ABSTRACT

We explore identity formation among adolescents, using the first wave of the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study in Norway (CILS-NOR). The results show that immigrant origin youth gradually adopt a stronger self-identity as Norwegians, regardless of regional origins and religious affiliation. However, while adolescents of European immigrant origin report that others see them as being even more “Norwegian” than they identify themselves, children of immigrants from Africa and Asia report that others see them as being far less “Norwegian” than how they identify themselves. Non-recognized national identity – the product of an asymmetrical relationship between self-identity and ascription – is most common among well-established minority groups, and we show that both ethno-racial origins and religious affiliation are major hurdles for acceptance. Ethnic identities associated with the parental homeland, which are closely related to religion, are more stable, and only very weakly related to the formation of a national identity.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

As nation states across the Western world are becoming increasingly diverse due to immigration, the question of who is part of the national community has come to the fore of public discourse. It is commonly argued that a shared sense of national identity – being part of what Benedict Anderson (Citation2006) called an “imagined community” where members feel emotionally tied to fellow citizens they have never met – is vital for the legitimacy, social cohesion and solidarity which underpins modern nation states. This is perhaps particularly true for egalitarian redistributive welfare states like the Scandinavian ones, as a shared national identity also implies economic and social obligations to fellow nationals which are not extended to outsiders (Miller Citation1995). However, as the demographic composition of nation states traditionally based on primordial ideas of common ancestry change, new non-ethnic conception of the nation is sorely needed, and national identity is currently undergoing a public reconstruction in many countries (Vassenden Citation2010). Yet the question remains as to what kind of identities will form the basis of such new “imagined communities” – and to what extent immigrants and their children will feel part of and be included into them.

Identity formation is an inherently relational and contested process, shaped by external categorization as well as internal self-identification (Jenkins Citation2008). If a national identity is to take form, people need to adopt and internalize a sense of self as belonging to a larger nationally defined social category. At the same time, they need to be accepted and recognized as part of that same social category by others. This duality is reflected in the public debates about immigration and national identity currently roiling most European countries, where politicians and commentators commonly question to which extent immigrants and their children will develop a commitment to their new society, while minority voices question if they will ever be accepted as part of the national community, or forever be labelled as outsiders.

Barriers for integration may arise both from within minority groups who wish to retain their distinctiveness as well as in exclusion by the majority, and different immigrant groups are not equally positioned to overcome them. In the US literature, race and class have traditionally been constructed as the major boundary defining group membership. The canonical literature on immigrant assimilation was predominantly concerned with how European immigrants gradually came to identify and be identified as (white) Americans (Gordon Citation1964; Warner and Srole Citation1945). A major point of contestation for today’s immigration scholars in the US is the extent to which this path will be open to the children of today’s mostly non-white immigrants from Asia, Latin-America and the Caribbean. Some argue that although a replication of the massive boundary shift of the past seems out of reach, a path to assimilation will still be open to the children of a majority of today’s immigrants (Alba Citation2014; Alba, Beck, and Basaran Sahin Citation2018). Other take a more pessimistic view, arguing that this path will most likely be blocked for children of many poor non-white immigrants, due to racial barriers and an increasingly polarized class structure, and that they in turn are more likely to reject the values and identities of the majority (Haller, Portes, and Lynch Citation2011; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001; Portes, Fernandez-Kelly, and Haller Citation2005; Rumbaut Citation1994; Rumbaut Citation2008). Similar concerns are commonly voiced in Europe (Çelik Citation2015; Diehl and Schnell Citation2006; Koopmans Citation2015), although here, the major hurdle for integration is more often thought to be religion, with Islam described as a “bright boundary marker” in today’s Europe (Alba Citation2005; Alba and Foner Citation2015; Drouhot and Nee Citation2019).

This article will focus on three different dimensions of identity among young people with an immigrant background in Norway’s increasingly diverse capital region: We primarily focus on the relationship between adolescents’ national self-identity as being “Norwegian” on the one hand, and their ascribed identity in terms of being seen by others as “Norwegian” on the other. In addition, we investigate ethnic self-identity in terms of the importance they place on maintaining the culture and traditions of their parents’ country of origin. We will compare outcomes across immigrant generations in order to indicate change, as well as immigration origin, socioeconomic status and religious affiliation in order to identify barriers to identity formation. Three overall research questions will be addressed:

Are there generational differences among immigrant origin youth in Norway – as a measure of social change – in the extent to which they self-identify as Norwegians; in the extent to which they feel accepted as Norwegians by others; and in the extent to which they identify with the nationality of their parents’ country of birth?

Are patterns of identity formation in terms of self-identity vs ascription and national vs ethnic identification congruent or non-congruent for different immigrant origin groups?

To what extent does ethno-racial origin, class and religious background shape identity formation among minority youth in Norway?

Theoretical perspectives and previous research

What do we refer to when asking whether someone is “Norwegian”? With rapidly increasing ethnic, cultural and religious diversity due to high levels of immigration over the past few decades, the answer to this question seem far less straight forward than it did in the past. In public discourse, the concept of “ethnic Norwegian” is commonly referred to as something distinct from citizenship, and the racial connotations of the word is a constant source of controversy. As Brubaker (Citation2009) has forcefully argued, ethnicity, race, and nationalism are not distinct phenomena, but overlapping forms of cultural meaning, social organization and political contestation. As objects of social scientific study, they vary in terms of criteria and indicia of membership, the sharpness/fuzziness of their boundaries, the level of hierarchy, markedness and stigma associated with membership, the social salience of their boundaries, and the territorial concentration of the groups they refer to, etc. (Brubaker Citation2009).

Fredrik Barth famously argued that ethnicity is not (only) defined by immutable bundles of cultural traits, but situationally defined, produced and reproduced through interactions at or across boundaries, thereby drawing the focus of analysis towards the boundaries themselves rather than the “cultural stuff” contained inside them (Barth Citation1969). Such interactions at or across boundaries are of two basic kinds (Jenkins Citation2008). On the one hand, members of a group signal to others who they are through processes of self-definition. On the other, people are categorized by others through processes of external ascription. This process of external attribution may be consensual, as a validation of the others’ internal definition(s), or it may represent characterizations which the categorized themselves do not recognize. Power is therefore an important dimension in identity formation, since the capacity to successfully define others in ways that affect their lives implies a certain level of power or authority (Jenkins Citation2008). The level of congruence or non-congruence between internal self-identification and external ascription in this ongoing dialectic is therefore particularly relevant when studying asymmetrical relationships, as the one between immigrant minorities and majority populations in host countries.

While ethnicity, race, and nationhood may be overlapping forms of social differentiation, national identity is distinct in the sense that it forms the basis for the legitimacy of modern nation states. Scholars famously distinguish between the territorial basis of the French citizenry and the German emphasis on biological descent, representing the civic and ethnic routes to nationhood (Brubaker Citation1992; Smith Citation1991; Smith Citation1995). Norwegian national identity is commonly thought to include a mixture of these elements. Vassenden (Citation2010) distinguishes between four different aspects of “Norwegianness” in everyday discourse, including the civic (citizenship), the cultural (e.g. Barths “cultural stuff”), ethnicity (Barths “boundaries”) and “whiteness” (race). He argues that everyday notions of the national are most fruitfully studied as a discursive space constituted by multiple overlapping, but sometimes mutually contradicting, oppositions (Vassenden Citation2010, Citation2011).

Finally, ethnic, national and racial categories and identities are malleable and dynamic. This is of course also the core premise in the literature on immigrant assimilation. In broad terms, two different outcomes regarding changes in minority identification over time can be derived from this literature. According to one line of reasoning, one may expect a convergence of identities between the minority and the majority over time and across generations, as minority identification gives way to majority identification. Classical assimilation theory argues that as immigrants and their descendants become more integrated into the host country’s mainstream culture and institutions, they will gradually show less distinctiveness in terms of language use, cultural orientation, intermarriage patterns, etc., and thus gradually adopt an identity as nationals (Gordon Citation1964; Warner and Srole Citation1945). More recent versions of assimilation theory stress how this process is accompanied by the “remaking” of identities among the majority as well, as elements from the minority are incorporated into the definition of what constitutes the mainstream (Alba and Nee Citation2009). The speed with which the assimilation process unfolds may differ for different immigrant groups depending on the cultural and economic resources they bring, as well as the barriers they face in the host country. Yet over time, both classical and contemporary assimilation theory presumes that the overall direction and mechanisms apply broadly to most immigrant groups. Several studies show that the overall pattern is that the so-called second generation in Europe do adopt a stronger national identity (Beauchemin, Hamel, and Simon Citation2018; Portes, Aparicio, and Haller Citation2016). In both classical and neo-assimilation theory, national identity formation is closely related to the accumulation of cultural and economic capital and upward social mobility through the educational system. There is today a bourgeoning literature describing how children of immigrants often hold high educational ambitions despite structural disadvantage – often referred to as immigrant optimism (Kao and Tienda Citation1995) or the immigrant drive (Drouhot and Nee Citation2019; Jackson, Jonsson, and Rudolphi Citation2012; Keller and Tillman Citation2008) – and following the assimilation literature we should expect that the degree to which children of immigrants adopt a national identity is closely related to their level of success in the educational system.

Other perspectives, however, argue that we may observe a continuation or even intensification or revival of minority ethnic identities in the second generation – at least among some immigrant groups. According to segmented assimilation theory, for example, the path to assimilation is for some of today’s non-European immigrants to the US, blocked by entrenched racial hierarchies and an increasingly polarized class structure (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001; Portes and Zhou Citation1993). Some of the new immigrants may have the resources to reach middle-class status and become accepted as Americans within a generation, but non-white immigrants who face discrimination and structural barriers with limited resources to confront them are more likely to stagnate in the marginal working class, or even face the risk of “downward assimilation”. This would be accompanied by reactive or oppositional identities, whereby the second generation in particular would reject the majority culture and identity (Haller, Portes, and Lynch Citation2011; Portes and Fernández-Kelly Citation2008; Portes, Fernandez-Kelly, and Haller Citation2005; Rumbaut Citation2008).

The traditional account of assimilation was a gradual and symmetric movement away from an ethnic identity based on identification with the country of origin and towards identifying more with the host country (Gordon Citation1964). However, more recent contributions argue that the two processes are not necessarily symmetrical, and that ethnic identification and host country identification may develop independently from each other (Berry Citation2005; Nandi and Platt Citation2015; Platt Citation2014; Van De Vijver and Phalet Citation2004). For example, Beauchemin, Hamel, and Simon (Citation2018), drawing on a large scale survey from France, show that even though descendants of immigrants gradually adopt an identity as being French, the salience of their ethnic origin for their personal identity remains or even increases for the children of immigrants (Beauchemin, Hamel, and Simon Citation2018). Ethnic identities may be constructed as a continuation of transnational identities linked to the home country, or as reactive identities developed in response to discrimination, exclusion and a hostile context of reception. In the US, proponents of segmented assimilation theory have argued that disadvantaged minority youth may reject an identity as Americans, instead adopting “oppositional” or “reactive” ethno-racial identities derived from the existing US racial hierarchy (Haller, Portes, and Lynch Citation2011; Portes and Rivas Citation2011; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001; Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Portes, Fernandez-Kelly, and Haller Citation2005; Rumbaut Citation2008). The concept of selective acculturation suggests that for the children of resource-poor immigrants who face large obstacles to integration in the form of discrimination and hostility it may be beneficial to retain some parts of the parents’ home country identity (Friberg Citation2019; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001). While both selective acculturation and reactive ethnicity involve ethnic identities distinct from the majority, they represent different adaptations. Selective acculturation – to partially retain an identity linked to one’s parental origin – is usually thought to be a purposeful adaptation overcome barriers through use of ethnic social capital, and thus associated with positive integration outcomes (Friberg Citation2019). Reactive identities on the other hand is usually conceptualized as a negative reaction to structural discrimination, and associated with negative integration outcomes.

While the major barrier for integration in the US context is generally thought to be race and class, the big barrier for integration in Europe is more often conceptualized along the Muslim–non-Muslim divide (Drouhot and Nee Citation2019). The contrast between European secularism and the much stronger religiosity of Muslim immigrants has been described as a “bright boundary marker” in Europe (Alba Citation2005; Alba and Foner Citation2015; Foner and Alba Citation2008). European societies have a long Christian tradition, but are today among the most secularized in the world, and this is particularly true for the Scandinavian countries (Norris and Inglehart Citation2011). Muslims differ not only in religious affiliation but also in their much higher level of religiosity (van Tubergen and Sindradóttir Citation2011; Voas and Fleischmann Citation2012). Similar to how ethnic identities may be subsumed by broad racial categories in the US context, many scholars have argued that ethnic identities among second-generation Muslim immigrant origin youth may become subsumed or replaced by a stronger focus on religious identity (Jacobson Citation1997; Platt Citation2014). In a European context, differences in identificational assimilation patterns should thus not just be studied along boundaries of race, ethnicity and class, but also along religion. For example, Fleischmann and Phalet (Citation2017), drawing on a large school-based comparative study from Belgium, Netherlands, England, Germany and Sweden, find that national identification is significantly lower among Muslims than any other minority group in all countries except England, suggesting the Muslim/non-Muslim barrier is a major hurdle for the adoption of a national identity in the country of settlement. They argue that this contextual variation in the inclusiveness of national identities for Muslim minorities is directly related to the degree to which European countries have institutionalized religious diversity (Fleischmann and Phalet Citation2017).

Based on the literature we may formulate more precise analytical framework: When analysing identity formation, we must distinguish between self-identity as Norwegian and external ascription as Norwegian, as well as ethnic identity, in terms of identification with the culture and traditions of one’s parents’ country of birth. In order to conceptualize social change, we will focus on differences between immigrant generations, comparing immigrants/first generation with Norwegian-born children of immigrants/second generation, and with youth with mixed origin (the third generation is currently too young to be studied in Norway).

To conceptualize group differences in terms of barriers to identificational assimilation we will focus on region of origin, distinguishing between “white” (operationalized as those originating in Europe and North America) and “non-white” (originating in Africa, Asia and Latin America) immigrant origin youth, as well as between different groups of non-white immigrant origin youth, such as youth originating in Africa, the Middle East or South and East Asia. We will also focus on the importance of class resources – in terms of parental education level and economic status, as well as the students’ own grades from compulsory school. We will also focus on religious affiliation. The purpose is to measure to what extent race, class and religion are barriers to identificational assimilation, and whether these barriers operate through self-identification and/or external categorization/ascription.

National identity and immigration to Norway

Norwegian nationalism grew out of the Romantic movement of the nineteenth century and have traditionally been associated with ideas of primordial ties of common ancestry, but also heavily rooted in enlightenment ideals of human rights and equality. For example, the Norwegian constitution of 1814 was one of the most democratic of its time, heavily inspired by the US declaration of independence (Eriksen Citation2013). Notions of equality have since become increasingly important for Norwegian self-identification with the establishment and expansion of a generous and universal welfare state during the post WWII era.

Despite a national narrative of historical ethnic and cultural homogeneity, a number of ethnic minorities have traditionally been present. The largest is the indigenous Sami of northern Scandinavia. Numbering approximately 40,000 in Norway, the Sami maintain special linguistic and cultural rights as indigenous population, and since 1989 have had their own parliament with legislative power over cultural and regional issues (Eriksen Citation2013). In addition, smaller groups of Jews, Romani, Roma and Kvens have long historical roots. Historically, they have been targeted by oppressive policies of exclusion and forced assimilation, but today they have a certain protection and status as national minorities (Brandal, Døving, and Plesner Citation2017).

Over the last half century, the demographic composition of Norwegian society has changed substantially due to immigration. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century Norway was a country of net emigration (about one-third of the population left, primarily to North America before WWI), but after WWII the country would change into a major destination for immigrants. From the late 1960s labour migrants from Pakistan, Morocco, India, and Turkey arrived in response to the Norway’s economic growth. A moratorium on labour immigration was introduced in 1975, and in the following decades, refugee flows from countries such as Vietnam, Chile, Iran, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Ethiopia, Syria and Eritrea became the major form of immigration. In this period, transnational family formation and family reunification also became an important point of entry (Brochmann and Kjeldstadli Citation2008). From 1994, Norway attracted increasing numbers of immigrants from Nordic countries and Western Europe as part of the open EU/EEA area, and with the eastwards EU enlargements in 2004 and 2007, large numbers of labour migrants from new EU member states like Poland, Lithuania and Romania responded to the pull factors of an expansive Norwegian economy (Friberg Citation2016; Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2018). By 2019, 17.7 per cent of the Norwegian population were either immigrants (14.4 per cent) or native-born children of immigrants (3.4 per cent). It should be noted that immigrants and their descendants make up a larger proportion in urban centres and among young people, and according to Statistics Norway 42 per cent of children born in the capital city Oslo in 2017 were born to parents who were either immigrants or children of immigrants. With an increasingly diverse population, questions of national identity – and more precisely who is to be regarded as a Norwegian – have come to the forefront of public debate.

With a strong social safety net, a publicly funded comprehensive and open education system, and a redistributive system of social benefits (Esping-Andersen Citation1990), Norway is today, along with its Nordic neighbours, among the most equal societies in the world, with high rates of intergenerational socioeconomic mobility (Corak Citation2013). And while integration of low-skilled immigrants is considered to be both costly and challenging for generous welfare states with regulated labour markets (Brochmann and Dølvik Citation2018), research suggests that the same institutional features may be relatively conducive for the integration of the second generation, who display relatively high rates of upward mobility also compared to natives (Hermansen Citation2016; Hermansen Citation2017).

At the same time, a significant body of research demonstrate that ethnic discrimination is widespread and remains a barrier to integration for children of immigrants in Norway. Several field experiments – where fake applications are sent to real job advertisements, show that Norwegian-born children of Pakistani immigrants are approximately 25 per cent less likely of being called in for an interview, compared to majority applicants with identical qualifications (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2016; Midtbøen Citation2016; Quillian et al. Citation2019). Other studies have found evidence of similar levels of discrimination in the rental housing market (Andersson, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2012). Survey-based studies also document a significant amount of perceived labour market discrimination among ethnic minorities. For example, analyses based on Statistics Norway’s Living conditions survey among the immigrant population, conducted in 2016, show that 19 per cent of respondents with backgrounds from Turkey, 13 per cent of respondents with backgrounds from Sri Lanka, 26 per cent of respondents with backgrounds from Pakistan, and 12 per cent of respondents with backgrounds from Vietnam report that they have been subject to discrimination due to their ethnic background by colleagues, superiors or clients during the last twelve months (Midtbøen and Kitterød Citation2019). Norwegian-born children of immigrants are no less prone to feel discriminated against than those who have immigrated themselves, and the relationship between discrimination and integration/assimilation remains less than straight forward. While national identification (feelings of belonging to Norway) and acculturation (high proportion of Norwegian friends) are positively correlated with less experiences of discrimination, structural integration (employed in high-status professions) is positively correlated with more experiences of discrimination, in line with what is often referred to as an “integration paradox” (Midtbøen and Kitterød Citation2019; Steinmann Citation2019).

Data, methods and measures

The analyses use the first wave of the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study in Norway (see also Friberg Citation2019 for description of the data). A survey was administered to students who were 16–17 years old and enrolled in their first year of secondary school (VG1) in 2016. Since secondary education is a universal right in Norway, and practically everyone enrols for the first year, this sample frame is an approximation for the full age cohort. The study covers the capitol city as well as the major adjacent areas and communities (Oslo and Akershus counties, plus selected schools in nearby Drammen). An extensive questionnaire was filled out by the students during school hours, and students who were not present received the questionnaire via the school email system. 7,627 students completed the questionnaire, of which 2,901 had an immigration background. The response rate was 48 per cent, with the majority of non-response at the school level. Due to sample attrition, some caution is necessary when drawing conclusions. The survey data were linked with administrative registry data using personal ID-numbers obtained from school authorities, thus providing reliable information on demographic, parental and economic background variables.

The descriptive analyses compare separate measures of (1) national self-identity (2) national ascription and (3) ethnic identity, for first and second-generation immigrant origin youth as well as youth with mixed Norwegian/immigrant origin, distinguishing between those with an immigrant origin in Europe and North America on the one hand, and those with an immigrant origin in Africa, Asia or Latin-America on the other. In the multivariate analysis, we perform three OLS regressions, using self-identity as Norwegian, ascription as Norwegian and origin country identification as dependent variables. As independent variables, we use a more fine-grained categorization of regional origins (differentiating between Western Europe and North America, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Latin-America, Asia, the Middle East and Africa), generational status (differentiating between first generation, second generation and mixed origin youth), socio-economic/ class resources (in terms of parental socio-economic status and the students own grades), and religion (differentiating between different religious affiliations and the level of religious salience).

Dependent variables: Norwegian self-identity is measured in the CILS-NOR questionnaire using the question “To what extent do you see yourself as Norwegian?”; ascription as Norwegian is measured using the question “To what extent do you think other people see you as Norwegian?”. On both questions, respondents were given four answer categories: “Completely” (= 3), “Partially” (= 2), “A little” (= 1), and “Not at all” (= 0). Ethnic identity is measured using the question “How important is it for you personally to maintain the traditions and culture from your parents country of birth?”, with answer categories: “Very important” (= 3), “quite important” (= 2), “A little important” (= 1), and “Not important” (= 0). In the analyses, all three questions are treated as four-point continuous variables.

Independent variables: Information from the official population registers is used to classify the respondents according to immigration origin, immigrant generation and gender. Region of origin is based on the parents’ country of birth, according to information from the official population registers. In the descriptive analyses, they are grouped into three categories: Norway, Europe and North America, and Africa, Asia and Latin America. For the multivariate analyses, we use a more fine-grained categorization differentiating between Western Europe and N. America, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Latin-America, Asia (excluding the Middle East), the Middle East, and Africa, in addition to those without immigrant background. Information from the official population registers is used to classify the respondents according to immigrant generation. First-generation immigrants are defined as respondents who were born abroad to two non-Norwegian parents. The second generation is defined as those born in Norway to two foreign-born parents (we include in the second generation those few students who are so-called 2.5 generation, meaning they have one parent who is an immigrant and on parent who is second-generation immigrant). Mixed origin are defined as those who have one immigrant parent and one Norwegian-born parent without immigrant parents.

Immigrant origin youth from different world regions differ significantly, not just in terms of how they are perceived racially (European immigrant origin groups largely resembling native Norwegians in phenotype, while those originating in Asia and Africa belonging to racialized categories), but also in terms of class resources and religious affiliation. Immigrants from (Western) Europe tend to have educational levels and socio-economic status in Norway comparable to those of native Norwegians, and their religious affiliation is also similar to that of native Norwegians – either Christian or non-religious. Immigrants from Asia, the Middle East and Africa tend to have more modest levels of education and a majority are firmly placed in the bottom layers of the Norwegian class structure. They are also more often affiliated with non-Christian religious faiths such as Islam, Hinduism or Buddhism.

Parental socioeconomic (SES) is measured using information from public tax registers and The National Education Database about the respondents’ parents’ income and educational status. For parents’ income we combined the income of both parents over the last three years and grouped the population into quintiles. For parental education we use a simple dummy variable indicating whether at least one parent has completed education at university or college level. For the students’ own grades, we use the students’ grade average from compulsory school (completed 10th grade), provided by educational authorities. For the analyses, we divide the sample into quintiles. Religious affiliation is based on students’ self-reports from the CILS-NOR questionnaire. We show dummy variables indicating self-identification as “muslim” or “other non-christian religion” (Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism etc.). The reference category is either Christian or non-religious affiliation.

Results

National identity and assimilation

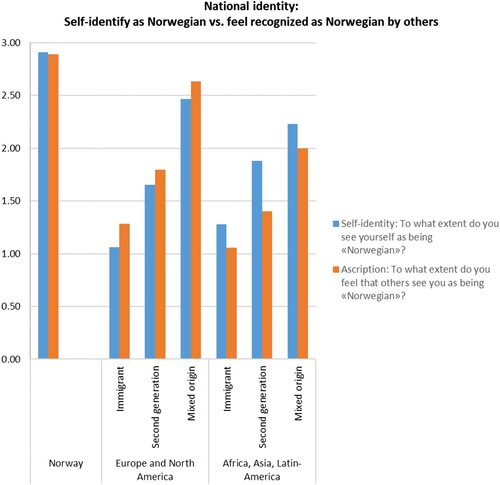

shows the average score on our two different measures of national identity: (1) self-identity (“To what extent do you see yourself as Norwegian”), and (2) ascribed identity (“To what extent do you think other people see you as Norwegian”). Both of them are treated as four-point continuous variables (where 0 = “not at all”, 1 = “a little”, 2 = “partially” and 3 = “completely”), and average scores are broken down by immigrant origin and generational status. The figure shows two distinct patterns.

We find a clear pattern of assimilation in terms of self-identity. Norwegian-born children of immigrants identify as Norwegians more strongly than foreign-born youth, and those of mixed origin identify even more strongly as Norwegian. This pattern applies to both European and non-European origin youth alike. Immigrants and children of immigrants with non-European origin in fact identify more strongly as Norwegian than those of European origin (the pattern is opposite among those who have mixed origin). This pattern suggests that neither race nor religion is a barrier towards the development of a self-identity as being Norwegian.

Regarding ascribed identity, however, the pattern is quite different. While we do find an overall pattern of assimilation in terms of increase across generational status, the two measures are not entirely congruent (r = 0.601). Most importantly, they are non-congruent in different ways for adolescents of European and non-European origin. Young people of non-European origin generally feel that others perceive them as being a far less Norwegian than young people with European immigration origin. Young people with a European immigrant background, on average actually score higher on ascription than self-identify. In other words, they tend to think that others see them as being more Norwegian than they actually see themselves. Young people with a non-European immigrant background, tend to score considerably lower on ascription than self-identify, meaning that they tend to think that others see them as being less Norwegian than they see themselves.

Non-recognition

The results suggest that young people with a European immigration origin – who are usually not very distinct from non-immigrants in terms of racial phenotype or religious belonging – may “blend in” and be accepted as part of the national community to an extent that exceeds their own sense of identification. For young people of non-European origin – who tend to differ from average Norwegians in terms of racial features and in many cases also religious belonging – this is far more difficult. For them it is more common that their own sense of “Norwegianness” is not reflected in how they are defined by those around them. It is worth noting that although both self-identity and sense of ascription as Norwegians increase from the first to the second generation, the negative gap between the two also increases. This means that as young people with an immigrant background from outside Europe gradually develop an identity as being Norwegians, they simultaneously develop an increasing sense of not having their own identity recognized by others.

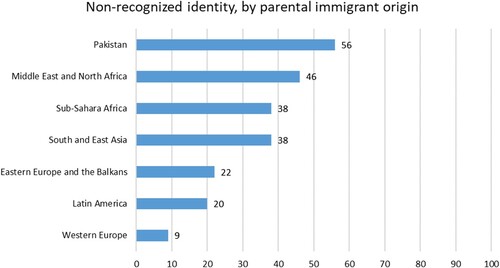

shows the percentage of respondents who score lower on ascription than on self-identity, as a measure of non-recognized Norwegian identity. It shows that a significant proportion among the respondents with an immigrant background from Asia, Africa and the Middle East report that others see them as being less Norwegian than they consider themselves to be. Most pronounced is this pattern among youth with Pakistani-born parents – which is also the largest and most established group among the second generation – among whom as much as 56 per cent report that others see them as being less Norwegian than they see themselves. This non-recognition of identity is far less common among youth with a European immigrant origin – where only 9 per cent report lower score on ascription than on self-identity.

Ethnic identification

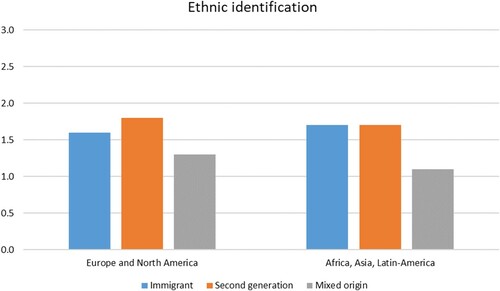

When we turn to ethnic identification, yet another different pattern emerges (see ). There are no differences in the level of ethnic identification between young people with an immigrant origin from Europe and those with an immigrant background from Africa, Asia and Latin America. However, in stark contrast to the significant increase in national identification, there is no corresponding decrease in ethnic identification: the first generation and the second generation on average score roughly the same on our measure of ethnic identification. Among respondents with an immigrant origin from Europe and North America, ethnic identification actually tends to be higher in the second generation compared to the first. Among those of mixed origin, e.g. respondents with one immigrant parent and one non-immigrant parent, identification with the immigrant parent’s origin is lower in both groups. Ethnic identification is negatively correlated with both self-identity (r = −0.236) and ascription (r = −0.213) but the association is quite weak with regard to both. This suggests that changes in ethnic minority identification and national identification develop largely independent from each other. The relationship between ethnic and national identities, including the combination or lack of multiple identities, in terms of compatibility or conflict, as well as the implications for integration more broadly, warrants further research.

The role of race, class and religion – multivariate analyses

So far we have seen that national self-identity and sense of ascription, as well as ethnic identity, are related, yet different dimensions of the identity formation process among young people with an immigrant background in Norway. National self-identity as Norwegian show a clear and relatively similar pattern of assimilation across generations for all groups, but the respondents’ sense of being acknowledged as Norwegians by others do not follow the same pattern. Those of European origin on average tend to think that others see them as being more Norwegian than they see themselves, while the pattern is the opposite for those of non-European origin. For the latter then, the process of identity formation as “Norwegians” is accompanied by an increasing discrepancy between the two – a sense of not having one’s identity recognized by others. Finally, ethnic identification shows no signs of generational change, and is only weakly related to the development of a Norwegian national identity.

Our final question was to what extent ethno-racial origin, class and religious background shape identity formation among minority youth in Norway. To answer that question, we run three separate regression analyses, in order to see how variables such as region of origin (as a proxy for racial status) socioeconomic class resources and religious affiliation – in addition to generational status – affect national self-identity and ascription, and ethnic identification, respectively (see ).

Table 1. OLS regression analysis: determinants of three dimensions of identity: national self-identity, national ascription and ethnic identity.

We focus on our two dimensions of national identity first, before turning to ethnic identity. As already illustrated in the descriptive analyses, generational status – both in terms of being born in Norway or having one Norwegian origin parent – is strongly associated with both measures of national identity.

However, when we look at different regions of origin, which can be interpreted as a proxy for racial status, and using the other Nordic countries as a reference point, we (once again) find clearly diverging patterns. On the one hand, as suggested by the descriptive analyses, parental region of origin is of little importance for the respondents’ national self-identity as Norwegians. Using the Nordic region as a reference point, we find that having an immigration background from Western Europe and Africa is negatively associated with national self-identity, but there is no significant effect of having an immigration background from Eastern Europe and the Balkans, Latin-America, Asia or the Middle East. On the other hand, parental region of origin is strongly related to ascription, or the respondents’ sense of being regarded as Norwegian by others. Moreover, patterns of ascription match the racial status of the respondents. Those with an immigrant background from either Western or Eastern Europe – most of whom are regarded as white – are no less likely to think that others see them as being Norwegian compared to those of Nordic origin. However, having an immigration background from majority non-white regions such as Latin-America, Asia, the Middle East or Africa are all strongly negatively associated with ascribed identity. The relationship between region of origin and ascription, appears to be linked to phenotype, as the negative effect is most pronounced for the more distinctly non-white groups, such as those with an immigrant origin from Africa.

Turing to our measures of socio-economic class resources, we find that the students’ own grades from compulsory school are significantly and positively associated with both measures of identity. Those with higher grades identify more strongly as being Norwegian than those with low grades, and they also feel that others see them as being Norwegian. Once the students’ own grades are taken into account, neither parental income nor education is significantly associated with either measure of national identity.

Religious affiliation – whether Muslim or other non-Christian denomination – does not have any effect upon respondents’ self-identity as being Norwegians (compared to having a Christian or non-religious affiliation). However, being Muslim has a significant negative effect on their sense of being accepted as Norwegians. We find no effect of having other non-Christian affiliations.

The results suggest that self-identity as being Norwegian increases relatively uniformly among all immigrant origin groups, following their exposure to the host society (in terms of generational status) and accumulation of personal resources (in terms of grades). At the same time, however, those who are non-white, and those who are Muslim, face considerable barriers in terms of not feeling accepted as Norwegians by others. As we have seen, because the development of a self-identity as Norwegian largely seems to follow individual integration-related characteristics, while their sense of acceptance by others as being Norwegian is subject to categorical barriers related to race and religion the mismatch between self-identity and acceptance is most common among the children of well-established non-European Muslim immigrant groups, such as adolescents with immigrant parents from Pakistan.

Regarding ethnic identification, the analysis confirms that ethnic identity related to the country of origin develops largely independent from the development of an identification with the country of settlement. While those of mixed origin identifies less with their immigrant parents’ homeland than those with two immigrant parents, there are no significant differences between the first and the second generation. Neither is there a clear pattern in terms of immigration origin. It should be noted that youth with parents from Asia and the Middle East appear to be less attached to the culture and identity of their parental origin, but this is countered by the fact that being Muslim is associated with higher identification with the culture and identity of the parents homeland. This probably reflects how for many Muslims, the culture and identity of their parental homeland is understood in religious terms. Those with better grades identify more strongly with their parental origin. A possible interpretation is that this is a case of reversed causality and an effect of selective acculturation, whereby retaining an identification with one’s parental cultural origin is associated with an “immigrant drive” towards education (see also Friberg Citation2019). It should be noted, however, that we find an even stronger correlation between grades and national identity, reflecting how educational success appears to be associated with a strong identity and sense of self in general, whether this is related to ethnic or national identities. Finally, there is a very strong positive relationship between religious affiliation and ethnic identity. Those belonging to a non-Christian religion – and in particular Muslims – are far more interested in maintaining the traditions and culture of their parental country of origin, than either Christian or non-religious, once again suggesting that for adolescents originating in the Muslim world, the culture and traditions of their parents’ home country is strongly associated with their religious identity as Muslims rather than their national origin.

Discussion

In the present analyses, we have treated our three measures as separate dimensions of identity formation. In reality, two of them at least, namely self-identity and ascription, are intrinsically linked. It is a basic sociological fact that we develop our identities and our sense of self through interactions with others. For immigrant origin youth growing up in Norway it is difficult to develop an identity as being “Norwegian”, if everyone else looks at you like a “foreigner”. When we find that young people with immigrant origin from Africa has a lower sense of national identity than at least those of Nordic origin, this should be interpreted in light of the fact that they are also by far those who feel the least accepted by others as being Norwegians. It is reasonable to assume that their somewhat slower adaptation of a national self-identity as Norwegians is a result of their sense of not feeling accepted as Norwegians. Nevertheless, the results show that the two dimensions can develop along different patterns, and that racial and religious barriers do not necessarily preclude the formation of an identity as being Norwegian. For example, youth with immigrant parents from Asia and the Middle East appear to adopt a national identity as Norwegians even faster than youth with immigrant parents from Western Europe and North America, despite their lack of acceptance as Norwegians by others. Regarding ethnic identities, we find that children of immigrants tend to maintain a certain identification with their parental origin. This is the case for both European and non-European origin youth. The findings suggest that ethnic identities are formed and maintained rather independently of the development of a national identity as Norwegians. For many young people of immigrant origin there is no opposition between feeling Norwegian and at the same time express a desire to maintain the culture and traditions of their parents’ home countries, thus emphasizing the salience of dual, hyphenated or multiple identities common among immigrant origin youth (Wiley et al. Citation2019). This finding is also consistent with Beauchemin, Hamel, and Simon (Citation2018), who finds that ethnic origin remains salient for the identities of children of immigrants in France, even as they simultaneously adopt an identity as being French.

Focusing on the formation of national identity, and how the findings relate to the theoretical debates in the field, a dual pattern emerges. On the one hand, the findings support the general claims by the classical and contemporary assimilation theory. Although cross-sectional data cannot give conclusive evidence for whether generational differences measure temporal changes or merely reflect compositional differences between different immigrant cohorts, the overall pattern is quite clear. Those born in Norway have adopted a far stronger national identity as Norwegians than those born abroad, and those of mixed ancestry identify even more strongly as Norwegians. This is in line with research from other European countries (see e.g. the Spanish ILSEG-study, Portes, Aparicio, and Haller Citation2016). Importantly, this pattern holds for both European and non-European origin groups, as well as for youth with different religious affiliations. In fact, respondents with non-European immigration background overall tend to identify more as Norwegians than those with European immigrant background. All in all, our results clearly indicate that immigrant origin youth, regardless of origin, over time and across generations, gradually do adopt a national identity as Norwegians. For those who are concerned that immigration over time will erode the shared sense of national identity underpinning the legitimacy, social cohesion and solidarity of the nation state, this finding should be somewhat reassuring. The multivariate analysis shows that apart from immigrant generation, educational success in terms of the students’ own grades is a major predictor of national self-identity, supporting the notion that national identity formation is closely related to the accumulation of cultural and economic capital. Importantly, being Muslim does not imply significantly lower levels of self-identification as Norwegian, compared to other religious groups. Although our analyses are not directly comparable to those of Fleischmann and Phalet (Citation2018), this suggests that Norway is more similar to England, where being Muslim is not associated with lower levels of national identification, than to Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany or Sweden, where it is. In terms of self-identity, then, our findings suggest that Norwegian national identity is comparatively inclusive towards Muslim minorities. It should be noted, however, that the respondents were adolescents in their first year of secondary school, and it remains uncertain how their identity formation will play out once they leave this relatively inclusive and nurturing institutional environment.

When looking at ascription, however, the results clearly indicate that many young people – and Muslims in particular – nevertheless face considerable opposition in their development of such a national identity. Respondents with an immigrant background from Africa, Asia and the Middle East report that others see them as far less Norwegians than those with an immigrant background from other countries in Europe. When looking at ascription, there is also a considerable negative penalty associated with being Muslim compared to other religious identities. Much of the current literature on integration in Europe suggests that religion – and in particular the Muslim/ non-Muslim divide – is a major barrier for integration in Europe, in contrast to the US where race is considered a major barrier. Our findings suggest that both factors – race and religion – constitute barriers for acceptance and recognition. The result is that a considerable share of the second generation develop an identity as Norwegians while simultaneously develops an increasing sense of not having one’s own identity recognized by others. This finding is consistent with research pointing to the so-called integration paradox, which structural integration is associated with more self-reported experiences of discrimination, due to higher expectations of equal treatment and because integration in majority social arenas provide more opportunities for discriminatory treatment and feelings of exclusion (Midtbøen and Kitterød Citation2019; Steinmann Citation2019). Our findings reveal a similar integration paradox: the more immigrant origin adolescents self-identify as Norwegian – the greater the contrast to how they feel others view them as outsiders. This does not imply that race or religion constitute insurmountable hurdles to belonging. After all, the respondents’ sense of recognition does increase along with generational status – although not in congruence with their even more rapidly changing sense of self-identification. It does, however, illustrate how the process of integration itself – where traditional boundaries of what it means to be Norwegian are stretched, negotiated and challenged by a new generation of diverse youth – is filled with conflict, friction and frustrations, particularly for those who are non-white and/or Muslim.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alba, R. 2005. “Bright vs. Blurred Boundaries: Second-Generation Assimilation and Exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28: 20–49.

- Alba, R. 2014. “The Twilight of Ethnicity: What Relevance for Today?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37: 781–785.

- Alba, R., B. Beck, and D. Basaran Sahin. 2018. “The U.S. Mainstream Expands – Again.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 99–117.

- Alba, R., and N. Foner. 2015. Strangers No More: Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 2009. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Anderson, B. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso books.

- Andersson, L., N. Jakobsson, and A. Kotsadam. 2012. “A Field Experiment of Discrimination in the Norwegian Housing Market: Gender, Class, and Ethnicity.” Land Economics 88: 233–240.

- Barth, F. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries the Social Organization of Cultural Difference. New York: Little Brown.

- Beauchemin, C., C. Hamel, and P. Simon. 2018. Trajectories and Origins: Survey on the Diversity of the French Population. Cham: Springer.

- Berry, J. W. 2005. “Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29: 697–712.

- Birkelund, G. E., K. Heggebø, and J. Rogstad. 2016. “Additive or Multiplicative Disadvantage? The Scarring Effects of Unemployment for Ethnic Minorities.” European Sociological Review 33: 17–29.

- Brandal, N., C. A. Døving, and ITe Plesner. 2017. Nasjonale minoriteter og urfolk i norsk politikk fra 1900 til 2016. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Brochmann, G., and J. E. Dølvik. 2018. “The Welfare State and International Migration: The European Challenge.” Routledge Handbook of the Welfare State, 508–522.

- Brochmann, G., and K. Kjeldstadli. 2008. A History of Immigration: The Case of Norway 900–2000. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Brubaker, R. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brubaker, R. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 21–42.

- Çelik, Ç. 2015. “‘Having a German Passport Will Not Make me German’: Reactive Ethnicity and Oppositional Identity among Disadvantaged Male Turkish Second-Generation Youth in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38: 1646–1662.

- Corak, M. 2013. “Inequality from Generation to Generation: The United States in Comparison.” In The Economics of Inequality, Poverty, and Discrimination in the 21st Century, edited by R. Rycroft, 107–126. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Diehl, C., and R. Schnell. 2006. “‘Reactive Ethnicity’ or ‘Assimilation’? Statements, Arguments, and First Empirical Evidence for Labor Migrants in Germany.” International Migration Review 40: 786–816.

- Drouhot, L. G., and V. Nee. 2019. “Assimilation and the Second Generation in Europe and America: Blending and Segregating Social Dynamics Between Immigrants and Natives.” Annual Review of Sociology 45: 177–199.

- Eriksen, T. H. 2013. Immigration and National Identity in Norway. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

- Esping–Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fleischmann, F., and K. Phalet. 2018. “Religion and National Identification in Europe: Comparing Muslim Youth in Belgium, England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 49: 44–61.

- Foner, N., and R. Alba. 2008. “Immigrant Religion in the U.S. And Western Europe: Bridge or Barrier to Inclusion?” The International Migration Review 42: 360–392.

- Friberg, J. H. 2016. “New Patterns of Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe and Its Impact on Labour Markets and Institutions in Norway: Reviewing the Evidence.” In Labour Mobility in the Enlarged Single European Market, edited by J. E. Dølvik, and L. Eldring, 19–43. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Friberg, J. H. 2019. “Does Selective Acculturation Work? Cultural Orientations, Educational Aspirations and School Effort among Children of Immigrants in Norway.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (15): 1–20.

- Friberg, J. H., and A. H. Midtbøen. 2018. “The Making of Immigrant Niches in an Affluent Welfare State.” International Migration Review. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318765168.

- Gordon, M. M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Haller, W., A. Portes, and S. M. Lynch. 2011. “Dreams Fulfilled and Shattered: Determinants of Segmented Assimilation in the Second Generation.” Social Forces; a Scientific Medium of Social Study and Interpretation 89: 733–762.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2016. “Moving Up or Falling Behind? Intergenerational Socioeconomic Transmission among Children of Immigrants in Norway.” European Sociological Review 32: 675–689.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2017. “Et egalitært og velferdsstatlig integreringsparadoks?” Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift 1: 15–34.

- Jackson, M., J. O. Jonsson, and F. Rudolphi. 2012. “Ethnic Inequality in Choice-Driven Education Systems.” Sociology of Education 85: 158–178.

- Jacobson, J. 1997. “Religion and Ethnicity: Dual and Alternative Sources of Identity among Young British Pakistanis.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 20: 238–256.

- Jenkins, R. 2008. Rethinking Ethnicity. London: Sage.

- Kao, G., and M. Tienda. 1995. “Optimism and Achievement: The Educational Performance of Immigrant Youth.” Social Science Quarterly 76 (1): 1–19.

- Keller, U., and K. H. Tillman. 2008. “Post-Secondary Educational Attainment of Immigrant and Native Youth.” Social Forces 87: 121–152.

- Koopmans, R. 2015. “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility Against Out-Groups: A Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41: 33–57.

- Midtbøen, A. H. 2016. “Discrimination of the Second Generation: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Norway.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 17: 253–272.

- Midtbøen, A. H., and R. H. Kitterød. 2019. “Beskytter assimilering mot diskriminering?” Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift 3: 353–371.

- Miller, D. 1995. On Nationality. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Nandi, A., and L. Platt. 2015. “Patterns of Minority and Majority Identification in a Multicultural Society.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38: 2615–2634.

- Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2011. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Platt, L. 2014. “Is There Assimilation in Minority Groups’ National, Ethnic and Religious Identity?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37: 46–70.

- Portes, A., R. Aparicio, and W. Haller. 2016. Spanish Legacies: The Coming of age of the Second Generation. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and P. Fernández-Kelly. 2008. “No Margin for Error: Educational and Occupational Achievement among Disadvantaged Children of Immigrants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 620: 12–36.

- Portes, A., P. Fernandez-Kelly, and W. Haller. 2005. “Segmented Assimilation on the Ground: The New Second Generation in Early Adulthood.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28: 1000–1040.

- Portes, A., and A. Rivas. 2011. “The Adaptation of Migrant Children.” The Future of Children 21: 219–246.

- Portes, A., and R. G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96.

- Quillian, Lincoln, Anthony Heath, Devah Pager, Arnfinn H. Midtbøen, Fenella Fleischmann, and Ole Hexel. 2019. “Do Some Countries Discriminate More Than Others? Evidence from 97 Field Experiments of Racial Discrimination in Hiring.” Sociological Science 6: 467–496.

- Rumbaut, R. G. 1994. “The Crucible Within: Ethnic Identity, Self-Esteem, and Segmented Assimilation among Children of Immigrants.” International Migration Review 28: 748–794.

- Rumbaut, R. G. 2008. “Reaping What You Sow: Immigration, Youth, and Reactive Ethnicity.” Applied Developmental Science 12: 108–111.

- Smith, A. D. 1991. National Identity. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

- Smith, A. D. 1995. Nations and Nationalism in a Global Era. Cambridge: Wiley.

- Steinmann, J.-P. 2019. “The Paradox of Integration: Why Do Higher Educated new Immigrants Perceive More Discrimination in Germany?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 1377–1400.

- Van De Vijver, F. J., and K. Phalet. 2004. “ Assessment in Multicultural Groups: The Role of Acculturation.” Applied Psychology 53: 215–236.

- van Tubergen, F., and J. Í. Sindradóttir. 2011. “The Religiosity of Immigrants in Europe: a Cross-National Study.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 272–288.

- Vassenden, A. 2010. “Untangling the Different Components of Norwegianness.” Nations and Nationalism 16: 734–752.

- Vassenden, A. 2011. “Hvorfor en sosiologi om norskhet må holde norskheter fra hverandre.” SOSIOLOGI I DAG 41: 156–182.

- Voas, D., and F. Fleischmann. 2012. “Islam Moves West: Religious Change in the First and Second Generations.” Annual Review of Sociology 38: 525–545.

- Warner, W. L., and L. Srole. 1945. The Social Systems of American Ethnic Groups. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Wiley, S., F. Fleischmann, K. Deaux, and M. Verkuyten. 2019. “Why Immigrants’ Multiple Identities Matter: Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice.” Journal of Social Issues 75: 611–629.