ABSTRACT

This study examines how Otherness is constructed visually in newspaper photographs of the refugee crisis. This visual rhetoric analysis examines the form, content, and function of images and explores the rhetorical strategies deployed in visualizations of the refugee crisis in a mainstream Finnish national newspaper from 2015 to 2016. The data consisted of 1,473 images. The study identified six rhetorical strategies used for dehumanizing refugees: massifying, separating, passivating, demonizing, individualizing, and recontextualizing the Other. The rhetorical strategies in turn constructed four discourses related to refugees, namely those of threat and victimhood aimed at dehumanizing as well as personhood and distance aimed at humanizing the Other. The paper contributes to the current knowledge on dehumanization and humanization of refugees in public discourse by unpacking the subtle visual mechanisms through which these processes occur.

Introduction

The European refugee crisis gained worldwide attention in media coverage, leading to numerous studies focused on how social categories (Goodman, Sirriyeh, and McMahon Citation2017) and symbolic borders (Chouliaraki and Zaborowski Citation2017) are deployed in the news to distinguish “us” from “them” and between those who are deserving from those who are considered less deserving to enter (Lee and Nerghes Citation2018). Newspapers both inform and shape news audiences’ perceptions of the refugee crisis, and images included in news stories frame the subject matter in a particular way (Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017; Rochira et al. Citation2020). Hence neither news stories nor images are neutral or objective. Yet, the news is often regarded as objective, and newspaper photographs are understood as their visual proof; for this reason, their impact is considerable (Banks Citation2012). Images also provide influential means of communication in the context of the refugee crisis, since they hold power over audiences by shaping our understanding, emotions, attitudes, and actions regarding refugees. Indeed, there is ample research on visual/media representations of the refugee crisis, and many researchers have explored how visuals are used to position refugees/migrants in the realm of Otherness (e.g. Giubilaro Citation2018; Lenette Citation2019; Maneri Citation2021; Zaborowski and Georgiou Citation2019). Differing from the prior research, we adopt a social psychological approach to Otherness to examine how visual strategies of dehumanization used in news images construct Otherness in terms of the intergroup divide between us (Europeans) and them (refugees). With this novel approach, we seek to make a contribution to the existing literature on visuals in connection with refugee studies.

In social psychology, there has been growing interest in dehumanization, which is defined as “the act of perceiving or treating people as if they are less than fully human” and involves “denials of humanness” to both individuals and groups (Haslam and Stratemeyer Citation2016, 25). According to Haslam (Citation2006), there are two kinds of dehumanization: mechanistic dehumanization (in which human nature is denied to others, likening people to automata or machines) and animalistic dehumanization (which entails denying uniquely human attributes such as language, refined emotions, morality, and higher cognition to others, representing people as animal-like). Whereas mechanistic dehumanization views Others as passive objects deprived of agency, whose behaviour is reactive rather than initiated by personal will, animalistic dehumanization views Others as coarse, uncultured beings driven by instincts lacking moral sensibility (Haslam Citation2006). According to Haslam (Citation2006), dehumanization is not a rare or extreme phenomenon but rather a common aspect of intergroup dynamics in which people engage in many subtle, everyday ways.

Prior studies have shown how othering and dehumanizing discourses may influence intergroup relations negatively by constructing and strengthening the divide between the ingroup and the outgroup (Haslam and Stratemeyer Citation2016; Rochira et al. Citation2020). In addition, research has shown that dehumanization performed by the ingroup toward the outgroup may generate meta-dehumanization (awareness that one’s own group is perceived by another as less than fully human) and self-dehumanization (perceiving oneself as less human) among the dehumanized outgroup members, which further problematizes intergroup relations (Kteilly, Hodson, and Bruneau Citation2016; Yang et al. Citation2015). Hence, dehumanizing discourse may negatively influence not only the perception of the outgroup (refugees) among the ingroup (host nations) but also the outgroup members’ perception of themselves. For this reason, we argue that it is important to examine dehumanizing visual strategies from the lens of intergroup relations in the context of refugee studies.

Few previous studies have addressed the dehumanizing functions of visualizations of refugees. In their study of European news from five countries in 2015, Chouliaraki and Stolic (Citation2017) identified five symbolic strategies of the dehumanization of refugees, framing them in terms of biological life, empathy, a threat, hospitality, and/or self-reflexivity. By varying visual rhetorical strategies – massification, vilification, infantilization, marginalization, or aestheticization – the refugee is depicted as an ambivalent figure: a body-in-need, a helpless child, or a dangerous other. Previous studies have suggested that negative portrayals of refugees as criminals and rapists incite fear and invite a politics of securitization, deportations, or border closures (Banks Citation2012; Bleiker et al. Citation2013; Lenette and Miskovic Citation2018). Hence, dehumanizing visuals have the potential to reinforce what, for instance, Furedi (Citation2007) and Wodak (Citation2015) called “the politics of fear”, which influences both public perception of migrants/refugees and political responses to migration (Lenette and Miskovic Citation2018).

However, not all visual images of refugees intend to dehumanize the other. Some studies have suggested a more complex interplay between different visual media representations. For example, a study comparing the visual representation of the refugee crisis by CNN International and Der Spiegel showed how the former drew on human interest and lose/gain frames by using close-ups and tracking shots to emphasize humanity, while the latter outlet framed the refugee crisis in terms of law and control and xenophobia (Zhang and Hellmueller Citation2017). Also, Šarić’s (Citation2019) research on the Croatian public online broadcast showed that humanitarian issues dominated the visual representations of refugees, and while many of the photographs depicted groups of de-individualized faceless people, the refugees were rarely depicted as a threat. Instead, the majority of the group photographs conveyed an image of unfortunate, desperate people in transit.

Chouliaraki and Stolic (Citation2017) argued that humanitarian representations may be problematic because although they challenge the dehumanizing approach and can trigger empathy, they also tend to ignore the agency of refugees and fail to represent their experiences. Similarly, Yalouri (Citation2019) pointed out that using images of weakness and poverty in the name of humanism may sustain and reproduce this weakness instead of questioning the unequal distribution of the world’s suffering. These examples of humanitarian visual representations arouse an intriguing question: Can humanitarian visual representations that generate feelings of empathy also be understood as forms of visual dehumanization of refugees?

Based on the literature on dehumanization (e.g. Haslam Citation2006; Vaes, Paladino, and Haslam Citation2021), the answer to this question is yes. Even though dehumanization and negative evaluation are related, Vaes, Paladino, and Haslam (Citation2021) pointed out that dehumanization is not reducible to negative evaluation, derogation, and harm; it can also be examined in relation to positive variables such as helping and forgiveness. For them, the common denominator of different forms of dehumanization is the perception of people as “lesser humans” (Vaes, Paladino, and Haslam Citation2021, 31). One form of lessening people’s humanity is to depict and treat them as being deprived of agency (Haslam Citation2006), which is the case in images depicting refugees as vulnerable victims. Even though these images may generate positive feelings of empathy and even willingness to help among readers, the visual strategy itself may be perceived as dehumanizing.

As stated before, other studies have also used dehumanization as the frame for examining visuals in connection of refugees. For example, Chouliaraki and Stolic (Citation2017) turned refugees into objects of public responsibility and examined how news images “mobilize various forms of moral responsibility in public life – various practical dispositions of action towards the misfortunes of migrants and refugees” (1162). Hence, Chouliaraki and Stolic’s (Citation2017) notion of dehumanization seems to be based on Arendt’s (Citation1994) approach to dehumanization as a violation towards humanity that implies the obligation of a general responsibility. This approach to dehumanization – which Heinämaa and Jardine (Citation2021) anchored to phenomenological philosophy – can be understood as “a violation of the very subjectivity of the person, of their capacity to participate in the human world and singularly enrich the broader human community” (313). Our social psychological approach to dehumanization differs from this approach. Social psychological research has studied a variety of variables related to dehumanization, such as “helping, forgiveness, intergroup contact, moral, judgment, stereotyping and prejudicial attitudes” (Vaes, Paladino, and Haslam Citation2021, 28). In our study, we examine the linkage between dehumanization and intergroup relations between host nations and refugees. More specifically, we focus on the dehumanizing visual strategies that construct the understanding of refugees as separate and detached from the host nation (ingroup) and that position them in the realm of Otherness (outgroup). Denying others membership in a community is a central aspect of treating them as less than human (Bastien and Haslam Citation2010).

Prior to the current refugee crisis, the dehumanization approach was discussed in the context of racialized Othering as part of colonialism, in which the colonized nations were constructed as barbaric, savage, and culturally and racially inferior to the colonizer (typical of animalistic dehumanization; Haslam Citation2006). In contrast, Europeans/Westerners were constructed as civilized and culturally and racially superior to the countries they colonized; these constructions were used to justify the cultural and economic exploitation of the colonized (Boucher Citation2019) Compared to this overt dehumanizing exploitation, current media images deploy more subtle forms of dehumanization, which often might be difficult to notice. As Chouliaraki and Stolic (Citation2017) noted, the use of ethnocentric ethics in the current refugee crisis, which trap refugees between the positions of victim and evil-doer and turn the West into the object of protection, “reproduce historical tropes of colonial imagery in contemporary portrayals of mobile populations” (1164).

The aim of this study is twofold. First, we endeavor to explore the strategies of visual dehumanization and humanization in public discourse and, in so doing, contribute to the current knowledge on the forms of dehumanization in the field of racial and ethnic studies. We believe that our visual rhetorical approach allows us to unpack the subtle mechanisms through which these processes occur. Second, our focus on the contents, forms, and functions of visual rhetoric enables us to conduct a detailed analysis of rhetorical strategies deployed in the visualizations of refugees to elucidate ways in which processes between groups as well as boundaries between “us” and “them” are rendered salient to construct, maintain, and challenge the representations of refugees as well as intergroup relations.

Context of the study: Finland

In 2015, the number of asylum seekers and migrants crossing European borders exceeded 1 million (Eurostat Citation2016). According to Pettersson and Sakki (Citation2017, 316) “Finland received more than 30,000 asylum applications in 2015, which was 10 times greater than in previous years, resulting in a similar subsequent sharpening of asylum policies to such an extent that they were criticized for breaching both the Finnish constitution and international human rights law”. Some previous studies on the Finnish media suggested that the focus of discussion around the refugee crisis was more Europe centred, meaning that the refugee crisis was portrayed as a European crisis, while refugees themselves were primarily depicted as a threat (Sumuvuori et al. Citation2016; Vij Citation2016). This research also suggested that the news coverage shifted from European to national issues in late August 2015, when an increasing number of asylum seekers arrived in Finland, and the discourse on restricting their numbers intensified (Pantti Citation2016; Vij Citation2016). The same rhetorical shift was found in a longitudinal analysis of Finnish Prime Minister’s accounts of the refugee crisis over a 1-year period, which shifted from a discourse of pathos and ethos to a discourse of logos and homogenization, emphasizing rationality to justify tightened immigration policies (Sakki and Pettersson Citation2018). In order to cover the entire period of the refugee crisis in Finland, this study focuses on the 2-year period from January 2015 until December 2016.

Methods

A total of 1,473 photographs related to the “refugee crisis” published in the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2016 form the data of this study. The Helsingin Sanomat is the largest circulated newspaper in the Nordic countries (Media Audit Finland Citation2019). Because of its status, large circulation and, hence, the potential to influence the views of a nationwide readership, we regard it as important to scrutinize the way its visualizations frame the “refugee crisis”.

Our analysis relies on a visual rhetorical analysis of the content, structure and social, political and ideological functions of images (Danesi Citation2017; Martikainen Citation2019). A visual rhetorical analysis was operationalized using a content and social semiotic analysis. The content analysis explores the presented elements (Rose Citation2016), and the social semiotic analysis examines the suggested elements (i.e. denotative and connotative meanings) (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). First, we categorized the images based on their content paying careful attention to both the images and their captions. Thematic categories were identified and formed the starting point of the analysis. However, the main focus of the analysis was on the exploration of the rhetorical strategies the images in each thematic category deployed and the discursive functions they constructed related to refugees. The analysis of the visual rhetoric focused on elements both presented and suggested in the image (Danesi Citation2017; Foss Citation2005). As Martikainen (Citation2019, 895) referring to Foss (Citation2005) states, “while presented elements refer to the people, objects, and environments depicted in the image, as well as to the means of visual expression (composition, shape, colour, space, etc.), the suggested elements refer to the meanings constructed based on the visually presented elements”. Together, these two levels formed the visual rhetoric of the image framing the “refugee crisis” and refugees in particular ways.

The meaning of an image is not in the visual elements themselves but is constructed by the viewers in the interplay between visual elements and cultural meanings (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). Even though there are culturally preferred ways of interpreting visuals, different viewers interpret the same image in different ways due to their different motivations, goals, knowledge, and prior experiences (Danesi Citation2017; Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). Hence, the findings of this study should not be understood as “objective manifestations” but as contextual interpretations shaped by our professional roots in social psychology and visual culture studies. These roots orientated the analysis toward intergroup relations, in which we utilized our knowledge of the culturally preferred readings of the visual resources in the analysis. For this reason, we included ample image examples in this study and elaborated on the image analysis in detail to provide the readers with the means necessary to evaluate our findings.

Results

After preliminary bottom-up reading of 1,473 photographs, we noticed the recurrence of certain subject matters. We decided to classify the images according to these subject matters and, when necessary, included new subjects matters as the basis of classification. We ended up with 10 thematic categories, which in order of frequency were: groups of refugees in transit; statesmen, politicians, decision-makers and experts; receptions centres and refugee camps; warfare and destruction in the countries of origin; individual refugees and families; integration and interaction with locals; reactions of people in the host countries; depictions of everyday life in the countries of origin; and miscellaneous subject matters that did not form any coherent group. The nine aforementioned thematic categories included images of police officers, patrols, guardians, “faceless” refugees, and images of darkness. We regarded these images as the tenth thematic category with a specific rhetorical function.

The images selected in the analysis are representative of the images included in the thematic category. When analysing the images, we identified six visual rhetorical strategies for constructing the Otherness of refugees. We named the strategies as follows: massifying, separating, passivating, demonizing, individualizing and recontextualizing the Other. In the analysis, the choice of the concepts of “refugee”, “migrant” and “asylum seeker” followed the use of these concepts in the image caption and/or the news story.

summarizes the subject matter of the images, visual rhetorical strategies constructing Otherness, and functions of images (discourses) constructed through visual strategies.

Table 1. Subject matters, visual rhetorical strategies, and discourses of images related to “refugee crisis”.

Massifying the Other

The majority of images depicted groups of refugees in transit. depicts a scene at the border between Slovenia and Austria, where two police officers and two patrols are depicted calming down a crowd of refugees and preventing them from crossing the border. The policemen’s serious facial expressions and gestures command the refugees to back off. The policemen and the patrols are standing higher than the refugees, wearing their uniforms, emphasizing their superior position as representatives of law and order, giving them authority.

In the crowd of refugees is vast, and the long-shot strengthens the perception of its magnitude (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). It covers two-thirds of the vertical picture frame and the entire horizontal picture frame creating the impression of the crowd exceeding the boundaries of the image. In prior research, such magnitude of refugees has been referred to as a “flood”, “wave” or “current” (Drüeke, Klaus, and Moser Citation2021). The refugees are depicted with their backs towards the viewer, their faces are not clearly seen and, hence, no contact with the viewer is constructed (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006), which strengthens the dichotomy between “us” and “them”. The refugees are not depicted as individuals but as an anonymous, faceless herd.

The viewing angle of the image positions the spectator at the same level with the policemen, above the crowd of refugees. Hence, a connection between the spectator and policemen is introduced as if they together form the ingroup, from whose perspective the image is depicted. Based on the viewing angle, positioned above the level of the refugees, and embellished with the emblems of the state, law and order, this ingroup appears superior. The refugees are depicted lower, which makes them appear inferior (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). However, the mass of refugees compared to the few policemen make one suspect that should the refugees decide not to obey the policemen, they could not prevent them from crossing the border. This potential inability of the authorities to protect the European nations creates an air of threat which shakes the foundational sense of social security (see also Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Holzberg, Kolbe, and Zaborowski Citation2018; Šarić Citation2019).

A similar divide between “us” and “them” is constructed in representing a scene where – according to the caption – migrants attempt to break a chain formed by Greek police at the border between Greece and Macedonia. The migrants rush towards the policemen and the spectator is positioned behind the shoulders of the policemen. The close-up brings the forward surging crowd of migrants near the spectator, which creates a feeling of threat (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006).

The two images discussed above show how depictions of faceless masses of refugees confronted with the authorities construct a feeling of threat and danger. Even though the massification implicitly also refers to the victimhood of the refugees being forced to leave their homes (Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Šarić Citation2019), the visual expression of these images constructs the threat as the dominant sentiment. Studies conducted in other countries have also recognized the strong aspect of threat in media images representing crowds of refugees (De Cock, Sundin, and Mistiaen Citation2020; Šarić Citation2019). Simultaneously for refugees the images construct an identity of otherness fostering the intergroup divide between “us” (Europeans) and “them” (refugees).

Separating the Other

The role and protection of borders is often accentuated in the media coverage of the refugee crisis (Drüeke, Klaus, and Moser Citation2021). shows Hungarian police officers guarding the border between Hungary and Serbia. The border fence divides the image into two areas: refugees on the Serbian side (left) and policemen on the Hungarian side (right). Stretching almost through the entire picture space the barbered wire fence seems to manifest the importance of blocking the flight of refugees into central Europe. Barbed wire fences have ample negative historical connotations. For example, Berend (Citation2017, 2) states “since Auschwitz, the barbed wire fence is a powerful symbol, not of defence, but of oppression”. Smala (Citation2003), in turn, regards barbed wire as a symbol of war. Hence, the barbed wire fence can be seen as a fence of oppression not only equating the refugee crises with warfare but also making a divide between Europe/Europeans and rest of the world/Non-Europeans.

In border patrols with their German Shepherd dog guard the Finnish-Russian border in south-eastern Finland. The border is marked with Finnish and Russian landmarks and thin barbed wire. The patrols wear uniforms and carry weapons signalling the seriousness of the situation. Even though, no migrants are depicted in the image, the watchful appearance of the armed patrols and the alertness of the dog, suggest they might arrive at the border any time. The absence of refugees in the image dehumanizes the menace and makes it difficult to grasp.

The German Shepherd is known for its power and strength and is widely used in the military (Tenner Citation2017). According to Skabelund (Citation2008), German Shepherds became strongly identified with Nazi Germany as well as the rulers in the colonial world during the first half of the twentieth century. Afterwards, the breed became a “symbol of political racism” and a “pervasive symbol of imperial aggression and racist exploitation” enforcing social control (Skabelund Citation2008, 355, 357). Taken together the visual cues in the image emphasize order, control, and hegemony, where the Finnish nation prepares to face the threat. By not showing the refugees, the image makes the threat abstract and unpredictable – which heightens the feeling of insecurity.

also represents a scene at the border. It depicts cleaners disinfecting the area at the border between Croatia and Slovenia after the migrants have left. The image is taken from a low angle, which makes the EU sign appear more imposing. In addition, the composition emphasizes the EU sign, because it is located in the upper left golden section (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). Hence, even though the scene happens at the border between Croatia and Slovenia, the image seems to promote an understanding of migration as a European-level crisis (Goodman, Sirriyeh, and McMahon Citation2017). Refugees are not visible in the image. However, their presence is indirectly presented through the act of disinfection. The cleaners’ white protective clothing and masks together with the act of disinfecting may arouse associations of dirt and stigmatize refugees as spreading infectious diseases, which can be seen as a strategy of dehumanizing refugees and constructing a divide between dirty and sick refugees (the outgroup) and clean and healthy Europeans (the ingroup). This type of stigmatizing interpretation serves as a typical example of an animalistic form of dehumanization (Haslam Citation2006).

The images of the border depict fences blocking the flight of the refugees and patrols guarding the refugees or preparing for their arrival. The presence of massive barbed wire fences and armed patrols with German Shephard dogs contribute to the understanding of refugees as dangerous. The association of danger is further expressed through visual references to diseases spread by the refugees. The image of the refugees as threat (Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017) dominates the border imagery.

Passivating the Other

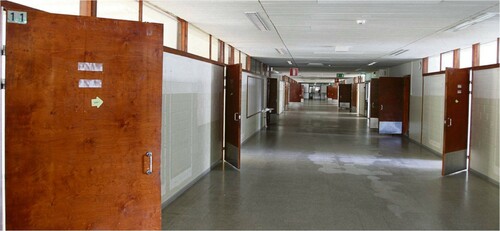

depicts the Hennala reception centre, which is an old military barrack converted into a reception centre. These types of red brick barracks were built everywhere in Finland and their function is widely known throughout the country. In addition, several Finnish prisons are made of red brick. In the perception of local people, the connotations of a prison or army barracks may, at least unconsciously, cast a shadow of suspicion and danger over the asylum seekers housed in these buildings. The reception centre seems to be isolated from the residential area of local people. The feeling of isolation is strengthened by the image of the desolate yard where a few asylum seekers loiter without making contact with the viewer.

and show the interiors of two Finnish reception centres. The building in was a military barrack and the building in used to be a hospital. The overall appearance of the interiors is highly institutional and sterile. The connection to the outside world is blocked. The interiors look tidy, but the lack of cosiness and any sort of stimuli make them appear dull and depressing. The dull lodgings appear to be “time killing centres” as the title of the story related to puts it. Such images, where asylum seekers are depicted doing nothing, have urged people to blame them for laziness and exploitation of the welfare system under the guise of asylum both in Finland and elsewhere (Banks Citation2012; Yap, Byrne, and Davidson Citation2011). In addition, images of refugees using smartphones () have been perceived as incongruent with ideas of poor refugees as passive sufferers who are deprived of their agency, raising doubts over asylum seekers’ true need for refuge (Yalouri Citation2019). This form of passivation appears as one strategy of dehumanizing refugees, which is congruent with Chouliaraki and Stolic’s (Citation2017) interpretation.

The photographs of refugee camps in different parts of Europe strongly deviate from the photographs of reception centres in Finland. Whereas the reception centres appear as austere places of order and depicted boredom is the main feeling, refugee camps appear to be places where chaos and the misery of people are shown. In these images, refugees are depicted as vulnerable victims (Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Šarić Citation2019). These aspects are visually expressed by depicting not only men, but also mothers with children, as well as humble materials and leftovers used to make shelters, the dirty and unorganized environment, as well as the casual composition of the image ( and ). In many cases, the camps are surrounded by fences triggering association with prisons. In , the high angle of the image makes the woman and children appear as oppressed, victims of circumstances (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006) evoking feelings of empathy. depicts a child cleaning the refugee camp. The child is located in the foreground, in the middle of the picture, surrounded by shabby shelters and garbage. Through this kind of visual arrangement, the image is linked to a host of media representations of the refugee crisis in which an image of a child is used to capture the misery and awaken people’s empathy (Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Bleiker et al. Citation2013; Šarić Citation2019). Simultaneously, this dehumanizes refugees in terms of infantilizing them and depicting them as powerless, deprived of their agency and voices (Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Giubilaro Citation2020).

In summary, whereas Finnish reception centres are depicted as solid environments providing the refugees with shelter and safety, refugee camps elsewhere in Europe are depicted as shabby, dirty, and chaotic areas where desperate people live in agony. However, in both cases the photographs depict refugees as powerless victims. This infantilized subject position strips them of their agency and voice representing them as objects of mercy.

Demonizing the Other

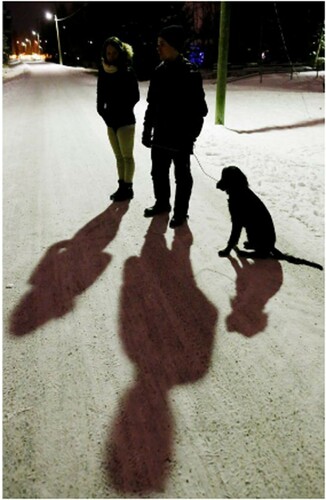

In addition to images of large crowds of refugees crossing the borders to Europe, an air of threat and danger is also constructed through a number of images related to refugees already received in Europe and Finland. These images either express the fears of local people or depict refugees in a manner which generates fear. was attached to the news related to a rape committed by a refugee in Kempele, Finland, which gained large visibility in the Finnish media (Pöyhtäri Citation2018). The image depicts two local people with a dog standing on an empty road surrounded by the winterly darkness. The dark and long, almost surreal, shadows of the people that occupy more than half of the height of the image seem to visualize the fear felt by the people.

portrays a group of asylum seekers at a reception centre in Turku, Finland. In the image, only their feet are depicted and their torsos, heads and faces are not shown. Judging by the shoes and trousers, they all are men. This means of depiction makes the male asylum seekers appear anonymous, and, therefore, threatening. Banks (Citation2012) has identified similar media images in the UK press, in which asylum seekers’ faces and/or bodies are obscured or hidden, which he regards as a visual strategy to refer to the “stigma” and “deviant nature” of asylum seekers. The caption of the image says the asylum seekers regret the rape committed by a single person and that this damages the image of the whole community of asylum seekers. However, the image itself constructs a counter narrative: depicting faceless male refugees it suggests any one of them might possibly be a rapist. These images support stereotypes of – especially male – refugees being criminals and rapists (Holzberg, Kolbe, and Zaborowski Citation2018) and the negative attitude several Finns have expressed towards reception centres in their neighbourhoods (Pöyhtäri Citation2018).

A total of 73 images depict policemen, soldiers, or patrols together with refugees. The presence of the police may contribute to the perception of refugees as dangerous criminals, and being an issue of security. In , refugees are not depicted in the image, but police cars are driving towards a reception centre surrounded by barricade tape. In addition, the darkness contributes to the atmosphere of danger (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006).

, in turn, depicts a demonstration against asylum seekers in Helsinki. The demonstrators seem to be ordinary Finnish people of different ages. Judging by their facial expressions and raised hands the demonstrators are captured by their collective ardour, which demonizes the invisible threat (refugees). The snap-shot increases the impression of authenticity. The demonstrators wave Finnish flags which are the only visual items that occupy the upper half of the image which emphasizes their message: the demonstrators are defending the Finnish nation from the refugees. The agenda and people’s conviction is strengthened by their movement to the right, which is the direction of determination (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006).

The afore discussed images either do not depict refugees at all or depict only their feet. According to Banks (Citation2012) and Drüeke, Klaus, and Moser (Citation2021) these kinds of representations reducing refugees to faceless, anonymous strangers de-individualize them – and thus reinforce the understanding of refugees as a threat to the safety of local people. In other words, by dehumanizing refugees the images make the threat more pervasive, casting a shadow of suspicion on refugees in general, and demonizing them collectively (Banks Citation2012).

Individualizing the Other

A total of 106 images in the Helsingin Sanomat between 2015 and 2016 show the life of refugees outside the reception centres, at school or work, for instance. Refugees’ employment has been a hot topic. On the one hand, people fear refugees taking their jobs and, on the other hand, blame them for being lazy and exploiting benefits without doing anything in return (Banks Citation2012; Rochira et al. Citation2020). Still, others see employment as important for refugees in terms of increasing their sense of agency (Yap, Byrne, and Davidson Citation2011). In , seven refugees are depicted shovelling snow from a flight of stairs. With their high-vis vests and vivid movements they appear energetic. However, from the point of visual expression, their integration into Finnish society seems forced. The high angle of the image makes the refugees appear inferior (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006) and the rails on both sides of the stairs emerge as barriers separating the refugees from the flow of everyday life. The high-vis vests worn by the refugees may be understood as othering visual devices, even though they are commonly used by diverse groups of people in Finland during the (darker) winter season. The image constructs an obedient group of refugees (them) who must adjust to the needs and will of Finland (us).

Some photos depict refugees with local people. One such occasion is depicted in , where an asylum seeker has completed a work-life period and proudly shows his diploma. He stands in the front, in the right hand golden section, which can be interpreted as emphasizing the achievement of the asylum seeker (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). Behind him, local people stand smiling with their arms around each other. It seems they are happy for the asylum seeker’s achievement. However, at the same time, the composition of the image seems highly arranged and the people are posing for the photographer/spectator as if presenting happiness instead of being happy. Even though the intention might have been to communicate togetherness, the fact that the asylum seeker is standing alone in the front and the local people stand in the background may construct another narrative: despite the achievement, the asylum seeker is not “one of us” but stands alone.

depicts a schoolteacher teaching a child. The body language and proximity emphasize the act of instruction and learning – the teacher’s care and the boy’s eagerness to learn. In addition to the composition, the close-up and viewing angle (eye level) contribute to a feeling of warmth and equality (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). The boy is not depicted as an asylum seeker but as a pupil. depicts a friendship between an asylum seeker family and a local family. Even though, the (local) woman and (asylum seeker) child are placed in the front of the image, their poses and gestures seem natural and casual in congruence with the caption stating the families have been friends for a longer time. is a close-up of two Syrian sisters, who according to the caption dream of work and life in Finland. The close-up, smiling faces and the sisters holding each other communicate trust and joy rarely found in the imagery. The triangle composition of the image, the round shapes of the sisters as well as their black and white garments create an air of harmony and peace in the image (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). The sisters make eye-contact with the viewer involving him/her in sharing their togetherness.

The above images focus on families and individual people framing them in the foreground of the image, which communicates intimacy and openness (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006). As Chouliaraki and Stolic (Citation2017, 1168) state, this kind of individuation “has the potential to offer a more humanised representation of refugees”. Lenette and Cleland (Citation2016) regard this as an attempt to rehumanize refugees and Chouliaraki and Stolic (Citation2017) understand it as a means of generating empathy in the viewers. Despite that the people photographed are aware of the presence of the photographer and pose for to him/her, these kinds of images communicate more authentic interaction between asylum seekers and local people and focus on them as individuals. By doing so, the images represent the people not as faceless asylum seekers nor as victims or a threat, but, instead, as pupils, friends, and family members with their own voice, backgrounds and aspirations for future – even though this may be mediated by the photojournalists. However, we found that refugees are rarely identified, individualized, and personified in newspaper imagery – or represented through identities other than their nationality (see also Chouliaraki and Zaborowski Citation2017).

Recontextualizing the Other

During 2015–16, the Helsingin Sanomat regularly published images of refugees’ countries of origin – mainly Iraq and Syria (see ). Initially, the images depicted warfare, and the chaotic and dangerous circumstances in those countries. It seems the images might have served the purposes of preparing the Finnish people to receive refugees. However, the number of images depicting those countries increased notably in autumn 2016, and the images began to show also scenes from people’s everyday lives. In addition, the images witness a clear shift of focus from matters related to refugees in Finland to European or Middle-Eastern countries. In their study on Finnish Prime Minister’s accounts of the refugee crisis, Sakki and Pettersson (Citation2018) recognized a similar shift of focus.

shows a scene of warfare creating an understanding of the hardships for people in Syria. However, simultaneously (autumn 2016), the Helsingin Sanomat published images showing Syrian people leading a life where no hints of war are visible. For instance, portrays a baptismal celebration in Damascus. Nothing in the image seems to refer to the “refugee crisis” or warfare (except for the absence of young and adult men). However, the caption states that behind the wall there was a renovation taking place due to damage caused by a grenade. The beautiful environment, festive clothes, smiling faces and laid tables conceal the demolition next door.

shows children attending a music camp forming a line before the music lesson under the guidance of their teacher. The image seems to convey a reassuring message that it is safe for children to live in Syria; the depiction of children in a school-like setting strongly connotes with hope for the future.

In summary, the images depicting the lives of Syrian people in Syria may be understood to serve two purposes. First, even though the people depicted in the images are not refugees themselves but Syrian citizens living in their country, these images recontextualize refugees, creating an understanding that also those people who sought refuge in Europe during the refugee crisis were once people with agency who had homes, families, social networks, celebrations – just like us. Second, the imagery seems to construct an understanding that it is possible – and even safe – to live in Syria. This interpretation is confirmed by the heading of a photo journalistic section stating that “Syria is ready to take everybody back” (Helsingin Sanomat, 24.10.2016). The latter images showing normal life in Syria together with images depicting the refugee crisis elsewhere than in Finland may serve purposes of releasing us (the ingroup) from our moral responsibility and guilt for not accepting more refugees in Finland.

Discussion

In the present paper, we examined the visual rhetoric as a means of constructing discourses related to the refugee crisis, paying special attention to visual strategies constructing Otherness. We found six visual rhetorical strategies reinforcing the Otherness of the refugees: massifying, separating, passivating, demonizing, individualizing and recontextualizing the Other. We showed how these visual strategies constructed diverse discourses about refugees. In the following, we cluster the depictions identified in the analysis into four main discourses: threat, victimhood, personhood, and distant refugees. Whereas discourses of threat and victimhood relate to dehumanization, discourses of personhood and distant refugees relate to humanization.

The discourse of threat

As our study shows, the studied photographs mostly depicted refugees as a threat. We found the discourse of threat was constructed through visual rhetorical strategies of massifying, separating and demonizing of the Other, which are all typical means of dehumanizing people (Haslam Citation2006). In the visual expression, the threat was constructed: by depicting masses of refugees gathering at the European borders; by including border patrols, soldiers and police in the photographs; by depicting local people’s fear and anger; by depicting refugees who do not make eye-contact; by using long-shots to depict masses of refugees in transit; by using snap-shots to express restlessness and the magnitude of refugees; by depicting (mainly male) refugees whose faces were hidden; by including elements related to the military, warfare and oppression (barbed wire, German Shepherd dogs); and by depicting visual elements like protective clothing and masks suggesting that refugees spread diseases. Even though the “refugee journey” is in most cases a traumatic and stressful experience (Mazzetti Citation2008), the images in the Helsingin Sanomat rarely referred to that dimension. As is typical for strategies of dehumanization (Haslam Citation2006), the rhetoric of threat de-individuates refugees and portrays them as an indistinguishable crowd. The aforementioned strategies can primarily be associated with animalistic dehumanization because they construct an understanding of refugees as dangerous, hostile, coarse, and driven by instincts rather than civility, refinement, or intelligence (Haslam Citation2006). Together, these means of visual expression demonize refugees and construct an image of them as a menace against which Europe must be protected. Hence, the discourse of threat is closely connected to the discourse of (national) security (Bleiker et al. Citation2013; Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Šarić Citation2019), as well as to the discourse of fear, from the point of view of news audiences’ perceptions and responses (Banks Citation2012).

The discourse of victimhood

A number of international studies on media representations of the refugee crisis have shown how refugees are portrayed as victims (Drüeke, Klaus, and Moser Citation2021; Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Šarić Citation2019). We also identified the discourse of victimhood. The discourse of victimhood was mainly constructed through the visual rhetorical strategy of passivating or infantilizing the Other in terms of presenting refugees deprived of agency – both typical aspects of mechanistic and animalistic dehumanization (Haslam Citation2006). This visual rhetorical strategy was mostly employed in images depicting refugees in reception centres and refugee camps. In these images, victimhood was visually communicated through depictions of bored or desperate looking refugees either “killing time” in reception centres or lacking the ability to influence the poor conditions in refugee camps. Other means of visual rhetoric communicating victimhood included sterile, institutionalized interiors and thick, closed walls of reception centres; shabby and dirty environments in refugee camps; and high-angle shots making refugees appear inferior. Congruent with prior studies (Bleiker et al. Citation2013; Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017; Šarić Citation2019), we found the aspect of victimhood was strengthened by depicting the vulnerability of women and children. Even though the discourse of victimhood may be perceived more positively than the discourse of threat, the victimized are nevertheless treated as deviant in the sphere of Otherness because their deprived agency marginalizes them in relation to those who have agency and self-determination (Vaes, Paladino, and Haslam Citation2021).

The discourse of personhood

A minority of the images published in the Helsingin Sanomat present refugees as individuals with unique life stories of their own, past and present experiences, and future aspirations. This finding is congruent with Chouliaraki and Zaborowski’s (Citation2017) notion that refugees are mainly represented through their nationality as a homogenic crowd and seldom in terms of other potential identities. That being said, the Helsingin Sanomat published some stories with accompanying photographs about the lives and experiences of individuals and families, interacting with local people and participating in social activities (e.g. school and working life). At the level of visual expression, the discourse of personhood was constructed by depicting a single refugee or a few refugees who made eye-contact with the spectator; by showing a variety of facial expressions; by depicting refugees wearing indoor clothes; by taking close-ups and medium shots that frame the person in the image closer to the viewer; by adopting an eye-level angle that presents the person in the image and the viewer as equals. Compared to images communicating a threat or victimhood that dehumanize refugees, these images humanize refugees constructing an understanding of them as people having and occupying different identities as pupils, family members, and friends. Hence, from the news audiences’ point of view, the discourse of personhood is connected with the discourse of hospitality (Chouliaraki and Stolic Citation2017).

The discourse of the distant refugee

The fourth discourse we identified was the discourse of the distant refugee (cf. Sakki and Pettersson Citation2018) communicated through images depicting people’s lives mainly in Syria. This discourse was mainly constructed through the visual rhetorical strategy that we named recontextualizing the Other. Differing from the majority of photographs that dislocate refugees from their socio-cultural, political, and historical contexts, the images forming this discourse strived for a more contextual portrayal of refugees. By depicting the fellow patriots of Syrian refugees, the images “contextualize” refugees and present them as social, political, and historical subjects. Visually the discourse of the distant refugee was constructed by depicting warfare and people continuing their lives in demolished homes; by showing people taking part in normal social activities or celebrating in festive garments with smiles on their faces; by using snap-shots to communicate the casualness and ordinariness of people’s lives. On the one hand, such images may generate empathetic understanding and compassion toward refugees. However, on the other hand, by suggesting that “life goes on in Syria”, such images may bring relief to our (ingroup) moral guilt of not doing more to help refugees in their distress and agony (Haslam Citation2006). Thus, the discourse of the distant refugee is connected with the discourse of responsibility and guilt (Drüeke, Klaus, and Moser Citation2021; Haslam Citation2006).

Conclusions

This article has explored the ways in which visual strategies of (de)humanization were used in news images to construct intergroup relations. The aforementioned discourses construct and maintain the divide between the ingroup (us, Europeans, Finnish people) and outgroup (refugees). The discourse of threat dehumanizes refugees positioning them as dangerous criminals threatening the wellbeing of the ingroup. The discourse of victimhood enables a positive ingroup identity in terms of feeling empathy and helping refugees but, simultaneously, dehumanizes refugees depriving them of voice and agency. The humanizing discourse of personhood makes a positive ingroup identity possible by narrowing the distance between the groups. Despite the overt intergroup reconciliation, the discourse of personhood often fails to achieve this goal and, instead, maintains the intergroup divide and the outgroup otherness in more indirect ways. Finally, the discourse of the distant refugee makes it possible to portray refugees as equals to the ingroup, but simultaneously this discourse makes it possible for ingroup members to shed their moral guilt felt due to the agony of the outgroup. While the two first discourses are strongly associated with dehumanization in terms of denying people qualities of their humanness, the two latter discourses are based on empathy in terms of recognizing the humanness of people. However, under the guise of empathy, they serve the interests of the ingroup in terms of tempering their moral guilt (Haslam Citation2006; Hodson, MacInnis, and Costello Citation2014).

As this study shows, newspaper photographs and discourses communicated through them depict and construct boundaries that separate refugees from the native population. State borders, barbed wire fences, chains of policemen, and walls of reception centres physically separate the refugees from local populace. Simultaneously, these mediated images of barriers construct imagined and symbolic boundaries separating refugees from local people and positioning them in the realm of otherness (Drüeke, Klaus, and Moser Citation2021). These images construct an intergroup divide between refugees (outgroup) and the citizens of the host countries (ingroup), portraying refugees from the perspective of the ingroup and serving its interests. Our visual rhetorical analysis allows us to further expose the subtle mechanisms underlying dehumanization. As our analysis suggests, visual dehumanization is reinforced in different ways: visual symbols of dirtiness (e.g. protective clothing and masks) or warfare and oppression (e.g. German Shepherd dogs and barbed wire), depictions of faceless figures (e.g. only feet or shoes), and colours (e.g. darkness and black), or high angle shots that make the refugees appear inferior. Intriguingly, as our visual analysis suggests, the visual presence of the refugee is not needed for the dehumanization to occur.

As prior research has demonstrated, dehumanizing visual rhetoric and discourses not only influence newspaper audiences’ perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and attitudes to refugees but may also support xenophobic behaviour toward them (Banks Citation2012; Haslam and Stratemeyer Citation2016; Rochira et al. Citation2020). Dehumanizing visual images in national news media may be understood as dehumanization performed by host nations (ingroup) toward refugees (outgroup). This can generate meta-dehumanization, wherein the outgroup members become aware of the fact that they are perceived as inferior (Kteilly, Hodson, and Bruneau Citation2016). This, in turn, can lead to self-dehumanization, wherein the outgroup members perceive themselves as lesser humans (Yang et al. Citation2015). For this reason, dehumanizing visuals and visual discourses may significantly problematize refugees’ lives in their host countries and hinder – or even prevent – their integration in society (Banks Citation2012; Haslam and Stratemeyer Citation2016). Therefore, it is important to promote critical awareness of the constructed nature of news photographs as well as the rhetorical strategies harnessed to communicate politically and ideologically laden messages that dehumanize refugees and maintain their Otherness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arendt, H. 1994. Essays in Understanding 1930-1954. Edited by J. Kohn. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Banks, J. 2012. “Unmasking Deviance: The Visual Construction of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in English National Newspapers.” Critical Criminology 20 (3): 293–310.

- Bastien, B., and N. Haslam. 2010. “Excluded from Humanity: The Dehumanizing Effects of Social Ostracism.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (1): 107–113.

- Berend, N. 2017. “Hungary, the Barbed Wire Fence of Europe.” E-International Relations, Jun 12, 1–2. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.e-ir.info/2017/06/12/hungary-the-barbed-wire-fence-of-europe/.

- Bleiker, R., D. Campbell, E. Hutchison, and X. Nicholson. 2013. “The Visual Dehumanization of Refugees.” Australian Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 398–416.

- Boucher, D. 2019. “Reclaiming History: Dehumanizing and the Failure of Decolonization.” International Journal of Social Economics 46 (119): 1250–1263.

- Chouliaraki, L., and T. Stolic. 2017. “Rethinking Media Responsibility in the Refugee ‘Crises’: A Visual Typology of European News.” Media, Culture & Society 39 (8): 1162–1177.

- Chouliaraki, L., and R. Zaborowski. 2017. “Voice and Community in the 2015 Refugee Crisis. A Content Analysis of News Coverage in Eight European Countries.” International Communication Gazette 79 (6–7): 613–635.

- Danesi, M. 2017. Visual Rhetoric and Semiotic. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- De Cock, R., E. Sundin, and V. Mistiaen. 2020. “The Refugee Situation as Portrayed in News Media: A Content Analysis of Belgian and Swedish Newspapers 2015–2017.” In Media Representations, Public Opinion, and Refugees’ Experiences, edited by L. d’Haenens, W. Joris, and F. Heinderyckx, 39–55. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Drüeke, R., E. Klaus, and A. Moser. 2021. “Spaces of Identity in the Context of Media Images and Artistic Representations of Refugees and Migration in Austria.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 24 (1): 160–183.

- Eurostat. 2016. Accessed October 3, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/conferences/conf-2016.

- Foss, S. K. 2005. “Theory of Visual Rhetoric.” In Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods, and Media, edited by K. Smith, S. Moriarty, G. Barbatsis, and K. Kenney, 141–152. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Furedi, F. 2007. Politics of Fear. Beyond Left and Right. London: Continuum.

- Giubilaro, C. 2018. “Un)Framing Lampedusa: Regimes of Visibility and the Politics of Affect in Italian Media Representations.” In Border Lampedusa. Subjectivity, Visibility and Memory Stories of sea and Land, edited by G. Proglio, and L. Odasso, 103–117. London: Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Giubilaro, C. 2020. “Regarding the Shipwreck of Others: For a Critical Visual Topography of Mediterranean Migration.” Cultural Geographies 27 (3): 351–366.

- Goodman, S., A. Sirriyeh, and S. McMahon. 2017. “The Evolving (Re)Categorisations of Refugees Throughout the ‘Refugee/Migrant Crisis’.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 27 (2): 105–114.

- Greussing, E., and H. G. Boomgaarden. 2017. “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24 (11): 1749–1774.

- Haslam, N. 2006. “Dehumanization: An Integrative Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10 (3): 252–264.

- Haslam, N., and M. Stratemeyer. 2016. “Recent Research on Dehumanization.” Current Opinion in Psychology 11: 25–29.

- Heinämaa, S., and J. Jardine. 2021. “Objectification, Inferiorization, and Projection in Phenomenological Research on Dehumanization.” In Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, edited by M. Kronfeldner, 309–325. New York: Routledge.

- Hodson, C., C. C. MacInnis, and K. Costello. 2014. “(Over)Valuing ‘Humanness’ as an Aggravator of Intergroup Prejudices and Discrimination.” In Humanness and Dehumanization, edited by P. G. Bain, J. Vaes, and J.-P. Leyens, 86–110. New York: Routledge.

- Holzberg, B., K. Kolbe, and R. Zaborowski. 2018. “Figures of Crisis: The Delineation of (Un)Deserving Refugees in the German Media.” Sociology 52 (3): 534–550.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images – The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Kteilly, N., G. Hodson, and E. Bruneau. 2016. “They See Us as Less than Human: Metadehumanization Predicts Intergroup Conflict via Reciprocal Dehumanization.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 110 (3): 343–370.

- Lee, J.-S., and A. Nerghes. 2018. “Refugee or Migrant Crisis? Labels, Perceived Agency, and Sentiment of Polarity in Online Discussions.” Social Media + Society 4 (3): 1–22.

- Lenette, C. 2019. “Visual Depictions of Refugee Camps: Constructing Notions of Refugee-Ness.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, edited by P. Liamputtong, 1811–1828. Singapore: Springer.

- Lenette, C., and S. Cleland. 2016. “Changing Faces: Visual Representations of Asylum Seekers in Times of Crisis.” Creative Approaches to Research 9 (1): 68–83.

- Lenette, C., and N. Miskovic. 2018. “‘Some Viewers may Find the Following Images Disturbing’: Visual Representations of Refugee Deaths at Border Crossing.” Crime Media Culture: An International Journal 14 (1): 111–120.

- Maneri, M. 2021. “Breaking the Race Taboo in a Besieged Europe: How Photographs of the “Refugee Crisis” Reproduce Racialized Hierarchy.” Ethnic & Racial Studies 44 (1): 4–20.

- Martikainen, J. 2019. “Social Representations of Teachership Based on Cover Images of Finnish Teacher Magazine: A Visual Rhetoric Approach.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 7 (2): 890–912.

- Mazzetti, M. 2008. “Trauma and Migration: A Transactional Analytic Approach Toward Refugees and Torture Victims.” Transactional Analysis Journal 38 (4): 285–302.

- Media Audit Finland. 2019. LT ja JT tarkastustilasto 2019 (Statistics of Distribution 2019). Accessed October 3, 2020. https://mediaauditfinland.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/LT-tilasto-2019.pdf.

- Pantti, M. 2016. “Despicable, Disgusting, Repulsive!!!! Public Emotions and Moralities in Online Discussion About Violence Towards Refugees.” Javnost – The Public 23 (4): 363–381.

- Pettersson, K., and I. Sakki. 2017. “Pray for the Fatherland! Discursive and Digital Strategies at Play in Nationalist Political Blogging.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 14 (3): 315–349.

- Pöyhtäri, R. 2018. “Raiskausuutisista vihapuheeseen: Uutismedian eettistä harkintaa.” In Pakolaisuus, tunteet ja media, edited by M. Maasilta, and K. Nikunen, 92–126. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Rochira, A., E. Avdi, I. Kadianaki, A. Pop, R. Redd, G. Sammut, and A. Suerdem. 2020. “Immigration.” In Media and Social Representations of Otherness. Psycho-Social-Cultural Implications, edited by T. Mannarini, G. A. Veltri, and S. Salvatore, 39–59. Cham: Springer.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies. An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Sakki, I., and K. Pettersson. 2018. “Managing Stake and Accountability in Prime Ministers’ Accounts of the “Refugee Crisis": A Longitudinal Analysis.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 28 (6): 406–429.

- Šarić, L. 2019. “Visual Presentation of Refugees During the ‘Refugee Crisis’ of 2015–2016 on the Online Portal of the Croatian Public Broadcaster.” International Journal of Communication 13: 991–1015.

- Skabelund, A. 2008. “Breeding Racism: The Imperial Battlefield of the ‘German’ Shepherd dog.” Society & Animals 16 (4): 354–371.

- Smala, S. 2003. “Globalised Symbols of war and Peace.” Social Alternatives 22 (2): 37–42.

- Sumuvuori, J., A. Vähäsöyrinki, T. Eerolainen, J. Lindvall, R. Pasternak, M. Syrjälä, and A. Talvela. 2016. Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Press Coverage. London: The Finnish Institute in London, The Finnish Cultural Institute for the Benelux. Accessed October 3, 2020. http://finnishinstitute.cdn.coucouapp.com/media/.

- Tenner, E. 2017. “Constructing the German Shepherd dog.” Raritan: A Quarterly Review 35 (3): 90–115.

- Vaes, J., M. P. Paladino, and N. Haslam. 2021. “Seven Clarifications on the Psychology of Dehumanization.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 16 (1): 28–32.

- Vij, S. 2016. “Kutsumattomia vieraita. Turvapaikanhakijoita ja pakolaisia koskevan keskustelun kehystäminen Helsingin Sanomissa kesällä 2015.” Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki, Finland.

- Wodak, R. 2015. The Politics of Fear. What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Yalouri, E. 2019. “‘Difficult’ Representations. Visual art Engaging with the Refugee Crisis.” Visual Studies 34 (3): 223–238.

- Yang, W., S. Jin, S. He, Q. Fan, and J. Zhu. 2015. “The Impact of Power on Humanity: Self-Dehumanization in Powerless.” PLoS ONE 10 (5): 1–19.

- Yap, S. Y., A. Byrne, and S. Davidson. 2011. “From Refugee to Good Citizen: A Discourse Analysis of Volunteering.” Journal of Refugee Studies 24 (1): 157–170.

- Zaborowski, R., and M. Georgiou. 2019. “Gamers Versus Zombies? Visual Mediation of the Citizen/Non-Citizen Encounter in Europe’s ‘Refugee Crisis’.” Popular Communication 17 (2): 92–108.

- Zhang, X., and L. Hellmueller. 2017. “Visual Framing of the European Refugee Crises in Der Spiegel and CNN International: Global Journalism in News Photographs.” The International Communication Gazette 79 (5): 483–510.