ABSTRACT

A growing body of empirical research in Latin America reveals a correlation between skin colour and disadvantages in income, health, education, and employment. The impact of skin colour in the political sphere, however, remains severely understudied. Is there any evidence to suggest racialised political underrepresentation in Latin America? To analyse the status of ethno-racial representation in Mexico, this paper uses the Classification Algorithm for Skin Colour (CASCo) to collect skin colour data of the (3,000) members of the last six legislatures of the Mexican Chamber of Deputies. The findings suggest that, while legislatures tend to be relatively diverse, positions of legislative leadership are unproportionally restricted to legislators with light skin colour. This article not only provides much-needed empirical data on the political impact of skin colour in Latin America, but it reveals the sociocultural complexities of the political underrepresentation of racialised groups in Mexico.

Introduction

Research in Mexico has documented racialised preferences and bias in interpersonal relationships and the job market; as well as racial disparities in education, income, and social mobility (Arceo-Gomez and Campos-Vazquez Citation2014; Campos-Vazquez and Medina-Cortina Citation2019; Moreno Figueroa Citation2008, Citation2010; Rejón Piña Citation2022; Telles Citation2014; Trejo and Altamirano Citation2016). The evidence suggests that discrimination by skin tone in Mexico is widespread at both personal and systemic levels. Statistically, light-skinned Mexicans are better-off. However, academic research has mostly overlooked how these racial disparities impact political representation.

The question of political representation is interesting because comparative studies show that ethnic minorities are poorly represented in most democracies (Bird Citation2004, Citation2005; Ruedin Citation2009). In Latin America, the issue remains severely understudied, and the relevant data is generally unavailable (Htun Citation2015, 24). The few existing studies in the region examine primarily the Brazilian case, and reveal that political underrepresentation of racial minorities is pervasive in the Federal Senate, Chamber of Deputies, and state governorships (Bailey Citation2009; Bueno and Dunning Citation2016; Campos and Machado Citation2018; Janusz Citation2019; O. Johnson Citation1998; Mitchell Citation2010). In that context, researchers find a correlation between a generalised racial bias and political underrepresentation (Janusz Citation2018; M. Johnson Citation2017; Machado, Campos, and Recch Citation2019).

The limited data available reveals worrying findings and makes it urgent to conduct more research on political representation in Latin America. While some studies have started to fill this gap in the literature (Campos-Vazquez and Rivas-Herrera Citation2021; Ramirez and Campos Citation2017), more research is imperative. In this article, I examine the ethno-racial composition of the last six legislatures (LX-LXV) of the Mexican Chamber of Deputies using the Classification Algorithm for Skin Colour (CASCo) – a novel method to measure skin colour that surpasses its predecessors in that it objectively produces standardised data that enables cross-national comparisons and longitudinal analyses. The findings not only provide much-needed empirical data, but reveal the sociocultural complexities of the political underrepresentation of racialised groups in Mexico.

To achieve its purposes, the article is structured as follows. In Section “Descriptive political representation”, I review the academic literature on the theory of political representation in order to introduce a working definition for descriptive representation. In Section “Context”, I outline the Mexican historical and institutional context framing this research. I describe the Mexican political system and I explain the myth of mestizaje; particularly, I expose how this racial ideology impacts racial identification. In Section “Methodology”, I unpack the methodology of the study; I defend the approach to use skin colour as a proxy for race, describe the sources and characteristics of the data, and briefly explain the way in which CASCo works. In Section “Findings and discussion”, I present and discuss the findings looking at the composition of the Chamber, paying special attention to regional distribution, partisanship, and leadership. In the conclusion, I point out some areas for further research.

Descriptive political representation

Pitkin’s (Citation1967) seminal work on political representation defined representation as “acting in the interest of the represented, in a manner responsive to them” (Pitkin Citation1967, 209–210). This definition continues to be broadly accepted. Note, however, that this definition makes no reference or appeal to the characteristics of the representative – the person representing others. This differs to recent debates surrounding political representation of people from minority groups (i.e. ethnic/racial/gender).

Originally, the debate on political representation was centred on the representation of opinions and interests (Phillips Citation2001, 22). This focus was not (always) to exclude members of these minority groups, but grounded on the idea that their interests could be represented by anyone, including non-members of those groups. In other words, “representation” referred to a relationship between legislators and constituents on policy matters (Jewell Citation1983, 304), and it was assessed according to how well the legislator reflected the voters’ opinions or preferences (Phillips Citation1998, 2).

However, perhaps the most important of her contributions, Pitkin distinguished between substantive and descriptive representation. She called this traditional understanding of representation “substantive”; and contrasted it with “descriptive representation”, which takes into account – and values – the identity of the representative, not only their political opinions and actions (Pitkin Citation1967, 80–81). When representation is substantive, all that matters is that the representatives advocate for the specific political needs of their constituents; but when representation is descriptive, representatives and constituents share membership to a particular social and demographic group (Pitkin Citation1967, 60–91). The underlying assumption behind this approach to political representation is that the sole presence of people is a public declaration of equal value that contests traditional norms of exclusion.

The necessity of “descriptive representation” is evident, both normatively and empirically. Technically, anyone can represent anyone, but when (the constitution of) legislative bodies resemble histories of exclusion, the discriminatory and paternalistic idea that certain people are less fit to rule – and should be cared for by those “who know best” – is reinforced (Phillips Citation1998, 40). Furthermore, empirical studies demonstrate that, usually, non-members of minority groups are lousy representatives of minorities’ interests. Major political issues (i.e. race and gender) rely on lived experience and seem to necessitate shared experience to guarantee representation. While it is technically true that “anyone can represent anyone”, this would depend on continuous communication and total convergence between agent and principal (in terms of strategies, policies, etc.) that is simply not possible through existing mechanisms of accountability. In other words,

where there has been a long history of subordination, exclusion, or denial, it is particularly inappropriate to look to individuals without such experience as spokespeople for the group in question: not because such individuals can never be knowledgeable or never trusted, but because, failing the direct involvement of those with the relevant experiences, the policy process will be inherently paternalistic and the policy outcome almost certainly skewed. (Phillips Citation2001, 26)

Appropriate political representation is key for democracies, particularly for multicultural societies, where interethnic relations determine political stability (Burlet and Reid Citation1998, 281; Madrid Citation2005). Research suggests, on the one hand, that ethnic minority groups are more likely to challenge the government and exhibit less support for the regime if they are not represented in politics (Hanni and Saalfeld Citation2020, 223). On the other hand, represented minorities are more likely to participate in politics (Moser Citation2008) and more satisfied with democracy altogether (Ruiz-Rufino Citation2013). For these reasons, activists and academics have demanded the inclusion of distinct – historically marginalised – voices (Bird Citation2014).

Certainly, mechanisms of inclusion are far from perfect and sometimes counterproductive; still, placing members of marginalised groups in positions of power seems to communicate a message of inclusiveness, promote recognition, and positively challenge discriminatory stereotypes (Htun Citation2015, 19). Even if there is no guarantee this will happen, members of marginalised groups are more likely to substantively represent their constituents (Grose Citation2011; Lublin Citation1997, 12; Mansbridge Citation2009) and their very presence in the decision-making spaces makes it more probable for other (including members of dominant groups) to acknowledge and address their concerns (Phillips Citation1998, 3, Citation2001, 25–26). If not for anything else, descriptive representation is important to legitimise the political system and to foster political participation (Zappalà Citation2001).

Context

The myth of mestizaje and racial identification

During Mexico’s colonial era, the conquistadors established a caste system that privileged “racial purity” (Russell Citation2010, 50); this system was abolished, institutionally at least, when Mexico gained its independence (Levitin Citation2011). In practice, however, ethno-racial inequalities continued. In response, during the twentieth century, Mexican progressive elites embraced the myth of mestizaje: the idea that Mexican society was united and colour-blind (Knight Citation1990). According to this myth, miscegenation between the Spanish and the Indigenous had produced one single cosmic race: the mestizo, which embodied the best of both peoples (Martınez Casas et al. Citation2014; Vasconcelos Citation1948). This racial uniformity was sought at the expense of the “indigenous” and the “black” (Corona Citation2020), as public policies aimed to produce a homogenous (Spanish-speaking and looking) society (Barragan Citation2020).

Paradoxically, the myth of mestizaje successfully removed the notions of “race”, but not the racist practices behind them. A synergy between racism and mestizaje created a society in which people celebrate their racial mixture at the time they desire phenotypic whiteness (Sue Citation2020). Most deny the existence of racism, but racist logics of discrimination and exclusion persist (Moreno Figueroa Citation2008, 285).

Moreover, because the public discourse denied the existence of these ethno-racial communities, these groups eventually turned “invisible”, without legal and political recognition (Iturralde Nieto Citation2018). As part of this invisibilization process, on censuses, the government asked questions about cultural characteristics (i.e. such as maternal language or forms of dress) instead of directly asking about race (Loveman Citation2014, Chapter 6; Sue, Riosmena, and Telles Citation2021). The form in which these questions were asked focused the attention on indigenous populations and shadowed those of African origins. Consequently, the state not only “obtained” information, but “shaped” the population (Angosto Ferrández and Kradolfer Citation2012).

Censuses are spaces of contested social representations and essential in the fight for group recognition. Therefore, as a political tactic to revalorise their collective identity – and with the support of international organizations – activist organizations across Latin America have demanded to be appropriately included in these counts (Angosto Ferrández and Kradolfer Citation2012, 3; Del Popolo and Schkolnik Citation2012, 310; López Chávez Citation2018; Loveman Citation2014, Chapter 7).

The progress in this regard has been slow, but steady (CEPAL Citation2020). Currently, most Latin American countries ask questions to identify indigenous and Afro-descendant populations to the best international standard: self-identification (Del Popolo et al. Citation2009; Htun Citation2014). In Mexico, censuses have incorporated cultural questions about indigeneity for decades, but self-adscription questions are more recent. In fact, the “Afro-Mexican” identity was not included until the 2020 census (Solís, Güémez Graniel, and Lorenzo Holm Citation2019, 16).

However, the myth of mestizaje continues to hinder the impact of these advancements; some Mexicans do not identify themselves in these new classifications either because they ignore that the categories exists or because they do not want to be associated with them (Del Popolo et al. Citation2009, 63). For instance, many Afro-Mexicans express uneasiness with their black identity because it is stigmatised (Sue Citation2013; Vaughn Citation2013) or many people consider themselves “carriers” of “indigenous culture” rather than members of an indigenous group (Saldívar and Walsh Citation2014, 471). To redress this situation, activists continue to educate communities about their history, their identity, and their rights (Velazquez and Iturralde Nieto Citation2012, 114).

While it is true that the myth of mestizaje affects the way in which racial identity is construed in Mexico, the work of activists is changing the tide. The increased connection with Afro-descendants from other countries, the rephrased questions in surveys/censuses and the raise in people’s awareness of their racial identity, have caused the number of people self-identifying as Afro-Mexicans to grow (Sue, Riosmena, and Telles Citation2021, 28; Vaughn Citation2013; Villarreal and Bailey Citation2020). This trend is likely to continue.

Research shows that group identity is dependent on “linked fate”, on whether a person feels they share common experiences with other people (Mitchell-Walthour Citation2017, Chapter 3). In countries such as Brazil and the US, common histories and experiences of discrimination led to feelings of attachment to racial groups (Mitchell-Walthour Citation2017, 147). Given the pervasiveness of the myth of mestizaje, it would be surprising for most people of colour to believe they were discriminated against as a group, but as research continues to unveil these realities in Mexico, their racial identification might change in response. Mitchell-Walthour’s (Citation2017) research in Brazil demonstrates that factors thwarting people’s racial self-identification are related to shame, racism, and lack of consciousness; at the same time, political consciousness and struggle, along with elements such as skin colour and ancestry, facilitate racial identification. It is probable that research and activism in Mexico will continue to mitigate the impact of the factors hindering racial identification while advancing its enablers.

Furthermore, as flagged earlier, censuses not only adapt to the social world, but they configure it, legitimising and generating social identities (Angosto Ferrández and Kradolfer Citation2012, 27). The fact that the most recent surveys/censuses in Mexico have included questions about ethnic and racial identity will, arguably, increase self-identification with racial and ethnic groups.

Political system

Mexico is a federal republic made up by 32 states. The federal Executive branch is embodied by the President, elected every six years. The Legislative power falls on the “Congress of the Union”, comprised by the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Deputies are elected every three years, while Senators’ term is six years long. The Chamber of Deputies is made up by 500 legislators, of which 300 are elected by Relative Majority and 200 by Proportional Representation. The Senate has 128 legislators (96 Relative Majority and 32 Proportional Representation) (INE Citation2023). According to the Constitution, both legislative bodies have the capacity to create, reform or abolish laws. However, each has exclusive faculties. For instance, the Senate can endorse international treaties, ratify ministers, and authorise the deployment of troops beyond national borders.

Despite their longstanding history, the Mexican Legislative Chambers were largely symbolic in a quasi-dictatorial system dominated by one party (Party of the Institutionalised Revolution – PRI), led by the President of the Republic (Béjar Algazi Citation2006). In his capacity of leader of the party and of the Executive branch, the Mexican President initiated most legislation. With the advent of competitive elections, the institutional arrangement had to adapt to the fact that the President was no longer able to unilaterally govern (Bárcena Juárez Citation2018, 407). Soon after PRI lost the Presidency and the majority in Congress, the legislators assumed the primary role on creating new laws (Béjar Algazi Citation2012). Particularly, it was the Chamber of Deputies which stepped up to fill the void the President had left; from 1985 to 2015, the average of law initiatives presented by each Deputy grew 500 per cent (Bárcena Juárez Citation2017). It is for this reason that the analysis here focuses on political representation in the Chamber of Deputies.

To better assess the state of the political representation of racialised groups in Mexico, I analyse three aspects, other than the mere composition of the Chamber: geographic regions, partisanship, and leadership.

First, it is important to note that the Mexican indigenous and Afro-descendant populations are significantly clustered in regional areas. For instance, most Afro-Mexicans inhabit the Costa Chica region, in the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero (López Chávez Citation2018; Sue Citation2020); while more than half of the population that speaks an indigenous language in Mexico lives in four states: Oaxaca, Chiapas, Yucatan and Guerrero (INEGI Citation2022). These concentrations are useful to evaluate descriptive representation.

Second, political parties in Mexico are traditionally associated with certain ideologies and political stand points. For example, PAN is associated with business owners and higher middle class, whilst PRD and MORENA are associated with the working class. Because research shows that there is a correlation between skin colour and class (Cerón-Anaya Citation2020; Krozer Citation2019), one would expect partisanship to be correlated to skin colour: if dark skin tones are associated with low income and low income is associated with certain political parties, then one would expect the caucus composition of certain parties to reflect this transitional axiom.

Third, positions of leadership within the Chamber are another, perhaps more, relevant aspect of political representation. One significant leadership body within the Chamber of Deputies is the Board of Directors (“Mesa Directiva”). According to the System of Legislative Information (Secretaría de Gobernación Citation2017), the Board of Directors is the expression of the Chamber’s political unity. The Board of Directors is integrated by a president, three vice-presidents and one secretary per political party in the Chamber. This board is responsible for overseeing the sessions of the Chamber, which includes designing the meeting agendas (and therefore, selecting the topics that are discussed and in what order) and making sure legislators behave appropriately (and determining penalties when they do not). Another, perhaps more powerful, leadership entity in the Chamber is the Political Coordination Board, constituted by one leader from each political party in the Chamber. This board controls substantive internal legislative resources, and it oversees the selection of the members and presidents of each legislative committee (Algazi and Juárez Citation2016, 117). The Board is not powerful only insofar it distributes the leadership positions of the committees, but it controls most of the legislation too; this is because at least the most important bills are pre-negotiated among the parties’ caucus leaders in the Board even before they reach committees (Rivera Sánchez Citation2004, 263). Taking this into account, the political relevancy of the Board becomes obvious, and makes it another important focus of analysis for the political representation of racialised groups in Mexico.

In Section “Findings and discussion”, I discuss the findings looking at the composition of the Chamber, paying special attention to regional distribution, partisanship, and leadership.

Methodology

“Racial” political representation

In Section “Context”, I unpacked the complexities of racial identification in Mexico and Latin America, and how these have impacted the availability and accessibility of reliable official data. For decades, most countries in the region did not regularly collect data on racial identification on censuses (O. Johnson Citation2015). This kind of data is even more scarce for political candidates and politicians, so academics have resorted to informal sources, such as media reports or social activists, to classify them (Gonzales Matute Citation2020, 25). While this is starting to change – with countries such as Brazil and Ecuador asking questions about race/colour when candidates declared their intention to run for office – statistical data on race and ethnicity has been historically rare, especially for Afro-descendants (Htun Citation2015, 24).

In Mexico, the electoral authorities have started asking candidates these questions, but the data is not available for the legislatures I study here. To resolve this, I use skin colour as a proxy for race. This approach is hardly new, particularly in Latin America; researchers have used verbal scales, colour palettes, photo elicitation and even spectrophotometers to measure skin colour; and then skin colour as a proxy for race (Rejón Piña and Ma Citation2023). The approach, expectedly, is not without criticism. Objections to both the assumption that skin colour is a good proxy for race and to the characteristics of the tools used to measure skin colour have been raised. Here, I use skin colour as a proxy for race, but I use a new measuring tool. Therefore, I respond to the former critique, while endorsing the latter.

Skin colour is just but one of the factors at play in the phenomenon of race, so it is easy to understand why one might object to using this variable as a proxy for race. While it is true that the aggregate of “race” is made of many factors such as societal values, cultural traits, physical attributes, diet, region of ancestry, institutional power relationships (to mention a few) (Sen and Wasow Citation2016, 506; Wade Citation2012); it is also true that skin colour often elicit a racial ideology (or a “racial schema”) where people are aware of human colour variation (Roth Citation2012, 12; Telles Citation2012). Studies show that skin colour is often the most important predictor of racial identification, even above social status (Banton Citation2012; Telles and Paschel Citation2014). This is especially true in Latin America (Telles, Flores, and Urrea-Giraldo Citation2015) where, unlike other contexts, racial and ethnic labels track not only descent, but physical appearance and socioeconomic status (Htun Citation2015, 165). Some argue that, in Latin America at least, “race” refers mostly to skin colour or physical traits (Mitchell-Walthour Citation2017, Chapter 1; Telles Citation2004, 79). Others use the terms “race” and “colour” interchangeably in the Latin American context (Htun Citation2015, 20–43). In Mexico, particularly, “ethnicity, national identity, belonging, and ‘looks’ are all intertwined” (Saldívar Citation2014, 90). All this gives us reason to consider skin colour a decent proxy for race. If unpersuaded, however, the reader can still examine the findings presented here as interesting insights of the effect of skin colour as a different – and detached – variable from race.

Now, when it comes to the tools traditionally used to measure skin colour in social research, I sympathise with the critics. Recently, Chenglong Ma and I (2023) examined common methods to measure skin colour and argued they are not only expensive and slow, but susceptible to human bias. In response to these shortcomings, we introduced the Classification Algorithm for Skin Colour (CASCo), which I employ here. CASCo is a Python library that automatically and objectively detects the skin colour of the face area of a given portrait and it classifies it into one of the categories in the PERLA colour palette (Telles Citation2014; see Appendixes), the one closest to the colour detected from the portrait. Using the PERLA colour palette makes it easier to communicate the results – given how widespread its use is – but it will also allow further comparative research.

Data

I examine the composition of the past six legislatures (LX-LXV) of the Mexican Chamber of Deputies; that is from 2006 to 2021. This sampling responds to both practical and analytical parameters. On the one hand, before 2006, the Mexican Chamber of Deputies was dominated by the Party of the Institutionalised Revolution and its role was marginal to the presidential figure – who initiated most legislation. On the other hand, perhaps for reasons related to the liberalization of the political system after 2006, the data on previous legislatures is unavailable on the Chamber’s website. Starting with the LX Legislature, the website contains detailed statistics of the legislative processes and the political composition of the Chamber. While there are no official variables or indicators of the racial origin or characteristics of the legislators, the Chamber of Deputies publishes a photo album which contains characteristics of the legislators (i.e. name, party, region, sex) and studio portraits, taken against a white background, in similar light conditions and the same level of contrast (Secretaría General Citation2022). I have used CASCo to process these portraits and created a skin colour variable. In total, the dataset includes 3,000 legislators and – in addition to skin colour – contains information such as sex, party, type of election, and it records whether the legislator held any leadership position (i.e. member/chair of the Political Coordination Board, member/chair of the Board of Directors).

Findings and discussion

Composition of the chamber

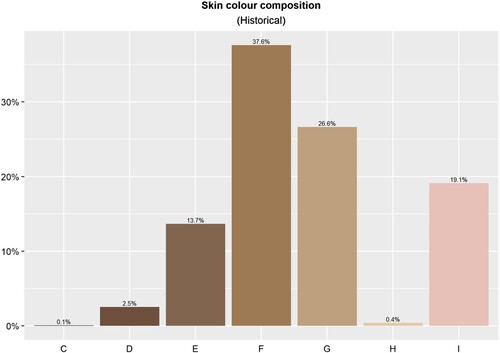

reveals the composition of the past six legislatures of the Mexican Chamber of Deputies. Note that some categories from the PERLA colour palette are missing; none of the 3,000 portraits CASCo processed belong to the two darkest and the two lightest categories. This contrasts with a recent national level survey which found that all the PERLA colours are present in Mexico, including 0.2% in A, 0.5% in B, 4.9% in J and 2.1% in K (INEGI Citation2016). It is, then, fair to assume that there are barriers to entry. Interestingly, categories at both extremes of the spectrum are missing, but brown and light-brown skin tones are present. This suggest that racism has not impacted political representation in Mexico the same way it has affected it in other countries; where Caucasic looks dominate political bodies or where ethnoracial minority groups are simply absent (Malhotra and Raso Citation2007). For sociohistorical reasons, including the myth of mestizaje outlined earlier, Mexican racism is not segregationist. Discrimination takes place, but not always in explicit ways. These findings somehow confirm other – qualitative – studies. For instance, an ethnographic investigation (Tipa Citation2020) of a casting agency in Mexico revealed that the most demanded profile in Mexican advertisement is “Latin American”, a blend of European and Indigenous traits that explicitly excludes characteristics attached to the stereotypical appearances of both groups (i.e. dark skin but also blonde hair).

All this reveals the legacies of the ideology of Mestizaje; the aspiration for “the middle point” between the two racial groups was the aim of the Mexican government for many decades and, at least when it comes to political representation, this aspiration for the “mestizo” appears to be costly for those who do not fit the “ideal mestizo appearance”, at both ends of the spectrum.

Note, however, that categories F and G (i.e. the “light mestizo”) are overrepresented. This aligns with anthropological findings, about the pervasive preference amongst Mexican people for “fairer” looks (Moreno Figueroa Citation2008, Citation2010). Also, the proportion of category I in the Chamber of Deputies is significantly higher than its proportion in Mexican population. Again, this demonstrates the complexities of Mexican racism and suggests that importing frameworks and solutions from other contexts might be inappropriate.

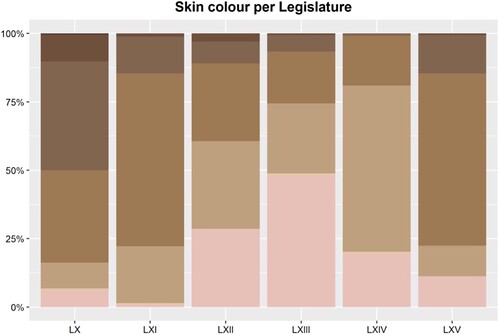

presents the skin colour composition of each of the studied legislatures. No progressive pattern is evident and there are no indications that the state of racial representation in the Chamber of Deputies is changing in a linear trend. For example, Legislatures LX and LXI are darker but followed by very light legislatures (LXII and LXIII); finally, in Legislatures LXIV and LXV the proportion of light colours is smaller again.

There are different possible explanations for this inconsistent development. One, logically, is that skin colour is a random variable with no real explicative power. This, however, is not consistent with other findings. An alternative explanation for this is related to the political system and, more specifically, with the electoral institutional arrangement. On the one hand, studies in Mexico have shown that skin colour is a salient factor, and an advantage for light skinned candidates, in competitive elections (Campos-Vazquez and Rivas-Herrera Citation2021). On the other hand, past research shows a large “drag effect” in Mexican General elections, where constituents tend to cast all their (legislative) votes in line to their vote for a presidential candidate (Carey Citation1994; Nohlen Citation1994; Shugart and Carey Citation1992). The notable popularity of the candidates in the last two general elections could explain the relative insignificance of skin colour in those instances. In 2012, Enrique Peña Nieto obtained almost 40 per cent of the votes and his party (PRI) gained 212 seats in the Chamber. In 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador had an even more sweeping victory, with 53.19 per cent of the votes. His party secured 253 seats in the Chamber. Another possible explanation in this variation is partisanship. That is, preferences for a political party might trump any racial consideration for voters. I discuss this variable later.

Regional distribution

In Section “Context”, I pointed out that the Mexican indigenous and Afro-descendant populations are concentrated in regions: most Afro-Mexicans in the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero; and most Indigenous peoples in the states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Yucatan, and Guerrero. Assuming a descriptive correlation between constituencies and representatives, one would expect that the proportion of deputies with darker skin would be higher in these states.

allows comparisons between each of these states and the national average, per skin colour (a table with all the states is available in the Appendixes). These data shows that, with the exception of Guerrero in tone D, all these states are actually below the national average at the darkest end of the spectrum. Tones E, F and G are slightly higher than the national average. Rather than a higher proportion of legislators with dark skin tones, these states display a preference for tones in the middle, or even whiter tones, such as Yucatan’s proportion of I, which confirms the racial logics documented by Iturriaga (Citation2016).

Table 1. Skin colour and state.

“Whiter” states, with more legislators in I, are Zacatecas (35.2 per cent), Yucatan (28.3 per cent) and Aguascalientes (28.2 per cent). States with more legislators in C are Nuevo León (0.8 per cent) and Jalisco (0.6 per cent).

Partisanship

A complete table that displays the skin colour distribution by political party is available in the Appendixes. filters the findings, showing only the main political parties and the average amongst all parties.

Table 2. Skin colour and political party.

In Section “Context”, I noted one would expect “left-wing” parties to have a larger proportion of legislators in the dark end of the spectrum. This appears to be the case for the PRD but not for Morena. Interestingly, PAN is one of the “whitest” parties, as expected, but also above average in tones C and D, the “darkest”. In general, the overall trend is true for each political party, with concentrations in the tones in the middle. Exploring the relation between party ideology and racial representation escapes the scope of this paper, but this data indicates such research is necessary. The initial findings challenge the hypothesis that associates skin colour and partisanship, but there is no clear correlation either way. Further research is required to explain how (why) Mexicans vote for certain parties and candidates, and whether skin colour trumps other factors.

Leadership

A deeper analysis of descriptive representation in the Chamber of Deputies should pay attention to the leadership bodies within the Chamber.

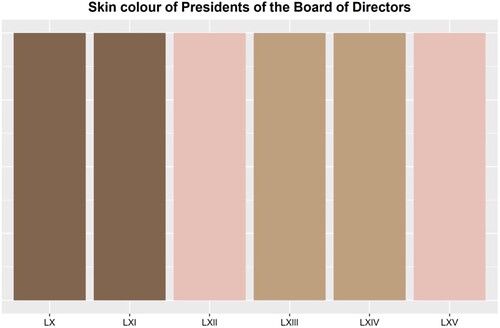

shows the skin colour aggregates for Legislatures LX-LXV and compares it to the composition of the Board of Directors. In other words, it presents whether the proportion of legislators of each colour category in the Board of Directors is larger or smaller than their overall proportion in the studied legislatures. Colours C and D are underrepresented, but that is also true for H, even if in lesser degree. F and G are also underrepresented and, while E is slightly overrepresented, category I (the lightest) is the most overrepresented. In short, the Board of Directors is “whiter” than it should be.

Table 3. Skin colour composition: total vs board of directors.

This reality is made even clearer when the analysis focuses on the skin colour of the Presidents (Chairs) of the Board of Directors ().

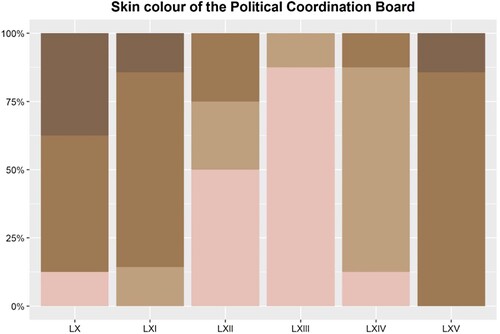

The other leadership body of the Mexican Chamber of Deputies is the Political Coordination Board. As pointed out earlier in the article, this Board selects the members and president of each legislative committee and, in practice, it controls most of the legislation, given that (at least) the most important bills are pre-negotiated among the parties’ caucus leaders in there even before they reach committee. Therefore, the Political Coordination Board is probably the most powerful body in the Chamber; so, analysing descriptive representation within it is key.

Similar to the overall composition of the legislatures, shows no clear patterns regarding racial representation in the Political Coordination Boards.

Figure 4. Skin colour distribution of the members of the Political Coordination Board in Legislatures LX-LXV.

However, reveals interesting insights. Categories C, D and E (the darkest) are underrepresented to a total of 6.2 per cent below exact representation. While category F is slightly overrepresented (1.5 per cent), category G has 5.9 per cent less members than what exact representation would require; strikingly, most of these disparities fuel the 9.2 per cent of overrepresentation of category I, the whitest skin colour.

Table 4. Historical skin colour vs political coordination board (PCB).

These new data confirm existing findings of other – qualitative and quantitative – research. On the one hand, the political underrepresentation of racialised groups in Mexico is not as obvious as it might be in other contexts. These nuances respond more to the sociohistorical characteristics of the country, than to the inexistence of racial discrimination. When it comes to Mexican racism and the political exclusion of racialised groups, the devil is in the details. The question is not necessarily whether people from all skin colours can be legislators in Mexico – arguably, they can – but how much can they do once they get to the Chamber. These findings suggest that positions of legislative leadership continue to be unproportionally restricted to legislators with lighter skin colour. Despite some legal and political victories, then, racialised people in Mexico continue to live be politically relegated (Saldívar Citation2014, 90).

Conclusion

I started this article reviewing the academic literature on political representation to present a definition of descriptive representation. Then, in Section “Context”, I described the historical and institutional context of political representation in Mexico to introduce the analytical and empirical framework of the paper. I described how the myth of mestizaje has shaped the ways in which racial identification is construed in Mexico. I also outlined key characteristics of the Mexican political system, to lay the foundations of the empirical analysis. In Section “Methodology”, I argued that using skin colour as a proxy for race is a sound way to circumvent the lack of official self-identification ethno-racial data. I explained how CASCo works and why it is a good way to measure skin colour. I also described the data used in the study. In Section “Findings and discussion”, I presented the racial composition of the Chamber, and the way skin colour distribution varies across states, parties, and leadership positions. The findings suggest a significant underrepresentation of racialised groups in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies.

To conclude, I want to go back to the complex relationship between descriptive and substantive representation I flagged earlier in the article. While – theoretically – descriptive representation is not necessary for substantive representation, empirical research demonstrates that the political interests of marginalised groups tend to be overlooked by representatives who are not members of these groups. The logical first response to these empirical findings might be to think that the presence of members of minority groups in legislative bodies is an obvious fix to the situation, and to advocate for mechanisms of inclusion, such as quotas or electoral reserves. However, I refrain for making such recommendations here, for at least three reasons.

First, there are many factors that could potentially explain the descriptive underrepresentation I have found in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies. Some studies show that minorities do not necessarily vote for minority candidates (Eelbode et al. Citation2013; James Citation2011; Tipa Citation2020) and that (at least in some settings) the lack of descriptive representation might be partisanship (Juenke and Shah Citation2016) and poorly run campaigns (Thernstrom Citation1982). Given the sociohistorical context and the findings of other research, I think the most logical interpretation of the data is that skin colour negatively impacts the election and performance of legislators, but further research is necessary to test this hypothesis against other potential explanatory variables.

Second, “mandated” descriptive representation (i.e. quotas) is not necessarily going to deliver substantive representation (Forest Citation2001; Grofman Citation1982, 99). In the Latin American context, studies have noted the failure of most electoral institutions to secure accountability between legislators from excluded groups and the constituencies they supposedly represent (Gonzales Matute Citation2020; Htun Citation2015, 10) and that, sometimes, “descriptive” representatives have no real intention of representing and advocating for their groups’ interests (Htun Citation2015, 93–120).

Third, even if the underrepresentation I have found here is indeed better explained by racial discrimination, “forcing” descriptive representation through public policy might not be the best strategy to redress it. For instance, some studies suggest that pro-minority policies incur a greater electoral penalty than ethnicity itself (Martin and Blinder Citation2021) and that redistricting strategies that intend to advance descriptive representation might come at the expense of substantive representation (Lublin Citation1997, 1–17, 72). If this is the case, this kind of policy could harm the groups it aims to support.

While these arguments give us reason to be cautious about mandating descriptive representation through inclusion mechanisms, I do not deny these could have a positive impact. Afterall, research has also shown that legislators from ethnic background are more responsive to ethnic constituents (Zappalà Citation1998) and more likely to combat the structural inequalities (Htun Citation2014, 129, Citation2015, p. 2). These legislators are also more productive during their terms in office in general (Mitchell Citation2010, 38) and, particularly, proposing legislation that reflects the preferences of marginalised groups (Broockman Citation2013; Janusz Citation2019; Mügge, van der Pas, and van de Wardt Citation2019).

In the presence of “conflicting” empirical evidence, it is wise to recognise that quotas can be easily manipulated by political parties for electoral and political purposes (Htun and Ossa Citation2015, 72; Ruedin Citation2009, 347; Weeks Citation2018) and, – while other mechanisms (i.e. legislative reservations) might be better suited for these purposes (Htun Citation2004) – think about the underlying conditions causing the need for mechanisms of inclusion in the first place. Cultural norms and normalised racist discrimination might not only prevent members of marginalised groups from accessing these legislative bodies, but hinder their performance once they get there. Quotas would solve, if any, only the first of these problems.

Therefore, more than an encouragement to promote and secure descriptive representation, this paper is a call for further research. It is important to understand what the data I present here is, but it is critical to understand what it is not. This data is just but one step towards revealing the impact of skin colour discrimination in Mexican politics. The underrepresentation this research unveils could be a random occurrence or the result of other, more salient, factors. Thus, it is imperative to investigate whether this descriptive underrepresentation is a symptom of a larger lack of racial substantial representation and/or skin colour discrimination within the Chamber of Deputies (and other political structures) in Mexico. Further research in this direction should test the explicative power of skin colour against variables such as committee leadership, legislation production/success rate, and legislative effectiveness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Algazi, L. B., and S. B. Juárez. 2016. “El proceso legislativo en México: La eficiencia de las comisiones permanentes en un Congreso sin mayoría.” Perfiles Latinoamericanos 24 (48): 111–140. doi:10.18504/pl2448-005-2016.

- Angosto Ferrández, L. F., and S. Kradolfer. 2012. “Race, Ethnicity and National Censuses in Latin American States: Comparative Perspectives.” In Everlasting Countdowns: Race, Ethnicity and National Censuses in Latin American States, edited by L. F. Angosto Ferrández and S. Kradolfer, 1–40. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Arceo-Gomez, E. O., and R. M. Campos-Vazquez. 2014. “Race and Marriage in the Labor Market: A Discrimination Correspondence Study in a Developing Country.” American Economic Review 104 (5): 376–380. doi:10.1257/aer.104.5.376.

- Bailey, S. R. 2009. “Public Opinion on Nonwhite Underrepresentation and Racial Identity Politics in Brazil.” Latin American Politics and Society 51 (4): 69–99. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2009.00064.x.

- Banton, M. 2012. “The Colour Line and the Colour Scale in the Twentieth Century.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (7): 1109–1131. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.605902.

- Bárcena Juárez, S. 2017. “Involucramiento legislativo sin reelección: La productividad de los diputados federales en México, 1985-2015.” Política y Gobierno 24 (1): 45–79.

- Bárcena Juárez, S. A. 2018. “¿Cómo evaluar el desempeño legislativo? Una propuesta metodológica para la clasificación de las iniciativas de ley en México y América Latina.” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales 64 (235): 395–426. doi:10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2019.235.63130.

- Barragan, A. 2020. “Yásnaya Aguilar: “Las lenguas indígenas no se mueren, las mata el Estado mexicano”.” Verne. https://verne.elpais.com/verne/2019/03/02/mexico/1551557234_502317.html.

- Béjar Algazi, L. 2006. Los partidos en el Congreso de la Unión: la representación parlamentaria después de la alternancia. Mexico City: UNAM-Guernika.

- Béjar Algazi, L. 2012. “¿Quién legisla en México? Descentralización y proceso legislativo.” Revista Mexicana de Sociología, Octubre-Diciembre 74 (4): 619–647. doi:10.22201/iis.01882503p.2012.4.34446.

- Bird, K. 2004. The Political Representation of Women and Ethnic Minorities in Established Democracies: A framework for Comparative Research. McMaster University. http://ipsa-rc19.anu.edu.au/papers/bird.htm#_ftn5.

- Bird, K. 2005. “The Political Representation of Visible Minorities in Electoral Democracies: A Comparison of France, Denmark, and Canada.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 11 (4): 425–465. doi:10.1080/13537110500379211.

- Bird, K. 2014. “Ethnic Quotas and Ethnic Representation Worldwide.” International Political Science Review 35 (1): 12–26. doi:10.1177/0192512113507798.

- Broockman, D. E. 2013. “Black Politicians Are More Intrinsically Motivated to Advance Blacks’ Interests: A Field Experiment Manipulating Political Incentives.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (3): 521–536. doi:10.1111/ajps.12018.

- Bueno, N. S., and T. Dunning. 2016. Race, Resources, and Representation: Evidence from Brazilian Politicians. UNU-WIDER. doi:10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2016/188-8

- Burlet, S., and H. Reid. 1998. “A Gendered Uprising: Political Representation and Minority Ethnic Communities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21 (2): 270–287. doi:10.1080/014198798330016.

- Campos-Vazquez, R. M., and E. M. Medina-Cortina. 2019. “Skin Color and Social Mobility: Evidence from Mexico.” Demography 56 (1): 321–343. doi:10.1007/s13524-018-0734-z.

- Campos-Vazquez, R. M., and C. Rivas-Herrera. 2021. “The Color of Electoral Success: Estimating the Effect of Skin Tone on Winning Elections in Mexico.” Social Science Quarterly 102 (2): 844–864. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12933.

- Campos, L. A., and C. Machado. 2018. “The Colour of the Elected: Determinants of the Political Under-Representation of Blacks and Browns in Brazil.” World Political Science 14 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1515/wps-2018-0001.

- Carey, J. M. 1994. “Los efectos del ciclo electoral sobre el sistema de partidos y el respaldo parlamentario al Ejecutivo.” Estudios Públicos 55: 305–313.

- CEPAL. 2020. “Aspectos conceptuales de los censos de población y vivienda: desafíos para la definición de contenidos incluyentes en la ronda 2020 (No. 94; Serie Seminarios y Conferencias).” www.cepal.org/apps.

- Cerón-Anaya, H. 2020. “La racialización de la clase en México.” Nexos. https://economia.nexos.com.mx/?p=3208&fbclid=IwAR24ypiVWfzzopoEMvQXOoRVf_MDGgOB0rn_Io9AGVF-Ku_23wVWi16bvH8.

- Corona, S. 2020. “El racismo es el motor del mestizaje en México.” El Pais. https://elpais.com/mexico/2020-07-04/el-racismo-es-el-motor-del-mestizaje-en-mexico.html.

- Del Popolo, F., A. M. Oyarce, S. Schkolnik, and F. Velasco. 2009. “Censos 2010 y la inclusión del enfoque étnico : hacia una construcción participativa con pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes de América Latina; (No. 57; Serie Seminarios y Conferencias).” Naciones Unidas, CEPAL.

- Del Popolo, F., and S. Schkolnik. 2012. “Indigenous Peoples and Afro-Descendants: The Difficult Art of Counting.” In Everlasting Countdowns: Race, Ethnicity and National Censuses in Latin American States, edited by L. F. Angosto Ferrández and S. Kradolfer, 304–334. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Eelbode, F., B. Wauters, K. Celis, and C. Devos. 2013. “Left, Right, Left. The Influence of Party Ideology on the Political Representation of Ethnic Minorities in Belgium.” Politics, Groups and Identities 1 (3): 451–467. doi:10.1080/21565503.2013.816244.

- Forest, B. 2001. “Mapping Democracy: Racial Identity and the Quandary of Political Representation.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91 (1): 143–166. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00237.

- Gonzales Matute, S. 2020. “Race, Gender and Power: Afro-Peruvian Women’s Experiences as Congress Representatives.” Master of Arts. University of South Florida.

- Grofman, B. 1982. “Should Representatives be Typical of Their Constituents?” In Representation and Redistricting Issues, edited by B. Grofman, A. Lijphart, R. B. McKay, and H. A. Scarrow, 97–99. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Grose, C. R. 2011. Congress in Black and White. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511976827

- Hanni, M., and T. Saalfeld. 2020. “Ethnic Minorities and Representation.” In Research Handbook on Political Representation, edited by M. Cotta and F. Russo, 222–235. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Htun, M. 2004. “Is Gender Like Ethnicity? The Political Representation of Identity Groups.” Perspectives on Politics 2 (3): 439–458. doi:10.1017/S1537592704040241.

- Htun, M. 2014. “Political Inclusion and Representation of Afrodescendant Women in Latin America.” In Representation, edited by M. C. Escobar-Lemmon and M. M. Taylor-Robinson, 118–134. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199340101.003.0007.

- Htun, M. 2015. Inclusion Without Representation in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139021067.

- Htun, M., and J. P. Ossa. 2015. “Indigenous Reservations and Gender Parity in Bolivia (Written with Juan Pablo Ossa).” In Inclusion Without Representation in Latin America, 70–92. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139021067.005.

- INE. 2023. Sistema Político Electoral Mexicano. Instituto Nacional Electoral. https://www.ine.mx/sobre-el-ine/sistema-politico-electoral/.

- INEGI. 2016. Módulo de Movilidad Social Intergeneracional 2016. Principales resultados y bases metodológicas. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/mmsi/2016/doc/principales_resultados_mmsi_2016.pdf.

- INEGI. 2022. “Estadísticas a propósito del día internacional de los pueblos indígenas [Press release].”

- Iturralde Nieto, G. 2018. “Invisivilidad. Las personas afrodescendientes y el racismo.” In Caja de herramientas para identificar el racismo en México, edited by G. I. Nieto. Afrodescendencias en México. Investigación e Incidencia, A.C. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139021067.005.

- Iturriaga, E. 2016. Las élites de la Ciudad Blanca: discursos racistas sobre la otredad. Mérida: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- James, M. R. 2011. “The Priority of Racial Constituency Over Descriptive Representation.” Journal of Politics 73 (3): 899–914. doi:10.1017/S0022381611000545.

- Janusz, A. 2018. “Candidate Race and Electoral Outcomes: Evidence from Brazil.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 6 (4): 702–724. doi:10.1080/21565503.2017.1279976.

- Janusz, A. 2019. “Race and Political Representation in Brazil [PhD].” University of California, San Diego.

- Jewell, M. E. 1983. “Legislator-Constituency Relations and the Representative Process.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 8 (3): 303. doi:10.2307/439589.

- Johnson, O. A. I. 1998. “Racial Representation and Brazilian Politics: Black Members of the National Congress, 1983-1999.” Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 40 (4): 97–118. doi:10.2307/166456.

- Johnson, O. A. I. 2015. “Blacks in National Politics.” In Race, Politics, and Education in Brazil, edited by O. A. I. Johnson, and R. Heringer, 17–58. Palgrave Macmillan US. doi:10.1057/9781137485151.

- Johnson, M. 2017. “Racialized Democracy: The Electoral Politics of Race in Panama.” PhD. Princeton University.

- Juenke, E. G., and P. Shah. 2016. “Demand and Supply: Racial and Ethnic Minority Candidates in White Districts.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 1 (1): 60–90. doi:10.1017/rep.2015.2.

- Knight, A. 1990. “The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870–1940.” In Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo: Mexico, 1910–1940, edited by R. Graham, 71–114. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Krozer, A. 2019. “Élites y racismo: el privilegio de ser blanco (en México), o cómo un rico reconoce a otro rico.” Nexos. https://economia.nexos.com.mx/?p=2153.

- Levitin, C. 2011. “The Mexican Caste System.” San Diego Reader. https://www.sandiegoreader.com/weblogs/fulano_de_tal/2011/nov/04/the-mexican-caste-system/#.

- López Chávez, A. N.-H. 2018. “La movilización etnopolítica afromexicana de la Costa Chica de Guerrero y Oaxaca: logros, limitaciones y desafíos.” Perfiles Latinoamericanos 26 (52): 1–33. doi:10.18504/pl2652-010-2018.

- Loveman, M. 2014. National Colors. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199337354.001.0001.

- Lublin, D. 1997. The Paradox of Representation. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9780691221397.

- Machado, C. A., L. A. Campos, and F. Recch. 2019. “Race and Competitiveness in Brazilian Elections: Evaluating the Chances of Black and Brown Candidates Through Quantile Regression Analysis of Brazil’s 2014 Congressional Elections.” Brazilian Political Science Review 13(3), doi:10.1590/1981-3821201900030003.

- Madrid, R. 2005. “Ethnic Cleavages and Electoral Volatility in Latin America.” Comparative Politics 38 (1): 1. doi:10.2307/20072910.

- Malhotra, N., and C. Raso. 2007. “Racial Representation and U.S. Senate Apportionment.” Social Science Quarterly 88 (4): 1038–1048. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00517.x.

- Mansbridge, J. 2009. “A Selection Model of Political Representation.” Journal of Political Philosophy 17 (4): 369–398. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2009.00337.x.

- Martin, N. S., and S. Blinder. 2021. “Biases at the Ballot Box: How Multiple Forms of Voter Discrimination Impede the Descriptive and Substantive Representation of Ethnic Minority Groups.” Political Behavior 43 (4): 1487–1510. doi:10.1007/s11109-020-09596-4.

- Martınez Casas, R., E. Saldivar, R. Flores, and C. Sue. 2014. “The Different Faces of Mestizaje: Ethnicity and Race in Mexico.” In Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America, edited by E. Telles, 36–80. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Mitchell-Walthour, G. 2017. The Politics of Blackness. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316888742.

- Mitchell, G. 2010. “The Politics of Skin Color in Brazil.” Review of Black Political Economy 37 (1): 25–41. doi:10.1007/s12114-009-9051-5.

- Moreno Figueroa, M. 2008. “Historically Rooted Transnationalism: Slightedness and the Experience of Racism in Mexican Families.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 29 (3): 283–297. doi:10.1080/07256860802169212.

- Moreno Figueroa, M. 2010. “Distributed Intensities: Whiteness, Mestizaje and the Logics of Mexican Racism.” Ethnicities 10 (3): 387–401. doi:10.1177/1468796810372305.

- Moser, R. G. 2008. “Electoral Systems and the Representation of Ethnic Minorities Evidence from Russia.” Comparative Politics 40 (3): 273–292. doi:10.5129/001041508X12911362382995.

- Mügge, L. M., D. J. van der Pas, and M. van de Wardt. 2019. “Representing Their Own? Ethnic Minority Women in the Dutch Parliament.” West European Politics 42 (4): 705–727. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1573036.

- Nohlen, D. 1994. Sistemas electorales y partidos políticos. Mexico City: UNAM-FCE.

- Phillips, A. 1998. The Politics of Presence. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Phillips, A. 2001. “Representation Renewed.” In Speaking for the People: Representation in Australian Politics, edited by M. Sawer and G. Zappalà, 19–35. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Pitkin, H. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ramirez, J., and A. Campos. 2017. “Afrodescendientes como candidatos políticos en el Perú: una mirada a su participación en las elecciones generales del 2016.” In Observa Igualdad. JNE – Observa Igualdad. https://observaigualdad.jne.gob.pe/documentos/recursos/reportes/Afrodescendientes%20como%20candidatos%20pol%C3%ADticos%20en%20el%20Per%C3%BA-Una%20mirada%20a%20su%20participaci%C3%B3n%20en%20las%20elecciones%20generales%20del%202016.pdf.

- Rejón Piña, R. 2022. “Avoiding Backlash: Narratives and Strategies for Anti-racist Activism in Mexico.” Ethnicities. OnlineFirst. doi:10.1177/14687968221128381

- Rejón Piña, R., and C. Ma. 2023. “Classification Algorithm for Skin Color (CASCo): A New Tool to Measure Skin Color in Social Science Research.” Social Science Quarterly 104 (2): 168–179. doi:10.1111/ssqu.13242.

- Rivera Sánchez, J. 2004. “Cambio institucional y democratización: La evolución de las comisiones en la Cámara de Diputados de México.” Política y Gobierno XI (2): 263–313.

- Roth, W. 2012. Race Migrations: Latinos and the Cultural Transformation of Race. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Ruedin, D. 2009. “Ethnic Group Representation in a Cross-National Comparison.” Journal of Legislative Studies 15 (4): 335–354. doi:10.1080/13572330903302448.

- Ruiz-Rufino, R. 2013. “Satisfaction with Democracy in Multi-ethnic Countries: The Effect of Representative Political Institutions on Ethnic Minorities.” Political Studies 61(1): 101–118. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00955.x.

- Russell, P. 2010. The History of Mexico: From Pre-conquest to Present. New York: Routledge.

- Saldívar, E. 2014. “‘It’s Not Race, It’s Culture’: Untangling Racial Politics in Mexico.” Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 9 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1080/17442222.2013.874644.

- Saldívar, E., and C. Walsh. 2014. “Racial and Ethnic Identities in Mexican Statistics.” Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research 20 (3): 455–475. doi:10.1080/13260219.2014.996115.

- Secretaría de Gobernación. 2017. Mesa Directiva. Sistema de Información Legislativa. http://sil.gobernacion.gob.mx/Glosario/definicionpop.php?ID=156#:~:text=En%20la%20C%C3%A1mara%20de%20Diputados,por%20no%20ejercer%20dicho%20derecho.

- Secretaría General. 2022. Álbum de Diputadas y Diputados 2021-2024. Cámara de Diputados.

- Sen, M., and O. Wasow. 2016. “Race as a Bundle of Sticks: Designs that Estimate Effects of Seemingly Immutable Characteristics.” Annual Review of Political Science 19: 499–522. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-032015-010015.

- Shugart, M. S., and J. M. Carey. 1992. Presidents and Assemblies. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139173988.

- Solís, P., B. Güémez Graniel, and V. Lorenzo Holm. 2019. Por mi raza hablará la desigualdad.Efectos de las características étnico-raciales en la desigualdad de oportunidades en México. Mexico City: OXFAM Mexico.

- Sue, C. 2013. Land of the Cosmic Race: Race, Mixture, Racism and Blackness in Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sue, C. 2020. “The Dynamics of Color.” In Shades of Difference, edited by E. Nakano Glenn, 114–128. Stanford University Press. doi:10.1515/9780804770996-009.

- Sue, C., F. Riosmena, and E. Telles. 2021. How the 2020 Census Found No Black Disadvantage in Mexico: The Effects of State Ethnoracial Constructions on Inequality (No. 20215; CPIPWorking Paper Series).

- Telles, E. 2004. Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Telles, E. 2012. “The Overlapping Concepts of Race and Colour in Latin America.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (7): 1163–1168. doi:10.1080/01419870.2012.657209.

- Telles, E., ed. 2014. Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Telles, E., R. D. Flores, and F. Urrea-Giraldo. 2015. “Pigmentocracies: Educational Inequality, Skin Color and Census Ethnoracial Identification in Eight Latin American Countries.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 40: 39–58. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2015.02.002.

- Telles, E., and T. Paschel. 2014. “Who Is Black, White, or Mixed Race? How Skin Color, Status, and Nation Shape Racial Classification in Latin America.” American Journal of Sociology 120 (3): 864–907. doi:10.1086/679252.

- Thernstrom, A. M. 1982. “The Right of Ethnic Minorities to Political Representation.” In Minorities: Community and Identity: Report of the Dahlem Workshop on Minorities: Community and Identity, edited by C. Fried, 329–340. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Tipa, J. 2020. “Colourism in Commercial and Governmental Advertising in Mexico: ‘International Latino’, Racism and Ethics.” Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 15 (2): 112–128. doi:10.16997/wpcc.379.

- Trejo, G., and M. Altamirano. 2016. “The Mexican Color Hierarchy.” In The Double Blind: The Politics of Racial and Class Inequalities in the Americas, edited by J. Hooker and A. B. Tillery, 1–14. Washington, DC: American Political Science Association.

- Vasconcelos, J. 1948. La Raza Cósmica. Mexico City: Espasa-Calpe.

- Vaughn, B. 2013. “México Negro: From the Shadows of Nationalist Mestizaje to New Possibilities in Afro-Mexican Identity.” The Journal of Pan African Studies 6 (1): 227–240.

- Velazquez, M. E., and G. Iturralde Nieto. 2012. Afrodescendientes en Mexico. Una historia de silencio y discriminacion (2nd ed.). Mexico City: CONAPRED-INAH.

- Villarreal, A., and S. R. Bailey. 2020. “The Endogeneity of Race: Black Racial Identification and Men’s Earnings in Mexico.” Social Forces 98 (4): 1744–1772. doi:10.1093/sf/soz096.

- Wade, P. 2012. “Skin Colour and Race as Analytic Concepts.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (7): 1169–1173. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.632428.

- Weeks, A. C. 2018. “Why Are Gender Quota Laws Adopted by Men? The Role of Inter- and Intraparty Competition.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (14): 1935–1973. doi:10.1177/0010414018758762.

- Zappalà, G. 1998. “The Influence of the Ethnic Composition of Australian Federal Electorates on the Parliamentary Responsiveness of MPs to Their Ethnic sub-Constituencies.” Australian Journal of Political Science 33 (2): 187–209. doi:10.1080/10361149850606.

- Zappalà, G. 2001. “The Political Representation of Ethnic Minorities: Moving Beyond the Mirror.” In Speaking for the People: Representation in Australian Politics, edited by M. Sawer and Zappalà Gianni, 134–161. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.