ABSTRACT

Public debates proclaim that Muslims have turned their backs on Western societies and their “core values”. Quantitative studies have shown that Muslim migrants identify more with their origin nation and less with their host country, and that they support gender equality less than other migrants. While often attributed to Muslims’ religiosity, migrants’ denominations also reflect whether they belonged to the dominant religious majority or a marginalized minority in their origin country, which also shapes national identifications and support for gender equality. EURISLAM data on 1,500 migrants from Turkey and Pakistan show that Alevi and Ahmadiyya minority-migrants identify less with their origin country and more with their host society than Sunni majority-migrants. Pivotally, marginalized minority-migrants acculturate faster, as their support for gender equality increases more strongly over the years than majority-migrants’. Altogether, focusing on essentialist views of Muslims’ religion overlooks other mechanisms that shape diversity in acculturation among Muslim migrants.

Introduction

Western public debates on integration have become increasingly skeptical, especially when it comes to Muslim migrants (Röder Citation2014; Ghorashi Citation2010; Horsti Citation2008). Some public voices proclaim that Muslims’ integration has failed, arguing that Muslim migrants have turned their backs on their Western host societies. Muslim migrants would feel more loyalty toward their origin countries than their host countries and denounce “core Western values”, especially gender equality.

Echoing these sentiments, quantitative migration scholars have argued that Muslims’ religiosity hampers their acculturation (as Spierings (Citation2015) notes). Many studies have shown that Muslim migrants on average support gender equality less than non-Muslim migrants or natives (e.g. Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Norris and Inglehart Citation2012; Röder and Mühlau Citation2014). Several argue that Muslim migrants identify less with their host country and more with their origin country (e.g. Fukuyama Citation2006; Statham et al. Citation2005; Zimmermann, Zimmermann, and Constant Citation2007). Such differences between migrants with varying denominations are generally interpreted in terms of religiosity (as Banfi, Gianni, and Giugni (Citation2016) argue). Muslim migrants’ interpretations of Islam would prevent them from feeling part of the host society and supporting gender equality (Huntington Citation1996; Norris and Inglehart Citation2012).

However, denominational differences do not solely reflect individual religiosity; denominations also demarcate groups with varying social, economic, and political power (Banfi, Gianni, and Giugni Citation2016; Bloom and Arikan Citation2013). Denomination signifies the status migrants had in their origin country: whether they belonged to subordinate, marginalized religious minorities or the dominant religious majority. Belonging to the majority versus minority has been shown to impact a host of values by studies that do not focus on migrants (e.g. Braun Citation2016; Evans and Need Citation2002; Spierings Citation2019). In quantitative migration studies however, denominational differences are often interpreted as religious differences strictly speaking, thereby neglecting groups’ status positions in origin countries (e.g. Koopmans Citation2015; Martinovic and Verkuyten Citation2016). The lack of attention to migrants’ minority-majority status in their origin country means that denominational differences in migrants’ integration may have been partly misinterpreted as solely signalling individual religiosity (as Banfi, Gianni, and Giugni (Citation2016) note).

The present study delves into how migrants’ national identifications and support for gender equality are shaped by whether they belonged to the religious majority or a marginalized minority in their origin country. I do not aim to deconstruct the notion that individual religiosity matters for integration outcomes; it probably does. My main contribution is more constructive: to provide additional insights into why and how migrants’ denomination shapes integration outcomes.

I focus on migrants’ identification with their origin country and host country and their support for gender equality because public voices argue these aspects of integration are particularly “failed” due to Muslim migrants’ religiosity (Ghorashi Citation2010). Additionally, scholarly work has interpreted denominational differences to reflect individual religiosity in particular concerning these integration outcomes (Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Statham et al. Citation2005; Verkuyten and Martinovic Citation2012). By focusing on national identifications and support for gender equality, I thus provide insights into how origin minority-majority status matters for the societally and scientifically most relevant areas.

I study two religious marginalized minorities: Alevi migrants from Turkey and Ahmadiyya migrants from Pakistan (compared to Sunni majority-migrants from Turkey and Pakistan). This is partly due to data availability; the EURISLAM provides high-quality data on these groups and they are sizable enough to address in a quantitative study. Additionally, existing quantitative studies tend to include Turkish and Pakistani migrants, so insights on the impact of their origin minority-majority status can be connected to existing studies (e.g. Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Scheible and Fleischmann Citation2013; Kavli Citation2015).

Most importantly, though, I focus on Alevi migrants from Turkey and Ahmadiyya migrants from Pakistan as they are marginalized minorities, which has important theoretical implications (Banfi, Gianni, and Giugni Citation2016). Alevis in Turkey and Ahmadis in Pakistan have been marginalized in terms of their political influence and freedom of expression; they have also been denied to be true Muslims and involved in sectarian clashes, and they have been victims of organized attacks by conservative Sunnis (Erman and Göker Citation2000; Grigoriadis Citation2006; Kose Citation2013; Saeed Citation2007). The current paper argues that this marginalization in origins is pivotal, as it implies that Alevi and Ahmadiyya migrants were relatively more excluded prior to migration, whereas Sunni migrants lose relatively more status after migration. Below, I develop a framework that proposes this difference in status loss has consequences for their national identifications and (acculturation into) support for gender equality. Ultimately, if this framework holds, Muslim migrants’ denominations do not only block but also fuel their integration.

Theory

Migration scholars have noted that we currently have far deeper understandings of how migrants’ integration is shaped by their experiences in their host country than those in their origin country (Spierings Citation2015). However, migrants take part of their background with them when they migrate, and their experiences in their origin country probably continue to influence their lives (Engbersen et al. Citation2014; Van Tubergen Citation2006; Van Tubergen, Maas, and Flap Citation2004). As Fokkema and De Haas argue, “socio-cultural integration is determined to a considerable extent by the “baggage” migrants take along from their country of origin” (Citation2015, 21). The present study adds to the literature by developing a framework that centres on how migrants’ values are shaped by their pre-migration background, specifically whether they belonged to the religious majority (“majority-migrants”) or minority (“minority-migrants”) in their origin country.

Existing studies, although few and often not theoretically focused on origin status, indeed show differences between migrant groups who belonged to the minority versus the majority in their origin country. Verkuyten and Yildiz (Citation2009) find that (minority) Alevi migrants from Turkey are less negative toward Jews and non-believers than Sunni migrants. Koopmans (Citation2015) similarly argues that Alevi migrants are less fundamentalist – although Verkuyten and colleagues (Citation2014) report that Alevis are less politically tolerant. Closest to the current study, Banfi, Gianni, and Giugni’s (Citation2016) interesting work shows that religious minority-migrants support secularism (in politics) more than religious majority-migrants. Altogether, migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country do seem to differ from majority-migrants, at least in their religious attitudes.

My framework adds to these studies by explaining why migrants’ non-religious attitudes are shaped by whether they belonged to the religious majority or minority in their origin country. At its core, this framework argues that how migrants handle becoming part of the minority in their host country is affected by whether they experienced marginalization prior to migration. Central to this framework is the understanding that, after migration, majority-migrants’ status declines more strongly than minority-migrants’. Majority-migrants move from a dominant societal position to a minority one. Minority-migrants, on the other hand, experience less loss of privilege as they had less to start with; their status may even improve after migration. Below, I synthesize diverse literatures as quantitative migration studies, qualitative migration studies, social psychological theories, and gender studies to argue that this difference in status loss upon migration between majority-migrants and minority-migrants probably affects how they feel toward their origin country and their host country and their (acculturation strategies concerning) support for gender equality.

Identification with origins

First, majority-migrants and minority-migrants are expected to differ in their identification with their origin country. Religious minority-members can be expected identify less with their origin nation before migration, as they belonged to devalued groups. Although tensions have increased and abated over the years, Alevis in Turkey and Ahmadis in Pakistan have historically been viewed antagonistically by (conservative) Sunni Turks and Pakistanis, who have, among others, argued Alevis and Ahmadis are not true Muslims but disgraceful heretics (Erman and Göker Citation2000; Saeed Citation2007). Additionally, although especially Alevi Turks have been divided in their political loyalties and have shifted in their allegiances with (secular) regimes, Alevis and Ahmadis have been at or outside the margins of “the ideal (Sunni) citizen” (Kose Citation2013; Kieser Citation2001; Zaman Citation1998). As nation-building notions as “the Alevi question” and “the Ahmadi question” imply, Alevis in Turkey and Ahmadis in Pakistan have been marginalized by their respective nation-states.

Social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Turner et al. Citation1984) and the rejection-identification model (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999) propose that, in the face of group rejection, marginalized groups employ identity management strategies to create and maintain positive group identities. More specifically, marginalized religious minorities are expected to distance themselves from the dominant group and turn away from their origin country, instead focusing on their ingroup. Rather than trying to belong to a group that excludes them, religious minorities are thus expected to strongly identify as members of the religious minority group (Bozorgmehr Citation1997; Lu Citation2019; Trieu Citation2013). Therefore, prior to migration, marginalized religious minorities are expected to identify less with their origin country than dominant religious majorities.

The same logic underlines that the difference in origin country identification between religious minorities and majorities persists or may even expand after migration. In Western European countries, migrants are minorities, and they are increasingly marginalized ones given the exclusionary debates on especially Muslim migrants (Ghorashi Citation2010; Verkuyten et al. Citation2014). As seen, the rejection-identification model proposes that migrants consequently employ identity management strategies, including turning towards their ingroup (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999; Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Turner et al. Citation1984).

However, the extent to which migrants retreat into their ingroup and what ingroup they retreat into after migration can be expected to differ for majority-migrants and minority-migrants. Whereas minority-migrants were already marginalized in their origin countries, migrants who belonged to the religious majority lose their dominant status upon migration. Assuming that a threat to group identity causes a stronger response among groups used to being in dominant positions, majority-migrants could retreat more strongly into their ingroups than minority-migrants.

More importantly, majority-migrants are more likely to view their origin country identity as a positive group identity and consequently focus on their origin country in particular. Contrary to minority-migrants, majority-migrants used to be idealized as exemplary citizens – the ultimate insiders in their origin nation-states (Kose Citation2013; Kieser Citation2001; Saeed Citation2007). To create positive ingroup identities after migration, majority-migrants can thus draw on their dominant status in their origin country. Minority-migrants, however, can gain little by focusing on their marginalized origin nation identity. Therefore, majority-migrants may identify more with their origin country after migration, or at least do so more strongly than minority-migrants. Altogether, differences in social identity processes before and after migration cause me to expect that migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country identify less with their origin country than migrants who belonged to the religious majority (hypothesis 1).

Identification with hosts

Again drawing on social identity theory and the rejection-identification model, migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country can also be expected to identify more with their host country than majority-migrants. To appreciate this, it is important to first note that not all identifications are mutually exclusive (Dommelen et al. Citation2015; Roccas and Brewer Citation2002). Migrants’ identification with their origin country or their religious ingroup do not necessarily preclude their identification with their host society (Verkuyten and Martinovic Citation2012; Zimmermann, Zimmermann, and Constant Citation2007). Although after migration, minority-migrants and majority-migrants are thus both expected to be focused on their ingroups, they may still identify with their host country as well, and differ in the extent to which they do so.

Minority-migrants can be expected to identify more with their host country, first, because they lose less status when they move toward their host country. Although Western European public debates exclude Muslim migrants, Alevis and Ahmadis can still perceive their status to be relatively better than in their origin countries (Ghorashi Citation2010). As seen, Alevi Turks and Ahmadiyya Pakistanis are politically and legally marginalized in their origin countries, and the ideal Turkish and Pakistani citizens are depicted to be Sunni (Kose Citation2013; Kieser Citation2001; Saeed Citation2007). Therefore, Alevi and Ahmadiyya migrants can be expected to feel more included in their host country, where their identities as Muslims are at least not refuted and they experience less violence. Majority-migrants, however, face greater marginalization after migration because they had a more privileged status in their origin countries. The rejection-identification model consequently proposes that majority-migrants turn away from the host society that rejects them, whereas minority-migrants do so less (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999; Turner et al. Citation1984). Therefore, minority-migrants’ greater inclusion in their host society (relative to their origin society) is expected to cause stronger host country identification among minority-migrants than majority-migrants.

Note that minority-migrants are still expected to feel relatively more included in their host country even if the assumption that they experienced greater marginalization in origins than in hosts (in absolute terms) does not. Minority-migrants can still be expected to experience relatively lower marginalization than in their origin countries, compared to majority-migrants. Therefore, turning away from the host country can still be expected to be relatively stronger among majority-migrants than minority-migrants, which implies that minority-migrants identify more strongly with their hosts than majority-migrants.

Second, drawing on qualitative studies, minority-migrants may feel less rejected in host country because they can more easily mitigate exclusions by presenting themselves strategically (Bozorgmehr Citation1997; Lu Citation2019; Min Citation2013; Trieu Citation2013). For instance, migrants who belonged to the religious minority can introduce themselves as “from the origin country”, “an oppressed minority” or even more specifically as “oppressed by Sunni Muslims”. Minority-migrants can thus present themselves in a way that reduces exclusions by host societies’ natives. However, migrants who belonged to the religious majority in their origin country have fewer options to present themselves strategically. Minority-migrants are consequently expected to be able to mitigate exclusions better than majority-migrants. As seen, the rejection-identification model then proposes that majority-migrants may disengage from host countries and focus on their ingroup more than minority-migrants. Altogether, both minority-migrants’ lesser reductions in status and exclusions after migration cause me to expect that migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country identify more with their host countries than migrants who belonged to the religious majority (hypothesis 2).

Support for gender equality

Origin minority-majority status is not only expected to influence migrants’ national identifications but also their support for gender equality. Muslim migrants have often been argued to support gender equality less than others because their religion would beget gender traditionalism (see Spierings Citation2015; e.g. Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Koopmans Citation2015; Martinovic and Verkuyten Citation2016; Norris and Inglehart Citation2012). However, differences in support for gender equality between denominational groups can also reflect the status migrants had in their origin countries, which, to my knowledge, no study has addressed yet. Minority-migrants’ acculturation into support for gender equality in their host country can even be expected to be qualitatively different from majority-migrants’, as I will argue now.

Synthesizing insights from gender scholars with the social psychological theories, minority-migrants can be expected to support gender equality less than majority-migrants before migration. As seen, the rejection-identification model proposes that marginalized groups are strongly focused on their ingroup (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999), and minority-migrants have indeed been found to be strongly attached to their minority group (Bozorgmehr Citation1997). Gender scholars add that, when a marginalized group is strongly focused on its ingroup, special restrictions are placed on women, because women are the ones charged with performing ingroup identity (Ajrouch Citation2004; Giuliani, Olivari, and Alfieri Citation2017; Le Espiritu Citation2001). Women are expected to, for instance, embody ingroup virtue by abstaining from sex (especially with outgroup members) and perform ingroup culture by cooking traditional meals and raising children with ingroup values. So, women become symbols of ingroup culture and charged with enacting that culture by being homemakers-caregivers. Insights from gender studies thus propose that minorities’ stronger focus on their ingroup fuels traditional gender values, because minorities forge homebound identity-protecting roles for women. This logic implies that, prior to migration, minority-migrants support gender equality less than majority-migrants.

The same logic however proposes that, after migration, the difference in support for gender equality between minority-migrants and majority-migrants reverses. As argued above, minority-migrants lose relatively less status than majority-migrants after migration, because majority-migrants held more dominant positions in their origin country. This implies, first, that minority-migrants may open up their ingroup boundaries, as they feel less rejected and marginalized (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999). Drawing on gender studies, minority-migrants may consequently loosen the restrictions they placed on women; their initial gender traditionalism may peter out (Ajrouch Citation2004; Giuliani, Olivari, and Alfieri Citation2017; Le Espiritu Citation2001).

On the other side of the coin, majority-migrants lose status after migration, which is expected to cause them to retreat into their ingroups more strongly (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999). This may not only fuel gender traditionalism as women become the bearers of majority-migrants’ ingroup culture, but also because majority-migrants are expected to reassert the virtuousness of their ingroup values. As current Western European public debates portray Muslim migrants negatively as strongly gender traditional, majority-migrants may construct positive group identities by portraying gender traditionalism as positive (Ghorashi Citation2010; Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2009). Minority-migrants are expected to do so less because they are less focused on ingroup identity maintenance, following their relatively lesser marginalization in their host society. Altogether, because majority-migrants lose relatively more status after migration compared to minority-migrants, majority-migrants’ initially greater support for gender equality may wane whereas minority-migrants’ support may increase after migration.

Second, differences in status loss between minority-migrants and majority-migrants may cause their acculturation strategies to differ. Existing studies show that, on average, migrant groups adopt the gender attitudes of their host societies over time, but the strength and speed of this acculturation differs across migrant groups (Pessin and Arpino Citation2018; Röder and Mühlau Citation2014). Because majority-migrants are expected to feel more excluded by their host country, they may resist adopting its values more than minority-migrants. Majority-migrants’ relatively stronger loss in status after migration is expected to cause them to feel more threatened by their host society, creating tensions, conflicts, and stress that block the adoption of host societies’ values (Donà and Berry Citation1994; Ward and Rana-Deuba Citation1999). Given that Western European societies are in general more gender equal than Turkey and Pakistan and that public debates frame Muslim migrants in those terms, majority-migrants may resist internalizing support for gender equality. Minority-migrants, however, are expected to feel less threatened and excluded by their host country, which is expected to ease their acculturation and internalization of support for gender equality. So, assuming that minority-migrants’ experiences of marginalization in their origin country cause them to feel relatively more attuned to their host society, over time, they may internalize its values more strongly than majority-migrants.

Altogether, this leads me to expect that acculturation into support for gender equality differs between minority-migrants and majority-migrants. Whereas minority-migrants may start out as more gender traditional, over time, they can be expected to adopt support for gender equality more strongly than majority-migrants. Therefore, my last hypothesis reads: minority-migrants’ support for gender equality increases more strongly than majority-migrants’ with the time they spend in host countries (hypothesis 3).

Methods and data

This study uses the EURISLAM survey. The EURISLAM fits the aim of this study as it focuses on “the cultural integration of immigrants in general and Muslims in particular” (Hoksbergen and Tillie Citation2016, 6), and the EURISLAM includes (minority) Alevi migrants from Turkey and Ahmadiyya migrants from Pakistan as well as (majority) Sunni migrants from Turkey and Pakistan (in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). Respondents were interviewed via telephone in 2011 and 2012. Although migrants are notoriously difficult to represent, the EURISLAM uses surname-based sampling from phone directories – shown to represent migrant populations well – and also administers questionnaires in the language of the origin countries. Therefore, the EURISLAM probably mitigates the problem of overrepresenting highly-integrated migrants. Response rates were 48.5% for the Turkish group and 41.6% for the Pakistani group. Simultaneously, response rates were markedly higher in the United Kingdom for both groups (due to monetary rewards being used in the UK only) and I will thus also estimate my main models while excluding the UK (results were substantially similar, see Online Appendix Table A2).Footnote1

In line with the aim of this study, I only selected first-generation migrants – who actually experienced their religious minority status in their origin countries – and excluded natives. My initial sample consisted of 1,731 Turkish and Pakistani migrants and, after listwise exclusion of missing values, 1,587 respondents (91.7%) remained. All descriptive statistics are presented in (per-group statistics are in Online Appendix Table A1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (N = 1,587).

Dependent variables: identification and support for gender equality

Identification with origins was measured using the question: “to what extent do you see yourself as [person from the country of origin]?”. Respondents could choose from five answer categories: very strongly, strongly, somewhat, hardly, and not at all. Answers were inverse coded to a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 1 with higher scores representing stronger identification with origins.

Identification with hosts was measured similarly. The same five answer categories to “to what extent do you see yourself as [person from the host country]?” were coded to range from 0 to 1 as well, with higher scores representing stronger identification with hosts.

Support for gender equality was measured using respondents’ agreement with three widely-used statements: “a university education is more important for a boy than for a girl”, “on the whole, men make better political leaders than women do”, and “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” (Glas, Spierings, and Scheepers Citation2018). As the first two were measured on four-point scales – ranging from “agree strongly” to “disagree strongly” – and the last was measured on a three-point scale – “agree”, “neither disagree nor agree”, and “agree” – all were recoded to continuous variables ranging from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater support for gender equality. Factor and reliability analyses showed these items measured the same underlying concept overall and per host country (CAall countries = 0.6), except in the UK. Therefore, I constructed the scale “support for gender equality” by averaging scores on the three items, but as a robustness test I analyzed this scale while excluding the UK as well (results were substantially similar, see Online Appendix Table A2). Additionally, as support for gender equality probably differs between men and women, I ascertained that my results held in per-gender subsamples (see Table A2).

Independent variables

In line with the focus of this paper, belonging to a religious minority distinguishes between Alevi and Ahmadiyya minority-migrants versus Sunni majority-migrants from Turkey and Pakistan. This variable was constructed using information on respondents’ countries of birth and their answers to the question “to which brands of Islam do you belong?”. Respondents who reported to be born in Turkey or Pakistan and identify as Sunnite were coded 0 and respondents who were born in Turkey and identified as Alevi or were born in Pakistan and identified as Ahmadiyya were coded 1. To assess that my results do not depict only one of the two minority groups, as a robustness test, I also included origin minority-majority status II, which distinguishes between Alevi Turks and Ahmadiyya Pakistanis (divergent results are discussed in the main text; see Online Appendix Table A4).

Additionally, to assess whether minority-migrants differently acculturate over time than majority-migrants, I include the years migrants lived in their host country. Respondents were asked “how old are you when you came to [host country]?”; I subtracted this age from respondents’ age at the time of interview to gauge the number of years respondents had lived in their host country. As a robustness test, I also assessed that my results on the years migrants lived in their host country were not influenced by outlying cases by categorizing the number of years migrants lived in their host countries (in 4 and 6 roughly equal-sized categories) and additionally including a moderation with age (results were substantially similar, see Table A2).

Control variables

Because this paper does theoretically aim to explain contextual differences and empirically small group sizes prohibit doing so, I employ flat linear regressions but control for host country (although results were substantially similar in two-level models including random slopes for countries – results upon request). Additionally, I control for socio-demographics (sex, age, educational attainment, marital status, and employment status). To further wield out differences in religiosity as explanations for differences between denominational groups, I control for the frequency of religious service attendance and prayer. My main models also control for respondents’ host language proficiency, and ingroup size and concentrations of minorities in specific neighbourhoods are controlled for in robustness analyses (results were substantially similar, see Online Appendix Table A3).

Analyses

Descriptive results

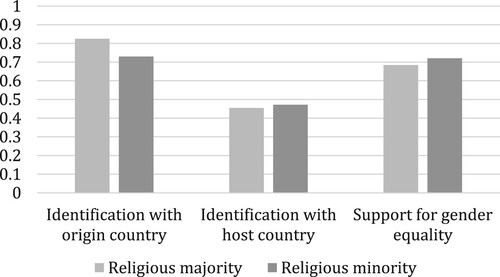

below provides a first, descriptive insight into Muslim migrants’ national identifications and support for gender equality.Footnote2 Generally, minority-migrants seem to be more attuned to their host societies than majority-migrants. On average, migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin countries identify less with their origin nation and more with their host country than majority-migrants. Minority-migrants also seem to support gender equality more than majority-migrants. More broadly, these descriptive results imply that there are differences between minority-migrants and majority-migrants. Echoing my framework, migrants who were religious minorities in their origin countries seem to be more acclimatized to their host society than majority-migrants.

Explanatory analyses

To assess whether these differences between minority-migrants and majority-migrants remain after taking the control variables into account and whether differences are statistically significant, shows the results of linear regression analyses on the three dependent variables.

Table 2. Linear regression analyses (N = 1,587).

Concerning the control variables, my results both underline and contradict insights from the existing literature. First, in line with existing insights, my results imply that religiosity matters for integration outcomes (e.g. Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Fukuyama Citation2006; Scheible and Fleischmann Citation2013). Respondents who attend religious services more frequently identify more with their origins and less with their hosts. Similarly, respondents who pray more often support gender equality less. This implies that stronger religiosity blocks migrants’ cultural integration – although this depends on the dimension of religiosity and the integration outcome studied. However, the limited explained variance implies that migrants’ religiosity is hardly the decisive factor public debates imply it to be. Additionally, my models show that women identify more with origins and less with hosts, which seems to counter understandings that female migrants would acculturate more easily than male migrants (e.g. Itzigsohn and Giorguli-Saucedo Citation2005; Röder and Mühlau Citation2014; Te Lindert et al. Citation2008).

Moving to the main focus of this paper, minority-migrants identify differently than migrants who belonged to the religious majority in their origin country. Minority-migrants identify significantly less with their origin country and more with their host country than majority-migrants. Although we will see below that patterns concerning host identification are more nuanced, these results are in line with hypotheses 1 and 2. As my framework proposed, minority-migrants’ marginalization in their origins and their consequent lower status loss upon migration may cause them to let go off their origin country and feel part of their host country more than majority-migrants.

At the same time, Model 3 finds no significant difference in support for gender equality between minority-migrants and majority-migrants generally. In general, migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country do not support gender equality significantly more than migrants who belonged to the religious majority.

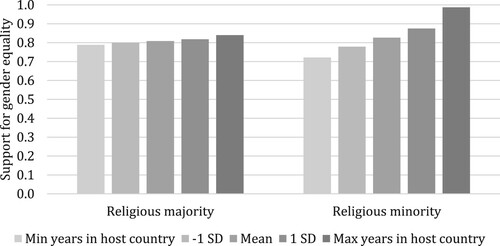

However, Model 4 uncovers that there are differences in support for gender equality between minority-migrants and majority-migrants, but these differences are dependent on the time migrants have lived in their host country. When migrants first arrive in their host society, those who belonged to the religious minority support gender equality less than majority-migrants (0.07 of the 1-point scale less, to be exact; see ). This is in line with my expectation that marginalized groups, as minority-migrants in their origin countries, place special restrictions on “their women” to protect ingroup culture (Ajrouch Citation2004; Giuliani, Olivari, and Alfieri Citation2017; Le Espiritu Citation2001).

Figure 2. The relationship between support for gender equality and origin minority-majority status by the number of years migrants lived in their host country.

Nevertheless, minority-migrants’ support for gender equality increases more strongly with the years they spend in their host countries than majority-migrants’. Across the entire time scope (i.e. between first arrival and having spent 65 years in the host country), majority-migrants’ support for gender equality only increases with 0.05 while minority-migrants’ increases with 0.27. After 21 years, migrants who belonged to the religious minority support gender equality more than majority-migrants. These results support hypothesis 3. It seems that majority-migrants’ greater loss of status upon migration causes them to resist internalizing support for gender equality more than migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country.

Robustness analyses: gender and disaggregated minority groups

These patterns are replicated throughout robustness tests (see Online Appendix Table A2) and, importantly, hold regardless of migrants’ gender. Among both male migrants and female migrants, religious minorities’ support for gender equality increases more strongly over time than religious-majorities’ (see Figures A1a and A1b in the online Appendix). Interestingly, female migrants who belonged to the religious majority in their origin country do not seem to acculturate at all. Rather counterintuitively, both male majority- and male minority-migrants’ support for gender equality increases more than female majority-migrants’. Additional research is needed to thoroughly address why this could be the case, although it could imply that women resist acculturation more when they feel marginalized than men do.

Second, my main findings above compound Alevi and Ahmadiyya migrants into one minority group, which means that my results could be driven by only Alevi Turks or Ahmadiyya Pakistanis. Separating the two minorities (in origin minority-majority status II) shows that my results concerning identification with origins and acculturation into support for gender equality are robust in the sense that they are not driven by one particular minority group (see Online Appendix Table A4). However, interestingly, only Ahmadiyya Pakistani migrants identify more with their host country than Sunni migrants; there is no significant difference in host identification between Alevi Turks and Sunni migrants, which generally rejects hypothesis 2 for the Turkish group. However, further analyses show that Turkish Alevi migrants identify significantly less with their host societies upon arrival, but after 30 years they identify more strongly with their hosts than Sunni migrants (see Model A14 in Table A4).

These results are partly in line with my theory: minority-migrants seem to feel relatively more included in their host societies than in their origin societies, fuelling their host identification more than majorities’. However, these results also feed back into my proposals: while some minority-migrant groups consequently immediately identify more with their host societies, for other groups feeling included takes time. Pakistani Ahmadis may immediately experience the relatively greater inclusion in host societies compared to origins, while Turkish Alevis feel out the situation. Tentatively, this difference may be the result from Turkish Alevi migrants being less marginalized in their origin societies than Pakistani Ahmadiyya migrants, as Alevis have also had allegiances with secular regimes. Consequently, the difference in inclusion after migration may be clearer to Pakistani Ahmadiyya migrants upon arrival, whereas their relatively changed status may only be experienced by Turkish Alevi migrants over time. Of course, presently this remains conjecture, and future research is needed to assess why identifying with host societies takes more time for some minority-migrant groups than others.

Conclusion

Prominent voices in Western public debates proclaim that Muslims have turned their backs on Western societies’ core values (Röder Citation2014; Ghorashi Citation2010; Horsti Citation2008). Echoing those sentiments, existing quantitative studies have argued that Muslims’ religious interpretations cause them to identify more with their origin countries, identify less with their host societies, and support gender equality less than others (Diehl, Koenig, and Ruckdeschel Citation2009; Koopmans Citation2015; Martinovic and Verkuyten Citation2016; Statham et al. Citation2005; Zimmermann, Zimmermann, and Constant Citation2007).

The present study has argued that this line of thought overlooks that denominations also demarcate groups with varying social, economic, and political power (as argued by Banfi, Gianni, and Giugni Citation2016). Sunni migrants who belonged to the religious majority in their origins can longingly look back to their origin countries, whereas those countries politically, legally, and socially marginalized Alevi and Ahmadiyya minority-migrants, who consequently probably feel relatively more attuned to their host society (Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey Citation1999; Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Turner et al. Citation1984). Up to now, this influence of origin minority-majority status has been given little attention, which may mean that some of the differences between migrants with different denominational groups could have been misinterpreted.

I tested the importance of belonging to the religious minority or majority in origins using EURISLAM data on Sunni majority-migrants and Alevi and Ahmadiyya minority-migrants from Turkey and Pakistan. Regression analyses showed that migrants who belonged to the religious minority in their origin country identify less with their origin country and, over time, more with their host country than majority-migrants. In line with my framework, minority-migrants’ greater marginalization prior to migration may cause them to turn away from their origin country, whereas majority-migrants face relatively greater marginalization in their host society, causing them to remain separated from their host country.

Second, my analyses showed that acculturation into support for gender equality differs between minority-migrants and majority-migrants. Among recent arrivals, minority-migrants support gender equality less than majority-migrants, which is in line with gender scholars’ assertations that marginalized groups emphasize traditional roles for “their” women to protect in-group culture (Ajrouch Citation2004; Giuliani, Olivari, and Alfieri Citation2017; Le Espiritu Citation2001). However, this difference shrinks and eventually reverses. Majority-migrants do not seem to internalize support for gender equality much over time, while minority-migrants increasingly adopt support for gender equality in their host societies. In line with my framework, majority-migrants’ relatively greater marginalization after migration seems to cause them to resist adopting the host society’s values and reassert the virtue of the traditional gender values for which Western public debates chastise them (Röder Citation2014; Ghorashi Citation2010; Horsti Citation2008).

More generally, this paper shows that while Muslim migrants are often portrayed as one group that rejects “Western core values”, there exists great diversity among Muslim migrants in cultural acculturation processes. At the same time, what is underlying those differences could be interpreted in two ways. Either migrants who belonged to the minority in their origin countries acculturate faster or the Alevi and Ahmaddiyya faiths are “more humanist” (e.g. Koopmans Citation2015; Verkuyten and Yildiz Citation2009). This study cannot completely rule out either option. However, my results give the edge to the importance of origin minority-majority status. Differences between denominational groups remain after taking religiosity in terms of mosque attendance and private prayer into account. Pivotally, I find that the position of denominational groups shifts. When recently arrived, Sunnites support gender equality more, while over time, Alevi and Ahmadiyya migrants support gender equality more. My results show similar shifts among Alevis and Sunnites in their host society identification. These shifts cannot be accounted for by pointing to a static religious conception of “the humanist Alevi and Ahmadiyya faith”. The shifting power balance in minority status can, however, account for them. More generally, these findings again emphasize that thinking in homogeneous denominational blocks (be they “Muslims versus non-Muslims” or “Alevi and Ahmadiyya versus Sunni Muslims”) cannot explain their internal diversity we observe in social reality.

Future work can expand upon the current findings in two ways. First, although my analyses imply that differences in support for gender equality between majority-migrants and minority-migrants change over time, panel data could shed more light on whether this truly reflects within-individual differences. However, my results indicate panel data would need to cover quite a long time (at least about ten years), and I am unaware of any existing panel data that include a substantial number of marginalized minority-migrants and dominant majority-migrants that fulfil this criterium. If longer-term panel data do become available, it would technically be most interesting to also assess migrants’ values prior to migration, seeing as migrants don’t start their lives point-blank in their destination countries – however, this may be impossible for practical reasons.

Third, religious minorities beside Alevi Turks and Ahamdiyya Pakistanis and religious majorities other than Sunni Turks and Pakistanis should also be studied to ascertain the generalizability of this study’s results. For instance, especially Ahmadiyya Pakistani migrants are relatively strongly marginalized; they have been marginalized politically, legally, and socially, and have been involved in sectarian clashes (Erman and Göker Citation2000; Grigoriadis Citation2006; Kose Citation2013; Saeed Citation2007), and it is unclear how national identifications and gender equality are structured among less strongly marginalized groups. Relatedly, in its current form, my theoretical framework implies that the differences I find should hold for any dominant majority and any marginalized minority. However, this paper already noted that identification with host societies works differently for different minority-migrant groups. It thus seems likely that the patterns I propose are context-dependent – shaped by both the origin country and the host country, and consequently the migrant community (Van Tubergen Citation2006; Van Tubergen, Maas, and Flap Citation2004). Future scholars could thus extend upon my framework by identifying for what majority- and minority-migrant groups my patterns hold and how contexts condition the relations between origin minority-majority status and integration outcomes.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study has contributed to the literature by laying bare its blind spot on interpretations of denominational differences in integration outcomes. Current public debates portray Muslims as having fixed religious interpretations that cause them to turn their backs on their Western host society and its core values (Röder Citation2014; Ghorashi Citation2010; Horsti Citation2008). These debates have left their mark on scholarly work, which also tends to think of Muslim migrants in terms of their religiosity (Fukuyama Citation2006; Huntington Citation1996; Norris and Inglehart Citation2012). The present study has shown that this focus on essentialist views of Muslims’ religion overlooks that other mechanisms may be in play as well. Next to individual religiosity, denominational categories also reflect non-religious mechanisms stemming from different political, social, and economic positions, to which future studies should pay greater attention.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (47.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 More information on the surveys can be found in the EURISLAM codebook.

2 This figure is used to introduce readers to the average levels in my sample. A formal test of hypotheses will be conducted later in multivariate analyses.

References

- Ajrouch, K. 2004. “Gender, Race, and Symbolic Boundaries: Contested Spaces of Identity among Arab American Adolescents.” Sociological Perspectives 47 (4): 371–391.

- Banfi, E., M. Gianni, and M. Giugni. 2016. “Religious Minorities and Secularism: An Alternative View of the Impact of Religion on the Political Values of Muslims in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 292–308.

- Bloom, P. B. N., and G. Arikan. 2013. “Religion and Support for Democracy: A Cross-National Test of the Mediating Mechanisms.” British Journal of Political Science 43 (2): 375–397.

- Bozorgmehr, M. 1997. “Internal Ethnicity: Iranians in Los Angeles.” Sociological Perspectives 40 (3): 387–408.

- Branscombe, N. R., M. T. Schmitt, and R. D. Harvey. 1999. “Perceiving Pervasive Discrimination among African Americans: Implications for Group Identification and Well-Being.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (1): 135.

- Braun, R. 2016. “Religious Minorities and Resistance to Genocide: the Collective Rescue of Jews in the Netherlands During the Holocaust.” American Political Science Review 110 (1): 127–147.

- Diehl, C., M. Koenig, and K. Ruckdeschel. 2009. “Religiosity and Gender Equality: Comparing Natives and Muslim Migrants in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (2): 278–301.

- Dommelen, A. van, K. Schmid, M. Hewstone, K. Gonsalkorale, and M. Brewer. 2015. “Construing Multiple Ingroups: Assessing Social Identity Inclusiveness and Structure in Ethnic and Religious Minority Group Members.” European Journal of Social Psychology 45 (3): 386–399.

- Donà, G., and J. W. Berry. 1994. “Acculturation Attitudes and Acculturative Stress of Central American Refugees.” International Journal of Psychology 29 (1): 57–70.

- Engbersen, G., L. Bakker, M. B. Erdal, and Ö Bilgili. 2014. “Transnationalism in a Comparative Perspective: An Introduction.” Comparative Migration Studies 2 (3): 255–260.

- Erman, T., and E. Göker. 2000. “Alevi Politics in Contemporary Turkey.” Middle Eastern Studies 36 (4): 99–118.

- Evans, G., and A. Need. 2002. “Explaining Ethnic Polarization Over Attitudes Towards Minority Rights in Eastern Europe: A Multilevel Analysis.” Social Science Research 31 (4): 653–680.

- Fokkema, T., and H. De Haas. 2015. “Pre-and Post-Migration Determinants of Socio-Cultural Integration of African Immigrants in Italy and Spain.” International Migration 53 (6): 3–26.

- Fukuyama, F. 2006. “Identity, Immigration, and Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 17 (2): 5–20.

- Ghorashi, H. 2010. “From Absolute Invisibility to Extreme Visibility: Emancipation Trajectory of Migrant Women in the Netherlands.” Feminist Review 94 (1): 75–92.

- Giuliani, C., M. G. Olivari, and S. Alfieri. 2017. “Being a “Good” son and a “Good” Daughter: Voices of Muslim Immigrant Adolescents.” Social Sciences 6 (4): 142.

- Glas, S., N. Spierings, and P. Scheepers. 2018. “Re-Understanding Religion and Support for Gender Equality in Arab Countries.” Gender & Society 32 (5): 686–712.

- Grigoriadis, I. N. 2006. “Political Participation of Turkey’s Kurds and Alevis: A Challenge for Turkey’s Democratic Consolidation.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 6 (4): 445–461.

- Hoksbergen, H., and J. Tillie. 2016. Eurislam Codebook Survey-data (WP-III).

- Horsti, K. 2008. “Europeanisation of Public Debate: Swedish and Finnish News on African Migration to Spain.” Javnost-The Public 15 (4): 41–53.

- Huntington, S. P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Itzigsohn, J., and S. Giorguli-Saucedo. 2005. “Incorporation, Transnationalism, and Gender: Immigrant Incorporation and Transnational Participation as Gendered Processes.” International Migration Review 39 (4): 895–920.

- Kavli, H. C. 2015. “Adapting to the Dual Earner Family Norm? The Case of Immigrants and Immigrant Descendants in Norway.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (5): 835–856.

- Kieser, H. L. 2001. The Alevis’ Ambivalent Encounter with Modernity: Islam, Reform and Ethnopolitics in Turkey (19th-20th cc.). Anthropology, Archaeology and Heritage in the Balkans and Anatolia or The Life and Times of FW Hasluck (1878-1920), University of Wales.

- Koopmans, R. 2015. “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility Against out-Groups: A Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (1): 33–57.

- Kose, T. 2013. “Between Nationalism, Modernism and Secularism: The Ambivalent Place of ‘Alevi Identities’.” Middle Eastern Studies 49 (4): 590–607.

- Le Espiritu, Y. 2001. “We Don't Sleep Around Like White Girls do”: Family, Culture, and Gender in Filipina American Lives.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 26 (2): 415–440.

- Lu, X. 2019. “Identity Construction among Twice-Minority Immigrants: A Comparative Study of Korean-Chinese and Uyghurs in the United States.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1577725

- Martinovic, B., and M. Verkuyten. 2016. “Inter-Religious Feelings of Sunni and Alevi Muslim Minorities: The Role of Religious Commitment and Host National Identification.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 52: 1–12.

- Min, P. G. 2013. “The Attachments of New York City Caribbean Indian Immigrants to Indian Culture, Indian Immigrants and India.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (10): 1601–1616.

- Norris, P., and R. F. Inglehart. 2012. “Muslim Integration into Western Cultures: Between Origins and Destinations.” Political Studies 60 (2): 228–251.

- Pessin, L., and B. Arpino. 2018. “Navigating between Two Cultures: Immigrants’ Gender Attitudes Toward Working Women.” Demographic Research 38: 967.

- Roccas, S., and M. B. Brewer. 2002. “Social Identity Complexity.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 6 (2): 88–106.

- Röder, A. 2014. “Explaining Religious Differences in Immigrants’ Gender Role Attitudes: The Changing Impact of Origin Country and Individual Religiosity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (14): 2615–2635.

- Röder, A., and P. Mühlau. 2014. “Are They Acculturating? Europe's Immigrants and Gender Egalitarianism.” Social Forces 92 (3): 899–928.

- Saeed, S. 2007. “Pakistani Nationalism and the State Marginalisation of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan.” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 7 (3): 132–152.

- Scheible, J. A., and F. Fleischmann. 2013. “Gendering Islamic Religiosity in the Second Generation: Gender Differences in Religious Practices and the Association with Gender Ideology among Moroccan-and Turkish-Belgian Muslims.” Gender & Society 27 (3): 372–395.

- Spierings, N. 2015. “Gender Equality Attitudes among Turks in Western Europe and Turkey: The Interrelated Impact of Migration and Parents’ Attitudes.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (5): 749–771.

- Spierings, N. 2019. “The Multidimensional Impact of Islamic Religiosity on Ethno-Religious Social Tolerance in the Middle East and North Africa.” Social Forces 97 (4): 1693–1730.

- Statham, P., R. Koopmans, M. Giugni, and F. Passy. 2005. “Resilient or Adaptable Islam? Multiculturalism, Religion and Migrants’ Claims-Making for Group Demands in Britain, the Netherlands and France.” Ethnicities 5 (4): 427–459.

- Tajfel, H., and J. Turner. 1979. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Te Lindert, A., H. Korzilius, F. J. Van de Vijver, S. Kroon, and J. Arends-Tóth. 2008. “Perceived Discrimination and Acculturation among Iranian Refugees in the Netherlands.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 32 (6): 578–588.

- Trieu, M. M. 2013. “The Role of Premigration Status in the Acculturation of Chinese–Vietnamese and Vietnamese Americans.” Sociological Inquiry 83 (3): 392–420.

- Turner, J. C., M. A. Hogg, P. J. Turner, and P. M. Smith. 1984. “Failure and Defeat as Determinants of Group Cohesiveness.” British Journal of Social Psychology 23: 97–111.

- Van Tubergen, F. 2006. Immigrant Integration: A Cross-National Study. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC.

- Van Tubergen, F., I. Maas, and H. Flap. 2004. “The Economic Incorporation of Immigrants in 18 Western Societies: Origin, Destination, and Community Effects.” American Sociological Review 69 (5): 704–727.

- Verkuyten, M., M. Maliepaard, B. Martinovic, and Y. Khoudja. 2014. “Political Tolerance among Muslim Minorities in Western Europe: The Role of Denomination and Religious and Host National Identification.” Politics and Religion 7 (2): 265–286.

- Verkuyten, M., and B. Martinovic. 2012. “Immigrants’ National Identification: Meanings, Determinants, and Consequences.” Social Issues and Policy Review 6 (1): 82–112.

- Verkuyten, M., and A. A. Yildiz. 2009. “Muslim Immigrants and Religious Group Feelings: Self-Identification and Attitudes among Sunni and Alevi Turkish-Dutch.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (7): 1121–1142.

- Ward, C., and A. Rana-Deuba. 1999. “Acculturation and Adaptation Revisited.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 30 (4): 422–442.

- Zaman, M. Q. 1998. “Sectarianism in Pakistan: The Radicalization of Shi‘i and Sunni Identities.” Modern Asian Studies 32 (3): 689–716.

- Zimmermann, L., K. F. Zimmermann, and A. Constant. 2007. “Ethnic Self-Identification of First-Generation Immigrants.” International Migration Review 41 (3): 769–781.