?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Drawing on a unique survey question about personal identity in France, this article explores how majority and minority populations identify in terms of race/ethnicity and class. While prior studies have focused on one of these identities, the added value of this article is to examine both using a simultaneous equation model. Literature predicts that minorities have stronger ethnoracial identities, while majority members emphasize their class. Our findings confirm this trend, yet we go further by exploring heterogeneity by immigrant generation, origin and socioeconomic status. Guided by theories of assimilation, we show that non-European minorities are more likely to stress ethnoracial identity than Europeans, even among the second generation. Low-SES French majority members are more likely to emphasize ethnoracial items, suggesting a defensive white identity. In contrast, high-SES minorities stress both race/ethnicity and class. The conclusion discusses the intersection between class, race, and migration in France.

Introduction

Class and race tend to be regarded as antagonistic paradigms in France. Starting with Durkheim and throughout the Bourdieusian legacy, class-based stratification perspectives have long been more legitimate in the French social sciences, reflecting a prevailing belief that, unlike the U.S. context, ethnicity and race are less powerful sociological cleavages. Social class is also assumed to be more predominant in the formation of identities: while class consciousness is regarded as politically and socially legitimate, “racial” consciousness is not. However, evidence of high levels of ethnoracial inequality and discrimination (Quillian et al. Citation2019) increasingly challenges class reductionism within French social stratification scholarship (De Rudder, Poiret, and Vourc’h Citation2000; Fassin and Fassin Citation2006; Masclet Citation2012; Safi Citation2013). Further, the growing salience of identity politics over the last decades – as expressed by the steady rise in support for the far right and recurring controversies surrounding the veil – also suggests that ethnoracial identification is at the centre of French political dynamics. Recent research in political sociology highlights that identity politics are increasingly shaping the French electoral spectrum and documents the specificity of minority voting (Tiberj and Michon Citation2013).

Yet, in the absence of ethnoracial statistics in France’s colourblind context, little large-scale quantitative research exists about the extent to which ethnoracial characteristics such as origin, skin colour, or religion are meaningful identities. Further, if from a theoretical point of view, intersectionalFootnote1 perspectives emphasize the ways in which race/ethnicity and class intertwine (Harnois Citation2014; Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2019; Di Stasio and Larsen Citation2020; Nawyn and Gjokaj Citation2014), empirical analysis of how these dimensions articulate in the subjective identity of minority and majority groups remains sparse. Most prior studies, including in the U.S., have focused separately on either ethnoracial or class identity.

This article aims at bridging this gap. Using a unique question on personal identity in a large-scale French survey (Trajectories and Origins, or TeO), we describe patterns of class and ethnoracialFootnote2 subjective identification and examine how they vary between majority and minority groups, across immigrant generations and origins, and by socioeconomic status. Unlike prior studies, we examine both types of identity simultaneously, in order to highlight the ways in which they intersect or diverge. The findings show that minorities have stronger ethnoracial identities than the French majority, while majority members tend to emphasize class identities. Yet these patterns vary by generation and origin: non-European minorities are more likely to stress the ethnoracial dimension than European origins. These disparities persist even among second generation immigrants. Socioeconomic status also interacts with origin to influence the extent to which ethnoracial or class identities are embraced. Low-SES French majority members are more likely to emphasize ethnoracial items, suggesting a defensive white identity. In contrast, high-SES minorities stress both race/ethnicity and class. The conclusion discusses the intersection between class, race, and migration in social stratification and French politics.

Theoretical and empirical background

Ethnoracial and class identities in France

France is well-known for its colourblind model of citizenship rejecting ethnicity, race, religion, and other group-level differences as the basis of political organization and claims-making (Lorcerie Citation2007; Simon Citation2008b). Self-declared ethnoracial identification of the type used in the U.S. census is regarded as anti-constitutional and thus prohibited in public statistics, making ethnoracial inequality difficult to assess with large-scale representative data (Simon Citation2008a; Simon and Stavo-Debauge Citation2004). This institutional and cultural framework has contributed to conveying a vision of French society in which ethnoracial minorities do not exist (Amiraux and Simon Citation2006).

This general context has nonetheless undergone considerable change during the last decade, due to the enhanced measurement of migrant background beyond the first generation in major public statistics surveys. While race/ethnicity is omitted, information on parental nationality or country of birth enables categorical distinctions to be made between immigrants, children of immigrants, and French “natives”. This has paved the way for new evidence on ethnoracial inequality based on the measurement of socioeconomic gaps between majority and minority populations classified according to immigrants' national or regional origins (Aeberhardt et al. Citation2010; Frickey and Primon Citation2006; Meurs, Pailhé, and Simon Citation2006). Many studies highlight the specific disadvantages that first and second generation immigrants from North and Sub-Saharan Africa face in the labour and housing markets and, to a lesser extent, at school. Such conclusions have been confirmed in increasingly sophisticated paired testing studies and expanded to non-migratory categories. Evidence shows considerable discrimination against minorities in the hiring process and suggests that this discrimination is related to origin, skin colour and religion (Cédiey, Foroni, and Garner Citation2008; Petit, Duguet, and L'Horty Citation2015; Adida, Laitin, and Valfort Citation2014; Valfort Citation2015; Quillian et al. Citation2019; Zschirnt and Ruedin Citation2016; Arnoult et al. Citation2021).

While evidence on the objective disadvantage of minorities is growing, it is only very recently that the subjective dimension of inequality has been addressed in large-scale datasets. This research, however, mostly focuses not on ethnoracial identity per se, but rather on experiences of ethnoracial discrimination or on national identity and feelings of belonging. Using TeO, Safi and Simon (Citation2013) analysed subjective perceptions and experiences of ethnoracial discrimination among first and second generation immigrants. Drawing on self-reported questions on the experience of discrimination in general and across a variety of specific social spheres, they highlight the salience of perceived ethnoracial discrimination for respondents from an African background and French native migrants from overseas departmentsFootnote3 (overwhelmingly black). Reported discrimination also increases with educational attainment and among the second generation compared to the first (Brinbaum, Safi, and Simon Citation2018). Also using TeO, Jayet (Citation2016) and Donnaloja and McAvay (Citation2022) document that non-European origins feel they are less likely to be seen as French as others, even when they embrace a French national identity. These patterns are echoed in qualitative research, notably by Beaman (Citation2015), whose ethnography into second generation immigrants of North African origin documents that, despite being middle-class French citizens, their ethnoracial origin bars them from claiming a legitimate and recognized French identity. Despite the emphasis on national identity in these studies, many scholars point to the strong entanglement of nationality and race, with Frenchness often connoting whiteness and national identity marking an ethnoracial boundary in French society (Fassin and Mazouz Citation2007; Beaman Citation2015; Hajjat Citation2012).

Only one large-scale quantitative study to our knowledge, drawing as well on TeO, explores first and second generation immigrants’ level of identification with their “origin” (Simon and Tiberj Citation2018). They illustrate the centrality of ethnoracial identification for migrants and their descendants and variations by origin, immigrant generation, or employment status. All things equal, ethnic identity tends to be more pronounced for the second generation compared to the first and among persons in active employment, echoing the findings of Safi and Simon (Citation2013) on discrimination. They also find that experiences of discrimination have a positive net effect on claiming an origin-based identity. Similarly, some ethnographic studies also document the salience of ethnic identities among immigrant origin groups, yet this research tends to be restricted to certain national origins (see, for instance, Unterreiner (Citation2015) on children from mixed marriages using the TeO post-survey qualitative study or Sabatier (Citation2008) on second generation adolescents).

In contrast, research on the variation of class-based identification across educational and occupational groups is well-established in France (Chauvel Citation2006; Pélage and Poullaouec Citation2007). This is largely due to the predominance of class and socioeconomic inequalities in French sociological perspectives. A common argument is that class consciousness has declined among the working class. Survey data confirms this: Pélage and Poullaouec (Citation2007) find, for instance, that individuals belonging to the upper classes (managers and intellectual professions) or those with high incomes overwhelmingly identify with a social class, while this identity is much less frequent among lower occupational and income groups.

This article builds on these prior analyses with the added value of focusing on both ethnoracial and class identification in France among both minority and majority populations, and examining variations across origin groups, immigrant generation, and socioeconomic lines.

Ethnoracial and class identities among minority and majority populations

Social categorization is a basic cognitive process: individuals draw on perceived markers of race/ethnicity, class, gender, age, sexual orientation etc. to categorize themselves and others (Fiske Citation1998). Individuals can self-categorize in a variety of different groups, and the salience of these identities may change in different social contexts. Social identity theory posits that group identification – no matter the criteria on which it is based – satisfies a basic psychological need for self-esteem derived from the group’s hierarchical position in society (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986).

Prior research suggests that the relative salience of ethnoracial and class identities and the way they articulate might vary across minority and majority populations. When minorities stem from immigration, there are some reasons to think that this articulation will depend on the assimilation process. Socioeconomic status is also thought to play a crucial role. We draw on these streams of the literature to formulate hypotheses that guide the empirical analysis presented below. Given the rarity of large-scale evidence on ethnoracial identification in France, our hypotheses primarily rely on prior evidence from other national contexts.

There is extensive evidence, at least in the U.S., that ethnoracial identity is of lower salience for the White majority (Croll Citation2007; Hartmann, Gerteis, and Croll Citation2009; Jaret and Reitzes Citation1999; McDermott and Samson Citation2005; Torkelson and Hartmann Citation2010). These findings have traditionally been framed by whiteness scholarship as reflecting the invisibility of white privilege and the hegemony of white normativity (Doane Citation1997; Frankenberg Citation1997; Ferguson Citation2004; Ward Citation2008). The unmarked characteristic of whiteness is also traditionally analysed as crucial in legitimizing racial inequality (Roediger Citation1991). This is also true in France, given that the invisibility of whiteness is reinforced by the absence of explicit ethnoracial categories in French society. Emerging research on the question in France stresses how whiteness is an integral part of French national identity and the implicit norm of the racial order (Beaman Citation2019). As far as the majority group is concerned, therefore, this framework would suggest that ethnoracial identities would be relatively weak compared to that of minorities, for whom the persistence of inequality and discrimination likely reinforce the salience of race/ethnicity. Hence, we anticipate that:

H1a. Ethnoracial identification will be lower for the majority group compared to minorities.

H1b: Class identification will be stronger than ethnoracial identification for the majority, while the opposite will be true among minorities.

Assimilation dynamics

When minorities have a migrant background, as is mostly the case in France, ethnoracial and class identities may also depend on immigrant generation as posited by theories of assimilation. Classical assimilation theory stipulates that ethnoracial identity will weaken over time and across immigrant generations. From this perspective, assimilation trends, driven by social mobility, intermarriage and acculturation, are seen as blurring ethnic boundaries related to immigrant background, resulting in a diminished level of identification with ethnic minority groups (Gordon Citation1964; Alba and Nee Citation2003; Sears et al. Citation2003). In the U.K., for instance, Kesler and Schwartzman (Citation2015) show that native-born second generation immigrants are less likely to identify with ethnoracial minorities than first generation immigrants. Thus, we anticipate that the immigrant assimilation process leads to the attenuation of ethnoracial identification across generations:

H2a: Second generation immigrants will have weaker ethnoracial identification than first generation immigrants.

H2b: Non-European origin second generation immigrants will maintain a stronger sense of ethnoracial identity compared to European second generation immigrants.

The effect of socioeconomic status

Research also suggests that socioeconomic status will shape ethnoracial and class identities in different ways across majority and minority populations.

First, evidence from the U.S. shows that socioeconomically disadvantaged whites tend to be more aware of their whiteness (Croll Citation2007; Hartigan Citation1999; McDermott Citation2006). One interpretation is that whites emphasize their ethnoracial identity and express greater in-group solidarity in reaction to the perceived threat of economic and status gains among racial minorities (Jardina Citation2019). Lower SES whites are more likely to feel endangered by this perceived weakening of white racial advantage. This suggests a negative relationship between socioeconomic status and ethnoracial identification among whites. Therefore, we anticipate that:

H3a. Majority members with lower socioeconomic status will have a sharper sense of ethnoracial identity.

Others argue, on the contrary, that more intense exposure to discrimination may strengthen middle and upper-class minorities’ ethnoracial identity. Because they more frequently interact with the majority (at the workplace, in their neighbourhoods), better-off minorities are more often subject to racial hostility, the glass ceiling, and blatant acts of prejudice than lower-class minorities (Gaddis Citation2015; Pattillo Citation2005). This hypothesis is also consistent with the so-called integration paradox, according to which highly educated minorities, compared to their less educated counterparts, are more likely to experience a lower sense of national belonging and are more likely to recognize and denounce discrimination in the host society (Tolsma, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2012; Verkuyten Citation2016; Safi and Simon Citation2013). All of this suggests that increasing class status does not weaken ethnoracial identification among minority groups, and could even reinforce it (Feagin Citation1991; Hajnal Citation2007; Hochschild Citation1995; Pattillo Citation2005). Empirical studies from the U.K. and the U.S. have shown that higher education among immigrants is correlated with greater identification with their ethnoracial group or country of origin (Feliciano Citation2009; Kesler and Schwartzman Citation2015). In light of this literature, we predict that:

H3b: Minorities with high socioeconomic status will have a sharper sense of their ethnoracial identity.

Data and methods

Data come from Trajectories and Origins (TeO), a large, cross-sectional French survey conducted in 2008 on a nationally representative sample of 21,761 individuals (Beauchemin, Hamel, and Simon Citation2018). The sample is based on a stratified sampling method which over-represents respondents with a migrant background to ensure adequate sample sizes. Sampling weights are applied in the descriptive analysis to account for this sampling strategy. The questionnaire deals with a wide range of topics (education, employment, migration history, family formation, etc.) and includes a large set of variables related to identity and sense of belonging.

TeO is one of the rare French data sources to provide detailed information on migration background and migration trajectory. Following standard classification in French public statistics, TeO defines first and second generation immigrants using two main criteria: place of birth and nationality at birth. First generation migrants are respondents who were born abroad as non-French citizens at birth (G1). Second generation immigrants are respondents with at least one parent born abroad as a non-French citizen at birth (G2). All individuals who were French by birth citizens with two French-born parents constitute the majority group. Since the age range for second generation immigrants in TeO is from 18 to 50, we restrict the sample to respondents within the same age interval (N = 18,668).Footnote4

We group minorities into origin groups based on individual or parental country of birth.Footnote5 North Africans comprise first generation immigrants born in Algeria, Morocco or Tunisia, as well as second generations with at least one migrant parent born in those countries. Likewise, Sub-Saharan Africans are defined as first and second generation immigrants originating from other African countries, while South-East Asians include first and second generation immigrants from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. First and second generation immigrants from Italy and Spain are also grouped together in one category and their counterparts from other European countries form the EU27 category. Migrants and their descendants from Portugal or Turkey are kept as distinct categories. Other national origins are grouped in a single broad category (“Other”). Finally, we also include a separate category for migrants and their descendants from French overseas departmentsFootnote6 (DOM-TOM).Footnote7

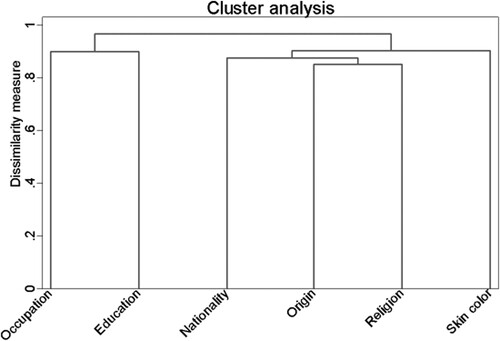

The dependent variable is based on a question about personal identity asking each respondent to select the items that “define him/her the best”. From a list of 15, respondents could choose a maximum of 4 items.Footnote8 On average, respondents chose 2.7 items (standard deviation of 1.24). In a previous study, Simon and Tiberj (Citation2018) extensively described patterns of responses to this question covering all items in detail. In this article, we focus more specifically on the intertwining of two dimensions of personal identity. The first dimension comprises items that can be related to ethnoracial identity: nationality, origin, skin colour, and religion. The second dimension groups together items related to education and occupation: we refer to this as the class dimension.Footnote9 A hierarchical cluster analysis confirms that these 6 items fall into two distinct dimensions (Figure A1 in the Appendix).

It is noteworthy that the measurements of ethnoracial and class identification used in this article differ from those used in prior studies. Subjective assessments of social class generally focus on people’s own reports of where they reside in the class hierarchy or use a question on levels of class consciousness. The question used here captures the importance of typical class dimensions (education and occupation) in shaping personal identity. Similarly, subjective assessments of ethnoracial identification usually use direct self-reported ethnoracial categories or questions on levels of ethnic/racial consciousness. The question used here captures the importance of typical ethnoracial characteristics (origin, religion, skin colour, nationality) with regard to personal identity. One may think that the question about personal identity from TeO is more straightforward and less subject to variation in subjective interpretation. Moreover, it offers a unique opportunity for exploring the articulation of the class and ethnoracial dimensions since it allows the respondents to select among all items simultaneously. Consequently, and conversely to prior research, the articulation between class and ethnoracial identifications can be studied more directly by examining combinations of the two sets of items.

TeO data suggests that, on average, class dimensions are stronger than ethnoracial dimensions in shaping personal identity in France (45 per cent of the population select at least one class item while 36 per cent select at least one ethnoracial item) (). Origin and nationality are the most selected items within the ethnoracial dimension (respectively 19 per cent and 16 per cent) while occupation is more often selected than education within the class dimension (respectively 37 per cent and 12 per cent). also shows that 15 per cent of the French population combines at least one ethnoracial and one class item while 34 per cent do not select any item within these two sets.

Table 1. Patterns of Ethnoracial and Class Identification within the French population.

In order to model not only the marginal probabilities of selecting ethnoracial or class items but also the joint probabilities of combining (or not combining) them, we rely on a bivariate probit model with two binary dependent variables: the first equation (y1) models whether the respondent selects at least one of the ethnoracial items (skin colour, religion, nationality, origin) while the second equation (y2) models whether the respondent selects at least one of the class items (occupation, education). This estimation design jointly models the two outcomes of interest, while also allowing the error terms to be correlated. In the post-estimation stage, this modelling strategy also lends itself to exploring all possible combinations of the two outcomes of interest. This is of particular importance to our perspective since the focus is precisely on the articulation between the class and ethnoracial dimensions of personal identity.

The general model specification is as follows:

ρ is the coefficient of autocorrelation between the residuals of the two equations. Two variations in the model specification are used. A base model controls for respondents’ sex, age, nativity (born in France/foreign born), family status (single/no children, single/one or more children, couple/no children, couple/one child, couple/two children, couple/three or more children), religion (no religion, Christian, Muslim, other religions), education (no education, junior high school, vocational high school, vocational BAC,Footnote10 regular BAC, BAC +2, >BAC +2), occupation (inactive, blue collars, employees, intermediary professions, managers, self-employed, agriculture), income (<p10, p10/p25, p25/p50, p50/p75, p75/p90, >p90, unreported income) and origin (North-Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, Turkey, Portugal, Spain and Italy, EU27, Overseas). We also control for the respondents’ nationality in three categories: only foreign nationality, only French nationality, or binationals (French and another nationality). presents the descriptive statistics for all the control variables. In a second stage, we introduce interaction terms in the model specifications to examine the extent to which the effects of immigrant generation and socioeconomic status vary across origin groups.

Results

Results of the base model are shown in . The coefficient of autocorrelation between the residuals of the two equations (ρ) is significant, which corroborates the relevance of modelling both outcomes simultaneously. Moreover, ρ’s sign indicates that unobserved individual heterogeneities (the residuals of each equation) are negatively correlated. This means that, all things being equal, a certain trade-off exists between selecting class or ethnoracial items since unobserved determinants that favour one tend to disfavour the other. The small magnitude of the correlation nonetheless suggests this trade-off is weak. This tension between class and ethnoracial identities is also observed in the frequently contrasting sign of the coefficients estimated for the same variables across the two equations. In particular, being a woman, not having French citizenship,Footnote11 being of Muslim faith, and having origins in an African country or the French overseas departments are all positively associated with ethnoracial identity, but negatively associated with class identity.

Table 2. Bivariate probit model (base model).

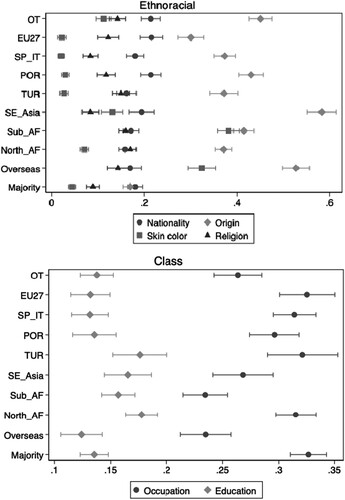

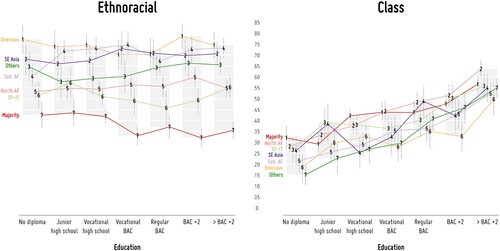

Drawing on regression estimations in , summarizes the effects of origin on both identities using marginal probabilities. The first finding is that differences across origin groups are more important in terms of ethnoracial identification than in terms of class identification. The majority population has the lowest probability of selecting ethnoracial items (0.38), in line with H1a. Minority groups have greater chances of identifying along ethnoracial lines, although there are important differences by origin. The highest probability for ethnoracial identification is measured for French overseas migrants and their descendants (0.74) and migrants and their descendants from Sub-Saharan Africa (0.70), South-East Asia (0.69) and other (non-European) immigrants (0.63). Surprisingly, North Africa and Turkish origins rank lower (0.55 and 0.54 respectively) and are comparable to most European groups in terms of selecting ethnoracial items as important to their personal identity. This suggests that blackness is a crucial dimension of ethnoracial identification in France.Footnote12

Figure 1. Marginal probabilities of ethnoracial and class identification across origins. Source: Trajectories and Origins Survey, 2008.

The class dimension exerts less group-level variability. Except for overseas migrants and respondents with Southeast Asian, Sub-Saharan African and other non-European origins, class identification is not significantly lower for minority groups in comparison to the majority. Nonetheless, the comparison of the two sub-graphs of shows that, compared with ethnoracial characteristics, respondents identify less with their occupation and/or education in all minority groups. More generally, the group comparison highlights a reversed pattern regarding the two dimensions of identification: those who score highest on ethnoracial identity tend to score lower on the class dimension (for instance, the overseas migrants). Majority members identify more with class items than with ethnoracial ones. Again, these patterns suggest a certain trade-off between ethnoracial and class-based identifications. In line with H1b, among the majority, class is stronger than ethnoracial identity, while minorities emphasize ethnoracial identity over class.

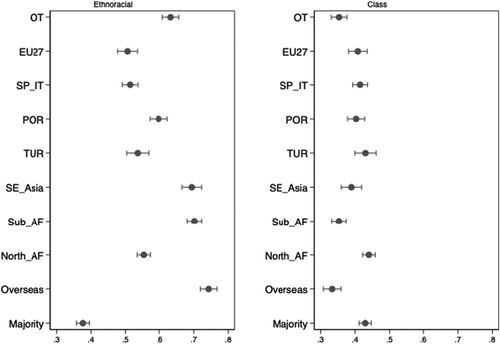

To test for the second set of hypotheses, we introduce interaction terms between origin groups and immigrant generations in an alternative specification of the base model (excluding the French majority). Findings for interaction effects are displayed in , again using marginal probabilities.Footnote13 Contrasting patterns are observed on the two dimensions of identity. In terms of class, generational differences are not found across minority groups as shown by the non-significant interaction effects (). Generational differences are more pronounced when it comes to ethnoracial identification, but only for certain groups. The intergenerational decline in ethnoracial identification is noticeably significant only for Europeans. Second generations from Spain, Italy and EU27 thus seem to converge toward the majority population in terms of their ethnoracial identity, while non-European and overseas second-generation migrants are quite similar to the first generation in this respect. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis of an intergenerational persistence of the salience of race/ethnicity for non-European minorities (H2b).

Figure 2. Marginal probabilities of ethnoracial and class identification across origins and generations. Source: Trajectories and Origins Survey, 2008.

The subsequent analysis focuses on the way socioeconomic status affects ethnoracial and class identification across groups. The base model controls for three standard SES variables: education, occupation and income.Footnote14 As shown in , SES variables very rarely exert significant effects on ethnoracial identification whereas their impact on class identification is decisive. With higher socioeconomic status, whether measured by education, income or occupational attainment, comes a clear increase in class identification.

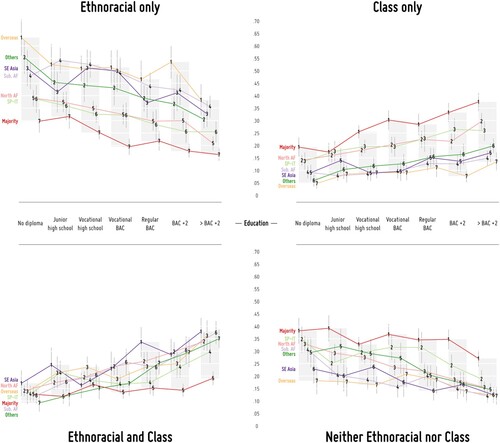

To explore variations in the effect of SES by groups, we introduce an interaction in the base model between educationFootnote15 and origin. Full model results are included in . Interaction effects are overwhelmingly non significant in the class identification equation, as shown in the right sub-graph of .Footnote16 In other words, higher educational levels correspond to greater class identification in a very similar way across groups. Conversely, there are substantial group differences in the impact of education on ethnoracial identification. The left sub-graph in highlights the diverging directions of the educational effect between minority and majority populations. Ethnoracial identification clearly decreases with educational attainment for the majority, in line with H3a. However, its effect on minority populations is generally weaker and most often positive. Increasing ethnoracial identification is indeed significantly measured for highly educated minorities with interaction effects being the most frequently significant for North and Sub-Saharan Africans. These findings support the hypothesis that higher socioeconomic status reinforces ethnoracial identification among minorities, as stated by H3b.

Figure 3. Marginal probabilities of race and class identification across origins and educational levels. Note: These graphs are drawn from the regression model in . Results for Turkey, Portugal and EU27 are not shown because of the small sub-sample size of the interaction terms (N < 100), which impedes the readability of the figures. Source: Trajectories and Origins Survey, 2008.

Further comparison of the two sub-graphs in shows interesting patterns in the combination of ethnoracial and class identifications across groups. While ethnoracial identification is higher than class identification for all minority groups at the bottom of the educational distribution, the level of class identification increases dramatically with educational level and almost reaches the same levels as ethnoracial identification for the most educated. In other words, strong ethnoracial and strong class identifications seem to go hand-in-hand for better-off minorities. The picture is nonetheless quite different for the majority group: while ethnoracial and class identifications are low at the bottom of the educational distribution, the more educated have much higher class identification compared to ethnoracial identification.

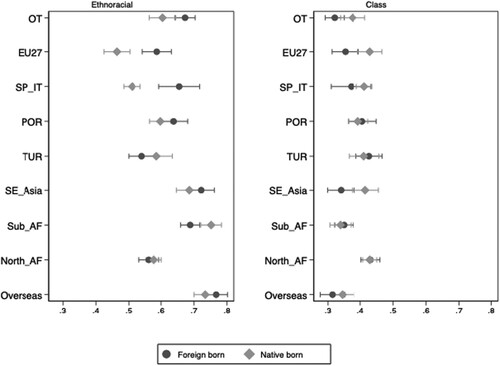

explores the combination of ethnoracial and class identity. The figure shows the effect of education on 4 possible combinations: 2 exclusive patterns of identification (selecting ethnoracial items only versus selecting class items only) and 2 joint patterns of identification (selecting both ethnoracial and class items versus selecting neither ethnoracial nor class items). The results confirm the persistence of group differences in identification patterns: majority respondents are less likely to select ethnoracial items whether alone or combined with class. They are, on the contrary, more inclined to select class items as well as other (non ethnoracial) items. These group disparities remain powerful across the educational distribution. Yet examining the combination of ethnoracial and class identities further enriches our interpretation of the effect of education. In the upper-left sub-graph, exclusive ethnoracial identity is shown to clearly decrease with education for all groups. The effect is more clearly graduated and significant for the majority population: the most educated among them identify much less exclusively with ethnoracial items in comparison with the less educated. This suggests that, as far as the majority group is concerned, heightened ethnoracial identification is a matter of economic deprivation. The “race trumps class” assertion therefore seems specifically relevant for disadvantaged majority members, for whom ethnoracial identity may be regarded as a defensive identity which tends to offset class identification. On the other hand, minority groups clearly combine ethnoracial and class identification with significantly increasing trends along the educational gradient (lower left-side of the figure). This finding allows us to enrich H3b: minorities with high SES not only have a sharpened sense of ethnoracial identity, but also a reinforced class identity. Ethnoracial identification goes hand-in-hand with class identification and does so increasingly as minorities climb the socioeconomic ladder.

Figure 4. Joint probabilities of class and ethnoracial identities. Note: These graphs are drawn from the regression model in . Results for Turkey, Portugal and EU27 are not shown because of the small sub-sample size of the interaction terms (N < 100), which impedes the readability of the figures. Source: Trajectories and Origins Survey, 2008.

Conclusion

Using a unique dataset, this article provides systematic empirical evidence on patterns of personal identity in France. In tackling this issue, the article takes an intersectional perspective, focusing on the articulation of ethnoracial and class identification, and examining the effect of immigrant origin, generation and socioeconomic determinants and their interaction. In this way, it offers an all-encompassing overview of the mechanisms shaping subjective identity in French society.

The findings highlight the importance of migration in the formation of social identities in France. In all the analyses, groups were defined on the basis of their migratory background up to the second generation. This migration-based classification consistently highlights disparate patterns of identification between the majority population, on the one hand, and groups stemming from migration, on the other hand. Nevertheless, comparing origin groups within minorities hints at other group markers (such as skin colour, phenotype, and cultural attributes) that may drive meaningful distinctions between migrant groups. This is shown by the increased intensity of ethnoracial identification when one moves from European to non-European origins, and the particularly high level of ethnoracial identification of black groups (such as overseas migrants and sub-Saharan migrants).

Moreover, the examination of intergenerational trends sheds light on assimilation patterns in social identities. Counter to what classical assimilation theory would predict, among non-European origins specifically, second generations are not less likely to identify with ethnoracial items than their first generation counterparts. This is in line with prior studies documenting that non-European origin second generations are also more aware of discrimination and more likely to report it than first generations (Safi and Simon Citation2013). This pattern moreover gives credit to a form of reactive ethnicity (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001), whereby ethnoracial identity is sustained among the second generation likely due to experiences of discrimination and exclusion. It is noteworthy that while migrant generation matters to ethnoracial identity, it does not come into play in the salience of class identity which, in contrast, does not vary by generation.

Further, the joint examination of ethnoracial and class identification by ethnoracial group and socioeconomic status proves to be highly fruitful in terms of understanding patterns of group identity. The findings in this regard can be summarized as follows.

First, the effect of education on class identification is similar for majority and minorities. This is in contrast to some evidence showing that SES is less decisive for minorities’ class identification compared to their effects on the majority group (Hunt and Ray Citation2012; Hout Citation2008). Rather, in line with earlier research in France (Pélage and Poullaouec Citation2007), higher socioeconomic status is associated with stronger class identification for everyone.

Second, there is no evidence that ethnoracial identification weakens as socioeconomic status increases within minority groups. On the contrary, higher socioeconomic attainment tends to reinforce ethnoracial identity. This finding can be understood in light of prior research from France and other contexts documenting that high-SES minorities are more likely to report discrimination (Safi and Simon Citation2013) and less likely to identify with the majority group (Simon and Tiberj Citation2018; Kesler and Schwartzman Citation2015). Thus, completing a “successful” integration trajectory and achieving upper-class status does not eliminate the racism and discrimination to which minorities are exposed and through which ethnoracial identity could be maintained. This interpretation is consistent with qualitative research from France documenting the awareness of persistent race-based marginalization and stigma among upwardly mobile North African second generation immigrants (Naudet and Shahrokni Citation2019; Beaman Citation2015).

Third, socioeconomic background affects the intersection of ethnoracial and class identifications in different ways across groups. Rather than offsetting ethnoracial identity, higher socioeconomic status tends to reinforce both class and ethnoracial identities among minorities. Qualitative research from France again resonates with this finding, as upwardly mobile minorities maintain a sense of class identity along with strong racial consciousness. This emerges in part from their awareness that the French elite is equated with whiteness, and the resulting impression that they must work twice as hard to succeed, while never feeling fully legitimate in their class position (Naudet and Shahrokni Citation2019). Hence, there does not appear to be a trade-off between minorities’ class and race identities: both are salient, perhaps precisely because of the experience of otherness on both dimensions.

In contrast, for the majority, increased socioeconomic status reinforces class identity and weakens ethnoracial identity. The trade-off between ethnicity/race and class therefore seems to be the most intense for the disadvantaged segments of the majority population, as though for this group, race consciousness stands in for class consciousness. This finding in particular bears political implications. The bolstered sense of ethnoracial identity among deprived majority members is in line with the rise in white identity politics (Jardina Citation2019) that has galvanized support for the far right in recent elections. This is particularly the case in France, where the far-right National Rally (formerly known as the National Front) has solidified its political platform around national identity, anti-immigrant rhetoric as well as claims of anti-white racism in French society (Bell Citation2022). Survey data shows that despite efforts to “dedemonize” the party’s image, overtly racist views are still rampant among supporters (Mayer Citation2018), and low socioeconomic status is a key predictor of the far-right vote (Gougou and Mayer Citation2012). Deprived majority members may perceive minorities as a threat to their group’s status and power, echoing the notion of ethnoracial identity as a sense of group position (Blumer Citation1958; Bobo Citation1999). By emphasizing race, disadvantaged majority members could further derive self-esteem from their dominant position in the ethnoracial hierarchy.

Overall, our findings suggest that disadvantaged majority and minority groups might not react similarly to redistributive policies and could explain the difficulty of left-wing parties to unite both sets of voters. What’s more, our findings put into perspective the homogenous representation of contemporary political divisions as structured by the tension between attitudes towards migration and attitudes towards redistribution (Piketty Citation2018). Future research may gain from incorporating the role of minority populations, for whom these two concerns go more hand in hand rather than in opposition, in shaping the current political landscape.

The analyses presented in this article nonetheless present several limitations which provide avenues for future research. Our focus on the individual determinants of social identity neglects the meso channel: the impact of the class and ethnoracial composition of neighbourhoods and workplaces may constitute interesting directions for future studies. A more general critique can also be addressed to the use of a broad question on how respondents define themselves. More research is needed using other types of subjective class measures (such as self-assessment of class position or class consciousness). In the absence of self-reported ethnoracial categories in French data (and their unlikely introduction in the near future), questions that ask respondents to evaluate the importance of their ethnoracial identity may constitute interesting alternatives. While voices in favour of introducing such questions have been increasingly audible within migration scholarship in France over the last decades, the present study suggests that taking the ethnoracial dimension of subjective identity into account might also enrich social stratification research. Finally, as more data become available, future studies could explore whether the magnitude of ethnoracial and class identities have changed since this 2008 survey, along with the increased salience of race and socioeconomic inequalities in public debate in the past decade in France and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yannick Savina for his help in the production of and .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Intersectionality scholars have called for examining how social hierarchies (such as race, class and gender) combine and overlap, producing specific forms of inequalities (McCall Citation2001; Cho Citation2013). Research in this vein illuminates how categories interact in shaping individual outcomes and perceptions of inequality (Harnois Citation2014; Penner and Saperstein Citation2013). Our approach to intersectional identities involves exploring two dimensions of identity – class and race – simultaneously, and investigating how individual characteristics such as migratory background and education interact to shape these outcomes.

2 There is an ongoing debate about the relevance of the distinction between ethnicity and race (Brubaker Citation2009; Cornell and Hartmann Citation2004; Jenkins Citation1994; Omi and Winant Citation1994; Saperstein, Penner, and Light Citation2013; Wimmer Citation2013). In the absence of a conventional distinction between these terms in France and the substantial overlapping in their meaning, we choose the term “ethnoracial”.

3 These migrants are French citizens born in a DOM-TOM (the French acronym for “Départements et territoires d’Outre-Mer”) who have migrated to mainland France. Guadeloupe, Martinique, and La Réunion are the home départements of by far the largest numbers of overseas migrants in metropolitan France.

4 Observations with missing values for occupation or education were dropped. As missing values for reported income are sizeable (10% of the sample), we include them within a separate category.

5 For the rare second generations in the sample with two immigrant parents from two different countries, ego’s origin is aligned with the father’s country of birth.

6 While these respondents were born in France, they are categorized as migrants (G1) or descendants of migrants (G2) to the extent that they or their parents migrated to mainland France.

7 These origin categories were selected on the basis of subsample size and within-group consistency in terms of the dependent variable. Analyses using more detailed categories do not alter the results.

8 The question can be translated as: “According to you, which of the following characteristics define you best? You may choose a maximum of four”. The listed items were: your generation or your age/your sex/your occupation or social category/your educational level/your neighbourhood or city/your state of health, disability or illness/your nationality/your origins/your skin colour/your region of origin/your religion/your centres of interest or your passions/your political opinions/your family situation/something else. To reduce ordering effects, the sample was split and given lists in different orders.

9 While class usually refers to a hierarchical model of social stratification, we use the term here as a synonym of socioeconomic status (SES). Education and occupation are widely used as major components of SES.

10 BAC stands for “baccalauréat” which is the equivalent of a high school diploma.

11 It is also noteworthy that respondents with dual citizenship (French and foreign nationality) are more likely than those with only French citizenship to select ethnoracial items, indicating that gaining French citizenship does not reduce ethnoracial consciousness. On the contrary, the ethoracial dimension is even more salient among those with hyphenated national identities than among foreigners.

12 As a robustness test, we ran the base model including each ethnoracial and class item as separate dependent variables (namely, nationality, origin, skin colour, religion, occupation, education). These findings are plotted in Figure A2 in the Appendix and are consistent with . Skin colour is the least frequently cited ethnoracial item, yet it is significantly higher for those with origins in Sub-Saharan Africa and the overseas departments. Religion is consistently higher for African, Turkish and overseas respondents. All minority groups are more likely to cite origin as an identity dimension compared to the majority, with again the highest probabilities found for non-European origins (overseas and Asian respondents). Finally, nationality shows the least variation across groups.

13 Full model results including the interaction between origin and immigrant generations are not shown for sake of concision but may be obtained upon request.

14 We tested for multicollinearity using VIF and did not detect problematic multi-correlations in the model.

15 We also tested interactions between income and origin and occupation and origin, which show similar patterns. Since interactions with education are the most frequently significant, we chose to display them here.

16 The rare significant interaction effects measure a more intense impact of higher level of education on immigrants grouped in the category “others”, for North Africans who have university degrees, and some origins with junior high school education (overseas, South-East Asia, Spain and Italy).

References

- Adida, Claire, David Laitin, and Marie-Anne Valfort. 2014. “Muslims in France: Identifying a Discriminatory Equilibrium.” Journal of Population Economics 27: 1039–1086. doi:10.1007/s00148-014-0512-1.

- Aeberhardt, Romain, Denis Fougère, Julien Pouget, and Roland Rathelot. 2010. “Wages and Employment of French Workers with African Origin.” Journal of Population Economics 23: 881–905. doi:10.1007/s00148-009-0266-3.

- Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream. Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Amiraux, Valérie, and Patrick Simon. 2006. “There are no Minorities Here: Cultures of Scholarship and Public Debate on Immigrants and Integration in France.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 47: 191–215. doi:10.1177/0020715206066164.

- Arnoult, Emilie, Marie Ruault, Emmanuel Valat, Pierre Villedieu, Thomas Breda, Nicolas Jacquemet, Morgane Laouénan, et al. 2021. “Discrimination in Hiring People of Supposedly North African Origin: What Lessons from a Large-Scale Correspondence Test?” Institut des Politiques Publiques halshs-03693421, HAL.

- Beaman, Jean. 2015. “Boundaries of Frenchness: Cultural Citizenship and France’s Middle-Class North African Second-Generation.” Identities 22 (1): 36–52. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2014.931235.

- Beaman, Jean. 2019. “Are French People White?: Towards an Understanding of Whiteness in Republican France.” Identities 26 (5): 546–562. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2018.1543831.

- Beauchemin, Cris, Christelle Hamel, and Patrick Simon. 2018. Trajectories and Origins: Survey on the Diversity of the French Population. Cham: Springer.

- Bell, Dorian. 2022. “White Atlantic: Counterfeiting Race in France.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 26 (4-5): 418–428. doi:10.1080/17409292.2022.2107268.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7. doi:10.2307/1388607.

- Bobo, Lawrence D. 1999. “Prejudice as Group Position: Microfoundations of a Sociological Approach to Racism and Race Relations.” Journal of Social Issues 55 (3): 445–472. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00127.

- Bourabain, Dounia, and Pieter-Paul Verhaeghe. 2019. “Could You Help Me, Please? Intersectional Field Experiments on Everyday Discrimination in Clothing Stores.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (11): 2026–2044. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1480360.

- Brinbaum, Yael, Mirna Safi, and Patrick Simon. 2018. “Discrimination in France: Between Perception and Experience.” In Trajectories and Origins: Survey on the Diversity of the French Population, edited by C. Beauchemin, C. Hamel, and P. Simon, 195–222. Cham: Springer.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 21–42. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916.

- Cédiey, Eric, Fabrice Foroni, and Hélène Garner. 2008. “Discriminations à l'embauche fondées sur l'origine à l'encontre de jeunes français(es) peu qualifié(e)s. Une enquête nationale par tests de discrimination ou testing.” Dares.

- Chauvel, Louis. 2006. Les classes moyennes à la dérive. Paris: Seuil.

- Cho, Sumi. 2013. “Post-Intersectionality: The Curious Reception of Intersectionality in Legal scholarship.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 10 (2): 385–404. doi:10.1017/S1742058X13000362.

- Cornell, Stephen, and Douglas Hartmann. 2004. “Conceptual Confusions and Divides: Race, Ethnicity, and the Study of Immigration.” In Not Just Black and White: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States, edited by N. Foner, and G. Frederickson, 23–41. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Croll, Paul R. 2007. “Modeling Determinants of White Racial Identity: Results from a New National Survey.” Social Forces 86: 613–642. doi:10.1093/sf/86.2.613.

- Dawson, Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- De Rudder, Véronique, Christian Poiret, and François Vourc’h. 2000. L’inégalité raciste. L’universalité républicaine à l’épreuve. Paris: PUF.

- Di Stasio, Valentina, and Edvard N. Larsen. 2020. “The Racialized and Gendered Workplace: Applying an Intersectional Lens to a Field Experiment on Hiring Discrimination in Five European Labor Markets.” Social Psychology Quarterly 83 (3): 229–250. doi:10.1177/0190272520902994.

- Doane, Ashley W. 1997. “Dominant Group Ethnic Identity in the United States: The Role of “Hidden” Ethnicity in Intergroup Relations.” The Sociological Quarterly 38: 375–397. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1997.tb00483.x

- Donnaloja, Victoria, and Haley McAvay. 2022. “The Multidimensionality of National Belonging: Patterns and Implications for Immigrants’ Naturalisation Intentions.” Social Science Research 106: 102708. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2022.102708.

- Fassin, Eric, and Didier Fassin. 2006. De la question sociale à la question raciale ? Représenter la société française. Paris: La découverte.

- Fassin, Didier, and Sarah Mazouz. 2007. “Qu’est-ce que devenir français? La naturalisation comme rite d’institution républicain.” Revue française de sociologie 48 (4): 723–750. doi:10.3917/rfs.484.0723

- Feagin, Joe R. 1991. “The Continuing Significance of Race: Antiblack Discrimination in Public Places.” American Sociological Review 56: 101–116. doi:10.2307/2095676.

- Feliciano, Cynthia. 2009. “Education and Ethnic Identity Formation among Children of Latin American and Caribbean Immigrants.” Sociological Perspectives 52 (2): 135–158. doi:10.1525/sop.2009.52.2.135.

- Ferguson, Roderick. 2004. Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique. Minneapolis: Univesrity of Minnesota Press.

- Fiske, Susan T. 1998. “Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination.” In The Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, 357–411. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Frankenberg, Ruth. 1997. Displacing Whiteness: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Frickey, Alain, and Jean-Luc Primon. 2006. “Une double pénalisation pour les non-diplômées du supérieur d'origine nord-africaine?” Formation Emploi, 27–43. doi:10.4000/formationemploi.2233.

- Gaddis, S. Michael. 2015. “Discrimination in the Credential Society: An Audit Study of Race and College Selectivity in the Labor Market.” Social Forces 93 (4): 1451–1479. doi:10.1093/sf/sou111.

- Gordon, Milton Myron. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gougou, Florent, and Nonna Mayer. 2012. “The Class Basis of Extreme Right Voting in France: Generational Replacement and the Rise of New Cultural Issues (1984–2007).” In Class Politics and the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 174–190. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Hajjat, Abdellali. 2012. Les frontières de l’ “identité nationale": l'injonction à l'assimilation en France métropolitaine et coloniale. Paris: La Découverte.

- Hajnal, Z. L. 2007. “Black Class Exceptionalism: Insights from Direct Democracy on the Race versus Class Debate.” Public Opinion Quarterly 71 (4): 560–587. doi:10.1093/poq/nfm034.

- Harnois, Catherine. 2014. “Are Perceptions of Discrimination Unidimensional, Oppositional, or Intersectional? Examining the Relationship among Perceived Racial–Ethnic-, Gender-, and Age-Based Discrimination.” Sociological Perspectives 57 (4): 470–487. doi:10.1177/0731121414543028.

- Hartigan, John. 1999. Racial Situations. Class Predicaments of Whiteness in Detroit. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hartmann, Douglas, Joseph Gerteis, and Paul R. Croll. 2009. “An Empirical Assessment of Whiteness Theory: Hidden from How Many?” Social Problems 56: 403–424. doi:10.1525/sp.2009.56.3.403.

- Hochschild, Jennifer L. 1995. Facing up to the American Dream: Race, Class, and the Soul of the Nation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hout, Michael. 2008. “How Class Works: Objective and Subjective Aspects of Class since the 1970s.” In Social Class: How Does It Work?, edited by A. Lareau, 25–64. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Hunt, Matthew O., and Rashawn Ray. 2012. “Social Class Identification Among Black Americans: Trends and Determinants, 1974–2010.” American Behavioral Scientist 56: 1462–1480. doi:10.1177/0002764212458275.

- Jackman, Mary R., and Robert W. Jackman. 1983. Class Awareness in the U.S. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Jardina, Ashley. 2019. White Identity Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jaret, Charles, and Donald C. Reitzes. 1999. “The Importance of Racial-Ethnic Identity and Social Setting for Blacks, Whites, and Multiracials.” Sociological Perspectives 42 (4): 711–737. doi:10.2307/1389581.

- Jayet, Cyril. 2016. “Se sentir français et se sentir vu comme un Français: Les relations entre deux dimensions de l’appartenance nationale.” Sociologie 7 (2): 113–132. doi:10.3917/socio.072.0113.

- Jenkins, Richard. 1994. “Rethinking Ethnicity: Identity, Categorization and Power.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 17: 197–223. doi:10.1080/01419870.1994.9993821.

- Kesler, Christel, and Luisa Farah Schwartzman. 2015. “From Multiracial Subjects to Multicultural Citizens: Social Stratification and Ethnic and Racial Classification among Children of Immigrants in the United Kingdom.” International Migration Review 49 (3): 790–836. doi:10.1111/imre.12101.

- Lorcerie, Françoise. 2007. “Le primordialisme français, ses voies, ses fièvres.” In La situation postcoloniale. Les postcolonial studies dans le débat français, edited by M.-C. Smouts, 298–343. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

- Masclet, Olivier. 2012. Sociologie de la diversité et des discriminations. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Mayer, Nonna. 2018. “The Radical Right in France.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren, 433–451. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McCall, Leslie. 2001. Complex Inequality: Gender, Class, and Race in the New Economy. New York: Routledge.

- McDermott, Monica. 2006. Working-Class White: The Making and Unmaking of Race Relations. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- McDermott, Monica, and Frank L. Samson. 2005. “White Racial and Ethnic Identity in the United States.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 245–261. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122322.

- Meurs, Dominique, Ariane Pailhé, and Patrick Simon. 2006. “The Persistence of Intergenerational Inequalities Linked to Immigration: Labour Market Outcomes for Immigrants and Their Descendants in France.” Population (English Edition) 61: 645–682. doi:10.3917/pope.605.0645

- Naudet, Jules, and Shirin Shahrokni. 2019. “The Class Identity Negotiations of Upwardly Mobile Individuals Among Whites and the Racial Other: A USA-France Comparison.” In Elites and People. Challenges to Democracy, edited by F. Engelstad, T. Gulbrandsen, M. Mangset and M. Teigen, 137–158. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

- Nawyn, Stephanie J., and Linda Gjokaj. 2014. “The Magnifying Effect of Privilege: Earnings Inequalities at the Intersection of Gender, Race, and Nativity.” Feminist Formations 26: 85–106. doi:10.1353/ff.2014.0015.

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 1994. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Pattillo, Mary. 2005. “Black Middle-Class Neighborhoods.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 305–329. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.095956.

- Pélage, Agnès, and Tristan Poullaouec. 2007. “Le haut du panier d'en bas? Le sentiment d'appartenir à une classe sociale chez les professions intermédiaires.” Revue française des affaires sociales, 27–56. doi:10.3917/rfas.072.0027

- Penner, Andrew M., and Aliya Saperstein. 2013. “Engendering Racial Perceptions: An Intersectional Analysis of How Social Status Shapes Race.” Gender & Society 27 (3): 319–344.

- Petit, Pascal, Emmanuel Duguet, and Yannick L'Horty. 2015. “Discrimination résidentielle et origine ethnique: Une étude expérimentale sur les serveurs en Île-de-France.” Economie et Prévision 206: 55–69. doi:10.3406/ecop.2015.8183

- Piketty, Thomas. 2018. “Brahmin Left vs Merchant Right: Rising Inequality and the Changing Structure of Political Conflict.” WID. World Working Paper 7.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Rubén G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press and Russell Sage Foundation.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. doi:10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Quillian, Lincoln, Anthony Heath, Devah Pager, Arnfinn H. Midtbøen, Fenella Fleischmann, and Ole Hexel. 2019. “Do Some Countries Discriminate More Than Others? Evidence from 97 Field Experiments of Racial Discrimination in Hiring.” Sociological Science 6: 467–496. doi:10.15195/v6.a18.

- Roediger, David R. 1991. The Wages of Whiteness. Race and the Making of the American Working Class. San Francisco, CA: Verso.

- Sabatier, Colette. 2008. “Ethnic and National Identity among Second-Generation Immigrant Adolescents in France: The Role of Social Context and Family.” Journal of Adolescence 31 (2): 185–205. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.001.

- Safi, Mirna. 2013. Les inégalités ethno-raciales. Paris: La Découverte.

- Safi, Mirna, and Patrick Simon. 2013. “Les discriminations ethniques et raciales dans l'enquête Trajectoires et Origines : représentations, expériences subjectives et situations vécues.” Economie et statistique 464: 245–275. doi:10.3406/estat.2013.10240

- Saperstein, Aliya, Andrew M. Penner, and Ryan Light. 2013. “Racial Formation in Perspective: Connecting Individuals, Institutions, and Power Relations.” Annual Review of Sociology 39:359-378. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145639.

- Sears, David O., Fu, Mingying, Henry, Peter J., and Kerra Bui. 2003. “The Origins and Persistence of Ethnic Identity among the "New Immigrant" Groups.” Social Psychology Quarterly 66: 419–437. doi:10.2307/1519838

- Simon, Patrick. 2008a. “Les statistiques, les sciences sociales françaises et les rapports sociaux ethniques et de ‘race.’” Revue Française de Sociologie 49:153–162. doi:10.3917/rfs.491.0153

- Simon, Patrick. 2008b. “The Choice of Ignorance: The Debate on Ethnic and Racial Statistics in France.” French Politics, Culture and Society 26: 7–31.

- Simon, Patrick, and Joan Stavo-Debauge. 2004. “Les politiques anti-discrimination et les statistiques. Paramètres d'une incohérence.” Sociétés Contemporaines 53: 57–84. doi:10.3917/soco.053.0057.

- Simon, Patrick, and Vincent Tiberj. 2018. “Registers of Identity. The Relationships of Immigrants and Their Descendants to French National Identity.” In Trajectories and Origins: Survey on the Diversity of the French Population, edited by C. Beauchemin, C. Hamel, and P. Simon, 277–305. Cham: Springer.

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Turner. 1986. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by S. Worchel, and W. Austin, 7–24. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

- Tiberj, Vincent, and Laure Michon. 2013. “Two-Tier Pluralism in ‘Colour-Blind’ France.” West European Politics 36: 580–596. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.773725.

- Tolsma, Jochem, Marcel Lubbers, and Mérove Gijsberts. 2012. “Education and Cultural Integration among Ethnic Minorities and Natives in the Netherlands: A Test of the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 793–813. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2012.667994.

- Torkelson, Jason, and Douglas Hartmann. 2010. “White Ethnicity in Twenty-First-Century America: Findings from a New National Survey.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33: 1310–1331. doi:10.1080/01419870903434495.

- Unterreiner, Anne. 2015. “From Registers to Repertoires of Identification in National Identity Discourses: A Comparative Study of Nationally Mixed People in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15 (2): 251–271. doi:10.1111/sena.12140.

- Valfort, Marie-Anne. 2015. Religious Discrimination in Access to Employment: A Reality. Paris: Institut Montaigne.

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2016. “The Integration Paradox: Empiric Evidence from the Netherlands.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (5-6): 583–596. doi:10.1177/0002764216632838.

- Ward, Jane. 2008. “White Normativity: The Cultural Dimensions of Whiteness in a Racially Diverse LGBT Organization.” Sociological Perspectives 51: 563–586. doi:10.1525/sop.2008.51.3.563.

- Waters, Mary. 1994. “Ethnic and Racial Identities of Second-Generation Black Immigrants in New York City.” International Migration Review 28 (4): 795–820. doi:10.1177/019791839402800408.

- Waters, Mary. 1999. Black Identities. West Indian Immigrant Dreams and American Realities. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wilson, William J. 1978. The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Wilson, William J. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making. Institutions, Power, Networks. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Zschirnt, Eva, and Didier Ruedin. 2016. “Ethnic Discrimination in Hiring Decisions: A Meta-Analysis of Correspondence Tests 1990–2015.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (7): 1115–1134. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1133279.