ABSTRACT

In an endeavour to understand connections between immigration policy and contemporary colonialism on Indigenous territory, this study investigates how state-led immigrant integration policies and practices reproduce colonialism in Swedish Sápmi. It explores the applicability of scholarship on settler colonialism on Sweden and develops the notion of banal colonialism by combining scholarship on settler and everyday colonialism with banal nationalism. Drawing from state documents regulating immigrant integration and semi-structured interviews conducted with integration workers in Swedish Sápmi, the study shows that immigrant integration policy largely silences the colonial past and present of Sweden. While the implementation of national-level policies on Indigenous land reproduces majority-centred narratives, also practices challenging the colonial order are identified. The study shows how the notion of banal colonialism captures mundane colonial practices, but also brings attention to instances where immigrant integration policy has the potential of challenging settler colonialism.

Introduction

Sweden’s self-understanding excludes its colonial past and present (Jansson Citation2018, 88–89), even though it has been part of the transatlantic slave trade, the overseas colonization exercised by many European empires (Fur Citation2013; Sjöström Citation2001) and has an Indigenous population targeted by colonial practices. Additionally, Sweden is, like many other Western nation-states, an immigrant-receiving country with linguistic-cultural integration policies often presupposing national homogeneity. In an interrogation of integration practices taking place on the Indigenous territory of Sápmi,Footnote1 this study contributes to an understanding of contemporary colonialism in Sweden, as expressed in relation to immigration. The study suggests the notion of settler colonialism for describing the ongoing, structural colonialism on Indigenous land in Sweden. It also develops the concept of banal colonialism (Dlaske Citation2017; Davis Citation2012; Murphyao and Black Citation2015) by relating settler colonial and postcolonial scholarship to banal nationalism (Billig Citation1995). The concept is useful when describing the structural, everyday, invisibilized, and routinized nature of colonial operations in a state rarely described as settler colonial yet bearing several settler attributes. By indicating “the unremarked upon actions and events that signal Settler belonging” (Murphyao and Black Citation2015, 317), it brings attention to the (in)visibility of colonial consciousness and discourses in relation to Sweden, particularly the nation-building taking place through policies regulating immigrant integration. While many Indigenous Sámi struggle with taking back and revitalizing their language(s) and culture(s), newly arrived immigrants are integrating to a new society. The Swedish state is involved in both processes by on the one hand granting possibilities for Sámi linguistic and cultural revitalization and on the other hand providing civic orientation courses for immigrants, containing requirements to learn “the” national language and “the” societal values of Sweden. When coexisting in a colonized locality, these policies have different and even contradictory aims. Colonialism and immigration are indeed closely intertwined phenomena, whose connections need further scholarly scrutiny (Bauder Citation2011). By analysing presences and absences of Indigenousness in integration policies for adult immigrants in Swedish Sápmi, this study investigates how immigrant integration policies and their implementation in Swedish Sápmi reproduce colonial practices.

The empirical part of the study is based on firstly, an analysis of national-level policy documents on civic orientation programmes and teaching material, and secondly, an analysis of seven semi-structured interviews conducted with integration workers and teachers in civic orientation programmes in Jokkmokk,Footnote2 a municipality with strong presence of both Indigenous persons and immigrants.

Colonialism and contemporary migration

The operations and consequences of colonialism are not uniform. Settler colonial studies have emerged with the aim of describing forms of colonialism that, according to some scholars, require an analytical framework additional to those developed in postcolonial theory (Tuck and Gaztambide-Fernández Citation2013, 75). Settler invasion is ongoing and settler colonialism is characterized by being eliminatory towards Indigenous peoples, motivated by gaining access to territory (Wolfe Citation2006, 387–388), including an intention to make a new home on it (Tuck and Wayne Yang Citation2012, 5).

While the colonial actions of Scandinavian countries have been investigated among others in relation to their colonial complicity (Keskinen et al. Citation2009), scholarship on settler colonialism has mainly focused on contexts where immigration is central for the national imagination (Bauder Citation2011, 517; Spoonley Citation2015, 652), namely on North and South America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Israel. “Ethnically” defined Scandinavian nation-states, and thereby Sápmi, are seldom characterized as settler colonial,Footnote3 yet similarities in − among others − linguistic-cultural challenges can be identified between Sápmi and many Indigenous communities in settler states.

Swedish history-writing is generally characterized by an absence of descriptions of Swedish involvement in overseas colonialism (Naum and Nordin Citation2013, 4), as well as of a lack of Sámi narratives (Fur Citation2008, 1–2). Sweden’s most long-lasting overseas colony was the Caribbean island Saint-Barthélemy between 1784 and 1878, regarded “an integral part of Sweden’s colonial project” (Sjöström Citation2001, 73). Furthermore, 1.5 million Swedes immigrated to North America in the nineteenth century, taking part in displacing Indigenous populations from their lands. Sweden has then governed overseas colonies and taken part in the European settler colonization of North America,Footnote4 in addition to the colonization of Sápmi. Definitions of colonialism often include a separation by “salt water” between colony and heart of empire (Emerson Citation1969). The lack of a sea border to the south of Sweden adds to the terminological ambiguity when describing Sápmi, and thereby to the importance of developing contextually informed colonial frameworks on the dynamics in Sápmi.

Despite a body of scholarship using the term “colonial” in relation to Sápmi (see, e.g. Kuokkanen Citation2007; Magga Citation2018; Össbo and Lantto Citation2011), describing the Swedish expansion to the North as colonialism is controversial; some historians prefer the notion of internal colonization (Fur Citation2013, 26), which however is problematic as the Sámi were only loosely connected to the Swedish state until the sixteenth century (Naum and Nordin Citation2013, 6). A government report from 1986 concludes that the Swedish influence in Sápmi cannot be called colonialism since the process lasted a “very long period of time”, involving extended coexistence and claims of supremacy (SOU Citation1986, 36, 163–164), indicating that colonization needs to be rapid to be considered as such. The main attributes of settler colonialism, namely the territorial takeover and its structural, ongoing and eliminatory nature, can however be identified in Sápmi.

Whereas many Indigenous peoples have been victims of genocide, the process of assimilating Sámi took mainly “administrative” pathways in Sweden, which can be even more eliminatory in some cases “since it does not involve such a disruptive affront to the rule of law that is ideologically central to the cohesion of settler society” (Wolfe Citation2006, 402). Compared to some Western settler states, the Sámi in Sweden are particularly minoritized. On traditional Sámi settlement areas in Sweden, only an estimated 1.69 per cent of the population is Sámi, compared with the mere 0.2 per cent in the whole population (calculated based on Statistics Sweden Citation2019a), while 16.5 per cent of the population of New Zealand is Māori (Stats Citation2018), and 4.9 per cent of Canada’s population is Indigenous (Statistics Canada Citation2016). The majority domination in Sweden is remarkable, partly enabled by the centuries-long policies of assimilation with church and schooling as the major state instruments. The schools for Sámi children between the seventeenth and twentieth century had attributes from colonial, civilizing education, and were inspired by ideas on Sámi racial and cultural inferiority (Lindmark Citation2013, 135, 144). The state actions subsequently developed to “full-blown colonial policies with racial overtones” (Naum Citation2016, 493), processes enabled in part by a centuries-long state-supported settler migration to traditional Sámi territories, a territorial take over and settler home making.

Importantly for the concerns of this study, migration has played a central role for the colonization of Swedish Sápmi. The Swedish Empire explicitly encouraged settler migration to Sámi territories by promising tax alleviations, freeing men from war, and giving land, which by the eighteenth century resulted in established Swedish and Finnish settlements in Sápmi (Fur Citation2005, 361). According to Kymlicka, state practices encouraging people to settle on minority territories “are often deliberately used as a weapon against the national minority, both to break open access to their territory’s natural resources, and to disempower them politically” (2001, 75). While these disempowering tactics have not been used exclusively on Indigenous peoples, virtually all Indigenous peoples have been targeted by them.

Contemporary immigration takes place in a vastly different context, yet may also entail the risk that immigrant communities bolster the colonial system (Saranillio Citation2013, 286). Immigrants and refugees can in some situations be invited to be settlers and in others be illegalized, on settler terms (Tuck and Wayne Yang Citation2012, 17), while Indigenous peoples may have to compete with multicultural policies in resource allocation (Spoonley Citation2015, 652). Hence, contemporary immigration and Indigenous matters are interconnected, regardless of the reasons behind migrating. Kymlicka (Citation2001, 75–76) indeed claims that minorities should have influence over terms of immigrant integration, given the devastating effects of state-led settler policies. In many countries, however, immigrant integration is under full control of the majority state, including in Sweden where the Sámi Parliament is rather a mix of state authority and political representative with a weak mandate (Lawrence and Mörkenstam Citation2012, 208).

Given the connections between migration and settler colonialism, and the weak Indigenous influence over integration policy, the concept of banal colonialism is proposed for analysing immigrant integration policy on colonized land. While the term occurs in prior scholarship (see, e.g. Dlaske Citation2017; Davis Citation2012; Murphyao and Black Citation2015), it has rather been used descriptively or anecdotally than been theorized. Similarly to banal nationalism (Billig Citation1995) that is routinely reproduced in a stabilized manner, the majority-centred underpinnings of immigrant integration seem unquestioned. In colonial contexts, the concept of banal colonialism can be used for analysing the everyday acts of a routinely neglect of the colonial situation. These acts generally do not awaken protests in the same way as for example mining, possibly since they are not “fierce” and debated publicly, but rather products of an established colonial order invisible to many people. The concept can be used to show how the eliminatory colonial structure operates. While some postcolonial scholarship focuses on the banality of predictable, everyday practices in the postcolony (Mbembe Citation1992), the ongoing nature of settler colonialism where no end is in sight, and where Indigenous groups often are heavily minoritized, calls for additional analytical angles. A banal colonialist perspective makes visible not only the taken-for-granted national domination, but also brings attention to the weak presence of “the other”. The word banal does not imply that the operations are harmless, nor that they are unnoticed for everyone; rather, it directs the attention to what has been erased for the dominant to be perceived as banal.

Tracing banal colonialism in integration policy: methodological considerations

As settler colonialism and its institutional practices are “reproduced by narratives, or discourses” (Calderon Citation2014, 316), national-level state documents on integration and interview material from an Indigenous locality in Swedish Sápmi are analysed by applying settler colonial perspectives and developing the concept of banal colonialism. The material has been analysed in connection to silences, hidden meanings and presences of certain ideas, in line with critical ideological analysis (Bergström and Boréus Citation2012, 148–149). The underpinning taken-for-grantedness of the current order and its colonial power relations have been captured through an analysis of mentions and non-mentions of Indigenousness and colonialism.

Integration policy in an Indigenous context is a particularly suitable focus for an analysis of banal colonialism. Firstly, as immigrant integration policies are a constitutive and explicit part of nation-building, interrogations into them contribute to our understandings of relations of dominance in colonized contexts. Secondly, the state expects adult immigrants to lack language skills and knowledge on the nation-state when enrolling in civic orientation programmes, which suggests more explicit nation-building ambitions than in other educational programmes. Finally, in a colonized context, investigating how colonialism is maintained through education is vital, from school curricula to more rarely researched orientation course practices.

The document analysis, based on the regulatory document on Swedish for Foreigners (SFI), one nationally used book for civic orientation, and one nationally used exam for Swedish as second language, aims to illustrate how the state includes Sámi elements in policy and teaching material. The Indigenous context selected for carrying out interviews on the implementation of national policies, Jokkmokk, has an ongoing Sámi revitalization that leads to expect an Indigenous visibility also in terms of immigrant integration. It has a nearly equal proportion between immigrants − almost 13 per cent (Statistics Sweden Citation2019b) − and Sámi − around 15 per cent of the inhabitants being in the electoral register of the Sámi Parliament, the highest percentage in Sweden (Sjöstedt, Karlsson, and Weber Citation2017). Both Lule Sámi and North Sámi are since 2000 recognized as official languages in the municipality. The municipal council made a historical decision to make Lule Sámi lessons obligatory in primary schools in 2018, following a Sámi initiative. The decision, which would have led to Sámi and non-Sámi children alike studying the Indigenous language of the area, was subsequently blocked by the Swedish National Agency for Education (Sameradion & SVT Sápmi Citation2018).

Interviews were carried out in Jokkmokk with four language teachers (LT1-4), one civic orientation teacher (CT), one integration officer (IO) and one cultural officer (CO), following the logic of purposive sampling (Lynn Citation2016, 248) through which different roles within the integration implementation were covered. All interviewees were promised confidentiality. Some interviewees had immigrant background and varyingly close connections to the Sámi, and as semi-structured interviews enables access to the interviewees’ insights, meanings, experiences and memories (Halperin and Heath Citation2017, 289), many interviews led to reflections of a more personal character. They lasted between 20 minutes and one hour, were fully transcribed, and all quotes are translated from Swedish by the author. Questions were asked with the aim of understanding the context (what kind of place is the municipality to immigrate into), the Sámi presence in integration (what Sámi elements are included), who determines the contents (can you decide on the material), the significance of the municipality’s multilingualism (does the multilingualism matter for integration) and perceptions on reactions by immigrants (how do they perceive the Sámi presence).

The banal colonialist analysis of documents and interviews draws from research on banal nationalism, everyday colonialism and settler colonialism. Particular attention is directed to presences and absences of the Indigenous (Calderon Citation2014, 319), erasures and normalizations of colonialism (Masta Citation2016) and the use of “we”, “us” and “them” (Billig Citation1995, 78–83; Antonsich Citation2016). The act of taking the current national order for granted (Billig Citation1995, 44) widely researched in scholarship on banal or everyday forms of nationalism (Skey Citation2009; Jones and Merriman Citation2009), is in this study related to scholarship on the ongoing, similarly taken for granted structure of settler colonialism (Wolfe Citation2006; Veracini Citation2015) and everyday colonialism (Rifkin Citation2014; Mbembe Citation1992). Analysing material where the Indigenous and the expropriation of their lands is absent “registers the impression of everyday modes of colonial occupation” (Rifkin Citation2014, 10), while its presences may either reproduce an inevitability of settler rule (Calderon Citation2014, 326), and thereby (banal) colonialism, or challenge the colonial rule.

The marginality of Sápmi in national-level immigrant integration

Settler colonialism being an eliminatory structure (Wolfe Citation2006), it strives to replace the Indigenous with the dominant language and culture of the majority (Tuck and Gaztambide-Fernández Citation2013, 73). In the guidelines of SFI, one of the most important, nation-wide, state-funded integration measures, the central objective is to learn Swedish (Skolverket Citation2018, 7), other languages remaining unmentioned. In the book About Sweden. Civic orientation in English, distributed by the state to all orientation courses (in 11 different languages), Swedish demographics are described in numerical terms under the title “Population”. What Swedishness is and who constitutes the majority population remains undefined, banally taken for granted. In contrast to the non-definition of the majority population, two pages (out of 233 in the English version) are used for describing the five national minorities, namely the Sámi, Finns, Tornedalean Finns, Roma, and Jews. The Swedish majority (“us”) needs no mention, yet the groups historically excluded from the nation (“they”), even seen as threats to it, are named, yet symbolically marginalized in discourse as “populations”, or “asterisk groups”, while concealing their erasure within the nation-state (Tuck and Wayne Yang Citation2012, 22–23).

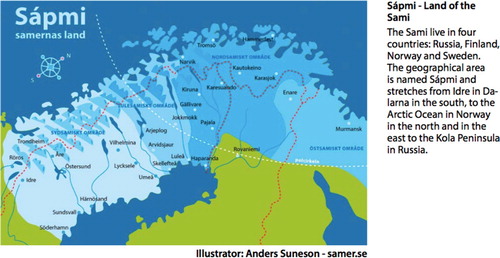

The paragraph on Sámi includes a map with the title “Sápmi − Land of the Sámi” where Sápmi covers half of the Swedish territory (as well as large parts of Norway, Finland, and Russia). Murphayo and Black argue that “names have the ability to carry on banal colonialism” yet can also be “(re)deployed as a challenge to ongoing colonialism” (2015, 326). The toponyms on the map are however in Swedish (or, as typical for settler colonialism, many being appropriated from a Sámi word). Even though the map, used by a Sámi-led organization, could be seen as an Indigenous countermap (Sletto Citation2009, 253), its distribution in this context could also signal how far the Sámi are from achieving territorial rightsFootnote5 and thereby an indication of how non-dangerous Sápmi is perceived to be in the eyes of the state. The map remains virtually uncommented, despite the potential controversies territorial claims could awaken when shown on a map. Colonialism is not mentioned, nor is the treatment of Sámi within the Swedish nation critically investigated. The map that visibly challenges the colonial order can be distributed, since state authorities are not concerned or alarmed by representations where the historical territories of Sápmi are claimed.

Contrary to the texts in the book, an exam by the Swedish National Agency for EducationFootnote6 for students of Swedish as a second language consists only of texts with a critical investigation of the Swedish treatment of Sámi, Tornedalean Finns, and even of the Danish colonialism on Greenland, involving voices of those targeted by assimilatory and colonial policies. Consequently, it challenges the colonial order and thereby provides an alternative to majority-centred narratives erasing colonialism. In settler contexts, the state “is fragmented, incomplete, and challenged by ongoing Indigenous political existence and resistance” (Macoun and Strakosch Citation2013, 432), so also its narratives. The narratives in the test, being written by minorities themselves, thereby exemplify how resistance scatters the voice of the state. Amidst the general erasure of the Indigenous, the few mentions reserved for Sápmi reveal a narrative that both reproduces and takes present power relations for granted and challenges the colonial past and present ().

Immigrant reception on Indigenous territory – (re)producing Sápmi’s marginality

When the majority-centred national-level policies are implemented on Indigenous territory, additional Indigenous perspectives are expected to emerge. Masta argues that “[w]hile changing the curricula to address colonialism is essential, teachers are the first step in changing the discourse in the classroom” (Citation2016, 191). Completing the majority-centred course curricula with local perspectives is indeed left to the discretion of the teacher.

[O]ne has to try to do some more locally inspired material. It’s nothing big. Like for example the winter marketFootnote7 if I take a small example, then you try to teach the words that belong to that, to the winter market, culture and everything related. And that’s when you also learn Sámi words. But they are only few. But most Swedes [in the North] know only few Sámi words. (LT3)

The more advanced stages following SFI were by interviewees however witnessed to include more Indigenous matters, suggesting that one is to first gain knowledge in Swedish and then learn about Sámi in Swedish.

[Visiting] Ájtte [the Sámi museum], and then … they have to have reached a certain level in order to understand, then you can bring in a lecturer or someone who shows something, but most often it is so that the language skills are not enough for such extra things (LT3).

[I]n the beginning when you moved here, then you don’t know, Swede or Sámi, now you can tell a little bit, that he is Sámi, he is Swedish, but then you never thought about it. And it wasn’t that much you heard about the Sámi actually, you thought that, Sweden, it is a Swedish country, no one had heard about the Sámi. In the beginning. But when you learned the language, then, we got to hear a lot about the Sámi in [high] school. (CT)

But they shall know that I don’t understand those who speak Sámi for example. That there are nursing homes with only Sámi speaking staff and customers, I mean it is not appropriate to apply for [positions in] those places for example since the language is decisive, the Sámi language. So that there are Sámi pre-schools and schools, they shall know how the society is built up. And they react on signs. Then I can say that I don’t understand [what is written on the signs]. (LT1)

The other languages are maybe not that significant, such as Sámi, Finnish, Meänkieli … for example in the school, you cannot learn Sámi as a Swede. I personally find it a pity but it is not possible. (LT3)

The marginalized position of minority languages witnessed here can also be connected to the previously mentioned state decision to hinder compulsory Lule Sámi education in all local primary schools, a Sámi-led initiative blocked by the state.

Survival and normality under a colonial structure

Sámi survival in the colonial system is made a responsibility of the Indigenous population, not the state. Scholarship on settler colonialism has been criticized for making Indigenous resistance invisible (Macoun and Strakosch Citation2013, 436), while it is precisely resistance that has the potential of making visible the ongoing colonialism to dominant populations, including persons subject to integration policies. Virtually all interviewees could witness a rise in Sámi visibility, especially among youth.

For the younger I think the agenda is to develop the Sámi society more than has been done before. But the people is [numerically] so small so there always has to be a group that is especially dedicated and that there is now. But one never knows how that develops. (LT3)

[Y]ou hear a bit more and more Sámi out in the society I think, I grew up here, there has been a larger conscience among most of the parents, young parents who transmit the Sámi. … Those friends I played with didn’t speak Sámi with their parents. It was a pity because it almost died out, one can say. But now there is a larger conscience and I hope they fight stone hard in order to make Sámi survive. (LT1)

That has to do with it being a minority culture, then you have to keep the boundary as sharp as you can in order not to be extinguished or assimilated. It is like that all the time. (CO)

[O]ne becomes “home blind”, we don’t think about it since we grew up here, the neighbour has two reindeer on his backyard, or five another winter, you don’t reflect on it because it’s such a natural part. But still many parts of the culture, I still think I am pretty aware, since I have many Sámi friends, but I still feel that I don’t have knowledge about the parts that, I mean reindeer tours are done in the mountains and in the forest. (LT2)

We of course tell about the culture and want them to learn about all people who live in the municipality, both the Swedish culture and the Sámi, the settler culture.Footnote8 So it is nothing that bears the stamp of it in a particular way, because for us the Sámi presence is simply totally natural, it exists, so it is nothing one makes a big deal of. (LT1)

[T]hat is simply natural, we always say it when they come, in the short welcoming talk that we have, because it is also important that you don’t feed people with too much information, they have enough with landing in the fact that they are here and will get food for the day more or less. But successively we bring it up of course, that there is Indigenous population in this area and what it signifies and such things, no there is nothing strange about that. (IO)

In contrast to the integration workers’ narratives, the Sámi presence was reported to being considered as explicitly deviant by the students, indicative of the lack of colonial discourses and Sámi visibility in relation to Sweden also on a global scale.

Yes, they find it a little bit weird, that it is bilingual, this municipality, and that one doesn’t understand [Sámi] at all. But I usually point at the family trees that Swedish and Sámi is not on the same family tree. It is a Finno-Ugric language. And we are Indo-European so then they usually understand better. (LT1)

A division is created between ‘us’ and them’ in order to explain the for students unexpected Sámi presence. The system enables students not having “to think about the violence against Indigenous peoples if [they] choose not to” (Snelgrove, Dhamoon, and Corntassel Citation2014, 7). On the other hand, the knowledge of an “other” within Sweden may contribute to a sense of belonging in the perceptibly homogeneous Sweden.

Multiculturalism and modernity on Indigenous territory

Tuck and Gaztambide-Fernández argue that incorporating Indigenous peoples into a multicultural narrative is committed to settler futurity rather than an Indigenous futurity (Citation2013, 80). Furthermore, “multicultural” approaches to oppression, or making gestures to Indigenous peoples without addressing their sovereignty, are equivocations according to Tuck and Yang (Citation2012, 19). Multiple interviewees however did incorporate the Sámi within a multicultural discourse, identifying connections and alliances formed between minorities. The CT, who originates from a minority group in their country of origin, felt highly connected to the Sámi, especially due to experiences of linguistic repression.

Yes, I feel like a Sámi myself, since I am a [ethnicity]. So I love the Sámi. Today we watched a movie [called] Sámi Blood, it was really, really good. It reminds me of my own culture and the place I grew up in [country]. I am [ethnicity] and cannot write in [language] because it was forbidden to have in the schools there. So it reminds me a lot of my own culture. (CT)

They can say, yes, it is more or less like where I am from, depending on where in the world they come from there can be Indigenous peoples. (IO)

The Swedish is closer. Sometimes someone belongs to an Indigenous group also in their home country, but there are not that many that can draw those parallels. (LT3)

Over all, we have succeeded well with the welcoming. And that we have heard from many directions, and we believe that it is due to us being multicultural already when we started receiving. I absolutely believe that it has a big impact, I believe so. It is self-evident, it is not strange for us that there are differences since we nevertheless are basically similar. (IO)

Many of these newly arrived have then come there to see and say, oh, we had exactly one of them in Afghanistan … it’s a sense of home, it’s the same with this Sámi. It is a lot that they can acclimatize to in their own lives. A factor of recognition. (IO)

The centrality of reindeer herding in Sámi culture can be contrasted with the increasing urbanization and subsequently declining role of animals and agriculture in Sweden. A boy who had previously worked with animals was witnessed to enjoy the opportunity of working with reindeer.

We had a boy who came as unaccompanied minor, because we have tried to have sponsors for those who come, mentors … I remember a guy, he got a mentor who was a reindeer herder, so he was out in the reindeer forest, he felt incredibly at home there. (IO)

[T]here are these, upper and lower strata from the Swedish side, that Scandinavian is up, high up over everything else, and then it is hard for someone else, who maybe doesn’t even have the knowledge to see what was good in [their] country, what has led Sweden to at all reach this level. … you forget that some countries such as Syria for example have had a fantastic cultural development and have been leading, there Sweden is actually nothing … But no one thinks about that, you just see poverty, war, and then people come here and want help. (LT3)

Conclusion

Adding to debates on Sweden’s colonial involvement, this study has explored the applicability of settler colonial theories on the case of linguistic-cultural immigrant integration in Swedish Sápmi. It has contributed to scholarship on settler colonialism firstly by showing how integration policy can maintain colonialism, and secondly by developing the analytical notion of banal colonialism, applicable in both traditionally researched settler states and more ambiguous settler contexts such as Sweden. Moreover, it has made a methodological contribution by showing how the concept may be applied, and an empirical contribution by suggesting such perspectives on contemporary Sweden to policies rarely problematized as (settler) colonial.

Banal colonialism is proven useful to illustrate the ongoing and routinized operations of colonialism when analysing empirical material. The concept captures how policy and its implementation consistently centre the Swedish, and how absences of Sápmi in documents (re)produce colonialism, while its mentions generally silence colonialism. A process of othering indicative of colonialism is revealed in the act of emphasizing the “normality” of the Indigenous, while letting the dominant majority set the norm. Additionally, despite expressing concerns for Indigenous survival, teaching the dominant majority language is unquestioned among the interviewees, and Sámi survival is seen mainly as a Sámi matter. Alongside the identified expressions of banal colonialism, Indigenous revitalization and survival was explicitly supported. The colonial order was challenged when narratives and visual representations by minorities were included in the teaching material, and when the national curricula were complemented with Indigenous perspectives in the classroom. Commonalities and alliances were identified between the Indigenous and immigrants, and the testimonies on some students aligning with Indigenous struggles challenge dominant narratives of integration. Consequently, a potential for alternative practices regarding what it may entail to integrate in Sweden (on colonized land) is identified. As the reproductions of banal colonialism among the state officials could be seen as an effect of an institutional, banally colonial system that permeates all Swedish state actions rather than an indication of “bad intentions” among individuals, the state is implicated in such potential reformulations.

Connecting the phenomena of integration and colonialism and bringing attention to the mundane, seemingly innocent everyday reproductions of the current order, helps us understand how the position of non-dominant groups is not given but constantly reproduced in colonial nation-building processes, within systems that privilege selected narratives. The study does not hold that banal colonialism is less dangerous or problematic than “hot” colonialism, nor that the boundary between “hot” and “banal” is rigid (Jones and Merriman Citation2009, 165–166). Furthermore, it does not in any way imply that Indigenous peoples should direct resources to immigration policies but has rather aimed to point towards the taken-for-grantedness of the colonial present by using nation-building through immigrant integration policy as example. While it is important to raise attention to urgent colonial practices, such as mining and burning of Sámi dwellings, attention should also be continuously directed to institutional practices that go unnoticed for many, mainly non-Indigenous persons, that fail to view the situation as colonial. Routinized, established colonial operations are performed every day on Indigenous land, also in states rarely described as settler colonial. An immigrant integration policy lacking reflection on colonialism is certainly an example of how a colonial system has attained banality. Interrogations into such practices contribute to reformulating and challenging what integration may, and should, mean in colonized localities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A North Sámi term describing the traditional lands of Sámi. Around 80,000 Sámi live in the area, of which an estimated 50,000 in Norway, 20,000 in Sweden, 8,000 in Finland, and 2,000 in Russia.

2 The Swedish name, Jokkmokk, is based on the Lule Sámi Jåhkåmåhkke.

3 For examples of the use of settler colonialism (asuttajakolonialismi) on Finnish Sápmi, see Magga (Citation2018), and for Swedish Sápmi (bosättarkolonialism), see Kyrölä (Citation2017).

4 For a settler colonial perspective on Swedish settlements in the US, see Hjorthén (Citation2015).

5 Such as the ratification of ILO 169.

6 The test for Swedish as a second language on high school level is in use by the Swedish National Agency for Education between 2017 and 2024.

7 Jokkmokk winter market, which has been taking place since 1605.

8 Translated from nybyggarkulturen. Some of the nybyggare were Sámi.

References

- About Sweden. Civic Orientation in English. 2018. City of Gothenburg and the County Administrative Board of Västra Götaland.

- Antonsich, Marco. 2016. “The ‘Everyday’of Banal Nationalism–Ordinary People’s Views on Italy and Italian.” Political Geography 54: 32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.07.006

- Albury, Nathan John. 2015. “Your Language or ours? Inclusion and Exclusion of non-indigenous Majorities in Māori and Sámi Language Revitalization Policy.” Current Issues in Language Planning 16 (3): 315–334. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2015.984581

- Arat-Koç, Sedef. 2014. “An Anti-Colonial Politics of Place.” Intervention–Addressing the Indigenous-Immigration ‘Parallax Gap’. Antipode. https://antipodefoundation. org/2014/06/18/addressing-the-indigenous-immigration-parallax-gap.

- Bauder, Harald. 2011. “Closing the Immigration–Aboriginal Parallax Gap.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 42 (5): 517–519.

- Bergström, Göran, and Kristina Boréus. 2012. Textens mening och makt: metodbok i samhällsvetenskaplig text-och diskursanalys [The Meaning and Power of Text: Social Science Methods in Textual and Discourse Analysis]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

- Calderon, Dolores. 2014. “Uncovering Settler Grammars in Curriculum.” Educational Studies 50 (4): 313–338. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2014.926904

- Davis, Sasha. 2012. “Repeating Islands of Resistance: Redefining Security in Militarized Landscapes.” Human Geography 5 (1): 1–18. doi: 10.1177/194277861200500102

- Dlaske, Kati. 2017. “Music Video Covers, Minoritised Languages, and Affective Investments in the Space of YouTube.” Language in Society 46 (4): 451–475. doi: 10.1017/S0047404517000549

- Emerson, Rupert. 1969. “Colonialism.” Journal of Contemporary History 4 (1): 3–16. doi: 10.1177/002200946900400101

- Fur, Gunlög. 2005. “Invandrare och samer [Immigrants and Sámi].” In Signums Svenska Kulturhistoria. Stormaktstiden [Signum’s Swedish Cultural History. The Era of Great Power], edited by Jacob Christensson, 349–373. Signum: Lund.

- Fur, Gunlög. 2008. “Tillhör samerna den svenska historien [Do the Sámi Belong to Swedish History]?” HumaNetten 22: 1–10.

- Fur, Gunlög. 2013. “Colonialism and Swedish History: Unthinkable Connections?” In Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity, edited by Magdalena Naum, and Jonas M Nordin, 17–36. New York: Springer.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2011. “Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking, and Global Coloniality.” Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (1): 2–38.

- Halperin, Sandra, and Oliver Heath. 2017. Political Research: Methods and Practical Skills. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hjorthén, Adam. 2015. “Border-Crossing Commemorations: Entangled Histories of Swedish Settling in America.” PhD diss., Stockholm University.

- Jansson, David. 2018. “Deadly Exceptionalisms, or, Would You Rather Be Crushed by a Moral Superpower or a Military Superpower?” Political Geography 64: 83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.12.007

- Jones, Rhys, and Peter Merriman. 2009. “Hot, Banal and Everyday Nationalism: Bilingual Road Signs in Wales.” Political Geography 28 (3): 164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.03.002

- Keskinen, Suvi, Salla Tuori, Sara Irni, and Diana Mulinari. 2009. Complying with Colonialism: Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Nordic Region. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Kuokkanen, Rauna. 2007. “Saamelaiset ja kolonialismin vaikutukset nykypäivänä [The Sámi and the Contemporary Effects of Colonialism].” In Kolonialismin jäljet. Keskustat, periferiat ja Suomi [Traces of Colonialism. Centres, Peripheries, and Finland], edited by Joel Kuortti, Mikko Lehtonen, and Olli Löytty, 142–155. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Kymlicka, Will. 2001. “Immigrant Integration and Minority Nationalism.” In Minority Nationalism and the Changing International Order, edited by Michael Keating and John McGarry, 61–84. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kyrölä, Katariina. 2017. “Sameblod och gränsöverskridandets politik [Sami Blood and the Politics of Border-Crossing].” Tidskriften Ikaros 4 (17): 26–27.

- Lawrence, Rebecca, and Ulf Mörkenstam. 2012. “Självbestämmande Genom Myndighetsutövning? Sametingets Dubbla Roller [Self-Determining Parliament or Government Agency? The Curious Double Life of the Swedish Sami Parliament].” Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift 114 (2): 207–239.

- Lentin, Alana, and Gavan Titley. 2011. The Crises of Multiculturalism: Racism in a Neoliberal Age. London: Zed.

- Lindmark, Daniel. 2013. “Colonial Encounter in Early Modern Sápmi.” In Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity, edited by Magdalena Naum and Jonas M. Nordin, 131–146. New York: Springer.

- Lynn, Peter. 2016. “Principles of Sampling.” In Research Methods for Postgraduates, edited by Tony Greenfield and Sue Greener, 244–254. London: Wiley.

- Macoun, Alissa, and Elizabeth Strakosch. 2013. “The Ethical Demands of Settler Colonial Theory.” Settler Colonial Studies 3 (3–4): 426–443. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2013.810695

- Magga, Anne-Maria. 2018. “‘Ounastunturin terrori’ ja uudisasutus Enontekiöllä: Saamelainen poronhoito suomalaisen asuttajakolonialismin aikakaudella [‘The Terror of Ounastunturi’ and Settlers in Enontekiö: Sámi Reindeer Herding in the era of Finnish Settler Colonialism].” Politiikka-Lehti 60 (3): 251–259.

- Masta, Stephanie. 2016. “Disrupting Colonial Narratives in the Curriculum.” Multicultural Perspectives 18 (4): 185–191. doi: 10.1080/15210960.2016.1222497

- Mbembe, Achille. 1992. “The Banality of Power and the Aesthetics of Vulgarity in the Postcolony.” Public Culture 4 (2): 1–30. doi: 10.1215/08992363-4-2-1

- Morgensen, Scott Lauria. 2011. “The Biopolitics of Settler Colonialism: Right Here, Right Now.” Settler Colonial Studies 1 (1): 52–76. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2011.10648801

- Murphyao, Amanda, and Kelly Black. 2015. “Unsettling Settler Belonging: (Re)Naming and Territory Making in the Pacific Northwest.” American Review of Canadian Studies 45 (3): 315–331. doi: 10.1080/02722011.2015.1063523

- Naum, Magdalena. 2016. “Between Utopia and Dystopia: Colonial Ambivalence and Early Modern Perception of Sápmi.” Itinerario (Leiden, Netherlands) 40 (3): 489–521.

- Naum, Magdalena, and Jonas M Nordin. 2013. “Introduction: Situating Scandinavian Colonialism.” In Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity, edited by Magdalena Naum and Jonas M Nordin, 3–16. New York: Springer.

- Össbo, Åsa, and Patrik Lantto. 2011. “Colonial Tutelage and Industrial Colonialism: Reindeer Husbandry and Early 20th-Century Hydroelectric Development in Sweden.” Scandinavian Journal of History 36 (3): 324–348. doi: 10.1080/03468755.2011.580077

- Rifkin, Mark. 2014. Settler Common Sense: Queerness and Everyday Colonialism in the American Renaissance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sameradion & SVT Sápmi. 2018. “Frågan om lulesamiska i Jokkmokk på återremiss [The Question of Lule Sámi in Jokkmokk Recommitted]” September 17. https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2327&artikel=7045112.

- Saranillio, Dean Itsuji. 2013. “Why Asian Settler Colonialism Matters: A Thought Piece on Critiques, Debates, and Indigenous Difference.” Settler Colonial Studies 3 (3–4): 280–294. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2013.810697

- Sjöstedt, Mikaela, Stefan Karlsson, and Eric Weber. 2017. “Jokkmokk har störst andel röstberättigade [Jokkmokk Has Largest Proportion of Voters].” Sameradion & SVT Sápmi, June 4. https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2327&artikel=6668174.

- Sjöström, Rolf. 2001. “Conquer and Educate. Swedish colonialism in the Caribbean island of Saint-Barthélemy 1784-1878.” Paedagogica Historica 37 (1): 69–85. doi: 10.1080/0030923010370105

- Skey, Michael. 2009. “The National in Everyday Life: A Critical Engagement with Michael Billig’s Thesis of Banal Nationalism.” The Sociological Review 57 (2): 331–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2009.01832.x

- Skolverket. 2018. Kommunal vuxenutbildning i svenska för invandrare [Municipal Adult Education in Swedish for Foreigners].” Skolverkets föreskrifter om kursplan för kommunal vuxenutbildning i svenska för invandrare [Regulations of the National Agency of Education on Course Plan for Municipal Adult Education in Swedish for Foreigners]. Norstedts.

- Sletto, Bjørn. 2009. “Indigenous People Don’t Have Boundaries’: Reborderings, Fire Management, and Productions of Authenticities in Indigenous Landscapes.” Cultural Geographies 16 (2): 253–277. doi: 10.1177/1474474008101519

- Smith Tuhiwai, Linda. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed.

- Snelgrove, Corey, Rita Kaur Dhamoon, and Jeff Corntassel. 2014. “Unsettling Settler Colonialism: The Discourse and Politics of Settlers, and Solidarity with Indigenous Nations.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3 (2): 1–32.

- Spoonley, Paul. 2015. “New Diversity, Old Anxieties in New Zealand: The Complex Identity Politics and Engagement of a Settler Society.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 650–661. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.980292

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. 1986. Samernas Folkrättsliga Ställning: Delbetänkande av Samerättsutredning [Position of Sámi within International Law: Interim Report of Inquiry on Sámi Rights].

- Statistics Canada. 2016. “Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Key Results from the 2016 Census.” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm?indid=14430-1&indgeo=0.

- Statistics Sweden. 2019a. “Folkmängd i riket, län och kommuner 31 Mars 2019 och befolkningsförändringar 1 januari–31 mars 2019 [Population in Country, Counties and Municipalities March 31st 2019 and Changes in Population January 1st-March 31st 2019].” https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/tabell-och-diagram/kvartals–och-halvarsstatistik–kommun-lan-och-riket/kvartal-1-2019/.

- Statistics Sweden. 2019b. “Kommuner i siffror [Municipalities in Numbers].” https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/kommuner-i-siffror/#?region1=2510®ion2=.

- Stats, N. Z. 2018. “2018 Census Population and Dwelling Counts.” https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/2018-census-population-and-dwelling-counts.

- Tuck, Eve, and Rubén A Gaztambide-Fernández. 2013. “Curriculum, Replacement, and Settler Futurity.” Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 29 (1): 72–89.

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. ““Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40.

- Veracini, Lorenzo. 2015. The Settler Colonial Present. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. doi: 10.1080/14623520601056240