?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article analyses how the classroom context contributes to attitude change in adolescence. By analysing the relationship that the primary school classroom context has on anti-immigrant attitudes over time, it addresses the single factor fallacy that has troubled previous research on classrooms, which has largely tested the contact hypothesis. The dataset includes 849 participants over five-time points from 2010 to 2015. Findings show that over time individual’s anti-immigrant attitudes increased in classrooms with a higher average level of anti-immigrant sentiment net of the effect of classroom heterogeneity. However, this finding was true only while students were still enrolled in the same class over the first three waves of the study. After students entered high school, the classroom/time interaction effect disappears, suggesting that other contextual influences take over. This article highlights the crucial importance of classroom context on attitude development in adolescence.

Introduction

In 1970, a documentary film called “Eye of the Storm” (Elliott Citation1970) drew attention to a controversial exercise where an elementary school teacher, Jane Elliott, separated her pupils into two groups based on their eye colour and then ascribed negative traits to one of the groups, proclaiming that one is inherently better than the other. As the day went on the students quickly adopted these roles, reinforced them upon each other, and conflicts quickly erupted over the newly introduced inequities. The following day in the same class, Elliott reversed the roles and the once privileged students were ascribed the negative stereotypes and the results were similar; the children adopted the new roles and the same prejudicial dynamic manifested. This exercise intended to invoke empathy in the students and instruct them about how it feels to be the victim of prejudicial attitudes in the hopes of reducing the real-world prejudices the children harboured toward others (Stewart Citation2003). However, the film laid bare how the dynamics between children were acted out, how they quickly adapted to and reinforced each other’s newfound prejudices, and how their effects were internalized. As Phillip Jackson (Citation1990) notes, the classroom is a unique socializing agent. In no other situation are people required to spend so much time in direct contact with other individuals, both friend and foe, at such an important moment of development. Elliott’s exercise shows, how classroom context may have powerful effects on young people, especially in how students adapt to the attitudinal environment around them. This begs the question: Do classrooms shape prejudicial attitudes?

Answering these questions will provide insight into an important research area in sociology, how different social contexts shape attitudes. As noted, individuals spend a large amount of time immersed in the classroom context; therefore, longitudinal analysis during the attitudinal formation period of adolescence is key. This study analyses longitudinal data over five survey waves of respondents that range from 13 to 17 years of age, to assess how the attitudinal environment influences adolescents’ attitudes over time.

Classrooms as a contextual socialization factor

Research on prejudice has been primarily focused on adults and has shown that prejudicial attitudes are highly dependent on contexts (Bennett and Sani Citation2008). Many of the social contextual factors that are used as predictors for prejudicial attitudes have been found in the comparative research where context is operationalized at the country level. In terms of anti-immigrant sentiments, the country level factors have varied but have included predictors such as religiosity (Bohman and Hjerm Citation2013; Koopmans Citation2015), education (Hjerm Citation2001), economic condition (Hatton Citation2017) and proportion of immigrants (Hjerm Citation2007). The country level ideological environment has also been shown to have a negative influence on attitudes towards immigrants in countries where attitudes that support right-wing authoritarianism are more common (Cohrs and Stelzl Citation2010). Drilling down to smaller contextual units, there is growing attention being paid to regional and local level contexts in Europe (Markaki and Longhi Citation2013) and at the county level in the United States (Goldman and Hopkins Citation2016).

These studies have illuminated the importance that different contexts can have in predicting prejudicial attitudes in adults. However, research has shown that these attitudes form during childhood and adolescence (Raabe and Beelmann Citation2011) and that once prejudicial attitudes are formed, they only become more stable and crystalized throughout the life course (Henry and Sears Citation2009; Sears and Funk Citation1999; Rekker et al. Citation2015). Additionally, it appears that the time when individuals are susceptible to attitudinal change precipitously drops after adolescence and in young adulthood (Krosnick and Alwin Citation1989). Which leads to the assumption that if we are to understand how social contexts effect prejudicial attitudes, we must study their effects during adolescence. Taking in to account the research on how important the timing is on attitudinal formation and change, it is interesting that the research into the contextual effects on prejudice in adolescence has been quite scarce (but see Bubritzki et al. Citation2017; Hjerm Citation2005; Miklikowska Citation2016, Citation2017; Van Zalk et al. Citation2013).

Of all the social contexts that adolescents are exposed, schools and specifically classrooms must certainly be considered. Classrooms as a context can be thought of in many ways, but for the purposes of this study, the classroom is a socializing agent where the aggregated attitudes of the individual’s peers are posited to influence their own. This approach is supported in research on classroom effect generally, showing that the attitudinal environment can influence things such as bullying (Sentse et al. Citation2015), aggression, focus and pro-social behaviour (Barth et al. Citation2004; Chang Citation2017). Furthermore, school and classroom climate context can influence interest in civic and political engagement (Lenzi et al. Citation2014; Campbell Citation2008), and the classroom peer effect has also been shown to influence learning outcomes (Burke and Sass Citation2013). This comes as little surprise since classrooms are nearly universal aspect of adolescents’ lives and so much time is spent there.

Since the 1970s, much of what we understand about how adolescents adopt the attitudes of others has been shaped by social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979), which suggests that individuals strive to maintain a positive social identity and that this identity on based on favourable comparisons between the individual’s in-group and some out-group. In the interest of maintaining high self-esteem, individuals seek to identify with their chosen in-group and assign a value to that identity, thus prejudices develop through creating positive associations to in-group traits and negative associations to out-group traits as a means of justifying the perceived group membership. Naturally, peer groups defined as small groups of friends, have attracted considerable attention as researchers have attempted to parse out the mechanisms by which attitude adoption takes place, arguing that an individual’s peers serve as the reference group around which in-group preferences are constructed (Brown Citation1990; Brown et al. Citation2008). However, as Hornsey notes in a review of the social identity approach (Citation2008), people do not blindly express in-group favouritism regardless of context. Instead, social context influences how the individual interacts with their peer groups and contributes to the adoption of attitudes. Furthermore, classrooms are environments of involuntary peer groups, where individuals must interact with both with their friends and their foes facing exposure to attitudes typically not captured in studies on small peer groups due to selection effect. Therefore, classroom context as defined by the attitudinal environment are related to, and yet still distinct from, peer groups as defined in previous attitude research. As Brown notes, “Researchers should remain mindful of how major contexts in adolescent lives such as classrooms, work, family and other larger social institutions shape peer group relations” (182, Citation1990).

This is not to say that the research on prejudicial attitude development has overlooked classroom context. Rather, the context has been defined differently. When classrooms are researched, it is typically in the interest of testing the effect that classroom heterogeneity has on inter-group biases through the contact hypothesis. This suggests individuals are likely to be less prejudiced toward out-group members, under certain conditions, the more they have contact with them (Allport Citation1954). Studies support the assertion of inter-group contact theory across multiple contexts and in meta-analyses (Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006; Van Laar et al. Citation2005; Bubritzki et al. Citation2017; Janmaat Citation2014; Munniksma et al. Citation2017; Titzmann, Brenick, and Silbereisen Citation2015). While these studies have provided valuable insight into this type of classroom context in relation to prejudice, they suggest that the classroom influence is merely a meeting place where the in-group biases are mitigated through inter-group contact.

However, recently Pettigrew and Hewstone have referred to complications presented in this research as the “single factor fallacy” (Citation2017), where studies focus exclusively on one factor (inter-group contact for example) and omit other, potentially significant factors that help to explain changes in prejudicial attitudes. They recommend incorporating other potential confounders at different analytic levels to account for structural influences such as classrooms. They also highlight the need for longitudinal analysis to understand the changes that happen in attitudes as the only way to account for overtime factors that have plagued previous work. There are two notable exceptions to this line of research, first as Poteat's (Citation2007) longitudinal study on homophobic attitudes showed, the attitudinal environment of the classroom can impact attitudes toward out-group members, and second Thijs and Verkuyten’s (Citation2013) study on multicultural attitudes, though neither of which control for inter-group contact.

Looking toward the attitudinal environment of the classroom there is encouraging evidence in the experimental literature. For example, the social tuning hypothesis suggests that people generally wish to get along with one another, and therefore modify their beliefs and behaviours to others around them, tuning in with one another as they spend time together (Jost, Ledgerwood, and Hardin Citation2008). Testing the social tuning hypothesis there is evidence that this applies to implicit prejudices, and that interpersonal interactions with in-group as well as out-group members can shape respondent’s biases (Sinclair et al. Citation2005a; Sinclair et al. Citation2005b; Sinclair, Kenrick, and Jacoby-Senghor Citation2014). Additionally, Huntsinger et al. (Citation2016) find that this social tuning is a function of changing associations, suggesting that this effect is subject to contextual change. While these experimental findings provide insight, their focus has been on parsing out how social tuning functions between individuals in different circumstances. However, social context provides the frame of reference by which individuals’ attitudes are compared (Abrams and Hogg Citation1990), and so the attitudinal context of classroom peers may serve as the reference by which the individuals tune their own attitudes.

It is with this in mind that the present study incorporates classroom level attitudinal environment as a socializing agent into the analysis of anti-immigrant attitudes in adolescence over time. Therefore, the following hypotheses have been developed:

H1: Adolescents’ prejudice level will be effected by the degree of prejudice in their classroom.

More specifically, over time the anti-immigrant attitudes of the individual will move closer to the average anti-immigrant attitudes of their classroom.

H2: Effect of the classroom prejudice will persist net of the level of classroom heterogeneity.

Time matters

Adding upon the importance of classroom context, understanding when contextual factors are most important in influencing attitudes is another area that has been left largely unexplored. When, for example, does class context matter most? Or, does the influence you receive during years of intense classroom involvement (being in the same classroom with many of the same individuals over time for example) have a lasting effect on your attitudes even after you matriculate? The current research largely treats the effects of context on attitude development as if it is consistent over time, when it is possible that they are also dynamically changing, having different effects sizes at different times, or disappearing entirely as real-world conditions change. Historically, value-added models analysing longitudinal data have addressed this issue to study academic achievement in relation to classroom context and teacher performance on students (Doran and Lockwood Citation2006; McCaffrey et al. Citation2004), however, this method has not yet been applied to attitude development. As previous research has noted, there is an age effect on prejudice, but the ages that apply to this dataset (∼13–17 years) have been found to be a stabilizing time for adolescent’s attitudes (Raabe and Beelmann Citation2011). It is suggested that this is due to the increased importance of micro contextual influences in this age group (Rutland, Killen, and Abrams Citation2010). This makes the longitudinal nature of this study all the more appealing. Given its potential to analyse the micro contextual influence on anti-immigrant attitudes at different time points the following hypothesis has been developed:

H3: Once students matriculate into high school, their primary school classroom prejudice will no longer influence them.

The present study

Participants and measurement

Participants in this study consist of adolescents from the Youth and Society dataset compiled by Örebro University in Sweden from 2010 to 2015. The sample is from a typical city in Sweden, which resembles the national average on a number of metrics in including income, population density and employment rate, making this subsample generalizable to the population (Amnå et al. Citation2010).

This study analyses repeated measures of students from five waves, when they are in seventh, eighth and ninth grades, and following them into high school for two waves. The average age of students at time point one of 13.41 years old (SD = .525). There are a total of 849 participants in this study in 40 classrooms averaging 24 students per class (SD= 4.31). Classrooms differed with respect to ethnic composition but students predominantly identified as Swedish or Nordic marking their parents as being born within one of the Nordic countries 73.4 per cent (Sweden, Norway, Finland or Denmark) versus non-Nordic 26.6 per cent. There were 23 missing responses to the dependent variable for the initial response rate (T0 n = 826). Wave two the saw an attrition rate of 25.5 per cent (T1 n = 698), attrition between wave two and wave three was negligible at .4 per cent (T2 n = 695), attrition between wave three and four was 21.6 per cent (T3 n = 615) and finally the attrition rate between wave four and five was 4.6 per cent (T4 n = 593).

Individual anti-immigrant attitudes

Participants were provided a stem question which read: “What is your opinion about people that come here from other countries?” followed by three statements where they could select items on a four-point Likert scale (1 = Does not apply at all, 2 = Does not apply so well, 3 = Applies quite well 4 = Applies very well). The statements were: “It happens only too often that immigrants have customs and traditions that not fit into Swedish society”, “Immigrants often come here just to take advantage of welfare in Sweden” and “Immigrants often take jobs from people who are born in Sweden”. Each item correlated well to each other to at least .47 or higher and in an exploratory factor analysis, the three items loaded on to a single component explaining 68 per cent of the variance in the data. Thus to create the prejudice measurement for individuals, the variables were averaged into one scale for each wave with a sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha T0 = .77). This was true across all other time points as well with Cronbach’s alpha’s (T1= .78, T2 = .77, T3 = .80 T4 = .81).

To ensure that the measurement scale item for the dependent variable was consistent across time points, measurement invariance models were conducted on each of the waves using semTools R package. This allows for measurement invariance testing to provide confidence that the scale is measuring the same construct across the waves, while also accommodating for the autocorrelated nature of the repeated measures (Vandenberg and Lance Citation2000) used in this study. Since this study contains a relatively large sample size, CFI and RMSEA model fit indicators were used to judge measurement invariance. Baseline models show an acceptable CFI level of .968 and CFI difference in the full scalar invariance model is within acceptable parameters (.958) supplemented by similarly small RMSEA measurement difference between models (.046–.048) (Chen Citation2007).Footnote1 This provides confidence that the “prejudice” scale variable for each wave are consistent and allow for the comparison across time points for the interpretation of changes in the respondents’ attitudes over time.

Independent variables

The independent classroom-level prejudice variable was made by averaging the prejudice score of the students in the classroom for each wave. These three waves had a high level of consistency (Cronbach’s alpha= .70) and a low level of inter-item variance (.03), justifying averaging the waves to make a discreet classroom level prejudice scale that is consistent over time. Additionally, this allows for the creation of a “stable group model” where the Level 3 predictor variable varies from classroom to classroom but not from time point to time point (Bauer et al. Citation2013). In this case, the classroom is an ideal contextual measurement because adolescents remain in the same class for the first three waves of the study. This has two advantages, first, it allows for control of selection effect by examining the same classrooms with largely the same individuals in them over three-time points – which is something that has troubled previous research since it controls for both homophily and inter-group contact effects. Second, it allows for analysis of whether the classroom context stops influencing, or continues to influence individuals once they leave in two-time points after primary school.

Included in the analysis are a number of variables to control for possible cofounders. To control for contact hypothesis, classroom heterogeneity on the basis of nationality was created with a dichotomous variable where “1” indicates if the participant has at least one of their parents that were born outside of Sweden or another Nordic country, then an average score was created for each classroom. Also, included in the analysis was gender variable where “1 = girl” and “2 = boy”. To control for socio-economic status (SES), a perceived SES scale variable was created by averaging three SES questions together, each on a five-point Likert scale. The first question asked, “If you want things that cost a lot of money (e.g., a computer, skateboard, cell phone), can your parents afford to buy them if you want them?” (1 = Absolutely not, 5 = Yes, absolutely). Then two other questions where responded were asked to compare their family finances to others in their classroom. Similar to the dependent variable, these three items correlated highly to each other at .45 or higher and in a factor analysis loaded on to one component explaining 66.3 per cent of the variance in the data with a sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .74).

Methods

Longitudinal multilevel analysis with repeated measures using the LME4 package (Bates et al. Citation2015) in the R environment was used for this study and p-values were obtained using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen, Citation2017). The models constructed have a nested three-level structure with: responses at different time points (Level 1), nested within individuals (Level 2), and nested within classrooms (Level 3). Due to this structure, a “model building” approach was taken, where multiple data analysis runs are conducted in a step-wise fashion with growing complexity where first an unconditional model is created and tested against different error structures to obtain good model fit, then the focal predictor is added, followed by the addition of covariates, and finally a full model over the all the waves in the study. Assuming the outcome changes linearly with time (see the unconditional model tests below), this model is written as follows:where j indexes group, i indexes individual and t indexes the observation. The first two terms are the fixed effects, capturing the average change over time. The term

can be interpreted as the expected value of anti-immigrant attitude of individual y at time point one (T0).

is the average rate individual y’s attitude changes over time in the group. The remaining terms in the equation are the random effects. First,

accounts for the stable mean differences in attitudes of individuals across classrooms.

is the random intercept capturing the individual differences at time point 1 (T0), and

captures the random difference in the rate of change in time. Finally,

is the residual that captures the random noise around individuals’ growth trajectories. This unconditional model (Model 1), with a random coefficient growth model with intercepts and slopes at each level of the nesting and the main effect for time only.

Model 2 incorporates the focal predictor, classroom prejudice, into the equation as a discrete scale variable described above, and Model 3 incorporates the control variables classroom heterogeneity, gender and SES. To create a nuanced analysis that tests the time-related hypothesis (H3) separately, Models 1, 2 and 3 are all analysed using just the first three waves of the data, while students are still in primary school and in the same classroom environment at each of the time measurements. After this, students leave their classroom cohorts and enrol into high school, where their peers, teachers, classrooms and schools are all different. Therefore, separate analysis incorporating the waves four and five are conducted in Model 4 to test if the effect of their primary school classroom context had a lasting effect on their anti-immigrant attitudes.

Model fit

Because I have fit a three-level model there are three levels of random effects. In an examination of model fit, it was found that the residual variance in the linear model was not constant over time, an assumption of the first model. The estimated residual variance for each time point diminishes where (T0 = 1.00, T1 = .93, T2 = .76) showing the residual standard deviation at measurement time three is estimated to be 76 per cent as large as that for time measurement 1. This suggests a heteroskedastic nature to the data where overtime where the residual variance is shrinking (Pinheiro and Bates, Citation2000). Since both models were fit using REML differing only in their stochastic portion a likelihood test ratio was used to compare them, ANOVA shows that the log likelihood for the model that allowed for heterogeneous variance was closer to zero (−2240.7 versus −2245.9) at the .005 level, suggesting that it is a much better fit for the data. Quadratic or polynomial models were also tested and ANOVA tests show those changes did not improve the model fit.

Results

Descriptive statistics for students’ anti-immigrant attitudes across each time point are shown in . The average individual anti-immigrant attitude scores for all students in the sample remain relative steady through the first four time points (m range 2.22–2.28) followed by a dip in the final wave (m = 2.14). Girls in the sample score consistently lower on average than do boys across all time points (T0 = −.12, T1 = −.21, T2 = −.31. T3 = −.23, T4 = −.31), and students classified non-Nordic score consistently lower on average than do Nordic students (T0 = −.23, T1 = −.29, T2 = −.29, T3 = −.30, T4 = −.18). Average score for the SES control variable was 3.29 (SD = .70). The classroom level prejudice score, averaged across classrooms was 2.21 (SD = .21). While it may appear that there is small variation across individuals over time, there is sufficient within individual variation to justify analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for anti-immigrant attitudes (n=849).

Additionally, according to Hypothesis 1, over time the anti-immigrant attitudes of the individual will move closer to the average anti-immigrant attitudes of their classroom. If this were the case, then as each student’s attitudes should approach the average attitudinal level of their classroom and the classroom level standard deviation should shrink as the student-to-student variance decreases. This appears to be the case as the average standard deviation for all classrooms shrinks over the three waves (Wave 1 SD = .73, Wave 3 SD = .66). It would also be possible that the within an individual residual variance of the prejudicial indicators would decrease over time, which is also the case across the three waves (Wave 1 = .56, Wave 3 = .51) bolstering the evidence provided in further analysis.

In the analytic results shown in , Model 1 shows the random effects residual is .25 with a standard deviation of .5. The individual level random intercept

is .275, SD = .524 and the classroom level random intercept is

is .028, SD = .167. The intercept in the fixed part of the unconditional model (Model 1) is 2.2 and time is not significantly different from zero, showing that respondents did not show change due strictly to time effect of getting older. This finding is consistent with previous research showing no significant age effect for the 14–16 year old age category (Raabe and Beelmann Citation2011).

Table 2. Multilevel models, dependent variable: anti-immigrant attitudes.

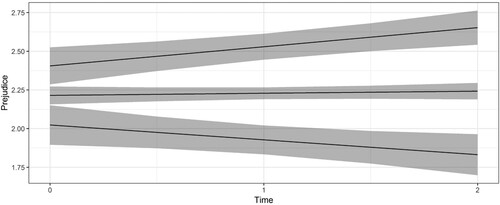

Models 2 confirm Hypothesis 1 showing that when classroom level prejudice is included into the analysis it significantly influences individuals anti-immigrant attitudes. At time point zero, the mean difference between classrooms is .61, (CI = .35–.87). In these models, the interaction between time and classroom level prejudice show that there is a classroom slope difference over time dependent on the level of prejudice in the classroom. (.29, CI= .10–.47). shows the predicted values of the growth curve for this model in high (2.63), medium (2.21) and low (1.80) prejudice classroom contexts. It shows how individuals track towards the means of these classrooms over the three waves that they are exposed to their primary school context. This figure makes clear the three-wave trend towards the means in each of the classroom types.

Figure 1. Predicted values: high, medium and low prejudice classrooms with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Model 3 is the fully constrained model over the first three waves that includes the other covariates. The effect of classroom context still remains significant over time although only at the .05 level (.27, CI = .09–.46), but both gender and classroom heterogeneity have significant effect on prejudice over time where the boys are more prejudiced than the girls (.2) and classrooms with more immigrants result in lower anti-immigrant attitudes (−.24). These sustained effects over time show that the growth curve of classroom effect on anti-immigrant attitudes remains, ruling out the possibility for selection effect. Furthermore, the classroom level contextual effect remains even after controlling for the potential contact hypothesis confounder through classroom heterogeneity. This confirms other research that has analysed the contact hypothesis as it relates to classrooms, but it also confirms Hypothesis 2, that the classroom context still has an effect on individuals’ anti-immigrant attitudes net of the effect resulting from the proportion of non-Nordic students in the classroom.

Model 4 extends the study to include the last two waves in the dataset when students enter high school. It shows that the classroom effect remains significant, but that the interaction between classroom level prejudice and time is gone. This suggests that while there is a measurable growth curve in individual’s anti-immigrant attitudes associated with their classroom context during primary school (shown in Models 2 and 3), this is no longer the case once they enter high school (Model 4). This indicates that the primary school classroom contextual effect is important in shaping adolescents attitudes only while students are in that environment. Once students matriculate into high school, the slope variation is no longer significantly different from zero. Showing that other effects not included in this analysis, or their new high school cohort grouping take over in influencing their attitudes towards immigrants.

This may be for a number of reasons. First, while in primary school the students are in the same classroom, with the same teachers, and the same peers for an extended period of time so their exposure to the group dynamic (whether that be pro-or anti-immigrant) is much higher for longer. They are also in that environment for three years, so there is ample time for their change in attitudes to be measured. Once they enter high school, they split from their primary school group, change teachers and are in multiple different classrooms with a new high school cohort grouping so the nature of classroom context as it is operationalized in this study has changed. It is possible that their new high school cohort grouping assumes this influencing role providing a new group for them to “socially tune” their attitudes, but data about this group was not collected in this dataset. Still, the non-finding of continued influence of the primary school context remains interesting. It provides insight into the mechanism of context, showing that the amount of exposure is important in the ability to effect attitudes but that the results of this effect are not necessarily permanent. If exposed to the right contexts later on in adolescence these effects could be undone. Essentially, the attitudinal environment of their classroom effects students, helping to shape their individual attitudes as they prepare to enter high school. However, once they enter high school they are subject to other contexts that influence their attitudes from that point on.

Conclusions

The results from this study confirm the hypotheses set forth at the beginning of this article. Consistent with the social tuning hypothesis, attitudes of the individuals in the study come into line with those of the group. More specifically, individuals’ anti-immigrant attitudes approach the average attitudinal level of their classrooms over time. This shows that students in classrooms with a high level of anti-immigrant sentiment harbour similar sentiments themselves at the end of the three waves. While the data show that classroom heterogeneity was important, after controlling for this, the effect of the classroom attitudinal environment remained, suggesting that students’ attitudes are adjusting to the group even when there are few, if any, out-group members present. Finally, these results are supported by the fact that this effect disappears in the model after the students are no longer exposed to their primary school classroom environment.

Generally, this study supports the literature showing a general decline in anti-immigrant attitudes over time among adolescents (Raabe and Beelmann Citation2011), and that there is a decline that is attributed to the contact hypothesis. Still, even taking that into account, respondents in high anti-immigrant classroom contexts still exhibit an increase in anti-immigrant attitudes. Additionally, this study offers new information about the potential for decreasing anti-immigrant attitudes, even when increasing populations of out-group members is difficult or impossible since it shows that individuals will respond to an attitudinal environment that is accepting of immigrants, even if there are few or no immigrants present.

While the results of classroom influence were only found while students were enrolled in their primary school classes, the classroom level influence did not continue to have an impact after students left. This is probably due to the amount of time students spend with the same group and teacher during their primary school years, but it may also have to do with a shift in students susceptibility to be influenced by chosen peer groups more commonly associated with social identity theory, instead of the socializing effects of the classroom. It is important to keep in mind that that the primary school classroom effect does not disappear, rather the classroom effect establishes a new baseline level of prejudice in the adolescents in the study when they entered high school. In either case, this finding has interesting implications for potential anti-prejudice intervention programmes.

Several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, the study begins its analysis of students at around 13 years of age. It is known that at this point in the life course, prejudicial and political attitudes are already developing and can be quite nuanced (Bennett and Sani Citation2008). To have a better understanding of the influence that the classroom has on students, data that covers a longer period of time, or ideally the full experience of their primary school education would provide better insight. Another limitation is that this data did not collect information about attitudes of the teachers in the classrooms. Obviously, teachers have a large impact on the environment of the classrooms, which might serve as a mediating effect on the transmission of group attitudes to the individual. As noted in the theoretical section of the paper, peer groups are one of the most important contexts for attitudinal development in adolescence, and this study did not control for friendship influence within classrooms. It is also possible that in rare instances a single individual could influence all of the other students in the classroom, thus reversing the causal direction of the relationship between individuals and their classroom attitudes. Finally, another limitation of the data was that it did not account for the different structure of high school so that it was impossible to analyse the potential effect of the new grouping cohort that the participants entered into at this time.

Still, the findings from this study provide nuance and serve as an example of what many scholars are calling for in new research. It avoids the “single factor fallacy” that has previously existed by including multiple levels of influence and controlling for factors presented by different theoretical perspectives. The primary theme of this paper has been to analyse how the attitudinal environment influences anti-immigrant attitudes, but thanks to the availability of data it was able to control for contact hypothesis and overall effects that time has on attitudinal development as adolescents get older. It shows that exposing adolescents to different attitudinal environments is important as they develop their attitudes in relation to their own social identity, but that the ethnic make-up of the environment also matters. This indicates that these two theoretical perspective are not mutually exclusive, rather that there are two distinct but related types of influence occurring inside classrooms during this crucial time of development. As researchers continue to parse out the mechanisms by which attitudes develop, it is recommended that empirical studies test aspects of different theories together to provide further nuance to our knowledge of attitude development.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Mikael Hjerm and Andrea Bohman for their useful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This invariance test defined the dependent variable as continuous in the semTools, since this is the only available option with that package and it is how the variable is operationalized in this study. A similar analysis defining the variable as ordinal was conducted using Mplus showing poorer model fit. Since the longitudinal analysis reported here fits within the recommended thresholds the author believes that the continuous use of the variable is appropriate for this study.

References

- Abrams, Dominic, and Michael A. Hogg. 1990. “Social Identification, Self-categorization and Social Influence.” European Review of Social Psychology 1 (1): 195–228. doi:10.1080/14792779108401862.

- Allport, G. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Anchor Books.

- Amnå, E., M. Ekström, M. Kerr, and H. Stattin. 2010. Codebook: the Political Socialization Program. Örebro: Youth & Society at Örebro University, Sweden.

- Barth, Joan M., Sarah T. Dunlap, Heather Dane, John E. Lochman, and Karen C. Wells. 2004. “Classroom Environment Influences on Aggression, Peer Relations, and Academic Focus.” Journal of School Psychology 42: 115–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2003.11.004

- Bates, D. M., M. Maechler, B. Bolker, and S. Walker. 2015. “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4.” Journal of Statistical Software 67 (1): 1–48. doi:10.1177/009286150103500418 doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Bauer, Daniel J., Nisha C. Gottfredson, Danielle Dean, and Robert A. Zucker. 2013. “Analyzing Repeated Measures Data on Individuals Nested Within Groups: Accounting for Dynamic Group Effects.” Psychological Methods 18 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1037/a0030639.

- Bennett, Mark, and Fabio Sani. 2008. “Children’s Subjective Identification with Social Groups: A Self-Stereotyping Approach.” Developmental Science 11 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00642.x.

- Bohman, Andrea, and Mikael Hjerm. 2013. “How the Religious Context Affects the Relationship Between Religiosity and Attitudes Towards Immigration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (6) Taylor & Francis: 937–957. doi:10.1080/01419870.2012.748210.

- Brown, B. B. 1990. “Peer Groups and Peer Cultures.” In At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent, edited by S. S. Feldman and G. R. Elliott, 171–196. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brown, B. B., J. P. Bakken, S. W. Ameringer, and S. D. Mahon. 2008. “A Comprehensive Conceptualization of the Peer Influence Process in Adolescence.” In Understanding Peer Influence in Children and Adolescents, edited by M. J. Prinstein and K. Dodge, 17–44. New York: Guilford Press.

- Bubritzki, Swantje, Frank van Tubergen, Jeroen Weesie, and Sanne Smith. 2017. “Ethnic Composition of the School Class and Interethnic Attitudes: A Multi-Group Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–21. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1322501.

- Burke, Mary A, and Tim R Sass. 2013. “Classroom Peer Effects and Student Achievement.” Journal of Labor Economics 31 (1): 51–82. doi:10.1086/666653.

- Campbell, David E. 2008. “Voice in the Classroom: How an Open Classroom Climate Fosters Political Engagement among Adolescents.” Political Behavior 30 (4): 437–454. doi:10.1007/s11109-008-9063-z.

- Chang, Lei. 2017. “The Role of Classroom Norms in Contextualizing the Relations of Children’s Social Behaviors to Peer Acceptance.” Developmental Psychology 40: 691–702. Accessed September 22. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.691.

- Chen, Fang Fang. 2007. “Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (3): 464–504. doi:10.1080/10705510701301834.

- Cohrs, J. Christopher, and Monika Stelzl. 2010. “How Ideological Attitudes Predict Host Society Members’ Attitudes Toward Immigrants: Exploring Cross-National Differences.” Journal of Social Issues 66 (4): 673–694. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01670.x.

- Doran, Harold C, and J. R. Lockwood. 2006. “Fitting Value-Added Models in R.” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 31 (2): 205–230. doi:10.3102/10769986031002205.

- Elliott, Jane. 1970. Eye of the Storm. Directed by William Peters. New York, NY: American Broadcasting Network.

- Goldman, Seth K., and Daniel J. Hopkins. 2016. “Past Threat, Present Prejudice: The Impact of Adolescent Racial Context on White Racial Attitudes.” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id = 2799347.

- Hatton, Timothy J. 2017. “Immigration, Public Opinion and the Recession in Europe”.

- Henry, P. J., and David O. Sears. 2009. “The Crystallization of Contemporary Racial Prejudice Across the Lifespan.” Political Psychology 30 (4): 569–590. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00715.x.

- Hjerm, Mikael. 2001. “Education, Xenophobia and Nationalism: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (1): 37–60. doi:10.1080/13691830124482.

- Hjerm, M. 2005. “What the Future May Bring: Xenophobia among Swedish Adolescents.” Acta Sociologica 48 (4): 292–307. doi: 10.1177/0001699305059943

- Hjerm, Mikael. 2007. “Do Numbers Really Count? Group Threat Theory Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (8): 1253–1275. doi: 10.1080/13691830701614056

- Hornsey, Matthew J. 2008. “Social Identity Theory and Self-categorization Theory: A Historical Review.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2 (1): 204–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x

- Huntsinger, Jeffrey R., Stacey Sinclair, Andreana C. Kenrick, and Cara Ray. 2016. “Affiliative Social Tuning Reduces the Activation of Prejudice.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 19 (2): 217–235. doi:10.1177/1368430215583518.

- Jackson, Philip. 1990. Life in Classrooms. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Janmaat, Jan Germen. 2014. “Do Ethnically Mixed Classrooms Promote Inclusive Attitudes Towards Immigrants Everywhere? A Study among Native Adolescents in 14 Countries.” European Sociological Review 30 (6): 810–822. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu075.

- Jost, John T., Alison Ledgerwood, and Curtis D. Hardin. 2008. “Shared Reality, System Justification, and the Relational Basis of Ideological Beliefs.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2 (1): 171–186. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00056.x.

- Koopmans, Ruud. 2015. “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility Against Out-Groups: A Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (1): 33–57. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.935307

- Krosnick, J. A., and D. F. Alwin. 1989. “Aging and Susceptibility to Attitude-Change.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57 (3): 416–425. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.57.3.416 doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.416

- Kuznetsova, A., P. B. Brockhoff, and R. H. B. Christensen. 2017. “lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 82 (13): 1–26. doi:10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

- Lenzi, Michela, Alessio Vieno, Jill Sharkey, Ashley Mayworm, Luca Scacchi, Massimiliano Pastore, and Massimo Santinello. 2014. “How School Can Teach Civic Engagement Besides Civic Education: The Role of Democratic School Climate.” American Journal of Community Psychology 54 (3–4) Springer US: 251–261. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9669-8.

- Markaki, Yvonni, and Simonetta Longhi. 2017. “What Determines Attitudes to Immigration in European Countries? An Analysis at the Regional Level.” Migration Studies 1: 311–337. Accessed September 8. doi:10.1093/migration/mnt015.

- McCaffrey, D. F., J. R. Lockwood, D. Koretz, T. A. Louis, and L. Hamilton. 2004. “Models for Value-added Modeling of Teacher Effects.” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 29 (1): 67–101. doi:10.3102/10769986029001067.

- Miklikowska, Marta. 2016. “Like Parent, Like Child? Development of Prejudice and Tolerance Towards Immigrants.” British Journal of Psychology 107 (1): 95–116. doi:10.1111/bjop.12124.

- Miklikowska, Marta. 2017. “Development of Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Adolescence: The Role of Parents, Peers, Intergroup Friendships, and Empathy.” British Journal of Psychology, 1–23. doi:10.1111/bjop.12236.

- Munniksma, Anke, Peer Scheepers, Tobias H. Stark, and Jochem Tolsma. 2017. “The Impact of Adolescents’ Classroom and Neighborhood Ethnic Diversity on Same- and Cross-Ethnic Friendships Within Classrooms.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 27 (1): 20–33. doi:10.1111/jora.12248.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Miles Hewstone. 2017. “The Single Factor Fallacy: Implications of Missing Critical Variables From an Analysis of Intergroup Contact Theory1.” Social Issues and Policy Review 11 (1): 8–37. doi:10.1111/sipr.12026.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F, and Linda R Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

- Pinheiro, José C., and Douglas M. Bates. 2000. Mixed-effects Models in S and S-PLUS. New York: Springer.

- Poteat, V. Paul. 2007. “Peer Group Socialization of Homophobic Attitudes and Behavior During Adolescence.” Child Development 78 (6): 1830–1842. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01101.x.

- Raabe, Tobias, and Andreas Beelmann. 2011. “Development of Ethnic, Racial, and National Prejudice in Childhood and Adolescence: A Multinational Meta-Analysis of Age Differences.” Child Development 82 (6): 1715–1737. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01668.x.

- Rekker, Roderik, Loes Keijsers, Susan Branje, and Wim Meeus. 2015. “Political Attitudes in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: Developmental Changes in Mean Level, Polarization, Rank-Order Stability, and Correlates.” Journal of Adolescence 41: 136–147. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.011.

- Rutland, Adam, Melanie Killen, and Dominic Abrams. 2010. “A New Social-Cognitive Developmental Perspective on Prejudice.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 5 (3): 279–291. doi:10.1177/1745691610369468.

- Sears, David O., and Carolyn L. Funk. 1999. “Evidence of the Long-Term Persistence of Adults’ Political Predispositions.” The Journal of Politics 61 (1): 1–28. doi:10.2307/2647773.

- Sentse, Miranda, René Veenstra, Noona Kiuru, and Christina Salmivalli. 2015. “A Longitudinal Multilevel Study of Individual Characteristics and Classroom Norms in Explaining Bullying Behaviors.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 43 (5): 943–955. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9949-7.

- Sinclair, Stacey, Jeffrey Huntsinger, Jeanine Skorinko, and Curtis D Hardin. 2005a. “Social Tuning of the Self: Consequences for the Self-Evaluations of Stereotype Targets.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (2): 160–175. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.160.

- Sinclair, Stacey, Andreana C. Kenrick, and Drew S. Jacoby-Senghor. 2014. “Whites’ Interpersonal Interactions Shape, and Are Shaped By, Implicit Prejudice.” Policy Insights From the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1 (1): 81–87. doi:10.1177/2372732214549959.

- Sinclair, Stacey, Brian S. Lowery, Curtis D. Hardin, and Anna Colangelo. 2005b. “Social Tuning of Automatic Racial Attitudes: The Role of Affiliative Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (4): 583–592. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.583.

- Stewart, Tracie L. 2003. “Do the ‘Eyes’ Have It? A Program Evaluation of Jane Elliott’s “Blue-Eyes/Brown-Eyes” Diversity Training Exercise1.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 33 (9): 1898–1921. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb02086.x

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1979. “An Intergrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin and S. Worchel, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Thijs, Jochem, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2013. “Multiculturalism in the Classroom: Ethnic Attitudes and Classmates’ Beliefs.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 37 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.012.

- Titzmann, Peter F., Alaina Brenick, and Rainer K. Silbereisen. 2015. “Friendships Fighting Prejudice: A Longitudinal Perspective on Adolescents’ Cross-group Friendships with Immigrants.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44 (6): 1318–1331. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0256-6.

- Van Laar, Colette, Shana Levin, Stacey Sinclair, and Jim Sidanius. 2005. “The Effect of University Roommate Contact on Ethnic Attitudes and Behavior.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 41 (4): 329–345. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2004.08.002.

- Van Zalk, Maarten Herman Walter, Magraret Kerr, Nejra Van Zalk, and Håkan Stattin. 2013. “Xenophobia and Tolerance Toward Immigrants in Adolescence: Cross-Influence Processes Within Friendships.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 41 (4): 627–639. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9694-8.

- Vandenberg, Robert J., and Charles E. Lance. 2000. “A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Suggestions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research.” Organizational Research Methods 3 (1): 4–70. doi:10.1177/109442810031002.