ABSTRACT

Colour-blindness is a prominent concept across disciplines in the US but is less prominent and still an emerging and under-utilised conceptual tool in the European and Swedish context. Existing research measures colour-blind attitudes – defined as the belief that race does not matter. In this paper we examine what happens when we translate these US measurements and understandings of colour-blind attitudes to the Swedish context? We present the results from two quantitative studies conducted between 2009 and 2020 in Sweden. Based on these results, we discuss the possibilities, limitations, and implications of replicating the theoretical concepts from the US in the Swedish context and propose possibilities for measuring colour-blindness quantitatively. The paper thereby not only contributes to the theoretical and methodological discussion on understanding colour-blind attitudes in the European context but also highlights the prominence of colour-blind racial attitudes in Sweden.

Introduction

In recent decades, blatant forms of racial prejudice and discrimination have declined in many societal contexts, while new, subtle, forms continue to affect people’s life outcomes (Forman and Lewis Citation2015). Several theories were developed to capture these new subtle forms of racial prejudice, such as subtle racism and symbolic racism, but also colour-blind racism (Forman and Lewis Citation2006; Sears and Henry Citation2003). Colour-blindness as a concept emerged out of the US context as a new way to understand contemporary forms of racial prejudice after the civil rights movement in the 1960s preluded the eradication of Jim Crow and its segregation system, which resulted in the liberalisation of overt racial prejudice (Sears and Henry Citation2003). In general, conveying the idea that “race does not matter”, colour-blindness is understood by different scholars as a racial ideology, a form of racism, a strategy, a social attitude and a form of identity (Bonilla-Silva Citation2006; Neville et al. Citation2013; Penner and Dovidio Citation2016; Hartmann et al. Citation2017). This paper focuses on colour-blindness as a social attitude. Colour-blind attitudes are understood as a new and subtle form of racial bias and expressions of ways of thinking about race in society (Penner and Dovidio Citation2016).

Racial Colour-blindness is indeed a complex concept, rooted in the US context, which is gaining increased attention from European scholars (e.g. Bonnet Citation2014; Burdsey Citation2011; Jansen et al. Citation2016). Sweden constitutes a different context and has a different racial history, yet the concept of colour-blindness is also relevant to study in this setting to understand and detect the subtle yet complex forms of racial prejudice. Sweden as a country has developed based on the idea of a homogenous nation through the process of exclusion of different groups from the early nineteen hundreds onward (Broberg and Tydén Citation2005; Wickström Citation2015). This development in combination with the idea of equality for everybody living in the country forms the basis for a colour-blind discourse. While Sweden continuously demonstrates the most tolerant attitudes towards migrants in cross-country measures (Bell, Valenta, and Strabac Citation2021; Roots, Masso, and Ainsaar Citation2016); many studies show existing racial discrimination in the Swedish labour market, housing market but also when it comes to access to welfare services (e.g. Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Bursell Citation2012; Aldén, Hammarstedt, and Neuman Citation2015; Arai et al. Citation2016). In this context, to unpack the mechanism of colour evasion and rejection of racial categorization, two of the aspects crucial in understanding the relationship between colour-blind ideology and attitudes (Whitley, Luttrell, and Schultz Citation2022), is understanding how the structures of hierarchies and inequity are maintained. This argument is underlined by Voyer and Lund’s (Citation2020) contribution that demonstrates the analytical value of American racial reasoning for understanding social inequalities in Sweden.

Colour-blindness is understood by different scholars as on one hand a facilitator of prejudice, on the other an inhibitor of prejudice (Whitley, Luttrell, and Schultz Citation2022). Several scholars (Burke Citation2017; Doane Citation2017; Neville et al. Citation2000; Richeson and Nussbaum Citation2004) have put forward arguments about the importance of studying colour-blind attitudes for their influence on interpersonal relations and risk of decreased sensitivity to racism and discrimination, as well as the risk of being less attuned to minorities’ unique everyday lives. Scholars argue that some people might truly believe that colour-blind attitudes may be a remedy through which to end racism (Babbitt, Toosi, and Sommers Citation2016). However, in practice, colour-blind attitudes tend to be expressed more among people belonging to the majority society, and colour-blind ideology is strongly connected to the ideas of White privilege, White fragility, White innocence but also White habitus, the socialisation process that shapes Whites’ views on racial matters (DiAngelo Citation2018; Neville et al. Citation2000; Bonilla-Silva Citation2010). To link colour-blind attitudes to a variety of interpersonal settings and to understanding the effects of them, we need valid and context-adapted measurements of colour-blind attitudes.

Researchers within critical race and whiteness studies in Sweden identify how colour-blindness as an ideal has been established and practised in Swedish legislation and discourse (Osanami Törngren Citation2019; Hübinette and Lundström Citation2011). However, discussions around how to measure the magnitude of colour-blind attitudes are still lacking. This paper, with two separate empirical cases, address the theoretical and methodological questions of how to measure colour-blind attitudes – a measurement developed in the US context – can be utilised and translated to the case of Sweden, a country marked by immigration and racially visible minority groups but with an overall colour-blind logic where racial categorizations are rejected and referencing the word “race” is completely avoided. In Sweden, public and academic discussions focus on migrants as clumped “racialised subjects”, excluding White Swedes from the subject of racialisation. Specific languages addressing and recognizing the different contextual and historical effects of ethno-racial groups, including identifications as BIPOC, BAME, MENA/SWANA and White, as in the US or the UK, are almost completely absent in the Swedish context (except for the emerging identification and recognition of Afro-Swedes/Black Swedes as a group).

What happens when we translate US measurements of colour-blind attitudes to the Swedish context? How should colour-blind attitudes be understood and measured in Sweden? Our two empirical cases function as a starting point in understanding the implications of race and colour-conscious vs proxying terms when translating the Colour-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS; Neville et al. Citation2000); more specifically, how colour-blind attitude measures can potentially yield slightly different results measuring different nuances of colour-blind attitudes, depending on the usage of proxy terms of race. We argue for the need to examine further how the usage of the specific term “race” as “a technology of power and control” (Lentin Citation2020) together with proxy “colour-blind” terms may highlight the complex mechanism and magnitude of race and power evasion, to understand colour-blind attitudes and its effects in Sweden.

Migration and race in the universal welfare state

Sweden is defined as a universal welfare state that is guided by the principles of universalism and de-commodification. The main principle of the universal welfare state is a high standard of equality; however, of importance also is the characteristic of combining welfare and work to have as few people as possible being obliged to rely on social transfers (Esping-Anderson Citation2006). The Swedish welfare state developed after WWII with the aim of endorsing national cohesion and solidarity. To do so, the majority of the population needed to support the welfare state, and this was accomplished through the development of a feeling of belonging and the attachment of the national identity to the principles of the welfare state. This latter became an organic part of the national self-understanding, which was illustrated by the development of the vision of the Swedish people as a home, a sort of family, the so-called folkhemmet (Borevi Citation2012; Brochmann and Hagelund Citation2012).

This strong sense of solidarity with the welfare state is still one of the main characteristics of Sweden today. It is linked to a strong pride in equality for everybody living in the country. Sweden has become an immigration nation, with a focus on labour migration after WWII and a transition to mostly receiving refugees and their families from the 1970s onwards. The country’s integration policy is guided by the principle that immigrants have equal access to social systems (Borevi Citation2012). Several scholars refer to the “Swedish model” and “Swedish exceptionalism in understanding the organisation of the Swedish welfare state, including migration and gender policies and the country’s approach to racial matters” (Dahlstedt and Neergaard Citation2015; Gondouin Citation2012; Schierup and Ålund Citation2011). Part of Swedish exceptionalism is the Swedish progressive migration discourse that changed with the refugee crisis in 2015. A short period of increased numbers of asylum-seekers resulted in a shift from Sweden being one of the most welcoming countries to becoming a country with very limited immigration possibilities, especially for refugees. This has left political debates in Sweden polarised and questions the imagined Swedish values and its exceptionality (Emilsson Citation2018; Ericson Citation2018; Krzyżanowski Citation2018).

It is important to note that folkhemmet, the Swedish model and exceptionalism were all built and pursued with the idea of a homogenous Sweden through the process of exclusion (Broberg and Tydén Citation2005; Wickström Citation2015). As Sweden became a country with racial and ethnic diversity in a relatively short period of time through immigration, tensions in the system have inevitably increased. The change in the racial landscape of the country shifted significantly after 1980, when a larger proportion of immigrants from outside Europe entered the country. Today, 20 per cent of the total population of 10 million residing in Sweden were born outside Sweden. Around half of the foreign-born population have their background in Asia and Africa, with persons of MENA background being the largest (SCB Citation2021).

The idea of “Swedish exceptionalism” – with its sense of a strong welfare state and equality for all residents, including immigrants – flourishes. The pride in equality is linked to a strong sense of colour-blind discourse as the “right thing” to do. This belief is linked to the aftermath of WWII and is common in most European countries. The Holocaust was, as such, a defining event, standing for horrific racial proclamations and therefore race has no space in “any characterizing of human conditions” (Goldberg Citation2009, 154). Based on this denial of race and its strong sense of equality, Sweden, like other European countries, developed a colour-blind discourse. However, studies in Sweden in the past ten years have critically found that this de jure equality does not lead to de facto equality. The population of Sweden is often dichotomised as “immigrants” and Swedes based on phenotype and whiteness (Hübinette and Lundström Citation2011; Mattsson Citation2005; Runfors Citation2006, Citation2016). As Goldberg (Citation2015) argues, there is a common belief in the post-racial. This means that society that holds strong to its belief in the non-racial and race is not at its disposal; however, the principles developed in its name keep on operating but under new, invented, terms. For example, since 2014, the Swedish government removed the word “race” from all existing legislation in Sweden (Hambraeus Citation2014) with a few exceptions where the word race still appears in a some instances (such as in the definition of racism) when it is deemed “necessary”. Consequently, colour-blindness in Sweden means that it can be difficult for many people to even “utter the word “race” in everyday speech, and it is equally uncomfortable to talk about white and non-white Swedes’ (Hübinette and Hylten-Cavallius Citation2014, 30). This means that, in Sweden and in academia, other terms are used as a placeholder when talking about race. The terms “ethnicity” and “culture” are often used to refer to race; equally, when referring to whiteness one often refers to nativity (Swedish) instead (Osanami Törngren and Suyemoto Citation2022).

Understanding colour-blindness

Our starting point is that race is an automatically activated social category based on what is perceived to be visible (Penner and Dovidio Citation2016). This categorisation of race functions as a mechanism to create hierarchies in society and affects individuals’ lives through their experiences of (or not experiencing) racism, racialisation and discrimination. In short, race matters not because of its visibility, which can be falsely categorized, but because of the inequity that exists in the institutional and structural levels of society (Osanami Törngren and Suyemoto Citation2022).

Within the US context, colour-blindness is described as “the belief that race should not and does not matter” and diminishes the significance of racial group membership, the belief that race does not influence life outcomes (Daughtry et al. Citation2020; Plaut et al. Citation2018). There are also scholars who emphasise that certain people might believe that colour-blindness is the way to achieve racial harmony (Babbitt, Toosi, and Sommers Citation2016). In this article we understand colour-blindness as an ideology – a belief that race no longer matters (Doane Citation2017) and “a set of race-neutral ideals, views and norms with which people identify” (Hartmann et al. Citation2017, 868). It is a belief that is based on individualism and liberalism that individual efforts and choices are more important than race in determining socio-economic outcomes. Because empirical evidence in the US, where colour-blindness is theoretically developed, shows that race continues to matter not only for individual lives but also in institutional and structural arrangements, scholars argue that colour-blind ideology is a practice which only maintains and benefits those in power and those who belong to the majority (Goldberg Citation2015; Lentin Citation2020). Scholars as Neville et al. (Citation2013) and Bonilla-Silva (Citation2006) specifically identify colour-blindness as a racially explicit attitude and a form of racism aimed at conveying race as something that belongs to the past and is of no importance for personal and professional interactions, seen as a continuation of negative attitudes and bias towards minorities. Others suggest that it is used as both a strategy to appear unbiased and not racist and also as a “moral buffer” against having to deal with racial inequality and the role of white privilege (Lewis Citation2001; Penner and Dovidio Citation2016). In sum, these ways of understanding colour-blindness in the US context address colour-blindness as an ideological package that blinds and makes invisible a sense of Whiteness and privilege (Hartmann et al. Citation2017). European scholars tend to approach the concept through the idea of equality and power evasion. Bonnet (Citation2014) links colour-blindness to the performance of non-racism – i.e. not wanting to appear racist. Jansen et al. (Citation2016) relate colour-blindness to being treated equally in organisations, while Hachfeld et al. (Citation2015) define it as “treating all people equally, regardless of their background” (Citation2015, 46). They apply the concept to the teaching context and further develop the notion that colour-blindness is about “downplaying cultural differences” to highlight similarities between students of “different cultural backgrounds” (Citation2015, 46).

Measuring colour-blind attitudes

Colour-blindness as ideology has been examined both qualitatively and quantitatively. Some of the more influential qualitative works are Schofield’s (Citation1986) examination of racial attitudes in desegregated schools, Frankenburg’s (Citation1993) work on white women and Bonilla-Silva’s (Citation2006) examination of storytelling and racial speech by the white majority. Frankenburg proposes two terms for understanding colour-blind racial attitudes among the white women whom she interviewed: colour evasion and power evasion. Colour evasion emphasises “sameness” to reject the idea of white privilege, while power evasion is a mechanism of “blaming the victim” because of the underlying notion of colour evasion. Both are driven from the belief that everyone has the same opportunities to succeed, therefore “any failure not to achieve is therefore the fault of people of colour themselves” (Frankenburg Citation1993, 144). Bonilla-Silva categorised different expressions of colour-blind talk. The categories of colour-blind discourse which he proposes resonate with the notions of colour and power evasion that Frankenburg suggests. In Bonilla-Silva’s argument, focusing on individuals instead of groups or structures is one of the ways in which colour-blind racial attitudes are effectively incorporated into an explanation for existing racial inequality. Individuals are seen as having choices, therefore racial incidents can be explained as natural occurrences. Moreover, instead of addressing racism and discrimination as factors affecting individuals’ life chances, the idea of “cultural differences” is deployed in arguing why social and economic inequality persists (Bonilla-Silva Citation2010, 28–29).

Neville et al.’s (Citation2000) work on colour-blind racial attitude scales is one of the most prominent quantitative measurements of colour-blind attitudes. Neville et al. (Citation2000) developed a scale (CoBRAS) influenced by Frankenburg’s (Citation1993) concepts of colour and power evasion, containing 20 statements which refer to three aspects of how colour-blind racial attitudes are expressed: awareness of institutional racism, awareness of blatant racial issues and awareness of racial privilege. In developing the scale, they were very clear on the point that colour-blind racial attitudes refer to the “denial of racial dynamics” and, therefore, that colour-blind attitudes are expressions of an unawareness of the existence of racism and not necessarily the reflection of a belief in racial superiority.

Both qualitative and quantitative examinations of how colour-blind ideology functions have started to gain traction but are still under-explored in Scandinavia and in Europe in general. Existing studies (Simon Citation2010, Citation2017; Ware Citation2015) in the European context investigate models of public policy in France that show the propensity of colour-blind ideology in both policies and laws that assess racial and ethnic discrimination, together with the avoidance of implementing race-conscious policies. Safi (Citation2017) examined French employment diversity programmes highlighting a colour-blind ideology on the institutional cultural level where the supposedly “more-legitimate categories of inequality” such as “visible minorities” is used instead of ethno-racial features in promoting diversity. Bonnet’s (Citation2014) qualitative study shows that French security personnel are performing non-racism driven by colour-blindness by focusing on the individuals, which is in fact rooted in race-consciousness. How colour-blind ideology is reflected as a discourse, i.e. “talking colour-blind”, is also shown in a qualitative interview study by Raúl and Šotala (Citation2018) about Czech seniors’ attitudes towards foreigners. Another qualitative study in the Swedish context (Osanami Törngren Citation2019) looks at how colour-blind discourses are deployed in explaining negative attitudes towards interracial marriages, making the argument sound reasonable and rational rather than prejudiced.

Existing quantitative measurement of colour-blind attitudes in Europe

There are only a few studies in the European context that have measured colour-blind attitudes. Wolgast and Nourali Wolgast (Citation2021), in their study on White privileges and discrimination in Sweden used a translated version of CoBRAS by Neville, using words such as “White”, “skin colour” and “ethnicity”. White respondents have, on average, showed higher scores than non-white respondents, and higher levels of colour-blind racism covaries with higher levels of belief that success – both in society and in one's own organization – is determined by individual qualities such as ambition, hard work and competence (Wolgast and Nourali Wolgast Citation2021). This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the only study that translated CoBRAS in a European context.

However, there exist other studies that have measured colour-blind attitudes, but these studies did not make use of the CoBRAS to operationalize colour-blindness. Jansen et al. (Citation2016) studied colour-blindness in Dutch organisations and its effect on employees’ work satisfaction. Only majority-group employees reporting colour-blind attitudes also reported having increased satisfaction. Minority-group employees showed no increase in satisfaction while reporting colour-blind attitudes. Jansen et al. (Citation2016) measured colour-blindness using the “diversity perspective questionnaire”. Four statements were used to measure it: “(a) People fit into our organisation when they match the required job qualifications; (b) Qualification matters in our organisation, not background; (c) Promotion is dependent upon employee performance, not upon a person’s background; (d) Everybody is welcome as long as they meet the necessary requirements” (13). Overall, skin colour and ethnicity are suggested by “background”. Reference to racial categories are missing in this measurement. Similarly, Hübinette and Lundström (Citation2011) examined Dutch leaders within the university and their diversity perspective in relation to colour-blind attitudes opposed to multiculturalism. The results show that colour-blind attitudes among leaders are related to minority group members distancing themselves from the work group. Meeussen et al. (2014) measured colour-blindness with two indicators: (a) I thought it was better not to pay attention to cultural backgrounds during this collaboration; (b) in my view all group members should behave in the same way that is customary in our university. Similarly, to Jansen et al.’s (Citation2016) measurement, skin colour and ethnicity are suggested by the term “background” but also “group member”. In another study, Hachfeld et al. (Citation2015) studied colour-blindness among German teachers, with a focus on different aspects of professional competence when teaching immigrant students. Colour-blind beliefs were negatively related to adapting teaching to culturally diverse students. The authors measured colour-blindness using the “Teachers Cultural Beliefs Scale” (Hachfeld et al. Citation2011), with four items: “(a) Schools should aim to foster and support the similarities between students from different cultural backgrounds, (b) In the classroom, it is important that students of different origins recognise the similarities that exist between them, (c) When there are conflicts between students of different origins, they should be encouraged to resolve the argument by finding common ground, (d) Children should learn that people of different cultural origins often have a lot in common” (988). Overall, as in the above-mentioned studies, these measurements make no direct reference to racial categories. Hachfeld et al. (Citation2015) make use of “cultural background” and “different origins” to refer to skin colour and ethnicity.

Most of the above-mentioned studies in Europe measure colour-blind attitudes while using no direct racial categories. Moreover, these studies lack discussions about how the country context might shape the choice of terms in measurements and how that choice might influence the empirical outcome. However, what some of these studies have in common are their convergent results to the US literature (Bonilla-Silva Citation2006; Neville et al. Citation2013), showing that colour-blind attitudes are related to holding racial prejudice (Hachfeld et al. Citation2015). This finding indicates that despite differences in setting and operationalization, colour-blind attitudes in the European context “function” in a similar way as in the US context, especially in terms of power evasion through focusing on equality.

Measuring colour-blind attitudes: two different cases

What happens when we try to understand the impact of colour-blind attitudes in Sweden through a scale developed in the US? We present the results from our two separate projects, one on attitudes among welfare bureaucrats and the other on perceptions of the Swedishness of different faces, which tried to measure colour-blindness quantitatively. These studies were conducted at different time periods and unintentionally used different translations of CoBRAS, which gave us the opportunity to explore how CoBRAS can yield slightly different results depending on the choice of words used in translating – race-conscious or colour-blind proxy terms. CoBRAS has its focus on the impact of power evasion and ideal towards equality, which is suitable in understanding colour-blind racial attitudes in European contexts, as pointed out above.

Colour-blind attitudes among welfare professionals (Dataset 1)

To study the colour-blind attitudes of welfare professionals, survey data was collected from Swedish welfare professionals working in two of the main welfare organisations in the country – the Public Employment Services (PES) and the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA). The PES and the SSIA both offer aid to the entire Swedish population. The PES has the general mandate to aid the unemployed. The SSIA provides financial security at various life stages for everyone who lives and/or works in Sweden. This includes benefits and allowances for families with children, people who are ill and people with disabilities (Mathias Citation2017; SSIA Citation2017). The two organisations had about 14,000 employees at the time of the data collection (2016), with offices throughout the country; about half of the workers were members of a union that served as the sampling frame for the study (Kalton Citation1983). Of the 6,650 respondents, 1,617 answered the survey, giving a final working sample of N = 1,319. The measurement of colour-blindness was adapted from the “‘Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale” or CoBRAS, which was developed by Neville et al. (Citation2000). The wording in the measurement items was adapted to the Swedish context by replacing “Whites” with “Swedes” and “race” with “ethnic background”. The latent variable is composed of three items (listed in in the Appendix). The response options ranged from fully disagree to fully agree and all items were reverse coded so that they were all in the same direction (1 = less colour-blind; 4 = more colour-blind). The study was approved by the regional ethical board in Lund, Sweden.

Colour-blind attitudes among students (Dataset 2)

The material we analyse in this article was collected as part of the experiment examining perceptions of Sweden and Swedishness through tourism adverts and facial images. The study was conducted in September 2020. A total of 40 respondents (of whom 29 females) with an average age of 25.5 years participated in the study. All respondents were enrolled in educational programmes at college/university level at the time of the study. What is of interest in this paper is the survey result, where we incorporate the fully translated version of Neville et al.’s CoBRAS 20-items scale. The word “race” was replaced by the official Swedish proxy term rasifierad (racialised). Based on the parental country of origin reported, 23 respondents were mono-ethnic Swedes (having two parents born in Sweden) and 4 were mixed Swedes (having one parent born in Sweden and one born abroad). Twelve respondents were mono-ethnic non-Swedes, and one was mixed non-Swedish (having two parents born in two different countries outside Sweden). In the analysis, three respondents who were born outside Sweden and migrated there after the age of 13 were eliminated, making it a total of 37 respondents. The study was approved by the central ethical board in Sweden.

Limitations

Before turning to the analysis of our data, we would like to point out the limitations of comparing two different datasets. In this paper we are deriving conceptions based on the descriptive statistics of two datasets, both of which are very different in nature. Dataset 1 was a representative online survey aimed at welfare professionals, meaning the population represented a specific group (professionals working in Swedish welfare institutions). This dataset had a sample of 1,319 respondents. The survey was conducted in 2016. Dataset 2, however, was not representative and was the result of an experiment. Participants filled in the survey, aimed at students, then and there; this meant that the population was composed of students at Malmö University and was much smaller – 40 respondents. The survey was conducted in 2020.

Overall, our datasets consisted of two very different samples, which differed according to the kind of population targeted – welfare professionals vs students. Having two different respondent groups can lead to a variety of outcomes. Welfare professionals might have additional factors that influence the way they reason about racial attitude questions – for example the professional value of treating all clients equally, which might express itself in increased social desirability that might influence the results. Also, welfare professionals are, on average, older than students. If we wanted to derive comparable results, more data would be needed. We are fully aware that the two samples are not comparable, so we cannot derive meaning from comparing the numerical outcomes. Instead, we are using the descriptive statistics of the two different samples to derive conceptual and methodological suggestions and to serve as a starting point in examining how colour-blindness can be measured quantitatively in Sweden. Moreover, our focus is not to validate or examine the quantitative effects of different translations of the scales, but we suggest what kind of implications the wording choices may have, and which should be further investigated.

Different ways of measuring colour-blind attitudes: what can we learn from them?

Items from CoBRAS that were used in both datasets were measurements of power evasion within the factor capturing awareness of racial privilege. Power evasion is the idea that “everyone has the same opportunity to succeed” (Neville et al. Citation2000, 60). The following three items were used in both datasets and were, in their original formulation, as follows:

White people in the US have certain advantages because of the colour of their skin.

Racial and ethnic minorities do not have the same opportunities as the majority people in my country.

Everyone who works hard, no matter what skin colour they have, has an equal chance to become successful.

The authors translated the items into Swedish in their respective studies but did so in different ways. The exact wordings can be seen in in the Appendix.

As a first step, we conducted a factor analysis for each dataset respectively for each of the three items to ensure that they correlate between each other and reflect the underlying dimension of colour-blind attitudes. For Dataset 1, the factor analysis of the three items resulted in one factor with an eigenvalue of 1.9, which explained 68 per cent of the variance in the three items. For Dataset 2, the factor analysis of the three items resulted in one factor with an eigenvalue of 1.9 which explained 66 per cent of the variance. This outcome indicates that colour-blindness as a form of power evasion could be measured in both cases – in Dataset 1, which does not specifically use racial categories and in Dataset 2, which used the wording of the original scale that refers directly to racial categories, such as whiteness. This could be an indication that we can measure power evasion even without specifically mentioning concepts such as race or whiteness. However, because the one uses specific racial language and the other, instead, proxies race to ethnicity or nativity, we have to ensure that we are measuring different mechanisms of power evasion, which will be further discussed through the second step of the analysis.

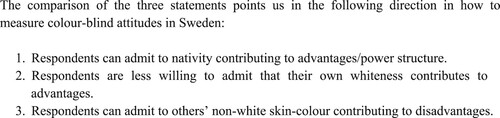

In this second step, we compared the differences in how the three items were worded in Swedish. For both datasets we made a univariate analysis in the form of a frequency table to compare answers. The combined answers to the options “Agree” and “Fully agree” presented as “Agree”, are illustrated in and documented in in the Appendix. We also transformed the three items into a scale with a mean of 2.3 for Dataset 1 and a mean of 2.7 for Dataset 2. The scale ranges from 1 to 4 and the higher the number in the index, the more “colour-blind” attitudes the respondent reports. As the respondents from Dataset 2 were students, we see a higher score on the index, meaning a higher “colour-blind response” than the bureaucrats in Dataset 1.

The language in Dataset 1 does not explicitly refer to race. “White people” is translated as “Swedish people”, presupposing that respondents would imagine a white person when using the term “Swedish”. Dataset 2 used the exact term “white people”. “Skin colour” was translated into “ethnicity” in Dataset 1 whereas Dataset 2 used “skin colour”. Moreover, in Dataset 1, ethnic and racial minorities were translated as “immigrants” whereas Dataset 2 used “racialised and ethnic minorities”. With the limitations and differing nature of our respondents in mind, there are interesting patterns that we observe here. The first statement in Data 1’s formulation shows that the respondents were aware of the privileges attached to being “Swedish” compared to having a different ethnic background. However, in Dataset 2’s formulation, specifically addressed at reflections on whiteness and skin colour, we see that more respondents deny that whiteness and the colour of the skin give advantages in Swedish society. This suggests that different respondents can admit to “Swedishness” being an advantage but that there might be a larger reluctance to admit that the colour of the skin is giving individuals’ advantages.

In the second statement, the translation in Dataset 1 more closely measures how nativity drives inequality through the dichotomisation of the words “immigrants” and “Swedish”, while the translation in Dataset 2 specifically addresses how people’s racial and ethnic backgrounds drive inequality. Among the sample in Dataset 1, there is a high awareness that being an immigrant – i.e. not being a native of the country – generates disadvantages compared to being Swedish. Here we do not know how the respondents actually interpreted the words “immigrant” and “Swedish”. We are aware that, in colloquial usage, second-generation immigrants are included in the category “immigrant”, especially when the person is non-white (Lundström Citation2021; Trondman Citation2006). 70 per cent of our respondents do believe that immigrants do not have the same opportunities as native Swedes, despite Swedish society guaranteeing rights for all residents (defined as those who have lived in the country for more than 13 months) independent of their citizenship or country of birth. This overwhelming awareness seems to be less clear when the question is targeted specifically towards racialised and ethnic minorities in relation to the majority society. Most of the respondents in Dataset 2 disagreed with the statement, which again shows that there might be an evasion of power based on the idea of race and ethnicity.

Bearing the above points in mind – that respondents show a clear pattern of power evasion when the questions are specifically targeted at addressing the whiteness and privilege of the majority society, the differences we see in the results on the formulation of the third question are interesting. In Dataset 1 the formulation centres around the idea of ethnic differences, which are considered to be more cultural and invisible, while Dataset 2’s formulation again specifically addresses the colour of the skin. The majority of respondents in Dataset 1 did agree that ethnic differences have no influence on how successful a person can be, therefore it is a form of expression of power evasion based on ethnic differences. On the other hand, the majority of respondents in Dataset 2 disagreed with the statement, indirectly admitting that doing one’s best individually is not enough to be successful in Swedish society and that skin colour does matter. This result might sound contradictory considering that more than 40 per cent of the respondents previously said that being racialised or having an ethnic background does not always lead to a disadvantaged position compared to the majority society. However, the results given in answer to this third statement specifically suggest how much power evasion, based on the idea of race and skin colour, underlies in the Swedish context. The third statement does not specifically spell out who the comparison is with – in other words, whiteness or the racial majority is absent. The respondents may thus to a larger extent admit to the fact that individual efforts do not lead to the same likelihood of success, depending on the skin colour.

Point 2 shows colour evasion as a form of power evasion, suggesting “white fragility”, “white innocence” or “white habitus” in admitting that their own Whiteness leads to privileges (DiAngelo Citation2018; Bonilla-Silva Citation2010), while Point 3 shows, even though it seems contradictory, colour consciousness that non-White persons may face disadvantages because of their skin-colour. Points 2 and 3 seen together clearly indicate that there is a mechanism of colour-blind ideology in Sweden, where White racial privilege is evaded.

Our interpretation of the empirical results is driven by the theoretical framing of the paper, but we also acknowledge that there are alternative interpretations of the data (Kuckartz Citation2019). First, welfare professionals are older compared to the student sample and they might therefore be more fostered into a less critical idea of an “equal Sweden” than younger people, who make up the respondents in the second data set. Therefore, the difference in responses might be rather due to the difference between the respondents in the data sets and not the choice of wording. Second, welfare workers represent a professional group that is in their daily work supposed to make equal decisions, independent of whom they meet. This professional value of equality when it comes to client treatment might have also influenced how they are answering the survey questions about colour-blindness. While acknowledging possible alternative interpretations of the data we want to emphasise our understanding of the data, that different wordings reflecting racial terms or proxy-terms for race can indicate different meanings and the meaning of different words can also be context dependent. Sweden’s overall discourse of rejecting race while strongly promoting equality could be a context specific factor influencing how measurements using racial categories versus measurements using proxy terms are answered towards.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was, through two distinct empirical cases, to address how CoBRAS, a measurement of colour-blind attitudes developed in the US can be conceptualised in the Nordic context. The US context, where the CoBRAS was developed, has a long-standing focus and history on colour and the race-conscious approach (Neville et al. Citation2000). This race conscious approach entails attention to processes of inequality that “operate through categories of racial and ethnic differences” (Voyer and Lund Citation2020, 337). In the Swedish context, race as a concept is often avoided, while other socially constructed categories such as ethnicity and culture are more commonly used as proxies of colour and race. In other words, the Swedish context itself presents a discourse of egalitarian individualism, colour-blindness and what Goldberg (Citation2015) calls “anti-racialism”, a simple avoidance of the word race itself (Voyer and Lund Citation2020). The tension of anti-racialism and understanding colour-blind ideology itself becomes obvious in the practices of other researchers who measure colour-blindness quantitatively in the broader European context. As introduced earlier, we can see that both Jansen et al. (Citation2016) and Hachfeld et al. (Citation2015) make use of more-legitimate categories such as “background” and “group membership” to refer to ethno-racial features.

Our paper challenges making use of racial proxy terms to measure colour-blindness in Europe and casts a unique perspective in understanding how colour-blind attitude measurement developed in the US that is making use of racially aware categories can be utilised in the Swedish and broader European contexts. Similar to the argument of Voyer and Lund (Citation2020), we propose that “American racial reasoning” can be a helpful tool to study and detect social inequality that is operating through categories of racial differences. Even though colour-blindness as a concept emerged out of a US specific context to understand new subtle forms of racial prejudice, Sweden is a country with a (different) history of racial exclusion as well and colour-blindness as a concept adds analytical value to uncover persisting social inequality (Catomeris Citation2017; Voyer and Lund Citation2020). Especially CoBRAS which focuses on the aspects of colour and power evasion is suitable in understanding colour-blind attitudes in Europe, embedded in ideals of equality and liberalism.

Specifically, our results focus on colour and power through items concerning awareness of racial privileges, the denial that racial inequality exists (Shih and Young Citation2016). The factor analysis shows that three items can be used in the Swedish context to measure power evasion with a focus on inquiries about equal opportunities in society. Meaning, understanding colour-blindness as a form of power evasion identified through the CoBRAS is transferable from the US to the Swedish context. We propose that to understand the complexity of the impact of colour-blind attitudes in Europe and Sweden, we need to tease out this tension between the simple avoidance of the word race itself and the colour-blind ideology itself. Our two empirical findings suggest that proxying race to normative categories like “background” or “ethnicity” needs to be deployed together with specific references to be supplemented by actually referring to race, Whiteness and colour when measuring colour-blind attitudes, because they may provoke different responses and mechanisms of power evasions as suggested in our empirical findings and further elaborated on in the following section. These non-racial proxy terms for ethno-racial markers can be nativity – i.e. “Swedishness” and “immigrantness”, as one of our dataset have operationalised – but they can also include religion, language, accent or nationality, as other European scholars have posited (e.g. Safi Citation2017). Through combining the specific language of race and its proxy terms, we might be able to precisely identify where race and colour evasion, the denial of the existence of racial differences and power evasion, the denial of the existence of racial inequality, intersect. We propose that these are not mutually exclusive but, rather, might be a necessary language of inquiry to understand the mechanism of power evasion in the Swedish context. This paper does not examine the quantitative effects of different wording in measuring colour-blind attitudes, but it suggests the implications different wording choices may have on how people answer to measurements of colour-blind attitudes. These suggested implications should be seen as a first step in addressing and capturing the complexity of colour-blind ideology in the Nordic context. One could argue that colour-blindness in the US context is about that race does exist but should not matter but in the Swedish context race is not acknowledged to exist and therefore rejected. Therefore, one could think that the way colour-blindness is measured in the US context is an ill fit for the Swedish one. However, the denial and rejections of racial categorization, “de-emphasizing group membership” (Rosenthal and Levy Citation2010, 216) itself in the Swedish and European context, do reflect one of the important aspects of colour-blindness norms and attitudes. Moreover, previous studies from the European context show converging results with studies from the US context with colour-blind attitudes being associated with increased racial prejudice (Hachfeld et al. Citation2015). This points towards similar mechanisms of exclusion in these two contexts and that racial structures not only apply to the US context but also beyond. It is argued that contexts with different histories of exclusion nevertheless have similar mechanisms of exclusion in relation to categories of racial differences and therefore we should make use of racially aware measurement tools, so that we can move beyond racialized categories such as “immigrant” to capture the nuances of social inequality in the Nordic context (Voyer and Lund Citation2020).

To do so, what needs to be further examined and tested from our discussion here based on two separate data is how questions are asked in a non-racial or a colour-conscious way may leave respondents with more or less willingness in admitting to the White and majority racial privileges. We suggest that the argument of the paper should be treated as a theoretical and methodological starting point and should be empirically tested more systematically. For example, a future study could compare measurements using proxy terms and race-/colour-conscious terms that are aimed at the same sample to have comparable outcomes for the two different wording terms used in the items to measure the propensity of colour-blind attitudes.

Research is called for to unpack colour-blind ideology in Sweden and in Europe as we are observing the polarisation of attitudes and increasing inequality. On the one hand, there is increased endorsement of right-wing and extremist movements and, on the other, people are expressing less explicitly racist attitudes. Developing a measurement of colour-blind attitudes for the Swedish context is important, on the one hand, to be able to make use of valid measurements and, on the other, to be able to relate these colour-blind attitudes to other social phenomena such as intergroup relations and interpersonal behaviour. Research in the US contexts shows how colour-blind attitudes can have a negative influence when it comes to micro- and meso-level interactions. They might do more harm by downplaying race and it might even result in reciprocal effects that are ill-serving for those in need (Wise Citation2010). Previous research shows that implicit bias in, for example, healthcare can result in unequal care; promoting colour-blind attitudes would contribute to leaving these disparities undetected and undiscussed, resulting only in the replication of discriminatory practices (Penner and Dovidio Citation2016). A similar logic applies to the educational sector. Teachers who downplay race and serve a diverse student body will have a lesser commitment to adapting their curriculum and teaching for multiple voices (Hachfeld et al. Citation2015; Wise Citation2010). Moreover, colour-blind attitudes in organisations – through ignoring differences in race, culture and ethnicity – can lead to undetected biased treatment and racial microaggressions that are downplayed. They can also result in the increased emotional labour of minority groups with outcomes of lower job satisfaction and increased levels of stress and burnouts (Humphrey Citation2021; Jansen et al. Citation2016; Shih and Young Citation2016). Previous research also points that it is possible that colour-blindness as a subjective form of identification, can have positive effects on race relations (Hartmann et al. Citation2017). By drawing on these examples, we want to emphasise the importance of having relevant and effective ways to understand the functions and complexity of colour-blind attitudes in Sweden to detect institutional and practices that might result in racial inequity due to a simple denial and downplaying of race and White privileges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, A. M., and M. Hammarstedt. 2008. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Internet.” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2): 362–372.

- Aldén, L., M. Hammarstedt, and E. Neuman. 2015. “Ethnic Segregation, Tipping Behavior, and Native Residential Mobility.” International Migration Review 49 (1): 36–69.

- Arai, M., M. Gartell, M. Rödin, and G. Özcan. 2016. Stereotypes of Physical Appearance and Labor Market Chances. WORKING PAPER 2016:20. http://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2016/wp2016-20-stereotypes-ofphysical-appearance-and-labor-market-chances.pdf.

- Babbitt, L. G., N. R. Toosi, and S. R. Sommers. 2016. “A Broad and Insidious Appeal: Unpacking the Reasons for Endorsing Racial Color Blindness.” In The Myth of Racial Color Blindness: Manifestations, Dynamics, and Impact, edited by H. A. Neville, M. E. Gallardo, and D. W. Sue, 53–68. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bell, D. A., M. Valenta, and Z. Strabac. 2021. “A Comparative Analysis of Changes in Anti-Immigrant and Anti-Muslim Attitudes in Europe: 1990–2017.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–24.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2006. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 2nd ed. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2010. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 4th ed. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bonnet, F. 2014. “How to Perform non-Racism? Colour-Blind Speech Norms and Race-Conscious Policies among French Security Personnel.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (8): 1275–1294.

- Borevi, K. 2012. “Sweden: The Flagship of Multiculturalism.” In Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State 1945–2010, edited by G. Brochmann, and A. Hagelund, 25–96. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Broberg, G., and M. Tydén. 2005. Oönskade i folkhemmet. Svensk steriliseringspolitik. Stockholm: Dialogos Förlag.

- Brochmann, G., and A. Hagelund, eds. 2012. Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State 1945–2010. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burdsey, D. 2011. “That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore: Racial Microaggressions, Color-Blind Ideology and the Mitigation of Racism in English Men’s First-Class Cricket.” Sociology of Sport Journal 28 (3): 261–283.

- Burke, M. A. 2017. “Colorblind Racism: Identities, Ideologies, and Shifting Subjectivities.” Sociological Perspectives 60 (5): 857–865.

- Bursell, M. 2012. “Ethnic Discrimination, Name Change and Labor Market Inequality: Mixed Approaches to Ethnic Exclusion in Sweden.” In Stockholm Studies in Sociology: N.S., 54. Accessed February 7, 2022 http://ludwig.lub.lu.se/login?url = http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct = true&db = cat01310a&AN = lovisa.002522556&site = eds-live&scope = site.

- Catomeris, C. 2017. Det ohyggliga arvet : Sverige och främlingen genom tiderna (Andra utök). Stockholm: Ordfront.

- Dahlstedt, M., and A. Neergaard. 2015. “Introduction: International Migration and Ethnic Relations: Critical Perspectives.” In International Migration and Ethnic Relations: Critical Perspectives, edited by M. Dahlstedt, and A. Neergaard, 1–12. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Daughtry, K. A., V. Earnshaw, R. Palkovitz, and B. Trask. 2020. “You Blind? What, you Can’t see That? The Impact of Colorblind Attitude on Young Adults’ Activist Behavior Against Racial Injustice and Racism in the US.” Journal of African American Studies 24 (1): 1–22.

- DiAngelo, R. 2018. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston MA: Beacon Press.

- Doane, A. 2017. “Beyond Color-Blindness:(Re) Theorizing Racial Ideology.” Sociological Perspectives 60 (5): 975–991.

- Emilsson, H. 2018. “Continuity or Change? The Refugee Crisis and the End of Swedish Exceptionalism.” Accessed February 7, 2022 www.bit.mah.se/muep.

- Ericson, M. 2018. “‘Sweden has Been Naïve’: Nationalism, Protectionism and Securitisation in Response to the Refugee Crisis of 2015.” Social Inclusion 6 (4): 95–102.

- Esping-Anderson, G. 2006. “Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism.” In The Welfare State Reader, edited by C. Pierson, and F. G. Castles, 160–174. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Forman, T. A., and A. E. Lewis. 2006. “RACIAL APATHY AND HURRICANE KATRINA: The Social Anatomy of Prejudice in the Post-Civil Rights Era.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 3 (1): 175–202.

- Forman, T. A., and A. E. Lewis. 2015. “Beyond Prejudice? Young Whites’ Racial Attitudes in Post–Civil Rights America, 1976 to 2000.” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (11): 1394–1428.

- Frankenburg, R. 1993. White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Goldberg, D. T. 2009. The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Goldberg, D. T. 2015. Are We All Postracial Yet? Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gondouin, J. 2012. “Adoption, Surrogacy and Swedish Exceptionalism.” Critical Race and Whiteness Studies 8 (2): 1–20.

- Hachfeld, A., A. Hahn, S. Schroeder, Y. Anders, and M. Kunter. 2015. “Should Teachers be Colorblind? How Multicultural and Egalitarian Beliefs Differentially Relate to Aspects of Teachers’ Professional Competence for Teaching in Diverse Classrooms.” Teaching and Teacher Education 48: 44–55.

- Hachfeld, A., A. Hahn, S. Schroeder, Y. Anders, P. Stanat, and M. Kunter. 2011. “Assessing Teachers’ Multicultural and Egalitarian Beliefs: The Teacher Cultural Beliefs Scale.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (6): 986–996.

- Hambraeus, U. 2014. “Rasbegreppet ska bort ur lagen.” SVT Nyheter. Accessed February 7, 2022 https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/rasbegreppet-ska-bort-ur-lagen.

- Hartmann, D., P. R. Croll, R. Larson, J. Gerteis, and A. Manning. 2017. “Colorblindness as Identity: Key Determinants, Relations to Ideology, and Implications for Attitudes About Race and Policy.” Sociological Perspectives 60 (5): 866–888. doi:10.1177/0731121417719694.

- Humphrey, N. M. 2021. “Racialized Emotional Labor: An Unseen Burden in the Public Sector.” Administration and Society, in press.

- Hübinette, T., and C. Hylten-Cavallius. 2014. “White Working Class Communities in Stockholm.” New York: Open Society Foundations. Accessed February 3, 2022 https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/white-working-class-communities-stockholm#publications_download.

- Hübinette, T., and C. Lundström. 2011. “Sweden After the Recent Election: The Double-Binding Power of Swedish Whiteness Through the Mourning of the Loss of ‘old Sweden’ and the Passing of ‘Good Sweden’.” NORA: Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 19 (1): 42–52. doi:10.1080/08038740.2010.547835.

- Jansen, W. S., M. W. Vos, S. Otten, A. Podsiadlowski, and K. I. van der Zee. 2016. “Colorblind or Colorful? How Diversity Approaches Affect Cultural Majority and Minority Employees.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 46 (2): 81–93. doi:10.1111/jasp.12332.

- Kalton, G. 1983. Introduction to Survey Sampling. Newbury Park CA: Sage.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2018. “‘We are a Small Country That has Done Enormously Lot’: The ‘Refugee Crisis’ and the Hybrid Discourse of Politicizing Immigration in Sweden.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 97–117.

- Kuckartz, U. 2019. “Qualitative Text Analysis: A Systematic Approach.” In Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education, ICME-13 Monographs, edited by G. Kaiser, and N. Presmeg, 181–197. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15636-7_8.

- Lentin, A. 2020. Why Race Still Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lewis, A. E. 2001. “There is no ‘Race’ in the Schoolyard: Color-Blind Ideology in an (Almost) all-White School.” American Educational Research Journal 38 (4): 781–811.

- Lundström, C. 2021. “‘We Foreigners Lived in our Foreign Bubble’: Understanding Colorblind Ideology in Expatriate Narratives.” Sociological Forum 36 (4): 962–983.

- Mathias, J. 2017. “Reforming the Swedish Employment-Related Social Security System: Activation, Administrative Modernization and Strengthening Local Autonomy.” Regional and Federal Studies 27 (1): 23–39.

- Mattsson, K. 2005. “Diskrimineringens andra ansikte–svenskhet och ‘det vita västerländska’.” In Bortom Vi och Dom–Teoretiska reflektioner om makt, integration och strukturell diskriminering, edited by P. de los Reyes, and M. Kamali, 139–158. Stockholm: Regerinskansliet.

- Neville, H., G. Awad, J. P. Brooks, M. Flores, and J. Bluemel. 2013. “Color-blind Racial Ideology Theory, Training, and Measurement Implications in Psychology.” American Psychologist 68 (6): 455–466.

- Neville, H. A., R. L. Lilly, G. Duran, R. M. Lee, and L. Browne. 2000. “Construction and Initial Validation of the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS).” Journal of Counseling Psychology 47 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1037//0022-0167.47.1.59.

- Osanami Törngren, S. 2019. “Talking Color-Blind: Justifying and Rationalizing Attitudes Toward Interracial Marriages in Sweden.” In Racialization, Racism, and Anti-Racism in the Nordic Countries. Approaches to Social Inequality and Difference, edited by P. Hervik, 137–162. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Osanami Törngren, S., and K. L. Suyemoto. 2022. “What Does it Mean to “go Beyond Race”?” Comparative Migration Studies 10 (9): 1–17.

- Penner, L. A., and J. F. Dovidio. 2016. “Racial Color Blindness and Black-White Health Care Disparities.” In The Myth of Racial Color Blindness: Manifestations, Dynamics, and Impact, edited by H. A. Neville, M. E. Gallardo, and D. W. Sue, 275–293. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Plaut, V. C., K. M. Thomas, K. Hurd, and C. A. Romano. 2018. “Do Color Blindness and Multiculturalism Remedy or Foster Discrimination and Racism?” Current Directions in Psychological Science 27 (3): 200–206.

- Raúl, N., and J. Šotala. 2018. “Migrants as Visitors: A Colour-Blind Approach and Imagined Racial Hierarchy.” Lidé Města 20 (2): 237–265.

- Richeson, J. A., and R. J. Nussbaum. 2004. “The Impact of Multiculturalism Versus Color-Blindness on Racial Bias.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40 (3): 417–423. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2003.09.002.

- Roots, A., A. Masso, and M. Ainsaar. 2016. “Measuring Attitudes towards Immigrants: Validation of Immigration Attitude Index Across Countries”. In European Social Survey Conference, (June).

- Rosenthal, L., and S. R. Levy. 2010. “The Colorblind, Multicultural, and Polycultural Ideological Approaches to Improving Intergroup Attitudes and Relations.” Social Issues and Policy Review 4 (1): 215–246.

- Runfors, A. 2006. “Fostran till frihet? Värdeladdade visioner, positionerade praktiker och diskriminerande ordningar.” In Utbildningens dilemma: Demokratiska ideal och andrafierande praxis, edited by L. Sawyer, and M. Kamali, 135–166. Stockholm: Regerinskansliet.

- Runfors, A. 2016. “What an Ethnic Lens Can Conceal: The Emergence of a Shared Racialised Identity Position among Young Descendants of Migrants in Sweden.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (11): 1846–1863. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1153414.

- Safi, M. 2017. “Promoting Diversity in French Workplaces: Targeting and Signaling Ethnoracial Origin in a Colorblind Context.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 3, doi:10.1177/2378023117728834.

- SCB. 2021. Befolkning efter födelseland och år. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden. Accessed February 4, 2022. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101E/FodelselandArK/sortedtable/tableViewSorted/.

- Schierup, C.-U., and A. Ålund. 2011. “The end of Swedish Exceptionalism? Citizenship, Neoliberalism and the Politics of Exclusion.” Race & Class 53 (1): 45–64.

- Schofield, J. W. 1986. “Black-White Contact in Desegregated Schools.” In Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters, edited by M. Hewstone, and R. Brown, 79–92. London: Basil Blackwell.

- Sears, D. O., and P. J. Henry. 2003. “The Origins of Symbolic Racism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 (2): 259–275.

- Shih, M., and M. J. Young. 2016. “Identity Management Strategies in Workplaces with Color-Blind Diversity Policies.” In The Myth of Racial Color Blindness: Manifestations, Dynamics, and Impact, edited by H. A. Neville, M. E. Gallardo, and D. W. Sue, 261–274. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Simon, P. 2010. “Statistics, French Social Sciences and Ethnic and Racial Social Relations.” Revue Française de Sociologie 51 (5): 159–174.

- Simon, P. 2017. “The Failure of the Importation of Ethno-Racial Statistics in Europe: Debates and Controversies.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (13): 2326–2332. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1344278.

- SSIA. 2017. “Statistic and Analysis. Swedish Social Insurance Agency”. Accessed February 3, 2022. https://www.forsakringskassan.se/statistik/.

- Trondman, M. 2006. “Disowning Knowledge: To be or not to be ‘the Immigrant’ in Sweden.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 29 (3): 431–451. doi:10.1080/01419870600597859.

- Voyer, A., and A. Lund. 2020. “Importing American Racial Reasoning to Social Science Research in Sweden.” Sociologisk Forskning 57 (3–4): 337–362.

- Ware, L. 2015. “Color-blind Racism in France: Bias Against Ethnic Minority Immigrants.” Washington University Journal of Law and Policy 46 (1): 185–244.

- Whitley, B. E. Jr, A. Luttrell, and T. Schultz. 2022. “The Measurement of Racial Colorblindness.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi:10.1177/01461672221103414.

- Wickström, M. 2015. The Multicultural Moment: The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, 1964–1975. PhD diss., Åbo: Åbo Akademi University.

- Wise, T. 2010. Colorblind: The Rise of Post-Racial Politics and the Retreat from Racial Equity. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books.

- Wolgast, M., and S. Nourali Wolgast. 2021. “Vita Privilegier Och Diskriminering Processer Som Vidmakthåller Rasifierade Ojämlikheter På Arbetsmarknaden.”

Appendix

Table A1. Colour-blind attitudes translated two ways (%).