ABSTRACT

Between 2015 and 2017, the Internet Research Agency (IRA) – a Kremlin-backed “troll farm” based in St. Petersburg – executed a propaganda campaign on Twitter to target US voters. Scholarship has expended relatively little effort to study the role of Islamophobia in the IRA’s propaganda campaign. Following critical disinformation research, this article demonstrates that Islamophobia, affect, and white identity played a crucial role in the IRA’s targeting of right-wing US voters. With an official release of tweets and associated visual content from Twitter, we use topic modeling and visual analysis to explore both how, and to what extent, the IRA used Islamophobia in its propaganda. To do so, we develop a multimodal distant reading technique to study how the IRA aligned users with contemporary far right social movements by deploying racial and emotional appeals that center on narrating a transnational white identity under threat from Islam and Muslims.

Introduction

On the afternoon of 22 March 2017, Khalid Masood rammed a car into pedestrians on London’s busy Westminster Bridge, injuring over 50 and killing 4. He crashed into the UK Parliament grounds, stabbing and killing an unarmed police officer before he was fatally shot by police. On the bridge, photographer Jamie Lorriman captured a now-infamous photo of an injured man attended to by a group of survivors as a distraught woman in a hijab walks past, which was used by the New York Daily News (Faulkner, Guy, and Vis Citation2021, 204). At 6:18pm, a few hours after the attack, the right-wing Twitter account @TEN_GOP posted a copy of Lorriman’s photo, with the tweet: “When a photo says a thousands [sic] words. #London #LondonAttack” (see ). The tweet sparks a cascade of outrage on far right Twitter, already abuzz after the attack, following a well-documented pattern of Islamophobic speech online (Awan Citation2014; Evolvi Citation2018; Williams et al. Citation2020).

Figure 1. Tweet by TEN_GOP, 2017-03-22. “When a photo says a thousands words. #London #LondonAttack”. Note: this is a copy of the original photo taken by Jamie Lorriman. This copy is from the Twitter database.

A few hours later, far right influencer Paul Joseph Watson (@PrisonPlanet) posted the photo, tweeting only “#London” to his 500,000 followers (Watson Citation2017). Not long after, the account @SouthLoneStar wrote, “Muslim woman pays no mind to the terror attack, casually walks by a dying man while checking phone #PrayForLondon #Westminster #BanIslam” (Texas Lone Star Citation2017). The Daily Mail published the speculation as “vox populi” (Duell Citation2017; see Lukito et al. Citation2020).Footnote1 At 8:30pm on the 22nd, self-appointed “father” of the alt-right, Richard Spencer, retweeted it (Spencer Citation2017). Before its permanent ban from Twitter, @TEN_GOP described itself as the “Unofficial Twitter of Tennessee republicans.” In fact, @TEN_GOP was among a few thousand Twitter accounts created by the Internet Research Agency, LLC (IRA) “troll farm” in St. Petersburg, Russia that Special Counsel Robert Mueller indicted in 2018 (United States of America v. Internet Research Agency, LLC et al. Citation2018). So too was @SouthLoneStar (Faulkner, Guy, and Vis Citation2021).

The IRA sought to weaponize Islamophobic networks in their broader campaign to “sow discord” in the United States (Faulkner, Guy, and Vis Citation2021; Howard et al. Citation2018; Innes, Dobreva, and Innes Citation2021). Through their accounts, the IRA sought to generate anger and outrage by embedding themselves into existing networks of digital activism, primarily focusing on imitating conservative and right-wing users and creating “digital blackface” accounts that targeted Black Americans (Freelon et al. Citation2022; Linvill and Warren Citation2020b; Lukito et al. Citation2020). Despite the growing research into the IRA in the past five years (Al-Rawi and Rahman Citation2020; Bail et al. Citation2020; Bastos and Farkas Citation2019; DiResta et al. Citation2018; Freelon and Lokot Citation2020; Golovchenko et al. Citation2020; Howard et al. Citation2018; Lukito Citation2020; Xia et al. Citation2019), there has been relatively less attention to the mobilization of racism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia by these accounts. Our research demonstrates that the IRA’s mobilization of Islamophobia closely imitated the communication of transnational Islamophobic movements (see Berntzen Citation2019). Here, our analysis makes two contributions: first, we find Islamophobia was central to the propaganda that the IRA created that targeted right-wing users. Second, we show how the IRA’s propaganda utilized Islamophobia as part of an affective economy that generates identification with a transnational white identity under threat.

To focus on how Islamophobia is instrumentalized in a digital propaganda campaign, we build on critical disinformation scholarship that points to the importance of racism and affect. Drawing on the definition of propaganda used by Benkler, Faris, and Roberts (Citation2018): “communication designed to manipulate a target population by affecting its beliefs, attitudes, or preferences in order to obtain behavior compliant with political goals of the propagandist” (29), this article goes beyond the relatively narrow frame of “disinformation” by exploring how racism and affect are used to shape the identities of a target population, and in turn, reinforce specific beliefs, attitudes, and preferences.

While literature on Islamophobia focuses forms of control, discrimination, and governance of Muslim bodies deemed “risky” (Abbas Citation2020; Kumar Citation2012; Kundnani Citation2014; Walker Citation2021), it is not usually understood as propaganda. There is also a well-established literature on Islamophobic and anti-Muslim hate speech online that focuses on impacts on victims of hatred and abuse, Islamophobic discourse and networks on social media platforms (Awan Citation2014; Berntzen Citation2019; Ekman Citation2015; Evolvi Citation2018; Poole, Giraud, and de Quincey Citation2021; Vidgen and Yasseri Citation2020). Here, we focus specifically on an instrumentalized deployment of Islamophobia as part of ongoing efforts by the Kremlin to amplify polarization and animosity in Western democracies by supporting the far right (Polyakova Citation2014; Shekhovtsov Citation2017). Following the global flows and modalities introduced by the special issue editors (Ganesh, Frydenlund, and Brekke Citation2023), focusing on Twitter requires we explore symbolic, informational, technical, and economic flows of Islamophobia and focus on the modality of majoritarian group-making in opposition to Islam and Muslims, as well as the modalities of racialization and discourse. Through the framework developed in the introduction, we explore how the IRA exploited particular flows and modalities of Islamophobia central to transnational, Western Islamophobic imaginaries.

Following Ekman (Citation2015), who finds that “discourses disseminated by counter-jihadists suggest that Islamophobia is a flexible political strategy” (1998), and Mondon and Winter (Citation2017) who focus on how Islamophobia is articulated “from different sources and discourses and serves different purposes, contexts and constituencies” (2157), here we focus on a strategic appropriation of Islamophobia not in the interests of the US counter-terror state or by anti-Muslim activists, but rather in the interests of a nation-state that sought to enhance Donald Trump’s chances of electoral success in 2016. There is no evidence here to support the assertion that the IRA was successful. Instead, studying this geopolitical appropriation of Islamophobia demonstrates that the exploitation of domestic actors that mobilize majoritarian identities on digital platforms – specifically far right activism – is a central concern for the impact of social media and democracy. We find that Islamophobia represents a key vector of propaganda that the IRA used to encourage collective identification with a translocal whiteness that closely resembles white supremacist discourse (Back Citation2002; Daniels Citation2009; Citation2018; Ferber Citation1999), though it is racially unmarked on its surface. This is indicative that the IRA sought to engage and amplify discourses on Islam and Muslims that, as we discuss below, contribute to the efforts of domestic actors across Europe and the US to normalize white supremacist and far right narratives (see also Wodak Citation2020).

We contribute to the disinformation literature by integrating the study of the production of white identity through an affective economy of hate (Ahmed Citation2014), focusing on Islamophobia. To do so, we deploy a multi-modal distant reading of tweets that combines network analysis, topic modeling, and media visualization. We consider how the IRA sought to exploit and add to an affective economy that uses visuals of a flood to render Islam and Muslims metonyms for the destruction of the West, abetted by traitors. Recent work demonstrates that the IRA was primarily successful in engaging with audiences that shared the dispositions that its fake profiles expressed (Bail et al. Citation2020). We find that the IRA closely imitated the narratives of transnational anti-Muslim activism and the “counter-jihad”, a key sector of the far right (see Berntzen Citation2019; Pertwee Citation2020), connecting “patriotism” with the responsibility of protecting Western civilization. The IRA’s strategy, then, was not simply “disinforming” the public, but to co-opt participatory cultures on platforms through identity construction.

IRA propaganda: Islamophobia, racial identity, and affect

Definitions and scholarship on disinformation often focus on veracity: content in which truthfulness of a particular claim, news story, or contestable fact is in question (Bennett and Livingston Citation2018; European Commission Citation2018; Freelon and Wells Citation2020). Islamophobia itself definitively involves falsehood and conspiracy (as is the case with other fictions of “race”): consider the claims of demographic “replacement”, “fifth columns” and “Islamization”, and the stereotype of Muslims as sexual predators. As Benkler, Faris, and Roberts (Citation2018) argue, Islamophobic propaganda was central to right-wing and pro-Trump communication. The IRA’s imitation of this propaganda, by deceiving publics about the authenticity of its users, sought to shape the attitudes and beliefs of right-wing Americans to see themselves as part of a collective white identity under threat (see also Ganesh Citation2020). While Bennett and Livingston (Citation2018) pay attention to this in theorizing the “disinformation order”, for the most part, the field has not developed a robust understanding of how racism and disinformation work together to construct majorities as racial groups with collective structures of feeling (see Papacharissi Citation2015). As the critical work discussed below argues, what is commonly referred to as “disinformation” (the IRA being a paradigmatic contemporary example) actually references a much more complex set of communications that chiefly involve the appropriation of preexisting, domestic, or transnational narratives. Consequently, the term propaganda better suits this research than does disinformation, though critical literature on the latter provides important insights.

Critical work in disinformation studies has pointed out that a focus on veracity obscures how the appropriation of racial and/or ethnic identity and the manipulation of affect are central to the circulation of disinformation (George Citation2021; Kuo and Marwick Citation2021; Mejia, Beckermann, and Sullivan Citation2018; Reddi, Kuo, and Kreiss Citation2023; Young Citation2021). As Xia et al. (Citation2019) argue in studying Jenn Abrams, one of the most prominent right-wing Twitter accounts the IRA set up, disinformation involves a process of cultivation and ritual in which the account must authenticate itself as a genuine member of a racial identity and perform the codes of that culture, repeating its “deep stories”. Jenn Abrams performed specific repertoires of white rage and anti-immigrant hate (Al-Rawi and Rahman Citation2020; Culloty and Suiter Citation2021), aligning “her” persona with white, right-wing Americans. Indeed, the IRA developed a series of profiles with content intended to embed their accounts as authentic, US-based personas (Linvill and Warren Citation2020b). On Facebook and Instagram, the IRA purchased thousands of advertisements for various pages and profiles it set up which targeted racial proxies available in Facebook’s advertising software. Lukito et al. (Citation2020) find significant racial asymmetries that outweigh the ideological ones, demonstrating that on Twitter, digital blackface accounts received the most engagement of all IRA profiles.

Research on disinformation and the IRA does not sufficiently attend to how disinformation campaigns rely upon and exploit existing social orders and hierarchies (Kuo and Marwick Citation2021, 4). Kreiss argues that the field

implicitly treats race as something that only happens to people who are not white – as if images of a white Jesus arm wrestling the devil and Yosemite Sam in front of a Confederate flag, two of the Russian Internet Research Agency’s graphic disinformation images from 2016, were not appeals to whites every bit as racial as content targeting black Americans (Citation2021, 509).

In addition to gaps on racism and constructed racial identity, the focus on veracity in the disinformation literature also obscures the role of affect. Young (Citation2021) argues that disinformation is effective precisely because “it exploits a collective desire for affective belonging and community” (2). The privileging of veracity and truth “[ignores] the underlying affective economies that produce partisan antagonisms in the first place” (2). The IRA built on the existing affective dispositions developed by transnational far right networks, constructed around “anger, outrage, and hate”, which are among the emotions with the “greatest currency value” (Boler and Davis Citation2020, 20). Ganesh (Citation2020) demonstrates that these emotions are fundamental to ensembles of followers of far right influencers on Twitter based in the US and the UK and are embedded in white supremacist networks at varying depths. Similarly, Ekman argues that affective communication enables alignment of individuals with specific in-group identities by integrating propaganda strategies and affective responses of users to shape identity (Citation2019, 608). Nikunen, Hokka, and Nelimarkka (Citation2021), studying the Finnish Soldiers of Odin Facebook group, argue that “affective practices” are “powerful in addressing identity and a sense of authenticity” through images and responses to them that “amplified particular affective registers”, identifying Muslims and migrants as objects of anger and ridicule (Citation2021, 179). In this special issue, the approach we take here bears similarities with Menon (Citation2023), who focuses on the specific formation of Islamophobic schadenfreude as a vehicle for Hindu nationalist group-making and historical revisionism. Together, these articles help to explore how rage, anger, and humor reinforce racist and ethnonationalist mythologization of the Muslim other.

Affect plays an important role in generating collective identifications through social media (Papacharissi Citation2015). Jodi Dean argues that “affective attachments to media are not in themselves sufficient to produce actual communities … Affective networks produce feelings of community, or what we might call 'community without community'” (Citation2015, 91). This work indicates that affect plays a crucial role in generating potential collective identity through the expression of white victimhood that can be realized with propaganda. A study of “#whitegenocide” on Twitter, for example, finds that uses of the hashtag are “affective positionings of individual users” that position them as part of a broader, translocal, “collective White self under siege” (Deem Citation2019, 3196).

As “affective economies” that have datafied and monetized emotion (Bakir and McStay Citation2020), social media platforms enable new speeds and scales for this circulation of hate, which works to position bodies as members of collective identities (see Ahmed Citation2014, 46). These economic flows – here focused on circulation of affects monetized in platform economies – play an important, but less-examined, role in Islamophobia research. The goal of the IRA appears less to be spreading disinformation as much as it is in enveloping users in an affective economy that strategically uses Islamophobia to align target populations with transnational far right and white supremacist narratives ascendant in the alt-right and the Trump campaign (see Ganesh Citation2020). While this is not a focus of the article, this points to the role of platforms as mediators and amplifiers of racist discourse, considering that a handful of these accounts (eg. @JennAbrams and @TEN_GOP) experience rapid growth without platform intervention until 2018 (Matamoros-Fernández Citation2017). This is an important area for future research understanding the role and impact of social media corporations in establishing and sustaining technical flows of Islamophobia (see Ganesh, Frydenlund, and Brekke Citation2023) that Kozaric et al. (Citation2023) in this issue discuss in the context of WikiIslam. While there is no doubt that the IRA’s effort is far overshadowed by a domestic right-wing media ecosystem (Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Citation2018), studying the IRA’s mobilization of Islamophobia can expose how racism and affect work together in the IRA’s campaign.

Methodology

Our project investigates the role of Islamophobia in the IRA’s propaganda campaign in a large release of official Twitter data. To start, we had to identify instances of Islamophobia across the dataset. Based on the existing literature (Al-Rawi and Rahman Citation2020; Bastos and Farkas Citation2019; Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Citation2018; Howard et al. Citation2018), we expected that the majority of Islamophobic content would come from the IRA’s right-wing accounts. We use social network analysis to isolate these accounts before applying a multimodal distant reading technique to study the IRA’s Islamophobic propaganda.

Data source and filtering process

We use a data release from Twitter on “information operations”, which refers to “Platform manipulation that [Twitter] can reliably attribute to a government or state linked actor” (Twitter Citation2022). Twitter provides these datasets publicly, but usernames are replaced with cryptographic keys or “hashes”. Twitter provides access to unhashed data on application from academic and non-governmental users, which the research team acquired in upon application. While Linvill and Warren (see Citation2020b) provided a public release of comprehensive IRA tweet data in 2018, the advantage of the official Twitter data is it includes a vast trove of visual content. In the 2018 “information operations” release for the IRA, we find 8.77 million tweets, of which 4.85 million are in Russian and just under 3 million are in English. 3,077 individual IRA accounts created these English tweets, of which the vast majority received little, if any, engagement.

The sample of English tweets includes a wide range of accounts. Unlike most of the literature which relies on Linvill and Warren’s (Citation2020a) coding scheme, we used a computationally-assisted inductive approach based on a graph of network links (@mentions and retweets) outgoing from the IRA users to isolate the right-wing accounts. We then use a community detection algorithm (Blondel et al. Citation2008) that identifies densely connected users. Three main communities emerged from this algorithm: right-wing, digital blackface, and “hashtagger” accounts (also identified by Linvill and Warren Citation2020a). We then further filter our sample of 3 million tweets down to just the tweets authored by the right-wing accounts, which resulted in a final sample of 1.11 million tweets by 870 users. There is certainly the potential that instances of Islamophobia may be found in the tweets we do not study in this sample. However, examination of Appendix Table 1, which shows top hashtags in these three communities, reveals that “#MuslimBan” is the second most popular hashtag by engagement score for the right-wing community. The top hashtags in the other communities indicate few references to Islam and Muslims, but the high engagement with “#MAGA” in the digital blackface community is worth future investigation. This is a rough measure that indicates we have targeted the correct group, and many more Islamophobic hashtags appear below the top-10 for right-wing users. While our analysis is similar to Linvill and Warren’s classification, they identify 454 accounts as “Right Trolls”. Our sample is larger than this group, and does include many of the accounts they identify as “News Feed” accounts and “Fearmonger” accounts that had similar social ties on Twitter.

Multimodal distant reading: topic modeling and cultural analytics

To study IRA content, we deploy a multimodal distant reading technique that combines automated text categorization with cultural analytics, a set of techniques developed by Manovich (Citation2020) to observe new media datasets. Rather than start with the images, we use topic modeling to estimate the quantity of Islamophobia in the dataset. Then, we create grids of images included in tweets that the model predicts have a high probability of being about Islam or Muslims. This allows us to study affective economies at a wide scale. We use the topic model to provide metadata about the images (chiefly, topic probability and engagement) and to query the dataset to generate qualitative insight building on an approach to affective “territories” of social media images (Rose and Willis Citation2019).

We process the tweets in the sample of 1.11 million into machine-readable documents before loading each document into an algorithm to create a topic model (Hoffman, Bach, and Blei Citation2010), a widely used method to automatically organize large text corpora previously used on IRA tweets (Al-Rawi and Rahman Citation2020; Walter, Ophir, and Jamieson Citation2020). Topic models require the user to identify the number (k) of topics to return in the final model. Once the algorithm is trained on the data, the model then provides a probability distribution for each text on which it was trained and on texts it has not yet seen. We generated models with k topics ranging from 5 to 70, incrementing k in multiples of five. While the model’s formal metrics improve as k increases, we found that as we incremented k, the topics became less interpretable and more idiosyncratic (based on the specific characteristics of certain accounts or specific events that the IRA discussed). We settled on k = 15 topics, which provided sufficiently aggregated topics so that it was possible for us to manually label and analyze each topic. In the process we discovered that the 13th topic was almost entirely about Islam, Muslims, terrorism, and migration, which allows us to estimate the amount of Islamophobic content across the dataset.

After identifying the Islam, Muslims, and Refugees topic from all the tweets in the data, we then generate a set of image montages to study those tweets that did include an image ordered in a grid ordered from the upper left down to the bottom right (Manovich Citation2020). This imitates a similar visuality to the scroll of images on platforms, which helps us explore the affective intensities evident in the content (Rose and Willis Citation2019, 417). Studying smart cities, Rose and Willis (Citation2019) argue that given their ultimately fruitless attempt to tag and categorize images, “the feeling grew that what the images were showing was less their format or content or genre, and more certain ways of becoming … the analysis shifted towards sensing the affective territories that different clusters of images were felt to configure” (419). They turn to color to identify three different “affective territories” based on three repertoires, “participating” in orange, “learning” in orange and blue, and “anticipating” in blue (420). Our project uses the montage technique differently than this and other approaches (Pearce et al. Citation2020). Instead of using color we use the textual modality to filter the images displayed and the numeric metadata of engagement to sort them in the visualizations. Approaching the visualizations as Rose and Willis (Citation2019) do allows us to maintain an analytic focus on the affective economy of Islamophobia that the IRA appropriated. The combination of the montage visualization technique and filtering using topic model probabilities allows us to sift through the sample of tweets and study the feelings that these images convey using a visualization technique that is attuned to the hyper-visibility of social media (Rose and Willis Citation2019, 415). The QR codes and links in direct the reader to digital copies of the montages.

Figure 3. Digital Montages of Islamophobic Content. Note: to view and explore the montage, download each montage on a PC or mobile device, and use an image viewer to pan, zoom, and scroll through the montage in an image viewer. Montages are accessible via QR code or the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8269107.

Initial descriptive findings on Islamophobia in the IRA dataset

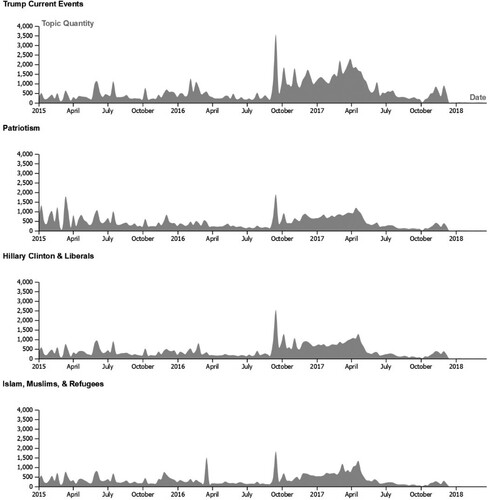

provides a title for each topic we detected and scores for engagement and quantity of tweets with each topic.Footnote2 While engagement is an imperfect measure because many IRA tweets and profiles received little to no engagement, it is the only metric that allows us to ascertain what resonated with audiences. That the Islam, Muslims, and Refugees topic is in the top 4 indicates its salience for the audience the IRA targeted. Across our partition of right-wing users, tweets about four topics received the most engagement: Trump Current Events, Patriotism, Hillary Clinton & Liberals, and Islam, Muslims, & Refugees. We find that the Islam, Muslims, & Refugees topic has the third highest engagement score despite being towards the lower end of the topic quantity range, which indicates that tweets about this topic generally receive high engagement. In , we display a topic quantity score over time, which shows that these topics are closely correlated (R > 0.80 between the Islam, Muslims, & Refugees topic and the three others, p < 0.01), though there are spikes that correspond to terrorist attacks that are unique to the Islam, Muslims, & Refugees topic (see Innes, Dobreva, and Innes Citation2021). (and the correlation reported above) demonstrates that Islamophobia is closely integrated with the three other topics that received the most engagement, indicating the importance of Islamophobia across the IRA’s efforts to target right-wing users.

Table 1. Topic engagement and quantity scores.

Figure 2. Topic quantity score over time, selected topics. Note: topic quantity score is measured as the sum of the probability of each topic across all tweets in a given week. It is not normalized here, as opposed to .

The flood, the traitors, and the protectors

The IRA used Islamophobia to align users with an implicit white identity that imagines itself under threat. This is closely tied with the Trump campaign and the Breitbart-led media ecosystem that drove a campaign about “radical Islamic terrorism” as a “battering ram against the walls of the Republican party establishment” (Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Citation2018, 144). This was not a sudden turn; as Bail (Citation2014) finds, Islamophobic civil society organizations grew between 2001 and 2008 and developed networks and influence across the right. Pertwee argues that “if any far-right movement gained tangible political power as a result of Trump’s election, it was the counter-jihad” (Citation2020, 222). Ekman, studying the counter-jihad blogosphere, refers to discursive strategies referencing demographic threats, fears about Islamization, Sharia Law, Islamism, the allegedly inherent violence of Muslims, political correctness and concealed truths about Islam, and the role of multiculturalism, liberalism, and progressives as “allies” with Islam (Ekman Citation2015), all themes immediately apparent in the montages linked in .

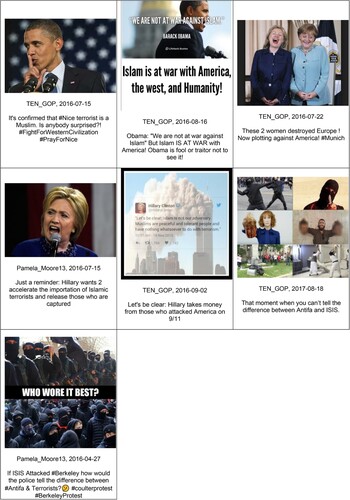

Montage 1 illustrates many similar frames to those Berntzen (Citation2019) finds among transnational Islamophobic movements (see also Bangstad Citation2014; Fangen Citation2020; Gardell Citation2015; Hervik Citation2019; Wodak Citation2020). Upon viewing Montage 1, the viewer is immediately struck by how much text is present, as well as the extent of graphics that include multiple images in one. These graphics, memes, and quotes dominate the eye, though many photos are also present. These photos reproduce the fear of a flood of bodies, many of them covered in Islamic clothing, that are impinging on Europe’s streets, disrupting its “peaceful”, “ordinary” life. Here, we follow Ahmed’s argument that “the emotion of hate works to animate the ordinary subject, to bring that fantasy to life, precisely by constituting the ordinary as in crisis, and the ordinary person as the real victim” (Citation2014, 43). This enables identifications with an unmarked whiteness (Bell Citation2021; Frankenberg Citation1993): the ostensibly “ordinary” American who defends themselves and their country from an invading flood. Yet, Montage 1 includes many faces of politicians perceived to be progressive liberals, such as Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton, and Angela Merkel. They are subjects of ridicule and outrage in the graphics, represented as traitors that opened the gates to the flood who brought in the crisis that threatens “ordinary” life. What is important, then, is less the content of the IRA’s Islamophobia (it imitates transnational narratives studied by Berntzen Citation2019) but rather how it is used to construct the “ordinary” subject as the righteous protector of the bodies of these victims who are, like the victims of terrorism, metonyms for “that which is under threat not only by terrorists (those who take life), but by all that the possibility of terrorism stands for” (Ahmed Citation2014, 77).

The flood

Many of the photos in Montage 1 are of what appear to be angry Muslims protesting, burning flags, holding placards, and praying. In most cases, when Muslims are pictured, they are in large gatherings. The IRA’s depiction of Muslims in Montage 1 is consistently illiberal Islamophobia (Mondon and Winter Citation2017), with images of Muslims burning flags or praying in streets and city squares as alarmist renditions of the ongoing “invasion” of the West through photos with wide angles filled with flooding bodies. This serves an evidentiary function, with the visual modality providing “proof” that justifies Islamophobia. The discourse in the tweets and these images is consistent with the language of far right politicians, social movements, and their audiences across Western Europe, in which discussions about Europe frequently reference Muslims “everywhere” and fears of “Islamization” (Ganesh and Froio Citation2020). In one image, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic, which the IRA claims did not take in any refugees, are represented as idyllic, traditional European cityscapes while Germany, Belgium, and France represent the “decline of the West” (). By constructing the ruin of “traditional” European culture due to flooding immigrants, and amplifying the threat as impinging on the US border, the IRA aligns audiences with a global white identity under threat. This is most evident in the oft-repeated image of George Soros’s face in the center of four images that represent the destruction of the West, reproducing the now ubiquitous far right trope of Soros as some kind of Jewish puppet master (Kalmar Citation2020). As other articles in this special issue indicate, transnational imaginaries articulate homologous perspectives of the “flood” pictured here; for example, Frydenlund (Citation2023) in this special issue discusses how Muslims are framed as an impinging, threatening presence in Buddhist South Asian group-making that spans India, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka. Thus the pattern of presenting Muslims as a transnational threat is repeated; here by displaying Europe as the frontline of the “invasion”, the IRA demonstrated it sought to directly amplify transnational far right social movements that see “Islamization” as a civilizational struggle across the Atlantic (Berntzen Citation2019; Pertwee Citation2020; Thorleifsson Citation2018). This demonstrates that the IRA’s Islamophobic propaganda creates boundaries and identities that position the “ordinary” American – outraged and fearful of the flood – as a protector of the “West” (see Gardell Citation2015).

The traitors

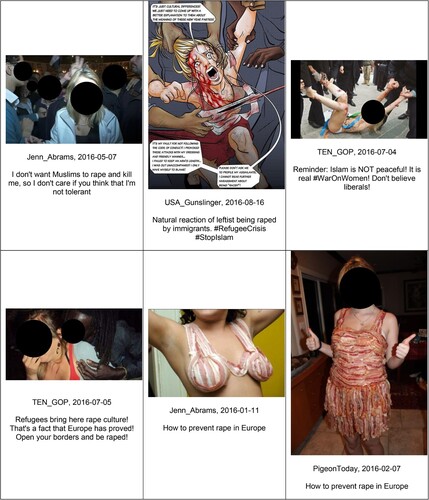

The metonym of the traitor adheres to liberals whose chief transgression is their alleged sympathy for Muslims at the expense of “ordinary” Americans. Numerous images of Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Angela Merkel (see and Montage 1) appear in the dataset (even one with the latter in Islamic clothing) pictured as traitors selling out the nation. The IRA’s use of compound images, with photos with two or more images and (usually) text equivocating liberals, progressives, multiculturalists, and leftists with terrorism, often comparing them to ISIS is particularly common. includes an image of Kathy Griffin holding a bloody replica of Trump’s head next to a picture of a man smiling while he holds up two decapitated heads was posted with the text, “That moment when you can’t tell the difference between Antifa and ISIS”. Another image asks, “who wore it best?”, comparing ISIS and Antifa face coverings. These comparison images slide from equivocating “Antifa” with ISIS (in ) to more generally associating all liberals as those that sacrifice security, liberty, and tradition for the sake of multiculturalism. This is reinforced as well through the many comics, graphics, quotes, and other depictions of political elites. As we explore how Islamophobia intersects with other topics, the role of traitors in binding the (unmarked) white self under threat becomes more clear.

Islamophobia’s intersection with other topics

Moving onto Montages 2–4 that explore Islamophobia in other topics, we see how both IRA aligns target groups as the protectors of the “West” in this affective economy. This often occurs through the use of comparisons in these montages that reinforce what these protectors are not. Many of the images here involve comparisons between “Patriots” and “Liberals” and “Veterans” and “Refugees”. Syrians and Muslims are presented as receiving support from politicians at the expense of “veterans”, or even a comparison image featuring two children, with the liberal one holding a sign that says, “Fuck your fascist bullshit”. Another has a picture of “ISIS” on the left toppling a statue and American “Progressives” on the right toppling a statue as well. Another includes a “before” and “after”, with white women holding up a banner with “Refugees Welcome” on top (before) and images of a riot and violence against women below (after). Where the Patriotism topic’s intersection with Islamophobia focuses on identity, the “Trump Current Events” montage is like a stream of news demonstrating the collusion of liberals, elites, and progressives with the alleged project of “Islamization”. Images reference Khizr Khan, recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, who spoke out against Trump on behalf of Clinton’s campaign; an image of George Soros; and frequent references to refugees as “rapefugees” and “terrorists”. Finally, the “Hillary Clinton & Liberals” topic features many more pictures of faces than the other montages, with numerous quotes and statements from Donald Trump about defeating ISIS, in opposition to liberals whose acknowledgement of Islamophobia is a foolish appeasement, with “evidence” delivered by ex-Muslim Ayaan Hirsi Ali and author Christopher Hitchens.

The intersection of the of these topics with Islam, Muslims, and Refugees works to stabilize the idea of the “West” and all it stands for as undermined by an internal other. It shows us that for the IRA, the construction and reinforcement of a white identity under threat was its central goal. Donald Trump reappears across these montages as the ultimate protector by “telling the truth” about liberal foolishness and the impinging flood by transgressing the ostensible political correctness characteristic of political elites such as Obama, Clinton, and Merkel. Thus the protector who opposes the flood and calls out traitors is inoculated from fear of being racist; they are the cool-headed, rational defender of a nation liberals sold out. In doing so, the IRA uses Islamophobia to launder and normalize the idea that right-wing Americans are part of a threatened, transnational collective. By relying on Islamophobic propaganda, the IRA is able to render racist expression a righteous claim for protecting “ordinary” Americans.

Destruction and violation

As much as the racist content the IRA created racializes Muslims, it is fundamentally more about the construction of an identity in opposition to the flood and the traitors. This is particularly evident in the representation of the woman-as-victim as a metaphor for the threatened “West” (see Ahmed Citation2014, 77), appropriating femonationalist forms of Islamopohobia (Fangen Citation2020; Tebaldi Citation2021). Because it claims to speak on behalf of women’s rights, by positioning Islam and Muslims as irretrievably misogynist and homophobic, these narrations appeal to liberal and centrist publics not usually associated with the far right (see Berntzen Citation2019). However, the IRA opts for a graphic depiction of the physical violation of white women at the hands of refugees and Muslims, a prevalent transnational trope (Horsti Citation2017; Thorleifsson Citation2019; Wigger Citation2019). Binding “our” culture as respectful of women, safe, secure, and clean, until the flood arrives at the invitation of the traitors, the IRA mobilizes what Ahmed refers to as a metonymic slide in which the Muslim represents the violation of white femininity.

The most emotional images the IRA uses specifically mobilize the anxiety of rape and the violation of women in which the ordinary subject recognizes itself as under threat, depicted in (Ahmed Citation2014; Horsti Citation2017, 1453). Much of this content uses examples from Europe as a dark premonition of what is to come if “we” are not vigilant against Islam. The second image in is a comic that ridicules a victim, reproducing the paradox that Horsti identifies in the figure of the violated Swedish woman, who is represented as both “whiteness under siege and threatening White feminism” because of her anti-racism and tolerance of cultural difference (Citation2017, 1452). Numerous references to Sweden in Montage 1 (e.g. Swedish flags) also refer to this narrative. Other images attempt to use anti-Muslim humor to reference this anxiety, with two images featuring white women dressed in bacon both featuring the tweet, “How to prevent rape in Europe”.

The IRA’s Islamophobic stream thus represents an affective economy that melds together liberal, progressive, and centrist elites as the benefactors of the flood with the support of liberal fools, self-destructive feminists, and ostensible antifa terrorists. In doing so, the IRA participates in an established affective economy that positions white identity as facing an existential threat by building on the existing dispositions and circuits of fear, hate, conspiracy, and outrage already developed by far right alternative media, the counter-jihad, and contemporary white supremacists (Berntzen Citation2019; Boler and Davis Citation2020; Deem Citation2019; Ganesh Citation2020). In this sense, the IRA is able to mobilize affect to enhance unmarked white identification with Donald Trump’s campaign as a disposition to save America, and in doing so, rendering hatred into an act of love (Gardell Citation2015). In this sense, the IRA’s affective economy of Islamophobia entrains a hateful, bellicose whiteness – without doing so in name – that intervenes in an affective economy to inscribe users into the contemporary networks of white supremacist discourse.

Conclusion

Islamophobic propaganda plays a key role in the IRA’s disinformation campaign targeting right-wing users in the US. This article, however, demonstrates that disinformation is an incomplete descriptor for a propaganda campaign that exploited an existing transnational affective economy, exploiting a wide range of propaganda produced by social movements. Beyond the deception of the IRA’s users masquerading as genuine US activists (see Golovchenko et al. Citation2020), it is nearly impossible to differentiate the IRA’s activities from propaganda produced by a wide range of actors and social movements active in the US and Europe (see Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Citation2018; Berntzen Citation2019; Ganesh and Froio Citation2020). While our analysis reveals little that would surprise scholars of Islamophobia, it problematizes the idea that the IRA injected disinformation into the US public sphere; rather, it appropriated and co-opted organic transnational racist activism into its geopolitical strategy.

What is new, in this article, is how this imitation of transnational Islamophobic propaganda allowed the IRA to appropriate an existing affective economy, laundering anti-Muslim, racist, and white supremacist discourses through the use of visual content in two ways. By imitating social movements and Islamophobic activism, the IRA was able to authenticate its users as genuine (see Xia et al. Citation2019), generate significant engagement with Islamophobia, and align target populations with a narrative of a transnational white identity under threat. This has significant implications for responding to the threat that disinformation and propaganda on social media present to democracies: it exploits existing forms of hate and racism as a strategy to amplify anti-democratic social movements rather than only try to dupe audiences with tailor-made falsehoods from external actors. As the previous section shows, the metonyms of the flood and traitor generate an in-group identification with an unmarked white collective self under siege. This can help us to clarify the relationship between Islamophobia, racism, and disinformation: while Islamophobia generally trades in false narratives, what “disinforms” in these images is not only their misleading and biased content, but the use of racially-bound forms of fear and anxiety makes these myths felt realities, working at the level of shaping the dispositions of populations rather than disseminating “fake news” or incorrect information. Consequently, we refer to Islamophobic propaganda rather than “disinformation” to reflect the broader, more complex reality of the IRA’s campaign, that clearly focused on transnational group-making based on white identity. While this article only addresses some of the flows and modalities charted in this special issue, future research on social media and Islamophobia could focus more on the technical flows that shape the circulation of Islamophobia and how this intersects with platforms’ strategies to control and manage user-generated content.

It is also apparent that Islamophobia is diffused throughout the IRA’s propaganda; though it is evident in its own topic, we find that Islamophobia is closely connected to what appears to be the IRA’s broader project of making the fears of invasion and destruction affectively present to right-wing Americans. Here we see that whiteness is not hailed directly; it is through metonym – and particularly the violation of the white woman – that constructs the white subject as victim by positioning the “ordinary” as under threat (Ahmed Citation2014). What is surprising is that it is European whiteness under threat in the data despite the target audience being based in the US.

The IRA would not have been successful in deploying Islamophobic propaganda if it were not seeded by domestic and transnational social movements. While the IRA was able to add a transnational imaginary that used Europe as a premonition of what is to come in the US, extending this narrative across the Atlantic, we can only speculate on what the IRA achieved from this. It is clear that they were able to amplify and launder Islamophobic propaganda to cultivate networks enveloped in the affective economy described above. In doing so, the IRA amplifies transnational Islamophobic social movements of Islam and Muslims in a bid to inscribe users in transnational far right milieus. Considering the context of the mainstreaming of white supremacy in the form of far right politics today that has undoubtedly benefitted from social media (Daniels Citation2018; Miller-Idriss Citation2020; Mondon and Winter Citation2020), our research shows that Islamophobia is a key vulnerability in democratic systems that contemporary debates on “disinformation” cannot afford to ignore.

Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the thoughtful feedback of four anonymous reviewers whose efforts significantly improved this article. As well, the authors appreciate the efforts of the Twitter Moderation Research Consortium in making the data used here available to researchers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Lukito et al. (Citation2020) find that various IRA accounts ended up in newspapers, but do not cover this specific incident. They find that @TEN_GOP had frequently been featured in newspapers. On 23 March 2017 at 20:50, @SouthLoneStar gloated that its tweet made it into the Daily Mail (see http://web.archive.org/web/20170329032028/https://twitter.com/SouthLoneStar).

2 Because our topic model only returns a probability distribution of each topic across each tweet, we cannot simply count the number of engagements or tweets associated with each topic. First, we create a topic engagement score. For each tweet, we multiply the engagement that tweet had with the probability of each topic; eg. if a tweet had 30 per cent probability of being in topic A and 70 per cent probability of being topic B and received 100 engagements, 30 points are awarded to topic A and 70 to topic B. Table 1 displays the sum of all points awarded to all 15 topics. The topic quantity score is a metric of the frequency of that topic in the dataset. The topic quantity score is the sum of the topic distribution for each tweet across all 15 topics, and in is normalized by dividing by the total number of tweets in the dataset per topic, multiplied by 100.

References

- Abbas, T. 2020. “Islamophobia as Racialised Biopolitics in the United Kingdom.” Philosophy & Social Criticism 46 (5): 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453720903468.

- Ahmed, S. 2014. Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Åkerlund, M. 2022. “Dog Whistling far-Right Code Words: The Case of ‘Culture Enricher’ on the Swedish web.” Information, Communication & Society 25 (12): 1808–1825. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1889639.

- Al-Rawi, A., and A. Rahman. 2020. Manufacturing rage: The Russian Internet Research Agency’s political astroturfing on social media. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v25i9.10801.

- Awan, I. 2014. “Islamophobia and Twitter: A Typology of Online Hate Against Muslims on Social Media.” Policy & Internet 6 (2): 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI364.

- Back, L. 2002. “Aryans Reading Adorno: Cyber-Culture and Twenty-Firstcentury Racism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 25 (4): 628–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870220136664.

- Bail, C. 2014. Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bail, C., B. Guay, E. Maloney, A. Combs, D. S. Hillygus, F. Merhout, D. Freelon, and A. Volfovsky. 2020. “Assessing the Russian Internet Research Agency’s Impact on the Political Attitudes and Behaviors of American Twitter Users in Late 2017.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (1): 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906420116.

- Bakir, V., and A. McStay. 2020. “Empathic Media, Emotional AI, and the Optimization of Disinformation.” In Affective Politics of Digital Media, edited by M. Boler and E. Davis, 263–279. London: Routledge.

- Bangstad, S. 2014. Anders Breivik and the Rise of Islamophobia. London: Zed Books.

- Bastos, M., and J. Farkas. 2019. “Donald Trump Is My President!”: The Internet Research Agency Propaganda Machine.” Social Media + Society 5 (3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119865466.

- Bell, M. 2021. “Invisible no More: White Racialization and the Localness of Racial Identity.” Sociology Compass 15 (9): e12917. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12917.

- Benkler, Y., R. Faris, and H. Roberts. 2018. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bennett, W. L., and S. Livingston. 2018. “The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions.” European Journal of Communication 33 (2): 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317.

- Berntzen, L. E. 2019. Liberal Roots of Far Right Activism: The Anti-Islamic Movement in the 21st Century. London: Routledge.

- Bhat, P., and O. Klein. 2020. “Covert Hate Speech: White Nationalists and Dog Whistle Communication on Twitter.” In Twitter, the Public Sphere, and the Chaos of Online Deliberation, edited by G. Bouvier and J. E. Rosenbaum, 151–172. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41421-4_7.

- Blondel, V. D., J.-L. Guillaume, R. Lambiotte, and E. Lefebvre. 2008. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2008: P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

- Boler, M., and E. Davis. 2020. “Introduction: Propaganda by Other Means.” In Affective Politics of Digital Media, edited by M. Boler and E. Davis, 1–50. London: Routledge.

- Culloty, E., and J. Suiter. 2021. “Anti-immigration Disinformation.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism, edited by H. Tumber and S. Waisbord, 221–230. London: Routledge.

- Daniels, J. 2009. Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Daniels, J. 2018. “The Algorithmic Rise of the “Alt-Right.” Contexts 17 (1): 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504218766547.

- Dean, J. 2015. “Affect and Drive.” In Networked Affect, edited by K. Hillis, S. Paasonen, and M. Petit, 89–100. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Deem, A. 2019. “The Digital Traces of #Whitegenocide and Alt-Right Affective Economies of Transgression.” International Journal of Communication 13: 20.

- DiResta, R., K. Shaffer, B. Ruppel, D. Sullivan, R. Matney, R. Fox, J. Albright, and B. Johnson. 2018. The Tactics & Tropes of the Internet Research Agency (p. 103).

- Duell, M. 2017, March 23. Trolls blast Muslim woman seen walking through terror attack. Mail Online. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/~/article-4342438/index.html.

- Ekman, M. 2015. “Online Islamophobia and the Politics of Fear: Manufacturing the Green Scare.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (11): 1986–2002. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1021264.

- Ekman, M. 2019. “Anti-immigration and Racist Discourse in Social Media.” European Journal of Communication 34 (6): 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323119886151.

- European Commission. 2018. A Multi-Dimensional Approach to Disinformation: Report of the Independent High Level Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759739290.

- Evolvi, G. 2018. “Hate in a Tweet: Exploring Internet-Based Islamophobic Discourses.” Religions 9 (307). https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100307.

- Fangen, K. 2020. “Gendered Images of us and Them in Anti-Islamic Facebook Groups.” Politics, Religion & Ideology 21 (4): 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2020.1851872.

- Faulkner, S., H. Guy, and F. Vis. 2021. “Right-wing Populism, Visual Disinformation, and Brexit: From the UKIP ‘Breaking Point’ Poster to the Aftermath of the London Westminster Bridge Attack.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism, edited by H. Tumber and S. Waisbord, 198–208. London: Routledge.

- Ferber, A. L. 1999. White Man Falling: Race, Gender, and White Supremacy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Frankenberg, R. 1993. White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Freelon, D., M. Bosetta, C. Wells, J. Lukito, Y. Xia, and K. Adams. 2022. “Black Trolls Matter: Racial and Ideological Asymmetries in Social Media Disinformation.” Social Science Computer Review 40 (3): 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439320914853.

- Freelon, D., and T. Lokot. 2020. “Russian Twitter Disinformation Campaigns Reach Across the American Political Spectrum.” Misinformation Review 1 (1): 1–9.

- Freelon, D., and C. Wells. 2020. “Disinformation as Political Communication.” Political Communication 37 (2): 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1723755.

- Frydenlund, I. 2023. “Theorizing Buddhist Anti-Muslim Nationalism as Global Islamophobia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268209.

- Ganesh, B. 2020. “Weaponizing White Thymos: Flows of Rage in the Online Audiences of the alt-Right.” Cultural Studies 34 (6): 892–924. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1714687.

- Ganesh, B., and C. Froio. 2020. “A ‘Europe des Nations’: Far Right Imaginative Geographies and the Politicization of Cultural Crisis on Twitter in Western Europe.” Journal of European Integration 42 (5): 715–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1792462.

- Ganesh, B., I. Frydenlund, and T. Brekke. 2023. “Flows and Modalities of Global Islamophobia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268192.

- Gardell, M. 2015. “What’s Love Got to Do with It?” Journal of Religion and Violence 3 (1): 91–115. https://doi.org/10.5840/jrv20155196.

- Gaudette, T., R. Scrivens, G. Davies, and R. Frank. 2021. “Upvoting Extremism: Collective Identity Formation and the Extreme Right on Reddit.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3491–3508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820958123.

- George, C. 2021. “Hate Propaganda.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Disinformation and Populism, edited by H. Tumber and S. Waisbord, 80–91. London: Routledge.

- Golovchenko, Y., C. Buntain, G. Eady, M. A. Brown, and J. A. Tucker. 2020. “Cross-Platform State Propaganda: Russian Trolls on Twitter and YouTube During the 2016 U.S.” Presidential Election. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (3): 357–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220912682.

- Hervik, P. 2019. “Denmark’s Blond Vision and the Fractal Logics of a Nation in Danger.” Identities 26 (5): 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2019.1587905.

- Hoffman, M., F. R. Bach, and D. M. Blei. 2010. “Online Learning for Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 23: 9.

- Horsti, K. 2017. “Digital Islamophobia: The Swedish Woman as a Figure of Pure and Dangerous Whiteness.” New Media & Society 19 (9): 1440–1457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816642169.

- Howard, P. N., B. Ganesh, D. Liotsiou, J. Kelly, and C. François. 2018. The IRA, Social Media and Political Polarization in the United States, 2012-2018. Oxford: Project on Computational Propaganda.

- Innes, M., D. Dobreva, and H. Innes. 2021. “Disinformation and Digital Influencing After Terrorism: Spoofing, Truthing and Social Proofing.” Contemporary Social Science 16 (2): 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2019.1569714.

- Jasser, G., J. McSwiney, E. Pertwee, and S. Zannettou. 2021. “Welcome to #GabFam’: Far-Right Virtual Community on Gab.” New Media & Society 25 (7): 1728–1745. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211024546.

- Kalmar, I. 2020. “Islamophobia and Anti-Antisemitism: The Case of Hungary and the ‘Soros Plot’.” Patterns of Prejudice 54 (1–2): 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2019.1705014.

- Kozaric, E., and T. Brekke. 2023. “The Case of WikiIslam: Scientification of Islamophobia or Legitimate Critique of Islam?.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268154.

- Kreiss, D. 2021. “‘Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform,' edited by Nathaniel Persily and Joshua A. Tucker.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 26 (2): 505–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220985078.

- Kumar, D. 2012. Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Kundnani, A. 2014. The Muslims are Coming!: Islamophobia, Extremism, and the Domestic War on Terror. London: Verso Books.

- Kuo, R., and A. Marwick. 2021. “Critical Disinformation Studies: History, Power, and Politics.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 2 (4). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-76.

- Linvill, D. L., and P. L. Warren. 2020a. “Engaging with Others: How the IRA Coordinated Information Operation Made Friends.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1 (2). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-011.

- Linvill, D. L., and P. L. Warren. 2020b. “Troll Factories: Manufacturing Specialized Disinformation on Twitter.” Political Communication 37 (4): 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1718257.

- Lukito, J. 2020. “Coordinating a Multi-Platform Disinformation Campaign: Internet Research Agency Activity on Three U.S. Social Media Platforms, 2015 to 2017.” Political Communication 37 (2): 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1661889.

- Lukito, J., J. Suk, Y. Zhang, L. Doroshenko, S. J. Kim, M.-H. Su, Y. Xia, D. Freelon, and C. Wells. 2020. “The Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing: How Russia’s Internet Research Agency Tweets Appeared in U.S.” News as Vox Populi. The International Journal of Press/Politics 25 (2): 196–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219895215.

- Manovich, L. 2020. Cultural Analytics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Matamoros-Fernández, A. 2017. “Platformed Racism: The Mediation and Circulation of an Australian Race-Based Controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (6): 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130.

- May, R., and M. Feldman. 2018. “Understanding the Alt-Right. Ideologues, ‘Lulz’ and Hiding in Plain Sight.” In Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right, edited by M. Fielitz and N. Thurston, 25–36. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839446706-002.

- Mejia, R., K. Beckermann, and C. Sullivan. 2018. “White Lies: A Racial History of the (Post)Truth.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 15 (2): 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2018.1456668.

- Menon, P. 2023. “Babri Retold: Rewriting Popular Memory Through Islamophobic Humor.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2023.2268152.

- Miller-Idriss, C. 2020. Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mondon, A., and A. Winter. 2017. “Articulations of Islamophobia: From the Extreme to the Mainstream?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (13): 2151–2179. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1312008.

- Mondon, A., and A. Winter. 2020. Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream. London: Verso Books.

- Mudde, C. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity.

- Nikunen, K., J. Hokka, and M. Nelimarkka. 2021. “Affective Practice of Soldiering: How Sharing Images Is Used to Spread Extremist and Racist Ethos on Soldiers of Odin Facebook Site.” Television & New Media 22 (2): 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982235.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pearce, W., S. M. Özkula, A. K. Greene, L. Teeling, J. S. Bansard, J. J. Omena, and E. T. Rabello. 2020. “Visual Cross-Platform Analysis: Digital Methods to Research Social Media Images.” Information, Communication & Society 23 (2): 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486871.

- Pertwee, E. 2020. “Donald Trump, the Anti-Muslim far Right and the New Conservative Revolution.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43 (16): 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688.

- Polyakova, A. 2014. “Strange Bedfellows: Putin and Europe’s Far Right.” World Affairs 177 (3): 36–40.

- Poole, E., E. H. Giraud, and E. de Quincey. 2021. “Tactical Interventions in Online Hate Speech: The Case of #StopIslam.” New Media & Society 23 (6): 1415–1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820903319.

- Reddi, M., R. Kuo, and D. Kreiss. 2023. “Identity Propaganda: Racial Narratives and Disinformation.” New Media & Society 25 (8): 2201–2218. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211029293.

- Rose, G., and A. Willis. 2019. “Seeing the Smart City on Twitter: Colour and the Affective Territories of Becoming Smart.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (3): 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818771080.

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2017. Russia and the Western Far Right: Tango Noir. London: Routledge.

- Spencer, R. B. 2017, March 22. Walk on by … . [Tweet]. Twitter. http://web.archive.org/web/20170327224905/https://twitter.com/RichardBSpencer/status/844632152692043776.

- Tebaldi, C. 2021. “The Terrorist and the Girl Next Door: Love Jihad in French Femonationalist Nonfiction.” Religions 12 (12): 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121090.

- Texas Lone Star. [@SouthLoneStar]. 2017, March 22. Muslim Woman Pays No Mind to the Terror Attack, Casually Walks by a Dying Man While Checking Phone #PrayForLondon. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://web.archive.org/web/20170322212423/https:/twitter.com/SouthLoneStar.

- Thorleifsson, C. 2018. Nationalist Responses to the Crises in Europe: Old and New Hatreds. London: Routledge.

- Thorleifsson, C. 2019. “The Swedish Dystopia: Violent Imaginaries of the Radical Right.” Patterns of Prejudice 53 (5): 515–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2019.1656888.

- Tuters, M., and S. Hagen. 2020. “(((They))) Rule: Memetic Antagonism and Nebulous Othering on 4chan.” New Media & Society 22 (12): 2218–2237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819888746.

- Twitter. 2022. Information Operations. Twitter Transparency. https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/information-operations.html.

- United States of America v. Internet Research Agency. LLC et al. (United States District Court for the District of Columbia 2018). https://www.justice.gov/file/1035477/download.

- Vidgen, B., and T. Yasseri. 2020. “Detecting Weak and Strong Islamophobic Hate Speech on Social Media.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 17 (1): 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2019.1702607.

- Walker, R. F. 2021. The Emergence of “Extremism”: Exposing the Violent Discourse and Language of “Radicalisation.”. London: Bloomsbury.

- Walter, D., Y. Ophir, and K. H. Jamieson. 2020. “Russian Twitter Accounts and the Partisan Polarization of Vaccine Discourse, 2015–2017.” American Journal of Public Health 110 (5): 718–724. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305564.

- Watson, P. J. [@PrisonPlanet]. 2017, March 22. #London. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://web.archive.org/web/20220829080536/https://twitter.com/PrisonPlanet/status/844613836036550656.

- Wigger, I. 2019. “Anti-Muslim Racism and the Racialisation of Sexual Violence: ‘Intersectional stereotyping’ in Mass Media Representations of Male Muslim Migrants in Germany.” Culture and Religion 20 (3): 248–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2019.1658609.

- Williams, M. L., P. Burnap, A. Javed, H. Liu, and S. Ozalp. 2020. “Hate in the Machine: Anti-Black and Anti-Muslim Social Media Posts as Predictors of Offline Racially and Religiously Aggravated Crime.” The British Journal of Criminology 60 (1): 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz049.

- Wodak, R. 2020. The Politics of Fear: The Shameless Normalization of Far-Right Discourse. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Xia, Y., J. Lukito, Y. Zhang, C. Wells, S. J. Kim, and C. Tong. 2019. “Disinformation, Performed: Self-Presentation of a Russian IRA Account on Twitter.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (11): 1646–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1621921.

- Young, J. C. 2021. “Disinformation as the Weaponization of Cruel Optimism: A Critical Intervention in Misinformation Studies.” Emotion, Space and Society 38: 100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100757.