ABSTRACT

This paper explores the relations between parental background, the education level reached and the socioprofessional position of children during their transition to adulthood. The paper links segmented assimilation and institutional theories with a life-course approach. It tests three types of mechanisms of the relationship between parental background and children's lifecourse, which are the critical-period model; the path-dependency; and the cumulative-effect model. The paper uses data from the LIVES-FORS cohort panel survey and develops techniques of Bayesian network modelling. The sample is composed of 788 young people educated in Switzerland before the age of 10 with Swiss or non-Swiss origins interviewed five times from 2013 to 2017. The paper provides striking results of path dependency-effect models. It shows no correlation between the geographical origin of the parents and their children's success at school. The professional position of the children of migrants seems only correlated to their educational capital and gender.

Introduction

With the increasing diversity of migrants of the first generation, the so-called second generation – i.e. the children of migrants – becomes more heterogeneous (Vertovec Citation2007), with their different ethnic and national backgrounds (Chimienti et al. Citation2019). This diversity revives old questions that were raised by the Chicago School a century ago about the role of parental background on the assimilation trajectory of their children (Park Citation1928). Today, Western countries differ strongly from the 1920s US context of migrant integration. Among the many differences is the growing importance in these countries of education systems (Alba and Holdaway Citation2013; Crul and Vermeulen Citation2003) and the diffusion of the ideal of “education-based meritocracy” (Goldthorpe and Jackson Citation2008) in the context of economic globalisation. These countries have shown a substantial increase in the average level of education of their population since WWII. Furthermore, their education systems, organised in more or less stratified tracks, play a role in the distribution and allocation of the workforce in the different segments and strata of the labour market.

In this context, research on the assimilation process of the children of migrants in recent decades went down a new avenue, focusing on the role of education systems in the selection process of the second generation at school and their orientation on the labour market (Alba and Holdaway Citation2013; Crul and Schneider Citation2010; Crul and Vermeulen Citation2003). The issue of the role of education adds to (and interferes with) more traditional research questions on relations between migrants’ social background and the social position of their children in the host society. It also leads researchers to re-explore what aspects of the parental background – between parents’ education, their economic situation in the host country and their migratory origins – impact on the educational and professional life-course of young people and what still bars their mobility and why.

The literature on migrant descendants reveals the young people’s polarised success at school and on the labour market, with an over-representation of migrant descendants at both the bottom and the top of the school-achievement hierarchy when all socio-demographic variables are accounted for (Crul and Schneider Citation2010; Crul and Vermeulen Citation2003; Kasinitz et al. Citation2008). Questions remain open for several reasons: the way migration has been envisaged; the methodological limitations of the existing data on migrant backgrounds and their descendants in most countries (Chimienti et al. Citation2021); predominant cross-sectional surveys limiting the analysis of the roles of variables in the long term (Bolzman, Bernardi, and Le Goff Citation2017).

This paper investigates the role of the parental background, comparing the case of migrants’ descendants with that of young people of Swiss descent on the level of education attained and their socio-professional position on the labour market. By parental background, we mean parental characteristics that reflect some resources that are transmitted by parents to their children. Such characteristics are, first, the parents’ level of education and social position on the labour market. However, nationality could also reflect social positions in the different segments of the social space, especially the labour market, in the host country (Portes and Zhou Citation1993). The research draws on a longitudinal survey that follows a cohort of young adults who grew up in Switzerland (the LIVES Cohort Study, Spini et al. Citation2019). We combined a life-course perspective with a theoretical migration-research perspective, especially that based on institutions’ roles in migrant integration. We applied Bayesian network modelling techniques (Scutari and Denis Citation2021) which allow us to overcome some of the previous limitations on the role of parental background on migrant descendants’ education and employment.

Theoretical perspectives and previous research

The paper draws on an analysis of the role of the parents’ backgrounds on their children’s life paths, looking at both school-achievements and professional position.

The role of migrants’ parental background on their children’s school-achievement

Until the 1980s, scholars mainly analysed the migratory background (nationality, ethnicity, legal situation of stay) of young people as critical determinants of inequality at school and on the labour market (Gordon Citation1964; Hoffmann-Nowotny Citation1973; Park Citation1928). In the US context, the linear assimilationist perspective stated that differences between the descendants of migrants and their peer natives should decrease in the long term. On the contrary, European research hypothesises that migrant descendants reproduce the subordinated social position of their parents because of ethnic discrimination and insufficient integration policies (Hoffmann-Nowotny Citation1985) in the host country. This analysis in terms of ethnic and migratory deficit in Europe and barriers to social mobility is related to more-recent immigration on this continent compared to that in the US, whose population has been created in large proportion by immigration. Studies after the 1980s emphasise that, when controlling for the educative and economic background of the parents, one finds that the descendants achieve a similar level of education as the descendants of native parentage. In other words, social class matters more than foreign or cultural origin (Hutmacher Citation1987; Citation1989).

Further research moves beyond this divide between socioeconomic determinants and migratory background, showing instead the variability of pathways to inclusion among migrants’ descendants. Alejandro Portes and his colleagues (Portes and Zhou Citation1993; Rumbaut and Portes Citation2001) argue that structural assimilation can occur in different economic segments without necessarily coinciding with cultural assimilation. Therefore, children of migrants experience diverse forms of assimilation, depending on their acculturation and/or selectivity of cultural behaviours between the countries of origin and of residence. Portes and Rumbaut (Citation1990) emphasised the role of the context of national policies and structural discrimination on the trajectory of the second generation. They highlight that the negative consequences of assimilation result in a downward assimilation.

Research by Crul and Schneider (Citation2010) adds a new paradigm of analysis where institutions (here, schools) play a more crucial role in educational outcomes than national policies of integration. The different models of education system in Europe define the various institutional contexts which “condition” educational outcomes – such as school performance and level of attainment (Crul and Schneider Citation2010; Crul and Vermeulen Citation2003).

Findings on the second-generation’s school and employment achievements

Previous literature shows that parents’ educational and socioeconomic background – including language skills and ethnicity – partly determines their offspring’s educational success (Huddleston et al. Citation2015). However individual determinants are balanced by meso-sociological factors related to the education system (Crul, Schneider, and Lelie Citation2012). Children with less-educated parents logically rely more on the education system than on their parental capital (Portes and Fernández-Kelly Citation2008). Early access to school, late selection to an academic track and mixed schools are all institutional factors that have a positive effect on children’s educational achievements (Alba and Holdaway Citation2013; Crul and Schneider Citation2010). These institutional factors, together with other structural ones (macro-economic and family policies), partly counterbalance inequalities between families (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2015; Citation2019).

In regards to employment, there is a clear gap between the first generation and the native population, which continues for the second generation in several countries (see, for the UK, Bloch Citation2013; for France, Meurs, Pailhé, and Simon Citation2006; Silberman, Alba, and Fournier Citation2007; Simon Citation2003). People from ethnic-minority groups have, on average, a higher rate of unemployment, earn less, are more frequently located in service-sector jobs and are less likely to be in managerial and professional positions than their native counterparts, both in Europe and the USA (Crul and Mollenkopf Citation2012; Heath and Cheung Citation2007).

Other studies highlight the racism and discrimination that occurs in the labour market (Bloch, Neal, and Solomos Citation2013). Referring to the UK, Heath and Cheung (Citation2007) speak of an “ethnic penalty” – to conceive the intangible discrimination which still leads to worse labour market outcomes among people from ethnic-minority groups. However, when groups and contexts are distinguished, the results are more ambiguous. The situation seems only to be problematic for groups who face ethnic penalties and have a lack of educational capital. Other authors question the segmented assimilation aspect, showing that members of the new second generation do not face more disadvantages than previous ones and that downward assimilation affects only a small number of second-generation youths (Alba and Nee Citation2003; Kasinitz et al. Citation2008; Waldinger and Feliciano Citation2004).

Linking segmented assimilation and institutional theories with a life-Course approach to explain the relation between parental background and the children’s trajectories

The main question raised in this paper is about the relations that connect the parental background with the training trajectory and socio-professional position reached by youth during their transition from education to the labour market. Such questions situate our research from a life-course perspective, in which the children of migrants are followed from birth to the first years of integration onto the labour market.

Several scholars adopting this perspective propose mechanisms to understand relations between the characteristics that individuals acquire as children and the outcome occurring during adulthood or even old age (Pudrovska and Anikputa Citation2014). In this paper, we use these theoretical models to investigate the effects of the parental background of the children of migrants on the children’s socio-professional position on the labour market. The term “effect” is used here to mark how the situation of the past, here the parental background, influences more or less partially the future of individuals, i.e. their position on the labour market.

According to Pudrovska and Anikputa (Citation2014), three mechanisms can be envisaged to analyse relations between parental background and the children’s education and participation on the labour market.

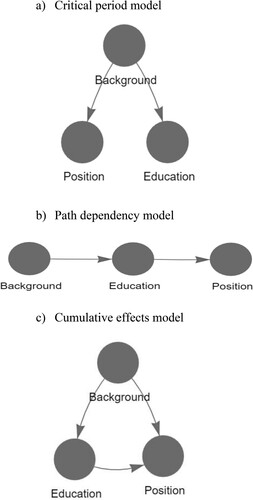

In the critical period model the parental background plays a role in the different phases of the children’s life-course. In contrast, there is no link between the different education paths and social positions (a). In the migration field, such a mechanism would correspond to a highly segmented labour market, in which the children of migrants would inherit the social position of their parents, whatever the level of education they reach (Portes and Zhou Citation1993). In other terms, the social positions of children are determined by the parental ethnic group or nationality and their own position on the labour market while schooling does not play any role in the social position attained by migrant children. The critical period model can thus be related to the downward approach (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001), in which the children of migrants remain in the same low segment as their parents or even in a more precarious condition.

Figure 1. Three theoretical models of relations between parental background, children’s school-achievements and their social position on the labour market (a) Critical period model (b) Path-dependency model (c) Cumulative effects model.

The second mechanism is called the path-dependency model, whereby early events or situations – for example, the children of migrants’ educational trajectory – play the role of mediator between parental background and the children’s socio-professional positions. Resources associated with the parental background are transformed into educational capital, which is later converted into a socio-professional position (b). The path-dependency model can be seen as a kind of Markovian model in which the social position at the t + 1 stage of the life-course (the position of the children of migrants on the labour market) depends on the position at stage t (level of education attained) which, itself, depends on the social position of the parents during childhood at t-1. However, there is no direct effect between positions at t-1 and t + 1. In relation to migration theory, the institutional approach of the effect of schooling (Crul and Vermeulen Citation2003) corresponds to such a path-dependency mechanism. The school can even favour an increase of some resources to migrants’ children which allows them an upward mobility, compared to their parents’ social position. Whilst, in this model, social mobility is more often expected thanks to schools, downward mobility (in comparison to the social position of parents) could occur, in some cases, when resources associated with parental background are not well converted into educational capital – for example, if migrant families fail to understand the education system.

The third model is the cumulative effect model, which mixes aspects of the critical period and the path-dependency models, in a sense that precedent relations remain but there is also a direct relation between t-1 and t + 1. Such a mechanism would be observed for example in case of an ethnic penalty, first during schooling and, second, during the process of insertion into the labour market. If there is a link between the children of migrants’ educational trajectory and the parents’ socio-professional position, the parental background also plays a role at each life-course stage (c). Such a mechanism would correspond to Portes and Zhou’s (Citation1993) model of segmented assimilation. However, theoretical developments are not only related to the cumulation of disadvantages during the life-course but can also be related to the cumulation of advantages (Dannefer Citation2003): some cultural dispositions of migrants’ families of low socio-economic origin could lead to advantages (for instance an ethos of hard work and high education aspiration) which cumulate at each stage of the life-course of the children, while other cultural dispositions could lead to the cumulation of disadvantages.

Hypotheses

In this paper, we investigate the process that relies on the parental background of the children of migrants or of those with native-Swiss parents, together with the level of education reached by these young people and, later, with their socio-professional position on the labour market when they become young adults. Following the different life-course mechanisms linking elements of life-course trajectories (Pudrovska and Anikputa Citation2014), three hypotheses can be formulated:

In the case of the critical period mechanism, we should expect that the school system does not play any role in the labour-market integration of migrant children. Their position would depend solely on the parental nationality and position on the labour market, with the children of migrants remaining in the same segment as their parents.

In the case of the path-dependency mechanism, we should expect a relation between parental and children's social positions but with a mediating effect of the education level reached by the children. According to this hypothesis, resources related to the parental socio-cultural backgrounds are converted into children's educational resources. These resources could even be valued, if children's level of education becomes higher than the parental ones or, alternatively, could be devalued if it becomes lower (Levy and Bühlmann Citation2016).

We expect that the relationship between the parental nationality, education and socio-professional position of the young descendants of migrants will correspond to a cumulative effect model. Here there is a reproduction from one generation to the next, considering both parental nationality and position on the labour market on the one hand and the mediation of the school system on the other.

The second and third hypotheses are not exclusive and could be observed together, according to the characteristics of the parental background. For example, there could be a sequence of capital or resource conversion according to the parental level of education. However, parallel to this sequence, a penalty process in relation to parental nationality can be at play. In contrast, the first hypothesis appears to be an alternative to both the second and the third process, as children's education does not play any role in the reproduction process of social position.

Situating the Swiss context

From 1945 to 1970, Swiss industries massively recruited foreign low-skilled workers based on a guestworker system, most originating from Italy and Spain from the 1960s onwards (Mahnig Citation2005). Labour migration mainly fluctuated according to the economic ups and downs. In the 1980s, new waves of low-skilled economic migrants arrived, mainly from Portugal and the former Yugoslavia. In the 1990s, the country welcomed refugees fleeing civil wars in the former Yugoslavia, especially those escaping from Kosovo. Family reunion increased in the 1990s for Kurdish refugees and immigrants from Turkey (Haab et al. Citation2010). Most of them worked in unskilled jobs. In the same period, a skilled workforce originating from European countries, especially Germany, was recruited by Swiss industries and services. Migration from European countries continued to increase in the 2000s, when Switzerland ratified the Schengen agreement on free exchange within the European Community.

The children of migrants in the Swiss school system

As in several European countries, schools in Switzerland have tried to democratise their access since the second half of the twentieth century. In Switzerland this process led to the creation of more diplomas. Whilst more young people managed to get a degree at the end of mandatory school, this degree does not allow them to continue studying at tertiary level. The Swiss school system is still highly selective, especially according to social origin (Fassa Citation2016).

Selection at school occurs early among students, which is considered disabling for migrants (Alba and Holdaway Citation2013). In most Swiss cantons, the education system operates between the ages of 10 and 12 early selection within highly segregated tracks (Fassa Citation2016; Felouzis and Charmillot Citation2017). Students are oriented, during this first selection process, between tracks that lead, after several years, either to a vocational or to a general/tertiary qualification – a “general culture school” that allows access to tertiary degrees. This first selection into a low-qualifying stream has been identified in previous studies as having long-term effects because it does not allow access to more-qualified education (Buchmann et al. Citation2016; Gomensoro Citation2019; Hupka-Brunner et al. Citation2012; Imdorf Citation2007; Murdoch et al. Citation2014).

The Swiss school system presents however a paradoxical character. It is an integrative system, especially for migrants: very few people who have been socialised in Swiss society end up with only a compulsory degree of education, the vocational education allowing a more-open qualification for those who have difficulty at school. However, the system is highly selective, with a large proportion of students oriented towards vocational tracks at the secondary level. In 2014, there were respectively 72.4 and 57.7 per cent of boys and girls in apprenticeships, 20.7 and 32.6 per cent in general/tertiary education and a residual percentage going to other types of education (Fassa Citation2016). If more and more bridges allowing students to go from a vocational track to generalist/tertiary tracks and vice versa were created, the number of students using these bridges remains relatively small.

The literature shows a critical gap when the children of migrants are compared with the population of native descent. The former, on average, experience upward educational mobility (Rossignon Citation2017). Their intergenerational mobility is greater than that of the children of native-Swiss parents (Bolzman, Fibbi, and Vial Citation2003; Fibbi and Truong Citation2015; Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2019; Schnell and Fibbi Citation2016). However, they have higher rates of school dropout (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2015; Scharenberg et al. Citation2014), lower performances in achievement tests (Cattaneo and Wolter Citation2015; Dustmann et al. Citation2012; Meunier Citation2011) and greater risk of selection into the low-requirement track that limits access to general education (CRSE Citation2018; Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2016; Hofstetter Citation2017). Furthermore, they are at greater risk of discontinuous transitions into post-compulsory school (Scharenberg et al. Citation2014) and long-lasting effects of the early educational selection on later educational attainment and even on labour-market insertion (Gomensoro and Meyer Citation2017; Scharenberg et al. Citation2014). They have a reduced likelihood of attaining tertiary education compared with the majority population (Buchmann et al. Citation2007; Fibbi and Truong Citation2015; Griga and Hadjar Citation2013) and are over-represented in specialised vocational education (Bolzman and Gomensoro Citation2011; Lanfranchi Citation2005).

Socioeconomic factors related to parents’ position on the labour market in Switzerland or on their level of education are not enough to explain these differences between the migrant second generation and the children of native-Swiss parents. Other explanations rely on additional disadvantages – such as the discrimination faced by some members of the migrant second generation – and on a gender basis. This rigid and early selection at school disadvantages families with less capital to assist their children (Schnell and Fibbi Citation2016).

The integration of migrant children onto the Swiss labour market

Although the so-called “new” second generation in Switzerland show lower school-achievements and a poorer educational trajectory (Cattacin, Fibbi, and Wanner Citation2016; Citation2004), the few studies on their labour-market performance indicate quite good access to the labour market, with few differences between them and the descendants of native-Swiss parents in their occupational status, both in international comparison and compared to their parents (Fibbi and Truong Citation2015; Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2019; Lessard-Phillips, Fibbi, and Wanner Citation2012).

However, Fibbi, Lerch, and Wanner (Citation2006) have shown significant discrimination for specific groups, such as those with Turkish and Albanian backgrounds. They are less often invited to job interviews when everything is equal except their names. Moreover, they are subjected to discriminatory practices, such as a lower income (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2019). Zschirnt and Fibbi (Citation2019) also observed more unemployment (10 per cent on average) and higher risks/periods of unemployment for second-generation residents with a Kosovan background when entering the labour market (Guarin and Rousseaux Citation2017), as well as for the second-generation with a Portuguese, former-Yugoslavian or Turkish background during the first stage of their professional career up to 30 years old (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2019).

Methods and data

This paper draws on data from the LIVES Cohort Study (LCS), an annual longitudinal survey following a cohort of young adults who grew up in Switzerland (Spini et al. Citation2019), with an over-representation of the so-called second generation.

The children of migrants are defined as individuals (a) born between 1988 and 1997 (inclusively), (b) residing in Switzerland on 1 January 2013, (c) schooled in Switzerland before the age of 10 and (d) whose parents were born abroad and arrived in Switzerland after the children had reached the age of 18.

The survey’s design aims to capture the complexity of the migration process in Switzerland, comparing migrants’ descendants from different origins with young Swiss natives. This diversity allows us to compare their experiences of the transition to adulthood according to their different family backgrounds, especially transition from school to employment. The LCS focuses mainly on the descendants of economic and unskilled migrants from Southern Europe (especially Portugal), but above all, the descendants of migrants or refugees from the former Yugoslavia and Turkey. For this paper, we used LCS data from Wave 1 in 2013, where respondents were aged 15–25 years old, to Wave 5 in 2017, when they were aged 19–29 years old. Although the sample included 1691 cases at Wave 1, we developed our analysis using only the part of the sample that answered the “Social Origins’ (SO) module of the questionnaire – this covered 849 cases. The data, including those concerning the parents, were collected based on respondent answers to our survey. We keep for our analyses all individuals without missing data (n = 788).

Variables

For our analysis, we used three sets of variables: (1) parental background; (2) ascribing variables and variables related to the respondent’s childhood; and (3) life-course processes variables.

Parental background represents different variables relating to the parents’ situation when their children – the respondents – were 15 years old ():

Parental nationality: because of the strong homogamy of parental unions according to nationality, we decided to build a variable that considers the nationality of both parents rather than to take two separate ones. This variable was constructed according to the most frequent parental nationalities of the cohort survey respondents. It distinguishes between people surveyed according to whether their two parents are Swiss, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, from Kosovo, from another Balkan country, from Turkey or from a European country and a broader category of parent originally from another country. Furthermore, a distinction is made between nationally mixed parents for Swiss and European mixed couples ().

Father’s and mother’s level of education: our respondents’ father and mother were distinguished according to their level of education when their child was 15 years old. For each parent, three levels of education were determined, namely compulsory-school, secondary-school and general-tertiary level ().

Father’s and mother’s socio-professional position: we used the European socio-professional category (ESeC) of fathers and mothers when their child was 15 years old. We started from the ten-positions schema. We grouped them into seven categories: (i) manager/liberal employees; (ii) small self-employed; (iii) intermediate employees; (iv) skilled; (v) lower-grade white collar workers; (vi) skilled, semi-skilled, non-skilled (factory) workers; (vii) unemployed (this last category assembles all unemployed people, like those searching for a job, homemakers, etc.) – see .

Ascribing variables and variables related to childhood are the gender of the respondents, the birth cohort – a distinction is made between respondents born between 1987 and 1993 and those born in 1994 and after – and respondents’ birthplace: each respondent is characterised according to whether they were born in Switzerland or born abroad (the 1.5 generation) – see .

Life-course processes variables are other variables related to the trajectory of each respondent. Level of education: we distinguished respondents by their level of education with four possible positions (compulsory, vocational, upper-secondary and tertiary); Still in education or not: this variable indicates whether, in 2019, respondents were still in education or not; and respondents’ socio-professional position in 2019: we have again used the ESeC category with seven positions.

Table 1. Description of characteristics (%, n = 788).

Methods of analysis

Relations between the parental background, the educational level reached by the children and the family’s socio-professional position have been investigated using Bayesian network modelling (Scutari and Denis Citation2021). The main interest of this approach is to build channels of relations between variables that allow overtaking the simple scheme of relations between dependent and independent covariates, as in regression analysis. These techniques are based on the estimation of conditional probabilities between variables. In the present case, a variable can depend on some variables but is susceptible to influence the distribution of others.

We are especially interested in using these methods because of our life-course perspective in which three moments are considered: (1) the birth and primary socialisation of respondents and heritability of parental resources; (2) the schooling and eventual conversion of parental resources into schooling resources; (3) integration on the labour market and access to a social position with eventual conversion of schooling resources as well as initial parental resources. Bayesian network modelling thus allows us to investigate the cumulative effects versus path-dependency effects or critical period mechanisms.

All variables related to parental background, childhood and respondent life-course described above were taken to estimate the Bayesian model. Given the high number of relationships and sequences of variables to be theoretically tested with an initial number of nine variables, machine-learning techniques are used to estimate the “best” network of variables through a hill-climbing algorithm of optimisation (Scutari and Denis Citation2021). The general idea behind this algorithm is to test the dependence between a variable and another by computing an AIC score. This score is compared to the one of the model without this tested relationship (Weakliem Citation2016). The final model corresponds to the one which has the higher AIC.

Scutari and Denis (Citation2021) emphasise that relationships between variables can also be tested according to the expertise of operators estimating a Bayesian network model. We took on this expert role with two aims. First, we limited machine-learning techniques by specifying the irreversibility of the life-course as a general rule. According to this rule, we first considered that parental background and ascriptive characteristics cannot depend on the respondent’s level of education trajectory and professional situation. Similarly, we specified that respondents’ education trajectory should not be considered dependent on their future professional position. Second, after having estimated our best Bayesian model, we tried several hypotheses related to the different life-course mechanisms. The general idea is to test whether the imposition of some relations between variables will strongly decrease AIC scores or not (). Estimations of Bayesian networks are made with the package bnlearn in R Cran (Scutari Citation2010).

Table 2. Test of relationships between variables and AIC scores.

Results

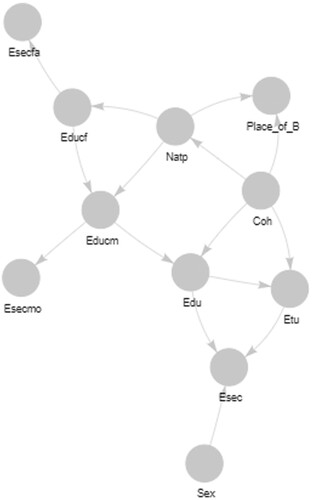

The results of the best Bayesian model are presented in . The relationship between variables can be divided into three distinct parts: (1) connections between parental background variables; (2) connections between parental background and children’s education variables; and (3) connections between children’s education and their socio-professional position. The main general result is that there is no direct connection between the parental background and the children’s professional position. When there are connections, they are indirect, passing through children’s level of education attained. In other words, the main general life-course mechanism looks like a path-dependency mechanism.

Figure 2. Results of the Bayesian network model. Coh = birth cohort; Sex = gender; Natp = nationality of parents; Educm = mother’s level of education; Educf = father’s level of education; Esecmo = mother’s European socioeconomic class; Esecfa = father’s European socioeconomic class; Edu = respondent’s level of education; Etu = Person still in education or not; Esec = European socioeconomic class of respondent. Reading note: The Bayesian network model has been estimated on the overall respondent sample present in the lives Cohort study wave 5 (migrants and Swiss native children). All variables are considered to be nominal. An arrow indicates a direct dependance between two variables, the head indicating the direction of the dependency. For example, the distribution of Edu (respondent’s reached level of education) is dependent from the variable Educm (respondent’s mother’s level of education). Converging edges to a same dependent variable from two (or more) variables indicate an interacting effect of these two variables on the dependent variable. One example is the interacting effects of both Educm and Coh – the cohort variable – on Edu. These effects are detailed in . These interacting effects can also be interpreted as having a moderating effect – for example, the moderating effect of Coh on the dependence between Educm and Edu: the distribution of the respondent’s reached level of education according to the education level of his/her mother differs according to the respondent cohort of belonging. Two successive arrows linking three variables indicate a mediating effect. For example, the effect of the respondent’s mother’s level of education on the respondent’s social position on the labour market (Esec variable) is mediated by the respondent’s reached level of education. Relations described by arrows are all statistically significant (see the methodology section for details of the scoring procedure used to detect significance).

Relations between parental-background variables

Parent nationalities are connected with the father’s level of education (). This connexion confirms that the distribution of the father’s level of education differs according to his nationality. Very few fathers who have Swiss or mixed foreign–Swiss nationality only have a compulsory degree of education, in contrast to foreign fathers – mainly Portuguese or Turkish men who migrated to Switzerland (). The father’s level of education is also related to his position on the labour market. Such relations between parental-background variables reflect the Swiss context of migration, in which migrant skills on the labour market are related to their nationality due to labour-recruitment and migration policies in Switzerland: low-skilled migrants coming from the former Yugoslavia or, alternatively, high-skilled migrants from countries of Central and Northern Europe (as shown elsewhere, Guichard et al. Citationforthcoming).

Table 3. Father’s level of education by parental nationality (%, n = 788).

The mother’s level of education is first related to parental nationality and second to her partner’s level of education (). This last relationship reflects the homogamous education of spouses in households. A similar relationship is observed between the mother’s level of education and her socio-professional position.

Relationship between respondents’ parental background and level of education

Our estimations show a connection between the mother’s level of education and that of her descendants (Educm – Edu in ). This result confirms previous literature which has already demonstrated that the parental level of education is a significant predictor of children’s educational and behavioural outcomes (Haveman and Wolfe Citation1995). In the present case, it is more the mother’s level of education than the father’s that seems to play such a role. It is, however, interesting to note that the score of the Bayesian network model does not strongly increase in absolute value if we estimate a model in which we cancel the relation between the mother’s and her children’s level of education but impose a relationship between the father’s and his children’s levels of education – or even if we impose the two relations (, models 2 and 3). Such results indicate that, in the end, either the mother’s or the father’s level of education we take into consideration, there is a strong link between parental level of education and that achieved by their child.

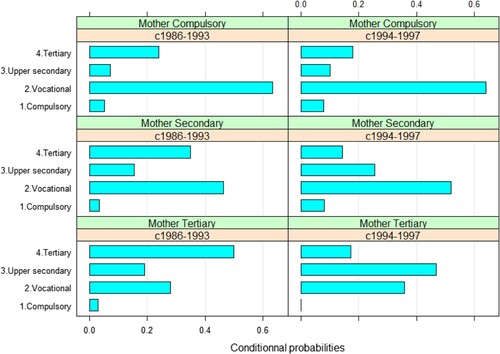

Details of the relationship between respondents’ level of education and their mother’s education are represented by a set of bar plots drawn in . The three-bar plots on the left side of the graph concern respondents born before 1994, while those on the right concern those born in or after 1994. On the left side, the bar plots situated at the bottom and the middle show the reproduction of the level of education between mothers and respondents. The likelihood of attaining a secondary degree is the greatest for respondents whose mother also has one (whether vocational or upper-secondary) – see the middle-left side of . One in three gets a tertiary level of education. Similar results can be observed in the youngest cohort, as the proportion of respondents with a tertiary level of education is low. However, it could be a question of timing for the youngest cohort, as several of them were still studying at the moment of the interview and had not yet reached a tertiary level.

The bar-plot to the bottom left of shows that half of the respondents with a mother with a tertiary level of education also reach it themselves. Nearly half of the other respondents get a secondary education, while those who experience backward mobility to a compulsory level of education are scarce. The youngest cohorts also seem to follow this trend. Many of them only have an upper-secondary level of education, although many will reach a tertiary level.

Bar-plots to the top left of concern respondents whose mother has a compulsory level of education. Remarkably, more than 60 per cent of such respondents reached a vocational level of education in both cohorts. A little more than 20 per cent of respondents achieved a tertiary level. This upward mobility supports the idea that the system of education in Switzerland is integrative. However, the percentage of those who have a compulsory level of education is greater than for those whose mother has a higher level (almost 10 per cent vs respectively, 6 and 5 per cent when the mother has a level of secondary and tertiary education).

These results relativise the relationship between the parental education and their children’s educational trajectory, showing that a low educational background can be balanced in part by (an integrative) school system. We did not find any direct relationship between the mother’s or father’s socio-professional position and their children’s level of education. If we impose such relations, the AIC scores of models evaluating the relationship increase significantly in absolute value (see , models 4 and 5). This result indicates that the level of education attained is related to the parental ones, even if these parental levels of education were reached in the origin country. However, the children’s level of education does not depend on the parental socio-economic position.

Interestingly, we do not observe direct links between parental nationality and the respondent’s level of education. This result could be interpreted in two ways: it could mean that there is no direct ethnic penalty in the Swiss system of education for the groups considered in this sample because they do not represent the most vulnerable and they have a white European background; it could also mean that the education of the parents has a stronger power and that their nationality is conflated with their education (as their national background often equates to a certain education and socio-economic position in Switzerland see Guichard et al. Citationforthcoming) and disappears, therefore, in the relationship with their children’s educational trajectory.

Transition from school to the labour market

The final part of the Bayesian network model shows a relationship between the respondent’s education level and his or her socio-professional position. It is interesting to note that there is also no connection between parental levels of education or socio-professional positions and the respondents’ (their descendants’) socio-professional position. The imposition of a relationship in the variables network between the mothers’ level of education, for example, and the socio-professional position of their child leads to a decrease in the AIC score (, model 6).

Commensurate with our hypotheses, the Bayesian network model shows a path-dependency mechanism about the relationship between parental education and the child’s socio-professional position. Parental background related to the level of education plays a role in the level of education reached by our respondents. The respondent’s level of education is then converted into a socio-professional position. However, our results reveal the absence of a connection between the parent’s nationality and the respondent’s socio-professional position. Indeed, when we impose relationships between parent’s nationality and the child’s level of education and/or her/his socio-professional position, we obtain models with very bad scores (see , models 7 and 8). Such an absence of relationships contradicts our hypothesis of a cumulative effect of parental nationality on a child’s trajectory due to an ethnic penalty, which means that our third hypothesis is rejected.

As mentioned above, the reasons for this lack of relation between the nationality of the parents and the child’s educational trajectory and socio-professional position could be firstly that our sample does not focus only on the most racialised – and discriminated against – young people, those with a non-white phenotype and/or Muslim religion and lower capital, for whom national or ethnic prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination are the strongest. Secondly the fact that the education of the parents is conflated with their nationality might also hide the specific effect of the later; Thirdly, this lack of relationships might be a sign that the Swiss education system manages to balance inequalities because of the economic stability in Switzerland and the less-segregated schools, thanks to the urban neighbourhood mixed policy (Mahnig Citation2005). Public schools are socially and culturally mixed until the end of compulsory education. Furthermore, the Swiss education system has the particularity of including certification for vocational formation. Almost all young people end up with a certificate after mandatory school. In this way, the education route ensures employment and broadly determines the professional trajectory (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2019). The unemployment rate of young people living in Switzerland is also one of the lowest in Europe. The educational system manages to balance inequalities regarding national background, as neither the educational level nor the socioeconomic position of the young seems to be related to their parents’ national origins.

Our Bayesian network does not show any result that could be interpreted in terms of critical period effect (Pudrovska and Anikputa Citation2014). For example, there are no relations between parental nationalities or socioeconomic positions and those occupied by their children, which conduces us to reject the Portes theoretical hypothesis of a downward approach in the case of Switzerland (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2001). Indeed, immigrants from some nationalities are recruited to work in unskilled jobs but most of their children, through the Swiss school systems and the labour market rules, are granted better socioeconomic positions than their parents.

Interestingly the results of the Bayesian model show a relationship between the socio-professional position and the gender of the respondent. This means that the education system is still not able to balance gendered inequalities regarding educational capital. Until 1990, women in Switzerland had a lower level of education than men (Buchmann and Charles Citation1993) but, since then, they have improved their level of education and overtaken men in the number of enrolments in general tertiary education in 2009 (CRSE Citation2018; Imdorf and Hupka-Brunner Citation2015). Moreover, in recent years, women have caught up with men in general education (Guilley et al. Citation2019) and have a higher success rate, especially regarding vocational training (CRSE Citation2018). Despite the more significant presence of women in education and their educational attainment, women still do not achieve the same occupational status as men (Guilley et al. Citation2019; Imdorf and Hupka-Brunner Citation2015).

In sum, the relationships we found, on the one hand, between the parents’ level of education and their socio-professional positions and, on the other, between the respondents’ (the young people’s) level of education and their socio-professional position, show a path-dependency mechanism. We do not observe a relationship between parental nationality and the respondent’s socio-professional position which means that our assumption of a critical period mechanism in parental nationality is not verified. The Bayesian network shows an interesting result related to respondents’ gender, which seems to play a role in their socio-professional position of respondents.

Discussion and conclusion

This research addresses the long-standing issue of the link between the parental background of the children of migrants, their performance in the school system and their socio-professional position on the labour market in the Swiss context. It innovates by combining a life-course perspective with a theoretical migration-research perspective, and by applying Bayesian network modelling techniques to examine this issue.

The results show a link between parental national origin, education and socio-professional position in Switzerland, reflecting the Swiss context of migration based on “ethnic labour selection”. Migrants are recruited to fulfil both the unskilled and skilled economic needs of the labour market. The unskilled were recruited in Italy and Spain in the 1960s–1970s and in Portugal and the former Yugoslavia in the 1980s, while highly skilled workers were recruited in northern countries of the European community. This relationship constructed by the Swiss migration policy ensures a quasi equivalence between the nationality of the migrant and his/her skills, which has reinforced trends towards the essentialisation and stigmatisation of migrants.

Besides, the results show no relation between parental nationality and the level of education attained or the socio-professional position reached by their children. No direct link was found between parental nationality and young people’s level of education, which means that for our sample, composed of young with parents coming from Europe, the national origin of their parents did not have a direct influence on their level of education nor on their access to labour market. Three explanations were provided for this lack of link. The first of them is related to the composition of our sample, which does not include the most vulnerable people in terms of their parents’ level of education, nor those most at risk of being discriminated against.

Secondly, the strong relationship that exists between parents’ level of education and their nationality (migrants with low levels of educational capital were recruited in poorer countries than Switzerland) can also mask the specific role of the latter on their children’s educational and professional trajectory. It also means that to study the role of ethnic and national background more specific research design and methods are needed as shown among others in Switzerland by Fibbi, Lerch, and Wanner (Citation2006) and Zschirnt and Fibbi (Citation2019) or more generally by Bulmer and Solomos (Citation2004).

Third, the Swiss educational system has democratised its access and provided several bridges for those who fail to get a tertiary degree or at least a professional diploma. Although it remains still highly selective, these transformations might explain that the institutional level – schools – manage to convert parental backgrounds.

Indeed, the main result of our study is that it shows a path-dependency mechanism from the parental level of education to their children's level of education and from the children's level of education to their socio-professional position. This mechanism underlines the role of social reproduction played by the school system in Switzerland. The parental cultural capital is converted into children's cultural capital which, itself, “determines” their socio-professional position on the labour market. At the contrary, the parental cultural and social capital related to the nationality of parents does not play a role in the social position reached by their children. Indeed, our hypothesis of the critical period effect of parental nationality was not confirmed. This means that the parental social capital does not help, in confirmation of Bolzman, Fibbi, and Vial (Citation2003) who add that the social capital acquired by migrant children at school plays a role. The school system plays an “integrative” role for the children of parents with a low level of education, as most of them reach a secondary and even a tertiary level of education in Switzerland. It means that the Swiss educational system has managed to balance the main inequalities thus far. But to continue to limit the reproduction of inequalities faced by the future children of migrants, the Swiss education system will probably need more efforts in the future, given the population increase and costs it will represent, as well as the additional handicaps faced by those children of migrants with a refugee background or unaccompanied minors (such as the precarity of the situation of stay, the sometimes fragmented education of their parents and the racialisation related to their non-white phenotypes and non-Christian religious beliefs). These efforts could be focused on the age at which starts the selection process between vocational and general tracks (at 11 and 12 years old). Such an early selection constitutes a disadvantage for some descendant of migrants (Alba and Holdaway Citation2013), for example for those whose maternal language differ from the national languages spoken in Switzerland. More generally, for those with parents lacking resources allowing to monitor their children education, the postponement of the selection starting process could represent a more inclusive policy and an easy amelioration to put in place. Another way could be to continue to develop bridges after this starting process allowing to enter higher tracks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alba, R., and J. Holdaway. 2013. The Children of Immigrants at School: A Comparative Look at Integration in the United States and Western Europe. New York: NYU Press.

- Alba, R., and V. Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bloch, A. 2013. “The Labour Market Experiences and Strategies of Young Undocumented Migrants.” Work, Employment and Society 27 (2): 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012460313.

- Bloch, A., S. Neal, and J. Solomos. 2013. Race, Multiculture and Social Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bolzman, C., L. Bernardi, and J.-M. Le Goff. 2017. “Introduction: Situating Children of Migrants Across Borders and Origins.” In Situating Children of Migrants Across Borders and Origins, Vol. 7, edited by C. Bolzman, L. Bernardi, and J.-M. Le Goff, 1–21. Dordrecht: Springer Open.

- Bolzman, C., R. Fibbi, and M. Vial. 2003. “Que Sont-ils Devenus? Le Processus d’Insertion des Adultes Issus de la Migration.” In Les Migrations et la Suisse: Résultats du Programme National de Recherche ‘Migrations et Relations Interculturelles’, edited by H.-R. Wicker, R. Fibbi, and W. Haug, 434–459. Zurich: Seismo.

- Bolzman, C., and A. Gomensoro. 2011. “Schulkinder von Familien aus der Türkei.” In Neue Menschenlandschaften Migration Türkei-Schweiz 1861–2011, edited by M. Ideli, V. Suter Reich, and H.-L. Kieser, 283–305. Zurich: Chronos Verlag.

- Buchmann, M., and M. Charles. 1993. “The Lifelong Shadow: Social Origins and Educational Opportunities in Switzerland.” In Persistent Inequalities: Changing Educational Stratification in Thirteen Countries, edited by Y. Shavit, and H.-P. Blossfeld, 177–192. Boulder: West View Press.

- Buchmann, M., I. Kriesi, M. Koomen, and C. Imdorf. 2016. “Differentiation in Secondary Education and Inequality in Educational Opportunities: The Case of Switzerland.” In Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality: An International Comparison, edited by H.-P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, J. Skopek, and M. Triventi, 111–128. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Buchmann, M., S. Sacchi, M. Lamprecht, and H. Stamm. 2007. “Switzerland: Tertiary Education Expansion and Social Inequality.” In Stratification in Higher Education: A Comparative Study, edited by Y. Shavit, R. Arum, and A. Gamoran, 321–348. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press.

- Bulmer, M., and J. Solomos. 2004. Researching Race and Racism. London: Routledge.

- Cattacin, S., R. Fibbi, and P. Wanner. 2016. “La Nouvelle Seconde Génération. Introduction au Numéro Spécial.” Swiss Journal of Sociology 42 (2): 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjs-2016-0009.

- Cattaneo, M., and S. Wolter. 2015. “Better Migrants, Better PISA Results: Findings from a Natural Experiment.” IZA Journal of Migration 4 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40176-014-0025-4.

- Chimienti, M., A. Bloch, L. Ossipow, and C. W. de Wenden. 2019. “Second Generation from Refugee Backgrounds in Europe.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (1): 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0138-2.

- Chimienti, M., E. Guichard, C. Bolzman, and J.-M. Le Goff. 2021. “How Can we Categorise ‘Nationality’ and ‘Second Generation’ in Surveys Without (re)Producing Stigmatisation?” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00237-1.

- CRSE. 2018. L’Éducation en Suisse – Rapport 2018. Aarau: Centre Suisse de Coordination Pour la Recherche en Éducation.

- Crul, M., and J. Mollenkopf, eds. 2012. The Changing Face of World Cities. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Crul, M., and J. Schneider. 2010. “Comparative Integration Context Theory: Participation and Belonging in new Diverse European Cities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (7): 1249–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419871003624068.

- Crul, M., J. Schneider, and F. Lelie. 2012. The European Second Generation Compared: Does the Integration Matter?. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Crul, M., and H. Vermeulen. 2003. “The Second Generation in Europe.” International Migration Review 37 (4): 965–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00166.x.

- Dannefer, D. 2003. “Cumulative Advantage/Disadvantage and the Life Course: Cross-Fertilizing Age and Social Science Theory.” The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58 (6): S327–S337. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327.

- Dustmann, C., T. Frattini, G. Lanzara, and Y. Algan. 2012. “Educational Achievement of Second-Generation Immigrants: An International Comparison.” Economic Policy 27 (69): 143–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00275.x.

- Fassa, F. 2016. Filles et Garçons Face à la Formation. Les défis de l'égalité. Lausanne: Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires de Lausanne.

- Felouzis, G., and S. Charmillot. 2017. “Les Inégalités Scolaires en Suisse.” Social Change in Switzerland 8: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.22019/SC-2017-00001.

- Fibbi, R., M. Lerch, and P. Wanner. 2006. “Unemployment and Discrimination Against Youth of Immigrant Origin in Switzerland: When the Name Makes the Difference.” Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’Integration et de la Migration Internationale 7 (3): 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-006-1017-x.

- Fibbi, R., and J. Truong. 2015. “Parental Involvement and Educational Success in Kosovar Families in Switzerland.” Comparative Migration Studies 3 (1): 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-015-0010-y.

- Goldthorpe, J. H., and M. Jackson. 2008. “Education-based Meritocracy: The Barriers to its Realisation.” Stato e Mercato 1: 31–60.

- Gomensoro, A. 2019. “Les Parcours Scolaires des Descendants D’Immigrés en Suisse: Influences et Imbrications des Dimensions Familiales, Individuelles et Institutionnelles.” PhD diss. University of Lausanne.

- Gomensoro, A., and C. Bolzman. 2015. “The Effect of the Socioeconomic Status of Ethnic Groups on Educational Inequalities in Switzerland: Which ‘Hidden’ Mechanisms?” Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 7 (2): 70–98.

- Gomensoro, A., and C. Bolzman. 2016. “Les trajectoires éducatives de la seconde génération. Quel déterminisme des filières du secondaire et comment certains jeunes le surmontent ?” Swiss Journal of Sociology 42 (2): 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjs-2016-0013.

- Gomensoro, A., and C. Bolzman. 2019. “When Children of Immigrants Come of Age. A Longitudinal Perspective on Labour Market Outcomes in Switzerland.” TREE Working Paper Series.

- Gomensoro, A., and T. Meyer. 2017. “TREE (Transitions from Education to Employment): A Swiss Multi-Cohort Survey.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 8 (2): 209–224. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v8i2.424.

- Gordon, M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Griga, D., and A. Hadjar. 2013. “Inégalités de Formation Lors de L'accès à L'enseignement Supérieur Selon le Sexe et le Contexte Migratoire: Résultats de L'analyse des Situations Suisse, Allemande et Française.” Revue Suisse des Sciences de L'éducation 35 (3): 493–513.

- Guarin, A., and E. Rousseaux. 2017. “Risk Factors of Labor-Market Insertion for Children of Immigrants in Switzerland.” In Situating Children of Migrants Across Borders and Origins: A Methodological Overview, edited by C. Bolzman, L. Bernardi, and J.-M. Le Goff, 55–75. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Guichard, E., M. Chimienti, C. Bolzman, and J.-M. Le Goff. forthcoming. “When National Origins Equal Socio-Economic Background: The Effect of the Ethno-Class Parental Background on the Education of Children Coming of Age in Switzerland.”

- Guilley, E., C. Carvahlo Arruda, J.-A. Gauthier, L. Gianettoni, D. Gross, D. Joye, E. Moubarack, and K. Müller. 2019. À l’École du Genre. Projets Professionnels de Jeunes en Suisse. Zurich and Geneva: Seismo Verlag.

- Haab, K., C. Bolzman, A. Kugler, and O. Yilmaz. 2010. Diaspora et communautés de migrants de Turquie en Suisse. Bern: Office fédéral des migrations.

- Haveman, R., and B. Wolfe. 1995. “The Determinants of Children’s Attainments: A Review of Methods and Findings.” Journal of Economic Literature 33 (4): 1829–1878.

- Heath, A. F., and S. Y. Cheung, eds. 2007. Unequal Chances: Ethnic Minorities in Western Labour Markets. London: British Academy.

- Hoffmann-Nowotny, H.-J. 1973. Soziologie des Fremdarbeiterproblems. Stuttgart: Enke Verlag.

- Hoffmann-Nowotny, H.-J. 1985. “The Second Generation of Immigrants: A Sociological Analysis with Special Emphasis on Switzerland.” In Guests Come to Stay: The Effects of European Labor Migration on Sending and Receiving Countries, edited by R. Rogers, 109–134. London: Routledge.

- Hofstetter, D. 2017. Die Schulische Selektion als Soziale Praxis. Aushandlungen von Bildungsentscheidungen Beim Übergang von der Primarschule in die Sekundarstufe I. Weinheim and Basel: Beltz.

- Huddleston, T., Ö Bilgili, A.-L. Joki, and Z. Vankova. 2015. Migrant Integration Policy Index | MIPEX 2015. Brussels: Migration Policy Group.

- Hupka-Brunner, S., S. Kanji, M. M. Bergman, and T. Meyer. 2012. Gender Differences in the Transition from Secondary to Post-Secondary Education in Switzerland. Report Commissioned by the OECD (TOR/PISA-l). Basel: TREE.

- Hutmacher, W. 1987. “Le passeport ou la position sociale.” In Les Enfants de Migrants à l’École, edited by CERI, 228–256. Paris: OECD.

- Hutmacher, W. 1989. “Migration, Production et Reproduction de la Société.” In Etre Migrants: Approches des Problèmes Socio-Culturels et Linguistiques des Enfants Migrants en Suisse, edited by A. Gretler. Bern: Lang.

- Imdorf, C. 2007. “Une Enquête Dans le Cadre du PNR-51. Pourquoi les Entreprises Formatrices Hésitent-Elles à Engager des Jeunes étrangers?” Panorama 2: 29–30.

- Imdorf, C., and S. Hupka-Brunner. 2015. “Gender Differences at Labor Market Entry in Switzerland.” In Gender, Education and Employment, edited by H.-P. Blossfeld, J. Skopek, M. Triventi, and S. Bucholtz, 267–286. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kasinitz, Ph., J. H. Mollenkopf, M. C. Waters, and J. Holdaway. 2008. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. New York: Russell Sage Foundation and Harvard University Press.

- Lanfranchi, A. 2005. “Nomen est Omen: Diskriminierung bei Sonderpädagogischen Zuweisungen.” Schweizerischer Zeitschrift Für Heilpädagogik 7–8: 45–48.

- Lessard-Phillips, L., R. Fibbi, and P. Wanner. 2012. “Assessing the Labour Market Position and its Determinants for the Second Generation.” In The European Second Generation Compared, edited by M. Crul, J. Schneider, and F. Lelie, 165–224. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Levy, R., and F. Bühlmann. 2016. “Towards a Socio-Structural Framework for Life Course Analysis.” Advances in Life Course Research 30: 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2016.03.005.

- Mahnig, H., ed. 2005. Histoire de la Politique de Migration, D’Asile et D’Intégration en Suisse Depuis 1948. Zurich: Seismo.

- Meunier, M. 2011. “Immigration and Student Achievement: Evidence from Switzerland.” Economics of Education Review 30 (1): 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.017.

- Meurs, D., A. Pailhé, and P. Simon. 2006. “Persistance des Inégalités Entre Générations Liées à L'immigration: L'accès à L'emploi des Immigrés et de Leurs Descendants en France.” Population 61 (5/6): 763–801. https://doi.org/10.3917/popu.605.0763.

- Murdoch, J., C. Guégnard, M. Koomen, C. Imdorf, and S. Hupka-Brunner. 2014. “Pathways to Higher Education in France and Switzerland.” In Higher Education in Societies: A Multi Scale Perspective, edited by G. Goastellec, and F. Picard, 149–169. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Park, R. E. 1928. “Human Migration and the Marginal Man.” American Journal of Sociology 33 (6): 881–893. https://doi.org/10.1086/214592.

- Portes, A., and P. Fernández-Kelly. 2008. “Introduction.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 620: 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716208322829.

- Portes, A., and R. G. Rumbaut. 1990. Immigrant America: A Portrait. 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and R. G. Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The new Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Pudrovska, T., and B. Anikputa. 2014. “Early-life Socioeconomic Status and Mortality in Later Life: An Integration of Four Life-Course Mechanisms.” Journal of Gerontology 69 (3): 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt122.

- Rossignon, F. 2017. “Transition to Adulthood for Vulnerable Populations in Switzerland: How Past Trajectories Matter.” PhD diss., Université de Lausanne, Faculté des Sciences Sociales et Politiques.

- Rumbaut, R. G., and A. Portes, eds. 2001. Ethnicities: Children of Immigrants in America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Scharenberg, K., M. Rudin, B. Müller, T. Meyer, and S. Hupka-Brunner. 2014. Parcours de Formation de L’École Obligatoire à L’Âge Adulte: Les Dix Premières Années. Basel: TREE.

- Schnell, P., and R. Fibbi. 2016. “Getting Ahead: Educational and Occupational Trajectories of the ‘New’ Second-Generation in Switzerland.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 17 (4): 1085–1107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0452-y.

- Scutari, M. 2010. “Learning Bayesian Networks with the bnlearn R Package.” Journal of Statistical Software 35 (3): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v035.i03.

- Scutari, M., and J.-B. Denis. 2021. “Bayesian Networks.” In With Examples in R. 2nd edition. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Silberman, R., R. Alba, and I. Fournier. 2007. “Segmented Assimilation in France? Discrimination in the Labour Market Against the Second Generation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870601006488.

- Simon, P. 2003. “France and the Unknown Second Generation: Preliminary Results on Social Mobility.” International Migration Review 37 (4): 1091–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00171.x.

- Spini, D., N. Dasoki, G. Elcheroth, J.-A. Gauthier, and J.-M. Le Goff. 2019. “The LIVES-FORS Cohort Survey: A Longitudinal Diversified Sample of Young Adults Who Have Grown Up in Switzerland.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 10 (3): 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1332/175795919X15628474680745.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-Diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465.

- Waldinger, R., and C. Feliciano. 2004. “Will the new Second Generation Experience ‘Downward Assimilation’? Segmented Assimilation re-Assessed.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (3): 376–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/01491987042000189196.

- Wanner, P. 2004. Migration et Intégration: Populations Etrangères en Suisse. Neuchâtel: Office Fédéral de la Statistique.

- Weakliem, D. 2016. Hypothesis Testing and Model Selection in the Social Sciences. New York: Gilford Press.

- Zschirnt, E., and R. Fibbi. 2019. “Do Swiss Citizens of Immigrant Origin Face Hiring Discrimination in the Labour Market?” On the Move Working Paper No. 20.