?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study aims to identify rental discrimination on the Flemish rental housing market in Belgium, taking the intersectional nature of discrimination into account. Most discrimination studies focus on unequal access based on one individual discrimination ground. This practice eludes the context of the other discrimination grounds in which rental discrimination occurs and neglects the intersectional nature of discrimination. We therefore conducted 8.245 correspondence tests in almost all municipalities in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. We apply an intersectional lens, by considering the relation and interaction between gender (male/female), ethnic origin (Moroccan/Polish) and the homogeneity of names (homogenous/mixed). We find four strata of rental discrimination, in which Moroccan female rental candidates with a homogenous name experience most discrimination, indicating that multiple categorical identities enforce each other. Without a full intersectional approach, these layered patterns of exclusion would have been hidden behind the bold boundaries of ethnic or gender categorizations.

Introduction

Discrimination and unequal access to housing remain major sources of inequality in our modern-day society. Although the level of discrimination varies strongly between countries and contexts (Auspurg, Hinz, and Schmid Citation2017), the general pattern is still one of severe disadvantage for more vulnerable groups (Auspurg, Schneck, and Hinz Citation2019; Flage Citation2018). Besides individual consequences of rental discrimination – like poorer access to employment, education or limited labour mobility (Squires Citation2007) – there are larger societal and residential inequalities at stake too (MacDonald, Galster, and Dufty-Jones Citation2018).

Most discrimination studies focus on unequal access on the basis of one individual discrimination ground, like ethnic origin (Quillian, Lee, and Honoré Citation2020), sexual orientation (Flage Citation2021) or disability (e.g. Fumarco Citation2017; Verhaeghe, Van der Bracht, and Van de Putte Citation2016), sometime, but only rarely in combination with gender (Flage Citation2018). However, considering merely one ground of discrimination when measuring rental discrimination is to artificially break a candidates’ characteristics down and reduce it to a single feature. This eludes the context of the other discrimination grounds in which discrimination on the housing market is occurring and neglects the intersectional nature of discrimination. This might lead to an underestimation of overall levels of rental discrimination, as multiple personal features may coexist and even reinforce the level of discrimination (Collins Citation2015; Crenshaw Citation1989). It is becoming increasingly apparent that dynamics of discrimination are only to a limited extent understood by uncovering simple and dualistic links between two social groups (Ruwanpura Citation2008).

Several theoretical perspectives have been developed on the intersection of discrimination grounds across multiple domains (Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall Citation2013), but these have hardly been linked to experimental evidence of discrimination (Di Stasio and Larsen Citation2020). In this study, we present the results of a field experiment on housing market discrimination, considering intersections between three major discrimination grounds: ethnic origin, gender and the homogeneity of names (first and last name signalling the same or a different ethnic origin). We aim to make several contributions to the literature. First, we consider multiple forms of intersectionality in our data collection and analysis. Building on previous studies, we integrate a full intersectional model in design and analysis. Analysing two-, and three-way interactions between ethnic origin, gender and the homogeneity of names with multilevel analysis on invitation rates, we provide an overview of all (90) possible interactions between three major candidate characteristics.

Second, we aim to add to scientific knowledge by measuring discrimination towards fictious rental candidates with homogenous names or mixed names. Whereas previous experimental research predominantly used homogenous names as a proxy for ethnic origin (first and last name signal the same ethnic origin), we assess whether candidates with a mixed name (first and last name proxy for a different ethnic origin) experience differential treatment on the rental housing market. The combination and interaction with ethnic origin and gender provide us with a clearer understanding why treatment would differ between candidates with homogenous names and candidates with a mixed name. With societies becoming increasingly superdiverse (Meissner Citation2015), it is worth considering whether there is a different treatment towards people with mixed names as compared to people carrying ethnic homogenous names, as well as how this depends on their specific ethnic origin and gender.

Third, we examine rental discrimination in almost all municipalities of Flanders, the northern region of Belgium. In total 16.490 enquiries for rental, dwellings were made. This allows us to establish a comprehensive view of rental discrimination within a larger context and enables us to extrapolate results to a broader framework. This is the first paper to measure discrimination in such a large area in Belgium with this high number of tests. Although Belgium is a country that has already been subject to research in multiple studies on housing market discrimination (Ghekiere and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Heylen and Van den Broeck Citation2016; Verhaeghe and De Coninck Citation2021), both the amount of conducted tests as the selected area are unique. In this study, we apply multilevel logistic regression analysis on the odds to be invited for a viewing to 16.490 enquiries to test the relation and interaction between ethnic origin, gender and the homogeneity of a name in the search for a rental property.

Theory and hypothesis

Compared to the vast amount of research on ethnic origin, very little attention has been paid in previous research to the intersection of discrimination grounds when applying for housing. Some exceptions exist, such as gender and ethnic origin (e.g. Andersson, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2012; Björnsson, Kopsch, and Zoega Citation2018), ethnic origin and sexual orientation (e.g. Murchie and Pang Citation2018; Schwegman Citation2019) and gender and wealth (Faber and Mercier Citation2022).

“Intersectional approaches to the study of inequality share the increasing recognition that multiple categorical identities may interact in complex ways and fundamentally alter the meaning of category membership” (Di Stasio and Larsen Citation2020, 231). To explain how these categories intersect with each other to produce unique forms of discrimination, scholars have used intersectional theory and conceptualized discrimination as a multidimensional process along a matrix of oppression (Faber and Mercier Citation2022; Pedulla Citation2014, Citation2018). Intersectionality arises when unequal treatment in two or more individual categories generates a unique form of disadvantage that fundamentally alters the effect of one, single categorical membership (Collins Citation2015). Although previous research has extensively discussed the potential drivers for intersectionality in discrimination (Derous, Ryan, and Serlie Citation2015; Mukkamala and Suyemoto Citation2018), research that investigates this theoretical explanation with sound empirical evidence about discriminatory behaviour is scarce.

In this study, we test discrimination against rental candidates with Moroccan and Polish names. Previous research in Europe has found extensive discrimination against these two ethnic origin groups. In Sweden, Norway, Belgium, Spain, France and Germany, candidates with Arab/Muslim names are found to be significantly discriminated against (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Andersson, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2012; Auspurg, Hinz, and Schmid Citation2017; Bosch, Carnero, and Farre Citation2010; Ghekiere and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Heylen and Van den Broeck Citation2016; Le Gallo et al. Citation2019). Additionally, significant but lower levels of discrimination are also found towards candidates with European-sounding names (Acolin, Bostic, and Painter Citation2016; Baldini and Federici Citation2011; Björnsson, Kopsch, and Zoega Citation2018; Carlsson and Eriksson Citation2014). The majority of these studies turn to the two dominant theoretical mechanisms of discrimination in both sociological and economic literature on rental discrimination, namely taste-based and statistical discrimination. Taste-based discrimination occurs when the agent’s own preference or bias is the main driver for a discriminatory selection (Becker Citation1971). Discrimination through the taste-based mechanism is considered a conscious, personal act. In the original formulation of taste-based discrimination, Becker (Citation1971) argues that gatekeepers are willing to pay a certain price for not interacting with a member of an (ethnic) minority group. In labour market context, this cost is a percentage of their wage directly proportionate to their experienced distaste to avoid working alongside minority colleagues (Becker Citation1971; Lippens, Baert, and Derous Citation2021). On the housing market, it would be the cost of not renting out the dwelling because of a personal distaste towards certain candidates. Statistical discrimination, on the other hand, builds on the notion that unequal treatment arises when no or little information on the candidate is at hand, which pushes the agent to use general group characteristics to judge the individual candidate (Arrow Citation1973). However, as Bohren et al. (Citation2019) argue, the underlying assumption of this mechanism is that they rely on accurate beliefs about ethnic groups, but reality shows that the occurrence of inaccurate beliefs and prejudices and thus inaccurate statistical discrimination is often present. Besides the preceding empirical findings and theoretical mechanisms of discrimination, we expect that the substantial electoral success of far-right political parties in Europe and in Belgium account for a large share of negative attitudes towards multiple ethnic minority groups (Castelli Gattinara and Pirro Citation2019). We hypothesize that both type of candidates, with Moroccan and Polish names, experience discrimination in access to housing (H1).

Secondly, we vary the homogeneity of the names used to signal the discrimination grounds. Previous research predominantly used homogenous names (first and last name signalling the same ethnic origin) as a proxy for ethnic origin when measuring discrimination (Gaddis Citation2017). However, in this study, we also include heterogenous names, a combination of an Anglo-Saxon first name and a last name stemming from another ethnic origin group (e.g. Belgian first and Moroccan last name). These mixed names have been used in research before but are rarely empirically tested (Gaddis Citation2019; Martiniello and Verhaeghe Citation2022). However, they do make for an interesting case. When considering the comparison between mixed and homogenous names, higher discrimination rates might be expected towards candidates with homogenous as compared to mixed names for three reasons. The first reason is what we name the spatial-distance explanation: the name a person carries might give indications as to whether or not the person is born in the studied country (Gaddis Citation2019). A person with a homogenous name might be perceived as a first-generation migrant. This as opposed to carrying a mixed name, which might raise the perception that the person is a 1.5, second or further generation migrant, and is thus born in the studied country (or migrated at a very young age) but has roots somewhere else. The second reason, here called the cultural-distance explanation, comprises an emotional-cultural aspect. A person with a homogenous name might be seen as someone (or a member of a family – as a person’s name is given by his/her parents) who is unwilling to adapt to the culture of the studied country. On the contrary, having a mixed name might be seen as a signal for the willingness to culturally adapt (Gaddis Citation2019; Tuppat and Gerhards Citation2021). Both the spatial-distance and cultural-distance explanations indicate that mixed names might be perceived as an increase in perceived nearness towards the ethnic majority group as compared to homogenous names. This perceived nearness might in turn result in lower discrimination rates, influenced by in-group favouritism (Greenwald and Pettigrew Citation2014). Thirdly, a more methodological reason is that signals of ethnic origin should be clear in order to trigger discriminatory behaviour (Tuppat and Gerhards Citation2021). It is harder to assess the ethnic origin of a name for mixed names (Martiniello and Verhaeghe Citation2022), possibly leading to lower levels of discrimination. We consequently hypothesize that among ethnic minorities, candidates with homogenous names experience more discrimination than those with mixed names (H2).

Thirdly, we include gender in our data collection and analysis, distinguishing between male and female rental candidates. While discrimination on the labour market is mostly present against female job candidates, most studies seem to prove that men are often disadvantaged on the rental housing market as compared to women (Ahmed and Hammarstedt Citation2008; Andersson, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam Citation2012; Baldini and Federici Citation2011; Flage Citation2018; Heylen and Van den Broeck Citation2016). Possible theoretical explanation could relate to the statistical mechanism of discrimination, in which group characteristics of female candidates are used to assess the fit of the individual candidate. However, these group characteristics could be subject to gender stereotyping. Female rental candidates may be considered cleaner and tidier, and therefore better in maintaining a dwelling in a good condition. Additionally, as Gusciute, Mühlau, and Layte (Citation2022) argues, women could be favoured as tenants due to their “agreeable” and “conscientious” personalities (Hyde Citation2014). Therefore, we hypothesis that female rental candidates are favoured over male rental candidates (H3).

As for the intersect between ethnic origin and gender, Bengtsson and colleagues (Citation2012) argue that ethnic discrimination overshadows gender discrimination, leading to the “gender advantage” for women to decrease or even disappear for rental candidates with Arab/Muslim names. In contrast, studies by Baldini and Federici (Citation2011) or Heylen and Vandenbroeck (Citation2016) find that discrimination is higher against male than female rental candidates with Arab/Muslim names. In general, a recent meta-analysis has shown that female candidates have higher chances to be invited for a viewing than male candidates (Flage Citation2018). Ethnic minority male candidates, however, experience more gender discrimination than the ethnic majority male candidates. Also, Andersson, Jakobsson, and Kotsadam (Citation2012) show that in invitation rates for the Arab candidates, the female candidate is favoured over the male candidate. Same goes for the study by Bosch, Carnero, and Farré (Citation2015), in which the results show that, while ethnic majority women have lower invitation rates than their male counterparts, ethnic minority female have higher chance of invitation than their male counter candidates. Importantly, in most studies, gender discrimination is measured within the same ethnic group. Female ethnic minority candidates are compared to male ethnic minority candidates and male ethnic majority candidates with their female ethnic majority counterpart. However, to measure the intersect between gender and ethnic origin, it is of importance to also study the presence of the two grounds (treatment group) against the baseline model (control group). Following the empirical evidence in the literature, we hypothesize that, ethnic minority men face most discrimination (H4).

Finally, as for the intersection between gender and the homogeneity of the name, we expect that the combination of both grounds of discrimination, gender and the homogeneity of names, will lead to more discrimination than the effects of one. More concretely, ethnic minority men with homogenous names are expected to be more disadvantaged than ethnic minority women or men with mixed names (H5).

In what follows, we will first discuss the research design and the applied multilevel logistic regression analysis. This is followed by a presentation of the results, whereby we built from individual identity-element effects on discrimination, to a combination of two elements to a full integration of ethnic origin, gender and the homogeneity of names. The findings are consequently discussed in the conclusion.

Research design

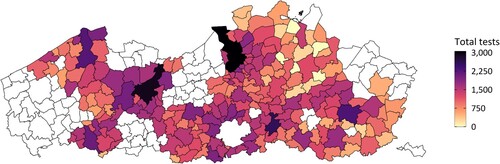

Between April and June 2021, we conducted 8.245 correspondence tests among real estate agents and private landlords on the private rental housing market in Flanders, the largest and Dutch-speaking region of Belgium (see for visual overview). The regional housing market is dominated by home owners with outstanding mortgages, which were for long heavily subsidized by the government. Private renters account for a relatively small proportion of tenure types and are especially popular among the lower income groups (Winters and Heylen Citation2014). The proportion of social housing track is even more marginal in Belgium. This study only focusses on discrimination on the private rental market.

Discriminatory behaviour on the rental housing market was measured with the field experimental technique of correspondence testing. In these experiments, two quasi-identical candidates apply for a rental advertisement (Gaddis Citation2018; Verhaeghe Citation2022). Only the characteristic that signals the discrimination ground (e.g. their name when measuring ethnic discrimination) differs between the two candidates. When the test group (e.g. ethnic minority) is systemically less invited to a viewing or treated differently from the control group (e.g. ethnic majority), discrimination is at stake (Verhaeghe et al. Citation2023). These field experiments are considered as the “golden standard” to objectively measure discrimination in the field (Heath and Di Stasio Citation2019; Verhaeghe Citation2022), and are inherent to the majority of studies on housing market discrimination (for example see Auspurg, Hinz, and Schmid (Citation2017)). Moreover, its experimental design allows to establish causal relationships between the discrimination ground under scrutiny and the behavioural reaction of landlords and realtors. Finally, in contrast to face-to-face audit studies, correspondence testing allows to standardize the content and form of contact with the landlords or realtors, which already counters one of the so-called “Heckman and Siegelman (Citation1993) critiques”.

First, as we test for multiple grounds of discrimination, 10 different types of profiles were created, whose names signal the tested discrimination grounds: ethnic origin, gender and the homogeneity of names. Similarly as in previous research, we use the name of the candidate as a proxy for these grounds (Gaddis Citation2017). The names we used stem from a survey on the perception of names conducted among a sample of 990 inhabitants of Belgian origin (Martiniello and Verhaeghe Citation2022). The name-combinations were created out of databases accessible through StatBel (Statistics Belgium). These databases provide lists with the most popular male and female first names between 2010 and 2019 and the most recurring last names in 2020. The results of Martiniello and Verhaeghe (Citation2022) show that approximately 98.5 per cent of the respondents successfully differentiate between homogenous names as of Belgian origin or not. For mixed names, the rate is of 95.5 per cent. For the distinction between names as European or not, 88.6 per cent of the respondents are successful in categorizing the Belgian names, followed by 64.3 per cent and 61.8 per cent for the mixed and homogenous Polish names respectively. Respondents were less successful in classifying Moroccan names (48.2 per cent for homogenous and 36.3 per cent for mixed names). The rates for successfully recognizing the specific ethnic origin are 35 per cent and 32.6 per cent for homogenous and mixed Polish names. For Moroccan homogenous and mixed names, the rates are 34 per cent and 21.3 per cent. Nevertheless, the authors show that there is important within-group variation, depending on the specific name. We therefore used the names with the highest congruence rates and the ones validated in their research.

In order to avoid detection, multiple names were used for each type of profile. An overview of the used names can be found in . This specific research population was chosen because residents with Moroccan roots (including both first and second generation) contribute to the second biggest ethnic group in Flanders, consisting of 3.2 per cent of the total Flemish population, after the Dutch population (data accessed via statbel.be). Additionally, Polish rental candidates are studied, as in Flanders they represent 1 per cent of the total Flemish population (first and second generation), being the fifth biggest nationality group in relative terms (data accessed via statbel.be). The Moroccan community has a long migration history in Belgium, dating back to the labour migration in the sixties, followed by family migration since the mid-seventies (Timmerman Citation2017). In contrast, the Polish migration started more recently after the fall of the Iron curtain and was accelerated with the expansion of the EU in 2004. Anti-immigration attitudes in Belgium are worse about migrants from non-European, Muslim countries (such as Moroccan migrants) than about European, non-Muslim migrants (such as Polish migrants) (De Coninck Citation2020). In addition, the popular far-right party in the Flemish region especially stigmatizes the non-European migrants from the Maghreb and Turkey, and less the intra-European migrants.

Table 1. The used names in the correspondence testing.

Subsequently, two (or three) fictitious rental candidates applied to the same rental property. As the sampling frame for rental advertisements, we used Immoweb.be, the largest online rental platform in Belgium. The platform was not informed about the testing. Following previous research (McLaren and Shanbhogue Citation2011; Verhaeghe and Ghekiere Citation2020), Google search data can be used to roughly estimate the relative rental demand. According to Google trends, 86 per cent of the rental online demand in Belgium during the period of data collection was on Immoweb, whereas the two alternative websites (Zimmo and Immovlan) only represented 14 per cent of the Google searches. Therefore, Immoweb can be considered as a representative sampling frame for the online rental demand. Nevertheless, it doesn’t cover advertisements who are only offered offline or informally, which might inhibit the representatives of this study (see Verhaeghe Citation2022).

The rental candidates have identical profiles with the exception of the investigated discrimination ground. Concretely, the two candidates differ only in their names. For both candidates, an e-mail address, telephone number and a profile are created on Immoweb.be, in order to execute the application but also to avoid detection. We first sent out the e-mail of the test person (e.g. the candidate with a Moroccan or Polish-sounding name) and a few hours later the e-mail of the control person (e.g. the candidate with a Belgian-sounding name). By doing so, we have strong evidence that in the case where the control person is invited and the test person is not, discrimination is at stake (Baldassarri and Abascal Citation2017).

We conducted one to two tests per week, with sufficient spacing between tests concerning the same type of profile. Afterwards, we kept track of the written responses of the realtors and landlords for ten days. Next, we examine the extent to which the candidates in the test group were treated systematically more unfavourably than the candidates in the control group. When there is systematic disadvantageous treatment, it is attributed to discrimination. The online application for housing proceeds in the same way each time. We used the standard message built into the contact function of the rental website, which could be translated as “Dear, I found your property on Immoweb and would like to schedule a viewing. Thank you”. This message was copied and signed by the candidate with his/her name.

The data is analysed by means of multilevel logistic regression analysis. The dependent variable is “invitation”, which is a dichotomous variable whereby 1 stands for an invitation and 0 for no invitation. Because rental dwellings (level 1) are nested in advertisements (level 2), we conduct multilevel analysis. The variances in the null model are significant (p < .001), with an ICC of 0.963 indicating a very good reliability. The independent variables are : ethnic origin (Belgian, Polish or Moroccan),

: gender (man or woman) and

: homogeneity (homogenous or mixed). No cross-level interaction is needed as all interactions are situated on level 1. The specification of our three-way interaction model is expressed as:

Let be the invitation to a dwelling. Our random intercept model with a three-way interaction term contains two error terms, with

being the residual error. We controlled all regression analysis for the rental price and size of the dwelling (expressed in number of rooms) as a test for robustness. Also, as a robustness tests and because of the multitude of interactions in our analysis, we added a regression analysis that accounts for all possible reference categories, in the Appendix.

Results

Descriptive results

In , we present the bivariate statistics on the rate at which the tested profiles are invited to view a rental dwelling in Flanders. When considering only ethnic origin, candidates with Moroccan names have the lowest invitation rate (27.8 per cent), followed by candidates with Polish (33.8 per cent) and Belgian (37.8 per cent) names. Besides, having a homogenous or mixed does not appear to have a strong influence on being invited, as for the former the invitation rate is of 34.0 per cent and for the latter 32.8 per cent. The invitation rates for men and women are comparable, with 34.2 per cent and 33.1 per cent, respectively.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (n = 16.490).

We also take the intersection on ethnic origin, gender and mixed versus homogenous names into account. Male candidates with a Belgian first and last name have the highest invitation rates, with 38.8 per cent. Female candidates with a Belgian first and last name (36.1 per cent) have comparable invitation rates to those of male candidates with a Belgian first name and a Polish last name (36.9 per cent). Candidates with a Moroccan first and last name, both man and woman, overall receive the lowest amount of positive response (respectively 26.5 per cent and 27.4 per cent). Candidates with mixed Moroccan names (respectively 30.3 per cent and 31.2 per cent for women and men) have comparable invitation rates as candidates with Polish homogenous names (respectively 30.9 per cent and 34.2 per cent for women and men).

Regression analysis

To arrive at an intersectional approach, we conduct multilevel logistic regression analysis on the odds to being invited for a viewing. First for the three discrimination grounds separately (models 1, 2 and 4), then for the interaction effect of two elements at a time (models 3, 5 and 6), and lastly for the three-way interactions (). The results of the one- and two-way interactions are shown in . To test our first hypothesis, which expects discrimination towards Moroccan and Polish rental candidates, we look at the effect of ethnic origin on the odds to be invited for a viewing. The results in model 1 show that candidates with Moroccan (0.491) and Polish (0.651) names have significantly lower odds to be invited for a viewing than candidates with Belgian names. Especially candidates with Moroccan names have the lowest odds. This result supports our first hypothesis.

Table 3. Multilevel logistic regression analysis on the odds to be invited for a viewing.

The second hypothesis expects a higher discrimination level against candidates with homogenous names, compared to mixed names. Our results in model 4 show that mixed names indeed have higher odds (1.214) to be invited for a viewing than homogenous names.

To test the third hypothesis, whereby we expect that female rental candidates are favoured over male rental candidates, we analyse the effect of gender on the odds to be invited for a viewing. Contradicting the hypothesis, we find that women are significantly less likely (0.662) to be invited for a viewing as compared to men. While this result is conflicting with Flage’s (Citation2018) meta results, we do find some individual studies in Flanders that comply with our results (Verhaeghe, Martiniello, and Ghekiere Citation2020). Importantly, gender is measured as an overarching variable that includes both ethnic majority and ethnic minority candidates. Results from the interaction terms will provide more insight in the gender effects for ethnic groups separately.

When looking at the interaction effects to control for a two-way intersection, we find that having a Moroccan name and having a female name is the only intersect that significantly interacts. The effect of gender is opposite (1.265) for candidates with Moroccan names compared with candidates with Belgian names (0.598). Further analyses show that Moroccan women do not significantly differ from Moroccan men in their odds to be invited for a visit. Models 5 and 6 show that the intersection of the homogeneity of names with ethnic origin or gender appears to be less influential. With no effect from the intersect of homogeneity of names and gender, we reject hypothesis 5.

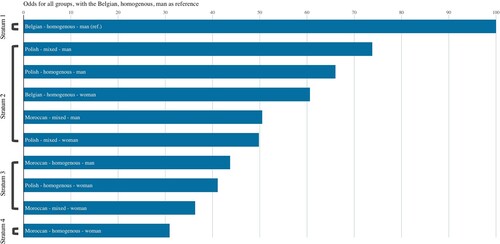

In , we present the relative chance to be invited for a viewing by taking the three-way intersection of gender, ethnic origin and homogeneity of rental candidates’ name into account. A red colour portrays a negative effect and the green colour a positive effect. The stronger the shade, the stronger the effect (no colour means no significant effect; see Table A1 in Appendix for more detailed results with significance levels). From this table, it appears that (male) candidates with Belgian homogenous names are treated the most advantageously on the Flemish rental housing market, followed by candidates with Polish mixed names. In addition, male and female candidates with Moroccan homogenous names are confronted with the most rental discrimination, as all other profiles have significantly higher relative chances to be invited. Ordering the different tested profiles from least to most rental discrimination, taking the three-way intersection into account, we become the following ethnic hierarchy on the rental housing market: stratum (1) candidates with Belgian male names; stratum (2a) Polish mixed male names, (2b) Polish homogenous male names, Belgian female names, (2c) Moroccan mixed male names, Polish mixed female names; stratum (3a) Moroccan homogenous male names, Polish homogenous female names, (3b) Moroccan mixed female names; and stratum (4) Moroccan homogenous female names. This classification is visualized in .

Table 4. The odds to be invited for a viewing: three-way interactions.

Paying attention to a full intersectional approach appears to be relevant, as the relative chance to be invited for candidates with Belgian female names does not significantly differ from those of candidates with, mixed Polish male and female; Polish homogenous male names and mixed Moroccan male names (stratum 2). This although Belgian names, without taking an intersectional approach, appear to be the most invited (). Also, candidates with Polish homogenous female names do not have significantly different invitation rates than candidates with Moroccan homogenous male names or mixed female names (stratum 3).

Adding the level of homogeneity of names to the picture further contributes to our understanding. In line with the double jeopardy theory as formulated in hypothesis five, Moroccan women face more discrimination than Moroccan men, when they both have mixed names or homogenous names. These findings contradict hypothesis 4. This same pattern of double jeopardy could be found among Polish candidates: no matter whether they have homogenous or mixed names, Polish women are always discriminated more than Polish men. Moreover, contradicting hypothesis 5, Polish women with homogenous names are more disadvantaged than Polish women with mixed names and Polish men. This confirms the relevance of applying a full intra- and inter-categorical lens on studying ethnic disadvantages on the housing market ().

Discussion and conclusion

Although many studies have already shown persistent patterns of ethnic and gender discrimination on the housing market (Auspurg, Hinz, and Schmid Citation2017; Flage Citation2018), there is surprisingly little research that investigates these disadvantages from an intersectional approach, in which multiple grounds of discrimination are examined together. The goal of this paper is to examine the racialized and gendered nature of discrimination on the housing market with an intersectional design and analysis. Moreover, in line with recent research (e.g. Gaddis Citation2017; Gaddis Citation2018; Martiniello and Verhaeghe Citation2022) we further distinguish intra-categorically between homogenuous and mixed minority names of the rental candidates. For these aims, we collected data on discriminatory behaviour against Moroccon and Polish candidates by means of correspondence tests with 16.490 rental enquiries.

In line with previous research (e.g. Heylen and Van den Broeck Citation2016; Ghekiere and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Verhaeghe and De Coninck Citation2022), we found pronounced discrimination against Moroccan and Polish candidates on the rental housing market in Flanders. Moreover, it appears that Moroccan candidates are more discriminated than their Polish counterparts. This resembles previous studies which indicate a bright European vs. non-European boundary in rental discrimination patterns (e.g. Acolin, Bostic, and Painter Citation2016; Baldini and Federici Citation2011; Carlsson and Eriksson Citation2014). Further research could shed light to which extent this boundary is based on ethnic-national, religious and/or skin colour factors.

Gender discrimination appeared to exist in favour of male rental candidates, as opposed to what we hypothesized in the theoretical framework. While this result contrasts multiple individual and review studies on the housing market (Flage Citation2018, Citation2020), we do find similar results in other studies on the Belgian rental market (e.g. Verhaeghe, Martiniello, and Ghekiere Citation2020). Also, Massey and Lundy (Citation2001) who used a similar intersectional model in their analysis, found similar results. They found that gender correlated strongly with financial strength, resulting in excessive discrimination towards poor, black, female renters. This form of statistical discrimination could be at stake in our sample too. However, it is important to note that although we found significant gender effects, the difference in invitation rates is very small (33.1 vs. 34.2 per cent), considerably smaller than the difference in invitation rates for ethnic origin (37.8 vs. 27.8 per cent).

For the homogeneity of names, candidates with homogenous names experience significant more discrimination then the counter candidates with mixed names. Consequently, a perceived nearness to the ethnic majority leads to less discrimination. Besides, the most substantial contribution of this study lies in its full intersectional design along the axes ethnic origin, gender and homogeneity of names. Going from simple bivariate analyses to two- and three-way interaction models we find that the levels of discrimination vary much when we add intra-categorical distinctions within each ethnic group. Next to clear gender inequalities within each ethnic group where women are discriminated more than men, we find four strata on the rental housing market in Flanders. At the top are the male candidates with Belgian names, who are invited the most for a visit. Next are the Polish men with mixed or homogenous names, the Belgian women, the Moroccan men with mixed names and the Polish women with mixed names. This second stratum is followed by a third statum composed by Polish women with homogenous names, Moroccan men with homogenous names and Moroccan women with mixed names. The most discriminated stratum consists of Moroccan women with homogenous names. These findings support and extend the double – here even triple – jeopardy theory (Beal Citation2008), which states that multiple discrimination grounds enforce each other. Without a full intersectional approach, these layered patterns of exclusion would have be hidden behind the bold boundaries of ethnic or gender distinctions.

Our results expose the relevance and importance that the intersection of different categories – as opposed to simple additive effects of different categories – has on measured discrimination. These findings are relevant for policy, indicating the necessity to move beyond the focused attention on single categories (ethnic origin or gender or sexual orientation …). However, this does not mean a move towards policies that take different categories individually into account, as is the case in diversity policies. Although the latter recognizes different categories of discrimination, these categories are often analysed parallel to each other, rather than as intersecting with each other (Schiller Citation2017). Better, policy – and specifically anti-discrimination policy – should address discrimination based on the intertwined effect of belonging or being ascribed to multiple categories.

The conclusions should, however, be considered within the confines of a few limitations. Firstly, we only examined the first phase of the rental process – getting an invitation for a viewing or not – whereas more and other forms of discrimination could occur, also in the latter phases of the process (Ghekiere et al., Citation2022). In addition, this study only investigated discrimination for rental properties advertized on a popular online platform in Belgium, leaving the informally let properties out of the picture. If there is more discrimination occurring via informal selection processes, this study might have underestimated the level of rental discrimination (Verhaeghe Citation2022). Secondly, we discuss only the intersect between a few discrimination grounds. Future research should include the intersect with other grounds, like income, sexual orientation, family status or disability. Also the discrimination grounds used for this research could be elaborated in future research. We, for example, solely consider rental candidates with Polish and Moroccan names, although people with other ethnic backgrounds are also confronted with discrimination. Thirdly, we hypothesize that a mixed name is an indicator for the nearness towards the ethnic majority group. However, whether this nearness is perceived as cultural, social or generational, should be subject of future research. Fourthly, by means of correspondence testing we can solely measure the degree of discriminatory behaviour, but not infer the motives underlying that behaviour. Lastly, perceived discrimination remains in the shadow, as the focus of this study is on objectively measured discrimination. Future research could focus on experiences of perceived discrimination, though preferably considering an intersectional lens.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FWO under Grant S004119N. Ethical approval was granted by the ethical commission of human science of the authors institution under reference number ECHW_289. The principle of informed consent was waived by the ethical committee as this might bias the correspondence tests. The two first authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Authors were ordered alphabetically.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acolin, A., R. Bostic, and G. Painter. 2016. “A Field Study of Rental Market Discrimination Across Origins in France.” Journal of Urban Economics 95: 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2016.07.003.

- Ahmed, A. M., and M. Hammarstedt. 2008. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment on the Internet.” Journal of Urban Economics 64 (2): 362–372. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2008.02.004.

- Andersson, L., N. Jakobsson, and A. Kotsadam. 2012. “A Field Experiment of Discrimination in the Norwegian Housing Market: Gender, Class, and Ethnicity.” Land Economics 88 (2): 233–240. doi:10.1353/lde.2012.0016.

- Arrow, K. 1973. “The Theory of Discrimination.” Discrimination in Labor Markets 3 (10): 3–33.

- Auspurg, K., T. Hinz, and L. Schmid. 2017. “Contexts and Conditions of Ethnic Discrimination: Evidence from a Field Experiment in a German Housing Market.” Journal of Housing Economics 35: 26–36. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2017.01.003.

- Auspurg, K., A. Schneck, and T. Hinz. 2019. “Closed Doors Everywhere? A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments on Ethnic Discrimination in Rental Housing Markets.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (1): 95–114. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1489223.

- Baldassarri, D., and M. Abascal. 2017. “Field Experiments Across the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 43 (1): 41–73. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112445.

- Baldini, M., and M. Federici. 2011. “Ethnic Discrimination in the Italian Rental Housing Market.” Journal of Housing Economics 20 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2011.02.003.

- Beal, F. M. 2008. “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female.” Meridians 8 (2): 166–176. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40338758.

- Becker, G. S. 1971. The Economics of Discrimination. University of Chicago Press Economics Books.

- Bengtsson, R., E. Iverman, and B. T. Hinnerich. 2012. “Gender and Ethnic Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market.” Applied Economics Letters 19 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/13504851.2011.564125.

- Björnsson, D. F., F. Kopsch, and G. Zoega. 2018. “Discrimination in the Housing Market as an Impediment to European Labour Force Integration: The Case of Iceland.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 19 (3): 829–847. doi:10.1007/s12134-0574-0.

- Bohren, J. A., K. Haggag, A. Imas, and D. G. Pope. 2019. “Inaccurate Statistical Discrimination: An Identification Problem.” NBER Working Paper Series.

- Bosch, M., M. A. Carnero, and L. Farre. 2010. “Information and Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: Evidence from a Field Experiment.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 40 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2009.11.001.

- Bosch, M., M. Carnero, and L. Farré. 2015. “Rental Housing Discrimination and the Persistence of Ethnic Enclaves.” SERIES 6 (2): 129–152. doi:10.1007/s13209-015-0122-5.

- Carlsson, M., and S. Eriksson. 2014. “Discrimination in the Rental Market for Apartments.” Journal of Housing Economics 23: 41–54. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2013.11.004.

- Castelli Gattinara, P., and A. L. Pirro. 2019. “The far Right as Social Movement.” European Societies 21 (4): 447–462. doi:10.1080/14616696.2018.1494301.

- Cho, S., K. W. Crenshaw, and L. McCall. 2013. “Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38 (4): 785–810. doi:10.1086/669608.

- Collins, P. H. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Sociology 41: 1–20. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139.

- De Coninck, D. 2020. “Migrant Categorizations and European Public Opinion: Diverging Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Refugees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1667–1686. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1694406.

- Derous, E., A. M. Ryan, and A. W. Serlie. 2015. “Double Jeopardy upon Resume Screening: When Achmed is Less Employable Than Aisha.” Personnel Psychology 68 (3): 659–696. doi:10.1111/peps.12078.

- Di Stasio, V., and E. N. Larsen. 2020. “The Racialized and Gendered Workplace: Applying an Intersectional Lens to a Field Experiment on Hiring Discrimination in Five European Labor Markets.” Social Psychology Quarterly 83 (3): 229–250. doi:10.1177/0190272520902994.

- Faber, J. W., and M.-D. Mercier. 2022. “Multidimensional Discrimination in the Online Rental Housing Market: Implications for Families with Young Children.” Housing Policy Debate, 1–24. doi:10.1080/10511482.2021.2010118.

- Flage, A. 2018. “Ethnic and Gender Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis of Correspondence Tests, 2006–2017.” Journal of Housing Economics 41: 251–273. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2018.07.003.

- Flage, A. 2020. “Pourquoi Vincent a-t-il moins de chances d’obtenir un logement qu’Émilie? Une analyse des causes de la discrimination à l’égard des noms masculins.” Revue D'economie Politique 130 (4): 633–657. doi:10.3917/redp.304.0129.

- Flage, A. 2021. “Discrimination Against Same-sex Couples in the Rental Housing Market, a Meta-Analysis.” Economics Bulletin 42 (2): 643–653.

- Fumarco, L. 2017. “Disability Discrimination in the Italian Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment with Blind Tenants.” Land Economics 93 (4): 567–584. doi:10.3368/le.93.4.567.

- Gaddis, S. M. 2017. “How Black are Lakisha and Jamal? Racial Perceptions from Names Used in Correspondence Audit Studies.” Sociological Science 4: 469–489. doi:10.15195/v4.a19.

- Gaddis, S. M. 2018. “An Introduction to Audit Studies in the Social Sciences.” Audit Studies: Behind the Scenes with Theory, Method, and Nuance 14: 3–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71153-9_1.

- Gaddis, S. M. 2019. Assessing Immigrant Generational Status from Names: Evidence for Experiments Examining Racial/Ethnic and Immigrant Discrimination. Ethnic and Immigrant Discrimination (February 12, 2019).

- Ghekiere, A., Lippens, L., Baert, S., & Verhaeghe, P.-P. 2022. “Ethnic Discrimination on Paper: Uncovering Realtors’ Willingness to Discriminate with Mystery Mails.” Applied Economics Letters, 1-4.

- Ghekiere, A., and P.-P. Verhaeghe. 2022. “How Does Ethnic Discrimination on the Housing Market Differ Across Neighborhoods and Real Estate Agencies?” Journal of Housing Economics 55: 101820–101831. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2021.101820.

- Greenwald, A. G., and T. F. Pettigrew. 2014. “With Malice Toward None and Charity for Some: Ingroup Favoritism Enables Discrimination.” American Psychologist 69 (7): 669–684. doi:10.1037/a0036056.

- Gusciute, E., P. Mühlau, and R. Layte. 2022. “Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market: A Field Experiment in Ireland.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (3): 613–634. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1813017.

- Heath, A. F., and V. Di Stasio. 2019. “Racial Discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments on Racial Discrimination in the British Labour Market.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (5): 1774–1798. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12676.

- Heckman, J. J., and P. Siegelman. 1993. “The Urban Institute Audit Studies: Their Methods and Findings.” Clear and Convincing Evidence: Measurement of Discrimination in America, 187–258.

- Heylen, K., and K. Van den Broeck. 2016. “Discrimination and Selection in the Belgian Private Rental Market.” Housing Studies 31 (2): 223–236. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1070798.

- Hyde, J. S. 2014. “Gender Similarities and Differences.” Annual Review of Psychology 65: 373–398. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115057.

- Le Gallo, J., Y. l’Horty, L. Du Parquet, and P. Petit. 2019. “Discriminations in Access to Housing: A Test on Urban Areas in Metropolitan France.” Economie et Statistique 513 (1): 27–45. doi:10.24187/ecostat2019.513.2004.

- Lippens, L., S. Baert, and E. Derous. 2021. “Loss Aversion in Taste-Based Employee Discrimination: Evidence from a Choice Experiment.” Economics Letters 208 (2021): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2021110081.

- MacDonald, H., G. Galster, and R. Dufty-Jones. 2018. “The Geography of Rental Housing Discrimination, Segregation, and Social Exclusion: New Evidence from Sydney.” Journal of Urban Affairs 40 (2): 226–245. doi:10.1080/07352166.2017.1324247.

- Martiniello, B., and P.-P. Verhaeghe. 2022. “Signaling Ethnic-National Origin Through Names? The Perception of Names from an Intersectional Perspective.” PLoS one 17 (8): 1–20. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0270990.

- Massey, D. S., and G. Lundy. 2001. “Use of Black English and Racial Discrimination in Urban Housing Markets: New Methods and Findings.” Urban Affairs Review 36 (4): 452–469. doi:10.1177/10780870122184957.

- McLaren, N., and R. Shanbhogue. 2011. “Using Internet Search Data as Economic Indicators.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2011: Q2. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1865276.

- Meissner, F. 2015. “Migration in Migration-Related Diversity? The Nexus Between Superdiversity and Migration Studies.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 556–567. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.970209.

- Mukkamala, S., and K. L. Suyemoto. 2018. “Racialized Sexism/Sexualized Racism: A Multimethod Study of Intersectional Experiences of Discrimination for Asian American Women.” Asian American Journal of Psychology 9 (1): 32. doi:10.1037/aap0000104.

- Murchie, J., and J. Pang. 2018. “Rental Housing Discrimination Across Protected Classes: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 73: 170–179. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2018.10.003.

- Pedulla, D. S. 2014. “The Positive Consequences of Negative Stereotypes: Race, Sexual Orientation, and the Job Application Process.” Social Psychology Quarterly 77 (1): 75–94. doi:10.1177/0190272513506229.

- Pedulla, D. S. 2018. “How Race and Unemployment Shape Labor Market Opportunities: Additive, Amplified, or Muted Effects?” Social Forces 96 (4): 1477–1506. doi:10.1093/sf/soy002.

- Quillian, L., J. J. Lee, and B. Honoré. 2020. “Racial Discrimination in the US Housing and Mortgage Lending Markets: A Quantitative Review of Trends, 1976–2016.” Race and Social Problems 12 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1007/s12552-019-09276-x.

- Ruwanpura, K. N. 2008. “Multiple Identities, Multiple-Discrimination: A Critical Review.” Feminist Economics 14 (3): 77–105. doi:10.1080/13545700802035659.

- Schiller, M. 2017. “The Implementation Trap: The Local Level and Diversity Policies.” Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives 83 (2): 271–286. doi:10.1177/0020852315590204.

- Schwegman, D. 2019. “Rental Market Discrimination Against Same-sex Couples: Evidence from a Pairwise-Matched Email Correspondence Test.” Housing Policy Debate 29 (2): 250–272. doi:10.1080/10511482.2018.1512005.

- Squires, G. D. 2007. “Demobilization of the Individualistic Bias: Housing Market Discrimination as a Contributor to Labor Market and Economic Inequality.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 609 (1): 200–214. doi:10.1177/0002716206294953.

- Timmerman, C. 2017. Moroccan Migration in Belgium: More Than 50 Years of Settlement (Vol. 1). Leuven: University Press.

- Tuppat, J., and J. Gerhards. 2021. “Immigrants’ First Names and Perceived Discrimination: A Contribution to Understanding the Integration Paradox.” European Sociological Review 37 (1): 121–135. doi:10.1093/esr/jcaa041.

- Verhaeghe, P.-P. 2022. “Correspondence Studies.” In Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics, edited by K. F. Zimmermann, 1–19. Cham: Springer.

- Verhaeghe, P.-P., and D. De Coninck. 2021. “Rental Discrimination, Perceived Threat and Public Attitudes Towards Immigration and Refugees.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45: 1371–1393. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1939092.

- Verhaeghe, P. -P., and D. De Coninck. 2022. “Rental Discrimination, Perceived Threat and Public Attitudes Towards Immigration and Refugees.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (7): 1371–1393. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1939092.

- Verhaeghe, P.-P., and A. Ghekiere. 2020. “The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Ethnic Discrimination on the Housing Market.” European Societies 23: 1–16. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1827447.

- Verhaeghe, P.-P., B. Martiniello, M. Endrich, and L. Van Landschoot. 2023. “Ethnic Discrimination on the Shared Short-Term Rental Market of Airbnb: Evidence from a Correspondence Study in Belgium.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 109: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103423.

- Verhaeghe, P.-P., B. Martiniello, and A. Ghekiere. 2020. “Discriminatie door makelaars op de huurwoningmarkt van Antwerpen: de nulmeting.” Brussel: Vakgroep Sociologie, Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

- Verhaeghe, P.-P., K. Van der Bracht, and B. Van de Putte. 2016. “Discrimination of Tenants with a Visual Impairment on the Housing Market: Empirical Evidence from Correspondence Tests.” Disability and Health Journal 9 (2): 234–238. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.10.002.

- Winters, S., and K. Heylen. 2014. “How Housing Outcomes Vary Between the Belgian Regions.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 29 (3): 541–556. doi:10.1007/s10901-013-9364-3.

Appendix

AppendixTable A1. Multilevel logistic regression analysis on the odds to be invited for a viewing for the intersection on gender, ethnic origin and homogeneity (n = 16.490).