ABSTRACT

In the twentieth century, European migrants’ ethnic and racial status changed as they joined the mainstream. Assimilation theory identified socioeconomic mobility as the driver of this outcome. More recently, non-European migrants have also achieved socioeconomic parity with the mainstream. Yet, a puzzle has emerged: unlike earlier European migrants these non-Europeans remain “racialized”. They are both a part of, and excluded from, the majority group. This paper proffers a transnational amendment to assimilation theory. While socioeconomic parity matters so too does the similarity between the imagined racial status of the origin and host country. Groups originating from geographies that are imagined as outside of transnational Whiteness remain a “racial minority”. Groups originating from geographies that are imagined as within transnational Whiteness are already White and, thereby, assimilated. To delineate this transnational approach to assimilation and inclusion, we provide examples from Europeans’ and non-Europeans’ assimilation trajectories.

Introduction

Assimilation theory, in the twentieth century US, sought to explain European immigrants’ assimilation trajectories. Since the 1960s reforms to US immigration laws, an increasing number of immigrants originate from outside of Europe. Six decades of research has now asked whether these groups will also join the White majority or mainstream. This focus on non-Europeans’ assimilation has gradually shifted the focus away from European immigrants. Yet, it seems that the decades-long research with non-European groups has reached a somewhat contradictory stage. If outcomes such as intermarriage, residential, socio-economic, and linguistic parity with White groups are connotative of assimilation, then the majority of those with non-Europeans origins show the signs of fulfilling such requirements. Non-Europeans’ intergroup marriage rates remain at historically high rates (Qian and Qian Citation2020; Qian and Lichter Citation2007), their residential proximity with the core group has increased (Obinna and Field Citation2019; Crowell and Fossett Citation2018), and their educational and occupational attainments resemble and near those of White Americans (Pew Research Center Citation2020; Jiménez Citation2017). In contrast, many Europeans still arrive with low socioeconomic status and educational-linguistic skills.Footnote1

It is then curious that there is a lingering focus on the assimilation of non-Europeans and a concomitant absence of interest in European and North American immigrants. In this paper, we examine this puzzle. We begin with the premise that intergroup interactions lead to intergroup similarities and assimilation, albeit to varying degrees (Gordon Citation1964, 71). In the US context, the end goal of the assimilation process is to join Whiteness, or, more recently, what has been called the mainstream (Alba Citation2020, 149). Whiteness is an elastic ideational category even though it is currently essentialized as synonymous with certain bodies (Painter Citation2010; Greer, Mignolo, and Quilligan Citation2008). Whiteness is a tool for sustaining racial distance between Whites and racial Others, particularly those Others who fall into a Black category (Horne Citation2018; Roediger Citation1999). Currently, the transnational boundary of Whiteness overlaps with Christianity, the transnational geography of the West, and European ancestry (Bonnett Citation1998).Footnote2 Based on this premise, those who come from the countries and geographies that are imagined (Anderson [Citation1983], 2006) as outside of transnational Whiteness remain as “racial minorities” who need to assimilate, if ever (Schinkel Citation2017). In contrast, those who hail from geographies already imagined as part of extra-national Whiteness are always already White and, thereby, assimilated (see Nancheva and Ranta Citation2021 on European migrants’ non-integration in the UK).Footnote3

In this transnational approach to assimilation theory, socioeconomic assimilation informs only half of the story (see Karimi and Wilkes Citation2023 on the boundary model of assimilation). The other half points to elasticity, or lack thereof, of Whiteness vis-à-vis the imagined racial status of immigrant groups’ region or country of origin. A transnational approach to assimilation captures the totality of the assimilation process by bringing together assimilation theory’s focus on what immigrants do and the interdisciplinary Whiteness Studies’ focus on how Whiteness expands-contracts in response to immigration (see Alba Citation2007). Yet, instead of simply combining research on assimilation and Whiteness, this paper adds a transnational analytical lens. To date, methodological nationalism, the assumption that the nation-state is the natural socio-political form and unit of analysis (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002), informs assimilation theory. As such, the role of transnational Whiteness and the country of origin’s racial status has not received sufficient attention in assimilation research. The transnational approach offered in this paper, conceptualizes assimilation through two concurrent processes. First, at the national level, immigrants’ actions such as intermarriage and spatial proximity with the majority lead to a sense of similarity. Second, at the transnational level, immigrants and those living in countries of origin promote the idea of racial similarity between the home and host (White) countries. Otherwise, at the cognitive level, it would be impossible to perceive newcomers’ country of origin as non-White but categorize these groups as Whites in the US. Then, racial categories are symbolic categories “tied to extra- and transterritorial conceptions and expressions, those that circulate in wider circles of meaning and practice” (Goldberg Citation2009, 1273).

To make sense of assimilation and Whiteness in the US, we present a new reading of the Eastern and Southern Europeans’ trajectories during the twentieth century. We then contrast this with the case of Iranian and Mexican groups. We highlight two aspects of assimilation trajectories. On the one hand, European newcomers, not unlike other groups, claimed their eligibility for citizenship and inclusion into Whiteness by proving that their country of origin was White. On the other hand, these groups not only adopted the norms of the White majority in the US, but they also exported this US-based Whiteness back to their homelands and, through sociopolitical advocacy, incorporated their countries of origin into transnational Whiteness. Since then, the boundary of Whiteness has expanded to include Europeans’ homeland geographies. Today, their assimilation and membership in Whiteness is a matter of fact. Conversely, non-Europeans’ homeland geographies remain outside of transnational Whiteness and, therefore, they remain the sole focus of assimilation research in the US. In what follows, we unpack the different iterations of assimilation theory and, building on transnational race in migration studies, re-visit assimilation process through a transnational lens. This approach invites attention to the boundary expansion-contraction of Whiteness, a property of the majority group, instead of an exclusive focus on minorities’ boundary-crossing actions (Karimi and Wilkes Citation2023).

Assimilation theory and a transnational lens

As with other sociological theories of the twentieth century, assimilation theory is also shaped by methodological nationalism. That is, in assimilation theory the nation-state is the natural divider of societies and the petri dish within which all social phenomena unfold (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002). Accordingly, racial categories are treated as native to the US and essentialized to somatic bodies while the theory has yet to consider the ideational aspect of racial categories and the ways these categories were first imported from other global regions. Methodological nationalism of assimilation theory also indicates that newcomers are “racialized” when they arrive in the US or, put differently, that they do not have racial identities prior to their arrival. Overall, the more popular use of assimilation theories has been to examine the assimilation process within a nation-state whose literal and imagined boundaries contain an “indigenous” White Anglo-Saxon population as well as non-White migrants (see also Elgenius and Garner Citation2021).

In this conceptualization, the main distinction is between the White and non-White colour line. Currently, in the US, the categories of nation, White Anglo-Saxon race, and Whiteness overlap (see Brubaker Citation2009). Such categorical conflation, then, contrasts with the non-White groups who remain outside of the White colour and, thereby, at the margins of the imagined White nation (Anderson [Citation1983] 2006; Lipsitz Citation1995). This division of groups across the colour line directly informed classic assimilation theory. In the early twentieth century, when assimilation theory was first formulated, White colour line mainly comprised North-Western European Anglo-Saxons. Eastern and Southern Europeans were inside the White colour line but not on par with the Anglo-Saxons (Bertossi, Duyvendak, and Foner Citation2021; Roediger Citation1999). The non-White colour section included African-Americans – the supposed members of the “cosmopolitan” nation (Higham Citation1955) – as well as Asian and Hispanic or Latino groups.

The pioneers of assimilation theory, who stood in and reflected the Whiteness viewpoint, observed Eastern and Southern European immigrants’ life trajectories in the US with a view to examine their transition and inclusion into Anglo-Saxon Whiteness. The theorists considered non-European groups such African Americans and Asians, but maintained that their assimilation is unlikely since they sit on the wrong side of the colour line (Park Citation1914, 611; see Cox Citation1944 for a critique).Footnote4 Accordingly, assimilation entailed minority groups assimilating into majorities and majority groups incorporating the said minorities (Cox Citation1944, 606). Gordon (Citation1964, 74) further expanded and consolidated the theory. His outline of the assimilation process includes more groups such as “Blacks, Jews, Catholics, and Puerto Ricans” (Citation1964, 75). Yet, he too concluded that race and ethnicity, of both majority and non-European minority groups, have proved to be hardy elements of assimilation process (Gordon Citation1964, 25). The central role of Whiteness versus immigration and its attachment to religion, geography, and European race goes unexamined in classic assimilation.

Segmented-assimilation theory, in the 1990s, updated the classic theory to argue that, despite the US’ economic and racial structures, ethnic communities provide cultural and economic support for non-Europeans’ offspring to climb the race-class ladder into the core cultural group (Zhou Citation1997; Portes and Zhou Citation1993). According to the theory, because European newcomers, who were deemed White, had access to well-paying industrial jobs, they assimilated into the middle-class White category. However, the current service economy and the entrenched racial hierarchies impede non-Europeans’ economic, linguistic, and socio-spatial assimilation. While some individuals still follow the classic assimilation trajectory, these racialized groups mainly rely on their ethnic economy for assimilation or, alternatively, they risk devolution into the underclass culture (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001).

Segmented-assimilation theory’s view of racial boundaries resembles those of its contemporaneous race theories. The modern American racial theories offer a static understanding of race as essentialized with phenotypes observed in the present-day US (see Wimmer Citation2015; Alba Citation2009; and Loveman Citation1999 for critiques). Accordingly, because “racialization began very early in the United States and never went away” (Omi and Winant Citation2014, 247 italics added), these theories perceive a widening racial gap between groups as a result of systemic (Feagin Citation2013) and structural racism (Bonilla-Silva Citation1997). Even when some of these groups show signs of mobility, the response is to count them as exceptions, as model minorities in an “ambiguous position in relation to national identity” (Zhou, Bankston, and L Citation2020, 235; also Haller, Portes, and Lynch Citation2011). Both segmented-assimilation and mainstream race theories overlook race as an ideational category that was imported to the US and, thereby, stretches beyond national boundaries. Accordingly, segmented-assimilation does not necessarily capture non-Anglo-Saxon Europeans’ assimilation experiences (Perlmann and Waldinger Citation1997) and has yet to examine the impact of transnational racial categories on assimilation outcomes.

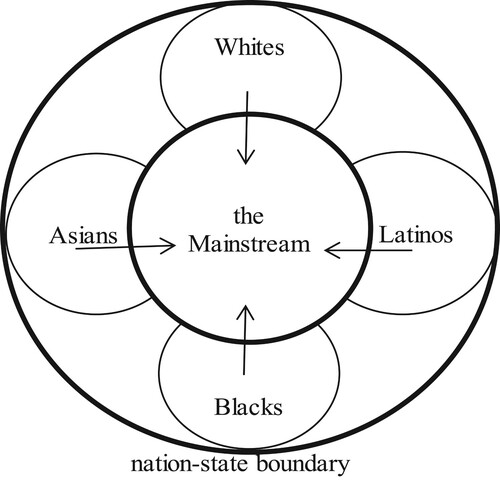

Neo-assimilation theory, the more recent modification of the classic theory since the 2000s, redefined and replaced the analytical concept of the “core group” with that of the mainstream: the institutionalized “assemblage of the social and cultural spaces where the native majority feels at home” (Alba, Beck, and Sahin Citation2018, 101). According to the theory, as intergroup relations increase over time, racial boundaries become blurred or indistinct in the mainstream (Alba and Nee Citation2003, 60). As the impact of race on life opportunities thereby decreases, and as mainstream society becomes more inclusive, assimilation will occur in the future on an individual basis (Alba and Duyvendak Citation2019). shows neo-assimilation’s conceptualization of the mainstream and its relation to racial groups within the US.

Initially, as reflected in , the theory maintained that, gradually, the mainstream will be disentangled from the core White majority. This manoeuver, informed by the presumption that racial boundaries are static and limited to the nation-state, was formulated so to allow for immigrants’ boundary crossing into the mainstream (Alba Citation2005). However, if the mainstream is the institutionalized ways of life, the theory does not explain how and why the mainstream will be disconnected from the White majority when such a disconnection did not occur during Europeans’ assimilation. Further, while the theory predicts a diminishing impact of race on group relations, it has not explained how migration flows and non-Europeans’ ethno-cultural replenishment impact the mainstream (Waldinger, Soehl, and Luthra Citation2022; Jiménez Citation2018; Tsuda Citation2014). Again, the theory has yet to explain the transnational circulation of racial meanings between the US and other geographies. This omission includes both the initial waves of importing Whiteness and non-Whiteness categories through settler-colonialism and, more recently, the inflow of immigrants who bring their origin country racial categories to the US and export it back to their home countries, albeit modified (e.g. Roth Citation2020). In response, neo-assimilationists have acknowledged that the mainstream is still anchored in Whiteness as it “reflects the social power of the white majority, which effectively controls the … opportunities for social advancement” (Alba Citation2020, 147). To date, to measure assimilation, researchers have invariably operationalized the mainstream concept as Whites’ socioeconomic achievements.Footnote5

In contrast to these iterations of assimilation theory, the early twentieth century scholars of ethnicity and assimilation theory, and also scholars of race and inequality were transnational in their thinking. Park (Citation1914, 611) himself wrote that Asian groups, for instance, face assimilation barriers not because of some intellectual shortcoming, but because the White majority associates the Asian race to “the Orient”, a geography so different from their own ancestral “White world”. Du Bois ([Citation1901] 2014, 1) also opened his analyses of the Freedmen's Bureau – a Southern government which sought to address the race problems – by arguing that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line; the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea” (italics added).

We build on this transnational tradition. A transnational perspective entails an analytical model that considers the extra-national processes of forging and sustaining social as well as symbolic allegiances, divisions, and hierarchies across national borders (Faist Citation2018; Dahinden Citation2017; Painter Citation2010). Transnational networks shape groups’ and individuals’ intra- and inter-group actions in home and destination countries (Ryan and Dahinden Citation2021). Racial categories are important parts of these transnational ties – as both dependent and independent elements. These racial categories are stretched and transferred across geographies through these transnational ties (Brubaker Citation2015: Chapter 6). These categories, albeit shaped disparately by state and non-state actors, then take on new meanings and boundaries in their new geography (Erel, Murji, and Nahaboo Citation2016).Footnote6

As social groups move across national borders, they carry their homeland’s understandings of self- and other-racialization. These groups, upon arrival in their host country, develop new experiences of racialization through intergroup relations in both host and home countries. As a result, and depending on transnational and local power relations, groups can impose their racial categories onto the host country and territory. This was the case of European colonial and imperial settlements and enforcement of new racial hierarchies in South America (Greer, Mignolo, and Quilligan Citation2008), North America (Painter Citation2010), and South Africa (Magubane Citation2022), among others. Alternatively, groups might find themselves in a subordinate situation and, thereby, struggle against the new racial categories and groups. Transnational institutional contexts such as colonialism, capitalist labour markets, and anti-discrimination laws inform the range of actions available to individuals and groups to adopt or impose senses of racial similarity and difference (Glick-Schiller Citation2018; Zolberg Citation1989).Footnote7

Under stable socio-political conditions, once social groups and racial categories overlap and establish a racialized group, the group’s racial identity is projected and associated with their geography (Loveman Citation2014; see Wimmer Citation2008 on boundary stability).Footnote8 This racialization of the group and their geography co-occurs and coincides with the borders of political entities such as an empire or a nation-state (Foucault Citation2003). Such a “border congruence implies a much stricter definition of what pertains to the realm, and what falls outside it” (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002, 309). This imagined territorialization of race and racialization of geography, through the nation-state’s power mechanisms, implies a relational process of self- and other-racialization according to how groups perceive one another and their geographies (Balibar Citation2009). For instance, as early as the eighteenth century, European social scientist and philosophers perceived a colour line division which divided the world’s geographies and their populations: White European, Yellow Asiatic, Red Aboriginal of the Americas, and Black African (Carter Citation2008, 88).

This transnational approach to the circulation of groups and their racial meanings implies that the boundaries of racial categories such as Whiteness can shift to include or exclude different groups and geographies across time and context (Bonnett Citation2018; Goldberg Citation2009; see Sawyer and Paschel Citation2007 for a similar argument on Blackness). However, the meanings attached to the symbolic boundaries and their social groups are transnationally interrelated (Roth and Kim Citation2013). This means that if pervasive intergroup interactions generate major changes in symbolic boundaries elsewhere and, hence, the shuffling of groups between symbolic categories, these changes will be reproduced here as well (Goldberg Citation2009). That is, national symbolic boundaries are the domesticated versions of their transnational kin and bound to extra-national geographies (Winant Citation2015; Loveman Citation2014; Desmond and Emirbayer Citation2009).

Accordingly, a transnational approach to assimilation perceives group relations as unfolding within a locality such as the nation-state but under the impact of extra- or transnational factors. On the one hand, newcomers’ and majority groups’ might initially hold disparate national and transnational racial views of the each other. Over time, group relations through socioeconomic activities and intermarriages lead to a sense of intergroup similarity. On the other hand, because these local interactions are impacted by transnational racial meanings, a thorough sense of similarity depends on harmonizing the racial status of newcomer and majority groups as well as the racial status of the host and home countries. Thus, assimilation happens to groups and their geographies “here” and “over there”. It is, logically, impossible to categorize and identify an individual or a group as White “here”, but perceive their country of origin “over there” within a non-White geography. Such a categorization requires and begets cognitive dissonance.Footnote9

Transnational assimilation and Whiteness: case studies

Formation and export from Europe

The analytical categories of race, nation, colour, and Whiteness are central to explaining Europeans’ assimilation in the twentieth century US. At the time, race and nation overlapped in the sense that, for instance, “Italian” would represent race-nationality (Guglielmo Citation2003). The Italian race-nationality, along with numerous other race-nationalities, was located within the wider European White color category. Meantime, Whiteness, an ideational or symbolic status, was reserved for an exclusive subset of groups within the European White colour. That is, only the Anglo-Saxon aristocrats were considered to embody Whiteness in Europe. Arendt (Citation1944, 58) reviews the work of Arthur de Gobineau to underline that racial thinking of the time proposed that only “a ‘race of princes’” denoted Whites and Whiteness. Whiteness was initially a status which reflected a combination of religion, class, and a perceived aristocratic lineage. Whiteness was the symbolic lineage of kings but not a biological breeding group (Hochman Citation2019, 1248).

Based on their understanding of race-nation, colour, and Whiteness, in eighteenth century, Europeans divided the world’s geographies and populations into four colour categories of White, Black, Yellow or Asian, and Red or, more recently, Latino. All European race-nations were located on the White side of the colour line. Yet, a three-tier ranking system divided White into three categories (Fox and Guglielmo Citation2012; Higham Citation1955). The races of North and North-Western Europe belonged to the Nordic category as the descendant of the superior Teutonic people. The central European races were assigned to the Alpine category which was somewhat inferior to the Nordic category. The south-eastern Europeans as well as the Irish were assigned to the inferior Mediterranean category because of their darker skin colour and similarities with North African and Middle-Eastern race-nations (Bertossi, Duyvendak, and Foner Citation2021; Perlmann Citation2018, 39 divides this category into Iberian and Slavic categories and locates Jewish groups into the latter). Although the wider White colour category was bound to the European continent and populations, it soon became a self- and other-categorization tool with the advent of colonialism and imperialism beyond the European borders.

By the peak of European imperialism, the English ruling class and other Western European colonial powers found themselves as a demographic minority versus the populations they encountered in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (Horne Citation2018). To maintain demographic and political power, the White elite used to strategies: expanding Whiteness to working-classes and keeping the non-European populations out of Whiteness through colonialism and slavery. Accordingly, on the one hand, by the early twentieth century, the English elite began to conflate class Whiteness, Anglo-Saxon race, and nationalism (Miles and Torres Citation1999). This new conflation of race-nationality with class allowed some of the working-classes to access and join Whiteness through racial-national identification and foreclosed a cross-racial alliance against the elite Whiteness (Roediger Citation1999). The Anglo-Saxon elite asserted that “the ‘best stock’ of the working class had long since climbed upward. Thus the [elites’ Whiteness] racial connection to the masses could be claimed to be existent” (Bonnett Citation2003, 327). The expansion of the idea of Whiteness to include the lower classes and the entirety of the nation turned the national population into a “natural aristocracy” (Arendt Citation1944, 63), into “White solidarity” (Magubane Citation2022). This newly formulated European Whiteness was exported to and consolidated in the “new world” by settler-colonial pioneers (Rogoff Citation1997).

Then, on the other hand, while Whiteness became accessible to the European working-classes, the populations who living in or connected to non-European geographies were put into a Black category away from Whiteness (Painter Citation2010). Whiteness was now conceived vis-à-vis the Black or non-White populations as a socio-political category. Yet, to maintain its class status on a transnational level, the pan-European Whiteness used extractive colonialism in South America, settler-colonialism in North America, and slavery in Africa and North America (Horne Citation2018; Roediger Citation1999). Maintaining the Whiteness status is a fraught process of extracting and accumulating capital and populations without tainting Whiteness. Horne (Citation1999, 441), for instance, examines one such example when imperial powers had to decide whether to interfere in Hawaii and “risk polluting “Whiteness” by gobbling up this island kingdom or should it [US] intervene on behalf of the settlers precisely to preserve “white supremacy”?”. This socio-class distance, the outcome of ongoing investment in Whiteness (Lipsitz Citation1995), is today visible in the divide between the Global North and South (Faist Citation2018).

Consolidation and export from the US

In the US, the Anglo-American settlers perceived themselves as the forerunners of the Anglo-Saxons, a superior race due to their Teutonic and Protestant heritage. Some even sought to sustain a union with the English so as to create an Anglo-Saxon racial utopia which adopted the American constitution as its political centrepiece (Bell Citation2020). Such racial utopian thinking was reflected in federal census forms which, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, categorized the population into “free Whites”, “free colored”, and “slaves”. The main colour divisions were, then, that of Whites versus non-Whites. But this did not mean that all Whites were always perceived as equal fellow Americans. Two elements led to Alpine and Mediterranean European immigrants’ inclusion in Anglo-Saxon Whiteness: socio-legal recognition of Europe as a uniformly White geography for naturalization purposes in the US, and immigrants’ transnational sociopolitical activism.

First, the twentieth century changes in the boundary of Whiteness in Europe, its accessibility to the lower classes and the non-Anglo Saxons, found their way to the US as well. These changes in racial classifications directly informed immigration and citizenship policies in the US. That is, until the early twentieth century, the imagined colour status of immigrants’ country of origin would determine their eligibility to immigrate to the US and to naturalize. For instance, immigration laws and policies made explicit distinctions between non-European populations and “‘white’ persons from ‘white countries’” (Ngai Citation2014). Immigration quotas were assigned in favour of European migrants (Higham Citation1955). More importantly for the first-generation immigrants, up until the mid-twentieth century, only Whites could obtain citizenship (Fox and Bloemraad Citation2015).Footnote10 To comply with naturalization laws, citizenship applicants had to prove their deservingness to be American, to be included in Whiteness, by verifying that they originated from a White geography. For instance, Armenians would claim European ethnicity and emphasize their Christian heritage as opposed to non-European populations and religions (Maghbouleh Citation2017, 19). Alpine and Mediterranean European immigrants’ citizenship applications were only occasionally disputed. In those rare instances, both the applicants and the judges would agree that these groups were now White in Europe and, thereby, White in the US and eligible for naturalization (Fox and Bloemraad Citation2015; Roediger Citation1999). In 1923, one important court ruling put an end to any further legal quarrels over Europeans’ Whiteness. In US v. Thind (Supreme Court Citation1923: 261 US 204), the Supreme Court refused an Indian immigrant’s citizenship application by issuing a verdict parts of which read:

The average man knows perfectly well that there are unmistakable and profound differences [between Europeans and non-Europeans]. Immigrants from Eastern, Southern and Middle Europe, among them the Slavs and the dark-eyed, swarthy people of Alpine and Mediterranean stock … were received as unquestionably akin to those already here and readily amalgamated with them. (italics added)

This and other such rulings drew on and also reinforced a wholesale difference between European and non-European populations. The mythical European colour divisions of eighteenth century, the imagined racial status of immigrants’ country of origin, were now codified into US citizenship law. Europeans’ homelands and, by extension, the European populations were legally Whitened. Meantime, those originating from outside of continental Europe were still struggling to prove the Whiteness of their country of origin for naturalization purposes. At last, the implementation of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 prohibited racial discrimination in accessing US citizenship. These socio-legal inroads to citizenship and inclusion in Whiteness are inherently transnational and, therefore, add a different perspective to the contentions that socioeconomic mobility and intermarriage were the only determinants of assimilation in the US.

Further, Europeans’ cross-Atlantic sociopolitical activism too reflects the transnational nature of their trajectories. To consolidate their inclusion in transnational Whiteness, Eastern and Southern Europeans engaged in sociopolitical activism in the US and Europe. For instance, at the turn of twentieth century, within Italy there were two groups. One was perceived to be White European in the North and another, in the South, was perceived to be dark-skinned criminals and semi-European – there was a racial “Southern Question” in Italy (D'Agostino Citation2002, 321; see Guglielmo Citation2003, 24 on the southerners’ perceived “negroid ancestry”). As early as the 1910s, this racial division in the country of origin reached the English-speaking audience in the US, was translated into racial terms, and led the American policymakers to question where Italians belonged on the European colour line and, thereby, eligible for migration to the US (Fox and Guglielmo Citation2012; D'Agostino Citation2002). This racial-national stigma complicated Italians’ precarious status who were already under suspicion due to their Catholicism. Anglo-Saxon Whites feared that, since the Irish Catholics were becoming Americanized, the Vatican was now sending the Italian Catholics to threaten Protestantism in the US (Higham Citation1955, 180).

Two developments helped the Italians move into transnational Whiteness. First, between the two World Wars Italian governments as well as the American Italian diaspora carried out series of political reforms aimed at reconciling the Northern and Southern racial divide. For instance, from 1928 to 1935, the Italian consul general in Chicago would pay public visits to both Northern and Southern Italian communities and honour the “Sicilian American achievements at their Catholic parish” (D'Agostino Citation2002, 338). The Italian activists would also communicate this diasporic unity to their origin country while also reminding the US policymakers that, under the Fascist Mussolini regime, criminal behaviour in Southern Italy was eliminated and that Northern and Southern Italians were of the same racial background (D'Agostino Citation2002). While these trans-Atlantic racial revisions began to alleviate Italian ethnics’ racial status in the US, the effects of Catholicism also began to subside. During WWI, the US Whites shifted their anti-foreigner and anti-Catholicism sentiments into an anti-Kaiser sentiment (Higham Citation1955, 201). Next, during WWII, European ethnics including Italians – the hyphenated-Americans – fought along the White Protestants against the German and Italians regimes. Their loyalty to the US in the war against Nazism over race and democracy ended their exclusion from Whiteness in the US (Guglielmo Citation2003, 121; Perlmann and Waldinger Citation1997, 907). Glazer and Moynihan (Citation1970, 203–204) observed that in post-WW II era, Americans believed everyone was to enjoy religious freedoms and that the American Catholic Church was itself a force in assimilating European ethnics into American Catholicism, a component of transnational Christian Whiteness. These two developments led to “twilight of ethnicity among American Catholics of European ancestry” (Alba Citation1981) and, by extension, Italians’ inclusion in Whiteness. By the mid-twentieth century, all Italians self-identified as White on the colour option in their citizenship applications (Guglielmo Citation2003, 8).

Similarly, the Irish-Americans were among the first groups to consolidate their colour status within Whiteness so as to make themselves indistinguishable from Protestant Anglo-Saxons (Ignatiev Citation2012; Park Citation1914). To claim Whiteness in the US they relied on a combination of factors including the subsiding anti-Catholic sentiments, residential proximity and inter-marriage with Anglo-Saxons, and significant participation in national politics (Alba, Raboteau, and DeWind Citation2009). In particular, Irish-Americans, to join the ruling Anglo-Saxon Protestant Whites, gave political primacy to racial identity instead of focusing on their working-class status and an alliance with Blacks (also Guglielmo Citation2003, 169 on Italians’ political actions to claim Whiteness). Such White solidarity was not necessarily a peaceful process. Irish-Americans participated in Black lynching, slavery, and property theft to avail themselves of labels such as “smoked Blacks” and to pave up their up into Whiteness status (Ignatiev Citation2012; see Du-Bois ([Citation2001] 2001) on the impact of Irish racism on holding back Blacks from political and economic arenas).

Then, in Europe, they built on their newly found Whiteness in the US to promote a sense of Irish nationalism among their contemporaries in Ireland and to position the Irish nation within Whiteness (Lune Citation2020; Garner Citation2004). They emphasized their gains in the US as a sign but also incentive for their membership in transnational Whiteness. Such gains included racial distance from Blacks, their membership in the Democratic Party, and their voting and property rights (King-O’Riain Citation2021). They also underlined the transformation of Catholicism from a dividing factor into a “new American Catholicism” and, thereby, the inclusion of the Irish into Christian Whiteness (Glazer and Moynihan Citation1970, 204); (see Walter Citation2011 on similar activism trends among Irish immigrants in Britain). The combination of their successful claim to Whiteness in the US and progressive politics in the UK, at the expense of the non-White working-classes, helped position the Irish in transnational Whiteness.

Other groups such as Eastern European immigrants followed suit. Groups such as the Slovaks and Poles drew on their European heritage and practice of Christianity to position themselves within Whiteness in both Europe and the US. In the early twentieth century, philosophers and religious leaders from these race-nations travelled to and from the US and engaged in a transnational manoeuver of self- and other-racialization. In their publications, informed by historical religio-racial imaginaries (Westerduin Citation2020; Jansen and Meer Citation2020), they wrote that the American Jews’ racial status and living conditions resembled that of the African Americans, destitute and segregated from the Anglo-Saxons and other European immigrants. They contrasted Christians with Jews, marking the latter as distinct and separate from the Slavic races. Through this anti-Black and anti-Jewish racialization process (Roediger Citation1999), Slavs sought to gain access to Christian European Whiteness. This racialization relied on “the perspective of the democratic United States” (Szabó Citation2020, 278). The (il)logic was that, if in the democratic US the Jews and African Americans belonged to the same Black category (Rogoff Citation1997), then there was indeed racial distance between White Christian Slavs and the coloured Jews (Nirenberg Citation2013). Eastern Europeans positioned themselves within Whiteness through “a transnational or, more precisely, a global (transatlantic)” process of marking the Jews as non-White and non-European and Whitening the Eastern European populations and geographies (Szabó Citation2020, 283).

As a result, the inclusion of the entirety European geographies and populations in Whiteness in the US and Europe meant that, by the 1940s, and at the expense of non-Whites (Ignatiev Citation2012; Roediger Citation1999), Whiteness began to expand beyond its initial association with Anglo-Saxons aristocracy. This transnational expansion of Whiteness enabled the European immigrants, the hyphenated Americans, to become full members of Whiteness (Painter Citation2010). Further, the alliance among European nations and the loyalty of European immigrants to the US army consolidated White solidarity (also Fox and Guglielmo Citation2012, 334 on the disappearance of racial divides among Nordic Anglo-Saxons, Alpines, and Mediterraneans). This Whiteness expansion meant that the US mainstream now accommodated religious and ethnic groups such as Southern Europeans, Catholics, and Jews. This elasticity of Whiteness gives the impression that boundary expansion, but also contraction (Abascal Citation2020), remains a possibility.

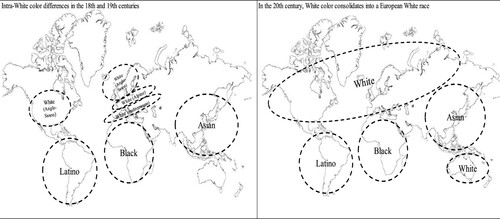

However, Whiteness, race, and coloured politics became taboos after the Second World War and subsequent human rights movements (Banton Citation2014; Miles and Torres Citation1999). As early as the 1960s, several laws and international declarations such as the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination dropped the divisive language of colonialism and colour lines. Instead, race, also a dividing factor until then, was transformed into a tool to achieve equality, to fight against racial discrimination (Banton Citation2014). The language of race, widely popular in the US during the Civil Rights movements, became a transnational language (Miles and Torres Citation1999). This shift from colour to race led to the dissolution of the three-tier differences within the White colour by unifying all European race-nations into a transnational White race.Footnote11 shows this White colour dissolution and, then, the White racial unification.

Figure 2. Whiteness as an elastic boundary: transnational changes in Whiteness from the 18th to twentieth century.

shows the gradual changes in the colour and racial category boundaries from the 18th to 20th centuries. As shown on the left, initially, all European race-nations were within the European White colour line but divided into three groups. Over time, the differences between the Nordic, Alpine, and Mediterranean Whites subsided. European immigrants’ transnational practices of Whitening their homelands vis-à-vis the Anglo-American Whiteness strengthened their national assimilation in the US Such efforts coincided with the geopolitical consolidation of European Whiteness as a response to the demographic size of the coloured people and geographies. As shown on the right side of , the combination of these sociopolitical processes led to the unification of groups within the White colour into a post-WWII White race.Footnote12

To further illustrate, we briefly consider the Whiteness of Iranian and Mexican immigrants. These groups occupy a liminal relationship to Whiteness. Until the mid-twentieth century, Iranians could claim the Whiteness of their homeland and, therefore, eligibility for naturalization in the US. They did so by highlighting their linguistic and, thereby, ethnic proximity with the Indo-European cultures. They also emphasized their Zoroastrian Persian heritage so to distance themselves from the Arabian Peninsula and the Ottoman-ruled Muslim world (Karimi and Bucerius Citation2018). The Persian nation was, at times, used by non-Iranian groups to claim Whiteness. For instance, some Indian citizenship applicants would claim Whiteness via an Iranian ethnicity dissociated from non-White India. In a citizenship court ruling, for example, the judge accepted an Indian applicant’s right to naturalization by arguing that “the emigration of Parsi people from Iran to India was the movement of a white people to a brown place” (Maghbouleh Citation2017, 22 italics added). Middle Easterners’ Whiteness, including Iranians, was reflected in the Census Bureau’s 1978 definition of White as “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa” (US Census Bureau Citation2017). Yet, events since then, including the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the 1979–1981 Hostage Crisis, and 9/11 have pushed Iranians and Middle Easterners back into non-Whiteness. Their status as White is now, once again, up for debate.

A similar process of liminal inclusion into and out of Whiteness has happened to Mexican-Americans. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave Mexicans who lived in the US territory the right to citizenship. Until the 1970s they were, supposedly, counted in the Census as Whites (Snipp Citation2003). Yet, in practice, by the early twentieth century, Mexican-Americans were perceived as “Indians” or as a mixed-race group with Indian and Spanish blood (Gross Citation2007). Their ancestral geographies were imagined as non-White lands of the “Amerindian or negroid … the ethnically colored man’s land” (Stoddard Citation1920 cited in Fox and Guglielmo Citation2012, 354 italics added). With increasing immigration from Central and South America, these legal and everyday imagined racial distinctions became more salient. Yet, in contrast to the European groups who lobbied their homeland populations for a concerted campaign to join Whiteness, the Mexican government, and many other South American governments, promoted a different set of racial ideas. With the heightened threat of US imperialism in Central and South America, more and more nation-states in the region, including Mexico, championed an anti-imperialist continental racial alliance. To resist Americanization, these states contrasted their Latin-Mestizaje race with an imperialist Anglo-Saxon race (Gobat Citation2013, 1367). Such racial policies and antagonisms in the countries of origin, then, create a disconnect between Mexican and other Latino groups’ assimilation efforts in the US. That is, these “immigrant” groups push towards joining Whiteness in the US while their home countries pull away from transnational Whiteness (see Mora Citation2014 on Latino activists’ push for “Hispanic” census category). Considering this difference in the imagined transnational racial status of the two continents, it is not surprising that the racial status of Latino groups in the US is still debated (Telles Citation2018).

Conclusion

National socioeconomic, spatial, and linguistic similarities with the majority group determine half of the assimilation process. The other half is transnational racial inclusion in Whiteness. In the US, Eastern and Southern Europeans made their way to Whiteness by consolidating the idea that their home cultures and countries are part of a White Euro-Atlantic world. This transnational process of Whitening has led to a sense of White solidarity in the moral-geographical “triple conflation of White = Europe = Christian[ity]” (Bonnett Citation1998, 1038; Garner Citation2007). Because the ideational-geographical boundary of Whiteness has been stable over the past century, there exists little interest in scholarship on European newcomers’ assimilation into the White majority group. As members of transnational Whiteness, these newcomers are already White. In contrast, non-European groups remain outside of transnational Whiteness and hence at the centre of US assimilation research. A main contribution of the transnational reading of assimilation process is to draw attention to Whiteness boundary expansion and the majority groups’ boundary expansion actions (see Karimi and Wilkes Citation2023).

Further, instead of taking the nation-state as the unit of analysis, a transnational assimilation approach begins by defining the social groups and their respective racial categories at a transnational level. The current forms of racial boundaries and their imagined associations with the world’s geographies inform the transnational perception of social groups. In the US, for instance, there currently exist several racial minorities. These groups’ racial status is simultaneously associated with their respective geographies in South America, Africa, or Asia. Whiteness is also a category whose boundaries traverse outside the US. Then, the transnational approach to assimilation predicts that assimilation depends on intergroup relations such as intermarriages and socioeconomic engagements and on the transnational harmony between the imagined racial status of the country of origin and the host country. Put differently, assimilation occurs only when newcomer and majority groups establish a sense of racial similarity within the national borders and at the transnational level.

This transnational approach to assimilation is suggestive of two major implications for future research. Depending on intergroup relations and assimilation aspirations, non-Europeans’ inclusion into the White majority will depend on transnational shifts in the boundary of Whiteness. We hypothesize that, for instance and regardless of skin tone differences, Latinos’ assimilation will not materialize if they gain socioeconomic mobility while the White majority in the US imagines their Latin American homelands as non-White. In another instance, the global rise of China as an economic-political adversary to the Euro-Atlantic West, can, we hypothesize, pose a challenge to Asian-Americans’ assimilation and probable inclusion in the White majority. This is because, in the absence of political harmony and alliance, both the majority and the minority groups can translate political rivalry into racial dissimilarity at national and transnational levels.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Anna Triandafyllidou for their insightful comments on the earlier drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank Dr. Solomos and the two anonymous reviewers for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 European immigrants comprise 13 per cent of yearly new arrivals in the US (Pew Research Center Citation2020).

2 In different contexts, different local religions, languages, and philosophies engender this symbolic reference group of Whiteness. In other words, the category of Whiteness exists in different cultures but refers to disparate social groups (Bonnett Citation1998).

3 The discussions presented here draw on the US context but, we believe, our argument on assimilation and country of origin vis-à-vis transnational Whiteness is also pertinent to the European context where intergroup relations are analysed through “integration” lens (Favell Citation2022; Lentin Citation2020). For examples on operationalizing the correlation between origin countries’ racial status and upward mobility opportunities in Europe see Volume 47, 2021 – Issue 6 in Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

4 In 1950 census, the category of colour was replaced with the term race. This is, then, reflected in classic theory’s use of color and the newer theories’ use of race to refer to group divisions.

5 Other scholars also offer commentaries on assimilation theories. Jung (Citation2009) underlines the theory’s ethnocentrism as well as its conceptual limitations. Treitler (Citation2013) points to the practical limits of the theory. She uses the metaphor of a chest of racial drawers to say that, even though ethnic groups might be able to move across the drawers, the racial chest remains intact. We build on these works to address the methodological nationalism of assimilation theory.

6 In the anthropological literature, this transnational circulation and national localization of categories is “typically expressed through the notion of glocalization” (Roudometof Citation2019, 803).

7 The transnational turn in migration studies acknowledges immigrants’ transnational practices in home and destination countries (e.g., Karimi Citation2020; Waldinger Citation2015; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011).

8 This process of racializing the nation and geography finds its parallel in the discussions of gendering the nation (Hill-Collins Citation1998).

9 A transnational lens does not presume methodological groupism whereby “individuals of the same racial background … represent groups of shared political destiny” (Wimmer Citation2015, 2194). We, 80, 8033 acknowledge that intra-group diversities lead to different pathways to assimilation. Schut (Citation2021), for instance, shows the intra-Latino differences in racial identification based on their birth country. Those who identify with indigeneity in their home countries such as Bolivia and Columbia are more likely to identify as Hispanic in the U.S. Those who identify with “Latin or Saxon, that is, European” in (Gobat Citation2013, 1351), 1351 for instance, Argentina and Chile, are more likely to identify as White in the US.

10 For all immigrant groups, US-born children were citizens by virtue of the 14th Amendment. Similarly, as a result of the 1870 Naturalization Act, Blacks including African Americans and African immigrants had access to citizenship.

11 As color lines found their expression in racial boundaries, a new ethnic dimension was added to social relations (Banton Citation2014; Ngai Citation2014). Phenotype characteristics such as (skin) colour were relegated to race categories, while cultural contents that demarcated group boundaries were now classed as ethnicity. European immigrants were now symbolically identified not with race-nations but with their ethnicity and co-ethnic groups (Gans Citation1979). Put simply, the long-established White, Black, Red, and Yellow colour categories from the 18th century now became race categories in the American context. Racial groups formerly identified within the colour lines became ethnic groups.

12 Instead of subsuming all countries into the imagined racial status of each continental geography, each country deserves its own independent attention. For instance, Brazil’s racial imaginary does not neatly fit into the Latino category associated with Latin America. Other similar cases would include Haiti, South Africa, and the Philippines. Further, to date, Indigenous Peoples are largely absent from the assimilation literature.

References

- Abascal, M. 2020. “Contraction as a Response to Group Threat: Demographic Decline and Whites’ Classification of People Who Are Ambiguously White.” American Sociological Review 85 (2): 298–322. doi:10.1177/0003122420905127.

- Alba, R. D. 1981. “The Twilight of Ethnicity among American Catholics of European Ancestry.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 454 (1): 86–97.

- Alba, R. 2005. “Bright vs. Blurred Boundaries: Second-Generation Assimilation and Exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (1): 20–49. doi:10.1080/0141987042000280003.

- Alba, R. 2007. “Whiteness Just Isn’t Enough.” Sociological Forum 22 (2): 232–241. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2007.00018.x.

- Alba, R. 2009. Blurring the Color Line. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Alba, R. 2020. The Great Demographic Illusion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Alba, R., B. Beck, and B. Sahin. 2018. “The U.S. Mainstream Expands – Again.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1): 99–117. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1317584.

- Alba, R., and J. Duyvendak. 2019. “What About the Mainstream? Assimilation in Super-Diverse Times.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 105–124. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1406127.

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Alba, R., A. J. Raboteau, and J. DeWind, eds. 2009. Immigration and Religion in America. New York: NYU Press.

- Anderson, B. 2006. Imagined Communities. London: Verso Books.

- Arendt, H. 1944. “Race-thinking Before Racism.” The Review of Politics 6 (1): 36–73. doi:10.1017/S0034670500002783.

- Balibar, E. 2009. “Europe as Borderland.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27 (2): 190–215. doi:10.1068/d13008.

- Banton, M. 2014. “Superseding Race in Sociology.” In Theories of Race and Ethnicity, edited by Karim Murji and John Solomos, 143–161. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, D. 2020. Dreamworlds of Race. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bertossi, C., J. Duyvendak, and Nancy Foner. 2021. “Past in the Present: Migration and the Uses of History in the Contemporary Era.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (18): 4155–4171. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1812275.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 1997. “Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation.” American Sociological Review 62 (3): 465–480. doi:10.2307/2657316.

- Bonnett, A. 1998. “Who was White? The Disappearance of non-European White Identities and the Formation of European Racial Whiteness.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21 (6): 1029–1055. doi:10.1080/01419879808565651.

- Bonnett, A. 2003. “From White to Western: “Racial Decline” and the Idea of the West in Britain, 1890-1930.” Journal of Historical Sociology 16 (3): 320–348. doi:10.1111/1467-6443.00210.

- Bonnett, A. 2018. “Multiple Racializations in a Multiply Modern World.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (7): 1199–1216. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1287419.

- Brubaker, R. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 21–42. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916.

- Brubaker, R. 2015. Grounds for Difference. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Carter, K. 2008. Race: A Theological Account. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Collins, P. H. 1998. “It's All In the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” Hypatia 13 (3): 62–82. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01370.x.

- Cox, O. C. 1944. “The Racial Theories of Robert E. Park and Ruth Benedict.” The Journal of Negro Education 13 (4): 452–463. doi:10.2307/2292493.

- Crowell, R., and M. Fossett. 2018. “White and Latino Locational Attainments: Assessing the Role of Race and Resources in U.S. Metropolitan Residential Segregation.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1177/2332649217748426.

- D'Agostino, P. 2002. “Craniums, Criminals, and the ‘Cursed Race': Italian Anthropology in American Racial Thought, 1861–1924.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 44 (2): 319–343. doi:10.1017/S0010417502000154.

- Dahinden, J. 2017. “Transnationalism Reloaded: The Historical Trajectory of a Concept.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (9): 1474–1485. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1300298.

- Desmond, M., and M. Emirbayer. 2009. “What is Racial Domination?” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 6 (2): 335–355. doi:10.1017/S1742058X09990166.

- Du Bois, W. B. 2001. “Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.” In Racism Essential Readings, edited by E. Cashmore and J. Jeninings, 27–34. London: SAGE Publications.

- Du Bois, W. 2014. “The Freedmen’s Bureau (1901).” In The Problem of the Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, edited by N. Chandler, 167–188. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Elgenius, G., and S. Garner. 2021. “Gate-keeping the Nation: Discursive Claims, Counter-Claims and Racialized Logics of Whiteness.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (16): 215–235. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1943483.

- Erel, U., K. Murji, and Z. Nahaboo. 2016. “Understanding the Contemporary Race–Migration Nexus.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (8): 1339–1360. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1161808.

- Faist, T. 2018. The Transnationalized Social Question. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Favell, A. 2022. The Integration Nation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Feagin, J. 2013. Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. New York: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 2003. Society Must Be Defended. New York: Picador.

- Fox, C., and I. Bloemraad. 2015. “Beyond “White by Law”: Explaining the Gulf in Citizenship Acquisition Between Mexican and European Immigrants, 1930.” Social Forces 94 (1): 181–207. doi:10.1093/sf/sov009.

- Fox, C., and A. Guglielmo. 2012. “Defining America’s Racial Boundaries: Blacks, Mexicans, and European Immigrants, 1890–1945.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (2): 327–379. doi:10.1086/666383.

- Gans, H. J. 1979. “Symbolic Ethnicity: The Future of Ethnic Groups and Cultures in America.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 2 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/01419870.1979.9993248.

- Garner, S. 2004. Racism in the Irish Experience. London: Pluto Press.

- Garner, S. 2007. Whiteness: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Glazer, N., and P. Moynihan. 1970. Beyond the Melting Pot. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Glick-Schiller, N. 2018. “Theorising Transnational Migration in Our Times: A Multiscalartemporal Perspective.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 8 (4): 201–212. doi:10.2478/njmr-2018-0032.

- Gobat, M. 2013. “The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race.” The American Historical Review 118 (5): 1345–1375. doi:10.1093/ahr/118.5.1345.

- Goldberg, D. 2009. “Racial Comparisons, Relational Racisms: Some Thoughts on Method.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (7): 1271–1282. doi:10.1080/01419870902999233.

- Gordon, M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life. Oxford: OUP.

- Greer, R., W. Mignolo, and Maureen Quilligan, eds. 2008. Rereading the Black Legend. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gross, A. 2007. “The Caucasian Cloak.” Georgetown Law Journal 95: 337–392.

- Guglielmo, T. 2003. White on Arrival. Oxford: OUP.

- Haller, W., A. Portes, and Scott M. Lynch. 2011. “Dreams Fulfilled, Dreams Shattered: Determinants of Segmented Assimilation in the Second Generation.” Social Forces 89 (3): 733–762. doi:10.1353/sof.2011.0003.

- Higham, J. 1955. Strangers in the Land. New York: Athenaeum.

- Hochman, A. 2019. “Racialization: A Defense of the Concept.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (8): 1245–1262. doi:10.1080/01419870.2018.1527937.

- Horne, G. 1999. “Race from Power: U.S. Foreign Policy and the General Crisis of "WhiteSupremacy".” Diplomatic History 23 (3): 437–461. doi:10.1111/0145-2096.00176.

- Horne, G. 2018. The Apocalypse of Settler-Colonialism. New York: NYU Press.

- Ignatiev, N. 2012. How the Irish Became White. New York: Routledge.

- Jansen, Y., and N. Meer. 2020. “Genealogies of ‘Jews’ and ‘Muslims’: Social Imaginaries in the Race–Religion Nexus.” Patterns of Prejudice 54 (1-2): 1–14. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2019.1696046.

- Jiménez, T. 2017. The Other Side of Assimilation. Los Angles: Univ of California Press.

- Jiménez, T. R. 2018. “Why Replenishment Strengthens Racial and Ethnic Boundaries.” In Social Stratification, edited by D. Grusky and K. Weisshaar, 740–746. London: Routledge.

- Jung, M. K. 2009. “The Racial Unconscious Of Assimilation Theory.” Du Bois Review 6 (2): 375–395.

- Karimi, A. 2020. “Refugees’ Transnational Practices: Gay Iranian Men Navigating Refugee Status and Cross-Border Ties in Canada.” Social Currents 7 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1177/2329496519875484.

- Karimi, A., and S. M. Bucerius. 2018. “Colonized Subjects and Their Emigration Experiences. The Case of Iranian Students and Their Integration Strategies in Western Europe.” Migration Studies 6 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1093/migration/mnx033.

- Karimi, A., and R. Wilkes. 2023. “Assimilated or the Boundary of Whiteness Expanded? A Boundary Model of Group Belonging.” The British Journal of Sociology, 1–16. online first. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12994.

- King-O’Riain, R. C. 2021. “How the Irish Became More Than White: Mixed-Race Irishness in Historical and Contemporary Contexts.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (4): 821–837. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1654156.

- Lentin, A. 2020. Why Race Still Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Levitt, P., and D. Lamba-Nieves. 2011. “Social Remittances Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2011.521361.

- Lipsitz, G. 1995. “The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: Racialized Social Democracy and the "White" Problem in American Studies.” American Quarterly 47 (3): 369–387. doi:10.2307/2713291.

- Loveman, M. 1999. “Is "Race" Essential?” American Sociological Review 64 (6): 891–898. doi:10.2307/2657409.

- Loveman, M. 2014. National Colors. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lune, H. 2020. Transnational Nationalism and Collective Identity among the American Irish. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Maghbouleh, N. 2017. The Limits of Whiteness. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Magubane, Z. 2022. “Whiteness and Racial Capitalism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, doi:10.1080/01419870.2022.2143718.

- Miles, R., and Torres, R. 1999. “Does Race Matter?, edited by Vered Amit-Talai and Caroline Knowles, Eds. Re-Situating Identities, 65–73. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Mora, C. 2014. Making Hispanics in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nancheva, N., and R. Ranta. 2021. “Do They Need to Integrate?” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 1–21. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1977363.

- Ngai, M. 2014. Impossible Subjects. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Nirenberg, D. 2013. Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition. New York: Norton & Company.

- Obinna, D., and M. Field. 2019. “Geographic and Spatial Assimilation of Immigrants from Central America's Northern Triangle.” International Migration 57 (3): 81–97. doi:10.1111/imig.12557.

- Omi, M., and H. Winant. 2014. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge.

- Painter, N. I. 2010. The History of White People. London: Norton & Company.

- Park, R. 1914. “Racial Assimilation in Secondary Groups with Particular Reference to the Negro.” American Journal of Sociology 19 (5): 606–623. doi:10.1086/212297.

- Perlmann, J. 2018. America Classifies the Immigrants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Perlmann, J., and Roger Waldinger. 1997. “Second Generation Decline?.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 893–922. doi:10.2307/2547418.

- Pew Research Center. 2020. Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Accessed on January 8, 2022 at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/.

- Portes, A., and R. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies. Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96. doi:10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Qian, Z., and D. Lichter. 2007. “Social Boundaries and Marital Assimilation: Interpreting Trends in Racial and Ethnic Intermarriage.” American Sociological Review 72 (1): 68–94. doi:10.1177/000312240707200104.

- Qian, Z., and Y. Qian. 2020. “Generation, Education, and Intermarriage of Asian Americans.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (14): 2880–2895. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1585006.

- Roediger, D. 1999. The Wages of Whiteness. London: Verso.

- Rogoff, L. 1997. “Is the Jew White?: The Racial Place of the Southern Jew.” American Jewish History 85 (3): 195–230. doi:10.1353/ajh.1997.0025.

- Roth, W. 2020. Race Migrations. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Roth, W., and K. Kim. 2013. “Relocating Prejudice: A Transnational Approach to Understanding Immigrants’ Racial Attitudes.” International Migration Review 47 (2): 330–373. doi:10.1111/imre.12028.

- Roudometof, V. 2019. “Recovering the Local: From Glocalization to Localization.” Current Sociology 67 (6): 801–817. doi:10.1177/0011392118812933.

- Ryan, L., and J. Dahinden. 2021. “Qualitative Network Analysis for Migration Studies.” Global Networks 21 (3): 459–469.

- Sawyer, M. Q., and T. S. Paschel. 2007. “We didn't Cross the Color Line, the Color Line Crossed us.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 4 (2): 303–315. doi:10.1017/S1742058X07070178.

- Schinkel, W. 2017. Imagined Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schut, R. A. 2021. “New White Ethnics” or “New Latinos”?” International Migration Review 55 (4): 1061–1088.

- Snipp, C. M. 2003. “Racial Measurement in the American Census: Past Practices and Implications for the Future.” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (1): 563–588. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100006.

- Stoddard, Lothrop. 1920. The Rising Tide of Color against White World Supremacy. New York: Scribner’s Sons.

- Supreme Court. 1923. United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204. Accessed on January 8, 2022, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/261/204/.

- Szabó, M. 2020. “Catholic Racism and Anti-Jewish Discourse in Interwar Austria and Slovakia: The Cases of Anton Orel and Karol Körper.” Patterns of Prejudice 54 (3): 258–286. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2020.1759862.

- Telles, E. 2018. “Latinos, Race, and the U.S. Census.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677 (1): 153–164. doi:10.1177/0002716218766463.

- Treitler, V. B. 2013. The Ethnic Project: Transforming Racial Fiction into Ethnic Factions. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tsuda, T. 2014. “‘I'm American, not Japanese!’: The Struggle for Racial Citizenship among Later-Generation Japanese Americans.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (3): 405–424. doi:10.1080/01419870.2012.681675.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2017. “About the Topic of Race.” Accessed on January 8, 2022 at https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html.

- Waldinger, R. 2015. The Cross-Border Connection. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Waldinger, R., T. Soehl, and R. R. Luthra. 2022. “Nationalizing Foreigners.” Nations and Nationalism, 1–19. doi:10.1111/nana.12806.

- Walter, B. 2011. “Whiteness and Diasporic Irishness: Nation, Gender and Class.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (9): 1295–1312. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2011.623584.

- Westerduin, M. 2020. “Questioning Religio-Secular Temporalities: Mediaeval Formations of Nation, Europe and Race.” Patterns of Prejudice 54 (1-2): 136–149. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2019.1696050.

- Wimmer, A. 2008. “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (4): 970–1022. doi:10.1086/522803.

- Wimmer, A. 2015. “Race-centrism: A Critique and a Research Agenda.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (13): 2186–2205. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1058510.

- Wimmer, A., and N. Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334. doi:10.1111/1471-0374.00043.

- Winant, H. 2015. “Race, Ethnicity and Social Science.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (13): 2176–2185. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1058514.

- Zhou, M. 1997. “Segmented Assimilation: Issues, Controversies, and Recent Research on the New Second Generation.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 975–1008. doi:10.1177/019791839703100408.

- Zhou, M., I. I. I. Bankston, and C. L. 2020. “The Model Minority Stereotype and the National Identity Question: The Challenges Facing Asian Immigrants and Their Children.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43 (1): 233–253. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1667511.

- Zolberg, A. R. 1989. “The Next Waves: Migration Theory for a Changing World.” International Migration Review 23 (3): 403–430. doi:10.1177/019791838902300302.