ABSTRACT

Contact hypothesis and threat hypothesis are among the most influential theories of xenophobia. The former proposes that intergroup contact may reduce prejudice. The latter suggests that a large outgroup may increase xenophobic attitudes.

Using data of a 2018 German representative sample (N = 2,016), we employed multilevel analyses. As predictors, we looked at outgroup size, gross domestic product, and unemployment rate on a county level. On the individual level, we included authoritarianism and a wide range of sociodemographic variables.

Individual authoritarianism was identified as the strongest predictor of xenophobic attitudes. On the county level, a higher proportion of migrants was associated with lower values of xenophobia. This serves as an indicator for contact hypothesis. Our results suggest that contextualizing social psychological and micro-sociological theories and employing multilevel analyses are valuable tools to detangle the interplay of individual and contextual influences on xenophobic attitudes.

Introduction

Racism and xenophobia are among the major issues of many modern societies. In an increasingly complex and globalized world, the fear of an outgroup that is perceived as foreign and potentially dangerous may not only hinder scientific and economic progress but also calls into question the foundations of democratic societies, as it promotes a world view of inequality. For example, the number of xenophobic hate crimes increased by 72.4% in 2020 compared to 2019 (BMI Citation2021). Similar trends have been reported for Denmark, Finland, and Slovakia (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Citation2021). Even though xenophobic attitudes may not be directly translated into criminal actions, they serve as a good indicator for xenophobic action potential within a society. Monitoring and explaining xenophobic attitudes are thus important to assess and fight these tendencies.

Xenophobic attitudes are connected to many other forms of generalized prejudices against minorities (Zick et al. Citation2008) and they are considered one of the major dimensions of right-wing extremist attitudes (Decker, Kiess, and Brähler Citation2022). Moreover, they may predict right-wing voting behavior and the acceptance of violence (Decker, Kiess, and Brähler Citation2022; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Citation2002). Perceived discrimination, on the other hand, may lead to lower self-esteem and higher levels of psychological distress, like depression and anxiety (Schmitt et al. Citation2014).

This study aims to enhance research on associations between xenophobic attitudes and contextual attributes. To this end, we will put contact hypothesis and threat hypothesis as two of the most widely studied approaches to include contextual information on a theoretical level to an empirical test using multilevel regression models with cross-level interactions and thus combining individual level information with contextual (county level) attributes. While this has been done in a similar manner before with mixed results, we will be adding authoritarianism as an important individual level parameter that is thought to influence xenophobic attitudes both directly and indirectly through threat perception (Asbrock and Fritsche Citation2013). Furthermore, as previous research showed that xenophobic attitudes are more prevalent in the former Eastern states of Germany (Decker, Kiess, and Brähler Citation2022), we will test if this still holds when controlling for contextual information on the finer-grained county level.

Theoretical background

In order to analyze possible causes of xenophobic attitudes, different levels of analysis have to be taken into consideration: the individual, micro level, the group-focused meso level, as well as the context or macro level. This theoretical distinction is to be understood as a prototypical one, as the three levels are necessarily interrelated, and some factors may function on different levels simultaneously or interact with factors on other levels. Nonetheless, this systematization may help understand the nature of different theoretical approaches.

On an individual level, Adorno et al.’s (Citation1950) much cited theory of the authoritarian character tries to explain the development of stereotypes and prejudice focusing on factors of socialization. They see authoritarianism as a character trait consisting of nine dimensions that is largely influenced by early childhood experiences and may lead to several forms of prejudice later in life (Frenkel-Brunswik Citation1996). Additional macro and meso influences are described in the publication in 1950 but are not systematically integrated into the theory. Since its development, Altemeyer’s (Citation1998) revision of the theory and the revised measurement instrument have often been used in social science research. He postulates that authoritarianism consists of three dimensions instead of the original nine: Authoritarian submission describes an individual’s tendency to follow the lead of a strong ruler, authoritarian aggression captures the extent to which a person is prone to punish (socially) deviant behavior, and conventionalism measures the willingness to stick to established rules of conduct (Altemeyer Citation1998; Beierlein et al. Citation2014; Bizumic and Duckitt Citation2018; Heller et al. Citation2022). It is considered a set of attitudes that is learned through social interactions and altered by certain situational factors and political situations, for example, it is known to increase when the individually perceived threat on security is high (Dunwoody and Plane Citation2019).

Other individual characteristics are also known to have a connection to xenophobic attitudes: Research almost unanimously agrees that education serves as a buffer for xenophobic attitudes, as the latter decrease with higher educational attainment (e.g. Borgonovi and Pokropek Citation2019). Even though the exact workings of this predictor variable remain unclear (e.g. whether this is due to the kind of family background that often times comes along with higher education or some characteristics of the school, the teachers, or the content being taught), education is frequently, but not always, the factor with the single most predictive power (Carnevale et al. Citation2020; Meloen, Van der Linden, and De Witte Citation1996). Regarding gender differences, men seem to endorse xenophobic attitudes more often than women do (Decker, Kiess, and Brähler Citation2022). Rippl and Boehnke (Citation2016) argue, however, that there is no main effect of gender, but differences arise as xenophobia becomes more aggressive. Moreover, there seems to be an age gradient with older people expressing higher agreement to xenophobic statements. Ruffman et al. (Citation2016) give two possible explanations for this observation: On the one hand, the normative view attributes it to cohort differences with older adults being socialized in a time where prejudices were more socially acceptable. On the other hand, psychosocial aging might diminish executive functions and results in a certain reluctance to change and/or fear of the unknown. Finally, low income and current unemployment are known to influence intergroup processes on the meso level (see below) and therefore need to be controlled.

On the macro level, Germany poses an interesting case of investigation due to its history of division into the socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German states), and the democratic Federal Republic of Germany (West German states). After the Second World War, both states showed fundamental differences in organizing social life. While the West adapted a capitalist free-market system, the East followed a communist model that decreased productivity but also led to high employment rates, as more people were being employed than there was work to do (BMWi Citation2020). Due to its anti-fascist reason of state, anti-Semitic, xenophobic, and racist expressions were by definition non-existent. While this led to a more thorough persecution of those involved in the barbary of the Second World War, it soon became apparent that xenophobic assaults were being covered up, in order to maintain that image (Waibel Citation1996). After the fall of the Berlin Wall, there was a steep increase in xenophobic and politically right-wing violence that is often times interpreted as a breakthrough of latent xenophobic attitudes (Pollack Citation2020). More than 30 years after the unification, there are still large social and economic differences between the East and the West: While the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has almost tripled in the East since 1990, it is still only at 73% compared to the West today; unemployment rates have also been decreasing but are still higher in the East (BMWi Citation2020). While the proportion of immigrants is known to be much lower in the East (Destatis Citation2021), right-wing populist parties like the “Alternative für Deutschland” (AfD) have been far more successful (Lengfeld and Dilger Citation2018), and xenophobia has been reported to be a larger problem in the East than in the West (Decker, Kiess, and Brähler Citation2022; GESIS Citation2019). The question remains whether this is caused by prevailing economic differences or some sort of different mentality caused by the history of division.

In this study, we not only take into consideration the effect of individual factors on anti-foreign sentiment like authoritarianism. We also include different meso level context variables on a county level, namely the GDP, the unemployment rate, and the share of migrants, to investigate their effects on xenophobic attitudes also in combination with individual predispositions, including authoritarianism. There have been two main underlying mechanisms proposed to explain the distinct effects of these structural factors: Allport’s (Citation1954) intergroup contact hypothesis and threat theory (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000).

Contact hypothesis

Allport (Citation1954) originally claimed that contact with an outgroup may reduce stereotypical views and prejudices against that group. It is much lesser known that he also specified general conditions necessary for the contact hypothesis to take effect: (1) The stereotypes had to be consciously accessible in order to be reduced; (2) the individuals involved were willing to change their stereotypes. The latter was to be facilitated by similar statuses, goals, and interests as well as positive social and political sanctioning of intergroup contact. Even though the idea of favorable contact became a heavily researched topic (e.g. Schwartz and Simmons Citation2001) and the importance of intergroup friendships cannot be denied (Zhou et al. Citation2019), a large meta-analytic review by Pettigrew and Tropp (Citation2006) concluded that the general conditions were not essential to the positive effects of intergroup contact: 94% of the 515 studies under investigation found intergroup contact to reduce prejudice, independent of sampling method, publication bias, or type of outgroup. Following previous results on outgroup size (Schlueter and Wagner Citation2008; Schlueter and Scheepers Citation2010), we believe a large outgroup may provide the structure and offer opportunities to interact. Through that, prejudices may be reduced.

Threat hypothesis

Somewhat contrary to contact hypothesis, many researchers have argued that a large outgroup will increase the perception of economic (realistic) and cultural (symbolic) threat (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000). They claim that prejudice is driven by a conflict about resources between majority and minority groups (Blalock Citation1967; Blumer Citation1958). A large outgroup may become a realistic threat, endangering the economic wealth of the majority group especially in deprived regions with scarce economic resources (i.e., regions with low average income, low GDP, high unemployment, and crime rates, Steininger and Rotte Citation2009). This trend was recently empirically confirmed for the effect of employment rate as an indirect effect via fraternal deprivation on individual threat using data from the migration module of the European Social Survey (Meuleman et al. Citation2020). It is also supported by the finding that in areas with worse sociodemographic conditions, the attenuating effect of the number of migrants on xenophobic attitudes is decreased (Hoxhaj and Zuccotti Citation2021). As opposed to that, symbolic threats are directed towards cultural norms that may be challenged by a large outgroup. Applied to the field of attitudes towards immigration, one consequence of this theoretical argument is that with increasing objective size of the immigrant population, negative attitudes toward this group increase.

Using a geographically weighted regression, Teney (Citation2012) tested the group threat hypothesis, differentiating between the German right-wing “Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands” (NPD) election outcomes on the county level in East and West Germany. As a result, she found that the election outcomes in most of the West German cities are not significantly affected by changes in immigrant and unemployment rates. In contrast, in East German cities as well as Northern Bavaria, NPD’s electoral success is increasing with a higher proportion of migrants and unemployment. Cities near the former border between East and West Germany exhibit the largest significant positive association of the electoral outcome and unemployment, which leads to the assumption that group threat is a significant factor in these regions.

However, studies show that it is not only the contextual factors themselves that function as drivers of anti-foreign sentiment, but that they also interact with and are moderated by the subjective evaluation and perception of the situation. Using samples from 17 European countries, Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2020) showed that perceived size of a minority may moderate the direct effect of objective outgroup size on attitudes toward the migrant population on the national level. Semyonov et al. (Citation2004) could prove the same dynamics for Germany on the county level. Finally, in the study of Schlueter and Scheepers (Citation2010) the contradictory effects of both contact and threat as intervening constructs between objective size and attitudes toward foreigners were empirically confirmed; while subjective perceptions of a larger outgroup size are associated with increasing anti-immigrant attitudes through threat perception, a larger objective group size facilitated intergroup contact and thus diminishes threat and ultimately anti-immigrant attitudes. Cross-level interactions between individual, micro level factors and contextual, macro level factors thus need to be taken into account when analyzing xenophobic attitudes.

Methodological considerations

Most research that found a diminishing effect of contact with outgroups on prejudice used linear regression models, thereby disregarding the possibility of non-linear effects. In fact, distinguishing between non-EU 15-nationalsFootnote1 and other immigrant groups, Weins (Citation2011) showed that an increasing rate of migrants in the area is associated with lower values of prejudice until this proportion exceeds the mark of 9% of non-EU 15-nationals. Past this point, the effect decreases. A similar curvilinear result is found by Janssen et al. (Citation2019) in the Netherlands: People who live in neighborhoods with 30–50% non-western ethnic minorities are most likely to vote for the Dutch right-wing party PVV (“Partij voor de Vrijheid”).

Moreover, linear regressions tend to ignore similarities of groups living in similar social contexts (i.e., neighborhoods, counties, states, or nations). These similarities may be central to a fundamental understanding of the interaction between the individual and its social context. To this end, multilevel analyses may be a useful statistical tool, as it not only allows to systematically integrate higher level contextual information into the models, but also to postulate and test cross-level interactions, that is individual level and context level predictors interacting in their effect on the outcome variable. Research on xenophobia has in fact been greatly enhanced by using multilevel frameworks and including regional data, like the proportion of migrants or unemployment rates on a regional level. Weber (Citation2015), for example, analyzed AfD state election outcomes and showed that on the county level, higher proportions of migrants lead to a more positive view on migration. Nevertheless, tolerant citizens seem to live in neighborhoods with a smaller proportion of migrants, whereas locals tend to leave areas with a higher proportion, and they are more likely to vote for the AfD (ibd.). Different units of analysis as context units may thus lead to different results. This finding was also confirmed by the recent meta-analysis of Pottie-Sherman and Wilkes (Citation2017) looking at 55 studies regarding the impact of outgroup size on xenophobic attitudes. Results were inconclusive, varying due to different operationalization and measures of outgroup size and xenophobia as well as different units of analysis as context units (e.g. neighborhoods, counties, states, nations). Furthermore, important individual level predictors that are known to influence prejudice (like authoritarianism), have often been ignored and cross-level interactions are rarely analyzed.

Regarding cross-level interactions, the abovementioned studies on perceived and objective threat exemplify that objective factors (e.g. indicators for structurally deprived regions or the share of migrants) are interrelated with subjective predispositions and evaluations (like authoritarianism, subjective deprivation, or perceived threat) when it comes to prejudice formation. Using multilevel analyses, a recent study by Heller et al. (Citation2022) found that individuals express more authoritarian attitudes if they live in a district with higher average income but evaluate the economic situation in Germany as worsening. The authors interpret the results as a fear of social decline that fires an authoritarian dynamic. Based on this finding as well as the theoretical considerations outlined above, we in turn hypothesize that individuals that already express more authoritarian attitudes, and are thus prone to prejudice, will be especially influenced by contextual factors when it comes to anti-foreign sentiments, that is, the effect of authoritarianism on xenophobia will be stronger in districts with a lower GDP, a higher unemployment rate, and a larger migrant population, as the latter will be perceived as especially threatening.

Objective of the study

Based on these considerations, we will be testing the following hypotheses using a multilevel approach with variables on the contextual level (level 2; 204 of the 401 German counties) as well as the individual level (level 1; 1,792 individuals).

Level 2 hypotheses:

As the effect of threat and contact are contradictory and their exact effect sizes are not known a priori, we cannot predict the effect of the migrant share on attitude toward foreigners (Schlueter and Scheepers Citation2010; Wagner et al. Citation2006). We will take a positive connection, that is, a larger proportion of migrants in a county intensifying the individual expression of xenophobia, as evidence for the threat hypothesis, while a negative association, that is, an attenuating effect of the migrant share, would serve as evidence for the contact hypothesis.

Following threat hypothesis, we expect that a higher unemployment rate in a county leads to a more negative attitude toward foreigners.

Finally, we expect that the lower the GDP per capita in a county, the more negative is the attitude toward foreigners.

Level 1 hypotheses:

| (4) | We hypothesize that authoritarianism is a major driver of anti-foreigner sentiment. | ||||

| (5) | Due to the prolonged differences between the East and West German regions, we assume that the place of residence will additionally influence xenophobic attitudes in that they will be higher in the former East German counties compared to the West even when controlling for other individual and contextual factors. | ||||

Cross-level interaction hypotheses:

As authoritarianism is connected to certain context variables like structural deprivation and threat perception, we hypothesize that.

| (6) | Increasing size on level 2 will intensify the effect of level 1 authoritarianism on anti-foreigner sentiments and | ||||

| (7) | increasing unemployment rate in a county will intensify the effect of authoritarianism on anti-foreigner sentiments. | ||||

| (8) | Alarger GDP per capita, on the other hand, will decrease the effect of authoritarianism on xenophobia. | ||||

Further, based on empirical evidence (Weins Citation2011), we will also be testing a curvilinear effect of the proportion of migrants on xenophobia. Also, to account for their association with xenophobia, education and individual employment will serve as further sociodemographic control variables.

We see our study as a fruitful addition to existing literature on the topic for several reasons. The multilevel approach has rarely been used on a district level to differentiate the distinct effects of individual and context level factors as well as cross-level interactions. Moreover, we were able to include variables that, based on theoretical considerations and previous analyses, will be very relevant for anti-foreign sentiments: As authoritarianism has been identified as one of the major drivers in prejudice formation and it has been shown to be sensitive to structural factors, it is likely to also play a central role regarding xenophobic attitudes as well. The inclusion of authoritarianism as a predictor variable will thus help to further shed light on dynamics of anti-democratic and anti-modern ressentiments. Further differentiation will be possible due to the usage of unemployment on both the individual as well as the county level. With our study, we hope to shed further light on the complex interplay of individual and contextual influences on xenophobic attitudes.

Method

In the following, we will give an overview of the sampling method, characteristics of the final sample, as well as measures and the statistical analyses.

Sample and procedure

The sample was based on a representative survey by the University of Leipzig in 2018. The data was collected by a commercial survey institute (Independent Service for Survey, Methods and Analysis; USUMA) using a multi-stage random-route-technique. First, participating households were selected using 258 sample points throughout Germany that revealed that 5,418 households should be contacted as part of the study. Of these, 102 households had to be excluded as they were vacant or without individuals meeting the inclusion criteria. Within the households, Kish selection grid was applied to select the target person. Participation rate of eligible households was 47.5%. For 11 interviews, analysis was not possible, leading to a final sample size of N = 2,516.

All participants gave their informed consent and were first interviewed by trained interviewers, face-to-face, in their homes. After the sociodemographic interview, participants were asked to fill out questionnaires regarding political attitudes as well as physical and psychological symptoms. Interviewers were present in case of questions but did not interfere. The inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 14 years as well as the ability to understand the German language in spoken and written form. In the case of minors (less than 18 years of age), additional informed consent was provided by at least one parent, caretaker, or guardian.

Given our topic of investigation of attitudes towards foreigners, we excluded first and second-generation migrants from the study (n = 378). For this purpose, migrants are defined as follows: (1) people who do not have German citizenship, or (2) people who have German citizenship, but were born in other countries, plus, at least one of the parents was either not born in Germany or does not have German citizenship. In addition, due to the special status of Berlin during the division of Germany and the later unification, we decided to exclude all participants from Berlin (n = 122).Footnote2 Finally, we excluded all participants with missing values. This led to a sample size of N = 1,792. A detailed sociodemographic description of the sample stratified by region of residence in either East or West Germany can be found in .

Table 1. Variables of the model classified by region of residence.

Measures

To measure endorsement of xenophobic attitudes, we used the subscale xenophobia of the Leipzig scale on right-wing extremist attitudes (Fragebogen zur rechtsextremen Einstellung – Leipziger Form; FR-LF; Decker et al. Citation2013). It consists of the following three items to be judged by the participants:

Foreigners only come here to abuse the welfare system.

When jobs are scarce, foreigners should be sent home.

Germany is losing its identity because of the large number of foreigners.

Compared to other measures of xenophobia, this questionnaire mainly captures the cognitive component of the attitude towards foreigners (e.g. Eagly and Chaiken Citation1993). Participants indicated their agreement to each statement on a five-point scale ranging from 1 “I completely disagree” to 5 “I completely agree”. The subscale as well as the questionnaire as a whole showed excellent psychometric properties with internal consistencies of McDonald’s Omega ω = .88 and .96 respectively (Heller, Brähler, and Decker Citation2020a). A sum score was used for those participants that filled out the entire questionnaire.

On the individual level, authoritarianism was captured using the three-item scale Authoritarianism – Ultra short (A-US; Heller et al. Citation2020b) that is based on the well-validated Short Scale for Authoritarianism (Kurzskala Autoritarismus; Beierlein et al. Citation2014). The A-US is a one-dimensional scale that reflects the three dimensions proposed by Altemeyer (authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism Citation1998) using one item each. Agreement to each statement had to be indicated using a five-point scale with 1 indicating strong opposition and 5 indicating strong agreement. Confirmatory factor analysis verified the unidimensionality of the scale and internal consistency was adequate (ω = .68 to .71; Heller et al. Citation2020b). A sum score was calculated using the three answers. Item wording of both the A-US and the FR-LF items in English and German may be found online (Online Resource 1).

Regarding further individual level variables, educational background was split into three categories based on educational attainment: low (an equivalent of less than 10 years of schooling), medium (an equivalent of approx. 10 years), and high (more than 10 years), to make it more accessible and easier to compare. Individual employment status was dichotomized (1 = employed, 0 = currently unemployed) and net equivalent household income was approximated by using the mean of the participant’s household income category and dividing it by the square root of the number of people in the household. Sex was also dichotomized (1 = male, 2 = female). Age was included as a metric variable.

As to the context information on level 2, unemployment rate at county level for the year 2018 was taken from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (destatis). The information of the GDP at county level was provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development for the year 2017 (BBSR Bonn Citation2020). For the proportion of migrants, destatis was commissioned to obtain this information at the county level (n = 204). It was requested separately from each county and was therefore carried out as a special-order assignment. The county level specification of migration focuses on citizenship at birth. Those who were born in a country other than Germany were considered migrants. Their number relative to all inhabitants in a district is used as the share of migrants within this county. To reduce multicollinearity, we centred the proportion of migrants, its squared form, the GDP, as well as authoritarianism in the multilevel analysis.

Statistical analysis

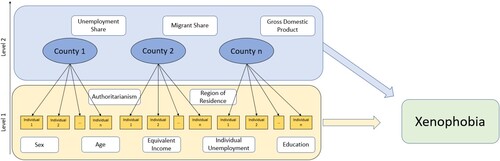

In addition to the descriptive analyses and correlations stratified by place of residence in either East or West Germany, we performed a stepwise multilevel analysis with two levels: (1) individual and (2) county level. gives an overview of our predictors on the separate levels: Our level 1 variables reflect the subjective statements of the participants regarding authoritarianism, as well as sex, age, education background, employment status, and equivalent household income. The grouping variable on level 2 is based on the German counties. Furthermore, we computed cross-level interactions between the level 1 variable authoritarianism and certain level 2 variables to allow the context variables to serve as and interact with this predictor at level 1. Finally, we computed the standardized β to make the different scales comparable. The stepwise procedure included three stages: First, the variables on level 1 were implemented in the analysis. This can be viewed as a regular linear regression approach. In a second model, the variables on level 2 were added and changes in the effects of all predictors were evaluated. The third and full model integrated the variables on the levels 1 and 2 as well as the cross-level interactions. This way, the additional explained variance of the multilevel approach can be best described (Raudenbush and Bryk Citation2002). Using Likelihood-ratio (LR) tests as well as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC, Akaike Citation1973), we evaluated whether the inclusion of additional variables indeed lead to a better model. A significant LR test as well as a lower AIC were used as indicators for a better model.

Figure 1. Individual level (Level 1) and county level (Level 2) predictors for xenophobic attitudes. Cross-level interactions are not depicted.

We conducted all multilevel analyses for the present investigation in RStudio (RStudio Team Citation2021) using the package lme4 and lmerTest (Bates et al. Citation2015; Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, and Christensen Citation2017).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

First, we examined item characteristics to analyze normal distribution and to identify the proportion of missing values for Germany as a whole, as well as East and West Germany (Online Resource 2). Regarding the xenophobia scale, normal distribution can be assumed as both skewness and kurtosis fall under the cutoff of < 2 (Pituch and Stevens Citation2016). The missing values are also within limits of less than 5% (Schafer and Graham Citation2002), so that we assume that the missing values do not have a relevant impact.

For the authoritarianism scale, we also assume a normal distribution, and again the missing values do not seem to be systematic in either region or in Germany as a whole (Online Resource 3).

As demonstrates, participants living in Eastern Germany show higher scores in both xenophobia and authoritarianism than those living in Western Germany. The proportion of people with migration background in Eastern German counties is lower than in Western German counties. Finally, the unemployment rate is higher in East German counties than in West German counties (). Apart from these attitudes and level 2 variables, sociodemographic distributions also vary significantly between East and West Germany. The sample contains significantly more unemployed participants from East Germany (p < .01). Moreover, the equivalent household income is significantly lower in the East. A one-way ANOVA shows that all reported differences between East and West Germany, with the exception of the employment status, are highly significant with a p-value < .001.

In Online Resource 4, we report Pearson correlations (r) between the predictors and xenophobia in Germany as a whole. An Eta coefficient (η) was used for the nominal variables sex and employment status, Kendall’s Tau b (τb) measures the correlation between the ordinal variable of education and the metric xenophobia. We consistently find highly significant correlations between xenophobia and education, authoritarianism, equivalent household income, the proportion of people with migration background in the county, and the GDP (p < .001). Of these, authoritarianism (r = .47) and education (τb = -.21) showed the highest correlations with xenophobia. The individual employment status also displays a low, but significant correlation with xenophobia (η = .05; p < .05). Of our predictors, only unemployment rate on the county level is non-significant. As expected, authoritarianism is positively associated with xenophobia, while education, income, and the proportion of people with migration background in the county all show a negative association. Considering Germany as a whole, current unemployment on an individual level is negatively related to xenophobic attitudes, suggesting that those participants currently unemployed show higher values of xenophobia.

These correlations differ only slightly between East and West Germany. While sex is not a significant predictor when looking at East and West Germany separately, it becomes significant when considering Germany as a whole with women generally displaying lower values. Age is not a significant predictor of xenophobia in East Germany (p = .12), while it is low, but highly significant in the West (r = .13; p < .001). In both regions, education correlates negatively on a high level of significance (p < .001), with the coefficient being even higher in the East compared to the West (τb = -.34 vs. τb = -.22). Individual level unemployment significantly correlates with xenophobia only in the East and in Germany as a whole. Furthermore, the connection of authoritarianism and xenophobia is slightly higher in the East compared to the West (r = .49 vs. r = .46; p < .001). Equivalent household income shows a relatively low, but significant connection to xenophobia (East: r = -.15, p < .01; West: r = -.11, p < .001). On the county level, unemployment rate is significantly correlated with xenophobia (r = -.07; p < .05) only in West Germany. The correlation between the proportion of migrants on the county level and xenophobia is slightly higher in East Germany (r = -.11 vs. r = -.10), but on a lower significance level (p < .05 vs. p < .001). Findings with a lower or no level of significance in East Germany may be due to the smaller sample size. Finally, while the correlation between the GDP and xenophobia is non-significant in West Germany (r = −0.03, p = .28), it is highly significant in the East (r = −0.19, p < .001), with a lower GDP being associated with higher values of xenophobia.

Multilevel analyses

depicts the results of the stepwise multilevel analysis. First, solely the level 1 variables are implemented. Female sex has a significant negative impact on xenophobia in all models (std. β = −0.13, std. p < 0.001). Compared to low education, medium (std. β = −0.21, std. p < 0.001) or high education (std. β = −0.42, p < 0.001) significantly reduce xenophobic attitudes. Increasing equivalent household income also has a diminishing impact on xenophobic attitudes (std. β = −0.05, std. p < 0.05).Footnote3 The employment status has a negative, but non-significant effect on xenophobia (std. β = −0.14, std. p = 0.082). Unemployment was associated with higher values of xenophobia. Finally, as expected, higher values on the authoritarianism scale increase xenophobia (std. β = 0.33, std. p < .001).

Table 2. Results of the stepwise multilevel analysis.

The coefficients and significance levels hardly change when adding level 2 variables or the cross-level-interactions, except for the region of residence: Only in this first model, the location in West Germany has a significantly attenuating impact on xenophobia (std. β = −0.34, std. p < 0.01) which reduces to a std. β of −0.03 (n.s.) when the level 2 variables are introduced.

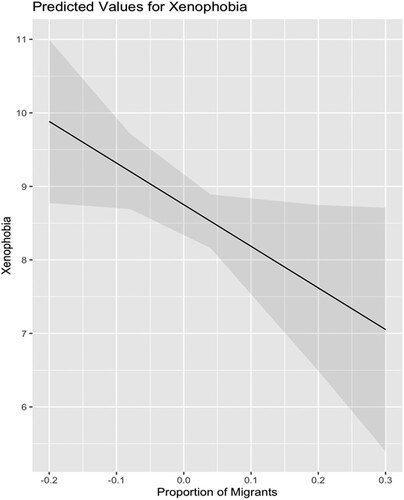

Among the variables on level 2, only the proportion of migrants has a significant impact on xenophobia (std. β = −0.18, std. p < 0.05). displays the connection of the proportion of migrants on a county level with individual levels of xenophobia. Our results do not suggest a curvilinear impact of the share of migrants (std. β = 0.04, std. p = 0.538).Footnote4 Both unemployment rate on the county level as well as the GDP per capita do not significantly impact individual level xenophobia.

Figure 2. Connection of the proportion of migrants at county level with the predicted individual level xenophobia. As the former has been centered, values may fall below 0.

The last model is the full model because it implements all the variables on levels 1 and 2 as well as the cross-level interactions. Cross-level interactions between the proportion of migrants as well as the unemployment rate in the county (level 2) and authoritarianism (level 1) indicate no significant influence. In contrast, the cross-level interaction between the GDP (level 2) and authoritarianism (level 1) is significantly positive (std. β = 0.06, std. p < .05).

Compared to the first model (including only the individual level variables), the second model (including individual and contextual variables) has more explanatory power, since the results of the LR tests shows a value of p < .05. The AIC is lower, indicating a good parsimony. The full model’s explanatory power is in turn better than that of the model neglecting the cross-level-interactions (p < .01), but the AIC is higher. The proportion of variance explained by differences between counties, our level 2 units, is considerable with about 36% (ICC = .36; Hoxhaj and Zuccotti Citation2021). The remaining variance is explained by the individual (level 1) predictors.

The variability explained by the fixed effects at level 1 (marginal R² = .223) can be rated as a medium to large. The proportion of total variance explained through both fixed effects at level 1 and random effects at level 2 (conditional R² = .499) is at the verge of being considered large (Cohen Citation1988). Including the contextual variables thus increases the predictive power of the model.

gives an overview of our findings regarding our hypotheses. In favor of contact hypothesis, our results suggest that the proportion of migrants may attenuate xenophobic attitudes. Neither the GDP nor the unemployment rate at county level show a significant direct impact. Regarding our level 1 hypotheses, we indeed find a positive connection of authoritarianism and xenophobic attitudes but the effect of the place of residence does not remain significant when including context variables. Only the cross-level interaction between the GDP and authoritarianism is significant. A higher GDP per capita in a county thus increases the effect of authoritarianism on xenophobic attitudes. Regarding the control variables, no curvilinear effects are present. Education and equivalent household income serve as buffers for xenophobic attitudes. Individual unemployment and age have no significant influence.

Table 3. Comparison of hypotheses and empirical outcomes.

Discussion

In this paper, we used multilevel analyses to differentiate individual level and contextual variables in their effect on xenophobic attitudes in Germany. We were especially interested in the effect of the contextual variables: objective size of the population of migrants, the unemployment rate of counties, and the GDP on the county level. In our study, we aimed to test two contrary and competing hypotheses regarding the effect of context variables on individual attitudes: We took a positive effect of the proportion of migrants in a county as evidence for contact hypothesis and a negative effect of proportion of migrants as well as a positive effect of the unemployment rate and a negative effect of the GDP as evidence for threat hypothesis. Overall, we found a positive effect of the proportion of migrants and no effect of either the unemployment rate or the GDP even when controlling for individual parameters. No non-linear effects of the proportion of migrants were present either. With this finding, we were able to replicate evidence for contact hypothesis using a more close-grained contextual variable than previous studies in Germany. Moreover, with our multilevel study design, we were able to take into consideration the influence of various individual characteristics, like authoritarianism, education, region of residence and more, as well as possible cross-level interactions.

In line with previous findings (Billig and Cramer Citation1990; Cohrs and Asbrock Citation2009; Peresman, Carroll, and Bäck Citation2021), we identified individual authoritarianism as the strongest individual predictor of individual anti-foreign sentiments. Contrary to expectations, we did not find any cross-level interactions between the proportion of migrants and unemployment on the county level and individual authoritarianism, indicating that these context variables do not alter the connection of xenophobic attitudes with authoritarianism. We did, however, find a cross-level interaction between the GDP per capita and authoritarianism. Contrary to our hypothesis, the effect of authoritarianism was intensified by a higher GDP, not a lower value. This could be an indicator that the fear of social decline, that is especially prevalent in wealthier districts, is also relevant when it comes to xenophobia (Heller et al. Citation2022), thus increasing the effect of authoritarianism on xenophobia. To further shed light on underlying mechanisms of the effect of authoritarianism on xenophobic attitudes, future studies should thus include individual threat perception as an intervening variable as well.

We hypothesized that due to historic and continuing differences between the former East and West German countries, there may be an influence of the region of residence on xenophobic attitudes. Interestingly, this effect was found only on the individual level – it disappeared when context variables were introduced. This finding suggests that differences in xenophobia in East and West Germany may be due to the prevailing economic differences as well as fewer contact opportunities with foreigners rather than a specific East German mind set. This is supported by the fact that, when looking at the correlation patterns, individual level unemployment and county level GDP was significantly correlated with xenophobic attitudes only in the East while no such correlation was found in the West.

Regarding the sociodemographic control variables, male sex and lower income was associated with higher levels of xenophobia in all models. Contrary to previous findings on the topic, no significant effect of age or individual unemployment were present in our sample. As expected, we also found education to be a robust influence, reducing negative attitudes toward foreigners. Previous studies have proposed different intervening mechanisms for the effects of education that should be considered in future studies on the topic (Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003).

Limitations and further directions

We now want to discuss relevant limitations of our study. It is possible that nonlinear functions other than our proposed polynomial function may better explain the relation between group size and anti-foreigner sentiments.

In addition, our study measured contact indirectly through the idea that the mere presence of foreigners in a region would create contact opportunities. The actual contact and the quality and valence of that contact could not be taken into consideration. In fact, research on the effects of negative contact experiences has been neglected for a long time but has been taken much more into account in the recent years (Barlow et al. Citation2012). It was found that negative contacts have a stronger effect on increasing prejudice than positive contacts do in decreasing it. It would thus be advisable to measure positive and negative contact, but also subjective perceived size as intervening variables (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2019). This is especially relevant, as there seems to be a large variation in what respondents have in mind when asked about migrants, foreigners, or foreign-born people. A recent study of Wasmer and Hochman (Citation2019) confirms that most people will not know the proportion of migrants living in their county nor can they evaluate the migrant status of a person based on outward appearance. As perceived outgroup size was not measured in this study, we could not derive the total effect of both influences on attitude toward foreigners.

We predicted that the rate of regional unemployment leads to an increasing hostile attitude toward migrants by raising the perception of threat. The underlying mechanism suggested by Meuleman et al. (Citation2020) considers this to be an indirect effect with the unemployment rate influencing individually perceived relative deprivation and through that increasing threat. This increased threat perception will then enlarge hostile feelings toward migrants (Meuleman et al. Citation2020). As these intervening variables were not measured in this study, indirect effects could not be considered.

Additionally, there have been mixed results about the relevance of temporal changes on the context level. According to a study by Kaufmann (Citation2017), sudden increases in unemployment rates or decreases in GDP severely alter the perception of threat. However, our robustness checks including χ²-tests showed that integrating changes within the last five or ten years in GDP per capita, proportions of migrants, or unemployment rates per county does not significantly alter results on xenophobia compared to the models that only use current levels. This is in line with similar findings by Teney (Citation2012) regarding changes in the proportion of immigrants and unemployment rates on election outcomes. A recent study by Coninck and Meuleman (Citation2023) also found no association between individual attitudes towards refugees and (changes in) outgroup size on a municipal level in Belgium, while proximity to the next asylum seekers center and a higher average taxable income of residents showed a positive connection. It would thus be useful in future studies to test and control neighborhood effects by multilevel models taking into account spatial attributes (Bivand et al. Citation2017).

Another issue arises when looking at the models through which outgroup size is implemented: various geographic units of analysis (e.g. neighborhoods, counties, regions, or countries) have been considered in the past and their differences have to be taken into account. Of the eight units analyzed in the aforementioned meta-analysis, the only strong positive and negative effects were found on the county and on the national level, whereas results for the other units were inconclusive. Other level 2 units should be considered in future studies, and it is necessary to find out specific conditions under which outgroup size takes effect.

The special status of Berlin during the division also poses a difficulty. Due to the nature of our data, we were unable to differentiate between East and West Berlin on the level 2 variables. As it seemed unreasonable to include it to the East or the West entirely, we thus decided to exclude all participants from Berlin (n = 122). A robustness check, calculating correlation patterns of all level 1 variables adjoining East Berlin to the East and West Berlin to the West only leads to small changes in correlations (<.10).

Conclusion

Despite these apparent limitations, some important conclusions can be drawn from our analyses. Overall, we found evidence for contact hypothesis, with a higher share of migrants in the district being associated with lower levels of individual xenophobia. Moreover, authoritarianism as an individual predisposition for prejudice formation should be considered when analyzing anti-foreign sentiment. Besides the direct effect of individual authoritarianism, it interacts with structural factors in that the effect of authoritarianism on xenophobia is especially strong in districts with a higher GDP per capita. While this is contrary to our original hypothesis, it may point towards an increasing relevance of a certain fear of social decline. Finally, we were able to show that differences between East and West Germany in xenophobic attitudes diminish when considering structural differences between the two regions. Reducing these structural differences and creating contact opportunities may thus help buffer anti-democratic and anti-modern ressentiments.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Statement of ethics

This study was performed in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Leipzig (Az: 132/18-ek; April 3rd, 2018).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.7 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Neither the research itself nor the study plan for this study were preregistered.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 EU 15-nationals are immigrants from the first 15 member countries of the EU who have joined until 1995 (Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom, Finland, Austria and Sweden). Weins (Citation2011) chose this differentiation because of increased prejudices against non-EU 15-nationals compared to other immigrant groups.

2 The exclusion of Berlin also had technical reasons: the level 2 variables were matched using county index numbers. As Berlin is considered a single county today, no correct (separate) allocation of level 2 variables to East and West Germany was possible. The county Berlin would end up with a double assignment, distorting the results of the multilevel analysis regarding the East/West level 1 variable.

3 As Primo, Jacobsmeier, and Milyo (Citation2007) suggested, we performed a robustness check, clustering standard errors in the multilevel analysis. In this model, the association between xenophobic attitudes and equivalent household lost significance.

4 As we included both the linear and the squared effect of the proportion of migrants into our calculations, we tested for multicollinearity (Aiken, West, and Reno Citation1991) using the variable inflation factors of the car package. Even though some VIF values exceeded the value 5, all of them stayed below the cut-off of 10 with the highest value being 7.10. The variables thus do not indicate high multicollinearity.

References

- Adorno, T. W., E. Frenkel-Brunswik, D. J. Levinson, and R. N. Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality: Studies in Prejudice. New York, NY, USA: Harpers & Brothers. Retrieved from http://www.ajcarchives.org/main.php?GroupingId=6490.

- Aiken, L. S., S. G. West, and R. R. Reno. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. London, UK: Sage.

- Akaike, H. 1973. “Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle.” In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory, edited by B. N. Petrov, and F. Csaki, 267–281. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado.

- Allport, G. W., K. Clark, and T. Pettigrew. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley.

- Altemeyer, B. 1998. “Advances in Experimental Social Psychology.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 30: 47–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60382-2.

- Asbrock, F., and I. Fritsche. 2013. “Authoritarian Reactions to Terrorist Threat: Who is Being Threatened, the Me or the We?” International Journal of Psychology 48 (1): 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.695075.

- Barlow, F. K., S. Paolini, A. Pedersen, M. J. Hornsey, H. R. Radke, J. Harwood, M. Rubin, and C. G. Sibley. 2012. “The Contact Caveat.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (12): 1629–1643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212457953.

- Bates, D., M. Mächler, B. Bolker, and S. Walker. 2015. “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4.” Journal of Statistical Software 67 (1): 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

- BBSR Bonn – Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development. 2020. Indikatoren und Karten zur Raum- und Stadtentwicklung – INKAR 2019. Data Licence Germany – attribution – Version 2.0.

- Beierlein, C., F. Asbrock, M. Kauff, and P. Schmidt. 2014. Die Kurzskala Autoritarismus (KSA-3): Ein ökonomisches Messinstrument zur Erfassung Dreier Subdimensionen Autoritärer Einstellungen. Mannheim, Germany: GESIS – Leibniz Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. Retrieved from https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-426711.

- Billig, M., and D. Cramer. 1990. “Authoritarianism and Demographic Variables as Predictors of Racial Attitudes in Britain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 16 (2): 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.1990.9976176.

- Bivand, R., Z. Sha, L. Osland, and I. Sandvig Thorsen. 2017. “A Comparison of Estimation Methods for Multilevel Models of Spatially Structured Data.” Spatial Statistics 21 (Part B): 440–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spasta.2017.01.002.

- Bizumic, B., and J. Duckitt. 2018. “Investigating Right Wing Authoritarianism with a Very Short Authoritarianism Scale.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 6 (1): 129–150. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v6i1.835.

- Blalock, Jr, H. M. 1967. “Status Inconsistency, Social Mobility, Status Integration and Structural Effects.” American Sociological Review 32 (5): 790–801. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092026.

- Blumer, H. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388607.

- BMI – Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat. 2021. Politisch motivierte Kriminalität im Jahr 2020. Bundesweite Fallzahlen. Retrieved from https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/2021/05/pmk-2020-bundesweite-fallzahlen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4.

- BMWi - Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie. 2020. Jahresbericht der Bundesregierung zum Stand der Deutschen Einheit. Berlin, Germany: BMWi.

- Borgonovi, F., and A. Pokropek. 2019. “Education and Attitudes Toward Migration in a Cross Country Perspective.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02224.

- Carnevale, A. P., N. Smith, L. Dražanová, A. Gulish, and K. P. Campbell. 2020. The Role of Education in Taming Authoritarian Attitudes. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Retrieved from https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/authoritarianism/.

- Coenders, M., and P. Scheepers. 2003. “The Effect of Education on Nationalism and Ethnic Exclusionism: An International Comparison.” Political Psychology 24 (2): 313–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00330.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cohrs, J. C., and F. Asbrock. 2009. “Right-wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation and Prejudice Against Threatening and Competitive Ethnic Groups.” European Journal of Social Psychology 39 (2): 270–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.545.

- Coninck, D., and B. de Meuleman. 2023. “Welcome in my Back Yard? Explaining Cross-Municipal Opposition to Refugees Through Outgroup Size, Outgroup Proximity, and Economic Conditions.” Migration Studies 11, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnac015.

- Decker, O., A. Hinz, N. Geißler, and E. Brähler. 2013. “Fragebogen zur Rechtsextremen Einstellung–Leipziger Form (FR-LF).” In Rechtsextremismus der Mitte. Eine Sozialpsychologische Gegenwartsdiagnose, edited by O. Decker, J. Kiess, and E. Brähler, 197–212. Gießen, Germany: Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Decker, O., J. Kiess, and E. Brähler. 2022. The Dynamics of Right-Wing Extremism Within German Society. Escape Into Authoritarianism. London, UK: Routledge.

- Destatis, W. Z. B. and BiB. 2021. Datenreport 2021. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik. Bonn, Germany: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

- Dunwoody, P. T., and D. L. Plane. 2019. “The Influence of Authoritarianism and Outgroup Threat on Political Affiliations and Support for Antidemocratic Policies.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 25 (3): 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000397.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. Chaiken. 1993. The Psychology of Attitudes. Fort Worth, US: Harcourt Brace.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2021. “Fundamental Rights Report 2021.” Retrieved from https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2021-fundamental-rights-report-2021_en.pdf.

- Frenkel-Brunswik, E. 1996. Studien zur Autoritären Persönlichkeit. Ausgewählte Schriften. Graz, Austria: Nausner & Nausner.

- GESIS – Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. 2019. “ALLBUS/GGSS 2018 (Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften/German General Social Survey 2018).” GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5270 Data file Version 2.0.0.

- Gorodzeisky, A., and M. Semyonov. 2019. “Unwelcome Immigrants: Sources of Opposition to Different Immigrant Groups among Europeans.” Frontiers in Sociology 4 (24), https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00024.

- Gorodzeisky, A., and M. Semyonov. 2020. “Perceptions and Misperceptions: Actual Size, Perceived Size and Opposition to Immigration in European Societies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 612–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550158.

- Heller, A., E. Brähler, and O. Decker. 2020a. “Rechtsextremismus - Ein Einheitliches Konstrukt? Ein Beitrag zur Frage der Operationalisierung Anhand des Fragebogens Rechtsextremismus–Leipziger Form (FR-LF).” In Prekärer Zusammenhalt. Die Bedrohung des Demokratischen Miteinanders in Deutschland, edited by A. Heller, O. Decker, and E. Brähler, 151–172. Gießen, Germany: Psychosozial-Verlag.

- Heller, A., O. Decker, V. Clemens, J. M. Fegert, S. Heiner, E. Brähler, and P. Schmidt. 2022. “Changes in Authoritarianism Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparisons of Latent Means Across East and West Germany, Gender, age, and Education.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 941466. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.941466.

- Heller, A., O. Decker, B. Schmalbach, M. Beutel, J. M. Fegert, E. Brähler, and M. Zenger. 2020b. “Detecting Authoritarianism Efficiently: Psychometric Properties of the Screening Instrument Authoritarianism – Ultra Short (A-US) in a German Representative Sample.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 533863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.533863.

- Hoxhaj, R., and C. V. Zuccotti. 2021. “The Complex Relationship Between Immigrants’ Concentration, Socioeconomic Environment and Attitudes Towards Immigrants in Europe.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (2): 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1730926.

- Janssen, H. J., M. van Ham, T. Kleinepier, and J. Nieuwenhuis. 2019. “A Micro-Scale Approach to Ethnic Minority Concentration in the Residential Environment and Voting for the Radical Right in the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 35 (4): 552–566. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz018.

- Kaufmann, E. 2017. “Levels or Changes?: Ethnic Context, Immigration and the UK Independence Party Vote.” Electoral Studies 48: 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2017.05.002.

- Kuznetsova, A., P. B. Brockhoff, and R. H. B. Christensen. 2017. “LmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 82 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

- Lengfeld, H., and C. Dilger. 2018. “Kulturelle und ökonomische Bedrohung. Eine Analyse der Ursachen der Parteiidentifikation mit der „Alternative für Deutschland“ mit dem Sozio-Oekonomischen Panel 2016.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 47 (3): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-1012.

- Lubbers, M., M. Gijsberts, and P. Scheepers. 2002. “Extreme Right-Wing Voting in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 41 (3): 345–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00015.

- Meloen, J. D., G. Van der Linden, and H. De Witte. 1996. “A Test of the Approaches of Adorno et al., Lederer and Altemeyer of Authoritarianism in Belgian Flanders: A Research Note.” Political Psychology 17 (4): 643–656. https://doi.org/10.2307/3792131.

- Meuleman, B., K. Abts, P. Schmidt, T. F. Pettigrew, and E. Davidov. 2020. “Economic Conditions, Group Relative Deprivation and Ethnic Threat Perceptions: A Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550157.

- Peresman, A., R. Carroll, and H. Bäck. 2023. “Authoritarianism and Immigration Attitudes in the UK.” Political Studies 71, https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211032438.

- Pettigrew, T. F., and L. R. Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

- Pituch, K. A., and J. P. Stevens. 2016. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Pollack, D. 2020. Das Unzufriedene Volk. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript-Verlag.

- Pottie-Sherman, Y., and R. Wilkes. 2017. “Does Size Really Matter? On the Relationship Between Immigrant Group Size and Anti-Immigrant Prejudice.” International Migration Review 51 (1): 218–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12191.

- Primo, D. M., M. L. Jacobsmeier, and J. Milyo. 2007. “Estimating the Impact of State Policies and Institutions with Mixed-Level Data.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 7 (4): 446–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/153244000700700405.

- Raudenbush, S. W., and A. S. Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Vol. 1). Newbury Park, CA, USA: Sage.

- Rippl, S., and K. Boehnke. 2016. “The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies.” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss142.

- RStudio Team. 2021. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. RStudio (Version 1.4.1106), PBC, Boston, MA. http://www.rstudio.com/ [Computer software].

- Ruffman, T., M. Wilson, J. D. Henry, A. Dawson, Y. Chen, N. Kladnitski, E. Myftari, J. Murray, J. Halberstadt, and J. A. Hunter. 2016. “Age Differences in Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Their Relation to Emotion Recognition.” Emotion 16 (2): 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000107.

- Schafer, J. L., and J. W. Graham. 2002. “Missing Data: Our View of the State of the art.” Psychological Methods 7 (2): 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

- Schlueter, E., and P. Scheepers. 2010. “The Relationship Between Outgroup Size and Anti-Outgroup Attitudes: A Theoretical Synthesis and Empirical Test of Group Threat- and Intergroup Contact Theory.” Social Science Research 39 (2): 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.07.006.

- Schlueter, E., and U. Wagner. 2008. “Regional Differences Matter.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49: 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020815207088910.

- Schmitt, M. T., N. R. Branscombe, T. Postmes, and A. Garcia. 2014. “The Consequences of Perceived Discrimination for Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Psychological Bulletin 140 (4): 921–948. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035754.

- Schwartz, L. K., and Joseph P. Simmons. 2001. “Contact Quality and Attitudes Toward the Elderly.” Educational Gerontology 27 (2): 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270151075525.

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, A. Yom Tov, and P. Schmidt. 2004. “Population Size, Perceived Threat, and Exclusion: A Multiple-Indicators Analysis of Attitudes Toward Foreigners in Germany.” Social Science Research 33 (4): 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.11.003.

- Steininger, M., and R. Rotte. 2009. “Crime, Unemployment, and Xenophobia?” Jahrbuch für Regionalwissenschaft 29 (1): 29–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-008-0032-0.

- Stephan, W. G., and C. W. Stephan. 2000. “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice.” In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, edited by S. Oskamp, 23–45. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Teney, C. 2012. “Space Matters. The Group Threat Hypothesis Revisited with Geographically Weighted Regression. The Case of the NPD 2009 Electoral Success.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 41 (3): 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2012-0304.

- Wagner, U., O. Christ, T. F. Pettigrew, J. Stellmacher, and C. Wolf. 2006. “Prejudice and Minority Proportion: Contact Instead of Threat Effects.” Social Psychology Quarterly 69 (4): 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250606900406.

- Waibel, H. 1996. Rechtsextremismus in der DDR bis 1989. Köln, Germany: PapyRossa-Verlag.

- Wasmer, M., and O. Hochman. 2019. “In Deutschland Lebende Ausländer: Unterschiede im Begriffsverständnis und Deren Konsequenzen für die Einstellungsmessung.” Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren 61: 18–23. https://doi.org/10.15464/isi.61.2019.18-23.

- Weber, H. 2015. “Mehr Zuwanderer, Mehr Fremdenangst? Ein Überblick über den Forschungsstand und ein Erklärungsversuch Aktueller Entwicklungen in Deutschland.” Berliner Journal für Soziologie 25 (4): 397–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-016-0300-8.

- Weins, C. 2011. “Gruppenbedrohung Oder Kontakt?” KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 63 (3): 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-011-0141-6.

- Zhou, S., E. Page-Gould, A. Aron, A. Moyer, and M. Hewstone. 2019. “The Extended Contact Hypothesis: A Meta-Analysis on 20 Years of Research.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 23 (2): 132–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318762647.

- Zick, A., C. Wolf, B. Küpper, E. Davidov, P. Schmidt, and W. Heitmeyer. 2008. “The Syndrome of Group-Focused Enmity: The Interrelation of Prejudices Tested with Multiple Cross-Sectional and Panel Data.” Journal of Social Issues 64 (2): 363–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00566.x.