ABSTRACT

The concept of super-diversity has been widely evoked – sometimes in highly misleading ways. Based on a survey of 325 publications across multiple disciplines, this special issue endword piece presents a typology of ways of understanding super-diversity. This includes addressing super-diversity as: a contemporary synonym of diversity, a backdrop for a study, a call for methodological reassessment, a way of simply talking about more ethnicity, a multidimensional reconfiguration of social forms, a call to move beyond ethnicity, and a device for drawing attention to new social complexities. Indeed, I believe the latter – the search for better ways to describe and analyze new social patterns, forms and identities arising from migration-driven diversification – is perhaps the most driving reason for expanding interests and uses, however varied, surrounding the concept of super-diversity.

These days, there is a substantial amount of talking around super-diversity. There is also talk about super-diversity. Across a range of social scientific terrains, the concept of super-diversity is variably invoked, referenced, concocted or criticized as an idea, setting, condition, theory or approach. Sometimes such talking is really about the concept; that is, discussions ensue with reference to its original meaning or intention. Other times, super-diversity is merely a prompt around which the talk is actually about something else – a springboard to present a set of related research findings, a segue to another topic, or indeed a false starting point, misnomer or sheer strawman. Such divergence is surely OK – indeed, that’s what happens to many scholarly ideas, concepts and theories. Once a notion is “out there”, its development takes on a life of its own. Multiple understandings, misunderstandings and misuses arise – and such conceptual evolution (including mutation) mostly moves social science forward.

But listeners should be offered more clarity concerning the ways a concept is being talked about or around. A caricatured concept does no one any good. In the following brief essay, I outline some of the ways super-diversity has been talked about and around, including some ways represented by contributions to this special issue.

I start with a necessary re-cap of the concept and its original intention. “Super-diversity” was intended to give a name to changing patterns observed in British migration data. It was clear in various statistics (presented in the original article), that, over a period of twenty years or so, the UK had witnessed not just new movements of people reflecting more countries of origin (entailing multiple ethnicities, languages and religions), but – along with these patterns, and differentially reflecting or comprising the new country-of-origin flows, there have been shifts in:

differential legal statuses and their concomitant conditions, divergent labour market experiences, discrete configurations of gender and age, patterns of spatial distribution, and mixed local area responses by service providers and residents. The dynamic interaction of these variables is what is meant by “super-diversity”. (Vertovec Citation2007, 1025)

In these ways, I have always advocated super-diversity as (merely) a concept and approach about new migration patterns. It is not a theory (which, for me, would need to entail an explanation of how and why these changing patterns arose, how they are interlinked, and what their combined effects causally or necessarily lead to). However, for all sorts of reasons, since 2007 super-diversity has been taken up by a wide variety of scholars from an array of disciplines and fields, in myriad (sometimes helpful, sometimes obfuscating, sometimes brilliant) ways and for multiple (sometimes poignant, sometimes curious) purposes. The same can be said of the various ways super-diversity has been used in policy circles – in relation to integration, health, social services and education – and in public debates among NGOs and think-tanks, media outlets and internet forums – concerning issues such as immigration, diversity and urban development [for a fuller discussion of the many understandings of super-diversity, see the online lecture “Super-diversity as concept and approach” at www.mmg.mpg.de].

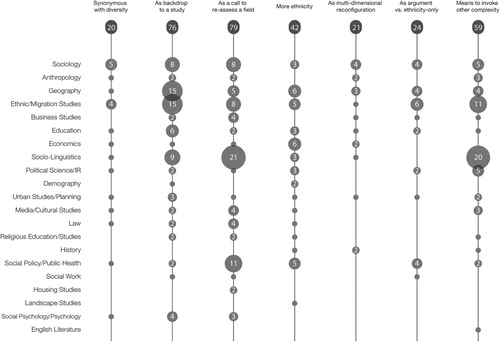

Since the publication of the Ethnic and Racial Studies article “Super-diversity and its implications” in 2007, the term “super-diversity” has been picked up across a surprising range of disciplines and fields. There is certainly no consensus on its meaning “out there”. Hence, it is disingenuous if not outright wrong to suggest, as some have done, that “super-diversity scholars” mean such-and-such (for instance, “happy conviviality”) by the term. The multiple meanings of “super-diversity” are evident in a limited exercise that traced ways that the term has been invoked or employed in academic literature. Together with a research assistant, Wiebke Unger, I acquired 325 publications between 2008 and 2014 through broad online searches for the term. The results of the review were interesting and telling.

Uses of super-diversity: a typology

Firstly, there is considerable disciplinary spread of articles referring to super-diversity. These go well beyond the expected ones – Sociology, Anthropology, Geography and Political Science as well as the multidisciplinary fields of Migration and Ethnic Studies – to include Linguistics and Socio-Linguistics, History, Education, Law, Business Studies, Management, Literature, Media Studies, Public Health, Social Work, Urban Planning and Landscape Studies. Moreover, while the original article described phenomena in London and the UK, the term has been used subsequently to describe social, cultural and linguistic dynamics in such widespread contexts as Brussels, Venice, New York, Jerusalem, the Baltic states, Italy, Cyprus, Egypt, Nigeria, French Guiana, Zimbabwe, Hong Kong, Hokkaido, Oaxaca, villages of south-west Slovakia, the German state of Brandenburg, the border province of Limburg, Manenberg township in Cape Town, and Enshi in China.

Across all of these disciplines and research contexts, we can see at least seven ways that the concept of super-diversity has been used (so far) [Note: this typology is certainly not intended as particularly scientific: it is based on my reading of the ways that various authors have used the concept of super-diversity. The authors themselves may well context my reading].

Very much diversity

(1) Some social scientists have understood super-diversity as a term that is basically synonymous with “diversity”, or perhaps meaning very much diversity. This has included attention to more pronounced kinds and dimensions of social differentiation – particularly cultural identities. A few examples are works that refer to super-diversity in terms of: ways of thinking about difference (Baycan and Nijkamp Citation2012; Mavroudi Citation2010), “diversity, or what recently has been called ‘superdiversity’” (Hüwelmeier Citation2011, 450), “emerging cultural and demographic diversity” (Svenberg, Skott, and Lepp Citation2011, 2), “multiple dimensions of differentiation” (Kandylis, Maloutas, and Sayas Citation2012, 268), “significant demographic change and diversification” (Aspinall and Song Citation2013, 548) and “classification encompassing dozens of different cultures and nationalities” (Aspinall Citation2009, 1425).

Backdrop to a study

(2) A very common way that super-diversity has been used in many articles is merely as a backdrop to a study. That is, scholars invoke super-diversity as a new condition or setting, and then carry on with describing whatever set of research findings they wish to present (that more often than not don’t really have much directly to do with super-diversity). In this way, we have seen copious, scene-setting statements about “‘super-diverse’ places” (Osipovič Citation2010, 212), “superdiverse circumstances” (Jørgensen Citation2012, 57), “a stage of ‘super-diversity’” (Colic-Peisker and Farquharson Citation2011, 583), “the superdiverse condition” (Neal et al. Citation2013, 309), “super-diverse realities” (Juffermans Citation2012, 33), “a super-diverse society” (Hawkey Citation2012, 175), “a ‘super-diverse’ world” (Jacquemet Citation2011, 494), “this time of ‘super-diversity’” (Catney, Finney, and Twigg Citation2011, 109) and an “era of super-diversity” (Burdsey Citation2013).

Raising super-diversity is also sometimes a way of setting up a strawman argument. As we have seen a number of times in this special issue, this includes dubious argumentative strategies such as commencing an article by pointing to Wessendorf’s (Citation2014) book Commonplace Diversity, suggesting it portrays super-diversity as the ubiquitous new normal (and a happy one at that), assuming therefore that this is what the super-diversity concept means writ large, and then proceeding to describe some instance in which diversity has not brought normalcy and happiness – or to point out the obvious, that racism or class remains important – and that therefore super-diversity is a poor or misguided concept. Such arguments entail a gross misrepresentation of super-diversity as well as Wessendorf’s data and proposition (for one who actually reads the book, it is clear that Wessendorf underlines the specificity of Hackney, stresses that racism and class tensions are ever present, and that – despite a “normalized” perception of multiple differences in certain public places – people remain quite separate in their private spheres).

Methodological reassessment

(3) Also by way of setting up a study or argument, the changing, multidimensional patterns referred to as super-diversity, and the intersectional approach it calls for, have also been underlined by scholars in order to urge a methodological reassessment of their respective field or discipline. Here, for example, Blommaert (Citation2013, 6) has stressed

the paradigmatic impact of super-diversity: it questions the foundations of our knowledge and assumptions about societies, how they operate and function at all levels, from the lowest level of human face-to-face communication all the way up to the highest levels of structure in the world system.

Leone (Citation2012, 189) notes that in key migrant-receiving societies, “it is increasingly found that the conceptual framework of ‘cultural integration’, predominant thus far in social research and policy making about social cohesion and harmony, is largely unsatisfactory in dealing with the challenges of the so-called super-diverse cities”.

Appeals for conceptual and methodological re-tooling have been strong in social policy fields. For instance, the conditions of super-diversity have prompted assessments that “policies and discourses need updating in order to match and facilitate new multicultural realities” (Colic-Peisker and Farquharson Citation2011, 583). Yildiz and Bartlett (Citation2011) make a similar case regarding super-diversity and public services, especially surrounding health, just as Phillimore (Citation2013) does for housing, while Newall, Phillimore, and Sharpe (Citation2012, 22) argue that

The complexity associated with superdiverse populations, combined with lack of funds or political will to develop specialist services, means it will not be easy to improve migrant women’s experiences of maternity in the UK unless universal maternity services are better equipped to meet the needs of all women.

In the field of Education, Guo (Citation2010) puts forward super-diversity to criticize existing approaches to lifelong learning.

However, perhaps no other field or discipline has employed super-diversity for methodological reassessment more than Socio-linguistics. This is illustrated by Kell (Citation2013, 8) who writes that,

Superdiversity, thus, seems to add layer upon layer of complexity to sociolinguistic issues. Not much of what we were accustomed to methodologically and theoretically seems to fit the dense and highly unstable forms of hybridity and multimodality we encounter in fieldwork data nowadays. Patching up will not solve the problem; fundamental rethinking is required.

Creese and Blackledge (Citation2010, 550) also recognize the new configurations of super-diversity and call “to shift the gaze to the linguistic, focusing on the ways in which the new diversity becomes the site of negotiations over linguistic resources”. They elaborate:

The ways in which people negotiate access to resources in increasingly diverse societies are changing in response to other developments, and we argue that the new diversity is not limited to “new” migrants who arrived in the last decade, but includes changing practices and norms in established migrant (and non-migrant) groups, as daughters and sons, grand-daughters and grand-sons, great-grand-daughters and great-grandsons of immigrants (and non-migrants) negotiate their place in their changing world. … [W]e propose that looking at these phenomena through a sociolinguistic lens is key to a developed understanding of superdiverse societies. (Ibid.)

must set off from super-diversity’s transgressive moment, which consists of discarding the false certainties of multiculturalism and its endorsement of established differences and hierarchies. … The second step consists in CSD embracing the radical unpredictability that comes with the melt-down of the diversity measurement system which super-diversity has provoked.

More ethnicity

(4) In a much more limited and, at times, unimaginative way, many writers invoke “super-diversity” merely to mean more ethnicity – meaning that new migration processes have brought more ethnic groups to a nation or city than in the past. This is certainly not the intention of the super-diversity concept, but it is prevalent among scholars who draw upon super-diversity to call attention to: global movements of people (Roberts Citation2010), ever wider range of new migrant groups (Nathan and Lee Citation2013), people from more countries (Syrett and Lyons Citation2007), migration from more remote corners of the world (Drinkwater Citation2010), new diversity of migrant origins (Antonsich Citation2012), growth in the percentage of population born abroad (Hollingworth and Williams Citation2010), or the plurality of minorities (Hill Citation2007). Most of these studies do not take into account the multidimensional nature of categories, shifting configurations and new social structures that these entail. Hence, the “more ethnicities” understanding of super-diversity is highly misapplied.

Multidimensional reconfiguration

(5) The previous type of usage in the literature surveyed is countered by articles that are truer to the original meaning of the concept. These are works elaborating descriptions and analyses of a multi-dimensional reconfiguration of various social forms. One such piece is by Dahinden (Citation2009) concerning the emergence of super-diversity, coupled with heightened transnationalism, as it fundamentally affects social networks and cognitive classifications among migrants. Other publications note how new super-diverse configurations raise the need to take multiple variables into account when trying to measure diversity (Longhi Citation2013), or call attention to how a combination of variables and attributes are variously combined and used by migrants as different forms of capital (Vershinina, Barrett, and Meyer Citation2009), or recognize how a confluence of factors shape the life chances of ethnic minorities (Stubbs Citation2008), or bring a critique of the ways older categories may be getting in the way of understanding minority communities’ achievements as well as needs (Hollingworth and Mansaray Citation2012) and may affect strategies for recruitment in social and advocacy services (Richardson and Fulton Citation2010). In these important contributions, the call for a super-diverse approach has been productively taken up.

Beyond a focus on ethnicity

(6) Yet other scholars have drawn upon the multidimensionality of super-diversity to augment their desire to move beyond a focus on ethnicity as the sole or optimal category of analysis surrounding migrants. In this way, social scientists have used the concept to emphasize that: ethnic groups are not the optimal units of analysis (Cooney Citation2009) and may actually mask more significant forms of differentiation (Fomina Citation2006); ethnic boundaries are increasingly blurred (Lobo Citation2010; Pecoud Citation2010); there are internal divisions within ethnic groups (Glick Schiller and Çağlar Citation2009); other “strands of identity” that people experience are equally or more important than their identity (Schmidt Citation2012); ethnicity must be cross-tabulated with other categories to get truer picture of contemporary diversity (Aspinall Citation2011); multiple “modes of differentiation” come into play from context to context (van Ewijk Citation2011); and ethnicity-only approaches in social policy are inadequate for addressing needs (Bauböck Citation2008; Crawley Citation2010). Overall, super-diversity has been used to emphasize the inherent complications of classifying people (Aspinall Citation2009; Song Citation2009; Wimmer Citation2009).

New or other complexities

(7) Finally, there are numerous academics who, although invoking the concept of super-diversity, actually draw attention to something rather different (though often not wholly unrelated) to what was originally intended: new or other complexities. Within this type, scholars have referred to super-diversity with regard to at least three fields of new or other complexity. (a) One concerns globalization and migration, in which writers discuss issues like “the complexity of new migration and non-linear trajectories of migrants” (McCabe, Phillimore, and Mayblin Citation2010, 19), how “migrants have become more transitory and more diverse not only in terms of their origins, but also in their motives, intentions and statuses within destination countries” (McDowell Citation2013, 19), how “International migration has become ‘liquid’” (Engbersen, Snel, and de Boom Citation2010, 117) and even how, relatedly, “there are now many sources for ideas and commodities, not simply from Europe or the US or from East to west” (Nolan, MacRaild, and Kirk Citation2010, 11).

(b) Another field of complexity concerns ethnic categories and social identities. Here, super-diversity has prompted renewed interest in: “the origins of people, their presumed motives for migration, their ‘career’ as migrants (sedentary versus short-term and transitory), or their sociocultural and linguistic features [that] cannot be presupposed” (Jacquemet Citation2011, 494); “individuals and groups who themselves are superdiverse … across a wide range of variables” (Leppänen and Häkkinen Citation2012, 18); “socially and culturally complex individuals who cannot be pigeonholed in particular ways and are not necessarily segregated into closed-off communities” (Ros i Solé Citation2013, 327); “a new, ‘super-diverse’ terrain in which ‘old’ structural indicators are less salient to social identities” (Francis, Burke, and Read Citation2014, 2); the “blurring of distinctions” (Newton and Kusmierczyk Citation2011, 76) or the situation in which “clear-cut categories of difference (race, ethnicity, culture, religion) are no more: notions of Whiteness and Blackness, and minority categories as constructed in the postcolonial context and in the premises of multiculturalism, are blurred” (Hatziprokopiou Citation2009, 24); “encounters which undermine held stereotypes” (Osipovič Citation2010, 171); the ways “cultural traditions become manifold or hazy” (Koch Citation2009); how “it is descriptively inadequate to assume fixed relations between ethnicity, citizenship, residence, origin, language, profession, etc. or to assume the countability of cultures, languages, or identities” (Juffermans Citation2012, 33); the “complexity of multiple, fluid, intersectional identifications” (Dhoest, Nikunen, and Cola Citation2013, 13) and, consequently, how “‘super-diversity’ requires an analysis of racism not in a dichotomous or top-down frame but as differentially positioning and constituting different groups and individuals” (Erel Citation2011, 705).

(c) A final mode of complexity seen to be stemming from the concept of super-diversity concerns new social formations. Here, a variety of articles address issues such as: “new hierarchies and power relations within the migrant group” (Erel Citation2009, 10); “trends [that] have diversified the varied forms of contestation of belonging, including new dynamics of spatial segregation and cross-cultural contacts” (Matejskova Citation2013, 46); “complex new ‘meaningful exchanges’” (Butcher Citation2010, 510) that can lead to “greater interaction, to the evolution of culture, and to the development of convivial and cosmopolitan identities” (Taylor-Gooby and Waite Citation2014, 272); how “daily life worlds are increasingly diverse, a process which affects both native and migrant populations … . Institutional monoculturalism and life world super-diversity thus end up coexisting” (Dietz Citation2013, 27); the ways “superdiversity, and its superimposition of diverse networks, brings groups together with very different frames of reference” (Bailey Citation2013, 203); and,

phenomena of globally expanded mobility, which entail new and increasingly complex social formations and networking practices beyond traditional affiliations. Although one could formerly assume the existence over a longer span of time of relatively stable communities of practice, these have become more temporary given the conditions of super-diversity. (Busch Citation2012, 505)

The breakdown of these 325 articles into 7 usages of super-diversity by discipline or multidisciplinary field is represented in . It is immediately interesting to see that no discipline or field is wholly associated with a particular usage. The spread of meanings, uses and understandings of super-diversity is now likely even broader, since at the time of writing this essay, Google Scholar indicates that the original ERS article of 2007 has been cited 2,731 times, while the 2006 COMPAS Working Paper on super-diversity, on which the 2007 article is based, has been cited over 500 times. Overall, I present this typology not just as an exercise in tracing how the concept of super-diversity has travelled and transformed, but to curb or show the futility of some writers’ attempts to simplify super-diversity and its meaning (for instance, as the new, happy normal) “in the literature”.

Super-diversity, the USA and Europe

The editors of this special issue have asked why super-diversity seems to have had more uptake among European than American scholars. As pointed out earlier in the limited review of works citing super-diversity, the concept has been applied by scholars worldwide to numerous contexts and scales, including the USA. But indeed, there appears to have been less usage among American social scientists about American contexts. What might be some reasons for this?

I do not agree that American scholars have used other terms to do the “work” done by the super-diversity concept and approach. They editors suggest that the concept and approach of intersectionality is already existing and in wide use in the USA – but that is the situation in Europe as well. Intersectionality and super-diversity are not really addressing the same thing. Rarely in the USA or Europe has intersectionality referred to migration patterns and outcomes. As mentioned above, super-diversity was coined as a concept to single out and tie together certain migration data patterns. I further suggested that understanding the patterns of super-diversity calls for an approach to research that could simultaneous take into account the compound effects of multiple variables or characteristics. This is of course the inherent approach signalled by the concept of intersectionality. But since (at the time I wrote the original article, at least) intersectionality literature was concentrated on the race–gender-class complex, I called for something focused exclusively on migration-related categories. However, the concepts of intersectionality and super-diversity indeed share a call for recognizing the composite effects of social categories.

The study of urban ethnic politics, which has quite a legacy in the USA, is also not an appropriate substitute for super-diversity’s subject matter. The study of ethnic politics favours large, organized groups with outspoken representatives; it often largely overlooks new and small migrant populations with precarious, temporary and changing legal statuses. Further, there has been far less attention in the USA to the intersection of nationalities and legal statuses, for instance (important exceptions include Massey and Bartley Citation2005; there are, of course, important works dealing with undocumented migrants’ status – such as Menjívar and Abrego Citation2012 – but this is represents only a part of what super-diversity is intended to address). Perhaps less interest in the USA arises because there are far few legal statuses and conditions in the USA as compared with European and other countries (see Beine et al. Citation2016). But this is not a terribly satisfying reason.

The editors importantly underline a key factor possibly explaining less attention to the concept of super-diversity in the USA, namely a preponderance of methodological group-ism, crucially shaped by specific categories of race (cf. Wimmer Citation2015). A great deal of diversity discussions of any kind are framed by specific terms of race, but a great deal of American social scientific analysis, particularly involving statistics, depends on core, official ethnoracial classifications (as does much public discourse). Josh DeWind of the American Social Science Research Council (SSRC) explains,

An issue that has plagued immigration studies, is that most of the social identity categories that are used analytically, are also categories that are used or have their origin in usage by states to manage populations. Many studies are limited to such categories of state censuses, for example, to define racial and ethnic groups that often use more nuanced, overlapping, and contextually distinct categories. Academics then have used state categories to frame studies of immigrant group incorporation and mobility, even if members of the groups define themselves as distinct on the basis of language, religion, class or the like. Measuring the “mobility” of Latinos, for example, compared to that of “Asians” is for many members of those groups meaningless, as these categories obscure significant differences between rich and poor, and educated and uneducated members of the groups … . What is good for administration may not be good for explanation.

So if studies of “diversity” begin with given categories, rather than utilizing categories that are directly appropriate to the analysis, then the categories end up being more of a problem than being useful or they get in the way of understanding. (in Vertovec Citation2015, 5)

The dilemma described by DeWind is by no means wholly representative of American scholarship, but it is likely one fact hampering more complex descriptions and multidimensional analyses of migration-driven diversification. Relatedly, although concerns with racism remain high, many European studies of migrants and ethnic minorities – also reflecting respective country-based official statistics – have engaged less with racial categories than with ones of nationality.

Questions of American vs. European approaches still do not address a basic question: in recent times wherever based, why has there been so much assorted attention, and such varied readings and uses, of super-diversity? For my part, I believe that social scientists are avidly seeking ways of describing and talking about increasing and intensifying complexities in social dynamics and configurations at neighbourhood, city, national and global levels. Sometimes these are addressed in light of changing migration patterns, but as we have seen, now super-diversity is being invoked with reference to other complex social developments. As academics, we are still struggling to describe new, ever more complicated trends, processes and outcomes. Addressing “the superdiversity of cities and societies of the 21st century”, the late Beck (Citation2011, 53) suggested that the rise of such dynamics are “both inevitable (because of global flows of migration, flows of information, capital, risks, etc.) and politically challenging”. However, he said,

It is in this sense that over the last decades the cultural, social and political landscapes of diversity are changing radically, but we still use old maps to orientate ourselves. In other words, my main thesis is: we do not even have the language through which contemporary superdiversity in the world can be described, conceptualized, understood, explained and researched. [Ibid., italics in original]

Through such attempts at describing and analysing new complexities, we are ever better at developing what Nando Sigona has called “ways of looking at a society getting increasingly complex, composite, layered and unequal” (www.nandosigona.worldpress.com). I believe that this is best done when scholars talk about, not just around, concepts like super-diversity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Antonsich, M. 2012. “Exploring the Demands of Assimilation Among White Ethnic Majorities in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (1): 59–76. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2012.640015

- Arnaut, K. 2012. “Super-diversity: Elements of an Emerging Perspective.” New Diversities 14 (2): 1–16.

- Aspinall, P. J. 2009. “The Future of Ethnicity Classifications.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (9): 1417–1435. doi: 10.1080/13691830903125901

- Aspinall, P. J. 2011. “The Utility and Validity for Public Health of Ethnicity Categorization in the 1991, 2001 and 2011 British Censuses.” Public Health 125 (10): 680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.05.001

- Aspinall, P. J., and M. Song. 2013. “Is Race a ‘Salient … ’ or ‘Dominant Identity’ in the Early 21st Century: The Evidence of UK Survey Data on Respondents’ Sense of Who They Are.” Social Science Research 42 (2): 547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.10.007

- Bailey, A. J. 2013. “Migration, Recession and an Emerging Transnational Biopolitics Across Europe.” Geoforum 44: 202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.09.006

- Bauböck, R. 2008. “Beyond Culturalism and Statism. Liberal Responses to Diversity, Eurosphere.” Online Working Paper No. 6: 1–34.

- Baycan, T., and P. Nijkamp. 2012. “A Socio-economic Impact Analysis of Urban Cultural Diversity: Pathways and Horizons.” In Migration Impact Assessment. New Horizons, edited by P. Nijkamp, J. Poot, and M. Sahin, 175–202. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Beck, Ulrich. 2011. “Multiculturalism or Cosmopolitanism: How Can We Describe and Understand the Diversity of the World?” Social Sciences in China 32 (4): 52–58. doi: 10.1080/02529203.2011.625169

- Beine, M., A. Boucher, B. Burgoon, M. Crock, J. Gest, M. Hiscox, P. McGovern, H. Rapoport, J. Schaper, and E. Thielemann. 2016. “Comparing Immigration Policies: An Overview from the IMPALA Database.” International Migration Review 50 (4): 827–863. doi: 10.1111/imre.12169

- Blommaert, J. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Burdsey, D. 2013. “‘The Foreignness Is Still Quite Visible in this Town’: Multiculture, Marginality and Prejudice at the English Seaside.” Patterns of Prejudice 47 (2): 95–116. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2013.773134

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–505. doi: 10.1093/applin/ams056

- Butcher, M. 2010. “Navigating ‘New’ Delhi: Moving Between Difference and Belonging in a Globalising City.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 31 (5): 507–524. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2010.513084

- Catney, G., N. Finney, and L. Twigg 2011. “Diversity and the Complexities of Ethnic Integration in the UK: Guest Editors’ Introduction.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 32 (2): 107–114. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2011.547171

- Colic-Peisker, V., and K. Farquharson. 2011. “Introduction: A New Era in Australian Multiculturalism? The Need for Critical Interrogation.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 32 (6): 579–586. doi: 10.1080/07256868.2011.618104

- Cooney, M. 2009. “Ethnic Conflict Without Ethnic Groups: A Study in Pure Sociology.” British Journal of Sociology 60 (3): 473–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01252.x

- Crawley, H. 2010. “Moving Beyond Ethnicity: The Socio-Economic Status and Living Conditions of Immigrant Children in the UK.” Child Indicators Research 3 (4): 547–570. doi: 10.1007/s12187-010-9071-5

- Creese, A., and A. Blackledge. 2010. “Towards a Sociolinguistics of Superdiversity.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 13 (4): 549–572. doi: 10.1007/s11618-010-0159-y

- Dahinden, J. 2009. “Are We All Transnationals Now? Network Transnationalism and Transnational Subjectivity: The Differing Impacts of Globalization on the Inhabitants of a Small Swiss City.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (8): 1365–1386. doi: 10.1080/01419870802506534

- Dhoest, A., K. Nikunen, and M. Cola 2013. “Exploring Media Use Among Migrant Families in Europe.” Observatorio. doi:10.7458/obs002013663.

- Dietz, G. 2013. “A Doubly Reflexive Ethnographic Methodology for the Study of Religious Diversity in Education.” British Journal of Religious Education 35 (1): 20–35. doi: 10.1080/01416200.2011.614752

- Drinkwater, S. 2010. “Immigration and the Economy.” National Institute Economic Review 213 (1): R1–R4. doi: 10.1177/0027950110380319

- Engbersen, G., E. Snel, and J. de Boom. 2010. “‘A Van Full of Poles’: Liquid Migration from Central and Eastern Europe.” In A Continent Moving West? EU Enlargement and Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe, edited by R. Black, G. Engbersen, M. Okólski, and C. Pantîru, 115–140. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Erel, U. 2009. Migrant Women Transforming Citizenship: Life Stories from Britain and Germany. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Erel, U. 2011. “Reframing Migrant Mothers as Citizens.” Citizenship Studies 15 (6–7): 695–709. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2011.600076

- Fomina, J. 2006. “The Failure of British Multiculturalism: Lessons for Europe.” Polish Sociological Review 4 (156): 409–424.

- Francis, B., P. Burke, and B. Read. 2014. “The Submergence and Re-emergence of Gender in Undergraduate Accounts of University Experience.” Gender and Education 26 (1): 1–17. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2013.860433

- Glick Schiller, N., and A. Çağlar. 2009. “Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 177–202. doi: 10.1080/13691830802586179

- Guo, S. 2010. “Migration and Communities: Challenges and Opportunities for Lifelong Learning.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 29 (4): 437–447. doi: 10.1080/02601370.2010.488806

- Hatziprokopiou, P. 2009. “Strangers as Neighbors in the Cosmopolis: New Migrants in London, Diversity, and Place.” In Branding Cities. Cosmopolitanism, Parochialism and Social Change, edited by S. Donald, E. Kofman, and C. Kevin, 14–27. New York: Routledge.

- Hawkey, K. 2012. “History and Super Diversity.” Education Sciences 2 (4): 165–179. doi: 10.3390/educsci2040165

- Hill, A. 2007. “The Changing Face of British Cities by 2020.” The Observer, December 23.

- Hollingworth, S., and A. Mansaray. 2012. Language Diversity and Attainment in English Schools: A Scoping Study. London: The Institute for Policy Studies in Education (IPSE), London Metropolitan University.

- Hollingworth, S., and K. Williams. 2010. “Multicultural Mixing or Middle-class Reproduction? The White Middle Classes in London Comprehensive Schools.” Space and Polity 14 (1): 47–64. doi: 10.1080/13562571003737767

- Hüwelmeier, G. 2011. “Socialist Cosmopolitanism Meets Global Pentecostalism: Charismatic Christianity Among Vietnamese Migrants After the Fall of the Berlin Wall.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (3): 436–453. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.535547

- Jacquemet, M. 2011. “Crosstalk 2.0: Asylum and Communicative Breakdowns.” Text & Talk 31 (4): 147. doi: 10.1515/text.2011.023

- Jørgensen, J. N. 2012. “Ideologies and Norms in Language and Education Policies in Europe and Their Relationship with Everyday Language Behaviours.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 25 (1): 57–71. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2011.653058

- Juffermans, K. 2012. “Exaggerating Difference: Representations of the Third World Other in PI Aid.” Intercultural Pragmatics 9 (1): 23–45. doi: 10.1515/ip-2012-0002

- Kandylis, G., T. Maloutas, and J. Sayas. 2012. “Immigration, Inequality and Diversity: Socio-ethnic Hierarchy and Spatial Organization in Athens, Greece.” European Urban and Regional Studies 19 (3): 267–286. doi: 10.1177/0969776412441109

- Kell, C. 2013. “Ariadne’s Thread: Literacy, Scale and Meaning Making Across Space and Time.” London: Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies 118, Kings College London.

- Koch, G. 2009. “Intercultural Communication and Competence Research Through the Lens of an Anthropology of Knowledge.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 10 (1), Art. 15.

- Leone, M. 2012. “Hearing and Belonging: On Sounds, Faiths, and Laws.” In Transparency, Power and Control: Perspectives on Legal Communication, edited by V. K. Bhatia, C. A. Hafner, L. Miller, and A. Wagner, 183–197. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Leppänen, S., and A. Häkkinen. 2012. “Buffalaxed Superdiversity: Representations of the Other on Youtube.” New Diversities 14 (2): 17–33.

- Lobo, M. 2010. “Interethnic Understanding and Belonging in Suburban Melbourne.” Urban Policy and Research 28 (1): 85–99. doi: 10.1080/08111140903325424

- Longhi, S. 2013. “Impact of Cultural Diversity on Wages, Evidence from Panel Data.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 43 (5): 797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2013.07.004

- Massey, Douglas S., and Katherine Bartley. 2005. “The Changing Legal Status Distribution of Immigrants: A Caution.” International Migration Review 39 (2): 469–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00274.x

- Matejskova, T. 2013. “The Unbearable Closeness of The East: Embodied Micro-economies of Difference, Belonging, and Intersecting Marginalities in Post-socialist Berlin.” Urban Geography 34 (1): 30–35. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2013.778630

- Mavroudi, E. 2010. “Nationalism, the Nation and Migration: Searching for Purity and Diversity.” Space and Polity 14 (3): 219–233. doi: 10.1080/13562576.2010.532951

- McCabe, A., J. Phillimore, and L. Mayblin. 2010. “Below the Radar: Activities and Organisations in the Third Sector: A Summary Review of the Literature.” Third Sector Research Centre Paper 29, University of Birmingham.

- McDowell, Linda. 2013. Working Lives: Gender, Migration and Employment in Britain, 1945–2007. London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Leisy J. Abrego. 2012. “Immigration Law and the Lives of Central American Immigrants.” American Journal of Sociology 117 (5): 1380–1421. doi: 10.1086/663575

- Nathan, M., and N. Lee. 2013. “Cultural Diversity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship: Firm-level Evidence from London.” Economic Geography 89 (4): 367–394. doi: 10.1111/ecge.12016

- Neal, S., K. Bennett, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2013. “Living Multiculture: Understanding the New Spatial and Social Relations of Ethnicity and Multiculture in England.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 31 (2): 308–323. doi: 10.1068/c11263r

- Newall, D., J. Phillimore, and H. Sharpe. 2012. “Migration and Maternity in the Age of Superdiversity.” Practising Midwife 15 (1): 20–23.

- Newton, J., and E. Kusmierczyk. 2011. “Teaching Second Languages for the Workplace.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 31: 74–92. doi: 10.1017/S0267190511000080

- Nolan, M., D. M. MacRaild, and N. Kirk. 2010. “Transnational Labour in the Age of Globalization.” Labour History Review 75 (1): 8–19. doi: 10.1179/096156510X12568148663764

- Osipovič, D. 2010. “Social Citizenship of Polish Migrants in London: Engagement and Non-engagement with the British Welfare State.” Doctoral thesis, University College London.

- Pecoud, A. 2010. “What Is Ethnic in an Ethnic Economy?” International Review of Sociology 20 (1): 59–76. doi: 10.1080/03906700903525677

- Phillimore, J. 2013. “Housing, Home and Neighbourhood Renewal in the Era of Superdiversity: Some Lessons from the West Midlands.” Housing Studies 28 (5): 682–670. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2013.758242

- Richardson, K., and Fulton, R., 2010. “Towards Culturally Competent Advocacy: Meeting the Needs of Diverse Communities.” Better Health Briefing Paper 15. Kidderminster: British Institute of Race Equality in Advocacy Services.

- Roberts, C. 2010. “Language Socialization in the Workplace.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 30: 211–227. doi: 10.1017/S0267190510000127

- Ros i Solé, C. 2013. “Cosmopolitan Speakers and Their Cultural Cartographies.” The Language Learning Journal 41 (3): 326–339. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2013.836349

- Schmidt, G. 2012. “‘Grounded’ Politics: Manifesting Muslim Identity as a Political Factor and Localized Identity in Copenhagen.” Ethnicities 12 (5): 603–622. doi: 10.1177/1468796811432839

- Song, M. 2009. “Is Intermarriage a Good Indicator of Integration?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 331–348. doi: 10.1080/13691830802586476

- Stubbs, S. 2008. “In Place of Drums and Samosas: In a ‘Super Diverse’ Britain, the Key to Social Cohesion is Not a New British ‘Identity’ but Tackling Poverty and Inequality.” The Guardian, May 13.

- Svenberg, K., C. Skott, and M. Lepp. 2011. “Ambiguous Expectations and Reduced Confidence: Experience of Somali Refugees Encountering Swedish Health Care.” Journal of Refugee Studies 24 (4): 690–705. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fer026

- Syrett, S., and M. Lyons. 2007. “Migration, New Arrivals and Local Economies.” Local Economy 22 (4): 325–334. doi: 10.1080/02690940701736710

- Taylor-Gooby, P., and E. Waite. 2014. “Toward a More Pragmatic Multiculturalism? How the UK Policy Community Sees the Future of Ethnic Diversity Policies.” Governance 27 (2): 267–289. doi: 10.1111/gove.12030

- van Ewijk, A. R. 2011. “Diversity Within Police Forces in Europe: A Case for the Comprehensive View.” Policing 6 (1): 76–92. doi: 10.1093/police/par048

- Vershinina, N., R. Barrett, and M. Meyer. 2009. “Polish Immigrants in Leicester: Forms of Capital Underpinning Entrepreneurial Activity.” Leicester Business School Occasional Papers 86.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. “Super-Diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054. doi: 10.1080/01419870701599465

- Vertovec, Steven. 2015. “Introduction: Formulating Diversity Studies.” In Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies, edited by Steven Vertovec, 1–20. London: Routledge.

- Wessendorf, Susanne. 2014. Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-diverse Context. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2009. “Herder’s Heritage and the Boundary-making Approach: Studying Ethnicity in Immigrant Societies.” Sociological Theory 27 (3): 244–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01347.x

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2015. “Race-centrism: A Critique and a Research Agenda.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (13): 2186–2205. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1058510

- Yildiz, C., and A. Bartlett. 2011. “Language, Foreign Nationality and Ethnicity in an English Prison: Implications for the Quality of Health and Social Research.” Journal of Medical Ethics 37 (10): 637–640. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.040931