ABSTRACT

This article explores how older White Dutch people produce reflexivity on race and racism in the context of the public controversy around the “Zwarte Piet” (black Pete) tradition. Reflexivity refers to a conscious effort to become aware of and address one’s unconscious biases. Fourteen semi-structured in-depth interviews with older Dutch White individuals (65+) from (suburbs of) big to medium-sized cities located in the Netherlands were qualitatively analyzed with a combination of thematic and critical discourse analysis. We found that participants reflexively engaged with race and racism within three discursive contexts: (1) generational (dis)connectedness, (2) ever-evolving public discourses, and (3) identity (re)considerations. Across these contexts, the production of reflexivity entails rapid shifting from openings for critical reflection to epistemological and ontological anxieties. We show how the avoidance strategies offered by hegemonic Whiteness discourses offer comfort and perceived escape routes from such anxieties, while also creating new uncertainties for our participants.

Introduction

In early December, children around the Netherlands expect Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) and his helpers to deliver them presents. Over the past decades, this tradition has become increasingly controversial because Sinterklaas’ helpers, known as “Zwarte Pieten” (black Petes) (ZP), are offensive representations of BlacknessFootnote1 (i.e. black face paint, curly black hair, golden earrings, exaggerated lips, and colorful outfits). Yet, understandings of race and racismFootnote2 in the Netherlands remain a site of discursive struggle as both public and personal discourses deflect accusations of racism (Chauvin, Coenders, and Koren Citation2018; Essed Citation1991; Van Dijk Citation1992; Wekker Citation2016). Amid this discursive struggle, ZP has become a contested yet powerful symbol: a joyful family tradition and expression of Dutch identity for some; a reminder of systemic and everyday forms of racism for others (Balkenhol Citation2016; Chauvin, Coenders, and Koren Citation2018; Essed Citation1991; Euwijk and Rensen Citation2017; Hilhorst and Hermes Citation2016; Rodenberg and Wagenaar Citation2016; Wekker Citation2016). In recent years, these controversies have prompted a re-evaluation of the tradition, with older people (who long seemed hesitant to embrace the proposed adaptations) showing the most recent change in opinion (I&O Research Citation2020).

In this paper, we approach the ZP debate as an opportunity to empirically engage with the reflexive transformation of tradition in modernity (Beck 2003, as cited by Rossi Citation2014; Giddens Citation1991). Where previous studies have focused on the micro-dynamics of racial categorization, stereotyping, and the influence of Whiteness on understandings of racism (e.g. Bonilla-Silva Citation2015; Hughey Citation2022; Ortiz Citation2021; van Sterkenburg, Peeters, and van Amsterdam Citation2019), we ask how reflexivity around race and racism is produced and resisted among groups that have enjoyed a racial privilege throughout their lives, with a focus on older White Dutch people. Despite having experienced significant transformations in hegemonic discourses around race and racism throughout their lives, this age group is seldom studied empirically in relation to reflexivity in a postcolonial context.

We understand reflexivity as a process of conscious engagement with one’s (taken-for-granted) views and biases amid the modern transformation of local traditions and identities (such as national, generational, and racial) (Giddens Citation1991, Citation1993). Although tradition provides a sense of continuity and security, its renewal across generations – as exemplified by the growing number of people advocating for changing ZP – is accompanied by change and, as such, remains a reflexive process (Giddens Citation1991; Citation1993; I&O Research Citation2020).

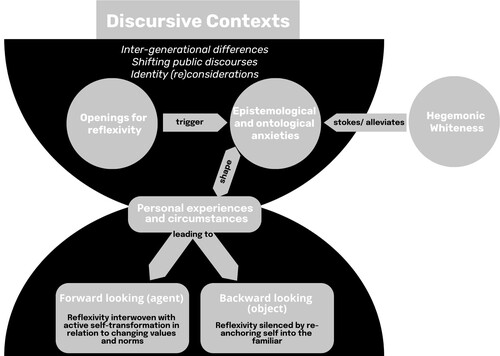

Informed by a critical Whiteness framework (Bonilla-Silva Citation2015; Citation2018; DiAngelo Citation2018; Lewis Citation2004; van den Broek Citation2020; Wekker Citation2016), we qualitatively analyze fourteen in-depth interviews with White Dutch individuals (65+), identifying three discursive contexts within which reflexivity was produced: (1) generational (dis)connectedness, (2) ever-evolving public discourses mediated by mass media representations of ZP and activist efforts to challenge hegemonic narratives, and (3) identity (re)considerations. These discursive contexts are analytical distinctions that remain intertwined in everyday communication. Shaped by public debates and personal experiences, each context offers openings for reflexivity that trigger epistemological and ontological anxieties. Simultaneously, hegemonic Whiteness offers strategies of avoidance, providing a perceived escape from these uncertainties while also perpetuating them.

Zwarte Piet: an ongoing controversy

Throughout history, Dutch collective memory left little room for Black experiences (Balkenhol Citation2016). When the Netherlands abolished slavery in 1863, enslavers were compensated by the state for their “loss” of income, while the formerly enslaved were forced to continue working for them for ten more years (Nationaal Archief Citationn.d.). Discursively, the formerly enslaved became depicted as incapable of handling freedom – a narrative that evolved into the paternalistic “Dutch burden” view, arguing that White Dutch people must “‘help’ Blacks cope with ‘modern’ Dutch society” (Essed Citation1991, 16). This narrative enabled the White Dutch to re-legitimize perceived hierarchical differences by claiming a compassionate upper moral ground and framing Black people as helpless victims (Balkenhol Citation2016; Krumer-Nevo and Benjamin Citation2010). Furthermore, as Black people lagged economically in the Netherlands, a narrative of the “pampered” minority unable to adapt to Dutch society emerged throughout the 1980s (Essed Citation1991). Simultaneously, Dutch political culture has celebrated pluralism and made tolerance a national trait while avoiding engagement with the country’s colonial legacy (Van der Pijl and Goulordava Citation2014; Wekker Citation2016).

These dynamics have complicated the public recognition of systemic racism in the Netherlands, shaping the public discussion of ZP (Essed Citation1991; Helsloot Citation2012). Traditionally, ZP has been visually depicted through racialized facial features; the character has been performed using blackface (using face paint to impersonate a Black character). Anti-ZP activism has called attention to the links between such practices and slavery, connecting ZP to the colonial legacy of the Netherlands (Balkenhol Citation2016; Koning Citation2018; Krumer-Nevo and Benjamin Citation2010). Yet, the absence of a public debate about this colonial legacy has also facilitated the delegitimization of anti-ZP activist efforts, which were blamed for not being able to let go of the past and thus “creating” controversies (Chauvin, Coenders, and Koren Citation2018). For a long time, such hegemonic denials of racism closed off the possibility for critical reflection on (the grotesque racialization of) ZP within the mainstream public debate (Van der Pijl and Goulordava Citation2014).

The 2011 extensive media coverage of the arrest of anti-ZP activists at the national Sinterklaas parade, however, spurred a nationwide public debate on the racism underpinning this tradition (Euwijk and Rensen Citation2017; Nederland wordt beter Citationn.d.). Media narratives about Dutch slavery also took a turn in 2013, when “[t]he narrative transitioned from an abolitionist memorial regime, telling only of the end of slavery, to a victimary regime that allowed for more open discussion on the realities and lasting consequences of slavery” (Vliet Citation2022, 784). Finally, the global Black Lives Matter movement strengthened the legitimacy of the request for public reflection on the consequences of the Netherlands’ colonial past. This fostered the search for alternatives to ZP – such as “soot wipe Pete” – but also the rise of counter-initiatives – such as the Facebook page “Pietitie” (Pete-ition) calling for Pete to remain black (van Amstel Citation2013). Such counter-initiatives re-appropriate hegemonic denials of racism, depicting anti-ZP activists as ungrateful and shifting the focus of the debate from the racism underpinning ZP to unrelated social issues, such as economic woes and declining living standards (Hilhorst and Hermes Citation2016; Vliet Citation2019).

Reflexivity and race: a theoretical approach

How do such public debates shape critical reflections on race and racism at the individual level? Such a question is even more pertinent in the context of consuming such debates through the news, as this can lead to “non-reflexive viewer consciousness”, discouraging viewers from recognizing their role in social change (Dahlgren Citation1981, 104). Reflexivity refers to a cognitive disposition toward critical questioning of ingrained ideas and behaviors (Giddens Citation1991). Such dispositions are important, as they may lead to transformative learning, where individuals adjust their behavior through reflection on their own views and beliefs (Giddens Citation1991; Kluttz, Walker, and Walter Citation2020; Mezirow Citation2000). Reflexivity, however, is neither a constant process nor an all-encompassing aspect of our lives. It is often personal and non-linear, as questioning deeply seated worldviews can trigger ontological and epistemological anxieties (Billig Citation1988; Giddens Citation1991; Mezirow Citation2000; Owens, Robinson, and Smith-Lovin Citation2010; Rafieian and Davis Citation2016; Rossi Citation2014).

The tension between reflexivity and hegemonic discourses is particularly relevant to race and racism. In the Netherlands, Whiteness remains the invisible status quo against which “difference” is constructed and, thus, the dominant lens through which lingering colonial narratives are approached and made sense of (Balkenhol Citation2016; Essed and Trienekens Citation2008; van den Broek Citation2020; Wekker Citation2016). Challenges to Whiteness are often resisted through the deployment of various avoidance and denial strategies such as the culturalization of race, the relegation of racism to working-class strata, or the framing of racism as an outdated topic (Çankaya and Mepschen Citation2019; Essed and Trienekens Citation2008; Van der Pijl and Goulordava Citation2014). As with other parts of Europe, still marked by the memory of the Holocaust as the one “true” example of racism on the European continent, accusations of racism are seen as “un-Dutch” and thus reserved for criticizing extreme-right politics (Chauvin, Coenders, and Koren Citation2018; Goldberg Citation2006; Lentin Citation2018, Citation2020; Siebers Citation2017). This also helps explain why antiracism activists can be easily demonized for “not ‘getting over’ past oppression [and therefore] responsible for their own exclusion from the postracial nation” (Howard 2018, as cited by Chauvin, Coenders, and Koren Citation2018, 513). Furthermore, the Dutch attitude of “smug ignorance”, which brings together the idea of tolerance as a national feature with the belief that race and racism are outdated topics, makes engagement with the historical context and, by extension, with the issues brought up by anti-ZP activism, difficult (Essed and Hoving 2014, as cited by Van der Pijl and Goulordava Citation2014, 265). This facilitates the counter-framing of ZP as “not racism” (Lentin Citation2018, 401), as a symbol of “all ways in which ‘the Dutch’ suffer” (Hilhorst and Hermes Citation2016, 227), and as a form of “reverse racism” allegedly marginalizing White Dutch people in “their own” country (Hughey Citation2010, 1303; Twine and Gallagher Citation2008). Such counter-framing efforts speak to a wider “White fragility” narrative portraying White identity as victimized and often drawing from other racist tropes such as race-neutrality or color-blindness to downplay racism and overemphasize personal agency as an explanation for systemic inequalities (Bonilla-Silva Citation2018; DiAngelo Citation2018, 2; Golash-Boza Citation2016).

Reflexivity thus remains a site of ideological struggle where opposing agendas rhetorically pull and push public opinion in different directions on the question of race and racism (Emirbayer and Desmond Citation2012; Giddens Citation1991; Kluttz, Walker, and Walter Citation2020; Mezirow Citation2000; Riach Citation2009). For Helsloot (Citation2012), the failure of White Dutch people to recognize the racism underpinning ZP represents a form of “cultural aphasia”, where the ritual of tradition and its embodied experiences at the level of individuals partaking in it have led to acquiring new “‘operational’ meanings” associated with ZP that are disconnected from ZP’s racist colonial heritage (11). This process – akin to the inability to link thoughts to the right words which is common in aphasia – can lead to angry reactions to the charge that ZP is racist. At the individual level, however, such cultural aphasia and hegemonic Whiteness intersect with other social categorizations like gender and age. Opening towards reflexive (self-)questioning thus becomes intertwined with both personal experiences and hegemonic race and racism discourses (Emirbayer and Desmond Citation2012; Fillieule Citation2013; Fisher, Wauthier, and Gajjala Citation2020; Golash-Boza Citation2016; McCluney et al. Citation2020; Smaje Citation1997). This paper explores this intertwining by focusing on the production of reflexivity on race and racism in the context of both individual experiences and broader discourses.

Research design

To explore the production of reflexivity on race and racism in the context of the ZP-debate, this paper relies on 14 in-depth interviews with self-identified White 65+-year-old Dutch individuals. Under-represented in studies of everyday racism, this age group can be seen as a symbolic link to tradition and, generally, more attuned to past than current political discourses (Bartels and Jackman Citation2014; Mannheim Citation1952). In line with Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (Citation2006) findings, the relative homogeneity of the sample in terms of race, age, and urban residence, provided saturation across the 14 interviews, as evidenced through recurring codes which informed the themes described next. The first author coded the data and the results were discussed with the second author who also functioned as the supervisor for this project.

The first author conducted the interviews face-to-face at the participants’ location of choice (average length: 60 minutes) (). All interviews were conducted, transcribed, and analyzed in Dutch. Quotes were translated for the final report. Since we anticipated that personal encounters with ethnocultural and racial diversity shape one’s position on the ZP-debate, participants had to have lived in (or close to) a large city and to self-identify as familiar with the ZP-debate and arguments. Recruitment involved personal networks and reaching out to participants in places where they were likely to be found, such as a care facility in Amsterdam and an exam invigilation in Rotterdam.

Table 1. List of participants.

In line with active interviewing principles and to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon investigated, we focused on real-time reflexivity during the interview and on the accounts of transformations of personal views throughout one’s lifetime (Perera Citation2020; Riach Citation2009). Interviews were voice-recorded, transcribed, and de-identified by assigning pseudonyms to participants and replacing specific places of residence with generic terms such as “medium city in Randstad area” (30.000–70.000 inhabitants) or suburb of Rotterdam (<30.000 inhabitants) (CBS Citationn.d.). Along with the interview notes, the transcripts formed the data for the analysis.

Given the focus on individual experiences and views, rapport was a vital component of the interview process. To minimize sensitive and confrontational questions, the sequence of topics started with personal recollections and ended with participants’ views of the ZP-debate and activism. We never directly asked participants about their thoughts on race, opting instead for more neutral questions such as “What do you think about how the media covered the anti-ZP activism?”. However, because the production of reflexivity can sometimes be difficult to identify (as instances of critical self-awareness might not be immediately obvious to an interlocutor), the interviewer also triggered moments of reflexivity by bringing up opposing arguments or participants’ (contradictory) earlier statements (Kvale Citation2007; Perera Citation2020; Riach Citation2009).

Transcripts were analyzed by combining thematic analysis (TA) with critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Machin and Mayr Citation2012). Using Atlas.ti for coding, we first worked in an inductive-deductive manner to identify the main discourses on race and racism that participants drew from. Taking advantage of the method’s iterative nature, the inductive coding started immediately after the first interview with codes such as “celebrations as normal”, “shield children from debate”, or “colonialism not discussed back then”. Deductive codes, on the other hand, were informed by the theoretical framework; for example, “(struggles of) reflexivity” and “White fragility”. Codes were subsequently clustered into several abstract categories related to the discursive contexts within which reflexivity was being produced: generational (dis)connectedness, ever-evolving public discourses, and identity (re)considerations.

Within each of these clusters, we performed a CDA of the applicable coded interview fragments, informed by the tools proposed by Machin and Mayr (Citation2012). This enabled us to examine individual responses within broader discourses, zooming in on reflexive moments. In line with Machin and Mayr’s (Citation2012) method, this was done by paying attention to lexical choices – i.e. using specific words and their synonyms (overlexicalization); absences (suppression) to highlight what may be silenced or taken for granted; structural oppositions; and language used to add authority or credibility to statements (e.g. highlighting that friends of color agreed that ZP should “simply” remain black). Five tactics used by White people when discussing race () further sensitized the analysis process (Augoustinos and Every Citation2007).

Table 2. CDA Sensitizing concepts.

Interviews were approached as proxies of common language practices used to justify and prevent being perceived as prejudiced (Augoustinos and Every Citation2007). For instance, participants would go back and forth on arguments, pointing to internal dilemmas between “lived ideology” (i.e. dominant and/or taken-for-granted ideas about race in the Netherlands) and “intellectual ideology” (i.e. abstract worldviews about race) (Billig Citation1988, 28). We considered such internal dilemmas as reflexivity-conducive contexts, as participants would stop and question themselves or become unsure or uncomfortable with what they said. Ahearn’s (Citation2011) notion of “meta-agentive discourse” helped to uncover how narratives may attribute more or less agency to actions and how this agency relates to structural inequalities (284). Finally, the analysis took onboard Wetherell and Potter’s (Citation1992) suggestion that everyday reasoning is never neatly organized or clear-cut. Individuals thus may approach the ZP debate through multiple tactics, changing their position and making contradicting statements.

Researcher reflexivity

Research (re)produces discourses around race and racism, necessitating a thoughtful reflection on our role in data generation and interpretation (Alejandro Citation2021). Methodologically, we focused on White Dutch people, reasoning that this group’s understanding of race and racism is filtered through the lens of hegemonic Whiteness (Hughey Citation2022; van den Broek Citation2020; Wekker Citation2016). While we aimed to uncover how this lens hinders critical engagement with race and racism and how reflexivity can disrupt it, we acknowledge the exclusion of already marginalized voices from the production of scientific research.

Furthermore, the study prompted us to grow increasingly aware of – and uncomfortable with – our own Whiteness. We had to face our biased expectations about our participants; for example, we critically reflected on our own surprise when a participant with Indonesian roots (a former Dutch colony) highlighted the ambiguity of her Whiteness and thus challenged our preconceived notion of Whiteness as a straightforward category. Our Whiteness – and ensuing privileges and assumptions – also shaped interview interactions, unwittingly reproducing (in the interview context) the very hegemonic Whiteness we sought to uncover. Çankaya and Mepschen (Citation2019) argue that “we have limited influence on how we are socially located and how our respondents see or do not see us. Whiteness, despite its slipperiness, imposes itself on doing anthropology.” (637). This became evident to us when a participant brought up her ease of talking with the interviewer because of their shared Whiteness. More often than not, such assumptions are not even verbalized, presenting themselves as “good rapport” (for instance when one participant highlighted that the interviewer’s “friendly face” made her approachable). Yet, such moments “do Whiteness” during research interviews. Furthermore, rapport can also be enhanced by the intersection between the assumption of shared Whiteness and other salient forms of social categorization, such as socioeconomic class (Çankaya and Mepschen Citation2019).

In turn, these assumptions are implicated in what participants feel at ease to bring up, but also in how race is “hidden, denied and concealed, and thus continued” in the stories thus co-constructed between the researcher and the participants (Çankaya and Mepschen Citation2019, 637). For instance, when a participant referred to a White TV host’s performance as the “right” way to address ZP’s racism, contrasting it with the stance of a Ghanese-Dutch activist during a protest, the interviewer did not call out this structural opposition. By staying silent, the interviewer inadvertently participated in this moralizing narrative of “right” versus “wrong”.

A conscious effort to not only study reflexivity, but also to reflexively question our participation in the (re)production of (hegemonic) narratives around race and racism made us more attentive to the influence of privilege and assumptions during participant recruitment and interviews (e.g. nodding, empathetic “yes”-es or not intervening when participants used racist language). We have also consciously attempted to incorporate this reflexive questioning in the analysis process and the findings presented next.

Findings

Our participants reflexively engaged with race and racism through three discursive contexts that we will discuss next: (1) generational (dis)connectedness, (2) ever-evolving public discourses, and (3) identity (re)considerations.

Generational (dis)connectedness

Participants positioned the ZP debate as part of a larger social transformation, leading to reflection on their own alignment with the times. Some discussed this transformation as a form of generational (dis)connectedness, reflecting on the differences between themselves and younger generations. While, as anticipated, social transformation was filtered through identity work, perceiving change as inevitable colored participants’ willingness to critically engage with their own views on race and racism.

To discuss early formative years concerning the ZP-tradition, interviews began with personal recollections of Sinterklaas celebrations, often framed as inherently positive:

Well, that’s always a party, of course, with small presents. Of course, we weren’t that rich in the early years, so that wasn’t extravagant, but it was just the anticipation of the Sinterklaas period. […] It was just fun, always … and now and then, a ‘Zwarte Piet’ and Sinterklaas also came over, of course. (Egbert, 77)

Why should it be changed like this all of a sudden? Why? What have those people done wrong? What did Zwarte Piet do wrong? Nothing! He just wants to be friendly to the children. And then he is being forced to lea … gone! Not allowed anymore. Because he looks black. (Olaf, 92)

This construction of ZP as “not racism” also operates through the insistence to dismiss ZP’s blackface as an allegedly neutral reflection of color; Yvonne (94) felt it was “very normal” when her child compared a Black child with ZP. When asked whether this comparison could have been a bad experience for the child in question, she responded: “No, quit it! […] Then we should experience everything as harmful!”. This minimalization of race and racism, then, goes hand in hand with framing anti-ZP activism as “looking for nails at low tide [i.e. nitpicking]” (Niels, 65), evoking the idea of post-racism times when talking about race allegedly becomes irrelevant. Invoking the interviewer’s Whiteness to bridge the age gap and deflect possible charges of racism, participants were able to fall back upon an essentialist view of race as a barrier to mutual understanding: “I think like those conversations we’re having right now […] But this is my experience, […] I can talk to you more easily than if a dark-skinned girl were sitting here” (Yvonne, 94).

Other participants, however, reflexively questioned their biases during the interview. Egbert (77), for instance, contrasted his own “[un]acceptable” fear that Moroccan-Dutch youth might “take [his] wallet” to his stepson’s worldviews and experiences. Having grown up with Moroccan-Dutch peers, his stepson did not seem to share Egbert’s fears. In turn, this prompted Egbert to question how his views – and fears – were interwoven with his personal experiences shaped by a time when racialized “others” were less visible in his surroundings. For others, such differences in experiences led to further discussions of generational (dis)connectedness. Niels (65) recalled that his daughter changed from being “totally excited about ZP” to becoming “very anti-ZP”. He later “had to confess that [discussions with her] did influence him … a bit”.

Those differences in experiences were also used to explain the inter-generational differences in attitude towards changing traditions:

For example, our generation and my father’s and mother’s […] had nothing to do with that. And with a multicultural society, that all came later. And that’s getting worse with all those, uh, immigrants coming in. They all need a place. And of course, we have already lost parts of the Netherlands in that regard … Well, not lost. But … it has become multicultural, especially in the big cities […] So I think today’s youth would more likely think: OK, we live in a multicultural society. There has been discrimination in the past. We don’t know the details, but oh well, just get rid of it and just do ‘soot wipe Pete’. (Nico, 66)

Yet, Nico also seems concerned with phrasing a politically correct stance on racial diversity. The frame of inter-generational (alleged) differences in experiences with diversity provides a way out of this dilemma, rescuing the romantic framing of the past as well as the deeply personal feelings coloring this past. Ultimately, the story re-affirms the racially essentialized “we” (White Dutch people), juxtaposing it with the problematic “them” (“immigrants”) whose presence introduces tensions into the social body.

The perception of generational differences, then, comes to frame participants’ understanding of societal transformation. When these generational differences are seen as a loss, reflective engagement with race decreases and participants resist/reject the increasing pressures on Whiteness as a hegemonic discourse by positioning themselves as victims of a changing world (Giddens Citation1991; Rafieian and Davis Citation2016; Riach Citation2009). However, generational differences can also foster reflexivity, especially when the focus shifts from losing family connection to understanding the new generation’s views. Reflecting on race remains challenging, as participants grapple with reconciling romanticized but deeply meaningful personal experiences with the changing public opinion.

Ever-evolving public discourses

The second discursive context prompting reflexivity around race centers upon public debates around ZP, race and racism. Where Dutch public discourses have perpetuated hierarchical differences among citizens, anti-ZP activists explicitly link such discourses to colonialism and slavery, facing White Dutch people with a less romanticized vision of history (Balkenhol Citation2016; Euwijk and Rensen Citation2017; van Sterkenburg, Knoppers, and de Leeuw Citation2012; Vliet Citation2022). Eduard (69) reflects on why he never saw any issues with the ZP-tradition before:

When journalism gets involved, when people start publishing about it, something like this starts to simmer. […] because a newscast is intrusive, and many people watch the news. […] So then, you get confronted with it. If you also read about it in the newspapers. Then yes, you get an idea about that. But it wasn’t discussed back then.

[D]efinitely that dark-skinned people dare to express themselves more. That’s important too. And that […] dark-skinned people have gotten higher positions in society. And they were more comfortable with … daring to express … about the past. […]. So maybe they have a deep-rooted problem, which other people ranked lower in society didn’t dare to speak about, or who don’t talk about it at all because they are afraid of it or something. So, in the multicultural society all people, of all skin colors, also White and Black, engage in discussions more easily, because you have to deal with each other.

Hegemonic discourses remained important resources in participants’ construction of “not racism” (Lentin Citation2018). For instance, Olaf echoed color-blindness discourses when he said that Black people and people of color (POC) just have “a different color [and have] been in the sun more”, emphasizing that “[t]hose are regular people. And [he] always treated them and always will treat them as if they were regular people”. Against public debates on systemic racism in the Netherlands, the trivialization of race goes hand in hand with shielding the self from possible accusations of racism.

Another deflection strategy echoing Dutch media discourses shifts the focus from the racism underpinning ZP to the character of the activists themselves (portrayed as aggressive, emotional, or irrational) (Van Dijk Citation1992; Vliet Citation2019). For instance, Sebastiaan (73) created a structural opposition between the Ghanese-Dutch artist and antiracism activist Akwasi, whom he depicted as “not being open to nuance”, and the White Dutch TV-host Arjen Lubach, whose song addressing the same issue was depicted as “an excellent way to make [the issue] clear”. While Sebastiaan did not bring up race, such examples reproduce racialized hierarchies where White speakers can more easily garner attention when drawing attention to racism.

However, media discourses around race and racism also prompted participants to reflect on White privilege. An article about the disadvantages faced by job applicants with a migration background made Yvonne (94) reflect on how “Dutch people […] are preferred”. Reading interviews about Black people’s childhood experiences with ZP made Egbert (77) realize “that those children did not feel comfortable at all”. Participants highlighted the need to read about these experiences to “get an idea about that” (Eduard, 69).

Whether and how such reflexivity carries over into broader worldviews remains outside the scope of this project. However, recognition of racism was often immediately followed up by an attempt to deflect the possible accusation of being racist by invoking personal experience, and the changing discourses illustrated the struggle around reflexivity. Eduard (69), for instance, felt that media discourses prompted him to confront his views on race, but deflected blame by highlighting that this topic “wasn’t discussed back then”. Niels (65) saw value in the public debate about the consequences of slavery, but he also remained reluctant to accept the idea that White Dutch people owed some type of collective “inheritance debt”. Sjaak (67) spoke against discrimination, yet he also belittled public discourses on colonialism and slavery as part of a “media hype” that “polarizes” and causes “discrimination to flourish”.

Such examples illustrate how competing public discourses around race and racism enable participants to engage in a dance of becoming reflexive, then falling back upon personal experience to legitimize their pre-existing views. Everyone in our sample was familiar with varying discourses around race and racism, drawing from them for different conversational purposes. While the impact of the reflexive potential of such a discursive “dance” is difficult to ascertain, its presence suggests personal views around race and racism remain open to reinterpretation.

Identity (re)considerations

While the previous discursive contexts highlight engagement with external circumstances, here the focus was on how reconsideration of race and racism may pave the way or stifle critical self-questioning. The interweaving of tradition and family life made it difficult to confront the racism in ZP, as confronting tradition also destabilized participants’ sense of self: Rob (66) commented that, at first, the ZP debates made him feel “like you’ve done something wrong yourself”, while Leendert (66) struggled with the implication that having “played Zwarte Piet” for his children meant he should critically revisit cherished memories. When change in the appreciation for tradition appears inevitable, the seeming loss of cherished memories about one’s family morphs into a lack of agency – as exemplified in Elly’s (74) feeling that ZP was “abolished […] to be able to meet the wishes of those people”. This us-versus-them framing suggests unease with (alleged) social changes – and this unease can limit the willingness to critically engage with the anti-ZP arguments.

Personal experience, however, can also pave the way for reflexive reconsideration of tradition. Edith (86) described how her identity struggles affected her stance on ZP: “In some contexts, I’m White and in others … in this kind of discussion I don’t know”. As an Indonesian-Dutch woman born in a then-Dutch colony and one of the “first dark-skinned people to come here […] en masse”, Edith’s (86) identities made her more “alert to discrimination” than other White people who see “a world without discrimination”.

Personal and positive encounters with others (who are, nonetheless, racialized) can also prompt reflexivity processes. Personal connections with Black people and POC prompted participants to reflexively inspect their own views towards race and racism and ZP. This made it “easier to sympathize with [anti-ZP] arguments” (Rob, 66) and increased their awareness of racism in the Netherlands. When asked how reading about Black experiences with ZP made him feel, Egbert (77) brought up his Surinamese daughter-in-law, who “[b]ecause she is dark-skinned, […] faces discrimination”. For Egbert, “it is very sad to hear that people are affected by this”.

Rob (66) added that conversations about race and racism were also prompted by media coverage of the ZP-debate. He highlighted how his partner and him “were privileged because [they] had already been having that discussion through [their friends of color]”. However, due to the media attention, the debate also became a topic of discussion between White people at “a birthday party […] or something”. Rob pointed out that this would sometimes lead to fierce emotional discussions, the latter would also prompt individuals to think deeper about race and racism. The interview itself also seemed like such a push towards reflexivity: not only did participants display real-time reflexivity during the interview, but some also followed up after the interview with additional thoughts – suggesting the participants continued to think about the topic afterward.

Hence, the individual processing of these conversations offered space to take up experiences and reconsider one’s own (racial/cultural/generational) identities. Rob (66) echoed this idea when he explained that discussing ZP’s racist implications prompted him to ask himself: “that’s not how I look at those people, right?”. He further described how discrimination had “always been an important point” for him. However, it was not until his friends explained the effects of ZP that he started questioning his own racial biases:

Yes, that shocked me. Then I had to try to switch a button for myself, and I did. But […] first I had to be aware of it, before I could accept that I too had to deal with that, with the institutional racism that is part of your upbringing. (Rob, 66)

Discussion

Each of the three analytically distinguished discursive contexts offered their own openings for reflexivity. Participants were, on occasion, willing to question their own stance on race and racism; they hesitated when reproducing hegemonic discourses and demonstrated awareness of how public debates around ZP re-organize(d) collective moral frameworks. Yet, this awareness brought along existential anxieties around one’s own identity and life experience, with cultural aphasia taking over when critical awareness did not resonate with one’s own “truth” formed through life-long personal experiences and hegemonic discourses (Helsloot Citation2012). On such occasions, the familiarity of hegemonic Whiteness discourses offered perceived “escape routes” from these anxieties while simultaneously feeding into them. Depending on how they processed personal experiences and circumstances within each of the three discursive contexts outlined above, participants either looked forward to social change, reflexively engaging with it; or, they looked backward, re-anchoring themselves into the comfort of the familiar. This, we argue, can be metaphorically understood as a “dance of reflexivity”, as illustrated below ().

Despite displaying an increased awareness of Dutch colonial history, few participants were willing to acknowledge their own privilege derived from it, often dismissing it as a past issue. In line with previous findings of denial strategies regarding race and racism in the Netherlands, our participants invoked the perceived innocence of the tradition of ZP to depoliticize racism and displayed a smug ignorance towards the tradition’s ties to Dutch history of colonialism and slavery (Chauvin, Coenders, and Koren Citation2018; Van der Pijl and Goulordava Citation2014; Wekker Citation2016). This smug ignorance persisted, hindering critical engagement with and acknowledgment of systemic oppressions that continue to prevail in Dutch society. Racial differences were largely taken for granted, with only two participants showcasing how their personal experiences had prompted critical questioning and a reflexive reconsideration of their Whiteness and Dutchness.

For this age group, generational differences emerged as a significant discursive frame for interpreting social change. Particularly when taking in the challenges to the ZP tradition, generational differences functioned as a discursive frame within which the reflexive renewal of the tradition was made sense of. In some contexts, invoking generational differences enabled our older White Dutch participants to circle around the pressures on Whiteness as a hegemonic discourse and to position themselves as victimized by a world in which they perceive themselves as no longer active contributors (Giddens Citation1991; Rafieian and Davis Citation2016; Riach Citation2009). This feeling intensified with younger generations’ perceived ease in dismissing the tradition. However, in other cases, the generational gap offered an opportunity to challenge personal biases and reflect on the changing legitimacy of worldviews over time. The perception of agency concerning social transformation – or the extent to which individuals saw themselves as either left behind by social change or as an active contributor to it – appears to mediate between these different stances.

As (largely mediated) ZP-debates increasingly draw attention to the presence and implications of systemic racism in the Netherlands, some older White Dutch individuals interpret this as an imposition on their lifestyle or a challenge to their lifelong experience. In this context, hegemonic Whiteness provides discursive resources to reframe their position as one of resignation and irritation with social transformation prompted by external “others” (younger people and/or racialized “others”), who simply cannot understand their position (DiAngelo Citation2018; Essed and Trienekens Citation2008; Hughey Citation2010; van den Broek Citation2020; Wekker Citation2016). This is akin to what Dahlgren (Citation1981) described as a form of non-reflexive viewer consciousness, where news media leave individuals feeling left behind by social transformation. That is not to say that this issue is only salient for older people, but rather that they used their age to deflect responsibility for grappling with anti-ZP arguments and adaptations to the tradition. In that sense, age and generational differences can also function as a form of aphasia, providing alternative “operational meanings” for ZP that can further disconnect this tradition from its racist dimensions (Helsloot Citation2012).

The coexistence of reflexive questioning and hegemonic discourses demonstrates the complex interplay of factors shaping individual attitudes on race and racism. This is particularly evident in individual reasoning when reflexivity threatens life experience and personal worth, which have been partly formed by the perceived innocence of ZP – and of Whiteness and Dutchness more broadly. On the one hand, this seems to be a consequence of the centrality of life experiences to an individual’s identity; in such moments, the opportunities for critical questioning are inhibited by the emotions associated with family memories or worldviews resulting from lifelong experiences and confrontation with public discourses over time. On the other hand, while hegemonic Whiteness provides discursive resources that enable individuals to deflect critical self-questioning, everyday life remains unruly and destabilizing in and of itself. Whether via news media discourses or anti-racism activist voices, or via personal encounters and connections (for instance, with family members or close others speaking about the racism of ZP or demonstrating different attitudes towards diversity), individuals are constantly nudged towards reflexively engaging with their own experiences and views. Overall, reflexivity on race and racism at the individual level proves a slow and convoluted process, as hegemonic discourses continue to offer powerful resources enabling individuals to cope with the anxiety of transformative learning by deflecting and avoiding a re-assessment of personal bias and privilege.

Conclusion

This study has delved into the intricate dynamics of reflexivity on race and racism among older White Dutch individuals. Reflexivity on race and racism among older adults is less studied; our findings suggest reflexivity among this age group is linked to three discursive contexts: (1) generational (dis)connectedness, (2) public discourses, and (3) identity (re)considerations. Within these discursive contexts, reflexivity emerges as a “dance” between, on the one hand, personal emotional and cognitive predispositions and, on the other, the pervasive influence of hegemonic Whiteness discourses. Reflexivity around race and racism remains a back-and-forth, non-linear, and fragmented process, where individuals struggle to balance moments of self-questioning with significant anxieties about their self-worth. Importantly, for older adults, these anxieties are interwoven with feelings of loss of agency and relevance against the context of a (perceived or real) generational gap.

Where hegemonic Whiteness provides participants with discursive mechanisms for avoiding the emotional consequences of reflexively interrogating one’s worldviews, understanding oneself as an active social agent – and thus curious towards social transformation – and being able to cope with the consequences of being (morally) wrong appears to stimulate reflexive questioning of one’s views on race and racism. Yet, the ways in which individuals resolve this tension remain highly subjective and circumstantial. Even when recognizing racism and discrimination at an abstract level, participants remained reluctant to question Whiteness as a hegemonic structure shaping their own biases.

Importantly, we draw attention to the need to further investigate how acknowledgment of racism can further lead to increased personal reflexivity not only on racist biases but also on the very notion of race as an essentializing social category. While the exact impact of this discursive “dance” on reflexivity remains challenging to gauge, its existence implies that personal views on race and racism remain fluid and open to (re)interpretation. One limitation in our project derives from the data collection tool: interviews capture the production of reflexivity at one particular moment in time; linking such moments to life trajectories is also subject to selection and recollection biases. A longitudinal approach to the production of reflexivity can add more nuance to these findings. Additionally, exploring what enables older individuals to understand themselves as active social agents and to deal with the destabilizing identity effects of reflexivity on race and racism could further clarify the mediating role of cognitive and emotional predispositions in encouraging reflexivity at an individual level.

Statement of ethics

The study has received ethics clearance from the Erasmus University Rotterdam Ethics Board ETH2223-0051. All participants provided their explicit consent for the interviews to be used as material for a scientific article. All transcripts were anonymized and pseudonymized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Mélodine Sommier, Julia Herkommer, Polina Kuzmina, and Patrick Edwards for reading and commenting on previous drafts of this manuscript. We are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their detailed suggestions and constructive criticism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We capitalize ‘Black’ and ‘White’ to emphasize that the terms refer to the socio-political construction of race as an instrument of social categorization (Appiah Citation2020; Nguyễn and Pendleton Citation2020).

2 In this article, we distinguish between the concepts race and racism, even though they are interdependent: “[R]ace continues to matter because it is in a continual process of reinvention” and therefore it is not “sufficient or possible to talk about racism without explaining the genealogy of race as a system of rule and revealing this process of continual reproduction. […] [R]acism is better understood as beliefs, attitudes, ideas, and morals that build on understandings of the world as racially delineated” (Lentin Citation2020, 9).

3 The Dutch school system explained: “[a]fter completing primary school, pupils move on to one of three types of secondary education: pre-vocational secondary education (VMBO), senior general secondary education (HAVO) or pre-university education (VWO). Secondary education prepares pupils for secondary vocational education (MBO), higher professional education (HBO) or university education” (Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, n.d.). LTS is a former Dutch school type, precursor of VMBO.

References

- Ahearn, L. M. 2011. Living Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Alejandro, A. 2021. “Reflexive Discourse Analysis: A Methodology for the Practice of Reflexivity.” European Journal of International Relations 27 (1): 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120969789.

- Appiah, K. A. 2020, June 18. “The Case for Capitalizing the B in Black.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/time-to-capitalize-blackand-white/613159/.

- Augoustinos, M., and D. Every. 2007. “The Language of “Race” and Prejudice.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 26 (2): 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X07300075.

- Balkenhol, M. 2016. “Silence and the Politics of Compassion. Commemorating Slavery in the Netherlands.” Social Anthropology 24 (3): 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12328.

- Bartels, L. M., and S. Jackman. 2014. “A Generational Model of Political Learning.” Electoral Studies 33:7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.06.004.

- Billig, M. 1988. “Dilemmas of Ideology.” In Ideological Dilemmas – A Social Psychology of Everyday Thinking, edited by M. Billig, S. Condor, D. Edwards, M. Gane, D. Middleton, and A. Radley, 25–42. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2015. “The Structure of Racism in Color-Blind, “Post-Racial” America.” The American Behavioral Scientist 59 (11): 1358–1376. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764215586826.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2018. Racism Without Racists. 5th ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Çankaya, S., and P. Mepschen. 2019. “Facing Racism: Discomfort, Innocence and the Liberal Peripheralisation of Race in the Netherlands.” Social Anthropology 27 (4): 626–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12699.

- CBS. n.d. “Inwoners per gemeente [Inhabitants per municipality].” https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/regionaal/inwoners.

- Chauvin, S., Y. Coenders, and T. Koren. 2018. “Never Having Been Racist.” Public Culture 30 (3): 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-6912163.

- Dahlgren, P. 1981. “TV News and the Suppression of Reflexivity.” In Mass Media and Social Change, edited by E. Katz and T. Szecskö, 101–113. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- DiAngelo, R. 2018. White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Emirbayer, M., and M. Desmond. 2012. “Race and Reflexivity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 35 (4): 574–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.606910.

- Essed, P. 1991. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Essed, P., and S. Trienekens. 2008. “‘Who Wants to Feel White?’ Race, Dutch Culture and Contested Identities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31 (1): 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701538885.

- Euwijk, J., and F. Rensen. 2017. De identiteitscrisis van Zwarte Piet. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact.

- Fillieule, O. 2013. “Age and Social Movements.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social & Political Movements, edited by D. A. Snow, Donatella della Porta, B. Klandermans, and D. McAdam, 1–3. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm004.

- Fisher, A., K. Wauthier, and R. Gajjala. 2020. “Chapter 8: Intersectionality.” In The SAGE Handbook of Media and Migration, edited by K. Smets, K. Leurs, M. Georgiou, S. Witteborn, and R. Gajjala, 53–63. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526476982.n10.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Giddens, A. 1993. “Modernity, History, Democracy.” Theory and Society 22 (2): 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993501.

- Golash-Boza, T. 2016. “A Critical and Comprehensive Sociological Theory of Race and Racism.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2 (2): 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649216632242.

- Goldberg, D. T. 2006. “Racial Europeanization.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 29 (2): 331–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500465611.

- Guest, G., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability.” Field Methods 18 (1): 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Helsloot, J. I. A. 2012. “Zwarte Piet and Cultural Aphasia in the Netherlands.” Quotidian: Journal for the Study of Everyday Life 3:1–20.

- Hilhorst, S., and J. Hermes. 2016. “‘We Have Given up so Much’: Passion and Denial in the Dutch Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) Controversy.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 19 (3): 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415603381.

- Hughey, M. W. 2010. “The (dis)Similarities of White Racial Identities: The Conceptual Framework of ‘Hegemonic Whiteness’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (8): 1289–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870903125069.

- Hughey, M. W. 2022. “Superposition Strategies: How and why White People say Contradictory Things About Race.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 119 (9): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116306119.

- I&O Research. 2020. “Nederland accepteert verandering (Zwarte) Piet [the Netherlands are accepting the change of (Black) Pete].” I&O Research. https://www.ioresearch.nl/actueel/zwarte-piet/.

- Kluttz, J., J. Walker, and P. Walter. 2020. “Unsettling Allyship, Unlearning and Learning Towards Decolonizing Solidarity.” Studies in the Education of Adults 52 (1): 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2019.1654591.

- Koning, E. 2018. “Zwarte Piet, een blackfacepersonage [Black Pete, a blackface character].” Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis 131 (4): 551–575. https://doi.org/10.5117/TVGESCH2018.4.001.KONI.

- Krumer-Nevo, M., and O. Benjamin. 2010. “Critical Poverty Knowledge - Contesting Othering and Social Distancing.” Current Sociology 58 (5): 693–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392110372729.

- Kvale, S. 2007. “Doing Interviews.” https://dx-doi-org.eur.idm.oclc.org/10.41359781849208963.

- Lentin, A. 2018. “Beyond Denial: ‘Not Racism’ as Racist Violence.” Continuum 32 (4): 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1480309.

- Lentin, A. 2020. Why Race Still Matters. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Lewis, A. E. 2004. ““What Group?” Studying Whites and Whiteness in the era of “Color-Blindness”.” Sociological Theory 22 (4): 623–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2751.2004.00237.x.

- Machin, D., and A. Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Mannheim, K., ed. 1952. The Problem of Generations. London: Routledge.

- McCluney, C. L., D. D. King, C. M. Bryant, and A. A. Ali. 2020. “From “Calling in Black” to “Calling for Antiracism Resources”: The Need for Systemic Resources to Address Systemic Racism.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion an International Journal 40 (1): 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-07-2020-0180.

- Mezirow, J. 2000. “Learning to Think Like an Adult. Core Concepts of Transformation Theory.” In Learning as Transformation. Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress, edited by J. Mezirow and Associates, 3–33. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Nationaal Archief. n.d. “Einde aan een treurige geschiedenis van slavernij (1863) [An end to the sad history of slavery (1863)].” Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/beleven/onderwijs/bronnenbox/einde-aan-een-treurige-geschiedenis-van-slavernij-1863.

- Nederland Wordt Beter. n.d. “Tijdlijn [Timeline].” https://nederlandwordtbeter.nl/tijdlijn/.

- Nguyễn, T., and M. Pendleton. 2020, March 23. “Recognizing race in language: why we capitalize “Black” and “White” Center for the Study of Social Policy.” https://cssp.org/2020/03/recognizing-race-in-language-why-we-capitalize-black-and-white/.

- Ortiz, S. M. 2021. “Racists Without Racism? from Colourblind to Entitlement Racism Online.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (14): 2637–2657. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1825758.

- Owens, T. J., D. T. Robinson, and L. Smith-Lovin. 2010. “Three Faces of Identity.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134725.

- Perera, K. 2020. “The Interview as an Opportunity for Participant Reflexivity.” Qualitative Research 20 (2): 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119830539.

- Rafieian, S., and H. Davis. 2016. “Dissociation, Reflexivity and Habitus.” European Journal of Social Theory 19 (4): 556–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431016646516.

- Riach, K. 2009. “Exploring Participant-Centred Reflexivity in the Research Interview.” Sociology 43 (2): 356–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508101170.

- Rodenberg, J., and P. Wagenaar. 2016. “Essentializing’ Black Pete’: Competing Narratives Surrounding the Sinterklaas Tradition in the Netherlands.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (9): 716–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1193039.

- Rossi, I. 2014. “Reflexive Modernization.” In Ulrich Beck. Pioneer in Cosmopolitan Sociology and Risk Society, edited by U. Beck, 59–64. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04990-8_5.

- Siebers, H. 2017. ““Race” Versus “Ethnicity”? Critical Race Essentialism and the Exclusion and Oppression of Migrants in the Netherlands.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (3): 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1246747.

- Smaje, C. 1997. “Not Just a Social Construct: Theorizing Race and Ethnicity.” Sociology 31 (2): 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038597031002007.

- Twine, F. W., and C. Gallagher. 2008. “The Future of Whiteness: A map of the ‘Third Wave’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31 (1): 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701538836.

- van Amstel, L. 2013, October 23. “Pietitie in een dag een miljoen ‘likes’ op Facebook [Pete-ition over a million ‘likes’ on Facebook within a day].” EenVandaag. https://eenvandaag.avrotros.nl/item/pietitie-in-een-dag-een-miljoen-likes-op-facebook/.

- van den Broek, L. M. 2020. Wit is nu aan zet: racisme in Nederland. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press B.V.

- Van der Pijl, Y., and K. Goulordava. 2014. “Black Pete, “Smug Ignorance,” and the Value of the Black Body in Postcolonial Netherlands.” New West Indian Guide 88 (3–4): 262–291. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134360-08803062.

- Van Dijk, T. A. 1992. “Discourse and the Denial of Racism.” Discourse & Society 3 (1): 87–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003001005.

- van Sterkenburg, J., A. Knoppers, and S. de Leeuw. 2012. “Constructing Racial/Ethnic Difference in and Through Dutch Televised Soccer Commentary.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 36 (4): 422–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723512448664.

- van Sterkenburg, J., R. Peeters, and N. van Amsterdam. 2019. “Everyday Racism and Constructions of Racial/Ethnic Difference in and Through Football Talk.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (2): 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549418823057.

- Vliet, D. 2019. “Defending Black Pete: Strategies of Justification and the Preservation of Tradition in Dutch News Discourse.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 36 (5): 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2019.1650947.

- Vliet, D. 2022. “Resisting the Abolition Myth: Journalistic Turning Points in the Dutch Memory of Slavery.” Memory Studies 15 (4): 784–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698019900970.

- Wekker, G. 2016. White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Wetherell, M., and J. Potter. 1992. Mapping the Language of Racism. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.