ABSTRACT

In this paper, I explore how the racial structure of an immigrant-receiving Latin American society informs the strategies that are available to its members when they are confronted with the arrival of perceived racial outsiders. Using survey data, I explore how Dominicans responded to the rapid influx of displaced Haitians in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and find that when surveyed after the earthquake, Dominicans were more likely to self-identify with the popular and nationalist identity category of indio. I argue that this signaled a heightening of anti-Haitian sentiment in a moment of perceived increased racial threat to the Dominican racial order, and that this shift was facilitated by Latin American racial dynamics that allow for movement between enumerated racial categories in societies structured around the logic of mestizaje.

Introduction

Much of the existing research on migration focuses on how immigrants change when they arrive in a new society, either through assimilation and acculturation or through the rise of subsequent immigrant generations (Alba and Nee Citation2004; Waters et al. Citation2010). Other migration research focuses on how members of the receiving society change or maintain the status quo in the face of increased migration by perceived racial outsiders (Abascal Citation2020; Lee et al. Citation2003). This article is linked to these latter works and furthers the argument that upon the arrival of a differently racialized group, members of a receiving society will rely on context-specific strategies that are both informed by and reinforcing of their place in the racial order, especially when the migration is perceived as posing a racial threat. This means that in the United States, for example, where the legacies of US slavery and Jim Crow underpin a binary Black/White color line, people respond in ways that reinforce their position in the racial structure as determined by the US racial formation project (Omi and Winant Citation1986). Responses would presumably differ in immigrant receiving societies with different racial structures, such as those in Latin America, where racial systems are more fluid and organized around variations of mestizaje (Moreno Figueroa Citation2010). However, Latin American countries are often positioned as senders of immigrants and not recipients, so we have not yet fully distinguished what this might look like in the region.

In this article, I use the influx of displaced Haitians to the Dominican Republic after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti as a case for understanding how members of an immigrant-receiving society respond to the arrival of perceived racial outsiders. Why was this migratory movement perceived as a racial threat to the Dominican Republic? How did the racial structure of the country inform the ways Dominicans responded? To answer these questions, I use data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project’s (LAPOP) AmericasBarometer Survey to analyze trends in Dominican racial self-identification after the earthquake. I find that when surveyed about their racial identity, Dominicans generally became more likely to self-select the nationalist racial category of indio than the other options available to them. Indio is an intermediary racial classification that has historically been constructed to signal Dominican nationhood and racial and social distance from Blackness and Haiti in the Dominican Republic. I argue that the increased likelihood of Dominicans self-selecting this category during a time of heightened racial threat represents a reaffirming of the state racial project of Dominicanidad and a reinforcing of the Dominican racial order.

Both the elevation of an intermediary racial category as representative of nationhood and the fluidity in self-categorization that is possible in Latin America can be attributed to the structuring role that mestizaje plays in the region (Paredes Citation2018; Telles and Bailey Citation2013). Research shows that people have exploited the boundaries between enumerated racial categories in Latin American societies since the colonial period to make strategic moves both toward and away from particular categories (Rappaport Citation2014). Historian Robert McCaa (Citation1984) referred to the reselection of one’s enumerated racial category for some gain or benefit as racial drift, in reference to how doing so allowed people to “drift” up the racial order. Here, I include calls for national cohesion and social differentiation in response to racial threat as additional reasons why people may strategically seek racial improvement through the use of enumerated racial categories, and position the Dominican trend toward the nationalist identity category of indio as a kind of racial drift that was both facilitated by and reinforcing of the racial order in the Dominican Republic.

I use this article to further existing work in two ways. First, I highlight the structuring role of race in a receiving society and how it informs the responses of the non-migrant population when contending with an incoming group. Second, I expand the analysis on immigration by including Latin America as a site of migratory reception. The centering the United States and Europe as recipients of immigrants from the global south is an analytic approach in migration studies that has historically undermined understandings of population change and migratory reception in regions that are seen as marginal or secondary to these powers. This approach limits our understanding of migration and its outcomes to a set of local, rather than global, phenomena and, subsequently, limits what we know about the breadth of strategies used to maintain different racial structures.

Responding to racial threat

Blalock’s (Citation1967) theory of racial threat proposes that the rapid growth of a population that is racially, ethnically, or culturally different from the receiving society invokes hostility toward the incoming group. This hostility reflects the belief that as the out-group gains, the in-group loses, a zero-sum approach that frames the out-group as economic, social, and political threats to the dominant social order (Blumer Citation1958). These theories have been empirically tested in numerous studies, though much of what we know about racial threat and group position has emerged from studies on how White and Black Americans relate to each other or to others in light of increased migration. Studies of residential segregation in the US, for example, have shown that as minority populations increase, White people grow more likely to move out of their neighborhoods, a pattern known as white flight (Crowder and South Citation2008). Even the perception of increased proximity to racial and ethnic minorities can be linked to heightened threat responses among Whites (Hall and Krysan Citation2017). Others have proposed that increased intergroup proximity leads to decreased racial animosity instead, though the role of proximity in mitigating group threat has been debated, with research showing that its effectiveness for minimizing perceptions of group threat depends on the nature of the proximity and the geographic scale of analysis (Allport Citation1954; Weber Citation2015).

Ultimately, different groups will respond to perceived racial threat in ways that are both informed by and reinforcing of their position relative to the arriving group (Gómez Citation2020). In the US, where the racial structure systematically positions White people at the top of the social order, research has shown that when they perceive racial threat from immigration, White people protect their interests as the dominant group by constricting the boundaries of Whiteness (Abascal Citation2015; Citation2020; Lee and Bean Citation2010). These threat responses can manifest as increased hostility and racial prejudice (Bobo and Hutchings Citation1996), and are associated with White support for decreases to social welfare programs (Brown Citation2013), for increased law enforcement and punitive action (Lehmann et al. Citation2022), and for politicians who antagonize minority groups (Knowles and Tropp Citation2018). More extreme beliefs about White replacement have led to acts of violence carried out in the name of White supremacy (Paul Citation2021). On the other hand, Black people in the US tend to have more positive views of immigrants (Sheares Citation2023), though this relationship is mediated by a number of factors, including whether the immigrants are seen as competition for resources or political advantages (Waters, Kasinitz, and Asad Citation2014).

Few studies have examined racial threat and immigrant reception in Latin America, despite the fact that the region has historically been a site of migration from all over the world (Moya Citation2018). Existing research from Latin American scholars confirms that Latin America is not exempt from some of the dynamics discussed so far. One study of racial threat in Argentina, for example, found that the Argentine framed both migrants from outside the country as well as Indigenous populations within the country as dangerous social threats from 2015 to 2019 (Caggiano and Mombello Citation2020). Torre Cantalapiedra (Citation2019) identified an increase in racist and xenophobic online language framing Haitians passing through Mexico on their way to the US as deviant and as threats to Mexican culture, health, and safety. Others examine responses to Venezuelans in Peru (Santos Alvarado Citation2021) and to Peruvians, Bolivians, and Colombians in Chile (Carmona-Halty, Navas, and Rojas-Paz Citation2018), showing that people in Latin America engage in anti-Blackness and anti-Indigenous sentiments, spread hateful rhetoric, and, in some cases, become physically violent in response to perceived racial threats from immigration. However, these studies often stop short of exploring how the racial structures of these societies inform these threat responses and the ways they position themselves relative to the incoming group.

Racial threat and mestizaje

In order to understand racialized immigrant reception in Latin America, it is important to understand mestizaje, the dominant racial logic in the region. The term “mestizaje” has historically referred to racial mixture, particularly between Indigenous and European peoples, but it has evolved from the colonial period and now largely refers to discourses of racial inclusion that signal belonging to a nation (Moreno Figueroa Citation2010). The distinct colonial histories and nation-building projects of Latin American and Hispanic Caribbean countries over time has resulted in numerous country-specific articulations of mestizaje, though the resulting racial hierarchies are ultimately similar (Bonilla-Silva Citation2020; Marx Citation1998). Generally, a racially mixed mestizo group is positioned as a carrier of national identity, and represents “the racialization of cultural characteristics” such as language, culture, and traditions (Paredes Citation2018, 4). At the same time, Black or Indigenous people, depending on the country, are relegated to the lowest social position, and White people, though not numerically the majority, wield the most political and economic power (Bonilla-Silva Citation2020). In the Dominican Republic, mestizaje has taken on a distinctly anti-Black and anti-Haitian character, as political elites have sought to erase country’s Black ancestry in favor of narratives centering Hispanic and indigenous ancestry (Simmons Citation2009). This differs from places like Brazil or Guatemala, for example, where racial consciousness movements and the legal recognition of multiculturalism have increased recognition of Black and Indigenous identity (da Silva Martins, Medeiros, and Nascimento Citation2004).

Though there are differences in the local manifestations of mestizaje, the inherent contradiction of this system is evident throughout the region as racial inequalities persist despite the characterization of race in Latin America as ambiguous and fluid, and therefore socially inconsequential (Loveman Citation2014; Telles Citation2014). This idea that Latin America is a racial democracy where race does not matter obscures both the region’s pervasive racial stratification, and the ways in which people and countries have taken advantage of this purported racial fluidity over time to marginalize both Black and Indigenous communities (Peña, Sidanius, and Sawyer Citation2004). For example, states have historically used immigration as a tool for blanqueamiento, or the whitening of their populations (Sawyer and Paschel Citation2007). Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, one of the primary architects of the Dominican racial project, used immigration from Europe and Asia to minimize the African presence in the Dominican Republic (Metz Citation1990). In line with mestizaje ideals, his goal was for White immigrants to mix into the population and dilute Dominican Blackness over time.

Research has also shown how individuals have historically manipulated the fluid nature of Latin American racial classification to change their classification and drift “up” or “down” the racial hierarchy according to the benefits that they could accrue (Castleman Citation2001; McCaa Citation1984). People have sought reclassification by changing their appearance and behavior in accordance with how particular racial categories were supposed to look and act; by claiming a different racial classification when they moved to new communities; or by acquiring a higher socioeconomic status, which improved their perceived calidad, or social quality (Jackson Citation1995). These moves have been facilitated by the fact that racial identity in Latin America is constructed from a combination of phenotypic, socioeconomic, and genealogical characteristics, which differs from the US, where policies like the one-drop rule created more rigid conditions for racial classification (Khanna Citation2010).

Though enumerated racial categories do not fully capture the lived racial experience of individuals, the hierarchization of a society according to the construction of particular classifications reflects dominant beliefs about who is superior versus inferior, and these beliefs are reflected in the way Latin America’s racial fluidity has been utilized to engage in Whitening at the macro and micro level (Itzigsohn and Dore-Cabral Citation2000).

The Dominican racial formation project

Given that members of a receiving society respond to racial threat in ways that are both informed by and reinforcing of their position in the racial order, and that mestizaje has country-specific manifestations, it is important to understand the racial formation of the Dominican Republic in order to understand how the arrival of Haitians after the earthquake came to be perceived as a racial threat to the country.

On January 12, 2010, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti just west of capital city Port-au-Prince, killing hundreds of thousands and leaving millions injured and displaced (DesRoches et al. Citation2011). In the days and weeks following the earthquake, hundreds of displaced Haitians crossed the historically porous border to the Dominican Republic, seeking out relatives already living in border towns like Pedernales, joining family in other parts of the country, or seeking other refuge (Horst and Taylor Citation2014). During this time, the long-held animosities between Haiti and the Dominican Republic were briefly suspended, creating speculations of reconciliation between the two countries (Romero and Lacey Citation2010). However, this unity would be short-lived, as popular Dominican support dwindled and the Dominican media began sharing alarmist statistics about the number of people coming into the country and suggesting that the displaced Haitians would spread diseases (Guilamo Citation2013; Sagás Citation2012). Ultimately, this moment became a full-blown crisis, and the more widespread visibility of the scale of Haitian migration to the country reignited xenophobic attitudes in the Dominican Republic, stoking nationalist fears of a silent invasion that are rooted in the country’s long and tumultuous history with Haiti (Guilamo Citation2019).

Adversarial beliefs about Haitians, including the belief that they pose a threat to the Dominican Republic, have a long history that can be traced back to the late eighteenth century. After the Haitian Revolution, there was widespread resentment toward Haiti throughout the Americas, and the Spanish Criollos in Santo Domingo, the territory that would become the Dominican Republic, especially feared the new Black republic (Ricourt Citation2016). Haitian president John Pierre Boyer took control of the Dominican side of the island in 1822, and for a period of twenty-two years his policies “produced a hatred of Haitians that eventually converted into a racist negrophobia” that fueled resentment, fear, and hatred of Haitians among white elites (Ricourt Citation2016, 30). Though the Dominican Republic eventually achieved independence from Haiti in 1844, these and other conflicts throughout the century generated intense animosity between the countries. By the time Dominicans began to forge a national identity after achieving their final independence from Spain in 1865, Haiti had become the primary opposition against which this new identity, known as Dominicanidad, was being constructed (García-Peña Citation2016; Sagás Citation2012).

The purpose of Dominicanidad as a national and racial project was to emphasize the cultural and racial distinction between Dominicans and Haitians, and to signal to the global community, especially the United States, that Dominicans were racially different from Haiti and could maintain their autonomy (Adams Citation2006; Zabala Ortiz Citation2022). After a conflictive nineteenth century, the Dominican elite felt that the sovereignty of the nation was at risk, and determined that to achieve modernity, self-determination, and global recognition, they would have to eradicate “primitive” behaviors and attitudes among the populace (Adams Citation2006, 57). Associating these characteristics with Blackness, they constructed a Dominicanidad that uplifted the Hispanic and Indigenous origins of the nation and minimized its African heritage, externalizing Blackness only to Haiti (Sagás Citation2000). Various intellectuals at this time, notably in the field of literature, amplified this racial project to the populace, promoting mythologized versions of the country’s indigenous past to unite Dominicans under a common origin story (García-Peña Citation2016). This reframing allowed non-White Dominicans to be part of the nation under the label of indio, because it attributed their racial difference to an Indigenous ancestor rather than an African one and differentiated them from the Blackness of Haiti and Haitians (García-Peña Citation2016).

As he came into power in 1930, Dictator Rafael Trujillo capitalized on these brewing anti-Haitian sentiments to stoke fear of invasion and justify numerous cruelties against Haitians, Dominicans of Haitian descent, and Black Dominicans. Most infamously, this includes El Corte, the 1937 massacre of thousands in Dominican border communities (Paulino Citation2016). Trujillo also furthered institutionalized indio as a category for Dominican racial identification that both denoted racial mixture and adherence to the nation-building project of Dominicanidad. He made indio an official color category on national identification documents, cementing it's national and nationalist significance, and the term eventually replaced terms like mulato and negro in the national lexicon (Sagás Citation2000; Simmons Citation2009). In the following sections, I show how this category, which distances Dominicans from “their African heritage and ideas of Blackness”, became more significant during a moment of perceived racial threat after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti as Dominicans sought to distance itself from the incoming migrants (Simmons Citation2009, 29).

Data and methods

I use data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project’s (LAPOP) AmericasBarometer Survey (ABS), the 2010 Dominican National Census, and the 2012 National Survey of Immigrants (ENI) to show how Dominicans responded to the arrival of displaced Haitians after the 2010 earthquake. The ABS is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey implemented every two years to capture public opinion and political beliefs in the Americas. In the Dominican Republic, the survey relies on a national probability sample of approximately 1,500 voting-age Dominicans who are over eighteen years old.Footnote1 All respondents were non-immigrant citizens or residents of the Dominican Republic.

The National Office of Statistics implemented the 2010 census from December 1 to December 7, 2010. The 2006, 2008, and 2010 ABS are nationally representative according to the 2000 census, while sampling for 2012 and 2014 was adjusted to be nationally representative according to the 2010 census. The National Office of Statistics implemented the 2012 ENI to supplement the 2010 census. This was the first large-scale survey of immigrants in the Dominican Republic, and it sought to estimate the size of the immigrant population and their contributions to the country (Oficina Nacional de Estadistica Citation2012). The 2012 ENI used probability sampling to capture a nationally representative sample of the immigrant population, and includes 68,146 households and 20,499 individuals.

Dependent variables

The dependent variable captures ethnoracial self-identification as measured by the survey question: “Do you identify as White, Black, indio, mixed, or other?” In the Dominican Republic, color categories are used in lieu of what would be considered racial categories in the United States, as raza refers more broadly to a race of people rather than to a subgroup of a population (Mayes Citation2014; Telles and Bailey Citation2013). Currently, the Dominican government officially recognizes six skin color categories: blanco, amarillo, indio, mestizo, mulato, and negro. It is important to note that these are color categories and “do not correspond to collective identities grounded in a specific racial consciousness” (Simmons Citation2009, 13). The ABS options align with these categories, though it combines the categories of indio and mestizo and does not include amarillo. The category of otro/Other is included, likely to capture those who would have self-selected amarillo or categories not listed. I discarded this category due to negligible response numbers. In cases where there were multiple options indicating Afro-descendency (Dominicano negro, Afro-Dominicano, etc.) in a single year, I collapsed those options into the negro/Black category for consistency. I also removed respondents who did not answer or had missing values for this question. I also removed respondents who indicated their first language was not Spanish, which represented less than 1 per cent of the sample. The final pooled sample represents 8,557 non-immigrant Dominicans.

Independent variable

The independent variable is survey year (2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014). Data collection for each wave occurred during the year indicated by the variable. I did not include the 2016 and 2018 ABS due to differences in the survey instrument compared to prior waves. The 2010 ABS was implemented in February and March of 2010, offering a snapshot of Dominicans’ attitudes one month after the earthquake and during the subsequent migration crisis.

Control variables

This analysis considers several demographic, socioeconomic, attitudinal, and geographic controls. The demographic variables include sex (female = 1, male = 0), a continuous age variable, age squared, civil status (married = 1, not = 0), and religious affiliation (Catholic = 1, not = 0). Age is a continuous numerical variable and age squared is included to control for the effect of the life cycle. I included religious affiliation because prior research has shown that Catholicism is a central tenet of Dominicanidad and that religion plays a large role in structuring race relations in the country (Paredes Citation2019). Additionally, I included measures of socioeconomic status, such as educational attainment (years completed), a continuous household income measure, and employment (1 = employed, 0 = not).

Attitudinal measures consist of two seven-item Likert scales measuring agreement with a given statement or question from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). One asks, “To what extent do you agree that the children of Haitian migrants born in the Dominican Republic are Dominican citizens?” The other asks, “To what extent do you agree or disagree that the Dominican government grant work permits to undocumented Haitians living in the Dominican Republic?” These questions are indicators of anti-Haitian attitudes among respondents. Lastly, I include a geographic measure at the regional level to account for geographic proximity to the displaced population in the areas they migrated to after the earthquake. Regions in the Dominican Republic have been historically racialized, with the North being portrayed as “Whiter” than other parts of the country and the East and the South, historically sites of plantation labor, being portrayed as home to darker Dominicans, Haitians, and West Indian laborers (Martínez Citation1997; Werner Citation2011). Though there are three macro-regions in the country, the ABS separates the capital and the surrounding metropolitan area into its own region to improve their sampling strategy. Thus, the regions included in the survey are the North, East, South, and Metropolitan regions. For consistency, I matched the DNC and ENI data to correspond with the ABS regions, and I also include a variable that indicates whether the respondent lives in an urban (1) or rural (0) area.

Analysis

To analyze these data, I first calculated descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study (). I then calculated Haitian immigration rates at the regional and country level to determine which areas of the country saw the greatest influx of arrivals, and conducted a bivariate analysis to determine the nature of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable. Next, I estimated two nested multinomial logistic regression (MNLM) models. MNLM models use maximum likelihood estimation to determine the probability of belonging to one of multiple independent outcome categories over another, and are used for unordered nominal outcome categories (Long and Freese Citation2006). The models presented here predict the likelihood of self-selecting a racial identification category as a function of the selected demographic, socioeconomic, geographic, and attitudinal variables. Beta coefficients represent the log odds of selecting a category relative to a base category as the values of the covariates change by one unit.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics by category options.

The models demonstrate how a variety of covariates influence the probability of individuals self-selecting the blanco/White, negro/Black, or mulato/mixed categories over the reference category of indio/mestizo. Similar studies that use Dominican ABS data use the negro/Black and mulato/mixed category as reference groups due to their low relative social position (Paredes Citation2019; Telles and Flores Citation2013). However, I use the indio/mestizo category as the refence category because it is convention to use the most frequently selected category in this type of model. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp Citation2019). The data are self-weighted.

Results

Descriptive statistics

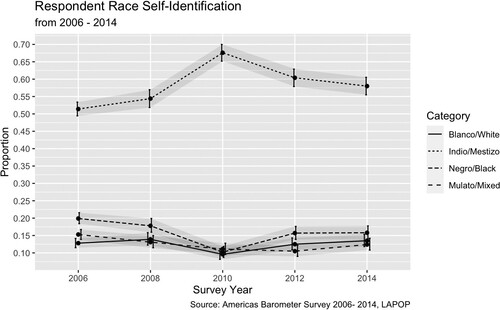

This article’s primary empirical claim is that moments of perceived racial threat increased the attractiveness of self-selecting the category most associated with constructions of Dominican nationhood, in this case the indio/mestizo category. When asked to identify their race, the majority (56.9 per cent) of respondents self-selected the indio/mestizo category every year (). Though the other categories were self-selected with less frequency, there is regional specificity to these selections. While only 12.4 per cent of respondents self-selected blanco/White, the majority (46 per cent) of those who selected this category live in the North, while the largest proportions of both negro/Black identifying (45.8 per cent) and mulato/mixed identifying (48.2 per cent) respondents live in the metropolitan region.

There are socioeconomic differences between categories, with those who selected mulato/mixed having both the highest mean years of education completed and the greatest likelihood of having higher education, with 4.9 per cent reporting that they completed college. Mulato/mixed identifying respondents also had the highest mean household income. Though this seems anomalous given that mulato is a category of mixture seen as more proximate to Blackness, these findings are consistent with prior research showing that the term is prevalent primarily among the liberal middle and upper classes who tend to have higher socioeconomic outcomes (Howard Citation2001; Roth Citation2012). Conversely, the negro/Black identifying respondents had the lowest mean years of education, and only 2.3 per cent of respondents who chose this category finished college. Respondents who selected negro/Black and mulato/mixed report a slightly higher employment rate than other respondents though they report lower mean household income, suggesting that while they may be employed, their employment may be informal or low paying. Ultimately, the data are consistent with prior findings that “the darker a Dominican is, the more likely s/he is to be poor, undernourished, badly housed, and deprived of formal education” (Martínez Citation1997, 235).

Bivariate analysis

demonstrates the bivariate relationship between the dependent and independent variable, which is the proportion of non-immigrant Dominicans that self-selected each of the ethnoracial categories per year of the survey. While indio/mestizo is consistently the most selected category, there is a statistically significant increase in the proportion of people selecting this category between 2008 and 2010. One would expect these proportions to be relatively stable across the survey waves barring any major demographic changes. Instead, the data suggest that the attractiveness of this category increased significantly in 2010. There is also a corresponding statistically significant drop in the proportion of respondents selecting the negro/Black and blanco/White categories in 2010 (). These findings are consistent when aggregated up to the regional level, with each of the regions exhibiting a statistically significant increase on the proportion of respondents selecting indio/mestizo, and a corresponding statistically significant drop in the proportion selecting either blanco/White (North) or the negro/Black (East, South, and Metropolitan).

Figure 1. Respondent racial self-identification by year. Note: LAPOP ABS (2006–2014). Graph features unadjusted proportion with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

At first glance, these patterns seem like statistical or survey error. However, there is nothing about the survey itself that would cause such deviation. Namely, the sampling methods did not change between years, the structure or wording of the question and answers did not change, and there is no discernible error in the coding of the variable between any of the waves used in this study.Footnote2 In additional analyses not shown, I use other data sources to test whether there could have been other demographic factors at the time that could create such a shift, and I find that there were no significant changes to the non-migrant Dominican population in that time that could have caused this change. Thus, I can say with reasonable certainty that the increase in the proportion of people selecting indio/mestizo and the corresponding drop in several of the other categories are not due to error or to fundamental changes to the composition of the population in question. The only exogenous shock that happened around the implementation of the 2010 ABS survey wave, which was collected in February and March of 2010, was the increased migration of Haitians after the earthquake in January 2010.

Predicting category selection

To predict the likelihood of Dominicans self-selecting indio/mestizo versus another available category, I estimated multinomial logistic regression models predicting the log odds of a person self-selecting either blanco/White, negro/Black, or mulato/mixed relative to the indio/mestizo category (). Model 1 shows the log odds of self-selecting these categories relative to the indio/mestizo category and includes demographic, socioeconomic, and attitudinal controls. Results indicate that the most significant predictors of selecting blanco/White over indio/mestizo are year (2010 and 2012), age, civil status, household income, employment status, religion, and attitudes toward Haitian children. The model also suggests that year (2010, 2012, and 2014), civil status, education, household income, religion, and attitudes toward Haitians are the most significant predictors of whether a person will self-select negro/Black over indio/mestizo. Lastly, year (2010, 2012, and 2014), civil status, education, religion, and household income are the most significant predictors of selecting mulato/mixed over indio/mestizo. These results are consistent with findings from prior work using these same data (Paredes Citation2019; Telles and Bailey Citation2013). Model 2 adds region and urban/rural as geographic controls. When geographic controls are included, year (2012 and 2014) civil status and religion are no longer significant predictors for self-selecting negro/Black. Religion is also no longer a significant predictor for self-selecting the mulato/mixed category. However, year (2014) becomes a significant predictor of selecting blanco/White over indio/mestizo.

Table 2. Multinomial Logistic Regression predicting odds ratios of ethno-racial category selection relative to indio/mestizo category among non-immigrant Dominicans.

As expected, the main effects of region show that location influences the likelihood of selecting indio/mestizo versus the non-indio categories. In order to contextualize these findings, it is important to consider which regions of the country saw the greatest changes in their rates of Haitian immigration ( and ). shows, by region, the gross and percent increase of Haitian migrants who made their first-time arrival between 2006–2009 and 2010–2012. shows each region’s Haitian immigration rate compared to the average immigration rate for the three years prior. Though it is impossible in these data to disaggregate the migrants who came because of the earthquake from those who migrated later or for other reasons, the data still show that the North and the East saw the greatest gross and percent increase in new Haitian migrants in and after 2010 across both measures. It is also important to note that there was already a Haitian presence in these regions and throughout the country. This is due, in part, to the Dominican Republic’s historical dependence on Haitian migrants for labor on Dominican sugar and coffee plantations, and increasingly in other sectors throughout the country (Duany Citation2006; Martínez Citation1997).

Table 3. Gross and percent increase of Haitian first-time arrivals 2006–2009 and 2010–2012.

Table 4. 2010 Haitian Immigration rate by region compared to average immigration rate for 2006–2009 and rate difference.

In Model 2, we see that relative to the Metropolitan region, being in the North significantly increases the likelihood of self-selecting the blanco/White category over indio/mestizo category. This suggests that in this region, which is known as the whitest region in the country, this category has more salience even over the national identity category of indio. Additionally, the likelihood of a person self-selecting negro/Black or mulato/mixed significantly decreases, suggesting that for Dominicans in that region, it may have been viewed as undesirable to identify as negro/Black during these moments when Black non-Dominicans were framed as racial threats. There is a similar pattern in the South, where there is a slightly significantly decrease in the likelihood of choosing negro/Black over indio/mestizo. Being in the East, however, is associated with a significant decrease in the likelihood of selecting blanco/White and mulato/mixed over indio/mestizo. These results reflect the descriptive findings presented in , which show that there is a proclivity for Whiteness in the North and for Blackness and mulatez in the East and South.

Aside from year and place, I also include other covariates that influence the likelihood of self-selecting particular identity categories. Some of the effects are slight. An increase in household income is associated with a small increase in the likelihood of selecting indio/mestizo over blanco/White and over mulato/mixed. An increase in this variable is also associated with a slight, but significant, decrease in the likelihood of selecting indio/mestizo over negro/Black, which may reflect the belief that “money whitens” in Latin America, though the research is mixed on the soundness of this theory (Telles and Flores Citation2013). Being employed is associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of selecting blanco/White, another finding that is robust across the models. Other covariates of note include religion and attitudes toward Haitians. Catholicism is associated with an increased likelihood of selecting blanco/White and a decreased likelihood of selecting negro/Black or mulato/mixed, which may reflect a departure from religions practices that are stereotyped as Black, such as voodoo, Santería, and other traditional religions that the White elite have historically framed as contrary to Dominicanidad (Martínez Vergne Citation2005).

The attitudinal variables suggest that those who indicate more agreement with the statements that children of Haitians in the Dominican Republic should get citizenship and that Haitian migrants should get work permits are more likely to identify as negro/mulato than they are to identify as indio/mestizo. This suggests that Dominicans who are willing to identify as negro/Black on the survey may feel some sense of solidarity with the migrants due to their proximity in social status in the country. Agreement with the children's citizenship issue is associated with a slight increase in the likelihood of choosing blanco/White over indio/mestizo, though this effect, along with the effect of the work question on the likelihood of selecting negro/Black, disappears when I control for geography. Additional analysis not shown here indicates that there is a significant association between the year 2010 and a slight decrease in anti-Haitian sentiments and anti-immigrant sentiments compared to prior years. There are several possible explanations for these results. For example, though the country was in a nationalist moment of panic about the Haitian threat, most of the world saw this as a humanitarian crisis, which may have, on the individual level, led to a degree of social desirability bias in the respondents. Additionally, as García-Peña (Citation2016) shows, there were indeed moments in the aftermath of the earthquake where individual glimmers of humanitarianism prevailed despite the popular narratives about invasion, suggesting that anti-Haitian sentiments were not unanimous in the Dominican Republic during this time.

Discussion

This analysis shows the likelihood of Dominicans self-selecting blanco/White, negro/Black, or mulato/mixed to describe their racial identity compared to the likelihood of the respondent selecting indio/mestizo, the normative national identification category, when controlling for year and other factors. Though the indio/mestizo category is the most selected category regardless of the year (), this choice was even more attractive than usual for Dominicans surveyed in the immediate aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, especially over the negro/Black category. I argue that this general trend away from other categories, specifically negro/Black, and toward indio/mestizo is the result of a Dominican racial formation project that has historically framed Haitians and Blackness as a racial threat to the Dominican Republic. It is also an example of a context-specific response to perceived threat from immigration that is informed and reinforcing of the racial structure in a society organized around mestizaje, where the indio/mestizo category is the category that signals Dominicanidad and normative, anti-Black and anti-Haitian constructions of Dominican racial identity.

Mestizaje is a racial system that privileges Whiteness, but it positions an intermediate racial category as a symbol of nation and belonging (Paredes Citation2018). Unlike the US, where national belonging is imbued in White racial identity, and where Whiteness is the desirable status to attain and protect, this middle is symbolically privileged over the extremes, especially when it comes to the question of national identity (Harris Citation1993). In the Dominican Republic, where mestizaje has been adapted into the country-specific ideology of Dominicanidad, the category of indio has come to indicate both racial mixture that is distant from Blackness and a broader Dominican national identity project. Though “the meaning of racial categories is neither shared nor fixed”, most Dominicans see the category of indio as a color gradation in-between the extremes of White and Black with a particular national specificity in what this category symbolizes, lending it additional meaning and political weight (Torres-Saillant Citation2000; Thornton and Ubiera Citation2019, 416). Thus, the magnitude of identifying as indio on a survey or a census is greater when we take into consideration the historical and political meaning attached to this category, and what it symbolizes to take on this identity (Ramírez Citation2018). Accompanying this increase was a decrease in the likelihood of individuals selecting other categories, such as blanco/White, negro/Black, and mulato/mixed. Though the data suggest a level of awareness about Dominicans’ African origins, the trend toward taking on the identity of indio indicates a general preference for the nationalist narrative of origin, which follows mestizaje ideologies in promoting distance from Blackness and in the Dominican case specifically, distance from Haitians.

In order to understand the social significance of these trends, it is also important to understand the socio-political landscape of the Dominican Republic in the post-earthquake period. Research shows that after the earthquake, electoral support for right-wing anti-immigrant politicians increased in areas with higher concentrations of Haitian immigrants (Jaupart Citation2018). Additionally, the government changed the Dominican Constitution just weeks after the earthquake to delineate the official national symbols, such as the flag, national anthem, official language, and coat of arms (Guilamo Citation2013; La Asamblea Nacional Citation2010; Román and Sagás Citation2017). National symbols have been historically chosen and manipulated to bolster ethnic and national identities, as well as to evoke a shared national memory, so this may be further evidence of an effort to sharpen the boundary between the Dominicans and Haitians and to bring Dominicans together under a unified national identity (Baud Citation2005). Lastly, the media played a crucial role in heightening fear among Dominicans post-earthquake, which shows that the reactions were also informed by a top-down spread of misinformation about new Haitian arrivals (Guilamo Citation2013).

These changes were all precursors to La Sentencia, the 2013 decision to retroactively revoke the citizenship of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent (Román and Sagás Citation2017). These and other policies over the past fifteen years or so have culminated in continued marginalization and violence against Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent, and a mass deportation regime that has expelled thousands of people of Haitian descent from the Dominican Republic (Childers Citation2023). Taken together, the findings of this study, the policy changes that have been implemented by the Dominican state since the earthquake, and the continued violence against Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent in the country all demonstrate how this brief period came to be perceived as a moment of racial threat for the Dominican Republic, where people responded by aligning themselves more closely with the racial project of Dominicanidad.

Conclusion

This study has several important implications for understanding the dynamics of race and migration. First, it builds on work showing that in the face of perceived threat, members of an immigrant-receiving society will respond using context-specific strategies that both reinforce and are informed by their position in the racial order of their society. Second, it centers Latin America as a site of migratory reception, allowing us to study and recontextualize dynamics primarily observed in Europe and the United States. This and other research show that Latin America is not exempt from racialized responses to migration, though the particulars may vary depending on the country due to country-specific manifestations of mestizaje.

One limitation of this work is that the data used in this study are cross-sectional, meaning that they track different people at different points in time, rather than the same people over multiple years. Therefore, I can only claim that these results are indicative of general trends in the population studied rather than specific changes occurring in individuals’ self-conceptions of race. Additionally, survey data are imperfect, especially for studying racial dynamics in a population, so the quantitative nature of this study does not allow for in-depth understandings of how Dominicans thought about race or the migration crisis after the earthquake. Future work should qualitatively explore the role of migration in shaping race relations in immigrant-receiving societies and the types of response strategies that are available in societies structured around different racial ideologies, especially in other Latin American countries. Moving forward, studying responses to racial threat in the context of migration may help us to better understand the nature of global race relations in our increasingly transnational world.

Acknowledgements

I thank Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, the editors, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions in the production of this manuscript. I thank LAPOP and their funders. A version of this paper was presented at the 2023 meeting of the Southern Sociological Association. Screening for IRB Exemption granted by Duke Campus IRB, Protocol #2020-0130.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For public, unrestricted survey data and technical information about LAPOP sampling, visit: http://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/core-surveys.php.

2 Communications with LAPOP confirmed this.

References

- Abascal, Maria. 2015. “Us and Them: Black-White Relations in the Wake of Hispanic Population Growth.” American Sociological Review 80 (4): 789–813. doi:10.1177/0003122415587313.

- Abascal, Maria. 2020. “Contraction as a Response to Group Threat: Demographic Decline and Whites’ Classification of People Who Are Ambiguously White.” American Sociological Review 85 (2): 298–322. doi:10.1177/0003122420905127.

- Adams, Robert L. 2006. “History at the Crossroads: Vodú and the Modernization of the Dominican Borderlands.” In Globalization and Race, edited by Kamari Maxine Clarke, and Deborah A. Thomas, 55–72. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822387596-003

- Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 2004. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” In The New Immigration: An Interdisciplinary Reader, edited by Carola Suarez-Orozco. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203621028

- Allport, Gordon Willard. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Baud, Michel. 2005. “Constitutionally White: The Forging of a National Identity in the Dominican Republic.” In Ethnicity in the Caribbean: Essays in Honor of Harry Hoetink, edited by Gert Oostindie, 121–151. Amsterdam University Press.

- Blalock, Hubert. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York: Wiley.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7. doi:10.2307/1388607.

- Bobo, Lawrence, and Vincent L. Hutchings. 1996. “Perceptions of Racial Group Competition: Extending Blumer’s Theory of Group Position to a Multiracial Social Context.” American Sociological Review 61 (6): 951. doi:10.2307/2096302.

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2020. “¿Aquí No Hay Racismo? Apuntes Preliminares Sobre Lo Racial En Las Américas.” Revista de Humanidades 42: 425–443. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321265117017.

- Brown, Hana E. 2013. “Race, Legality, and the Social Policy Consequences of Anti-Immigration Mobilization.” American Sociological Review 78 (2): 290–314. doi:10.1177/0003122413476712.

- Caggiano, Sergio, and Laura Mombello. 2020. “Inmigrantes e Indígenas En Las Torsiones de La Nacionalidad y La Ciudadanía. La Construcción de Amenazas En Argentina (2015-2019).” Historia y Sociedad 39: 130–154. doi:10.15446/hys.n39.82887.

- Carmona-Halty, Marcos A., Marisol Navas, and Paulina Rojas-Paz. 2018. “Outgroup Threat Perception, Intergroup Contact and Affective Prejudice Towards Latin American Migrant Groups Residents in Chile.” Interciencia 43 (1): 23–27.

- Castleman, Bruce A. 2001. “Social Climbers in a Colonial Mexican City: Individual Mobility Within the Sistema de Castas in Orizaba, 1777-1791.” Colonial Latin American Review 10 (2): 229–249. doi:10.1080/10609160120093796.

- Childers, Trenita B. 2023. “The Role of Anti-Haitian Racism in Dominican Mass Deportation Policy.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 24 (1): 107–113. doi:10.1353/gia.2023.a897708.

- Crowder, Kyle, and Scott J. South. 2008. “Spatial Dynamics of White Flight: The Effects of Local and Extralocal Racial Conditions on Neighborhood Out-Migration.” American Sociological Review 73 (5): 792–812. doi:10.1177/000312240807300505.

- da Silva Martins, Sérgio, Carlos Alberto Medeiros, and Elisa Larkin Nascimento. 2004. “Paving Paradise: The Road From ‘Racial Democracy’ to Affirmative Action in Brazil.” Journal of Black Studies 34 (6): 787–816. doi:10.1177/0021934704264006.

- DesRoches, Reginald, Mary Comerio, Marc Eberhard, Walter Mooney, and Glenn J. Rix. 2011. “Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake.” Earthquake Spectra 27 (Suppl. 1): 1–21. doi:10.1193/1.3630129.

- Duany, Jorge. 2006. “Racializing Ethnicity in the Spanish-Speaking Caribbean.” Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 1 (2): 231–248. doi:10.1080/17442220600859478.

- García-Peña, Lorgia. 2016. The Borders of Dominicanidad: Race, Nation, and Archives of Contradiction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Gómez, Laura E. 2020. Inventing Latinos: A New Story of American Racism. New York, NY: The New Press.

- Guilamo, Daly. 2013. “Dominican Funnies, Not so Funny: The Representation of Haitians in Dominican Newspaper Comic Strips, After the 2010 Earthquake.” Journal of Pan African Studies 5 (9): 63–82.

- Guilamo, Daly. 2019. “The Virility of the Haitian Womb: The Biggest Threat to the Dominican Right.” In Challenging Misrepresentations of Black Womanhood: Media, Literature and Theory, edited by Marquita M. Gammage, and Antwanisha Alameen-Shavers, 74–94. London: Anthem Press.

- Hall, Matthew, and Maria Krysan. 2017. “The Neighborhood Context of Latino Threat.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 3 (2): 218–235. doi:10.1177/2332649216641435.

- Harris, Cheryl I. 1993. “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review 106 (8): 1707. doi:10.2307/1341787.

- Horst, Heather A., and Erin B. Taylor. 2014. “The Role of Mobile Phones in the Mediation of Border Crossings: A Study of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 25 (2): 155–170. doi:10.1111/taja.12086.

- Howard, David John. 2001. Coloring the Nation: Race and Ethnicity in the Dominican Republic. Oxford: Signal Books; L. Rienner Publishers.

- Itzigsohn, Jose, and Carlos Dore-Cabral. 2000. “Competing Identities? Race, Ethnicity and Panethnicity Among Dominicans in the United States.” Sociological Forum 15 (2): 225–247. doi:10.1023/A:1007517407493.

- Jackson, Robert H. 1995. “Race/Caste and the Creation and Meaning of Identity in Colonial Spanish America.” Revista de Indias 55 (203): 149. doi:10.3989/revindias.1995.i203.1122.

- Jaupart, Pascal. 2018. “Divided Island: Haitian Immigration and Electoral Outcomes in the Dominican Republic.” Journal of Economic Geography 18 (4): 951–999. doi:10.1093/jeg/lby030.

- Khanna, Nikki. 2010. “‘If You’re Half Black, You’re Just Black’: Reflected Appraisals and the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule.” The Sociological Quarterly 51 (1): 96–121. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01162.x.

- Knowles, Eric D., and Linda R. Tropp. 2018. “The Racial and Economic Context of Trump Support: Evidence for Threat, Identity, and Contact Effects in the 2016 Presidential Election.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 9 (3): 275–284. doi:10.1177/1948550618759326.

- La Asamblea Nacional. 2010. Constitución de La República Dominicana.

- Lee, Jennifer, and Frank D. Bean. 2010. The Diversity Paradox: Immigration and the Color Line in Twenty-First Century America. UPCC Book Collections on Project MUSE. Russell Sage Foundation. https://books.google.com/books?id=FFNQWhO0PRAC.

- Lee, Jennifer, Frank D. Bean, Jeanne Batalova, and Sabeen Sandhu. 2003. “Immigration and the Black-White Color Line in the United States.” The Review of Black Political Economy 31 (1–2): 43–76. doi:10.1007/s12114-003-1003-x.

- Lehmann, Peter S., Cecilia Chouhy, Alexa J. Singer, Jessica N. Stevens, and Marc Gertz. 2022. “Group Threat, Racial/Ethnic Animus, and Punitiveness in Latin America: A Multilevel Analysis.” Race and Justice 12 (4): 669–694. doi:10.1177/2153368720920347.

- Long, J. Scott, and Jeremy Freese. 2006. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLP.

- Loveman, Mara. 2014. National Colors: Racial Classification and the State in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martínez, Samuel. 1997. “The Masking of History: Popular Images of the Nation on a Dominican Sugar Plantation.” NWIG: New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 71 (3/4): 227–248. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002606.

- Martínez Vergne, Teresita. 2005. Nation & Citizen in the Dominican Republic, 1880-1916. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Marx, Anthony W. 1998. Making Race and Nation: A Comparison of the United States, South Africa, and Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mayes, April J. 2014. The Mulatto Republic: Class, Race, and Dominican National Identity. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- McCaa, Robert. 1984. “Calidad, Clase, and Marriage in Colonial Mexico: The Case of Parral, 1788-90.” Hispanic American Historical Review 64 (3): 477. doi:10.1215/00182168-64.3.477.

- Metz, Allan. 1990. “Why Sosúa? Trujillo’s Motives for Jewish Refugee Settlement in the Dominican Republic.” Contemporary Jewry 11 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1007/BF02965538.

- Moreno Figueroa, Mónica G. 2010. “Distributed Intensities: Whiteness, Mestizaje and the Logics of Mexican Racism.” Ethnicities 10 (3): 387–401. doi:10.1177/1468796810372305.

- Moya, José. 2018. “Migration and the Historical Formation of Latin America in a Global Perspective.” Sociologias 20 (49): 24–68. doi:10.1590/15174522-02004902.

- Oficina Nacional de Estadistica (ONE). 2010. “Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda.” https://www.one.gob.do/censos/poblacion-y-vivienda.

- Oficina Nacional de Estadistica (ONE). 2012. “Encuesta Nacional de Inmigrantes (ENI).” https://www.one.gob.do/encuestas/eni.

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 1986. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. New York: Routledge.

- Paredes, Cristian L. 2018. “Multidimensional Ethno-Racial Status in Contexts of Mestizaje: Ethno-Racial Stratification in Contemporary Peru.” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 4. doi:10.1177/2378023118762002.

- Paredes, Cristian L. 2019. “Catholic Heritage, Ethno-Racial Self-Identification, and Prejudice Against Haitians in the Dominican Republic.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (12): 2143–2166. doi:10.1080/01419870.2018.1532097.

- Paul, Joshua. 2021. “Because for Us, as Europeans, It Is Only Normal Again When We Are Great Again: Metapolitical Whiteness and the Normalization of White Supremacist Discourse in the Wake of Trump.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (13): 2328–2349. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1922730.

- Paulino, Edward. 2016. Dividing Hispaniola: The Dominican Republic’s Border Campaign Against Haiti, 1930–1961. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Peña, Yesilernis, Jim Sidanius, and Mark Sawyer. 2004. “Racial Democracy in the Americas: A Latin and U.S. Comparison.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 35 (6): 749–762. doi:10.1177/0022022104270118.

- Ramírez, Dixa. 2018. Colonial Phantoms: Belonging and Refusal in the Dominican Americas, from the 19th Century to the Present. New York: NYU Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479850457.001.0001

- Rappaport, Joanne. 2014. The Disappearing Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial New Kingdom of Granada. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ricourt, Milagros. 2016. The Dominican Racial Imaginary. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Román, Ediberto, and Ernesto Sagás. 2017. “Who Belongs: Citizenship and Statelessness in the Dominican Republic.” Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives 9 (35): 35–56.

- Romero, Simon, and Marc Lacey. 2010. “In Disaster, Tensions Ease Between an Island’s Rivals.” New York Times, January 28. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/29/world/americas/29relief.html.

- Roth, Wendy D. 2012. Race Migrations: Latinos and the Cultural Transformation of Race. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Sagás, Ernesto. 2000. Race and Politics in the Dominican Republic. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Sagás, Ernesto. 2012. “Black – But Not Haitian: Color, Class, and Ethnicity in the Dominican Republic.” In Comparative Perspectives on Afro-Latin America, edited by Kwame Dixon, and John Burdick, 323–344. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Santos Alvarado, Orlando Nikolai. 2021. “Xenofobia y racismo hacia (y por) inmigrantes venezolanos residentes en Perú a través de Twitter.” Global Media Journal México 18 (34), doi:10.29105/gmjmx18.34-8.

- Sawyer, Mark Q., and Tianna S. Paschel. 2007. “We Didn’t Cross the Color Line, the Color Line Crossed Us.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 4 (2), doi:10.1017/S1742058X07070178.

- Sheares, Alicia. 2023. “Who Should Be Provided with Pathways Toward Citizenship? White and Black Attitudes Toward Undocumented Immigrants.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 9 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1177/23326492221125116.

- Simmons, Kimberly Eison. 2009. Reconstructing Racial Identity and the African Past in the Dominican Republic. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. doi:10.5744/florida/9780813036755.001.0001

- StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp, LLC.

- Telles, Edward. 2014. Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Telles, Edward, and Stanley Bailey. 2013. “Understanding Latin American Beliefs About Racial Inequality.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (6): 1559–1595. doi:10.1086/670268.

- Telles, Edward, and René Flores. 2013. “Not Just Color: Whiteness, Nation, and Status in Latin America.” Hispanic American Historical Review 93 (3): 411–449. doi:10.1215/00182168-2210858.

- Thornton, Brendan Jamal, and Diego I. Ubiera. 2019. “Caribbean Exceptions: The Problem of Race and Nation in Dominican Studies.” Latin American Research Review 54 (2): 413–428. doi:10.25222/larr.346.

- Torre Cantalapiedra, Eduardo. 2019. “Migración y Racismo En Internet: Análisis de Discursos Antiinmigrantes de Internautas En Prensa Digital Mexicana.” Revista Pueblos y Fronteras Digital 14: 32. doi:10.22201/cimsur.18704115e.2019.v14.401.

- Torres-Saillant, Silvio. 2000. “The Tribulations of Blackness: Stages in Dominican Racial Identity.” Callaloo 23 (3): 1086–1111. doi:10.1353/cal.2000.0173.

- Waters, Mary C., Philip Kasinitz, and Asad L. Asad. 2014. “Immigrants and African Americans.” Annual Review of Sociology 40 (1): 369–390. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145449.

- Waters, Mary C., Van C. Tran, Philip Kasinitz, and John H. Mollenkopf. 2010. “Segmented Assimilation Revisited: Types of Acculturation and Socioeconomic Mobility in Young Adulthood.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (7): 1168–1193. doi:10.1080/01419871003624076.

- Weber, Hannes. 2015. “National and Regional Proportion of Immigrants and Perceived Threat of Immigration: A Three-Level Analysis in Western Europe.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 56 (2): 116–140. doi:10.1177/0020715215571950.

- Werner, Marion. 2011. “Coloniality and the Contours of Global Production in the Dominican Republic and Haiti.” Antipode: A Journal of Radical Geography 43 (5): 1573–1597. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00903.x.

- Zabala Ortiz, Pamela. 2022. “Connectivity, Contestation, and Cultural Production: An Analysis of Dominican Online Identity Formation.” Identities 29 (3): 320–338. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2021.1927420.