected a more multicultural paradigm.Footnote10 Likewise, specific activities adhering to the principle of security and control in Leeds were at some point scaled down and subordinated to principles of equality and the profitability of difference. Contrary to the assumption that local immigrant policies are characterized by pragmatism, I have shown how local governments draw on new and old paradigms, which they combine.

Combining different paradigms of accommodating differentiation was a pragmatic choice of the cities under research. The combination of different immigrant policy principles allows them to pursue a variety of activities in parallel and to have structures and staff to deal with different aspects of diversity. However, it also created instances of a contradictory politics. For the development of diversity as an immigrant policy paradigm, such contradictions are likely to cast doubt on the potential and theoretical saturation of this new concept and may well lead to a ‘backlash against diversity’ (Vertovec Citation2012).

4. Conclusions

In this paper, I have investigated the hypothesis of pragmatism as characteristic of the local governance of diversity based on of empirical evidence from the cases of Amsterdam, Antwerp and Leeds. I formulated the question of whether a local character of policies can be separated from a national character of policies and if so how can we characterize local policies for accommodating differentiation and heterogeneity. In which ways are contemporary diversity policies informed by paradigms and by pragmatism?

I argued against a dichotomy of the national level as paradigmatic and the local level as pragmatic. Local governments also draw on paradigms and they do so to formulate responses to concrete local pressures. Thus, they are pragmatic in the way that they handle paradigms and they are paradigmatic in having a set of ideas to guide their actions. Cities then are ‘paradigmatic pragmatists’ – they draw on a variety of normative frameworks on how to address differentiation and heterogeneity and pragmatically combine these different paradigms to address the mobilization of difference in the city.

Such a paradigmatic pragmatism was identified in all three cities. The official rejection of multiculturalism and the emergence of new, but not yet quite established and refined paradigms, such as diversity, may well provide a favourable context for combining different normative frameworks in pragmatic ways. Whether paradigmatic pragmatism is a broader characteristic of contemporary local policymaking on the mobilization of difference, and if so, how exactly does it manifest in different cities provides scope for further empirical investigations. National contexts and multi-level governance arrangements may allow for the pragmatic pragmatism of cities to different degrees. Not all cities can draw on the same paradigms and they might combine them in different ways. Combinations of paradigms will therefore not be uniform across cities and locally specific pressures and multilevel governance arrangements will inform the particular character of policymaking in each local context.

For policymakers, this implies weighing the risk of potential contradictions against the gains of pragmatic combinations. Potential contradictions may disqualify and lead local governments to abandon the diversity concept, but pragmatic combinations may allow for tailored answers to the variety of issues that policymakers face. Researchers could not only further theoretically elaborate the diversity concept; they could also provide further empirical analyses of the conflicts arising from incompatible principles and the effects of paradigmatic pragmatism as well as in-depth studies of the practices of the actors involved. There is still much scope for future research to assess the local character of immigrant policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Schiller

MARIA SCHILLER is Post-Doctoral Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.

Notes

1. The first mention of the importance of involving local authorities in the European Framework of Integration was in the Hague Programme in 2004. The Common Basic Principles for Immigrant Integration Policy in 2004 underlined the role of different levels of government for integration (Carrera Citation2009). The communication ‘A Common Agenda for Integration’ (European Commission Citation2005, 389) claims that ‘in reality integration takes place at the local level as part of daily life’ (Carrera 2009). At the 2008 ministerial conference on integration in Vichy, the need to involve local authorities in planning, implementing and evaluating immigrant policies was emphasized (European Commission Citation2011). The local dimension of immigrant policymaking was promoted through various programmes such as CLIP (by Eurofound), EUROCITIES projects (Dive, Inticities and Mixities, Implementoring) and the European Fund for the Integration of Third Country Nationals.

2. For a more extensive discussion of my interview material please see my forthcoming book entitled European Cities, Municipal Organizations and Diversity: The New Politics of Difference, published by Palgrave. For reasons of anonymisation I refer here to my interviews by using a capital letter for the city, a first number for the individual, and a second number for the specific line in the interview transcript.

3. CLIP, EUROCITIES, Intercultural Cities, Open Cities, Mile and Eccar are just a few examples.

4. The notion refers to a new way of relating with citizens and an emphasis on the responsibility of citizens for their behaviour by emphasizing civic virtues.

5. We need to also acknowledge the various interchanges that local and national governments are involved in. Policy formulation on one level thus can, for instance, result in the formulation of similar policies on a different level, such as in the case of Antwerp’s policy being copied with some adaptations by the Flemish government and the regional level thus following the local level. We therefore need to be careful not to conceptualize the local and national level as sealed off from each other. Local integration policies are the result of deliberation on and across different levels of governance and the specificities of city governments.

6. Poppelaars and Scholten (Citation2008) also argued that the national level would more strongly be subject to pressures from the electorate.

7. The regional context of Flanders is the more important level of government for informing local immigrant policies in the Belgian context. Flemish immigrant policies have been traditionally inspired by Dutch policies (Blommaert and Martens Citation1999; Adam Citation2011).

8. Different frames for immigrant policies may also compete with each other. Diversity, as one such frame, may therefore be combined or replaced by other frames over time, just as it has been added to or replaced earlier frames. Such a competition of principles can be observed in Amsterdam today, where ‘civic citizenship’ is competing with ‘diversity’ as the frame for the city’s immigrant policy.

9. In its Development Strategy: Civic Citizenship and Diversity, the municipality emphasized that different programmes should not lead to separate but integrated policy activities and therefore intends to further strengthen the frame of ‘burgerschap and diversity’.

10. The reasons given for abandoning this programme were partly the withdrawing of some funding that had been coming from the national level. However, the programme had already been seen for some time as an outlier within the unit and no longer really fitting into the diversity framework. The withdrawal of national funding thus seemed a convenient moment to abandon it.

References

- Adam, I. 2011. “Une approche différenciée de la diversité. Les politiques d’intégration des personnes issues de l’immigration en Flandre, en Wallonie et à Bruxelles (1980–2006) [A Differentiated Approach to Diversity. The Integration Politics Targeted at Immigrants in Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels (1980-2006)].” In Le droit et la diversité culturelle [The Law and Cultural Diversity], edited by J. Ringelheim, 251–300. Louvain-la-Neuve: Bruylant.

- Alexander, M. 2007. Cities and Labour Immigration: Comparing Policy Responses in Amsterdam, Paris, Rome and Tel Aviv. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Allen, J., and G. Cars. 2001. “Multiculturalism and Governing Neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 38 (12): 2195–2209. doi:10.1080/00420980120087126.

- Blommaert, J., and A. Martens. 1999. Van blok tot bouwsteen. Een visie voor een nieuw migrantenbeleid [From Block to Building Stone: A Vision for a New Migrant Policy]. Berchem: Epo.

- Campbell, J. 2002. “Ideas, Politics, and Public Policy.” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (1): 21–38. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141111.

- Caponio, T. 2010a. “Conclusion: Making Sense of Local Migration Policy Arenas”. In The Local Dimension of Migration Policymaking, edited by T. Caponio and M. Borkert, 161–195. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Caponio, T. 2010b. The Local Dimension of Migration Policymaking. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Carrera, S. 2009. The Role and Potential of Local and Regional Authorities in the EU Framework for the Integration of Immigrants. Brussels: Study commissioned by the Commission for Constitutional Affairs, European Governance and the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice of the Committee of the Regions.

- Collins, F. L., and W. Friesen. 2011. “Making the Most of Diversity? The Intercultural City Project and a Rescaled Version of Diversity in Auckland, New Zealand.” Urban Studies 48 (14): 3067–3085. doi:10.1177/0042098010394686.

- Eade, J., M. Barrett, C. Flood, and R. Race. 2008. Advancing Multiculturalism, Post 7/7. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

- Entzinger, H. 2003. “The Rise and Fall of Multiculturalism: The Case of the Netherlands.” In Towards Assimilation and Citizenship: Immigration in Liberal Nation-states, edited by C. Joppke and E. Morawska, 59–86. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- European Commission 2005. “Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Common Agenda for Integration: Framework for the Integration of Third-Country Nationals in the European Union.” COM(2005)389 final. Accessed December 18, 2014. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2005:0389:FIN:EN:PDF.

- European Commission 2011. “Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: European Agenda for the Integration of Third-Country Nationals.” SEC(2011)957 final. Accessed December 18, 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/news/intro/docs/110720/1_en_act_part1_v10.pdf.

- Faist, T. 2009. “Diversity – A New Mode of Incorporation?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32: 171–190. doi:10.1080/01419870802483650.

- Faist, T., and A. Ette. 2007. The Europeanization of National Policies and Politics of Immigration. Between Autonomy and the European Union. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gemeente Amsterdam. 1999. De kracht van een diverse stad [The Strength of a Diverse City]. Amsterdam: Gemeente Amsterdam.

- Gemeente Amsterdam. 2013. Ontwikkelingsstrategie burgerschap en diversiteit [Development Strategy Civic Citizenship and Diversity]. Amsterdam: Gemeente Amsterdam.

- Garcia, M. 2006. “Citizenship Practices and Urban Governance in European Cities.” Urban Studies 43 (4): 745–765. doi:10.1080/00420980600597491.

- Glick Schiller, N., and A. Caglar. 2010. Locating Migration: Rescaling Cities and Migrants. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Gsir, S. 2009. Diversity Policy in Employment and Service Provision. Case Study Antwerp, Belgium. Dublin: Eurofound.

- Hadj-Abdou, L. 2014. “Immigrant Integration and the Economic Competitiveness Agenda: A Comparison of Dublin and Vienna.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (12): 1875–1894. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.887462.

- Hambleton, R., and J. S. Gross, eds. 2007. Governing Cities in a Global Era: Urban Innovation, Competition and Democratic Reform. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hepburn, E., and R. Zapata-Barrero, eds. 2014. The Politics of Immigration in Multi-level States: Governance and Political Parties. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jørgensen, M. B. 2012. “The Diverging Logics of Integration Policy Making at National and City Level.” International Migration Review 46 (1): 244–278. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2012.00886.x.

- Kavaratzis, M. 2004. “From City Marketing to City Branding: Towards a Theoretical Framework for Developing City Brands.” Place Branding 1 (1): 58–73. doi:10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990005.

- Kavaratzis, M., and G. J. Ashworth. 2005. “City Branding: An Effective Assertion of Identity or a Transitory Marketing Trick?” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 96 (5): 506–514. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00482.x.

- Kraler, A., ed. 2004. Immigrant and Immigration Policy Making –A Survey of the Literature: The Case of Austria. Vienna. Accessed December 18, 2014. http://politikwissenschaft.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/inst_politikwiss/Kraler/Austria_Country_Report_Revised.pdf.

- Leeds City Council. 2006. Equality and Diversity Strategy 2006–08. Leeds: Leeds City Council.

- Motmans, J., and E. Cortier. 2009. Koken in dezelfde keuken? Onderzoek naar de mogelijke invulling van een Vlaams geintegreerd gelijkekansen- en/of diversiteitsbeleid [Cooking in the Same Kitchen? Research on the Possible Conception of an Integrated Flemish Equal Opportunities or Diversity Policy]. Antwerpen: Steunpunt Gelijkekansenbeleid.

- Neill, W. J. V., and H.-U. Schwedler. 2007. Migration and Cultural Inclusion in the European City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nicholls, W., and J. Uitermark. 2013. “Post-multicultural Cities: A Comparison of Minority Politics in Amsterdam and Los Angeles, 1970–2010.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (10): 1555–1575. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.833686.

- Oxford English Dictionary. “ pragmatism, n.” Oxford University Press. Accessed December 18, 2014. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/149295?redirectedFrom=pragmatism.

- Penninx, R., B. Garces-Mascarenas, and P. Scholten, eds. 2005. Policy-making Related to Immigration and Integration: A Review of the Literature on the Dutch Case. Amsterdam. Accessed December 18, 2014. http://dare.uva.nl/cgi/arno/show.cgi?fid=39852.

- Penninx, R., and M. Martiniello. 2004. “Integration Processes and Policies: State of the Art and Lessons.” In Citizenship in European Cities: Immigrants, Local Politics and Integration Policies, edited by R. Penninx, K. Kraal, M. Martiniello, and S. Vertovec, 139–163. New York: Ashgate.

- Poppelaars, C., and P. Scholten. 2008. “Two Worlds Apart: The Divergence of National and Local Immigrant Integration Policies in the Netherlands.” Administration and Society 40 (4): 335–357. doi:10.1177/0095399708317172.

- Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Stadt Antwerpen. 2008. Stadsplan diversiteit 2008–12 [City Plan Diversity 2008–12]. Antwerp: Stadt Antwerpen.

- Scholten, P. W. A. 2013. “Agenda Dynamics and the Multi-level Governance of Intractable Policy Controversies: The Case of Migrant Integration Policies in the Netherlands.” Policy Science 46 (3): 217–236. doi:10.1007/s11077-012-9170-x.

- Uitermark, J. 2010. Dynamics of Power in Dutch Integration Politics: From Accommodation to Confrontation. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press.

- Vasta, E., ed. 2007. Accommodating Diversity: Why Current Critiques of Multiculturalism Miss the Point. Oxford. Accessed December 18, 2014. www.compas.ox.ac.uk/fileadmin/files/Events/Events_2007/WP075%20Accom%20Div%20Vasta.pdf.

- Vermeulen, F., and T. Plaggenborg. 2009. “Between Idealism and Pragmatism: Practitioners Working with Immigrant Youth in Amsterdam and Berlin.” In City in Sight: Dutch Dealings with Urban Change, edited by J. W. Duyvendak, F. Hendriks, and M. Van Niekerk, 203–222. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Vertovec, S. 2012. “‘Diversity’ and the Social Imaginary.” European Journal of Sociology 53 (3): 287–312. doi:10.1017/S000397561200015X.

- Vertovec, S., and S. Wessendorf. 2010. The Multiculturalism Backlash: European Discourses, Policies and Practices. New York: Routledge.

- Wollmann, H. 2004. “Local Government Reforms in Great Britain, Sweden, Germany and France: Between Multi-function and Single-purpose Organisations.” Local Government Studies 30 (4): 639–665. doi:10.1080/0300393042000318030.

- Zincone, G., and T. Caponio. 2006. “The Multilevel Governance of Migration.” In The Dynamics of International Migration and Settlement in Europe: A State of the Art, edited by R. Penninx, M. Berger, and K. Kraal, 269–304. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.