ABSTRACT

Over the past thirty years, there has been an increase in the number of immigrant day labourers in the United States. The presence of day labourers has led to numerous conflicts in municipalities. Some locals benefit from the labour performed by day labourers and believe they do no harm, while others see them as “illegal” immigrants that pose a threat to the community. For many, the legitimacy of day labourers remains uncertain, which opens a space for opponents and supporters to push for competing policies. Uncertain legitimacy and back and forth conflicts result in policies that are continuously being tugged between exclusionary and inclusionary measures. Whereas much of the literature on local immigration policies suggests that subnational governments opt for either exclusionary or inclusionary measures, this paper reveals the volatility of local immigration policies and the blurring of lines between them.

In 1998 Roswell, a suburb in the state of Georgia, passed an ordinance that prohibited hiring day labourers from private property without permission of the property owner. This exclusionary policy aimed to address complaints by residents and businessowners by limiting where and how Latino day labourers searched for work. Roswell’s passage of an exclusionary ordinance in 1998 appears to be consistent with predictions made by the literature on local immigration policy. This was indeed a town predisposed to exclusionary policies because of its high rate of homeownership, Republican voters, and sharp growth in the Latino population (Ramakrishnan and Wong Citation2010; Visser and Simpson Citation2019; Walker and Leitner Citation2011). However, the exclusionary ordinance passed at this one point in time was not the end of the story.

When some Latino day labourers were cited and arrested for violating the ordinance, day labourer advocates voiced their opposition to the Roswell City Council. They argued that enforcement of the ordinance was discriminatory and that day labourers were losing their trust in the police. In response, a city councilman and the Chief of Police met with Latino leaders to discuss how to improve the day labourer situation. Officials believed that the ordinance was legitimate, but they were willing to support a day labourer hiring centre to meet the needs of immigrant workers in the town. A city-funded day labourer centre was then opened in 2001, prompting protests from some residents and the Georgia Coalition for Immigration Reform. This coalition argued that Roswell was violating federal law by assisting undocumented immigrants or, as they put it, “illegals”. City officials believed the hiring centre did not violate federal law because it was not operated by the city itself, but instead by the Roswell Intercultural Alliance, a nonprofit service provider. Eventually, the centre closed in 2003 due to controversy, a lack of funding, and waning use by workers.

The case of Roswell is not unique. In cities and towns throughout the United States, policies intended to exclude or include immigrants rest on uncertain legitimacy. The absence of broad legitimacy for any set of policies spurs opposing sides into conflicts over the nature, design, and implementation of policies. Local officials may implement exclusionary or inclusionary policies, but they are often met with public resistance because opponents call into question the policies’ legitimacy. Uncertain legitimacy can give rise to drawn out conflicts that push and pull policies in different directions. Thus, demographics, socioeconomic characteristics, and political affiliation may certainly favour one policy over another (as the literature suggests), but this paper maintains that these factors are not destiny. The uncertain legitimacy of policies, even in conservative towns like Roswell, Georgia, contributes to a dynamic, conflictual and muddled policy making process.

Local conflicts about day labourer activities often revolve around public safety issues, such as pedestrian and traffic safety, and the presumed unauthorized immigration status of day labourers. Day labourers are considered to be “illegal immigrants” that pose a potential criminal threat to the community (Crotty Citation2017; Varsanyi Citation2008). To address local conflicts, localities have employed different approaches (Crotty Citation2017; Nicholls Citation2019; Varsanyi Citation2008; Visser et al. Citation2017). Some have tried to exclude day labourers from the local community, with excluding policies such as no-solicitation ordinances and increased police enforcement. Others tried to include day labourers into the community, with inclusive policies such as setting up a hiring centre. Why some localities adopt an inclusive approach while others prefer an exclusionary approach has been the topic of several studies (Hopkins Citation2010; Huang and Liu Citation2018; Ramakrishnan and Wong Citation2010; Visser and Simpson Citation2019; Walker and Leitner Citation2011). Demographic, socioeconomic and political factors have been identified as influencing the direction of local immigration policies. However, these studies have overlooked the dynamic character of local immigration policies. As the case of Roswell suggests, local immigration policies are oftentimes neither completely exclusionary nor inclusionary and are often pulled in different directions by competing political camps.

This paper draws on the literatures on local immigration policy and policy legitimacy to argue that the uncertain legitimacy of day labourers contributes to conflicting mobilizations and policy instability. A significant share of day labourers consists of undocumented immigrants, who are unable to obtain jobs in formal labour markets (Crotty Citation2015; Varsanyi Citation2008). Day labourers occupy a disputable position, as they contribute to economic growth but do so in an unregulated market and presumably without authorized immigration status (Crotty Citation2017). Some view day labourers as legitimate and prefer inclusionary policies, whereas others believe that day labourers are illegitimate and favour exclusionary policies. Ambivalent legitimacy opens up a space of political uncertainty, allowing competing political forces to assert their policy preferences and opposition to their adversaries. When competing sides can accrue sufficient resources, their conflicts can endure for fairly long periods of time. Elected officials often respond by constantly recalibrating policies to address the competing interests. Rather than producing exclusionary or inclusionary cities, uncertain legitimacy and associated battles often result in policy instability and a muddled combination of the two. The paper develops these arguments through the use of an extensive newspaper database (1990–2016) on local day labourer conflicts and city council minutes of four case study cities.

Literature review

Local immigration policy

In the United States, there has been a sharp uptick of local immigration policies over the past thirty years (Hanlon and Vicino Citation2015; Huang and Liu Citation2018; Varsanyi Citation2008; Visser and Simpson Citation2019). The growing policy activism has been spurred by the devolution of authority and responsibilities from the federal to local governments (Varsanyi Citation2010). For instance, through the 287(g) programme, local officials are trained to enforce immigration law (Armenta Citation2017; Provine et al. Citation2016). In addition, local policy activities have increased in response to the inability at the federal level to pass comprehensive immigration reform (Crotty Citation2017; Visser and Simpson Citation2019). Due to a lack of federal legislation, local governments are forced to come up with their own policies to deal with the effects of immigration.

Whether local immigration policies are inclusionary or exclusionary varies across municipalities and states. This has resulted in what Provine and her colleagues call a “multijurisdictional patchwork” (Provine et al. Citation2016). Scholars have identified several factors influencing the direction of local immigration policies. Partisanship, politicization, immigrant growth rate, educational attainment level, type of housing, share of the Latino population, and saliency of immigration at the federal level have all been found as factors influencing the preference of localities for an inclusionary or exclusionary approach towards immigrants (Hopkins Citation2010; Huang and Liu Citation2018; Ramakrishnan and Wong Citation2010; Visser and Simpson Citation2019; Walker and Leitner Citation2011). In addition, it has been stated that central cities are often more diverse and welcoming to immigrants, whereas suburbs, characterized as “White, middle-class and privileged”, try to create barriers against immigrants (Hanlon and Vicino Citation2015; Lal Citation2013; Walker and Leitner Citation2011).

In spite of the literature’s many strengths, it suggests that local and state policies are fixed as exclusionary or inclusionary, and that policy outcomes are largely determined by a locality’s demographics and political affiliations. This assumption cannot account for cases like Roswell where policies oscillate between exclusion and inclusion in a fairly conservative town. Cases like Roswell suggest that inclusion and exclusion are not fixed policy positions, but end points on a spectrum of local government control. Elected officials are positioned within this spectrum and are tugged in inclusionary and exclusionary directions in response to the demands of competing constituencies (Nicholls Citation2019). The dynamic, fluid and in-between nature of local immigration policies has also been emphasized by Daamen and Doomernik (Citation2014) in their study of Montgomery County, Maryland. In addition, Walker (Citation2014, Citation2018) has found that the characterization of suburbs as homogenously exclusionary towards immigrants is outdated as suburbs grow increasingly diverse. Thus, local demographic, socioeconomic and political characteristics certainly matter, but they do not lock localities into inclusionary or exclusionary policies. Local immigration policies appear to have a dynamic character and shift between the inclusionary and exclusionary sides of the spectrum.

Policy legitimacy

One way to explain the dynamic messiness of local immigration policy is by understanding the degree to which such policies gain legitimacy in local political arenas.

Legitimacy is understood as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Walker and McCarthy Citation2010, 318) Legitimacy involves the moral justification of power relations and government policy, and it is produced through an interactive process with one or more audiences (Gnes and Vermeulen Citation2018, Citation2019). Lastly, legitimacy is situational, because time, place and audience are subject to change (Gnes and Vermeulen Citation2019).

What is considered to be legitimate by the state (“legal”) does not always correspond with what non-state actors consider to be legitimate (“licit”) (Abraham and van Schendel Citation2005). The disconnect between law and popular legitimacy can, Yiftachel (Citation2009) argues, result in “grey spaces” in local policy that include activities, people and developments that are neither integrated nor excluded. Often these grey spaces are tolerated by authorities, but also framed as undesired, dangerous and criminal. This results in “grey spacing” in which the borders of what is tolerated are continuously renegotiated (Yiftachel Citation2009). This form of uncertain and contested legitimacy can result in policies that move back and forth between including and excluding certain people, activities and developments.

In the case of immigration policies in the United States, a recurring topic is the legitimacy of undocumented immigrants. By making claims that refer to different normative frames, actors aim to legitimize their position (Gnes and Vermeulen Citation2019). In the United States the multi-layered structure of the American nation-state offers two competing normative frames to actors to justify their stance. On one side, the federal government has the authority to admit and exclude persons to the nation state (Wells Citation2004). This provides opponents of undocumented immigrants with a normative frame to claim that exclusion of undocumented immigrants is legitimate as their presence is unauthorized. On the other side, local authorities have to abide by the notion of equal personhood and equal rights to all who are territorially present in the United States (Wells Citation2004). This offers supporters of undocumented immigrants with a normative frame to claim that inclusion of undocumented immigrants is legitimate as the rights of all persons should be safeguarded regardless of immigration status. This way, opponents and supporters of undocumented immigrants can refer to different normative frames to legitimize inclusionary or exclusionary immigration policies. The ambivalent legitimacy of undocumented immigrants can therefore produce grey spaces of immigration policy, where opponents and supporters battle over what is tolerated.

Uncertain legitimacy provides room for opponents and supporters of undocumented immigrants to influence policy debates through outsider tactics such as protests and insider tactics such as lobbying or litigation (Steil and Vasi Citation2014). By making claims actors aim to mobilize support and try to pressure public or private actors to alter their policies or practices (Gnes and Vermeulen Citation2019). The presence of different motives and resources offers supporters and opponents of undocumented immigrants a varying degree of opportunities to challenge legitimacy. For instance, Okamoto and Ebert (Citation2010) argue that protest by immigrant groups and advocates is promoted when immigrants face (the threat of) exclusion. Supporters of undocumented immigrants can also benefit from the support of local humanitarian and religious organizations (de Graauw, Gleeson, and Bloemraad Citation2013; Nicholls Citation2019). On the other hand, anti-immigrant activities can be triggered by the integration of immigrants in local housing and labour markets predominated by native-born residents (Okamoto and Ebert Citation2010). Opponents of undocumented immigrants can also profit from the presence of local elected officials who employ the issue of immigration to bolster their chances in competitive elections (Huang and Liu Citation2018; Newman Citation2013). Both supporters and opponents of undocumented immigrants can also draw on some level of support from nonlocal organizations. Thus, the uncertain legitimacy of immigrants and the policies developed to govern them creates a space for opposing sides to mobilize their resources to implement their preferred policies. When opposing sides possess symmetrical motives and resources, it is more difficult for one side to achieve a decisive and durable win. This can result in local immigration policies being pushed and pulled between inclusionary and exclusionary over long periods of time.

The paper addresses these issues through the case of immigrant day labourers. The number of day labourers has increased considerably since the 1990s, which has resulted in local tensions and efforts to introduce policies to control the population (Crotty Citation2015, Citation2017; Varsanyi Citation2008; Visser et al. Citation2017; Nicholls Citation2019). Day labourers are employed in an unregulated market and a large share of day labourers is undocumented. This leads some residents, businessowners and local (elected) officials to argue that day labourer activities are illegitimate and should be eliminated, as they are a threat to public safety and violate federal immigration law (Crotty Citation2017; Varsanyi Citation2008; Wells Citation2004). On the other side, advocates, nonprofit and religious organizations stress the notion of equal rights and personhood to protect undocumented day labourers from exclusionary policies and to promote their integration (Wells Citation2004). Thus, in the space offered by the disputable position of day labourers and the multi-layered structure of the American nation state, actors try to steer local policy debates through a process of legitimation. This can result in a push and pull between supporters and opponents of day labourers. This paper intends to show the dynamic character of local immigration policies, by focusing on the discrepancy between day labourer policies and the legitimacy of day labourers.

Methods

The data for this research is based on two sources. The first consists of a dataset that contains claims on day labourer issues in the United States between 1990 and 2016. This period covers both the rise of day labourers and the growing importance of local policies to address immigrants in these communities. These claims have been obtained from newspaper articles that were found through LexisNexis searches for the keywords “day laborer” and “anti-solicitation” in US newspapers. The methodology that has been pursued is the “political claims analysis” method. This methodology considers all the claims of all institutional and non-institutional actors, providing a more complete reading of the field (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999).

The unit of analysis consists of elements of newspaper articles, namely claims made by actors on day labourer issues. Hagen (Citation1993) has argued that journalistic norms of diversity and balance in practice often are not met. Journalists do objectively report the content of claims made by actors, however, they do not provide equal space to all actors to voice their claims. Journalists tend to publish more claims of actors that in general share the same viewpoints as the editorial line of the newspaper (Hagen Citation1993). Using a single newspaper as data source, could bias the results. To address this issue, we have included multiple newspapers and made a large set of observations (775 newspaper articles, containing 5,951 claims). This way we can argue that the claims in our database provide an accurate overview of the positions of actors on day labourer issues (Helbling and Tresch Citation2011).

This dataset provides information on the newspaper articles as well as information on the claim-makers. From this dataset, a sample has been drawn, that includes localities that had ten or more articles published on day labourer issues. The sample includes thirty-two municipalities; five central cities,Footnote1 and twenty-seven suburbs.Footnote2 The sample contains 775 newspaper articles and 5,951 claims. The claims (statements made by different actors), claim-makers (people making statements), policies, and mobilizations included in the sample are related to day labourer issues. They were coded using a predeveloped but open coding scheme, to systematically analyse day labour issues while also allow to add relevant codes when necessary. Based on the coded dataset, descriptive tables and graphs have been created.

In this paper, a distinction is made between central cities and suburbs. All localities in the sample are located in urbanized areas. An urbanized area is defined as “a continuously built-up area with a population of 50,000 or more” (Bureau of the Census Citation1994, 1). One or more central places are located within an urban area, and the surrounding area consists of other densely settled places that together make up the urban fringe (Bureau of the Census Citation1994). Urbanized areas thus consist of both central cities and suburbs. In this paper, central cities are defined as principal cities in an urbanized area with a population of 250,000 or more. The remaining localities in the sample are located in urbanized areas, but have a population of less than 250,000 and are therefore defined as suburbs.

The paper develops several measures to assess demographics and political affiliation. First, in order to examine the influence of demographic factors for all thirty-two municipalities, demographic data has been obtained from 1990, 2000, and 2010 Census, complemented by 2000 and 2010 American Community Survey data. The demographic data consists of the population by race, educational attainment, and housing. Second, to measure political affiliation of the thirty-two localities, election results from presidential elections in the period 1992–2016 have been gathered.

To assess municipal responses to day labourers three central measures are used. First the “policy score” indicates how a locality scores on a scale ranging from exclusionary day labourer policies (−1) to inclusionary day labourer policies (+1). Adapted from Giugni et al. (Citation2005), all day labourer policies in our sample have been coded as exclusionary (−1), neutral (0), or inclusionary (1). Then for each locality an average “policy score” has been calculated by adding all policy scores for that locality and then dividing by the total number of coded day labourer policies for that locality. For instance, if a municipality has created five distinctive day labourer policies, of which three are exclusionary, one neutral and one inclusionary, the policy score is (−1±1±1 + 0+1)/5= −0.40. Second, the “legitimacy score” displays how actors perceive the legitimacy of day labourers ranging on a scale from illegitimate (−1) to legitimate (+1). Again adapted from Giugni et al. (Citation2005) all claims made by actors in our sample have been coded as illegitimate (−1) neutral (0), or legitimate (1). For each municipality a “legitimacy score” has been calculated by adding all legitimacy scores for the municipality and then dividing by the total number of claims for the municipality. For example, if a municipality has seven claims of which two consider day labourers to be illegitimate, two neutral, and three legitimate, the legitimacy score is (−1±1 + 0+0 + 1+1 + 1)/7 = 0.14. Finally, in order to assess if policy scores are stable, a “policy stability score” has been calculated. The “policy stability score” represents the highest percentage of consensus on a certain category. For instance, a policy stability score of 73 per cent indicates that 73 per cent of the policies fall into one category. This shows relatively stable policies, as a large majority (73 per cent) belongs to the same category.

The second data source consists of the council minutes of Costa Mesa, CA, and Laguna Beach, CA, between 1988 and 2016. And the council minutes of Gaithersburg, MD, and Herndon, VA, between 2000 and 2016. The time range for council minutes of Costa Mesa and Laguna Beach covers a longer period because these municipalities have implemented day labourer policies since 1988. Gaithersburg and Herndon have been implementing day labourer policies since 2000. This data source has been used for the case studies of these four suburbs, to provide an in-depth examination of the local day labourer policies in these localities.

Findings

Cities and suburbs

As discussed in the literature section, a multijurisdictional patchwork of local immigration policies has emerged in the United States since the 1990s. Several studies have identified factors that prescribe the direction of local immigration policies. Growth of the Latino population, a lower level of education, a high rate of owner-occupied housing, voting Republican, and being classified as a suburb all increase the likelihood of a preference for exclusionary local immigration policies (Hopkins Citation2010; Huang and Liu Citation2018; Lal Citation2013; Visser and Simpson Citation2019; Walker and Leitner Citation2011). indicates that most of these factors are present in the suburbs in our sample, and accordingly day labourer policy scores in the suburbs on average are exclusionary (−0.20). In central cities on the other hand, where the increase of the Latino population is smaller, there is less owner-occupied housing and fewer residents are voting Republican, day labourer policies on average are inclusionary (0.50). These findings are in line with the literature.

Table 1. Central cities vs. suburbs: demographics, policy and legitimacy, 1990–2010.

However, the legitimacy and stability scores indicate that this is not the end of the story. Although there is a large difference in policy scores between central cities and suburbs, the legitimacy of day labourers is roughly the same: 0.09 for central cities and 0.02 for suburbs. This indicates that policies and legitimacy do not align in both central cities and suburbs. In addition, the stability scores point at local battles over policies and legitimacy, especially in suburbs. For instance, the policy stability score in suburbs is 50.60 per cent in favour of exclusionary policies. This score suggests a very high level of policy instability, with policies changing between positions over an extended period of time. Thus, a focus on demographic, socioeconomic and political factors as determinants of local immigration policies conceals the dynamic character of these policies. Policies are unstable and an important factor contributing to this instability seems to be uncertain legitimacy. Local battles over the legitimacy of day labourers appear to contribute to policies being swayed between the inclusionary and exclusionary ends of the spectrum.

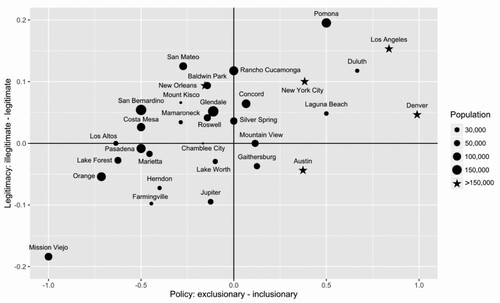

The discrepancy between day labourer policies and legitimacy is displayed in Graph 1. Four different categories of alignment and non-alignment can be distinguished with regard to local day labourer policies and legitimacy:

– Contested exclusion: municipalities that on average prefer exclusionary policies, while actors on average perceive day labourers as legitimate

– Endorsed exclusion: localities where the policy preference of exclusion aligns with the perception of actors that day labourers are illegitimate

– Endorsed integration: municipalities in which the policy preference of inclusion aligns with the perception of actors that day labourers are legitimate

– Contested integration: localities that on average prefer inclusionary policies, whereas actors on average perceive day labourers as illegitimate.

Graph 1 shows that there is much variation among localities, especially among suburbs. It is important to note, that the range of the y-axis suggests that the legitimacy of day labourers has been contested in all four categories. For full consent, the legitimacy score has to be close to −1 (illegitimate) or 1 (legitimate), but instead all localities group together on a narrow band ranging from −0.2 to 0.2. These findings suggest that for many municipalities policies and legitimacy do not align, and in localities where there does seem to be alignment, the alignment is narrow.

In addition to illustrating the discrepancies between policies and legitimacy scores, Graph 1 also shows variation by size of the population. As was mentioned in the literature review, previous studies have made a distinction between large and diverse central cities that are inclusionary towards immigrants, and smaller and homogenous suburbs that are exclusionary (Hanlon and Vicino Citation2015; Lal Citation2013; Walker and Leitner Citation2011). One could expect that the larger the suburb the more it resembles a central city and, consequently, will be more inclusionary towards immigrants. This way the variation among suburbs could, to an important extent, be explained by municipality sizes, where large suburbs are inclusionary and small suburbs are exclusionary.

The day labourer policy preferences of suburbs vary across population size (see Graph 1). For instance, Pomona and Pasadena have similar population sizes but Pomona (0.50) preferred inclusionary policies while Pasadena (−0.50) favoured exclusionary policies. Another example, the small suburb Laguna Beach (0.50) mostly preferred inclusionary policies, whereas the much larger suburb Orange favoured exclusionary policies (−0.71). These findings suggest that there is no clear relationship between size of a suburb and preferred day labourer policies. There also does not seem to be a clear relationship between population size and legitimacy of day labourers. Most suburbs cluster around a legitimacy score of zero, indicating diverging opinions on the legitimacy of day labourers.

Thus, the variation in day labourer policies among suburbs, does not seem to be caused by the population size of a suburb. Smaller suburbs can be inclusionary, while larger suburbs are exclusionary and vice versa. However, a common feature of suburbs seems to be the contested legitimacy of day labourers. For instance, in Baldwin Park where day labourer policies were mostly exclusionary, mayor Lozano argued that although he empathizes with the day labourers, the harassment of Baldwin Park residents by day labourers is illegitimate. Lozano, therefore, believed that a no-solicitation ordinance was a proper solution. Councilmember Pacheco disagreed, and argued that day labourers are just asking for work and that the ordinance criminalizes a legitimate activity.Footnote3 On the other hand, in Gaithersburg where policies on average were inclusionary, a majority of the council at first argued that a day labourer centre would be a humanitarian solution to address public safety issues.Footnote4 However, residents fiercely opposed a centre arguing that nuisance caused by day labourers was illegitimate as was providing assistance to undocumented immigrants.Footnote5 To explore the local battles over day labourer legitimacy in suburbs in more detail, the next section discusses four case studies.

Case studies of dynamic policies

To examine the dynamic character of day labourer policies, four suburbs are analysed. Each suburb represents a category of policy-legitimacy alignment displayed in Graph 1 above. Costa Mesa, CA, can be seen as “contested exclusion”, as policies were mostly exclusionary but fiercely opposed by supporters of day labourers. Laguna Beach is classified as “endorsed integration”, as most actors perceived day labourers as legitimate and policies accordingly were inclusionary. Herndon is identified as “endorsed exclusion”, as the exclusionary policies aligned with the dominant perception that day labourers are illegitimate. Finally, Gaithersburg is classified as “contested integration”, as inclusionary policies were fiercely resisted by local actors. The case studies provide insight into the local battles over policies and legitimacy and stress the importance of the dynamic character of policies. Even in places were policy and legitimacy seem to align, opposing voices are still present and oftentimes also heard.

Costa Mesa, CA

Costa Mesa is a rather large suburb that had 109,960 residents in 2010. A majority of the residents voted Republican during Presidential elections between 1992 and 2016, and the Latino population increased from 199 per 1000 residents in 1990 to 358 per 1000 residents in 2010. The political preference and influx of Latinos created an environment that facilitates exclusionary immigration policies. Accordingly, day labourer policies in Costa Mesa were on average exclusionary (−0.50). However, when the policy debates in Costa Mesa are examined in detail, it is revealed that discussions on the legitimacy of day labourers have pushed the policies back and forth.

Based on Graph 1, the day labourer situation in Costa Mesa can be classified as “contested exclusion”. Policies were on average exclusionary, but faced important opposition. An important point of discussion was the immigration status of day labourers. After the creation of a Job Center and no-solicitation ordinances in 1988, some residents and officials believed that the problems were alleviated. Other residents and councilmembers, however, argued that the Job Center should only be open to legal residents. Councilmember Orville stated that “the day workers that are here legally should be assisted, but illegal aliens should not be tolerated”.Footnote6 Opponents of the Job Center started asking for closure of the Centre. Councilmember Chris Steel stated that “the influx of undocumented workers into the City, drawn by the Job Center, is a major problem”.Footnote7 In 2005 supported by Mayor Allan Mansoor, who employed the issue of illegal immigration to bolster his political career, the Job Center was closed. However, not everyone agreed. Councilmember Katrina Foley opposed the closure, she stated that “It seems wrong for us to be talking about people seeking work as if they’re criminals. We have a reality (of day workers) that’s not going away, and we need to plan for it” (Martinez Citation2005). In 2013 day labourer advocates gained a victory when Costa Mesa was forced to repeal its no-solicitation ordinance when a judge ruled that a similar ordinance violated the First Amendment. Thus, the presence of councilmembers and a mayor who framed “illegal immigration” as a threat to the community facilitated the creation of exclusionary day labourer policies. However, supporters of day labourers challenged these viewpoints and succeeded in reversing some of the exclusionary policies.

Laguna Beach, CA

Laguna Beach is a small suburb located in close proximity to Costa Mesa. It had 22,723 residents in 2010. The share of Latino residents did not change much between 1990 (69 per 1000 residents) and 2010 (73 per 1000 residents). A majority of the residents voted for a Democratic Presidential candidate during elections between 1992 and 2016. The absence of a large influx of Latinos coupled with the political affiliation of residents increases the likelihood of a preference for inclusionary immigration policies. Accordingly, on average Laguna Beach created mostly inclusionary day labourer policies (0.50).

As shown in Graph 1, the day labourer situation in Laguna Beach can be identified as “endorsed integration”. On average, day labourers are seen as legitimate which aligns with the inclusionary day labourer policies. David Peck of the Cross Cultural Council, the organization that operates the day labourer centre opened in 1999, explains: “Have there been objections to the site? Some, but for the most part the response to the site has been positive because it eliminated public-safety problems. This is a progressive community – an island in Orange County – and local people see the benefits” (Cabrera Citation2006). However, this does not mean that Laguna Beach’s policies went unchallenged. A resident and activist mobilized with the help of Judicial Watch and the Minutemen to try to shut down the day labourer centre. According to Eileen Garcia “They [Laguna Beach] should not spend taxpayer money for any activity that pertains to illegal immigration” (Ignatin and Taxin Citation2006). However, the city council and most residents perceived the day labourer centre as a benefit to the city. Laguna Beach Mayor Steve Dicterow stated “We’re not going back to 15 years ago, where there were multiple locations disrupting our neighbourhoods. This has nothing to do with the city perspective or whether we like it or not. It’s taking care of our residents” (Wisckol et al. Citation2006). Thus, although there was some opposition to the inclusionary day labourer policies in Laguna Beach, the opposition was not powerful enough to gain ground in this rather liberal environment.

Herndon, VA

Herndon is located in Virginia and had 23,292 residents in 2010. The small suburb experienced a rapid growth of the Latino population, increasing from 96 per 1000 residents in 1990 to 336 per 1000 residents in 2010. The large influx of Latinos can spark tensions that facilitate exclusionary immigration policies. However, most residents also voted for a Democrat during Presidential elections between 1992 and 2016, which can promote an inclusionary approach. The data indicates that Herndon on average preferred exclusionary day labourer policies (−0.40). But day labourer issues have been a very controversial issue in Herndon, as the small suburb even made national headlines with its local struggles.

Based on Graph 1 the day labourer situation in Herndon can be classified as “endorsed exclusion”. Day labourer policies were mostly exclusionary, and this aligns with the perception that day labourers are illegitimate. However, this classification does not do justice to the local battles in Herndon over day labourer policies and emphasizes the importance of the narrow band of legitimacy in Graph 1. The average legitimacy score of Herndon is illegitimate (−0.07) but its score is close to zero, indicating fierce battles over the legitimacy of day labourers. In 2005 the Herndon council decided to open a day labourer centre to address residents’ complaints. As Mayor Michael O’Reilly explained: “The current situation is unacceptable. Our choice is between having a regulated site and an unregulated site. Given those options, I’m in favor of a regulated site” (Morello Citation2005). This decision was met with fierce resistance, and opponents mobilized with the help of the Federation for American Immigration Reform, Judicial Watch and the Minutemen. At the next council elections, councilmembers voting in favour of the site were defeated. The new council closed the centre and decided to participate in local immigration enforcement programmes such as the 287(g) programme and E-Verify. Day labourers and their advocates did voice their opposition to these measures and succeeded in easing the no-solicitation ordinance. Thus, the case of Herndon shows how tensions over local demographic changes can empower opponents of inclusionary day labourer policies. But this is not to say that day labourer advocates had no voice at all, they too succeeded in relaxing some of the exclusionary measures.

Gaithersburg, MD

Gaithersburg is located in Maryland and had 59,933 residents in 2010. The situation of Gaithersburg is comparable to Herndon. The suburb experienced a large population growth between 1990 and 2010, in which the share of Latino residents increased from 93 per 1000 residents to 242 per 1000 residents. Also a majority of the residents voted for a Democratic Presidential candidate during elections between 1992 and 2016. However, unlike Herndon, Gaithersburg on average preferred inclusionary day labourer policies (0.13). Just like Herndon, these policies faced a lot of opposition.

The day labourer situation in Gaithersburg can be identified as “contested integration” (see Graph 1). The perception that day labourers are illegitimate did not align with the mostly inclusionary day labourer policies. Gaithersburg is located in Montgomery County and the County played an important role in the day labourer policy debates. The County already operated two day labourer centres when tensions started to emerge in Gaithersburg around day labourer activities. According to County officials, the most pragmatic solution to these issues would be the creation of a day labourer centre in Gaithersburg. County Council President Tom Perez stated “The county is unequivocally committed to funding a day-labour centre in Gaithersburg. The money is there. The only issue left is for the city of Gaithersburg to work with all the community stakeholders to identify an appropriate location” (Trejos Citation2005). However, city officials were met with fierce resistance. Residents residing in the neighbourhood where the unregulated day labourer activities took place, did not want the centre in their neighbourhood. Businessowners also did not want a centre near their business, and some anti-immigrant activists tried to stop the city from catering to undocumented immigrants altogether. On the other hand, day labourers, their advocates and religious leaders argued for a humane solution and in favour of a centre. Due to these pressures, city officials decided to inform Montgomery County that no appropriate location for a centre could be found in Gaithersburg. In response, the County decided to open a centre just outside city limits. And, when the Gaithersburg city council decided to create a no-solicitation ordinance, the State Attorney of Montgomery County refused to prosecute citations written under this ordinance. The case of Gaithersburg shows, just like Herndon, how demographic changes can empower opponents of day labourers. However, the involvement of liberal-minded County officials provided day labourer supporters with an equally strong position. This resulted in a push and pull between inclusionary and exclusionary policies.

Conclusion

The example of Roswell, that was introduced at the start of this paper, illustrated how local demographic, socioeconomic and political factors formed the baseline for the direction of Roswell’s day labourer policies. Though immigration literature suggests that these factors determine the endpoint of Roswell’s day labourer policies, in contrast this paper argues that these factors provide a point of departure as day labourer policies are dynamic.

Roswell’s day labourer policies were not fixed to one end of the spectrum, as is the case for many other municipalities in the United States. As was shown in this paper, implementation of a day labourer policy often results in local battles as day labourer policies and the legitimacy of day labourers do not align. Some believe that day labourers are legitimate and should be included because they contribute to the economy and possess rights regardless of immigration status. Others, however, argue that day labourers are illegitimate and should be excluded because they are unauthorized immigrants and pose a threat to public safety and the quality of life of the community. By making claims, opponents and supporters of day labourers aim to define the legitimacy of day labourers and alter local day labourer policies. Opponents and supporters of day labourers draw from different motives and resources when challenging the legitimacy of day labourers, providing them with different opportunities and resources in varying local contexts.

As was shown in this paper, municipalities can be classified into four categories with regard to policy-legitimacy alignment. In the cases of “endorsed exclusion” and “endorsed integration” day labourer policies and perceptions of day labourer legitimacy roughly align. In these instances, there are little motives or resources for actors to challenge the implemented day labourer policies. In the cases of “contested exclusion” and “contested inclusion” day labourer policies and the legitimacy of day labourers do not align. In these instances, actors were able to draw from motives and resources to challenge local day labourer policies. Although the policy-legitimacy alignment categories are helpful to illustrate how battles over the legitimacy of day labourers can contribute to dynamic day labourer policies, they should not be perceived as clear-cut and fixed categories. Even in cases where one side has more power, opposing voices still try to get their message across. For instance, Laguna Beach can be classified as “endorsed integration”, but that does not mean that opponents of day labourers did not try to alter these policies. However, these opponents were not able to overturn Laguna Beach’s day labourer policies. Thus, the influence of actors trying to challenge policies in municipalities were policies and legitimacy largely align might be marginal, but it is still important to recognize their contribution to the dynamic character of local day labourer policies.

It is important to pay attention to the dynamic character of local immigration policies because it helps to understand how policies develop over time. By emphasizing the changing character of local immigration policies, the important role of (local) actors is revealed. By challenging the legitimacy of day labourers, or undocumented immigrants in general, actors are actively involved in shaping local immigration policies. Demographic, socioeconomic and political factors may steer a municipality in a certain direction of immigration policies, but actors engaged in collective action cast the decisive vote.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Austin, Denver, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York.

2 Baldwin Park, CA; Chamblee, GA; Concord, CA; Costa Mesa, CA; Duluth, GA; Farmingville, NY; Gaithersburg, MD; Glendale, CA; Herndon, VA; Jupiter, FL; Laguna Beach, CA; Lake Forest, CA; Lake Worth, FL; Los Altos, CA; Mamaroneck, NY; Marietta, GA; Mission Viejo, CA; Mount Kisco, NY; Mountain View, CA; Orange, CA; Pasadena, CA; Pomona, CA; Rancho Cucamonga, CA; Roswell, GA; San Bernardino, CA; San Mateo, CA, Silver Spring, MD.

3 Baldwin Park City Council meeting, August 15, 2007

4 Gaithersburg City Council meeting, September 19, 2005

5 Gaithersburg City Council meeting, July 26, 2006

6 Costa Mesa City Council minutes, July 5, 1988

7 Costa Mesa City Council minutes, April 1, 2002

References

- Abraham, Itty, and Willem van Schendel. 2005. “The Making of Illicitness.” In Illicit Flows and Criminal Things: States, Borders, and the Other Side of Globalization, edited by Itty Abraham and Willem van Schendel, 1–37. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Armenta, Amada. 2017. Protect, Serve, and Deport: The Rise of Policing as Immigration Enforcement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bureau of the Census. 1994. “The Urban and Rural Classifications.” In Geographic Areas Reference Manual. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/GARM/Ch12GARM.pdf.

- Cabrera, Yvette. 2006. “Laguna’s Job Center Perceived as Positive; Without a Day Labor Site, Workers Could be Forced to Search for Work on the Streets of Laguna Beach.” The Orange County Register. July 13, 2006. LexisNexis Academic.

- Crotty, Sean M. 2015. “Locating Day-Labor Employment: Toward a Geographic Understanding of day-Labor Hiring Site Locations in the San Diego Metropolitan Area.” Urban Geography 36 (7): 993–1017.

- Crotty, Sean M. 2017. “Can the Informal Economy be ‘Managed’?: Comparing Approaches and Effectiveness of Day-Labor Management Policies in the San Diego Metropolitan Area.” Growth and Change 48 (4): 909–941.

- Daamen, Renée, and Jeroen Doomernik. 2014. “Local Solutions for Federal Problems: Immigrant Incorporation in Montgomery County, Maryland.” Urban Geography 35 (4): 550–566.

- de Graauw, Els, Shannon Gleeson, and Irene Bloemraad. 2013. “Funding Immigrant Organizations: Suburban Free Riding and Local Civic Presence.” American Journal of Sociology 119 (1): 75–130.

- Giugni, Marco, Ruud Koopmans, Florence Passy, and Paul Statham. 2005. “Institutional and Discursive Opportunities for Extreme-Right Mobilization in Five Countries.” Mobilization: An International Journal 10 (1): 145–162.

- Gnes, Davide, and Floris Vermeulen. 2018. “Legitimacy as the Basis for Organizational Development of Voluntary Organizations.” In Handbook of Community Movements and Local Organizations in the 21st Century, edited by Ram A. Cnaan and Carl Milofsky, 189–209. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Gnes, Davide, and Floris Vermeulen. 2019. “Non-governmental Organisations and Legitimacy: Authority, Power and Resources.” Journal of Migration History 5 (2): 218–247.

- Hagen, Lutz M. 1993. “Opportune Witnesses: An Analysis of Balance in the Selection of Sources and Arguments in the Leading German Newspapers’ Coverage of the Census Issue.” European Journal of Communication 8 (3): 317–343.

- Hanlon, Bernadette, and Thomas J. Vicino. 2015. “Local Immigration Legislation in two Suburbs: an Examination of Immigration Policies in Farmers Branch, Texas, AndvCarpentersville, Illinois.” In The new American Suburb: Poverty, Race and the Economic Crisis, edited by Katrin B. Anacker, 133–150. London: Routledge.

- Helbling, Marc, and Anke Tresch. 2011. “Measuring Party Positions and Issue Salience From Media Coverage: Discussing and Cross-Validating new Indicators.” Electoral Studies 30 (1): 174–183.

- Hopkins, Daniel J. 2010. “Politicized Places: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 40–60.

- Huang, Xi, and Cathy Yang Liu. 2018. “Welcoming Cities: Immigration Policy at the Local Government Level.” Urban Affairs Review 54 (1): 3–32.

- Ignatin, Heather, and Amy Taxin. 2006. “Rent on Day-Labor Site Unknown; Caltrans says the Cost to Laguna Beach for its Lease may take 60 Days to Determine.” The Orange County Register. July 13, 2006. LexisNexis Academic.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Paul Statham. 1999. “Political Claims Analysis: Integrating Protest Event and Political Discourse Approaches.” Mobilization: An International Journal 4 (1): 203–221.

- Lal, Prerna. 2013. “You Cannot Live Here – Restrictive Housing Ordinances as the New Jim Crow.” SSRN. June 1, 2013.

- Martinez, Brian. 2005. “Job Center of Debate; Costa Mesa Job Center, Slated for Closure, doesn’t Fit with Plan to Spruce up the Westside, Councilman says.” The Orange County Register. March 20, 2005. LexisNexis Academic.

- Morello, Carol. 2005. “Frustration, Fear Intersect at Laborers’ Site; Herndon Wrestles with New Location for Day Workers.” The Washington Post. July 31, 2005. LexisNexis Academic.

- Newman, Benjamin J. 2013. “Acculturating Contexts and Anglo Opposition to Immigration in the U.S.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 374–390.

- Nicholls, Walter. 2019. The Immigrant Rights Movement: The Battle Over National Citizenship. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- Okamoto, Dina, and Kim Ebert. 2010. “Beyond the Ballot: Immigrant Collective Action in Gateways and new Destinations in the United States.” Social Problems 57 (4): 529–558.

- Provine, Doris Marie, Monica W. Varsanyi, Paul G. Lewis, and Scott H. Decker. 2016. Policing Immigrants: Local law Enforcement on the Front Lines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ramakrishnan, S. Karthick, and Tom Tak Wong. 2010. “Partisanship, not Spanish: Explaining Municipal Ordinances Affecting Undocumented Immigrants.” In Taking Local Control: Immigration Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States, edited by Monica Varsanyi, 73–96. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Steil, Justin P., and Ion B. Vasi. 2014. “The new Immigration Contestation: Social Movements and Local Immigration Policy Making in the United States, 2000-2011.” American Journal of Sociology 119 (4): 1104–1155.

- Trejos, Nancy. 2005. “Despite Funding, Doubts Persist on Day-Labor Center; Gaithersburg Location Still Undecided.” The Washington Post. October 27, 2005. LexisNexis Academic.

- Varsanyi, Monica W. 2008. “Immigration Policing Through the Backdoor: City Ordinances, the ‘Right to the City,’ and the Exclusion of Undocumented day Laborers.” Urban Geography 29 (1): 29–52.

- Varsanyi, Monica W. 2010. Taking Local Control. Immigration Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Visser, M. Anne, and Sheryl-Ann Simpson. 2019. “Determinants of County Migrant Regularization Policymaking in the United States: Understanding Temporal and Spatial Realities.” Economy and Space 51 (1): 91–111.

- Visser, Anne, Nik Theodore, Edwin J. Melendez, and Abel Valenzuela Jr. 2017. “From Economic Integration to Socioeconomic Inclusion: day Labor Worker Centers as Social Intermediaries.” Urban Geography 38 (2): 243–265.

- Walker, Kyle E. 2014. “Immigration, Local Policy, and National Identity in the Suburban United States.” Urban Geography 35 (4): 508–529.

- Walker, Kyle E. 2018. “Locating Neighborhood Diversity in the American Metropolis.” Urban Studies 55 (1): 116–132.

- Walker, Kyle E., and Helga Leitner. 2011. “The Variegated Landscape of Local Immigration Policies in the United States.” Urban Geography 32 (2): 156–178.

- Walker, Edward, and John D. McCarthy. 2010. “Legitimacy, Strategy, and Resources in the Survival of Community-Based Organizations.” Social Problems 57 (3): 315–340.

- Wells, Miriam J. 2004. “The Grassroots Reconfiguration of U.S. Immigration Policy.” International Migration Review 38 (4): 1308–1347.

- Wisckol, Martin, Erika Ritchie, Amy Taxin, and Peggy Lowe. 2006. “State: Labor Center Violates the Law; Caltrans Orders it Closed in Laguna after a Minuteman Member Cites Lack of Proper Permits.” The Orange County Register. July 1, 2006. LexisNexis Academic.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2009. “Critical Theory and ‘Gray Space’: Mobilization of the Colonized.” City 13 (2-3): 246–263.