ABSTRACT

Conviviality has developed as a framework for interpreting everyday social life in diverse urban contexts, but the entanglement of power with convivial social interactions remains underexplored. Based on ethnographic fieldwork in the urban margins of Jaffa, contemporary Israel, this article engages this dearth through an analysis of the relationship between the materiality of the built environment and everyday social interaction, building on an existing literature that makes this connection. Following the mass exodus of Palestinians from Jaffa in 1948 and decades of housing construction and state-generated migration to Jaffa by the Israeli state, the city’s dense urban periphery illustrates the concurrence of uneven material and legal infrastructures, deceptive discourses, and everyday sociability between inhabitants. Thus, the article suggests a reengagement with a conceptualization of conviviality made decades earlier. Applied to Jaffa, Mbembe’s argument indicates ways in which conviviality can be a register of power.

Introduction

The focal point of Jaffa’s most southern neighbourhood is Mahrozet Street. The street begins with a ten-story block on one side, and on the other, the beginning of rows of shikunim (modernist social housing) constructed in the 1960s. About one-hundred metres in, there is a roundabout, which marks the most significant interruption in an otherwise ordinary landscape of shikunim (singular shikun). On the south side of Mahrozet, the shikunim continue; two taller tower blocks built in the 1980s mark the end of the street. The rest of the north side of Mahrozet, however, is a Palestinian Arab bayāra (orchard) of the extended family Abu Seif. Remnants of pre-1948 citrus farming complexes which sprawled around the edges of the historic city, it is now an informal urban landscape featuring older and newer constructions, ranging from sandstone brick houses to shacks with steel roofs. When inside Bayārat Abu Seif at its edges, wooden, leafy shacks housing goats and chickens are jarred by the squareness of the shikunim that take up most of the sky above. They are not tall buildings, but their presence is flattening. The bayāra stretches across significant parts of the neighbourhood, and the material juxtaposition between these built forms is striking.

Yet on the street, a row of shops faces the bayāra. There is: a fast-food place selling pizza and Yemeni-Jewish pastries; a convenience store owned by Romanian Jews; a bits and bobs store owned by a Jewish Moroccan-Bulgarian couple; and a storage space owned by the Abu Seif family. One cannot visit the street without seeing a few men from the family sat on the street with small plastic cups of Arabic coffee, often pouring them out for Jewish shop owners. For some in the neighbourhood, a rich sociability has emerged through co-residence in this neighbourhood over decades.

In much of contemporary conviviality studies, accounts of this kind of social conviviality are read through forms of relationality between persons rather than between persons and the spatial regime they engage with each other in. Even distinctions between forms of social togetherness that explicitly refer to the importance of “structural context” (Neal, Bennett, and Cochrane Citation2013, 318, referencing Wise Citation2009, 42), or the typologies of built space (see, for example, Cook, Dwyer, and Waite Citation2011; Wessendorf Citation2014; Piekut and Valentine Citation2017; Heil Citation2014; Tyler Citation2020) can be reductive when it comes to articulating the ways in which urban space and the materiality of the built environment inform interactions. Conviviality practices remain linguistically defined, rather than relata in a spatially constructed political geography of the city. To offer an example, Tilman Heil refers to “the negotiation of practices in spaces shared with neighbours” (Heil Citation2014, 460). Here, space is seen as somewhat neutral; as the stage of interaction, rather than a mediator of infrastructural networks through which power may be enacted. Whilst there are cases where space does appear to have a more active role (Jones et al. Citation2015; Power and Bartlett Citation2015), the complex ways in which the materiality of buildings, housing projects, public spaces, and urban regeneration projects produce (and prevent) certain forms of convivial interaction has not been a central focus within the conviviality literature.

As Rishbeth and Rogaly (Citation2017, 286) argue, “Conviviality … needs to be understood with regard to the physical design of urban public space – materiality and form, social functions and atmosphere [that] … shape qualities of both sociability and solitude.” Conviviality is situational, as well as relational, reflecting different spatial scales, materialites and timeframes (Vodicka and Rishbeth Citation2022, 4). Building on the work of urban geographers (Amin Citation2012; Prytherch Citation2021) and urban designers (Rishbeth and Rogaly Citation2017; Vodicka and Rishbeth Citation2022), this article argues that urban form itself is pertinent to the study of urban sociability. It goes further in pointing to the ways in which the meaning of conviviality changes when spatio-materially constructed state infrastructures are understood as entangled with everyday spheres of social engagement. By re-engaging Mbembe’s argument about conviviality becoming a form of power itself (Mbembe Citation1992), and by looking at the perspective of a peripheral neighbourhood of Jaffa in which diverse communities engage in the shadow of ethno-nationalist spacemaking, this article builds on existing critical conceptualizations of conviviality (Back and Sinha Citation2016; Valluvan Citation2016; De Noronha Citation2022) to suggest further ways in which conviviality may be rethought.

An older literature in urban anthropology drew attention to the ways in which fortified enclaves limit the possibility of public encounters between residents and non-residents, thus rigidly constructing material and social boundaries that are represented spatially (Caldeira Citation1999; Low Citation2001). I seek to demonstrate how everyday urban sociality within spatial boundaries is informed by histories of placemaking and spacemaking that complicate such interactions. The aim is to reveal how discourses of conviviality are framed within a politics of materiality. Although it has been recognized that “spaces and times of convivial relations rest as much on material environs as they do on interpersonal and social relations” (Wise and Noble Citation2016, 427), this has been neglected in much conviviality studies. It is often hinted at, but its analytical role is rarely unpacked. As Vodicka and Rishbeth (Citation2022, 3) argue, “‘within the literature on conviviality there … [is] a lack of meaningful analysis of how the significance of convivial acts is both embedded and informed by the actual context in which they are enacted”. Following this claim, my argument has implications for all urban spaces. This may include understanding sociability through its relation to the spatial structure of a neighbourhood or street, distinctions in housing form, or legal and political infrastructures. Attention to the relationship between sociability and material construction in any given space may produce a different perspective on the nature of convivial relations. Before outlining the case, however, I suggest we trace the intellectual genealogy of the notion of conviviality and demonstrate how Mbembe’s construction offers a distinctive perspective, which will be used to illuminate the case.

Conviviality and power

Whilst the anthropologists Joanna Overing and Alan Passess introduced a notion of conviviality to describe the aesthetics of everyday harmony and sociability amongst indigenous Amazonians (Overing and Passess Citation2000), Paul Gilroy’s intervention within cultural studies was to link it explicitly to urban life. Drawing on the philosopher Ivan Iillich (Citation1973), Gilroy first used conviviality to describe processes of vernacular cultural interaction in diverse areas of inner-city Britain. For him, conviviality is “everyday ordinary virtue” that is not “deformed by fear, anxiety and violence”, providing an alternative to official multiculturalism (Gilroy Citation2004, 149; also see Gilroy Citation2005). This framing allowed for an optimism about quotidian multicultures that does not overlook structural realities and legacies of racism, oppression, and exclusion.

Conviviality has since expanded across social sciences, describing forms and registers of interaction between people of difference in urban environments. This literature varies in its employment of the term, but there is a broadly positive valuation of urban cosmopolitanism implicit within it. The sociologists Sarah Neal, Bennett, and Cochrane (Citation2013) describe the “mundane competencies for living cultural differences” as “cool conviviality”. More recently, Neal has sought to foreground it “as a concrete social interaction” (Neal et al. Citation2017). The social anthropologist Susanne Wessendorf describes conviviality as a “commonplace diversity” in which differences are acknowledged and negotiated in semi-public spaces (Wessendorf Citation2014; cf. Duru Citation2015; Hall Citation2012; Radice Citation2016). “Human modes of togetherness”, Magdalena Nowicka and Steven Vertovec argue, should be interpreted through “notions of protection, neighbourliness, transience, negotiation and translation to interrogate the ways conviviality and conflict variably intertwine in everyday life” (Nowicka and Vertovec Citation2014, 342, 353).

These studies focus on the form of relations and attitudes between populations, without significantly addressing material and infrastructural affects on interaction. This article argues that in focusing on horizontal relations between humans, the separation of conviviality from conflict – even when understood as intertwined – obscures the power in and of the concept. Moreover, rather than through infrastructures, such studies have been centred around forms of management between groups (Neal et al. Citation2017; Vertovec Citation2015; Wise Citation2016). The case from Jaffa – a spatial and political context that departs from the bulk of conviviality studies – draws our attention to the fact the centring of spatial and material context can frame convivial relationality in a distinctive manner. Although some contemporary studies describe a conviviality that encompasses or encourages conflict, racism, and racialization (Karner and Parker Citation2011; Mattioli Citation2012; Wise and Noble Citation2016; Back and Sinha Citation2016; Valluvan Citation2016; De Noronha Citation2022), one can see how the broad trajectory of conviviality studies has departed from Gilroy’s formulation, and further attention to infrastructural urban production is one way to reconfigure such patterns.

In doing so, I draw on an emerging body of work that similarly reflects Gilroy’s earlier formulations. Les Back and Shamser Sinha, who turn to Gilroy to note the co-existence of conviviality and racialization, express their concerns over the ways the concept has developed, arguing “conviviality should not be a by-word for saccharine diversity fantasies” (Back and Sinha Citation2016, 523). Further attempts have been made to understand the concept in a more radical potential (Valluvan Citation2016; De Noronha Citation2022), where the reification of difference is refused, or where convivial intermixture is understood in relation to political contestation (Hall Citation2021, 26). The aim of this literature is to draw on Gilroy’s formulation of conviviality as unruly (De Noronha Citation2022), to understand “how is it substantively distinctive from the ideals of coexistence formalized by integration” (Valluvan Citation2016, 205),

The key theoretical transition, however, is to turn to Mbembe’s formulation and read it vis-à-vis Gilroy. Both rooted in postcolonial critique, Gilroy and Mbembe develop the concept from vastly contrasting geographical contexts. For both authors, the mundane is integral. For Gilroy, it signifies postcolonial hope, but for Mbembe, postcolonial absurdity. There is common ground too. For Gilroy, conviviality signifies the ways in which people live through and in racist systems and racialized worlds, and for Mbembe, through authoritarian horror. They thus point to the contradictory nature of social contexts that are driven by power imbalances. For Gilroy, however, conviviality exists in parallel to power systems. In contrast, this paper is concerned with the ways in which conviviality registers become the very ground of power.

Mbembe’s account captures this by locating conviviality in Mikhail Bakhtin’s “carnivalesque”, which he explores through the manifestations of postcolonial power in Cameroon. In, “Provisional Notes on the Postcolony” (Citation1992), and later in On the Postcolony (Citation2001), he formulates these ideas. Central to his claims are that postcolonial power has a banal quality. As in Bakhtin, ordinary people (la plébe) are shown to interact with power through obscenity and the grotesque, ridiculing the arbitrary nature of instruments of authority. Yet, in these acts, Mbembe argues, are reproductions and affirmations of state power. He writes that there is a

need to go beyond the binary categories used in standard interpretations of domination, such as resistance v. passivity, autonomy v. subjection, state v. civil society, hegemony v. counter-hegemony, totalisation v. detotalisation. These oppositions are not helpful; rather, they cloud our understanding of postcolonial relations. (Mbembe Citation1992, 3)

Research design

The case described and analysed below was produced through eighteen months ethnographic fieldwork conducted between August 2017 and March 2019. The research used observational, archival, visual, and audial methodologies together with informal interviews, forming an eclectic combination of ethnographic objects that are represented dialogically to reflect how the ethnography was conducted. Interviews and participant-observation were conducted with thirteen architects and planners, seventeen municipal workers – some of whom are residents of the neighbourhood, and an additional twenty-three residents from different ethnic groups, of different ages and genders. They are mostly residents of the shikunim, but four are residents of the bayarat. All were informed about the research project and verbally consented to recorded interviews. The methods of consent were approved by the University of Oxford Social Anthropology and Museum Ethnography EDRC (Departmental Research Committee) in advance.

Beyond the interview material, the ethnography incorporated documents, maps, and plans as active instruments during the process of research and sought to connect them to the on-the-ground analysis. The legal documents that form part of the evidence in this article are understood as places of spatio-material affect – what Yael Navaro has called “mutualised and mutualising spaces” (Navaro-Yashin Citation2007). The combination of these perspectives generated an analysis that attended to the multiplicity of ways of representing place within one bounded field site with “teeming multiplicity” (Candea Citation2009), hence understanding conviviality through distinctive temporal and spatial scales.

Jaffa’s urban fringes

The urban configuration through which the case is made is the southern fringes of Jaffa, one of five cities that were almost exclusively Palestinian-Arab prior to 1948. During the violence of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the majority of Palestinians dwelling in these cities were forced to leave their homes. From the foundation of the state of Israel up to April 1949, 110,000 of 190,000 Jewish immigrants arriving to the country had been settled in abandoned Arab houses, with most settling in the formerly Arab neighbourhoods of Jaffa and other “mixed cities” (Morris Citation2004, 395).Footnote2 In the shadow of a war that led to what Palestinians call the nakba – the tragedy of 700,000 Palestinians fleeing the country or being ejected from their homes – cities with mixed Jewish-Palestinian populations emerged in the new State of Israel. In Jaffa, martial law was imposed on the remaining Arab community, and the old city and ‘Ajami neighbourhood became dilapidated.

By the 1960s, Jaffa had been dramatically transformed from an Arab metropolis into a chaotic, transitory city largely populated by Jewish immigrants. The construction of the neighbourhoods of Yafo Alif, Yafo Bet, Yafo Dalet and Yafo Gimmel was part of the Tel Aviv municipality’s masterplan for postwar Jaffa. These new neighbourhoods – the latter two being the basis of this study – were built according to functionalist-modernist ideals and were central to the national imagination of the nascent Israeli state (Kallus and Law-Yone Citation2002; Efrat Citation2018). Their construction came after a short-term goal of settling olim (new immigrants) in expropriated Palestinian homes (Monterescu Citation2015, 138). Many immigrants – who had arrived mostly from the Middle East and Balkans – spent their early years in co-habitation with Palestinians who remained in the city, sometimes sharing houses in the ghettoized neighbourhoods’ of ‘Ajami and Jabaliyye. Others spent years in ma’abarot (transit camps) on agricultural land on the city’s edges. The shikunim were supposed to flatten out the multiplicity and difference arriving in the city, but discriminatory housing practices tended to favour European inhabitants over Mizrahi immigrants (Smooha Citation1989; Yiftachel Citation2001). During this period, Palestinians remained in ‘Ajami, but the shikunim of Yafo Dalet and Yafo Gimmel were constructed around the agricultural collectives known as bayārāt (orchards). Thus, there remained a minority of Palestinians in these new proletarian neighbourhoods.

Today, the neighbourhoods are marked, more than ever, by the juxtaposition of the shikunim and pardesim/bayārāt of each neighbourhood, where around 500–700 people live. Bayārat Abu Seif in Yafo Dalet and Bayārat Daka in Yafo Gimmel stretch over a large part of each neighbourhood and cut into an otherwise even urban texture (there is another area called Bayārat Turq in Yafo Dalet but this is considerably smaller). Today, they are referred to as “compounds”, “enclaves”, and “ex-territories” by different actors in distinctive discursive arenas. Historically, the bayārāt areas were an expansive, open landscape of agricultural plots encircling the built city of Jaffa. They grew the fruit of Palestine’s greatest industry, the world-famous Shamouti orange. The well-houses that irrigated the orchards (bayārāt) took this name, eventually coming to define the entire dwelling arrangements around these operations. Today these areas are often referred to by the Hebrew word pardes (orchard). These extended families were part of the few Palestinians who remained after the 1948 nakba that led to Jaffa being emptied of 97 per cent of its original Palestinian-Arab population. They continued to function as open agricultural plots for decades, as informal housing sprawled around them ().

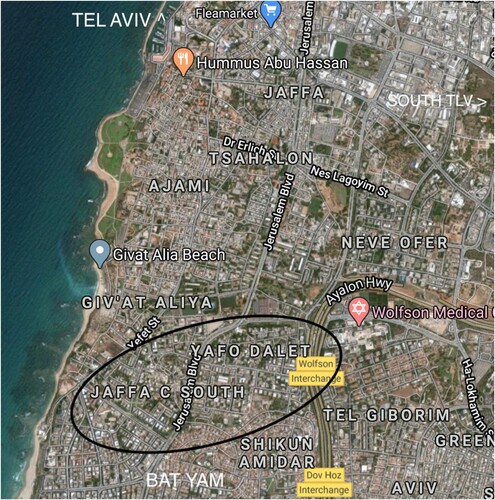

Figure 1. Bordering historically Palestinian-Arab Jaffa and the Jewish city of Bat Yam, Jaffa’s urban fringes defined in the South of the map. Source: Google Maps.

Today, considerably less land is available for agriculture, and parts of both families turned to crime and drug supply in the 1980s. Members of the family I spoke to claim that such activities, originally perpetuated by only specific individuals within the bayārāt, have now ceased altogether. A high level of surveillance by the Israeli police nonetheless remains. Red and blue flashing lights, gray uniforms, and M16s and M4s usually reserved for the Israeli Border Guard operating the Occupied Palestinians Territories, are routinely part of the sensoria and symbolic materiality of the neighbourhoods, particularly around the bayārāt/pardesim. It is common for armed units to place themselves outside entrances to both bayārāt/pardesim, and for family members to protest the lack of pretence on online forums and in the press. The relationship between the police and the Jaffa Arab community in general is fraught. There is a perceived failure by the population to put resources into dealing with criminal elements within the community, as well routine police harassment, and excessive police force leading to shootings of unarmed Arab youth (Monterescu Citation2017). But the relationship with the bayārāt is even more tense, and the repercussions of such criminalization can be detected in the perception of relations between residents of the bayārāt/pardesim and shikunim. As the legal threat of expulsion becomes more real, the physical juxtaposition with the shikunim has taken on social dimensions too.

We can see how these urban configurations are defined by the uneven relations between populations and state apparatus. Yet low socio-economic status and urban density are shared features in both dwelling configurations. It is important to note therefore that conviviality is often experienced in situations of high urban density, where the duality of diversity and density produce forms of precarious living together (Nyamnjoh Citation2017, 264). In Jaffa’s urban margins, we see how such precarity endures in a convivial atmosphere. Over decades, the bayārāt grew into “villages-within-neighbourhoods”, gated areas in legal battles with the Israeli state and Tel Aviv-Jaffa municipality. In recent decades, there has been new arrivals of Jewish immigrants from the Former Soviet Union and Ethiopia, as well as Palestinians pushed south from the gentrified neighbourhoods of northern Jaffa, and some migrant workers from Nigeria and Philippines. They join the mostly Mizrahi (Middle Eastern) veteran Jewish residents to create the area’s current configuration of urban diversity. Observing the relationship between sociability, materiality and underpinning planning policies and legal infrastructures, we may understand forms of convivial life in a distinctive way ().

Legality and deception

The politics of planning lurking under the surface is demarcated in the 2017 City Planning Division document for Shikunei Drom Yafo (the neighbourhoods of southern Jaffa) (ATH Citation2017), which lays out plans to build tower blocks on much of the areas of both bayārāt. In the document, mitham (compound) is used to describe the areas, repeating their sense of temporary status, and gray legitimacy. Behind the scenes of everyday life is a juridical warfare which may entrench the fate of these lands. Such processes do not exist in a vacuum. The beliefs of Jewish-Israeli inhabitants are often commensurate with the behaviour of the state, whose power is entangled with the convivial.

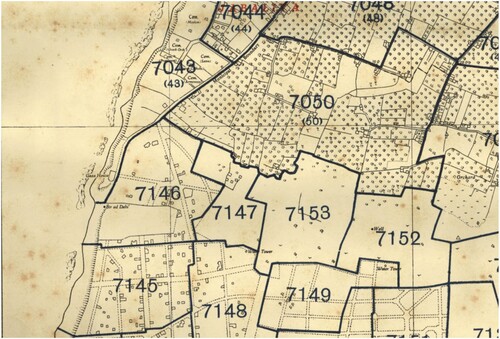

This section focuses on the regime through the legal battle of the Abu Seif family, though the Daka family – who bought their land in the 1940s from the famous bourgeoisie Dajani family – are also undergoing a battle for legitimacy. The Abu Seif family has filed suit against The State of Israel, the Tel Aviv Municipality, Reshut HaPituach (the Development Authority), and a private company. They claim that despite residing in the area for a continuous period of two-hundred years, ownership of the complex – excluding 2395 sqm of plot 22 in gush (block) 7050 which was registered by Mustafa Sayeed Abu Seif – was illegally transferred to the State of Israel, the Reshut HaPituach (Development Authority), Tel Aviv Municipality, Chevrei HaYemenuta (a subsidiary of the Jewish National Fund). At no point had the Abu Seif family been made aware of their property rights in the area. The family owned another fifty dunams in the area of the neighbouring city, Bat Yam, which was expropriated in 1948 after the conquest of the area, as well as a two dunam area across Mahrozet Street, which had land and a perimeter, but is now a shikun and mercez meshari (commercial centre). This is the exact same geographical location as described in the opening scene, where an everyday sociability between Jewish shopkeepers and Abu Seif family members was made evident. The legal infrastructures undergirding this scene thus force us to interrogate further whether such social relations are based on shared beliefs and trust. To understand this, we need to reflect on the legal processes that have led to uneven land rights ().

Figure 3. The numeration of space through the gushim delineation. The Israeli state claims the areas defined by the state are gush (block) 7048 and 7050, although a British map from 1932 (above) demarcates these areas as agricultural plots (bayārāt/pardesim) which the Abu Seif family claim as legal inheritance. Source: Israel Mapping Center, Tel Aviv.

Since the early 1960s, when the Tel Aviv Municipality tried to evacuate the family from the land located “in the middle of the neighbourhood”, as court documents describe, the family’s position has remained legally precarious. The gray space of legitimacy has been made visible by attempts to sell areas of the land to private developers. This is part of process in Jaffa in which the state began selling land which had been expropriated by the Israel Land Authority (ILA) in the early 1950s and had since then been leased to informal tenants. This process began in 1996, with the advent of gentrification in Jaffa, where the claim was ostensibly to grant leasers formalized housing status by allowing them to purchase property from ILA. But few could afford it (Avni and Yiftachel Citation2014, 498). Market forces now replace the state in combating informality in neoliberal Jaffa (Avni and Yiftachel Citation2014, 499; c.f. Monterescu Citation2015, 135–207). The ILA and public housing companies had originally been entrusted with the guardianship of land expropriated under the Absentee Custody Law. Whilst decidedly not absentees, the Abu Seif case shows government intentions to issue a tender for the sale of land, with the winner of the auction to be responsible for the evacuation of the complex and the compensation of family members. The case presents evidence demonstrating dialogue between a real estate company called Beach Estate and the Tel Aviv Municipality.

The family are now asking for the High Court of Justice to accept their claim, give a declaratory judgement that attests to the family’s rights, and to register such rights in the land registry books. Finally, they are seeking formal recognition of the merimah (deception) by actors at the time of the registration of hasdar (settlement) and/or haluka (division). Seeking legal legitimacy, the processes echo emerging practices in East Jerusalem, where independent plans are being submitted by informal residents. Perceived to be inhabiting “chaotic spaces of legality”, such submissions are forms of re-appropriating and re-tooling (Braier and Haim Citation2017, 13). Winning the case might be seen as an instance of “quiet encroachment” (Braier and Haim Citation2017, 13), and their ability to maintain residency over the decades has gained the family respect in the Jaffa Arab community, representing a form of ṣumūd (steadfastness).

A form of public culture that we may think of as a form of ṣumūd occurs on Fridays during citrus season. Members of Bayārat Abu Seif sell a range of oranges and grapefruits to the residents of Yafo Dalet on the main street of the neighbourhood. Their main customers are vatiḳim who stop by in their cars to acquire bags of oranges and grapefruits for shabbat, hanging out, catching up, and exchanging jokes and memories with the Abu Seif family members. Here, the historic life of the bayāra still emerges in the practice of setting up citrus markets on Mahrozet Street. More than a sign of the past, it reflects the strong social presence of Abu Seif beyond the area of the bayārāt, and in the heart of Yafo Dalet.

Yet the blatant contradiction at the core of the issue is the quotidian coexistence of regimes of merimah (deception) and practices of sociability. Deception here is understood as a set of affective and intentional social patterns mediated by the dual materialities of legal documents and built form. This is indicated by the broad acceptance of illegitimacy by Jewish residents that has increased over time, to the point where it is has become a normative sentiment. This contradiction represents a double deception, instigated from above and below – through the institutions of the Israeli state and residents who reproduce its legitimacy. “Hagvulot shel HaPardes (the borders of the orchard)”, a term employed within legal documents surrounding the case, is a term produced in multiple discursive domains. The status of the borders of both bayārāt have shifted dramatically over time, with social conceptions adjusting accordingly.

Social and material separation

The spatial division between the shikunim and the bayārāt is the most radically distinctive feature of the built environment in southern Jaffa. Although histories of social intimacy and relationality between bayārāt-dwellers and vatiḳim (veteran residents) persist into the present day, a dominant discourse has emerged that pertains to a correlation between the spatial and the social. As Mohammed, a Jaffa resident and cultural manager at the Meshlema put it:

Okay, I can’t tell you if the perception is right, or if they are right-wing but they always say, “you’re there, and we are here,” apart from the two pardesim. You have nothing to look for here. As far as the Arab community is concerned, this is where the Jews are supposed to be, and this has been a Jewish area. So much so that in the consciousness of the Arab community, Yafo Gimmel/Yafo Dalet does not belong to Jaffa except for the pardesim. Leave the borders on the map, but in terms of feeling, they feel like they don't belong there.

Amos buys oranges on Fridays during the citrus season. He is a forty-five-year-old veteran Yafo Dalet resident of Libyan origin. His parents were residents of the ma’abara (transit camp) that was established next to Bayārat Abu Seif during the 1950s-60s and became residents of the shikunim when they were constructed. Growing up in this shikun (singular block) in the neighbourhood, he eventually served as head of the vaʻad shikunah (neighbourhood committee) for seven years and is a well-known figure across the neighbourhood. Unlike many of the friends he grew up with, he intends to stay in the neighbourhood. Asked about the greatest challenges in Yafo Dalet, he remarks

The first problem we have in the neighbourhood is with the area of Abu Seif. One the one hand, they are a good family, but on the other, there are some families within with drugs, weapons, and a lot of groups of shabahi [term used to describe Palestinians from the Occupied Palestine Territories], from Palestine, they’re not Israelis. No ID. But this is not the problem, the problem is drugs and the drugs here are a very big problem because they use the teenagers to sell drugs. Many people don’t want to buy apartments and many people leave the neighbourhood because of the crime and drugs. This is a big problem for us.

New residents, by contrast, would not be seen purchasing oranges or any other produce from the family (they also have a permanent store that sells basic groceries). As new populations could not maintain the same connection, neighbourhood formation was thick but its branches thin. As Hewitt (Citation1986) notes, negotiation and dialogue between different ethnic groups often coexists alongside exclusion of other groups, particularly refugees or recent migrants. Recent immigrants like the Ethiopian population have no relationship with the family, and no deep memory of intimate sociality in the area over time, but for long-time veteran families, there is an ambivalence that needs unpacking. When one looks at formal representations of community in the neighbourhood, one begins to understand how relations between vatiḳim and the Abu Seif family have become superficial.

In addition to the vaʻad shikunah, Yafo Dalet has maintained a moʻetsa (council) for the last fifteen years. A project instituted by the individuals from long-standing veteran families, it is ostensibly a representative body for the discussion of concerns amongst the neighbourhood’s diverse populations, and for those working in care, social support and development roles within the neighbourhood. Yet remarkably, no Abu Seif has ever been present at a meeting. In one of the council meetings, Orli, the manager of the neighbourhood’s community centre, announced that she is intending to meet the Abu Seifs and deepen connections. Yet the announcement was inflected with a sense of futility, with many attendees believing it is highly unlikely an Abu Seif will ever join the council. It is only on the request of left-leaning municipal and NGO workers that such an idea was raised at all. What is more conspicuous is the length of time within which an exclusive community was produced through discussion, nurture, and separation.

This sense of exclusivity, however, is also marked by a narrative of schism; of a more socially and spatially open past. Indeed, many vatiḳim characterize their relationships with the families of the bayārāt/pardesim as a shift from friendship across and movement between the spaces of the shikunim and the bayārāt/pardesim to further separation and a virtually complete lack of interaction today. The terrain of possibility for convivial interaction has been subject to material shifts over time, and this is signified by the perspective of new residents. A small but growing phenomenon due to rising house prices and municipal plans to implement urban renewal, some middle-class individuals have moved to the neighbourhood with the hope for it to “improve”. Lilach, a forty-year-old single-mum who sits on the vaʻad shikunah (neighbourhood committee) for Yafo Dalet, has never entered Bayārat Abu Seif and thinks of it as a mystery. She states

They are in their own world; they are not involved in anything. They are outside, outside of all this thing. And this is also a thing I hope we will be to change one day. Right now, it is like a kasbah, a closed place, you cannot enter it. I tried to enter. What does it mean to enter? I took the wrong way, and I entered there. Very quickly they showed me the way out. It is not possible to walk there. I believe that with the urban renewal, as I see it, also this population will change.

However, one narrative indicates a slightly more ambivalent position that Jewish residents also often express. Albert, a fifty-two-year-old Hungarian Jewish immigrant who lives in a shikun with his Slovakian wife and his son from his first marriage, is spearheading the renovation project in his block on Saharon Street at the border of Yafo Dalet and Yafo Gimmel. He sees the TAMA”38 project – an economic scheme allowing developers to add levels to existing buildings on the condition that they provide existing residents with some extra space and amenities – as a “gift”. He is insouciant about the difficulties for elderly residents and the populations he thinks will have to leave, including Ethiopian-Israelis. About Daka, he states:

It should disappear from here. It’s not their place. They took 80% of this place from the Municipality of Tel Aviv. From the country. This place is not their place. It doesn't matter [that they’ve had it since 1948]. They will take money, and they will go from here. [But] I prefer that they stay here. You know why? Look out of the window. Everything is empty. If they leave the place, they’re going to build forty, fifty floors. It’s not nice for me. It’s pretty now. I want to believe that they will stay here but I know it’s not what will happen because its more than twenty/thirty years that the Municipality of Tel Aviv has been fighting here. And they haven’t got papers showing that they bought it. They haven't. They haven’t got anything.

This ambiguous narrative accepts state sovereignty, whilst contradictorily admiring the aesthetic effects of pre-state agricultural societies on the landscape (). The separation of this landscape from the neighbourhood’s projected future highlights its increasing sense of otherness amongst Jewish residents. In Yafo Dalet, orange orchards peer above gray metal gates, apartment blocks built in the 1980s towering over. New residents regularly walk past these layered juxtapositions in both neighbourhoods, unaware of the historical significance of the scene, of how strings have been pulled to deliberately orchestrate it. It is, as Mbembe writes, “a hollow pretence, a regime of unreality” (Citation1992, 8) ().

As the state and municipality have plotted with real estate agents to mount further encroachments on the property of the bayārāt, and this has filtered down into neighbourhood discourse, social engagement has been constantly undergirded by the power of the state. It could be argued therefore that Palestinian residents of the bayārāt perform and institutionalize state norms through forms of convivial engagement with Jewish residents. Yet they also play with them at the same time through performative gestures articulating the continuity of the pre-1948 past; “They are constantly undergoing mitosis, whether it be in ‘official space’ or ‘not’” (Mbembe Citation1992, 5). If the convivial has become doublespeak, however, we must look elsewhere to find where state power is resisted and reimagined.

Imagined geographies

If convivial social relations co-exist with legal infrastructures that delegitimise residents of the bayārāt and the filtering through of legally constructed merimah (deception) into the beliefs of Jewish residents, where might we find the space of Palestinian alterity? The ways in which residents of the bayārāt respond to their feelings of material and social separation offer some insight. Rima Abu Seif is a thirty-year-old archaeological assistant at Tel Aviv University. She lives in a house in Bayārat Abu Seif with her parents and siblings. Her father, Faisal, is the son of Mustafa Abu Seif, the only member of the family to stay in the area in 1948, ensuring the land was not completely lost under the Absentee Property Laws that followed the formation of the State of Israel. Rima is active in Jaffa’s various online communities on Facebook, as well as in Palestinian cultural networks. When it comes to her own area, however, she feels isolated, stating “I don’t go around my neighbourhood.” She describes the increasing physical isolation over her own lifetime as a further depreciation of the freedom to practice Palestinian life on the land. Yet the relationship she had with her grandfather indicates a sustenance of Palestinian life:

Growing up, we went to visit him every time, he didn’t need to force culture on me. He just like took me around, he showed me how to feed the goats, feed the chickens, and go around collecting foods everywhere. He showed me the Palestinian lifestyle, and how to learn Palestinian culture without forcing it. He was the ultimate Palestinian, without saying any words.

Jabaliyye was a district with different bayārāt inside it. Bayārāt means orchards, but not in the concept of your Western orchards, but more in the concept of our orchards. Bayāra comes from the world biʾir, which means you must have a well to have an orchard, and that’s the land of peasants. It’s very different. So, lots of families had wells and they had the bayārāt, and it was all open – no gates and borders and everything. You didn’t have that. You could cross the neighbourhood and everything. You had orange groves, lots of horses, lots of cows, lots of chickens, and you had a place to sleep, but mostly they were like going around inside the house – not the cows though as they are too big! But imagine living like this in that period when you’re like a small family. It was like paradise!

So, most of the families around us fled to Jordan, Gaza, or part of my family is in Ramle today. The thing is that the bayāra in front of us was Abu Hasouna and they today fled to Lydd [another ‘mixed city’ not far from Tel Aviv]. So, they fled to Lydd, and today you have stores in front of us and shikunim but what my dad told me was that these were actually a maʻabara (transit camp). He told me that, you know, they used to not have the municipality and everything and the orchard was full of fruits and vegetables, and the Jews were like coming in and out, and I asked him, so why do our neighbours really hate us? Because they don’t remember!

Despite the historic possibilities attributed to such moments of encounter, and the deeper but rarer forms of relationality that also emerged, Rima was quick to point out that “you have the bubble of Jaffa, and you have the bubble of bayāra. And it’s a very protective bubble”. Here she points to the reality of social isolation, but also to the possibilities of the interior of the bayāra cradling mnemonic geographies. This metaphor is perhaps even more pronounced for the Daka family, who are believed to originate from Gaza, and who speak a distinctive dialect from the rest of Jaffans, more recognizable in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Yet such cultural and linguistic specificities do not necessitate an absolute social and spatial distance. Threads of spatial imagination extend between the texture of the bayārāt and the rest of the neighbourhoods, which can be subversive to everyday power. It is in these threads that “they can … shut it up and render it powerless” (Mbembe Citation1992, 8). Hannah Baumann has argued with regards to segregated Palestinian spaces in Jerusalem, “enclaves are not static, but are consistently undermined and re-made through quotidian practices” (Baumann Citation2015, 173). Whilst I do not claim that there is an everyday subversion of the political regime in the social navigation of bayārāt dwellers, we can see how specific kinds of Palestinian experience beyond the space of the bayārāt may challenge the production of space. Rima’s imaginary is also expressed through real audial and material markers in the space of the neighbourhoods. Subtle forms of Palestinian presence which relate to the memory of the past form in southern Jaffa’s urban life, demonstrating ways in which marginalized actors decompress the normative spatial and temporal order (Sopranzetti Citation2014). This does not rely on the negotiated behavioural patterns of convivial engagement between residents (although it may have in the past and may still in rare cases), but rather on the insertion of Palestinian identity in Israeli political space. They do not, however, alter the “logic of conviviality”, which “inscribe[s] the dominant and the dominated within the same episteme” (Mbembe Citation1992, 10). In the conclusion, I reflect on the need to consider the relationship between power relations and the built environment when unpacking the stage of conviviality.

Conclusion: conviviality and domination in Israel/Palestine and beyond

Strangulated by legal precarity, social presence within the neighbourhoods and convivial relations between residents of bayārāt and shikunim over time have, within moments, provided cracks in the state’s spatial organization of the area. It has, however, been shown that convivialities in Israel/Palestine emerge through immediate spatial inequalities. In any situation, the convivial can be subject to power relations, but this is particularly pronounced in Israel/Palestine, where state-generated processes of separation and deception encourage stigmatization, territorial urban attitudes and perceptions of insularity and incarceration. Urban social relations are informed by the materialization of state sovereignty and the juridical power of the Israeli Land Authority. State organs mediate collective beliefs of the impermanent, illegitimate, and criminal presence of bayārāt dwellers, and in doing so represent the everyday materiality of statecraft (Hansen and Stepputat Citation2001; Navaro-Yashin Citation2012). Thus, there is a contradictory reality in which conviviality can be practiced in an exchange amongst non-equal subjects of the state, city, and neighbourhood. As the state has further cemented regimes of separation, forms of social exchange between residents have become deceptive, rather than unruly (Gilroy Citation2004, De Noronha Citation2022) or destabilizing (Valluvan Citation2016, 218).

Mbembe states that he is specifically interested in the reality of a “postcolonial mode of domination” as a “regime that involves not just control but conviviality, even connivance” (Citation1992, 24–25). The application of this logic to the social world of mixed Jewish-Palestinian cities and to Palestinian citizens of Israel provides a way of explaining the duality of power and everyday sociality. There is network of beliefs that reaffirm Jewish sovereignty and are continuously reinstated through the materiality of the built environment and the way in which its segregating functionality produces deceptive interactions. Conviviality then, must be added to the other modalities of resistance and disorder, which are “all inherent in the postcolonial form of authority” (Mbembe Citation1992, 25).

To take notice of conviviality as a site of power, however, is not to absolve the possibilities of living together. In Israel/Palestine, moments of recognition of the Other in dense urban space might well be the seeds of a more just future for Palestinians. The life of the bayārāt is Palestinian life, and the ways in which cultural expressions and practices seep out of its “borders” are not insignificant. Yet the ways in which its social outputs appear contradictory or stunted must constantly be grappled with. The conceptual framing of conviviality benefits from not backgrounding material infrastructures to social interactions. Borrowing from cultural geography, we may see everyday moments of conviviality as mediated through a repertoire of multi-sensory encounters (Amin and Thrift Citation2004), infrastructurally connected through “thrown-togetherness” (Massey Citation2005). But the point is not to affirm “the principle of convivium or living together without the necessity of recognition” (Amin Citation2012, 74). Whilst the focus on this paper has been on what Amin would refer to as “the rhythms of territorialization … and the aesthetics of space” that “work … on the senses in a silent way” (Amin Citation2012), the case described above refers to an intimate conviviality grounded by a sociability with recognition. It is thus contextually and practically distinctive, with relationality not omitted from the picture, but rather drawn into an infrastructural matrix. It is this intimacy that shows, with reference to Mbembe’s argument, that the convivial can be a deceptive mode of sociability.

In this picture, forms of conviviality articulate everyday life as an amalgam of power relations, urban infrastructure, and history. Convivial relations between residents are understood through the built environment and the materiality of state or capital-generated property regimes, rather than between ethnic groups. Diverse urban configurations in general would benefit from a richer engagement with the active role of the built environment and the ways in which conviviality can deceptively reproduce power structures when understood from this perspective. This need not purge us of optimism, but rather may lead us to promote ways of living together that are effective, resilient, and based on trust and more equitable material conditions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Neal, Bennett, and Cochrane (Citation2013, 317) reference this argument of Mbembe’s to explain how conviviality can be a mode of maintaining social order from which to extract “possibilities … for the management of cultural difference in England.” It seems to me to be rather odd to intepret Mbembe’s argument in such terms, for it is the maintenance of an unjust social order that Mbembe refers to.

2 Jaffa, Haifa, Acre, Lydda/Lod, and Ramle, along with two Israeli-Jewish towns which subsequently became mixed, the joint experimental community Neve Shalom/Wadi Salam, and Jerusalem, are the only spaces in which Jews and Palestinians cohabit in Israel today. 8.6% of the Israeli state’s Arab population resided in these five cities as of 1991 (Falah Citation1996, 829).

References

- Amin, Ash. 2012. Land of Strangers. Cambridge: Polity.

- Amin, Ash, and Nigel Thrift. 2004. “The ‘Emancipatory’ City?” In The Emancipatory City?, edited by Loretta Lees, 201–204. London: Sage Publications.

- Arendt, Hannah. 1970. On Violence. New York: Harcourt.

- ATH (Agaf Tochnit Ha‘Ir – City Planning Division). 2017. [Hebrew] “Shikunei Drom Yafo (Neighbourhoods of South Jaffa).” Tel Aviv Yafo Municipality March 2017.

- Avni, Nufar, and Oren Yiftachel. 2014. “The New Divided City? Planning and ‘Gray Space’ Between North-West and South-East.” In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, edited by Susan Parnell and Sophie Oldfield, 487–505. London: Routledge.

- Back, Les, and Shamser Sinha. 2016. “Multicultural Conviviality in the Midst of Racism’s Ruins.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 517–532.

- Baumann, Hannah. 2015. “Enclaves, Borders, and Everyday Movements: Palestinian Marginal Mobility in East Jerusalem.” Cities 59: 173–182.

- Braier, Michal, and Yacobi Haim. 2017. “The Planned, the Unplanned and the Hyper-Planned: Dwelling in Contemporary Jerusalem.” Planning Theory and Practice 18 (1): 109–124.

- Caldeira, Teresa. 1999. “Fortified Enclaves: The New Urban Segregation.” In Cities and Citizenship, edited by James Holston, 114–138. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Candea, Matei. 2009. “Arbitrary Locations: In Defence of the Bounded Field-Site.” In Multi-Sited Ethnography: Theory, Praxis and Locality in Contemporary Research, edited by Mark Falzon, 25–46. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Cook, J., P. Dwyer, and L. Waite. 2011. “‘Good Relations’ Among Neighbours and Workmates? The Everyday Encounters of Accession 8, Migrations and Established Communities in Urban England.” Population, Space, and Place 17: 727–741.

- De Noronha, Luke. 2022. “The conviviality of the Overpoliced, Detained and Expelled: Refusing Race and Salvaging the Human at the Borders of Britain.” The Sociological Review 70 (1): 159–177.

- Duru, Deniz Neriman. 2015. “From Mosaic to Ebru: Conviviality in Multi-Ethnic, Multi-Faith Burgazadası, Istanbul.” South European Society and Politics 20 (2): 243–263.

- Efrat, Zvi. 2018. The Object of Zionism: The Architecture of Israel. Leipzig: Spector Books.

- Falah, Ghazi. 1996. “Living Together Apart: Residential Segregation in Mixed Arab-Jewish Cities in Israel.” Urban Studies 33 (6): 823–857.

- Gilroy, Paul. 2004. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? London: Routledge.

- Gilroy, Paul. 2005. “Melancholia or Conviviality: The Politics of Belonging in Britain.” Soundings 29: 35–46.

- Hall, Suzanne. 2012. City, Street and Citizen: The Measure of the Ordinary. London: Routledge.

- Hall, Suzanne M. 2021. The Migrant’s Paradox: Street Livelihoods and Marginal Citizenship in Britain. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hansen, Thomas Blom, and Finn Stepputat. 2001. States of Imagination: Ethnographic Explorations of the Postcolonial State. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Heil, Tilmann. 2014. “Are Neighbours Alike? Practices of Conviviality in Catalonia and Casamance.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (4): 452–470.

- Hewitt, Roger. 1986. White Talk, Black Talk: Inter-racial Friendship and Communication Amongst Adolescents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Iillich, Ivan. 1973. Tools or Conviviality. New York: Harper and Row.

- Jones, Hannah, Sarah Neal, Giles Mohan, Kieran Connell, Allan Cochrane, and Katy Bennett. 2015. “Urban Multiculture and Everyday Encounters in Semi-Public, Franchised Cafe Spaces.” The Sociological Review 63: 655–661.

- Kallus, Rachel, and Hubert Law-Yone. 2002. “National Home/Personal Home: Public Housing and the Shaping of National Space in Israel.” European Planning Studies 10 (6): 765–779.

- Karner, Christian, and David Parker. 2011. “Conviviality and Conflict: Pluralism, Resilience and Hope in Inner-City Birmingham.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (3): 355–372.

- Low, Setha M. 2001. “The Edge and the Center: Gated Communities and the Discourse of Urban Fear.” American Anthropologist 103 (1): 45–58.

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications.

- Mattioli, Fabio. 2012. “Conflicting Conviviality: Ethnic Forms of Resistance to Border-Making at the Bottom of the US Embassy of Skopje, Macedonia.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 27 (2): 185–198.

- Mbembe, Achille. 1992. “Provisional Notes on the Postcolony.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 62 (1): 3–37.

- Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Monterescu, Daniel. 2015. Jaffa Shared and Shattered: Contrived Coexistence in Israel/Palestine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Monterescu, Daniel. 2017. “Arab Lives Matter: How a Police Killing in Jaffa Could Spark a Movement.” Haaretz, August 2.

- Morris, Benny. 2004. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2007. “Make-Believe Papers, Legal Forms and the Counterfeit: Affective Interactions Between Documents and People in Britain and Cyprus.” Anthropological Theory 7 (1): 79–98.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2012. The Make-Believe Space: Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Neal, Sarah, Katy Bennett, and Allan Cochrane. 2013. “Living Multiculture: Understanding the New Spatial and Social Relations of Ethnicity and Multiculture in England.” Environment and Planning C 31: 308–323.

- Neal, Sarah, Katy Bennett, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2017. Lived Experiences of Multiculture: The New Social and Spatial Relations of Diversity. London: Routledge.

- Nowicka, Magdalena, and Steven Vertovec. 2014. “Comparing Convivialities: Dreams and Realities of Living with Difference.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (4): 341–356.

- Nyamnjoh, Francis B. 2017. “Incompleteness: Frontier Africa and the Currency of Conviviality.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 52 (3): 253–270.

- Overing, Joanna, and Alan Passes. 2000. The Anthropology of Love and Anger: The Aesthetics of Conviviality in Native Amazonia. London: Routledge.

- Piekut, A., and G. Valentine. 2017. “Spaces of Encounter and Attitudes Toward Difference: A Comparative Study of Two European Cities.” Social Science Research 62: 175–188.

- Power, Andrew, and Ruth Bartlett. 2015. “Self-Building Safe Havens in a Post-Service Landscape: How Adults with Learning Disabilities are Reclaiming the Welcoming Communities Agenda.” Social and Cultural Geography 1–21.

- Prytherch, David L. 2021. “Reimagining the Physical/Social Infrastructure of the American Street: Policy and Design for Mobility Justice and Conviviality.” Urban Geography 43 (5): 688–712.

- Radice, Martha. 2016. “Unpacking Intercultural Conviviality in Multiethnic Commercial Streets.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 432–448.

- Rishbeth, C., and B. Rogaly. 2017. “Sitting Outside: Conviviality, Self-Care and the Design of Benches in Urban Public Space.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43 (2): 284–298.

- Smooha, Sammy. 1989. Arabs and Jews in Israel, Volume 1: Conflicting and Shared Attitudes in a Divided Society. San Francisco, CA: Westview Press.

- Sopranzetti, Claudio. 2014. “Owners of the Map: Mobility and Mobilization among Motorcycle Taxi Drivers in Bangkok.” City and Society 26 (1): 120–143.

- Tyler, K. 2020. “Suburban Ethnicities: Home as the Site of Interethnic Conviviality and Racism.” The British Journal of Sociology 71 (2): 221–235.

- Valluvan, S. 2016. “Conviviality and Multiculture: A Post-Integration Sociology of Multiethnic Interaction.” Young 24: 204–221.

- Vertovec, S., ed. 2015. Diversities Old and New: Migration and Socio-Spatial Patterns in New York, Singapore and Johannesburg. London: Springer.

- Vodicka, Goran, and Clare Rishbeth. 2022. “Contextualised Convivialities in Superdiverse Neighbourhoods – Methodological Approaches Informed by Urban Design.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 43: 228–245.

- Wessendorf, Susanne. 2014. “‘Being Open, but Sometimes Closed.’ Conviviality in a Super-Diverse London Neighbourhood.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (4): 392–405.

- Wise, A. 2009. “Everyday Multiculturalism: Transversal Crossings and Working Class Cosmopolitans.” In Everyday Multiculturalism, edited by A. Wise and S. Velayutham, 21–45. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wise, A. 2016. “Becoming Cosmopolitan: Encountering Difference in a City of Mobile Labour.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (14): 2289–2308.

- Wise, Amanda, and Greg Noble. 2016. “Convivialities: An Orientation.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 423–431.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2001. “Centralized Power and Divided Space: ‘Fractured Regions’ in the Israeli ‘Ethnocracy’.” GeoJournal 53: 283–293.