ABSTRACT

This paper examines everyday life as a site of refugee politics by zooming in on lived experiences of Syrian male refugees in relation to exclusionary state and public discourses in the Netherlands. I use literature on place-making, encounter and boundary work to explore how privilege, visibility and recognition in public spaces are negotiated. The findings emphasize the messy realities of everyday life, differentiated experiences of oppression and privilege, and the way spatiality and intersectionality are articulated in these experiences. Syrian men experience increased visibility along the lines of gender, race and religion, but counter hostile discourses by claiming space and belonging in everyday places. Moreover, they strategically construct boundaries between themselves and other Syrian men to avoid misrecognition and not-belonging. The insights into intersectional variation are important to nuance the category of Syrian male refugees and raise questions about the unequal social relationships created and reinforced by integration frameworks.

Introduction

In this paper, I investigate the multifarious everyday experiences and responses of Syrian male refugees in the Netherlands in relation to Dutch public discourses and state categories that perpetuate the categorical construction of “undesired refugee masculinities”. The paper’s starting point is that state integration discourses produce a politics of belonging that revolves around an opposition between “migrants” on the one hand and the construction of desired society members on the other (Dahinden Citation2016; Darling Citation2014; Schinkel Citation2013). Public discourses in the Netherlands pertaining to the immigration of Arabic-speaking migrants, as Korteweg and Yurdakul (Citation2009) maintain, centre on a presumed juxtaposition of Islam and Western values, and imagined differences as to how everyday life is organized (see also Gallo and Scrinzi Citation2016). Norms and attitudes regarding gender and partner roles, for example, tend to be considered problematic and detrimental to imagined gender identities and relations in Western host societies (Noble Citation2009; Yurdakul and Korteweg Citation2021). This marginalization of Muslims, or those perceived as Muslim, contributes to societal forms of Islamophobic racism, but also has the purpose or effect of hindering recognition in everyday public spaces (e.g. Amin Citation2002; Hopkins Citation2020).

In particular, public and state discourses in Western arrival societies such as the Netherlands produce a “continuous exclusionary rhetoric of othering” directed at Arab or Muslim refugee men (e.g. Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou, and Wodak Citation2018, 2; Huizinga Citation2022; see also Charsley and Wray Citation2015; Van Heelsum Citation2017). Young Syrian men, then, become stigmatized as media reporting, policy-making and regulations centre around masculinity, ethnicity and presumed religious affiliation. Taking the case of Germany and Canada, Yurdakul and Korteweg (Citation2021) illustrate how national belongings are constructed against “dangerous Muslim masculinities”, processes which effect in discursive structures and formal restrictions that hinder newcomers from participating in everyday life (see also Gallo and Scrinzi Citation2016). Moreover, these structures reinforce images of groups as if their boundaries of culture, identity and collective action are a natural blend. This is problematic as, first, earlier research demonstrates that (Muslim) migrant masculinities are complex and multiple, and masculine roles and identities are enacted differently in varying spaces of everyday life (Hopkins Citation2006; Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2021). Second, using an intersectional lens, researchers have shown how (migrant) men’s lived experiences and daily decision-making processes are entwined with place, social identity categories and personal biographies (e.g. Christensen and Jensen Citation2014; Fathi and Ní Laoire Citation2021; Hopkins Citation2020; Wojnicka and Pustułka Citation2017).

Zooming in on intersectional experiences of visibility and recognition is thus interesting as it bridges migrants’ presence in state and societal discourses on the one hand, and their occupation of everyday life spaces on the other. Brighenti (Citation2007) calls this a spectrum of “fair visibility” (330), i.e. the domain in which a subject experiences appropriate recognition to experience security and belonging. He identifies two boundaries to this domain: A lower threshold of no recognition and social exclusion on one side, and an upper threshold that suggests hypervisibility if surpassed. The boundaries are not fixed. Both invisibility and hypervisibility might be favourable given contextual circumstances in order to claim space and find recognition (Brighenti Citation2007; Noble Citation2009). Everyday responses thus lay bare the nuances and might help to find out what forms of visibility and invisibility are desired, where and for whom? Hence, by using visibility as a perspective, De Backer (Citation2019, 318) argues studies have a potential to focus on interplay, thereby avoiding “idealized, binary understandings of top-down control and bottom-up acts of resistance”.

I seek to bring these debates together by fleshing out how young Syrian refugee men in the Netherlands construct differing emotional linkages, boundaries and belongings in local public spaces in the context of integration frameworks. Ethnicity thus remains part of the intersectional analysis of this paper, yet is explored critically alongside other categories to elucidate variety and “internal and external hegemony” in what might be seen as a homogeneous group (Christensen and Jensen Citation2014, 63). I focus specifically on how patriarchal dividend, (in)visibility and (mis)recognition are experienced in everyday spaces and regulated in the context of refugee integration and national exclusionary discourses.

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, I bring together work on masculinities, visibility and recognition by exploring related literature on place-making, spaces of encounter and boundary work. I go on to introduce the research approach and the methods used to study the everyday lives of participants. I then provide a brief overview of the research context and discuss relevant policies and public discourses in the Netherlands. The findings describe three processes. First, in the post-migration context, participants experience and negotiate increased visibility and misrecognition due to intersections of gender, race and religion. Second, participants actively share and claim space in order to mobilize their own identities. Third, participants distance themselves from problematized ethnic and religious practices and construct boundaries between themselves and other Syrian men. The paper concludes by encouraging to think about the refugee label as complex and transitory in nature, and the potentialities for forced migrants to manoeuvre marginalizing integration policies and societal discourses.

Place-making, spaces of encounter and boundary making

Spaces form the contours of everyday life and are of fundamental value to understanding one’s self and one’s social environment (De Certeau Citation1984; Massey Citation2005). The everyday spaces and politics of social contact and encounter are crucial to living with diversity, overcoming interethnic differences and exploring shared belongings (Amin Citation2002; Wessendorf Citation2019). “Micropublics”, Amin (Citation2002) continues, may grow into spaces of care for interpersonal relationships and negotiation of entitlements, but at the same time should not be seen in isolation from social exclusion, Islamophobia and everyday or institutional racism (see also Hopkins Citation2020). Indeed, no individual is independent of their socio-political and economic context, the complex webs of interdependencies, and the informal social networks that shape well-being and belonging (Gardner Citation2011).

Yet, in the context of refugee dispersal and early settlement, the Dutch government underemphasizes the role of local places in people’s efforts to find security and belonging (Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2018). Rather, spaces are considered an isotropic plain whereon a linear integration path is walked. This is problematic as in fact spaces are shaped by individuals and groups who inhabit and traverse them, which implies that spaces per definition are lived and therefore subject to change (Massey Citation2005). De Certeau (Citation1984) further argues that everyday routines and recurring mundane practices shape connections with spaces through knowledge and familiarity, inscribing spaces with particular meanings. Space, as Lefebvre (Citation1991) points out, eminently remains a site of political importance, in which state-centred or ethnicity-centred discourses and categories can be challenged.

Place-making, i.e. the ways in which individuals and groups use, claim and shape spaces, has been acknowledged by various scholars to identify innovative patterns that migrants and newcomers introduce to host society spaces (e.g. Sampson and Gifford Citation2010; Van Liempt and Staring Citation2020; Wessendorf Citation2019). Indeed, Amin (Citation2002) points out that individuals shape and reshape public space through encounters and meaningful interactions with place. Glick Schiller and Cağlar (Citation2011), too, describe processes in which migrants are scale-makers that organize and evaluate localities on their own terms. In doing so, migrants shape public spaces, become visible, and find recognition and belonging disentangled from the national scale. For example, Ingvars and Gíslason (Citation2018) illustrate how new refugee masculinities emerged as Syrian men enacted practices of care in local places in Greece opposed to stereotypical images concerning refugee men. In a similar vein, Kukreja (Citation2022) demonstrates how male migrant undocumented workers use and claim spaces by playing sports in an act of dare against national bordering regimes.

However, public spaces are under pressure of normative violence as groups enforce their own norms, values, and traditions into the public sphere (Lefebvre Citation1991; Massey Citation2005). Valentine (Citation2007, 19) argues that “in particular spaces there are dominant spatial orderings that produce moments of exclusion for particular social groups”. She points out how local places are shaped by certain rules, behaviors and discourses of bodies that fit in and bodies that do not. A sense of belonging, as she maintains, is thus relational and a configuration fed by a complex web of everyday processes in local places that favor particular intersectional identities (see e.g. Fathi and Ní Laoire Citation2021; Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2018; Peterson Citation2020).

Dominant spatial orderings in the form of everyday acts of racism or microaggressions in public spaces however may be hard to identify due to their locationality (Peterson Citation2020). Exclusionary practices that might render one visible or invisible may be momentary and fleeting (De Backer Citation2019). Peterson (Citation2020) points at racism as implicitly recognized by individuals during daily activities in acts of name-calling, jokes or unfriendly and rude gestures. Although often trivialized in discourses around integration, these acts relate to the victim’s ethnicity and forms of negative recognition and not-belonging (Noble Citation2009).

Indeed, the unpredictable nature of encounter (see Wilson Citation2017), might play into the hands of misrecognition, defined by Brighenti (Citation2007, 324) as not being able to grasp the full set of sense experiences “due to the predominance of one sense over the other”. Syrian men, for example, might be seen as violent and patriarchal due to presumed religious affiliation (Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2021; Ingvars and Gíslason Citation2018). To recognize the full nature of young migrant men’s social being, identities should thus be conceptualized and researched as intersectional, situated and fluid attachments (Charsley and Wray Citation2015; Christensen and Jensen Citation2014; Noble Citation2009).

Scholars thus remain critical about over-romanticising the formative capacities place-making might hold and its potentialities for participation and integration. Gill (Citation2010, 1170) points out that the literature on place-making tends to be rather optimistic regarding the mobilization of identities and actions during times of resettlement by stating that migrant place-making “is prone to difficulties, beset by contingencies and risks, and very often exclusionary”. Also, Veronis (Citation2007) illustrates how migrants feel pressured to emphasize essentialized notions of their identities to “fit” in certain places and be recognized as “fit” enough to be accepted in those places. Amin (Citation2002) consequently argues that socio-spatial relationships form important intersections to flesh out the complexity between immigrants and host societies. So only by identifying everyday realities of diverse, hybrid and volatile attachment, as Korteweg (Citation2017) maintains, can the state’s language of integration be labelled as a farce.

To explore these everyday realities, the study uses work on masculinities and intersectionality that explains specific vulnerabilities and subjectivities as a consequence of different intersections of social identity markers and situated processes of exclusion (Hopkins Citation2019; Yuval-Davis Citation2006). The transformation of such structures is difficult to achieve as men inherently benefit from – what has been termed by Connell (Citation2005) as – a patriarchal dividend. Although men suffer too from harmful relationships due to dominant gender orders and intersectional differences based on class, race and religion, she argues that male identities are inclined to maintain existing structures that favor them over other genders. Christensen and Jensen (Citation2014) however point out that intersectional theory may identify how masculinities can be a product of disempowerment and a lack of privilege due to contextualized power relations. Suerbaum (Citation2018), for example, notes how Syrian male refugees in Egypt establish respectable middle-class masculine identities in relation to Egyptian “others” as well as less respectable masculinities by Syrian men located in Europe.

By scrutinizing between internal and external hegemony as separate analytical dimensions, Christensen and Jensen (Citation2014) put forward the need for intersectionality in masculinities research as dominant forms of masculinity do not always reinforce patriarchal relationships. Indeed, Wojnicka and Pustułka (Citation2017) highlight the role of place in producing internal hegemony and illustrate how male experiences are intersectionally intertwined with spatial power structures, structures which are often new, unfamiliar and disruptive after migration (Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2021). Insights into marginalized and invisible migrant masculinities, and the ways masculinities are used in discourses on forced migration and intersectionally responded to by individual male migrants, therefore offer new perspectives on both migrant men and women’s lives, and the policy and popular discourses that shape these (Charsley and Wray Citation2015).

Lastly, this paper looks into boundary work and the impacts hereof on the transformation of internal and external group boundaries (Lamont and Mizrachi Citation2012). In his taxonomy, Wimmer (Citation2008) distinguishes two strategies that are particularly relevant here. The process of boundary blurring reduces the relevance of ethnic boundaries by shifting focus to non-ethnic aspects of identity. As other intersectional identity features are foregrounded in the conduct of everyday life, the ethnic lens through which people are assumed to interpret the social surroundings is questioned as well as ethnicity as a principle of categorization. Wimmer (Citation2008) further identifies a strategy people employ who do not have access to the central political arena and whose actions are confined to everyday social spaces, e.g. the public realm. By propagating particular aspects of the stigmatized category, people seek to designate moral or cultural equality or superiority opposed to the dominant group. By reinterpreting a stigmatized category in more positive ways, individuals or groups seek to undermine an existing rank order between themselves and members of dominant groups. However, Lamont and Mizrachi (Citation2012) point at the “politics of boundary making” and boundary regimes (see Yurdakul and Korteweg Citation2021), and stress how individual responses ultimately are enabled or constrained by institutions, ideologies, social discourses and culturally defined everyday practices.

Methodology: to talk the walk and walk the talk

The paper draws from forty-two in-depth interviews and eighteen walking interviews. The methods focused on lived experiences of the participants, i.e. the representations of their experiences, aspirations and decisions as well as the knowledge that these experiences, aspirations and choices produced (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2011). By focusing on lived dimensions of refugees’ lives, themes surfaced throughout the interviews that do not often feature in integration or immigration studies, such as visibility, recognition and place-making. The semi-structured interview guide for the in-depth interviews was designed to have the respondent narrate as much as possible during the first part of the interview and then allowed the researcher to follow up and zoom in on relevant responses in the second part of the interview.

The walking interviews followed an open structure by seeking to prompt participants into narrating about their local social and built environment. In most walking interviews, specific narratives and concrete conversations in relation to local spaces emerged in the walking interviews due to “walking probes” (De Leon and Cohen Citation2005). Indeed, Carpiano (Citation2009) states that walking interviews draw attention to the mundane activities of everyday life, activities that are contradictory in nature and often hard to grasp in sedentary interviews. Walking interviews helped to explore experiences of place-making as participants might not be able to “read” the text of the built environment. These experiences might stimulate a socio-political narrative of in and exclusion (Jones et al. Citation2008).

Participants were recruited using the author’s social network, with the help of gatekeepers, and several local and regional organizations working with refugees. Subsequently, snowballing was used to approach friends or relatives of participants, yet caution was taken here in order to maintain a diverse sample (see final paragraph in this section). The empirical materials were collected during three consecutive waves, namely between May and August 2016, between July and October 2018, and between December until March 2020.Footnote1 Interviews were conducted in Dutch or in English, recorded, translated if needed, transcribed and anonymized.

The aim of the analysis was to extract personal narratives and to examine the respondent’s subjective frameworks used to make sense of spaces, people, and social interaction. Narrative was considered important to negotiate with the destination country bias. To capture a wide range of experiences, the first step in the analysis was to develop a codebook around several dimensions of place-making and belonging using qualitative data analysis software NVivo. The conceptual framework of the study, the interview guide and my professional experiences through volunteering at a local organization were used to deductively develop codes and code families. Inductive coding was used whilst going through the transcripts to ensure codes remained close to the data and to retain richness and novelty. Hence, a comprehensive and robust codebook was developed to make sure the researcher did not impose codes on the data (see Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2011). Subsequently, the individual narratives were compared and categorized based on thematic overlap and differences.

In total, forty-four heterosexual men with refugee status participated in this study. They arrived in the Netherlands between late 2014 and early 2017. Participants were between nineteen and thirty-six years old, and were located in different life stages varying from being single, in a relationship, married or with children. Eighteen men were married or in a relationship, of which two with a Dutch partner. Most single men lived alone, except for three men who lived with their natal family. They were from different provinces in Syria, but most had an urban background. The majority of the participants self-identified as Muslim, three as Kurdish, five as Christian and eight men stated to not practice any form of religiosity. Religiosity and the interpretation and practice of religion varied significantly among participants. Sixteen men held a technical university or master’s degree. Younger participants did not start or finish their education due to the civil war. Four participants had a full-time job at the time of interviewing. A group of younger participants worked part-time jobs in construction, retail or hospitality, but most were studying. About half of the participants were living in the city of Groningen (± 200,000 inhabitants), the others in medium-sized towns (< 20,000 inhabitants) or villages (< 2,000 inhabitants).

Research context and state discourses

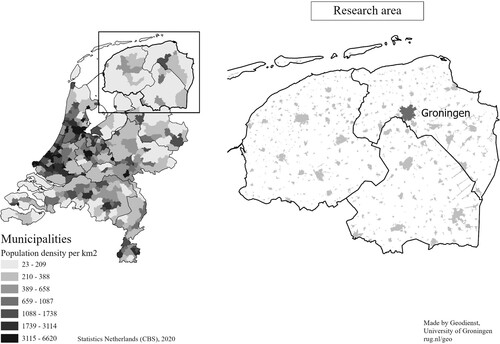

The research area, the northern part of the Netherlands, consists of the provinces of Groningen, Friesland and Drenthe (see ), and has roughly 1.7 million inhabitants. Within the Netherlands, the area can be characterized as less urbanized and more peripheral. Its largest city is Groningen, an international student city with approximately 200,000 residents of whom over 50,000 are students. The city of Groningen is relatively diverse and international due to its student population, but the region has traditionally been home to a fairly homogeneous white population. It is the most secular and ethnically least diverse part of the Netherlands. According to Gallo and Scrinzi (Citation2016), dominant understandings of secularism are key here as they relate closely to imagined regional identities and influence public debates in the Netherlands. Culture-specific amenities such as mosques, ethnic supermarkets or “halal” butchers are scarce. Compared to more super-diverse contexts where migrants may live anonymous lives (see Wessendorf Citation2019), migrants tend to be more visible in this region, specifically the villages (Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2018; Van Liempt and Staring Citation2020).

Figure 1. Population density by municipality in the Netherlands (Left), Research area Northern Netherlands (Right).

The arrival of Syrian migrants in the Netherlands was met with ambiguity and caused significant social and political turbulence (Van Heelsum Citation2017). Nationalistic and nativist agendas took advantage of anti-migration or anti-refugee sentiments, for example, by drawing up narratives in which refugees are depicted as an existential threat to national belonging (Huizinga Citation2022; see also Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou, and Wodak Citation2018). Refugees were accused of stealing native residents’ jobs, occupying advantaged positions within an already tight social housing market, and profiting from Dutch welfare state benefits (Van Heelsum Citation2017). Consequently, in some areas incidents were observed between existing residents and refugees, and on some occasions riots were organized near asylum seeker centres. At the same time, numbers of volunteers and donations rose and media coverage that addressed the injustice asylum seekers and refugees faced increased. In fact, compared to other groups such as Eritrean and Ethiopian migrants during that time, Syrian migrants, at least as a group, received significant attention and welcoming activities.

Asylum claims of Syrians were often successful. Upon receiving refugee status, refugees move out of asylum seeker centres and are distributed among municipalities in the Netherlands using a dispersal key. Social housing corporations offer refugees housing and from that moment can initiate their civic integration programme. Many Syrian refugees struggle to complete civic integration tasks (Van Liempt and Staring Citation2020). Language acquisition and access to work are deemed important by Syrian refugees to participate in Dutch society. The quality of teachers and education in civil integration courses, however, is poor due to the neo-liberal organization of integration procedures and the dependency on volunteers. Many experience pressure and stress to complete the civic integration exam. This has negative impacts on refugees’ participation in society and produces negative representations of the “unwilling” refugee. Bonjour and Duyvendak (Citation2018) identify a denial of state responsibility in integration processes in the Netherlands, and point out how certain migrants are blocked from participation due to intersections of gender, class and race. The “migrant with poor prospects”, they argue, is implicitly assumed to be Muslim.

Negotiating patriarchal dividend alongside gendered, racial and religious lines

I now turn to the empirical sections of the paper. The data demonstrate that during the early stages of settlement, public spaces were often concrete sites where participants tried to make sense of new and sometimes problematic social relationships. Similar to findings by Suerbaum (Citation2018) and Huizinga and van Hoven (Citation2021), many contrasted their everyday experiences in terms of social identities and relations with an imagined hegemonic position in local areas of origin. In order to flesh out these relationships between participants and public spaces in the Netherlands, it is important to consider how participants experienced the public sphere in pre-migration contexts, and how attachments to public places took form alongside gendered, racial and religious lines.

Many participants mentioned perceiving public spaces in areas of origin as important social spaces to negotiate male identities. Although research shows gender relationships in Islamic public spaces are fluid (e.g. Mazumdar and Mazumdar Citation2001), the men in this study mentioned strong gendered connotations. Coman (31), explains during our walk through his quiescent neighborhood,

This is for me the biggest difference between my life here and Syria. In Syria, people go outside specifically to talk to each other. There are always people around your house or in the bar or something. [Here] I see sometimes people leaving the house, but they never say anything. You know, it was very warm weather in the last few days. I didn’t see anybody sitting outside.

What do you talk about when you meet people outside?

Well … yeah … nothing special. It’s just talking about normal things. I don’t know. It’s also about being with the guys, with young guys and old men together. We talk about our work or maybe the future. What do we want to do, how can I earn more money? Haha, normal things. We drink coffee and tea. We play games. We like football so we talk about football. That’s it. (Coman, 31, university degree, unemployed, single)

Despite differing personal views towards gender relations, most of the men in this study mentioned to have little experience with public spaces in pre-migration contexts as being exclusionary, restrictive or unsafe. Many participants provided examples of situations in which they displayed unusual or forbidden (haram) attitudes, norms and behaviors in close proximity to others. Other men talked about engaging in everyday activities in public spaces generally considered forbidden, such as drinking, smoking or not participating in prayer or other religious practices. The data illustrate that participants’ actions were only seldom problematized in pre-migration contexts. Amin (36), who prior to migration was living in the city of Damascus, exemplifies,

Look, when I was in Syria, as I told you, I did not partake in the Ramadan. But I smoke, in the Ramadan, I just smoked on the street. Next to my house, in Syria. No problem. They don’t criticise me […] They tell me I’m a good man, but I don’t act as a Muslim. I don’t pray, I don’t fast and I drink alcohol. They know everything about me, you know, but they don’t give me any criticism. (Amin, 36, university degree, unemployed, married)

Hence, since invisibility is an important feature of privilege, belonging for participants was something considered everyday (Wojnicka and Pustułka Citation2017). Their belonging in the Netherlands however is highly contested and brings about ruptures in understandings of themselves and others as well as a lack of “spatial security” in their everyday living environments (see Fathi and Ní Laoire Citation2021). The data show that the social identity markers – gender, race and religion – that appeared to sustain a certain degree of privilege in origin areas, are the same that put participants in an inferior position in the Netherlands, highlighting the spatiality and intersectionality of hegemonic masculinities among migrant men (Wojnicka and Pustułka Citation2017).

Indeed, due to local public discourses and everyday acts of discrimination in public spaces, most participants mentioned to be hyper vigilant as their gender, race and religion are problematized. They explicitly pointed out experiences in which they felt reduced to being a man with a “Middle-Eastern” appearance. They often experience difficulties to be their normal self as others make them a dangerous “Other”, i.e. a religious, patriarchal, brown man. Wasim (33) says, “Look, for you [me, the researcher], it’s not a problem. You’re white, people don’t care. But I have color. Strange behavior from me is even more strange because of my darker hair and beard”. Hamzah (31), too, describes his experiences during his daily walk. “People are a bit afraid in the street when they see me”. He mentioned a specific encounter with a Dutch man that appeared frightened, turned around and moved the other way. “I have a darker color and I have a beard. He probably thought ‘Allah Akbar’, boom!”. Upon finishing the walking interview, Aied (24) confessed he was surprised that passers-by had greeted us. “You should come here more often”, he said, “normally they don’t say hi to me. They often take a detour when they see me to be honest”. Syad (23) further notes,

There is suddenly more pressure here. There is a certain feature or a sort of stereotype attached to me, to my appearance. Dutch people think I am stupid. They told me that my presence at the university is unwanted. They distanced themselves from me. They don’t like it that I obtained a spot in the university. They tell me ugly things you know. (Syad, 23, studying university, in a relationship)

Navigating the visibility equilibrium and enacting hypervisibility

Many of the men used public spaces to make sense of their new position and local social environment. Social contact in these spaces, however, was hard to find due to different time-geographies between participants and existing residents. Existing residents and participants were hardly in the same place at the same time. This was disappointing for participants as many felt the need to show and express themselves, to participate and to challenge negative stereotypes in everyday life. Some places were used to find familiarity, comfort and recognition, and to reinforce a collective identity. These places involved ethnic or migrant places such as “Turkish” supermarkets, barbershops or religious centres (see also Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2018). At the same time, everyday spaces such as parks or benches surfaced in the analysis (see also Van Liempt and Staring Citation2020; Sampson and Gifford Citation2010).

A more narrowly defined place that materialized in the interviews were “the stairs” at “De Grote Markt” in Groningen. De Grote Markt, one of the main market squares in the city centre, is a crowded and vibrant area, surrounded by government buildings, offices, shops, restaurant and bars. During most parts of the day, there is a constant flow of people passing through. Prior to and during my time of fieldwork, the stairs were installed as a temporary installation positioned in the centre of the square over the course of eight years. It has recently been taken down. The stairs were part of the tourist information office and served as a place to sit down, rest, eat or drink, and to look out over the square. Following Gardner’s (Citation2011) conceptualization of “natural neighborhood networks”, the square in this capacity embodies the function of a transitory zone as well as a third place, meaning that social relationships are made with both others who are usually there to hang out or those traversing the square.

For quite some participants, then, the stairs functioned as a landmark and important meeting point. Many mentioned them as one of the favorite places in the city to visit, and, during the walking interviews, participants would frequently include the stairs in the route. Despite that participants had only recently arrived, it was interesting to observe that participants produced meanings and emotional attachments to this place in such a short time. Aziz (25), one of the participants, illustrates,

Well, I really just like the city, the city itself. I like to walk around there, with my friends. And what I like most is the centre. Sometimes I just go there, and sit on the stairs at the Grote Markt and talk with my friends. I mean, I like that place. It’s just … I begin to feel I belong to that place. That might sound ridiculous since in only live here for three years, but it’s true. (Aziz, 25, basic education, unemployed, single)

As soon as I show more of myself, then … you know … we talk about football, we talk about this and that. Enjoying nice moments together, and making yourself more visible, do you understand? More of what you see here [points in the direction of his heart], then what you see here [points at skin color of his arm]. I experienced all these barriers before, and now I see all these barriers disappear. Gone. Sometimes the people that in first instance distanced themselves from me, now start to talk to me, and pick me above other people they could talk to. (Majed, 23, studying university, single)

However, the extent to which the stairs was perceived as a locus for belonging and identity was relational and subject to change (see also De Backer Citation2019; Valentine Citation2007). On other occasions, participants mentioned to experience everyday racist practices or micro aggressions (Peterson Citation2020). Here, repetitive encounters with difference rather seemed to reinforce existing stereotypes and prejudices. One of the participants, Amin (36), mentioned to frequently visit the stairs during his daily strolls. When he was sitting at the stairs to enjoy his lunch, he was singled out by a man who accused him of being a “lazy refugee”, and that he should spend his time working. He reflects on this experience by saying that,

Some people do not like the refugee. They always speak negatively about the refugee. Always. People have told me I am here to steal their money, that I’m no good. They say that they pay taxes for people that don’t want to work and want to stay at home or hang around outside. That’s what they pay taxes for, for them. And they think that they are smarter than other people. But this is not true. (Amin, 36, university degree, unemployed, married)

We often hang out at the Grote Markt. You know … the place with the stairs. We go there to talk, and to drink and eat something. We eat chips, for example, and listen to music. We sometimes put on loud music. We mostly listen to Turkish music or Arab music. We like this type of music, but … yeah … I don’t think other people like this type of music, haha … . (Saad, 25, basic education, part-time construction work, single)

Responding to misrecognition through “horizontal hostilities”

Social discourses in the Netherlands around Syrian refugee men suggest that their culture, identity and collective action are a natural blend. Stigmatization in public discourses draws symbolic boundaries that create binary constructions of “us” versus “them”. The personal biographies of participants, however, show differing experiences and responses in both areas of origin and arrival. Responses are intertwined with development opportunities and challenges embedded in the local contexts and public spaces. For some participants, it was frustrating to experience that their norms, values and attitudes as respectable men were not recognized. A large share of participants felt that it was time to move on and explore identities that might have been concealed or repressed before. Majed (23) illustrates this process and explains that,

Perhaps I make use of the things in my environment to become more positive about myself and to positively develop myself. Yes, so I look at everything that I went through during my flight and here in the Netherlands. The difference between Syria and Netherlands is very much in my advantage in terms of my personality. How I look at life. How I think, my mentality, and yes, my personality. Everything. I think that this is a very big and important phase to define who I am now. (Majed, 23, studying university, single)

Other participants, too, mentioned they rather avoided places like ethnic supermarkets, mosques or welcoming initiatives for migrants. Participants frequently said they wanted to avoid situations in which they had to deal with misrecognition due to their status as Syrian male refugees. Moaz (21), one of the participants who identified as Christian, often heard “ah … you must be a Muslim because you are from Syria”. His local buddy in the city of Groningen took him to the mosque during one of their first meetings. Although Moaz perceived the event as a thoughtful gesture, it also emphasized the dissonance in his sense of belonging. Other participants organized their daily activities in such a way that they could avoid particular spaces. Hevdem (33) illustrates,

Maybe some people really feel lonely. So they try to look for Syrian or Islamic communities just to share topics or something like that. Same is with the mosque with all the Islamic or Syrian people. The Turkish shop is also a way to meet the people. But actually, I not really like to go there to talk to people. I can find someone else to talk. Maybe Dutch or Syrian, but not in these places. I don’t go there for that purpose. (Hevdem, 33, university degree, unemployed, single)

The data demonstrate that some participants are better capable of grasping the oppressive dominant structures in public spaces in relation to social discourses. Bonjour and Duyvendak (Citation2018) write that class has largely been ignored in migration and belonging literature. Participants who obtained a university degree or who had professional careers prior to the war, more often mentioned to be frustrated that their achievements and aspirations were not recognized in the Netherlands (see also Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2021; Suerbaum Citation2018). In relation to norms, values and attitudes, participants who received higher education or who came from middle-class families often emphasized their personal biographies to construct boundaries with others. The stigma of refugee men being unwilling to change is thus passed down the ladder to those with lower education. Omar (26), for example, says,

This separation between men and women is there in Syria, the man is up here, and the woman is down there, even if she is higher educated. It doesn’t matter, she is worth less than the man. This idea, yes, I don’t have it […] I go with my wife to bars or movies. Or two weeks ago, we went to the football stadium together. In Syria I also walked hand in hand with my wife. But a [Syrian] friend of mine in Groningen still walks in front of his wife on the street. I thought he is crazy, why would you do that?! […] I don’t know exactly why. Maybe because he did not study in Syria. This is not the Syrian culture, this is the culture of old religious men. (Omar, 26, university degree, employed, married)

Conclusion

The paper contributes to a better understanding of male refugees’ various lived experiences in place, how masculinities after migration are articulated following intersections of identity markers, and how repression due to state definitions and public discourses is challenged using bottom-up strategies. The empirical sections illustrate how young Syrian men experience “new” forms of exclusion and not-belonging after migration as the patriarchal dividend they experienced in Syria stopped paying out in their new local areas. They further demonstrate that participants negotiate visibility by seeking out or claiming public spaces where they can participate or stand out in order to develop a sense of self-worth and belonging. Last, to avoid and counter misrecognition, the participants position themselves in relation to other Syrian refugee men through different spatial routines and, in so doing, shape new intra-group boundaries and hierarchies. By emphasizing how young Syrian refugee men mobilize their own personal biographies, voices and agencies to increase visibility and recognition, insights are gathered that show their contribution to society and the development of convivial public spaces. They take up space, leave traces to transform places and therefore undoubtedly belong, even though this comes with high emotional costs (see Darling Citation2014; Glick Schiller and Cağlar Citation2011; Sampson and Gifford Citation2010; Wessendorf Citation2019).

I see two main contributions. First, the paper contributes to an in-depth spatial and intersectional understanding of gender hierarchies and subordinated masculinities in the context of forced migration and integration. Using Amin’s idea of “micropolitics”, it highlights the opportunities and constraints for visibility and recognition in local places as well as through institutions, ideologies and regulations. These insights add to a more refined understanding of the challenges faced by (forced) migrant men across various spatial contexts and the ways in which intersectional boundary making shapes internal and external hegemonic relationships (Christensen and Jensen Citation2014; Wojnicka and Pustułka Citation2017). The paper, therefore, talks about dynamic forces rather than fixed categories. By recognizing refugee men as gendered social actors who shape and are shaped by local places, the findings highlight the adaptability of masculinities and the conscious appropriation of spatio-temporal opportunities to carve out a space to belong (see also Ingvars and Gíslason Citation2018; Kukreja Citation2022; Suerbaum Citation2018). Using the unpredictability of everyday encounter as a lens (Wilson Citation2017), the paper draws attention to locality and fleeting conceptualizations of masculine gender identities through everyday spatial routines.

Second, the paper emphasizes that the political and bureaucratic reality of citizenship, integration and belonging does not reflect everyday realities, i.e. how everyday spaces are lived, navigated and made sense of. National governments tend to overlook multiple and contrasting masculinities as described in this paper but rather employ stereotypical ideas of migrant men that hide vulnerability (Charsley and Wray Citation2015). Building on Darling “acts of citizenship” (Citation2014), I argue that male refugees’ irregular acts to negotiate boundaries and claim belonging should be understood as relevant processes through which asylum and integration can be re-constructed and migrant exclusion can be resisted (see also Ingvars and Gíslason Citation2018; Kukreja Citation2022).

By using different analytical and intersectional categories to study the “common-sense category of refugees” and the social relations it brings forth (see Dahinden Citation2016, 2208), the paper illustrates that the refugee label itself creates particular realities that hinder personal development, belonging and participation in society. Syrian male refugees, as a group, thus have a longer trajectory to complete (see also Schinkel Citation2013). Consequently, their individual “failed” attempts to integrate may be attributed to their membership of larger cultural groups, thereby neglecting the exclusive social processes and normalization discourses that reinforce national belongings and group formation (Dahinden Citation2016; Schinkel Citation2013). Unless Syrian refugee men are not depicted as an unequivocal and frightening category, perceived as a threat to an imagined Dutch society, their everyday lives remain unchanged.

Ethics statement

This research is given ethical clearance by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Spatial Sciences, University of Groningen.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Laura Morosanu and Sarah Scuzzarello for setting up this special issue and for their ongoing encouragement while writing this paper. Thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers for proving me with insightful and supportive comments. Last, this paper could not have been written without the participants. Thank you for taking the time and effort to share your experiences with me.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Data were collected before restrictive measures regarding data collection in the Netherlands due to the Covid19 pandemic were in place.

References

- Amin, A. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A 34: 959–980. doi:10.1068/a3537.

- Bonjour, S., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2018. “The ‘Migrant with Poor Prospects’: Racialized Intersections of Class and Culture in Dutch Civic Integration Debates.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (5): 882–900. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1339897.

- Brighenti, A. 2007. “Visibility: A Category for the Social Sciences.” Current Sociology 55 (3): 323–342. doi:10.1177/0011392107076079.

- Carpiano, R. M. 2009. “Come Take a Walk with Me: The ‘Go-Along’ Interview as a Novel Method for Studying the Implications of Place for Health and Well-Being.” Health & Place 15: 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003.

- Charsley, K., and H. Wray. 2015. “Introduction: The Invisible (Migrant) Man.” Men and Masculinities 18 (4): 403–423. doi:10.1177/1097184X15575109.

- Christensen, A., and S. Q. Jensen. 2014. “Combining Hegemonic Masculinity and Intersectionality.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 9 (1): 60–75. doi:10.1080/18902138.2014.892289.

- Connell, R. W. 2005. Masculinities. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dahinden, J. 2016. “A Plea for the ‘De-Migranticization’ of Research on Migration and Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2207–2225. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1124129.

- Darling, J. 2014. “Asylum and the Post-Political: Domopolitics, Depoliticisation and Acts of Citizenship.” Antipode 46: 72–91. doi:10.1111/anti.12026.

- De Backer, M. 2019. “Regimes of Visibility: Hanging out in Brussels’ Public Spaces.” Space and Culture 22 (3): 308–320. doi:10.1177/1206331218773292.

- De Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- De Leon, J. P., and J. H. Cohen. 2005. “Object and Walking Probes in Ethnographic Interviewing.” Field Methods 17 (2): 200–204. doi:10.1177/1525822X05274733.

- Fathi, M., and C. Ní Laoire. 2021. “Urban Home: Young Male Migrants Constructing Home in the City.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1965471.

- Gallo, E., and F. Scrinzi. 2016. Migration, Masculinities and Reproductive Labour. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Gardner, P. 2011. “Natural Neighbourhood Networks – Important Social Networks in the Lives of Older Adults Aging in Place.” Journal of Aging Studies 25 (3): 263–271. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.007.

- Gill, N. 2010. “Pathologies of Migrant Place-Making: The Case of Polish Migrants to the UK.” Environment and Planning A 42: 1157–1173. doi:10.1068/a42219.

- Glick Schiller, N., and A. Cağlar. 2011. Locating Migration: Rescaling Cities and Migrants. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hennink, M., I. Hutter, and A. Bailey. 2011. Qualitative Research Methods. London: Sage.

- Hopkins, P. E. 2006. “Youthful Muslim Masculinities: Gender and Generational Relations.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 31 (3): 337–352. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00206.x.

- Hopkins, P. E. 2019. “Social Geography I: Intersectionality.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (5): 937–947. doi:10.1177/0309132517743677.

- Hopkins, P. E. 2020. “Social Geography II: Islamophobia, Transphobia, and Sizism.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (3): 583–594. doi:10.1177/0309132519833472.

- Huizinga, R. P. 2022. “Making Home in Forced Displacement: Young Syrian Men Navigating Everyday Geographies of Migration, Belonging and Masculinities in the Netherlands.” Doctoral thesis, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. https://research.rug.nl/en/publications/making-home-in-forced-displacement-young-syrian-men-navigating-ev.

- Huizinga, R. P., and B. van Hoven. 2018. “Everyday Geographies of Belonging: Syrian Refugee Experiences in the Northern Netherlands.” Geoforum 96: 309–317. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.002.

- Huizinga, R. P., and B. van Hoven. 2021. “Hegemonic Masculinities After Forced Migration: Exploring Relational Performances of Syrian Refugee Men in The Netherlands.” Gender, Place & Culture 28 (8): 1151–1173. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2020.1784102.

- Ingvars, A. K., and I. V. Gíslason. 2018. “Moral Mobility: Emergent Refugee Masculinities among Young Syrian in Athens.” Men and Masculinities 21 (3): 383–402. doi:10.1177/1097184X17748171.

- Jones, P., G. Bunce, J. Evans, H. Gibbs, and J. Rickets Hein. 2008. “Exploring Space and Place with Walking Interviews.” Journal of Research Practice 4 (2): D2.

- Korteweg, A. C. 2017. “The Failures of ‘Immigrant Integration’: The Gendered Racialized Production of Non-Belonging.” Migration Studies 5 (3): 428–444. doi:10.1093/migration/mnx025.

- Korteweg, A. C., and G. Yurdakul. 2009. “Islam, Gender and Immigrant Integration: Boundary Drawing in Discourses on Honour Killing in the Netherlands and Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (2): 218–238. doi:10.1080/01419870802065218.

- Krzyżanowski, M., A. Triandafyllidou, and R. Wodak. 2018. “The Mediatization and the Politicization of the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Europe.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 1–14. doi:10.1080/15562948.2017.1353189.

- Kukreja, R. 2022. “Using Indigenous Sport as Resistance Against Migrant Exclusion: Kabaddi and South Asian Male Migrants in Greece.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2036954.

- Lamont, M., and N. Mizrachi. 2012. “Ordinary People Doing Extraordinary Things: Reponses to Stigmatization in Comparative Perspective.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (3): 365–381. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.589528.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. London: Basil Blackwell.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mazumdar, S., and S. Mazumdar. 2001. “Rethinking Public and Private Space: Religion and Women in Muslim Society.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 18 (4): 302–324.

- Noble, G. 2009. “Countless Acts of Recognition’: Young men, Ethnicity and the Messiness of Identities in Everyday Life.” Social & Cultural Geography 10 (8): 875–891. doi:10.1080/14649360903305767.

- Peterson, M. 2020. “Micro Aggressions and Connections in the Context of National Multiculturalism: Everyday Geographies of Racialisation and Resistance in Contemporary Scotland.” Antipode 52 (5): 1393–1412. doi:10.1111/anti.12643.

- Sampson, R., and S. M. Gifford. 2010. “Place-Making, Settlement and Well-Being: The Therapeutic Landscapes of Recently Arrived Youth with Refugee Backgrounds.” Health & Place 16: 116–131. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.004.

- Schinkel, W. 2013. “The Imagination of ‘Society’ in Measurements of Immigrant Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1142–1161. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.783709.

- Suerbaum, M. 2018. “Becoming and ‘Unbecoming’ Refugees: Making Sense of Masculinity and Refugeeness among Syrian Refugee men in Egypt.” Men and Masculinities 21 (3): 363–382. doi:10.1177/1097184X17748170.

- Valentine, G. 2007. “Theorizing and Researching Intersectionality.” The Professional Geographer 59: 10–21. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00587.x.

- Van Heelsum, A. 2017. “Aspirations and Frustrations: Experiences of Recent Refugees in the Netherlands.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (13): 2137–2150. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1343486.

- Van Liempt, I., and R. Staring. 2020. “Homemaking and Places of Restoration: Belonging Within and Beyond Places Assigned to Syrian Refugees in the Netherlands.” Geographical Review 111 (2): 308–326. doi:10.1080/00167428.2020.1827935.

- Veronis, L. 2007. “Strategic Spatial Essentialism: Latin Americans’ Real and Imagined Geographies of Belonging in Toronto.” Social & Cultural Geography 8 (3): 455–473. doi:10.1080/14649360701488997.

- Wessendorf, S. 2019. “Migrant Belonging, Social Location and the Neighbourhood: Recent Migrants in East London and Birmingham.” Urban Studies 56 (1): 131–146. doi:10.1177/0042098017730300.

- Wilson, H. F. 2017. “On Geography and Encounter: Bodies, Borders, and Difference.” Progress in Human Geography 41: 451–471. doi:10.1177/0309132516645958.

- Wimmer, A. 2008. “Elementary Strategies of Ethnic Boundary Making.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31 (6): 1025–1055. doi:10.1080/01419870801905612.

- Wojnicka, K., and P. Pustułka. 2017. “Migrant Men in the Nexus of Space and (Dis)Empowerment.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 12 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1080/18902138.2017.1342061.

- Yurdakul, G., and A. C. Korteweg. 2021. “Boundary Regimes and the Gendered Racialized Production of Muslim Masculinities: Cases from Canada and Germany.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 19 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1080/15562948.2020.1833271.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Intersectionality and Feminist Politics.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 13 (3): 193–209. doi:10.1177/1350506806065752.