ABSTRACT

Officer-involved shootings (OIS) of people of color concern fundamental societal issues, including race, violence, and policing. While scholars have gathered extensive insights on contextual circumstances of OIS, the unfolding of encounters still remains a black box, and research is still debating whether racialized biases actually matter for shootings. To study this question, this article discusses findings from an in-depth analysis of real-life OIS as they unfold. It triangulates video footage with document data to analyze the role of racial biases and situational interaction in shootings. It compares police shootings of black and white citizens, as well as a police-citizen encounter that did not end in a shooting. Findings suggest two intertwined processes of dehumanization contribute to the shootings of black citizens, one operating on the cultural and one on the situational level. The article contributes to research on race and racism, violence, police use of lethal force, and sociological theory.

Introduction

Officer-involved shootings (OIS) of people of color are one of the most divisive topics of the twenty-first century and concern fundamental societal issues like race, violence, and policing. Research has shown that racist stereotypes associating black men with “the iconic ghetto”—i.e. casting them as criminal and dangerous—prevail (Anderson Citation2012b, Citation2015) and that black men are more likely to be stopped by police and more likely to be unarmed when shot by officers (e.g. Correll et al. Citation2007). Yet other scholars question the relevance of racial biases. Given even biased officers do not shoot in most interactions with people of color, an open question is: If racial biases exist and are relevant, why are they activated in some instances and not others? Recently, violence researchers argue not racial bias, but situational interaction dynamics are key to causing shootings (Collins Citation2008, Citation2009).

So far, we lack an in-depth understanding of whether biases play out in encounters that result in fatal shootings. Such an in-depth analysis is now possible due to technological advancements (Nassauer and Legewie Citation2022; see also McCluskey and Uchida Citation2023; Sytsma, Chillar and Piza Citation2021): Drawing on available video data of shootings—including body-worn cameras (BWC), surveillance cameras (CCTV), and/or dash cam footage—in combination with document data, scholars can now examine why and how a police stop took place, officers’ expectations approaching the situation, how they interacted during the encounter, their interpretations of the situation, and how the shooting took place. These newly available data can be used to assess whether biases played into the encounter, and what role situational interactions (e.g. movement, gestures, body posture, speech, timing, and space) played in the shootings. Employing these data, I conduct a qualitative in-depth analysis of a probability probe (Levy Citation2008): I study three cases of black citizensFootnote1 shot by officers and compare them to the OIS of a white citizen and to a police-citizen encounter that did not end in a shooting.

This study thereby makes two main contributions to the literature. It is, to my knowledge, one of the first to take a detailed look at real-life police-citizen encounters that end in fatal shootings as they unfold. In doing so, it examines the role of racialized biases in interaction dynamics leading to shootings and highlights how these novel data types can help analyze OIS. Second, the study suggests two intertwined processes of dehumanization lead to OIS of black citizens: racialized othering that works on the cultural level, and a process of obscured personhood that works on the situational level.

Racial bias and officer use of lethal force

Lethal officer-involved shootings represent an extreme case of police-citizen interaction: Police rarely use force, not all police shootings are lethal, and the use of force does not need to involve a firearm (Stoughton, Noble, and Alpert Citation2020). Yet lethal OIS are the most consequential for victims and their families and spark large public debates.

As an extensive amount of literature investigates the role of biases in officer use of force, a detailed review lies beyond the scope of this article (but see, among others, VerBruggen Citation2022). Overall, research highlights that while OIS exist around the world (see, among many others, Caldeira Citation2002; Gravett Citation2017; Koerner and Staller Citation2022), the US shows higher rates than most countries. In addition, research shows black men in the US are more than twice as likely as white citizens to be unarmed when shot (Nix et al. Citation2017) and officers are more likely to shoot a black suspect mistakenly than a white suspect (e.g. Sherman Citation1980; Plant and Peruche Citation2005; Ross Citation2015). Police not only shoot armed black suspects more quickly and more frequently, but they also decide more quickly against shooting if the suspect is white (Correll et al. Citation2007; Mekawi and Bresin Citation2015; Nix et al. Citation2017, but see Worrall et al. Citation2018).

One group of studies therefore suggests racial biases affect officer decision-making in the US (see, among others, Goff Citation2016; Eberhardt Citation2020). Studies show that citizens who are black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), black men in particular, are stopped more frequently (Alexander Citation2012; Plümecke, Wilopo, and Naguib Citation2022). They are also perceived as more threatening and dangerous, which creates a deficit of credibility shown to favour officer use of force (Parker et al. Citation2005; Klinger et al. Citation2016). Studies also suggest police embrace racially different styles of police masculinity, with aggressive warrior brand enforcements against BIPOC citizens and guardian brand protection towards white citizen (Carlson Citation2020). Research further highlights policing strategies, like hotspot and stop-and-frisk policing, contribute to discriminatory practices that shape racialized use of force (Siegel Citation2020).

Yet a second group of research questions the role of biases in the use of force and suggests situational interaction dynamics between officer and citizens are vital (Collins Citation2008; Makin et al. Citation2019; Piza et al. Citation2022). They argue racism is often the culturally available interpretation when white officers use violence against black citizens, but that racism is not “the whole story, or even the most important part of the dynamic” (Collins Citation2009, 572). Scholars claim racism, like other context factors (e.g. police strategies, training, or culture) cannot fully explain the emergence of violence, because officer use of force is rare. Even most explicitly racist individuals never kill another human, and even most stop-and-frisk encounters end peacefully. Further, a connection between the readiness for interpersonal violent action (e.g. because of racist attitudes) and using violence is not evident in systematic studies of when and where violence emerges (Collins Citation2009; Jackson-Jacobs Citation2013; Piza and Sytsma Citation2022a). Thus, scholars argue situational dynamics—the interactions, interpretations, and emotions in the minutes and seconds before violence breaks out—are key for social outcomes, including the use of violence (Collins Citation1981; Stoughton, Noble, and Alpert Citation2020). Collins (Citation2009, 572) states “even racists need a micro-situational advantage which allows the release of violence.”

Existing research faces two main gaps this article aims to address. First, both explanatory approaches face challenges. If racialized biases are key to OIS, as one line of research argues, why do officers not use force in most encounters with BIPOC citizens? On the other hand, if situational dynamics are key, as the other line of research assumes, why are BIPOC disproportionately affected by OIS and more quickly shot as well as more likely unarmed when shot?

Second, research pays little attention to how real-world shootings unfold (Klinger et al. Citation2016; Willits and Makin Citation2018). Driving dynamics in real-life OIS, between the moment officer(s) and citizens(s) meet until force is used, remain a black box, and we know little about the situational interaction dynamics that might shape the perspective of officers during situations in which they apply force (Klinger and Brunson Citation2009; Pryor, Buchanan, and Goff Citation2020). It therefore remains unclear if biases exist and how they get activated. Further, officers’ threat perception is particularly interesting, yet understudied, when the citizen is not showing any threatening behavior.

In short, we lack an in-depth understanding of how interactions, interpretations, and meaning-making unfold in real-life encounters leading to a shooting and whether or not these interactions are shaped by racialized biases.

Methodology

Question and cases

To fill the discussed research gaps, this article asks: What are driving dynamics in officer-involved shootings of black citizens? To trace driving dynamics of OIS, I analyze five cases in great detail through a plausibility probe (Levy Citation2008). Plausibility probes are comparable to a pilot study: They analyze a single or a limited number of cases as illustrative case studies to sharpen hypotheses or explore the sustainability of theories and refine operationalizations of key variables. They often lie between hypothesis testing and generating; in the case of this study, two theoretical strands are examined to generate more precise hypotheses on OIS and develop saturated theoretical claims (Small Citation2009). This means the importance of such small numbers of cases lies in what they tell us about society and sociological theories, not about the population of similar cases. Cases were not selected due to the presence or likelihood of any context or situational factors, but because they allow in-depth insights to test and refine sociological theory. I thereby follow a case selection logic common in qualitative research that targets theoretical saturation rather than representation (e.g. Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). The comparison of cases involving black and white citizens and shooting versus non-shooting cases allows making meaningful contributions to our knowledge on OIS (Small Citation2009).

For case selection, I compiled a list of 21 prominent and thus well-documented OIS of black citizens in the United States (AFP / Reuters Citation2015; Lee and Park Citation2017). Three of these 21 cases show enough data to analyze the research question (including video data that captures the entire situational encounter; see below). I compare these three cases to a shooting of a white citizen, as well as to a negative case that did not end in a shooting (for details, see Appendix A in the online supplementary material).

Data

I analyzed a variety of video and document data available for each event, stopping data collection when saturation (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998) was met (on average, five videos and 20 documents per case). I analyzed two types of data:

Video data included videos captured by police body cameras, police dash cams, on CCTV, and on a mobile phone. The videos capture the entire interaction, from when the officers and citizen start interacting until after shots were fired (or in the case without a shooting, until the interaction stopped because the citizen left the scene).

Document data included police reports, court documents, media reports, and media and police interviews with the shooter and/or bystanders (between 20–30 documents per case).

I rely most strongly on the video evidence and what was said in the video and during police radio calls. I employ document data to study the role of context factors, including racial biases, leading into the situation, including how police were called and what information they had when they arrived. Document data and witness’ statements can also provide information on actions by individuals not visible in the recordings. I critically assess these data and all ex-post statements.

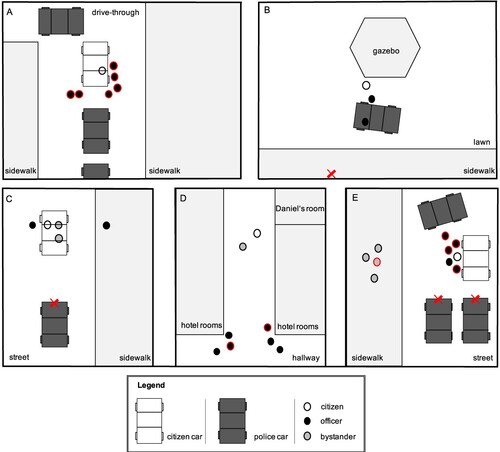

illustrates the camera angles online sources provide for the shootings of (A) Willie McCoy, (B) Tamir Rice, (C) Philando Castile, (D) Daniel Shaver, and (E) Katherine Turner.Footnote2 These recordings are then triangulated with document data to arrive at a second-by-second account as close as possible to what happened during the encounter leading up to the shooting.

All data were accessed online (via YouTube or online searches for newspaper articles, police reports, and court data). This approach favours open science data and transparency of the analysis, as readers can see the data firsthand to verify the results. Despite all data being publicly available, the victims’ inability to give consent to the recordings being analyzed requires critical reflection on the ethics of studying such footage (Salganik Citation2017; Legewie and Nassauer Citation2018). In my view, these data can be considered ethically admissible for research (for a detailed ethics assessment, see Appendix B in the online supplementary material). However, for ethical reasons, YouTube links to the footage analyzed here are omitted. Instead, I provide case vignettes of each analyzed case as well as links to transcripts of the events in Appendix C in the online supplementary material. Readers are encouraged to reflect on whether they want to see the footage, given the potentially traumatizing content. Reading case vignettes and transcripts may be less emotionally impactful. Links to the videos analyzed in this paper are available from the author upon request, as well as through straightforward searches on YouTube.

Video data analysis

I employ Video Data Analysis (VDA; Nassauer and Legewie Citation2021, Citation2022) to conduct a qualitative, in-depth analysis of the dynamics immediately prior to and during office-involved shootings. VDA is a multidisciplinary collection of tools, techniques, and quality criteria intended for analyzing the content of visuals to study real-life driving dynamics at the micro-level. It aims to reconstruct situational sequences in detail, including the context in which they arose, to study social processes, social events, and social life. To do so, VDA uses visual data, caught, for example, on mobile phones, drones, body cameras, and CCTV, often in combination with other data types. Complementary document data is often used if a study aims to assess the role of potential context factors in social situations.

A main goal of VDA is to analyze if a situation shows intrinsic dynamics that contribute to the occurrence of an outcome (in this case, the OIS) or its absence (on using VDA to study OIS, see also Nassauer Citation2022b; McCluskey and Uchida Citation2023). The approach is increasingly used to study policing and crime (e.g. McCluskey et al. Citation2019; Piza and Sytsma Citation2022a; Stickle Citation2020; Sytsma, Chillar and Piza Citation2021).

When using VDA, researchers must ensure data validity regarding three criteria (Nassauer and Legewie Citation2019). First, researchers conducting VDA should strive for optimal capture of the event of interest so that no essential details are missing. In my study, it was therefore vital to include only cases where the entire interaction dynamic was captured on camera. Second, researchers must assess whether videos show natural behavior. In all analyzed cases, the authenticity of the event is confirmed by multiple sources. Further, two factors favour natural behavior (behavior all parties would have displayed without being recorded): Interactions are potentially highly consequential for citizens and officers, and recordings are commonplace in police practices in the US. Third, to ensure validity, researchers should aim for neutral or balanced sources, meaning sources that do not have a stake in the representation of events. This aspect is especially relevant in my study, since officers might justify their actions after the fact in fear of prosecution, or may not correctly remember details if asked ex post (Bernard et al. Citation1984; Nassauer and Legewie Citation2021). I therefore critically assess officers’ ex post statements and rely most strongly on the video evidence and transcripts of police communication to study what happened. To balance and compare accounts, I also actively seek descriptions from the victim’s relatives and friends, as well as other witnesses. In addition, I employ document data to study the role of context factors (see section “Data”).

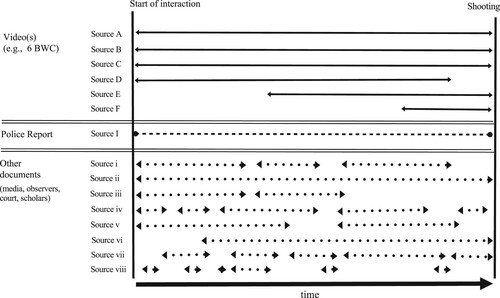

As illustrates, I triangulate video data with document data, aiming to construct detailed timelines of each event. I then examine the interaction sequence, if turning-points existed, and, if possible, officers’ and victim’s expectations, perceptions, and meaning-making throughout the encounter. I coded all cases using Atlas.ti, a program for qualitative data analysis. After analyzing each case, I carried out a cross-case comparison of cases, studying commonalities and differences (for basic procedures in VDA, see Nassauer and Legewie Citation2022).

Findings

Findings suggest that situational interaction dynamics hold key properties for officer-involved shootings, but that these can be shaped by biases. In particular, two intertwined processes of dehumanization contribute to the shootings of BIPOC citizens: First, a process of racialized othering that works on the cultural level, and second, a process of obscured personhood that works on the situational level.

Racialized othering leading to increased threat perception

My in-depth analysis suggests racialized othering is a first vital process in the shootings of BIPOC citizens. This process consists of two dynamics that increase officer’s threat perception of the later victim: First, an iconic ghetto categorization at the onset of the police operation, and second, cognitive schemata that amplify a racialized threat perception throughout the encounter. The following sections will present my findings. Detailed case vignettes of each case are provided in Appendix C (see online supplementary materials). Readers are encouraged to read them first and then read the following analyses of cases.

Iconic ghetto categorization at the onset of the operation

At the onset of the operation, black citizens, compared to white citizens analyzed, were heavily perceived through their race and perceived as highly dangerous. The Tamir Rice shooting illustrates this dynamic (see detailed case vignette in Appendix C1). On November 22, 2014, 12-year-old Tamir was playing with a toy gun on a Cleveland playground in the middle of the day when a citizen called 911 (Dewan and Oppel Citation2015):

“I’m sitting at the park at West Blvd, by the West Blvd rapid transit station … and there’s a guy in here with a pistol, you know, it’s probably fake. But he’s, like, pointing it at everybody. [Dispatcher seems to repeat simultaneously “It’s probably fake”]. But you know what, he scares the shit out of me.”

“What does he look like?”

“He has a camouflaged head on … ”

[interrupts] “Is he black or white?”

“ … and a grey … grey coat … with black sleeves and grey pants … ”

“Is he black or white?”

[more quietly] “He’s black … Probably a juvenile, you know.”

“Okay, we’re done talking. Thank you.”

Further, although the caller describes the situation as likely harmless, he indicates, “but you know what, he scares the shit out of me.” The caller later told investigators he thought Tamir was “acting gangster” by pulling the airsoft pellet gun out of his waistband (McDonald Citation2018). The caller’s description of Tamir as “acting” this way and his calmness during the call suggests he did not actually feel threatened, but wanted police to stop the perceived “gangster” performance (“but you know what … ”). Studies suggest such actions as part of the interactive ways predominantly white people in the United States—consciously or unconsciously—still enforce the black body at the symbolic bottom of social order (DuBois Citation1903 (1990); Anderson Citation2012a). The caller, in associating Tamir with the ghetto and opposing his “acting gangster,” called 911 on the 12-year-old at a playground. Research suggests it is likely he would have responded differently had he seen a white child on a playground with what he believed to be a toy gun (Goff et al. Citation2014; Eberhardt Citation2020).

At 3:26 pm, Dispatcher Hollinger passes information to a second dispatcher, Mandl. Hollinger mentions the suspect is black, but she neither mentions the caller’s account that he is “probably a juvenile” nor that the gun is “probably fake.” While dropping all other information potentially relevant to the assessment of the situation, race is again the master status. At 3:29, Dispatcher Mandl then places the call as a “Code 1,” the department’s highest level of urgency (on the crucial role of dispatchers in shaping police work, see also Simpson Citation2021). In a country where more than 3.2 million BB/pellet guns are sold annually (Nguyen et al. Citation2002), Tamir is still quickly associated with being dangerous and an imminent threat —although by the citizen’s own account, Tamir is likely a child with a toy gun in the middle of the day on a playground (see also Goff et al. Citation2014, who show black boys are often perceived as less “childlike”).

The same pattern of perceived dangerousness from the onset is visible in the cases of Willie McCoy and Philando Castile (see detailed case vignettes in Appendix C2 and C3), although the cases take place in different circumstances: Willie’s interaction also followed a 911 call, while Philando’s interaction followed a traffic stop by a patrol car. In Philando’s case, Officer Yanez saw Philando driving by and radioed another officer that the occupants of the car “looked like people that were involved in a robbery.” He continued: “The driver looks more like one of our suspects, just because of the wide-set nose. I couldn’t get a good look at the passenger” (McCarthy Citation2016). Yanez disregarded other information he obtained prior to stopping Philando, such as the car not being stolen and there being no warrants out for Philando’s arrest, to be less important than Philando’s “wide-set nose”—again indicating perceptions of race as the master status in assuming Philando might be the suspect. Writing about the dynamics of symbolic racism, Anderson (Citation2012a, 253) states that a black individual interacting in white spaces in the US is frequently “shown that he or she is, before anything else, a racially circumscribed black person after all. No matter what he or she achieved, or how decent and law-abiding she is, there is no protection, no sanctuary, no escaping from this fact.”

To describe this dynamic, Anderson (Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2015, Citation2022) coined the concept of the “iconic ghetto”: The image of the ghetto as the place “where the black people live” has achieved iconic status in the US and serves as a powerful source of stereotype, prejudice, and discrimination. People of color, black men in particular, are assumed to be from the ghetto, an impoverished, crime-prone area. At the onset of interactions with others, they thus have to prove their innocence to a distant, unsympathetic audience that initially sees them as “gangster” and dangerous.

The three cases with black citizens reflect this dynamic at the onset of the encounter and stand in stark contrast to the two cases with white citizens. First, in the shooting of Daniel Shaver (see detailed case vignette in Appendix C4), document data and the body-worn camera footage show no indication that his race was discussed or singled out prior to officers’ arrival, or that he was associated with being highly dangerous, “gangster,” or from the “ghetto.” On the contrary, in Shaver’s case, police were called by a citizen (similar to the Tamir Rice case) after someone saw Shaver point his gun through a hotel window—he was showing his pest control gun to an acquaintance, and they were standing near the window. The employee calling the police does not seem to mention race in the call. He provides police with the name of the person staying in the room (Shaver) and his license plate. Thus, upon checking his name and plate number, police likely knew Shaver was white, but data does not indicate that his race was mentioned (see also studies highlighting police and the white US majority do not see whiteness as a race, DuBois Citation1903 (1990); Bonilla-Silva Citation2013; Welsh, Chanin, and Henry Citation2021).

The same is true for the Katherine Turner (no shooting) case: Similar to Philando’s case, this was a traffic stop. The dash cam footage shows a female officer asking Katherine to stop on the highway after she was suspected of casing a nearby bank (see detailed case description in Appendix C5). After almost backing into the patrol car, Katherine takes off. The officer calmly follows her while talking to dispatch. Sentences like “she is not stopping, but she is yelling out the window” are repeated verbatim by the dispatcher. This dynamic starkly contrasts the police transmissions involving BIPOC citizens, where information was severely reduced to the victim’s race. Katherine is repeatedly gendered in communication as “she.” Through interacting with Katherine and checking her license plate, officers and dispatchers know Katherine is white, yet data suggests her race is never mentioned. The entire pursuit and communication over radio are fairly calm. Officers do not appear threatened, although Katherine, in contrast to all the BIPOC citizens, is non-compliant and tries to flee.

Based on this empirical pattern and building on theories of racialized biases (e.g. Anderson Citation2012b, Citation2015), I formulate the proposition (P1) The “iconic ghetto” stereotype can increase officers’ threat perception of black male citizens at the onset of operations.

Racialized cognitive schemata during the encounter

My comparative analysis suggests racialized threat perceptions are not just present at the onset of the police operation—they prevail throughout: Culturally available cognitive schemata work as a second threat-amplifying dynamic in the process of racialized othering. During the encounter, cognitive schemata are activated to process new information and lead to a doubling down of racialized threat perceptions. Cognitive schemata are both “representations of knowledge as well as information processing mechanisms” (DiMaggio Citation1997, 269). They are part of a cultural toolkit (Swidler Citation1986) actors use to make sense of the world and the situations they encounter.

An empirical pattern emerges in all three instances of black citizens being shot: Officers received clues that their racialized threat perception—their interpretation of the situation, the other person, and their own role—were incorrect. However, in all three, they doubled down on their interpretation of the victim as dangerous by taking these clues as a further sign of dangerousness. The iconic ghetto perception at the onset and this doubling down on it during the encounter thereby amplify each other in a process of racialized othering.

The Tamir Rice shooting can illustrate this finding. Officers were called under a Code 1, the highest level of urgency. To them, Tamir is armed and dangerous. The officers therefore drive as close to him as possible, assuming he will run. Tamir is unarmed and spending his afternoon on a playground. He does not run upon seeing the police car speeding up to him, but approaches it. Given his previous body posture and gestures of boredom, he might simply be curious to see what is happening. The fact he does not run may now indicate to officers that their interpretation of the situation was incorrect: It could indicate Tamir is not a threatening, armed person, that their role is not to chase him, and the situation is not one of a dangerous police operation. Yet the officers double down on their interpretation of him as being dangerous: When they realize Tamir is not running away, they slam on the brakes (Associated Press Citation2014). Officer Loehmann—staying with the existing cognitive schema—assumes Tamir’s reason for not running is that he is even more dangerous than previously assumed and intends to harm the officers while they are stuck in their car: “We were easy targets. Plus, I was stuck in the doorway, and my partner was still seated in the driver’s seat, so we were basically sitting ducks. […] The threat just became incredible” (Ali Citation2017). He quickly exits the car and shoots Tamir in the stomach. While Loehmann and other officers’ ex post statements serve as legal justifications for what happened, Loehmann’s body posture, tone of voice, and actions right after the shooting also indicate fear. After shooting, Loehmann runs behind the car to take cover, seemingly still assuming his life is in danger. Tamir slumps down and dies.

Findings suggest that officers’ interpretations throughout the encounters strongly diverge from those of the victim or bystanders because meaning is centrally shaped by perceived biological and phenotypical differences. This finding is in line with research that describes bias as a distorting lens affecting all types of decision making (Eberhardt Citation2020).

As the Tamir Rice case illustrates, officers do not diverge from this interpretation throughout the encounter, but double down on it. This doubling down is in line with research on cognitive schemata: DiMaggio (Citation1997) shows that while people shift culturally available interpretative schemata when they perceive that these fail, they are generally more likely to perceive information that is germane to existing schemata and, thus, stick with them. I therefore argue the iconic ghetto can operate as a cognitive schema that influences officers’ perception and interaction with BIPOC citizens by determining what information is perceived as salient or superfluous during the encounter. We see a similar dynamic in all three cases of BIPOC victims across stops (911 calls or traffic stops) as well as officer numbers (between two and seven).Footnote3 Officers do not perceive their schema as failing, since they filter new interactional information into the existing schema: They double down on interpreting the victim as dangerous, which results in visible tension.

By sticking with existing schema and filtering new information accordingly, officers threat perception is further amplified, as Tamir’s case illustrates. Research has highlighted that such threat perception leads to increased heart rates, adrenaline surges, and tunnel vision (Artwohl Citation2002; Collins Citation2008), making officers less likely to assess the situation realistically (see also Sierra-Arévalo Citation2021).

This pattern contrasts with the two cases involving white citizens. First, while the three black victims were shot within less than a minute of interacting with the officers, Daniel Shaver interacted with officers over the course of more than four minutes, and Katherine Turner interacted with officers for 11 minutes before leaving the scene. Studying 91 use of force incidents captured on body-worn cameras in Newark, NJ, Piza and Sytsma (Citation2022a; see also Piza et al. Citation2022) find use of force typically occurs after extended interactions between officers and citizens —just under 11 minutes, with a median length of 6.58 minutes. It is thus striking how quickly, in comparison, the three black citizens were shot.

Second, there is no indication that officers tapped into a specific frame othering the white citizens and that they then interpreted new information accordingly. For instance, although Katherine vehemently resists arrest and repeatedly kicks toward officers, officers repeatedly try to explain the situation to her. When she yells “lawyer,” some of the officers laugh at her, indicating that they are not afraid and do not take her seriously. When they finally restrain her, after struggling for several minutes, officers look annoyed and exhausted. Yet nothing indicates Katherine was seen as a threat throughout the encounter. This reaction is vastly different in the cases with BIPOC citizens, who were all compliant (compare Katherine’s actual exhibit of strength to the officers’ assumed strength of George Floyd; Hill et al. Citation2020). The stark contrast and reaction to Katherine as being funny, or exhausting, suggest both racialized as well as gendered interpretations of her behavior and threat level. This finding is in line with research suggesting officers are taught to identify their enemy in racialized as well as gendered ways (Simon Citation2021; Willits and Makin Citation2018).

Based on these case comparisons and the vastly different empirical pattern between police interactions with BIPOC citizens and white citizens, I argue symbolic racism as a historically framed, culturally shaped cognitive schema (DiMaggio Citation1997) can shape officers’ interpretations of encounters with black citizens and amplify racialized threat perceptions. This leads me to proposition (P2) Frame filters can create an amplification of the racialized threat perception of black male citizens during police encounters.

Obscured personhood leading to lowered inhibition

Given the process of racialized othering and increased threat perception, why does every police encounter of a potentially biased officer not end in use of force? Studying the situational dynamics right before officer-involved shootings, my in-depth comparative analysis shows a distinct situational pattern prior to all analyzed shootings: All victims were shot when they were not face-to-face and when in a situationally weak position. I argue this pattern occurs due to a process of obscured personhood that works on the situational level, lowering officers’ inhibition to violence in the seconds before shots are fired, in cases of white and black victims.

For instance, in the Tamir Rice shooting, CCTV footage shows Tamir approaching the car in a curious manner, stopping briefly when the car drives onto the lawn before continuing to walk toward it. When the car halts next to him, he starts looking down at his toy gun. The reason for this glance is unclear; he might be starting to realize police are reacting to it. CCTV footage shows his head going down and his hand going in the direction of his waistband. Immediately after, Officer Loehmann fires two shots at him (see also Appendix C1). Hence, Tamir is not face-to-face with the officers when he is shot.

This pattern is visible across cases: Philando was shot while looking for his driver’s license, as requested by Officer Yanez. Dash cam footage shows Yanez standing on the left side of the car, next to Philando in the driver’s seat. According to his girlfriend and Yanez, Philando—who is not visible, but audible in the recording—was reaching for his pocket (where his wallet was, but where Yanez assumed he had a gun). Thus, Philando looked to his right side and down, while the officer stood to his left and above, meaning Philando was not face-to-face when he was shot (Collins Citation2008, 112–114, describes a similar pattern in the shooting of Amadou Diallo in 1999).

I argue this pattern can be interpreted in light of the micro-sociology of violent confrontation (Collins Citation2008), which posits that not being face-to-face reduces confrontational tension and fear (ct/f). Ct/f would otherwise act as a physiological and psychological barrier to violence not only because actors fear getting hurt, but also due to fundamental difficulties in confrontational face-to-face interactions (Collins Citation2008, 90). Collins (Citation1993, Citation2005) suggests people are used to peaceful interaction rituals, in which they fall into shared rhythms. In violence-threatening situations, tension rises from going against these rituals and rhythms. As eye contact is vital to human intersubjectivity, being face-to-face with another human usually inhibits violence, even if people are motivated. But Collins (Citation2008, Citation2009) claims people get around ct/f by attacking weak victims whose face and thus intersubjectivity (in essence, their humanness) is not visible.

Willie McCoy is face-to face with the officers for most of the police check on him, prior to shots being fired—except for the very last moment. When Willie, asleep in his car when police are called, seems to wake up, several body camera angles show his head moving forward and down and his shoulders moving forward to sit up from the reclined driver seat. It is in this moment—when Willie is, for the first time, not face-to-face anymore and in a situationally weak position while waking up—that officers start shooting. The agitated, simultaneous yelling of several officers (“show me your hands!”) may have further triggered officers to shoot. In addition, the shooting erupts just as the fifth and sixth officer arrive on the scene, with officers outnumbering Willie six to one. The micro-sociology of violent confrontations highlights the chance of violence increases as more officers are present, and the most drastic and serious violence occurs at a ratio of “three to six persons attacking an isolated individual” (Collins Citation2009, 11).

Interestingly, even the fatal shooting of the white victim shows the citizen is shot when he is not face-to-face. After stepping into the narrow hallway, the six officers (featuring the same ratio as in the shooting of Philando) give the intoxicated and scared Daniel conflicting orders, with which he tries to comply as best as he can. When Daniel reaches toward his lower back for about two seconds during the encounter, this movement would most likely lead officers to assume he might draw a weapon. Yet he is looking right at the officers in this moment, and they do not shoot. Shortly after, when Daniel is crawling, looking at the ground, his head down, whining and sobbing, he reaches for his waist to pull up his sliding shorts. This is when one of the officers shoots him. In this moment six officers, several pointing AR-15 semiautomatic weapons at him, outnumber Daniel, and are standing above him (Robinson Citation2017). Daniel is sobbing and crawling on the floor, showing a defeated body posture. All these are indicators of a situationally weak victim (Collins Citation2008). Sgt. Langley, who consistently yells orders at Daniel, is frequently heard taking longer pauses within sentences while doing so. Micro-sociologists argue these pauses are another indicator of dominance over a situationally weak victim: The conversation continues when Langley wants it to (see also Klusemann Citation2009).

Daniel’s case also shows additional situational elements that increase the likelihood of a shooting. Daniel’s is being given numerous orders with which he does not comply, because they are difficult to understand or directly contradict previous orders he is given. He is drunk and is shouted at repeatedly that he will be killed if he does not comply (see Appendix C5). Studying video footage of larger samples of police use of force, Piza and Sytsma (Citation2022a) found suspect behavior consistent with being under the influence of alcohol, as well as officers giving shout commands and interacting in a negative way verbally, all heighten the risk of escalation. Data suggests these situational elements favored the shooting of Daniel, despite OIS of white citizens being overall less common. All of these situational factors were absent in the shooting of black citizens. In these cases, biases increased the perceived threat level.

In short, all victims—black and white—were shot when not face-to-face with officers. In the non-shooting case, officers were constantly face-to-face with the citizen, and gendered interpretations seem to have further shaped their perceived (absence of a) threat. Based on these patterns, and in line with the micro-sociology of violent confrontations (Collins Citation2008), I formulate proposition (P3) Not being face-to-face with the victim lowers the inhibition to violence across police encounters.

Discussion: driving dynamics in officer-involved shootings

My in-depth analysis of real-life police-citizen encounters that ended in shootings identified empirical patters that lead me to formulate three propositions:

The “iconic ghetto” stereotype can increase the officers’ threat perception of black male citizens at the onset of operations.

Frame filters can create an amplification of the racialized threat perception of black male citizens during police encounters.

Not being face-to-face with the victim lowers the inhibition to violence across police encounters.

Evidently, not being face-to-face with someone does not automatically lead to violence, and the same is true for racialized stereotypes. But my article suggests the two processes amplify each other: Racialized stereotypes shape encounters by amplifying threats and situational dynamics minimize human intersubjectivity. Both processes can thereby work to dehumanize the victim. Research on dehumanization has shown that out-group members, such as created in here-discussed OIS through racialized othering and an iconic ghetto categorization (Anderson Citation2012b, Citation2015), are usually perceived less human-like than in-group members (see, among others, Haslam Citation2006; Haslam and Loughnan Citation2014). In the process of racialized othering, working on the cultural level, the “other” is thus perceived as one step removed from the actor and the human in-group. In the process of obscured personhood, working on the situational level, the other’s personhood is no longer visible in the absence of face-to-face interactions. Human intersubjectivity is thereby diminished and the other is perceived as even further removed than in the first process. The three propositions can explain both why BIPOC citizens are subject to officer use of force more frequently (the iconic ghetto stereotype and resulting danger perception is a risk factor for OIS of BIPOC citizens) and why nevertheless most encounters of officers with BIPOC citizens do not end in force (specific situational dynamics are crucial for violence to break out).

Findings indicate cultural and situational explanations, often seen to be at odds with each other, can be merged to explain OIS and to complete each other’s theoretical blind spots. It is not just context factors or just situational dynamics, as current literature on violence debates, but context and culture shapes action. However, the key dynamic, and the way in which culture and context matter, happens on the micro-level (see also Collins Citation1981; Nassauer Citation2022a). My findings show how situation and context are connected in OIS: Racialized biases shape interactional interpretations, while situational dynamics, like not being face-to-face, are vital in determining the use of force.

Conclusion

Officer-involved shootings of BIPOC citizens repeatedly occupy the public, media, and research. This article examined their driving dynamics by studying real-life OIS in depth. The article illustrates how novel types of data, analyzing video data of the events alongside document data, allow an in-depth look into the black box of how officer-citizen encounters unfold. Findings suggest two intertwined processes of dehumanization contribute to the shootings of black citizens—one operating on the cultural level, and one on the situational level.

At the same time, this study faces a number of limitations. First, the stark contrast in police interactions with the white female citizen calls for more research on the role of gender in police encounters. Perceived gender could influence OIS in two ways. Generally, dehumanization processes could be more pronounced in light of discrimination and violence against women (see Bevens and Loughnan Citation2019). However, in the policing context, the analysis of the Katherine Turner case suggests gender stereotypes regarding physical strength and dangerousness may diminish officers’ threat perceptions towards female citizens and may limit the risk of OIS. Thus, gender as a factor in dehumanization processes, and police violence against black women in particular, are aspects that deserve further attention.

Second, while I did not select cases based on citizens’ resistance, none of the black citizens resisted. Further research needs to examine if patterns hold if citizens resist arrest. However, studies show the use of force is much less likely if citizens are compliant (Nix et al. Citation2017, but see Piza and Sytsma Citation2022b). Given the three compliant black citizens were still considered threatening, it is likely they would have been seen as an even greater threat should they have actually resisted.

Third, to contribute to the theoretical literature in the field, future studies could further explore the relationship between dehumanization on the cultural and situational level and compare potentially intertwined processes of dehumanization in other violent outcomes.

Fourth, we need more qualitative, quantitative, and computational studies that examine the interplay of interactional factors during police operations. It can be especially fruitful to compare driving dynamics in real-life cases in which police do and do not employ force, and to examine whether findings differ across police departments that employ different types of trainings. In the US, studies can profit from the ever-increasing number of police-citizen encounters filmed—for instance, as of 2020, the LAPD retains almost ten million BWC videos—as well as novel developments in automated coding and computer vision (Nassauer and Legewie Citation2022). But we also need more research beyond the United States to understand OIS in other countries. To do so, more visual data on police encounters need to be captured and made publicly available. A challenge for all video-based studies on OIS is that the data need to show optimal capture, which many BWC recordings do not (McCluskey and Uchida Citation2023). A further challenge is to gain detailed information on officer interpretation during the event, which can be difficult to scrutinize with either video or document data (Nassauer Citation2022b; McCluskey et al. Citation2019).

Lastly, to further the literature on the prevention of police use of lethal force, it can be fruitful to analyze if OIS can be reduced by expanding officer training on the here-discussed processes of dehumanization. Studies could examine whether use of force can be reduced if training emphasizes that racialized biases can work as risk factors which heighten situational threat perceptions, as well as if training emphasizes possible implications of not being face-to-face with citizens during a tense encounter. Understanding how racialized biases shape all types of interaction dynamics and how we can reduce OIS will be a crucial task for years to come.

Declarations

Funding: Fritz Thyssen Foundation (Travel Grant for research stay at Yale University)

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: Not applicable.

Availability of data and material: All data and material are available online.

Code availability: Not applicable.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (173.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (465.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (130.1 KB)Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I would like to thank Elijah Anderson for hosting me during my one-year research stay at Yale University, during which I conducted this research, for our many fascinating exchanges about sociological research, the sociology of race and racism, and for his feedback on this project and article. I would like to thank the Fritz Thyssen Foundation for funding my research stay at Yale. I thank the anonymous reviewers for their truly constructive comments. Further, I would like to thank (in alphabetical order) Randall Collins, Nicolas Legewie, Demar Lewis, Melanie Lorek, Julia Rodriguez, and Kalfani Turè for their helpful feedback. I also thank the participants of Elijah Anderson’s “Workshop in Urban Ethnography” at Yale University and the participants of the Panel “Racism and Resistance” at the 2020 Eastern Sociological Society Annual Meeting in Philadelphia for their comments. This article was partially supported by Open Access funds of the University of Erfurt.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I use the term “citizen” here, as it is commonly used in OIS literature. While not all people interacting with police may hold citizenship, alternative terms either also implicitly refer to immigration status (“resident”) or rely strongly on the police perspective (“suspect”, “civilian”).

2 Name changed throughout this article for privacy reasons (see Appendix B).

3 Data suggests all involved officers but one (the officer who shot Philando) were Caucasian. All officers but one were male-presenting. The female officer made the call on the Turner case, but was subsequently much less involved in the arrest than her male colleagues. Thus, more research needs to assess whether cognitive schema also apply across officer race, as well as officer and victim gender.

4 Officers in three of the four shootings faced prior disciplinary issues (see Associated Press Citation2017; Dupuy Citation2017; Wu Citation2019). Data did not indicate previous openly racist comments or behaviors by officers involved in the here-discussed cases.

References

- AFP / Reuters. 2015. “Timeline: Recent US Police Shootings of Black Suspects.” ABC News, 9 April. Accessed 9 January 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-04-09/timeline-us-police-shootings-unarmed-black-suspects/6379472.

- Alexander, M. 2012. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

- Ali, S. S. 2017. “Tamir Rice Shooting: Newly released video shows cop’s shifting account.” NBC News, 26 April. Accessed 5 March 2023 https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/newly-released-interview-footage-reveal-shifting-stories-officers-who-shot-n751401.

- Anderson, E. 2012a. The Cosmopolitan Canopy: Race and Civility in Everyday Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Anderson, E. 2012b. “The Iconic Ghetto.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 642 (1): 8–24. doi:10.1177/0002716212446299.

- Anderson, E. 2015. “The White Space.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1 (1): 10–21. doi:10.1177/2332649214561306.

- Anderson, E. 2022. Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Artwohl, A. 2002. “Perceptual and Memory Distortion During Officer-Involved Shootings.” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 71 (10): 18–24. doi:10.1037/e318682004-004.

- Associated Press. 2014. “Cleveland cop who killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice not told boy’s age, that gun might be fake: union.” Daily News, 13 December. Accessed 5 December 2022. Available at: https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/12-year-old-tamir-rice-shot-cleveland-autopsy-article-1.2043229.

- Associated Press. 2017. “Disciplinary charges against 2 officers in Tamir Rice case.” AP News, 13 January. Seattle Times. Accessed 7 March 2023. https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/city-disciplinary-charges-brought-involving-tamir-rice/.

- Bernard, H. R., P. Killworth, D. Kronenfeld, and L. Sailer 1984. “The Problem of Informant Accuracy: The Validity of Retrospective Data.” Annual Review of Anthropology 13 (1): 495–517. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.13.100184.002431.

- Bevens, C. L., and S. Loughnan. 2019. “Insights into Men’s Sexual Aggression Toward Women: Dehumanization and Objectification.” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 81: 713–730. doi:10.1007/s11199-019-01024-0.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2013. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. Washington, D.C.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Bowman, B., et al. 2015. “The Second Wave of Violence Scholarship: South African Synergies with a Global Research Agenda.” Social Science & Medicine 146: 243–248. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.014.

- Caldeira, T. P. R. 2002. “The Paradox of Police Violence in Democratic Brazil.” Ethnography 3 (3): 235–263. doi:10.1177/146613802401092742.

- Carlson, J. 2020. “Police Warriors and Police Guardians: Race, Masculinity, and the Construction of Gun Violence.” Social Problems 67 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1093/socpro/spz020.

- Collins, R. 1981. “On the Microfoundations of Macrosociology.” American Journal of Sociology 86 (5): 984–1014. doi:10.1086/227351.

- Collins, R. 1993. “Emotional Energy as the Common Denominator of Rational Action.” Rationality and Society 5 (2): 203–230. doi:10.1177/1043463193005002005.

- Collins, R. 2005. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Collins, R. 2008. Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Collins, R. 2009. “The Micro-Sociology of Violence.” The British Journal of Sociology 60 (3): 566–576. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01256.x.

- Correll, J., et al. 2007. “Across the Thin Blue Line: Police Officers and Racial Bias in the Decision to Shoot.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92 (6): 1006–1023. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1006.

- Dewan, S., and R. A. Oppel, Jr. 2015. “In Tamir Rice Case, Many Errors by Cleveland Police, Then a Fatal One - The New York Times.” The New York Times, 22 January. Accessed 5 March 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/23/us/in-tamir-rice-shooting-in-cleveland-many-errors-by-police-then-a-fatal-one.html.

- DiMaggio, P. 1997. “Culture and Cognition.” Annual Review of Sociology 23 (1): 263–287. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.263.

- DuBois, W. E. B. 1903 (1990). The Souls of Black Folk. New York City: Vintage Books.

- Dupuy, B. 2017. “Cop who killed Daniel Shaver had a history of excessive force, video shows.” Newsweek, 13 December. Accessed 7 March 2023. https://www.newsweek.com/cop-who-killed-daniel-shaver-had-history-excessive-force-video-shows-746683.

- Eberhardt, J. L. 2020. Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do. New York City: Penguin Books.

- Goff, P. A., et al. 2014. “The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106 (4): 526–545. doi:10.1037/a0035663.

- Goff, P. A. 2016. “Identity Traps: How to Think About Race & Policing.” Behavioral Science & Policy 2 (2): 10–22. doi:10.1353/bsp.2016.0012.

- Gravett, W. H. 2017. “The Myth of Objectivity: Implicit Racial Bias and the Law.” Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PELJ) 20 (1): 1–25. doi:10.17159/1727-3781/2017/v20n0a1312.

- Haslam, N. 2006. “Dehumanization: An Integrative Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10 (3): 252–264. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4.

- Haslam, N., and S. Loughnan. 2014. “Dehumanization and Infrahumanization.” Annual Review of Psychology 65 (1): 399–423. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045.

- Hill, E., et al. 2020. “How George Floyd was Killed in Police Custody.” The New York Times, 1 June. Accessed 18 August 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/george-floyd-investigation.html.

- Hughes, E. C. 1945. “Dilemmas and Contradictions of Status.” American Journal of Sociology 50 (5): 353–359. doi:10.1086/219652.

- Jackson-Jacobs, C. 2013. “Constructing Physical Fights: An Interactionist Analysis of Violence among Affluent, Suburban Youth.” Qualitative Sociology 36 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1007/s11133-012-9244-2.

- Klinger, D. A., R. Rosenfeld, D. Isom, and M. Deckard. 2016. “Race, Crime, and the Micro-Ecology of Deadly Force.” Criminology & Public Policy 15 (1): 193–222. doi:10.1111/1745-9133.12174.

- Klinger, D. A., and R. K. Brunson. 2009. “Police Officers’ Perceptual Distortions During Lethal Force Situations: Informing the Reasonableness Standard.” Criminology & Public Policy 8 (1): 117–140. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2009.00537.x.

- Klusemann, S. 2009. “Atrocities and Confrontational Tension.” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 3 (42): 1–10. doi:10.3389/neuro.08.042.2009.

- Koerner, S., and M. S. Staller. 2022. “’The Situation is Quite Different.’ Perceptions of Violent Conflicts and Training Among German Police Officers.” Frontiers in Education 6: 1–17. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.777040.

- Lee, J. C., and H. Park. 2017. “15 Black Lives Ended in Confrontations with Police. 3 Officers Convicted.” The New York Times, 17 May. Accessed 24 March 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/05/17/us/black-deaths-police.html.

- Legewie, N., and A. Nassauer. 2018. “YouTube, Google, Facebook: 21st Century Online Video Research and Research Ethics.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 19 (3): 1–21. doi:10.17169/fqs-19.3.3130.

- Levy, J. S. 2008. “Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/07388940701860318.

- Makin, D. A., et al. 2019. “Contextual Determinants of Observed Negative Emotional States in Police–Community Interactions.” Criminal Justice and Behavior 46 (2): 301–318. doi:10.1177/0093854818796059.

- McCarthy, C. 2016. “Philando Castile: police officer charged with manslaughter over shooting death.” The Guardian, 16 November. Accessed 5 March 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/16/philando-castile-shooting-manslaughter-police-jeronimo-yanez.

- McCluskey, J. D., et al. 2019. “Assessing the Effects of Body-Worn Cameras on Procedural Justice in the Los Angeles Police Department.” Criminology 57 (2): 208–236. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12201.

- Mccluskey, J. D., and C. D. Uchida. 2023. “Video Data Analysis and Police Body-Worn Camera Footage.” Sociological Methods & Research. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/00491241231156968.

- McDonald, E. 2018. “911 caller was frightened Tamir Rice might shoot him.” Cleveland.com, 12 March. Accessed 5 March 2023. https://www.cleveland.com/metro/2015/06/911_caller_was_frightened_tami.html.

- Mekawi, Y., and K. Bresin. 2015. “Is the Evidence from Racial Bias Shooting Task Studies a Smoking gun? Results from a Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 61: 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2015.08.002.

- Nassauer, A. 2022a. “Situation, Context, and Causality – On a Core Debate of Violence Research.” Violence: An International Journal 3 (1): 40–64. doi:10.1177/26330024221085981.

- Nassauer, A. 2022b. “Video Data Analysis as a Tool for Studying Escalation Processes: The Case of Police Use of Force.” Historical Social Research 47 (1): 36–57. doi:10.12759/hsr.47.2022.02.

- Nassauer, A., and N. M. Legewie. 2019. “Analyzing 21st Century Video Data on Situational Dynamics—Issues and Challenges in Video Data Analysis.” Social Sciences 8 (3): 1–21. doi:10.3390/socsci8030100.

- Nassauer, A., and N. Legewie. 2021. “Video Data Analysis: A Methodological Frame for a Novel Research Trend.” Sociological Methods & Research 50 (1): 135–174. doi:10.1177/0049124118769093.

- Nassauer, A., and N. M. Legewie. 2022. Video Data Analysis - How to Use 21st Century Video in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Nguyen, M. H., et al. 2002. “Trends in BB/Pellet gun Injuries in Children and Teenagers in the United States, 1985–99.” Injury Prevention 8 (3): 185–191. doi:10.1136/ip.8.3.185.

- Nix, J., et al. 2017. “A Bird’s Eye View of Civilians Killed by Police in 2015.” Criminology & Public Policy 16 (1): 309–340. doi:10.1111/1745-9133.12269.

- Parker, K. F., et al. 2005. “Racial Threat, Urban Conditions and Police Use of Force: Assessing the Direct and Indirect Linkages Across Multiple Urban Areas.” Justice Research and Policy 7 (1): 53–79. doi:10.3818/JRP.7.1.2005.53.

- Piza, E. L., et al. 2022. “Situational Factors and Police use of Force Across Micro-Time Intervals: A Video Systematic Social Observation and Panel Regression Analysis.” Criminology 61 (1): 74–102. doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12323.

- Piza, Eric L., and Victoria A. Sytsma. 2022a. “Video Data Analysis of Body-Worn Camera Footage: A Practical Methodology in Support of Police Reform.” In Justice and Legitimacy in Policing, edited by Miltonette Olivia Craig, and Kwan-Lamar Blount-Hill, 59–75. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Piza, Eric L., and Victoria A. Sytsma. 2022b. “The Impact of Suspect Resistance, Informational Justice, and Interpersonal Justice on Time Until Police Use of Physical Force: A Survival Analysis.” Crime & Delinquency (online first: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.117700111287221106947).

- Plant, E. A., and B. M. Peruche. 2005. “The Consequences of Race for Police Officers’ Responses to Criminal Suspects.” Psychological Science 16 (3): 180–183. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00800.x.

- Plümecke, T., C. S. Wilopo, and T. Naguib. 2022. “Effects of Racial Profiling: The Subjectivation of Discriminatory Police Practices.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 46 (5): 811–831. doi:10.1080/01419870.2022.2077124.

- Pryor, M., K. Buchanan, and P. A. Goff. 2020. Risky Situations: Sources of Racial Disparity in Police Behavior. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3711296. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- Robinson, J. 2017. “‘You’re Fucked’: The Acquittal of Officer Brailsford and the Crisis of Police Impunity”, American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed 5 December 2019. https://www.aclu.org/blog/criminal-law-reform/reforming-police-practices/youre-fucked-acquittal-officer-brailsford-and.

- Ross, C. T. 2015. “A Multi-Level Bayesian Analysis of Racial Bias in Police Shootings at the County-Level in the United States, 2011–2014.” PLoS ONE 10 (11): 1–34. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141854.

- Salganik, M. J. 2017. Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sherman, L. W. 1980. “Causes of Police Behavior: The Current State of Quantitative Research.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 17 (1): 69–100. doi:10.1177/002242788001700106.

- Siegel, M. 2020. “Racial Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings: An Empirical Analysis Informed by Critical Race Theory.” Boston University Law Review 100 (3): 1069–1092. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwici5XzpOHAhXfEVkFHbgYCOUQFnoECAEQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bu.edu%2Fbulawreview%2Ffiles%2F2020%2F05%2F10-SIEGEL.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3F-L5VXlEGQKmV_SWWIRen

- Sierra-Arévalo, M. 2021. “American Policing and the Danger Imperative.” Law & Society Review 55 (1): 70–103. doi:10.1111/lasr.12526.

- Simon, S. J. 2021. “Training for War: Academy Socialization and Warrior Policing.” Social Problems. Online first: doi:10.1093/socpro/spab057.

- Simpson, R. 2021. “Calling the Police: Dispatchers as Important Interpreters and Manufacturers of Calls for Service Data.” Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 15 (2): 1537–1545. doi:10.1093/police/paaa040.

- Small, M. L. 2009. “’How Many Cases do I Need?’: On Science and the Logic of Case Selection in Field-Based Research.” Ethnography 10 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1177/1466138108099586.

- Stickle, B., et al. 2020. “Porch Pirates: Examining Unattended Package Theft Through Crime Script Analysis.” Criminal Justice Studies 33 (2): 79–95. doi:10.1080/1478601X.2019.1709780.

- Stoughton, S. W., J. J. Noble, and G. P. Alpert. 2020. Evaluating Police Uses of Force. Accessed 9 December 2022. https://nyupress.org/9781479814657/evaluating-police-uses-of-force.

- Strauss, A. C., and J. M. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Second Edition: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Swidler, A. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51 (2): 273–286. doi:10.2307/2095521.

- Sytsma, V. A., V. F. Chillar, and E. L. Piza. 2021. “Scripting Police Escalation of Use of Force through Conjunctive Analysis of Body-Worn Camera Footage: A Systematic Social Observational Pilot Study.” Journal of Criminal Justice 74: 101776. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101776.

- VerBruggen, R. 2022. Fatal Police Shootings and Race: Evidence Review, Future Research. New York: Manhattan Institute. Accessed 9 December 2022. https://www.manhattan-institute.org/verbruggen-fatal-police-shootings.

- Welsh, M., J. Chanin, and S. Henry. 2021. “Complex Colorblindness in Police Processes and Practices.” Social Problems 68 (2): 374–392. doi:10.1093/socpro/spaa008.

- Willits, D. W., and D. A. Makin. 2018. “Show Me What Happened: Analyzing Use of Force Through Analysis of Body-Worn Camera Footage.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 55 (1): 51–77. doi:10.1177/0022427817701257.

- Worrall, J. L., et al. 2018. “Exploring Bias in Police Shooting Decisions with Real Shoot/Don’t Shoot Cases.” Crime & Delinquency 64 (9): 1171–1192. doi:10.1177/0011128718756038.

- Wu, G. 2019. “Vallejo officer in Willie McCoy shooting killed another man in 2018.” San Francisco Chronicle, 23 February. Accessed 05 April 2023. https://www.sfchronicle.com/crime/article/Officer-in-Willie-McCoy-shooting-killed-another-13632671.php.