ABSTRACT

In the post-9/11 and 7/7 era in Britain, Muslim subjects have been racially labelled as non-white, equated with a security threat. Similarly, within Turkey's secular public sphere, Muslims are portrayed as anti-modern and illiberal. This prompts some British Turkish Muslims, descendants of immigrant Turks, to strategically embrace white, European identities. Drawing from semi-structured interviews, this article reveals how 'whiteness' is a privileged category that certain Turkish Muslims adopt or align with to counter Islamophobia. Following Hall's racism framework and Gramsci's ideas, the paper underscores how British Turks sustain and propagate 'whiteness' to assimilate into society and evade racialisation challenges faced by other Muslims. Importantly, the article interprets the adoption of hegemonic white identities not just as a response to British Islamophobia but also as a manifestation of a secular Turkish Orientalism, depicting Islam as a backward, illiberal, and irrational religion.

Introduction

This article considers how the racialization of Muslims as a non-white security threat and Islam as an anti-modern and illiberal religion encourages British Turkish Muslims to occasionally (and somewhat strategically) embrace “whiteness” in order to sidestep, avoid or oppose Islamophobic discursive formations, face-to-face encounters and institutional discrimination. We view whiteness as a “floating signifier” that, while undoubtedly (and overwhelmingly) an enduring marker of the “contingent hierarchies” of class, gender, nation, religion and status (Garner Citation2012), refers not to something essential or fixed, but is “[…] subject to the constant process of redefinition and appropriation […] made to mean something different in different cultures, in different historical formations at different moments of time” (Hall Citation2021, 362). Not least is redefinition and appropriation apparent in the racialization of differences within groups that identify and/or are identified as “white”. In this article, we address the ways and circumstances that a selection of British Turkish Muslims negotiate whiteness in relation to their cultural identity and their encounters with Islamophobia. Such accounts, collected via semi-structured interviews, reflect on the racialization of Muslims in Britain as non-white while also referencing the early republican Turkish emphasis on the whiteness and Europeanness of Turks writ large. Both are hegemonic (and nationalist) forms of whiteness constructed in opposition to Islam and Muslim identities.

For British Muslim Turks, Islamophobia is experienced from apparently contradictory directions. From the Turkish context, Islam is viewed as traditional and is associated with conservatism; it is viewed as oppositional to secular, “modern” and Western imaginings of the nation. Islamophobia is deeply embedded in Turkish society and has persisted over time since the Tanzimat Westernisation Era (from 1839) and, in particular, post-1922.Footnote1 For decades stretching into the first years of the 2000s, the Turkish mass media demonstrated a tendency to portray all that is related to religion (and especially Islam) in a negative light (Yardım and Easat-Daas Citation2018). It was not until the AK (AKP) partyFootnote2 came to power in 2002 that Islamic domains and Islamic conservatives became opinion makers and utilized their own publications and media outlets in a confident manner (Pak Citation2004). Once relegated to the periphery of the secularist-driven social changes, the Islamic conservatives started to voice their objections against the unilaterally imposed monolithic secular ethos (Pak Citation2004). In the British context, although it is well documented that Muslim identity and Islam were already stigmatized (Runnymede Trust Citation1997), it wasn’t until the 9/11 attacks that Muslims and/or Islam began to signify that which exists most outside the perceived boundaries of whiteness and Britishness (Abbas Citation2013; Morris Citation2020). In the wake of terrorist attacks in the U.S. and Europe, Islam was, and continues to be presented as the “limits” of acceptable multiculturalism (see Esposito and Kalin Citation2011). In Britain, Islamophobia exists across the political spectrum but is most famously associated with the populist, right-wing movement that hastened Brexit, especially the “Leave” campaign’s explicit reference to Turkish Muslim immigrants as a future threat to British (white) communities. The broader message, of course, was to remind every British Muslim citizen that many continue to believe they are “undeserving” of full and unqualified citizenship rights (IRR Citation2022). Inspired by Hall’s (Citation1986) pivotal work on Gramscian approaches to understanding racism, this article contributes towards a conjunctural understanding of race, racism and Islamophobia that emphasizes a historically specific, time and context-bound epistemology in understanding the experiences of British Turks and their engagements with Muslim identities, whiteness and Islamophobia. Based on the qualitative data presented here, we suggest Islamophobia is always experienced (and negotiated) by Turkish Muslims as a duality or in a double context; from within their country of family origin (Turkey) and from within their current country of residence (Britain). As such, we view Islamophobia not as a monolith, but as encountered (and responded to) in a variety of ways. Likewise, for our respondents, the meaning/s and implications of whiteness vis-a-vis Muslim identities and Islamophobia also arrive from two “directions”. Our approach, influenced by Hall (Citation1986), allows us to explore how contradictory social and political forces from Britain and Turkey condense in a historical conjuncture where in/compatibilities between racial identity and Muslim identity in the context of the “repertoires” of Islamophobia (Sayyid Citation2014) are posed as an ongoing problem for British Turkish citizens.

Central to our approach is the aim to address, conceptually and empirically, how sweeping generalizations about Islamophobia can overlook the differences between Muslims. A Muslim identity is never taken for granted and is always something “towards which one must make a stance; one cannot inhabit [a Muslim identity] in an unreflective manner” (Brubaker Citation2013, 5). Moreover, the term “Muslims” designates not a homogeneous and solidary group but a heterogeneous category (Brubaker Citation2013, 7). Many dominant political and cultural narratives and representations have pictured Muslims as undifferentiated and with no internal pluralism (Allen Citation2013, 69). Such notions also echo colonial rhetoric regarding the boundaries of “whiteness”. As such, Islamophobia in Britain is intricately tied to old and problematic ways of thinking about “who is white?” not only in terms of phenotype but also in relation to group differences, customs, and cultures (Meer and Modood Citation2012).

Our research exclusively focused on Turkish Muslims originating from (or with families originating from) mainland Turkey, particularly those with dual identities as Turkish and British. The research design sought to focus on Turks from mainland Turkey to ensure a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of their experiences and perspectives on racism, Islamophobia in particular, and to shed light on their internal distinctions, including their articulations of whiteness, Turkishness and Muslimness, thereby contributing to a more thorough understanding of this specific group. Our research thus aims to fill a gap in the existing literature by shedding light on the often-overlooked experiences of Turks from mainland Turkey, while also recognizing the need for and encouraging future research on the challenges that, for instance, Kdurds and AlevisFootnote3 from Turkey face in British society. This article may also be seen as an attempt to address what Garner and Selod (Citation2015, 10) refer to as “the relatively weak presence of fieldwork-based studies” in the study of Islamophobia, especially accounts which interview and prioritize the voices and experiences of Muslims.

The article is structured as follows. We begin by reviewing relevant literature on the topics of Islamophobia, whiteness and Turkish migrant identities in Britain. This is followed by a brief note on method before presenting and analysing qualitative data pertaining first, to British Turkish Muslims’ encounters with Islamophobia and their negotiations of these experiences or discursive realities about ideas around whiteness; and second, experience-based reflections upon enduring conflicts around Islam, secularism, modernity and whiteness in Turkish forms of Orientalism. We conclude by arguing that the experiences of British Muslim Turks are influenced by both Turkish Orientalism and the impacts of Anti-Muslim sentiments in Britain today, both of which impact how they make sense of their apparently contradictory position of being Turkish, British, Muslim and also, to varying degrees, white.

Islamophobia and Turkish identity in twenty-first-century Britain

Much existing literature on Islamophobia focuses on the racialization of British Muslims as non-white (Meer and Modood Citation2019; Modood Citation2010; Zempi and Awan Citation2019). Due to their “putative whiteness” British Turks pose a challenge to understandings of British Muslims in this manner and have therefore often been missing from such discussions. However, their relative “invisibility” as Muslims does not shield them from anxieties about Islamophobia. British Turks draw from distinctive understandings of whiteness that are both British and Turkish to offset or defy the impacts of Islamophobia and attempt to reconcile insecurities about their place in Britain. In this section, we will examine the literature pertaining to (i) Turkishness, whiteness and secularism; (ii) Turkish emigration to Britain and the religious/political identities and sensibilities that Turkish migrants exhibit; and (iii) Islamophobia in Britain in the twenty-first century.

Turkishness, whiteness and secularism

In the Turkish context, when the twentieth century arrived, the claim to whiteness emerged as a result of building selfhood around Turkish identity, modernity and cultural superiority (Yorukoglu Citation2017). Whiteness or rather white Turkishness played a foundational role in reinforcing the “Westernness” of Turkey during Kemalist reforms in the 1920s and 1230s (Kemalist pertains to the ideology of Mustafa Kemal, the founder of modern Turkey). The mantra of the “Turkish nation” taken on by the Kemalist Elite in the 1930s was “For the people, despite the people” (halk için, halka rağmen). The Kemalist perspective suggested that the ethnically diverse Anatolian masses were backward, primitive and vulnerable to the influence of Islam (Zeydanlıoğlu Citation2008). White European identity was integral to how secular Kemalist urbanites reimagined Turkey and a revised sense of Turkishness (Yorukoglu Citation2017); claims of whiteness were used to connect the new Turkish Republic with modernity and the West (Ergin Citation2008, 88). Consequently, Turkish Muslims found themselves associated with the non-white world, with savagery and unreason (Yardım and Easat-Daas Citation2018; El Zahed Citation2019). Turkish Orientalism has certain distinctions from what Edward Said (Citation1977) originally posited as European colonization and domination over the East (the Orient). Turkish Orientalism is directed towards Islamic elements embedded within Turkey itself; it is not only externally directed.

In the late Ottoman/ early republican era, Turkish Orientalism posited Ottoman Turkey and Islam as obstacles preventing Turkey from aligning with the West in its fullness (Çarmikli Citation2011, 8). Yet Turks, along with other people from the Middle East, retain a claim to being “Caucasian” and are often classified as “white” in the analysis of racial imagery (Yorukoglu Citation2017b). The Anthropological Research Centre of Turkey, founded in 1925Footnote4 in Istanbul, provided one of the earliest examples of deploying race science in the service of Turkish identity. This resulted in a large-scale cultural mobilization which actively constructed a “white, European Turkish identity”. Many Turks rejected, for example, Arabic, and Middle Eastern identities and were sometimes even hostile towards what became considered “Mediterranean” identities (Ergin Citation2016). The nation was a “battleground between a “white” European, modern Turkey and an Arab, Eastern, Muslim, and backward Turkey” (Ergin Citation2016, 106, emphasis added). The KemalistFootnote5 nationalist elite imagined Turkey stripped of its Ottoman past for its “backwardness” and “religiosity” (Zeydanlıoğlu Citation2008). Westernization was, for Kemalists, concerned with “reaching the contemporary level of civilisation” (muasır medeniyet seviyesine erişmek), a level equated with “de-Islamisation” (Göle Citation2015; Sayyid Citation2015, 68–69; Zeydanlıoğlu Citation2008). A century later, the secularizing, modernizing, Westernizing mission of Turkey continues to be a factor influencing British Turks’ understanding and adoption of white identities.

Turkish emigration to Britain

The post-World War II era witnessed a significant wave of Turkish migration, characterized by distinct patterns of movement and settlement. Economic opportunities and labour demands in Western Europe played a pivotal role in driving this migration, with Turkey becoming a prominent source of labour for countries such as West Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands (Cohen Citation1996). Turkish migrants occupied various occupational classes. For instance, Germany's “Gastarbeiter” program during the 1960s attracted more than a million Turkish labourers, resulting in the establishment of a substantial Turkish community in the country (King, Black, and Tyldesley Citation1998). Similarly, Belgium and the Netherlands also became destinations for Turkish migrants, who usually settled in urban and industrial areas (Lebas Citation2009).

In the United Kingdom, while Turkish migration did not attain the same magnitude as in European countries such as Germany, it has nonetheless left a significant impact on the post-WWII multicultural landscape, especially in London. A sizable number of Turkish migrants in the UK, around 250,000, settled in boroughs such as Hackney and Haringey, where vibrant Turkish communities continue to flourish today (Sirkeci and Espova Citation2013; Vertovec Citation2007).

Turkish immigrants that came to Britain in the late 1970s tended to be unskilled or semi-skilled workers, owing to the need for labour in the textile and food industries, both of which were domains of Turkish Cypriots (Atay Citation2010; Crul and Vermeulen Citation2006). The 1980 coup d’état in Turkey was a turning point in Turkish political affairs, and the military saw Leftist movements and communism as a threat against Kemalist secularism (Hemmati Citation2013). This resulted in another wave of Turkish immigration to the UK. As Enneli, Modood, and Bradley (Citation2005) explain, a significant proportion of immigrants from Turkey in the 1980s were secular-leaning and/or intellectuals, including students and many highly educated individuals.

While the latest Turkish election held in May 2023 is not evidence of the Turkish Diaspora in the UK as homogeneously sustaining the Orientalist legacy of Kemalism, a sizeable number of Turks (79.04 per cent) in the UK voted for Kilicdaroglu, the president of the centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP) established by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk himself. This suggests that the majority of Turkish immigrants’ political stance in the UK appears to be secular, republican and Kemalist. This contrasts with migrants who have settled elsewhere. For example, Turkish citizens in Germany voted for Erdoğan, who has been in power for over 20 years and whose power is sometimes argued to draw upon the anti-Western sentiments held by Turkish citizens isolated abroad and experiencing xenophobic (and Islamophobic) hostility (T-Vine Citation2023).

Islamophobia in twenty-first century Britain

As noted above, Muslims were discriminated against prior to 9/11 and 7/7, not least following the Rushdie affair of 1988, but there is no doubt these significant moments at the turn of the century led to an intensification of anti-Islam and anti-Muslim sentiments and practices (Allen Citation2004), as indeed did the 2017 Brexit referendum (Abbas Citation2020; Awan and Zempi Citation2020). Sayyid (Citation2014:, 14) argues that Islamophobia should be understood “through the range of its deployments, rather than through its purported essence or its constituent elements”. In Britain, Muslims and/or those perceived to be Muslim are subjected to a range of discriminatory attitudes and practices. These are a manifestation of long-term and short-term trends where Islamophobia, Orientalism, and the racialization of migrants to Britain intersect to construct Muslims generally as non-white, other, illiberal, and incompatible with British, European, and Western values (Rana Citation2017).

Babacan's work (Citation2021) contributes to the literature on Muslim citizens settling in Britain, particularly focusing on Turkish citizens. Babacan explores the role of media and policymakers in sustaining Islamophobia from the perspectives of its victims. The study deepens understanding of the racialization of Muslims and highlights covert forms of everyday Islamophobia. It also offers an original contribution by examining identity strategies developed by victims to cope with Islamophobia (Citation2021, 177–178). However, it does not explore the myriad of factors and lived experiences that mediate how British Turks deploy whiteness as a strategy, a racial identity that relates (differently) to both British and Turkish contexts.

Others have focused on the racialization of Muslims in the UK and the impact of Islamophobia on individuals with diverse racial backgrounds, including those who are naturalized citizens of the UK and, as such, the children or grandchildren of Muslim immigrants (young men of Pakistani and Bangladeshi origins in Birmingham) (Mac an Ghaill and Haywood Citation2015). Mac an Ghaill and Haywood’s (Citation2015) study contributes to the broader understanding of how young British-born Pakistani and Bangladeshi men navigate their identities and experiences in the face of Islamophobia and racialization in the UK. It sheds light on the complexities and challenges they encounter in defining their Muslim identities and highlights the need for a nuanced and context-sensitive approach to address the issues of discrimination and marginalization faced by these individuals. Such work helps to understand the experiences of Islamophobia amongst South Asian Muslims because of, amongst others, their colour, nationality, and cultural and religious practices as the most populated Muslim community in the UK (Abbas Citation2005; Allen Citation2013; Meer and Modood Citation2019). However, the literature pertaining to less populated and putatively “white” British Muslims, and Turks in particular, remains far less considered.

The existing literature on the racialization of British Muslims and Islamophobia has tended to be dominated by discussions of South Asian origin Muslims (Abbas Citation2005; Meer and Modood Citation2019), giving little attention to articulations of whiteness that exist or originate from (at least partially) outside of a Western context and which are used in negotiating with the Islamophobic tendencies of the UK. To advance our understanding of Islamophobia, it is imperative to move beyond a portrayal that focuses on a limited range of experiences and, using the examples of Turkish Muslims in Britain, acknowledge how their ambiguous relationship with whiteness is a significant factor in how their encounters with Islamophobia are negotiated. As outlined in the introduction, this approach enriches our comprehension of the multifaceted, time and context-bound nature of both whiteness and Islamophobia.

The working class have, at times, been both marginal and central to the symbolic formation of white Britishness (Bonnett Citation1998). During moments of populism, whiteness is strategically shared with the working class, but at other times, it retains its elite, colonial connotations. The “threat” of increased Muslim migration from Turkey was mobilized in the Brexit referendum of 2017, with the Leave campaign stoking fears that continued EU membership would lead to uncontrolled immigration into Britain and that potential Turkish membership of the EU–Turkey’s population of 75 million was often mentioned – would inevitably lead to an influx of Muslim migrants. Then Prime Minister David Cameron, who led the Conservative Party’s Remain campaign, did not deny that such an outcome would be unpalatable for the UK, preferring to stress that such a scenario was improbable because Turkey’s future membership of the EU was unlikely. Importantly, this showed that while anti-Turkish sentiment and Islamophobia may have been stronger on the Leave side of the campaign, it was not strongly countered by those favouring Remain. The important point for Abbas (Citation2020, 501) is how white working-class groups defined by the Right as the “left behind” are “instrumentalised in an attempt to support wider efforts to delimit the perceived problem of “Muslimness”, with Brexit as a device to help promote an exclusive ethnic “Englishness””. In this populist conjuncture, Britishness, Englishness and whiteness are counterposed with Islam. This racialization of Muslims as non-white is a form of cultural racism (as opposed to biological forms of racism) (Meer and Modood Citation2009), but it is also a strategy of making Muslims (or at least those who might be identified as Muslim) more visible by virtue of their constructed and then perceived “racial” difference.

Methodology

Thirty semi-structured interviews were conducted with British Turks living in England and Wales between the ages of 18 and 55 over a twelve-month period. Eighteen women and twelve men were interviewed; only one respondent (out of choice) did not hold British citizenship. The sampling strategies for this qualitative research were based on one criterion: self-identified “Turks” whose parents originate from mainland Turkey. Respondents of this research are all children of Turkish Muslim immigrants and have since retained Muslimness as their religious identity, independent of their levels of belief, sects, or practice of Islam. Aligned with that position, the term “British Turks” in this research refers to those who identify themselves as both Turkish and British, regardless of which identity outweighs the other. The idea of Turkishness has no reference to a hegemonic racial group (descent), dominant ethnicity (Turks or Kurds from Turkey) or religion (Islam). The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and each interviewee was given a pseudonym. The transcripts of the interviews were then submitted to inductive thematic analysis, which, by its nature, does not require predefined codes and anticipations of answers from the respondents (Braun and Clarke Citation2012; Ganji Citation2018). In terms of topics explored in the interviews, we covered Islamophobic rhetoric or actions from the perception of British Turks and how British Turks navigate and negotiate Islamophobia by looking at the aspects of their everyday life and the development of identities at the intersection of Westernness/Britishness and both Islamic and secular versions of Turkishness.

Shifting perceptions of whiteness: British Turkish Muslims and identity

Any conception of whiteness is necessarily intersectional, relating to location, class, gender, ethnicity and sexuality. The interview excerpts that we draw upon below are characterized by differentiated constructions of whiteness in a post 9-11, post 7/7 and post-Brexit British context. The below account brings attention to how the boundaries of whiteness are policed to racialise Turkish Muslims who do not fit the ideal of “Christian(ised, secular) whiteness” (Rexhepi Citation2022). Beste shared a personal experience that shed light on the perception of whiteness within her community:

Let me put it this way, for example, you know we ask parents to tick their ethnicity, and yeah, I am white. For example, my colleague who grew up here and lives here says, “Not your kind of white”; you know how we categorise ourselves as “white, Turkish-white” when she says white, it is not us white; she means like English white. She means not your type of white. Maybe she could categorise me as white if I did not wear a headscarf, and if I don’t know, I were a little bit blonder, let’s say. I don’t know if she would have thought the same. That is when it struck me, “Oh my god, they don’t even see us as white”. That was kind of an interesting turning point for me, and I think the way I was raised, for example, my mum always used to say whatever you do, however hard you try, you are Turkish. (Beste, 21 years old, Studying Biomedical Science, Leeds)

A necessary corollary of the sense of exclusion felt by Muslim Turks in Britain is to recognize and sometimes adopt a racial strategy to circumvent potential victimization. This is clearly illustrated in the following account by Begüm, one of our veiled Turkish respondents living in Leicester:

As Leicester is pretty much a multicultural city, the 7/7 and 9/11 attacks did not have so much impact on us here. 30% of my classmates were Muslim. Would the teacher have an attitude towards us? We were only children then! I was not veiled, and also, I am white; therefore, it was only while I was walking with my mum that would people outside knew that I was Muslim. (Begüm, 22 years old, Doing Masters in Computer Engineering, Leicester)

The relationality of whiteness is a feature of some interviews. In such cases, the right to whiteness is only available (or granted) to Turkish Muslims on occasions and in places where there is an absence of historically embedded European whiteness. Born and raised in London, Emre Can’s account contests the idea of whiteness as fixed or containing an authentic essence, emphasizing instead a shift in the meanings of whiteness even within the inner urban spaces of London:

If I am in central London, they may think I am not white British but a foreigner. Presumably, they might think of me as someone whose parents came as the first generation or were born into an Arabic or a Middle Eastern family. In contrast, if you ask me in South London, they would say, “He is one of us”, Yet in North London, they give me a dirty look to show their discontent with white people. (Emre Can, 18 years old, Working with Family, London)

Some Turks admit that their perceived whiteness helps them avoid the hostility and discrimination experienced by other Muslims in Britain. They argue that Turkishness as a cultural identity needs to be (and indeed can be) differentiated and distanced from people whom they, like white British non-Muslims, also perceive to be both non-white and Muslim. Accordingly, some respondents acknowledged the existence of racism directed at non-white people in Britain but spoke of being able to successfully align themselves with whiteness:

I am pretty white, so I would say I don’t get stereotyped. It [stereotyping] is supposedly very prevalent in racism, but I haven’t faced any of it so far … I think when it comes to English bias, the main problem is Pakistani and Indians, and then it depends on whom you ask because people are biased about it … I think skin colour makes it much easier to refrain from discrimination for sure. I feel like if someone is actively discriminating or trying to be racist, it is just because you are different, and they noticed it. (Ahmet, 28 years old, Application Engineer, Nottingham)

This section demonstrates the differences between what our respondents refer to as “Turkish-white” and “English-white” identities. The former, associated with visible signs of a Muslim identity such as a headscarf, denotes, in a British context, a not-quite-white identity, a sign of racial otherness – or at least this is how the situation is read by our respondents. “Turkish-white” remains, therefore, an ambiguous category, susceptible to being subsumed into more encompassing understandings of “Muslim”, but also which, in some contexts, offers the benefits associated with other white identities. Indeed, whiteness is shown to be available or is assumed by / imposed upon Muslim British Turks in an urban milieu characterized by a high concentration of black-identifying people. Other respondents, recognizing how Islamophobia in Britain is directed predominantly at racialised South Asian Muslims, acknowledge that the perceived relational whiteness of Turkish Muslims, in some contexts at least, enables them to avoid the discrimination suffered by other Muslims.

Whiteness in Turkish orientalism

As stated in the introduction, Turkish British Muslims encounter Islamophobia and ideas about the compatibility of white and Muslim identities not only in Britain where they live but also from Turkey – from history and familial experiences and opinions passed through generations, from Turkish public discourse and from old and new forms of media. As Brubaker (Citation2013, 4) puts it, “we live in a world in which Islam is a chronic object of discussion and debate”. As such, for Muslim British Turks, both the British and Turkish contexts are relevant in the lives of our respondents. For Muslim Turks living in Britain, Turkish Orientalism is an unavoidable thread in the fabric of their cultural identity. Turkish Orientalism provides a perspective on Turkey's modernization journey through the interplay of narratives about secularism, tradition and nationalism. This rich narrative, even when not in the political ascendency, is a core, lived contradiction that occupies the very centre of the idea of the Turkish nation, even for those living outside of Turkey itself (Vatin Citation2015).

Turkish Orientalism constructs its own “internal” Orient to serve its own desire to advance Turkey’s shift towards “Western civilisation”, with a reimagined sense of the ideal Turkish citizen as modern, white and secular. Such a view rests upon acknowledging Islam as the dividing line between the East and West (Szurek Citation2015, 113). Turkey has never been colonized, but the ideas of “whiteness” and “White Turkishness” adopted are nevertheless the product of socio-historical events and political context (Eldem Citation2010; Yorukoglu Citation2017). White Turkishness unsurprisingly reflects insecurities regarding Muslim otherness that has long resided at the centre of Western European supremacy and colonialism. From the early twentieth century, modernization was associated in Turkey with Westernization, which in turn was associated with an understanding that “whiteness” was a signifier of moral superiority.

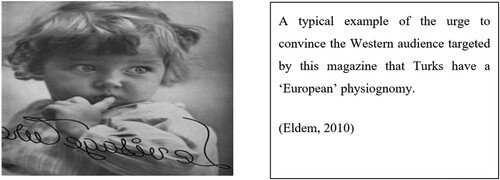

Turkey has undergone successive modernization programmes but can be largely attributed to the efforts of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who is understood to be the founder of modern Turkey. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Atatürk led a series of far-reaching reforms in the 1920s and 1930s aimed at transforming Turkey into a modern, secular, and Westernized nation. These reforms included the abolition of the caliphate, the adoption of a new legal system based on European models, the introduction of the Latin alphabet to replace the Arabic script, and secularizing the education system. Such a programme reveals that the ideal of a Western and white Turkey is more often than not equated with urban-dwelling Turks, and its implied European “success and superiority” is pitched against notions of Ottoman Turkishness (Eldem Citation2010, emphasis mine; Yorukoglu Citation2017). Turkish Orientalism portrayed the East (Ottoman Turkey and beyond), not only the diverse Muslim ethnicities inherited from the Ottoman Empire but its own Anatolian masses, as irrational and ignorant (Çarmikli Citation2011). As a result, Turkish Orientalism developed and continues to have an enduring influence on how Turkish society and especially its secular elites view themselves today ( and ).

Oxymoronic as it may sound, Turkish/Ottoman Orientalism has a very strong logic. From the moment Ottoman elites decided that Westernization was the only (or most efficient) way to catch up with Western material success (a phenomenon that dates back to the early nineteenth century and gained momentum after the TanzimatFootnote6 Decree of 1839), they had implicitly agreed to one of the most basic tenets of Orientalism: that the East was essentially different from the West, and that it was essentially stagnant and lacked the capacity to change (Çarmikli Citation2011, 27). Therefore, Turkish Orientalism still informs much of how British Turks (including our respondents) view themselves and the world around them. As Harun explains below, Turkey is “a different sort of Muslim country”. Harun refers to Turks’ whiteness and privileged social positioning in comparison with other Muslims, providing evidence that the Turkish oriental vision is being maintained even by Muslim descendants of first-generation Turkish migrants in Europe:

In my opinion, Turks are relatively lucky compared to other Muslims. Our motherland is modernised, [Turkey is a] different sort of Muslim country compared to somewhere like Arabic countries, Arabic friends might feel more discriminated against. Nevertheless, I know very well that if we were to look more Muslim, it would be just as bad for us too. We are white in the end; our skin tone is right on the lucky side, very interesting, and our eyes are not slanted. People from the Caribbean, for instance, give off a particular smell; they cook well, so that smell of spices permeates all over them. We don’t show any quality revealing our nationality.

For many respondents, the elision of whiteness with Westernness is also an attempt to fortify themselves in the enclaves of privilege rooted in white Britishness (Binnie, Holloway, and Millington Citation2006). Orton et al. (Citation2022) note that people who acknowledge the structures of exclusion sometimes attempt to use complicity as a part of their resistance. Harun’s resistance to accepting Turkey as a “normal” Muslim country and that the potential exists for Turks to become racialised into the homogenized Muslim subject is evident in how he perpetuates the ideology of inferiority against people and countries who are perceived as Muslim.

Gülkız (below) similarly engages in the tendency to portray herself as more British and whiter than other Muslims, although, echoing Brubaker’s (Citation2013) point that self-identification and other-identification are interdependent, she only reflects on this tendency following her friend’s observations:

I have a Turkish friend who lived in Turkey and came here to study at university; when she came to my house where I was relaxed, maybe, I don’t know, and she was like, “Oh my god, you are just like a British Turkish person”, and I did not understand what she was saying, I don’t know if I used the word “relaxed” I think it might have just been my approach of relaxed. She was just like, “Oh, I’ve got a Turkish friend but who is very British”. I don’t know if it was just my actions or talked the way I was. I mean, I know, like, for example, I love my white tea; I drink tea with milk. I’ve got a friend who is Iranian, and whenever she comes, she is like, “Oh my god, you are so white”.

Ayşe’s remarks (below) recount her Islamophobic experience in Turkey. She reveals the Orientalist antagonism against Islam and “visible” Muslims in contemporary Turkey. Such encounters necessarily condition our respondents’ negotiations with white and /or secular identities alongside their experiences in Britain:

I was on holiday at the time in Ayvalik/Turkey. It was after the coup attempt.Footnote7 I had to buy a sim card for my phone and went to a local mobile shop in the area. I was in the shop speaking to the salesperson about my purchase when an elderly woman walked in the shop and started speaking loudly and saying “What is this now? Look at this, as if it’s okay the people with beards and robes are walking on the streets and shouting Allahuekber! It’s disturbing to see this”. I was very offended by her speech as I felt her animosity towards me as I covered my hair and dressed modestly. She vindicated me and tried to radicalise me in front of others. I told her that I’m proud to be a Muslim. Those people who shouted Allahuekber were the ones who risked their lives on the night of the coup attempt, and she should not be scared of them. I told her I lived abroad in the UK and that I studied there and am a solicitor. I was raised with religious values and that we can practise our faith without being judged by others.

In this context, with the increasing normalization of racist and Islamophobic discourses in British politics, and dealing with their entrenched insecurities about their place in the Western world, some British Turks’ claim to whiteness take the form of racial privilege (Yorukoglu Citation2017). To this extent, whiteness as a cultural identity is distinguished and enacted amongst some British Turks to serve one’s benefit. Consequently, as Barker (Citation2002) argues, these young people shift from one subject position to another as they determine it to be situationally appropriate.

This section reveals how Turkish Orientalism, a historical development born from Turkey’s strained relationship with “the West”, forms an important part of how Muslim British Turks make sense of their encounters with Islamophobia and their negotiations with whiteness. Modern Turkey, in the enduring Kemalist tradition, is viewed as secular and white, as opposed to Muslim and Eastern in nature. Islam and Muslim identities are understood as traditional and irrational, as barriers to successful Westernization. Our Turkish respondents reference these notions of Turkishness, even when they are Muslims themselves. They more closely align themselves with notions of “English-white” than many of their non-Turkish Muslim counterparts. Turkish Orientalism, even if not embraced fully, permits respondents to claim Turkey is “a different kind of Muslim country”, acknowledging also that Turkey’s whiteness – a notion central to Turkish Orientalism – has a “lucky side”. Ayşe's encounter in Ayvalik vividly illustrates the inherent challenges confronted by visibly Muslim women within a societal framework where symbols of Islam are often deemed problematic. In a response to Islamophobic remarks, Ayşe strategically defends her identity by emphasizing her professional life as a solicitor in the UK, thereby interrogating the inferiorised position of Muslim women in the Turkish context. This section, therefore, underlines the pervasive influence of Turkish Orientalism on the nuanced perceptions of Islam and identity among Muslim British Turks, intricately shaping their ongoing negotiation with whiteness and profoundly influencing their encounters with Islamophobia, not solely within the British milieu but also within the predominant Muslim societal landscape of Turkey.

Conclusion

It may be more apt to speak of “Islamophobias” rather than of a single phenomenon. (Sajid Citation2005, 2)

British Turks with strong Islamic identities that acknowledge the “outsider” status of Muslim migrants do not unquestionably classify themselves as “white” and “European” and identify themselves with religio-ethnic categories within the cultural and moral boundaries of Turkishness thereby embracing (or at least accepting) the ambiguities of “Turkish-whiteness”, while other respondents hold on to their putative whiteness as integral to their cultural identity. This dynamic, as discussed by Hall (Citation1986) in his discussion of Gramsci’s relevance for the understanding of racism, underscores the importance of historical and cultural context in shaping identities. The experiences of British Turks in both Turkish and British societies are influenced by both early twentieth-century Turkish Orientalism and the impacts of Anti-Muslim sentiments in Britain today, both of which impact their understanding of whiteness, Britishness, Turkishness and being a Muslim.

Whiteness appears to offer Turkish Muslims the possibility of phenotypical and cultural inclusion in mainstream British society, even if they might disagree with or oppose the racist premises of such an arrangement. The diverse narratives of British Turks reveal changing configurations of “whiteness”, as asynchronously and variably used in Britain and Turkey, implicating a self-affirming power that casts out Muslims as non-white and non-Western. Even if this comes from different political directions, the racialization of Muslims as non-white is a continuity between British and Turkish variants of Islamophobia. Incorporating Hall's (Citation1986) theoretical insights into the analysis of British Turks’ identification or contestation of whiteness, therefore, allows for a deeper understanding of various ways British Turks negotiate their identities, resist power dynamics, and navigate the complexities of race, ethnicity, and belonging within the context of Islamophobia in today’s Britain. We contend that such a contextually specific and conjunctural understanding of Islamophobia, in relation to whiteness and national identities; and that at the same time contributes to recognizing difference among Muslims is vitally important. Examining the historically marginalized position of Islam in the Turkish context, along with the first-hand experiences and interactions of British Turks within mainstream British society, sheds light on how Islamophobia and the racialization of Muslims as non-whites influence British Turks’ perception of whiteness.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University of York's ELMPS Ethics Committee on October 19, 2019.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 In 1923 Turkey was declared a republic.

2 Justice and Development Party (AKP), a Turkish political party formed in 2001 that challenged Kemalist politicians and parties. The party is led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan who has been in power for more than 20 years.

3 Alevi is a mystical belief that is rooted in Islam and Sufism with some traditions of Christianity and Shamanism. That being said, some segments of the Alevi community argue that features of their belief and culture do not follow Islamic or other religious code strictly. For simplicity’s sake, we do not delve into further detail about atheist Alevis and Alevis who oppose Islamic religiosity but adhere to Turkish nationalism (Dudek Citation2017). Retrieved from Akdemir (Citation2016).

4 Two years after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey.

5 The process of the reproduction of Orientalism within Turkey refers to the way in which the Kemalists imagined the Turkish nation and construed the ethno-religiously diverse society inherited from the Ottoman Empire. Kemalists took on what Zeydanlıoğlu (Citation2008) calls the “White Turkish Man’s Burden” in order to carry out a civilising mission on a supposedly backward and traditional Anatolian society enslaved by Islam.

6 Means reorganisation.

7 Turkey witnessed the bloodiest coup attempt in its modern history on July 15, 2016, when a faction of the Turkish military launched a coordinated attempt to topple President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan used state-employed imams to rally citizens to denounce the attempted coup on July 15, meaning that visibly Muslim Turks were particularly active during the process, hence the verbal attack against Ayse in the aftermath of the 2016 coup attempt. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/7/15/turkeys-failed-coup-attempt-explainer

References

- Abbas, T. 2005. Muslim Britain: Communities Under Pressure. London: Zed books.

- Abbas, T. 2013. “‘After 7/7’: Challenging the Dominant Hegemony.” In Muslim Spaces of Hope: Geographies of Possibility in Britain and the West, 135. Bloomsbury.

- Abbas, T. 2020. “Islamophobia as Racialised Biopolitics in the United Kingdom.” Philosophy and Social Criticism 46 (5): 497–511.

- Akdemir, A. 2016. “Alevis in Britain: Emerging Identities in a Transnational Social Space.” PhD. Thesis, University of Essex.

- Allen, C. 2004. “Justifying Islamophobia: A Post-9/11 Consideration of the European Union and British Contexts.” American Journal of Islam and Society 21 (3): 1–25.

- Allen, C. 2013. Islamophobia. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Aslan, A. 2018. “The Politics of Islamophobia.” In Islamophobia in Muslim Majority Societies, 71–92. Oxon: Routledge.

- Atay, T. 2010. “Ethnicity Within Ethnicity’ among the Turkish-Speaking Immigrants in London.” Insight Turkey 12 (1): 123–138.

- Awan, I., and I. Zempi. 2020. “‘You All Look the Same’: Non-Muslim Men Who Suffer Islamophobic Hate Crime in the Post-Brexit Era.” European Journal of Criminology 17 (5): 585–602.

- Babacan, M. 2021. “Young Turks in Britain and Islamophobia: Perceptions, experiences and identity strategies.” PhD diss., Bristol University. https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/316057851/Final_Copy_2022_03_22_Babacan_Muhammed_PhD_.pdf.

- Barker, C. 2002. Making Sense of Cultural Studies: Central Problems and Critical Debates. London: Sage.

- Binnie, J., J. Holloway, and S. Millington. 2006. “Introduction: Grounding Cosmopolitan Urbanism: Approaches, Practices and Policies.” In Cosmopolitan Urbanism, 13–46. London: Routledge.

- Bois, W. E. B. D. 1897. Surviving of the Negro People. New York: The Atlantic.

- Bonnett, A. 1998. “How the British Working Class Became White: The Symbolic (Re)Formation of Racialized Capitalism.” Journal of Historical Sociology 11 (3): 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6443.00066.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. Thematic Analysis. American Psychological Association.

- Brubaker, R. 2013. “Categories of Analysis and Categories of Practice: A Note on the Study of Muslims in European Countries of Immigration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (1): 1–8.

- Çarmikli, E. S. 2011. “Caught between Islam and the West: Secularism in the Kemalist Discourse.”

- Cohen, R. 1996. The Cambridge Survey of World Migration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Crul, M., and H. Vermeulen. 2006. “Immigration, Education, and the Turkish Second Generation in Five European Nations: A Comparative Study.” In Immigration and the Transformation of Europe, edited by C. A. Parsons and T. M. Smeeding, 235–250. Cambridge University Press.

- Dudek, A. 2017. “Religious Diversity and the Alevi Struggle for Equality in Turkey.” Forbes, February 10.

- Eldem, E. 2010. “Ottoman and Turkish Orientalism.” Architectural Design 80 (1): 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1006

- El Zahed, S. Y. 2019. “Internalized Islamophobia: The Discursive Construction of “Islam” and “Observant Muslims” in the Egyptian Public Discourse.” PhD diss., UCLA.

- Enneli, P., T. Modood, and H. K. Bradley. 2005. Young Turks and Kurds: A Set of Invisible Disadvantaged Groups. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Ergin, M. 2008. “‘Is the Turk a White Man?’ Towards a Theoretical Framework for Race in the Making of Turkishness.” Middle Eastern Studies 44 (6): 827–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263200802425973

- Ergin, M. 2016. “Is the Turk a White Man?”: Race and Modernity in the Making of Turkish Identity. Brill.

- Esposito, J. L., and I. Kalin, eds. 2011. Islamophobia: The Challenge of Pluralism in the 21st Century. USA: OUP.

- Ganji, F. 2018. “Everyday Interculturalism in Urban Public Open Spaces: A Socio-Spatial Inquiry in Bradford City.”

- Garner, S. 2007. Whiteness: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Garner, S. 2012. “A Moral Economy of Whiteness: Behaviours, Belonging and Britishness.” Ethnicities 12 (4): 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812448022

- Garner, S., and S. Selod. 2015. “The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia.” Critical Sociology 41 (1): 9–19.

- Gilroy, P. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Harvard University Press.

- Göle, N. 2015. Islam and Secularity: The Future of Europe's Public Sphere. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hall, S. 1986. “Gramsci's Relevance for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10 (2): 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/019685998601000202

- Hall, S. 2021. Selected Writings on Race and Difference. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hemmati, K. 2013. “Turkey Post 1980 Coup D’etat: The Rise, the Fall, and the Emergence of Political Islam.” Illumine: Journal of the Centre for Studies in Religion and Society 12 (1): 58–73.

- Institution of Race Relations (IRR). 2022. Citizenship: From Right to Privilege. https://irr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Deprivation-of-citizenship-Final-LR.pdf.

- King, R., R. Black, and M. Tyldesley. 1998. “The International Migration Turnaround in Southern Europe.” Geographical Journal 164 (3): 243–256.

- Lebas, E. 2009. “Gender and Migration: West Indians in Comparative Perspective.” International Migration 47 (1): 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00480.x

- Mac an Ghaill, M., and C. Haywood. 2015. “British-Born Pakistani and Bangladeshi Young men: Exploring Unstable Concepts of Muslim, Islamophobia and Racialization.” Critical Sociology 41 (1): 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920513518947

- Mardin, Ş. 1973. “Center-Periphery Relations: A Key to Turkish Politics?” Daedalus 102 (1): 169–190.

- Meer, N., and T. Modood. 2009. “The Multicultural State We’re In: Muslims, ‘multiculture’ and the ’Civic Re-balancing’ of British Multiculturalism.” Political Studies 57 (3): 473–497.

- Meer, N., and T. Modood. 2012. “For “Jewish” Read “Muslim”? Islamophobia as a Form of Racialisation of Ethno-Religious Groups in Britain Today.” Islamophobia Studies Journal 1 (1): 34–53.

- Meer, N., and T. Modood. 2019. “Islamophobia as the Racialisation of Muslims.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Islamophobia, edited by I. Zempi and I. Awan, 18–31. London: Routledge.

- Modood, T. 2010. “Still not Easy Being British: Struggles for a Multicultural Citizenship.” Islamophobia and Anti-Muslim 127: iv–160.

- Morris, Carl. 2020. “The Rise of a Muslim Middle Class in Britain: Ethnicity, Music and the Performance of Muslimness.” Ethnicities 20 (3): 628–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796818822541

- Orton, L., O. Fuseini, A. Kóczé, M. Rövid, and S. Salway. 2022. “Researching the Health and Social Inequalities Experienced by European Roma Populations: Complicity, Oppression and Resistance.” Sociology of Health and Illness 44: 73–89.

- Pak, S. 2004. “Cultural Politics and Vocational Religious Education: The Case of Turkey.” Comparative Education 40 (3): 321–341.

- Rana, J. 2017. Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire. California: University of California Press.

- Rexhepi, P. 2022. White Enclosures: Racial Capitalism and Coloniality Along the Balkan Route. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Runnymede Trust. 1997. Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All. London: The Runnymede Trust.

- Said, E. W. 1977. “Orientalism.” The Georgia Review 31 (1): 162–206.

- Sajid, A. 2005. “Islamophobia: A New Word for an old Fear.” Paper Presented at the OSCE Conference on Anti-Semitism and on Other Forms of Intolerance, Cordoba, 8–9 June 2005.

- Sayyid, S. 2014. “A Measure of Islamophobia.” Islamophobia Studies Journal 2 (1): 10–25. https://doi.org/10.13169/islastudj.2.1.0010

- Sayyid, S. 2015. A Fundamental Fear: Eurocentrism and the Emergence of Islamism. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sirkeci, I., and N. Esipova. 2013. “Turkish Migration in Europe and Desire to Migrate to and from Turkey.” Border Crossing 3 (1-2): 1–13.

- Szurek, E. 2015. ““Go West”: Variations on Kemalist Orientalism.” In After Orientalism, 103–120. Brill.

- T-Vine. 2023. “Turkiye Elections 2023: How Overseas Turks Voted in the First Round of the Presidential Race.” https://www.t-vine.com/turkiye-elections-2023-how-overseas-turks-voted-in-the-first-round-of-the-presidential-race/.

- Vatin, J.-C. 2015. “After Orientalism: Returning the Orient to the Orientals.” In After Orientalism, 272–277. Leiden: Brill.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-Diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

- Watt, P. 2021. Estate Regeneration and Its Discontents: Public Housing, Place and Inequality in London. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Yardım, M., and A. Easat-Daas. 2018. “Islamophobia in Satirical Magazines: A Comparative Case Study of Penguen in Turkey and Charlie Hebdo in France.” In Islamophobia in Muslim Majority Societies, 93–106. Routledge.

- Yegenoglu, M. 2012. Islam, Migrancy, and Hospitality in Europe. New York: Springer.

- Yorukoglu, I. 2017. “Whiteness as an Act of Belonging: White Turk’s Phenomenon in the Post 9/11 World.” Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation 2: 1–22.

- Zempi, I., and I. Awan. 2019. The Routledge International Handbook of Islamophobia. Oxon: Routledge.

- Zeydanlıoğlu, W. 2008. “The White Turkish Man’s Burden: Orientalism, Kemalism and the Kurds in Turkey.” Neo-colonial Mentalities in Contemporary Europe 4 (2): 155–174.

![Figure 1. “#La visage turc” [Turkish faces] from La Turquie Kamaliste, 19, 1937.](/cms/asset/65322e7c-af12-4f4e-ae4f-eae6019350c3/rers_a_2317955_f0001_oc.jpg)