ABSTRACT

Migration research developed significantly in the past decades. However, with the life course approach and the concept of transnational migration, there are still two different, as yet largely unconnected conceptual perspectives on migration. Both approaches have their merits but also their shortcomings. This paper tries to overcome these shortcomings by combining the advantages of both perspectives to suggest a unified theoretical concept of transnational life courses (TNLC). TNLC builds on the multidimensional understanding of transnational migration research that (potential) migrants live in multiple social and cultural spaces leading to parallel assimilation and dissimilation processes. This perspective is merged with the life course approach with its chronologically ordered understanding of causality relying on preceding determinants and subsequent outcomes in form of events and periods. Based on data provided by the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS) some simple empirical analyses were conducted to illustrate the potential of the TNLC approach.

Introduction

During recent decades migration research has made tremendous progress. Our theoretical as well as our empirical knowledge about spatial mobility, its determinants and consequences have increased constantly (Gold and Nawyn Citation2019). In this context, two theoretical approaches aimed at better understanding migration have gained in importance. The first one investigates migration from a life course perspective and focuses particularly on the actual event of crossing a (national) border as a reference point for dynamic and causal analyses (see Section “Migration research and the life course approach” for details). The second one, on the contrary, relaxes the meaning of the singular event of border crossing and emphasizes that migration not only takes place in geographic spaces but also in transnational social spaces, which means that spatial mobility across legal or administrative borders is embedded in cultural spaces as well as in social networks (see Section “Transnational migration research” for details).

I think that contemporary migration theory has already developed all ingredients that are needed for a comprehensive understanding of the causes and consequences of migration as a complex and relevant social phenomenon. However, these ingredients unfortunately are scattered among different theoretical approaches and schools: “Our understanding of migration is handicapped by fragmentation of research and training along disciplinary lines and inadequate measurements. We need a comprehensive approach to migration and a central understanding that transcends disciplinary boundaries” (Willekens et al. Citation2016, 897). In addition, Jong and Valk (Citation2020, 1776) pointed out: “It is much needed to better integrate expectations derived from international migration theories with the life course approach, which also alludes to the importance of origin and destination in migration choices.” I think that it is worth trying to tackle this challenge by formulating a unified theoretical concept that should better frame the complex process of migration and that mainly consists of ideas and arguments from both the life course approach and the transnational migration approach. Such a new paradigm could overcome the specific weaknesses of each of these two largely isolated concepts and could recognize and utilize the advantages and merits of both approaches. Against this background, this paper presents an attempt to formulate a new theoretical concept developed with the goal of integrating the life course approach and the concept of transnational migration into a unified paradigm of migration research.

Independent of certain theoretical perspectives, schools or traditions, migration research is interested in the determinants of migration and the consequences of spatial mobility on individuals, communities, or societies. In this respect, determinants and consequences are two different analytical perspectives from which migration research tries to improve our knowledge and understanding of ongoing migration processes (Levitt and Jaworsky Citation2007; Wingens et al. Citation2011b). If researchers focus on migration determinants, they are particularly interested in the conditions that increase or decrease the occurrence of migration as a societal phenomenon. In contrast, if they focus on the consequences of migration, researchers are more interested in questions regarding integration or assimilation of migrants. The life course approach as well as transnational migration research as the two major theoretical concepts in contemporary migration research have in common that they are interested in determinants and also consequences of spatial mobility. However, the approaches differ fundamentally in how they conceptualize migration processes. Against this background the current paper proceeds as follows: In the first two sections, the life course approach in migration research and the concept of transnational migration are summarized. Building on this, Section “Towards a unified concept: the transnational life course (TNLC)” introduces the arguments for the Transnational Life Course approach (TNLC) as a unified concept for migration research. To illustrate how TNLC can stimulate empirical research, Section “TNLC in empirical practice” presents a brief example of application analysing data from the new and unique German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS). The paper ends with a discussion and conclusions (Section “Discussion and conclusion”).

Migration research and the life course approach

During the recent past, migration research has been increasingly influenced by the life course approach (cf. Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe Citation2004; Mayer Citation2009). In a life course perspective migration is not understood as a singular event of moving abroad, but as a process of decision-making, actual migration and integration and possibly return or onward migration. This process is affected by migrants’ previous experiences in the past, as well as by currently available individual resources. In addition, the migration process and its outcomes are correlated to dynamic changes in contextual parameters. Finally, the life course approach also stresses mutual interdependencies between the life courses of interacting individuals (“linked lives”) as an explanation for individual migration decisions and behaviour (cf. Mulder and Hooimeijer Citation2012; Geist and McManus Citation2008; Kley Citation2011; Wingens et al. Citation2011a; Coulter and Scott Citation2015).

Interestingly life course-related migration research is usually separated in two heretofore mainly unconnected strands along the question regarding the determinants and the consequences of migration:

The first strand is interested in the migration decision process and focuses on the period before people leave a region or a country (cf. Jong and Gardner Citation1981; Arango Citation2000). Here the migration process is often conceptualized in the form of stage models (for an extensive literature review about different stage models as well as related empirical findings see Kley Citation2011). Referring to psychological theories of decision-making and planned behaviour (Heckhausen and Gollwitzer Citation1987) one can suggest, for example, a simple two-stage model of migration. In this model, the first stage covers the period of considering migration, which ends with the individual decision to migrate. After the migration decision has been made a period follows in which the move is planned and arranged. This second stage is then completed by the actual event of migration. Although such stage models are really helpful in disentangling the complex migration decision and preparation process theoretically (Coulter and Scott Citation2015), there are only a few empirical works that explicitly refer to such a stage framework (e.g. Kley Citation2011; Erlinghagen Citation2016). Moreover, the majority of the empirical work in life course-related migration research aim on changes in objective living conditions like income, employment status, family status, or housing situation (see for example Böheim and Taylor Citation2002; Clark and Ledwith Citation2006; Geist and McManus Citation2008; Flippen Citation2014; Lübke Citation2015). A smaller number of analyses concentrate on the relationship between psychological stressors like housing dissatisfaction (e.g. Wolpert Citation1966; Speare Citation1974; Bach and Smith Citation1977; Newman and Duncan Citation1979; Landale and Guest Citation1985; Clark and Ledwith Citation2006) or overall subjective well-being (e.g. Nowok et al. Citation2013; Ivlevs Citation2015; Erlinghagen Citation2016).

The second strand of life course-related migration research concentrates particularly on the assimilation or integration of migrants in their new environment after arrival (e.g. Schneider and Crul Citation2010). In this perspective periods before arrival often play a role only as determinants for a more or less successful integration or assimilation in different dimensions (Gordon Citation1964; Alba and Nee Citation1997) measured by an inter-personal comparison between migrants and the autochthonic population (e.g. Ager and Strang Citation2008). Such work has asked, for example, if there is ethnical segregation (e.g. Mouw and Entwisle Citation2006; Bolt, Özüekren, and Phillips Citation2010), how migrants perform in the labour market (e.g. Drinkwater, Eade, and Garapich Citation2009; Luthra Citation2013), if migrants suffer from higher poverty rates (e.g. Barrett and Maître Citation2013; Thomas Citation2015), or if there are differences in such measures of integration between migrants from different ethnic origins (e.g. Dribe and Lundh Citation2008).

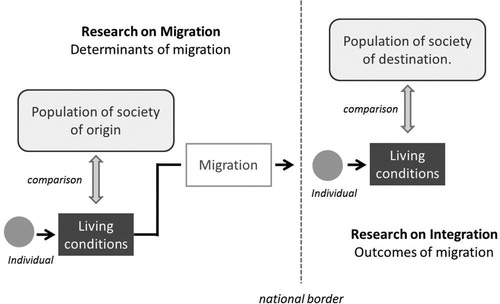

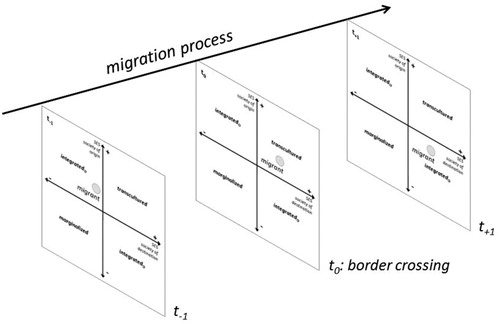

summarizes the main perspectives of migration research in a life course perspective. Although it is claimed from a conceptual perspective that migration is a continuing process in individuals’ life courses, the related research is actually often fragmented into research on migration determinants (migration decision) and research on migration consequences (integration or assimilation) around the event of crossing national borders. In that sense, life course-related migration research has tried to identify determinants of individual migration particularly by comparing migrants’ living conditions in advance of their emigration with the living conditions of the (non-mobile) population of their home country (society of origin). In contrast, life course-related migration research has tried to identify outcomes of individual migration by comparing migrants’ living conditions after the event of border crossing (immigration) with the living conditions of the population of the host country (society of destination). In this respect, in its strictness the event of border crossing marks an artificial division between periods before and after migration although all this happens within a single individual life course with all its complex interrelations among time, space, and different life domains. Paradoxically, this often leads to an almost exclusive concentration on fixed individuals’ migration status as either (future) emigrants or (past) immigrants as reference points for migration research (Dahinden Citation2016).

Transnational migration research

There is no doubt that life course-related migration research has provided important, new insight into causes and consequences of migration. But the life course-related migration research de facto broadly neglects migration as an unfinished and steadily ongoing process by concentrating only on an isolated part of the whole process artificially separated by the event of border crossing. Since the 1990s, more and more researchers have called the dominating focus on the event of physical border crossing into question. They have argued that crossing borders is without a doubt an important event but that migration as a process starts much earlier in migrants’ life courses and is not finished at the time of arrival in the destination region or country. Instead, it is argued that migration research has to recognize different kinds of connections and ties migrants have to people or institutions in their old as well as their new homes irrespective of the actual moving event (Glick Schiller, Basch, and Blanc-Szanton Citation1992; Smith and Guarnizo Citation1998; Portes, Guarnizo, and Landolt Citation1999; Levitt and Jaworsky Citation2007).

This transnational perspective tried to overcome the overemphasis of the nation state as the relevant subordinated determinant of individuals’ behaviour and living conditions (“national container”). As a consequence of this critique on what some authors have described as “methodological nationalism” (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002), two different perspectives have become established under the heading of the “transnational migration approach” in the subsequent years. The first perspective has taken a primary interest in concrete transnational practices like membership in migrant organizations or activities in migrant political movements (e.g. Itzigsohn et al. Citation1999; Guarnizo, Portes, and Haller Citation2003; Østergaard-Nielsen Citation2003) as well as the interrelationship between institutions and organizations (e.g. families, firms) and the migration process (e.g. Lima Citation2001; Cohen Citation2011; Weiß and Mensah Citation2011). In contrast, the second perspective has focused on the identification of (imaginary) transnational social and cultural spaces or “fields” that are (at least partly) independent of political or legal (nation state) borders (e.g. Faist Citation2000a, Citation2000b; Levitt and Glick Schiller Citation2004; Pries Citation2005). With respect to these two perspectives on transnational migration, Levitt and Glick Schiller (Citation2004) distinguished “ways of belonging” and “ways of being” (see also Glick Schiller Citation2003)

Ways of being refers to the actual social relations and practices that individuals engage in rather than to the identities associated with their actions. […] In contrast, ways of belonging refers to practices that signal or enact an identity which demonstrates a conscious connection to a particular group. (Levitt and Glick Schiller Citation2004, 1010)

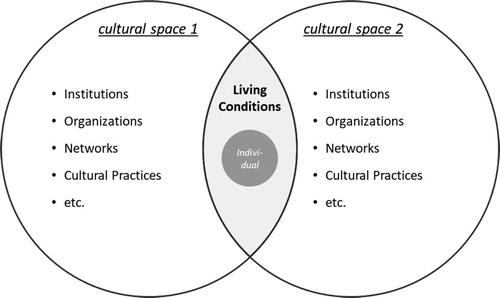

shows a visualization of the main idea of the transnational approach in migration research. Individuals belong to different cultural spaces at the same time. This “simultaneity” (Tsuda Citation2012) should particularly hold true for migrants who – by definition – move geographically from one location to another. Spatial mobility is more or less connected with changing contexts. But this does not mean that migrants totally leave their “old” contexts and are immediately absorbed by the “new” contexts in the destination country or region. Transnational migration research stresses that society is not congruent with nation states and its borders. Instead, all people in general and migrants in particular regularly belong to different contexts (“social fields”) at the same time. Such social fields are built up from institutions, organizations, networks, and social practices. Thus, migrants are simultaneously connected to the cultural space of their origin and of their destination, which in combination shape their individual living conditions ().

The shift away from the dichotomous understanding of migration determined by the actual event of border crossing towards the idea of transnational overlapping social spaces has strongly promoted migration research. But these merits should not hide certain weaknesses or limits of the transnational approach. From my perspective, the main problem with transnational approaches is the lack of any chronological frame of reference. The timing of events and the duration of certain states plays almost no role within that concept. Thus, in the transnational migration perspective determinants and consequences of migration become a blurred amalgam. As a result, transnational migration research can possibly describe specific settings migrants live in but it is inevitably not able to conduct any kind of (causal) analysis of the interrelation between determinants and outcomes of migration.

Towards a unified concept: the transnational life course (TNLC)

Transnational migration and social spaces

A good starting point for the development of a unified concept of transnational life courses is the work of Berry (e.g. Berry Citation1974, Citation1997, Citation2001) on acculturation. Interested in the psychological process of acculturation, he has stressed that migrants undergo two parallel developments after arrival in the host society. On the one hand, there is an ongoing and maybe growing need, expectation, or desire to adapt to the new and unknown host culture; on the other hand, there is need, expectation, or desire to preserve at least certain elements of the familiar culture of origin (see also Yinger Citation1981). Berry has presented four possible states for migrants:

Migrants who have adapted to the host culture but have also preserved their own cultural heritage could be described as “integrated”;

Migrants could be described as “assimilated” if they have adapted to the host culture and have given up their cultural heritage;

If migrants have not adapted to the host culture but still follow their cultural origins, they could be described as “separated”; and

Finally, if migrants are neither connected to the culture of their new home nor to the culture of their origin, they are socially excluded and could be described as “marginalized”.

Berry’s psychological argument that people can indeed be geographically localized in a single place (e.g. a certain nation state) but that they cannot be unequivocally assigned to a single cultural space (e.g. society) anticipates one of the most important arguments of transnational sociology that was formulated much later. Nevertheless, Berry concentrated only on acculturation, which means that he was not primarily interested in the time before the event of immigration in a certain nation state. Thus, although he helped to overcome the “container perspective”, his perspective was still bound to the conceptual separation of migration research on the on hand and integration research on the other hand (see Section “Migration research and the life course approach”).

As a further development, FitzGerald (Citation2012) relaxed the fixation of the event of border crossing as a starting point of acculturation. Instead, he stressed that from a sociological perspective migration is a process that can be characterized by permanent moves in at least two different cultural spaces. On one hand, a migrant lives in his or her culture of origin, and on the other hand, he or she lives in the culture of destination. The event of border crossing mostly does not coincide with a permanent switch from one culture to another. Rather, the migration process can be characterized by a more or less ongoing process of assimilation in the “new” cultural space of the society of destination and by a parallel more or less ongoing process of dissimilation from the “old” cultural space of the society of origin. FitzGerald (Citation2012) stressed that assimilation and dissimilation can be parallel processes and that the whole process is not structured by the single event of border crossing. Thus, dissimilation could, for example, have already begun while an individual (still) lives in his or her home country. Dissimilation in that sense could be a cause of the individuals’ decision to migrate and not (only) a consequence that migrants have to face after they have arrived in and while they stay in a new home society. The same holds true for assimilation: Assimilation does not necessarily start after an individual has crossed a certain geographical border. It is possible that individuals start assimilation to a certain cultural space even before they actually migrate to another country, for example by learning the language of the destination country in advance.

Berry as well as FitzGerald mainly concentrated on what Levitt and Glick Schiller (Citation2004) described as the “way of belonging” that aims at the (formal and informal) institutional settings in which migrants are embedded. They are not dealing with the “ways of being”, which refers to the “actual social relations and practices that individuals engage in” (Levitt and Glick Schiller Citation2004, 1010). Nevertheless, the conceptual idea of Berry and FitzGerald about assimilation and dissimilation can easily be transferred to the perspective of transnational migration research on social relations and practices. However, in accordance with critique from Lucassen (Citation2006) as well as from Waldinger and FitzGerald (Citation2004), it is always necessary to specify what is meant if talking about transnational ways of being. In the following and in contrast to the common focus, the understanding of transnational social relations and practices do not focus on “transnational engagement” (Tsuda Citation2012, 634) as “lived realities” like traditions or habits (e.g. membership in transnational organizations), but on available individual resources and their variable valuation in the context of different social fields (e.g. in the context of the origin or the host country or society). How people (inter)act and, therefore, their way of being is a matter of their available resources, namely their economic capital (Marx [Citation1867] Citation1962), their human capital (Becker Citation1964; Mincer Citation1962), and their social capital (Granovetter Citation1973; Burt Citation1992). If individuals’ Socio-Economic Status (SES) is understood as a product of individuals’ resources, the term “ways of being” is strongly connected with the social position of an individual and is, therefore, strongly related to his or her SES. However, the value of resources can depend on the context in which a resource should or can be used and as a result there is no single individual SES, but rather multiple, context-specific SESs can be suggested (Nieswand Citation2011; Weiß Citation2017). With regard to migrants, it could be that the SES in the country of origin is higher compared to the SES a migrant has to expect in a certain destination country. Whether and how much the individual SES differs depends on transnational and transcultural transferability of capital, which should be comparably easy for economic capital but more problematic with regard to human capital (e.g. Chiswick and Miller Citation2009) and particularly with regard to social capital (e.g. Mulder and Malmberg Citation2014).

At this point, I have to clarify briefly what is meant by “culture” in the following argumentation. This is necessary because culture is one of the most important terms and concepts in social sciences, but at the same time there is no common definition or understanding about what culture is or should be (Smith Citation2016). In the following, I understand culture as “shared cognitions, values, norms and expressive symbols” (DiMaggio Citation1994, 27). In this regard, Hofstede and McCrae (Citation2004, 58) have spoken of culture as “collective programming of the mind”, noting further “that culture is (a) a collective, not individual, attribute; (b) not directly visible but manifested in behaviours; and (c) common to some but not all people”. Thus culture is “a tool kit of symbols, stories, rituals, and world-views, which people may use in varying configurations to solve different kinds of problems” (Swidler Citation1986, 273).

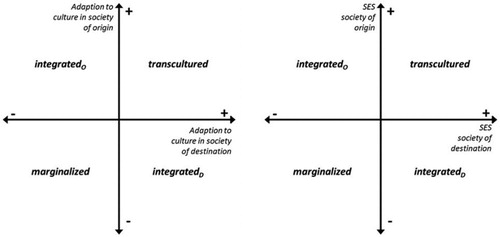

All this leads to the next step towards a new, unified concept: Both subjective beliefs (emotions) and objective status (resources) as important features of social inequality can now be framed within what I would like to call Modified Berry Boxes (MBB). Starting with the graph on the left side of , the two different axes represent how strongly a (potential) migrant is adapted to the culture of the society of his or her origin (O) and at the same time to the culture of the society of his or her (possible) destination (D) (“ways of belonging”). If people are mainly adapted to the culture of one of the two societies (O or D), they can be described as integrated (: integratedO vs. integratedD). If people are neither adapted to the culture in their society of origin nor to the culture in their society of their (possible) destination, they are marginalized. Finally, if a migrant is adapted to the culture in his or her society of origin as well as to the culture in his or her society of destination, the migrant can be described as transcultured. The same perspective can be transferred to SES as an important source for intercultural practices (“ways of being”) (see the right side in ). If people are not deprived in mainly one specific societal context, they can be classified as integrated. If migrants are deprived in both societal settings (origin and destination), they are marginalized. Again, if migrants are neither deprived in their society of origin nor in their society of destination, they are transcultured in this sense. Thus, comparable to the idea of “four types of transnational simultaneity” (Tsuda Citation2012, 636), the MBBs in represent the idea of a simple ideal-typical two-dimensional social space with four quadrants individuals can be located in, either through their subjective beliefs or through their objective SES. Moreover, I deliberately avoid the term “social field” and prefer to use the term “social space” instead, even though transnational migration research has often talked about “social fields” to stress the independence of national boundaries and the transnational power of culture or transnational existence of interpersonal relationships (see for example Levitt and Glick Schiller Citation2004, 1008f). Given the difficult, complex, and heterogeneous debate about the term “field” in the social sciences (Martin Citation2003), I have decided that it would be better to talk about social space here instead. Social space in this sense does only mean that the social position of an individual can be defined via his or her coordinates in a two-dimensional (n-dimensional) coordinate system with regard to a certain social reference system (like culture) or important social categories (like SES).

To avoid misunderstandings, I believe that at this point it is very important to introduce what I mean by “ideal-typical”. The concept of ideal types (“Idealtypen”) goes back to Max Weber. Weber argued that the over-complex world we are all living in can be better analysed if researchers reduce complexity. This reduction can be reached by a classification of ideal types that stress the main features of a phenomenon. “As in the case of every generalizing science the abstract character of the concepts of sociology is responsible for the fact that, compared with historical reality, they are relatively lacking in fullness of concrete content. To compensate for this disadvantage, sociological analysis can offer a greater precision of concepts.” (Weber quoted from Lindbekk Citation1992, 293). Following Swedberg the concept of ideal types can be used by sociologists for different purposes:

Weber […] says […] that the ideal type can be of general help to the sociologist in primarily three ways. It can be used (1) for terminological purposes, (2) for heuristic purposes, and (3) for classificatory purposes […]. The most important of these is in my view (2) or the use of the ideal type to come up with new ideas. Clarity is always important, and classifications are useful, but the heart of a good sociological analysis consists of coming up with new ideas in analyzing social reality, verified by the facts. (Swedberg Citation2018, 189f)

In this respect MBBs with its two dimensions and four quadrants should be understood as a first ideal-typical attempt to formulate the new idea of the TNLC approach to overcome the theoretical container perspective caused by the – in my view – artificial theoretical dualism of life course approach and the transnational perspective in migration research. It is also worth noting that the four quadrants are visualizing continuums with people in each single quadrant as more or less marginalized, more or less integrated, and more or less transcultured. In the end, of course, any empirical analysis has to operationalize such ideal-typical classifications, which implies that some kind of reasonable threshold has to be made by the researcher to assign an observed single case to one of the theoretically founded classes – whether qualitative or quantitative research methods are in use.

Migration, social space, and time

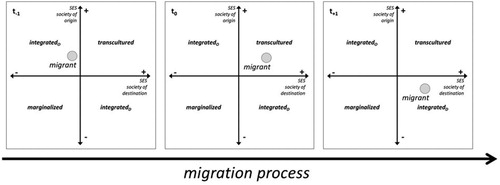

The MBBs from illustrated that it is possible to determine the current social position of a potential migrant at any time during the migration process with regard to at least two different reference frames: the society of destination (D) as well as the society of origin (O). As described above, this is possible in terms of objective social status (SES or its components) and in terms of subjective values and beliefs. In the following, I concentrate on objective social status in form of SES to enhance our perspective from a static (cross-sectional) view to a dynamic (longitudinal) perspective. Using MBBs in a dynamic (longitudinal) life course perspective represents the core of the TNLC idea. This can be illustrated by the following example. presents three MBBs representing three different points in time (t−1, t0, t+1). In all three MBBs, the social position of an individual in terms of SES in the (current) society of origin and SES in the (possible) society of destination is marked by a big grey dot. As can be seen the social position of this individual changes over the course of the migration process. At t−1 the individual has an above-average SES with respect to his or her society of origin (SESO) and a below-average SES with respect to his society of destination (SESD). Thus, he or she can be regarded as integrated in his or her society of origin. Think, for example, of a physician who is well established in her society of origin but who possibly would have difficulties finding a job in another country because of language barriers. In this example, as time goes by the (relative) SES changes at t0: Maybe the physician has successfully passed a certain qualification program (e.g. language training) that has improved her chances to use her professional skills in the destination context. As a result, she still has an above-average SESO but now also shows an above-average SESD. Therefore, she can be categorized as transnationalized in this respect. Then in t+1 the (relative) SESO changes again: The physician still has an above-average SESD but now shows a below-average SESO, perhaps because she has missed certain regular examinations that are legally required in her society of origin to maintain her professional license. This means that in t+1 the physician can now be rated as integrated in her society of destination. The example has illustrated that TNLC enables conceptualization of causal processes of transnational migration because of the directionality of the time line by bringing MBBs in a chronological order ().

TNLC in empirical practice

The aim of the paper is to introduce TNLC as a new theoretical concept for migration research. The paper is not interested in presenting some sophisticated empirical analyses to proof certain theoretically derived hypotheses although the following paragraph presents some new empirical results. It is very important to note that these very simple, descriptive empirical findings are introduced first and foremost to illustrate and outline how and under which conditions TNLC can be applied in empirical practice. Comparable to first rough sketches in art that do not reach the complexity and acuteness of a later painting the following empirical analyses should inspire and stimulate future progress in both quantitative but also qualitative empirical research. Moreover, the concept of TNLC is a model rather than a theory as such. Following Popper ([Citation1959] Citation2008), a theory has the aim to explain and to predict certain phenomenon. In that sense, TNLC does not explain anything by itself but provides a framework in which researchers could integrate already existing partial theories that aim to explain certain determinants and outcomes of migration.

Data

For the TNLC approach to be applied to empirical migration research, data that meet certain criteria and quality standards are needed. In the following, I concentrate on a quantitative perspective, although TNLC could undoubtably also be successfully applied to qualitative empirical migration research. Multiple-sited studies like Hagan, Rubén, and Demonsant (Citation2015); studies presenting investigation of the reconstruction of time-dependent, migration-related processes like Nohl et al. (Citation2014); or mixed-method studies like Liversage and Jakobsen (Citation2016) are good examples for already existing, TNLC-compatible qualitative research. The most important data requirement of TNLC measurement of the fluidity and circularity of migration. To investigate an ongoing process like migration means to implement a continuous measurement of individual status, decisions, and behaviour in a transnational perspective. Thus, longitudinal observations in form of panel surveys are absolutely necessary for long-term investigations in the dynamic character of individual migration trajectories, their determinants, and their consequences. Moreover, such data must contain valid and repeated measures to operationalize MBBs representing transnational ways of being and ways of belonging. However, data that meet these criteria are scarce (Erlinghagen et al. Citation2021).

In the following, I illustrate how the TNLC can be utilized in empirical migration research. I relied on data from the new and unique German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS) (Ette et al. Citation2021) that meet the above-mentioned criteria. GERPS covers German citizens who have indicated to local authorities in Germany either their emigration from Germany or their remigration to Germany during the period between June, 2017 and May, 2018 as obliged by law. Since the vast majority of all German citizens are members of the public social security insurances, there are strong incentives for emigrants from that group to officially deregister at least to hedge already achieved entitlements. For example, about 90 per cent of the population is a member of the statutory health insurance in Germany (Busse et al. Citation2017). Thus, it can be suggested that related compliance rates are quite high even if the concrete number remains unknown (Ette et al. Citation2021). GERPS relies on a representative, register-based sample. All GERPS participants were invited by mail to answer an online questionnaire (“push-to-web approach”; Dillman Citation2017). This online questionnaire mainly contains questions about employment, family life, health, and social cohesion (Ette et al. Citation2020, chapter 15.5). In the subsequent waves, the recent emigrants and remigrants were only contacted via e-mail addresses they had provided in wave 1. Up to now, three waves have been executed between November, 2018 and November, 2019 with a time span of six months between each single wave. In the initial wave an overall response rate of 33 per cent was reached. Biased unit-nonresponse in GERPS follows the same pattern observed in other surveys (e.g. skill-related non-response gradient) but there is no evidence of significant effects on data quality (for detailed unit-nonresponse analyses as well as implemented weighting procedures see Ette et al. Citation2020). Interviews were conducted with about 5,000 emigrants and 7,000 remigrants who live or have lived in 160 countries all around the globe (Ette et al. Citation2021). Although GERPS provided data that enabled utilization of TNLC for empirical analyses, the data have of course certain limitations. However, given that TNLC could be a fruitful concept for migration research, such data limitations stress the general need for more and better longitudinal data representing determinants and consequences of migration processes. But that is not a shortcoming, but rather an advantage since such limitations point to the need for more resources to further improve a quantitative as well as qualitative data infrastructure for migration research.

The following illustrative examples rely on information of recent German emigrants who have not only officially registered their emigration between June 2017 and May 2018, but who have also reported that their actual move abroad was within a time span of one year before their first GERPS interview. The GERPS strategy of sampling recent emigrants in the country of origin allows for minimization of selectivity due to biased return and onward migration. Unlike immigrant samples, the GERPS strategy creates a homogeneous group of migrants with regard to their (very short) duration of stay abroad. Thus, these data allow observation of transnational adaptation trajectories in chronological proximity to the event of border crossing. Since GERPS is a panel that interviews internationally mobile individuals no matter where they live, it is also possible to identify further international moves over the course of time. To keep the following illustrative analyses simple and acute, I concentrated on information about those 1,995 emigrants who stayed abroad with no further international moves and who completed all interviews during the three GERPS waves (balanced panel).

In the following analyses, I first took a look at the development of the composition of friendship networks over the course of time (for detailed analyses on friendship networks of emigrants using GERPS data see Décieux and Mörchen Citation2021; Mansfeld Citation2021). Close friends are a crucial element of individual social capital as an important resource that determines individual SES. Therefore, changes in the transnational composition of friendship networks are regarded as changes in migrants’ transnational way of being. Second, I investigated migrants’ reported feelings of belonging to Germany and to the host country and how this possibly changes as time goes on (for detailed analyses on emigrants’ feelings of belonging using GERPS data see Décieux and Murdock Citation2021). Thus, changes in such feelings are regarded as changes in migrants’ ways of belonging. Detailed information about how the composition of friendship networks as well as how feelings of belonging are measured in GERPS and how the data were prepared for the presented analyses can be found in the methodic appendix at the end of this paper. In the appendix it is also shown that there is only a very weak association between the size of the friendship networks and the feeling of belonging to Germany or the host country (Cramer’s V between 0.04 and 0.35).

Transnational friendship networks over the course of time

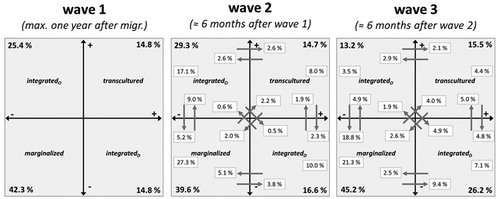

Using MBBs, shows the development of migrants’ transnational friendship networks over the course of the first year up to a maximum of two years after migration. To meet changes in the distribution of the reported number of close friends in the different waves and to make the measurement of the size of friendship networks comparable, information has been z-standardized (Abdi Citation2007). The first MBB on the left side shows that at the initial wave 1 more than 25 per cent of the migrants were still (solely) integrated in Germany and approximately 15 per cent were (solely) integrated in the host country. Integrated means that those emigrants reported an above-average number of friends in Germany or respectively in the host country compared to all other emigrants in the sample. On the contrary, 42.3 per cent of all migrants reported below-average numbers of friends in Germany as well as abroad, which means that they must be considered as marginalized at least with regard to the number of close friends in wave 1. In contrast, about 15 per cent of all migrants showed a transcultural way of being at that time, measured by the above-average number of friends in Germany as well as in their host country.

Figure 6. Changes of emigrants’ transnational friendship networks in the course of time. Source: GERPS W1 to W3 (own calculations); n = 1,976.

In wave 2 six months after the first interview abroad there were only slight changes in the overall distribution of the number of close friends. There was a small increase in the share of migrants solely integrated in Germany (29.3%) or in their host country (16.6%). The share of transcultured migrants stayed almost unchanged (14.7%) whereas a slight decrease in the share of marginalized migrants was observed (39.6%). However, subsequent results indicated that behind these quite stable overall shares, a high volatility of migrants’ friendship networks is hidden. Six months after the first interview more than one-third of all migrants reported a substantial change in the quantity of their network composition. For example, about 15 per cent had overcome their marginalization and gotten integrated either in Germany or in their host country or could be classified as transcultured in wave 2. On the contrary, about 12 per cent became marginalized in the same period, which reflects a decrease in the quantity of their friendship networks in Germany, abroad, or both.

An additional six months later, the results showed that assimilation and dissimilation processes had accelerated over the course of time. In wave 3 only a little more than one-third of all migrants remained in the same MBB quadrant as in wave 2. This increasing volatility was also reflected in the changes in overall distribution of the number of close friends. Particularly the share of migrants who had become solely integrated in the host country increased to 26.2 per cent, whereas the share of migrants solely integrated in Germany significantly decreased to 13.2 per cent. At the same time, the share of transcultured migrants grew only slightly. It is of particular interest that the already high share of marginalized emigrants increased again to 45.2. per cent. This trend was strongly fed by the large share of migrants who had been considered as integrated in Germany in wave 2 but who became marginalized in wave 3 with a below-average number of close friends in both Germany and the host country. Over and above, shows that there were all kinds of adaptations with migrants’ becoming transcultured but also with migrants’ becoming marginalized or reporting unilateral integration either in Germany or in their host country in the course of migration. Subsequent GERPS waves are necessary for investigation of how these heterogeneous adaptation processes in migrants’ way of being further develop over the course of time.

Transnational feelings of belonging over the course of time

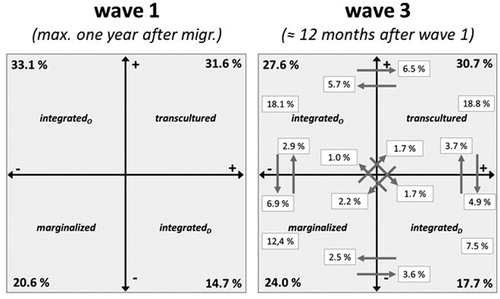

presents findings on changes regarding the migrants’ feelings of belonging towards Germany and towards their host country between wave 1 and 3 (this topic was not addressed in wave 2). Migrants who reported that they felt (quite) close to Germany but not to their host country were marked as integrated in the country of origin. On the contrary, migrants who reported that they felt (quite) close to their host country but not to Germany were marked as integrated in the host country. If migrants said that they felt (quite) close to both Germany and the host country, they were described as transcultured, whereas migrants who reported neither close feelings of belonging to Germany nor to their host country were understood as marginalized. The left MBB in shows that in wave 1 about 80 per cent of all migrants were integrated or even transcultured, whereas 20 per cent could be described as marginalized. Quite a high share of recent migrants already reported a transcultured way of belonging although their emigration dated back no longer than a year.

Figure 7. Changes of emigrants’ transnational feelings of belonging over the course of time. Source: GERPS W1 and W3 (own calculations); n = 1,995.

Comparing to the right MBB in , only moderate changes in the overall shares in the four quadrants can be observed. Compared to the ways of being it seems that migrants’ ways of belonging were more sluggish and consistent over the course of time. About 58 per cent of all migrants reported no substantial change in their feelings of belonging during the first year after the initial interview in wave 1. However, despite this higher consistency, there were also sufficient adaptations during the first year after arrival abroad. Quite similar to the results on the development of friendship networks, there was a slight increase in the share of marginalized migrants between wave 1 and 3, mainly driven by migrants who had been integrated in Germany in wave 1 but felt in wave 3 neither connected to Germany nor to the host country. Moreover, compared to the way of being represented by friendship networks it seems that integration in the host country was easier for migrants with regard to their way of belonging. Whereas only about 16 per cent of migrants reported above-average numbers of friends in Germany as well as in the host country, a much higher share of 31 per cent can be considered as transcultured with regard to their way of belonging.

Discussion and conclusion

In recent decades migration research has made great progress. Theoretical understanding as well as empirical knowledge has increased tremendously. However, there are still two different, thus far largely unconnected conceptual perspectives on migration in social science. On the one hand, there is the life course approach stressing the causal relationship between time and the determinants as well as the consequences of migration. On the other hand, there is the concept of transnational migration that emphasizes different kinds of connections and ties migrants have to people or institutions in their country of origin as well as in their host country irrespective of the actual moving event. Both approaches have their merits but also their shortcomings. A goal of this paper was to overcome these shortcomings by combining the advantages of both perspectives to create a unified theoretical concept of transnational life courses (TNLC). TNLC builds on the multi-dimensional understanding of transnational migration research that (potential) migrants live in multiple social and cultural spaces leading to parallel assimilation and dissimilation processes in the two spheres of (a) thoughts and (b) practice (ways of being vs. ways of belonging). This perspective is merged with the life course approach with its chronological ordered understanding of causality relying on preceding determinants and subsequent outcomes in form of events and periods.

To illustrate the potential of the theoretical TNLC approach to promote migration research, some simple empirical analyses were conducted. These analyses utilized the new and very unique data of the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS). The results demonstrated that migrants undergo complex adaptations in different dimensions with parallel assimilation as well as dissimilation processes. Initially adaptations were moderate but in the course of migration an increasing volatility of such processes was observed. In addition, assimilation and dissimilation in the two spheres of resources and emotions (ways of being vs. ways of belonging) seemed to follow different paces and patterns. Integration or transculturalization is not a single, directed process. There are migrants who show progress in integration and transculturalization. But there is also a high number of migrants who have reached certain levels of integration and transculturalization but then have to face subsequent experience regressions that lead to marginalization as their length of stay in their host country increases.

All in all, the empirical example of a transnational, multi-dimensional observation of friendships (representing differences in social capital as an important resource) within a dynamic life-course framework underpins the potential of TNLC in principle: For an emigrant, it may not matter whether he or she has friends in the country of origin or in the country of destination, but rather that he or she has friends to count on at all. Moreover, transnational friendship formation is independent of the event of border crossing. It could be the case that emigrants already formed friendships with individuals who already live in the new country in advance of their departure. In addition, those friends who have been left behind due to emigration can be of sustained importance for a migrant. This is not only the case with regard to psychological support that can be provided over longer distances by chatting or mailing with far-off friends. Those friends can also be an important resource for instrumental support a migrant probably needs. Think, for example, of the scenario in which the emigrant moves away but has an older or handicapped relative who still lives in the country of origin. In this situation, the existence of friends the emigrant has left behind and who can potentially look after or care for such relatives could help us to better understand emigrants’ (re)migration decisions and mobility outcomes. This example shows that TNLC enables researchers to account for the gradual change in the value of resources in the course of the migration process independent of the actual event of border crossing. In addition, TNLC enables researchers to account for the past dependency of currently observed inequalities in resource distribution. Returning to the example of emigrants’ friendships, it is possible that the increase or decrease of inequalities after the moving event is not an effect of migration (alone) but rather a continuation of inequalities that already existed in the past (e.g. skill differences in friendship formation). The advantage of TNLC to account for time dependencies and relaxing the fixation of the single event of border crossing at the same time is also illustrated by the empirical analyses of the sphere of emotions (ways of belonging). Like in the case of friendships (ways of being), emigrants can also develop feelings of belonging to their (potential) destination in advance of the emigration event and they can lose feelings of belonging to their original home country before they actually make an international move.

The presented results are promising and encouraging that the TNLC approach can promote migration research. There are also important limitations and challenges that have to be addressed in future research. The analyses presented in this paper have shown that there are extensive data requirements for TNLC-related research stressing a general lack of sufficient data for migration research (Willekens et al. Citation2016). We need longitudinal data measuring the development of certain important indicators of assimilation and dissimilation with regard to countries of origin, but also with regard to (potential) destination countries of migrants. We need improvement in measurement of sufficient items representing transnational differences in SES and its underling resources (economic capital, human capital, and social capital). Moreover, migration research needs more data on non-mobile individuals and their ways of being and ways of belonging with regard to potential migration destinations. Only a comparison of movers and (preliminary) stayers can complete our understanding of the causes and consequences of migration (Guveli et al. Citation2017; Erlinghagen et al. Citation2021). Besides that, it is an open question how exclusive, singular events that lead to more or less stable states of living can be integrated into TNLC. Events like becoming unemployed or giving birth to a child do not allow an ambivalent and undetermined location in different social and cultural spaces, but are simply bounded to a certain geographical place. In other words, normally a (potential) migrant can only be (un)employed in one country and a child can only be born in one geographic location. It will be a challenge to think about how such distinct, localized events and states could be integrated in TNLC. One idea could be to understand such singular events and the following states as an outcome of previous decisions that are based on a complex interplay of resources and their variable values (ways of being) and the ambivalent feelings (ways of belonging) connected to different social spaces.

Despite such limitations and challenges, TNLC as a unified the theoretical concept has the unambiguous potential to promote migration research. Although TNLC refers to important ideas of the life course approach as well as of transnational migration research, it is not just a simple combination or hodgepodge of selected arguments. In fact, the unified TNLC paradigm is more than the sum of its individual parts. It improves theoretical understanding of complex individual migration trajectories by using intertwined causes and consequences and will hopefully stimulate and inspire future thinking about individual mobility in a more and more globalized world.

Methodic appendix

GERPS has asked their participating emigrants in each wave how many close friends they have. In a next step all emigrants who reported a number of close friends above 0 were asked “How many of these close friends live in Germany?” and “How many of these close friends live in the country you are living in at the moment?” (Ette et al. Citation2020, 174). Emigrants reporting more than 25 close friends in Germany or abroad were excluded from the analyses (n = 9). The values were z-standardized. If the z-value was below 0, the emigrant was counted as having a below-average number of friends. If the z-value equalled or exceeded 0, the emigrant was counted as having an (above-)average number of friends. In wave 1 and 3, GERPS also asked their participants to rate how strongly they feel connected to certain places or regions and their citizens with the following categories “very strongly”, “pretty strongly”, “not strongly”, and “not at all” (Ette et al. Citation2020, 218). The following places and regions were presented: (a) “your municipality (city) in the country in which you currently live and its citizens”, (b) “the country in which you currently live as a whole and its citizens”, (c) “your community of origin (city) in Germany and its citizens”, (d) “Germany as a whole and its citizens”, and (e) “the European Union and its citizens” (Ette et al. Citation2020, 218). The analyses presented here refer only to the connectedness to the host country (category b) and to Germany (category c). If an emigrant claimed that he or she very strongly or pretty strongly identified with Germany or the host country, I count the emigrant as integrated or respectively transcultured. If they reported that they were not strongly or not at all identifying with Germany and with their host country, I marked them as marginalized. If information on the feelings of identification with Germany or the host country was not available in one wave, the individuals were excluded from the analyses (n = 87). document the associations between the analysed variables (Cramer’s V).

Table 1. Cramer’s V for the association between the number of friends in Germany and in the host country (wave 1 to wave 3).

Table 2. Cramer’s V for the association between the feeling of belonging to Germany and to the host country (wave 1 and wave 3).

Table 3. Cramer’s V for the association between the number of friends (Germany vs. host country) and the feeling of belonging (Germany vs. the host country) (Wave 1 to Wave 3).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Helen Baykara-Krumme, Sigrid Quack and two anonymous ERS reviewers for their helpful comments. He would also like to thank Ecki Günther for his faithfulness and inspiration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdi, Hervé. 2007. “Z Scores.” In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics, edited by Neil J. Salkind, and Kristin Rasmussen, 1057–1058. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191. doi:10.1093/jrs/fen016.

- Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 1997. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 826–874. doi:10.2307/2547416.

- Arango, Joaquín. 2000. “Explaining Migration: A Critical View.” In International Social Science Journal 52 (165): 283–296. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00259.

- Bach, Robert L., and Joel Smith. 1977. “Community Satisfaction, Expectations of Moving, and Migration.” Demography 14 (2): 147–167.

- Barrett, Alan, and Bertrand Maître. 2013. “Immigrant Welfare Receipt Across Europe.” International Journal of Manpower 34 (1): 8–23. doi:10.1108/01437721311319629.

- Becker, Gary S. 1964. Human Capital. A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Distributed by Columbia University Press (National Bureau of Economic Research. General series, no. 80).

- Berry, John W. 1974. “Psychological Aspects of Cultural Pluralism. Unity and Identity Reconsidered.” Topics in Cultural Learning 2: 17–22.

- Berry, John W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46 (1): 5–34. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x.

- Berry, John W. 2001. “A Psychology of Immigration.” Journal of Social Issues 57 (3): 615–631. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00231.

- Bolt, Gideon, A. Sule Özüekren, and Deborah Phillips. 2010. “Linking Integration and Residential Segregation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (2): 169–186. doi:10.4324/9780203718490.

- Böheim, René, and Mark P Taylor. 2002. “Tied Down or Room to Move? Investigating the Relationships Between Housing Tenure, Employment Status and Residential Mobility in Britain.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 49 (4): 369–392.

- Burt, Ronald S. 1992. Structural Holes. The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Busse, Reinhard, Miriam Blümel, Franz Knieps, and Till Bärnighausen. 2017. “Statutory Health Insurance in Germany: a Health System Shaped by 135 Years of Solidarity, Self-Governance, and Competition.” The Lancet 390 (10097): 882–897. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31280-1.

- Chiswick, Barry R., and Paul W Miller. 2009. “The International Transferability of Immigrants’ Human Capital.” Economics of Education Review 28 (2): 162–169. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2008.07.002.

- Clark, William A. V., and Valerie Ledwith. 2006. “Mobility, Housing Stress, and Neighborhood Contexts: Evidence from Los Angeles.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (6): 1077–1093. doi:10.1068/a37254.

- Cohen, Jeffrey H. 2011. “Migration, Remittances, and Household Strategies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40 (1): 103–114. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145851.

- Coulter, Rory, and Jacqueline Scott. 2015. “What Motivates Residential Mobility? Re-Examining Self-Reported Reasons for Desiring and Making Residential Moves.” Population, Space and Place 21 (4): 354–371. doi:10.1002/psp.1863.

- Dahinden, Janine. 2016. “A Plea for the ‘de-Migranticization’ of Research on Migration and Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2207–2225. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1124129.

- Décieux, Jean P., and Luisa Mörchen. 2021. “Emigration, Friends, and Social Integration: The Determinants and Develop-ment of Friendship Network Size After Arrival.” In The Global Lives of German Migrants. Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course. IMISCOE Research Series, edited by Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte, 261–280. Cham: Springer.

- Décieux, Jean P., and Elke Murdock. 2021. “Sense of Belonging: Predictors for Host Country Attachment Among German Emigrants.” In The Global Lives of German Migrants. Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course. IMISCOE Research Series, edited by Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte, 281–301. Cham: Springer.

- Dillman, Don. A. 2017. “The Promise and Challenge of Pushing Respondents to the Web in Mixed-Mode Surveys.” Survey Methodology 43 (3): 3–30.

- DiMaggio, Paul. 1994. “Culture and Economy.” In Handbook of Economic Sociology, edited by Neil J. Smelser, and Richard Swedberg, 27–57. Princeton, New York: Princeton University Press; Russel Sage Foundation.

- Dribe, Martin, and Christer Lundh. 2008. “Intermarriage and Immigrant Integration in Sweden.” Acta Sociologica 51 (4): 329–354. doi:10.1177/0001699308097377.

- Drinkwater, Stephen, John Eade, and Michal Garapich. 2009. “Poles Apart? EU Enlargement and the Labour Market Outcomes of Immigrants in the United Kingdom.” International Migration 47 (1): 161–190. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00500.x.

- Elder, Glen H., Monica Kirkpatrick Johnson, and Robert Crosnoe. 2004. “The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory.” In Handbook of the Life Course, edited by Jeylan T. Mortimer, and Michael J. Shanahan, 3–19. New York, NY: Springer (Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research).

- Erlinghagen, Marcel. 2016. “Anticipation of Life Satisfaction Before Emigration: Evidence from German Panel Data.” In Advances in Happiness Research. A Comparative Perspective, edited by Tachibanaki Toshiaki, 1st ed., 229–244. Tokyo: Springer Japan (Creative Economy).

- Erlinghagen, Marcel, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte. 2021. “Between Origin and Destination: German Migrants and the Individual Consequences of Their Global Lives.” In The Global Lives of German Migrants. Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course. IMISCOE Research Series, edited by Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte, 1–19. Cham: Springer.

- Ette, Andreas, Jean Philippe Décieux, Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Genoni, Jean Guedes Auditor, Frederik Knirsch, et al. 2020. German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS): Methodology and Data Manual of the Baseline Survey (Wave 1). Wiesbaden: Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung (BIB) (BiB Daten- und Methodenbericht, 1-2020).

- Ette, Andreas, Jean P. Décieux, Marcel Erlinghagen, Jean Guedes Auditor, Nikola Sander, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte. 2021. “Surveying Across Borders: The Experiences of the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study.” In The Global Lives of German Migrants. Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course. IMISCOE Research Series, edited by Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte, 21–40. Cham: Springer.

- Faist, Thomas. 2000a. The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and Transnational Social Spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Faist, Thomas. 2000b. “Transnationalization in International Migration: Implications for the Study of Citizenship and Culture.” In Ethnic and Racial Studies 23 (2): 189–222. doi:10.1080/014198700329024.

- FitzGerald, David. 2012. “A Comparativist Manifesto for International Migration Studies.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (10): 1725–1740. doi:10.1080/01419870.2012.659269.

- Flippen, Chenoa. 2014. “U.S. Internal Migration and Occupational Attainment: Assessing Absolute and Relative Outcomes by Region and Race.” Population Research and Policy Review 33 (1): 31–61. doi:10.1007/s11113-013-9308-3.

- Geist, Claudia, and Patricia A McManus. 2008. “Geographical Mobility Over the Life Course: Motivations and Implications.” Population, Space and Place 14 (4): 283–303. doi:10.1002/psp.508.

- Glick Schiller, Nina. 2003. “The Centrality of Ethnography in the Study of Transnational Migration.” In American Arrivals. Anthropology Engages the New Immigration, edited by Nancy Foner, 99–128. Santa Fe, Oxford: School of American research Press; J. Currey (School of American Research advanced seminar series).

- Glick Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton. 1992. “Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 645: 1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb33484.x.

- Gold, Steven J., and Stephanie J Nawyn. 2019. Routledge International Handbook of Migration Studies. New York: Routledge.

- Gordon, Milton Myron. 1964. Assimilation in American Life. The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380.

- Guarnizo, Luis Eduardo, Alejandro Portes, and William Haller. 2003. “Assimilation and Transnationalism: Determinants of Transnational Political Action Among Contemporary Migrants.” American Journal of Sociology 108 (6): 1211–1248. doi:10.1086/375195.

- Guveli, Ayse, Harry B. G. Ganzeboom, Helen Baykara-Krumme, Lucinda Platt, Şebnem Eroğlu, Niels Spierings, et al. 2017. “2,000 Families: Identifying the Research Potential of an Origins-of-Migration Study.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (14): 2558–2576. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1234628.

- Hagan, Jacqueline Maria, Hernández-León Rubén, and Jean-Luc Demonsant. 2015. Skills of the “Unskilled”. Work and Mobility among Mexican Migrants. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Heckhausen, Heinz, and Peter M Gollwitzer. 1987. “Thought Contents and Cognitive Functioning in Motivational Versus Volitional States of Mind.” Motivation and Emotion 11 (2): 101–120. doi:10.1007/BF00992338.

- Hofstede, Geert, and Robert R McCrae. 2004. “Personality and Culture Revisited: Linking Traits and Dimensions of Culture.” Cross-Cultural Research 38 (1): 52–88. doi:10.1177/1069397103259443.

- Itzigsohn, Jose, Carlos Dore Cabral, Esther Hernandez Medina, and Obed Vazquez. 1999. “Mapping Dominican Transnationalism: Narrow and Broad Transnational Practices.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22 (2): 316–339. doi:10.1080/014198799329503.

- Ivlevs, Artjoms. 2015. “Happy Moves? Assessing the Link Between Life Satisfaction and Emigration Intentions.” Kyklos 68 (3): 335–356. doi:10.1111/kykl.12086.

- Jong, Gordon F. De, and Robert W. Gardner1981. Migration Decision Making. Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Jong, Petra W. de, and Helga A. G. de Valk. 2020. “Intra-European Migration Decisions and Welfare Systems: The Missing Life Course Link.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1773–1791. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1611421.

- Kley, Stefanie. 2011. “Explaining the Stages of Migration Within a Life-Course Framework.” In European Sociological Review 27 (4): 469–486. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq020.

- Landale, Nancy S., and Avery M Guest. 1985. “Constraints, Satisfaction and Residential Mobility: Speare’s Model Reconsidered.” Demography 22 (2): 199–222.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity. A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1002–1039.

- Levitt, Peggy, and B. Nadya Jaworsky. 2007. “Transnational Migration Studies: Past Developments and Future Trends.” Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 129–156. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131816.

- Lima, F. Herrera. 2001. “Transnational Families. Institutions of Transnational Social Space.” In New Transnational Social Spaces, edited by Ludger Pries, 77–93. London: Routledge.

- Lindbekk, Tore. 1992. “The Weberian Ideal-Type: Development and Continuities.” Acta Sociologica 35 (4): 285–297. doi:10.1177/000169939203500402.

- Liversage, Anika, and Vibeke Jakobsen. 2016. “Unskilled, Foreign, and Old.” The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry 29 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1024/1662-9647/a000146.

- Lucassen, Leo. 2006. “Is Transnationalism Compatible with Assimilation? Examples from Western Europe Since 1850.” IMIS-Beiträge 29: 15–36.

- Luthra, Renee R. 2013. “Explaining Ethnic Inequality in the German Labor Market: Labor Market Institutions, Context of Reception, and Boundaries.” European Sociological Review 29 (5): 1095–1107. doi:10.1093/esr/jcs081.

- Lübke, Christiane. 2015. “How Migration Affects the Timing of Childbearing: The Transition to a First Birth Among Polish Women in Britain.” European Journal of Population 31 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1007/s10680-014-9326-9.

- Mansfeld, Lisa. 2021. “Out of Sight, Out of Mind? Frequency of Emigrants’ Contact with Friends in Germany and its Impact on Subjective Well-Being.” In The Global Lives of German Migrants. Consequences of International Migration Across the Life Course. IMISCOE Research Series, edited by Marcel Erlinghagen, Andreas Ette, Norbert F. Schneider, and Nils Witte, 241–260. Cham: Springer.

- Martin, John Levi. 2003. “What Is Field Theory?” American Journal of Sociology 109 (1): 1–49.

- Marx, Karl. (1867) 1962. Das Kapital. Band 1. Berlin (Ost): Dietz (Marx-Engels-Werke, 23).

- Mayer, Karl Ulrich. 2009. “New Directions in Life Course Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 35 (1): 413–433. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134619.

- Mincer, Jacob. 1962. “On-the-Job Training: Costs, Returns, and Some Implications.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 50–79.

- Mouw, Ted, and Barbara Entwisle. 2006. “Residential Segregation and Interracial Friendship in Schools.” American Journal of Sociology 112 (2): 394–441. doi:10.1086/506415.

- Mulder, Clara H., and Pieter Hooimeijer. 2012. “Residential Relocations in the Life Course.” In Population Issues. An Interdisciplinary Focus, edited by Kenneth C. Land, Leo J. G. van Wissen, and Pearl A. Dykstra, 159–186. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Mulder, Clara H., and Gunnar Malmberg. 2014. “Local Ties and Family Migration.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 46 (9): 2195–2211. doi:10.1068/a130160p.

- Newman, Sandra J., and Greg S Duncan. 1979. “Residential Problems, Dissatisfaction, and Mobility.” Journal of American Planning Association 45 (2): 154–166.

- Nieswand, Boris. 2011. Theorising Transnational Migration. The Status Paradox of Migration. New York: Routledge. Routledge research in transnationalism, 22.

- Nohl, Arnd-Michael, Karin Schittenhelm, Oliver Schmidtke, and Anja Weiß. 2014. Work in Transition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Nowok, Beata, Maarten van Ham, Allen M. Findlay, and Gayle Vernon. 2013. “Does Migration Make You Happy? A Longitudinal Study of Internal Migration and Subjective Well-Being.” Environment and Planning A 45 (5): 986–1002.

- Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva. 2003. “The Politics of Migrants’ Transnational Political Practices.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 760–786. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00157.x.

- Popper, Karl R. (1959) 2008. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Repr. 2008 (Twice). London: Routledge (Routledge classics).

- Portes, Alejandro, Luis E. Guarnizo, and Patricia Landolt. 1999. “The Study of Transnationalism: Pitfalls and Promise of an Emergent Research Field.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22: 217–237. doi:10.4324/9781351171489-12.

- Pries, Ludger. 2005. “Configurations of Geographic and Societal Spaces: A Sociological Proposal Between ‘Methodological Nationalism’ and the ‘Spaces of Flows’.” Global Networks 5 (2): 167–190. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2005.00113.x.

- Schneider, Jens, and Maurice Crul. 2010. “New Insights Into Assimilation and Integration Theory: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (7): 1143–1148. doi:10.1080/01419871003777809.

- Smith, Christian. 2016. “The Conceptual Incoherence of “Culture” in American Sociology.” The American Sociologist 47 (4): 388–415. doi:10.1007/s12108-016-9308-y.

- Smith, Michael P., and Luis Guarnizo. 1998. Transnationalism from Below. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers (Comparative urban and community research, v. 6).

- Speare, Alden. 1974. “Residential Satisfaction as an Intervening Variable in Residential Mobility.” Demography 11 (2): 173–188. doi:10.2307/2060556.

- Swedberg, Richard. 2018. “How to use Max Weber’s Ideal Type in Sociological Analysis.” Journal of Classical Sociology 18 (3): 181–196. doi:10.1177/1468795X17743643.

- Swidler, Ann. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51 (2): 273. doi:10.2307/2095521.

- Thomas, Kevin J. A. 2015. “Occupational Stratification, Job-Mismatches, and Child Poverty: Understanding the Disadvantage of Black Immigrants in the US.” Social Science Research 50: 203–216. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.013.

- Tsuda, Takeyuki. 2012. “Whatever Happened to Simultaneity? Transnational Migration Theory and Dual Engagement in Sending and Receiving Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (4): 631–649. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2012.659126.

- Waldinger, Roger, and David FitzGerald. 2004. “Transnationalism in Question.” American Journal of Sociology 109 (5): 1177–1195. doi:10.1086/381916.

- Weiß, Anja. 2017. “Contextualizing Global Inequalities.” In The World-System as Unit of Analysis, edited by Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz, 75–85. London: Routledge.

- Weiß, Anja, and Samuel N.-A Mensah. 2011. “Access of Highly-Skilled Migrants to Transnational Labor Markets: Is Class Formation Transcending National Divides?” In Globalization and Inequality in Emerging Societies, edited by Boike Rehbein, 211–234. London: Springer Nature.

- Willekens, Frans, Douglas Massey, James Raymer, and Cris Beauchemin. 2016. “International Migration Under the Microscope.” Science 352 (6288): 897–899. doi:10.1126/science.aaf6545.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond. Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334.

- Wingens, Matthias, Helga de Valk, Michael Windzio, and Can Aybek. 2011a. “The Sociological Life Course Approach and Research on Migration and Integration.” In A Life-Course Perspective on Migration and Integration, edited by Matthias Wingens, Michael Windzio, Helga de Valk, and Can Aybek, 1–26. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Wingens, Matthias, Michael Windzio, Helga de Valk, and Can Aybek. 2011b. A Life-Course Perspective on Migration and Integration. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Wolpert, Julian. 1966. “Migration as an Adjustment to Environmental Stress.” Journal of Social Issues 22 (4): 92–102. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1966.tb00552.x.

- Yinger, J. Milton. 1981. “Toward a Theory of Assimilation and Dissimilation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 4 (3): 249–264. doi:10.1080/01419870.1981.9993338.