ABSTRACT

The Brexit referendum was a seismic electoral event with far-reaching consequences, but ethnic minority voters’ decisions in the referendum remain under-researched. We examine what differentiates ethnic minority Remainers from Leavers in two large social surveys. Ethnic minority voters were divided along ethnocentric and generational lines, similarly to majority voters. Those who were born overseas were more likely to support Brexit; meanwhile, younger minorities and those born in the UK were more supportive of Remain, like their young white British counterparts. We show that anti-immigrant attitudes, including views on Turkey joining the EU, mattered for ethnic minority Leavers, as well as sovereignty concerns. Our results reveal that the factors that led minorities to vote to leave the EU were not altogether different from those identified for white British voters. We argue the concept of left behind can include minorities, and research must therefore consider what role whiteness plays in this concept.

Grievances that motivated Leave voters have been extensively studied, painting a picture of the “left behind”: economically-marginalised, older, poorly-educated white men who tended to support Brexit, and the radical right (Ford and Goodwin Citation2010; Citation2014; Goodwin and Milazzo Citation2015; Hobolt Citation2016). These accounts identify that being white was a strong predictor of voting Leave (Hobolt Citation2016), and that white Britons’ attitudes towards ethnic minorities contributed to support for Leave (Shaw Citation2022; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020; Virdee and McGeever Citation2018). Given the lack of research on ethnic minority Leave voters, this has inadvertently led to the over-simplifying contrast of white British Leavers with ethnic minorities en bloc, as well as unspoken assumptions about whiteness as a pre-requisite for being left behind, and about working classes’ whiteness (Bhambra Citation2017; Mondon and Winter Citation2020). That little has been written about the substantial proportion of Leavers among ethnic minorities is puzzling, as support for Leave among minorities was higher than it has ever been for the Conservative Party (Martin and Khan Citation2019). What little empirical research exists (Begum Citation2023; Martin and Sobolewska Citation2023), suggests some of the notions of being left behind, such as anti-immigrant sentiments, did influence some ethnic minority Leavers. Similarly, although predominantly as commentary and not empirical contributions, many have made the point that ethnic minorities in Britain form a substantial part of the economically-marginalised population (Isakjee and Lorne Citation2019; Khan, and Shaheen Citation2017). In contrast, most prominent political science scholarship on the referendum largely ignores minority voters or considers them solely as an explanatory variable of white voters’ behaviour (Cutts et al. Citation2019; Goodwin and Milazzo Citation2017). The nativist and anti-immigrant parts of the Leave campaign meant that fewer minorities supported Leave, seeing this nativism as excluding them as non-white Britons from Great Britain’s national story (Khan and Weekes-Bernard Citation2015). But further study is urgently required to understand ethnic minority views on the largest electoral upset in recent decades. It is quite possible that minorities who voted to leave the European Union did so for reasons not altogether different from white British voters.

In this paper, we investigate what divided ethnic minority Leavers from Remainers and hypothesise that the narratives of left-behind voters – those who are older, marginalised, and anti-immigrant – hold well for ethnic minority voters too. Drawing on triangulated survey data, what we find contradicts the view that ethnic minority voters who voted to Leave were very different to white Brexiters. We find that age, economic marginality, and anti-immigrant sentiment were good predictors for voting Leave among minorities, and that similarly to white voters, partisanship had little impact. The referendum was a rare political context where strong negative partisanship against the Conservatives (widespread among minorities (Heath et al. Citation2013)) was less relevant, and campaign groups were able to link minority grievances with the anti-EU cause, thereby activating anti-immigrant sentiment in ways parallel to the general population (Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). We conclude that although support for Brexit was much lower among ethnic minority voters than their white counterparts, the ethnic minority Leave voter largely conformed to the picture of the left behind. This has wider importance beyond the British case, as the left behind and similar narratives about the losers of globalisation have become major explanatory concepts for political phenomena in many countries in recent decades (Gidron and Hall Citation2017; Kriesi et al. Citation2006). Ethnic minority voters have very high levels of eligibility to vote in elections with UK and Commonwealth citizens having the same voting rights, and so the views of this group on European integration may be indicative of future debates in other states with developing minority electorates. We hope that showing how ethnic minorities who voted for Leave fit the picture of left-behind voters will add to the voices challenging the methodological whiteness of electoral studies (Bhambra Citation2017). We also hope that mainstream political science will take note of this original empirical quantitative evidence that validates the more aggregate and normative arguments of those who have challenged the exclusion of ethnic minorities in accounts of the left behind (Isakjee and Lorne Citation2019).

Voting to leave

The underlying causes of Brexit are complex and cross-cutting, with people of all class backgrounds, party affiliations and geographical locations among those voting for Leave, but the vast majority of research has identified that people who voted to Leave were especially likely to be older, less well-educated, and economically more precarious (Alabrese et al. Citation2019; Goodwin and Heath Citation2016). These demographic predictors largely appeared to be mediated by opposition to immigration, social authoritarianism and ethnocentrism, which were key attitudes dividing white British Leavers from Remainers, and which vary significantly by education and age (Evans and Menon Citation2017; Fieldhouse et al. Citation2019; Hobolt Citation2016; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). However, existing explanations are not designed with ethnic minorities in mind, and most largely ignore the role of race and ethnicity (Evans and Menon Citation2017; Fieldhouse et al. Citation2019) or consider ethnic minorities solely as an explanatory factor in the voting habits of white voters (Cutts et al. Citation2019; Goodwin and Milazzo Citation2017). Overlooking ethnic minority Leavers has led to the conclusion that the group of voters cast as left behind or as identity conservatives is exclusively white. This has in turn led to the omission of ethnic minorities from the concept of left behind or identity conservatives. Partly, this has been caused by the lack of available data on minority voters, and partly by the fact that the majority of ethnic minorities voted to Remain.

In contrast, critical sociological research has drawn more attention to the racial dimensions of Brexit voting. Patel and Connelly’s (Citation2019) qualitative interviews in Salford demonstrate how white Brexit voters sought to deracialise support for Brexit, invoking race in terms of the “negative impact of ‘uncontrolled’ immigration on the white ‘indigenous’ population” (981), while simultaneously wishing not to be seen as racist. Virdee and McGeever (Citation2018) trace Brexit as a continuation of postcolonial nostalgia with anti-immigration sentiment underlying (some) support for Brexit as nostalgia for an imagined white Britain before post-war Commonwealth immigration. Khan and Weekes-Bernard (Citation2015) demonstrate how ethnic minorities, including those who are British-born, feel they are still the targets of the immigration debate, with Begum (Citation2023) showing how ethnic minorities were generally ambivalent towards the EU, but voted Remain in opposition to the xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment they perceived in the Leave campaigns. Benson and Lewis (Citation2019), study the views of British ethnic minorities working in EU institutions, highlighting the exclusion of racialised minorities from the European project.

The xenophobia and nativism in parts of the Leave campaign (Virdee and McGeever Citation2018) were clearly off-putting to many ethnic minority voters, who place greater priority on anti-discrimination considerations (Heath et al. Citation2013) and thus were pitted into the pro-Remain coalition as “necessity liberals”Footnote1 (Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). However, this approach precludes the very strong possibility that the sizeable minority of ethnic minority voters who supported Brexit are also left behind demographically (Isakjee and Lorne Citation2019; Mondon and Winter Citation2020), and “identity conservative” in terms of attitudes (Storm, Sobolewska, and Ford Citation2017) in a way that is analogous to Brexit-supporting white voters. Bhambra (Citation2017) and Isakjee and Lorne (Citation2019) have challenged the inherent whiteness of the left behind and the construction of the working class as white, and in particular, ethnic minorities and immigrants being set up in competition with the white working class, despite many being in working class positions. As Bhambra writes, the “losers of globalisation” or the UK-equivalent “left behind” thesis, “describe[s] a relative loss of privilege rather than any real account of serious and systemic economic decline that is uniquely affecting white citizens” (Citation2017, 226). While qualitative research has shed light on the racialised dimensions of Brexit voting, there has been little analysis of ethnic minority voting in the referendum. Indeed, the literature assumes that mechanisms which explain white British voting behaviour in the referendum may not apply to ethnic minority voters, particularly due to the positioning of ethnic minorities as forming part of the “immigration problem” (despite it being EU freedom of movement at stake). We now discuss ways in which – in contrast with existing political science literature – we suspect ethnic minorities more than meet the criteria for the “left behind”.

Age, education and economic marginalisation

Age and education are the most prominent explanations for voting Leave, with most of the literature on Brexit agreeing that Leave voters were older and tended not to have degree-level qualifications (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2019; Hobolt Citation2016; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). These explanations have never been tested for ethnic minority voters, but there are good reasons why a generational cleavage would similarly divide ethnic minority voters in the 2016 EU referendum. While ethnic minority voters are on average younger than white British voters, and a distinguishing feature of the white left behind voter is that they are older (Ford and Goodwin Citation2014; Hobolt Citation2016), we think it likely that there was an age gradient in support for Brexit among ethnic minorities as well. Given that mass migration of today’s ethnic minority groups started in the 1950s, many older minority voters may share the same memories of key events in the development of British Euroscepticism, and most minority groups were well-established in the UK by the time of these formative events. For example, economic hardship following the UK’s exit from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992, known as Black Friday, affected minorities just as much as white Britons, if not more due to hyper-cyclical unemployment rates (Berthoud Citation2000). Given that migrants to the UK with Commonwealth citizenship are able to vote in UK elections on the same basis as UK citizens, these historical political events are just as likely to have been salient to immigrant ethnic minorities as to those born in the UK or with UK citizenship. Meanwhile, younger British ethnic minorities share many of the same generational experiences and values of their ethnic majority peers. This has been shown for other politically relevant values and attitudes (Maxwell Citation2010) and creates a strong expectation that younger Britons regardless of ethnic origin would be more supportive of Remain.

Hypothesis 1: Younger ethnic minority voters were less likely to support leaving the EU than their older counterparts.

In contrast to our expectations on age, educational attainment among ethnic minorities is likely to have a less clear-cut influence on Brexit. Human capital acquired overseas is often not recognised in the UK or rewarded in the labour market, and so education is less of a dividing line in people’s socioeconomic situation – for example, more recent immigrants from former UK colonies are more likely than the white British majority to be over-qualified for the jobs they hold (Altorjai Citation2013). This also applies to a lesser extent for ethnic minority Britons born in the UK, whose educational qualifications reduce but do not eliminate racial discrimination in wage and employment gaps (Zwysen and Longhi Citation2016). And finally, educational expansion among white Britons has contributed to a reduction in ethnocentrism (Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020), which for some voters translates into greater comfort with immigration and multiculturalism. For ethnic minority Britons on the other hand, higher education is unlikely to have the same function as minorities have strong opposition to racism and more pro-immigration views already.

Thus, we think that educational divides will not be related to Brexit among minorities, or at most only for those born and educated in the UK, i.e. who have experiences of the same institutions as the white British population where this education divide in politics has been well-documented.

Hypothesis 2: There will be no difference in support for Leave or Remain between ethnic minorities with different educational qualifications.

The role of economic marginalisation in explaining Brexit is less established in the literature, which on the whole argues that traditional economic cleavages mattered less for the EU membership referendum than for other elections (Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020), but some research suggests it was not inconsequential (Alabrese et al. Citation2019; Goodwin and Heath Citation2016). However, any analysis that seeks to use material deprivation to explain Euroscepticism must recognise that ethnic minority Britons are over-represented in this group. This point has been raised in various post-Brexit commentary (Isakjee and Lorne Citation2019), but has so far failed to be incorporated by election studies. Minorities are more likely to be living in poverty, to be in working class occupations (Li and Heath Citation2020) and to earn less than the living wage (Brynin and Longhi Citation2015) (notwithstanding considerable variation between and within groups). Many ethnic minority migrants came to the UK to take up employment in industries that have since disappeared and live in the type of post-industrial, declining cities and towns that have been strongly associated with large shares of support for Leave (Jennings and Stoker Citation2016). Minorities’ employment prospects are also relatively lower even with the same educational attainment, and there are stark inequalities in housing (Byrne et al. Citation2020; Heath and Cheung Citation2007; Heath and Di Stasio Citation2019; Khan Citation2020). Finally, immigration status on its own makes for a more insecure labour market experience (excepting highly skilled elite migrants) (Alba and Foner Citation2015; Zwysen and Demireva Citation2020), as immigrants tend to be the most vulnerable to labour market volatility and experience the most acute consequences of any economic downturn.

Hypothesis 3: Ethnic minorities in positions of economic marginality and those who were immigrants were more likely to vote Leave.

Ethnocentrism and sovereignty

As already indicated, one of the reasons why age and education were strongly predictive of the EU referendum vote in the general population due to their strong associations with ethnocentrism. This may seem an unpromising avenue to explain why some ethnic minorities supported Brexit, at least if we assume minorities are unlikely to hold white ethnocentric views. But as Storm et al. show, minorities do hold ethnocentric views (Storm, Sobolewska, and Ford Citation2017). The level of their ethnocentrism is often overlooked, because of their historically low levels of support for the radical right. For white Europeans, populist radical right parties mobilise ethnocentrism, by arguing that immigration and multiculturalism are responsible for their social and economic malaise, and that only the populist radical right understands and supports their concerns. For members of racialised ethnic minority groups who are the scapegoats of this narrative (Benson and Lewis Citation2019; Patel and Connelly Citation2019), voting for the radical right is clearly unattractive (Martin Citation2023), which is part of the reason why accounts of the left behind that arose from explaining support for the radical right have thus far excluded minorities. But voting for the anti-status quo option of Leave may have held more appeal, particularly when the anti-immigrant argument turned specifically towards migrants from Central and Eastern Europe, fitting with perceptions of unjust treatment of ethnic minorities compared to EU immigrants (Begum Citation2023). Researchers in other European contexts note that immigrant voters do not always perceive their interests as identical to each other (Goerres, Mayer, and Spies Citation2020; Meeusen, Abts, and Meuleman Citation2019). Linking immigration concerns and Euroscepticism was at the heart of the Leave campaign and is central to most academic analyses of the referendum (Evans and Mellon Citation2019; Goodwin and Milazzo Citation2017; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). Voters who were anxious about cultural change or outright hostile to immigrants felt membership of the EU limited the UK government’s ability to control immigration and voted accordingly.

The ever-increasing restrictions for non-EU immigration (such as caps on certain visa categories and limitations on family reunion), and the ease of arrival for European immigrants (through EU freedom of movement) by contrast was highlighted by the Leave campaign to mobilising such resentments among ethnic minorities. The hostile environment policy, now associated with the Windrush Scandal, underlined this disparity in treatment. Whilst Remain campaigners talked about potential disruption to the lives of EU immigrants to the UK, ethnic minorities with British citizenship were being detained and deported with little outcry before the Windrush scandal gained public attention in 2018. Leave campaigners openly tried to activate this source of ethnocentric threat, citing concern for ethnic minority Britons in their opposition to EU immigration. Ace Nnorom (ethnic minority UKIP candidate for Vauxhall) distinguished his own experience from that of Europeans: “When I came, before you gained your rights you had to struggle and you had to integrate and learn the values of the nation. Before it was open door immigration, the quality and value of Britishness was different” (Booth Citation2014). Similarly, Winston MacKenzie (ethnic minority UKIP candidate for Croydon North) explained that; “If it meant that black people were going to get a better deal in this country and the opportunities they deserve, yes I would offer some Polish people incentives to go back” (Surtees Citation2015). A leaflet from the pro-Brexit Muslims for Britain group asked: “Why is it harder for a qualified doctor or software engineer from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh or the Middle East to come to Britain than it is for an unskilled worker from Poland or Romania?” (Pickard Citation2016). Among the multiple campaign groups supporting Vote Leave were minority-specific groups such as Muslims for Britain or Africans for BritainFootnote2 who made similar arguments. The Bangladeshi Caterers Association supported Brexit, as part of the Save Our Curry Houses campaign,Footnote3 with the view that leaving the EU would permit the government to relax the minimum salary threshold for curry chefs, which they believed was causing a labour shortage in this industry.

Hypothesis 4: Ethnic minorities who held anti-immigrant views were more likely to support Leave.

Hypothesis 5. Support for British sovereignty will predict Leave support among minorities.

Data and methods

There is no single survey of ethnic minorities that would allow us to test our five hypotheses straightforwardly. Instead, we draw on two different datasets. Firstly, Understanding Society, a high-quality, large, representative household panel survey with booster samples of ethnic minorities and immigrants living in the UK.Footnote4 The advantage of this data is its sizeFootnote5 and random probability sample, making it the most representative available (University of Essex et al. Citation2019). However, it is not rich in explanatory political attitudes, so we also use waves 7 (April–May 2016) and 8 (May–June 2016) of the British Election Study Internet Panel (BESIP), a non-probability panel study of eligible voters administered online (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2021). Although the BESIP also has a sizeable sample of ethnic minority respondents,Footnote6 it is not designed to be representative of ethnic minority voters, so we derive our own weights to reduce some of the known biases in the sample (Martin Citation2019).

The two surveys also differ in how they asked respondents about the EU referendum. Understanding Society asked respondents the question on the referendum ballot paper, whilst the waves of BESIP that we use ask about respondent’s vote intention in the referendum. In neither case is turnout measured. We drop the (very few) respondents who did not choose either Leave or Remain. We use data from wave 8 of Understanding Society, which was in the field from January 2016 to June 2018. This is a much longer timescale than the waves of BESIP that we use – waves 7 and 8 which ran from April to June 2016, immediately before the referendum. The BESIP is an online-only study, so all respondents answered questions on their computer or internet-enabled mobile device, whilst Understanding Society is a mixed-mode survey using face-to-face interviews with a laptop-based self-completion component, or an option to complete the questionnaire online.

There are good reasons to use both surveys, as they are the best available large-scale data on ethnic minority views on Brexit collected at the time of the referendum. However, there are significant limitations to both studies. In terms of generalisability, self-selected online panels struggle to be representative of the whole population, and particularly ethnic minorities (Martin Citation2019). We deal with this by calculating ethnic minority-specific weights (details given in the Supplementary Information), but we remain cautious about generalising from the precise proportions of ethnic minorities holding particular viewpoints in this sample to the population as a whole. The bias is likely to be in the direction of over-estimating conservative viewpoints. We are more confident however that the relationship between Brexit vote and other variables is unlikely to be systematically affected to the same extent, and so we report regression models of Leave voting using BESIP data. The weakest interpretation of these models is as a test of the internal validity of our theory. Although it has a better claim to representativeness due to the random probability sample, Understanding Society also suffers from panel attrition over time. And a further limitation is that we are comparing respondents in two different surveys, when we know that they correspond to different populations. Our justification here is that the intended coverage of both surveys is the UK adult population, but both surveys will provide slightly different pictures of this same population, and the part of this population that belong to an ethnic minority group.

We test hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 using the same logit regression model of support for Brexit in Understanding Society. To test hypothesis 1, we consider the effect of age on support for Brexit. To test hypothesis 2, we compare respondents with a degree or degree-equivalent qualification to those with A levels or equivalents, to those with no or school-leaving qualifications only, and to those with other qualifications or missing data.Footnote7 To test hypothesis 3, we operationalise economic marginalisation using household poverty (Goodwin and Heath Citation2017; Hobolt Citation2016), occupational class (Evans and Tilley Citation2017; Ford and Goodwin Citation2014), housing tenure (Ansell and Adler Citation2019), and whether a household can afford adequate heating (a common measure of material deprivation). We also hypothesise that being born abroad might be an indicator of being more vulnerable to labour market competition from EU migrants, and so we also model the impact of immigration status directly. Although this binary approach risks overlooking some important gradations in immigration status – for instance those who arrived as children and completed some of their education in the UK will have a different experience of migration than those who moved to the UK as adults – we believe that this is the simplest and most comparable measure across groups and leave it to future work to consider other categorisations.

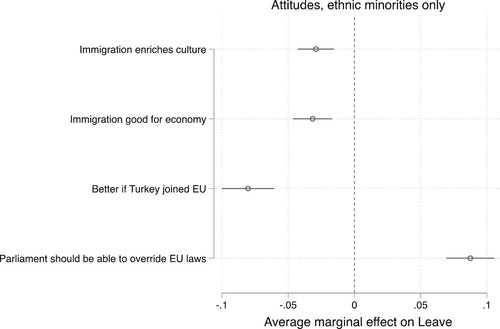

We proceed to test hypotheses 4 and 5 that attitudes associated with white left behind Leave voters operated among minorities choosing Leave. Understanding Society lacks the relevant attitudinal predictors, so we test these hypotheses with BESIP. First, we include two standard items on attitudes towards immigration, where respondents are asked to assess whether immigration is good or bad for Britain’s economy, and if they think that immigration undermines or enriches Britain’s cultural life. We include a Brexit-specific item which asks whether the EU would be better or worse off if it allowed Turkey to join as a member state. We include this because the prospect of Turkey, a Muslim-majority country, joining the EU was framed during the campaign as threatening an image of Europe as solely white and Christian. We also consider the issue of sovereignty (Hobolt Citation2016), and include an item which asks whether the British parliament should be able to override all EU laws. Don’t know responses or refusals are coded as missing values and dropped from the analysis, unless indicated.

Our model using BESIP contains a small number of standard controls: an index of social liberal-authoritarian values (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2019); gender (Green and Shorrocks Citation2023); age, and education (Hobolt Citation2016) – all elements previously identified as predictors of Leave voting. We also include an additional model using Understanding Society data that controls for partisanship. This variable has little predictive power for general models of Brexit, but is a crucial one given ethnic minorities’ distinct party alignment. In theory, Labour partisanship could explain much of the variation in Leave/Remain among ethnic minorities. The vast majority of minority voters support the Labour party and have done for decades (Anwar Citation1986; Heath et al. Citation2013; Martin Citation2019; Saggar Citation2000). If Euroscepticism were solely associated with the Conservatives and UKIP, then partisanship would make Labour-leaning minorities unlikely to support it. Concentrated in urban centres, ethnic minorities were more likely to be represented by pro-EU Labour MPs, and the pro-EU campaign organised a Labour-led sub-campaign aimed specifically at ethnic minority voters.

However, the question of EU membership was a cross-party discussion in 2016, with Vote Leave setting up minority-focussed “Outreach Groups” (Africans for Britain, Muslims for Britain, Bangladesh for Britain), and giving prominence to minority politicians like Priti Patel (a Vote Leave Campaign Committee member). Remain was also associated with the Conservatives through the support of the Conservative government. Free from the negative image of the Conservatives, and with different campaign organisations with tailored messaging, we expect that Leave were able to mobilise minority voters with both Labour and Conservative partisanship.

Results and discussion

As we use two different data sources, one representing a more ethnicity-centred sample, but poor in predictive political variables, and one constituting a richer source of political attitudes but potentially less representative of UK’s minorities, we analyse them separately. Understanding Society offers a better opportunity to test hypotheses 1–3 giving us a better idea of the distribution of relevant socio-demographics in our ethnic minority sample. However, it is impossible to test hypotheses 4 and 5 using this data, and so we use BESIP to see if political attitudes associated with Leave voting among white British voters were also predictive of Leave among minorities.

Left behind demographic predictors of leave: understanding society

Firstly, we confirm that support for Brexit was non-negligible among the main minority groups covered by this study. presents the proportion of different ethnic groups supporting Leave versus Remain in Understanding Society. All ethnic minority groups supported Leave less than the white British by some margin; the percentage point difference between white British and that of the largest 5 ethnic minority groups combined is 19 points. 33 per cent of Indians reported preferring Brexit compared to 25 per cent of Black Africans, 25 per cent of British Bangladeshis, 26 per cent of British Pakistanis, and 29 per cent of people with mixed ethnicity. The group with the second highest level of support are Black Caribbeans of whom 32 per cent supported Leave. We focus on ethnicity rather than immigration status as our key explanatory variable, and do not explore the reasons behind differences between ethnic minority groups further here, because the mechanisms that motivate our hypotheses apply to each of these racialised minority groups.

Table 1. Share of each ethnic group supporting Leave in Understanding Society wave 8 (2016–2017).

presents the results of a logit regression model testing hypotheses 1–3; that ethnic minority Leavers differ from ethnic minority Remainers on crucial demographic indicators characteristic of the left behind: age (H1), education (H2) and those in positions of economic vulnerability, including being born abroad (H3). Results are presented as average marginal effects.

Table 2. Logit regression models of Leave vs. Remain among ethnic minorities. Coefficients are presented as average marginal effects.

Looking at age, we see that it is strong and highly significant; net of other factors, 19 per cent of ethnic minority twenty-year-olds supported Brexit, compared to 37 per cent of those aged seventy, i.e. almost double in the oldest age group. The relative youth of ethnic minorities may be one contributor to their higher support for Remain: fewer young people have memories of life before the European Union, which for some Leave voters made the possibility of life outside seem more plausible. This strongly supports hypothesis 1, that older age is a strong predictor of higher support for Brexit among ethnic minorities, as with the white left behind voter.

However, as expected, when it comes to hypothesis 2 (education), there is no significant difference at all between ethnic minorities with different levels of educational attainment. This is understandable for the reasons outlined above. For migrant ethnic minorities, educational qualifications are often not equally rewarded in the labour market, so education is less important for their economic position, and educational qualifications even of British-born minorities can be downgraded due to racial discrimination. However, we believe the most important reason for this lack of an educational gradient is that in general, more highly-educated voters are less likely to be mobilised by ethnocentric political projects because education decreases ethnocentrism and increases positive attitudes to immigration, creating “conviction liberals” (Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). But, for ethnic minorities no additional socialisation into anti-prejudice norms is necessary, as self-interest means that most are already “necessity liberals”. Instead, we think that factors other than education may predict ethnocentrism among minorities. We leave this to future research, as the data available here are insufficient for this purpose.

Turning to hypothesis 3 (deprivation), we see that some aspects of economic marginalisation are associated with greater support for Leave among minorities, in common with the more general left behind argument. Firstly, we look at place of birth, with the expectation that minorities born overseas will be more likely to support Brexit than those born in the UK. This is indeed what we see in the results; controlling for other factors, immigrants were 7 percentage points more likely to support Brexit than UK-born minorities.Footnote8 Given that overall support for Brexit among this group was only 29 per cent, this is an important difference. To put it differently, our data suggests that 68 per cent of Leave’s support among minorities came from migrants, compared to 52 per cent of Remain’s support. As well as economic marginalisation, we also expect that Vote Leave arguments that ethnic minorities and migrants from other parts of the world were losing out from European integration will have resonated more with migrants, rather than UK-born minorities, but we are unable to test this further with the data available.

Turning to other aspects of economic marginalisation, we see that ethnic minorities in working class jobs (routine occupations) were more likely to support Brexit (4 points) than those in middle class ones (professional occupations). Material deprivation in housing seems to matter too; all else being equal, those living in households unable to heat their home adequately were 5 points more likely to support Brexit, and both social (4 points) and private (4 points) renters were more likely to support Brexit compared to minorities who own their home. This suggests material deprivation is worth considering as an explanation for ethnic minority Leave voting, analogous to the left behind argument. However, not all forms of economic marginalisation are important; there are no significant differences between households living above or below the poverty line, nor between individuals in and out of the labour market.Footnote9

presents the results of the same model controlling for partisanship, allowing us to see that ethnic minorities with a Conservative partisanship before the referendum were 14 points more likely to support Brexit than Labour partisans.Footnote10 This is noteworthy, because the social and economic factors which predict Leave support among minorities are normally associated with stronger Labour partisanship. However, this ignores the 50 per cent of minorities with no partisanship who typically vote Labour,Footnote11 but were 5 points more likely to support Leave than were Labour partisans. Just as with white left behind voters, Leave was able to mobilise ethnic minorities who would not usually be associated with (what came to be) a right-of-centre political project, and those from different parties.

Left behind political attitudes – BESIP study

We now turn to British Election Study Internet Panel data which contains more attitudinal variables than Understanding Society to test hypotheses 4 and 5 that the attitudes characteristic of left behind voters predicted ethnic minority voters’ Brexit support in ways comparable to the general population. Before we move onto the effects of the two main hypothesised attitudinal predictors – anti-immigrant sentiment (H4) and support for sovereignty (H5) – we leverage the additional data that BESIP offers. BESIP respondents were asked to name the most important issues that were considered when making up their minds in the 2016 referendum. Looking at the differences between Leavers and Remainers of both white British and ethnic minority origin on what they named as most salient to them is informative. These results are reweighted for ethnic minority respondents to correct for the over-representation of Conservatives in the data (see Supplementary Materials). Nevertheless, we consider that this sample is likely to be more right-wing and more similar to white British voters due to unobservable differences, so these proportions should be taken as indicative and not definitive.

presents the most important issue for deciding how to vote on Brexit, as described by BESIP respondents pre-referendum. In comparing ethnic minority and white British respondents, two things are apparent. Firstly, although the percentage points for various reasons given by minorities and majority voters differ, the difference in attitudes between Leavers and Remainers on each issue is remarkably similar. This suggests that minority and majority voters experienced extremely similar attitude gaps.

Table 3. Reasons for supporting Leave or Remain.

Secondly, a substantial minority – one third – of ethnic minority respondents reported immigration as the most important issue. This is consistent with the view that some ethnic minorities voted Leave due to a dislike of immigration, just like their white peers. We can see this in examining the full-text responses in more detail. One Leave voter of Indian ethnicity highlighted “Identity … controlled immigration” as their reason for supporting Leave, whilst another mentioned the “mass number of EU migrants in the UK”. One Pakistani ethnicity voter directly compared disparities in immigration rules; “immigration laws seperate for EU and seperate for commonwealth” (sic.), and a Black African voter who supported Leave pointed to the perceived strain on public services; “Failing public utilities through uncontrolled immigration”. Another negative perception of migrants is criminality, mentioned by one voter thus: “criminals and the eastern europeans” (sic.). Nevertheless, some respondents mentioned immigration as a reason to support Remain rather than Leave, such as the Indian Remain voter who mentioned “movement within the EU”, or a Pakistani voter who reported “workers right and freedom to travel and live in other countrys” (sic.).

Testing hypotheses 4 and 5, presents the results of a logit regression model of Brexit vote using attitudinal predictors among ethnic minorities in BESIP. Ethnicity, age, educational attainment, and liberal-authoritarian social values are included as control variables, but not shown. Most of our hypothesised attitudes associated with left behind voter narratives are significant predictors of Leave/Remain among minority voters and have the expected direction. Minorities who are more sceptical about the benefits of immigration are more supportive of Leave. Although ethnic minority voters are more positive on average towards immigration than white voters, these results suggest that views of migration are politically consequential and have a similar impact among minorities as they have among the white British. There may be more nuanced views of different kinds of immigration. For example, ethnic minority Brexiteers who opposed rising Eastern European immigration may view EU freedom of movement as a less legitimate migration pathway than post-colonial migration, believing that Commonwealth immigrants – with earlier generations seeing themselves as part of the wider British Empire – should have greater rights to enter Britain than other Europeans. However, whatever the rationale, these are still ethnocentric attitudes, and they clearly work in the same way among minorities when they are politically activated.

Figure 1. Effects of attitudinal predictors on EU referendum vote choice among ethnic minorities. Model controls for ethnicity, age, education, and liberal-authoritarian values. Data: British Election Study Internet Panel waves 7 and 8 (April–June 2016).

Another ethnocentric attitudinal predictor available was the question of Turkey’s potential EU membership, often referred to in the campaign as a Muslim-majority nation and depicted as a route for Islamist terrorists to enter the UK. This openly racialised issue unsurprisingly did not resonate to the same extent, as more ethnic minorities believed that it would be positive if Turkey joined the EU than white British voters;Footnote12 but nevertheless, it predicts vote choice in the same way: those minorities who thought it would be bad if Turkey joined the EU were more likely to have voted for Brexit. This offers strong support for hypothesis 4, that ethnocentric attitudes usually associated with the left behind mobilised ethnic minority Leavers too. There are fewer minority ethnocentric voters, confirming the instinct that many would be “necessity liberals”, but those who were ethnocentric certainly were more likely to choose Brexit, just like their white ethnocentric counterparts.

Finally, shows that beliefs about sovereignty – another white left behind concern – also mattered in the way we hypothesised (H5). Those that thought that the British Parliament ought to be able to overrule all EU laws were (perhaps unsurprisingly) more likely to vote for Brexit. Ethnic minorities were among the voters who disliked the EU’s interference in British sovereignty (as they saw it) and were sceptical about the benefits of freedom of movement.

Conclusions

In this paper we argued that accounts of left behind voters who supported Brexit have been wrongly limited to white voters. Partly, this has been caused by data limitations, but partly by the unspoken assumption that being left behind is a uniquely white experience. Our findings corroborate and extend existing evidence that support for Brexit was much lower among ethnic minorities than among white Britons. Nevertheless, more minorities report supporting Brexit than have ever voted Conservative, and we argue that the mechanisms through which they chose this position were analogous to those of white Brexit supporters. Most left behind characteristics such as being older and economically marginalised worked as predictors of the referendum vote in the same way regardless of ethnicity. The only significant way in which ethnic minority Leave voters did not compare to white Leavers was the lack of an educational gradient in Brexit support.

There is a clear parallel to material deprivation explanations for radical right voting that are used in left behind narratives. White voters who believe that immigrants and ethnic minorities are responsible for their decreased economic and social status support radical right parties which echo this message. For minorities, the different treatment of EU migrants, alongside Leave campaign promises of better treatment for Commonwealth countries, offered a similar group-based reason to support Brexit. Vote Leave campaigns like Save Our Curry Houses, with the message that EU freedom of movement was responsible for labour shortages in the curry industry, clearly resonated. Moreover, those experiencing material deprivation were less supportive of the status quo and more sympathetic towards Brexit. More ethnic minorities did support Remain rather than Leave and concerns over racism and xenophobia were cited as a major reason behind this (Begum Citation2023), even if we are unable to test this explanation quantitatively.

Minorities who supported Leave not only had similar socio-economic backgrounds, but also similar political attitudes to those identified by research focussing on majority white voters: they shared concerns over the threat to UK sovereignty posed by the EU, combined with concerns over immigration. Although less prevalent among minorities, negative feelings about immigration are important for some British ethnic minority voters. However, for minorities with personal or family experiences of migration, it is opposition to immigrants from EU countries, who are seen as taking employment, resources or public acceptance from earlier established minority groups, that correlates with Brexit support. This highlights the ambiguous conflation of immigration attitudes and specific racial prejudices in some discussions of immigration attitudes.

Our results suggest that more careful attention to ideological diversity among ethnic minorities matters. In 2010, ethnic minorities were (on average) slightly more right-wing in both economic and social terms than the average white British voter (Heath et al. Citation2013). However, some observers note only that ethnic minority support for Labour is high, and consequently make mistaken assumptions about the attitudes and values of minority voters. What differentiates minority voters and explains strong support for Labour is not economic or social values, but prioritising equal opportunities and anti-discrimination policy (Heath et al. Citation2013; Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020). With targeted messages to ethnic minority groups and distance from the more exclusionary Leave.EU campaign, Vote Leave succeeded amongst some voters in escaping the association with racism that makes the Conservative Party unattractive to many minority voters.

There are many potential explanations for ethnic minority voters’ decisions in the referendum. Lacking a full election study of ethnic minorities, with specific questions on racialised issues that explore whether, for instance, voters perceived their interests as competing with EU migrants, or whether negative campaigning on Turkey joining the EU was viewed as more broadly anti-Muslim, researchers rely on other sources of information like focus groups and interviews (Begum Citation2023). Another question which we are unable to pursue here is whether our left behind framing applies unequally to different ethnic minority groups. However, we suspect that the “necessity liberal” (Sobolewska and Ford Citation2020) logic applies to all racialised minority groups in the UK electorate. Although campaign arguments were made to particular groups (e.g. Africans for Brexit, Muslims for Britain), they were made on similar grounds that (for instance) relationships with Commonwealth countries would be strengthened by Brexit by removing the (presumably unfair) preference for EU immigration.

Our findings show the importance of testing explanations of electoral behaviour developed on samples of predominantly white voters before assuming that they apply to white voters only. We expand the concept of the left behind voter to include ethnic minority left behind voters. However, given that the left behind concept assumes that whiteness is of importance we also push future research to interrogate this further. Specifically, given that many characteristics of the left behind and their impact on politics are not exclusive to white voters, future work should ask, and measure directly, the mechanism through which whiteness increases or moderates the effects of being left behind. We are convinced by the arguments from critical scholars that identify the methodological whiteness of mainstream electoral studies literature on Brexit, and the unjustified exclusion of minorities from the concept of economically-marginalised and left behind voters (Bhambra Citation2017; Isakjee and Lorne Citation2019; Khan, and Shaheen Citation2017). It is insufficient to rely on proxies that are not exclusive to white voters, or to simply include an ethnic minority dummy variable to show that whiteness plays a distinctive role. Our work highlights that differences in the distribution of left behind characteristics obscure the fact that the concept works equally well in predicting ethnic minority political behaviour that mobilises these characteristics.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (105.1 KB)Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at University of Liverpool 2020 Elections, Public Opinion and Parties conference at the University of Nottingham, 2017; Understanding Society Scientific Conference at the University of Essex, 2019; University of Liverpool seminar, 2020; and Royal Holloway University of London seminar, 2021. We are grateful for formative comments received at these presentations. A previous version of this paper was available on the Social Science Research Network: Martin, Nicole and Sobolewska, Maria and Begum, Neema, Left Out of the Left Behind? Ethnic Minority Support for Brexit (January 22, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract = 3320418

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Sobolewska and Ford (Citation2020) contrast ethnic minorities who are liberal on impacts of immigration and anti-discrimination law by personal necessity with white university graduates who are liberal through conviction.

2 The Africans for Britain campaign formally ceased campaigning for Leave during the campaign, alarmed by Boris Johnson’s comments about Barack Obama’s “part Kenyan” background, and expressing fears that the Leave campaign was scapegoating migrants.

3 A Vote Leave campaign event retitled this as “Save the British Curry” – clearly including curry as part of the Britain which stood to gain from leaving the EU.

4 Understanding Society has two booster samples of ethnic minorities; one which covers 82-93% of the ethnic minority population in Great Britain and started in 2009–2010, and the second which started in 2015–2016 and covers immigrants to the UK. Ethnic minorities living in areas not targeted by boost samples are covered as part of the large general population sample.

5 There are 5,055 respondents with a non-missing value on the dependent variable and an ethnic group that is one of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean, Black African, or mixed background.

6 There are 1,714 respondents with a non-missing value on the dependent variable and an ethnic group that is one of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean, Black African, or mixed background.

7 This category is more important when studying minorities because it is more prevalent among those whose qualifications were obtained outside the UK. 21% of Understanding Society respondents born overseas fall into this category, compared to 9% of those born in the UK.

8 The difference without controlling for other factors is 14 percentage points, as 35% of ethnic minorities born outside the UK supported Leave compared to 21% of those born in the UK.

9 In contrast, almost all these factors are significant predictors in a comparison model of white Britons, with those in more marginal positions more likely to support Brexit in each case.

10 The comparable difference for white Britons is 25 percentage points.

11 In our data, 61% of minorities with no party identity had a Labour vote intention in 2015–2016, compared to 23% for the Conservatives.

12 In our data, 42% of ethnic minorities thought that the EU would be worse if this happened, compared to 82% of the white British.

References

- Alabrese, E., S. O. Becker, T. Fetzer, and D. Novy. 2019. “Who Voted for Brexit? Individual and Regional Data Combined.” European Journal of Political Economy 56: 132–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.08.002.

- Alba, R., and N. Foner. 2015. Strangers No More: Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Altorjai, S. 2013. Over-Qualification of Immigrants in the UK. Working Paper Series. Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex. Accessed 12 October 2021. https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/research/publications/working-papers/iser/2013-11.pdf.

- Ansell, B., and D. Adler. 2019. “Brexit and the Politics of Housing in Britain.” The Political Quarterly 90 (S2): 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12621.

- Anwar, M. 1986. Race and Politics: Ethnic Minorities and the British Political System. London: Tavistock.

- Begum, N. 2023. “The European Family? Wouldn’t That be the White People?” Brexit and British Ethnic Minority Attitudes Towards Europe.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 46 (15): 3293–3315.

- Benson, M., and C. Lewis. 2019. “Brexit, British People of Colour in the EU-27 and Everyday Racism in Britain and Europe.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (13): 2211–2228. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1599134.

- Berthoud, R. 2000. “Ethnic Employment Penalties in Britain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26 (3): 389–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/713680490.

- Bhambra, G. 2017. “Brexit, Trump, and ‘Methodological Whiteness’: On the Misrecognition of Race and Class.” The British Journal of Sociology 68 (S1): S214–S232. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12317.

- Booth, R. 2014. “UKIP’s Black Candidates Join Tussle for Ethnic Minority Vote in Croydon.” The Guardian, May 13. Accessed 12 October 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/may/13/ukip-black-candidates-ethnic-minority-vote-croydon.

- Brynin, M., and S. Longhi. 2015. The Effect of Occupation on Poverty among Ethnic Minority Groups. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Byrne, B., C. Alexander, O. Khan, J. Nazroo, and W. Shankley. 2020. Ethnicity, Race and Inequality in the UK: State of the Nation. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Cutts, D., M. Goodwin, O. Heath, C. Milazzo, 2019. “Resurgent Remain and a Rebooted Revolt on the Right: Exploring the 2019 European Parliament Elections in the United Kingdom.” The Political Quarterly 90 (3): 496–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12736.

- Evans, G., and J. Mellon. 2019. “Immigration, Euroscepticism and the Rise and Fall of UKIP.” Party Politics 25 (1): 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818816969.

- Evans, G., and A. Menon. 2017. Brexit and British Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2017. The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fieldhouse, E., J. Green, G. Evans, J. Mellon, C. Prosser, R. de Geus, J. Bailey, H. Schmitt, and C. van der Eijk. 2021. British Election Study, 2019: Internet Panel, Waves 1-20, 2014-2020. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 8810.

- Fieldhouse, E., J. Green, G. Evans, J. Mellon, C. Prosser, H. Schmitt, C. Van der Eijk, 2019. Electoral Shocks: The Volatile Voter in a Turbulent World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ford, R., and M. J. Goodwin. 2010. “Angry White Men: Individual and Contextual Predictors of Support for the British National Party.” Political Studies 58 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00829.x.

- Ford, R., and M. J. Goodwin. 2014. Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gidron, N., and P. A. Hall. 2017. “The Politics of Social Status: Economic and Cultural Roots of the Populist Right.” The British Journal of Sociology 68 (S1): S57–S84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12319.

- Goerres, A., S. J. Mayer, and D. C. Spies. 2020. “Immigrant Voters Against Their Will: A Focus Group Analysis of Identities, Political Issues and Party Allegiances among German Resettlers During the 2017 Bundestag Election Campaign.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (7): 1205–1222. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1503527.

- Goodwin, M. J., and O. Heath. 2016. “The 2016 Referendum, Brexit and the Left Behind: An Aggregate-Level Analysis of the Result.” The Political Quarterly 87 (3): 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12285.

- Goodwin, M. J., and O. Heath. 2017. The UK 2017 General Election Examined: Income, Poverty and Brexit. London.: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Goodwin, M. J., and C. Milazzo. 2015. UKIP: Inside the Campaign to Redraw the Map of British Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goodwin, M., and C. Milazzo. 2017. “Taking Back Control? Investigating the Role of Immigration in the 2016 Vote for Brexit.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (3): 450–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117710799.

- Green, J., and R. Shorrocks. 2023. “The Gender Backlash in the Vote for Brexit.” Political Behavior 45 (1): 347–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09704-y.

- Heath, A., et al. 2013. The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, A. F., and S. Y. Cheung. 2007. Unequal Chances: Ethnic Minorities in Western Labour Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, A. F., and V. Di Stasio. 2019. “Racial Discrimination in Britain, 1969–2017: A Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments on Racial Discrimination in the British Labour Market.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (5): 1774–1798. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12676.

- Hobolt, S. B. 2016. “The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1259–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785.

- Isakjee, A., and C. Lorne. 2019. “Bad News from Nowhere: Race, Class and the ‘Left Behind’.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37 (1): 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X18811923b.

- Jennings, W., and G. Stoker. 2016. “The Bifurcation of Politics: Two Englands.” The Political Quarterly 87 (3): 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12228.

- Khan, O. 2020. The Colour of Money: How Racial Inequalities Obstruct a Fair and Resilient Economy. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Khan, O., and D. Weekes-Bernard. 2015. This Is Still About Us Why Ethnic Minorities See Immigration Differently. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Khan, O., and F. Shaheen (2017) Minority Report: Race and Class in Post-Brexit Britain. London. Runnymede Trust.

- Kriesi, H., et al. 2006. “Globalization and the Transformation of the National Political Space: Six European Countries Compared.” European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x.

- Li, Y., and A. F. Heath. 2020. “Persisting Disadvantages: A Study of Labour Market Dynamics of Ethnic Unemployment and Earnings in the UK (2009-2015).” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (5): 857–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539241.

- Martin, N. S. 2019. “Ethnic Minority Voters in the UK 2015 General Election: A Breakthrough for the Conservative Party?” Electoral Studies 57: 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.12.004.

- Martin, N. S. 2023. “How Does the Strength of the far Right Affect Ethnic Minority Political Behaviour?” Parliamentary Affairs 76 (2): 320–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsab060.

- Martin, N. S., and O. Khan. 2019. Ethnic Minorities at the 2017 British General Election. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Martin, N. S., and M. Sobolewska. 2023. “The End of the Ethnic Bloc Vote? Ethnic Minority Leavers After the Brexit Referendum.” PS: Political Science & Politics 56 (4): 566–571.

- Maxwell, R. 2010. “Evaluating Migrant Integration: Political Attitudes Across Generations in Europe.” International Migration Review 44 (1): 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00797.x.

- McAndrew, S., P. Surridge, and N. Begum. 2017. Social Identity, Personality and Connectedness: Probing the Identity and Community Divides behind Brexit. SocArXiv. Accessed 12 October 2021. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/w95xa.

- Meeusen, C., K. Abts, and B. Meuleman. 2019. “Between Solidarity and Competitive Threat?” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 71: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.04.002.

- Mondon, A., and A. Winter. 2020. Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist far Right Became Mainstream. London: Verso Books.

- Nandi, A., and L. Platt. 2015. “Patterns of Minority and Majority Identification in a Multicultural Society.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (15): 2615–2634. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1077986.

- Patel, T., and L. Connelly. 2019. “‘Post-Race’ Racisms in the Narratives of ‘Brexit’ Voters.” The Sociological Review 67 (5): 968–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119831590.

- Pickard, J. 2016. “Vote Leave Woos British Asians with Migration Leaflets.” Financial Times, May 19. Accessed 12 October 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/94adcefa-1dd5-11e6-a7bc-ee846770ec15.

- Saggar, S. 2000. Race and Representation: Electoral Politics and Ethnic Pluralism in Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Shaw, K. 2022. “Reading Brexit Backwards: British Eurosceptic Fiction from the European Coal and Steel Community to Maastricht.” Open Library of Humanities 8 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.8840.

- Sobolewska, M., and R. Ford. 2020. Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Storm, I., M. Sobolewska, and R. Ford. 2017. “Is Ethnic Prejudice Declining in Britain? Change in Social Distance Attitudes among Ethnic Majority and Minority Britons.” The British Journal of Sociology 68 (3): 410–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12250.

- Surtees, J. 2015. “Meet The Black Brits Backing UKIP.” The Voice Online, May 6 2015. accessed 14th September 2023. https://archive.voice-online.co.uk/article/meet-black-brits-backing-ukip.

- University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, NatCen Social Research, Kantar Public. 2019. Understanding Society: Waves 1-9, 2009-2018 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009. [Data Collection]. 12th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6614.

- Virdee, S., and B. McGeever. 2018. “Racism, Crisis, Brexit.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (10): 1802–1819. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1361544.

- Zwysen, Wouter, and Neli Demireva. 2020. “Ethnic and Migrant Penalties in job Quality in the UK: The Role of Residential Concentration and Occupational Clustering.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (1): 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1498777.

- Zwysen, W., and S. Longhi. 2016. Labour Market Disadvantage of Ethnic Minority British Graduates: University Choice, Parental Background or Neighbourhood? Working Paper Series. Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex. Accessed 12 October 2021. https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/research/publications/working-papers/iser/2016-02.pdf.