ABSTRACT

Recent evidence suggests that in many European countries generally positive views about societal diversity predominate. Yet, as research has rather focussed on negative attitudes towards immigration and diversity, less is known about positive attitudes and those who hold them. The paper makes a conceptual and an empirical contribution to filling this gap. We introduce a multidimensional concept, “diversity assent”, to capture both evaluations of diversity and attitudes towards reflecting diversity in societal institutions. We test the concept using the case of urban Germany, drawing from a large, purpose-built survey. We demonstrate that, while assent differs for the two dimensions, a sizeable majority of those who evaluate diversity positively also agree with representing diversity in official policy and institutions, with some differences along socio-political lines.

Introduction

In recent decades, Germany has experienced successive migration movements, contributing to an ongoing socio-cultural diversification of society. Particularly in German city contexts, individuals from different socio-cultural backgrounds live together, and society is unmistakably diverse. A diversification of forms of life and the increasing visibility of sexual and gender minorities adds to this presence of socio-cultural diversity. In the political realm, leading representatives, from mayors to presidents, now embrace diversity as beneficial for the country (Schönwälder and Triadafilopoulos Citation2016). Yet, scepticism is widespread in public and scholarly discussions regarding the stability and substance of such pro-diversity declarations and policies. Against the background of electoral advances of extreme-right forces in past decades, fears are widespread that public opinion will turn against socio-cultural diversity and its public recognition. Given this threat and the importance of positions on immigration and diversity for the emergence of “a new structuring divide in European societies and politics” (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2021, 1), anti-immigration and anti-diversity attitudes have been a focus of recent scholarship.

Although of unquestionably great importance, this focus runs the risk of an imbalance. Several years ago, Newman et al. (Citation2015, 583–584) lamented an “asymmetry in the [immigration] opinion research” such that opposition, rather than “the factors that lead people to be supportive”, gain most academic interest. This may fuel a misperception that European publics more generally have turned against immigration. As Dennison and Geddes (Citation2019, 107) point out, contrary to common perceptions, this is not the case, and attitudes towards EU and non-EU migrants have remained “remarkably stable”, if not having become “gradually more positive […] during and since the ‘migration crisis’ of 2015”. Similarly, Ivarsflaten and Sniderman (Citation2022, 150) point out that more citizens are inclusive towards immigrant and religious minorities than often assumed. They call for a re-orientation of research towards “a new territory”, that is, “the beliefs, the concerns, the convictions of majority citizens who are open to a more inclusive society” (Citation2022, 146).

Yet, this new research territory is, by virtue of its novelty, rather under-specified. We do not know as yet how best to conceptualise such positive perspectives, nor do we sufficiently understand what motivates their supporters and what exactly they support – or not. This paper is a contribution to closing these gaps. It also responds to another imbalance: Previous scholarship has often focussed on what resident populations think about future immigration and the expectations of newcomers, but this is limiting when conceptualising positive attitudes to diversity. Diversity goes beyond recent immigration, and the former newcomers are part of a population that shapes the jointly inhabited society. We focus our attention on given and desirable features of a diverse society and on how the whole population, including immigrants and their descendants, respond to diversification. We introduce the concept of diversity assent, which is two dimensional, allowing researchers to distinguish between citizens’ judgements about diversity (evaluation assent) and positions on the political consequences of a diverse society (participation assent).

We apply the concept using unique survey data gathered in 2019–2020 in a random sample of German cities, the DivA-survey (Drouhot et al. Citation2021). To test the empirical worth of the concept, we investigate which social and political factors are associated with individuals supporting diversity using bivariate and multivariate analyses. Our results show the empirical utility of our multi-dimensional concept, as different factors drive support for the two dimensions differently. Furthermore, we demonstrate that diversity assent is widespread in Germany's urban population, although distinct for the two dimensions, corroborating other empirical studies into positive attitudes towards immigration and diversity, while adding differentiation.

Conceptualising diversity assent

Diversity assent and its conceptual neighbourhood

In this paper, our intention is to describe and better understand the attitudes of individuals who hold positive views of diversity in society. Socio-cultural diversity, and the ongoing diversification of societies has become a common experience in many European countries and beyond (Vertovec Citation2023). Yet when thinking about public opinion towards diversity, existing scholarship offers conceptual tools such as tolerance, (support for) multiculturalism and general attitudes to immigration or minority rights. In the following section, we distance ourselves from these concepts, and introduce diversity assent to think about positive attitudes towards diversity. Following other scholars’ work on related concepts (Hjerm et al. Citation2020 on tolerance; Knight and Brinton Citation2017 on gender), we understand the concept as multidimensional. This means that we do not just see more or less assent but aim to reflect that assent to diversity can take different forms. We distinguish, first, the evaluation of diversity as affecting society and individuals. We assume that individuals assess or evaluate how diversity affects their environment and people's lives and form an opinion on whether they perceive the existing diversity and its effects as positive, neutral or negative. We call this evaluation assent. Second, to capture assent to the consequences of socio-cultural diversity, such as the reflection of diversity in institutions and in the allocation of societal resources, we introduce participation assent.Footnote1 Individuals may or may not believe that the socio-demographic diversity of society should be reflected in its institutions, politics and public sphere, regardless of their general opinion of diversity. Thus, we argue for the theoretical distinction between the two dimensions.

We acknowledge that our understanding of diversity assent and its different forms shares some features with concepts and thoughts introduced in previous scholarship. Firstly, a number of scholars have used the term “tolerance” to capture attitudes towards individuals who one dislikes. Tolerance means “accepting the objectionable” (Rapp and Freitag Citation2015, 2; Forst Citation2001). Some studies move beyond mere acceptance of others, and stress that respect and appreciation for individuals should be seen as further aspects of tolerance. For example, Hjerm et al. (Citation2020, 899, 903) define tolerance as “a positive response to diversity itself” and a “value orientation towards difference”. Using the terms of a UNESCO definition, they propose “a three-dimensional concept, which includes acceptance of, respect for, and appreciation of difference”. Ivarsflaten and Sniderman (Citation2022) extend the concept towards the support for political consequences. Their terms “recognition” and “appraisal” respect express the difference between toleration of different concepts of life and, as appraisal, acceptance of a societal obligation to actively support or protect minority cultures. Nevertheless, these studies uphold an analytical focus of the majority accepting or protecting the existence of minorities, rather than a diverse society negotiating the terms of coexistence. Moreover, the term “tolerance” – although used differently by several authors – is commonly associated with putting up with something one dislikes. While we agree with the intention to distinguish different forms of relating to difference, we prefer to introduce a new term in order to stress the differences with older conceptualisations.

A second line of research which aims to identify views of desirable features of society and related policies refers to attitudes towards “multiculturalism” (Banting and Kymlicka Citation2006; Goodman and Alarian Citation2021; Verkuyten Citation2009). Berry’s (Citation2011, 2.3) definition of a “multicultural ideology” or “multicultural view” as implying “that cultural pluralism is a resource, and inclusiveness should be nurtured with supportive policies and programmes” addresses positions also captured in the extended definitions of “tolerance”. We share the intention to capture both general views and attitudes to policies (see Goodman and Alarian Citation2021). Still, the concept of multiculturalism is narrower than that of diversity in its focus on immigrant minorities,Footnote2 and we do not follow the group-focussed perception of participation and rights underlying it. By, instead, referring to diversity and diversity assent we allow for both individual and group-oriented conceptualisations of participation and rights.

Third, there is a huge body of literature on public opinion towards immigrants and immigration. Mostly, this literature is interested in questions such as which immigrant categories are deemed acceptable, what is expected of immigrants and how they should be treated (e.g. Heath et al. Citation2020). Another focus is on explaining what drives opposition to immigration. However, some of the policy-related questions investigated here relate to minority and immigrant rights in the country, that is, what we refer to as participation assent (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Wasmer and Koch Citation2003; Ziller and Berning Citation2021). Studies have also considered support for the rights of religious minorities, in particular Muslims (e.g. Carol, Helbling, and Michalowski Citation2015; Statham Citation2016) as well as solidarity with refugees (Drouhot, Schönwälder, and Petermann Citation2023). Scholarship on affirmative action in the United States also supports the conceptual distinction between more general views and views regarding political interventions. Explaining the discrepancy between Americans’ support for the principal of racial equality and their more sceptical views on specific policies to ensure this equality, has been a key concern in US-scholarship (Krysan Citation2000; Peterson Citation1994). These scholarships thus also offer some insights into how societies adapt to diversification.

In contrast to the literature on attitudes to immigrants, we refrain from conceiving of newcomers and citizens, and the latter granting rights to the former. Rather, we allow for the attitudes of all residents to be considered in our concept of diversity assent. Diversity assent is defined as a certain set of attitudes capturing (a) positive assessment of the socio-cultural heterogeneity of the social environment (evaluation assent) and (b) support for adjusting institutions and resource allocations in light of such heterogeneity (participation assent).

Who assents to diversity?

We apply our concept by asking which social and political factors are associated with support for diversity – along the two dimensions. The novelty of our conceptualisation calls for a partly descriptive and exploratory approach. Before beginning to empirically explore the extent and size of diversity assent in German cities, there are several expectations to be drawn from existing studies as to how the two forms of diversity assent relate to each other and concerning the major characteristics of those assenting to diversity in different forms before turning to an analysis of the main drivers of such assent.

How far should we expect evaluation assent and participation assent to align and correlate? By presenting a concept with multiple dimensions, rather than a scale, we join researchers from other fields, from immigration levels and policies (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2009) to gender (Knight and Brinton Citation2017). Individuals may believe that diversity is an asset for their society and for individuals – but not support any steps towards active minority or anti-discrimination policy, and vice versa. Indeed, some scholars suspect that pro-diversity pronouncements are limited to a preference for a vibrant and colourful city-life, but do not encompass a willingness to engage with others (Blokland and van Eijk Citation2010) or ensure more equality, and thus should be treated with caution. Some scholars suggest that the popular “drive for diversity” distracts from deep-seated inequalities and has rather “contained the struggle for racial equality” (Berrey Citation2015, 276). Our research will contribute to clarifying to what extent generally positive views of diversity and egalitarian commitments are indeed disconnected or rather related. Furthermore, theoretically, support for equal participation need not be based on positive views of the effects of diversity – but could be a matter of principle, based on egalitarian views. Respondents may support participation, but fear that diversity has negative effects. We know from studies of diversity discourses that “diversity” can have rather different meanings (e. g. Berrey Citation2015; Dobusch Citation2017).

The extent to which individuals assent in one, both, or neither of the diversity dimensions of course begs the underlying question of the motivation behind such assent. Given the limited evidence existing so far, clear hypotheses are difficult to generate, and we engage in a more exploratory fashion with a number of studies in similar fields. Firstly, the role of socio-economic background has been highly researched as a motivator for negative attitudes towards immigrants and out-group members. Traditionally, individuals from working class backgrounds, with lower income and education, were theorised to perceive “ethnic threat”, and thereby be more likely to support the exclusion of immigrants (Helbling Citation2014), and exhibit prejudice and intolerance (Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002). In recent years, however, other scholars illustrate the more nuanced effect of education on exclusionary attitudes (see Dražanová Citation2022; Rapp Citation2014). These nuances do not detract from the general finding in western Europe, that higher education level is rather consistently associated with support for cosmopolitanism (Maxwell Citation2020), lower concerns about immigration (Berg Citation2009) and support for the extension of immigrant rights (Wasmer and Koch Citation2003). We thus expect a positive relationship between education and support for both evaluation and participation assent. Yet, given that our participation dimension requires support for reducing privileges, it may be that those on higher incomes express lower support despite higher education level, due to lower support for general redistribution as shown in the political economy literature (Cavaille and Trump Citation2015). We thus intend to explore the relationship more closely between education and income.

Secondly, numerous studies have explored whether attitudes towards others are a function of everyday interactions. Intergroup contact has been shown to reduce prejudice and outgroup divide (Schönwälder and Triadafilopoulos Citation2016). We therefore assume that diversity assent is stronger among individuals with higher levels of intergroup contact, and we look as to whether different types of such contact, from neighbourhood interactions to friendships, impact assent in the two dimensions. Belonging to a minority – as well as female gender – has also been shown to affect attitudes to interventions favouring minorities (Crosby, Iver, and Sincharoen Citation2006, 596; Scarborough, Lambouths, and Holbrook Citation2019). It is plausible that members of a group identify with it, and possibly also with equally disadvantaged groups.

The third major group of variables we are interested in is political attitudes. Attitudes to societal diversity and to participation are likely correlated with broader beliefs about fairness, equality and plurality. Studies into affirmative action and intervention in favour of disadvantaged groups have illustrated that general political beliefs as well as beliefs about inequality and discrimination matter (Möhring and Teney Citation2020; Scarborough, Lambouths, and Holbrook Citation2019, 207). Nonetheless, the role of beliefs around redistribution and inequality is unclear, as some in the literature suggest that the popular “drive for diversity” distracts from deep-seated inequalities and has rather “contained the struggle for racial equality” (Berrey Citation2015, 276). Our research will contribute to clarifying to what extent generally positive views of diversity and egalitarian commitments are indeed disconnected or rather related. Furthermore, general political beliefs are expressed in sympathies for political parties, and we expect such sympathies to impact on diversity assent. As all major parties in Germany (except the extreme Right) express generally positive views of diversity, it remains to be seen how this is reflected in their supporters’ attitudes.

Data, operationalisation and methods

DataFootnote3

In this paper, we exploit a unique dataset on support for societal diversity among the general population in Germany – the DivA-survey (Drouhot et al. Citation2021). The survey instrument was designed to fill a specific gap: while much past social scientific research focuses on understanding determinants of hostility towards minority groups, there is a dearth of research and data on what motivates those who support a diverse society. Hence, this survey focuses on measuring the social experience and perception of diversity, as well as attitudes towards representing this diversity in political and public life, public expenditures, employment. The specific items and measurements we use are described in more detail below.

The survey was administered by telephone between November 2019 and April 2020 on a random sample of 2,917 respondents through a dual-frame strategy mixing landlines and mobile numbers (for a similar strategy see the German survey on voluntary engagement, Simonson et al. Citation2022). The sample was drawn in twenty randomly selected German cities.Footnote4 To test the fruitfulness of the concept, we focus on a population likely to have experienced diversity, namely, those living in cities, where immigrant shares are higher than elsewhere. Further, an urban sample is more likely to provide us with larger variation in attitudes, appropriate for the study of different dimensions of diversity assent.

Respondents include people of different migration background and citizenship. The response rate was 5.6 per cent – which is in line with rapidly declining response rates to telephone surveys in general (Berinsky Citation2017; Couper Citation2017; Keeter et al. Citation2017)Footnote5 In our analyses, we calibrate our estimates with design and post-stratification weights using rich data from the Mikrozensus, the major official annual household survey conducted by statistical offices in Germany. Specifically, we use the Mikrozensus to construct reference points on high-dimensionality cells for multiple sociodemographic variables of interest (municipality size, age, education level, and gender), adjust for over- or underrepresentation on these cells, and accordingly weigh results from our empirical analyses. Full technical details on the survey are available in a dedicated report (Drouhot et al. Citation2021). Weighted results are representative of adults living in German cities of at least 50,000 inhabitants.

Operationalisation of evaluation and participation assent

The DivA-survey includes a large battery of questions regarding evaluation of diversity, its experience and support for interventions. We use three questions each to approximate the latent dimensions evaluation and participation diversity assent. We use questions with the same answer categories for analytical ease as presented in . Evaluation assent refers to questions that ask the respondents to evaluate diversity broadly, whether it is an asset for society (enriching for the city, language plurality is a good thing) and individuals (young people benefit from contact). Here the emphasis is on how respondents judge the effects of diversification. In contrast, participation questions are about possible consequences and ask whether the diversity of society should be reflected in its institutions and the public space. The three items address the distribution of public resources (public funding for minority cultures), political representation (diverse parliaments) and public presence of minorities (mosque building). To check the empirical relationship between these items, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. We can confirm, albeit with some level of covariation between the two factors, that the questions do load onto two separate factors with satisfactory measurement fit statistics. See appendix A1 for the full CFA table. We deliberately included the more contested issues of language and Islam to arrive at a realistic evaluation of diversity assent.

Table 1. Survey questions used for evaluation and participation assent.

Who are those assenting to diversity in one or both dimensions, and which issues bring them together or drive them apart? In the empirical analysis, we follow a set of coding rules, shown in , to allocate individuals into different diversity-assent groups for evaluation and participation assent respectively. These groups are “assenting”, “non-committing” and “dissenting”. We apply a relatively strict threshold to allocate an individual into the “assenting” group: They must somewhat or strongly agree to two or more of the evaluation questions to join the “evaluation assenting” group, and the same to join the “participation assenting” group. Given that negative answers are few and that respondents may be reluctant to openly oppose diversity, we create an even stricter criterion to belong to the “dissenting” group: any negative answer given leads to membership of this group. The remainder of the respondents is “non-committing”.

Table 2. Criteria for forming assenting and dissenting groups.

In the following empirical analysis, we proceed in three main parts. First, we investigate the distribution of evaluation and participation assent and the overlap of these dimensions in the urban German population. Second, we analyse the characteristics of the group of “assenters” (those holding one or both forms of assent) using descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis. Third, we use multinomial regression models to investigate which characteristics are associated with either just supporting evaluation assent or, rather, supporting both evaluation and participation assent.

Analysis: exploring diversity assent and the assenting

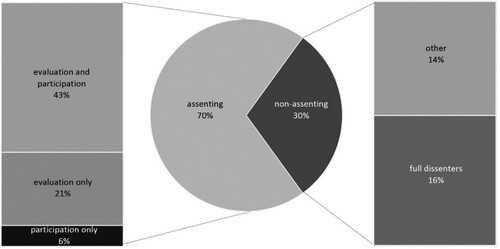

We first show the distribution of answers to our individual six items () and then proceed in the manner explained above. Firstly, we observe that the majority of questions received mostly “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” answers: For the evaluation questions, this is 78 per cent for “benefit contact”, 74 per cent for “enriching city” and 48 per cent for “language diversity” – the lowest supported question of the six items. There are lower levels of overall assent for the participation questions, but agreement remains between 63 per cent for “diverse parliaments”, 58 per cent for “funding culture”, and 50 per cent for “build mosques”.

Figure 1. Distribution of answers to the diversity assent items. Note: N = 2800, missings (don’t know or refuse to answer) per question shown in table A2B in the online appendix. Weights are applied.

Secondly, there are two questions with reduced support – namely “language plurality” and “build mosques”, the latter with the highest share of opponents with 26 per cent choosing strongly or somewhat disagree. Clearly, both language and Islam are contested issues in Germany. It is plausible that limited appreciation of linguistic plurality reflects the long-term emphasis on the importance of German language competencies for immigrant integration in dominant politics and the public debate (Elrick and Winter Citation2018). Limited (though majority) assent to a right to build mosques suggests that scepticism towards the public presence of Islam is widespread (Carol, Helbling, and Michalowski Citation2015).

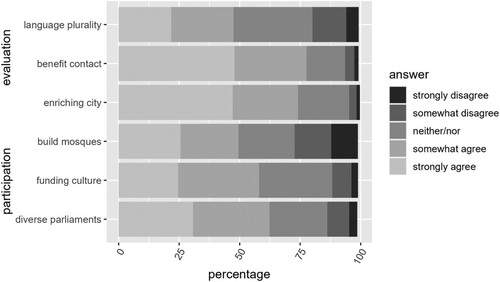

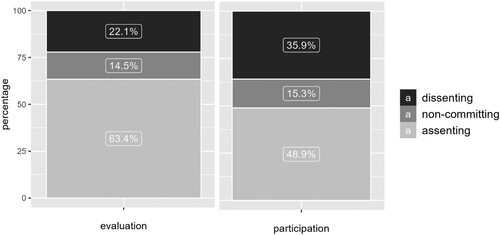

We now present the distribution of evaluation and participation diversity assenters into assenters, non-committed and dissenters (see ), following the aggregation scheme shown in . Evaluation diversity assenters, that is, individuals who broadly believe that socio-cultural diversity is an asset for society and individuals within it, comprise almost two-thirds of our sample (63 per cent). About one-fifth of the sample are evaluation dissenters, and the smallest group of all do not state a clear view, the non-committed (15 per cent). Not committing to an opinion can be an expression of insecurity or unwillingness to disclose an opinion. As a result of our stricter threshold we show a lower level of pro-diversity views than analyses based on single questions in other German surveys (GESIS Citation2017; Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2017, 23).Footnote6 Regarding participation assent – that is, the notion that societal institutions and the distribution of resources should take the diversity of society into account – there are fewer respondents (49 per cent) in the assenting group, and 14 more (36 per cent) are in the dissenting group compared to evaluation assent. Unsurprisingly, issues of participation are more controversial than the evaluation of diversity. Interestingly, only one-third of the “non-committing” group for evaluation assent remain “non-committing” for participation, implying that although some individuals are in the middle of the fence, this is not always consistent.Footnote7

Figure 2. Evaluation and participation assent and dissent among survey respondents. Note: N = 2893. Weights are applied.

In order to understand better how the two dimensions of diversity assent relate to each other, we construct groups of evaluation and participation assenters and find that both overlap to a great extent: About two-thirds of those who evaluate diversity positively also agree with representing diversity in societal institutions (henceforth evaluation and participation assenters), making up 43 per cent of the whole sample. A smaller group (21 per cent) of the sample evaluate diversity positively, but do not assent to the participation dimension (evaluation only). These numbers demonstrate that in the most part, support for diversity is far from superficial. Rather, the 43 per cent figure for evaluation and participation assent shows that those with positive evaluations of diversity mostly appreciate that society must adapt and acknowledge diversity. Of the 21 per cent of our sample who only express evaluation assent, 53 per cent of their negative answers are for the building mosques item.Footnote8 A small share of 6 per cent support participation assent, but do not fulfil our criteria for evaluation assent. presents two connected pie charts of those individuals falling into one of the “assenting” groups (only evaluation, only participation or both evaluation and participation), or one of the “non-assenting” groups (“full dissenters”, who are against both forms of assent, or “other” respondents).

Taken together, those who assent to evaluation or participation, or both, account for 70 per cent of our sample. The remaining 30 per cent are non-assenters of which 16 per cent are full dissenters (to both evaluation and participation) and 14 per cent are “others” with combinations of dissent, don't know or no answers.

Who assents to diversity?

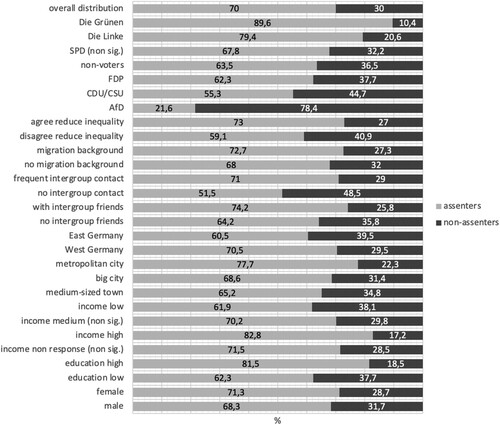

We now proceed to analyse how specific social and political groupings are represented in the 70 per cent “assenters” group shown in . We first present descriptive results. We measure the variables of interest as follows: We calculate household income and adjust it to take number of children and other dependents into account, and divide respondents into four income groups (here as: low, medium, high and non-respondents). Education level is measured as a dummy variable, between those with upper-secondary education versus the rest (Dražanová Citation2022; Rapp Citation2014). To capture general political party sympathies, we use a standard question on voting intention. To measure support for egalitarianism and reducing inequality, we include an item which asks for support for interventions to reduce social inequality. Given extensive research on contact and interaction between in and out-groups (Schönwälder and Triadafilopoulos Citation2016), we include variables on whether a person has a migration background, on intergroup interaction between non-immigrants and those with a migration background (neighbourhood contact and friendship). Residence in larger cities (Maxwell Citation2020) may also be associated with more intense diversity experiences, we thus distinguish three groups of cities (medium, large, metropolitan). To capture potential divisions between former East and West Germany (Berning et al. Citation2022), we also include a dummy-control variable. A full list of variables and measurement decisions can be found in online appendix table A2a.

To best illustrate how assent and non-assent are represented among individuals with different characteristics and political attitudes, we report percentages of assent for each grouping. This should be read relative to the 70 per cent assenters in the whole sample, that is, the urban German population overall. We employed chi2 independence tests for all associations. Given that most associations are statistically significant at the 5 per cent significance level, we only explicitly report on significance for the few insignificant results in this section ().

Figure 4. Frequency of assenters and non-assenters across different groups. Note: Missings for each variable are reported in table A2a in the online appendix, weights are applied.

It should first be said that in all groupings tested but one (AfD supporters), the assenters are in the majority, suggesting that diversity assent does not sharply divide the population along various social and political criteria. The descriptive statistics illustrate which groups are more or less likely to assent. Social and political factors are strongly associated with assenting: The assenters appear to be over-represented in groups of left-wing voters (90 per cent of supporters of Die Grüne, 79 per cent of Die Linke), and under-represented in right-wing party supporters. Beyond the left-right divide, those with high education and egalitarian ideology are also more likely to be assenters.

Whilst the literature would suggest otherwise (Street and Schönwälder Citation2021), an individuals’ migration background only shapes their diversity assent marginally: While people with migration background assent to 73 per cent, people without a migration background do so by 68 per cent. However, those who have interactions with individuals with different backgrounds are pronouncedly in the assenting group. For example, people with at least one close intergroupFootnote9 friend are 74 per cent assenting, while people without such a friend are only to 64 per cent assenting. The picture is even more pronounced for general-intergroup contact in the neighbourhood. Respondents without such encounters assent are significantly underrepresented at 52 per cent assent. Intergroup contact is thus clearly associated with diversity assent but in a non-linear way: the divide is between no contact and at least some contact, and not between lower and higher frequency of contact.

Finally, socio-demographic factors are also associated with assenting to diversity, as one would expect, more individuals from metropolitan cities and from Western Germany assent compared to smaller cities and those living in former East Germany.

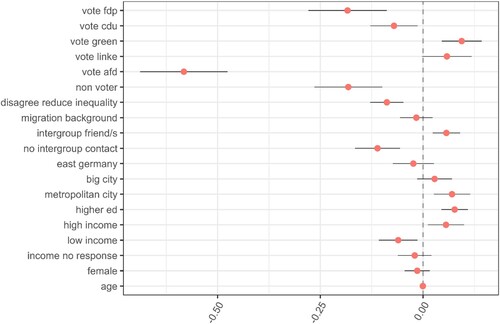

To assess which of these variables are directly associated with assent, rather than confounded by other variables, we now estimate a regression model to distinguish assenters from non-assenters. Due to the binary outcome of the dependent variable, we employed a logistic regression. shows the coefficients of all independent variables included in the model, with the full table shown in the appendix table A3.

Figure 5. Results of logistic regression, assenters vs non-assenters. Note. N = 2723. Plotted are average marginal effects calculated from logistic regression shown in online appendix table A3. Ref. categories for categorical variable, voting (SPD), cities (large town), income (low income).

Most bivariate associations of factors of diversity assent remain stable in the regression model in terms of direction, strength and significance. Of note is that socio-economic status, measured by income and education level in these models, remains a strong predictor of diversity assent. This follows expectations in parts of the literature which suggest that education predicts openness to immigration attitudes (Harris Citation2022). The effects of intergroup contact and friendship also matter and are significantly related to belonging to the “assenting” group, as suggested in these bivariate analyses.

Four remarkable results are different in the regression to the descriptive statistics. First, FDP-sympathisers are significantly less likely diversity assenters than SPD-sympathisers, our comparison group here. Moreover, the coefficient even exceeds the negative coefficient of CDU/CSU voters, meaning that FDP supporters tend to be even less likely assenters than CDU/CSU supporters. Second, the coefficient of migration background is negative but close to zero and non-significant. Migration background is not relevant for diversity assent; the significant positive bivariate association seems to be a spurious correlation. Third, the coefficient of living in a “big city” (the middle category city in terms of size) is not significant. As medium-sized towns are the reference group in the regression model, this means that medium-sized towns and big cities do not differ in the level of diversity assent. There is still a difference between metropolitan cities (500,000+) – with higher levels of diversity assent – on the one hand and medium-sized towns and big cities on the other. Fourth, the negative bivariate association between living in East Germany and diversity assent appears to have been spurious, and in the full model appears to be explained by other covariates – such as party sympathy or other political opinions, as the plot would suggest.

Divisions within the assenting group

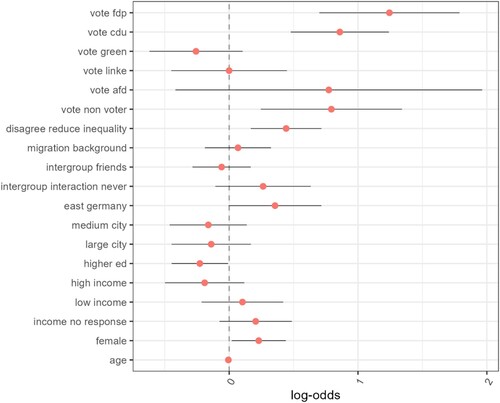

Whilst useful for assessing the differences between all assenters and non-assenters in society, the previous analysis still leaves many questions unanswered regarding the different levels of assent to diversity: In the following section, we monopolise on the two dimensions of assent, and investigate which individuals solely evaluate diversity positively (evaluation only, 21 per cent of the whole sample), and which individuals additionally assent to institutional consequences (evaluation and participation assent, 43 per cent of the whole sample). This analysis enables a better understanding of the factors that determine the difference between evaluation and participation assent. Similar to above, we first conducted descriptive analyses, followed by a regression analysis. For the sake of parsimony, we only report the results of the regression here, and the full table of chi-squared analysis can be found in appendix table A4.

Differently to the previous section, we use multinomial logistic regression models, because we are interested in investigating the difference between two groups, in relation to the broader sample. Our outcome is categorical, namely, whether an individual is in the “evaluation only”, “evaluation and participation”, “other”, or “full dissenting” group. We then run a regression model using “evaluation and participation assent” as the baseline outcome and generate a series of coefficients for each of the remaining outcomes. These can be read as, holding all else constant, how a one-unit increase (for categorical or dummy variables, moving from 0 to 1) in the variable in question affects the log-odds of being in one of the assent/dissent groups, compared to the “evaluation and participation” group. The full model can be found in appendix table A5. Here, we present a dot-whisker plot for the part of the model which only compares the “evaluation only” with the “evaluation and participation assent” respondents. The coefficients in thus reflect the log-odds of belonging to the “evaluation only” group.

Figure 6. Results of multinomial regression model, “evaluation only” assenters. Note: N = 2723. Plotted are log-odds for belonging to the groups “evaluation only” assenters in comparison with evaluation and participation assenters, calculated from model 1 in table A5.

The multivariate analysis shown here illustrates that belonging to the evaluation only group is strongly associated with political factors and less so with socio-demographic and socio-economic ones. Supporting the liberal FDP or conservative CDU/CSU, and not intending to vote, increases the log-odds of belonging to the evaluation only group whereas, interestingly, supporting the Greens and The Left does not account for differences between these two groups of diversity assenters. This is notable compared to the strong effect of voting-intentions for these parties in the previous analysis – they explain assent to diversity overall, but the association is not significant in understanding differences between those who solely evaluate positively and those who also assent to institutional consequences.

Furthermore, non-supporters of egalitarian demands are significantly more likely to be in the evaluation only group. This implies that, as one may expect, pro-egalitarian views are aligned with support for reflecting different groups in a diverse society in its institutions and public space. Combined with the significant effect of sympathy for the FDP and CDU/CSU, this finding suggests that right-wing socio-economic preferences seem to be aligned with not displaying participation assent – in spite of a generally positive view of diversity among those groups as shown in the bivariate analyses.

Almost all differences relating to social, demographic and spatial factors are insignificant in the multivariate analysis. Lower-education level and living in East Germany are associated with belonging to the “evaluation only” group rather than the evaluation and participation assent group, albeit the education variable is only just within conventional significance. Most social and political factors tested here are merely associated with differences in the first analysis and not the second, implying that such factors are relevant for the difference between diversity assenters and non-assenters, but not for the difference between more or less consequent assenters. As may be expected, participation assent is less widespread than evaluation assent, and therefore a broader group of individuals are hesitant to assent to political consequences that reflect socio-cultural diversity.

Discussion and conclusion

This article aimed to do two things: First, we introduced a concept suitable for assessing the extent to which populations agree with the sociocultural diversity in their social environments. We suggest that it complements the existing literature, such that it provides a means to focus on residents’ views of the diverse societies they inhabit. Further, while existing knowledge is balanced towards hostility to diversity and immigration, by highlighting those who accept diversity and are willing to accommodate it, we contribute to a more balanced view of social realities. We follow previous research calling for multidimensional concepts (Hjerm et al. Citation2020; Knight and Brinton Citation2017). Our theory-driven bi-dimensional concept, diversity assent, addresses evaluations of the effect of such diversity on society and individuals, on the one hand, and the willingness to support an adjustment of societal institutions and resource allocations to diversity, on the other. By introducing these two dimensions, we do not rule out extending it to further dimensions, for example, assent to specific interventions explicitly addressing discrimination against certain groups, or active engagement.

In the second half of the paper, we provided an empirical analysis of diversity assent for residents of German cities. Our results confirm that it makes sense to distinguish different dimensions of diversity assent, here conceptualised as evaluation and participation assent. For one, these two dimensions attract different levels of assent: While almost two-thirds of the urban population evaluate diversity positively, assent to drawing political consequences is lower and remains just under 50 per cent. Our finding that participation assent enjoys lower levels of support parallels those of research in multiculturalism and affirmative action policies (see Krysan Citation2000; Kymlicka Citation2022; Peterson Citation1994; Yogeeswaran and Dasgupta Citation2014) that finding support for intervening to ensure more equal access and participation may prove harder than finding general support for diversity or fairness. The character of this discrepancy remains disputed and further research should aim to provide deeper insights. Is it, for instance, merely a difference between responses to more general and more specific suggestions, a difference driven by the influence of competing values or fundamental beliefs, or rather related to affect (Krysan Citation2000, 148–149)?

Nevertheless, our findings imply that diversity assent is rather widespread. Diversity assent does not sharply divide the population along social and political lines. While social and political factors are associated with the difference between assent and non-assent, we find both assenters to diversity as well as dissenting and sceptical individuals among the supporters of all major political parties, and across educational and income groups. However, individual measures for parliamentary diversity and funding minority cultures do find majority support, and most of those who in principle see diversity as beneficial (evaluation assent) also take a step further and agree with its representation in public policy and public life (participation assent). For those who do not, although agreeing that diversity is beneficial for society, the public presence of Islam is a major, although not the only, hurdle. A considerable body of research has examined such resistance to the presence of Muslims (e.g. Ivarsflaten and Sniderman Citation2022), but more research is desirable to deepen our understanding of the complexities of diversity assent.

Another main finding of our study is that whereas social factors (education, income, intergroup contact) are associated with the difference between assent and non-assent, the variation within the assenting group is mainly related to political factors alone such as party sympathy and views on inequality. This is consistent with prior evidence for related concepts (immigration, Harris Citation2022). Regarding the difference between evaluation only and evaluation and participation assenters, it is mainstream right sympathisers – FDP and CDU/CSU – who tend to refrain from participation assent. Views on the reduction of social inequality are clearly associated with both diversity assent altogether and participation assent in particular, suggesting that – for a sizeable part of our population – more social equality and more diverse political representation are seen as parts of broader egalitarian policies. This is an important observation as often demands for social equality and for reflecting diversity are portrayed as competing political aims.

Notably, education, although significant for understanding the difference between assenters and non-assenters, remains only marginally significant for explaining differences within the diversity assenters. The inconsistent effect of education echoes prior studies on tolerance (Rapp Citation2014, 153) and attitudes towards affirmative action (Crosby, Iver, and Sincharoen Citation2006). Although traditionally education is seen as broadening perspectives and increasing sympathy to out-groups, our findings suggest exercising caution when using education to explain attitudes towards more demanding elements of diversity assent.

These different effects of social, demographic and political factors reiterate the importance of a multi-dimensional understanding of diversity assent: More analytical gains can be made, compared to considering assent as a linear spectrum from “less” to “more”. It is telling that individuals rejecting some element of participation assent are more heterogenous; high-earning and highly-educated supporters of Liberal and Conservative parties, for example. Future research should untangle these unexpected positions towards different responses to diversity.

Somewhat surprisingly, factors we interpret as diversity experiences, such as engaging with people of a different migration background as well as living in a bigger city, seem irrelevant for understanding the differences within the groups of assenters, while they are related to the difference between assenters and non-assenters. More intergroup interaction does not seem to increase the willingness to support policies and institutions that reflect social diversity, but does contribute to a positive assessment of diversity.

Further, our results defy a common assumption in existing research (Crosby, Iver, and Sincharoen Citation2006, 596; Scarborough, Lambouths, and Holbrook Citation2019, 206) that the potential beneficiaries of measures support them to a higher extent than the previously advantaged. Both women as well as immigrants and their descendants could be seen as benefitting from more diversity in parliaments, the latter from acceptance of linguistic plurality or funding for minority cultures. Gender does not come out as very influential in our study. Even more surprisingly, migration background makes very little difference to either analysis, although at a descriptive level among those with own or familiar migration experience support for a positive evaluation of diversity is slightly higher (2.7 per cent) than in the general population. This may be due to the composition of our sample, such that those with migrant background are skewed towards those born in Germany and those with German citizenship. The overwhelming majority are Christians (54 per cent) or not religious (33 per cent) and only very few are Muslims (5 per cent). Other research has already indicated that within the immigrant population attitudes to pro-equality measures differ (e.g. Street and Schönwälder Citation2021), although we may not, as yet, fully understand what drives this.

Two limitations should be noted: First, the survey questions used in this analysis partly refer to diversity in general, without offering further specification, and partly include references to origin, minorities, and religion or Islam, that is, references to immigration-related diversity. Thus, whereas we expect to have captured assent to immigration-related diversity more specifically, it is possible that bias emerged where respondents were also thinking of other groups. It would be desirable to investigate assent to diversity in a broader sense, but given the limitations due to survey length, in the design of this survey, priority was given to in-depth investigation rather than a broader thematic scope.

Second, our study is representative for the population of German cities with at least 50,000 inhabitants. Other surveys suggest that levels of diversity assent may be lower in small towns and rural areas (Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2017; GESIS Citation2017). At the same time, we see no reason to assume that the concept is less useful for the analysis of such contexts or that associations with political and social factors would be different. Still, it would be desirable to investigate more broadly in future research, and to carry out nationally comparative studies.

Overall, the paper offers a framework for future research on attitudes towards socio-cultural diversity. It presents a theoretically-driven conceptualisation of a phenomenon distinct from attitudes to immigration and tolerance. Further, by applying the concept to the urban German population, we have demonstrated how positive evaluations of societal diversity and support for representing such diversity in institutions and resource allocations are distinct.

Note on ethics considerations

The DivA survey was conducted by a professional company, Kantar. Practices of such companies are subject to regulations in the Bundesdatenschutzgesetz (Federal Law on Data Protection), ensuring strict anonymisation. We only received an anonymised dataset. Detailed written information on the survey and data protection was made available to (potential) respondents. In developing the questionnaire, great care was taken to avoid any unethical content and of course in any way abusive or discriminatory language. A formal ethics review was at the time not available at our institution. However, the Max Planck Society has rigid regulations on research ethics and data protection, binding for all its researchers (https://www.mpg.de/199426/forschungsfreiheitrisiken.pdf).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (237 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Lucas Drouhot for his conceptual and empirical contribution to the creation of the DivA dataset; our research assistants Zeynep Bozkurt, Tanita Engel and Carolina Reiners for their contribution to the paper and research collection. Detailed feedback was much appreciated from Margherita Cusmano, James Dennison and Lenka Dražanová. Comments and questions from the MPI-MMG SCD colloquium (2022), Migration Policy Conference at the EUI (2022) and IMISCOE general conference (Oslo, 2022). All mistakes and omissions are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The DivA dataset is currently in the GESIS online repository, and will be released from an embargo period on 31.12.2024. For access or other enquiries, please contact Karen Schönwälder at schönwä[email protected]

Notes

1 Participation assent does not only refer to changes, but could also reflect the status quo in a society, should respondents feel that diversity is already well reflected in institutions.

2 We acknowledge that in Canada the term is now used in a wider sense, resembling the meaning of “diversity”, see Banting Citation2014.

3 Some sentences in this section also appear in Drouhot, Schönwälder, and Petermann Citation2023 as they describe the same data set.

4 Stratified sampling to include East and West, and cities of different size. We sampled in cities of 50,000 or more inhabitants. 41% of the German population live in cities of that size.

5 Research based in the United States, where issues of nonresponse in telephone surveys have appeared earlier than in Europe, has shown that low response rates need not be conflated with response quality or nonresponse bias (Keeter et al. Citation2017), particularly if high quality auxiliary data are available for post-survey calibration (e.g. Groves 2006; Koch and Blohm Citation2016) – which is our case here.

6 In the ALLBUS 2016 (GESIS Citation2017), 74% agree to the statement “A society with a high degree of cultural diversity is more capable of tackling new problems”. In the Vielfaltsmonitor 2017 the question “How do you feel about cultural diversity in Germany?” received 72% positive answers (Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2017).

7 Of these participation “non-committed”, 38% were “non-committed”, 13% were “dissenting” and 48% were assenting in the evaluation questions. This suggests that many non-committed for participation assent, do rather evaluate diversity positively. Conversely, we see that 44% of the evaluation “non-committed” were dissenters in the participation stage. The overlapping group of non-committed only totals around 5% of the whole sample.

8 At 23% of answers, opposition to diversity in parliaments is also noticeable. 14% of negative answers were given to the question of funding for minority cultures.

9 Defined as people without a migration background have at least one friend with a migration background or people with a migration background have at least one friend without a migration background.

10 Those individuals answering more than one question with “don't know” or refuse to answer are removed from the analysis. This totals five individuals.

References

- Banting, K. 2014. “Transatlantic Convergence? The Archaeology of Immigrant Integration in Canada and Europe.” International Journal 69 (1): 66–84.

- Banting, K., and W. Kymlicka. 2006. Multiculturalism and the Welfare State. Recognition and Redistribution in Contemporary Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berg, J. A. 2009. “Core Networks and Whites’ Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration Policy.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73 (1): 7–31.

- Berinsky, A. J. 2017. “Measuring Public Opinion with Surveys.” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (1): 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-101513-113724

- Berning, C. C., C. Ziller, et al. 2022. “Verbreitung und Entwicklung rechtsextremer Einstellungen in Ost- und Westdeutschland.” In Wahlen und politische Einstellungen in Ost- und Westdeutschland, edited by M. Elff, 307–338. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Berrey, E. 2015. The Enigma of Diversity: The Language of Race and the Limits of Racial Justice. University of Chicago Press.

- Berry, J. W. 2011. “Integration and Multiculturalism: Ways Towards Social Solidarity.” Papers on Social Representations 20: 2.1–2.21.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2017. Willkommenskultur im “Stresstest”: Einstellungen in der Bevölkerung 2017 und Entwicklungen und Trends seit 2011/2012. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Blokland, T., and G. van Eijk. 2010. “Do People Who Like Diversity Practice Diversity in Neighbourhood Life? Neighbourhood Use and the Social Networks of ‘Diversity-Seekers’ in a Mixed Neighbourhood in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (2): 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830903387436

- Carol, S., M. Helbling, and I. Michalowski. 2015. “A Struggle Over Religious Rights? How Muslim Immigrants and Christian Natives View the Accommodation of Religion in Six European Countries.” Social Forces 94 (2): 647–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov054

- Cavaillé, C., and K. S. Trump. 2015. “The Two Facets of Social Policy Preferences.” The Journal of Politics 77 (1): 146–160.

- Couper, M. P. 2017. “New Developments in Survey Data Collection.” Annual Review of Sociology 43 (1): 121–145. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053613

- Crosby, F. J., A. Iver, and S. Sincharoen. 2006. “Understanding Affirmative Action.” Annual Review of Psychology 57 (1): 585–611. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190029

- Dennison, J., and A. Geddes. 2019. “A Rising Tide? The Salience of Immigration and the Rise of Anti-Immigration Political Parties in Western Europe.” The Political Quarterly 90 (1): 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12620

- Dobusch, L. 2017. “Diversity Discourses and the Articulation of Discrimination: The Case of Public Organizations.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (10): 1644–1661. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1293590

- Dražanová, L. 2022. “Sometimes it is the Little Things: A Meta-Analysis of Individual and Contextual Determinants of Attitudes Toward Immigration (2009–2019).” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 87: 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.01.008

- Drouhot, L., S. Petermann, K. Schönwälder, and S. Vertovec. 2021. The “Diversity Assent” (DivA) Survey – Technical Report. Working Papers WP 21-20. Göttingen: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.

- Drouhot, L. G., K. Schönwälder, S. Petermann, et al. 2023. “Who Supports Refugees?” Diversity Assent and pro-Refugee Engagement in Germany. CMS 11 (2023): 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-023-00327-2.

- Elrick, J., and E. Winter. 2018. “Managing the National Status Group: Immigration Policy in Germany.” International Migration 56 (4): 19–32.

- Forst, R. 2001. “Tolerance as a Virtue of Justice.” Philosophical Explorations 4 (3): 193–206.

- GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. 2017. Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften ALLBUS 2016. GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln. ZA5250 Datenfile Version 2.1.0.

- Goodman, S. W., and H. M. Alarian. 2021. “National Belonging and Public Support for Multiculturalism.” The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 6 (2): 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.52

- Gorodzeisky, A., and M. Semyonov. 2009. “Terms of Exclusion: Public Views Towards Admission and Allocation of Rights to Immigrants in European Countries.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (3): 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870802245851

- Harris, E. 2022. “Educational Divides and Class Coalitions: How Mainstream Party Voters Divide and Unite Over Immigration Issues.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (Online first).

- Heath, A., E. Davidov, R. Ford, E. Green, A. Ramos, and P. Schmidt. 2020. “Contested Terrain: Explaining Divergent Patterns of Public Opinion Towards Immigration Within Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1550145

- Helbling, M. 2014. “Opposing Muslims and the Muslim Headscarf in Western Europe.” European Sociological Review 30 (2): 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct038

- Hjerm, M., M. A. Eger, A. Bohman, and F. Fors Connolly. 2020. “A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference.” Social Indicators Research 147 (3): 897–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02176-y

- Hutter, S., and H. Kriesi. 2021. “Politicising Immigration in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 1–25.

- Ivarsflaten, E., and P. M. Sniderman. 2022. The Struggle for Inclusion: Muslim Minorities and the Democratic Ethos. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Keeter, S., N. Hatley, C. Kennedy, and A. Lau. 2017. What Low Response Rates Mean for Telephone Surveys. Technical Report. Washington D.C.: Pew Research Center.

- Knight, C. R., and M. C. Brinton. 2017. “One Egalitarianism or Several? Two Decades of Gender-role Attitude Change in Europe.” American Journal of Sociology 122 (5): 1485–1532.

- Koch, A., and M. Blohm. 2016. Nonresponse Bias. GESIS Survey Guidelines. Mannheim: GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

- Krysan, M. 2000. “Prejudice, Politics, and Public Opinion: Understanding the Sources of Racial Policy Attitudes.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.135

- Kymlicka, Will. 2022. “Multiculturalism as Citizenization: Past and Future.” In Assessing Multiculturalism in Global Comparative Perspective, edited by Yasmeen Abu-Laban, Alain-G Gagnon, and Arjun Tremblay, 21–40. Oxford: Routledge.

- Maxwell, R. 2020. “Geographic Divides and Cosmopolitanism: Evidence from Switzerland.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (13): 2061–2090.

- Möhring, K., and C. Teney. 2020. “Equality Prescribed? Contextual Determinants of Citizens´ Support for Gender Boardroom Quotas Across Europe.” Comparative European Politics 18 (4): 560–589. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00199-w

- Newman, B. J., T. K. Hartman, P. L. Lown, and S. Feldman. 2015. “Easing the Heavy Hand: Humanitarian Concern, Empathy, and Opinion on Immigration.” British Journal of Political Science 45 (3): 583–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000410

- Peterson, R. S. 1994. “The Role of Values in Predicting Fairness Judgments and Support of Affirmative Action.” Journal of Social Issues 50 (4): 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01199.x

- Rapp, C. 2014. Toleranz gegenüber Immigranten in der Schweiz und in Europa. Wiesbaden: Springer Verlag.

- Rapp, C., and M. Freitag. 2015. “Teaching Tolerance? Associational Diversity and Tolerance Formation.” Political Studies 63 (5): 1031–1051.

- Scarborough, W. J., D. L. Lambouths, and A. L. Holbrook. 2019. “Support of Workplace Diversity Policies: The Role of Race, Gender, and Beliefs About Inequality.” Social Science Research 79: 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.01.002

- Scheepers, P., M. Gijsberts, and M. Coenders. 2002. “Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries: Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 18 (1): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/18.1.17

- Schönwälder, K., and T. Triadafilopoulos. 2016. “The new Differentialism: Responses to Immigrant Diversity in Germany.” German Politics 25 (3): 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2016.1194397

- Simonson, J., N. Kelle, C. Kausmann, and C. Tesch-Römer. 2022. Freiwilliges Engagement in Deutschland. Empirische Studien zum Bürgerschaftlichen Engagement. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Statham, P. 2016. “How Ordinary People View Muslim Group Rights in Britain, the Netherlands, France and Germany: Significant ‘Gaps’ Between Majorities and Muslims?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1082288

- Street, A., and K. Schönwälder. 2021. “Understanding Support for Immigrant Political Representation: Evidence from German Cities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (11): 2650–2667. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1576513

- Verkuyten, M. 2009. “Support for Multiculturalism and Minority Rights: The Role of National Identification and out-Group Threat.” Social Justice Research 22 (1): 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0087-7

- Vertovec, S. 2023. Superdiversity: Migration and Social Complexity. Oxford: Routledge.

- Wasmer, M., and A. Koch. 2003. “Foreigners as Second-Class Citizens? Attitudes Toward Equal Civil Rights for Non-Germans.” In Germans or Foreigners? Attitudes Toward Ethnic Minorities in Post-Reunification Germany, edited by R. Alba, P. Schmidt, and M. Wasmer, 95–118. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Yogeeswaran, K., and N. Dasgupta. 2014. “The Devil Is in the Details: Abstract Versus Concrete Construals of Multiculturalism Differentially Impact Intergroup Relations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106 (5): 772–789. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035830

- Ziller, C., and C. C. Berning. 2021. “Personality Traits and Public Support of Minority Rights.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (3): 723–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1617123