ABSTRACT

This article examined the intergenerational transmission of dual identity in Turkish immigrant families in Europe using data from 2000 Families: Migration Histories of Turks in Europe. This project gathered information about Turkish immigrants and their children in seven Western European countries provided material to compare two generations’ dual identities. We conducted multinomial logistic regression analyses with standard errors clustered at the family level to study these intergenerational transmissions. We find that immigrant parents’ dual identities correlate positively with their adult children's dual identities. Our study showed that this effect was influential even in these children's adult lives and offers a contribution to the literature on the transmission of dual identities. We also found that mothers in Turkish immigrant families had a stronger effect than fathers on identity transmission.

Introduction

Identification is understood as belonging to the emotional sociocultural dimension of an immigrant integration process. It is usually seen as the final step of a long intergenerational incorporation process, in which immigrants and their offspring eventually come to fully identify nationally and merge with the mainstream (Alba and Nee Citation1997). In this process, national identification often goes hand in hand with some sense of belonging to one's own country of origin or that of one's parents. This dual identity, some scholars even argue, is desirable because it gives immigrants and their children sufficient identification with a subgroup to experience basic security and sufficient identification with the receiving society (González and Brown Citation2003, Citation2006; Klandermans, Van der Toorn, and Van Stekelenburg Citation2008). Since identification is an intergenerational process, benchmarks should not be sought so much in the identity of immigrants themselves, but in that of their offspring.

The family unit has long been recognized as core to the formation of attitudes among immigrant children and adolescents (Hughes et al. Citation2006; Casey and Dustmann Citation2010). It is believed that parents not only influence the identity formation of their children, but that children copy and further develop levels of identity. Knowing that immigrant parents, along with their various attitudes and stocks of capital, influence the position of their children across domains – educational outcomes (Crul and Doomernik Citation2003), labour market trajectories (Hermansen Citation2016), friendships and marriages (Huijnk and Liefbroer Citation2012; Carol Citation2016), but also ethnic, national, (Casey and Dustmann Citation2010) and ethno-religious identity formation (Soehl Citation2017) – we also expect dual identity levels to correlate between immigrant parents and their children.

Wiley et al. (Citation2019, 618) propose that “that dual identity will develop primarily when a sense of belonging to the receiving society is added to a pre-existing and maintained strong sense of belonging to the immigrant community”. Furthermore, they argue that existing research cannot draw final conclusions as there are not many empirical studies on dual identity for the second- or later generation immigrants that takes a long-term perspective. Our focus in this article is on intergenerational transmission of dual identity, which we analyse using data that also allows us to look for separate effects of fathers and mothers in the transmission process.

This study contributes to the existing research in three profound ways. First, it shines light on internationally comparative research into the intergenerational transmission of identity among immigrant-origin groups within the European context. Most studies have focused on a single country (see Casey and Dustmann Citation2010; Sabatier Citation2008; Sabatier and Berry Citation2008; Nauck Citation2001; Verkuyten, Thijs, and Stevens Citation2012). While other research across different European countries has examined intergenerational transmission of cultural values (e.g. Phalet and Schönpflug Citation2001), partner choice (Carol Citation2016), and religiosity (e.g. De Hoon and Van Tubergen Citation2014), these inheritance processes differ from that of dual identity. Second, this study considers the intergenerational transmission of a dual identity as something separate from the transmission of parents’ national or ethnic identities. To reiterate, a dual identity is a combination of national and ethnic identities, with ethnic identity being defined as feeling connected to the immigrant community of which one is a member (Phinney et al. Citation2001). This definition of dual identity acknowledges the complexity of identity formation and the identity combinations that can impact the behaviour and well-being of immigrant-origin individuals (e.g. Berry Citation1997; Martiny et al. Citation2017). Third, this study focuses on adult offspring, whereas most have looked at immigrant-origin parents and their children as adolescents (for an overview, see Hughes et al. Citation2006; Sabatier Citation2008; Sabatier and Berry Citation2008; Verkuyten, Thijs, and Stevens Citation2012). A later-life study permits us to see whether the intergenerational transmission of social identity “sticks”. Younger children are likelier to unquestioningly adopt parents’ views and attitudes (Verkuyten and Fleischmann Citation2017), which makes a correlation between parents’ and their children's identities also likelier. However, as children grow up, they tend to become more critical of their parents’ views, attitudes, and beliefs (Verkuyten and Fleischmann Citation2017). Fourth, we take seriously the tentative finding that intergenerational identity transmission in immigrant families seems to have a strong gender dimension. We therefore distinguish effects between fathers and mothers when it comes to transmission of dual identity levels to their adult children.

This article draws on data from 2000 Families: Migration Histories of Turks in Europe (Guveli CitationND; Guveli et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b), a project that set out to examine the intergenerational transmission of dual and national identities in families with Turkish immigration backgrounds in Europe. The information that 2000 Families gathered about Turkish immigrants and their children in seven Western European countries provided material to compare two generations’ dual identities. To analyse the intergenerational transmission of dual identities, we conducted multinomial logistic regression analyses with standard errors clustered at the family level. As one of the largest immigrant groups in Europe (Guveli et al. Citation2016a), Turkish immigrants provide a rich case study on this topic. Their ethnic identity levels tend to be high (Carol, Ersanilli, and Wagner Citation2014; Çelik Citation2015), making dual identities and their transmission to children an important acculturation strategy. Furthermore, the highly gendered stratification of the Turkish family system makes it all the more interesting to track the identity transmission of fathers and mothers separately (Phalet and Schönpflug Citation2001).

Acculturation and identity formation

Immigrants’ national identities have been used primarily to study sociocultural and emotional dimensions of the integration process (Platt Citation2014; Warikoo Citation2005). Traditionally, theories on migrant adaptation consider an increased – and ultimately exclusive – identification with the host society as the final step for migrants to merge with the mainstream (Alba and Nee Citation1997). This acculturation process, which is marked by a decrease in ethnic identification, is thought to be a long, gradual, and partly unconscious process. It is frequently assumed to necessitate study through the process of generational change, whereby children of immigrants generally display higher levels of host-society national identity than their parents (Alba Citation1990; Maliepaard, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2010). Within this framework, ethnic and national identities are understood as reflecting a sense of belonging to cultural groups and having feelings associated with group memberships. Belonging is an important source of social identity (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979) since people attribute value to these groups and derive self-esteem from feeling included. Ethnic and national identities thus play an important role in how immigrants and their descendants see themselves. This self-concept directly links to the fundamental human desire to form balanced identities. Balance is achieved when membership in a particular group is self-evaluated as something positive and socially appreciated by the networks in which the individual is embedded (Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016).

Choices that immigrants make with regard to the composition of their social networks (Schrover and Vermeulen Citation2005), their sense of belonging, and the importance they attach to preserving certain cultural perceptions and patterns are referred to as acculturation strategies. The literature generally distinguishes four types of strategies: assimilation, integration, segregation, and marginalization (Berry Citation1997; Phillimore Citation2011). To what extent immigrants and their offspring orientate their social, emotional, and cultural focuses on the origin group and/or on the settlement society is the what defines these strategies. Immigrants who identify principally with an ethnic group are categorized as separate. Assimilation applies to immigrants who identify predominantly with the new national identity. Those with a dual identity, to both their ethnic group and the new country, are considered integrated. And marginalized immigrants are those without significant levels of either ethnic and national identity (Berry Citation1997; Verkuyten and Martinovic Citation2012; De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014).

Dual identities

Identifying with one's own ethnic group was long thought by scholars to have an inverse correlation with identifying with other groups, particularly the majority group. Yet, immigrants and their descendants often identify, to differing degrees and with changes over time, with both the ethnic and national groups (Berry Citation1997; Benet-Martínez et al. Citation2002; Verkuyten and Martinovic Citation2012; Martiny et al. Citation2017). To identify with one group is therefore not necessarily a zero-sum game vis-à-vis other group identities. Through the lens of social identity, Verkuyten, Thijs, and Stevens (Citation2012) found reasons to expect most immigrants to prefer a dual identity over any other type. It was assumed they preferred to be socially recognized, accepted, and valued by their immediate social network as well as the society in which they lived. A one-sided focus on commonalities and national identity could be threatening for immigrants if they still identified with the ethnic group and mostly remained embedded in ethnic social networks. A complete focus on ethnic identity might conflict with how this identity would be received in the individual's wider social environment. In their review of acculturation, Benet-Martínez et al. (Citation2002) illustrate that some biculturals (second generation immigrants having some level of dual identity) perceive their dual cultural identities as mutually compatible and integrated, whereas others see them as oppositional and difficult to integrate.

Dual identification among immigrants and their children leads to better mental health (Nguyen and Benet-Martínez Citation2013), better educational outcomes (Baysu and Phalet Citation2019) and a stronger sense of political consciousness (Kranendonk, Vermeulen, and van Heelsum Citation2018). Immigrants with dual identities are also in a position to bridge divides between different groups (Wiley et al. Citation2019; Love and Levy Citation2019). With their overall high dual identity levels, members of the second generation are especially capable of moving easily between different cultural meaning systems (Benet-Martínez et al. Citation2002).

The gendered role of families in identity formation

Families are seen as the primary socializing agents of identities and the ground zero for their development (e.g. Hughes Citation2003; Casey and Dustmann Citation2010). These identities are then internalized by children and can serve as foundations for interactions later in life (Carter Citation2014). Hughes et al. (Citation2006, 755) propose “the term cultural socialization to refer to parental practices that teach children about their racial or ethnic heritage and history; that encourage cultural customs and traditions; and that promote children's cultural, racial, and ethnic pride, either deliberately or implicitly”. All these factors influence the extent to which children identify with their ethnic group (Else-Quest and Morse Citation2015). As parents play a formative role in their child's development of ethnic identity and because immigrant parents usually identify strongly with their ethnic group, they are often quick to transmit their ethnic identity and related norms and values to their children (Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016). Similar mechanisms with a different end goal can lead to mainstream socialization, resulting in higher national identity levels. For example, rather than orienting children around their minority status, parents can steer them towards developing traits and skills to thrive in settings that are part of the mainstream or dominant culture. Such orientation is often believed to enhance opportunities for children to succeed in the host society (Esser Citation2004).

Immigrant parents’ levels of acculturation – whether dominated by a sense of belonging to the ethnic group, the dominant group, or a combination of the two – is thus expected to strongly influence the development of their children's group identity. Parents for whom race or ethnic background is a major source of social identity are likeliest to transmit messages emphasizing group pride, but also minority status (Hughes et al. Citation2006; Kwak Citation2003). Similarly, parents who strongly identify with the host society are expected to discuss issues related to host-society institutions such as school, politics, and specific local matters. Introducing their children to these specific issues, values, and societal elements transmits the parents’ sense of host-state belonging. Similarly patterned levels of commitment to ethnic or national issues are thus expected across generations (Phinney Citation1990; Kester and Marshall Citation2003). Using a longitudinal dataset on immigrants and their children in Germany, Casey and Dustmann (Citation2010) observed a strong intergenerational transmission of ethnic-group and host-country identity from one generation to the next. Sabatier (Citation2008) found that parents contributed to the transmission of both ethnic and national identities. Verkuyten, Thijs, and Stevens (Citation2012) noted how Dutch-Moroccan parents’ religious, ethnic, and national identities positively correlated with these identities among their adolescent children. Similar dual identity transmission patterns can therefore be expected between immigrant parents and their children.

In particular contexts, parents may be more reluctant to transmit ethnic identity than national identity to their children. Ethnic and national identities are often discussed within heated debates on larger issues such as loyalty and belonging, whereas the popular public notion – especially for marginalized groups – is that ethnic and national identities cannot harmoniously coexist. Scholars have researched how immigrants’ identity interacts with contextual national circumstances, such as acculturation expectations or public discourse, in the destination countries (e.g. Ersanilli and Koopmans Citation2011; Phinney et al. Citation2001; Crul and Schneider Citation2010; Van Heelsum and Koomen Citation2016). Some countries’ policies might also be designed to influence the acculturation processes of immigrant-origin individuals (Berry Citation1997), and are shown to affect preferences for acculturation strategies (Groenewold, de Valk, and van Ginneken Citation2014). Moreover, parents might feel that their ethnic social capital – and thus ethnic identity – is less useful for their children's social mobility than social capital derived outside the immigrant community (Esser Citation2004). If parents worry their ethnic identity could one day harm their children, they might refrain from transmitting it (Casey and Dustmann Citation2010), especially if they feel that retaining an ethnic identity clashes with host-country acculturation expectations (e.g. Berry Citation1997). National contexts that accommodate and provide opportunities for a more multicultural plural identity formation are generally expected to allow higher levels of different forms of identity formation – be it ethnic, national, or a combination of the two (Phalet and Schönpflug Citation2001).

The transmission of beliefs and attitudes in immigrant families and the identity formation of immigrant children also seems to be strongly influenced by gender as a factor (Phalet and Schönpflug Citation2001). Immigrant fathers and mothers are generally expected to play distinct roles in family socialization by taking on different tasks in the parenting process, but also by emphasizing different values to their children. Women often serve as keepers of tradition and culture, especially in immigrant communities with collective family cultures (Orsi Citation1992; Warikoo Citation2005). Koh, Shao and Wang (Citation2009) found that Asian-American mothers stressed the importance of helping children develop a sense of their ethnic culture identity. They expressed concern that if children had no knowledge of their ethnic culture, they would have no sense of belonging and their future life would be difficult. Carol’s (Citation2016) case study of Turkish families in Germany, France, and the Netherlands emphasized the role mothers play in processes of cultural transmission in immigrant families. In most families she studied, the mother, rather than the father, passed down values and beliefs to the next generation, especially to daughters. For Casey and Dustmann (Citation2010), mothers turned out to be more involved in the transmission of ethnic identity and fathers in the transmission of national identity. They also found that daughters were influenced more by their mothers’ identities than their fathers’ and sons were influenced more by their fathers’ identities than their mothers’. In Canadian-Chinese families across generations, Kester and Marshall (Citation2003) observed similar ethnic identity levels that correlated between mothers and daughters only, rather than mothers and sons or fathers and either sons or daughters.

Other important factors for the formation of ethnic and national identities in families include language proficiency and social networks. For ethnic identity, this concerns proficiency in the language of the immigrant group (those who speak the language are expected to develop stronger ethnic identities) and having friends within the same immigrant community (those with many similar immigrant friends are expected to develop stronger ethnic identities) (Phinney et al. Citation2001). For national identity, the reverse is expected. Higher host-country language proficiency and use and more social contacts with majority group members predict stronger national identity (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014; Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016) and dual identity (Martiny et al. Citation2017). Parents’ decision to speak ethnic, national, or both languages with their children is also a significant, even if indirect, consequence of family dynamics. Even though social networks mostly develop outside the family, parents may influence their children's choices in friends and eventually also partners.

Based on the literature thus far referenced, we formulate the following hypotheses for identity transmission in the immigrant family unit:

Hypothesis 1: Parents’ dual identities positively correlate with their adult children's dual identities.

Hypothesis 2: Mothers play a stronger role than fathers in the transmission of identities to their children.

Data and methods

The 2000 Families project sought to compare data on Turkish parents and their children (Guveli, CitationND) with non-migrants across multiple generations and multiple destination countries. (Guveli et al. Citation2016a). The origin regions included for the 200 Families project are Acıpayam, Akçaabat, Emirdağ, and Kulu. These regions were selected because they were significant sending regions of 1960s’ labour migrants and incorporated a diversity of destination countries (Guveli et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Spierings Citation2016). The destination countries included in the 2000 Families project are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

Data were collected between 2010 and 2012 in the above-mentioned regions in Turkey using a two-stage screening process (Ganzeboom and Sözeri Citation2013; Spierings Citation2016; Guveli et al. Citation2016a; Citation2016b). Researchers used a clustered probability sample to select 100 primary sampling units in each region and from there respondents were systematically approached and selected until the sample comprised 80 per cent migrant families. Response rates were high.

The sample comprises adult men aged 65 years and above (G1) and their children (women and men) and grandchildren (women and men). Of each parent (G1), one or two adult children were interviewed using the same questionnaire (G2), and one or two children were included (G3) in a similar manner. (Spierings Citation2016, 21)

The data includes information such as migration history, social identity, socioeconomic status, and demographic characteristics of parents and their adult children (Spierings Citation2016; for more information about this dataset, see Ganzeboom and Sözeri Citation2013; Guveli et al. Citation2016b). In this study, child–parent dyads of the G2-G3 and G1-G2 respondents were used. We combined the dyads for the analysis of dual identities in order to have larger groups of respondents. Through robustness checks, we made sure that the results held for the separate dyads. We also included interaction effects with the gender of the parent for the G2-G3 dyad.

The analyses include 810 observations. We used multinomial regression analyses to study the dual identities. Clustered standard errors at the family level were included to account for the nested structure of the data, the intra-class correlation, where respondents were nested within their family. Individuals within one family might resemble each other more in comparison to individuals from other families, this is taking into account statistically. Dummies for country and region of origin were included as control variables. As a robustness test, the destination countries were also omitted one at a time to explore whether results were driven by one particular country. The results were similar to the analyses that include all countries, as shown in this article's results section.

Operationalization

Dependent variables

A categorical variable was constructed for parents and children for the three types of acculturation strategy: (1) marginalized or separated (for simplicity, we combined these two separate acculturation strategies), (2) assimilated, and (3) integrated – another way to refer to the dual identity that is the focus of this article. These variables were constructed by separating Turkish and national identities into two categories and then combining them. People who indicated feeling not at all, hardly, or somewhat connected to other people from Turkey were grouped as low Turkish identifiers (totalling 30.7 per cent for the adult children). People who indicated feeling mostly or entirely connected to other people from Turkey were grouped as high Turkish identifiers (totalling 69.3 per cent for the adult children). This same process was done for connectedness to country nationals (host country), after which the low and high Turkish and national identifiers were combined to create groups corresponding to the three acculturation strategies categories.

shows the distribution of these three groups among the G1-G2 and G2-G3 parents and children. In line with previous studies (for intergenerational differences, see e.g. Maliepaard, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2010), we observed that fewer children have a marginalized or separated identity than their parents. also shows that more children have assimilated and integrated acculturation strategies than their parents.

Table 1. Combined Turkish and national identities in percentages G1, G2, G3.

Independent variables

Genders of parents and children were included in the models as control variables and interacted with the parents’ identity. We did this to explore whether the mother's identity had different effects on her children's identity than the father's (hypothesis 2).

Whether the parents lived in the same country, in Turkey (as a return migrant), in or a different European country than the child's was accounted for by constructing a variable based on the country of residence (1: parents live in Turkey; 2: parents live in the same European country; 3: parents live in another European country). We also took the frequency of contact between the child and parents into account via the question: “How often are you in touch with your parents?” (with answers ranging from 1: once a month or less to 4: daily). First-generation migrants, second-generation migrants, and second-generation migrants who migrated within Europe were also distinguished.

We know that identity processes among immigrant parents and their adult children are also influenced by social contexts besides family (Carter Citation2014), such as schools (Sabatier Citation2008). The type of education completed or attended (with answers ranging from 1: extended primary school to 8: lower tertiary) was included in the models, as well as whether the respondent completed schooling in Turkey or a European country. The latter was measured via the question: “In which country did you finish your education?” and recoded as a variable that indicated whether a respondent finished in Turkey or a European country. We also know that other social contexts facilitating identity experiences and exploration are social networks and friendships (e.g. Nauck Citation2001; Sabatier Citation2008; Phinney et al. Citation2001; Martiny et al. Citation2017). The relative number of Turkish friends was therefore included in the models via the question: “What portion of your friends is Turkish or from Turkey?” (with answers ranging from 1: a quarter or less to 4: almost all of them). The data did not contain information about the relative number of friends originating from the destination country.

For immigrants and their children in particular, discrimination can influence social identity (Sabatier Citation2008) and acculturation processes (Berry Citation1997) since it emphasizes group boundaries and perceived differences. In our study, whether someone was insulted during the last 12 months was included (via a yes or no response). Language proficiency has also been shown to play an important role in social identity processes (see e.g. Phinney et al. Citation2001). Proficiency in the host country's language was therefore included (measured via speaking and writing scales), as was Turkish speaking and writing proficiency, measured via the question: “How well would you say you speak/write [COUNTRY LANGUAGE]/Turkish?” (with answers ranging from 1: very well to 4: not at all). Speaking and writing Turkish did not form a proper scale and were thus included separately. This means that respondents who speak Turkish well cannot be assumed to also write it well, there is more variation in the sample in speaking and writing proficiency. The frequency of volunteering for a religious organization was accounted for via the question: “How often do you do volunteering work for religious organizations such as the mosque, religious communities (cemaat), etc?”. The frequency of praying was accounted for via the question: “How often do you attend services or go to a place of worship?” Both answering categories vary from 1: every day to 6: never. The frequency of praying was taken into account via the question: “Apart from religious services, how often do you pray (namaz)?” (with answers ranging from 1: every day to 7: never).

Country-fixed effects were included in the models to study the effect of the national context on identity formation, both dual and national. The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) provides scores for countries based on various policy indicators, such as anti-discrimination, political participation, access to nationality, and labour market mobility. In 2010, the MIPEX ranking of the 2000 Families project countries was, from lowest to highest: Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden. The higher the score, the more accommodative the country context was for the integration of immigrant-origin individuals and their different types of identities. Country effects needed to be analysed with caution, however, since not all countries were evenly represented in our sample. For example, Austria only had a sample of 37 individuals and Germany 267 individuals.

Some basic control variables such as age and citizenship – namely, Turkish, dual, national, or neither Turkish nor national – were included in the models. Another range of control variables was included in the models, but these did not significantly affect intergenerational transmission of a dual identity. They were therefore omitted from the analyses. Ethnicity (self-reported Turkish ethnicity, Kurdish ethnicity, or another reported ethnicity), being Muslim (without a denomination mentioned), and being specifically a Sunni Muslim did not affect the identity.

Results

The following results show how parents’ dual identities affect those of their adult children. shows the multinomial regression analyses of children's dual identity. The distinction was drawn between marginalized or separated (base outcome), assimilated, and integrated identities. Children of parents with an integrated identity were likelier than those whose parents had a marginalized or separated identity to have an integrated identity themselves (coefficient .73, sig. P < .01). Parents’ assimilated identity, more than a marginalized or separated identity, enhanced their children's assimilated identity (coefficient 1.25, sig P < .05). The same finding was observed for an integrated identity. Without considering the control variables, we therefore found support for hypothesis 1: the correlation between parents’ dual identities and their children's.

Table 2. Multinomial logistic regression: factors that influence dual identifications, base outcome is children's marginalized/separated identification.

includes the control variables to see whether the relationship between parents’ and their children's dual identities holds. We observed that some control variables significantly affected children's dual identities. Frequency of contact between parents and their children seemed to enhance their children's integrated identity, relative to a marginalized or a separated identity (coefficient .27, sig. P < .10). Having no citizenship, as opposed to only national citizenship, decreased the likelihood of an integrated identity. Better host-country language proficiency enhanced integrated (coefficient .37, sig. P < .01) and assimilated identities (coefficient .57, sig. P < .01). Turkish writing proficiency decreased the likelihood of an assimilated identity more than it did a marginalized or separated identity (coefficient −.42, sig. P < .10). Volunteering for religious organizations decreased the likelihood of an integrated (coefficient −.35, sig. P < .01) or assimilated identity (coefficient −.46, sig. P < .01) more than it did a marginalized or separated identity.

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression: factors that influence dual identifications, base outcome is children's marginalized/separated identification.

There were also differences between dual identity levels across countries. People living in the Netherlands (coefficient .80, sig. P < .05), Belgium (coefficient .70, sig. P < .05), and Sweden (coefficient 1.14, sig. P < .01) were likelier to have an integrated identity than a marginalized or separated identity and were likelier to have this than people living in Germany. Sweden and the Netherlands also scored highest on the MPIX overall integration policies in 2010. People living in Austria and Denmark, the countries scoring lowest, were less likely to have an integrated identity than a separated identity compared with people living in Germany. Although the latter two country effects were not significant, they provided further support that the country effects reflect their national integration policies. The non-significant results for Austria and Denmark could have been, for example, also caused by the lower number of respondents residing in these countries (37 in Austria, 48 in Denmark). These country effects imply that national integration policies can encourage the adaptation of an integrated identity as opposed to a marginalized or separated identity among immigrant-origin individuals. shows that the significant effect of having assimilated parents on the children's assimilated identity disappeared when the control variables were added. Adding the variables back one by one revealed that the parents’ assimilated identity lost its significant effect when adding the religious control variables: frequency of volunteering for a religious organization, visiting religious services, and praying. All these religious attributes also affected children's assimilated identity negatively, and one did so in a statistically significant way (volunteering). Children of identity assimilated parents are likelier to score low on these religious variables. The effect of parents’ assimilated identity also lost significance once country dummies were added. There could be something happening within the countries that affected the assimilated identity among both parents and their children.

Parents’ integrated identities still correlated positively and in a statistically significant way to their children's integrated identities (coefficient .60, sig. P < .05). This indicates that children of parents with integrated identities were likelier to have integrated identities themselves than the children of parents with a marginalized or separated identity. We thus found support for hypothesis 1: parents transmit their dual identity to their children.

Mothers and fathers

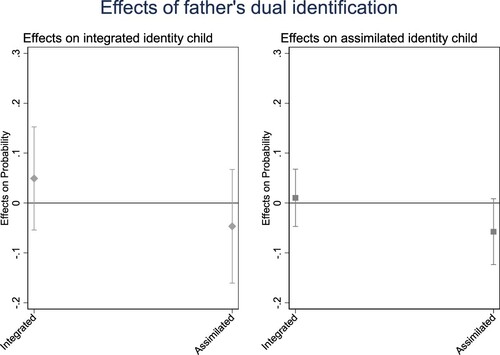

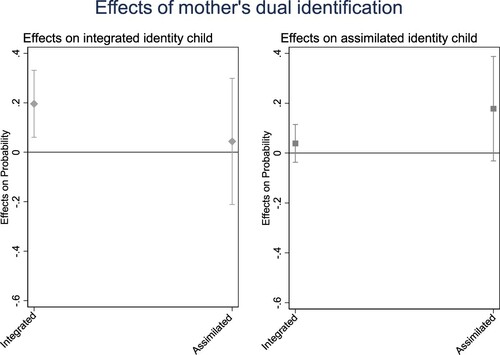

and and show the interaction effects between parents’ dual identities and their genders’ effects on their children's dual identities. The figures represent the marginal effects of parents’ integrated or assimilated identities compared with a marginalized or separated identity on their children's dual identities. shows that the fathers’ identities have no effects on the integrated or assimilated identities of their children. The results found in were driven by the mothers. also illustrates the positive effect of mothers’ integrated identities on their children's integrated identities. Mothers’ assimilated identity also had a positive effect on their children's assimilated identities (P < .05 one-tailed). The results provide support for hypothesis 2: mothers did indeed play a stronger role in the transmission of dual identities than fathers. Interestingly, we found this difference when it concerned only dual identity and not when it concerned only national identity (not illustrated in the tables or figures).

Figure 1. The marginal effects of father's dual identification on their child's dual identification (95 per cent confidence interval).

Figure 2. The marginal effects of mother's dual identification on their child's dual identification (95 per cent confidence interval).

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression: interaction effects of parents’ dual identifications with parents’ gender, base outcome is children's marginalized/separated identification.

Discussion and conclusion

This article examined the intergenerational transmission of dual identity in Turkish immigrant families in Europe. Consistent with other findings that parents who identify more with a specific group are likelier to engage in particular identity socialization practices when raising their children (e.g. Hughes Citation2003; Hughes et al. Citation2006; Casey and Dustmann Citation2010; Sabatier Citation2008; Verkuyten, Thijs, and Stevens Citation2012), our results show that immigrant parents’ dual identities correlate positively with their adult children's dual identities. Children of parents with an identity based on a sense of integration – as opposed to one on being marginalized or separate from the host country – are likelier to have an integrated identity themselves. The correlation is analogous for children of parents with an identity based on a sense of assimilation rather than marginalization or separateness. Our study showed that this effect was influential even in these children's adult lives and offers a contribution to the literature on the transmission of dual identities. Immigrant parents play a formative role in their child's development of dual identity. Dual identity, known to have all kinds of positive outcomes for the second generation, develops primarily in immigrant families in which a sense of national belonging is added to a pre-existing and sustained strong sense of belonging to the immigrant community (Benet-Martínez et al. Citation2002; Verkuyten and Martinovic Citation2012; Martiny et al. Citation2017; Wiley et al. Citation2019).

Also in line with earlier research (Warikoo Citation2005; Koh, Shao and Wang Citation2009; Casey and Dustmann Citation2010), we found that mothers had a stronger effect than fathers on identity transmission. In our study, this concerned their transmission of a dual integrated identity to adult children. We understood that immigrant fathers and mothers play distinct roles in family socialization by being responsible for different aspects of the parenting process, but also by emphasizing different values and related identities to their children. Studies have illustrated that women often serve as keepers of tradition and culture, especially in immigrant communities with collective family cultures (Orsi Citation1992; Warikoo Citation2005; Koh, Shao and Wang Citation2009). Our study suggests that by emphasizing dual identities among their children, mothers in certain contexts also served as bridges between values connected to the country of origin and values connected to the host country.

Our study contributes to the literature by examining the effect of the national context on the presence of certain types of identities among the adult children of immigrants. The results showed that levels of both national and dual identities are higher in countries with more multicultural policies than assimilation policies. In those national contexts, more opportunities exist to express different types of identities – whether ethnic, dual, or national. Verkuyten, Thijs, and Stevens (Citation2012) found that many immigrants most prefer dual identities because these let them be socially recognized, accepted, and valued by their immediate social network as well as the broader society in which they live. This is especially salient in contexts where such identity combinations are not considered signs of disloyalty to the host country. Illustrating the importance of creating environments in which immigrants and their children have the freedom to develop identities combined and simultaneously.

The results of our study expand knowledge about the role family and family origin play in transmission of different identities among immigrants. The family unit has long been recognized as core to the formation of attitudes among immigrant children and adolescents (Hughes et al. Citation2006; Casey and Dustmann Citation2010). Parents do not only influence their children's national identity formation, but children copy and further cultivate those identity levels throughout their lives. Dual identities are crucial to the integration process because they often correlate with higher levels of participation in domains of society, such as education, labour market, and politics. It is thus important to keep analysing how these types of identities among immigrants and their children develop and to emphasize that we can best understand these developments as intergenerational processes. Our study underscore the need to focus on processes within families, for instance, by tracking the impact that parents’ genders have over time on the transmission of particular identities.

Some limitations to our study stem from the data's cross-sectional nature. We could only make claims about correlations, not causations. Moreover, the data only offers a snapshot of the intergenerational transmission of national and dual identities. Whether this transmission will remain stable throughout the lives of Turkish immigrants and their children cannot be predicted. Additionally, a number of relevant circumstances that were unavailable in the data could affect the intergenerational transmission of identity, such as the coherence of parents’ messages about identity as well the emotional climate characterizing the family and parenting styles (Sabatier Citation2008; Sabatier and Berry Citation2008). The data also lacked information about other important sources of dual identity formation outside the family, such as neighbourhoods and contacts that the children of immigrants had with non-immigrants.

With identity now in the crosshairs of many public and political debates about immigration and integration, we find it imperative to study the origins, development, and combination of types of identities among immigrants and their children. Social and political contexts cannot be entirely untangled from these developments because belonging – which serves as a major source of social identity, self-esteem, and feelings of inclusion – is very much a relational process. Identity formation and development among immigrants and their children often comes in reaction to social and political surroundings. Future research would do well to put this relationship front and centre, examining how the development of dual identities can also be understood as a reaction to the environment. These findings could prove meaningful for immigrant families, non-immigrant families, and combinations thereof in Europe and beyond.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, dr. Mieke Maliepaard and dr. Anja van Heelsum for their comments on the manuscript and their suggestions to improve it. We also want to acknowledge the discussant, Eelco Harteveld, and other participants of the Political Psychology panel held at the “Politicologenetmaal” in Leiden (2017) for their suggestions. Lastly, we want to thank the research team of the 2000Families project for making their data available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alba, R. D. 1990. Ethnic Identity: The Transformation of White America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 1997. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 826–874.

- Baysu, G., and K. Phalet. 2019. “The up-and Downside of Dual Identity: Stereotype Threat and Minority Performance.” Journal of Social Issues 75 (2): 568–591.

- Benet-Martínez, V., J. Leu, F. Lee, and M. W. Morris. 2002. “Negotiating Biculturalism: Cultural Frame Switching in Biculturals with Oppositional Versus Compatible Cultural Identities.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33 (5): 492–516.

- Berry, J. W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46 (1): 5–34.

- Carol, S. 2016. “Like Will to Like? Partner Choice among Muslim Migrants and Natives in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 261–276.

- Carol, S., E. Ersanilli, and M. Wagner. 2014. “Spousal Choice among the Children of Turkish and Moroccan Immigrants in six European Countries: Transnational Spouse or Co-Ethnic Migrant?” International Migration Review 48 (2): 387–414.

- Carter, M. J. 2014. “Gender Socialization and Identity Theory.” Social Sciences 3 (2): 242–263.

- Casey, T., and C. Dustmann. 2010. “Immigrants’ Identity, Economic Outcomes and the Transmission of Identity Across Generations.” The Economic Journal 120 (542): F31–F51.

- Çelik, Ç. 2015. “‘Having a German Passport Will not Make Me German’: Reactive Ethnicity and Oppositional Identity among Disadvantaged Male Turkish Second-Generation Youth in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (9): 1646–1662.

- Crul, M., and J. Doomernik. 2003. “The Turkish and Moroccan Second Generation in the Netherlands: Divergent Trends Between and Polarization Within the Two Groups.” International Migration Review 37 (4): 1039–1064.

- Crul, M., and J. Schneider. 2010. “Comparative Integration Context Theory: Participation and Belonging in New Diverse European Cities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (7): 1249–1268.

- De Hoon, S., and F. Van Tubergen. 2014. “The Religiosity of Children of Immigrants and Natives in England, Germany, and the Netherlands: The Role of Parents and Peers in Class.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 194–206.

- De Vroome, T., M. Verkuyten, and B. Martinovic. 2014. “Host National Identification of Immigrants in the Netherlands.” International Migration Review 48 (1): 1–27.

- Else-Quest, N. M., and E. Morse. 2015. “Ethnic Variations in Parental Ethnic Socialization and Adolescent Ethnic Identity: A Longitudinal Study.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 21 (1): 54–64.

- Ersanilli, E., and R. Koopmans. 2011. “Do Immigrant Integration Policies Matter? A Three-country Comparison among Turkish Immigrants.” West European Politics 34 (2): 208–234.

- Esser, H. 2004. “Does the “New” Immigration Require a “New” Theory of Intergenerational Integration?” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1126–1159.

- Ganzeboom, H. B. G., and E. K. Sözeri. 2013. Data Documentation: ‘2000 Families: Migration Histories of Turks in Europe’. Amsterdam: VU University.

- González, R., and R. Brown. 2003. “Generalization of Positive Attitude as a Function of Subgroup and Superordinate Group Identifications in Intergroup Contact.” European Journal of Social Psychology 33 (2): 195–214.

- González, R., and R. Brown. 2006. “Dual Identities in Intergroup Contact: Group Status and Size Moderate the Generalization of Positive Attitude Change.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (6): 753–767.

- Groenewold, G., H. A. de Valk, and J. van Ginneken. 2014. “Acculturation Preferences of the Turkish Second Generation in 11 European Cities.” Urban Studies 51 (10): 2125–2142.

- Guveli, A. ND. [principal investigator]. 2000 Families: Migration Histories of Turks in Europe [data set]. University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester CO4 3SQ United Kingdom.

- Guveli, A., H. B. G. Ganzeboom, H. Baykara-Krumme, L. Platt, Ş Eroğlu, N. Spierings, S. Bayrakdar, B. Nauck, and E. K. Sozeri. 2016a. “2,000 Families: Identifying the Research Potential of an Origins-of-Migration Study.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (14): 2558–2576.

- Guveli, A., H. Ganzeboom, L. Platt, B. Nauck, H. Baykara-Krumme, S. Eroglu, S. Bayrakdar, E. K. Sozeri, and N. Spierings. 2016b. Intergenerational Consequences of Migration: Socio-Economic, Family and Cultural Patterns of Stability and Change in Turkey and Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2016. “Moving up or Falling Behind? Intergenerational Socioeconomic Transmission among Children of Immigrants in Norway.” European Sociological Review 32 (5): 675–689.

- Hughes, D. 2003. “Correlates of African American and Latino Parents’ Messages to Children About Ethnicity and Race: A Comparative Study of Racial Socialization.” American Journal of Community Psychology 31 (1-2): 15–33.

- Hughes, D., J. Rodriguez, E. P. Smith, D. J. Johnson, H. C. Stevenson, and P. Spicer. 2006. “Parents’ Ethnic-Racial Socialization Practices: a Review of Research and Directions for Future Study.” Developmental Psychology 42 (5): 747–770.

- Huijnk, W., and A. C. Liefbroer. 2012. “Family Influences on Intermarriage Attitudes: A Sibling Analysis in the Netherlands.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74 (1): 70–85.

- Kester, K., and S. K. Marshall. 2003. “Intergenerational Similitude of Ethnic Identification and Ethnic Identity: A Brief Report on Immigrant Chinese Mother-Adolescent Dyads in Canada.” Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 3 (4): 367–373.

- Klandermans, B., J. Van der Toorn, and J. Van Stekelenburg. 2008. “Embeddedness and Identity: How Immigrants Turn Grievances into Action.” American Sociological Review 73 (6): 992–1012.

- Koh, J. B. K., Y. Shao, and Q. Wang. 2009. “Father, Mother and me: Parental Value Orientations and Child Self-Identity in Asian American Immigrants.” Sex Roles, 60 (7-8): 600–610.

- Kranendonk, M., F. Vermeulen, and A. van Heelsum. 2018. “‘Unpacking’ the Identity-to-Politics Link: The Effects of Social Identification on Voting Among Muslim Immigrants in Western Europe.” Political Psychology 39 (1): 43–67.

- Kwak, K. 2003. “Adolescents and Their Parents: A Review of Intergenerational Family Relations for Immigrant and non-Immigrant Families.” Human Development 46 (2-3): 115–136.

- Love, A., and A. Levy. 2019. “Bridging Group Divides: A Theoretical Overview of the “What” and “How” of Gateway Groups.” Journal of Social Issues 75 (2): 414–435.

- Maliepaard, M., M. Lubbers, and M. Gijsberts. 2010. “Generational Differences in Ethnic and Religious Attachment and Their Interrelation. A Study among Muslim Minorities in the Netherlands.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (3): 451–472.

- Martiny, S. E., L. Froehlich, K. Deaux, and S. Y. Mok. 2017. “Defining Ethnic, National, and Dual Identities: Structure, Antecedents, and Consequences of Multiple Social Identities of Turkish-Origin High School Students in Germany.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 27 (5): 400–410.

- Nauck, B. 2001. “Intercultural Contact and Intergenerational Transmission in Immigrant Families.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 32 (2): 159–173.

- Nguyen, A. M. D., and V. Benet-Martínez. 2013. “Biculturalism and Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 44 (1): 122–159.

- Orsi, R. A. 1992. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Phalet, K., and U. Schönpflug. 2001. “Intergenerational Transmission of Collectivism and Achievement Values in Two Acculturation Contexts: The Case of Turkish Families in Germany and Turkish and Moroccan Families in the Netherlands.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 32 (2): 186–201.

- Phillimore, J. 2011. “Refugees, Acculturation Strategies, Stress and Integration.” Journal of Social Policy 40 (3): 575–593.

- Phinney, J. S. 1990. “Ethnic Identity in Adolescents and Adults: Review of Research.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 499–514.

- Phinney, J. S., G. Horenczyk, K. Liebkind, and P. Vedder. 2001. “Ethnic Identity, Immigration, and Well-Being: An Interactional Perspective.” Journal of Social Issues 57 (3): 493–510.

- Platt, L. 2014. “Is There Assimilation in Minority Groups’ National, Ethnic and Religious Identity?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 46–70.

- Sabatier, C. 2008. “Ethnic and National Identity among Second-Generation Immigrant Adolescents in France: The Role of Social Context and Family.” Journal of Adolescence 31 (2): 185–205.

- Sabatier, C., and J. W. Berry. 2008. “The Role of Family Acculturation, Parental Style, and Perceived Discrimination in the Adaptation of Second-Generation Immigrant Youth in France and Canada.” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 5 (2): 159–185.

- Schrover, M., and F. Vermeulen. 2005. “Immigrant Organisations.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (5): 823–832.

- Schulz, B., and L. Leszczensky. 2016. “Native Friends and Host Country Identification among Adolescent Immigrants in Germany: The Role of Ethnic Boundaries.” International Migration Review 50 (1): 163–196.

- Soehl, T. 2017. “Social Reproduction of Religiosity in the Immigrant Context: The Role of Family Transmission and Family Formation—Evidence from France.” International Migration Review 51 (4): 999–1030.

- Spierings, N. 2016. “Electoral Participation and Intergenerational Transmission among Turkish Migrants in Western Europe.” Acta Politica 51 (1): 13–35.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole.

- Van Heelsum, A., and M. Koomen. 2016. “Ascription and Identity. Differences Between First-and Second-Generation Moroccans in the way Ascription Influences Religious, National and Ethnic Group Identification.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 277–291.

- Verkuyten, M., and F. Fleischmann. 2017. “Ethnic Identity among Immigrant and Minority Youth.” In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents, edited by A. Rutland, D. Nesdale, and C. Spears Brown, 23–46. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Verkuyten, M., and B. Martinovic. 2012. “Immigrants’ National Identification: Meanings, Determinants, and Consequences.” Social Issues and Policy Review 6 (1): 82–112.

- Verkuyten, M., J. Thijs, and G. Stevens. 2012. “Multiple Identities and Religious Transmission: A Study among Moroccan-Dutch Muslim Adolescents and Their Parents.” Child Development 83 (5): 1577–1590.

- Warikoo, N. 2005. “Gender and Ethnic Identity among Second-generation Indo-Caribbeans.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (5): 803–831.

- Wiley, S., F. Fleischmann, K. Deaux, and M. Verkuyten. 2019. “Why Immigrants’ Multiple Identities Matter: Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice.” Journal of Social Issues 75 (2): 611–629.