?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to widespread worries that the health crisis is resulting in generalized hostility towards minorities and reduced support for a diverse society. Relying on a large survey of diversity attitudes in Germany fielded before and during the pandemic, we employ a quasi-experimental design to evaluate whether such a trend has occurred among the general public. Past work suggests two competing expectations – one anticipating a rise in hostility grounded in threat theories, and one anticipating stability grounded in public opinion research and theories of longer-term value change. Empirical results reveal generally high assent to socio-demographic diversity and minority accommodation, and remarkable stability during the pandemic period. Additionally, survey vignettes show strong and equally stable anti-discrimination norms that are inclusive of Asian-origin populations. Overall, results suggest that surges in racist incidents during the pandemic do not reflect analogous surges in hostility within the population at large.

Has the Coronavirus pandemic “unleash[ed] a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering” as the United Nations General Secretary warned in May 2020 (UN Citation2020)? In Germany, as in many other countries, public authorities and media have noted an increase in hate-based incidents and racist attacks targeting, among others, persons perceived as Asian as the alleged spreaders of the virus (Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes Citation2020). Such worry for increasing hostility also exists for other minority groups. For instance, the Commissioner for Human Rights at the Council of Europe has expressed concern for the increasingly hostile climate towards LGBT persons (Council of Europe Citation2020). Are we witnessing a more general shift towards ethnic exclusionism and hostility towards minorities? Has the pandemic led to reduced public support for societal diversity?

This article presents evidence from a large survey in German cities, fielded before and during the pandemic (Drouhot et al. Citationforthcoming).Footnote1 The timing of our survey allows us to employ a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effect of the pandemic on attitudes towards and support for diversity in one of Europe’s foremost countries of immigration. Our results show generally high assent to socio-demographic diversity and minority accommodation, and remarkable stability of such assent during the pandemic period. Additionally, survey vignettes suggest strong and equally stable anti-discrimination norms that are inclusive of Asian-origin populations, before and during the Coronavirus outbreak. In spite of an increased number of racist incidents during the pandemic period, our results suggest it is unlikely that public opinion towards diversity as well as ethnic and other minorities significantly changed as a result of the Covid-19 outbreak.

Two competing theoretical expectations

While there exists little work on the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic yet, past social science research suggests two opposite expectations for its effects on attitudes towards socio-cultural heterogeneity and minority groups.

The influence of perceived group threat on prejudice has been firmly established by past scholarship in social psychology (see Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Citation2006 for a review and meta-analysis). In addition, and building on Blumer’s (Citation1958) work emphasizing the significance of large-scale collective events, social scientists have examined the influence of shocks like terror attacks (Bar-Tal and Labin Citation2001; Legewie Citation2013), but also sudden financial downturns (Becker, Wagner, and Christ Citation2011) on hostility towards specific outgroups. “In times of crises”, Becker, Wagner, and Christ (Citation2011, 881) suggest, “people deal with this unspecific threat by attributing the cause of the crisis to certain scapegoats in order to reduce uncertainty and to rebuild control”. Scapegoating thus occurs when individuals feel threatened and engage in “causal attribution” (Hewstone Citation1989) of the negative consequences of such events to certain groups.

A global disease outbreak may be particularly prone to triggering generalized hostility: evolutionary perspectives within political science and social psychology emphasize the central role of the fear of diseases in shaping xenophobia and activating latent prejudice (Aarøe, Petersen, and Arceneaux Citation2017). They go beyond specific attribution and expect risk-averse, and affect-based responses to perceived health threats to produce generalized prejudice against all minority groups. Extending these approaches to the current health crisis, one might assume that confidence in the benefits of a socio-culturally heterogeneous society will deteriorate and appeals for cohesion through homogeneity (including racist and xenophobic sentiments) will increase.

An alternative theoretical narrative suggests that support for socio-cultural diversity and respect for minority rights will remain stable in the current crisis. Public opinion research shows immigration and other political attitudes among adults are remarkably constant over the life course (Kiley and Vaisey Citation2020; Kustov, Laaker, and Reller Citationforthcoming; Dennison and Geddes Citation2018, Citation2020). In Germany, pre-pandemic, “baseline” diversity attitudes are decidedly positive: past work shows that diversity and the presence of minorities has become an ordinary and much appreciated part of urban life (Schönwälder et al. Citation2015). Such pro-diversity attitudes are founded in a high valuation of individual freedoms, minority rights and cosmopolitanism (Norris and Inglehart Citation2019, 33), and are tangible in the strong social norms against prejudice and discrimination now existing in many European countries (Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten Citation2013, 842). Together, this evidence suggests major attitudinal changes as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic are unlikely.

Data and empirical strategy

To evaluate these competing theoretical expectations, we exploit temporal variation in the fielding of a large-scale survey on diversity attitudes in twenty German cities between November 2019 and April 2020. The survey includes measurement of attitudes towards socio-cultural heterogeneity, experiences of diversity in everyday life, as well as measurement of anti-discrimination norms through a set of vignette questions among other themes. It was administered by telephone on a random sample of 2,917 respondents in twenty German cities.

The administration of the survey occurred in two distinct phases – one between 18 November 2019 and 21 January 2020 (2,135 respondents) and a second between 3 March and 29 April 2020 (782 respondents). We exploit this exogenous variation to formulate a quasi-experimental design where the survey periods correspond to an experiment’s control and treatment groups.

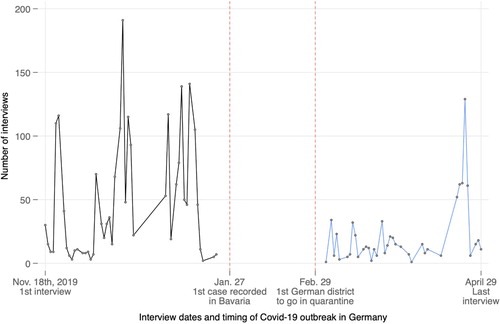

shows the time periods when the survey was conducted. The gap between the two survey periods, and the recording of the first cases of Covid-19 infections in between, creates natural control and treatment groups without ambiguity regarding a strict cut-off point. The Coronavirus gained ground on German soil in that period, and up to the first closing of schools, and all public life in one west German district in late February.

Figure 1. Illustration of control (left, interview completed earlier than January 27th, 2020) and treatment (right, interview completed later than February 29th, 2020) groups around the start of the pandemic in Germany.

Our identification strategy of the causal effect of Covid-19 on diversity attitudes rests on two critical assumptions (for an analogous approach, see Legewie Citation2013). First, compositional differences between the treatment and control groups should be non-existent or along dimensions that can be statistically adjusted for. For instance, older respondents tend be more easily reachable by phone if they are retired and more often at home. Conversely, immigrants are typically harder to reach. This so-called reachability bias can create imbalance between control and treatment groups, and confound results if groups whose diversity attitudes differ are more systematically present in the control group or vice versa.

We control for well-known predictors that influence respondents’ reachability, namely age, employment status and migration background. Second, our approach builds on an assumption of temporal stability – namely, that diversity attitudes would not have changed in the absence of the treatment. This assumption guarantees that the measured effect of the treatment is not confounded with a time-varying variable that is causally prior to the treatment – for instance, if diversity attitudes were affected by bad weather and seasonal change, which co-occur with the survey periods in our design. Given this is highly implausible and that there exist no other time-varying confounders to our knowledge, we consider that our design meets this assumption.

Hence, we estimate the average causal effect of the Covid-19 period with regression models controlling for demographic composition across experimental groups and a dummy variable for the treatment status. Formally:

(1)

(1) In regression Equation (1), we model a diversity outcome y as a function of treatment T – yielding the coefficient θ, the mean difference in y conditional on a set of covariates X – in our case age, sex, whether or not the respondent holds a job, educational attainment, city of residence, migration background and far right voting for respondent i. θ can be interpreted causally if the temporal stability assumption holds, and if no variable creating a reachability bias is omitted from X. Corresponding coefficients β are not of direct substantive interest, and are not reported on in detail. We dichotomize all outcome variables for comparability across itemsFootnote2 and express all results for θ as marginal effects (Mood Citation2010). A table describing the demographic and social composition of our sample is available in .

We present our results in two distinct steps. First, we model variation in responses to six questions measuring attitudes to diversity and minority rights (for details see Appendix B). We report results for questions on:

Whether Germany’s cultural life is enriched by immigrants,

Whether young people benefit from contact with others of different origin or religious belief,

Whether Muslims living in Germany should have the right to build mosques, even in the respondent’s neighbourhood,

Whether the media should report less about discrimination,

If too much is being done to meet the specific needs of gays and lesbians or of refugees.

In a second step, we analyse responses to vignette questions measuring the strength of anti-discrimination norms. Each question features a fictitious scenario where a third-party protagonist engages in openly stigmatizing discourse, and in which we randomly manipulate the group being targeted – with one such group being “Asian”. Given the reporting of specific increase in anti-Asian stigma as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, we focus on the vignettes involving hostility towards Asian-origin populations. The number of individuals who received the “Asian” condition when answering vignette questions varies between 264 and 336 across the four vignettes. Here is the wording in one of them:

Imagine you are attending a family reunion. You sit together, it’s nice, the family is enjoying the party. At some point, the conversation turns to politics and you hear a relative say: “I think the main problem is that we have too many Asians in the country. We’d all be better off if this was not the case”.

The three other vignettes are based on scenarios involving a conversation with a neighbour, a supermarket cashier, and a person in a waiting room – in each case complaining about an Asian couple present in the interaction (for details see Appendix B). Each vignette was followed by two questions on whether or not the respondent would be bothered by the behaviour he or she witnessed, and what course of action he or she would take – e.g. do nothing, informally signify disagreement, voice a different opinion, and sharply protest. We use responses to these vignettes to study the effect of the pandemic period on the social legitimacy of discrimination against Asian-origin populations.Footnote3

While the temporal variation in the fielding of our survey affords us a unique research opportunity to gauge the effect of the pandemic, we nevertheless acknowledge that our questionnaire was not designed to directly measure perceptions of threat. Rather, we consider changes in diversity attitudes and toward the legitimacy of discrimination against Asian-origin populations to reflect the extent to which scapegoating occurred – that is, how much societal diversity and specifically people of Asian origin were held responsible for the spread of the virus. Likewise, while our vignettes do not directly measure intergroup threat, it is reasonable to expect that the latter would be associated with an increase in the perceived legitimacy of discrimination against Asian-origin populations.

Results I: attitudes towards diversity and minority groups

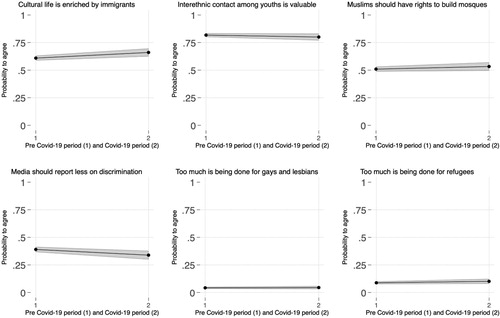

shows the estimated causal effect of the pandemic period on responses to questions probing attitudes towards diversity.Footnote4 Overall, we find that the Covid-19 period has had little effect on diversity attitudes among respondents in our survey. This is readily visible in the overlapping confidence intervals between each predicted value, and the quasi-straight lines connecting each predicted value for illustration. If anything, being interviewed during the pandemic has a slightly positive effect on the evaluation of cultural enrichment brought about by immigration, and a slightly negative effect on the probability to agree with the statement that the media should report less on discrimination. In contrast to threat theory and other work emphasizing the influence of fear of disease on hostility towards minority groups, we find that urban dwellers in Germany are generally supportive of diversity – both before and during the pandemic period.

Figure 2. Estimated causal effect of Covid-19 period on diversity attitudes (grey areas are 95 per cent confidence intervals).

Notes: shows change in predicted probabilities for response to questions on diversity among respondents who answered the survey in the control (pre-Covid 19) and the treatment (during Covid-19) groups. Underlying models include controls for age, gender, professional status, migration background, educational attainment, far-right voting, and city of residence – all held at mean/representative values.

A majority of respondents agrees that Germany’s cultural life is enriched by immigrant newcomers, that contact between youths of different origins and religions is generally good, and that Muslims residing in Germany should have the right to build mosques, even in the respondent’s neighbourhood. Conversely, only a minority of respondents think that the media should report less on discrimination, and an even far smaller minority thinks that too much is being done for gays and lesbians as well as refugees. Supplementary analyses show similar patterns of stability and high support for diversity across nine other items measuring analogous issues – for instance on parliamentary representation of disadvantaged groups or teaching about all religions in schools.Footnote5

Results II: social legitimacy of discrimination against Asian-origin populations during the pandemic period

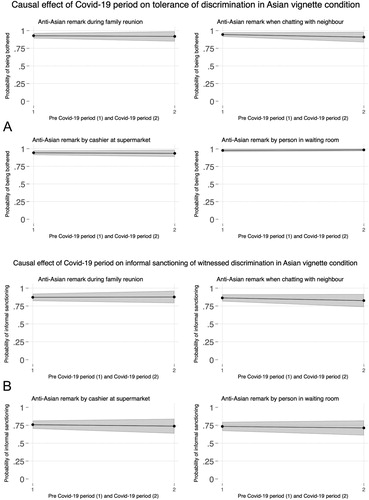

shows the estimated causal effect of the pandemic period on the propensity to be bothered by discrimination events against Asian-origin populations (Panel A), as well as the propensity to engage in informal sanctioning (voicing a different opinion, sharply protesting) when witnessing such events (Panel B). Respondents declare they would be bothered if witnessing a discrimination event against Asians at very high rates – over 90 per cent across all 4 vignettes. Rates of informal sanctioning are also high, hovering between 70 per cent and 87 per cent – with lower intervention rates in scenarios involving interaction with strangers compared to familiar others.

Figure 3. Estimated causal effect of Covid-19 period on antidiscrimination norms in vignette questions involving discrimination events against Asian-origin populations.

Notes: shows change in predicted probabilities for response to vignette questions on reaction (Panel A) and favoured behavioural response (Panel B) to discrimination event against Asian-origin populations in the control (pre-Covid 19) and the treatment (during Covid-19) groups. Underlying models include controls for age, gender, professional status, migration background, educational attainment, and far-right voting – all held at mean/representative values.

Importantly, we observe no change in the pandemic period in responses to our vignette questions designed to measure antidiscrimination norms against Asian-origin populations. Both before and during the pandemic, respondents perceive discriminatory behaviour against Asians as socially illegitimate. We observe no relaxation of such social norms in the pandemic period where one might have anticipated a normalization of hostility against Asians due to their perceived association with the Coronavirus. Rather, intervention rates to sanction witnessed discrimination in our fictitious scenarios remain high. Asian-origin populations are included in social norms against the expression of prejudice, even during a major health crisis in which hate crimes and hostile behaviour against Asians have been increasing.

Supplementary analyses

We re-ran all analyses based on a cut-off date set at March 19th – after German chancellor Merkel gave a solemn speech on the gravity of the health situation in Germany – for the definition of experimental groups. In other analyses, we added interaction effects for far-right voting and migration background with interview periods, in case the former significantly depended on the latter. We also replicated the analyses restricting our analytical sample to those without a migration background, those with less than a high school education, and those located in East Germany in case an effect was only present among this subset of respondents, and possibly lost in the pooled sample approach we took. Finally, we attempted to identify a temporally heterogeneous treatment effect by interacting experimental groups with interview days, as well as interview months. In all these supplementary analyses, the results we obtained were substantively identical to the ones above pointing to a null effect. We refrain from presenting these results due to space constraints but they are available from us upon request.

Conclusion

Has the Covid-19 pandemic undermined public support for a diverse society? Earlier in this article, we noted two theoretical expectations regarding attitudes towards minorities in times of societal crisis. Group threat theory and work emphasizing the fear of diseases suggest that negative attitudes will intensify under conditions in which health and well-being are deemed to be threatened. Meanwhile, past work in public opinion research and theories of longer-term value change suggest that diversity attitudes should remain stable despite this external threat. Our findings clearly support the latter proposition. Employing a quasi-experimental design and exploiting temporal variation in the fielding of a large survey on diversity attitudes, we find that the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic has not lowered the high level of assent to diversity in urban Germany.

What explains the null effect we document? Our study is descriptive, and we can only speculate on the causal processes behind our findings. For instance, it is possible that financial support and intervention from the government helped mitigate feelings of threat due to the pandemic. Likewise, repeated appeals to solidarity made by prominent political leaders may have dampened the backlash expected under the group threat narrative and mitigated causal attributions of the health crisis to particular groups. Future research should investigate the processes underlying the non-effect of the pandemic on diversity attitudes.

In closing, we wish to emphasize that these results do not negate the existence of significant discrimination against different minorities in Germany (Scherr, El-Mafaalani, and Yüksel Citation2017). Anti-minority violence and acts of outward discrimination during the pandemic period and at other times constitute a severe problem. And yet, we contend that surges in hate crime should not be equated with a more general shift in public opinion. Indeed, positive attitudes towards diversity among the general urban population documented in earlier work (e.g. Schönwälder et al. Citation2015) appear to be resilient to this societal crisis. Diversity assent may well be a valuable public good helping heterogeneous societies face significant collective challenges.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (190.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Mauricio Bucca, Matthias König, Mario Molina, Benjamin F. Rosche and members of audience at the Sociology Colloquium at the University of Göttingen for helpful comments and criticisms on an earlier version of this article, as well as Margherita Cusmano for helpful research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The dataset will be made available through the GESIS data archive.

2 Supplementary analyses (not shown) using the items’ original scales yield identical results.

3 Due to the lower number of observations as the “Asian” condition was one of ten other conditions, we do not include the respondent’s city of residence to avoid estimation issues when computing predicted values.

4 The underlying logistic regression models produce log odds, which should be kept as such for the precise estimation of the causal effect. However, here, for ease of interpretation we express the results in probabilities, which remain substantively identical to log odds in their expressing of a non-effect.

5 We omit these results here due to space constraints but they are available from the authors upon request.

6 We used 7 as a cutoff to make our measurement more conservative. Setting the cutoff at 5 or 6 yields substantively identical results, however.

References

- Aarøe, Lene, Michael Bang Petersen, and Kevin Arceneaux. 2017. “The Behavioral Immune System Shapes Political Intuitions: Why and How Individual Differences in Disgust Sensitivity Underlie Opposition to Immigration.” American Political Science Review 111 (2): 277–294.

- Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes. 2020. Diskriminierungserfahrungen im Zusammenhang mit der Corona-Krise. Berlin: Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes.

- Bar-Tal, Daniel, and Daniela Labin. 2001. “The Effect of a Major Event on Stereotyping: Terrorist Attacks in Israel and Israeli Adolescents’ Perceptions of Palestinians, Jordanians and Arabs.” European Journal of Social Psychology 31: 265–280.

- Becker, Julia C., Ulrich Wagner, and Oliver Christ. 2011. “Consequences of the 2008 Financial Crisis for Intergroup Relations: The Role of Perceived Threat and Causal Attributions.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 14 (6): 871–885.

- Blinder, Scott, Robert Ford, and Elisabeth Ivarsflaten. 2013. “The Better Angels of Our Nature: How the Antiprejudice Norm Affects Policy and Party Preferences in Great Britain and Germany.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (4): 841–857.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7.

- Council of Europe. 2020. “COVID-19: The Suffering and Resilience of LGBT Persons Must Be Visible and Inform the Actions of States.” https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/covid-19-the-suffering-and-resilience-of-lgbt-persons-must-be-visible-and-inform-the-actions-of-states (consulted July 10th, 2020).

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes. 2018. “A Rising Tide? The Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti-Immigration Political Parties in Western Europe.” The Political Quarterly 90: 107–116.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes. 2020. “Why Covid-19 Does Not Necessarily Mean That Attitudes Towards Immigration Will Become More Negative.” https://hdl.handle.net/1814/68055 (consulted September 10th, 2020).

- Drouhot, Lucas G., Sören Petermann, Karen Schönwälder, and Steven Vertovec. forthcoming. “The ‘Diversity Assent’ (DivA) Survey – Technical Report.” Göttingen: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.

- Hewstone, Miles. 1989. Causal Attribution: From Cognitive Processes to Collective Beliefs. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Kiley, Kevin, and Stephen Vaisey. 2020. “Measuring Stability and Change in Personal Culture Using Panel Data.” American Sociological Review 85 (3): 477–506.

- Kustov, Alexander, Dillon Laaker, and Cassidy Reller. forthcoming. “The Stability of Immigration Attitudes: Evidence and Implications.” Journal of Politics.

- Legewie, Joscha. 2013. “Terrorist Events and Attitudes Toward Immigrants: A Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (5): 1199–1245.

- Mood, Carina. 2010. “Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do about It.” European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Riek, Blake M., Eric W. Mania, and Samuel L. Gaertner. 2006. “Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 10 (4): 336–353.

- Scherr, Albert, Aladin El-Mafaalani, and Gökçen Yüksel, eds. 2017. Handbuch Diskriminierung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Schönwälder, Karen, Sören Petermann, Jörg Hüttermann, Steven Vertovec, Miles Hewstone, Dietlind Stolle, Katharina Schmid, and Thomas Schmitt. 2015. Diversity and Contact: Immigration and Social Interaction in German Cities. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- United Nations. 2020. Press Release on 8 May: Secretary-General Denounces ‘Tsunami’ of Xenophobia Unleashed Amid COVID-19, Calling for All-Out Effort Against Hate Speech, www.un.org/press/en/2020/sgsm20076.doc.htm (consulted July 10th, 2020).

Appendices

Appendix A. Descriptive statistics and balance between experimental groups

Table A1. Covariate balance between treatment and control groups.

contains frequencies for covariates included in regression models underlying and . Following standard expectation of reachability bias in survey research, covariate imbalances are visible between experimental groups in terms of proportion of respondents with a migration background, age structure, professional status, and city of residence. Statistical differences between experimental groups along these lines are confirmed in a logistic model predicting membership in the treatment group (not shown). Our statistical controls adjust for this variation in the regression equation. In fact, and somewhat remarkably, we find very little difference in attitudes when comparing the control and treatment groups without controls. The raw and adjusted results are very close.

The characteristics of our sample reflect our sampling strategy – we focused on twenty randomly selected cities in Germany and stratified city selection by size. Second, we aimed at a share of 25 per cent of respondents with a migration background (see Drouhot et al. Citationforthcoming for details).

Appendix B. Variable construction and survey instruments

For the first series of analysis, we constructed binary response variables, by coding responses of 7 and above as “1” for the cultural life question,Footnote6 and responses of “somewhat” and “fully” agree as “1” for questions regarding the building of mosques and interethnic contact. For the questions on discrimination report by the media, and too much being done for refugees / gays and lesbians, the answer lead to binary response variables by design. Finally, in the case of the vignette questions, we first created binary response variables reflecting the answer to whether or not the respondent would be bothered, and then created a binary response variable for informal sanctioning (whether the respondent would either voice a different opinion of protest sharply, versus choose non-confrontation for those who disapprove and any other option for those who approve of the third party’s discriminatory behaviour/discourse).

Below are the exact wordings for the survey questions our analyses focus on, in German (in italics) and in English.

Würden Sie sagen, dass das kulturelle Leben in Deutschland im Allgemeinen durch Zuwanderer UNTERGRABEN oder BEREICHERT wird?

Bitte sagen Sie mir auf einer Skala von 0–10, was Sie denken, wobei “0” bedeutet, dass das kulturelle Leben in Deutschland im Allgemeinen durch Zuwanderer UNTERGRABEN wird, und “10” bedeutet, dass das kulturelle Leben in Deutschland im Allgemeinen durch Zuwanderer BEREICHERT wird. Mit den Werten dazwischen können Sie Ihre Meinung abstufen.

Would you say that Germany’s cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries?

Please tell me on a scale of 0–10 what you think, where “0” means that cultural life in Germany is generally UNDERMINED by immigrants, and “10” means that cultural life in Germany is generally ENRICHED by immigrants. With the values in-between you can scale (gradate) your opinion.

Ich lese Ihnen jetzt einige Aussagen vor. Bitte geben Sie jeweils an, ob Sie zustimmen oder nicht zustimmen.

Die in Deutschland lebenden Muslime sollten das Recht haben, Moscheen zu bauen, auch in IHREM Wohnviertel.

Junge Leute profitieren davon, mit Gleichaltrigen anderer Herkunft oder anderen Glaubens in Kontakt zu sein.

I am now going to read you several statements. Please state whether you agree or disagree with each statement.

- The Muslims living in Germany should have the right to build mosques, including in your own neighbourhood.

- Young people profit from contact with other young people of different origin or religious belief.

Do you fully agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree or definitely disagree?

Nun eine Frage zu Fällen von Diskriminierung etwa von Homosexuellen oder dunkelhäutigen Menschen. Finden Sie:

Die Medien sollten EHER MEHR über Fälle von Diskriminierung berichten. ODER

Die Medien sollten EHER WENIGER über Fälle von Diskriminierung berichten.

Now a question on cases of discrimination, for example against homosexuals or dark-skinned people. Do you think:

the media should report MORE about cases of discrimination. OR

the media should report LESS about cases of discrimination.

In Deutschland wird Einiges getan, um den spezifischen Bedürfnissen einzelner Gruppen gerecht zu werden. Wie ist das bei Schwulen und Lesben [Flüchtlingen]?

Finden Sie, dass hier in Deutschland zu viel, genug oder zu wenig getan wird, um deren spezifischen Bedürfnissen gerecht zu werden?

In Germany, things are being done to meet the specific needs of individual groups. How about Gays and lesbians [Refugees]?

Do you find that here in Germany too much, enough or too little is being done to meet their specific needs?

Vignette questions:

Jetzt wir möchten Ihnen einige Situationen beschreiben, die in Ihrem Alltag auftreten können, und fragen, wie Sie reagieren würden.

Stellen Sie sich bitte einmal vor, Sie besuchen ein Familientreffen. Sie sitzen zusammen, es ist nett, die Familie genießt das Fest. Irgendwann kommt das Gespräch auf die Politik und Sie hören, wie jemand sagt: “Ich finde, das Hauptproblem ist, dass wir zu viele [Asians] im Land haben. Es würde uns allen besser gehen, wenn das nicht so wäre.”

Wie ist es mit Ihnen, würde Sie die Aussage des Verwandten stören?

Now we would like to describe some situations that may occur in your everyday life and ask you how you would react.

Imagine you are attending a family reunion. You sit together, it’s nice, the family is enjoying the party. At some point, the conversation turns to politics and you hear a relative say: “I think the main problem is that we have too many [Asians] in the country. We’d all be better off if this was not the case.”

How about you, would your relative’s statement bother you?

Stellen Sie sich bitte einmal vor, Sie stehen vor Ihrer Haustür und plaudern mit einem Nachbarn. Jemand von der Hausverwaltung kommt mit einem [Asian [couple]] Paar vorbei, um die freistehende Wohnung nebenan zu zeigen. Der Nachbar sagt zu Ihnen: “Mir würde es stinken, wenn wir solche Leute als Nachbarn bekommen würden.”

Wie ist es mit Ihnen, würde Sie der Kommentar des Nachbarn stören?

Imagine you are standing in front of your front door and chatting with a neighbour. Someone from the property management comes by with a [Asian [couple]] couple to show them the vacant apartment next door. The neighbour says to you: “I would be upset if we had such people as neighbours.”

What about you, would you be bothered by the neighbour’s comment?

Stellen Sie sich bitte einmal vor, Sie stehen im Supermarkt in der Schlange an der Kasse. Vor Ihnen in der Schlange ist ein [Asian [couple]] Paar. Das Paar braucht eine ganze Weile, um zu bezahlen und die Einkäufe einzupacken. Als sie weg sind und Sie selbst bezahlen, sagt der Kassierer: “Entschuldigen Sie, diese Sorte Leute halten immer den Betrieb auf”.

Wie ist es mit Ihnen, würde Sie die Aussage des Kassierers stören?

Imagine you are standing in the checkout-line at a supermarket. A [Asian [couple]] couple is in front of you in the queue. It takes the couple quite a while to pay and pack their groceries. When they are gone and you are paying, the cashier says: “Sorry about that, this kind of people always disturb the flow of business”.

How about you, would the cashier’s statement bother you?

Und nun stellen Sie sich bitte einmal vor, Sie sitzen in einem Wartezimmer. Es ist voll, mit Ihnen warten noch etwa 15 Personen. Als sie aufgerufen werden, steht ein [Asian [couple]] Paar auf und verläßt das Wartezimmer. Nachdem sie weg sind, sagt ein Mann laut: “Es ist eine Zumutung, dass man sich heute überall hinter solchen Leuten anstellen muss.”

Wie ist es mit Ihnen, würde Sie die Aussage des Mannes stören?

And now imagine that you are sitting in a waiting room. It’s full, there are about 15 people waiting with you. A [Asian [couple]] couple is called and leaves the waiting room. After the couple is gone, [A] a man/[B] a woman says loudly: “It’s unacceptable that everywhere you have to wait behind such people today”.

What about you, would you be bothered by the [A] man’s/[B] woman’s statement?

For each question, the options for chosen behavioural responses read as follows, depending if the respondent declares he/she would be bothered:

Filter: Wenn Ja

Und was würden Sie tun?

3. nichts,

4. Ihre Ablehnung z.B. durch einen bösen Blick oder Kopfschütteln signalisieren,

5. knapp sagen, dass Sie anderer Meinung sind.

6. scharf protestieren.

Filter: Wenn Nein

Und was würden Sie tun?

7. nichts,

8. Ihre Zustimmung z. B. durch Nicken signalisieren,

9. knapp sagen, dass Sie der gleichen Meinung sind,

10. deutlich bekräftigen, dass Sie zustimmen.

Filter: If Yes

And what would you do?

| 3. | nothing, | ||||

| 4. | signal your disagreement, for example with a nasty look or by shaking your head, | ||||

| 5. | briefly say that you are of a different opinion. | ||||

| 6. | protest sharply. | ||||

Filter: If No

And what would you do?

| 7. | nothing, | ||||

| 8. | signal your agreement, for example by nodding, | ||||

| 9. | say briefly that you are of the same opinion, | ||||

| 10. | clearly emphasize that you agree. | ||||

Works cited:

Drouhot, Lucas G., Sören Petermann, Karen Schönwälder, and Steven Vertovec. Citationforthcoming. “The “Diversity Assent” (DivA) Survey – Technical Report.” Göttingen: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.