ABSTRACT

How do race and class intersect in state practices of nation-building? This is one of the key themes in Jennifer Elrick’s book Making Middle-Class Multiculturalism: Immigration Bureaucrats and Policymaking in Postwar Canada. In this essay, I discuss Elrick’s conceptualization of the relation between race and class, which combines notions of class as a component of race on the one hand, and class as intersecting with race on the other hand. I argue that the intersectional perspective is most convincing. Elrick shows that the cultural and moral traits which bureaucrats ascribe to applicants – integrity, ambition, trustworthiness, initiative and self-reliance – are part of both racial classification systems and class classification systems. I therefore conclude by proposing to think of the intersection of class and race in state classificatory practices as consisting in an overlap in the criteria for allocating individuals to the categories of class and race.

Introduction

How do states produce nations? For twenty years now, this question has been a driving force in my professional life. I study migration politics because I am fascinated by the boundaries that governments draw between insiders and outsiders of the nation. As such I am part of a lively scholarly community which strives to unearth the – often implicit – stories and images that underly migration policies and politics: stories and images about who “we” are, what “we” share, and what a citizen – that imagined typical member of the imagined national community – looks like.

This scholarship has just been enriched with a new book, which I hope and trust will make a splash: Jennifer Elrick’s Making Middle-Class Multiculturalism. This book delves into the everyday decision-making practices of high-level migration bureaucrats in Canada in the 1950s and 1960s, a crucial period in which Canada made the shift from a race-based to a skills-based migration policy. In 1967, Canada introduced the points system it is famous for, which purports to select immigrants on individual criteria, namely merit – education, professional experience and language skills – and social ties to Canada, notably family ties. Until then, Canada’s migration policies deployed group-based criteria, particularly country of origin, to favour immigrants of European descent. Elrick convincingly argues that the groundwork for this decisive legislative shift was laid in the preceding fifteen years, in the practices of high-level migration bureaucrats. She shows that gradually, through trial and error, civil servants developed new ways of deciding which aspiring migrants were fit to become new Canadians, and which were not.

Elrick disagrees with the common view that race disappeared from Canadian immigration policies in the 1960s, to be replaced with the class as a selection criterion. Instead, she argues that both race and class have always been and continue to be part and parcel of Canadian nation-building through migration policy. The shift from group-level to individual-level selection should be understood not as the elimination of race from state categorization practices, but as “efforts to manage racial diversity at the intersection of social class” (Citation2022, 9). What Canadian migration bureaucrats were doing in the 1950s and 1960s, according to Elrick, is “manage racial inclusion by creating a new middle-class basis for a shared national identity” (Citation2022, 169).

Thus, Elrick explores how race and class intersect in state practices of nation-building. Elrick book’s shows that if you want to understand what “race” is and does, as well as what “class” is and does, everyday decision-making practices of migration bureaucrats are a great place to start. Her conceptualization of the relation between race and class is highly thought-provoking, combining notions of class as a component of race on the one hand, and class as intersecting with race on the other hand. In this contribution, I critically think through this element of Elrick’s conceptual argument to bring to light the insights it offers and questions it raises for myself and others seeking to understand the role of race and class in state classificatory practices.

Making race as a state practice

Elrick’s book shows, first, how much we stand to gain from bringing theoretical discussions on conceptions of “race” into dialogue with empirical data on the actual life of the category of “race”, and second, that one of the crucial places where “race” lives and may be empirically studied is the state bureaucracy. Elrick starts from the premise that “race and related categories like ethnicity and nationality are key categorizations used by states to describe and manage their populations” (Citation2022, 51). She defines race as a social category which “groups human beings together in oversimplified ways in reference to phenotype (race), culture (ethnicity), and/or geo-political region of origin (nationality) in ways that imply shared origin and traits”. She follows authors like Rogers Brubaker (Citation2009) in “seeing race, ethnicity and nation as functionally equivalent categorizations” which “in the hands of the state” may serve to include or exclude parts of the population (Citation2022, 51). She continues to argue that the “micro-practices” of everyday decision-making by migration officials are where the category of “race” is given form and meaning:

In their function as implementers, these state actors were required, on a regular basis, to articulate their understandings of immigrants’ racial classifications and their significance in practice, not just abstractly. (…) The deliberations about how to apply classifications to individuals and groups that occur in immigration policy formulation and implementation can reveal fine-grained information about the nature of the social distinctions underpinning such classifications. (Citation2022, 57, emphasis in the original)

Elrick’s analysis stands squarely in the analytical tradition that considers race and other social categories as context-dependent and shaped by power relations. Elrick’s notion of race as (re)produced by civil servants who creatively draw on cultural repertoires in admitting and refusing immigrants, shifting and shaping the meanings of “race” as they do so, strongly reminds me of Stuart Hall’s discursive conception of race as a “sliding signifier” (Hall Citation2017 (1994)). In studying state practices, Elrick heads the call of theorists of intersectionality like Patricia Hill Collins and Floya Anthias to turn “the lens … towards the broader landscape of power which is productive of social divisions” (Anthias Citation2012, 130). Elrick’s focus on the boundary work done by civil servants deciding migration cases resonates strongly with intersectionality theory’s premise that:

We should not see differences as empirically given but as part of a process relating to boundary-making and hierarchies in social life which might take different forms in different times and contexts and should be treated therefore as emergent rather than pre-given. (Anthias Citation2012, 131)

Race and class in state policies

According to Elrick, race and class both play a role in migrant selection. Elrick’s core argument is that “Making Middle-Class Multiculturalism” in Canada in the 1950s and 1960s involved not a replacement of selection on race by selection on class, but an endeavour to “manage racial inclusion by creating a new middle-class basis for a shared national identity” (Citation2022, 169). Her book is a fascinating study of how race and class relate to each other in the classificatory practices of state actors.

Scholarship on migration politics tends to think of economic rationales and identity rationales as distinct and often competing approaches to migration policy (Bonjour and Chauvin Citation2018). Rationalist political science perspectives tend to forefront economic rationales, while constructivist or political sociology approaches emphasize the identity rationales central to nation-states’ politics of belonging. Class is usually seen as part of the economic rationale, i.e. as pertaining to instrumentalist selection on employment, income, education, and the like. Elrick’s work belongs to the sparse scholarship which, in contrast, argues that “economic rationales and identity rationales are inevitably fused … in all migration policies and discourses” (Bonjour and Chauvin Citation2018, 7). More specifically, Elrick argues that class and race intersect in Canadian migration policies.

Elrick’s understands class as “a relational attribute ascribed to an individual or group based on socio-economic distinctions (e.g. perceived success, wealth, power), moral distinctions (e.g. perceived work ethic); and cultural distinctions (e.g. perceived level of education)” (Citation2022, 89). Thus, in contrast to scholars in the Marxist tradition for whom class is rooted in relations of production, Elrick builds on the work of Max Weber, Pierre Bourdieu, and Michèle Lamont to define class as consisting not only in “one’s material position in the socio-economic order” but also in “the status and honour attributed to one’s membership in social groups”. Thus, she argues that assigning an individual or group to a social class is based on socio-economic distinctions, moral distinctions, and “cultural distinctions” (Citation2022, 89). Referencing Lamont (Citation1992), Elrick argues that the criteria for assigning individuals to a certain social class include morals, attitudes, and values, so that “entrepreneurial spirit, ambition, drive for self-actualisation, and taste for upward mobility” are identified as “ middle-class values” (Citation2022, 89).

In many scholarly accounts that forefront the connections between race and class in the functioning of economic and political power, that connection is perceived as instrumental. Especially for scholars working in the Marxist tradition, be they decolonial theorists such as Aníbal Quijano or theorists of racial capitalism working in the Black radical tradition such as Cedric Robinson, the inextricable connections between class and race, i.e. between capitalism and racism, serve first and foremost to make possible the profit of some at the expense of the exploitation and dispossession of others.

In contrast, Elrick rejects the notion that selection on class, intersecting with race, is exclusively or primarily instrumental in an economic sense. Working from a cultural sociology perspective on class inspired by Weber, Bourdieu and Lamont rather than Marx, Elrick emphasizes that “notions of admissibility rooted in social class went beyond instrumental notions of economic utility” (94). The selection practices of migration officials were not geared only at allowing in those who would best serve the needs of the Canadian economy, or generate most wealth for the resident Canadian population. These assessments were also very much about which aspiring migrants best fit bureaucrats’ perceptions of the ideal Canadian citizen and ideal Canadian society.

Indeed, and crucially, Elrick’s account is one of nation-building. She constantly reminds us that in their everyday work practices, migration officials strive to shape a society that thrives, which they assume requires social cohesion and a shared (national) identity. Elsewhere, I have criticized scholarship on migration and integration policy for “fail[ing] to acknowledge that contemporary discourses on migrant integration reflect self-imaginaries of European societies as simultaneously classless and middle-class” (Bonjour and Chauvin Citation2018, 7). In stark contrast, Elrick shows thoroughly and convincingly that migration officials’ assessment practices are heavily classed because the conceptions of national identity and ideal citizenship that drive their work practices are heavily classed.

Conceptualizing the relation between race and class

Elrick’s conceptualization of the relation between race and class is complex, multiple, and at times ambivalent. Reading her book made me realize that I have not been all that clear about the relation between race and class in my own work either. Therefore, I propose to delve into how Elrick deals with this to see what insights and questions her book raises for scholarship on race and class in state classification practices. I discern two ways in which the relation between race and class is portrayed in Elrick’s account: first, class as a component of race; and second, class as intersecting with race. Let me discuss each of these conceptualizations in turn.

Class as a component of race

The cultural repertoire that Canadian immigration officials drew on in the 1950s and 1960s, so Elrick argues, contained a notion of race that consisted of two elements: biological racialism and class. Referencing Wallerstein (Citation1991), Elrick argues that racial classifications are “associated with higher/lower levels of development in the global economic and political context” (Citation2022, 77). As a result, Elrick writes:

Within the Canadian cultural repertoire, the idea of race, in relation to migrant admissibility, appears to have been a bifurcated one. In other words, it had two elements: the narrow biological meaning associated with ‘biological racialism’ and a meaning rooted in notions of social class and status. (Citation2022, 77)

In an effort to better understand Elrick’s argument, I visualize her bifurcated conception of race as having the same structure as DNA, that is a double helix consisting of two strands: perceived biological characteristics being the first strand and perceived class the second strand (see ). Elrick argues that the postwar shift from group-level to individual-level migration selection in Canada should not be understood as a shift from race to class, but rather as a shift in the relation between these two components of race. Whereas until the postwar era, biological racialism outweighed class, in the course of the 1950s and 1960s, the class component of race came to outweigh its biological component. Elrick refers to this process as a “recasting” of the notion of class, “whereby the relation between elements of a concept changes while the elements themselves remain the same” (Citation2022, 79). Thus, in my DNA metaphor, the double helix that is “race” remains unchanged, but the relative weight of the two strands is reversed: class becomes thicker, and biological racialism becomes thinner. Elrick argues that this recasting of race enabled Canadian immigration in the 1950s and 1960s to begin to consider individuals from non-European and therefore non-desirable origins admissible, as long as they were perceived to possess middle-class traits such as business-ownership or “prominence in the community” (Citation2022, 94).

This conception of race as consisting of class and biological racialism, with the relative weight of these two elements shifting through time, brings Elrick to argue that family migrants were racialized as a group in the 1950s and 1960s. In this period, while increasing non-European family migration also caused concern among immigration officials, it was Italian families in particular that came to be seen as “one of the most inadmissible immigrants groups in the 1950s”. Because they were of European origin, they were subjected to generous family migration policies which allowed admission not only of spouses and minor children but also of extended family members such as siblings and adult children, along with their spouses and dependents. These Italian family members, while racialized as White, were seen by immigration officials as “low quality”, “unskilled”, “uneducated”, “having no academic background” and even “untrainable”, “with little prospect, within their lifetime, of their being trained to undertake skilled employment in the labour force” (Citation2022, 137). Elrick emphasizes that such qualifications are not only about “their perceived economic utility”, but also about their “cultural, and moral worth” (Citation2022, 137). She concludes that “Spanning multiple origins, including visibly White (northern) Italians, family immigrants became negatively racialized as innately deficient in economic terms” (137). Indeed, Elrick argues that by the 1960s, the Japanese and the Italians had effectively “traded places” in the “moral hierarchy of immigrant groups”, so that the Japanese were deemed more desirable as new Canadians than Italians (Citation2022, 137). This was made possible, according to Elrick, by recasting the bifurcated idea of race:

In “recasting” this idea (privileging its class and status element over its biological one), immigration bureaucrats created a new racialized group – “the immigrant family” in general – which was seen as fundamentally inadmissible due to its low economic utility and socio-economic status. (Citation2022, 149)

My critical reading of this part of Elrick’s argument made me think back critically on my own previous work, notably the article on “Migrants with Poor Prospects”, which I wrote with Jan Willem Duyvendak. In this piece, which analyzed the representation of migrants in Dutch parliamentary debates about civic integration, we show that immigrants perceived as undesirable, generally referred to by the catch-phrase “migrants with poor prospects”, are represented not only as having low education and therefore low chances of finding work in the Netherlands, but also as having poor work ethos and oppressive gender norms. We noted that the categories of “Western” and “non-Western” migrants – commonly used until very recently in Dutch political and scholarly discourse – classify people as more or less “different” from “the Dutch” both in economic and cultural terms. Indeed, the government statistics agency categorizes people from Japan and Indonesia as “Western” based on their “socio-economic and socio-cultural position” (Netherlands Statistics Citation2022). This collusion of race and class in the hierarchical classification of peoples and countries is very similar to the perceived “higher/lower levels of development in the global economic and political context” which Elrick found to be crucial in racial classifications in the Canadian context. In conclusion of our “Migrants with Poor Prospects” article, Duyvendak and I argue that “class, intersecting with culture (…), is key in this process of [discursive] racialization” of certain migrants as “inadmissible” (Bonjour and Duyvendak Citation2018, 882). Just like Elrick, we conceptualized race as consisting of two strands: culture and class in our analysis; biological racialism and class in Elrick’s analysis.

In hindsight, I find this conceptualization of class as a component of the process of racialization no more satisfactory in our account than in Elrick’s. I think we did not push our conceptual thinking on this question hard enough at the time, because in the specific political discourses we observed, class and culture were assumed to be fully and inextricably connected: all “Western” people were assumed to be middle-class, and all “non-Western” people were assumed to be lower-class. Working class Dutch people were rendered wholly invisible in this discursive process. This is very similar to the pre-war discourses which Elrick observed among Canadian migration officials, where all European immigrants but no non-European immigrants were assumed to be middle-class. In contrast, Elrick studies a period in which this discursive connection between class and race begins to shift and loosen. This makes visible that in particular cases such as the problematization of family migrants discussed above, class eclipses race in the classificatory systems of migration officials. Conceptualizing class as a component of race does not allow for the possibility of class working as a social distinction in its own right. I believe we should conceptualize class and race as distinct but intrinsically connected social distinctions, and find ways to understand the nature of that connection. The concept of intersectionality, which Elrick also draws on, does exactly that.

Intersections of class and race

Intersectionality theory, as developed by Black feminist scholars like Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberley Crenshaw and bell hooks, to name but a few, states that the different social distinctions and systems of power that structure society should be seen as interacting with each other. Gender, race, and class do not operate in isolation, but as “reciprocally constructing phenomena” (Hill Collins Citation1995, 2). Elrick draws explicitly on this theory and consistently uses the language of intersectionality, for instance when she argues that migration officials strove to “manage racial diversity at the intersection of social class” (Citation2022, 9). Elrick moves back and forth throughout the book between talking about class as intersecting with race on the one hand, and about class as a component of race on the other hand. This is the one element in her otherwise crystal clear conceptual account which I found confusing, since logically, race cannot be simultaneously part of class and intersecting with class.

This one point of confusion notwithstanding, her intersectional analysis of the relation between class and race in the practices of migration bureaucrats is very convincing and insightful. Elrick shows that class mitigated or modulated the meaning of race in migration officials’ assessment of aspiring migrants. This allowed for individual Chinese applicants to be considered eligible because of their “steady employment”, “good prospects” or “prominence in the community”, even though Chinese immigrants as a group were considered undesirable immigrants (Citation2022, 91–96). In recruiting domestic workers from the British West Indies, Canadian bureaucrats also sought for “a higher class of girl” who would not stay in domestic service long but find another occupation that would allow her to be “a greater credit to herself, her race, and to Canada” (Citation2022, 111) Elrick also shows that, where migration officials were confident on applicants “fit” in Canadian society based on their middle-class status, they were willing to positively accommodate applicants’ perceived cultural specificities. For instance, childless Chinese couples were considered eligible to sponsor adopted children from China, since in “the Chinese view of family life, children are essential, and if a marriage does not produce offspring, adoption is the normal recourse” (Citation2022, 127). Admission of such cases was not automatic; however, they were to be judged on their “individual merits” – i.e. on class. Conversely, among the positively racialized group of European immigrants, certain individuals were deported from Canada if they failed to live up to middle-class standards, notably on grounds of criminal convictions, mental health issues, unemployment, or vagrancy (Citation2022, 96–103). Thus, Elrick shows that in the course of the 1950s and 1960s, an increasing number of individual applicants were either rejected or accepted in spite of their race. According to Elrick, it was the intersectional nature of the bureaucratic assessment that made possible this “decoupling [of] individual- and group-level admissibility” (Citation2022, 118).

The way Elrick operationalizes her intersectional conception of the relation between race and class, in my view, comes very close to Nira Yuval-Davis’ conception of intersectionality as constitutive rather than additive:

In any concrete reality, the intersecting oppressions are mutually constituted by each other. There is no meaning to the notion of ‘black’, for instance, which is not gendered and classed, no meaning for the notion of ‘woman’ which is not ethnocized and classed, etc. (Yuval-Davis Citation2007, 565)

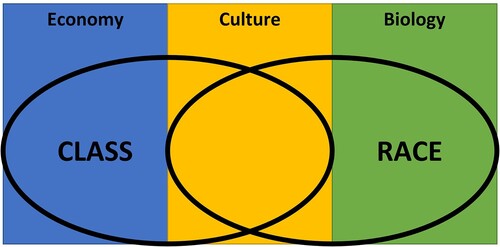

Another way of visualizing the nature of the intersectional nature of the relation between race and class which occurred to me while reading Elrick’s analysis is the image of two overlapping circles. It is quite common in intersectional accounts to think of categories as overlapping, but what is usually meant is that certain people fall into different categories at once, e.g. are both women and Black (Anthias Citation2012, 126). In Elrick’s account, the overlap between categories is of a different nature: there is overlap in the criteria for allocating individuals to the categories of class and race.

As noted above, Elrick conceptualizes class as consisting not only in perceived socio-economic traits but also in perceived cultural and moral traits. In a highly simplified version, one might say that in Elrick’s account, class is economy plus culture. Postcolonial and decolonial theorists like Aníbal Quijano have emphasized that the “idea of race” which formed the ideological underpinning of European conquest “was not meant to explain just the external or physiognomic differences between dominants and dominated, but also the mental and cultural differences” (Quijano Citation2000, 216; cf Stoler Citation2002). Thus in this account, “race” is “biology and culture” (ibid.). If class is economy plus culture, and race is biology plus culture, then “culture” may be thought of as the set of perceived traits or criteria where these two social distinctions overlap (see ).

The moral traits which Elrick observes bureaucrats as ascribing to applicants – integrity, ambition, trustworthiness, initiative and self-reliance – are part of both racial classification systems and class classification systems. Another example of this is family norms. Elrick observes that assessments of deservingness are often made at the level of families, where individuals found undesirable due to criminal records, poor (mental) health, or an irregular employment record may still be allowed to stay in Canada if migration officials deem their families willing and able to provide for their family member and keep them in line (Citation2022, 101–103). This norm that a “proper” family should support and discipline its own is a clear example of a norm that serves to classify people along lines of both race and class.

Thinking of the categories of race and class as overlapping in their cultural aspects raises the question of how to interpret what happens when the biological element of race disappears completely. If “origins” become irrelevant to migration classificatory practices, and only the cultural elements that are part of class assessments remain, shouldn’t we conclude that class has replaced race as a criterion for migrant selection? Elrick seems to tend towards that conclusion on different points, for instance, where she describes the “recasting of race” as “ultimately giving the Canadian nation-building project a class-based inflection” (Citation2022, 92), or as having “allowed immigration bureaucrats to admit individuals with appropriate class and status traits irrespective of their racial and national group memberships” (152). In such moments, Elrick’s conclusion do not seem so far away from the classic view that Canada moved from a race-based to a class-based immigration policy in the 1960s. However, Elrick’s overall argument explicitly rejects this view, for instance when she writes in her conclusion that “these adjudication practices did not eliminate race as a social distinction that influenced perceived admissibility; instead, they made the effect of race on admissibility contingent on other social distinctions, foremost class” (152). Thus, if my understanding of Elrick’s account is correct, the question of how exactly to understand the nature of the relation between class and race remains unresolved, raising fascinating questions to her readers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anthias, F. 2012. “Hierarchies of Social Location, Class and Intersectionality: Towards a Translocational Frame.” International Sociology 28 (1): 121–138. doi:10.1177/0268580912463155.

- Bonjour, S., and S. Chauvin. 2018. “Social Class, Migration Policy and Migrant Strategies: An Introduction.” International Migration 56 (4): 5–18. doi:10.1111/imig.12469.

- Bonjour, S., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2018. “The ‘Migrant with Poor Prospects’: Racialized Intersections of Class and Culture in Dutch Civic Integration Debates.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (5): 882–900. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1339897.

- Brubaker, R. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism.” Annual Review of Sociology 35 (1): 21–42. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916.

- Collins, P. H. 1995 (1991). “Black Women and Motherhood.” In Justice and Care, 117–136. New York: Routledge.

- Elrick, J. 2022. Making Middle-Class Multiculturalism: Immigration Bureaucrats and Policymaking in Postwar Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Hall, S. 2017 (1994). The Fateful Triangle. Race, Ethnicity, Nation. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press.

- Lamont, M. 1992. Money, Morals, and Manners: The Culture of the French and the American Upper-Middle Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Netherlands Statistics. 2022. Persoon met een westerse migratie-achtergrond. Accessed June 16, 2022. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/onze-diensten/methoden/begrippen/persoon-met-een-westerse-migratieachtergrond.

- Quijano, A. 2000. “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America.” International Sociology 15 (2): 215–232. doi:10.1177/0268580900015002005.

- Stoler, A. L. 2002. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power. Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. Berkeley etc.: University of California Press.

- Wallerstein, I. 1991. “World System Versus World-Systems: A Critique.” Critique of Anthropology 11 (2): 189–194. doi:10.1177/0308275X9101100207.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2007. “Intersectionality, Citizenship and Contemporary Politics of Belonging.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 10 (4): 561–574. doi:10.1080/13698230701660220.