ABSTRACT

On 31 January 2020 in the midst of the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China the city’s Party Secretary, Ma Guoqiang admitted in a televised interview to feeling “guilty and remorseful,” about the city government’s failures to contain the virus. In response, netizens on Weibo directed visceral abuse at Ma, an ethnic Hui Muslim, about his faith and loyalty to the party. The attacks came just months after the publication of leaked documents from national party officials calling Islam a “virus” and vowing to stop its “contagion.” Using discourse analysis of posts regarding Ma from January and February 2020, this paper examines how online discussion of Ma exemplifies Islamophobic attitudes of netizens and illuminate the exclusory ethnic politics that unfold in the process of national boundary setting in China. These findings will also illuminate how Muslims become scapegoats for crisis in non-Muslim countries, particularly those under authoritarian governance.

On 31 January 2020, as a novel coronavirus – soon to be known around the world as COVID-19 – continued to spread throughout the city of Wuhan in south central China, Wuhan Municipal Party Secretary Ma Guoqiang appeared in a nationally televised interview. Just four days prior the spread of the virus triggered a stridently enforced citywide lockdown, and the city’s mayor, Zhou Xianwang, had conceded that the city’s response was inadequate. Now, speaking candidly, Ma admitted to feeling “guilty and remorseful” about the city’s response, adding “our work has not been done well, and we have not acted decisively,” resulting in the virus spreading throughout China.

In response to Ma’s admissions, nationalist netizens flocked to the microblogging platform Sina Weibo to vent their anger at an unlikely target: Wuhan’s ethnic Hui Muslim community. Ma’s identity as Hui provided irate netizens with an easy target for their fury. One particularly lengthy and vitriolic screed posted by a netizen to Weibo began, “If you have to ask me why I hate Hui so much, it’s because my fellow Han from all over China have been hurt by them so much.” Launching into an extensive list of recent events where Hui were inferred to have caused disruption, the netizen declared “A lot of people don’t know about this even now!” Throughout the next two weeks, as the crisis in the city deepened, the abuse of Hui continued. By February 13, one netizen raged “these Hui parasites, these ‘people’ have really made China suffer this time.”

That netizens directed abuse at Ma is unsurprising. However, their extension of blame to all Hui is curious. In their targeting of Ma, netizens latched on to his ethnicity, framing his failures not just as a result of bad governance, but as attributable to his identity as a Muslim. Refracted through these logics, netizens construed Ma’s failure to contain the virus as a sign of his betrayal of China. The Hui community writ large were made into Ma’s co-conspirators – an internal enemy executing a grand plot and motivated by extremist religious ideologies.

Why did nationalist netizens target Hui ethnoreligious identities in this way, and why were Hui excluded from expressions of national solidarity in the face of the crisis? Indeed, in later stages of the pandemic, nationalist rhetoric in China shifted considerably. Rather than lashing out at internal scapegoats, netizens expressed solidarity and gratitude to emergency workers on behalf of the nation. Moreover, the target of nationalist ire shifted, as netizens looked to pin blame for China’s suffering and the global spread of COVID-19 on external forces, namely the United States. While the causes for such externalization of anger are complex, the coincidence of the global spread of the virus with a growing geopolitical rivalry between China and the US piled grievances about the virus on top of already existing animus. Further, China’s apparent containment of the virus, even as it spread widely in the US led to netizens gleefully trumpeting China’s successes and mocking the US’ failures (Singh Citation2022; C. Zhang Citation2022). Perhaps unsurprisingly, online nationalist narratives about the virus became tales of determined Chinese perseverance in the face of a deadly virus, and global antagonism.

Thus, though a number of studies have explored the impact of COVID-19 on expression of nationhood and nationalism in China, they have largely focused on the performance of national unity and remembrance after the initial outbreak subsided, or on the backlash against critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the virus spread outside of China (Zhao Citation2021; C. Zhang Citation2022). Comparatively less attention has been given to examining the inclusions and exclusions in the community of Chinese nationhood revealed by the outbreak of the virus, or explaining the understandings of Chineseness that they construct.

In the remainder of this article, I will assess how nationalist netizens making Islamophobic attacks on Ma Guoqiang and other Hui during initial outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan reveal how Muslims were excluded from Han-centric conceptions of Chinese nationhood. I contend that these attacks illustrate the ways in which globalized Islamophobic tropes merge with localized grievances to render Muslim populations as outsiders unworthy of solidarity in the minds of abusive netizens. Further, I contend that these posts illustrate the ways in which daily practices of Islamic identity performed by Hui were construed by netizens to paint Muslims as actors attempting to undermine (Han) Chinese culture and values.

Drawing on a sample of 649 posts gathered from Weibo between January 24 and 19 February 2020, I illustrate how Islamophobia intertwined with ethnic chauvinism in online abuse. By utilizing the method of constant comparative analysis (CCA) to conduct an examination of online discourse in the wake of Ma Guoqiang’s admission of his failure to contain the virus, I contend that these instances of abuse exemplify how Islamophobic tropes diffuse across national boundaries, adapt to exacerbate localized tensions, and result in Muslims frequently being branded as threats to the nation in unsettled times.

Everyday nationhood and the contagion of Islamophobia during unsettled times

In unsettled times, like those experienced during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, expressions of nationhood, especially those made in the course of daily life, take on heightened significance. The abandonment of the routines of “normal” life caused by the disruption frequently produces a sense of ontological insecurity. During these moments when calamity unmoors identities from the routines and practices that anchor them, the community of the nation frequently serves as a port in a storm for those feeling ontologically adrift (Skey Citation2010; Goode, Stroup, and Gaufman Citation2022, 63–64).

However, while displays of nationhood may provide the basis for togetherness and communal effort, they also may turn into channels for assigning blame and administering retribution to those perceived to be the cause of calamity (Skitka Citation2005). Majorities that see themselves as representative of the nation as it “ought” to be may turn aside those whom they feel disrupt normality or violate their sense of security in the community of the nation (Goode, Stroup, and Gaufman Citation2022, 78–79). Ethnic, racial and religious minorities provide activists in majority with convenient scapegoats to blame for disruption (Singh Citation2022, 107–108). This is especially true during epidemics when myths about contagion target the daily habits and lifestyles of marginalized populations, deeming them responsible for transmission. These “outbreak narratives” that pin blame on minorities, lower classes, and those in professions deemed taboo justify placing minorities under greater scrutiny and, frequently, sanction their punishment and abuse (Wald Citation2008, 13–20, 77–113). Abusers who perpetuate such harassment often latch on to everyday habits practiced by members of the supposed outgroup as the basis for their exclusion (Goode, Stroup, and Gaufman Citation2022). Discrepancies in behavior that depart from the perceived national norm may even grow to become the core of bizarre conspiracy theories that mark these “others” as foreign agents or enemies of the nation (Malešević Citation2022).

Occasionally, this othering causes nationalists to conflate outsider status with contagion itself. Indeed, findings from political psychology suggest a predictive relationship between the sentiments of disgust directed at perceived outgroups and nationalism (Gao et al. Citation2021). Exclusionary nationalist actors frequently describe outgroups as vectors for disease, often describing members of the outgroup themselves as the plague (Singh Citation2022). These claims, especially when made by prominent political figures, may find replication in daily discourse (Croucher, Nguyen, and Rahmani Citation2020).

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread, Muslims found themselves accused by Islamophobic conspiracists of either deliberately spreading the virus, or of exploiting emergency response measures for their own sinister ends. They also became the victims of ugly, anti-Muslim slurs, especially online (Rose Citation2021). Largely, these attacks came as a convergence of new fears about contagion of the virus with well-established, pre-existing Islamophobia.Footnote1 The heightened salience of “insider” and “outsider” designations may reinforce pre-existing Islamophobic tropes about Muslims, especially in majority non-Muslim spaces (Duman Citation2020; Menon Citation2023, this issue). Islamophobic rhetoric frequently posits that Muslims living in non-Muslim spaces represent potential latent threats or fifth columns. Such prejudices frame Islam as out of step with ideologies of tolerance, secularism or multiculturalism and portray Muslims as backward, parochial, and prone to extremist violence (Shyrock Citation2010; Najib Citation2021, 40). The spread of Islam frequently appears in such formulations as a threat to a perceived national way of life, threatening to subsume local culture and trample values like liberalism, secularism, tolerance and multiculturalism (Silverstein Citation2010; Cainkar Citation2011, 3; Frydenlund Citation2023, this issue; Ganesh and Faggiani Citation2023, this issue).

Placed in this essentializing framework, Muslims appear as monolithic, and uniformly threatening (Halliday Citation1999; Duman Citation2020, 437; Itaoui and Elsheikh Citation2018). Though such characterizations usually racialize Muslims – frequently rendering “Muslim” and “Arab” as essentially synonymous – the fact that Islam is a global religion whose adherents embody a wide array of racial and ethnic identities may only intensify feelings of distrust and reinforce rhetoric proclaiming Muslims a latent or hidden threat (Sealy Citation2021). These conceptions of a “Muslim World” whose inhabitants prioritize an overriding and homogenous Muslim “master status” above all other identities further reifies fears of a Muslim “other” that cannot be integrated into a societal mainstream (Cainkar Citation2011, 156; Bangstad and Linge Citation2023, this issue). In designating Muslims as “outsiders” who threaten a national way of life, Islamophobia often intersects with and inflames feelings of ethnic or national chauvinism (Frydenlund Citation2023, this issue). Islamic practices of diet or dress which diverge from those of local majorities, or a perceived allegiance to a “foreign” authority may provoke feelings of grievance or anger in those non-Muslim chauvinists who purport the supremacy of their in-group above all others (Cleemput Citation1995, 64–67; Gustavsson and Stendahl Citation2020, 450).

As another consequence, these Islamophobic portrayals justify distrust of Muslims and facilitate aggressive programs of assimilation. These constructions of Islam reify a diverse and dynamic collection of ideologies and beliefs as being represented only by a single, very conservative expression (Halliday Citation1999, 897). These homogenizations of Islam scrutinize ordinary lifestyle habits and expression of faith for signs of “extremism” (e.g. veiling, regular prayer attendance, etc.) and thus allow Islamophobes to call into question the loyalty of those who practice them (Cainkar Citation2011). Further, it allows antagonists to create dichotomies of “good” (i.e. moderate or secular) and “bad” (i.e. extremist) Muslims that are weaponized against ordinary people, demanding that they “choose a side” and demonstrate loyalty (Shyrock Citation2010, 9; Klug Citation2012; Duman Citation2020).

Such conceptions of Muslim untrustworthiness have become universalized and created a set of stereotypes about a uniquely threatening, homogenous Muslim “other.” After the attacks of 9/11 and the enactment of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), tropes about Islamic radicalism diffused across national boundaries, and combined with localized grievances. Through this process of racialization of threat, Muslim populations living in non-majority-Islamic spaces were cast as a universalized threat to security, in many cases reinforcing long-held local prejudices. As such, universalized discourses about the dangers of Islam are often intertwined with distinctively local nativist chauvinisms or ideas of racial or ethnic supremacy (Bakali and Hafez Citation2022; Hafez Citation2020).

While interactions between agents of western imperial powers and the Muslim populaces they colonized may have produced essentializing notions of a “Muslim World,” and the U.S. led GWOT may have popularized the widespread tropes that dominate current Islamophobic rhetoric, recent scholarship in human geography underlines Islamophobia as a transnational and multi-scalar phenomenon (Aydin Citation2017; Ganesh, Frydenlund, and Brekke Citation2023; Najib Citation2021, this issue). Thus, even though globalization has spread a repertoire of Islamophobic stereotypes about Muslims that are modular and easily diffused across contexts, Islamophobia also conforms to localized expression that draw on particular histories and socioeconomic dynamics (Ganesh, Frydenlund, and Brekke Citation2023, this issue).Footnote2 For instance, in Australia after 9-11, securitized rhetoric about the threats posed by terrorism have merged with longstanding xenophobia and notions of white supremacy produced by colonial immigration schemes. Thus, Australian far-right activists posed asylum seekers from Muslim majority countries as not only a danger to national values, but also potential violent extremists (Iner and McManus Citation2022).

During unsettled times, these perceived misalignments of Muslims with particular national practices may only intensify feelings that Muslims do not belong to the community of the nation, or represent a latent threat that must be excluded (Noble and Poynting Citation2010, 490). Thus, Islamophobic abuse surrounding everyday behaviors may pervade not only national, but also personal and emotional spaces, including in Muslims’ homes or online (Kozaric Citation2023; Najib Citation2021, this issue).

Pandemic and the pathology of islamophobia in China

The abuse of Hui citizens during the initial outbreak of the virus in Wuhan in early 2020 occurred amidst an already deepening climate of Islamophobia in China. Thus, the Islamophobic rhetoric voiced by netizens in response to COVID layered contemporary anxieties about contagion and societal disruption on top of long-established historical prejudices against Muslims, and Hui in particular.

The Hui are commonly referred to in popular media as “Chinese Muslims.” With a population number over 10 million as of the 2010 census, the Hui constitute the largest of China’s 10 Muslim ethnic groups.Footnote3 Many claim descent from Arab, Persian or Turkic Muslims who intermarried into Han communities upon their arrival in China as early as the 8th century, or from Chinese converts to Islam (Ha Citation2020). As such, Hui communities are geographically dispersed, and linguistically, economically, and culturally heterogenous (Stroup Citation2022). Indeed, as one of the most widely dispersed of China’s ethnic groups – Hui neighborhoods exist in most of China’s major urban centers – the Hui are one of China’s most prominent minority communities, frequently interacting with and living alongside the majority Han. Unlike other Muslim ethnic groups in China, Hui do not speak an ethnic language, or exhibit obvious ethnic or racial differences from the majority Han (Gladney Citation1991). Consequently, many Han regard Hui as “familiar strangers,” who are culturally proximate and essentially Hanified (Lipman Citation1998).

Even with such a long-established presence within the country, much of the suspicion and disdain for Muslims expressed in contemporary Chinese society finds roots in comparatively recent history. The violent conflicts between communities of Muslims and the armies of the Qing state in the 18th and 19th centuries – commonly referred to as the “Muslim Rebellions” – have been especially consequential in shaping popular attitudes about the Hui (Kim Citation2004). Despite the party-state’s attempts to reposition the Hui as a patriotic, “model” minority, a lingering historical mistrust born of these conflicts pervades relationships between Hui and the majority Han (McCarthy Citation2009; Stroup Citation2021).

Physical separation reinforces these prejudices. Urban Hui enclave communities have historically centered around mosques and often stand out from surrounding areas (Gaubatz Citation2002). In many cities, Han infrequently visit these spaces, and often perpetuate stereotypical notions that they are poor, backward, or unwelcoming to non-Muslims (Gillette Citation2002, 22–29; Miao Citation2020; Stroup Citation2022, 43–50). Taken together, these historical legacies and physical segregation between Han and Hui perpetuate the exclusion of Hui. Despite sharing many linguistic and cultural ties, many Han continue to regard Hui as “others,” especially those who practice their religious faith in a more overt manner (e.g. wearing religious garments or routinely attending prayer services).

In the years following the 9/11 attacks in the United States, reports of violent acts perpetrated by Islamic extremists abroad and a spate of violent incidents – usually between Han and Uyghur Muslims – have intensified these fears. Tropes about Islam perpetuated by the US’ Global War on Terror have been adopted in China both at popular and official levels, heaping increased scrutiny – and often abuse – onto domestic Muslim communities (Luqiu and Yang Citation2020; Roberts Citation2020). Those Muslims who chose to display visible markers of their Islamic identity as well as those Muslim intellectuals who deeply engage with Islamic culture and history, have frequently been branded as “two-faced” (liangmianren), implying that they secretly harbor allegiance to a hostile foreign power and are intent on subverting China’s security (Byler Citation2022; Miao Citation2020; Xie and Liu Citation2021). These caricatured accounts which depict Muslims as prone to extremist violence reanimate old historical stereotypes about the Hui rooted in the rebellions during the late Qing. The spread of these narratives has been especially consequential in shaping popular attitudes among Han about the Hui.

Communications from the Chinese party-state also contribute to this securitization of Muslims.Footnote4 Addresses by Xi at the start of the so-called “People’s War on Terror” launched in the wake of attacks in the cities of Ürümchi and Kunming in April 2014 described Islam in the language of disease and contagion. Grimly, Xi pronounced “in some places, the influence of religious extremism has gained control to the point where our needles cannot penetrate and medicine cannot be injected” (Xi Citation2014). Later, in May, while addressing the Second Central Xinjiang Work Forum, Xi used even more emphatic language to describe Islam as a form of disease as he spoke of the need to “strengthen the body and the mind” against religious extremism with the “medicine” of correct education about Chinese culture. Without such intervention, Xi expressed fear that “violent terrorist activities will continue to replicate and multiply like cancer cells” (Xi Citation2014).

With the subsequent declaration of a “People’s War on Terror” in Xinjiang, the party-state followed longstanding practices of using the language and methodology of pathology to treat “targeted people” in need of intervention (zhongdian ren). The implementation of these policies effectively identified aspects of everyday Islamic practice as symptoms of mental illness. This diagnosis was used to justify measures taken to effect a “quarantine” of Muslims considered “deviant” as necessary to prevent a contagion – often accompanied by ideological re-education through labor (Grose and Leibold Citation2022).

While this suspicion and targeting of Muslims resulted in unfathomable levels of surveillance and repression by the party-state in Xinjiang, the ripple effects of this Islamophobia have also been felt in Hui communities nationwide. A sweeping campaign of Sinicization has altered the architecture of mosques, stripped Arabic text off signs, and closed opportunities for religious education in the name of fighting off “Arabization” of China’s public spaces (Gansu sheng huanjing baihu ting Citation2018; Stroup Citation2022, 157–166). Further, as the party-state enacted these measures, Hui across China reported an upsurge of harassment, both online and in person (Ho Citation2010; Luqiu and Yang Citation2020). Indeed, Chinese social media platforms saw a rise in the prominence of so-called muhei (Muslim haters) following a spate of violent incidents involving Muslims in Xinjiang in 2013 and 2014. These users primarily used platforms like Weibo and WeChat to mock China’s Muslim communities, brand all Muslims as terrorists, or to rail against a perceived tide of “Arabization” or “halalifcation” that sought to overwhelm and destroy Han identity (de Seta Citation2021).

Placed against this backdrop of growing Islamophobia, Ma’s admission of failure to contain COVID sparked an enormous backlash online. Though some netizens made passing note of Ma’s identity as Hui after his appointment to the post of Party Secretary of Wuhan – an overwhelmingly Han city – in 2018, his ethnicity garnered little attention before the outbreak.Footnote5 However, with the spread of the virus, Ma’s Hui identity became a target for abuse. In a context where organs of the party-state referred to Islam with metaphors of disease and painted daily behaviors associated with the practice of faith as signs of growing contagion, Ma’s identity as Hui became the subject of wild conspiracy theory, and left him – and other Hui – exposed to vitriolic and exclusionary Islamophobic abuse.

Methodology

To assess the ways in which Islamophobia was expressed during the initial outbreak of the virus, I sampled posts collected from the social media site Sina Weibo, a microblogging platform, made between January 24 and February 19, 2020. This period captures the period between the initial announcement by Chinese health authorities that the COVID-19 virus was transmissible person-to-person, and Ma Guoqiang’s eventual sacking from his post as Party Secretary for the city of Wuhan. To limit data analyzed to relevant posts, I employed targeted keyword searches for three terms: Ma Guoqiang (马国强), Hui (回族), and Islam (伊斯兰). In all, I gathered a sample of 649 posts.Footnote6 This collection is by no means an exhaustive or universal sample of posts on the subject. The sample is, however, broadly representative of the discussion unfolding on Weibo in the moment.

Weibo serves as China’s major online platform for public deliberation and political discussion (Lu, Pan, and Xu Citation2021). Similarly, online forums like Weibo have served as echo chambers where hardcore nationalists develop insular and extreme understandings of belonging and nationhood (Leibold Citation2010; C. Zhang Citation2020). Thus, though its user base ought not be considered as broadly representative of China’s general public, it does still present a useful means for finding the “edges of the nation” and gaining greater insight about how such extreme conceptions of nationhood contribute to the way that national boundaries are formulated and contested (Fox Citation2017).

To analyze these posts, I used the software program NVivo 12 to follow the Constant Comparative method of coding (Glaser and Strauss Citation2009). This method seeks to draw out grounded theory from textual data via an inductive, iterative, qualitative coding process. In all I conducted three stages of coding: an initial open coding stage, a secondary axial coding stage, and a final stage in which I synthesized categories of codes to produce an overarching theoretical finding.

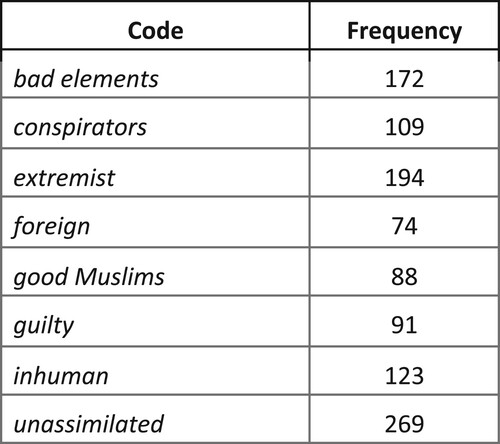

During the open coding phase, I coded all lines of relevant text in the dataset until a point of coding saturation. In all, this phase produced 64 discrete codes. After this exhaustive coding stage, I employed a second, axial phase meant to establish categories among the initial codes. In this phase, I examined the relationships between the codes and placed them into an exclusive, equivalent and exhaustive typology. In all, I produced 8 axial-level codes during this second stage (see below). For the final coding stage, I assessed the relationship between the categories of codes produced during axial coding, and described the relationship between them.

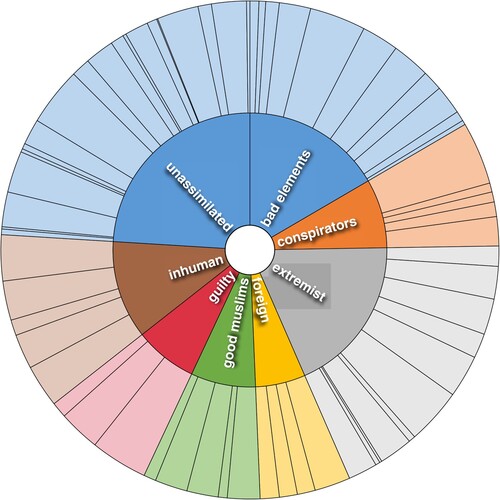

Figure 1. Typology of characterizations of Muslims on Weibo during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan (January-February 2020).

After completing this qualitative coding process, I conducted two forms of analysis. First, I used basic cross tabulations to discuss the frequency of recurrence for particular codes within the text. Following this analysis, I conducted a critical discourse analysis of the posts to explore how they constructed Hui and Muslim identities and barred them from inclusions in netizens’ conceptions of Chinese nationhood.Footnote7 I contend that the characterizations of Hui on Weibo in the midst of the outbreak of COVID-19 painted them as dangerous outsiders who breached perceived national solidarities, and therefore attempted to exclude them.

Typologizing Islamophobic posts during COVID-19

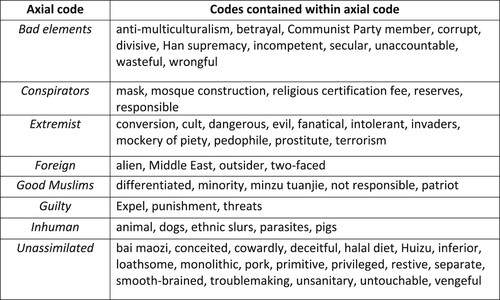

As discussed in the previous section, Weibo comments about Ma Guoqiang, and about Hui as a group, during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan fell into 8 categories (see below; for a complete code book with descriptions of codes produced during open coding, see Appendix A). These categories illustrate how Islamophobic netizens used both daily, localized interactions with Hui as well as transnational stereotypes about Muslims to construct Hui as “others” to be excluded from the community of the nation.

The categories produced during the axial coding stage illustrate how the Hui’s identity as Muslims led others to treat them as outsiders, or as latent threats to Chinese nationhood. These characterizations reflect both global Islamophobic tropes about Muslims, as well as locally held prejudices rooted in China’s past.

For example, the category bad elements comprises codes that accuse Hui of violating China’s civic values.Footnote8 These codes not only cast Ma Guoqiang as incompetent and corruptly working to give his Hui co-ethnics favourable treatment, they also suggest Ma’s identity as a Hui official represented a violation of China’s official state secularism. The category unassimilated contains posts that express resentment at the perception that Hui refuse to assimilate into mainstream (read as Han) society. These posts include gripes about Hui observing a halal diet or wearing religious clothing, but also contain expressions of anger from netizens who perceived Hui as flaunting the status as an ethnic minority in arrogant or condescending ways. These two categories both reflect localized tensions exposed by that pandemic.

However, other categories showcase the way that global Islamophobic tropes have diffused into China. The category extremist contains posts that characterize the Hui as intolerant religious zealots or as harbouring plans to Islamize China. The most virulent of these posts depicted the Hui as in league with radical Islamic terrorism, or groups like the Islamic State. Similarly, reflecting global Islamophobic tropes about the inherent untrustworthiness of Muslims, the category foreign contains posts that disavow the Hui as Chinese, suggesting instead that they are “two-faced” agents of a foreign power, or that they should return to the Middle East (zhongdong). The category conspirators contains numerous posts about secretive plots held by Hui to undermine China – like storing only halal meat in disaster reserves – that the pandemic exposed. Even posts that attempt to defend Muslims, coded under the category good muslims, attempt to separate Huiness from Islam, falling into Islamophobic tropes that “good” Muslims are secular, assimilated, and moderate.

Finally, these categories also include a number of posts which advocate more violent exclusions. The category inhuman contains numerous posts which use ethnic slur to dehumanize Hui, rendering them into animals, or indeed as a kind of virus in and of themselves. The category guilty contains those posts from netizens who pronounced the Hui responsible for the spread of the pandemic and proposed coercive or violent remedies (forcible expulsion or worse) as punishment. It also contains those posts which threaten or intimidate Hui as a response to their perceived betrayal of the nation. A breakdown of these categories may be seen in and , below.

While this analysis illustrates the frequency and distribution of the Islamophobic abuse unleashed by the outbreak of COVID-19, understanding how these categories reflect the othering and exclusion of Hui – as Muslims – from inclusion in the community of Chinese nationhood requires analysis of the posts at a more granular and in-depth level. A critical discourse analysis which assesses how these characterizations fit together reveals how Islamophobic netizens evoke a Han-centric core of Chinese nationhood to exclude and scapegoat Hui during the crisis.

Discourse analysis of sampled posts

Many netizens’ posts asserted that being Hui – and ostensibly Muslim – should have disqualified Ma from party membership, let alone a position of leadership. “Muslims can’t become party members, right?” asked one adding “how did he even get in?”Footnote9 Others were more demonstrably angry. One post singled out Ma’s religion as specifically incompatible with governance, remarking, “Msl shouldn’t be able to be officials (internet abbreviation for musilin, Muslim).”Footnote10 Another netizen, in excoriating Ma, declared “Party members and officials’ believe in Marxist-Leninism, atheism and socialist thought; They believe in serving the people rather than being ignorant religious believers!” Continuing on, the post chastised those who defended Ma, declaring “National unity is not a veil for covering up the problems with Islam!”Footnote11

While these decried Ma’s status as a Muslim in an oblique sense, some went further, specifying that Ma’s Muslimness led him to corruption on behalf of co-religionists, usually at the expense of Han. Accusing Ma of abusing his powers as party secretary, one netizen moaned, “after taking office you repaired mosques for your people, but what are we Han to do?”Footnote12 Often, these detractors also fumed that Ma’s status as a privileged minority placed him beyond official reproach. Exemplifying such grievances, one netizen seethed, “They use relevant policies to be arrogant and domineering, and nobody can oppose.”Footnote13

Such charges not only painted Ma’s corruption and incompetence as primarily responsible for the virus, but reasoned that Ma’s loyalty was first and foremost to other Muslims, at the cost of public order. These traits, posts asserted, were intrinsic not just to Ma but all Hui. These types of assertions reframed complaints about perceived corruption and good governance into specifically ethno-religious concerns that placed Ma’s Hui identity at the forefront. One netizen’s rant exemplified this blame: “I’m just waiting for the central government to punish the Hui municipal leader whose dereliction of duty caused this shocking global pandemic and indirectly killed people.”Footnote14

These notions about Ma as corrupt and the Hui as beneficiaries generated numerous accusations of pre-meditated conspiracy. In response, netizens levied accusations of deliberate malfeasance related to the outbreak of the virus, and disaster relief by Ma in collusion with other Hui. Prominent among these were wild and unsubstantiated conspiracy charges that Ma had wasted the city’s public funds to build mosques.Footnote15 In response to a post claiming that Ma prioritized appeasing Muslims before public good, one netizen groaned, “After Ma Guoqiang took office, he built such a big, beautiful mosque. Isn’t that enough to prove himself?”Footnote16 These posts railed against the perception that, despite being a clear minority, Muslims dictated Ma’s governance agenda. Others replied to these rumors with calls for retribution. “Turn the mosques into mobile field hospitals!” cried one netizen.Footnote17

Other rumors suggested that Ma had abused his power in the procurement of emergency supplies. A number of posts claimed that Ma embezzled medical supplies, ostensibly to hoard for Hui to use. Many framed these actions as stealing from the people of Wuhan. One netizen fulminated at Ma, “can you please explain exactly why you’ve taken the people of Wuhan’s masks?”Footnote18

An even more provocative conspiracy theory alleged that Ma had only purchased halal meat for the city’s food reserves to be distributed after Wuhan declared a city-wide lockdown. In so doing, netizens replicated a common global Islamophobic trope that Muslims use halal food to subjugate non-Muslims, and force them to consume meat that otherwise might be considered unclean or taboo (Anand Citation2005, 207–208; Brekke Citation2021). Numerous posts from Han netizens spread this rumor, proclaiming that Ma sought to discriminate against non-Muslims – or worse, forcibly convert them by withholding food. Responding to this rumor one netizen pleaded, “can I ask what the governments measures are? Are they trying to starve us to death?”Footnote19

At the thought of being forced to eat halal food, some netizens expressed disgust. Responding angrily at the thought of the idea that non-Muslims would be able eat halal food without issue, one netizen fumed, “atheists don’t just eat anything. For example, to many atheists halal food is a shit-tainted food. How are atheists supposed to eat things that are tainted with shit?”Footnote20 Others framed their refusal on the grounds that their rights had been violated. One defiantly protested that, “we Han do not agree to eat halal food,” before adding “I am an atheist, and I have the right to refuse to eat halal food.”Footnote21 Such vehement refusal to eat halal highlights the degree to which netizens marked Islamic practice as suspicious.

In each case, the rumors of Ma’s malfeasance were posed not just as normal corruption, but as deliberate plots specifically meant to benefit Hui at the expense of others. Some conspiracy-addled netizens linked this hearsay to historical events, suggesting continuation of chaos and disruption wrought by the Hui. One incredulous netizen spouted “This is exactly what you get when you let a Hui become party secretary! Inaction and invisibility!”Footnote22 The oft repeated slur, “if the country is in trouble, the Hui must be causing chaos” (guo you nan, Hui bi luan) was echoed by a number of netizens gesturing at this imagined history of Hui sabotage and disruption.Footnote23

Conspiracy theories like these roused a number of grievances against and anxieties about Hui, particularly that their daily practices related to Islam made them unwilling or unable to assimilate into Han-centric conceptions of Chineseness. Chauvinistic netizens expressed their resentments about the perceptions that Hui flaunted privilege as one of China’s recognized ethnic minorities and refused to integrate with Han. These posts marked Hui as arrogant, or as provocative troublemakers who – as a privileged minority – the party-state dared not reproach. As one netizen sniped, “The Hui are the second most populous minority group, so everyone has to be polite.”Footnote24

Numerous posts made derogatory statements about Hui daily practices of identity – particularly about diet or dress. Honing in on Islam’s treatment of pigs as haram (ritually unclean), aggressive netizens heaping abuse on Hui users frequently made menacing threats using pork or lard. In response to one Hui user asking for tolerance of Islamic dietary habits, a netizen posted “Eating pork is my religion, and I love eating pig heads the most.”Footnote25 Another quipped, “Won’t all of you big Hui just please fuck off? Drink two mouthfuls of lard and settle down.”Footnote26 In eating differently, or maintaining daily lives consistent with Islamic practice, Hui were deemed not just as outsiders, but as intolerant and actively threatening to Chinese national identity.

Others imagined a more sinister intention to Hui actions. For some netizens, Hui observing religious practice was not merely a sign of ethnic or cultural preservation, but an indication of extremist ideology. Islam, netizens suggested, represented a hostile ideology holding Hui captive. “Don’t scold (the Hui) so severely,” one netizen posted, “It’s just that the Muslims among them are holding them captive. After all, Muslims have a several thousand year history of kidnapping ethnic groups.”Footnote27

Likewise, numerous posts expressed fear that, via empowered figures in the party like Ma, Hui sought to forcibly convert or Islamize China. “Some people just want to impose their faith on a minzu (usually translated as “nationality” or “ethnic group”),” remarked one netizen.Footnote28 Another darkly forecasted “Green things (lüse dongxi) like to bind the nation to faith so that afterward they can have religion without having a country.”Footnote29 In such instances, these posts suggested that Ma’s actions were not merely the result of poor governance, incompetence, or corruption, but instead a deliberate plot to undermine China’s sociocultural and religious identities. In this sense, netizens framed their harassment of Muslims as a defense of Chinese – imputed to be Han – tradition against invaders from outside who sought to dominate China.

Uglier expressions of this sentiment linked Hui to international terrorism. One netizen exemplified this by using a bomb emoji in the place of the word “Islam” in posts (see , below).Footnote30 Another casually slurred “Everyone knows all msl are terrorists.”Footnote31 Some netizens made more specific links to extremist groups. One post, making a pun off of Ma’s given name (“strengthen the country,” Guoqiang 国强), questioned “Ma Guoqiang, what country are you trying to make stronger? Is it your Islamic State?”Footnote32 In these formulations, Hui were not just seen as deserving of exclusion from the bonds of nationhood, they were seen as literal adversaries who sought to harm the Chinese state.

Figure 4. Post from a netizen using a bomb emoji in place of the word “Islam.” The entire post reads “(bomb) faith”.

This perceived overriding allegiance to Islam led many netizens to tear down the Hui as not really being from China. Occasionally, these posts implied Hui held loyalties outside of China by implying they were “two-faced people.” Numerous posts taunted Hui for their perceived foreignness, insisting they should return to some unspecified homeland in the Middle East. As one netizen expressed, succinctly, “Hui ought to just fuck off back to the Middle East, China doesn’t like you.”Footnote33

Finally, many posts simply dehumanized Hui, describing them as animals or lower forms of life. In one example, a Han netizen smeared Hui as subhuman due to their religious faith, perhaps echoing the Marxist axiom that religion is the “opiate of the masses.” The netizen posted, “religion is an anaesthesia for lowly animals, and the Chinese people (huaxiazu) are an elevated race, so they don’t cultivate low-end things like religion.”Footnote34 On the basis of Hui beliefs as Muslims, the netizen had declared them to not only be outside of inclusion as Chinese people, but not to be human altogether.

Likewise, in numerous examples, netizens weaponized Islam’s regard of pigs as ritually unclean to attack Hui. Targeting a Hui commenter who had defended Ma, one netizen posted “Tonight I’m going to braise (hongshao) your pig ancestors.”Footnote35 One netizen slurred, “Look at all you green pigs (lüzhu). It’s disgusting.” Some merely posted out strings of pig emojis in response to posts about Ma or as a retort to Hui netizens defending their faith (see below).

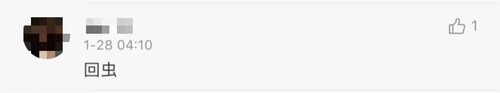

In some of the most extreme cases, netizens dehumanized Hui using the language of disease, itself. “Muslims are human cancers, there’s no need to respect them” posted one.Footnote36 Others, in describing Hui people, replaced the character for Hui (回) with a homonym meaning intestinal parasite (Hui, 蛔) yielding slurs like “Hui parasites” (For example, Huizu 蛔族, or Huihui 回蛔, a parody of the older ethnonym Huihui 回回) or Hui worms (Huichong 蛔虫 or 回虫) (See , below). One thundered, “You Hui parasites should fuck off back to the Middle East. What are you even doing on Chinese soil?”Footnote37 In some particularly grim examples, netizens speaking of Hui as a disease combined these degrading slurs with threats of egregious, targeted violence. “We just want to give you Hui parasites some medicine, and after that build some showers for Hui,” menaced one post, in language that seemingly alluded to the genocidal murders of Jews during the Holocaust.Footnote38

In using these dehumanizing slurs, netizens cast Hui as an invasive parasite, and Islam as another kind of virus whose contagion endangered China’s security and prosperity.Footnote39 Far from including the Hui in a community based on national solidarity and shared Chineseness, such abusive language thoroughly excluded them, even marking them out as adversaries or, in extreme cases, as targets for eradication.

Even those who defended Hui usually did so by attempting to separate Huiness from Islam. A handful of Hui netizens attempted to disentangle religious and ethnic identities by suggesting that many Hui did not practice Islam. For instance, one Hui netizen who attempted to disassociate themselves from Ma Guoqiang commented “Hui are not the same as Muslims, thanks. Also, Hui have nothing to do with mosques.”Footnote40 This type of distancing the community from perceived religious fanaticism may stem from a keen awareness of where the “red lines” lie in online discourse – especially for Muslims. Knowledge of potential party-state surveillance targeting “extremist” discourse (i.e. that which falls outside of bounds deemed permissible by censors) may lead to carefully manage online communication to avoid trouble, a process Jing Wang (Citation2019) calls “guanli (self-management).” Other, largely Han, netizens pointed to specific behaviors – usually overtly Islamic habits of dress or diet – which distinguished “good” Hui from “bad” Muslims. Singling out Hui who observed Islam’s taboo on pork as nefarious, one netizen contended, “By the way, the Hui who eat pork are good people.”Footnote41

In drawing these distinctions about “good” Hui, these netizens ultimately reinforced ideas about the intrinsic threat of Islam or the incompatibility of Islamic practice with normal, moderate or reasonable lifestyles. A Hui netizen’s attempt to educate an Islamophobic netizen spreading rumors about Ma trying to Islamize society by forcing people to eat halal products illustrates this. “You’re mistaken,” the user began. “Ethnicity isn’t the same as religion, and (Ma) is seeking gain for religion. There are also many Hui compatriots who don’t believe in religion, and they aren’t required to eat beef blessed by an imam.”Footnote42 Such claims belie the Han-centered articulation of nationhood from which Muslims are excluded – only those Hui who embraced secularism and abandoned Islamic practices were considered trustworthy.

Conclusions

The deluge of online abuse targeted at Mao Guoqiang and other ordinary Hui people in the wake of the outbreak of COVID-19 offers several lessons about the content of everyday national identity in times of crisis and the diffusion of repertoires of Islamophobic tropes.

First, such vicious harassment reveals the ways in which the crisis magnified existing prejudices concerning outwardly Islamic habits and practices. As such it provides a revealing demonstration of how daily expressions of nationhood gain increased significance during times of crisis, and in turn, how these practices may be cited as grounds for exclusion or scapegoating of supposed outgroups by nationalist activists. The prominence of bigoted posts citing habits of daily dress, consumption and religious observance as markers of foreign extremism illustrate how such overt or visible markers of Muslimness breached netizens’ perceived norms concerning expressions of Chineseness. Frustration that Hui might seek accommodation for their religious faith in times of crisis, or anger at an alleged unwillingness to assimilate or adopt Han practices rendered the Hui as aliens in the eyes of chauvinist netizens. Casting Hui as foreign – or indeed in the most virulent cases as inhuman – on the basis of their Muslimness and labeling them primarily responsible for the upending of normality highlights the nationalists’ belief that Islam and Muslims are incompatible with Chinese identity.

Even those posts defending the Hui emphasized their otherness by attempting to divorce them from Islam. In demanding that abusers unlink Huiness and Muslimness defenders reinforced Islamophobic tropes about the latent threat of Islam and the duplicity of pious Muslims. By highlighting the existence of “good” (assimilated) Muslims – namely those who didn’t eat halal food, wear religious clothing or outwardly practice their faith – netizens affirmed the idea that observance of Islam and trustworthiness as members of a Chinese national community could not co-exist.

In extreme cases, these depictions used the language of contagion and imagery related to the virus to describe the Hui themselves, rendering them not just as scapegoats responsible for the problem, but as a manifestation of the crisis itself – a disease to be eradicated. The posts thus present examples of how epidemics allow nationalist actors to characterize destabilization of the perceived national norm as being itself a kind of plague. In these conceptions, those who violate what nationalists believe the nation ought to be, become themselves manifestations of disease to the nationalists who abuse them and their outward otherness a sign of contagion.

Finally, the abuse directed at Ma and other Hui also furnishes lessons about how times of crisis facilitate the transnational diffusions of Islamophobic frames. Those who harassed Ma and other Muslims on Weibo following the outbreak of the virus combined tropes derived from the global context – often tied to the Global War on Terror – with nationalized prejudices rooted in historical events – such as the so-called “Muslim Rebellions” of Northwest China in the 18th and 19th centuries – and local grievances about corruption and favoritism – such as the prominent repair of local mosques. In doing so, abusers imagined grievances on multiple scales – international, national, local and personal – often simultaneously.

Likewise, netizens’ fervor in connecting vague and globalized stereotypes about Muslims to localized tensions – like corruption or resentment of perceived minority privilege – exhibits how easily Islamophobic tropes about the universality of the duplicity of Muslims – and the danger they pose to national values – diffuse and adapt to fit particular contexts. Moreover, in construing local grievances as connected to larger frames about religious extremism, the posts display how Islamophobic rhetoric about “latent” threats effectively prohibit Muslims from integrating or finding acceptance in communities in which they are not majorities by constantly moving the goal-posts.

Rhetoric from Xi and others which asserts the need for Sinicization of Islam, and urges Muslims to conform to state-approved expressions of identity only further reinforce the idea that one becomes a “good” Muslim via assimilation and abandonment of overtly Islamic identity markers. As such, official discourse compounds and intensifies exclusions. If the party-state’s linkage of foreign Islamic practices with extremism portrays all but those secularized Hui as suspect, and results in seemingly trivial matters of everyday dress, diet and speech as outside the norm. When even such small matters become construed as signs of disloyalty by abusers, inclusion in expressions of national solidarity is unattainable.

The globalizing frames that attribute any localized events to conflicts involving ideologies of extremism and international networks of violent or fanatical actors suggest why, in non-Muslim majority communities in times of crisis, Muslims are often among the first targeted for abuse as alien “others,” made into scapegoats for problems that threaten the nation, and excluded from expressions of national solidarity.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Iselin Frydenlund (University of Oslo), Torkel Brekke (Oslo Metropolitan University), Bharath Ganesh (University of Amsterdam), Pratiksha Menon (University of Michigan), David Tobin (University of Sheffield), Hannah Theaker (University of Plymouth), Chenchen Zhang (University of Durham), Guangtian Ha (Haverford College) and Tao Wang (University of Manchester) for their comments and assistance while writing and revising this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Islamophobia is a widely contested concept (See, for instance discussion in Halliday Citation1999; Bleich Citation2012; Sealy Citation2021). I will follow Najib’s (Citation2021, 12) definition of Islamophobia as “spatially pervasive form of anti-Muslim racism that occurs at various interrelated spatial scales (globe, nation, urban, neighbourhood and body (and mind)) and whose contours, effects, intensity and functioning vary accordingly.”

2 Torkel Brekke’s (Citation2021) comparative study of Islamophobia has explored how multicultural environments provide fertile ground for the cultivation of Islamophobic sentiments centered around localized grievances. See; Brekke Citation2021.

3 Of China’s 56 recognized ethnic groups, 10 are predominantly Muslim. Besides the Hui, China’s other Muslim minority groups include the Turkic Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Salars and Tatars, as well as Tajiks, and the Mongolic-speaking Dongxiang and Bonan. In contrast to the Hui, these communities usually speak a non-Chinese language, and live in a concentrated ethnic homeland. Many have links to cross-border co-ethnics elsewhere in Central Asia. For further information regarding population figures, see, National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (2013), “Sixth National Population Census of the People’s Republic of China, 2010,” Beijing.

4 These speeches were leaked as part of the collection of documents that has become known as the “Xinjiang Papers.” These documents have been authenticated by Adrian Zenz, James Milward and David Tobin. See Zenz Citation2021.

5 See, for instance: https://weibo.com/2865878802/GqP3B2oO6?refer_flag=1001030103_.

6 Due to the dynamic and responsive nature of censorship of posts on Weibo and other Chinese social media platforms, and the immediacy of the need to make a record of posts before they were taken offline, I was unable to archive posts. Instead, I was forced to rely on screenshots taken from my smartphone. For further discussion of censorship on Chinese social media platforms, see King, Pan, and Roberts Citation2013.

7 For more on critical discourse analysis, see Mullet Citation2018.

8 The term “bad elements” is derived from “huai fenzi” an emic label used during the Mao era to describe those deemed counterrevolutionary or in opposition to the party-state; see, Jian, Song, and Zhou Citation2006.

9 Post 20-004-1-27.

10 Post 43-041-2-16.

11 Post 71-002-2-1.

12 Post 99-007-2-2.

13 Post 38-015-1-29.

14 Post 52-019-1-25.

15 During Ma’s tenure, the Jiang’an Mosque did begin to undergo a process of relocation, overseen by the United Front Work Development. However, information regarding these procedures suggests that they were authorized prior to Ma’s tenure in the leadership. See, The United Front Work Department of the CPC Wuhan Municipal Committee Citation2020.

16 Post 98-001-2-15.

17 Post 22-003-2-11.

18 Post 46-008-2-08.

19 Post 21-008-1-25.

20 Post 07-038-1-29.

21 Post 88-002-1-17.

22 Post 49-006-1-26.

23 Post 90-001-1-25.

24 Post 27-014-1-27.

25 Post 54-002-1-25.

26 Post 40-002-2-01.

27 Post 43-038-1-26.

28 Post 46-012-2-01.

29 Post 70-007-1-26.

30 Post 74-011-2-10.

31 Post 48-001-1-27.

32 Post 20-005-2-01.

33 Post 38-010-1-25.

34 Post 17-003-2-10.

35 Post 38-019-2-14.

36 Post 53-001-1-25.

37 Post 43-010-1-25.

38 Post 46-020-1-27.

39 The notion of humans as possessing liminal bodies that may be construed as filthy because of understandings of cultural uncleanliness or impurity has been explored in previously in religious studies. See, for instance, Turner and Turner Citation1978; and Douglas Citation2003.

40 Post 98-001-2-15.

41 Post 67-005-2-05.

42 Post 40-005-1-30.

References

- Anand, Dibyesh. 2005. “The Violence of Security: Hindu Nationalism and the Politics of Representing ‘the Muslim’ as a Danger.” The Round Table 94 (379): 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358530500099076.

- Aydin, Cemil. 2017. The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bakali, Naved, and Farid Hafez. 2022. “Introduction.” In The Rise of Global Islamophobia in the War on Terror, edited by Naved Bakali, and Farid Hafez, 1–16. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Bangstad, Sindre, and Marius Linge. 2023. “Qur’an-burning in Norway: Stop the Islamisation of Norway (SIAN) and far-Right Capture of Free Speech in a Scandinavian Context.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268168.

- Bleich, Erik. 2012. “Defining and Researching Islamophobia.” Review of Middle East Studies 46 (2): 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2151348100003402.

- Brekke, Torkel. 2021. “Islamophobia and Antisemitism Are Different in Their Potential for Globalization.” Journal of Religion and Violence 9 (1): 80–100. https://doi.org/10.5840/jrv202142689.

- Byler, Darren. 2022. “Two-Faced: Turkic Muslim Camp Workers, Subjection, and Active Witnessing.” In The Xinjiang Emergency: Exploring the Causes and Consequences of China’s Mass Detention of Uyghurs, edited by Michael Clarke, 154–180. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Cainkar, Louise A. 2011. Homeland Insecurity: The Arab American and Muslim American Experience After 9/11. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Cleemput, Geert van. 1995. “Clarifying Nationalism, Chauvinism, and Ethnic Imperialism.” International Journal on World Peace 12 (1): 59–97.

- Croucher, Stephen M., Thao Nguyen, and Diyako Rahmani. 2020. Prejudice Toward Asian Americans in the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Effects of Social Media Use in the United States.” Frontiers in Communication 5 (June): 39.

- de Seta, Gabriele. 2021. “The Politics of Muhei: Ethnic Humor and Islamophobia on Chinese Social Media.” In Digital Hate: The Global Conjuncture of Extreme Speech, edited by Sahana Udupa, Iginio Gagliardone, and Peter Hervik, 162–184. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Douglas, Mary. 2003. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. New York: Routledge.

- Duman, Didem Doganyilmaz. 2020. “Religious Identities in Times of Crisis: An Analysis of Europe.” In Routledge International Handbook of Religion in Global Society, edited by Jayeel Cornelio, François Gauthier, Tuomas Martikainen, and Linda Woodhead, 432–444. London: Routledge.

- Fox, Jon E. 2017. “The Edges of the Nation: A Research Agenda for Uncovering the Taken-for-Granted Foundations of Everyday Nationhood.” Nations and Nationalism 23 (1): 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12269.

- Frydenlund, Iselin. 2023. “Theorizing Buddhist Anti-Muslim Nationalism as Global Islamophobia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268209.

- Ganesh, Bharath and Nicolò Faggiani. 2023. “The Flood, the Traitors, and the Protectors: Affect and White Identity in the Internet Research Agency’s Islamophobic Propaganda on Twitter.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268180.

- Ganesh, Bharath, Iselin Frydenlund, and Torkel Brekke. 2023. “Flows and Modaliities of Global Islamophobia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268192.

- Gansu sheng huanjing baihu ting. 2018. Linxiazhou Huanbaoju Quanmian Guanche Luoshi Quanzhou Yisilanjiao Gongzuo Huiyi Jingshen. Lanzhou: Gansu sheng huanjing baihu ting. http://www.gsep.gansu.gov.cn/info/1003/50883.htm (甘肃省环境保护厅).

- Gao, Shuqing, Hao Chen, Kaisheng Lai, and Weining Qian. 2021. “Predicting Regional Variations in Nationalism with Online Expression of Disgust in China.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (May): 564386.

- Gaubatz, Piper Rae. 2002. “Looking West Towards Mecca: Muslim Enclaves in Chinese Frontier Cities.” Built Environment (1978-) 28 (3): 231–248.

- Gillette, Maris Boyd. 2002. Between Mecca and Beijing: Modernization and Consumption Among Urban Chinese Muslims. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Gladney, Dru C. 1991. Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 2009. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New Brunswick: Aldine.

- Goode, J. Paul, David R. Stroup, and Elizaveta Gaufman. 2022. “Everyday Nationalism in Unsettled Times: In Search of Normality During Pandemic.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.40.

- Grose, Timothy A., and James Leibold. 2022. “Pathology, Inducement, and Mass Incarcerations of Xinjiang’s ‘Targeted Population’.” In The Xinjiang Emergency: Exploring the Causes and Consequences of China’s Mass Detention of Uyghurs, edited by Michael Clarke, 127–153. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Gustavsson, Gina, and Ludvig Stendahl. 2020. “National Identity, a Blessing or a Curse? The Divergent Links from National Attachment, Pride, and Chauvinism to Social and Political Trust.” European Political Science Review 12 (4): 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773920000211.

- Ha, Guangtian. 2020. “Hui Muslims and Han Converts: Islam and the Paradox of Recognition.” In Handbook on Religion in China, edited by Stephen Feuchtwang, 313–337. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Hafez, Farid. 2020. “Unwanted Identities: The ‘Religion Line’ and Global Islamophobia.” Development 63 (1): 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-020-00241-5.

- Halliday, Fred. 1999. “‘Islamophobia’ Reconsidered.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22 (5): 892–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198799329305.

- Ho, Wai-Yip. 2010. “Islam, China and the Internet: Negotiating Residual Cyberspace between Hegemonic Patriotism and Connectivity to the Ummah.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 30 (1): 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602001003650622.

- Iner, Derya, and Sean McManus. 2022. “Islamophobia in Australia: Racialising the Muslim Subject in Public, Media, and Political Discourse in the War on Terror Era.” In The Rise of Global Islamophobia in the War on Terror, edited by Naved Bakali, and Farid Hafez, 36–56. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Itaoui, Rhonda, and Elsadig Elsheikh. 2018. “Islamophobia Reading Resource Pack.” September.

- Jian, Guo, Yongyi Song, and Yuan Zhou. 2006. Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

- Kim, Hodong. 2004. Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- King, Gary, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts. 2013. “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression.” American Political Science Review 107 (02): 326–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014.

- Klug, Brian. 2012. “Islamophobia: A Concept Comes of Age.” Ethnicities 12 (5): 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812450363.

- Kozaric, Edin. 2023. “Are Muslim Experiences Taken Seriously in Theories of Islamophobia? A Literature Review of Muslim Experiences With Social Exclusion in the West.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268179.

- Leibold, James. 2010. “More Than a Category: Han Supremacism on the Chinese Internet.” The China Quarterly 203: 539–559. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741010000585.

- Lipman, Jonathan N. 1998. Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Lu, Yingdan, Jennifer Pan, and Yiqing Xu. 2021. “Public Sentiment on Chinese Social Media During the Emergence of COVID19.” Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media 1.

- Luqiu, Luwei Rose, and Fan Yang. 2020. “Anti-Muslim Sentiment on Social Media in China and Chinese Muslims’ Reactions to Hatred and Misunderstanding.” Chinese Journal of Communication 13 (3): 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2019.1699841.

- Malešević, Siniša. 2022. “Imagined Communities and Imaginary Plots: Nationalisms, Conspiracies, and Pandemics in the Longue Durée.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.94.

- McCarthy, Susan K. 2009. Communist Multiculturalism: Ethnic Revival in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Menon, Pratiksha. 2023. “Babri Retold: Rewriting Popular Memory Through Islamophobic Humor.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268152.

- Miao, Ying. 2020. “Sinicisation vs. Arabisation: Online Narratives of Islamophobia in China.” Journal of Contemporary China 29 (125): 748–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1704995.

- Mullet, Dianna R. 2018. “A General Critical Discourse Analysis Framework for Educational Research.” Journal of Advanced Academics 29 (2): 116–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X18758260.

- Najib, Kawtar. 2021. Spatialized Islamophobia. New York: Routledge.

- Noble, Greg, and Scott Poynting. 2010. “White Lines: The Intercultural Politics of Everyday Movement in Social Spaces.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 31 (5): 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2010.513083.

- Roberts, Sean R. 2020. The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign Against a Muslim Minority. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rose, Hannah. 2021. Pandemic Hate: COVID-Related Antisemitism and Islamophobia, and the Role of Social Media. Report. Institute for Freedom of Faith and Security in Europe. München. https://archive.jpr.org.uk/object-2354.

- Sealy, Thomas. 2021. “Islamophobia: With or Without Islam?” Religions 12 (6): 369–382. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060369.

- Shyrock, Andrew. 2010. “Introduction: Islam as an Object of Fear and Affection.” In Islamophobia/Islamophilia : Beyond the Politics of Enemy and Friend, edited by Andrew Shyrock, 1–27. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Silverstein, Paul A. 2010. “The Fantasy and Violence of Religious Imagination: Islamophobia and Anti-Semitism in France and North Africa.” In Islamophobia/Islamophilia : Beyond the Politics of Enemy and Friend, edited by Andrew Shyrock, 141–172. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Singh, Prerna. 2022. “How Exclusionary Nationalism Has Made the World Socially Sicker from COVID-19.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.36.

- Skey, Michael. 2010. “‘A Sense of Where You Belong in the World’: National Belonging, Ontological Security and the Status of the Ethnic Majority in England.” Nations and Nationalism 16 (4): 715–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2009.00428.x.

- Skitka, Linda J. 2005. “Patriotism or Nationalism? Understanding Post-September 11, 2001, Flag-Display Behavior1.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35 (10): 1995–2011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02206.x.

- Stroup, David R. 2021. “Good Minzu and Bad Muslims: Islamophobia in China’s State Media.” Nations and Nationalism 27 (4): 1231–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12758.

- Stroup, David R. 2022. Pure and True: The Everyday Politics of Ethnicity for China’s Hui Muslims. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Turner, Victor, and Edith Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press.

- The United Front Work Department of the CPC Wuhan Municipal Committee. 2020. “Jiang’an Qingzhensi Wancheng Yidi Bianqian Anzhi Gongzuo.” The United Front Work Department of the CPC Wuhan Municipal Committee. http://www.whtzb.org/home/info/20597.html.

- Wald, Priscilla. 2008. Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Wang, Jing. 2019. “Tiptoeing Along the Red Lines. On Chinese Muslims’ Use of Self-Censorship in Contemporary China.” Terrain. Anthropologie & Sciences Humaines 72, November.

- Xi, Jinping. April 30, 2014. “Zai Xinjiang kaocha gongzuo jieshushi de jianghua.” In “The Xinjiang Papers: An Introduction.” Uyghur Tribunal, edited by Adrian Zenz. https://uyghurtribunal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Transcript-Document-01.pdf.

- Xie, Guiping, and Tianyang Liu. 2021. “Navigating Securities: Rethinking (Counter-) Terrorism, Stability Maintenance, and Non-Violent Responses in the Chinese Province of Xinjiang.” Terrorism and Political Violence 33 (5): 993–1011. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1598386.

- Zenz, Adrian. 2021. “The Xinjiang Papers: An Introduction.” Uyghur Tribunal. https://uyghurtribunal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/The-Xinjiang-Papers-An-Introduction-1.pdf.

- Zhang, Chenchen. 2020. “Right-Wing Populism with Chinese Characteristics? Identity, Otherness and Global Imaginaries in Debating World Politics Online.” European Journal of International Relations 26 (1): 88–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119850253.

- Zhang, Chenchen. 2022. “Contested Disaster Nationalism in the Digital Age: Emotional Registers and Geopolitical Imaginaries in COVID-19 Narratives on Chinese Social Media.” Review of International Studies 48 (2): 219–242.

- Zhao, Xiaoyu. 2021. “A Discourse Analysis of Quotidian Expressions of Nationalism during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chinese Cyberspace.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (2): 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09692-6.