ABSTRACT

This article reports selected findings from the EC Horizon 2020-funded CHIEF project, which examined young people’s understandings of cultural identity and heritage across nine countries. Drawing on observational work and interviews, the article explores how young people in England attending two social organisations with non-formal educational remits, perceive and attach meaning to cultural belonging and intercultural encounter. The two organisations were based in very different settings and engaged young people with different characteristics: the first being based in a highly diverse urban area, the second in a low diversity rural community. By focusing on synergies between young people’s perceptions and experiences, we contribute insights to a growing literature which is problematising the binary definition of the convivial urban against the exclusionary rural in studies of diversity and intercultural encounter.

Introduction

This article explores comparatively the ways in which young people attending social organisations with non-formal educational remits perceive and attach meaning to cultural belonging and intercultural encounter. It focuses on two youth organisations: one in a (super)diverse city and one in a rural area with low ethno-religious diversity. In doing so, it seeks to contribute new insights to a growing literature which is problematising the binary definition of the convivial urban against the exclusionary rural in studies of diversity and intercultural encounter, by demonstrating the synergies between these cases despite their apparent differences.

The article draws on data collected in 2018–19 in contribution to a work package within CHIEFFootnote1 – a comparative, mixed-methods project that worked across nine countriesFootnote2 to examine “issues and challenges faced by young people in Europe and beyond in the course of their cultural socialisation and in accessing diverse forms of cultural participation and environments for cross-cultural interactions’ (CORDIS Citation2022). Data were gathered in the West Midlands of England in two non-formal educational organisations: in a small religious charity that promotes interaction between young people from different ethnic and religious backgrounds in a diverse urban neighbourhood, and in a branch of a national organisation for young people in rural communities located in an area with low levels of ethno-religious diversity. The article compares how these young people articulated cultural belonging and cultural difference, and their experience of interactions across cultural difference.

The article proceeds with a discussion of existing literature on urban and rural (multi)culture. It then outlines the research methods and introduces the two settings, before exploring the meanings ascribed by the young people to culture, cultural identity, and diversity and drawing out synergies and differences across the cases, which are discussed in the conclusion.

(Multi)culture and difference in the city and the countryside

Ethnic and religious diversity is a core characteristic of English cities in the twenty-first century (Bennett, Cochrane, and Moghan Citation2017). At first characterised as multicultural – that is, comprised of a range of different cultural and ethnic groups – cities are increasingly framed as “superdiverse” (Vertovec Citation2015), with layers and varieties of migration alongside intersecting diversities of race, gender, class, and age.

The study of this increasingly complex urban diversity has come to be dominated by a “convivial turn” across social science and human geography (Jones et al. Citation2015; Wise and Velayutham Citation2009), exploring the ways in which people experience diversity in public and semi-public spaces “through everyday experiences and encounters’ (Amin Citation2002, 959). Policy-makers have viewed multiculturalism as in crisis, with particular concern surrounding the supposed non-integration of Muslim communities (Lentin and Titley Citation2012; Ossewaarde Citation2014), whereas in contrast, this literature treats diversity as a commonplace and unremarkable aspect of everyday life (Wessendorf Citation2014), with such everyday multiculture discussed in settings including cafes (Jones et al. Citation2015), parks (Neal et al. Citation2015; Wilson Citation2013), colleges (Bennett, Cochrane, and Moghan Citation2017), housing estates (Gidley Citation2013), workplaces (Høy-Peterson and Woodward Citation2018), public transport (Wilson Citation2011), libraries (Robinson Citation2020) and in marketplaces (Rhys-Taylor Citation2013).

Rural England has been viewed as the monocultural foil to the diverse city, with the unchanging “rural idyll” occupying an important place in the national imaginary (Brooks Citation2020; Neal and Agyeman Citation2006). Yet this idealised vision masks lived experiences of rural life, which include “socio-economic tensions’ and “socio-cultural exclusions’ (Neal and Walters Citation2008, 280; see also Mackrell and Pemberton Citation2018; Neal et al. Citation2021; Neal and Agyeman Citation2006) and perpetuates the invisibility of the experiences of more diverse rural populations (Moore Citation2021; Panelli et al. Citation2009; Tonkiss Citation2013). These tensions and exclusions are explored in scholarship examining the social consequences of assemblages of the rural as a sanitised “white monocultural national space” (Neal et al. Citation2021, 177), which focuses on “extensive levels of racism and discrimination, the denial and invisibalisation of rural black, Asian and ethnic minority populations as well as a mobilisation of the rural as a source of anti-multicultural backlash” (177) – the latter exemplified by the hostility to rural migrant workers in discourses around Brexit (Brooks Citation2020; Neal et al. Citation2021).

A problematization of an “urban-as-multicultural/rural-as-monocultural dialectic” (Askins Citation2009, 366) also highlights shortcomings of the conviviality literature, which can overlook urban divisions – particularly those rooted in racism (Aptekar Citation2019). This tension has been termed the “metropolitan paradox”, whereby “complex and exhilarating forms of transcultural production exist simultaneously with the most extreme forms of violence and racism” (Back Citation1996, 7 see also Berg, Gidley, and Krausova Citation2019; Berg and Sigona Citation2013; Harris Citation2018). The convivial lens rightly challenges political discourses that situate diversity as a problem to be solved through “social cohesion” measures to tackle “self-segregation” while simultaneously overlooking the structural issues impacting minoritised communities (O’Toole Citation2021; Phillips Citation2006). But accounts of urban conviviality can themselves risk sidelining structural inequalities through overly celebratory perspectives, or as Neal et al. (Citation2019, 70) caution, via a drift from a “radical emphasis on uneasy and fragmented negotiations between connected others towards more familiar integrationist values in which difference is sanitised around contact and the hierarchies of cultural difference are flattened out or obscured.”

These tensions are apparent in the sub-body of urban conviviality literature dealing with the experiences of young people. Scholars such as Meissner (Citation2020) have characterised urban young people in post-migration societies as “growing up with difference … [as] diversity natives’. But it does not follow that conviviality is experienced unproblematically by urban young people. Indeed, scholars such as Back (Citation1996), Harris (Citation2013) and Hewitt (Citation1986) have recognised “that young people are associated with inter-ethnic ‘crossings’ and with cultural openness, but also with cultural defensiveness” (Bennett, Cochrane, and Moghan Citation2017, 2307), and that “conviviality’s everyday instantiation always sits adjacent to processes of ethnically construed ‘conflict’” (Valluvan Citation2016, 205) and “distanciation” (Harris Citation2014). Empirical illustrations include the “drift”, observed in London's Hackney by Wessendorf (Citation2014, 138–142), from mixed friendships towards groupings along racial and class lines as young people progress through secondary school, with supposed incompatibilities of “taste” and “lifestyle” evoked as neutralised code for race/ethnicity, while extreme economic disadvantage and postcode violence are additional challenges to navigate in James’ (Citation2015) study in Newham. Driezan, Clycq, and Verschraegen’s (Citation2023) study in Antwerp, and Huttunen’s and Juntunen’s (Citation2020) in a diverse suburb of Turku observe that although “new and inclusive forms of identification that cut across ethnic and religious divisions are emerging” (Huttunen and Juntunen Citation2020, 4136) among young people who conceptualise diversity as “commonplace” (Driezan, Clycq, and Verschraegen Citation2023, 11), nonetheless boundary-making occurs among both white majorities and minority ethnic and migrant young people, and racism persists (12–14).

In the last decade or so, the “metrocentricity” of youth studies (Farrugia Citation2014, 293) has been challenged by scholarship engaged in the experiences of rural young people. This work has included attention to rural and small-town young people’s experiences of socio-economic transitions and inequalities (298), such as, in various Global North contexts, the centrality of (often young) migrant workers to rural economies and trends for outmigration of locally born youth (Butler Citation2020, 1178–1179). Alongside this, sociologists and human geographers have challenged assemblages of the rural as “‘white’ and/or ‘raceless’” (1180) and subsequent urban bias in attention to diversity and conviviality, through a focus on rural interculturality in various national contexts (for example Burdsey Citation2013; Moore Citation2021; Neal Citation2002; Neal and Walters Citation2008; Radford Citation2016; Woods Citation2018). This literature identifies conviviality, but also racism, “othering” of ethnic minorities and migrants in rural spaces and imaginaries, and conditionalities attached to the tolerance of ethnic or national outsiders (for example Chakraborti and Garland Citation2011; Lumsden, Goode, and Black Citation2019; Moore Citation2021; Panelli et al. Citation2009; Spiliopoulos, Cuban, and Broadhurst Citation2021; Tyler Citation2003). While scholarship engaging specifically with the navigation of diversity by rural young people remains limited, what exists suggests that tensions identified in the urban youth literature are too reflected in rural settings, with “multicultural success stories” around “retention and engagement of diverse young people in rural communities” existing alongside “rural racisms and tensions” – particularly in schools (Butler Citation2020, 1179–1180; see also Bhopal Citation2014; Colvin Citation2017; Odenbring and Johansson Citation2019).

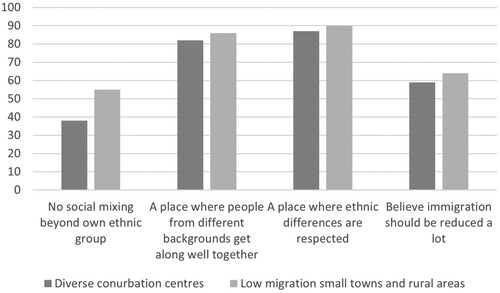

These synergies between the urban and rural are explored in Lymperopoulou’s (Citation2020) quantitative research into intercultural attitudes. This captures important similarities across a rural-urban spectrum, as highlighted in , which shows differences in intercultural attitudes between populations of “diverse conurbation centres” and “low migration small towns and rural areas”. While there is difference in the extent people mix beyond their own ethnic group, which we would expect given the different demographic profile of these populations, there is greater similarity across attitudinal indicators.

Figure 1. Comparison of intercultural attitudes in diverse urban and low-diversity rural areas of the UK (adapted from Lymperopoulou Citation2020).

The remainder of this article seeks to develop understanding of these synergies through a qualitative comparative account of young people’s narrations of cultural belonging and intercultural encounter in a diverse city and a low migration rural area; presenting new insights which challenge the multicultural-urban/monocultural-rural dialectic in local contexts of young people’s interactions in youth organisations.

The two settings

The CHIEF project worked with young people in settings where cultural transmission and development of cultural literacy occur – within the formal educational setting of schools, through to sites of informal learning such as family environments and peer networks – with the work package within which this article’s research took place focusing on the “middle ground” of non-formal education: “tak[ing] place outside formal learning environments but within some kind of organisational framework” (Council of Europe Citation2020). In the contemporary British context, non-formal youth provision is delivered by the public and voluntary sectors, with religious organisations a major provider (Thompson Citation2019, 166).Footnote3 In selecting settings, we also considered their geographic locations in accordance with the comparative sampling protocol agreed across CHIEF, whereby local geographic sites within the nine countries were selected to capture variety across the urban and rural, demographic and economic characteristics, and local support for nativist or nationalist politics (CORDIS Citation2022). The measurement employed for the “nativist/nationalist” category across the nine countries was dependent on domestic political contexts, and in the English research, support for the UK leaving the EU as expressed through local results in the June 2016 EU membership referendum was the proxy measure.Footnote4 From this sampling framework we identified two settings: one in an ethno-religiously diverse and economically disadvantaged urban area which voted strongly to remain in the EU (Setting 1) and the other in a low-diversity, more affluent rural area that strongly supported “leave” (Setting 2). These locales’ characteristics as diverse and urban, and non-diverse and rural are the salient backdrop to the analysis in this article, although their economic and political characteristics are also relevant at points.

Setting 1 is a Christian charity whose work encourages friendship between young people of different faiths. The group runs activities during school holidays where young people meet to discuss their faiths and enjoy social activities, and is mainly attended by young people who self-define as Christian or Muslim. The group is based in a major West Midlands city (population >1 million) within an inner-city neighbourhood which is among the 10 per cent most deprived in England (DCLG Citation2015). The area is ethnically and religiously diverse, with large British South Asian and British Somali populations who are predominantly Muslim (ONS Citation2012). The local constituency voted 66 per cent to “remain” in the European Union in the 2016 referendum (House of Commons Library Citation2017). We participated in school holiday programmes, observing some activities and joining in with others,Footnote5 including arts and crafts, street dance, cookery, team-building challenges, and excursions. Structured discussions, where young people talked about their faith, were another aspect of the group’s activity, as per the organisation’s goal of “creat[ing] safe spaces for honest and respectful conversations” (organisational materials, on file with authors).

Setting 2 is a Midlands-based branch of a nationwide educational and social organisation for young people who live in rural areas and/or are connected to the agricultural sector. The branch’s local area has a small market town hub (population <10,000), but an otherwise dispersed rural population. The population is mainly white British with very limited ethnic or religious diversity (ONS Citation2012), and while there are pockets of deprivation, it is generally above-averagely affluent (DCLG Citation2015). The local constituency voted 68 per cent in favour of “leave” in the EU membership referendum (House of Commons Library Citation2017). We attended branch meetings held in a church hall, which often included an educational talk about agriculture/agribusiness. We also attended county-wide competition days, and preparation for these formed another important strand of activity. The competitions took place on a farm and entailed contests in agricultural skills such as sheep-shearing, as well as disciplines termed “house crafts” such as floristry, and artistic endeavours including painting and scrapbooking. The most prized title was the tug of war between county branches which closed the competition, and the day ended with a party featuring a DJ and well-stocked bar.

Research design

The data collection combined observations recorded in fieldnotes and photographs, and semi-structured interviews with young people and older adult staff or volunteers.Footnote6 The research was explained to group members during initial visits, and information sheets were made available to all attendees. Interview participants were a self-selecting sample, with a second information sheet and consent form distributed to the interview cohort. As such the research followed the principle of informed consent, with consent additionally sought from parents/guardians of participants aged under sixteen. The research followed the ethical guidelines of the British Sociological Association (Citation2017) and was reviewed and approved by Aston University’s School of Languages and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee.

In Setting 1, the young people we spoke with during the spring half term and Easter holidays identified as British South Asian, East African, Black or Caribbean British, and white British. This changed during the summer, when most of the participating young people identified themselves as Muslim and British-Bangladeshi or British-Pakistani, as some of the other young people we had met earlier in the year were away on a residential trip run by another local organisation. Given that most interviews were conducted during the summer, this is reflected in the demographic breakdown of interviewees which does not fully reflect the wider group of young people engaging in activities. We interviewed eight young people and three adult employees during breaks in activities or follow-up visits to the group’s venue. Of the young people, four were aged 14–16, lived locally and attended local schools. This younger cohort comprised one girl and three boys, and one identified themselves as British-Bengali and the others as British-Pakistani. All were born in the UK and identified as Muslims. The remaining four young interviewees were aged 19–23 and were students at one of the city’s universities (as well as living in the city with their families) who were volunteering during their summer holiday. This older cohort of young people were all women. Three identified as British-Bengali while one had moved to the UK from Somalia as a child, and all identified as Muslim. As volunteers they had responsibility for planning activities but also joined with the younger cohort in activities led by older staff, and as such occupied a dual position as participant and facilitator. The three staff interviewees were women and held management and youth work positions. Two identified as Black British and one as white British, and all identified as Christian.

In Setting 2, we collected eight interviews, while competition days also provided opportunities for shorter conversations with other young members of the organisation and parents. The structure of this organisation meant there was not a clear differentiation between young people and adults, as there are no paid staff at branch level and older young people take on leadership roles. As such, all but one of the interviewees fell within the 14–25 age bracket; the exception being the father of one of the young participants who is a former member of the branch and now involved as a volunteer. Of the seven younger interviewees, four were women and three were men. Reflecting the area’s low ethnic diversity, all identified as white British. Most did not identify as religious, although some expressed nominal identification with the Church of England and attended services during Christmas and Harvest. Most interviews took place in the church hall before or after the group’s meetings, while two took place at members’ homes.

Interviews in both settings focused on young people’s understandings of culture, belonging and cultural differences, which included speaking with young people about their own cultural practices and their significance in their lives, and their exposure to cultural “others”. No pre-determined idea of “culture” was imposed upon participants, who were instead able to express their own interpretations of this concept. Participants were asked what they understood culture to be and how they would describe their culture, with young people talking about this in terms of ethnicity or heritage (including family migration histories), religion, family and/or community traditions, their relationship to place and communities, their values, or a combination of these things. If young people struggled with this, they were asked to tell us about things they did in their lives because of their culture, with this proving effective for opening discussion of the concept.

In a project concerned with culture and identities it was important to think about positionality in the field, which has often been considered in terms of advantages/disadvantages of researching as an insider or outsider to a community (Kerstetter Citation2012). As two white British researchers we were more obviously “outsiders” in Setting 1 when spending time with young people from minority ethnic backgrounds. Our lack of religious belief also differentiated us from both the young people and adults in the setting, who were all Muslims or Christians. But in Setting 2, while our white ethnicity gave us more in common with the local population, we were identified as urban outsiders by participants, some of whom gently mocked our supposed urban sensibilities or suggested we may find it hard to understand the mores of their community.Footnote7 Research involving children and adolescents also necessitates consideration of the power asymmetries of an adult-researcher and child-participant (Grover Citation2004). While our participants were older children or young adults, we remained mindful of this dynamic. Interviewing participants in “their space” of the group settings or their home, treating them as experts in their culture and cultural practices, and answering their questions about our own lives and identities helped to redress this.

Following transcription and anonymisation, we coded interviews and fieldnotes using NVivo. We followed an inductive approach, and each worked with transcripts from each setting including our own interviews and interviews conducted by the other researcher, with regular conversations to refine codes. We coded our own observation notes, which enabled a balance between critical distance, and the importance of contextual familiarity with “the field” (Hayes and Jones Citation2012, 2).

Belonging and becoming in the city and the countryside

In this section we present the findings of this research. We first consider the ways in which young people in the two settings understood cultural belonging, before analysing their views on, and experiences of, cultural difference.

Cultural belonging

For young people in both settings, cultural belonging was understood in terms of heritage, family, and “tradition”. While what “tradition” looked like was framed differently, similarities were apparent around cultural conformity and accepted behaviours and values. In Setting 1, young people tied their understandings of cultural belonging to practices related to family heritage and migration histories, and Islamic teachings. For example, TahniFootnote8 (female British-Bangladeshi, Muslim YP) described culture as “ … like ethnicity, and like where your background is and where your parents and grandparents are from, and, like, what traditions that you take part in because of your ethnicity and because of your faith”. Young people in this setting also commented on the importance of the continuation of practices linked to family heritage in the UK diaspora, as Rumi (female, British-Bangladeshi Muslim YP) described: “I wouldn’t want to not wear it [Bengali dress], like, at home or weddings … it’s a part of who I am, and I don’t want to change that”. In Setting 2, although young people did not have recent family histories of migration and diaspora, cultural continuity was also key. As Harry (male white British YP) described, “ … the culture … it’s a straight line, there’s not much divergent from it, … [w]e do things as the organisation did them years ago”. Despite the ownership that the group’s organisational structure granted young people, it was clear that most activities represented continuation of tradition. We asked why the group continued to engage in, for example, competitive floristry, when it was clear most did not enjoy it, with Olivia (female white British YP) replying, “it’s tradition and something that has been taken seriously for years”. Alongside these understandings, and in ways running through all of them, was an interpretation of cultural belonging as intrinsically tied to place. Place, in this case, meant the rural landscape and the community of people who laboured within it – as George (male white British YP) noted, “I love the land” – while in Setting 1, translocal belonging to places of family origin and the diaspora was expressed.

For young people in both settings culture was also closely tied to “values”, and both used similar words to describe values attached to “their” culture – with “respect” being key for both, especially as this related to interactions with older family and community members. For example, part of the experience of participating in the rural social life offered by Setting 2 was getting drunk. As Abby (female white British YP) described “ … we all go to [parties] and they’re crazy. They’re just cheap drinks and everyone gets really drunk”. But while binge drinking (including underage drinking) was normalised as part of rural social life,Footnote9 participants expressed quite different views towards other drugs, with drug-taking “waster(s)” (Olivia – female white British YP) contrasted with the values of a close-knit community where elders were respected, and everyone could reply upon one another. A similar discourse around respect for elders and the wider community was found among the British South Asian young people in Setting 1, although here it was attributed to religious values within Islam, as well as cultural expectations:

Part of our culture is feeling like we’ve always been taught to take care of your parents, and that links with religion as well. Take care of your parents and [the] elderly and get along with your family … I feel like, in our culture, it’s a really big thing. (Amal – female, British-Bangladeshi Muslim YP)

Cultural difference

Our findings show three key themes across the settings related to how young people understood and experienced cultural difference. Firstly, young people articulated cultural difference through identification of a “significant other” which is central to the relational construction of group consciousness (Triandafyllidou Citation1998, 603). In the rural context of Setting 2, the “other” to which the group most commonly referred was the urban dweller, with Abby, for example, describing her culture as “not townie”,Footnote10 and both the aforementioned framing of “rural community values” which reject drug-taking (though not alcohol) in contrast to imagined urban deviance, as well as dress, playing a central role in distinguishing young people from urban “others”. Abby commented “we don’t dress like town people”, while at a competition day, a group member’s mother exclaimed “this is how teens use knives in the countryside” while we watched young people exhibit their butchery skills on chicken carcasses – contrasting this with media reporting of knife crime in cities (observation 3). A tendency to construct identity against an “outside” urban world, either through “valorisation” of local rural identity or a focus on perceived disadvantage or marginalisation vis a vis urban counterparts is seen in studies of rural youth in a range of global contexts (Farrugia, Smyth, and Harrison Citation2014, 1038), and in our study, was also apparent during a talk from a former member of the group who showed a photo slideshow of a trip around Southeast Asia. The speaker stated that cities such as Bangkok were “horrible”, but they had felt an affinity with fellow farmers they met in the countryside, with rural identity, here, transgressing boundaries of nationality, ethnicity and language (observation 1).

A similar focus on values was present in group members’ views on immigration. They tended to view immigrants positively where they were seen to contribute to the local agricultural economy, with George, for example, describing East Europeans employed locally in agriculture as having “made their money fair and square, I don’t have a problem with those sorts of people coming in”. This contrasted with views about other migrants who were imagined to “ … come over here for an easier life” (Emma – female white British YP). While everyone we met in this setting was white British, we were told by the young people that anyone, of any ethnicity or nationality, who came to a meeting would be welcome if an established group member “vouched” for them. While this was never tested in practice, rhetorically at least, the tie to the local and its rural values is again positioned as the central factor distinguishing “us” from “them”, and as such, a construction was presented of the “good” migrant who earns acceptance across difference – an observation in common with Moore’s (Citation2021) and Spiliopoulos, Cuban, and Broadhurst’s (Citation2021) findings on the conditionalities of labour migrants’ acceptance in English rural areas, and Neal and Walters’s (Citation2008, 292–293) work on the importance of lineage and linkages in membership of rural community organisations.

While the young people in Setting 2 viewed themselves as homogeneous, in Setting 1 differences within the group were apparent as the organisation’s focus on intercultural encounter encouraged members to reflect on their similarities and differences from ethno-religious “others” within the setting itself, and as such cultural difference was once again positioned in relation to the “other” against whom the self could be defined. The possibility of building friendships with young people of different backgrounds was an attraction of the group for participants, and the organisation’s goal of encouraging respectful dialogue between young people of different faiths was situated by both young people and adults as a remedy to societal challenges such as hate crime or radicalisation.Footnote11 Kate (female, white British Christian adult staff member) felt the group’s activities developed young people’s resilience to harmful influences – “young people are drawn into a gang or some form of radicalisation because they’re not confident enough to say “actually, I don’t feel comfortable with this”” – and that the encouragement of honest and challenging conversations about faith gave young people “confidence [to be] their authentic self”.

Challenging negative stereotypes of the “other” was a key objective of the group’s work, and the question of “othering” held an additional dimension for young Muslim participants, who told us they had experienced Islamophobia in their everyday lives. This points to a second key theme – the experience of cultural difference. The young people in Setting 1 were keenly aware of political and media discourse normalising anti-Muslim prejudice. Boris Johnson’s comment that veiled Muslim women resemble “letterboxes” was cited alongside Donald Trump’s “Muslim travel ban”, and opportunities for intercultural dialogue were posited as an antidote to the populist Right: “I feel like everyone should learn about each other, each other’s faith and culture and religion, I think it’s important, so you can stop all this Trump stuff” (Amal).

These anxieties were apparent in the young people’s differing views towards Brexit between the settings. Few had been old enough to vote in the 2016 referendum, but their views reflected those of the majority in their local area, with the rural young people in Setting 2 tending to favour Brexit, while the young people in Setting 1 were uniformly opposed: “[it’s] like a broken chair that you can’t fix, but you have to keep sitting on it” (Tariq – male British-Pakistani Muslim YP). Their opposition did not indicate attachment to the European project but rather concerns about negative impacts on their future economic prospects, as well as the anti-immigration and exclusionary nationalistic sentiment of the “leave” campaign which they perceived as threatening their safety and national belonging. As Alia (female Somali Muslim YP) reflected:

I think that Brexit is quite … I’m going to use the word ‘shameful’. It’s quite sad … It kind of brings fear, sometimes, into how will the future be if that is the path that has been decided on … It definitely will [impact me] because I am [air quotes] ‘the other’. I am the people that come to England to take stuff, get their jobs, get their education … It’s quite scary. It just makes me think about what the next generations will be like and the future of England, and maybe the hate that would burst from all of this.

However, the final theme within our discussion – friendship – shows that, despite their different contexts, young people’s experiences of intercultural encounter can often be quite similar. As outlined earlier, the opportunity Setting 1 offered to expand friendship networks beyond young people’s own ethno-religious community was posited as particularly important for addressing issues of “othering” and cultural tensions in the diverse city, particularly as young people felt they had limited opportunities to engage in meaningful interactions with those of different faiths and ethnicities in their local neighbourhoods and in school; despite their city’s apparent (super)diversity. This challenges assumptions around the frequency and nature of encounter across difference in the (super)diverse city, as young people told us that outside the setting, they interacted with young people from similar ethnic and religious backgrounds to their own.

Sturgis et al. (Citation2014, 1290) argue: “It is entirely possible to live in a neighbourhood containing multiple ethnicities, without ever having any meaningful social contact with an individual from an ethnic out-group”, and this was certainly the perception of young people in Setting 1 when discussing their everyday encounters and networks. Their experience of homogenous friendship groups was not markedly different to that of their white British peers growing up in the much less diverse location of Setting 2, who perceived their own social networks as entirely homogenous. Indeed, within Setting 1 itself, while all agreed there was inherent value in promoting dialogue and friendship across difference, there was varying opinion as to how successful this was. From the researchers’ perspectives, indirect and organic activities appeared more effective than planned interventions designed to stimulate intercultural dialogue. Organic communication, therefore, was enabled by the setting rather than an outcome of its planned activity. For example, in one session, young people created mood boards as part of a planned activity and worked in almost complete silence. However, the atmosphere changed when the soundtrack of The Greatest Showman played in the background: “Young people started to talk about seeing the film or knowing the music, and some of them danced. It was the first time they opened-up to each other beyond the distinct groups that they had put themselves in” (notes from observation 4). Adult facilitators acknowledged the limitations of direct interventions. As Kate explained with reference to the planned dialogue sessions: “We feel that their answers are a little mechanical and they’re just saying what they think they should say … that’s why we’re encouraging more of them coming in, just chilling out here and having the different types of conversations”.

In both settings, some of the young people we met were attending or had recently finished university. As summarised by Brooks (Citation2019, 84), there are competing perspectives on the potential of universities as spaces of intercultural encounter. Like Amin’s (Citation2002, 970) notion of “banal transgression”, universities and other educational sites have been characterised as “micropublics” that necessitate what Back and Sinha (Citation2016, 524) term the “prosaic negotiation of difference”, while Harris (Citation2013, 58) argues they are “neutral and destabilising zones where encounter is required, and difference negotiated through shared tasks”. There was alignment to this position in the experience of Jack (male white British YP) in Setting 2, who had attended university in a large city before returning to the rural community to work in agribusiness: “I grew up in a traditional farming family … Then I lived in the middle of the city, went to a university that’s got a lot of different cultures … My childhood culture would be different to my culture at uni”. Jack’s experience was uncommon, as most of the older young people had attended agricultural colleges in rural areas and so were less likely to have been exposed to this difference. Yet for those who had been to urban universities, the experience of being among a diverse group of peers appeared to have shifted their perspective, and indeed the increasing numbers of young people attending university was viewed by local adults as consequential for the setting’s future. John (male, white British, adult volunteer), explained that the group had shrunk, because the “ … idea that traditionally the sons and daughters would stay on the farm” was under threat: “ … university is disrupting that, they don’t come back, they have a bigger view of the world”.

A contrasting perspective on the significance of the university experience is forwarded by Andersson, Sadgrove, and Valentine (Citation2012, 501), who argue that universities offer limited opportunities for intercultural encounter, as students “self-segregate” within diverse student bodies. This was reflected in the narrative of the university students interviewed in Setting 1, whose expectations of university as a space of intercultural encounter had not been met. As Alia reported: “There’s people from all over, from different walks of life, but then we still manage to keep in our own identical bubble”; Amal observed: “when we’re sitting in lectures, we’re all sitting in groups of our own religions or culture”; while Rumi, who was unique among the young people in Setting 1 in having grown up and attended school in a majority-white neighbourhood of the city, reflected that university was the first time that she had a group of friends with similar backgrounds to herself: “I’ve never had a Bengali friend and now I have a group of friends who are Bengali! It’s so weird because I imagined university to be, like, mixed”. As such, despite the demographic differences of their surroundings, the young people in both settings experienced limited intercultural encounters, and while going to university could give rise to new encounters and friendships across difference, this was not automatically the case.

Conclusions

The two settings examined in this research look markedly different “on paper”: on the one hand, a group focused on intercultural dialogue, attracting young participants from different ethnic and religious backgrounds in a diverse neighbourhood of a large city, and on the other, a club for young people in a rural community with an ethnically homogenous membership and a focus on the continuation of traditional rural life. Yet, despite these differences, commonalities exist in these young people’s understandings and experiences.

For both groups of young people, cultural belonging was understood as comprising the continuity of tradition, and family and community values. While these demographically different young people framed their values in different terms, the values they expressed were similar. This challenges the direction of youth policy which has sought to problematise young people from ethnic minority groups as needing to be educated into British values. On the contrary, it highlights that the othering of young people from ethnic minority backgrounds is a distraction from the common ground to be found between young people with varying demographic characteristics growing up in very different contexts.

The assumption that young people growing up in (super)diverse urban areas have more ready opportunities to encounter cultural difference in a meaningful way is also challenged; with the urban young people in Setting 1 feeling that the group offered them a unique opportunity to interact with those of different faiths and ethnicities, given that their outside networks did not fulfil this function. These findings point to the limited utility of conviviality as a concept in understanding young people’s intercultural encounters. Our research showed a lack of meaningful encounters with cultural difference for young people in urban areas just as much as in rural areas. Young people did not necessarily experience intercultural encounter in particularly positive or negative ways – they just did not experience it to a substantial extent in either case.

Even in (super)diverse settings where “fleeting” encounters across difference may naturally take place, this does not necessarily lead to meaningful encounters, meaning that spaces may still need to be created to allow this to occur in a more deliberate fashion if desired by young people. In particular, spaces where “banal transgression” (Amin Citation2002) occur seem to offer greater opportunities for the effective interaction and dialogue witnessed in the fieldwork than self-consciously intercultural interventions. As such, establishing and protecting space for young people is crucial, particularly in the context of austerity’s threat to youth provision and the precarity of groups reliant on charitable grant funding. This is observed in the activities of Setting 1, but also in the rural Setting 2, where a paucity of spaces where young people can meet and socialise (especially those who are too young to visit pubs) awards Setting 2 a privileged status as the only social outlet for young people, with potential issues around the inclusion a broader constituency of young people in the local area.

There were, however, differences in how the young people in each setting understood and valued intercultural encounter. While for young people in Setting 2, encounters with the “other” were embraced so long as that “other” was positioned as an “insider” to the community, in Setting 1 many of the young people understood themselves to have been positioned as “other”, particularly in the context of racist political rhetoric and anti-migrant sentiment associated with Brexit. As such, “intercultural positionality” is a key factor in understanding these young people’s experiences and is potentially more relevant than their local exposure to diversity and cultural difference.

Having explored comparatively the ways in which young people living in these divergent settings encounter, perceive and attach meaning to cultural belonging and cultural encounter, the article has contributed new insights to literature which seeks to look beyond the binary definition of the convivial urban against the exclusionary rural. The similarities across these cases, as well as the complex ways in which young people’s intercultural positionality impacts on their experience of cultural difference, supports the shift away from the urban/rural divide in the study of culture, identity and belonging.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for this journal, and colleagues at the University of Gloucestershire and Aston University who provided helpful comments on earlier versions. We are also grateful to the young people and staff in both settings for taking part in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Cultural Heritage and Identities of Europe’s Future. Funded by EC Horizon 2020: Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies (CORDIS Citation2022).

2 Croatia, England, Germany, Georgia, India, Latvia, Slovakia, Spain (Catalonia) and Turkey.

3 Spending on youth services within UK local authorities averaged a 69% decline between 2010 and 2019 (YMCA Citation2019) due to the public sector funding cuts of the austerity programme, increasing the need for third sector and religious organisations to attempt to “fill” this provision gap.

4 The authors recognise that voters had varied motivations for voting “leave”, but are convinced of the legitimacy of this measure by the body of studies which identify nativist and ethno-nationalist messaging in the “leave” campaigns and ethno-nationalist or racist/xenophobic views as key motivations for the leave vote (Carreras, Irepoglu Carerreras, and Bowler Citation2019; Iakhnis et al. Citation2018; Tudor Citation2023; Virdee and McGeever Citation2018), including perceptions of migration and ethnic diversity as “symbolic” and “realistic” “threats” (Macdougall, Feddes, and Doosje Citation2020).

5 We took our lead from staff, who joined in with some activities but let young people get on with others by themselves.

6 Within the CHIEF project, young people were defined as aged 14–25.

7 Jones was raised in the countryside, but as she was not brought up on a farm and has lived in urban areas for the last two decades, this did not provide “insider” currency with the participants.

8 Pseudonyms are used throughout.

9 See also Markham and Bosworth (Citation2016) on the centrality of the pub to rural social life, and Neal and Walters (Citation2007) on underage drinking (along with illegal driving and gun use) within their discussion of the rural as a site of “unregulated” or “anti-orderly” behaviours – a “less valorised cultural narrative” which nonetheless co-exists in their young participants” narratives with more celebrated notions of rural safety, peace and neighbourliness.

10 Rural slang for urban populations.

11 In these ways, the group’s work mirrors the alignment of youth work to a wider citizenship education agenda (Fyfe Citation2010, 69) which also views youth services as intervention vehicles for young people “at risk”. In diverse urban areas, this has included risks associated by policymakers with “segregated communities” – particularly British Muslim communities (as per the 2016 Casey Review and the earlier Cantle Report) – and the counter-extremism programme, “Prevent”, places legal obligations on youth work practitioners to refer young people who they consider at risk of radicalisation (Thomas Citation2016).

References

- Amin, A. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 34: 959–980. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3537.

- Andersson, J., J. Sadgrove, and J. Valentine. 2012. “Consuming Campus: Geographies of Encounter at a British University.” Social & Cultural Geography 13 (5): 501–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2012.700725.

- Aptekar, S. 2019. “The Unbearable Lightness of the Cosmopolitan Canopy: Accomplishment of Diversity at an Urban Farmers Market.” City & Community 18 (1): 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12371.

- Askins, K. 2009. “Crossing Divides: Ethnicity and Rurality.” Journal of Rural Studies 25 (4): 365–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.05.009.

- Back, L. 1996. New Ethnicities and Urban Culture: Racisms and Multiculture in Young Lives. London: Routledge.

- Back, L., and S. Sinha. 2016. “Multicultural Conviviality in the Midst of Racism’s Ruins.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2016.1211625.

- Bennett, K., A. Cochrane, and G. Moghan. 2017. “Negotiating the Educational Spaces of Urban Multiculture: Skills, Competencies and College Life.” Urban Studies 54 (10), https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016650325.

- Berg, M. L., B. Gidley, and A. Krausova. 2019. “Welfare, Micropublics and Inequality: Urban Super-diversity in a Time of Austerity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (15): 2723–2742. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2018.1557728.

- Berg, M. L., and N. Sigona. 2013. “Ethnography, Diversity and Urban Space.” Identities 20 (4): 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2013.822382.

- Berggren, J., A. Torpsten, and U. J. Berggren. 2021. “Education is My Passport: Experiences of Institutional Obstacles among Immigrant Youth in the Swedish Upper Secondary Educational system.” Journal of Youth Studies 24 (3): 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1728239.

- Bhopal, K. 2014. “Race, Rurality and Representation: Black and Minority Ethnic Mothers’ Experiences of Their Children’s Education in Rural Primary Schools in England, UK.” Gender and Education 26 (5): 490–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.935301.

- British Sociological Association. 2017. Guidelines on Ethical Research. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.britsoc.co.uk/ethics.

- Brooks, R. 2019. “Representations of East Asian Students in the UK Media.” In Asian Migration and Education Cultures in the Anglosphere, edited by M. Watkins, C. Ho, and R. Butler, 81–95. London: Routledge.

- Brooks, S. 2020. “Brexit and the Politics of the Rural.” Sociologia Ruralis 60 (4): 790–809. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12281.

- Burdsey, D. 2013. “‘The Foreignness is Still Quite Visible in This Town’: Multiculture, Marginality and Prejudice at the English Seaside.” Patterns of Prejudice 47 (2): 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2013.773134.

- Butler, R. 2020. “Young People’s Rural Multicultures: Researching Social Relationships among Youth in Rural Contexts.” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (9): 1178–1194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1657564.

- Carreras, M., Y. Irepoglu Carerreras, and S. Bowler. 2019. “Long-term Economic Distress, Cultural Backlash, and Support for Brexit.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (9): 1396–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830714.

- Chakraborti, N., and J. Garland, eds. 2011. Rural Racism. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Colvin, N. 2017. “‘Really Really Different Different’: Rurality, Regional Schools and Refugees.” Race Ethnicity and Education 20 (2): 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2015.1110302.

- CORDIS. 2022. Cultural Heritage and Identities of Europe’s Future. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/770464.

- Council of Europe. 2020. Formal, Non-Formal and Informal Learning. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://www.coe.int/en/web/lang-migrants/formal-non-formal-and-informal-learning#:~:text=Non%2Dformal%20learning%20takes%20place,the%20result%20of%20intentional%20effort.

- Crawford, C. 2017. “Promoting ‘Fundamental British Values’ in Schools: A Critical Race Perspective.” Curriculum Perspectives 37 (2): 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-017-0029-3.

- DCLG (Department of Communities and Local Government). 2015. 2015 English IMD Explorer. Accessed July 10, 2019. http://dclgapps.communities.gov.uk/imd/idmap.html.

- Devine, D. 2013. “‘Value’ing Children Differently? Migrant Children in Education.” Children & Society 27 (4): 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12034.

- Driezan, A., N. Clycq, and G. Verschraegen. 2023. “In Search of a Cool Identity: How Young People Negotiate Religious and Ethnic Boundaries in a Superdiverse Context.” Ethnicities 23 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968221126013.

- Farrugia, D. 2014. “Towards a Spatialised Youth Sociology: The Rural and the Urban in Times of Change.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (3): 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.830700.

- Farrugia, D., J. Smyth, and T. Harrison. 2014. “Rural Young People in Late Modernity: Place, Globalisation and the Spatial Contours of Identity.” Current Sociology 62 (7): 1036–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392114538959.

- Fyfe, I. 2010. “Young People and Community Engagement.” In Community Education, Learning and Development, edited by L. Tett, 3rd ed., 69–85. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press.

- Gidley, B. 2013. “Landscapes of Belonging, Portraits of Life: Researching Everyday Multiculture in an Inner City Estate.” Identities 20 (4): 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2013.822381.

- Grover, S. 2004. “Why Won’t they Listen to Us? On Giving Power and Voice to Children Participating in Social Research.” Childhood 11 (1): 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568204040186.

- Harris, A. 2013. Young People and Everyday Multiculturalism. London: Routledge.

- Harris, A. 2014. “Conviviality, Conflict and Distanciation in Young People’s Local Multicultures.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 35 (6): 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2014.963528.

- Harris, A. 2018. “Youthful Socialities in Australia’s Urban Multiculture.” Urban Studies 55 (3): 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016680310.

- Hayes, J., and D. Jones. 2012. “A Tales of Two Analyses: The Use of Archived Qualitative Data.” Sociological Research Online 17 (2).

- Hewitt, R. 1986. White Talk, Black Talk: Interracial Friendship and Communication amongst Adolescents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- House of Commons Library. 2017. Brexit: Votes by Constituency. Accessed July 14, 2019. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/parliament-and-elections/elections-elections/brexit-votes-by-constituency/.

- Høy-Peterson, N., and I. Woodward. 2018. “Working with Difference: Cognitive Schemas, Ethical Cosmopolitanism and Negotiating Cultural Diversity.” International Sociology 33 (6): 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580918792782.

- Huttunen, L., and M. Juntunen. 2020. “Suburban Encounters: Superdiversity, Diasporic Relationality and Everyday Practices in the Nordic Context.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (19): 4124–4141. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1531695.

- Iakhnis, E., B. Rathbun, J. Reifler, and T. J. Scotto. 2018. “Populist Referendum: Was ‘Brexit’ an Expression of Nativist and Anti-Elitist Sentiment?” Research & Politics 5 (2): 205316801877396–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018773964.

- James, M. 2015. Urban Multiculture: Youth, Politics and Cultural Transformation in a Global City. London: Palgrave.

- Jones, H., S. Neal, G. Mohan, K. Connell, A. Cochrane, and K. Bennett. 2015. “Urban Multiculture and Everyday Encounters in Semi-public, Franchised Cafe Spaces.” The Sociological Review 63 (3): 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12311.

- Kerstetter, K. 2012. “Insider, Outsider, or Somewhere Between: The Impact of Researchers’ Identities on the Community-based Research Process.” Journal of Rural Social Sciences 27 (2): 99–117.

- Lentin, A., and G. Titley. 2012. “The Crisis of ‘Multiculturalism’ in Europe: Mediated Minarets, Intolerable Subjects.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 15 (2): 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549411432384.

- Lumsden, K., J. Goode, and A. Black. 2019. “‘I Will not Be Thrown Out of the Country Because I’m an Immigrant’: Eastern European Migrants’ Responses to Hate Crime in a Semi-Rural Context in the Wake of Brexit.” Sociological Research Online 24 (2): 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780418811967.

- Lymperopoulou, K. 2020. “Immigration and Ethnic Diversity in England and Wales Examined Through an Area Classification Framework.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 21 (3): 829–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00678-9.

- Macdougall, A. I., A. R. Feddes, and B. Doosje. 2020. ““They've Put Nothing in the Pot!”: Brexit and the Key Psychological Motivations Behind Voting ‘Remain’ and ‘Leave’.” Political Psychology 41 (5): 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12660.

- Mackrell, P., and S. Pemberton. 2018. “New Representations of Rural Space: Eastern European Migrants and the Denial of Poverty and Deprivation in the English Countryside.” Journal of Rural Studies 14 (1): 107–117.

- Markham, C., and G. Bosworth. 2016. “The Village Pub in the Twenty-first Century: Embeddedness and the ‘Local’.” In Brewing, Beer and Pubs, edited by I. Cabras, D. Higgins, and D. Preece, 266–281. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Meissner, F. 2020. “Growing up with Difference: Superdiversity as a Habitual Frame of Reference.” In Youth in Superdiverse Societies: Growing up with Globalization, Diversity and Acculturation, edited by P. F. Titzmann, and P. Jugert, 7–22. London: Routledge.

- Moore, H. 2021. “Perceptions of Eastern European Migrants in an English Village: The Role of the Rural Place Image.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1): 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1623016.

- Morrice, L. 2017. “Cultural Values, Moral Sentiments and the Fashioning of Gendered Migrant Identities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (3): 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1211005.

- Neal, S. 2002. “Rural Landscapes, Representations and Racism: Examining Multicultural Citizenship and Policy-Making in the English Countryside.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 25 (3): 442–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870020036701c.

- Neal, S., and J. Agyeman, eds. 2006. The New Countryside? Ethnicity, Nation and Exclusion in Contemporary Rural Britain. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Neal, S., K. Bennett, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2019. “Community and Conviviality? Informal Social Life in Multicultural Places.” Sociology 53 (1): 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518763518.

- Neal, S., K. Bennett, H. Jones, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2015. “Multiculture and Public Parks: Researching Super-diversity and Attachment in Public Green Space.” Population, Space and Place 21 (5): 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1910.

- Neal, S., A. Gawlewicz, J. Heley, and R. D. Jones. 2021. “Rural Brexit? The Ambivalent Politics of Rural Community, Migration and Dependency.” Journal of Rural Studies 82: 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.017.

- Neal, S., and S. Walters. 2007. “‘You Can Get Away with Loads Because There’s No One Here’: Discourses of Regulation and Non-regulation in English Rural Spaces.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 38: 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.07.003.

- Neal, S., and S. Walters. 2008. “Rural Be/Longing and Rural Social Organizations: Conviviality and Community-making in the English Countryside.” Sociology 42 (2): 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038507087354.

- Odenbring, Y., and T. Johansson. 2019. ““If They're Allowed to Wear a Veil, We Should Be Allowed to Wear Caps”: Cultural Diversity and Everyday Racism in a Rural School in Sweden.” Journal of Rural Studies 72: 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.033.

- ONS (Office for National Statistics). 2012. KS291EW Ethnic Group, Local Authorities in England and Wales. Accessed July 10, 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/2011censuskeystatisticsforlocalauthoritiesinenglandandwales.

- Ossewaarde, M. 2014. “The National Identities of the ‘Death of Multiculturalism’ Discourse in Western Europe.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 9 (3): 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2014.912655.

- O’Toole, T. 2021. “Governing and Contesting Marginality: Muslims and Urban Governance in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (11): 2497–2515. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1696670.

- Panelli, R., P. Hubbard, B. Coombes, and S. Suchet-Pearson. 2009. “De-centring White Ruralities: Ethnic Diversity, Racialisation and Indigenous Countrysides.” Journal of Rural Studies 25: 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.05.002.

- Phillips, D. 2006. “Parallel Lives? Challenging Discourses of British Muslim Self-segregation.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24 (1): 25–40.

- Pötzsch, T. 2020. “Critical Social Inclusion as an Alternative to Integration Discourses in Finnish and Canadian Integration Education Programs.” Siirtolaisuus – Migration 46 (4): 18–21.

- Radford, D. 2016. “‘Everyday Otherness’ – Intercultural Refugee Encounters and Everyday Multiculturalism in a South Australian Rural Town.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (13): 2128–2145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1179107.

- Rhys-Taylor, A. 2013. “The Essences of Multiculture: A Sensory Exploration of an Inner-city Street Market.” Identities 20 (4): 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2013.822380.

- Robinson, K. 2020. “Everyday Multiculturalism in the Public Library: Taking Knitting Together Seriously.” Sociology 54 (3): 556–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519899352.

- Spiliopoulos, G., S. Cuban, and K. Broadhurst. 2021. “Migrant Care Workers at the Intersection of Rural Belonging in Small English Communities.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 19 (2): 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2020.1801941.

- Sturgis, P., I. Brunton-Smith, J. Kuha, and J. Jackson. 2014. “Ethnic Diversity, Segregation and the Social Cohesion of Neighbourhoods in London.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (8): 1286–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.831932.

- Thomas, P. 2016. “Youth, Terrorism and Education: Britain’s Prevent Programme.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 35 (2): 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2016.1164469.

- Thompson, N. 2019. “Where is Faith-based Youth Work Heading?” In Youth Work: Global Futures, edited by G. Bright, and C. Pugh, 166–183. Leiden: Brill.

- Tonkiss, K. 2013. “Post-national Citizenship without Post-national Identity? A Case Study of UK Immigration Policy and Intra-EU Migration.” Journal of Global Ethics 9 (1): 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2012.756418.

- Triandafyllidou, A. 1998. “National Identity and the ‘Other’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21 (4): 593–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198798329784.

- Tudor, A. 2023. “Ascriptions of Migration: Racism, Migratism and Brexit.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 26 (2): 230–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494221101642.

- Tyler, K. 2003. “The Racialised and Classed Constitution of English Village Life.” Ethnos 68 (3): 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/0014184032000134504.

- Valluvan, S. 2016. “Conviviality and Multiculture: A Post-integration Sociology of Multi-ethnic Interaction.” Young 24 (3): 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308815624061.

- Vertovec, S. 2015. “Migration, Cities, Diversities ‘Old’ and ‘New’.” In Diversities Old and New: Migration and Socio-spatial Patterns in New York, Singapore and Johannesburg, edited by S. Vertovec, 1–20. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Virdee, S., and B. McGeever. 2018. “Racism, Crisis, Brexit.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (10): 1802–1819. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1361544.

- Wessendorf, S. 2014. Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Superdiverse Context. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Wilson, H. 2011. “Passing Propinquities in the Multicultural City: The Everyday Encounters of Bus Passengering.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 43 (3): 634–649. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43354.

- Wilson, H. 2013. “Collective Life: Parents, Playground Encounters and the Multicultural City.” Social & Cultural Geography 14 (6): 625–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.800220.

- Wise, A., and S. Velayutham, eds. 2009. Everyday Multiculturalism. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Woods, M. 2018. “Precarious Rural Cosmopolitanism: Negotiating Globalization, Migration and Diversity in Irish Small Towns.” Journal of Rural Studies 64: 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.014.

- YMCA. 2019. Cuts to Youth Services to Reach Breaking Point during Critical Time for Youth Community Support. Accessed September 26, 2019. https://www.ymca.org.uk/latest-news/cuts-to-youth-services-to-reach-breaking-point-during-critical-time-for-youth-community-support.