ABSTRACT

Personal values become increasingly relevant for immigrant-related bias in the European context. Situated in group conflict theories, human values theory and social identity theory encourage different interpretations of how our interest in the welfare of those closest to us, i.e. the in-group (benevolence), and the prosperity of all beings (universalism) inform attitudes towards immigrants. The present study examines how these self-transcending human values affect perceptions of immigrant threat. Using nationally pooled data from the European Social Survey (ESS) for fifteen European countries, the results show that benevolence and universalism tend to affect perceived immigrant threat in opposite directions. A part of individuals’ anti-immigrant bias does not stem from strictly self-interested motivations, as often proposed, but by a sense of loyalty to the interests of our immediate contacts. The group we place our loyalty matters. So does the national context suggesting that grand scheme interpretations can fall short.

Introduction

In the aftermath of the recent debt and refugee crises, European societies appear to struggle accepting immigrants. Much of this negativity is attributed to the distinct threats immigrants are perceived to pose in the host society (Davidov et al. Citation2020; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2016; Quillian Citation1995; Schneider Citation2007). Immigrants endanger the subsistence of blue-collar workers by offering cheaper alternatives to natives (Bonacich Citation1972) and challenge the long-standing, ethnically homogeneous composition of European imagined communities (Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006), to name a few.

In recent years, researchers have turned to the examination of human values as a determinant of individuals’ appraisals of immigrants. Human values are far-reaching desirable goals that guide individuals’ actions, views, and behaviours (Schwartz Citation1994). Others are evaluated based on whether they enable or threaten the fulfilment of these goals. Hence, values have the potential to explain why immigrants are perceived as a threat or not. Indeed, studies show that values are primary predictors of immigrant-related attitudes (Sagiv et al. Citation2017). Moreover, people are increasingly more susceptible to values than facts (Westen Citation2009), making value-based interventions particularly promising in effecting attitudinal change towards immigrants (Bardi and Goodwin Citation2011).

The present studyFootnote1 attempts to contribute to this field of research by clarifying how the self-transcending values of benevolence and universalism affect perceptions of immigrant threat. Human values theory (Schwartz Citation1994, Citation2007a) proposes that, by setting aside personal interests, individuals who value the welfare of their closest others, a.k.a. their in-group (benevolence), and those who care for the well-being of all human beings (universalism) are prone to care for immigrants as well. On the contrary, social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Turner et al. Citation1987) suggests that prioritizing the well-being of our group members will lead to more negative feelings towards outsiders, such as immigrants. These hypotheses are tested with the use of nationally pooled data from 15 European countries between 2002 and 2016. Ultimately, I argue that the examination of benevolence can offer necessary insights regarding anti-immigrant views beyond the popular reduction to self-interests.

Perceived immigrant threat

Perceptions of immigrant threat refer to subjective feelings of threat triggered by the prospective or existing presence of foreigners in a community. Intergroup threat transpires “when one group’s actions, beliefs, or characteristics challenge the goal attainment or well-being of another group” (Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Citation2006, 336). As a result, future intergroup contact is deemed as potentially detrimental for the majority group (Stephan and Renfro Citation2002). Immigrants have been construed to pose threats to individuals’ safety (Brambilla et al. Citation2013; van der Linden and Jacobs Citation2017), modernity values (Walsh, Tartakovsky, and Shifter-David Citation2019), group esteem and distinctiveness (Riek, Mania, and Gaertner Citation2006), as well as threats emanating from intergroup anxiety and negative stereotypes (Stephan et al. Citation1998). Most notably, members of the host community tend to view immigrants as realistic competitors for scarce, material resources (Bonacich Citation1972; Esses, Jackson, and Armstrong Citation1998; Murray and Marx Citation2013; Quillian Citation1995), such as jobs and welfare benefits, and/or symbolic threats to the cultural values, morals, identity, and religious practices of their community (Davidov et al. Citation2020; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2016; Leong and Ward Citation2011).

Informed by a broad range of group conflict traditions (Blalock Citation1970; Blumer Citation1958; Esses, Jackson, and Armstrong Citation1998; Sears Citation1988; Sherif Citation1967; Stephan et al. Citation1998), empirical studies have shown how different socioeconomic factors and group positions contribute to perceptions of immigrant threat. At the community level, economic instability is identified as a threat-inducing condition (Meuleman et al. Citation2020; Wallace and Figueroa Citation2012). In the presence of a sizable immigrant population, these feelings are exacerbated by scarcity concerns (Schlueter and Scheepers Citation2010). At the individual level, low-income groups, blue-collar labourers, the lower educated, and the unemployed are more susceptible to feelings of interethnic competition and threat due to their financial precariousness (Kunovich Citation2013; Pichler Citation2010; Schlueter, Meuleman, and Davidov Citation2013; Schlueter and Scheepers Citation2010; Stupi, Chiricos, and Gertz Citation2016). However, this pattern is less robust among underprivileged, racial minorities than Whites (Kunovich Citation2013; Stupi, Chiricos, and Gertz Citation2016). This fact showcases the interplay between economic competition and ideology, including racism (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2016), political conservatism (Erisen and Kentmen-Cin Citation2017; Hitlan et al. Citation2007; Kunovich Citation2013; Pichler Citation2010; Stupi, Chiricos, and Gertz Citation2016), and nationalism (Burhan and van Leeuwen Citation2016). Other commonly theorized predictors have yielded mixed results. For example, religiosity is both found to “make and break” threat-related concerns about immigrants (Lubbers, Coenders, and Scheepers Citation2006; Schlueter and Scheepers Citation2010). In contrast, positive interethnic contact enables members of the host society to assuage at least some of their anti-immigrant fears (Kunovich Citation2013; Meuleman et al. Citation2020; Schlueter and Scheepers Citation2010).

This body of research has laid the groundwork for our understanding of attitudes towards immigrants and immigration. Nevertheless, Ceobanu and Escandell (Citation2010) note that hesitation to depart from traditional theoretical models and lack of conceptual clarity have often restricted the prospects of immigration research. Building upon the idea that values are the ultimate predictors of attitudes and behaviours (Rokeach Citation1973), human values theory (Schwartz Citation1994) has been received as a valuable toolkit for the examination of intolerance, especially in the context of immigrants. Values are often shown to have the strongest effect on immigrant-related attitudes, even when compared to well-established socio-demographic and other individual-level factors (Sagiv et al. Citation2017).

The present study responds to the need for conceptual clarity by examining how the self-transcending values of benevolence and universalism affect individuals’ perceptions of immigrant threat. Simultaneously, by paying closer attention to the widely neglected concept of benevolence, this study provides an account of the role our concern for the welfare of those closest to us – and not only ourselves – plays in the expression of anti-immigrant sentiments.

Theoretical framework

Human values theory

Human values are defined as “desirable transsituational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or other social entity” (Schwartz Citation1994, 21). They emerge in response to fundamental biological and social needs, such as self-preservation, regulation of interpersonal exchanges, protection and advancement of the group (Schwartz Citation2007a; Schwartz and Bilsky Citation1987). Values are thought to (a) fulfil social interests, (b) compel individuals or entities to partake in action, (c) provide yardsticks for the evaluation and validation of action, and (d) be the product of socialization to the majority’s values and personal life-shaping experiences (Schwartz Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2007a).

The model positions four higher-order, value priorities in a circular continuum along two orthogonal axes. In the first dimension, the pursuit of personal gains (i.e. self-enhancement) is opposed to concerns about others’ well-being (i.e. self-transcendence). In the second dimension, individuals tend to be characterized either by an openness to change or adherence to the conservation of the status quo (Schwartz Citation1994). These principal value orientations correspond to ten lower-order values (see Footnote2). Contrasted values represent relatively incompatible life priorities, while adjacent values are viewed as compatible motivational goals. The two-dimensional structure of human values has been repeatedly validated with multiple samples in more than 80 countries (Bilsky, Janik, and Schwartz Citation2011; Schwartz Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2007a; Schwartz and Boehnke Citation2004; Steinmetz et al. Citation2009).

Table 1. Schwartz’s Basic Human Values.

Human values can be consequential for relations with immigrants. They reflect what individuals consider important in life and they are inextricably tied to the attainment of specific goals and interests (Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Schwartz Citation1994; Schwartz and Bilsky Citation1987). Depending on one’s values, immigrants can be construed as an obstacle or an asset on our pursuits, exacerbating or subduing feelings of threat, respectively. For instance, for individuals who prioritize harmony and societal stability (i.e. security), the inflow of non-natives disturbs their coveted equilibrium. In contrast, for those who see the ideal life as an adventure (i.e. stimulation), multiculturalism can offer new sources of excitement.

Drawing from Schwartz’s (Citation1994, Citation2007a) propositions, several observational and experimental studies offer wide support for the relationship between human values and prejudice towards immigrants. In particular, individuals who assign greater significance to self-transcendence values tend to oppose immigration less (Davidov et al. Citation2008; Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Kilburn Citation2009; Ramos and Vala Citation2009), be more open to voluntary contact with immigrants (See, Lim, and Pauketat Citation2020), prefer integrationist and individualized acculturation strategies (Sapienza et al. Citation2010), and feel less threatened by immigrants (Wolf, Weinstein, and Maio Citation2019). Similar findings have been found for the lower-order, self-transcending value of universalism (Davidov et al. Citation2014, Citation2020; Meuleman et al. Citation2020; Vecchione et al. Citation2012). Moreover, openness to change values are associated with pro-immigrant sentiments (Kilburn Citation2009), especially self-direction and hedonism (Walsh, Tartakovsky, and Shifter-David Citation2019). In contrast, negative appraisals of immigrants and exclusionist tendencies have been linked with the higher-order values of self-enhancement (Kilburn Citation2009; Wolf, Weinstein, and Maio Citation2019), and conservation (Davidov et al. Citation2008, Citation2020; Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Kilburn Citation2009; Ramos and Vala Citation2009; Sapienza et al. Citation2010; See, Lim, and Pauketat Citation2020), as well as the lower-order values of conformity-tradition (Davidov et al. Citation2008; Meuleman et al. Citation2020), security (Vecchione et al. Citation2012), and power (Walsh, Tartakovsky, and Shifter-David Citation2019).

Unsurprisingly, one can notice that self-transcending values have received the lion’s share within this growing body of work. Theorized as prosocial values in stark contrast to self-interested preoccupations, benevolence encapsulates the importance people place in the “preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact,” the in-group. Universalism reveals a broader, non-qualified interest in the welfare of all human and non-human entities (Schwartz Citation2003, 268). Hence, it is expected that both values would tend to decrease anti-immigrant sentiments (Schwartz Citation1994, Citation2007a), a proposition that justifies the authoritative use of self-transcendence constructs in immigration research. However, the idea that as long as people care for anyone else other than themselves, they should care for the fortune of immigrants imposes a false dichotomy between self and others and neglects the well-documented, powerful role of social identities in prejudice. To this discussion, I turn next.

Social identity theory

Social identity theory (SIT) derives from a series of studies by Tajfel (Citation1979) and Tajfel and Turner (Citation1979) and aims at explaining prejudice-related phenomena, intergroup dynamics, group processes, and self-identity (Hogg and Reid Citation2006). According to Tajfel, a social identity is “the individual’s knowledge that he belongs to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to him of his group membership” (Turner Citation1975, 7). Social identity is built upon and, in turn, enhances the perception that social groups are composed of like-minded individuals who identify with one another, understand themselves and their fellow members as relatively interchangeable, hold similar views, and engage in similar practices that, simultaneously, are distinct from those of the outgroup (Stets and Burke Citation2000; Turner et al. Citation1987; Yuki Citation2003).

The development of a social identity takes place through two interrelated processes: social categorization and social comparison. Individuals are naturally inclined to classify objects and subjects into groups as a way to optimize information management, make social settings more comprehensible, and set standards for interpersonal exchanges (Tajfel Citation1979). When people categorize themselves, cognitively salient in- and out-groups emerge (Turner et al. Citation1987). Social groups often become sources of worth as they provide important means to assess one’s position to the social hierarchy by enabling comparisons with other social groups, their members, and group traits (Hogg and Terry Citation2000; Hornsey Citation2008). With positive self-identity depending on group status, individuals are compelled to favour their in-group and engage in intergroup competition to maintain their self-esteem (Abrams and Hogg Citation1988; Brown Citation2000; Hornsey Citation2008).

Social identity research has consistently linked in-group belonging with anti-immigrant views (Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan, and Lahav Citation2015; Mangum and Block Citation2018; Saroglou et al. Citation2009; Sniderman, Hagendoorn, and Prior Citation2004; Wojcieszak and Garrett Citation2018; Wright Citation2011). Here, SIT allows us to reinterpret the relationship between benevolence and perceived immigrant threat. Social identity processes are considered an antecedent of benevolence. When individuals begin to identify with a group, their personal outcomes and well-being become inextricably connected to those of the in-group (Brewer Citation1979; Turner et al. Citation1987; Vugt and Hart Citation2004). In this context, a group of people can be perceived as threatening not because they undermine one’s solely individual interests, but the social identification, in-group ties, social status, and symbolic resources of the in-group and their fellow members’ (Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan, and Lahav Citation2015; Branscombe et al. Citation1999).

In light of the role of group belonging in intergroup bias, a social identity perspective challenges the idea that both lower-order, self-transcending values would have a unidirectional effect on perceived immigrant threat. Benevolence for the in-group may, in fact, be malevolent for immigrants.

Research hypotheses and objectives

The present study seeks to test the competing propositions of human values theory (HVT) and social identity theory (SIT) regarding the relationship between benevolence and perceptions of immigrant threat in different European societies. Similar to universalism, benevolence represents a self-transcending value: individuals who espouse them tend to prioritize the welfare of others above and beyond personal interests. For HVT, this means that benevolence would yield a negative effect on anti-immigrant sentiments, although less robust than universalism (Davidov et al. Citation2008). For SIT, benevolence defined as a value priority for the well-being of the members of the in-group is tied to more readily available “us” vs. “them” boundaries, ethnocentrism, and outgroup prejudice, whilst universalism points toward the notion of a “human identity” (Hornsey Citation2008; Turner et al. Citation1987) that trumps intergroup distinctions and bias. It follows that (H1) in contrast to universalism, benevolence will tend to have a positive effect on perceived immigrant threat.

To be clear, the present study does not attempt to challenge the well-established structure of human values (Bilsky, Janik, and Schwartz Citation2011; Schwartz Citation1994), which suggests that universalism and benevolence covary. Indeed, I affirm the strong tendency of people who value the welfare of those around them to value the well-being of distant individuals. However, it remains empirically unclear whether this coexistence bears elements of conflict. For example, individuals who prioritize the welfare of those closest to them and of all others are likely to be caught up in competing loyalties since the Other (immigrants) can be felt as a threat to the welfare of the in-group. Therefore, I also hypothesize that (H2) the effect of universalism on perceived immigrant threat will depend on the score on the value orientation of benevolence (i.e. interaction effect).

To test these hypotheses, I employ a country by country analysis of nationally pooled data from the European Social Survey for 15 European countries. This approach encourages analytic clarity and a straightforward illustration of the directional pattern for each value in each country. Schwartz (Citation2007b) noted that self-transcending values can vary in distinctiveness in some cultural contexts. Moreover, several typically emigrant, eastern and southern European countries are relatively new immigrant destinations at scale (Winders Citation2014). Previous research has found that traditional socio-economic predictors can be less insightful in recent immigrant destinations, such as Portugal (Ramos and Vala Citation2009). Taking all the above into consideration, it is difficult to anticipate or seek, for that matter, an overarching, cross-national pattern.

Substantively, this research will allow us to disentangle the effect of benevolence from universalism on individuals’ perceptions of immigrant threat. To my knowledge, previous research has only reported bivariate correlations of benevolence and appraisals of immigrants (Vecchione et al. Citation2012; Walsh, Tartakovsky, and Shifter-David Citation2019) with the use of non-representative samples. Given the considerable covariance between universalism and benevolence, these results are far from conclusive. Notably, the present study will help us to revisit a sizable body of existing research on human values and attitudes towards immigrants and assess the authoritative use of self-transcendence as a higher-order measure in it. Simultaneously, it will inform future methodological approaches regarding these constructs. With the Portrait Value Questionnaire as a permanent module of the European Social Survey, it is fair to assume that human values research will proliferate, increasing the necessity for conceptual and empirical clarity. Last, to the extent that value-based interventions (Bardi and Goodwin Citation2011) bring promising outcomes for attitudinal change regarding immigration, an accurate estimation of which values can be targeted constructively becomes of utmost importance for applied contexts.

Methods

Data

The data for the analysis come from the European Social Survey (ESS) (ESS 1-8. Citation2018). The ESS is an ongoing, biannual research project under the supervision of the European Commission, the European Science Foundation, and various academic institutions in the partaking countries. The survey is widely known for its high methodological standards (Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010), including strict probability sampling of individuals aged 15 and above, high targeted response rate (>70% or higher than the previous round), and rigorous questionnaire construction, item translation protocols, and measurements. A coordination team in each participant country is in charge of the development of the sampling design following the standards of the survey specifications. The participants are recruited with the use of sampling frames of individuals, households, and/or addresses and the data collection takes place through face-to-face interviews within a 5-month fieldwork period.Footnote3

Here, I am using nationally pooled data from the available rounds of the European Social Survey between 2002 (Round 1) and 2016 (Round 8). Fifteen countries participated in all eight rounds and were included in the analysis (sample size in parentheses): Belgium (12,418), Finland (15,443), France (13,465), Germany (20,701), Hungary (12,712), Ireland (15,601), Netherlands (13,290), Norway (11,648), Poland (13,796), Portugal (13,889), Slovenia (9,792), Spain (13,919), Sweden (12,335), Switzerland (10,286), and United Kingdom (15,383). The samples strictly represent participants who report being citizens born in the country of the interview.

Variables

Dependent variable

Perceived immigrant threat was constructed with three items asking participants to appraise the economic, cultural, and general impact immigrants have in the country. Each item was measured on an 11-point scale. Original codes were reversed so that higher scores would indicate higher feelings of perceived threat. The reliability analysis for the composite measure yielded widely acceptable scores across all 15 countries (.762 ≤ α ≥ .886).

Independent variables

Benevolence and universalism were measured by two and three items, respectively, from the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ), which is part of the permanent ESS modules. Each item describes what is important to a hypothetical character. Participants disclose their personal values indirectly by indicating how much this character is like them, from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me). Upon Schwartz’s (Citation2003) recommendation, the indicesFootnote4 were averaged and centred on the respondent’s mean for the entire PVQ module to remove individual variation in responses.

Control variables

Previous research suggests several useful control variables.Footnote5 Financial difficulties capture the subjective feeling of financial deprivation. Participants were asked to indicate their feelings about their household’s income on a 4-point scale (1 – living comfortably on present income, 4 – very difficult on present income). Unemployed is a dummy variable created to reflect those who reported being unemployed and actively looking for a job or not in the last seven days (1), compared to every other employment status (0). Religiosity is a complex construct and single measures tend to be poor indicators. Therefore, I am using a composite measure comprised of three items. Each item reflects a different dimension of religiosity such as belief, institutional bonds, and personal devotion (Bohman and Hjerm Citation2014). The Cronbach’s alpha for reliability is sufficiently high (.798 ≥ α ≤ .851). Placement on a left/right political scale serves as a measure of political orientation. Higher scores on the scale suggest higher levels of political conservatism. Gender is a dummy variable (with 0 – female and 1 – male). Age of the respondent was measured in continuous years and education recorded the number of years of full-time education they completed. Last, I control for the year-round of the survey (with 2002 as the reference category) as advised with the use of pooled national data. offers an overview of the variables, items’ wording, and response categories.

Table 2. Items Measuring Values, Perceived Immigrant Threat, and Control Variables.

Before the analysis, missing values were replaced through decision trees with tree surrogates in SAS Enterprise Miner 14.2. This process creates a predictive model of missing values based on participants’ responses to other questions, thus optimizing the imputation.

Results

shows the main descriptive characteristics of the national samples. Among the 15 European countries, Hungarian individuals exhibited the highest levels of perceived immigrant threat (M = 17.39, SD = 6.07), followed by the Slovenians (M = 16.35, SD = 5.97) and the Portuguese (M = 16.03, SD = 5.59), while Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden (M = 11.27, SD = 5.75) and Finland (M = 12.24, SD = 5.18) had the lowest.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables across 15 European Countries (Means and Standard Deviations in Parentheses).

The results of the multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS)Footnote6 analyses offer wide support of hypothesis 1. Specifically, it appears that universalism maintains a statistically significant, negative effect on perceived immigrant threat in all fifteen countries included in the analysis. As expected, the effect of benevolence on the dependent variable does not follow the same direction. All else equal, individuals with higher scores on benevolence tend to report more pronounced feelings of immigrant threat in thirteen of the countries. In Poland (b = −0.091, p > .05) and Portugal (b = −0.018, p > .05), the association seems to be negative, but it fails to reach a conventional level of statistical significance.

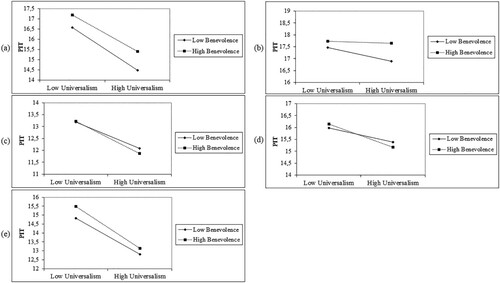

Simultaneously, according to the results presented in , a statistically significant interaction between universalism and benevolence on perceived immigrant threat is found in five countries (H2). The subsequent two-way linear interaction plots (see ) indicate that the patterns of moderation are far from homogeneous. Among participants from Belgium (b = 0.248, p < .05) and Hungary (b = 0.343, p < .001), benevolence tends to moderate the effect of universalism on the dependent variable among participants with higher universalist values. In contrast, for Spanish nationals (b = −0.262, p < .01), the effect of benevolence is more pronounced at the other end of the spectrum of universalism where it increases perceptions of immigrant threat among individuals who have low scores on universalism. These findings are generally in line with the propositions of SIT. However, this does not seem to be the case with the direction of the interaction effect for Polish participants (b = −0.195, p < .05). As (c) shows, higher scores in benevolence lead to more robust reductions in one’s level of perceived immigrant threat on average when they correspond with high scores in universalism, lending support to HVT. Last, the pattern is mixed for Portuguese participants (b = −0.249, p < .001). That is, high benevolence scores tend to increase perceptions of immigrant threat when universalism scores are low (SIT) but tend to decrease them when universalism scores are high (HVT).

Figure 1. Interaction Effect of Universalism and Benevolence on Perceived Immigrant Threat among (a) Belgian, (b) Hungarian, (c) Polish, (d) Portuguese, and (e) Spanish Nationals.

Table 4. Selected Ordinary Least Squares Estimates for Perceived Immigrant Threat across 15 European Countries.

Discussion

As European societies deal with the aftermath of the financial crisis, the explosion of migratory flows inside and outside the EU, and growing Euroscepticism, immigration comes at the forefront of public debate. Drawing from human values theory (Schwartz Citation1994) and social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979), this study examined how self-transcending values influence individuals’ perceptions of immigrant threat in fifteen European countries.

The results offer wide support for the research hypotheses. While universalism maintains a uniformly, statistically significant negative effect, benevolence tends to increase perceptions of immigrant threat in 13 out of the 15 countries examined in the study. This finding directly contradicts the proposition that benevolence, as a self-transcending value, would suppress negative appraisals of immigrants (Davidov et al. Citation2008; Schwartz Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2007a; Vecchione et al. Citation2012; Walsh, Tartakovsky, and Shifter-David Citation2019). Turning to the second hypothesis, a statistically significant interaction between the two self-transcending values was found in Belgium, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, and Spain. The presence of an interaction effect implies that, in the context of perceived immigrant threat, qualitative disparities between benevolence and universalism exist and they should receive wider attention. It is obvious that the addition of interaction terms, more often than not, did not offer a quantitative increase in our ability to explain variability in perceived threat. At the same time, it does offer valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms that govern these relationships. Substantively, it showcases that one way – by drawing firmer distinctions between those closest to us and the others – or the other – by creating conflicting loyalties – benevolence as a value priority qualifies the effect of universalism and tends to exacerbate negative evaluations of immigrants in these countries.

What becomes apparent is that, in the European context, one size does not fit all. Cultural and national backgrounds matter and we should be more mindful of these differences when we attempt to generalize. In contrast, it is clear that, as a widely employed higher-order construct, self-transcendence may be a slightly more psychometrically reliable option in several countries, but not a valid representor of how benevolence and universalism affect attitudes towards immigrants. Notwithstanding the limitations emanating from the problematic psychometric qualities of the lower-order values, the consistency of the pattern across national contexts allows little doubt of divergent effects: a universalistic value orientation indeed subdues negative evaluations of immigrants, but benevolence is likely to accentuate them.

Furthermore, it is important to recognize that a social identity is inferred instead of solidly measured as a starting, theoretical point. Which is this in-group whose members the participants value? While I control for several boundary-drawing factors, such as religiosity and political orientation, other group cues are lacking. For example, this study is not afforded a direct measure of national identification or attachment. Nor there was any way to define better who are “those around them.” Keeping the contact hypothesis (Allport Citation2008; Dixon Citation2006) in mind, some knowledge of people’s network composition could have enlightened why benevolence and universalism appear to deviate on how they influence anti-immigrant sentiments.

Conclusions

To what extent can we talk of overlapping loyalties to those closest to us and distant groups of people? Human values theory (Schwartz Citation1994) supports that benevolence and universalism do indeed coincide as value priorities within individuals. Social identity theory (Abrams and Hogg Citation1988; Tajfel and Turner Citation1979) claims that our commitment to the members of our in-group inhibits our capacity to promote outgroup interests. Hence, this “cohabitation” is not necessarily, psychologically harmonious or promotes a shared set of directives for intergroup interaction. The present study offers some evidence that benevolence often plays an opposite role than universalism or qualifies its relationship with perceived immigrant threat.

These findings set forth important ramifications. First, they help us revisit an extant body of work examining the role of human values – in particular, self-transcendence – in attitudes towards immigrants and immigration (e.g. Davidov et al. Citation2008; Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Kilburn Citation2009; Ramos and Vala Citation2009; Sapienza et al. Citation2010; See, Lim, and Pauketat Citation2020; Wolf, Weinstein, and Maio Citation2019). Given the present results, it seems that it is universalism, not self-transcendence per se, that tends to reduce anti-immigrant sentiments.Footnote7 It follows that, as researchers, we should be more mindful about our methodological choices to include higher- or lower-order values in our models, as they can affect our inferences and the accuracy of the conclusions we draw.

In an earlier section, I noted how a false dichotomy between self and others – a “me against the world” theorization of human mentality, if you will – can be counterproductive for our understanding of the role of benevolence in negative appraisals of immigrants. The same dichotomy is all but present in most threat-related immigration research. That is, we attempt to understand why individuals perceive immigrants the way they do based on individual-level (e.g. income, employment status, etc) or macro-level (e.g. GDP, unemployment rates, etc.) factors. At its core, this approach infers that people’s opinions and behaviours are predominantly responses to their personal interests and the ways these interests are affected by contextual conditions. But a large portion of human behaviour, including our fears, is driven by our care for our closest others (Decety Citation2014; Mesch Citation2000; Wuthnow Citation2012), as the results of this study also support. To that end, future research on the role of benevolence can be a useful complement to individualistic and collectivistic (e.g. nationalism) interpretations of immigrant threat.

Last, the present study showcases that the search for large-scale explanatory models might not be appropriate in all contexts. Most notably, the country by country analysis revealed how little individual-level factors linked to group conflict theories (including the two featured here) contribute to our understanding of perceived immigrant threat in some European societies. The models were able to explain only a small portion of the variation in countries like Poland, Slovenia, Hungary, Portugal, and Spain, while they were far more successful in conventional western countries. It goes without saying that I did not account for every possible predictor proposed by group conflict theories, but only for the more consistent. Nevertheless, the results suffice to imply that (a) group conflict theories impose a rather “west-Eurocentric” lens on the study of intergroup relations, and (b) they are less appropriate in recent immigrant destinations where native-immigrant relations are under formation. In several western European societies, the complex history of colonialism and long-term, cultural and economic interactions have contributed to the essentialisation of immigrants and host-immigrant affairs. On the contrary, eastern and southern European countries have fewer intercultural experiences and historical precedents of this sort, upon which their citizens can draw to interpret future outcomes of interethnic contact. It is likely that, at this early stage, xenophobic reactions to immigrants are less about tangible, realistic or symbolic threats and more akin to a phobia, or intergroup anxiety (Stephan and Stephan Citation1996): a generalized sense of uncomfortableness with immigrants that transcends social categories and cannot be neatly explained with the interpretive frameworks we would use in formalized types of threat. Following Ceobanu and Escandell’s (Citation2010) recommendation, the present study affirms the necessity of a major paradigm shift in future research, one that will pay closer attention to the formation of host-immigrant relations to non-western European societies and their distinct political trajectories, economic structures, religious traditions, and cultural modes of communication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This article is based on the dissertation “Our Own and the Others: What Happens to Perceptions of Immigrant Threat when Value Priorities Collide?”, submitted to the University of North Texas. 2019. UNT Digital Library: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1609152/.

2 The values are presented in order of adjacency in a circular structure. Tradition and benevolence are considered adjacent values.

3 Detailed description of the European Social Survey’s methodology, including information about survey specifications, sampling, data collection, and accompanying documentation can be found at the ESS website: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/.

4 The psychometric properties of these indices are somewhat problematic (universalism: .497 ≥ α ≤ .691; benevolence:.541 ≥ α ≤ .736). In the ESS human values instrument documentation, Schwartz (Citation2003) defends the lower reliability scores of the indices as a consequence of the measures’ breadth and validity.

5 For purposes of clarity, the results pertaining to the control variables are not reported here. Available upon request.

6 Examination of the scatterplots indicated that the assumptions of linearity, multivariate normality, and homoscedasticity were satisfied in all countries. No multicollinearity issues (VIF < 10 and tolerance > 0.20) were diagnosed. The Durbin-Watson test indicated that there was no first-order autocorrelation of the residuals. All values of the test were between 1.5 and 2.5. Multivariate outliers were identified with Mahalanobis distance. The probability of an observation’s MD being outside the conventional bounds of the chi-square normal distribution was calculated and was used to exclude potentially influential outliers before any analysis.

7 Note that universalism is typically represented with more items in the self-transcendence index than benevolence.

References

- Abrams, Dominic, and Michael A. Hogg. 1988. “Comments on the Motivational Status of Self-Esteem in Social Identity and Intergroup Discrimination.” European Journal of Social Psychology 18 (4): 317–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180403.

- Allport, Gordon W. 2008. The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Basic Books.

- Bardi, Anat, and Robin Goodwin. 2011. “The Dual Route to Value Change: Individual Processes and Cultural Moderators.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42 (2): 271–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110396916.

- Ben-Nun Bloom, Pazit, Gizem Arikan, and Gallya Lahav. 2015. “The Effect of Perceived Cultural and Material Threats on Ethnic Preferences in Immigration Attitudes.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (10): 1760–1778. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1015581.

- Bilsky, Wolfgang, Michael Janik, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2011. “The Structural Organization of Human Values-Evidence from Three Rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS).” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42 (5): 759–776. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110362757.

- Blalock, Hubert M. 1970. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York: Capricorn Books.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7.

- Bohman, Andrea, and Mikael Hjerm. 2014. “How the Religious Context Affects the Relationship Between Religiosity and Attitudes Towards Immigration.” Ethnic & Racial Studies 37 (6): 937–957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.748210.

- Bonacich, Edna. 1972. “A Theory of Ethnic Antagonism: The Split Labor Market.” American Sociological Review 37 (5): 547. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2093450.

- Brambilla, Marco, Simona Sacchi, Stefano Pagliaro, and Naomi Ellemers. 2013. “Morality and Intergroup Relations: Threats to Safety and Group Image Predict the Desire to Interact with Outgroup and Ingroup Members.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49 (5): 811–821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.04.005.

- Branscombe, Nyla R., Naomi Ellemers, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje. 1999. “The Context and Content of Social Identity Threat.” In Social Identity: Context, Commitment, Content, edited by Naomi Ellemers, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje, 35–55. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 1979. “In-Group Bias in the Minimal Intergroup Situation: A Cognitive-Motivational Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 86 (2): 307–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.307.

- Brown, Rupert. 2000. “Social Identity Theory: Past Achievements, Current Problems and Future Challenges.” European Journal of Social Psychology 30 (6): 745–778.

- Burhan, Omar K., and Esther van Leeuwen. 2016. “Altering Perceived Cultural and Economic Threats Can Increase Immigrant Helping: Immigrant Helping.” Journal of Social Issues 72 (3): 548–565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12181.

- Ceobanu, Alin M., and Xavier Escandell. 2010. “Comparative Analyses of Public Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration Using Multinational Survey Data: A Review of Theories and Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 309–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102651.

- Davidov, Eldad, and Bart Meuleman. 2012. “Explaining Attitudes Towards Immigration Policies in European Countries: The Role of Human Values.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 757–775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.667985.

- Davidov, Eldad, Bart Meuleman, J. Billiet, and P. Schmidt. 2008. “Values and Support for Immigration: A Cross-Country Comparison.” European Sociological Review 24 (5): 583–599. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn020.

- Davidov, Eldad, Bart Meulemann, Shalom H. Schwartz, and Peter Schmidt. 2014. “Individual Values, Cultural Embeddedness, and Anti-Immigration Sentiments: Explaining Differences in the Effect of Values on Attitudes Toward Immigration Across Europe.” KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie 66 (S1): 263–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-014-0274-5.

- Davidov, Eldad, Daniel Seddig, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Rebeca Raijman, Peter Schmidt, and Moshe Semyonov. 2020. “Direct and Indirect Predictors of Opposition to Immigration in Europe: Individual Values, Cultural Values, and Symbolic Threat.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 553–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550152.

- Decety, Jean. 2014. “The Neuroevolution of Empathy and Caring for Others: Why It Matters for Morality.” In New Frontiers in Social Neuroscience, edited by Jean Decety, and Yves Christen, 127–151. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02904-7_8.

- Dixon, Jeffrey C. 2006. “The Ties That Bind and Those That Don’t: Toward Reconciling Group Threat and Contact Theories of Prejudice.” Social Forces 84 (4): 2179–2204.

- Erisen, Cengiz, and Cigdem Kentmen-Cin. 2017. “Tolerance and Perceived Threat Toward Muslim Immigrants in Germany and the Netherlands.” European Union Politics 18 (1): 73–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516675979.

- Esses, Victoria M., Lynne M. Jackson, and Tamara L. Armstrong. 1998. “Intergroup Competition and Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration: An Instrumental Model of Group Conflict.” Journal of Social Issues 54 (4): 699–724.

- European Social Survey Cumulative File, ESS 1-8. 2018. Data file edition 1.0. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway - Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. doi:10.21338/NSD-ESS-CUMULATIVE.

- Gorodzeisky, Anastasia, and Moshe Semyonov. 2016. “Not Only Competitive Threat but Also Racial Prejudice: Sources of Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in European Societies.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 28 (3): 331–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edv024.

- Grigoropoulou, Nikolitsa. 2019. DISSERTATION. “Our Own and the Others: What Happens to Perceptions of Immigrant Threat when Value Priorities Collide?” University of North Texas, UNT Digital Library. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1609152/.

- Hitlan, Robert T., Kimberly Carrillo, Michael A. Zárate, and Shelley N. Aikman. 2007. “Attitudes Toward Immigrant Groups and the September 11 Terrorist Attacks.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 13 (2): 135–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10781910701270970.

- Hogg, Michael A., and Scott A. Reid. 2006. “Social Identity, Self-Categorization, and the Communication of Group Norms.” Communication Theory 16 (1): 7–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00003.x.

- Hogg, Michael A., and Deborah J. Terry. 2000. “Social Identity and Self-Categorization Processes in Organizational Contexts.” Academy of Management Review 25 (1): 121. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/259266.

- Hornsey, Matthew J. 2008. “Social Identity Theory and Self-Categorization Theory: A Historical Review.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2 (1): 204–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x.

- Kilburn, H. Whitt. 2009. “Personal Values and Public Opinion*.” Social Science Quarterly 90 (4): 868–885. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00667.x.

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2013. “Labor Market Competition and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment: Occupations as Contexts.” International Migration Review 47 (3): 643–685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12046.

- Leong, Chan-Hoong, and Colleen Ward. 2011. “Intergroup Perceptions and Attitudes Toward Immigrants in a Culturally Plural Society: Attitudes Towards Immigrants.” Applied Psychology 60 (1): 46–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2010.00426.x.

- Linden, Meta van der, and Laura Jacobs. 2017. “The Impact of Cultural, Economic, and Safety Issues in Flemish Television News Coverage (2003–13) of North African Immigrants on Perceptions of Intergroup Threat.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (15): 2823–2841. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1229492.

- Lubbers, Marcel, Marcel Coenders, and Peer Scheepers. 2006. “Objections to Asylum Seeker Centres: Individual and Contextual Determinants of Resistance to Small and Large Centres in the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 22 (3): 243–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci055.

- Mangum, Maruice, and Ray Block. 2018. “Social Identity Theory and Public Opinion Towards Immigration.” Social Sciences 7 (3): 41. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7030041.

- Mesch, Gustavo S. 2000. “Women’s Fear of Crime: The Role of Fear for the Well-Being of Significant Others.” Violence and Victims 15 (3): 323–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.15.3.323.

- Meuleman, Bart, Koen Abts, Peter Schmidt, Thomas F. Pettigrew, and Eldad Davidov. 2020. “Economic Conditions, Group Relative Deprivation and Ethnic Threat Perceptions: A Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 593–611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550157.

- Murray, Kate E., and David M. Marx. 2013. “Attitudes Toward Unauthorized Immigrants, Authorized Immigrants, and Refugees.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 19 (3): 332–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030812.

- Pichler, Florian. 2010. “Foundations of Anti-Immigrant Sentiment: The Variable Nature of Perceived Group Threat Across Changing European Societies, 2002-2006.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 51 (6): 445–469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715210379456.

- Quillian, Lincoln. 1995. “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe.” American Sociological Review 60 (4): 586. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2096296.

- Ramos, Alice, and Jorge Vala. 2009. “Predicting Opposition Towards Immigration: Economic Resources, Social Resources and Moral Principles.” In Quod Erat Demonstrandum: From Herodotus’ Ethnographic Journeys to Cross-Cultural Research: Proceedings from the 18th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, edited by Aikaterini Gari, and Kostas Mylonas, 11. Athens, Greece: Pedio Books Pub.

- Riek, Blake M., Eric W. Mania, and Samuel L. Gaertner. 2006. “Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Personality & Social Psychology Review (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates) 10 (4): 336–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4.

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York, NY, US: Free Press.

- Sagiv, Lilach, Sonia Roccas, Jan Cieciuch, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2017. “Personal Values in Human Life.” Nature Human Behaviour 1 (9): 630–639. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0185-3.

- Sapienza, Irene, Zira Hichy, Maria Guarnera, and Santo Di Nuovo. 2010. “Effects of Basic Human Values on Host Community Acculturation Orientations.” International Journal of Psychology 45 (4): 311–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00207591003587978.

- Saroglou, Vassilis, Bahija Lamkaddem, Matthieu Van Pachterbeke, and Coralie Buxant. 2009. “Host Society’s Dislike of the Islamic Veil: The Role of Subtle Prejudice, Values, and Religion.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33 (5): 419–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.02.005.

- Schlueter, Elmar, Bart Meuleman, and Eldad Davidov. 2013. “Immigrant Integration Policies and Perceived Group Threat: A Multilevel Study of 27 Western and Eastern European Countries.” Social Science Research 42 (3): 670–682. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.12.001.

- Schlueter, Elmar, and Peer Scheepers. 2010. “The Relationship Between Outgroup Size and Anti-Outgroup Attitudes: A Theoretical Synthesis and Empirical Test of Group Threat- and Intergroup Contact Theory.” Social Science Research 39 (2): 285–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.07.006.

- Schneider, S. L. 2007. “Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 24 (1): 53–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm034.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1994. “Are There Universal Aspects in the Structure and Contents of Human Values?” Journal of Social Issues 50 (4): 19–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2003. “A Proposal for Measuring Value Orientations Across Nations.” Questionnaire Development Package of the European Social Survey, 259–319. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/methodology/core_ess_questionnaire/ESS_core_questionnaire_human_values.pdf.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2007a. “Value Orientations: Measurement, Antecedents and Consequences Across Nations.” In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey, edited by Roger Jowell, Caroline Roberts, Rory Fitzgerald, and Gillian Eva, 169–203. London, UK: SAGE Publications, Ltd. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209458.n9.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2007b. “Universalism Values and the Inclusiveness of Our Moral Universe.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 38 (6): 711–728. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107308992.

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Wolfgang Bilsky. 1987. “Toward a Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53 (3): 550–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550.

- Schwartz, Shalom H, and Klaus Boehnke. 2004. “Evaluating the Structure of Human Values with Confirmatory Factor Analysis.” Journal of Research in Personality 38 (3): 230–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00069-2.

- Sears, David O. 1988. “Symbolic Racism.” In Eliminating Racism: Profiles in Controversy, edited by Phyllis A. Katz, and Dalmas A. Taylor, 53–84. Perspectives in Social Psychology. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- See, Ya Hui Michelle, Aaron Wei Qiang Lim, and Janet V. T. Pauketat. 2020. “Values Predict Willingness to Interact with Immigrants: The Role of Cultural Ideology and Multicultural Acquisition.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 51 (1): 3–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022119883018.

- Semyonov, Moshe, Rebeca Raijman, and Anastasia Gorodzeisky. 2006. “The Rise of Anti-Foreigner Sentiment in European Societies, 1988–2000.” American Sociological Review 71 (3): 426–449. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100304.

- Sherif, Muzafer. 1967. Group Conflict and Cooperation: Their Social Psychology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Sniderman, Paul M., Louk Hagendoorn, and Markus Prior. 2004. “Predisposing Factors and Situational Triggers: Exclusionary Reactions to Immigrant Minorities.” American Political Science Review 98 (1): 35–49.

- Steinmetz, Holger, Peter Schmidt, Andrea Tina-Booh, Siegrid Wieczorek, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2009. “Testing Measurement Invariance Using Multigroup CFA: Differences Between Educational Groups in Human Values Measurement.” Quality & Quantity 43 (4): 599–616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9143-x.

- Stephan, Walter G., and Lausanne C. Renfro. 2002. “The Role of Threat in Intergroup Relations.” In From Prejudice to Intergroup Emotions: Differentiated Reactions to Social Groups, edited by Diane M. Mackie, and Eliot R. Smith, 191–207. New York: Psychology Press.

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie White Stephan. 1996. “Predicting Prejudice.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 20 (3–4): 409–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00026-0.

- Stephan, Walter G., Oscar Ybarra, Carmen Martinez Martinez, Joseph Schwarzwald, and Michal Tur-Kaspa. 1998. “Prejudice Toward Immigrants to Spain and Israel: An Integrated Threat Theory Analysis.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 29 (4): 559–576.

- Stets, Jan E., and Peter J. Burke. 2000. “Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.” Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (3): 224. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870.

- Stupi, Elizabeth K., Ted Chiricos, and Marc Gertz. 2016. “Perceived Criminal Threat from Undocumented Immigrants: Antecedents and Consequences for Policy Preferences.” Justice Quarterly 33 (2): 239–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2014.902093.

- Tajfel, Henri. 1979. “Individuals and Groups in Social Psychology*.” British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 18 (2): 183–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1979.tb00324.x.

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by Stephen Worchel, and William G Austin, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Turner, John C. 1975. “Social Comparison and Social Identity: Some Prospects for Intergroup Behaviour.” European Journal of Social Psychology 5 (1): 1–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420050102.

- Turner, John C, Michael A. Hogg, Penelope J. Oakes, Stephen D. Reicher, and Margaret S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Vecchione, Michele, Gianvittorio Caprara, Harald Schoen, Josè Luis Gonzàlez Castro, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2012. “The Role of Personal Values and Basic Traits in Perceptions of the Consequences of Immigration: A Three-Nation Study: Values, Traits, and Perceptions of Immigration.” British Journal of Psychology 103 (3): 359–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02079.x.

- Vugt, Mark Van, and Claire M. Hart. 2004. “Social Identity as Social Glue: The Origins of Group Loyalty.” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 86 (4): 585–598.

- Wallace, Michael, and Rodrigo Figueroa. 2012. “Determinants of Perceived Immigrant Job Threat in the American States.” Sociological Perspectives 55 (4): 583–612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2012.55.4.583.

- Walsh, Sophie D., Eugene Tartakovsky, and Monica Shifter-David. 2019. “Personal Values and Immigrant Group Appraisal as Predictors of Voluntary Contact with Immigrants among Majority Students in Israel.” International Journal of Psychology 54 (6): 731–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12531.

- Westen, Drew. 2009. Immigrating from Facts to Values: Political Rhetoric in the US Immigration Debate. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

- Winders, Jamie. 2014. “New Immigrant Destinations in Global Context.” International Migration Review 48 (1_suppl): 149–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12140.

- Wojcieszak, Magdalena, and R. Kelly Garrett. 2018. “Social Identity, Selective Exposure, and Affective Polarization: How Priming National Identity Shapes Attitudes Toward Immigrants Via News Selection.” Human Communication Research 44 (3): 247–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqx010.

- Wolf, Lukas J., Netta Weinstein, and Gregory R. Maio. 2019. “Anti-Immigrant Prejudice: Understanding the Roles of (Perceived) Values and Value Dissimilarity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 117 (5): 925–953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000177.

- Wright, Matthew. 2011. “Diversity and the Imagined Community: Immigrant Diversity and Conceptions of National Identity.” Political Psychology 32 (5): 837–862. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00843.x.

- Wuthnow, Robert. 2012. Acts of Compassion: Caring for Others and Helping Ourselves. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Yuki, Masaki. 2003. “Intergroup Comparison Versus Intragroup Relationships: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Social Identity Theory in North American and East Asian Cultural Contexts.” Social Psychology Quarterly 66 (2): 166. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1519846.