ABSTRACT

Some studies show that people with friends of different races also have lower levels of implicit racial bias. Yet, other studies do not replicate this finding. The omission of political parties from this research may explain its contradictory results, given the central role that race has played in the polarization of US society. Recent scholarship shows that political partisanship influences whether intergroup friendships improve explicit (i.e. conscious) attitudes. However, no studies have asked if friendships with African Americans have differing effects on white Democrats’ and Republicans’ anti-Black implicit bias. This paper examines this question by analyzing Race IAT and survey responses from 1,868 white Americans. Results reveal that white Democrats and Republicans maintain friendships with African Americans at similar rates. Yet, having Black friends only predicts weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats. This finding suggests that partisan differences in interracial friendship dynamics may shape implicit racial attitudes.

Introduction

Anti-Black implicit bias affects most white Americans’ behavior unbeknownst to them, fueling unconscious discrimination against African Americans in schools (Chin et al. Citation2020; Jacoby-Senghor, Sinclair, and Nicole Shelton Citation2016), courtrooms (Rachlinski et al. Citation2009), hospitals (Green et al. Citation2007), and countless other social contexts. Allport (Citation1954) famously hypothesized that intergroup contact reduces outgroup prejudice under the right conditions, and Pettigrew (Citation1998, 75–77) argues that friendships, in particular, generate conditions that weaken bias. A substantial literature demonstrates that intergroup friendships correlate with more positive attitudes toward the outgroup (e.g. Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006, 760); however, this research focuses exclusively on explicit (i.e. conscious) attitudes. While an emerging literature has begun to examine whether having Black friends is associated with weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Americans, the findings from this work are inconsistent (Aberson Citation2019; Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004; Henry and Hardin Citation2006).

This inconsistency may be partly due to the omission of political parties from this research. Given the profoundly polarizing nature of racialized policies and discourse in the Trump Era, friendships with African Americans might have different effects on white Democrats’ and Republicans’ anti-Black implicit bias. However, no studies have asked whether party affiliation moderates the association between interracial friendships and implicit bias. In contrast, recent work on intergroup friendships and explicit attitudes has examined partisanship as a moderator. This research finds that friendships with Latinos in the United States (Pearson-Merkowitz, Filindra, and Dyck Citation2016) and immigrants in various countries (Homola and Tavits Citation2018; Thomsen and Rafiqi Citation2019) coincide with more positive explicit attitudes about immigration – but only among political leftists. Political rightists maintain or double down on their negative explicit attitudes about immigration, even when they have Latino or immigrant friends.

To explain these findings, researchers reference motivated reasoning (Kunda Citation1990), a common way of processing information that leads people to reject new facts that conflict with their established views (Homola and Tavits Citation2018; Thomsen and Rafiqi Citation2019). Motivated reasoning sheds plausible insight into the construction of explicit attitudes, but it does not address the more passive processes that shape implicit racial bias. One of these processes, evaluative conditioning, operates through repeated positive or negative exposures to a racial group (e.g. Olson and Fazio Citation2006; see also De Houwer, Thomas, and Baeyens Citation2001). Based on the logic of evaluative conditioning, social psychologists argue that interracial friendships should reduce implicit racial bias by giving people more positive contact with the outgroup (e.g. Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004, 337, 344).

However, if white Republicans have more exposure to anti-Black messages – in informal interactions with non-Black friends and/or news media – those exposures could counteract any positive effects of their friendships with African Americans on their implicit attitudes. This is one mechanism through which party affiliation may inform the association between having Black friends and anti-Black implicit bias. Another possible mechanism is partisan differences in “automatic social tuning.” Experimental research suggests that this factor may be significant if white Democrats feel more motivated to manage their own racial prejudice in interactions with Black friends (see Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001). Finally, arguments highlighting “mere exposure” as a possible shaper of implicit attitudes (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007) suggest that if white Democrats simply interact more with their Black friends, those interactions could lead to bigger reductions in their anti-Black implicit bias. Each of these perspectives suggests that friendships with African Americans may predict weaker implicit racial bias among white Democrats, but not white Republicans.

This paper examines this hypothesis by analyzing Race Implicit Association Test (IAT) scores and survey responses from 1,868 white Americans. The sample is weighted to be nationally representative with regard to age, gender, level of education, political party affiliation, and census region. Means comparisons and OLS regressions show that white Democrats and Republicans maintain friendships with African Americans at similar rates. Yet, having Black friends only maps onto weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats. These findings suggest that partisan differences in interracial friendship dynamics, other informal interactions, and/or news media consumption may contribute to differing levels of anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats and Republicans.

Implicit racial bias

Implicit racial bias refers to attitudes that are automatic, generally unconscious, and more predictive of spontaneous behavior than explicit racial attitudes (e.g. Greenwald and Krieger Citation2006). Implicit racial bias is made up of rapid-fire positive or negative associations with a racial group.Footnote1,Footnote2 Because it shapes behavior, this bias also perpetuates discrimination – even on the part of many people who strongly disagree with racist ideas (e.g. Quillian Citation2006). At the county level, teachers’ anti-Black implicit bias is associated with larger disparities between Black and white students’ test scores and suspensions (Chin et al. Citation2020; see also Jacoby-Senghor, Sinclair, and Nicole Shelton Citation2016). This bias also reduces the quality of healthcare that doctors provide to Black patients (Green et al. Citation2007), and it causes white trial judges to give the harshest sentences to Black juvenile defendants – unless the judges are highly motivated to stop their biases from playing out in their behavior (Rachlinski et al. Citation2009).

In addition to the fact that implicit bias harms African Americans in countless social contexts, its prevalence in the US population is alarming. According to one study, 72 per cent of white Americans have anti-Black implicit bias (Greenwald and Krieger Citation2006, 958). Psychological research traces the roots of this bias to personality traits and cognition (Livingston and Drwecki Citation2007; Phillips and Ziller Citation1997; Rowatt and Franklin Citation2004); however, social psychological work suggests that implicit bias is shaped, at least in part, by social factors. This research shows that white Americans’ anti-Black implicit bias may vary by age, gender, level of education, and political ideology (Greenwald and Krieger Citation2006, 958; Nosek et al. Citation2007).Footnote3

Yet, even as sociologists of racial attitudes have called for greater attention to implicit bias, sociology has hardly considered it (Quillian Citation2006, 323–324).Footnote4 Despite this gap, information on the social determinants of anti-Black implicit bias could inform programs and policies to reduce it. Such interventions could lessen discrimination against African Americans across the United States. The present study draws on work by social psychologists and political scientists to hypothesize that friendships with African Americans reduce anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats but not white Republicans. It asks: 1) Are friendships with African Americans negatively associated with anti-Black implicit bias among white Americans? 2) Do political parties moderate this association?

The promise of interracial friendship

In what follows, I describe classic scholarship on intergroup contact in general and friendships in particular. Then, I review a growing set of studies that examine whether having Black friends is associated with weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Americans.

Allport (Citation1954) famously hypothesized that interracial contact must meet the right conditions to weaken racial prejudice. In the decades since, social psychologists have focused on four conditions from Allport’s substantial inventory: equal status, common goals, cooperation, and approval from culture, customs, and other kinds of social “authority” (262–263). Numerous correlational studies find that interracial contact maps onto weaker explicit racial bias and that, when Allport’s four commonly cited conditions are met, they strengthen this association (Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006, 766; Pettigrew et al. Citation2011, 275). Pettigrew (Citation1998) builds on Allport (Citation1954) by proposing that intergroup contact that has the potential to develop into friendship will reduce prejudice. Pettigrew argues this is the case because friendships foster closeness and empathy while reducing intergroup anxiety. Many empirical studies affirm that intergroup friendships are associated with weaker explicit racial attitudes (Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006, 760; Pettigrew et al. Citation2011, 275–276).

Even so, this research does not address whether friendships with African Americans correspond with weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Americans. Only a few social psychological studies have examined this exact hypothesis. While some findings confirm it (Aberson Citation2019; Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004), others do not (e.g. Henry and Hardin Citation2006). Research on interracial friendships and implicit bias among and against other racial groups also lacks consensus. Several studies show that Asian/Pacific Islander and Latino respondents with Black friends (Aberson Citation2019), white respondents with Latino friends (Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004), and Black respondents with white friends (Henry and Hardin Citation2006) all have lower levels of implicit bias against the relevant outgroup. However, other work finds that friendships between white English and South Asian respondents do not predict weaker implicit bias among either group (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007). In addition to this literature’s conflicting conclusions, its focus on racial groups with distinct social histories in varying national contexts likely minimizes the applicability of its findings to white Americans’ anti-Black implicit bias.

Meanwhile, research examining this specific bias may be inconclusive partly because it overlooks political parties (Aberson Citation2019; Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004; Henry and Hardin Citation2006). As a result, this work disregards the possibility that white Americans’ partisanship helps to determine whether their friendships with African Americans reduce their implicit racial bias. Nevertheless, the central role that race has played in the polarization of the contemporary United States suggests that this could be the case. Before considering possible mechanisms, the following section reviews studies showing that explicit attitudinal responses to intergroup friendships may differ by political party.

Partisan constraints on the promise of interracial friendship

Gordon Allport included social characteristics in his initial inventory of conditions under which intergroup contact might reduce prejudice (Citation1954, 263).Footnote5 While existing scholarship indicates that contact predicts more positive explicit attitudes regardless of respondents’ age and gender (Pettigrew et al. Citation2011, 276; but see also Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006), recent work demonstrates that partisanship may inform this association. Pearson-Merkowitz, Filindra, and Dyck (Citation2016) report that non-Latinos with Latino friends in the United States are more likely to support a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants – if they are Democrats. There is no such association among Republicans.

Similarly, Homola and Tavits (Citation2018) find that native-born Americans and Germans who are political leftists and have immigrant friends also hold weaker feelings of immigration-related threat. However, among political rightists in each country, friendships with immigrants are not associated with immigration-related threat, or they predict greater threat. Finally, Thomsen and Rafiqi (Citation2019) show that political ideology moderates the association between friendships with immigrants and opposition to immigration in 21 European countries, such that leftists with immigrant friends express weaker opposition than their rightist counterparts (but see also Graf and Sczesny Citation2019).

To make sense of these findings, researchers highlight motivated reasoning (Kunda Citation1990), a common way of interpreting information that leads people to insist on logic that supports their pre-existing views, while disregarding evidence that challenges them. Homola and Tavits (Citation2018) argue that motivated reasoning may encourage leftists, who tend to value tolerance, to willingly reconsider any negative explicit attitudes as a result of their intergroup friendships. At the same time, rightists, who tend to accept inequality, may hold onto their negative views regardless of their positive experiences with outgroup friends (see also Thomsen and Rafiqi Citation2019).

Motivated reasoning provides a compelling explanation for partisan differences in the correlation between intergroup friendships and explicit attitudes. However, this mechanism is not pertinent to the passive processes that shape implicit bias, like evaluative conditioning: repeated positive or negative contact that leads people to form new associations with a racial group (or another attitude object) (Walther, Nagengast, and Trasselli Citation2005; see also De Houwer, Thomas, and Baeyens Citation2001). Experiments demonstrate the effects of evaluative conditioning by capturing shifts in respondents’ implicit bias after many exposures to images of Black and white individuals (Olson and Fazio Citation2006), the words “youth” and “elderly” (Karpinski and Hilton Citation2001) or meaningless nonwords (Mitchell, Anderson, and Lovibond Citation2003) on one hand, and positive or negative words on the other (Karpinski and Hilton Citation2001; Mitchell, Anderson, and Lovibond Citation2003; Olson and Fazio Citation2006; for further discussion, see Gawronski and Bodenhausen Citation2006).

Scholars of intergroup contact nod to evaluative conditioning when they hypothesize that interracial friendships should weaken implicit racial bias by giving people more positive exposure to the outgroup (e.g. Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004, 337, 344). However, in the deeply polarized context of the contemporary United States, this hypothesis might apply more to white Democrats than Republicans. While the present study’s correlational design does not allow for causal conclusions, the following discussion describes several speculative mechanisms. In addition to evaluative conditioning, two theoretical perspectives provide motivation: “automatic social tuning” (Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001; Sinclair et al. Citation2005) and “mere exposure” (see Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007, 384).

By the logic of evaluative conditioning, differences in the quantity and quality of white Democrats’ and Republicans’ exposures to African Americans should lead to differing levels of anti-Black implicit bias. At the same time, recent scholarship suggests that white Republicans may encounter more negative ideas about African Americans in their daily lives. Political science research shows that party affiliation has corresponded increasingly with Americans’ explicit racial attitudes over the past decade (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Citation2018). Republicans are now more likely than Democrats to view African Americans negatively (see also Tesler Citation2013). Given this difference and the rarity of cross-party friendships (Pew Research Center Citation2017), white Republicans may socialize more with peers who espouse anti-Blackness. Similarly, partisan differences in news media consumption (e.g. el-Nawawy and Elmasry Citation2021) might expose white Republicans to more negative discourse about African Americans. One or both of these factors could strengthen white Republicans’ anti-Black implicit bias enough to counterbalance any positive associations that they form with their Black friends.

While evaluative conditioning points to plausible mechanisms, this framework also focuses somewhat narrowly on the accumulation of squarely positive or negative associations. Meanwhile, research on “automatic social tuning” acknowledges that interracial friendships may also shape white partisans’ implicit bias in more complex ways (Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001; Sinclair et al. Citation2005). One study shows that white (but not Asian American) college students display less anti-Black implicit bias in the presence of a Black experimenter than they do in the presence of a white experimenter. The authors draw on shared reality theory to argue that in the US context, where racial discourse often focuses on Black–white relations, white respondents may feel motivated to regulate their own racial prejudice when they encounter a Black person. This motivation might prompt an unconscious “social tuning” process that inhibits their anti-Black implicit bias. Asian Americans may not experience the same kind of social influence because they do not consider themselves responsible for racial inequality (Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001).

Given that the participants in this research were college students, Republicans were likely underrepresented among them (partisanship does not appear in the analyses). Nonetheless, this work helps to explain how having Black friends could generate different effects on white Democrats’ and Republicans’ anti-Black implicit bias. To the extent that white Democrats want to manage their racial prejudice in interactions with Black friends, they may experience automatic social tuning that diminishes their implicit racial bias. At the same time, if white Republicans feel that their anti-Black attitudes are justified (e.g. Tesler Citation2013), their implicit bias may remain unchanged in similar interactions.Footnote6,Footnote7 This hypothesis counters evaluative conditioning by suggesting that white Republicans might feel positively toward their Black friends while nonetheless engaging with them in ways that preserve their implicit racial bias.

This is not, however, to suggest that white Democrats never interact with their Black friends in problematic ways. Interviews with white women who oppose racism (and thus likely skew Democratic) reveal that, despite their good intentions, their behavior toward their Black friends is sometimes condescending and self-congratulatory (Trepagnier Citation2001; see also Munn Citation2018). Nonetheless, these respondents’ concern about their own missteps suggests that their self-monitoring may encourage automatic social tuning, which could reduce their anti-Black implicit bias.

Beyond social tuning and evaluative conditioning, partisan differences in “mere exposure” to Black friends may lead to bigger declines in white Democrats’ anti-Black implicit bias. One study finds that exposure to South Asians (i.e. the proportion of South Asians seen on a typical day and living in respondents’ neighborhoods) covaries with implicit bias among white British respondents (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007). The authors posit that greater opportunities for intergroup contact reduce implicit bias, regardless of how positive that contact is (see also Prestwich et al. Citation2008). This argument suggests that, if white Democrats simply interact more with Black friends (no matter their conscious beliefs about African Americans or how motivated they are to manage their racial prejudice in those interactions), they may experience greater reductions in their anti-Black implicit bias.Footnote8

These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; to the extent that one or more operate as hypothesized, friendships with African Americans may predict less anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats but not white Republicans.

Data and methods

I test this hypothesis by analyzing Race Implicit Association Test scores and survey responses from a pooled sample of 1,868 white Americans. I compare the mean IAT scores of respondents who do and do not have one or more Black friends and of Democrats and Republicans before regressing IAT score on friendships with African Americans. Then, I introduce interactions between political parties and friendships with African Americans, as well as controls for partisanship and other potentially significant predictors.

Data

The sampling service YouGov constructed two samples of white participants – the first in summer 2017 (N = 376) and the second in summer 2022 (N = 1,492). In summer 2017, 480 participants completed Wave 1 (a survey) and 416 completed Wave 2 (the Race IAT). Of these respondents, YouGov included 380 in the final matched and weighted dataset. Three more were later dropped due to their excessively fast responses on the IAT, in addition to one who skipped the friendship questions. In summer 2022, 4,555 participants completed Wave 1 (a survey) and 3,466 completed Wave 2 (the Race IAT). Of these, YouGov included 1,500 in the final matched and weighted dataset; eight more were later dropped because they had also participated in 2017.

YouGov drew both samples from its large pool of opt-in participants. All of the respondents were born and raised in the United States, and each sample is weighted to be nationally representative with regard to age, gender, highest level of education, political party identification, and census region.Footnote9 This sampling approach ensures more external validity than existing studies of interracial friendship and implicit racial bias, which rely on small samples of young respondents (Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004; Henry and Hardin Citation2006; Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007) or a large sample of people who voluntarily chose to measure their implicit racial bias online (Aberson Citation2019). Across the two samples pooled in the present study, there is no significant difference in rates of friendship with African Americans. Levels of anti-Black implicit bias are slightly higher on average (by 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05)) in the 2017 sample.

Procedure

The procedure for data collection in summer 2017 was consistent with that in summer 2022. After consenting to participate in a study of “Americans’ daily interactions and their viewpoints on a variety of topics” (by reading an online consent form and checking a box), respondents completed Wave 1, an online survey. The survey began with a “name generator” (Burt Citation1984) that asked respondents to list the initials of up to six of their close friends. Next, they answered a few questions about themselves. The survey then displayed the initials of their friends again and asked respondents to identify several demographic characteristics, including the race, of each friend. Respondents also reported how frequently they saw or spoke with each friend on a four-point scale ranging from “less than once a year” to “at least once a week.” Finally, they indicated how close they felt with each friend on a five-point scale ranging from “not very” to “extremely.”

By first asking respondents to list their friends and later asking for each friend’s race, the name generator avoided prompting respondents who oppose racism to exaggerate about their friendships with African Americans. This is an improvement on past studies, which might have activated social desirability by asking respondents to self-report whether they have had or currently have a Black friend (Aberson Citation2019), the number of outgroup friends that they have (Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004; Henry and Hardin Citation2006; Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007), and/or how often they spend time with those friends (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007). After providing information about their friendships, respondents answered other questions not analyzed here.

Several weeks after completing the initial survey, respondents agreed to participate in a study “examining categorization processes among adult Americans.” They were not told that this study was related to the previous survey. After giving their consent, they completed Wave 2, an online Race Implicit Association Test, the most common measure for implicit racial bias. The administration of the IAT after the survey with questions about respondents’ friendships rectifies a potential weakness in some of the past scholarship on this topic. Specifically, participants in one study showing that friendships with African Americans predict weaker anti-Black implicit bias first completed an Implicit Association Test and then answered survey questions about their number of Black friends (Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004). This ordering may be problematic because respondents often recognize the purpose of implicit measures and experience frustration with their inability to stifle their own biased responses (see Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001). Administering the IAT first might have invited socially desirable reports about respondents’ friendships with African Americans, an issue that I avoid by administering the IAT several weeks after the survey.Footnote10,Footnote11

I built the IAT on the iatgen platform and ran it via Qualtrics (Carpenter et al. Citation2019). The IAT consists of four phases that take approximately five minutes to complete (see Greenwald and Krieger Citation2006, 952–953). In the first phase, a series of faces appear. Respondents practice using a key on one side of their computer keyboard to rapidly identify the faces of white Americans, and a key on the other side of their keyboard to rapidly identify the faces of Black Americans. In the second phase of the test, respondents practice using the same two keys to identify words that are “Good” on one hand and “Bad” on the other. The third and fourth phases of the test include practice trials to familiarize respondents with categorization tasks followed by test trials. In one of these phases, respondents press the key associated with the “Good” category when they see white faces or good words, and the other key when they see Black faces or bad words. In the other final phase, respondents press the key associated with the “Good” category when they see Black faces or good words, and the other key when they see white faces or bad words. These two phases appear in random order.

After dropping individual responses that are too slow (greater than 10,000 milliseconds) and participants whose responses are too fast overall (those whose latencies average less than 300 milliseconds in more than 10 per cent of the trials), the IAT is usually scored by calculating the mean differences in response times for the practice and test trials from phases three and four. Those mean differences are then divided by the standard deviation of response times (either to the test or the practice trials) and then averaged to produce “D scores.” Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (Citation2003) describe this calculation in greater detail.

Variables

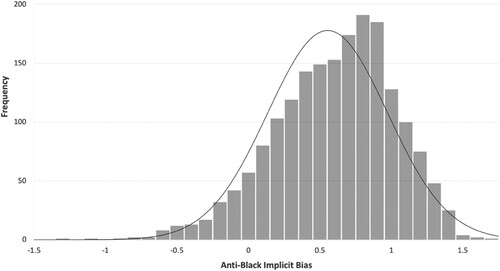

My outcome variable, anti-Black implicit bias, reflects respondents’ D scores on the Race IAT. Positive scores indicate an automatic preference for white Americans over Black Americans and negative scores indicate the opposite. Respondents’ IAT scores are normally distributed and the pooled mean (0.55) reflects a substantial (high–moderate) level of anti-Black implicit bias throughout the sample (see and ).

Figure 1. Histogram of Anti-Black Implicit Bias with Normal Curve Overlay (N = 1,868).

Note on IAT D scores: These scores are bounded within the range from −2 to 2. The break points for “slight” (+/−0.15), “moderate” (+/−0.35), and “strong” (+/−0.65) implicit bias are standard. I interpret D scores between −0.15 and 0.15 as negligible.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics (N = 1,868).

The independent variable one or more Black friends is a dummy variable with “no Black friends” reflected in the reference category (pooled mean = 0.09). Summary statistics of this variable indicate that friendships with African Americans are uncommon among white Americans. While 7.4 per cent of respondents (139) have one Black friend, only 1.4 per cent (26) have two Black friends, 0.05 per cent (1) have three Black friends, and 0.16 per cent (3) have four Black friends (see and ). In addition to analyzing the fact of having Black friends, I consider respondents’ frequency of interaction and feelings of closeness with them.

One prior paper on implicit bias measures the frequency of time spent with outgroup friends (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007). However, the authors use measures for interactional frequency that have an important shortcoming: they do not control for respondents’ propensity for frequent interaction with same-race friends. While white Americans who often interact with white friends might also be more likely to report frequent interactions with Black friends, those interactions may not be as consequential to their anti-Black implicit bias as they would be for white Americans who interact more rarely with white friends.

To address these shortcomings, I analyze frequency of interactions with Black friends, a ratio variable that shows how often respondents interact with African American friends, on average, in proportion to the average frequency of their interactions with their white friends (mean = 0.08).Footnote12 In addition, I consider closeness with Black friends, a ratio variable that reflects respondents’ average closeness with their Black friends, proportionate to their average closeness with their white friends (mean = 0.08).

To capture possible partisan differences in the association between having Black friends and anti-Black implicit bias, I also consider one or more Black friends*Democrat (mean = 0.04) and one or more Black friends*Independent (mean = 0.01). These variables reflect the interaction between one or more Black friends on one hand and dummy variables for Democrat (mean = 0.47) and Independent (mean = 0.14) (with Republicans in the reference category) on the other. Respondents categorized themselves with reference to a seven-point scale with the options “Strong Democrat” (27 per cent), “Not very strong Democrat” (9 per cent), “Lean Democrat” (11 per cent), “Independent” (14 per cent), “Lean Republican” (10 per cent), “Not very strong Republican” (10 per cent), and “Strong Republican” (19 per cent). Democrat is a dummy variable representing respondents who are strong or not very strong Democrats as well as those who lean Democrat (47 per cent); likewise, the “Republican” reference category includes strong and not very strong Republicans, along with those who lean Republican (39 per cent). The Independent variable includes those who are Independent as well as 17 respondents who indicated that they are unsure of their political party (14 per cent) (see ).

Because party affiliation in the US covaries with age, education, and place of residence (Pew Research Center Citation2015), the OLS regression models below also include a series of control variables. YouGov compiled data that I used to calculate the continuous variable age, measured in years and centered at the pooled mean (55.3) and a dummy variable for Woman, coded 1 if the respondent is a woman (50 per cent) and 0 otherwise.Footnote13 I also include dummy variables for some college (30 per cent), four-year college (25 per cent), and graduate school (15 per cent), with respondents who have completed high school or less education in the reference group. Finally, given the racial history of the Southern United States and the possibility that regional culture informs the construction of various racial attitudes (Blalock Citation1967; Maxwell and Shields Citation2019; Wilcox and Roof Citation1978), I include a dummy variable for lives in the South, coded 1 if the respondent lives in the South (32 per cent) and 0 if they live in another region (see ).

In what follows, I describe bivariate and OLS regression models of the relationships between having Black friends, party affiliation, and anti-Black implicit bias. Findings show that while white Democrats and Republicans are similarly likely to have Black friends, those friendships only predict weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats.

Are friendships with African Americans associated with weaker anti-Black implicit bias?

displays mean IAT scores by friendships with African Americans. It shows that on average, anti-Black implicit bias is slightly weaker among respondents who have one or more Black friends (0.49, SD 0.41) than among those who do not (0.56, SD 0.42). This small difference is nonetheless statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). Likewise, respondents’ average IAT scores diminish as their frequency of interaction with their Black friends proportionate to their white friends increases – from never (0.56, SD 0.42) to less often with Black than white friends (0.53, SD 0.37) to at least as often with Black as with white friends (0.44, SD 0.44). These differences are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) (see Table A2). Respondents’ anti-Black implicit bias also decreases on average as their feelings of closeness with their Black friends proportionate to their white friends increase from no closeness (0.56, SD 0.42) to less closeness with Black than with white friends (0.53, SD 0.39) to at least as much closeness with Black as with white friends (0.44, SD 0.42). These differences are also statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) (see Table A2). Together, these preliminary findings echo others suggesting that having Black friends reduces anti-Black implicit bias among white Americans (Aberson Citation2019; Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004). However, the addition of interactions between friendships with African Americans and political parties changes this story in the regression analyses below.

Table 2. Anti-Black implicit bias by friendships with African Americans (N = 1,868).

Do political parties moderate the association between friendships with African Americans and anti-Black implicit bias?

summarizes respondents’ number of Black friends and their average anti-Black implicit bias by political party. It shows that interracial friendships are just as uncommon among white Democrats as they are among white Republicans. Only 9.4 per cent of white Democrats and 8.2 per cent of white Republicans have one or more Black friends. This small partisan difference is not statistically significant. Likewise, very few white Democrats (1.0 per cent) and Republicans (1.7 per cent) have two Black friends, just one Democrat (0.11 per cent) has three Black friends and two Democrats (0.23 per cent) have four (see ). Respondents’ frequency of interaction and levels of closeness with their Black friends are also similarly low across party lines (see Table A3).

Table 3. Friendships with African Americans and Anti-Black Implicit Bias by Political Party Affiliation (N = 1,868).

While rates of friendship with African Americans as well as interactional frequency and feelings of closeness with them do not vary by political party, anti-Black implicit bias is stronger on average among white Republicans (0.63, SD 0.39) than Democrats (0.50, SD 0.43) (p ≤ 0.001) (see ). These findings challenge previous arguments that comparatively biased people (in this case, white Republicans) avoid intergroup contact much more than those who are less biased (see Pettigrew Citation1998, 69). In addition, these results establish that, like explicit anti-Black attitudes (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Citation2018), anti-Black implicit bias varies by party affiliation.

Ordinary Least Squares regressions allow for finer tests of the association between white Democrats’ and Republicans’ friendships with African Americans and their implicit racial bias. Model 1 of uses the fact of having one or more Black friends to predict anti-Black implicit bias with no controls. Friendships with African Americans are associated with a decrease of one-sixth of a standard deviation in anti-Black implicit bias, b = −0.07, t = −1.99, p ≤ 0.05. Likewise, OLS regressions using frequency of interaction and feelings of closeness with Black friends to predict implicit bias capture statistically significant associations of similar sizes (see Model 1 of Tables A4 and A5).

Table 4. OLS regression models predicting anti-Black implicit bias using friendships with African Americans and political party affiliation (N = 1,868).

Model 2 of tests whether friendships with African Americans predict anti-Black implicit bias while controlling for political parties – both alone and in interaction with those friendships. This model shows that having Black friends is only associated with white Democrats’ IAT scores, b = −0.19, t = −2.72, p ≤ 0.01. Considered alongside the insignificant coefficient for having Black friends among white Republicans (the reference group) – b = 0.02, t = 0.35, p = 0.73 – the coefficient for the interaction between having Black friends and Democratic affiliation indicates a reduction that is larger than one-third of a standard deviation in anti-Black implicit bias. This difference is large enough to move an individual’s IAT score at least halfway across the ranges for slight or moderate anti-Black implicit bias. Models using frequency of interactions and closeness with Black friends as the independent variable yield similar results (see Model 2 of Tables A4 and A5).

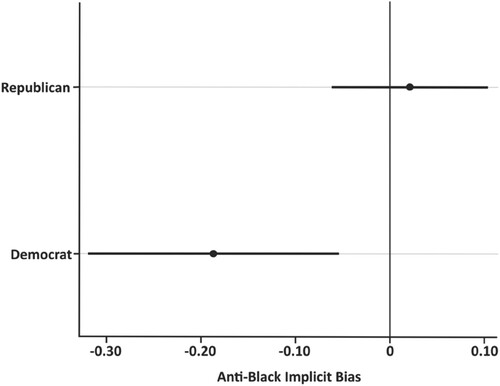

Model 3 of adds controls for age, gender, education, and residence in the South. The marginal effects plot in also presents the main results of this model. While there is no significant association between white Republicans’ friendships with African Americans and their anti-Black implicit bias, white Democrats’ friendships with African Americans are again associated with a decrease of – 0.19 in their IAT scores, t = −2.76, p ≤ 0.01. This model also suggests that political party affiliation and education are directly related to anti-Black implicit bias. Democrats’ and Independents’ IAT scores are one-fifth of a standard deviation lower than those of Republicans. Likewise, respondents who have completed some college, four years of college, or graduate education have scores that are one-fifth to one-quarter of a standard deviation lower than those who have completed high school or less. None of the other control variables are significant.Footnote14

Figure 2. Marginal Effect of Friendships with African Americans on Anti-Black Implicit Bias (N = 1,868).

Note: This figure displays 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Further models using frequency of interactions and closeness with Black friends to predict implicit racial bias with the same controls generate similar findings (see Model 3 of Tables A4 and A5). The coefficient for the interaction between frequency of interactions with Black friends and Democratic affiliation loses significance with the addition of controls (p = 0.06); however, this null finding may be due to standard error.

Discussion and conclusion

This study demonstrates that friendships with African Americans only predict weaker anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats. Below, I revisit possible mechanisms for this finding. Then, I discuss the theoretical and policy implications of this research and describe its limitations.

Psychologists posit that having Black friends should weaken white Americans’ anti-Black implicit bias by increasing their positive exposure to African Americans (Aberson, Shoemaker, and Tomolillo Citation2004). This argument is consistent with research on evaluative conditioning (see Gawronski and Bodenhausen Citation2006). However, I hypothesized that two factors might counterbalance this effect among white Republicans. First, given their stronger anti-Black explicit attitudes (e.g. Tesler Citation2013) and the partisan homogeneity of Americans’ social networks (Pew Research Center Citation2017), white Republicans may be exposed to more negative ideas about African Americans in informal interactions outside of those with their Black friends. Future in-depth interviews could examine this possibility by probing how white Democrats’ and Republicans’ non-Black friends talk to them about different racial groups. Second, partisan differences in news media consumption (e.g. el-Nawawy and Elmasry Citation2021) may expose white Republicans to more anti-Black discourse. Future quantitative research could test this hypothesis by adding time spent consuming left- and right-leaning media to analyses like those presented above.

I also argued that automatic social tuning might reduce anti-Black implicit bias among white Democrats, but not Republicans, who have Black friends. This hypothesis is motivated by the possibility that white Republicans feel less concerned about their racial attitudes when they engage with Black friends, a key mechanism for social tuning (see Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001). Qualitative work could examine this possibility by identifying exactly how white Democrats and Republicans experience and interpret their interactions with Black friends. Future lab experiments could also investigate whether party affiliation moderates the shifts in white Americans’ anti-Black implicit bias that occur as a result of social tuning in the presence of a Black experimenter (Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001).

Finally, I drew on evidence that “mere exposure” shapes implicit attitudes (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007) to posit that if white Democrats interact more with their Black friends, they may experience bigger drops in their anti-Black implicit bias. However, this study found no differences in the frequency with which white Democrats and Republicans engage with their Black friends (see Table A3). This result contradicts “mere exposure” within interracial friendships as a mechanism for the main finding. Even so, it bears noting that friendships are not an optimal case for studying “mere exposure” because people tend to experience them positively. Without substantial variance in contact quality (both positive and negative), it becomes challenging to distinguish between mere exposure and evaluative conditioning (see Prestwich et al. Citation2008, 584–585). Still, further quantitative work could examine whether white Democrats with Black friends also experience more pleasant and/or unpleasant exposure to African Americans in their daily lives (see Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007).

Short of specifying mechanisms, this research establishes that there are partisan differences in the association between white Americans’ friendships with African Americans and their anti-Black implicit bias. This finding 1) complicates Pettigrew’s (Citation1998) argument that “friendship potential” is a key condition for prejudice reduction and 2) highlights the importance of controlling for social factors beyond age and gender in research testing Pettigrew’s hypothesis.

In terms of policy, this research suggests that broad efforts to integrate American schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods cannot be expected to reduce all white Americans’ anti-Black implicit bias. Instead, interventions that are targeted to specific populations may hold the most promise. At the same time, the full OLS regression model predicting implicit bias using friendships with African Americans and party affiliation estimates an IAT score of 0.44 for white Democrats who have Black friends (see , Model 3).Footnote15 This score reflects a low-moderate level of anti-Black implicit bias, highlighting that those in this category are still subject to this bias. More research is needed to identify other social factors that can further improve white Americans’ implicit attitudes toward African Americans. Meanwhile, as long as Republican leaders and right-leaning news media normalize anti-Blackness and stoke fears that people of color are threatening white Americans’ social rank, the prospects for developing programs to reduce white Republicans’ implicit racial bias will likely remain dim.

As discussed above, an important limitation of this study is that it does not overcome the “causal sequence problem” (e.g. Pettigrew Citation1998). That is, if unbiased people seek out contact with outgroup members, and biased people avoid it, then this self-selection accounts for any relationship between intergroup contact and weak bias. However, the present study finds that white Republicans, who have stronger anti-Black implicit bias than white Democrats, nonetheless maintain friendships with African Americans at similar rates. This belies the alternative hypothesis suggested by the causal sequence problem. Even so, longitudinal research is needed to fully parse the effects of friendships with African Americans on implicit racial attitudes. A clear exemplar of the longitudinal approach is Shook and Fazio’s (Citation2008) study of implicit bias among college roommates. Yet, this study does not consider friendship as such or political partisanship (see also Levin, van Laar, and Sidanius Citation2003).

Over recent years, the social impacts of implicit bias have received widespread attention in academic journals and the popular press. This attention has been well-warranted, but surprisingly little is still known about the social construction of this bias. The potential significance of party affiliation as a shaper of anti-Black implicit bias in a context of stark political polarization suggests that the determinants of this bias may shift along with societies. This points to the necessity of ongoing sociological research, which could help to identify effective interventions to reduce implicit racial bias both now and in the future.

Ethics Statement

The protocol for this research was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at The University of California, Berkeley (Protocol ID 2016-03-8485).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48 KB)Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Cybelle Fox, David Harding, Shadrick Andrew Small, Sandra Susan Smith, Fithawee Tzeggai, Nyree Marchalle Young, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There is also an evaluative type of implicit bias that takes the form of stereotypic assessments.

2 The existence of implicit racial bias has been called into question by authors contending that measures to capture it instead reflect other psychological states or constructs (e.g. Tetlock and Mitchell Citation2008; Citation2009). However, dozens of studies systematically refute these arguments (Jost et al. Citation2009; Quillian Citation2008).

3 Further research shows that social context cues (Wittenbrink, Judd, and Park Citation2001) and social roles (Barden et al. Citation2004) can shape anti-Black implicit bias.

4 Sociologists have examined various forms of explicit racial attitudes.

5 Recent studies consider ideological attitudes and personality traits as moderators (Turner, Hodson, and Dhont Citation2020). See also Pettigrew (Citation1998, 77–79).

6 Another study finds that people’s implicit racial attitudes shift to attune to the explicit antiracist attitudes of others they like (Sinclair et al. Citation2005). While that research does not control for partisanship, the present discussion suggests that those findings may only apply to white Democrats.

7 An alternative possibility is that partisan differences in “subtyping” inform whether positive interactions with Black friends map onto weaker anti-Black implicit bias. That is, in order to resolve the contradiction between their comparatively negative views of African Americans and their (assumedly positive) experiences with individual Black friends, white Republicans may be more likely to subtype their Black friends (i.e. think of them as different from most African Americans). As a result, any positive associations that they form with those friends may not generalize to African Americans as a group. However, it is also possible that 1) associations with a subgroup do generalize to the broader category (see Lowery, Hardin, and Sinclair Citation2001, 845), and 2) that white Democrats also subtype their Black friends.

8 For an examination of “mere exposure” effects on implicit attitudes in the context of political advertising, see Ryan and Krupnikov Citation2021.

9 In both cases, YouGov drew subsets of participants from each of the social strata listed from the 2016 Current Population Survey (CPS) November supplement on white US-born respondents. Next, YouGov used the person weights on the CPS public use file to perform weighted sampling of CPS respondents for representative selection within the specified strata. YouGov then identified respondents from its own pool that matched those appearing in the stratified CPS sample according to the listed social characteristics. Finally, YouGov calculated probability weights for its own respondents by using logistic regression to predict propensity scores for how likely each would be to show up in the CPS sample.

10 The authors of one study showing no effect for friendship administered their measures for implicit bias and interracial friendship in randomized order and found no systematic order effects (Turner, Hewstone, and Voci Citation2007; but see also Nosek, Greenwald, and Banaji Citation2005, 176).

11 After completing both phases, participants received a debriefing form explaining that the survey and the categorization task were in fact part of the same study, and that the latter task was an Implicit Association Test used to measure implicit racial bias. The form included a brief description of implicit racial bias and a link to the Race IAT hosted by Harvard’s Project Implicit. Finally, the form reminded respondents that they were free to retract their responses and withdraw from the study; none did so.

12 A ratio greater than 1 reflects more frequent interaction with one’s Black friends than with one’s white friends, while a ratio of 1 indicates parity in how often respondents interact with friends of each race. A ratio less than 1 but greater than 0 reflects more frequent interaction with white than with Black friends. Respondents who never interact with their Black friends, or who have none, have a zero value for this variable.

13 There are no non-binary respondents in the sample.

14 Analyzing the 2017 data separately from the 2022 data yields similar results, as does using number of Black friends rather than one or more Black friends to operationalize friendships with African Americans in the 2022 data.

15 This estimate refers to 55 year-old men with a high school education or less who live outside the South.

References

- Aberson, Christopher. 2019. “Friendships with Blacks Relate to Lessened Implicit Preferences for Whites Over Blacks.” Collabra: Psychology 5 (1): 16. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.195.

- Aberson, Christopher L., Carle Shoemaker, and Christina Tomolillo. 2004. “Implicit Bias and Contact: The Role of Interethnic Friendships.” The Journal of Social Psychology 144 (3): 335–347. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.144.3.335-347.

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Barden, Jamie, William W. Maddux, Richard E. Petty, and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2004. “Contextual Moderation of Racial Bias: The Impact of Social Roles on Controlled and Automatically Activated Attitudes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.1.5.

- Blalock, Hubert. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority Group Relations. New York: Wiley.

- Burt, Ronald S. 1984. “Network Items and the General Social Survey.” Social Networks 6 (4): 293–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(84)90007-8.

- Carpenter, Thomas P., Ruth Pogacar, Chris Pullig, Michal Kouril, Stephen Aguilar, Jordan LaBouff, Naomi Isenberg, and Alek Chakroff. 2019. “Survey-Software Implicit Association Tests: A Methodological and Empirical Analysis.” Behavior Research Methods 51 (5): 2194–2208. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01293-3.

- Chin, Mark J., David M. Quinn, Tasminda K. Dhaliwal, and Virginia S. Lovison. 2020. “Bias in the Air: A Nationwide Exploration of Teachers’ Implicit Racial Attitudes, Aggregate Bias, and Student Outcomes.” Educational Researcher 49 (8): 566–578. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20937240.

- De Houwer, Jan, Sarah Thomas, and Frank Baeyens. 2001. “Association Learning of Likes and Dislikes: A Review of 25 Years of Research on Human Evaluative Conditioning.” Psychological Bulletin 127 (6): 853–869. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.853.

- el-Nawawy, Mohammed, and Mohamad Elmasry. 2021. “White Supremacy on CNN and Fox: Ac 360 and Hannity Coverage of the Charlottesville ‘Unite the Right’ Rally.” Journalism Practice 17 (5): 948–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1967187.

- Gawronski, Bertram, and Galen V. Bodenhausen. 2006. “Associative and Propositional Processes in Evaluation: An Integrative Review of Implicit and Explicit Attitude Change.” Psychological Bulletin 132 (5): 692–731. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.692.

- Graf, Sylvie, and Sabine Sczesny. 2019. “Intergroup Contact With Migrants Is Linked to Support for Migrants Through Attitudes, Especially in People Who Are Politically Right Wing.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 73: 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.09.001.

- Green, Alexander R., Dana R. Carney, Daniel J. Pallin, Long H. Ngo, Kristal L. Raymond, Lisa I. Iezzoni, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2007. “Implicit Bias among Physicians and its Prediction of Thrombolysis Decisions for Black and White Patients.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 22 (9): 1231–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5.

- Greenwald, Anthony G., and Linda Hamilton Krieger. 2006. “Implicit Bias: Scientific Foundations.” California Law Review 94 (4): 945–967. https://doi.org/10.2307/20439056.

- Greenwald, Anthony G., Brian A. Nosek, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2003. “Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: I. An Improved Scoring Algorithm.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 (2): 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197.

- Henry, P. G., and Curtis Hardin. 2006. “The Contact Hypothesis Revisited.” Psychological Science 17 (10): 862–868. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01795.x.

- Homola, Jonathan, and Margit Tavits. 2018. “Contact Reduces Immigration-Related Fears for Leftist but Not for Rightist Voters.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1789–1820. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017740590.

- Jacoby-Senghor, Drew S., Stacey Sinclair, and J. Nicole Shelton. 2016. “A Lesson in Bias: The Relationship Between Implicit Racial Bias and Performance in Pedagogical Contexts.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 63: 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.010.

- Jost, John T., Laurie Rudman, Irene V. Blair, Dana R. Carney, Nilanjana Dasgupta, Jack Glaser, and Chris Hardin. 2009. “The Existence of Implicit Bias is Beyond Reasonable Doubt: A Refutation of Ideological and Methodological Objections and Executive Summary of Ten Studies That No Manager Should Ignore.” Research in Organizational Behavior 29: 39–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.10.001.

- Karpinski, Andrew, and James L. Hilton. 2001. “Attitudes and the Implicit Association Test.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (5): 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.774.

- Kunda, Ziva. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480.

- Levin, Shana, Colette van Laar, and Jim Sidanius. 2003. “The Effects of Ingroup and Outgroup Friendships on Ethnic Attitudes in College: A Longitudinal Study.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 6 (1): 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001013.

- Livingston, Robert W., and Brian B. Drwecki. 2007. “Why Are Some Individuals Not Racially Biased? Susceptibility to Affective Conditioning Predicts Nonprejudice Toward Blacks.” Psychological Science 18 (9): 816–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01985.x.

- Lowery, Brian S., Curtis D. Hardin, and Stacey Sinclair. 2001. “Social Influence Effects on Automatic Racial Prejudice.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (5): 842–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.842.

- Maxwell, Angie, and Todd Shields. 2019. The Long Southern Strategy: How Chasing White Voters in the South Changed American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mitchell, Chris J., Nick E. Anderson, and Peter F. Lovibond. 2003. “Measuring Evaluative Conditioning Using the Implicit Association Test.” Learning and Motivation 34 (2): 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0023-9690(03)00003-1.

- Munn, Christopher W. 2018. “The One Friend Rule: Race and Social Capital in an Interracial Network.” Social Problems 65 (4): 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spx020.

- Nosek, Brian A., Anthony G. Greenwald, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2005. “Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: Ii. Method Variables and Construct Validity.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31 (2): 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271418.

- Nosek, Brian A., Frederick L. Smyth, Jeffrey J. Hansen, Thierry Devos, Nicole M. Lindler, Kate A. Ranganath, Colin Tucker Smith, et al. 2007. “Pervasiveness and Correlates of Implicit Attitudes and Stereotypes.” European Review of Social Psychology 18 (1): 36–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280701489053.

- Olson, Michael A., and Russell H. Fazio. 2006. “Reducing Automatically Activated Racial Prejudice Through Implicit Evaluative Conditioning.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 32 (4): 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205284004.

- Pearson-Merkowitz, Shanna, Alexandra Filindra, and Joshua J. Dyck. 2016. “When Partisans and Minorities Interact: Interpersonal Contact, Partisanship, and Public Opinion Preferences on Immigration Policy.” Social Science Quarterly 97 (2): 311–324. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26612319.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F. 1998. “Intergroup Contact Theory.” Annual Review of Psychology 49 (1): 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., Linda R. Tropp, Ulrich Wagner, and Oliver Christ. 2011. “Recent Advances in Intergroup Contact Theory.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 35 (3): 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001.

- Pew Research Center. 2015. “A Deep Dive Into Party Affiliation: Sharp Differences by Race, Gender, Generation, Education.” https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2015/04/07/a-deep-dive-into-party-affiliation/.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. “The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider.” https://www.people-press.org/2017/10/05/8-partisan-animosity-personal-politics-views- of-trump/8_02/.

- Phillips, Stephen T., and Robert C. Ziller. 1997. “Toward a Theory and Measure of the Nature of Nonprejudice.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (2): 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.420.

- Prestwich, Andrew, Jared B. Kenworthy, Michelle Wilson, and Natasha Kwan-Tat. 2008. “Differential Relations Between two Types of Contact and Implicit and Explicit Racial Attitudes.” British Journal of Social Psychology 47: 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466607X267470.

- Quillian, Lincoln. 2006. “New Approaches to Understanding Racial Prejudice and Discrimination.” Annual Review of Sociology 32 (1): 299–328. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29737741.

- Quillian, Lincoln. 2008. “Does Unconscious Racism Exist?” Social Psychology Quarterly 71 (1): 6–11. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20141814.

- Rachlinski, Jeffrey J., Sheri Lynn Johnson, Andrew J. Wistrich, and Chris Guthrie. 2009. “Does Unconscious Racial Bias Affect Trial Judges?” Notre Dame Law Review 84 (1): 1195–1246. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/tndl84&div=31&id=&page=.

- Rowatt, Wade C., and Lewis M. Franklin. 2004. “Research: Christian Orthodoxy, Religious Fundamentalism, and Right-Wing Authoritarianism as Predictors of Implicit Racial Prejudice.” International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 14 (2): 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr1402_4.

- Ryan, Timothy J., and Yanna Krupnikov. 2021. “Split Feelings: Understanding Implicit and Explicit Political Persuasion.” American Political Science Review 115 (4): 1424–1441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000538.

- Shook, Natalie J., and Russell H. Fazio. 2008. “Interracial Roommate Relationships.” Psychological Science 19 (7): 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02147.x.

- Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sinclair, Stacey, Brian S. Lowery, Curtis D. Hardin, and Anna Colangelo. 2005. “Social Tuning of Automatic Racial Attitudes: The Role of Affiliative Motivation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (4): 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.583.

- Tesler, Michael. 2013. “The Return of Old-Fashioned Racism to White Americans’ Partisan Preferences in the Early Obama Era.” The Journal of Politics 75 (1): 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000904.

- Tetlock, Philip E., and Gregory Mitchell. 2008. “Calibrating Prejudice in Milliseconds.” Social Psychology Quarterly 71 (1): 12–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20141815.

- Tetlock, Philip E., and Gregory Mitchell. 2009. “Implicit Bias and Accountability Systems: What Must Organizations do to Prevent Discrimination?” Research in Organizational Behavior 29: 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.10.002.

- Thomsen, Jens Peter Frølund, and Arzoo Rafiqi. 2019. “Intergroup Contact and its Right-Wing Ideological Constraint.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (15): 2739–2757. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1493915.

- Trepagnier, Barbara. 2001. “Deconstructing Categories: The Exposure of Silent Racism.” Symbolic Interaction 24 (2): 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2001.24.2.141.

- Turner, Rhiannon N., Miles Hewstone, and Alberto Voci. 2007. “Reducing Explicit and Implicit Outgroup Prejudice Via Direct and Extended Contact: The Mediating Role of Self-Disclosure and Intergroup Anxiety.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93 (3): 369–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.369.

- Turner, Rhiannon N., Gordon Hodson, and Kristof Dhont. 2020. “The Role of Individual Differences in Understanding and Enhancing Intergroup Contact.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 14 (6): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12533.

- Walther, Eva, Benjamin Nagengast, and Claudia Trasselli. 2005. “Evaluative Conditioning in Social Psychology: Facts and Speculations.” Cognition and Emotion 19 (2): 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000274.

- Wilcox, Jerry, and Wade Clark Roof. 1978. “Percent Black and Black-White Status Inequality: Southern Versus Northern Patterns.” Social Science Quarterly 59 (3): 421–434. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42860374.

- Wittenbrink, Bernd, Charles M. Judd, and Bernadette Park. 2001. “Spontaneous Prejudice in Context: Variability in Automatically Activated Attitudes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (5): 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.815.